Systematic Literature Review on Forms of Communitization that Feature Alternative Nutritional Practices

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

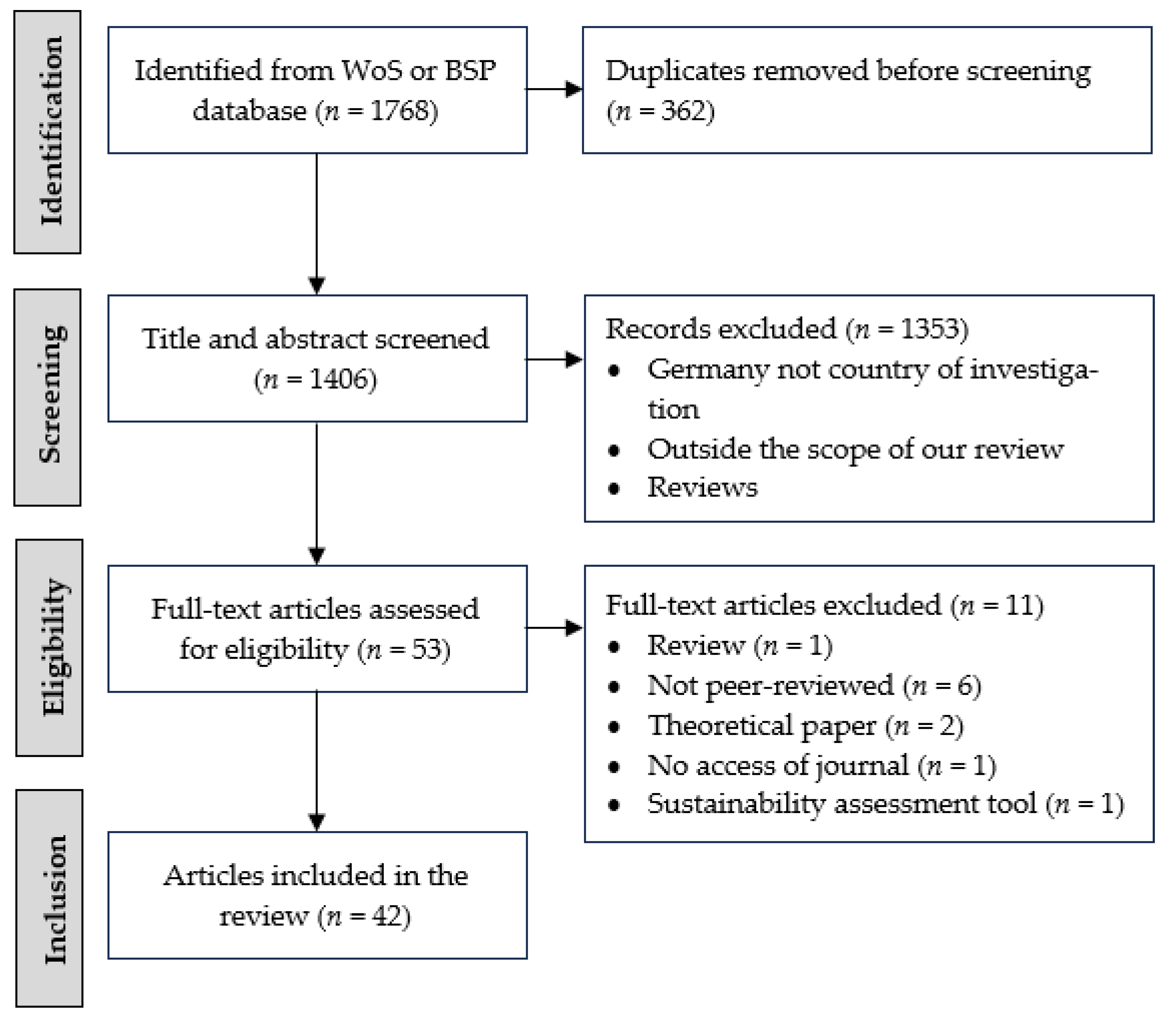

2.1. Literature Selection

2.2. Methodological Assessment and Analysis

2.3. Analytical Framework

3. Results

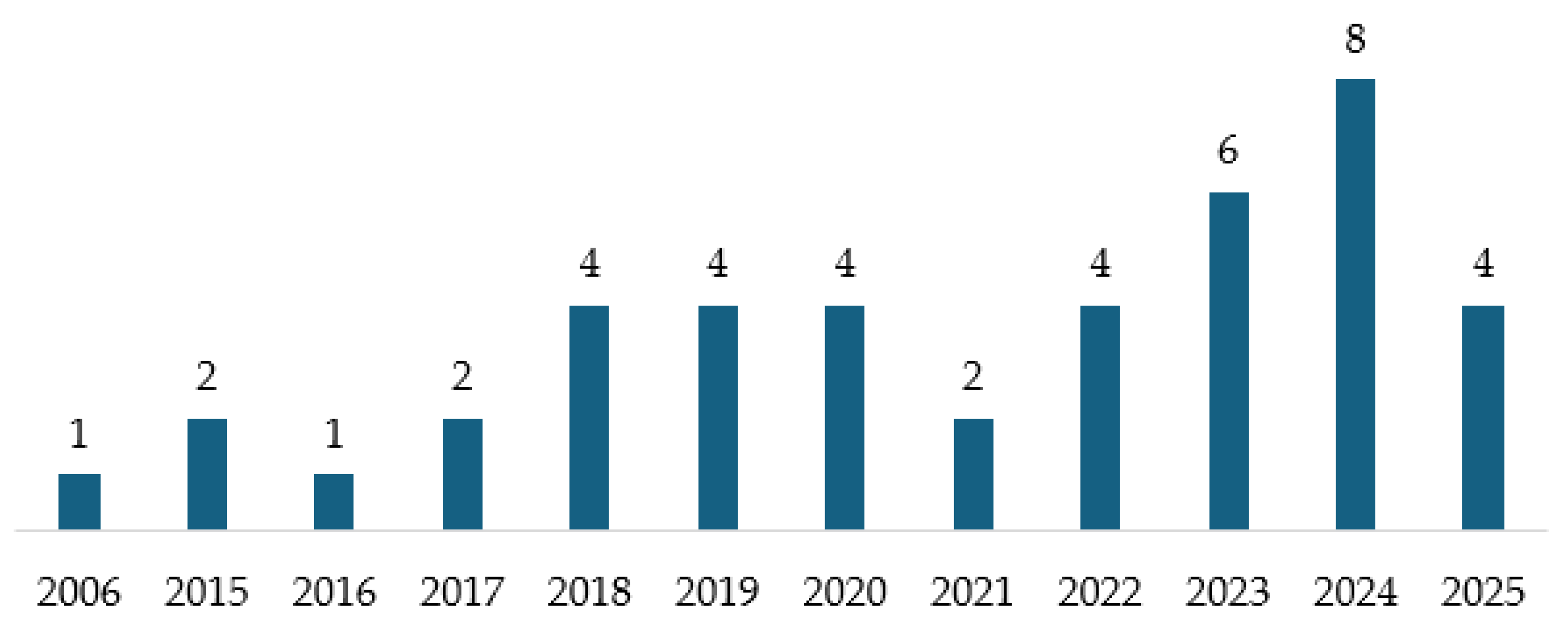

3.1. Bibliographic Analysis

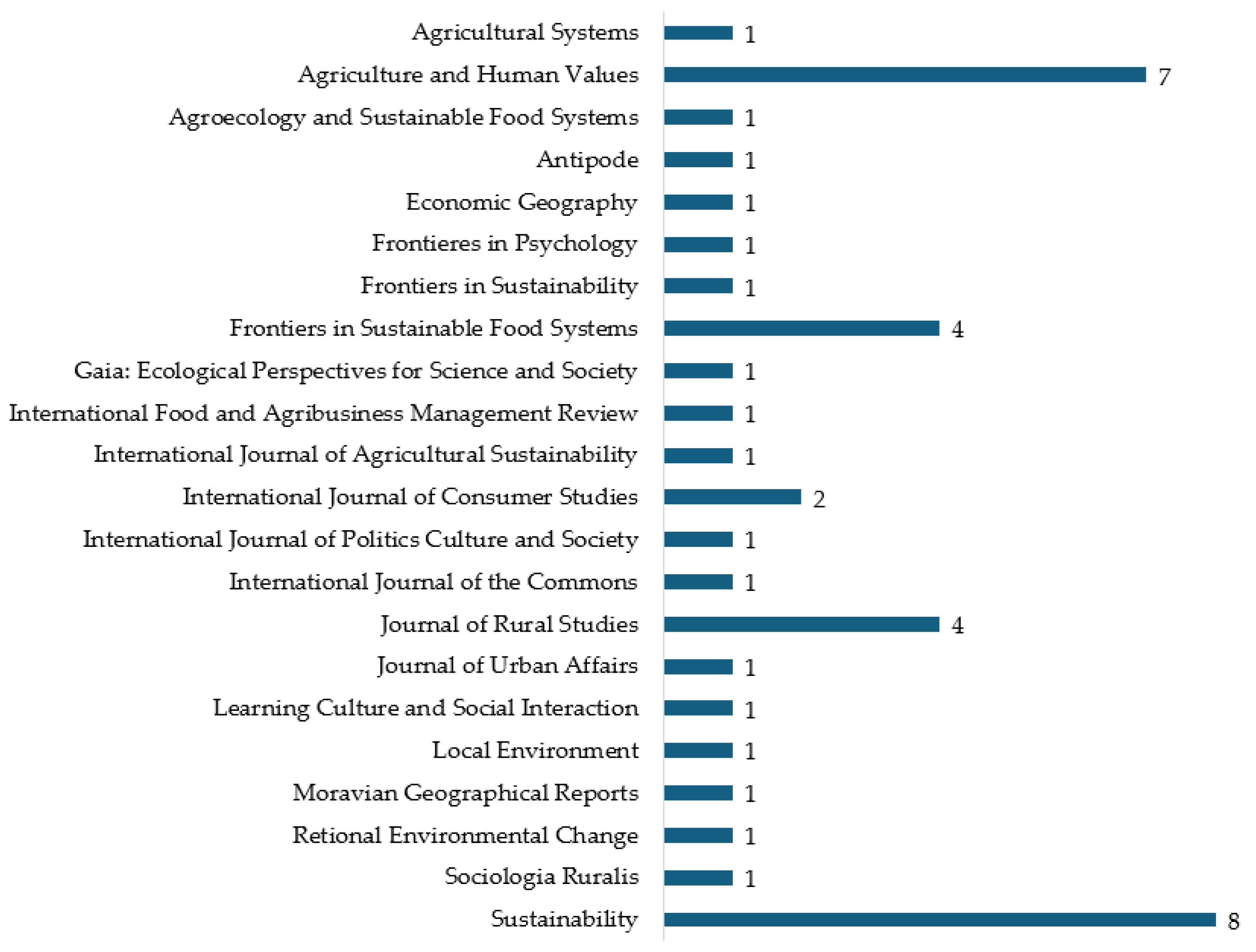

3.1.1. Journals and Number of Publications

3.1.2. Methodologies Applied

3.1.3. Objectives of the Papers

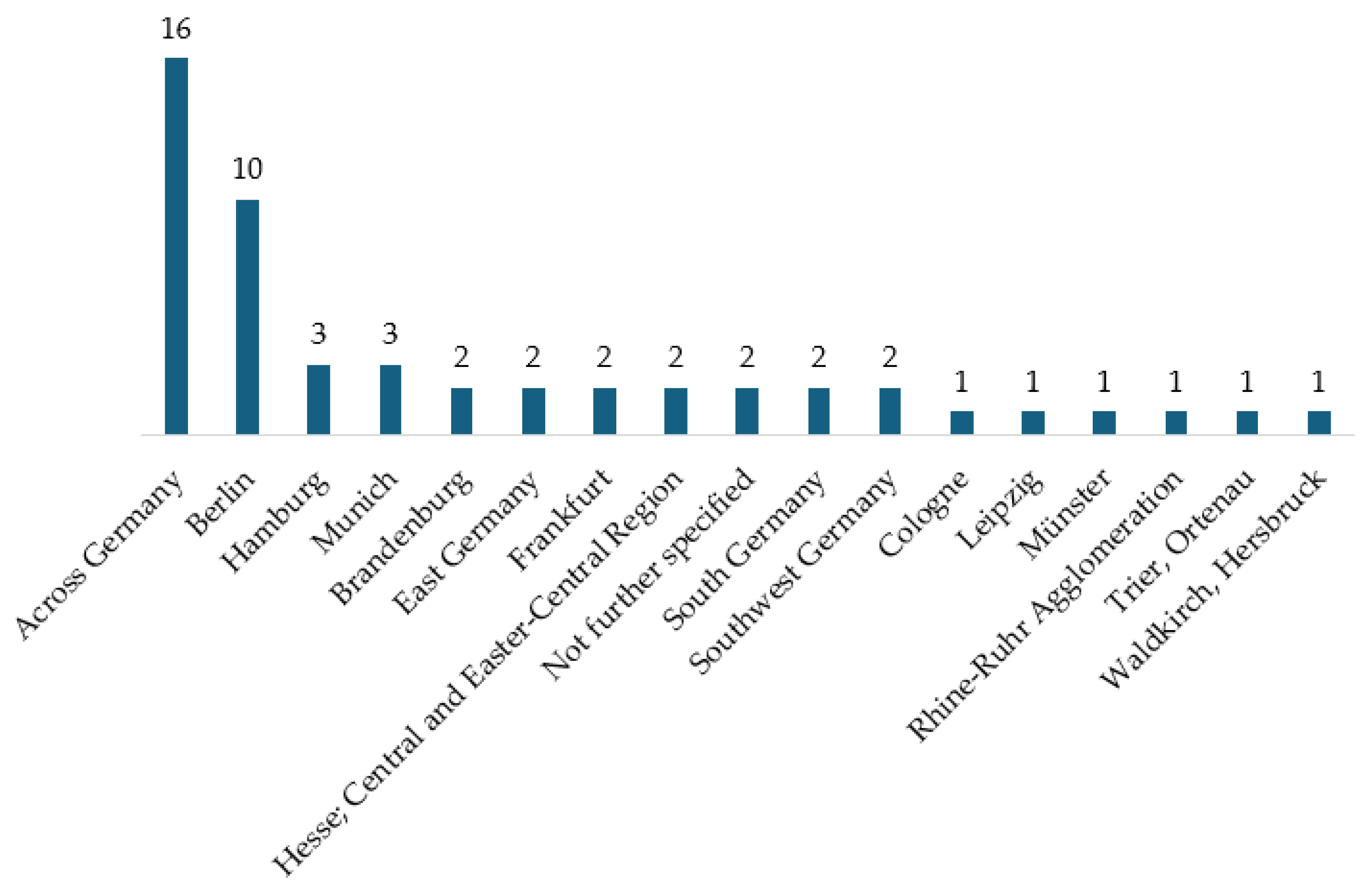

3.1.4. Forms of Communitization as well as Cities and Regions Examined

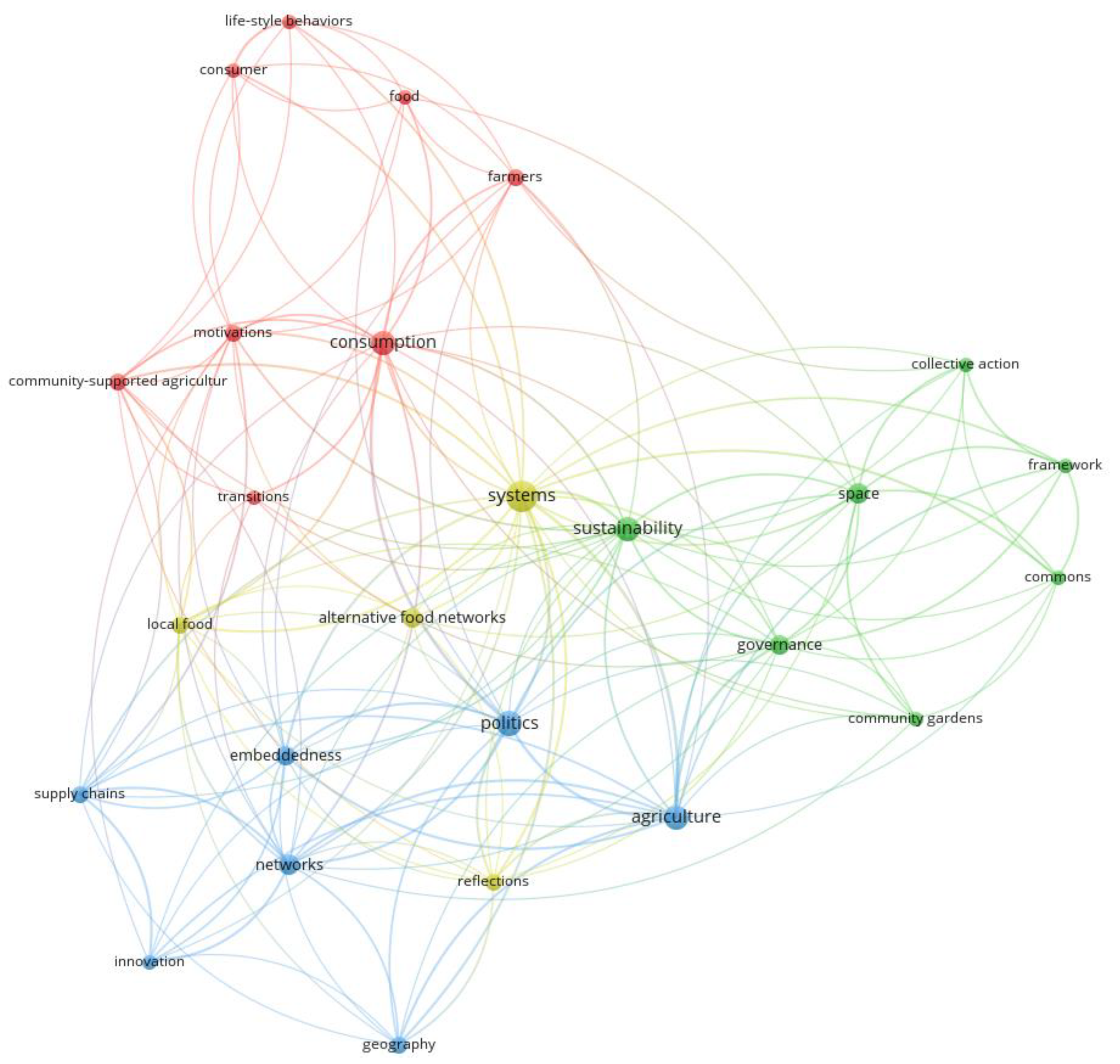

3.1.5. Keywords and Co-Occurrence Analysis

3.2. Content Analysis of Forms of Communities that Feature Alternative Nutritional Practices

3.2.1. Community, Urban and Self-Harvest Gardens or Public Space Food Projects

3.2.2. Food Cooperatives or Cooperative Initiatives

3.2.3. Food Sharing and Redistribution Initiatives (also over Digital Platforms)

3.2.4. Community-Supported Agriculture Networks and Community-Supported Agriculture

3.2.5. Ecovillage, Commune, Food Initiatives, and Other Partnerships

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFN | Alternative food network |

| AFNs | Alternative food networks |

| BSP | Business Source Premier |

| CSA | Community-supported agriculture |

| MAXQDA | Max Qualitative Data Analysis |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| VOS | Visualization of Similarities |

| WoS | Web of Science |

Appendix A

| Database | Search | Syntax |

|---|---|---|

| WoS | 1. | Refine results for (ALL = (community-supported agriculture)) AND ALL = (alternative *) and GERMANY (Countries/Regions) and Article or Review Article (Document Types) and English or German (Languages) and Article or Review Article or Early Access (Document Types) |

| WoS | 2. | Refine results for (ALL = (community-supported agriculture)) AND ALL = (Germany) and GERMANY (Countries/Regions) and English or German (Languages) and Article or Review Article or Proceeding Paper or Early Access (Document Types) |

| WoS | 3. | Refine results for (ALL = (alternative-food network)) AND ALL = (Germany) and GERMANY (Countries/Regions) and English or German (Languages) and Article or Review Article or Early Access (Document Types) |

| WoS | 4. | Refine results for (ALL = (alternative food network)) AND ALL = (Germany) and GERMANY (Countries/Regions) and English or German (Languages) and Article or Review Article or Early Access (Document Types) |

| WoS | 5. | Refine results for ((ALL = (alternative-food network)) AND ALL = (Germany)) AND ALL = (social innovation) and GERMANY (Countries/Regions) and English (Languages) and Article (Document Types) |

| WoS | 6. | Refine results for ((ALL = (alternative food network)) AND ALL = (Germany)) AND ALL = (social innovation) and GERMANY (Countries/Regions) and English (Languages) and Article or Review Article or Early Access (Document Types) |

| WoS | 7. | Refine results for (ALL = (social food movement)) AND ALL = (Germany) and GERMANY (Countries/Regions) and English or German (Languages) and Article or Review Article or Early Access or Proceeding Paper (Document Types) |

| WoS | 8. | Refine results for ((ALL = (food movement)) AND ALL = (Germany)) AND ALL = (community) and GERMANY (Countries/Regions) and English or German (Languages) and Article or Review Article or Early Access or Proceeding Paper (Document Types) |

| WoS | 9. | Refine results for (((ALL = (community supported agriculture)) AND ALL = (alternative food network *)) OR ALL = (cooperative *)) AND ALL = (alternative food network *) and English or German (Languages) and Article or Review Article or Early Access or Proceeding Paper (Document Types) |

| WoS | 10. | Refine results for (ALL = (ecovillage)) AND ALL = (Germany) and GERMANY (Countries/Regions) and English (Languages) and Article or Review Article (Document Types) |

| BSP | 1. | Search all fields (community supported agriculture AND alternative food network) with filter Academic Journal, English, German, Scientific (Peer-reviewed) Journal |

| BSP | 2. | Search all fields (community-supported agriculture AND Germany) with filter Academic Journal, English, German, Scientific (Peer-reviewed) Journal |

| BSP | 3. | Search all fields (alternative-food network AND Germany) with filter Academic Journal, English, German, Scientific (Peer-reviewed) Journal |

| BSP | 4. | Search all fields (alternative food network AND Germany) with filter Academic Journal, English, German, Scientific (Peer-reviewed) Journal |

| BSP | 5. | Search all fields (alternative-food network AND Germany AND social innovation) with filter Academic Journal, English, German, Scientific (Peer-reviewed) Journal |

| BSP | 6. | Search all fields (alternative food network AND Germany AND social innovation) with filter Academic Journal, English, German, Scientific (Peer-reviewed) Journal |

| BSP | 7. | Search all fields (social movement AND Germany) with filter Academic Journal, English, German, Scientific (Peer-reviewed) Journal |

| BSP | 8. | Search all fields (food movement AND Germany AND community) with filter Academic Journal, English, German, Scientific (Peer-reviewed) Journal |

| BSP | 9. | Search all fields (community supported agriculture AND alternative food network * OR cooperative * AND alternative food network *) with filter Academic Journal, English, German, Scientific (Peer-reviewed) Journal |

| BSP | 10. | Search all fields (ecovillage AND Germany) with filter Academic Journal, English, German, Scientific (Peer-reviewed) Journal |

Appendix B

| Behrendt, G.; Peter, S.; Sterly, S.; Häring, A.M. Community financing for sustainable food and farming: A proximity perspective. Agric. Hum. Values 2022, 39, 1063–1075. doi:10.1007/s10460-022-10304-7. | [34] |

| Blättel-Mink, B.; Boddenberg, M.; Gunkel, L.; Schmitz, S.; Vaessen, F. Beyond the market—New practices of supply in times of crisis: The example community-supported agriculture. Int. J. Consumer Studies 2017, 41, 415–421. doi:10.1111/ijcs.12351. | [60] |

| Bonfert, B. Community-supported agriculture networks in Wales and Central Germany: Scaling up, out, and deep through local collaboration. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7419. doi:10.3390/su14127419. | [52] |

| Carlson, L.A.; Bitsch, V. Applicability of transaction cost economics to understanding organizational structures in solidarity-based food systems in Germany. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1095. doi:10.3390/su11041095. | [35] |

| Darkhani, F. Investigating the role of women producers in alternative food networks implementing organic farming in Berlin Brandenburg. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1294940. doi:10.3389/fsufs.2024.1294940. | [53] |

| Degens, P.; Lapschieß, L. Community-supported agriculture as food democratic experimentalism: Insights from Germany. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1081125. doi:10.3389/fsufs.2023.1081125. | [36] |

| Diekmann, M.; Theuvsen, L. Non-participants interest in CSA – Insights from Germany. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 69, 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.04.006. | [54] |

| Diekmann, M.; Theuvsen, L. Value structures determining community supported agriculture: insights from Germany. Agric. Hum. Values 2019, 36, 733–746. doi:10.1007/s10460-019-09950-1. | [55] |

| Doernberg, A.; Zasada, I.; Bruszewska, K.; Skoczowski, B.; Piorr, A. Potentials and limitations of regional organic food supply: A qualitative analysis of two food chain types in the Berlin Metropolitan Region. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1125. doi:10.3390/su8111125. | [67] |

| Follmann, A.; Viehoff, V. A green garden on red clay: Creating a new urban common as a form of political gardening in Cologne, Germany. Local Environ. 2015, 20, 1148–1174. doi:10.1080/13549839.2014.894966. | [71] |

| Gruber, S. Personal trust and system trust in the sharing economy: A comparison of community- and platform-based models. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 581299. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.581299. | [62] |

| Guerrero Lara, L.; Kapusta, B.; Duncan, J.; Feola, G. Organising for political advocacy—the case of the Netzwerk Solidarische Landwirtschaft. Int. J. Polit. Cult. Soc. 2025, 1-32. doi:10.1007/s10767-025-09537-1. | [72] |

| Guerrero Lara, L.; Feola, G.; Driessen, P. Drawing boundaries: Negotiating a collective ‘we’ in community-supported agriculture networks. J. Rural Stud. 2024, 106, 103197. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2024.103197. | [73] |

| Hennchen, B.; Pregernig, M. Organizing joint practices in urban food initiatives—A comparative analysis of gardening, cooking and eating together. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4457. doi:10.3390/su12114457. | [37] |

| Hennchen, B.; Schäfer, M. Do sustainable food system innovations foster inclusiveness and social cohesion? A comparative study. Front. Sustain. 2022, 3, 921169. doi:10.3389/frsus.2022.921169. | [56] |

| Martens, K.; Rogga, S.; Hardner, U.; Piorr, A. Examining proximity factors in public-private collaboration models for sustainable agri-food system transformation: A comparative study of two rural communities. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1248124. doi:10.3389/fsufs.2023.1248124. | [38] |

| Mayer, H.; Knox, P.L. Slow cities: Sustainable places in a fast world. J. Urban Aff. 2006, 28, 321–334. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9906.2006.00298.x. | [68] |

| Meyer, J.M.; Hassler, M. Re-thinking knowledge in community-supported agriculture to achieve transformational change towards sustainability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13388. doi:10.3390/su151813388. | [63] |

| Middendorf, M.; Rommel, M. Understanding the diversity of community supported agriculture: A transdisciplinary framework with empirical evidence from Germany. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1205809. doi:10.3389/fsufs.2024.1205809. | [39] |

| Opitz, I.; Zoll, F.; Zasada, I.; Doernberg, A.; Siebert, R.; Piorr, A. Consumer-producer interactions in community-supported agriculture and their relevance for economic stability of the farm – An empirical study using an analytic hierarchy process. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 68, 22–32. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.03.011. | [40] |

| Opitz, I.; Specht, K.; Piorr, A.; Siebert, R.; Zasada, I. Effects of consumer-producer interactions in alternative food networks on consumers’ learning about food and agriculture. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2017, 25, 181–191. https://doi.org/10.1515/mgr-2017-0016. | [41] |

| Parot, J.; Wahlen, S.; Schryro, J.; Weckenbrock, P. Food justice in community supported agriculture – differentiating charitable and emancipatory social support actions. Agric. Hum. Values 2024, 41, 685–699. doi:10.1007/s10460-023-10511-w. | [64] |

| Rogge, N.; Theesfeld, I.; Strassner, C. The potential of social learning in community gardens and the impact of community heterogeneity. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 2020, 24, 100351. doi:10.1016/j.lcsi.2019.100351. | [42] |

| Rogge, N.; Theesfeld, I. Categorizing urban commons: Community gardens in the Rhine-Ruhr agglomeration, Germany. Int. J. Comm. 2018, 12, 251–274. doi:10.18352/ijc.854. | [44] |

| Rogge, N.; Theesfeld, I.; Strassner, C. Social sustainability through social interaction—A national survey on community gardens in Germany. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1085. doi:10.3390/su10041085. | [43] |

| Rombach, M.; Bitsch, V. Food movements in Germany: Slow food, food sharing, and dumpster diving. IFAMA 2015, 18, 1-24. doi:10.22004/ag.econ.208398. | [57] |

| Rosman, A.; MacPherson, J.; Arndt, M.; Helming, K. Perceived resilience of community supported agriculture in Germany. Agric. Syst. 2024, 220, 104068. doi:10.1016/j.agsy.2024.104068. | [50] |

| Rosol, M.; Barbosa, R. Moving beyond direct marketing with new mediated models: Evolution of or departure from alternative food networks? Agric. Hum. Values 2021, 38, 1021–1039. doi:10.1007/s10460-021-10210-4. | [45] |

| Rosol, M. On the significance of alternative economic practices: Reconceptualizing alterity in alternative food networks. Econ. Geogr. 2020, 96, 52–76. doi:10.1080/00130095.2019.1701430. | [19] |

| Schäfer, M.; Hielscher, S.; Haas, W.; Hausknost, D.; Leitner, M.; Kunze, I.; Mandl, S. Facilitating low-carbon living? A comparison of intervention measures in different community-based initiatives. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1047. doi:10.3390/su10041047. | [46] |

| Schmidt, J.; Egli, L.; Gaspers, M.; Zech, M.; Gastinger, M.; Rommel, M. Conversion to community-supported agriculture—pathways, motives and barriers for German farmers. Reg. Environ. Change 2025, 25, 1-14. doi:10.1007/s10113-024-02332-2. | [58] |

| Spanier, J. Radical rural place-making? Agricultural grassroots initiatives in the everyday negotiation of the European countryside. J. Rural Stud. 2025, 118, 103676. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2025.103676. | [70] |

| Spanier, J.; Guerrero Lara, L.; Feola, G. A one-sided love affair? On the potential for a coalition between degrowth and community-supported agriculture in Germany. Agric. Hum. Values 2024, 41, 25–45. doi:10.1007/s10460-023-10462-2. | [74] |

| Véron, O. “It’s about how you use your privilege”: Privilege, power, and social (in)justice in Berlin’s community food spaces. Antipode 2024, 56, 1949–1974. doi:10.1111/anti.13048. | [65] |

| Vicente-Vicente, J.L.; Borderieux, J.; Martens, K.; González-Rosado, M.; Walthall, B. Scaling agroecology for food system transformation in metropolitan areas: Agroecological characterization and role of knowledge in community-supported agriculture farms connected to a food hub in Berlin, Germany. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 47, 857–889. doi:10.1080/21683565.2023.2187003. | [66] |

| Voge, J.; Newiger-Dous, T.; Ehrlich, E.; Ermann, U.; Ernst, D.; Haase, D.; Lindemann, I.; Thoma, R.; Wilhelm, E.; Priess, J.; et al. Food loss and waste in community-supported agriculture in the region of Leipzig, Germany. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2023, 21, 2242181. doi:10.1080/14735903.2023.2242181. | [69] |

| Wittenberg, J.; Gernert, M.; El Bilali, H.; Strassner, C. Towards sustainable urban food systems: Potentials, impacts and challenges of grassroots initiatives in the foodshed of Muenster, Germany. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13595. doi:10.3390/su142013595. | [47] |

| Zech, M.; Paech, N.; Schmidt, J.; Palliwoda, J.; Rommel, M. Innovationsbarrieren bei der Umstellung auf Solidarische Landwirtschaft. Die Rolle von Systemdienstleistern. GAIA 2025, 34, 10–16. doi:10.14512/gaia.34.1.6. | [48] |

| Zoll, F.; Harder, A.; Manatsa, L.N.; Friedrich, J. Motivations, changes and challenges of participating in food-related social innovations and their transformative potential: Three cases from Berlin (Germany). Agric. Hum. Values 2024, 41, 1481–1502. doi:10.1007/s10460-024-10561-8. | [59] |

| Zoll, F.; Kirby, C.K.; Specht, K.; Siebert, R. Exploring member trust in German community-supported agriculture: A multiple regression analysis. Agric. Hum. Values 2023, 40, 709–724. doi:10.1007/s10460-022-10386-3. | [61] |

| Zoll, F.; Specht, K.; Siebert, R. Alternative = transformative? Investigating drivers of transformation in alternative food networks in Germany. Sociol. Rural. 2021, 61, 638–659. doi:10.1111/soru.12350. | [49] |

| Zoll, F.; Specht, K.; Opitz, I.; Siebert, R.; Piorr, A.; Zasada, I. Individual choice or collective action? Exploring consumer motives for participating in alternative food networks. Int. J. Consumer Studies 2018, 42, 101–110. doi:10.1111/ijcs.12405. | [51] |

Appendix C

Appendix D

| Source | Literature Review | Documentary Analysis, Website | Interviews | Fieldwork, Participatory Observation | Expert Workshop, Focus Group | Survey |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [34] | Document analysis reviewing websites of selected cases, news articles, and crowdfunding campaigns | 4 semi-structured interviews with representatives of the selected cases | Short online survey to obtain an overview | |||

| [60] | 10 semi-structured interviews with members and farmers of 3 selected farms | 570 standardized surveys addressing the members and farmers of all existing CSA farms in Germany at the time of circulation | ||||

| [52] | Document analyses of CSA publications and online posts | 9 semi-structured interviews with CSA actors (local CSA members and regional network organizers) | Participatory observations at CSA network gathering | |||

| [35] | Archival data: copies of membership agreements, bylaws, and websites | In-depth interviews (general interview guide) with CSA participants and consultants from the CSA network; additional interviews conducted during the visits to the production cites of 4 CSA | Participatory observation as a seminar, visit to the annual membership meeting of the CSA network, field notes from production site visits of 4 CSA, field notes from workday at production site | |||

| [53] | 7 interviews (3 CSA, 2 food cooperatives, and 2 self-harvest gardens) were conducted with active female respondents (producers, prosumers, and consumers) with 17 open-ended questions using Zoom (except for 3 interviews that were conducted face-to-face) | |||||

| [36] | Analyzing existing literature | Analyzing documents and webpages of CSA organizations | 10 semi-standardized expert interviews with members of single CSA, the CSA network, consultants, and further experts in the field | 16 participatory observations in meetings (carried out in every semi-annual conference of the CSA network since fall 2020), other network meetings, and workshops hosted by the CSA Network | ||

| [54] | Literature analysis | Standardized survey with 1139 participants | ||||

| [55] | Standardized survey (Schwartz’s Portrait Value Questionnaire) with 204 CSA members | |||||

| [67] | 8 in-depth interviews with 4 farmers, 2 participating consumers, 1 consultant, and 1 non-governmental organization | Workshop with 6 purposefully selected practitioners (farmers or participating consumers) from CSA initiatives in the region and 6 experts from policy, administration, and research directly involved in the CSA topic | ||||

| [71] | Analysis of media coverage, publications, websites, and blogs | Interviews | Participatory observation | Focus-group discussion with students and gardeners | ||

| [62] | Interviews with farmers and consumers | |||||

| [72] | Selective literature review to identify key concepts | Internal documents including protocols of council and coordination meetings | 8 semi-structured and 1 in-depth interview with current and former active members of the CSA network | Participatory observations in bi-weekly meetings over one year | 1 focus group interview with the working group on politics of the CSA network | |

| [73] | Web content and documents as well as videos and radio features | 12 semi-structured in-depth interviews with employees, former board and council members, and members (some interviews were conducted online) | Research notes from participatory observations of 3 semi-annual network meetings | |||

| [56] | Literature search with 37 documents for analysis | Secondary information from literature | 2 focus group discussions with shareholders of 1 citizen shareholder company (9 women and 8 man) with a short questionnaire filled out in advance | Survey of shareholders | ||

| [37] | Articles published by local newspapers | 16 semi-structured interviews (participants or people in charge of the respective initiative) | Participatory observations at 2 urban gardening events and 1 cooking event (short protocols with information about initiatives’ procedure, initiatives’ behavior, informal conversations, and group dynamics) | Group discussion | ||

| [38] | Semi-structured interviews (first round: 2 municipalities; second round: 2–3 farmers) | |||||

| [68] | Review of literature | Documentary data: cities’ histories, planning documents, online resource, and newspaper articles | Telephone interviews and 20 semi-structured interviews in both cities (on-site) with elected official, planning staff members, environmental nonprofit representatives, and small business owners | Sight and event visits for participatory observations | ||

| [63] | Semi-structured interviews at 22 CSA farms with owners, farmer, members, and employees in Hesse by telephone or Zoom call (2 directly at the farms) | |||||

| [39] | Literature search: Inaugurated sample of CSA literature (n = 35 publications) starting from 2019 | 6 individual interviews | Participatory observations at 10 non-scientific network conferences | 4 focus groups with 25 participants, various discussions with 16 participants | Survey of all CSA members of the CSA network in Germany (contacted over the CSA network): 81 farms that are part of 70 CSA organizations responded the survey | |

| [40] | 10 surveys with experts (5 CSA farmers, 3 researchers from university and non-university research institutes, and 2 experts from agriculture associations) | |||||

| [41] | 26 guided interviews with consumer and producers | |||||

| [64] | Individual CSA websites and CSA network websites as well as recordings of a series of webinars | 7 semi-structured interviews (2 in Germany) | ||||

| [42] | 123 surveys of leaders or members of the core group of a garden (expected well-founded knowledge) | |||||

| [44] | 11 surveys of leaders or members of core groups of a garden | |||||

| [43] | 123 surveys of leaders or members of the core group of a garden (expected well-founded knowledge) | |||||

| [57] | 25 in-depth, semi-structured interviews face-to-face or over the phone: 10 Slow Food members (5 leading roles and 5 Slow Food Youth movement members between 20–40 years (3 students, 2 people from education and gastronomy)) and 15 dumpster divers (20–30 years old) | |||||

| [50] | 1 in-depth interview | A resilience perception assessment and a Fuzzy-Cognitive-Mapping workshop | Survey with CSA farmers | |||

| [45] | Semi-structured interviews with key informants | Participatory observations in meetings and during collection and open farm days | ||||

| [19] | Analysis of websites, media coverage, grey literature, newsletters, reports, and more | Semi-structured interviews with key actors | Participation in meetings | |||

| [46] | Review of existing academic literature on intentional communities | Review of self-published material such as websites, promotional materials, and academic reports | 2–3 in-depth face-to-face interviews per case with informants (founders and people involved in the area of food) | Site visits | A half-day workshops per case | |

| [58] | Baseline data concerning founding year, location, and certification type | 10 semi-structured interviews (5 on-site and 5 online per Webex) with farmers (management position in the CSA, either on the board or as farm manager) | ||||

| [70] | 30 semi-structured interviews with producers and consumer members of CSA and local residents | Participatory observations (1 week per 2 cases) on each site | ||||

| [74] | German degrowth literature | Documentation analysis of network’s vision and core principles | 19 semi-structured interviews with degrowth scholars and activists with a broad overview of the degrowth community (5 degrowth movement, 5 CSA movement, and 9 individual CSA initiatives) | Participatory observations during network working groups and 4 network conferences | ||

| [65] | Documentary analysis and photographic data gathering | 26 in-depth interviews | Activist ethnography with 10 food initiatives (participatory action research) and informal interviews documented in a research diary | 2 focus groups with activists and participants | ||

| [66] | Walking interviews on-site with 10 farmers | Complemented with ethnographic approaches (participatory observations and spending time or working with the farmers) | ||||

| [69] | For reference data | Documentary method: for analyzing the results of group discussion | Field work with standardized protocol | Group discussion | Standardized survey | |

| [47] | Literature review | Desk research | Face-to-face interviews with 9 long-term, active members with sound knowledge of their initiatives | |||

| [48] | 10 expert interviews (leadership positions: board members or farm managers) | Expert workshop with 19 participants (farmers, gardeners, and representatives from CSA advisory services, CSA consulting, and CSA research) | ||||

| [59] | 15 qualitative, problem-centered interviews (5 community gardens, 4 cooperative supermarkets, and 6 too good to go app) | |||||

| [61] | Cross-sectional study of German CSA members using convenience sampling: survey with 69 questions (not all included in the data analysis) | |||||

| [49] | 26 qualitative interviews (8 producers and 18 consumers) | |||||

| [51] | 18 qualitative interviews (consumers/members) | |||||

| 10 | 18 | 33 | 19 | 9 | 13 |

References

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; Carpenter, S.R.; De Vries, W.; De Wit, C.A.; et al. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 2015, 347, 1259855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommer, B. Transformationstheorien und Ökologie. In Handbuch Umweltsoziologie; Sonnberger, M., Bleicher, A., Groß, M., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2023; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, B.; Schad, M. Sozial-ökologische Transformationskonflikte. Konturen eines Forschungsfeldes. ZfP 2022, 69, 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baecker, D. Poker im Osten: Probleme der Transformationsgesellschaft; Merve Verlag GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ruppenthal, T.; Rückert-John, J. Food shopping and eating habits of young adults. Br. Food J. 2025, 127, 2233–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassehi, A. Kritik der großen Geste: Anders Über die Gesellschaftliche Transformation Nachdenken; C.H. Beck: München, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WBAE. Politik für Eine Nachhaltigere Ernährung: Eine Integrierte Ernährungspolitik Entwickeln und Faire Ernährungsbedingungen Gestalten. Available online: https://www.bmleh.de/SharedDocs/Archiv/Downloads/wbae-gutachten-nachhaltige-ernaehrung.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=3 (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- van der Weele, C.; Feindt, P.; van der Jan Goot, A.; van Mierlo, B.; van Boekel, M. Meat alternatives: An integrative comparison. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 88, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, R.; Rückert-John, J. Innovationen im Feld der Ernährung. In Handbuch Innovationsforschung; Blättel-Mink, B., Schulz-Schaeffer, I., Windeler, A., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger-Erben, M.; Rückert-John, J.; Schäfer, M. Soziale Innovationen für nachhaltigen Konsum: Wissenschaftliche Perspektiven, Strategien der Förderung und gelebte Praxis. In Soziale Innovationen für Nachhaltigen Konsum; Jaeger-Erben, M., Rückert-John, J., Schäfer, M., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2017; pp. 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- El Bilali, H.; Strassner, C.; Ben Hassen, T. Sustainable agri-food systems: Environment, economy, society, and policy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gori, F.; Castellini, A. Alternative food networks and short food supply chains: A systematic literature review based on a case study approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, F. Alternative food networks. In Encyclopedia of Food and Agricultural Ethics; Thompson, P.B., Kaplan, D.M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, D.; DuPuis, E.M.; Goodman, M.K. Alternative Food Networks: Knowledge, Practice, and Politics; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tregear, A. Progressing knowledge in alternative and local food networks: Critical reflections and a research agenda. J. Rural Stud. 2011, 27, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bernardi, P.; Bertello, A.; Venuti, F. Online and on-site interactions within alternative food networks: Sustainability impact of knowledge-sharing practices. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruppenthal, T. The business model of a Benedictine abbey, 1945–1979. J. Manag. Hist. 2020, 26, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosol, M. On the significance of alternative economic practices: Reconceptualizing alterity in alternative food networks. Econ. Geogr. 2020, 96, 52–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Velly, R. Allowing for the projective dimension of agency in analysing alternative food networks. Sociol. Rural. 2019, 59, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel-Villarreal, R.; Vilalta-Perdomo, E.; Hingley, M.; Canavari, M. Rethinking alternative food networks: Unpacking key attributes and overlapping concepts. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 49, 415–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laginová, L.; Hrivnák, M.; Jarábková, J. Organizational models of alternative food networks within the rural–urban interface. Admin. Sci. 2023, 13, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M. Grassroots innovation: A systematic review of two decades of research. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 973–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckartz, U.; Rädiker, S. Qualitative Content Analysis: Methods, Practice and Software, 2nd ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA; London, UK; New Delhi, India; Singapore; Washington, DC, USA; Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken, 13th ed.; Julius Beltz GmbH & Co. KG: Weinheim, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ruppenthal, T.; Schweers, N. Eye tracking as an instrument in consumer research to investigate food from a marketing perspective: A bibliometric and visual analysis. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 1095–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruppenthal, T. Eye-tracking studies on sustainable food consumption: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egli, L.; Rüschhoff, J.; Priess, J. A systematic review of the ecological, social and economic sustainability effects of community-supported agriculture. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1136866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrendt, G.; Peter, S.; Sterly, S.; Häring, A.M. Community financing for sustainable food and farming: A proximity perspective. Agric. Hum. Values 2022, 39, 1063–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, L.A.; Bitsch, V. Applicability of transaction cost economics to understanding organizational structures in solidarity-based food systems in Germany. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degens, P.; Lapschieß, L. Community-supported agriculture as food democratic experimentalism: Insights from Germany. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1081125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennchen, B.; Pregernig, M. Organizing joint practices in urban food initiatives—A comparative analysis of gardening, cooking and eating together. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, K.; Rogga, S.; Hardner, U.; Piorr, A. Examining proximity factors in public-private collaboration models for sustainable agri-food system transformation: A comparative study of two rural communities. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1248124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middendorf, M.; Rommel, M. Understanding the diversity of community supported agriculture: A transdisciplinary framework with empirical evidence from Germany. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1205809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opitz, I.; Zoll, F.; Zasada, I.; Doernberg, A.; Siebert, R.; Piorr, A. Consumer-producer interactions in community-supported agriculture and their relevance for economic stability of the farm—An empirical study using an analytic hierarchy process. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 68, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opitz, I.; Specht, K.; Piorr, A.; Siebert, R.; Zasada, I. Effects of consumer-producer interactions in alternative food networks on consumers’ learning about food and agriculture. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2017, 25, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogge, N.; Theesfeld, I.; Strassner, C. The potential of social learning in community gardens and the impact of community heterogeneity. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 2020, 24, 100351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogge, N.; Theesfeld, I.; Strassner, C. Social sustainability through social interaction—A national survey on community gardens in Germany. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogge, N.; Theesfeld, I. Categorizing urban commons: Community gardens in the Rhine-Ruhr agglomeration, Germany. Int. J. Comm. 2018, 12, 251–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosol, M.; Barbosa, R. Moving beyond direct marketing with new mediated models: Evolution of or departure from alternative food networks? Agric. Hum. Values 2021, 38, 1021–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, M.; Hielscher, S.; Haas, W.; Hausknost, D.; Leitner, M.; Kunze, I.; Mandl, S. Facilitating low-carbon living? A comparison of intervention measures in different community-based initiatives. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittenberg, J.; Gernert, M.; El Bilali, H.; Strassner, C. Towards sustainable urban food systems: Potentials, impacts and challenges of grassroots initiatives in the foodshed of Muenster, Germany. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zech, M.; Paech, N.; Schmidt, J.; Palliwoda, J.; Rommel, M. Innovationsbarrieren bei der Umstellung auf Solidarische Landwirtschaft. Die Rolle von Systemdienstleistern. GAIA 2025, 34, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoll, F.; Specht, K.; Siebert, R. Alternative = transformative? Investigating drivers of transformation in alternative food networks in Germany. Sociol. Rural. 2021, 61, 638–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosman, A.; MacPherson, J.; Arndt, M.; Helming, K. Perceived resilience of community supported agriculture in Germany. Agric. Syst. 2024, 220, 104068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoll, F.; Specht, K.; Opitz, I.; Siebert, R.; Piorr, A.; Zasada, I. Individual choice or collective action? Exploring consumer motives for participating in alternative food networks. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2018, 42, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfert, B. Community-supported agriculture networks in Wales and Central Germany: Scaling up, out, and deep through local collaboration. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darkhani, F. Investigating the role of women producers in alternative food networks implementing organic farming in Berlin Brandenburg. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1294940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diekmann, M.; Theuvsen, L. Non-participants interest in CSA—Insights from Germany. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 69, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diekmann, M.; Theuvsen, L. Value structures determining community supported agriculture: Insights from Germany. Agric. Hum. Values 2019, 36, 733–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennchen, B.; Schäfer, M. Do sustainable food system innovations foster inclusiveness and social cohesion? A comparative study. Front. Sustain. 2022, 3, 921169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rombach, M.; Bitsch, V. Food movements in Germany: Slow food, food sharing, and dumpster diving. IFAMA 2015, 18, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.; Egli, L.; Gaspers, M.; Zech, M.; Gastinger, M.; Rommel, M. Conversion to community-supported agriculture—Pathways, motives and barriers for German farmers. Reg. Environ. Change 2025, 25, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoll, F.; Harder, A.; Manatsa, L.N.; Friedrich, J. Motivations, changes and challenges of participating in food-related social innovations and their transformative potential: Three cases from Berlin (Germany). Agric. Hum. Values 2024, 41, 1481–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blättel-Mink, B.; Boddenberg, M.; Gunkel, L.; Schmitz, S.; Vaessen, F. Beyond the market—New practices of supply in times of crisis: The example community-supported agriculture. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2017, 41, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoll, F.; Kirby, C.K.; Specht, K.; Siebert, R. Exploring member trust in German community-supported agriculture: A multiple regression analysis. Agric. Hum. Values 2023, 40, 709–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruber, S. Personal trust and system trust in the sharing economy: A comparison of community- and platform-based models. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 581299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, J.M.; Hassler, M. Re-thinking knowledge in community-supported agriculture to achieve transformational change towards sustainability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parot, J.; Wahlen, S.; Schryro, J.; Weckenbrock, P. Food justice in community supported agriculture—Differentiating charitable and emancipatory social support actions. Agric. Hum. Values 2024, 41, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Véron, O. “It’s about how you use your privilege”: Privilege, power, and social (in)justice in Berlin’s community food spaces. Antipode 2024, 56, 1949–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Vicente, J.L.; Borderieux, J.; Martens, K.; González-Rosado, M.; Walthall, B. Scaling agroecology for food system transformation in metropolitan areas: Agroecological characterization and role of knowledge in community-supported agriculture farms connected to a food hub in Berlin, Germany. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 47, 857–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doernberg, A.; Zasada, I.; Bruszewska, K.; Skoczowski, B.; Piorr, A. Potentials and limitations of regional organic food supply: A qualitative analysis of two food chain types in the Berlin Metropolitan Region. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, H.; Knox, P.L. Slow cities: Sustainable places in a fast world. J. Urban Aff. 2006, 28, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voge, J.; Newiger-Dous, T.; Ehrlich, E.; Ermann, U.; Ernst, D.; Haase, D.; Lindemann, I.; Thoma, R.; Wilhelm, E.; Priess, J.; et al. Food loss and waste in community-supported agriculture in the region of Leipzig, Germany. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2023, 21, 2242181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanier, J. Radical rural place-making? Agricultural grassroots initiatives in the everyday negotiation of the European countryside. J. Rural Stud. 2025, 118, 103676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follmann, A.; Viehoff, V. A green garden on red clay: Creating a new urban common as a form of political gardening in Cologne, Germany. Local Environ. 2015, 20, 1148–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero Lara, L.; Kapusta, B.; Duncan, J.; Feola, G. Organising for political advocacy—The case of the Netzwerk Solidarische Landwirtschaft. Int. J. Polit. Cult. Soc. 2025, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero Lara, L.; Feola, G.; Driessen, P. Drawing boundaries: Negotiating a collective ‘we’ in community-supported agriculture networks. J. Rural Stud. 2024, 106, 103197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanier, J.; Guerrero Lara, L.; Feola, G. A one-sided love affair? On the potential for a coalition between degrowth and community-supported agriculture in Germany. Agric. Hum. Values 2024, 41, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. VOSviewer Manual. 2023. Available online: https://www.vosviewer.com/documentation/Manual_VOSviewer_1.6.20.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Radhakrishnan, S.; Erbis, S.; Isaacs, J.A.; Kamarthi, S. Correction: Novel keyword co-occurrence network-based methods to foster systematic reviews of scientific literature. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, V.; Nair, A.M.; Meyer, D.F. Nudges and choice architecture in public policy: A bibliometric analysis. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 2023, 104, 102020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, J.; Bauin, S.; Courtial, J.-P.; Whittaker, J. Policy and the mapping of scientific change: A co-word analysis of research into environmental acidification. Scientometrics 1988, 14, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Search | Keywords | Results | Duplicates | Included |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | community-supported agriculture AND alternative food network | 46 | 3 | 18 |

| 2. | community-supported agriculture AND Germany | 83 | 36 | 7 |

| 3. | alternative-food network AND Germany | 62 | 28 | 2 |

| 4. | alternative food network AND Germany | 402 | 66 | 3 |

| 5. | alternative-food network AND Germany AND social innovation | 8 | 7 | 0 |

| 6. | alternative food network AND Germany AND social innovation | 34 | 34 | 1 |

| 7. | social food movement AND Germany | 360 | 18 | 4 |

| 8. | food movement AND Germany AND community | 287 | 109 | 4 |

| 9. | community supported agriculture AND alternative food network * OR cooperative * AND alternative food network * | 479 | 60 | 2 |

| 10. | ecovillage AND Germany | 7 | 1 | 1 |

| 1768 | 362 | 42 |

| Inclusion Criteria |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Exclusion criteria |

|

|

|

| # | Category | Source |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Governance, organizational structures, and joint practices | [19,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51] |

| 2 | Values, motivations, and participation drivers | [35,36,43,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61] |

| 3 | Social cohesion, relationships, and impacts | [34,42,43,56,59,61,62,63,64,65] |

| 4 | Knowledge, information, and learning flows | [39,41,57,63,66] |

| 5 | Economic viability and market dynamics | [19,34,38,45,48,49,50,59,63,66,67,68] |

| 6 | Agroecology, resilience, and transformation potential | [19,34,38,47,50,63,66,69] |

| 7 | Framework development | [19,39,40,41,45,67,70] |

| 8 | Social justice, power, and privilege | [19,45,53,65] |

| 9 | Urban, cultural and social innovation | [19,38,45,47,49,56,59,60,68,69,71] |

| 10 | Political advocacy, boundary work, and institutional support | [45,47,65,70,71,72,73,74] |

| Source | Literature Review | Documentary Analysis, Website | Interviews | Fieldwork, Participatory Observation | Expert Workshop, Focus Group | Survey |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [34] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| [60] | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| [52] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| [35] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| [53] | ✓ | |||||

| [36] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| [54] | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| [55] | ✓ | |||||

| [67] | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| [71] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| [62] | ✓ | |||||

| [72] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| [73] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| [56] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| [37] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| [38] | ✓ | |||||

| [68] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| [63] | ✓ | |||||

| [39] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| [40] | ✓ | |||||

| [41] | ✓ | |||||

| [64] | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| [42] | ✓ | |||||

| [44] | ✓ | |||||

| [43] | ✓ | |||||

| [57] | ✓ | |||||

| [50] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| [45] | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| [19] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| [46] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| [58] | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| [70] | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| [74] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| [65] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| [66] | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| [69] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| [47] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| [48] | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| [59] | ✓ | |||||

| [61] | ✓ | |||||

| [49] | ✓ | |||||

| [51] | ✓ | |||||

| 10 | 18 | 33 | 19 | 9 | 13 |

| Forms of Communitization | Source |

|---|---|

| Community, urban and self-harvest gardens or public space food projects | [41], [42], [43], [44], [47] 3, [49], [51], [53], [59], [65] 2, [71] 1 |

| Food cooperatives or cooperative initiatives | [19] 5, [34], [41], [45] 4, [49], [51], [53], [56], [59], [65] 6 |

| Food sharing and redistribution initiatives (also over digital platforms) | [45] 7, [47] 9, [57], [59] 10, [65] 8 |

| Community-supported agriculture networks | [35], [36], [40], [41], [52] 11, [64], [72], [73], [74] |

| Community-supported agriculture | [35], [36], [39], [40], [41], [47] 15, [48], [49], [50], [51], [52] 12, [53], [54], [55], [56], [58], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64] 13, [65] 14, [66], [67], [69], [70], [74] |

| Ecovillage and commune | [46] 16, [47] 17, [70] |

| Food initiatives | [37], [47] 20, [57], [65] 18, [66] 19, [68] |

| Policy, municipal, and institutional partnerships | [36], [38], [40], [66] 21 |

| Community-Oriented Sustainable Food Systems (Red) | Participatory Framework for Community Commons (Green) | Political-Ecological Agricultural Networks (Blue) | Alternative Food Systems (Yellow) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consumption (8) | Sustainability (8) | Politics (9) | Systems (13) |

| Community-supported agriculture (4) | Governance (5) | Agriculture (8) | Alternative food networks (5) |

| Farmers (4) | Collective action (3) | Networks (6) | Local food (4) |

| Motivations (4) | Commons (3) | Embeddedness (5) | Reflections (4) |

| Consumer (3) | Community gardens (3) | Geography (4) | |

| Food (3) | Framework (3) | Supply chains (4) | |

| Life-style behaviors (3) | Innovation (3) | ||

| Transitions (3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ruppenthal, T.; Rückert-John, J. Systematic Literature Review on Forms of Communitization that Feature Alternative Nutritional Practices. Sustainability 2026, 18, 879. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020879

Ruppenthal T, Rückert-John J. Systematic Literature Review on Forms of Communitization that Feature Alternative Nutritional Practices. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):879. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020879

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuppenthal, Tonia, and Jana Rückert-John. 2026. "Systematic Literature Review on Forms of Communitization that Feature Alternative Nutritional Practices" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 879. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020879

APA StyleRuppenthal, T., & Rückert-John, J. (2026). Systematic Literature Review on Forms of Communitization that Feature Alternative Nutritional Practices. Sustainability, 18(2), 879. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020879