Abstract

This article critically examines the conceptual boundaries and applications of the terms biocultural and ecocultural in interdisciplinary research addressing biodiversity threats in rural communities. The aim is to clarify their meanings and propose recommendations for their use in sustainability science. We conducted an integrative conceptual review combining a narrative literature analysis and corpus linguistics methods on 54 documents across four disciplinary areas: Ecology and Biodiversity Conservation, Economics and Heritage, Ecocriticism and Literature, and Sociocultural Discourses. The narrative synthesis explores theoretical interpretations, while the corpus analysis quantifies term frequency and collocations to identify patterns of use. The results reveal that biocultural perspectives emphasise species-focused interactions, traditional knowledge, rights, ecoethics, and governance, whereas ecocultural approaches foreground discourse, communication, identity, education, and long-term ecological processes. Both frameworks converge in their concern for sustainability and cultural–ecological interdependence but differ in scope and temporal depth. This study contributes scientifically by offering a situated, interdisciplinary analysis of these concepts, and socially by underscoring the need for dialogical frameworks that respect local knowledge and expand applications beyond rural contexts to urban, educational, and policy domains. Recommendations are provided to guide interdisciplinary teams in adopting context-specific conceptualizations for research and action.

1. Introduction

The challenges posed by the current scenario of climate change has called upon all scientific efforts to propose strategies and actions that promote the sustainable development of communities [1]. The dramatic and accelerated loss of biodiversity, decline in water resources, and shifts in species distribution, to name a few, has had profound and unfathomed not only ecological but also social repercussions, especially in rural communities [2]. With regard to the latter, the risks of the extinction of local species and varieties may have a significant impact on the lifestyle of rural communities, as they may cause the loss of traditional practices, cultural understandings, and local identities of these communities. The climate crisis then leads to a cultural crisis, since the biodiversity, ecosystem, and health of the environment are inextrinsically interconnected with the cultural development of communities [3,4,5].

The search for solutions to this global crisis partly led in 1988 to the Declaration of Belém [6], encouraging critical debates on the urgent decline in biological and cultural diversity. This debate acknowledges humanity’s dependence on natural resources and ecosystem services [7], and highlights the need to preserve global biodiversity (which includes genetic assets and the knowledge associated with their management) and the essential interconnections among all forms of life [8]. In this light, sustainability can be better attained if the climatic crisis is approached from a multidisciplinary perspective.

It is with this mission that a multidisciplinary team of researchers was gathered, guided by the objectives of the Anillos Project (ANID ATE230028), entitled “Biodiversity from Coast to Mountains: A socio-environmental study of rural communities’ (Eco)2-Cultural practices in a scenario of Climate Change”, to evaluate and address the threats of biodiversity changes in rural communities in Chile from an interdisciplinary perspective. Researchers from biological sciences, agronomy, ecology, literature, economics, and linguistics nurture such interdisciplinary views. One of the first challenges faced by the team was to agree on the meaning and use of terminology pertaining the study. In particular, as the team began to refine its theoretical framework in order to design its data collection instruments and activities, it became more and more evident that the conceptual boundaries of the terms biocultural and ecocultural were unclear. Yet most literature on the subject emphasises that both the biocultural and ecocultural approach taken together represent a promising paradigm for addressing environmental challenges [9,10]. Thus, the conceptualization of the biocultural and ecocultural frameworks is key to highlighting the intricate interaction between human societies and their ecosystems, emphasising the importance of preserving cultural practices intertwined with ecological systems [11], amidst the urgent challenges posed by global environmental change [12].

The lack of clarity in the distinction between the two terms has often led to them being used as synonyms in studies of the human–nature relationship. Both concepts are present in the literature to contextualise the understanding of the relationship between humans and nature through a cultural perspective that integrates various disciplinary fields within the sciences. However, the specificities related to each of the terms often seem to escape academic debate and, thus, the overlapping and often inconsistent use of the terms across disciplines naturally hinders theoretical clarity, interdisciplinary collaboration [13], and the development of indicators for empirical research and policy-making [14].

Having said this, several authors have undertaken efforts to clarify the meaning, uses, and scope of the terms biocultural and ecocultural, contributing valuable insights to the ongoing conceptual debate. For instance, Otamendi-Urroz et al. [14] examine the role of “biocultural diversity” in conservation and sustainability by reviewing the literature between 1990 and 2021 and zooming into its intangible components to offer perspectives often overlooked. Franco [13] clarifies that the term “biocultural” has been used in anthropology long before “biocultural diversity” was discussed in the biological sciences, and explains that in anthropology “biocultural” traditionally refers to the integration of biological and cultural data to understand human health and adaptation, emphasising the influence of social and environmental factors on human biology. In contrast, biocultural diversity studies focus on the interrelationship between biological, cultural, and linguistic diversity within socio-ecological systems, often with a conservation-oriented lens. Thus, Franco [13] proposes to use the term “ecocultural” as an alternative to “biocultural” to better reflect the reciprocal and dynamic relationship between culture and ecology, particularly in cultural studies and sustainability science. However, “ecocultural” itself is not free from ambiguity, as it is variably interpreted across disciplines, and rarely reflected upon with regard to its meaning and scope.

Despite these efforts to provide a clearer description of the terms, the literature has not yet reached its potential depth of critical scrutiny within the scientific community as studies have often focused their conceptual analysis on only one of these terms (e.g., biocultural [8,15,16]) or collocations of terms (e.g., “biocultural diversity” in [14]), and they have approached these concepts from a disciplinary perspective that is limited either in scope or in the number of disciplines considered (e.g., biology and anthropology [13]). Last but not least, while the term “biocultural” has been discussed quite extensively in the literature, the concept “ecocultural” has received comparatively less attention [13] and comparisons between the two terms are scarce.

In this light, the present study hopes to advance scholarly discussion that contributes to the conceptual evolution of the terms biocultural and ecocultural by building on influential contributions in the field (such as Franco’s [13] work) and by analysing both concepts across multiple disciplines to thereby foster theoretical clarification, and provide an integrative understanding within modern interdisciplinary frameworks. To this end, this article aims to clarify the meanings of the terms bio- and ecocultural, and to propose recommendations for their use in interdisciplinary studies by providing a critical and contextually situated conceptual review of the literature through analysing their scope, uses, and meanings in the four disciplines encompassed in the Anillos ANID ATE230028 project. This article contributes to existing efforts to provide contextual clarity on the use and understanding of the terms biocultural and ecocultural by (1) taking a broad perspective on the exploration of the terms as used in the disciplines included in this study; (2) considering a multiplicity and array of disciplines that, to our knowledge, have not been reviewed before; (3) proposing complementing analytical frameworks (namely, narrative literature review and linguistic corpus analysis) to broaden the scope of interpretation; (4) articulating these views from an interdisciplinary perspective. To conclude, this study identifies areas of potential interdisciplinary debate and interest for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

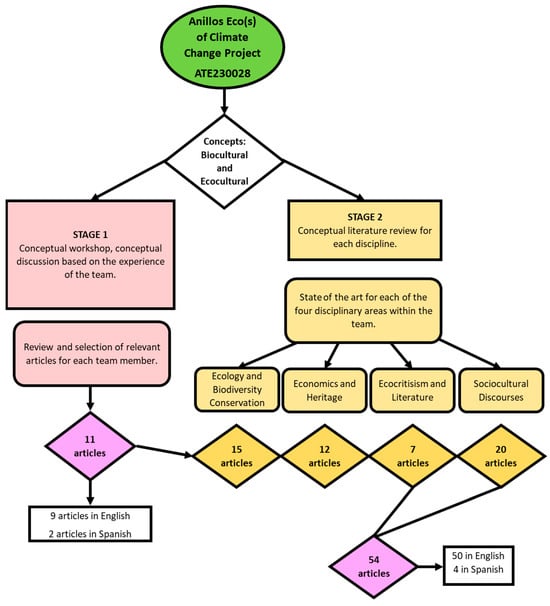

In order to analyse the scope and meanings of biocultural and ecocultural from an interdisciplinary perspective, this article presents a conceptual review of the literature, following the guidelines of conceptual analysis and integrative review in [17] and Lilford et al. [18]. This type of review is broad and rigorous, and often helps to reconceptualise theory, note inconsistencies and tensions, and find gaps in the literature, all of which contributes to the advancement of scientific knowledge [19]. Unlike traditional systematic reviews, a conceptual review does not aim to exhaustively cover all the existing literature, but rather to explore a broad range of sources and databases (such as WoS, Scopus, Latindex, Google Scholar) [18]. Moreover, the fact that this review was carried out by an interdisciplinary team of nine researchers minimises the potential biases of reviews [20]. The integrative conceptual literature review was conducted in two stages, which can be seen in Figure 1. It is worth noting that all nine researchers participated in both stages of this integrative conceptual literature review, as well as in the drafting of this paper.

Figure 1.

Conceptual literature review process on the biocultural and ecocultural concepts.

Stage 1. An interdisciplinary review workshop was designed for the project’s team, which consisted of nine members, four men and five women. Prior to the workshop, a team discussion was carried out in order to identify the need to clarify the use and meaning of the concepts biocultural and ecocultural. Based on the results of the discussion, each of the nine researchers was asked to select between one and three articles they considered relevant for understanding and defining these concepts. Each team member made their selection individually and independently, without knowledge of others’ choices. This approach allowed for an unbiased assessment of thematic or content overlap among the selected articles. The workshop coordinators collected the proposed articles chosen by the members of the team, resulting in a total of 11 articles, 9 in English [5,10,11,13,16,21,22,23,24] and 2 in Spanish [4,25]. Among them, only one article [13] was selected by five researchers, granting it a central role in the conceptual discussion. During the workshop, the team was divided into three groups where they discussed the articles they had chosen in order to answer the following questions: (1) What is the ecocultural?, (2) What is the biocultural?, (3) What are the differences and similarities between these concepts?, (4) Is there a more relevant concept for the Anillos project, or is it appropriate to use both concepts in scientific writing and dissemination? The answers were written by each group on wallpaper and later presented and discussed with the whole team. After a long discussion, the team noted the inconsistencies in the use of both terms and the role of the disciplinary understandings in informing the interpretations of these concepts. Thus, based on these reflections, we identified the disciplinary groups present in the project to define more specific areas of analysis of the concepts and designed the integrative conceptual review for Stage 2.

Stage 2. The research team was divided into groups representing four disciplinary areas according to their academic expertise: Ecology and Biodiversity Conservation (4 researchers), Economics and Heritage (2 researchers), Ecocriticism and Literature (2 researchers), and Sociocultural Discourses (1 researcher). Each disciplinary group conducted an independent search and selection of the literature regarding the use of the biocultural and ecocultural concepts within their respective fields of expertise. There was no limit of years for this search and each disciplinary group agreed on their search keys (see Section 3). The searches were conducted in databases such as WoS, Scopus, Scielo, and Latindex, as well as in Google Scholar to search for articles not included on the databases. Articles were considered eligible for inclusion in this study if they met at least one of the following two criteria: (A) described the meaning of biocultural and/or ecocultural, and provided a sound theoretical background to do so; (B) were related to the topic of study of the Anillos project in at least one of its components (threats posed by climate change to rural communities in terms of the surrounding biodiversity, and the loss of traditional knowledge, practices, and identities). This process resulted in a total of 54 documents, 50 of which were in English and 4 in Spanish.

After selecting the corpus of scientific literature, the data analysis was also conducted in two phases. In the first phase, the documents were examined according to their disciplinary areas employing techniques of a narrative literature review analysis [26], which provides a general understanding of how both concepts are used and interpreted in each disciplinary group. The narrative literature analysis process is iterative, non-structured, and multi-layered. It contains several cumulative written outcomes and is viewed as embedded in a social context in which the concepts are investigated. Grounded in the humanities and social sciences, it provides a comprehensive narrative (that is, descriptive) synthesis of previously published information [27]. In the second analytical phase, a corpus linguistics analysis was conducted using MAXQDA 24 software (Germany) to determine the frequency of occurrence of these concepts and their collocations. As Thompson and Hunston [28] explain, corpus linguistics can significantly enrich interdisciplinary studies by providing empirical insights into language use across diverse disciplinary contexts. Moreover, corpus methods offer quantitative support for qualitative interpretations, fostering collaboration between disciplines that value both scientific rigour and contextual depth. This approach enhances the credibility of interdisciplinary research [29]. Thus, analysing the frequency of occurrence and collocations of both concepts allowed us to analyse linguistic patters that show the kind and degree of scientific interest involving the study of biocultural and ecocultural aspects, and their scope and applications, that is, the contexts in which these concepts have been investigated, the way these concepts have been applied to investigate biodiversity and/or sociocultural changes, and so on. Finally, the findings of each term were then compared across disciplinary areas to enrich the interpretation of the findings.

3. Results and Discussion

The results have been organised into four sections, which correspond to the four disciplinary areas defined in this study, namely, (1) Ecology and Biodiversity Conservation, (2) Economics and Heritage, (3) Ecocriticism and Literature, (4) Sociocultural Discourses. In turn, each section first presents a comprehensive narrative synthesis of the articles analysed for that disciplinary area, followed by a corpus linguistics analysis of the use, frequency of occurrence, and collocations of the terms biocultural and ecocultural.

Table 1, below, shows the main indicators considered in the corpus by disciplinary area, including the number of documents and the number of words analysed.

Table 1.

Total number of documents and words per disciplinary area.

Table 2 shows the articles analysed for each disciplinary area.

Table 2.

References of documents analysed per disciplinary area.

3.1. Ecology and Biodiversity Conservation

Within this disciplinary area, biocultural and ecocultural are modern concepts that have emerged to describe the complex relationship between human societies and their natural environments [13] (to distinguish between the literature used to contextualise the narrative analysis from the studies reviewed as part of the actual analysis of the paper, we include the latter references in bold in the text). Broadly speaking, both concepts are considered essential for understanding the cultural manifestations that arise from the interaction between humans and the ecosystems in which they live [11]. Thus, both concepts emphasise the interconnection between cultural practices and species/ecosystems (including both biotic and abiotic components), highlighting the importance of integrating efforts to conserve this interaction. However, it is important to underscore certain differences between the two, as revealed in the analysed scientific articles.

In a world where an increasing number of people are projected to live in cities, and where there is a growing trend for urban populations to become disconnected from the biosphere [30], the demand and pressure of these populations on natural resources and the biosphere have become increasingly stronger. In this regard, the FAO [74] identifies key global challenges for the coming decades, including (1) a sustainable increase in agricultural production to meet the current growing demand, (2) ensuring the sustainable use of natural resources, (3) addressing climate change challenges, (4) improving opportunities, life quality, and income in rural communities, among others. Within this context, the concept biocultural emerges in the reviewed studies as a way to address these challenges predominantly linked to the study of interactions between biodiversity and human cultural practices, with an emphasis on the traditional knowledge expressed through cultural manifestations that reflect the communities’ relationship with their natural environment. In this light, biocultural is defined as the interconnection between biological and cultural diversity with a focus on traditional practices, local knowledge, and heritage related mainly to species. Thus, this research emphasises the interdependence between biological and cultural diversity, and focuses on the role played by local communities in conserving [16] species and landscapes [4,11,31,32,33].

These interactions have been particularly identified and investigated in rural and/or indigenous communities, where livelihoods are closely dependent on biodiversity [32,33], showing how biocultural practices are threatened by climate change, which, by disrupting their surrounding biodiversity, endangers the rural and ancestral cultural traditions of communities that have historically depended on specific species for their daily lives and cultural identity [10,11,23,31,32,33]. Some examples of such applied practices include agrobiodiversity conservation through seed exchange and crop rotation in rural communities [32,33], biocultural conservation systems in Mediterranean landscapes [23], and the ecocultural restoration of temperate forests through traditional ecological knowledge and silvicultural practices [31]. The analysed studies highlight the struggles of rural communities to preserve traditional knowledge in order to sustainably manage ecosystems through a range of cultural practices that enable them to develop suitable responses for their ecological challenges and environments [10,11,23,25,31,32] and [75].

On the other hand, the ecocultural approach can be considered a much broader concept in these studies. In this review, we recorded the ecocultural perspective as a concept that connects cultural practices derived from the interaction between human populations and ecological processes, which directly shape the types and characteristics of cultural expressions. Hence, these interactions correspond to ecological processes that directly influence, for example, the formation of identities and cultural routines unique to each community [10,11,13,34,36]. Moreover, the concept of ecoculture incorporates the idea that ecocultural practices are not only the result of direct interactions with biodiversity (as in the case of the biocultural approach), but also integrate abiotic elements (such as climate and geography) that are part of the ecological processes that shape cultural responses to environmental challenges. In addition, the ecocultural approach also includes social (e.g., social roles within a community), political, and even economic [37] factors as key forging forces of these practices [13,34,35]. A particularly central concern in the reviewed studies relates to the research of strategies and actions towards the protection of the ecocultural heritage of rural communities [31]. This is not only because they serve as ecocultural expressions but also because they represent potential solutions to enhance ecosystem and communities’ resilience through sustainable practices [11,13,31,35].

Within the context of Ecology and Biodiversity Conservation, we can then observe that both biocultural and ecocultural approaches allow for the recognition of the value of traditional knowledge and cultural practices in rural communities. Hence, although both concepts may overlap in the way they look at how humans and environments co-shape the development of cultural practices, knowledge, and heritage, they also differ in scope, as biocultural is a term that has a narrower focus: it zooms into the interconnection between biological and cultural diversity with an emphasis on traditional/local practices, local knowledge, species, and rural/indigenous communities. On the other hand, we found that the term ecocultural encompasses a broader scope, referring to cultural expressions shaped by long-term ecological processes. These are closely linked to abiotic factors such as climate and geography, while also integrating social, political, and economic dimensions. Ecocultural expressions are often deeply rooted in local identity and, in some cases, framed as complementary to—or overlapping with—the biocultural concept [31].

To illustrate the use of the biocultural and ecocultural concepts, Figure 2 below presents the frequency with which the terms appear in the reviewed articles within the field of Ecology and Biodiversity Conservation.

Figure 2.

Ecocultural and biocultural word mentions in articles in the field of Ecology and Biodiversity Conservation [4,10,11,13,16,23,25,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37].

Figure 2 shows that the concept biocultural is mentioned in 13 out of the 15 documents reviewed in this disciplinary area, with a total of 1119 occurrences of the term. Among these 13 articles, the study by Bridgewater and Rotherham [16] stands out with a word frequency of 608 occurrences for this concept, followed by Franco [13] with 202 occurrences of the term, and Merçon et al. [10] with 103. In the case of the concept ecocultural, it is mentioned in 6 of the 15 analysed documents, with notable contributions from the studies by Tarin et al. [35] with 38 mentions, by Oriel and Frohoff [34], which has a word frequency of 28 mentions, followed by Franco [13] with 28 mentions, and Martínez [31] with only 12 mentions. In this regard, Figure 2 shows that the presence of the concept biocultural is much greater than that of ecocultural, both in the number of documents that use each term and in the word frequency with which these terms are referenced within the selected articles.

In this regard, to understand the meaning that scholars attribute to both concepts when using them, we need to explore the words that precede and/or follow both concepts (that is, that collocate with both terms) and contextualise them in the studies analysed in the area of Ecology and Biodiversity Conservation, as shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4 below.

Figure 3.

Frequency of collocations of biocultural in the disciplinary area of Ecology and Biodiversity Conservation.

Figure 4.

Frequency of collocations of ecocultural in the disciplinary area of Ecology and Biodiversity Conservation.

Figure 3 and Figure 4 show the word frequency of the concept biocultural, with a total of 1119 mentions, appearing alongside the concept of diversity, which has 155 mentions in the 15 analysed documents. Additionally, there are 26 mentions of diversidad biocultural (biocultural diversity) in the documents written in Spanish. The word studies collocates with biocultural 50 times, approaches 40 times, systems 30 times, paradigm 27 times, conservation 22 times, heritage 20 times, and status 18 times. In this sense, the use of biocultural appears predominantly linked to three key semantic axes. The first one is characterised by the disciplinary context, which emphasises the broad range of species, relationships, and practices that may be involved in the subject of study, represented by the frequent use of the term diversity. The second axis relates to the ways in which a given research problem is approached and conceptualised, as reflected in collocates such as studies, approaches, systems, and status. A third axis focuses on the understanding of biocultural as an element that persists over time through “human intention”, and is regarded as a heritage or patrimony that calls for efforts and actions to be preserved for the future.

On the other hand, the concept ecocultural (and its related concepts, such as ecoculture, ecoculturalism) has a lower frequency overall in the analysed documents, with a total of 134 mentions. Among these, the terms identity with 56 mentions (which shows a clear research interest), and restauration with 9 mentions are the most frequently used collocates. Regarding the notion ecocultural identity, it is also associated with concepts such as dialogic (four mentions), monologic (three mentions), and interspecies (three mentions). These three notions highlight the communicative nature attributed to identity processes associated with the concept ecocultural and the potential interconnections among species involved in identity processes as an integral part of ecocultural processes. Regarding the concept of ecocultural restoration, it can be associated with the concept of revitalization (three mentions), as both involve attempts to restore ecological elements that are part of the main topic of the articles analysed.

Finally, it is worth noticing that (with the exception of the collocate diversity as noted above) the word systems is the only term associated with both biocultural and ecocultural concepts (30 and 3 mentions, respectively), making it a key conceptually converging point regarding the meanings attributed to this dyad in the reviewed research. Conceptualising them as “systems” implies recognising that both biocultural and ecocultural concepts encompass a set of interconnected elements. Thus, the biocultural and ecocultural frameworks share a foundational understanding of interconnectedness, which points in the direction of an acknowledged need (or preference) to employ a rather holistic approach to the study of human–nature interrelations. This conceptualization—though still incipient (given the low number of occurrences in these articles)—constitutes a way forward to achieving a much richer and multi-layered understanding of human–nature interconnections. Yet, it should be noted that, staying true to its disciplinary roots, conceptualising bio- and ecocultures as systems underpins an underlying view of human–nature components as a collection of elements that function as a whole. This perspective suggests a stronger focus on components and structures than in the interacting activities involving these components. And, though it acknowledges that human and biological (both biotic and abiotic components) are integral parts of a whole, this approach may be considered rather more static than a bio- and ecocultural process approach.

3.2. Economics and Heritage

Economics studies how individuals, businesses, states, and other societal agents choose to use and distribute productive resources, which are, in most cases, limited. These choices involve trade-offs between alternative uses of resources and respond to certain incentives, that is, the advantages or disadvantages of selecting among such alternatives. In economics, resources are those goods, services, and assets available that individuals and societies use to produce goods and services that meet people’s needs. These resources are commonly classified into three categories: natural resources (e.g., land, water, and minerals), human resources (human labour and ingenuity, peoples’ skills and abilities that contribute to production), and capital resources (such as machinery, buildings, and infrastructure) [76].

The origins of the concept biocultural as an approach to the study and conservation of biodiversity can be traced back to the Declaration of Belém [6], which recognises the existence of an inextricable link between cultural and biological diversity [5] and [13]. This declaration provides the guidelines for research on how indigenous and rural communities (as guardians of biodiversity) perceive, manage, and use their natural resources. It also proposes principles for preserving both biological and cultural diversity. From the Declaration of Belém, several highly relevant economic issues have emerged that inform biocultural studies in the field of economics. First, biodiversity, along with the traditional knowledge of indigenous and rural communities, is conceived as a resource whose use and management underpins the well-being of these communities [40]. Second, these resources are becoming increasingly scarce or disappearing altogether. And third, it is assumed that indigenous communities have a right to own the resources they manage; hence they must be granted the right to decide the fate of these resources [46]. These views on biodiversity and its management differ significantly from the perspectives of biological conservation discussed in the previous section.

In light of the dramatic loss of cultural and biological diversity, the Declaration of Belém proposes eight core actions for conservation, three of which have an economic focus: (1) allocating the majority of development aid to research on inventories, conservation, and management programmes; (2) establishing compensation mechanisms for the use of indigenous knowledge and resources; (3) promoting the exchange of information on the sustainable use of resources. Although the goal of the Declaration of Belém was to promote actions for research and the conservation of biological and cultural diversity, the biocultural perspective, which emerged under its influence, led to a scientific debate dominated by conceptual challenges for two decades [38].

Following this period of debate, between 2018 and 2021, the discussion shifted towards defining operational principles for research and political action, the latter reinforced by the Belém +30 Declaration [77], which (1) added a new economic action to foster production, access funding (through credits), and market social- and biodiversity-related products, including access to training and technologies, (2) encouraged social mobilisation to demand that states and international organisations comply with agreements on indigenous and environmental rights [5]. As a result of the second recommendation, research on biocultural perspectives has shifted towards a focus on movements for human rights and social justice at the expense of overlooking conceptual or operational discussions related to economic principles that would have made the recommendations of the Belém Declarations more actionable.

The Convention on Biological Diversity [78], the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples [79], the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture [80], and the Declaration on the Rights of Peasants [81], among other international agreements, recognise that the use of knowledge and biological diversity managed by local, peasant and indigenous communities, and by third parties can generate economic benefits. These benefits include, for instance, patents derived from varieties developed from local crops and innovative practices for biodiversity conservation, among others. These international agreements recommend sharing and/or compensating these communities for the benefits derived from the use of their knowledge, genetic resources, and practices. This issue has sparked a broad debate in the field regarding the limitations of intellectual property laws in protecting the collective knowledge of local communities, as well as the most appropriate mechanisms for sharing the economic benefits derived from their biocultural assets, that is, their biodiversity and knowledge [43,44].

Graddy’s work [45] on the conservation of cultivated diversity (or agrobiodiversity) by indigenous communities in the Peruvian Andes demonstrates that in situ conservation is only effective when policies protect the communities’ ways of life, worldviews (cosmovision), and autonomy over their genetic resources. However, the implementation of protection systems such as the Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS) established by the FAO fails to achieve its conservation goals, as agriculture is not recognised as an economic activity that sustains families’ livelihoods. For this reason, studies in the field of biocultural diversity continue to investigate ways in which to protect GIAHS by mobilising government support and raising awareness among producers.

In the context of these debates and struggles, studies exploring human–biological interactions from an interdisciplinary perspective propose approaching biocultural diversity from an historical perspective that accounts for other social, economic, and political factors that may have affected the location and numbers of human populations and their relationships with and effects on the environment [39]. In the articles reviewed for this section, the concept of biocultural diversity has been associated with a wide range of descriptors, some of which are closely related to economic and territorial issues, such as biocultural landscape, collective biocultural heritage, and indigenous biocultural knowledge. According to this literature, biocultural landscape is understood as a concept that integrates economic, social, cultural, and environmental processes across time and space [40]. Furthermore, collective biocultural heritage refers to knowledge, innovations and practices, territories, crop varieties, species, and ecosystems that relate to local economies, as well as values, norms, and customs developed within the socio-ecological context of communities that help them develop and become sustainable [41]. From an economic perspective, collective biocultural heritage is regarded as part of a community’s natural, economic, and social capital, which is passed down through generations. Within this context, the control and management of these resources by local communities is essential to ensuring the sustainability of their cultures and biodiversity [42].

Moreover, the three studies analysed for this section that have a focus on ecoculture investigate indigenous knowledge, beliefs of equal respect for all ecosystem components, and traditional practices that help sustain resource productivity (that is, that help create and maintain diverse and productive ecosystems) in an effort to propose successful restoration strategies [46,47,48]. Thus, the ecocultural approach has been used to show the reciprocal and inseparable link between ecology and culture, and considers how the environment in which people live influences their cultural development (and vice versa), while both (environment and culture) shape individuals’ identities, sense of belonging, and ability to adapt to change [13].

Ecoculture has also been used as a noun to describe the cultures of certain people’s ecocultures, as the three articles centre their inquiry on the experiences of indigenous communities, which exhibit a set of ethical principles reflected in conservationist behaviours toward their natural and social capital. In these cultures, well-being not only encompasses broad dimensions of the physical and affective aspects of life, but it is also considered through an economic lens [46]. In this light, the ecocultural approach has also been applied in ecological restoration processes, such as the reintroduction of the American bison in Banff National Park, Canada, in which scientists collaborated with indigenous communities to restore the cultural roles of the bison, including ceremonies, storytelling, and bison hunting for food and economic benefits [47]. Notably, reviving bison hunting within these communities helped integrate the endangered animal back into indigenous life, which in turn contributed to the species’ population recovery within the reserve. Similarly, Wickham et al. [48] draw on examples of contemporary restoration projects of crabapple orchards and clam gardens to propose a place-based values approach for the recovery of ecocultural landscapes that is congruent with ethics on the inclusion of indigenous communities when efforts are made to learn from them and to preserve their ecocultural heritage [48]. As a result of both studies [47,48], progress was made in the ecocultural restoration of the territory, which, as stated by the authors of the articles, highlights the importance of considering the economic use that communities make of the species and ecosystems targeted for conservation.

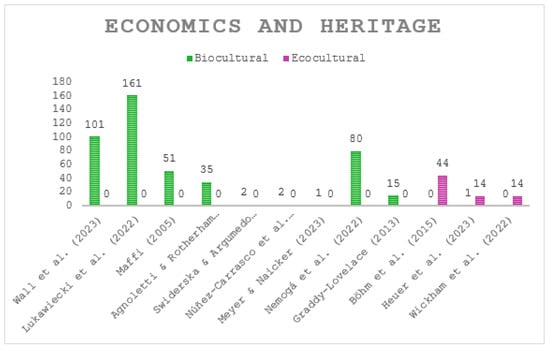

With regard to the linguistic analysis conducted on the 12 selected articles reviewed for the disciplinary area of Economics and Heritage, Figure 5 shows the uses, frequencies, and collocations of the terms biocultural and ecocultural.

Figure 5.

Ecocultural and biocultural word mentions in articles in the disciplinary area of Economics and Heritage [5,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48].

Figure 5 shows that the term biocultural is mentioned 449 times in 10 of the 12 articles reviewed in this area. Among these 10 articles, the research by Lukawiecki et al. [38] stands out with 161 mentions of the term, followed by Wall et al. [5] with 101, Nemogá et al. [44] with 80, Maffi [39] with 51, Agnoletti and Rotherham [40] with 35, and Graddy and Lovelace [45] with 15 mentions. Regarding the concept of ecocultural, it is mentioned in only 3 of the 12 documents analysed where Böhm et al. [46] with 44 mentions concentrates the largest number of occurrences of the term, followed by Heuer et al. [47] and Wickham et al. [48] with 14 mentions each. Thus, Figure 5 highlights that, in the disciplinary area of Economics and Heritage, the presence of the concept biocultural surpasses ecocultural, both in terms of the number of documents using it and of frequency of mentions.

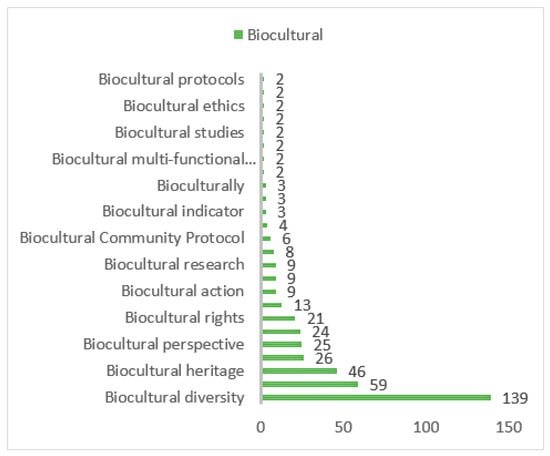

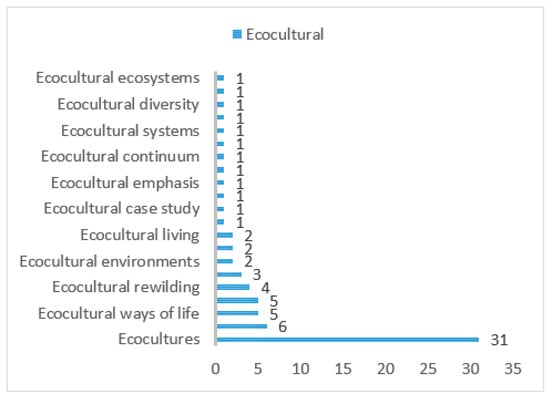

Regarding the collocations of both terms, Figure 6 and Figure 7 allows for the analysis of the conceptual connections established within the research area, which helps to characterise the specific meanings attributed to each concept in the disciplinary area of Economics and Heritage.

Figure 6.

Frequency of collocations of the term biocultural in the disciplinary area of Economics and Heritage.

Figure 7.

Frequency of collocations of the term ecocultural in the disciplinary area of Economics and Heritage.

Figure 6 shows that the term biocultural is associated with concepts such as diversity (with 139 mentions in the 12 documents analysed), followed by heritage (with 46 mentions), approach (26), perspective (25), theory (24), rights (21), and context with 13 mentions. Thus, the use of biocultural is also primarily associated with the same three axes identified in the previously analysed disciplinary area of Ecology and Biodiversity Conservation, but with a stronger focus on how these views or factors advance the economic development of communities. The first axis is related to the recognition of biological, cultural, and social diversity, linked to the notions of economics and culture attributing value to the components of biocultural diversity, based on human perspectives regarding the relational dimension with the species that constitutes the biocultural fabric (e.g., [48]). The second axis focuses on the intergenerational transmission of natural, economic, and social capital that defines the biocultural concept from the perspective of “human needs satisfaction” [46,47]. Thus, when the term heritage is used in this disciplinary context, it often refers not only to the natural heritage, but also to what humans have built from it that is passed down from generation to generation, and that can potentially favour their economic development. This underscores the need to safeguard biocultural diversity, along with the associated practices, knowledge systems, and relational networks that persist across time and space. Such efforts have brought attention to the vulnerability of specific biocultural elements, increasingly framed through the lenses of the rights of, for instance, indigenous people and the contextual significance of communities’ relationship with their surrounding biocultural diversity. In this way, the idea of positioning oneself in relation to a given biocultural context is introduced as a situated activity, which depends on the communities’ social and historical relationship with nature (and thus the way they occupy a place amidst diversity that suits their needs and expectations), without losing sight of the fact that very often the research focus is on the productive aspects of this relationship.

Finally, the third axis refers to ways of addressing and understanding a specific research problem through the use of terms such as approaches, perspective, and theory. The latter two concepts introduce a conceptual shift from the disciplinary field of Ecology and Biodiversity Conservation, replacing the focus on systems and status. This choice of terms reflects the lens through which biocultural and ecocultural phenomena is viewed in this field, where an approach seems to imply a higher commitment to offer solutions, a perspective is just a way of seeing the issue at hand, and theory displays an academic interest for conceptually developing the topic.

On the other hand, the concept ecocultural appears to be less frequently used in the analysed documents, with a total of 72 mentions, out of which the term ecocultures is mentioned 31 times (Figure 7). Only a few collocations, such as approach (six mentions), landscape (five mentions), ways (five mentions), and rewilding (four mentions), stand out with a higher frequency of occurrences. In this regard, the collocations for ecocultural, such as approach and ways, reflect research efforts towards understanding practices, knowledge, and experiences related to specific issues concerning the relationship between humans and their environment. Likewise, the notion of ecocultural landscape highlights the link between space and time in understanding human–nature relationships as complex systems. Additionally, the term rewilding, also associated with restoration (one mention), presents an ecocultural vision as an intentional effort to restore or revitalise an ecological system that requires human support and action. Finally, it is worth highlighting the experiential perspective adopted in most of these studies where the concept ecocultural collocates with lives (five mentions) and living (two mentions). These relate to deep and everyday processes within communities, strongly rooted in practices beyond theoretical conceptualisations, which support connections to resilience, resistance, and the reinterpretation of the challenges associated with, for instance, climate change.

Finally, it is worth noticing that two concepts appear to be associated with both biocultural and ecocultural: approach and landscapes. These concepts indicate a convergence in the conceptual frameworks through which both terms are understood and employed. Viewing biocultural and ecocultural concepts as approaches rather than perspectives, for example, emphasises an intention to propose actionable, integrated strategies for addressing complex socio-ecological challenges by actively integrating biological, cultural, and environmental data and practices, rather than projecting a passive awareness of their interconnectedness. This active framing promotes the development of locally relevant conservation and management initiatives by highlighting the interconnected nature of environmental and social systems through time and space (see the analysis of landscape use above). Viewing them as an approach also emphasises the situated nature of these scholarly inquiries as matters are studied within the contexts of the communities where solutions are intended to be applied.

3.3. Ecocriticism and Literature

The academic intersection between literature and ecology is known as ecocriticism and includes seminal texts such as “The Ecocriticism Reader” by Glotfelty and Fromm [82], and “Ecocriticism” by Garrard [83]. However, these works do not include either the term bioculture or ecoculture, despite the fact that the former compiles essays that are considered the precursors of ecocriticism, while the latter provides an extensive reflection on how white North Americans and British have represented their relationship with the natural environment in the literature, considering nature as a fundamental physical space rather than just a simple background setting. In 2016, in “Keywords for Environmental Studies”, Rocheleau and Nirmal [84] recall that, from the perspective of cultural studies in the 1970s, the nature–culture dichotomy was laden with dualism, hierarchy, and a lack of reciprocity. From this standpoint, culture was seen as separate from nature, until a scholarly shift took place and, as the anthropologist Andrea Staid [85] asserts, “the crisis of this dichotomous model has led us to a new and fruitful dialogue between what were once considered natural sciences and social sciences” (p. 23). Rocheleau and Nirmal [84] then explain how this dichotomy has been de-constructed, first through ecofeminist, poststructuralist, and science and technology studies; second through the convergence of social movements, social theories, and natural sciences focused on complex systems, networks, and relational theories; and finally, through decolonial thought.

In the case of Latin America, ecocritical literary studies have incorporated, from the early 2000s, terms closely related to the concepts of biocultural and ecocultural to refer to the ecocritical as well as methodological approaches that serve as alternatives to Anglo-American ecocriticism. In “Notas sobre ecocrítica y poesía chilena” (in English, “Notes on ecocriticism and Chilean poetry”), one of the first ecocritical studies published in Chile, Ostria [86] proposes the term bio-socio-cultural complex to describe a concept that “allows for the integration of the mythical and sacred external world of nature with subjectivity and the social world” (p. 182). This, in turn, guides the understanding of the literature and other forms of human imagination as a “testimony that human beings and their natural and social environments constitute a complex and an inseparable unity” (p. 189), and that the role of ecocriticism is precisely to mediate between “authors, their texts, the biosphere, and the reader” (p. 183).

Drawing on these ideas, the book “The Latin American Ecocultural Reader” [50] highlights the ecocultural perspective as an expansion of the epistemic limitations of ecocriticism. This perspective reveals the continuities and ruptures of the “Latin American environmental thought” in relation to political and economic structures as well as ecosystems. Similarly, Herring [49] supports the idea that the ecocultural perspective is the most appropriate way for “analysing and describing Latin American reality concerning ecological, social, cultural, and economic aspects” (p. 6), as it connects human and non-human spheres by focusing on their interaction rather than their opposition. These works were highly influenced by the pioneering contribution of the Canadian researcher Adrian Ivakhiv [51], who defines ecocultural critical theory and ecocultural studies as a distinct inter-transdisciplinary field emerging at the intersection of cultural and environmental studies. According to Ivakhiv [51], the ecocultural perspective provides a non-anthropocentric foundation for cultural studies’ theoretical stance while also extending the emancipatory focus of cultural studies traditionally centred on issues such as class, race, gender, identity, and difference, to examine the power humans exert over nature.

Expanding the academic perspective beyond ecocritical theory and cultural studies Díaz-Reviriego et al. [52] explored biocultural approaches from a sustainability perspective in the scientific literature in Spanish, based on the premise that linguistic diversity would offer a broader understanding of existing knowledge and that language is key in the construction of meaning (see also [24]). In an extensive bibliographic review covering relevant databases in Spanish from 1990 to 2021, and searching for the keywords “biocultural” (singular) and “bioculturales” (plural form of biocultural in Spanish), Díaz-Reviriego et al. [52] investigated how the scientific literature published in Spanish conceptualises and applies various biocultural approaches. Following Hanspach et al.’s [87] concept of the biocultural lens, they identified patterns that persisted over time and evolved in complexity, frequency, and consistency with which it was applied, and they also considered the depth or breadth with which the approach was explored within each article. The authors observed that most publications focused on biocultural conservation and nine identified lenses: (1) biocultural diversity; (2) biocultural heritage, memory, and knowledge; (3) biocultural conservation; (4) biocultural ethics; (5) biocultural landscapes; (6) biocultural education; (7) biocultural tourism; (8) biocultural ontologies and epistemologies; (9) biocultural lens concerned with the rights of nature. The most represented lenses in the corpus analysed by Díaz-Reviriego et al. [52] were biocultural diversity and biocultural heritage, memory, and knowledge. As a conclusion, they highlight that the way the adjective biocultural is understood in Spanish is complex and diverse, observing a prevalent concern with power and the incorporation of methodologies that contribute to decolonising knowledge and activating emancipatory transformations in human–nature relationships.

Similarly, Shiva’s [88] concept–metaphor “monocultures of the mind” has had a great impact on Latin American ecocriticism and environmental humanities. Shiva’s collection of essays describes the causes and consequences of the loss of cultural and biological diversity in Global South countries as a result of the Green Revolution, while also suggesting that uniformity and diversity are not only ways of cultivating the land but also ways of thinking and living [88]. Thus, the establishment of industrial agriculture, monoculture forestry, and the use of genetically modified seeds as a paradigm of land production would lead not only to biological uniformity but also to cultural homogeneity, showing how such monocultures contrast with ecocultures, which focus on the path of the co-evolution of humans and nature [21]. These views have informed, for instance, Mariaca’s [53] description of biocultural diversity in literary studies, that is, “the total variability exhibited by the world’s natural systems and cultures, [which] includes biodiversity (diversity of genes, species, and ecosystems) and cultural diversity (diversity of languages, worldviews, values, forms of knowledge, and practices)” (p. 15).

Overall, most of the analysed articles focus on diversity, whether from a biocultural or an ecocultural lens, with the overarching purpose of analysing and/or proposing conservation actions. In this light, a contribution the documents analysed for this section make (with the exception of [39] in Section 3.2.) relates to the inclusion of linguistic diversity as part of biocultural phenomena [24,52]. Basing their discussion on the Sapir–Whorf Hypothesis, Takatori and Hirano [24] explain that language determines human thoughts and behaviours, and represent identities and ways of living (which involve humans’ perceptions and attitudes towards nature and their environment). This, in turn, determines a culture, and thus languages are the basis of cultural diversity. This approach advocates for a global perspective on environmental issues in this field. Interestingly, another departing point from the previous two disciplinary areas (namely, Ecology and Conservation, and Economics and Heritage) is related to the conceptual turn involved in shifting from biocultural perspectives to ecocultural ones in an effort to view related matters from a more comprehensive standpoint. As explored in the preceding paragraphs, in the case of Ecocriticism and Literature the turn seems to have taken place in the opposite direction, possibly as a way of looking at the role of language from a more situated point of view.

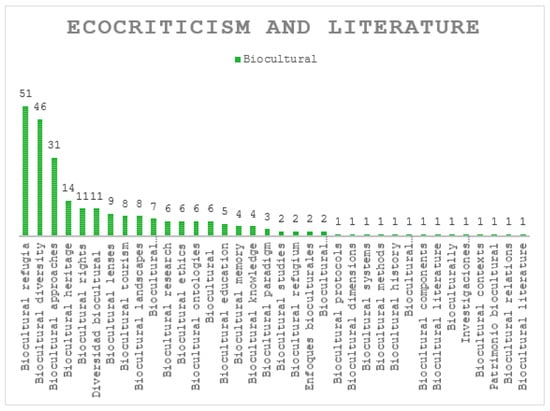

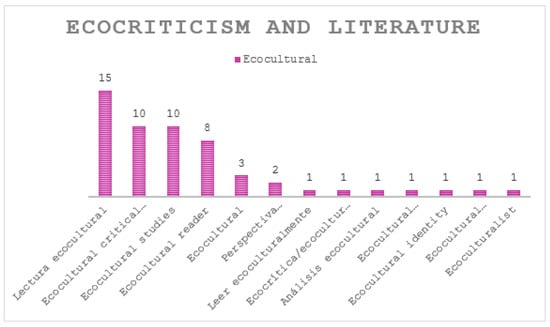

Turning to the linguistic analysis conducted for the literature review in the disciplinary field of Ecocriticism and Literature, Figure 8 illustrates the frequency with which the terms biocultural and ecocultural appear in the reviewed seven articles.

Figure 8.

Ecocultural and biocultural word mentions in articles of the disciplinary field of Ecocriticism and Literature [21,24,49,50,51,52,53].

Figure 8 shows that biocultural is mentioned 259 times in four of the seven documents reviewed in this disciplinary area. Among these, studies by Díaz-Reviriego et al. [52] stand out with a total of 175 mentions, followed by Barthel et al. [21] with 57 mentions, Takatori and Hirano [24], and Mariaca [53]. In the case of ecocultural, the concept is mentioned 55 times in three out of the seven analysed documents, with Ivakhiv [51] and Herring [49] with 24 mentions each, followed by French and Heffesg [50]. In this regard, Figure 8 reveals the same trend observed in the two previously analysed disciplinary areas, where the presence of the biocultural concept is more frequent than ecocultural, both in the number of documents and in the amount of mentions within the documents.

Regarding the collocations associated with the concepts biocultural and ecocultural, Figure 9 and Figure 10 show their collocations and their frequencies within the analysed texts.

Figure 9.

Frequency of collocations of the term biocultural in the disciplinary field of Ecocriticism and Literature.

Figure 10.

Frequency of collocations of the term ecocultural in the disciplinary field of Ecocriticism and Literature.

Figure 9 shows that the term biocultural is linked to concepts such as diversity with 57 mentions in the seven analysed documents, followed by terms like refugia with 51 mentions, approach, heritage, and rights. In these articles, the use of biocultural is predominantly associated with four semantic axes, some of which coincide with those identified in the two previous disciplinary areas. The first axis refers to biocultural diversity, with 46 mentions in English and 11 mentions (“diversidad”) in Spanish. The second concept highlighted is biocultural refugia, which relates to areas where their biodiversity is protected, and is a contribution of this disciplinary area to the semantic axes identified in this study. The third axis corresponds to the ways of approaching the issue, repeating concepts such as approach, but enriched by terms like lenses (nine mentions), ontologies (six mentions), research (seven mentions), knowledge (four mentions), paradigm (three mentions), studies (two mentions), or perspective (two mentions), some of which were also mentioned in the other two analysed disciplinary areas. These collocations (e.g., ontologies) and their frequencies may indicate deeper methodological and philosophical considerations of the concept in studies of Ecocriticism and Literature. Finally, the fourth axis refers to the notion of heritage, associated with the terms heritage (14 mentions) and rights (11 mentions). This axis is further enriched by concepts such as ethics (six mentions), education (five mentions), and memory (four mentions).

In this regard, while there is an overlap (to a certain extent) of the semantic axes identified in the literature regarding biocultural and ecocultural in the three analysed disciplinary areas so far, it is possible to observe that each disciplinary area understands, defines, and links these axes in its own way. Thus, it is important to emphasise that, while biocultural diversity is a crosscutting theme and it is frequently mentioned, in the case of the area of Ecocriticism and Literature in particular, the notion of biocultural lenses is presented from a different angle, that is, drawing on the nine lenses proposed by Hanspach et al. [87], which directly relate to some of the semantic axes identified in our article as ways of understanding the concept biocultural. Specifically, in Ecocriticism and Literature the semantic axis related to the concept of biocultural heritage is mainly connected to the rights of certain groups, such as indigenous people and rural communities, due to their levels of social and economic vulnerability regarding issues related to their relationship with the environment. Additionally, the notion of heritage involves a valuation that aims at safeguarding knowledge, practices, or ecologies that need to strengthen memory processes, as well as the educational spaces of these communities.

Notably, the ecocultural concept (Figure 10) collocates with terms such as reader in English (with 8 mentions), and “lectura” (that is, reading) in Spanish with 15 mentions, critical theory with 10 mentions, studies (10 mentions), and critical (10 mentions). In this sense, the terms associated with ecocultural are closely tied to theoretical aspects of this disciplinary field, and field-specific considerations of readership, which may offer a limited view of ecocultural matters in this area of literary studies.

3.4. Sociocultural Discourses

As in the previously analysed disciplinary areas, biocultural and ecocultural concepts emerge in sociocultural discourses as a way to resist rigid separations of nature and culture, emphasising instead relational ontologies that link ecological and cultural systems and processes. However, in the case of the studies reviewed for Sociocultural Discourses, both biocultural and ecocultural frameworks propose to move beyond their original associations with indigenous and rural contexts, and to apply the concepts to urban, and other educational, communicative, and transnational settings. This expansion reflects a recognition that ecological–cultural entanglements permeate all contexts of contemporary societies.

In this light, while some studies still investigate bioculturality in rural settings, there is a notorious shift towards exploring biocultural relationships in other, more fluid contexts. In the case of the former, for example, Shea [63] develops the idea of biocultural affinities, identifying personhood-, mirror-, and support-based affinities in the Sonoran Desert that highlight how linguistic and emotional ties to the more-than-human transcend cultural and linguistic boundaries. Very importantly, in the case of the latter, Cocks [56] emphasises that biocultural diversity should not be restricted to indigenous groups, as non-indigenous and urban populations also maintain cultural practices tied to biodiversity. This is echoed by Hosseini [60], who shows that urban parks in Moscow function as spaces of biocultural identity, where governance, culture, and ecology intersect, and by Sarmiento et al. [62], who reinforce the sacred and intangible dimensions of biocultural heritage in mountain landscapes of an urban community. Senabre Hidalgo et al. [59] extend this trajectory into the digital humanities by using collaborative writing as a vehicle for knowledge co-production where scholars and other stakeholders engage in the co-creation of a manifesto on biodiversity in relation to linguistic and cultural diversity. Moreover, Krupar and Ehlers [61] reinterpret biocultures through a biopolitical lens, analysing how biomedical rationalities shape governance and inequality, while Merçon et al. [10] expand the scope to a biocultural paradigm that bridges local practices with global sustainability governance.

The ecocultural framework mirrors this expansion but foregrounds discourse, pedagogy, and communication. For instance, Castro-Sotomayor [64] analyses ecocultural identities at the Ecuador–Colombia border, showing how indigenous Awá organisations negotiate global sustainability discourses through territorial practices. Dickinson [65,66] identifies contradictory ecocultural messages in forest education and frames ecocultural conversations as communicative practices that disrupt human–nature binaries. Greenberg and Greenberg [67] highlight ecocultural narratives as ecoethical tools in land-use negotiations, while Stibbe [72] focuses on linguistic constructions of positive ecocultural identities.

Education certainly provides a rich field of application and applied linguistics for ecocultural exploration: Jayantini et al. [68,69] promote ecocultural sustainability in EFL curricula in Bali, and Wardana [73] explores how Balinese figurative speech functions as a cultural and linguistic resource for embedding ecocultural values in character education. These works show how language, pedagogy, and storytelling are central vehicles for ecocultural engagement. In addition, Lamb [70] expands this work into the economic sphere by analysing how sea turtles circulate as symbols within ecocultural tourism in the discursive practices of different stakeholders, while Milstein et al. [71] introduce ecocultural reflexivity as a tool to interpret Western environmental imaginaries shaped by infrastructure and control systems.

Convergences between the two frameworks are clear within the studies analysed for Sociocultural Discourses. Both biocultural and ecocultural scholarship reject rigid ideas of the human–nature divide, affirm the co-constitution of cultural and ecological systems, and stress the importance of identity, rights, ethics, and discourse, mediated by understandings of sustainability, governability, and diversity. As an example, biocultural identity in urban parks [60] intersects with ecocultural identity within the self [51] and [72] and at transnational borders [64], and with Shea’s [63] idea of biocultural affinities, as both concepts articulate identity construction with aspects of ecological belonging. Both perspectives emphasise that cultural self-understanding is inseparable from ecological belonging, and that identity construction extends across human and non-human worlds.

Pedagogical applications illustrate another point of intersection. Geerling [58] interprets the literature as biocultural pedagogy, where stories transmit ecological ethics, while Fisk [57] highlights biocultural systems embedded in Taíno ecolinguistics. Similarly, Jayantini et al. [68,69] articulate an ecocultural approach to education, integrating local wisdom into English as a Foreign Language curriculum in Bali. From an interdisciplinary education perspective, both terms may function as applied pedagogical paradigms, fostering place-based and culturally grounded (or situated) forms of sustainability education.

Yet, divergences persist. Biocultural approaches often emphasise heritage, governance, and stewardship, extending their enquiry into biopolitics and digital collaboration [10,59,61]. For example, Bavikatte and Bennett [54] introduce the notion of biocultural rights as collective entitlements rooted in communities’ customary stewardship of land. As a paradigm for governance, for instance, Burke et al. [55] highlight how indigenous and local knowledge underpins biocultural sustainability initiatives, even when asymmetries of power persist in knowledge co-production. These studies stress that ecosystems cannot be safeguarded without preserving the cultural traditions and ethical orientations that sustain them. By contrast, ecocultural perspectives privilege discourse and reflexivity, emphasising how communication and education serve as transformative tools [66,69,73]. Thus, even when biocultural perspectives highlight the role of language and narrative in revitalization [57,58], ecocultural approaches are deeply invested in discourse analysis: Dickinson [65] introduces ecocultural schizophrenia to capture contradictory environmental discourses, while Stibbe [72] further proposes a “grammar of ecocultural identity,” identifying linguistic devices that cultivate ecological values.

Taken together, the analysed studies within the field of Sociocultural Discourses demonstrate how both concepts adapt to contemporary contexts while maintaining their core concern with cultural–ecological entanglements. Their intersections reveal complementary emphases—biocultural on governance and rights, ecocultural on discourse and pedagogy. This highlights the value of combining these perspectives to address sustainability, identity, and justice in plural and modern settings.

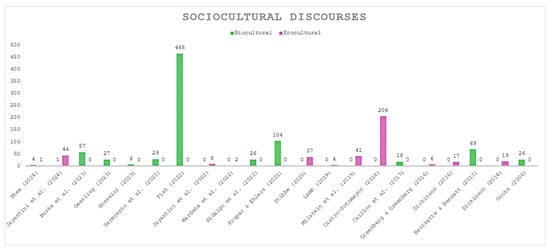

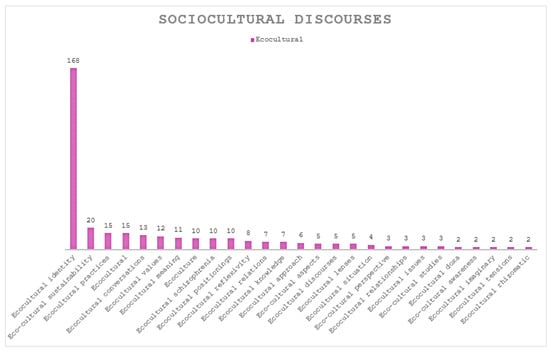

These interpretations are further supported by the corpus analysis. Figure 11 presents a comparative analysis of the frequency of the terms ecocultural and biocultural across the 21 articles analysed for Sociocultural Discourses.

Figure 11.

Ecocultural and biocultural word mentions in articles in the disciplinary field of Sociocultural Discourses [22,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73].

Both terms appear in a similar number of sources (11 documents for the term ecocultural and 12 for biocultural), which coincides with the frequency of occurrence of both concepts, since the term “biocultural” appears 382 times and “ecocultural” 385 times. Figure 11 also reveals that the highest concentration of mentions of “biocultural” occurs in Fisk [57], with 465 mentions, followed by Krupar and Ehlers [61], and Bavikatte and Bennett [54]. As for the frequency of the occurrence of the concept “ecocultural,” it is most frequently mentioned in Castro-Sotomayor [64] with 206 mentions, followed by Jayantini et al. [69] and Milstein et al. [71].

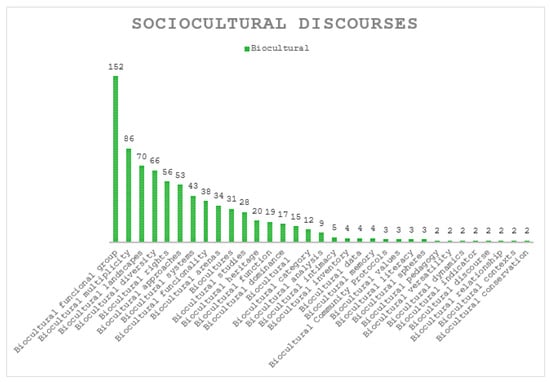

Regarding the collocations associated with the concepts biocultural and ecocultural, Figure 12 and Figure 13 show their collocations and their frequencies within the analysed texts.

Figure 12.

Frequency of collocations of the term biocultural in the disciplinary field of Sociocultural Discourses.

Figure 13.

Frequency of collocations of the term ecocultural in the disciplinary field of Sociocultural Discourses.

Of the 382 mentions of biocultural, the most frequent collocations include biocultural functional (152), biocultural multiplicity (86), and biocultural landscapes (70), followed by biocultural diversity (66) and biocultural rights (56). These frequencies suggest a strong focus on pragmatic, diverse, and territorial dimensions within biocultural discourses. Less frequent but still interesting collocations include biocultural approach (53), biocultural systems (43), and biocultural heritage (20), highlighting the concept’s versatility across educational, theoretical, and identity-based frameworks. On the other hand, the 385 mentions of ecocultural are concentrated into fewer collocations. Ecocultural identity is the dominant one, with 168 mentions—over 40% of the total—indicating a central concern with identity formation in ecocultural contexts. Other collocations include ecocultural sustainability (20), ecocultural practices (15), ecocultural conversations (13), and ecocultural values (12). Overall, this comparison reveals that while the term biocultural draws on broader discourses of practices as heritage, for instance, the term ecocultural focuses more narrowly on discourses of local practices and situated conversations and interactions of ecocultural features, with identity as its most prominent concern.

4. Conclusions

This article aimed to provide a critical and contextually situated conceptual review of the literature by analysing the scope, uses, and meanings attributed to the terms ecocultural and biocultural in the four disciplinary areas encompassed in the Anillos ANID ATE230028 project, namely, Ecology and Biodiversity Conservation, Economics and Heritage, Ecocriticism and Literature, and Sociocultural Discourses. In line with this objective, the analysis undertaken in this study was conceived as an integrative endeavour to synthesise the existing definitions, uses, and applications of both concepts across disciplinary contexts, building upon influential theoretical work to advance their articulation within contemporary interdisciplinary frameworks. The narrative and linguistic analyses show that the concepts biocultural and ecocultural emerge in these diverse disciplinary contexts to describe the interdependence of human culture and the non-human world. Both frameworks resist rigid separations of nature and culture, emphasising instead relational ontologies that link ecological systems with cultural practices, identities, and governance, among others. Taken together, these perspectives illustrate how the four disciplinary areas considered in this paper converge on identity as a shared interdisciplinary site, where biocultural and ecocultural mutually enrich analyses of place, belonging, and subjectivity. Moreover, in the four disciplinary areas analysed, both paradigms also converge in their recognition of plural knowledges (where interdisciplinarity has a main role to play) towards a shared goal: attaining sustainability.

Yet distinguishing between biocultural and ecocultural perspectives reveals important differences in focus, spatial coverage, and temporal depth. The biocultural approach centres on specific species and their immediate environments, often emphasising mechanisms within systems and human relationships with nature in a rather static and localised context. While it is generally species-centred, the biocultural approach highlights human relationships with specific organisms, yet to a certain extent lacking contextual depth and temporal scope. In contrast, the ecocultural approach offers a more expansive and process-oriented view, incorporating both biotic and abiotic components of ecosystems and their dynamic interactions over time and space. Thus, while biocultural systems explore mechanisms within specific contexts, ecocultural processes emerge from the cumulative interplay of biocultural practices across time and space, contributing to a more holistic understanding of human/non-human relationships. As a consequence, while biocultural expressions are somewhat foundational, it is their accumulation and transformation through time that give rise to ecocultural processes—making ecoculture a more comprehensive and temporally informed framework for understanding the human/non-human relationships, especially in the context of environmental change.

In addition, divergences also emerge in the emphasis each disciplinary area places on the different aspects that constitute bio- and ecocultures. On the one hand, biocultural approaches have been found to be more often related to diversity, rights, heritage, ethics, policies, and governance, highlighting a theoretical preoccupation under its enquiry. On the other hand, ecocultural approaches foreground communication, discourse, reflexivity, values, and identity studies, following critical discursive and literary approaches, and reflecting a more pragmatic stance of enquiry. In this light, while biocultural approaches seem to be more comprehensive in their enquiry, covering a wider range of topics and perspectives on the matter, ecocultural approaches seem to be more vaguely treated in the first two disciplinary areas and very limitedly addressed in literary and discursive studies with regard to the amount of topics they cover. This, together with the lack of clarity regarding the conceptual boundaries between the two terms, may be connected to the unbalanced scholarly attention paid to ecocultural matters compared with biocultural matters, both in the amount of studies focusing on each approach as well as the amount of occurrences of the terms within the analysed documents. Thus, one of the challenges of scientific development is to increase scholarly endeavours in ecocultural matters and to provide a wider range of topics of study, while also contributing interdisciplinary perspectives for its exploration.

Based on the above, and considering some of the study’s limitations, we propose the following recommendations and future research directions, with interdisciplinary teams in mind in particular:

- The way in which these two concepts are defined in a study and/or research project provides both researchers and readers with a framework for interpreting and understanding a specific study subject. Hence, their use reflects a research stance that requires epistemological awareness in order to critically recognise the impact of adopting (or not) a biocultural, ecocultural, or a combined perspective. For this reason, it is essential that researchers reflect on, examine, and clearly define the use of these concepts with their research teams, particularly in interdisciplinary work settings, and in relation to the community context in which the research takes place.

- Promoting dialogical and interdisciplinary research processes in the development of scientific studies is, as this review demonstrates, paramount, since the concepts biocultural and ecocultural are enriched and made more complex by the contexts in which they are utilised. A dialogic approach broadens perspectives towards a more open and comprehensive understanding of biodiversity, ecosystems and cultural practices, and other elements that may be relevant to consider within systemic notions and/or more process-oriented views of human–ecosystem dynamics.

- It is also important to move beyond the concepts’ original associations with indigenous and rural contexts and to expand their application to urban, educational, communicative, and transnational settings, to suggest a few. This expansion would reflect a recognition that ecological–cultural entanglements play a role in all contexts of contemporary societies and require interdisciplinary approaches that acknowledge the resilience and adaptability of these ties under conditions of globalisation (and, very importantly, climate change).

- One of the limitations of this study may be that the review process did not yield studies involving ex situ conservation practices of indigenous domesticated and undomesticated culturally important species (such as seed banks, botanical gardens, cryopreservation, or tissue culture). Future interdisciplinary discussion on the subject should examine whether ex situ conservation can be conceptually positioned within biocultural and ecocultural frameworks, as it could be argued that ex situ conservation does not necessarily represent a “place-based”, “living” or “traditional” cultural practice.

In sum, this study advances scientific knowledge by providing a critical and contextually situated conceptual review of biocultural and ecocultural frameworks, clarifying their meanings, scope, and interdisciplinary applications. Socially, it offers recommendations for dialogical approaches that strengthen collaborative interdisciplinary research and that expand applications beyond rural contexts to urban, educational, and policy domains.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L.-S., K.C.-J., E.A.M. and Á.S.; methodology, M.L.-S., K.C.-J., E.A.M. and Á.S.; formal analysis, M.L.-S., K.C.-J., E.A.M., Á.S., X.Q.-D., D.M.-C., E.C.M., A.C.H. and S.R.; investigation, M.L.-S., K.C.-J., E.A.M., Á.S., X.Q.-D., D.M.-C., E.C.M., A.C.H. and S.R.; resources, E.A.M. and M.L.-S.; data curation, M.L.-S., K.C.-J., E.A.M. and Á.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L.-S., K.C.-J., E.A.M., Á.S., X.Q.-D., D.M.-C., E.C.M., A.C.H. and S.R.; writing—review and editing, M.L.-S. and E.A.M.; visualisation, M.L.-S., K.C.-J. and E.A.M.; supervision, M.L.-S. and E.A.M.; project administration, E.A.M. and M.L.-S.; funding acquisition, E.A.M. and M.L.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Anillos Project (ANID ATE230028), entitled “Biodiversity from Coast to Mountains: A socio-environmental study of rural communities’ (Eco)2-Cultural practices in a scenario of Climate Change” (2023–2026).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Core Writing Team, Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPBES. Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; Brondizio, E.S., Settele, J., Díaz, S., Ngo, H.T., Eds.; IPBES secretariat: Bonn, Germany, 2019; p. 1148. [CrossRef]

- Barnosky, A.D.; Matzke, N.; Tomiya, S.; Wogan, G.O.U.; Swartz, B.; Quental, T.B.; Marshall, C.; McGuire, J.L.; Lindsey, E.L.; Maguire, K.C. Has the Earth’s sixth mass extinction already arrived? Nature 2011, 471, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toledo, V.M.; Barrera-Bassols, N.; Boege, E. ¿Qué es la Diversidad Biocultural? 1st ed.; UNAM: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2019; pp. 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, J.; Lukawiecki, J.; Young, R.; Powell, L.; McAlvay, A.; Moola, F. Operationalizing the biocultural perspective part II: A review of biocultural action principles since The Declaration of Belém. Environ. Sci. Policy 2023, 150, 103573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]