Abstract

In the pursuit of high-quality economic development, addressing the challenge of high pollution and carbon emissions has become a critical issue. The rapid advancement of digital technology offers novel opportunities and tools to effectively mitigate these challenges. This study examines how digital technology empowerment can enhance the effectiveness of low-carbon city pilot (LCCP) policies in mitigating high pollution and carbon emissions, thereby improving green economic efficiency (GEE), using data from 283 Chinese cities between 2006 and 2021. The method adopted is a DID framework tailored for settings with staggered treatment adoption. Our analysis focuses on the low-carbon city pilot initiative, examining its consequences and how it interacts with digital technology. The results indicate that (1) the LCCP policy significantly promotes green economic efficiency; (2) digital technology empowerment demonstrates a substantial positive moderating impact upon the policy outcome, thus considerably reinforcing low-emission pilot policies’ improvement effect on GEE; (3) there are regional variations in the policy effectiveness, with the eastern region showing the most pronounced improvement, followed by the central region, while the western region exhibits a relatively lower response. This study provides theoretical and empirical support for further integrating digital technology with low-carbon policies and advancing urban green and high-quality development.

1. Introduction

The global climate crisis is becoming increasingly urgent, making low-carbon development a universal consensus and a common direction for action among nations worldwide. A special document was released by NDRC in 2010, the Notice on Carrying out Pilot Work in Low-Carbon Provinces, Autonomous Regions and Low-Carbon Cities, to systematically deploy the innovation of emission reduction mechanisms in various regions. The document identified five provinces of Guangdong, Liaoning, Hubei, Shaanxi and Yunnan and eight cities, including Tianjin, Chongqing, Xiamen and Hangzhou, as the first batch of policy pilots [1]. On this basis, the pilot scope has undergone two expansionary promotions in 2012 and 2017, respectively, gradually building a low-carbon development practice network in multi-level administrative regions, forming a three-dimensional policy network covering the eastern, central and western regions and taking into account the differences in resource endowments. This systematic, staggered implementation of LCCPs across a large, heterogeneous country like China provides a compelling quasi-natural experiment for investigating the mechanisms and effectiveness of low-carbon policies.

However, cities continue to face severe environmental challenges despite LCCP implementation. Widespread reliance on carbon-intensive technologies, including coal-fired power generation, conventional internal combustion engines, and energy-intensive industrial processes, not only contributes significantly to CO2 emissions but also releases additional pollutants such as sulfur oxides, nitrogen oxides, and particulate matter. This challenge of pollution and carbon intensity represents a critical bottleneck for urban sustainable development. Concurrently, digital transformation offers new opportunities to address these challenges. The Chinese government has recognized digital technology’s crucial role in socioeconomic development, formulating strategic plans including the “14th Five-Year Plan” for digital economy development that emphasizes deep integration between digital technology and traditional industries. China’s concurrent pursuit of digital transformation and low-carbon transition, combined with significant regional disparities, creates a unique opportunity to examine how digital empowerment enhances GEE across different developmental contexts.

Existing research has established the LCCP policy’s effectiveness in reducing carbon emissions [2,3,4] and improving green total factor productivity [5]. Separate literature streams have identified various GEE determinants, including green credit [6], digital economy development [7], and technological innovation [8,9]. Nevertheless, a significant research gap persists in understanding synergistic mechanisms between digital technology empowerment and low-carbon policies—particularly how digital technologies might enhance LCCP effectiveness in addressing pollution and carbon emissions simultaneously.

This study aims to bridge this research void by developing an integrated analytical frame-work examining how digital technology empowerment enhances LCCP policy effectiveness in improving GEE. Specifically, we empirically test three hypotheses: LCCP policies directly promote GEE; digital technology empowerment strengthens this relationship through positive moderating effects; and these effects exhibit significant regional heterogeneity, which arise from divergent levels of economic development and resource endowments.

Methodologically, we employ a multi-period difference-in-differences approach using panel data from 283 Chinese cities (2006–2021), with the study period specifically chosen to include several years prior to policy implementation (2006–2009) to establish a reliable baseline, while the extended timeframe through 2021 captures both short-term and long-term policy effects, supplemented by robust identification strategies including parallel trends tests, placebo tests, and propensity score matching. Our empirical analysis yields three key findings: first, LCCP implementation significantly improves GEE; second, digital technology empowerment substantially enhances this positive effect; and third, policy effectiveness demonstrates clear regional patterns, with eastern China showing the most pronounced improvements, followed by central and western regions.

This research contributes significant theoretical and practical insights by developing an integrated framework that enhances understanding of low-carbon policy outcomes, reveals mechanisms through which digital technology fosters green economic development, and provides scientific evidence for optimizing low-carbon city construction policies to advance the transition toward a green economy.

2. Literature Review

Since 2010, when China launched the LCCP policy, many scholars have jointly studied the carbon emission reduction effect of the LCCP policy. Dong Mei [2] used the synthetic control method to conduct an empirical analysis, taking per capita carbon emissions and carbon intensity as the explanatory variables, and her research showed that the pilot policy of low-carbon cities not only reduced carbon dioxide emissions, but also had a positive effect on emissions reduction for industrial pollutants. Yang et al. [3] used the difference-in-difference method at multiple time points to evaluate the policy treatment effect of LCCP policies on regional carbon emission levels with carbon dioxide emissions as the explanatory variable. In view of the quasi-natural experimental characteristics of China’s carbon trading pilot market, Yang et al. [4] employed the synthetic control approach. It examined the consequences of the environmental initiative for emissions in the pilot areas. Their study demonstrated that China’s carbon trading pilot policy has achieved significant results in promoting carbon emission reduction. Shang Haiyan [5] constructed a combined PSM-DID framework, mitigating selection bias. The study confirmed that the policy led to marked gains in the efficiency of resource and environmental synergy in pilot zones. Recent studies have shifted focus towards examining the multifaceted dimensions of factors influencing carbon emissions, revealing marked differences in the effects of distinct dimensions—such as energy efficiency versus energy structure, types of green technology innovation, and the bias of technological progress—on carbon reduction [10,11,12].

The drivers of GEE have been extensively examined in the literature. According to Guo, L. et al. [6] verifies that environmentally oriented finance significantly boosts eco-economic performance. Kong, L. et al. [7] indicates that progress in digitalization serves to facilitate enhancements in environmental economic outcomes. He Xingxing et al. [13] empirically analyzed the synergistic effects of fintech and digital economy have significantly improved the promotion and spillover effects of green economic efficiency, highlighting the “1 + 1 > 2”. Yin et al. [14] found that new consumption can significantly improve the efficiency of the green economy. Furthermore, scientific and technological innovation exerts a significant influence on green economic efficiency, with variations in the magnitude of this impact observed across regions and city tiers [8,9]. Related research also encompasses sustainable development [15,16], ecological efficiency [17,18], and energy conservation and emission reduction [19,20].

A review of the existing studies shows that prevailing research primarily examines how LCCP policies cut emissions. Numerous academics have deeply debated the drivers of GEE, with mixed conclusions. There is little literature on the synergistic effect of LCCP policies and digital technologies in solving the problem of “high pollution and carbon emissions”. From this synergistic perspective, this study provides more targeted and systematic policy recommendations for the construction of low-carbon cities.

3. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

The LCCP policy is theorized to enhance green economic efficiency through structural optimization mechanisms. By reallocating production factors from traditional energy-intensive sectors to emerging green industries, the policy addresses both environmental externalities and diminishing marginal returns associated with conventional development patterns [21]. This transition is facilitated through dual channels: supply-side industrial restructuring that phases out polluting industries while fostering green sectors with advanced technologies and market potential, and incentive-driven clustering of innovation factors, including specialized talent, knowledge, and infrastructure, toward low-carbon industries [22]. The theoretical framework developed leads to hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1.

The LCCP policy significantly boosts GEE.

As a key enabling tool for driving low-carbon transition, digital technology’s interaction with the LCCP policy can significantly boost the policy’s positive impact on GEE. At the micro level, digital technology alleviates information asymmetry and reduces transaction costs, thereby accelerating green technology adoption and improving resource allocation efficiency. The traditional model suffers from information gaps that increase transition costs and dampen corporate responsiveness to policies. Digital technology, through enhanced data processing and analytical capabilities, efficiently integrates and interprets internal and external data streams. This capability significantly reduces search costs and replication costs [23], while also breaking spatiotemporal barriers to information dissemination [24]. By providing robust decision-support for energy management and technology selection, digital empowerment lowers the marginal cost of low-carbon transition and directly enhances production efficiency, constituting fundamental inputs to GEE measurement. At the macro level, digital platforms overcome information barriers to enable cross-sectoral resource integration and structural optimization. Legacy systems often fail to achieve efficient resource allocation due to information silos and fragmented markets. Digital platforms facilitate industrial symbiosis and smart outsourcing by connecting previously isolated sectors through enhanced information flow [24]. This system-level coordination promotes industrial restructuring [25] and drives economic structure toward lower-carbon, higher-value activities. The development of digital infrastructure further reinforces this transition by systematically improving regional total factor productivity [26,27], thereby enhancing the structural dimension of GEE. Thus, the following hypothesis is advanced:

Hypothesis 2.

The empowerment derived from technology strengthens how the LCCP policy boosts GEE. This indicates a positive moderating relationship [28].

Policy effectiveness is expected to vary geographically due to imbalanced regional development. Eastern regions benefit from geographical advantages, advanced infrastructure, and lower resource dependence, enabling more efficient resource reallocation toward green innovation and industrial upgrading [29]. Conversely, central and western regions face greater structural constraints due to their reliance on energy-intensive industries and stronger economic growth priorities, potentially leading to implementation delays and attenuated policy effects [30,31]. Thus, the following is proposed:

Hypothesis 3.

LCCP policy’s positive influence in boosting GEE differs across eastern, central, and western zones.

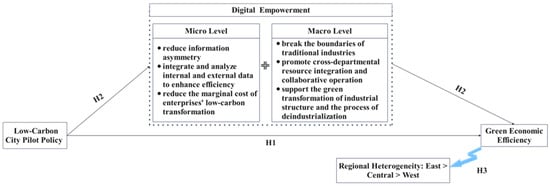

The theoretical framework presented in Figure 1 bridges our conceptual analysis with empirical testing. Theoretically, the micro-level and macro-level mechanisms of digital empowerment outline the causal pathways through which the LCCP policy influences GEE [32,33]. This framework provides direct methodological guidance: we analyze the LCCP policy as an exogenous shock through a staggered DID design that accounts for varied implementation timing across regions. Furthermore, the indicated “Regional Heterogeneity: East > Central > West” is tested by conducting subsample analyses based on regional groupings, a method aligned with established practices [34]. Therefore, Figure 1 not only summarizes the theoretical mechanisms but also directly informs our model specification, variable construction, and empirical strategy.

Figure 1.

From “high pollution and carbon pollution” to green and efficient: the pilot mechanism of digital empowerment to help low-carbon cities.

4. Study Design

4.1. Model Building

In this study, the implementation of the LCCP is regarded as a quasi-natural experiment, and its effect on GEE is explored.

The explained variable in Equation (1) represents the GEE of city i in year t, which is a coefficient reflects the policy’s average treatment effect. A policy dummy variable is set to 1 for treatment group cities and 0 otherwise. The controls Xit covers attributes including economic activity and industrial profile; represents the regional fixed effect; represents the time-fixed effect; represents the idiosyncratic error.

4.2. Variable Setting and Analysis

4.2.1. Explained Variables

GEE serves as the dependent variable. It represents a comprehensive metric that integrates economic output with environmental performance. The theoretical rationale for selecting GEE lies in its function as an integrated measure of development and sustainability, which aligns perfectly with the core research question of how digital empowerment enhances low-carbon policy effectiveness. Unlike conventional economic efficiency measures, GEE incorporates both desirable economic outputs and undesirable environmental outputs, providing a more holistic assessment of urban development quality.

Utilizing the super-efficiency model introduced by Andersen et al. [35] to construct a slack-based measure incorporating slack variables. The methodology is implemented through MATLAB, addressing the methodological constraints of conventional DEA models in processing undesirable outputs [36]. This indicator aims to measure the optimal allocation of economic and ecological resources and the comprehensive benefits of economic activities, and the central objective involves integrating ecological limits within economic performance assessment.

The rationale for employing GEE as our dependent variable is threefold. First, it corresponds directly to the policy objectives of LCCP, which aim to achieve coordinated development of economic growth and environmental protection. Second, it enables quantitative assessment of the synergy between pollution reduction and carbon mitigation, the central focus of our investigation into digital empowerment effects. Third, the comprehensive nature of GEE allows for capturing both the economic and environmental dimensions of policy impacts, providing a more complete evaluation framework than single-dimensional indicators.

This research compiles a multi-year observation set spanning 283 urban centers in China, guided by data accessibility. The sample excludes the Tibet Autonomous Region, Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan, as well as cities such as Sansha, Danzhou, and Qinzhou due to insufficient data. By integrating relevant data on input factors, desirable outputs, and undesirable outputs, urban GEE is measured using the aforementioned model and computational tools.

- (1)

- Input indicators

- ①

- Labor: The number of employees at the end of the year in each prefecture-level city [37] is selected as the labor input.

- ②

- Capital: The fixed capital stock of each prefecture-level city is selected as capital investment, and the perpetual inventory method of Zhang Jun et al. [38] is used for estimation. The formula used is shown in Equation (2):Among them, represents the fixed capital stock of city i in year t, and represents the fixed capital stock of city i in year t−1. represents the depreciation rate. Here it is 9.6%, indicating the total amount of fixed assets formed in the current period.

- ③

- Energy: The total energy consumption of prefecture-level cities is selected as the energy input, which is calculated based on nighttime light data with reference to the practice of Wu Jiansheng et al. [39].

- (2)

- Output indicators

- ①

- Expected output: The GDP of each prefecture-level city is selected to measure.

- ②

- Undesired output: The emissions of the “three industrial wastes” [37] of each prefecture-level city are selected as the measurement index.

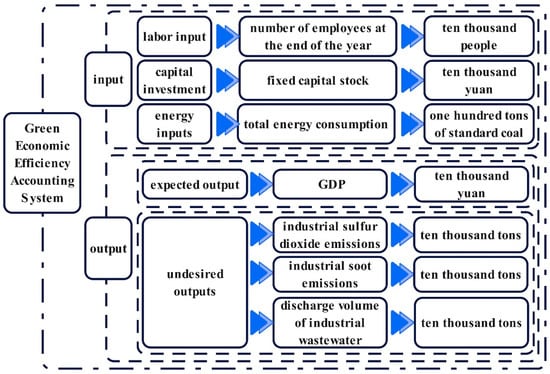

The specific accounting system for green economic efficiency is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

GEE Assessment Metrics.

The research utilizes DEA techniques for urban GEE evaluation, corresponding to the multi-dimensional assessment structure [32,35].

Consider a scenario where n decision-making units (DMU) are to be evaluated in terms of sustainable supply chain performance. Denote each DMU as (). Each DMU utilizes m types of inputs, recorded in the vector , and produces s types of outputs. These outputs are further categorized into desirable outputs and undesirable outputs, where the desirable outputs are denoted as , and the undesirable outputs as . The super-efficiency SBM-DEA model with undesirable outputs is formulated as shown in Equation (3) [36]:

Consistent with the established methodology, performance metrics are derived from the non-oriented efficiency framework. The measures introduced here represent a non-conventional form of slack measurement. To determine suboptimal levels or ideal quantities for production factors, target outcomes, and unintended consequences, the adjustment parameters obtained through the environmental performance specification should be utilized.

4.2.2. Key Explanatory Variable

The core explanatory variable is , with i denoting region and t denoting year. The dichotomous indicator follows this specification: = 1 for urban areas implementing the low-carbon city initiative during a given year; = 0 for non-participating cities or pre-implementation periods.

4.2.3. Control Variables

Prior studies indicate that factors like economic development, industrial structure, urbanization, opening-up, government intervention, and science and technology are selected as the control variables. The specific variables and their definitions are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Selection and definition of benchmark regression variables.

4.2.4. Proxy Variables

From the perspective of digital technology empowerment, the Internet penetration rate and the level of digital technology are employed as proxy variables. The specific definitions of these variables are presented in Table 1. These proxies are justified by their direct theoretical relevance to the mechanisms of emission reduction and green efficiency. The Internet penetration rate, reflecting foundational digital infrastructure, facilitates low-carbon transitions by reshaping demand-side behaviors and business models [40,41,42]. Concurrently, the level of digital technology, measured by patent applications, captures the innovative capacity that drives green technological progress and structural optimization within industries [43,44,45,46]. Together, they comprehensively measure how digital empowerment facilitates the mitigation of pollution and carbon emissions, thereby enhancing green economic efficiency.

4.3. Data Sources

The research covers 283 Chinese prefecture-level urban centers from 2006 through 2021. Owing to constraints in data availability and continuity, the analysis excludes the Tibet Autonomous Region, Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan and cities with substantial data gaps, such as Sansha, Danzhou, and Qinzhou. The dataset was compiled from authoritative statistical sources: China City Statistical Yearbook (2007–2022), China Environment Statistical Yearbook (2007–2022), and Chinese Population Statistical Yearbook (2007–2022 editions), supplemented by various local city statistical yearbooks and government bulletins [47]. For some missing data, the mean interpolation method and the average growth rate method were used to supplement it. At the same time, in order to reduce the interference of outliers on the research results, a 2% tailing process was implemented on the data. Descriptive statistics for the main variables are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics.

4.4. Methodological Framework and Implementation

This study employs an integrated analytical approach combining a multi-period difference-in-differences design with super-efficiency SBM modeling. All analyses were implemented using MATLAB R2021a for efficiency calculations and Stata 18.0 for econometric estimation, with complete code documentation archived for reproducibility. The methodological framework including parallel trends testing, placebo tests, and robustness checks, following established protocols in the literature while providing sufficient detail to enable independent verification and replication of all results.

5. Analysis of Empirical Results

5.1. Benchmark Regression Result Analysis

Table 3 presents the DID regression results under three model specifications. Model (1) excludes temporal and unit-specific influences, while specifications (2) and (3) progressively introduce year and location effects. The estimated coefficients across the three models are 0.0935, 0.1270, and 0.1291. All pass the 1% significance test, demonstrating that LCCP implementation meaningfully enhances GEE after controlling for covariates. These findings validate Hypothesis 1. These findings align with the conclusions of Song et al. [21] and Zhang et al. [22], confirming the positive impact of LCCP policies on environmental performance. However, our study extends existing research by specifically verifying the policy’s effect on green economic efficiency, providing a more comprehensive assessment of policy effectiveness.

Table 3.

Benchmark Regression Results.

According to the analysis of control variables in model (3), indicates that trade openness and innovation capacity exert significant positive effects on GEE. The level of economic development, industrial structure, urbanization and government intervention have inhibiting effects on GEE. This effect may operate through several channels: international openness facilitates knowledge spillovers and technical expertise, enables more efficient resource distribution, and fosters environmentally sustainable growth. Technology can improve energy efficiency and pollution control capabilities, thereby improving the efficiency of the green economy. At a certain stage, the level of economic development may inhibit the efficiency of green economy GEE due to the dependence on growth mode, the impact of consumption structure and the effect of environmental Kuznets curve. Industrial composition characterized by pollution-intensive sectors and poor cross-industry coordination hinders efficient resource utilization and environmental protection, thereby reducing GEE. During urbanization, infrastructure construction pressures, the consumption of resources caused by population agglomeration, and the ecological damage caused by urban expansion may hinder the improvement of green economic efficiency. In terms of government intervention, problems such as unreasonable policy formulation, poor regulatory implementation, and low administrative efficiency will affect the development of green economy, and then inhibit the efficiency of green economy.

5.2. Robustness Test

5.2.1. Parallel Trend Test

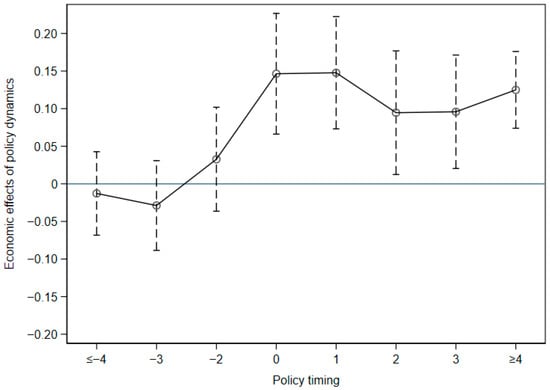

In conducting the parallel trend test, this study builds upon established methodological approaches. Consistent with Tang et al. [48], test samples integrate four-year periods surrounding policy implementation, ensuring robustness through comprehensive time-series coverage. Furthermore, applying the 90% confidence threshold from Zhou et al. [49] to maintain statistical rigor while ensuring dependable findings. The corresponding visualization of pre-intervention patterns appears in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Parallel trend test chart.

From Figure 3, it reveals an adverse economic impact of approximately −0.10 during the initial policy rollout phase. This adverse effect moderates in subsequent periods, diminishing to around −0.05 in period 2 and converging towards neutrality (0) by period 3. Crucially, the analysis demonstrates that the positive economic dividends of the policy are realized only over the longer term, with the effect becoming positive and strengthening to around 0.05 or higher when the policy is sustained for four or more periods. Overall analysis shows no discernible influence on economic outcomes before implementation. However, a significantly positive economic effect emerged after implementation, which later diminished and eventually stabilized.

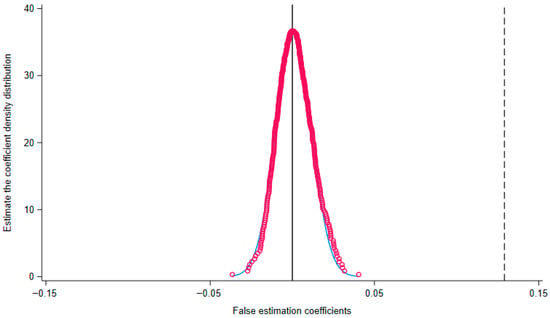

5.2.2. Placebo Test

To examine whether the observed policy effect may be driven by non-policy factors, a placebo test was conducted using a randomized trial to assess the result’s reliability. Specifically, the analysis performed 500 random samples to generate the coefficient estimate empirical distribution, shown in Figure 4. The purpose of this test is to assess whether changes in GEE are indeed attributable to the policy intervention rather than to other omitted variables or stochastic noise. Figure 4 demonstrates that the pseudo DID coefficients are densely grouped near zero while maintaining generally symmetrical characteristics. Such evidence demonstrates that under randomized assignment conditions, the false policy variable does not exert a significant effect on the outcome variable, thereby supporting the validity of the model specification. The clustering of pseudo-treatment coefficients near zero implies the model specification effectively addresses potential confounding from omitted variables or endogenous factors. Consequently, the core findings of the baseline analysis demonstrate high robustness, and it can be reasonably concluded that the policy effect is indeed caused by the policy variable under study, rather than by other unobserved factors. These results further reinforce the reliability of the empirical design and provide strong evidence supporting a causal interpretation of the policy effect.

Figure 4.

Placebo test chart.

5.2.3. Propensity Score Matching

- (1)

- Balance Test for Propensity Score Matching

This paper conducts the matching work by using the 1:1 method. Table 4 displays the PSM balance test findings, where "U" denotes the Unmatched sample and "M" denotes the Matched sample. After matching, the absolute values of the standardized bias of each variable are all controlled within 10% [50]. All covariates in Table 4 demonstrate p-values exceeding 0.05 after matching, indicating no statistically significant differences between the treatment and control groups, and thus failure to reject the null hypothesis of balance. Furthermore, Figure 5 illustrates that before matching, the standardized differences for each variable were considerable, whereas after matching, the deviations are closely distributed around zero. This confirms that systematic differences between groups have been effectively eliminated, supporting the validity of the matching procedure.

Table 4.

Results of PSM equilibrium test.

Figure 5.

Standardized deviation chart of control variables.

- (2)

- Analysis of PSM-DID regression results

Benchmark regression was conducted using the matched sample obtained from the PSM procedure, with Table 5 containing the results. A comparison between Table 3 and Table 5 reveals noticeable differences in the estimated coefficients. Specifically, the DID coefficients—both with and without control variables—show an increase in magnitude, the matched sample reveals a stronger LCCP policy enhancement regarding GEE performance. This suggests that after accounting for sample selection bias through PSM, the estimated policy effect on GEE becomes more pronounced.

Table 5.

Regression Results of PSM-DID.

5.3. Synergistic Effect Test Empowered by Digital Technology

After the above series of analyses, based on the benchmark regression results and robustness results, LCCP implementation significantly enhances GEE, with robust outcomes across benchmark and robustness analyses. Through metrics of network coverage and digital development, this study assesses how technological empowerment works synergistically to boost sustainable economic performance. For this purpose, the following model [47] is set on the basis of Equation (1):

In Equation (4), are the indicators for measuring the empowerment of digital technology, specifically the Internet penetration rate and the level of digital technology. is a coefficient for judging whether digital technology empowerment has taken effect. Other symbols correspond in meaning to those in Equation (1).

Regression findings are summarized in Table 6. Coefficient estimates for rose from 0.1270 and 0.1291 to 0.1605 and 0.3203, maintaining 1% significance. These enhanced values demonstrate digital technology’s empowering role in strengthening GEE gains. Hypothesis 2 holds true. The moderating effect of digital technology supports the findings of Zhao et al. [24] and Lin et al. [26], demonstrating that digital empowerment significantly enhances policy effectiveness. This validates the theoretical mechanism of digital technology in facilitating green transformation, while offering empirical evidence at the city level.

Table 6.

Regression results of Internet penetration rate and digital technology level on the efficiency effect of the green economy.

When measuring the empowerment effect of digital technology by the Internet penetration rate, the coefficient is 0.0217 and there is a significant positive correlation at the 1% level, indicating that measuring the empowerment effect of digital technology by the Internet penetration rate has a significant promoting effect. When measuring the empowerment effect of digital technology by the level of digital technology, the coefficient is 0.0388 and results show a statistically significant positive correlation at the 1% level, verifying that evaluating digital empowerment via technological sophistication generates meaningful improvement effects.

5.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

This paper has verified that the implementation of LCCP policies has a significant positive impact on the efficiency of green economy, and analyzes the synergistic effect of digital technology empowerment. However, heterogeneity analysis reveals varying patterns in green economic efficiency enhancement across different geographic zones. Accordingly, this section will analyze and test the conclusions from different regional aspects. Regional analysis outcomes for eastern, western and central areas are provided in Table 7. The analysis shows that there are obvious differences in the efficiency of green economy between regions. Eastern provinces demonstrate exceptional GEE performance, leveraging robust economic foundations, technological sophistication, and comprehensive infrastructure to maintain national leadership. Central provinces attain intermediate standing, contrasting with western districts’ weaker performance. Such variation emerges fundamentally from restricted economic modernization, innovation resources, and ecological stability, confirming Hypothesis 3. The regional heterogeneity observed is consistent with Hou et al. [30,31] regarding regional differences in policy effectiveness. However, our findings further reveal that digital technology adoption plays a crucial moderating role in these regional variations.

Table 7.

Regional Heterogeneity Results.

The estimated models yield R-squared values between 0 and 0.1. While this indicates that the model explains a limited portion of the outcome variation, such low explanatory power is common in studies leveraging individual-level data [51,52], where unobserved variables often play a substantial role. After including a set of relevant controls, the coefficient on the DID variable remains statistically significant. This significance, corroborated by supplementary tests addressing endogeneity concerns, provides robust evidence of the policy effect.

6. Main Conclusions and Policy Implications

The research examines how digital technology supports LCCP policy in addressing high-pollution high-carbon challenges and boosting GEE, analyzing both theoretical pathways and empirical outcomes. Combining theoretical construction and empirical validation, we derive three fundamental conclusions. Initially, LCCP adoption substantially elevates ecological economic performance. Subsequently, technological enablement exerts considerable positive moderation on policy efficacy, with network expansion and digital progress strengthening policy outcomes. Finally, regional differentiation emerges in efficiency gains, presenting strongest manifestation in eastern provinces, intermediate realization in central districts, and comparatively restrained progression in western sectors.

These insights yield actionable recommendations for promoting low-carbon urban development and improving ecological economic performance.

First, it is essential to promote the deep integration of digital technology with low-carbon policies through differentiated infrastructure deployment. Priority should be given to deepening the application of digital technologies in existing pilot cities with a solid foundation in smart city initiatives or the digital economy. A unified intelligent monitoring platform for energy consumption and emissions could be established to avoid redundant construction. For the central and western regions, demonstration projects for digital emission reduction could be initially launched in key industrial parks, aiming to drive broader adoption through targeted efforts. The government can guide enterprises to participate in digital transformation through fiscal incentives, tax benefits, and green credit, thereby enhancing the marginal benefits of technology application.

Second, territorially differentiated decarbonization pathways need adopting according to regional resource assets and economic conditions. Eastern districts should further capitalize on technological and commercial superiority, prioritizing energy-efficient fields such as sophisticated manufacturing and digital offerings, plus reinforcing industrial chain coordination between carbon mitigation and digital modernization. The central region, building upon industrial relocation and energy structure adjustment, should prioritize green technological upgrades in traditional manufacturing, gradually improving energy efficiency. The western region should prioritize ecological conservation and the development of renewable energy, reasonably controlling the expansion of high-carbon industries, and mitigating ecological and environmental risks while ensuring economic development.

Finally, policy coordination mechanisms should be improved to enhance overall governance efficacy. It is recommended to establish cross-departmental and cross-regional coordination platforms for low-carbon governance, facilitating data sharing and policy synergy to prevent resource waste caused by administrative fragmentation. Under fiscal constraints, priority support should be given to projects that simultaneously reduce emissions, create jobs, and foster technological innovation. Furthermore, attracting private capital to participate in low-carbon digital projects is encouraged to alleviate government funding pressures.

While this study confirms the positive moderating effect of digital technology through the proxy variables of internet penetration rate and number of digital patents, the specific transmission channels require further empirical verification. Future research should employ mediating effect models to quantitatively test how digital empowerment influences green economic efficiency through the mechanisms proposed in our theoretical analysis, specifically examining whether and to what extent digital technology reduces information asymmetry in green technology markets and lowers transaction costs in resource allocation.

Author Contributions

These authors contributed equally to this work. Investigation, H.H. and Y.C.; resources, H.H., Y.C. and Y.Z.; data curation, H.H. and Y.C.; writing—original draft preparation, H.H. and Y.C.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z.; supervision, Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The National Social Science Fund of China (25BTJ028).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, X. How Pilot Low Carbon Cities Influence Urban Green Technology Innovation: A Perspective of Synergy between Government Intervention and Public Participation. J. Lanzhou Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2022, 50, 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, M.; Li, C.F. Net carbon emission reduction effect of the pilot policies in low-carbon provinces. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2020, 30, 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.X.; Yi, Y.C. Are pilot policies for low carbon cities beneficial for carbon reduction—A study based on quasi-natural experiments. J. Hubei Norm. Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2023, 43, 8–18. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.W.; Li, J.L.; Guo, X.Y. The Impact of Carbon Trading Pilots on Emission Mitigation in China: Empirical Evidence from Synthetic Control Method. J. Xi’an Jiaotong Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2021, 41, 93–104+122. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, H.Y. The Impact of Low-carbon City Pilot on Urban Green Total Factor Productivity. J. Commer. Econ. 2024, 1, 188–192. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L.; Tan, W.; Xu, Y. Impact of green credit on green economy efficiency in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 35124–35137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Li, J. Digital economy development and green economic efficiency: Evidence from province-level empirical data in China. Sustainability 2022, 15, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.X.; Chang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, D. Do technological innovations promote urban green development?—A spatial econometric analysis of 105 cities in China. J. Cleaner Prod. 2018, 182, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.Q.; An, Y.F. The relationship between technological innovation and green transformation efficiency in China: An empirical analysis using spatial panel data. Technol. Soc. 2021, 64, 101498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhao, S.G. Low-carbon Emission Reduction Effect of Digital Economy Empowering Regional Green Development. Res. Econ. Manag. 2022, 43, 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, R.; Wang, R.; Qian, L. The Non-linear Impact of Digitalization Level on Corporate Carbon Performance: The Mediating Effect of Green Technology Innovation. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2023, 40, 96–106. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.F. The Effect and Mechanism of Digital Economy on Regional Carbon Emission Intensity. Contemp. Econ. Manag. 2022, 44, 68–78. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.X.; Ruan, J.J. Study on the Efficiency Improvement of Urban Green Economy Driven by Fintech and Digital form the Perspectives of “Enabling” and “Synergising”. Ecol. Econ. 2024, 40, 80–89+107. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, T.B.; Zhao, H.Y.; Zhang, S.B. New consumption and green economic efficiency: Evidence based on the national information consumption pilot program. Ind. Econ. Res. 2024, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Wang, F.; Song, M.; Balezentis, T.; Streimikiene, D. Green innovations for sustainable development of China: Analysis based on the nested spatial panel models. Technol. Soc. 2021, 65, 101593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omri, A. Technological innovation and sustainable development: Does the stage of development matter? Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2020, 83, 106398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Q.; Zhu, J.L.; Li, E.Y.; Meng, Z.; Song, Y. Environmental regulation, green technological innovation, and eco-efficiency: The case of Yangtze river economic belt in China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 155, 119993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasmeen, H.; Tan, Q.; Zameer, H.; Tan, J.; Nawaz, K. Exploring the impact of technological innovation, environmental regulations and urbanization on ecological efficiency of China in the context of COP21. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 274, 111210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Ren, X.; Dong, K.; Dong, X.; Wang, Z. How does technological innovation mitigate CO2 emissions in OECD countries? Heterogeneous analysis using panel quantile regression. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 280, 111818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.T.; Luo, Y. Has technological innovation capability addressed environmental pollution from the dual perspective of FDI quantity and quality? Evidence from China. J. Cleaner Prod. 2020, 258, 120941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.M.; Jin, M.L. Low-Carbon City Pilot Policy and Green Total Factor Energy Efficiency: Theoretical Analysis and Empirical Evidence. Seeking Truth 2025, 52, 70–86. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.B.; Zhou, J.T.; Yan, Z.J. Low-Carbon City Pilot Policy and Total Factor Energy Efficiency Improvement: A Quasi-Natural Experiment from Three Batches of Pilot Policy Implementation. Econ. Rev. 2021, 5, 32–49. [Google Scholar]

- Goldfarb, A.; Tucker, C. Digital Economics. J. Econ. Lit. 2019, 57, 3–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Liu, Z.; Yan, X. Does the Digital Economy Increase Green TFP in Cities? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhao, S.; Wan, X.; Yao, Y. Study on the effect of digital economy on high-quality economic development in China. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S. Can Environmental Information Disclosure Improve Urban Green Economic Efficiency? New Evidence from the Mediating Effects Model. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 747, 920879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Li, Y.; Ren, S.; Wu, H.; Hao, Y. The role of digitalization on green economic growth: Does industrial structure optimization and green innovation matter? J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 325, 116504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.H. Research on the Impact of Low-Carbon City Pilot on Green Economic Efficiency. Ph.D. Thesis, Sichuan Agricultural University, Chengdu, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Wang, M.Y.; Cai, D.-D.; Yin, B. The Impact Effect of Low-Carbon City Pilot Policy on Urban Green Total Factor Productivity. J. Shenyang Univ. Technol. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2025, 18, 185–198. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Y.; Zhai, M.J. Research on the Impact of Low-Carbon Pilot Policy on Urban Green Total Factor Productivity. J. Lanzhou Univ. Financ. Econ. 2025, 1–16. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/62.1213.F.20250326.1708.014 (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Peng, L. Research on the Impact Effect of Low-Carbon City Pilot Policy on Industrial Structure Upgrading. J. Hunan Univ. Financ. Econ. 2024, 40, 79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Zhang, H.; Si, H.; Wang, H. Can the digital economy promote urban green economic efficiency? Evidence from 273 cities in China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 155, 110977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Li, X.; Huo, L. Digital economy, spatial spillover and industrial green innovation efficiency: Empirical evidence from China. Heliyon 2023, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, L.; Ma, Y.; Xu, S. Has the development of digital economy improved the efficiency of China’s green economy? China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2022, 32, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, P.N.; Petersen, N.N. A Procedure for Ranking Efficient Units in Data Envelopment Analysis. Manag. Sci. 1993, 39, 1261–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G. Data Envelopment Analysis Method and MaxDEA Software; Intellectual Property Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.J.; Wu, N.J. Research on the measurement, decomposition and influencing factors of Green Economic Efficiency in the Yangtze River Economic Belt: Based on Super-Efficiency SBM-ML-Tobit Model. Urban Probl. 2021, 1, 52–62+89. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, G.Y.; Zhang, J.P. The Estimation of China’s provincial capital stock: 1952–2000. Econ. Res. J. 2004, 10, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.S.; Niu, Y.; Peng, J.; Wang, Z.; Huang, X.L. Research on energy consumption dynamic among prefecture-level cities in China based on DMSP/OLS Nighttime Light. Geogr. Res. 2014, 33, 625–634. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, W.; Hu, Y. Internet Development, Consumption Upgrading and Carbon Emissions—An Empirical Study from China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, P.; Liu, M.; Su, L.; Fei, Y.; Tan-Soo, J.S. Electricity consumption in the digital era: Micro evidence from Chinese households. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 182, 106297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hao, F. Does Internet penetration encourage sustainable consumption? A cross-national analysis. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2018, 16, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Mao, S.; Lv, S.; Fang, Z. A Study on the Non-Linear Impact of Digital Technology Innovation on Carbon Emissions in the Transportation Industry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghion, P.; Antonin, C.; Bunel, S. The Power of Creative Destruction: Economic Upheaval and the Wealth of Nations; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Akcigit, U.; Caicedo, S.; Miguelez, E.; Stantcheva, S.; Sterzi, V. Dancing with the Stars: Innovation Through Interactions; Working Paper 24466; National Bureau of Economic Research: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Wang, L.; Shen, Y. Can digital technology reduce carbon emissions? Evidence from Chinese cities. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1205634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.Y.; Qi, J.; Xian, Q.; Chen, J.D. The Carbon Emission Reduction Effect of China’s Carbon Market—From the Perspective of the Coordination between Market Mechanism and Administrative Intervention. Chin. Ind. Econ. 2021, 8, 114–132. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, H.D.; Fang, S.H.; Jiang, D.C. Market Performance in Digital Transformation: Can Digital M&As Enhance Manufacturing Firm’s Market Power? J. Quant. Tech. Econ. 2022, 39, 90–110. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.H.; Yang, L.; Jiang, S.S. Binding Carbon Reduction Policy and Employment: Based on the Investigation of Labor Force Changes in Enterprises and Regions. Econ. Res. J. 2023, 58, 104–120. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.H.; Lu, Z.J. Green Bond Issuance and Corporate Value Promotion—The Mediation Effect Test of PSM-DID Model. J. Huainan Norm. Univ. 2024, 26, 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.; Li, H. Low-Carbon City Pilot Policy, Digitalization and Corporate Environmental and Social Responsibility Information Disclosure. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Hu, J. Does China’s Low-Carbon City Pilot Facilitate Firm Productivity? An Analysis of Industrial Firms. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.