Abstract

This paper presents the Living Lab Assessment Method (LLAM), a context-sensitive framework for assessing impact and value creation in Living Labs (LLs). While LLs have become established instruments for Open and Urban Innovation, systematic and transferable approaches to evaluate their impact remain scarce and still show theoretical and practical barriers. This study proposes a new methodological approach that aims to address these challenges through the development of the LLAM, the Living Lab Assessment Method. This study reports a five-year iterative development process embedded in Ghent’s urban and social innovation ecosystem through the combination of three complementary methodological pillars: (1) co-creation and co-design with lead users, ensuring alignment with practitioner needs and real-world conditions; (2) multiple case study research, enabling iterative refinement across diverse Living Lab projects, and (3) participatory action research, integrating reflexive and iterative cycles of observation, implementation, and adjustment. The LLAM was empirically developed and validated across four use cases, each contributing to the method’s operational robustness and contextual adaptability. Results show that LLAM captures multi-level value creation, ranging from individual learning and network strengthening to systemic transformation, by linking participatory processes to outcomes across stakeholder, project, and ecosystem levels. The paper concludes that LLAM advances both theoretical understanding and practical evaluation of Living Labs by providing a structured, adaptable, and empirically grounded methodology for assessing their contribution to sustainable and inclusive urban innovation.

1. Introduction

Open Innovation (OI) is a collaborative way of developing new technologies where organizations look beyond their own walls. Chesbrough [1] explains that enterprises should not only use ideas and routes to market from inside the organization, but also work with ideas, knowledge and partners from outside. Although the Open Innovation concept originated in the private sector, it is now also applied in Higher Education Institutes [2] and in organizations with societal agendas [3]. These organizations adopt OI strategies to mobilize local resources and support knowledge exchange among communities, helping them to address pressing societal issues. Researchers therefore see more collaborative and societal forms of open innovation as an important direction for future work in this field [4]. This development aligns with today’s world, where rapidly changing technologies and interconnected global systems increase socio-political and socio-ecological complexity [5].

In this context of so-called ‘wicked problems’, Living Labs (LLs) are often described as a practical way to apply the OI paradigm. LLs bring together principles from Open Innovation and User Innovation in a structured way [6,7]. They offer a practical framework to guide decentralized innovation by encouraging stakeholders to collaborate, with end-users taking a central and co-creative role in real-life settings [6,8]. Over the years, many different types of LLs have emerged. They share some basic principles, but each type has its own specific focus. Examples include agro-ecology LLs [9], university campuses that function as LLs [10,11] and LLs that act as testbeds for new technologies and products [12,13]. Urban environments form another important context, especially when addressing “wicked problems” that often have an urban nature [14,15,16,17].

Urban Living Labs (ULLs) are LLs that focus on urban challenges. These labs are embedded in cities and support transitions toward more sustainable urban futures by tackling complex societal challenges such as population growth, aging, climate change, and public transport [14,16]. ULLs build on the broader LL tradition. They function as user-centered Open Innovation ecosystems that use systematic, citizen-oriented co-creation methods. They combine research and innovation in real-life urban settings [18,19] Steen and van Bueren [19] add the idea of “place-based labs,” emphasizing their grounding in specific physical locations within the city.

Interest in LLs is growing among both practitioners and researchers because LLs have shown that they can create value in (urban) innovation ecosystems and help cities become more resilient. Moreover, Urban Living Labs, in particular, can trigger systemic change within these networks [16,17,20]. Various sources of literature have studied these broader effects from various perspectives. Beyond stimulating Open Innovation [21,22]. ULLs help bridge the gap between developing, producing, and actually adopting urban solutions; involve many different stakeholders in this development process; use and share knowledge that is spread across these stakeholders; and support new partnerships and transdisciplinary collaborations [17,19,23]. Earlier research also shows that ULLs strengthen stakeholders’ absorptive capacity: their ability to take in and use external knowledge [22], dynamic capabilities: their ability to adapt to change [6,24,25], and connective capabilities: their ability to build and maintain connections and collaborations [26,27]. These dimensions of value creation increase the appeal of ULLs in urban policy [19] and have encouraged cities to adopt more experimental, place-based approaches.

Despite their transformative potential, assessing ULLs remains challenging. Hossain et al. [28] identify issues such as short project lifespans, stakeholder governance difficulties, limited efficiency in knowledge transfer, problems with keeping users engaged, and insecure funding. Gascó [29] categorizes these issues under “sustainability” and “scalability” challenges, and notes their link to short-term funding structures. In addition, diverging stakeholder expectations may also cause tensions [30]. These conceptual and practical uncertainties also affect researchers and practitioners. Without robust assessment frameworks, it is difficult for scholars to build theory on LLs, and for practitioners to demonstrate societal value in times of shrinking public budgets [20,23]. A key problem is the lack of robust frameworks to assess the impact and value creation processes of ULLs. Although many authors stress the need for more systematic impact assessment [19,31,32], the methodological foundations are still underdeveloped. Most existing studies rely on qualitative and often anecdotal evidence, such as comparative case studies. These provide rich contextual insight, but they are hard to generalize and do not support the development of broadly applicable assessment frameworks. Ahn et al. [3] similarly argue that the societal impact of open innovation LLs is still poorly understood because validation remains mostly anecdotal. Quantitative approaches could, in theory, offer more standardization and scalability, but they often demand substantial resources [16,33] and risk reducing complex, evolving, and relational value processes to narrow sets of indicators. For example, even though several studies link digital twin development and ULLs [34], the growing reliance on digital twins to simulate urban interventions may overlook intangible and collaborative dimensions of value creation that are central to LL practice.

This paper responds to these gaps by introducing a new assessment method. Building further on the conference paper of Robaeyst et al. [35]. The Living Lab Assessment Method (LLAM) is a flexible, project-based framework that can be used to evaluate LLs in both qualitative and quantitative ways. It is a multi-purpose method: it supports measuring impact, analyzing how value is created, reflecting on strategy, communicating results, and planning future LL projects. The LLAM is designed for everyday use by LL practitioners, but it also follows academic standards so that results are rigorously established. The method was developed and tested in the City of Ghent, which has over twenty years of experience with LLs that bring together government, universities, companies, and citizens [36]. Despite this long tradition, no explicit or systematic framework for impact assessment was in place prior to 2020. This made it urgent to develop an approach that makes the value of LL projects visible and measurable. In this context, the LLAM was developed over five years within Ghent’s social and urban innovation ecosystem. The process combined step-by-step experimentation, empirical testing in four use cases, and ongoing theoretical reflection. Through various case applications, the proposed method (LLAM) was improved to become more practical while verifying its usefulness and validity. This paper reports on that development process. Using data from the four use cases, it shows how the LLAM was gradually designed, refined, and validated in different projects of the City of Ghent.

After this introduction, the paper first explains the methodological approach on how the LLAM was developed. It describes the use cases, the development steps, and how the LLAM was put into practice and adapted over time. The results section then presents the main elements of the LLAM, including its theoretical foundations, objectives and applications, value dimensions, and a suggested process for using the method in (Urban) LL contexts, together with an empirical account of how it evolved.

Because of this structure, the full design of the LLAM only becomes clear later in the paper. Readers are therefore invited to consult the LLAM manual as a Supplementary Materials attached to this manuscript.

2. Methodology

To develop the LLAM, we collected data in four use cases that helped us design, refine, and validate the method. In these use cases, we used a multi-method, iterative research design based on three complementary methods: co-creation and co-design with lead users [35], multiple case study research [1], and participatory action research [2] (Table 1). These approaches allowed us to continuously co-develop the LLAM through feedback loops and regular reflection between researchers and practitioners.

Table 1.

Overview of conducted methodology.

We did not treat the use cases as separate, stand-alone studies. Instead, we used them as consecutive steps in one ongoing co-creation and co-design process. Each case informed the next, so that we could improve the LLAM step by step using the insights gained so far. This case-driven iteration strengthened the ecological and contextual validity of the LLAM, while recent theoretical work on LLs provided an academic foundation throughout the development process.

2.1. Co-Creation and Co-Design with Lead Users

Our first method was the structured use of co-creation workshops with lead users. In our case, these lead users were LL practitioners who were actively involved in the City of Ghent’s innovation projects. Following a user-centered innovation approach [25,37], these practitioners contributed their experiential knowledge to shape the framework for the LLAM. This collaborative design process helped us to ensure that the emerging framework reflected real-life conditions, challenges, and success factors, and was therefore relevant and credible for end-users.

2.2. Multiple Case Study Research

Our second method was a multiple case study design [38,39] (Yin, 2014; Eisenhardt, 1989). We developed and tested the LLAM across several different LL projects within Ghent’s social and urban innovation ecosystem. Each case served as a context in which we put specific components of the LLAM into practice, observed how they worked, and adjusted them based on the results and findings. The cases varied in their themes, stakeholder composition, and levels of maturity, which allowed us to compare them. Insights from one case informed changes and improvements in the next, which helped us make the framework more robust.

2.3. Participatory Action Research

Our third research method was Participatory Action Research [40,41,42]. As researchers, we were engaged in the LLs where we applied the LLAM as reflective practitioners [43]. This meant that implementing the assessment method in a project always went hand in hand with observing how it worked and refining it in practice. Reflexivity was central to this process. We documented and analyzed each application of the LLAM and then decided which adjustments to make for the next iteration. This PAR approach helped us to ground the development of the framework in real-world practice. It supported mutual learning between academics and practitioners and enabled continuous, context-sensitive adaptation of the LLAM in each cycle of action and reflection.

3. Results

3.1. Use Cases and Iterative Development of the LLAM

Between 2020 and 2024, we worked on a series of use cases in and around the City of Ghent’s innovation ecosystem. These ranged from small neighborhood projects to city-wide programs. Each case provided specific insights that enabled us to design, refine and validate the LLAM.

In the sections below, we describe the different use cases. For each case, we outline the context, explain how we operationalized and applied the LLAM framework, and summarize the main insights and lessons learned. At the end of this section, Table 2 provides an overview of all use cases and their contributions.

Table 2.

Overview of the Use Cases in which the LLAM was applied, tested and their iterative findings on the LLAM development.

- Use Case 1: Collections of Ghent (2020–2023)

- Context

Collections of Ghent served as an early LL initiative that provided the starting point for the development of the LLAM. Between 2020 and 2023, we used this project to explore how digitized cultural heritage could strengthen social cohesion in three neighborhoods in Ghent. We organized activities in public space and community-based events, and used the project as a real-life testbed to try out first ideas for impact assessment in a LL. At that time, Ghent’s innovation ecosystem lacked a structured method to evaluate societal impact. We addressed this gap by setting up a participatory evaluation together with local stakeholders. Through workshops and interviews with community actors, we explored how the project activities influenced social life and local interactions. The full project impact assessment report and the detailed methodology can be found through the following weblink: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5fca0ec5d2462a1c4e231ac0/t/64f09ae781c39007c21e1f96/1693489901855/O4.4.1+-+Impact+assessment+report+%28includes+D4.4.1+and+D4.4.2%29+%281%29.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- LLAM operationalisation

We operationalized the LLAM for the first time by combining participatory methods with a Theory of Change (ToC) framework. This combination allowed us to build an evaluation that was conceptually robust, while remaining closely aligned to the specific context and needs of the neighborhoods involved.

In the first phase, we developed an initial impact model that integrated participatory and social innovation perspectives. We reviewed existing evaluation methods and used a participatory process to co-create an impact framework tailored to the three neighborhoods. Through workshops and interviews with community workers, local organizations, and residents, we collaboratively identified project inputs, activities, expected outputs, and desired outcomes.

This co-creative approach ensured that the developing framework reflected local priorities and social dynamics. The Theory of Change provided a clear causal pathway, while stakeholder engagement ensured that the indicators and evidence types were meaningful and appropriate.

In the second phase, we collected empirical evidence for the jointly defined outcomes using qualitative methods. Together with stakeholders, we identified which data to collect and organized focus groups, interviews, and field observations. These methods helped us capture perceived and observed changes in community interaction, social cohesion, and the use and appreciation of cultural heritage.

Through this process, we demonstrated that combining participatory assessment with a Theory of Change enables a structured yet context-sensitive LL evaluation.

- Key-insights/findings and adaptations for the LLAM

This use case contributed to the development of the LLAM in the following ways:

- The first version of the LLAM was developed and tested in the specific context of the CoGhent project.

- The combination of participatory methods and a Theory of Change proved to be a balanced and context-sensitive evaluation approach.

- Early and continuous involvement of local stakeholders was essential to ground the framework, increase its relevance, and strengthen its legitimacy.

- Stakeholders played a central role in identifying meaningful indicators and shaping both the impact/value framework and the evaluation process.

- The project confirmed the practical usefulness of structured causal reasoning (Theory of Change) as a core methodological principle for the LLAM.

- A phased and participatory assessment approach enabled iterative refinement of the evaluation model.

- Qualitative methods were necessary to capture neighborhood-level changes in interaction, social cohesion, and the use and appreciation of cultural heritage.

- Co-development increased shared ownership and improved the quality and usability of the evaluation.

- The work showed that a context-specific framework can remain adaptable and scalable, forming a foundation for later iterations of the LLAM.

- Use Case 2: Comon—Cycle One (Making Healthcare More Understandable, 2020–2022)

- Context

Comon is an Urban Living Lab in Ghent that tackles complex urban challenges through participatory innovation cycles. Its first cycle (2020–2022, with follow-ups through 2025) focused on making healthcare more understandable and accessible for city residents. Running in parallel with the CoGhent project (use case 1), Comon also placed strong emphasis on assessing the value created by LL activities.

Comon is rooted in the quadruple helix model and brings together local government, academia, industry, and citizens to co-create technological and social solutions for urban challenges. This inclusive setup offered an ideal environment to further develop and test the participatory evaluation methods that later supported the development of the LLAM. As part of the impact assessment, stakeholders were invited to reflect on the value generated throughout the project, which helped uncover unintended and emergent forms of value creation that could inform the LLAM’s further development. The full report on the value assessment of Comon can be found through the following weblink: https://comon.gent/sites/default/files/inline-files/Comon%20Eindrapport%20Eng.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- LLAM Operationalization

To further refine the LLAM framework, we carried out a stakeholder-centered qualitative evaluation to build a broad and holistic view of value creation in the Ghent innovation ecosystem. As part of this process, we conducted twenty in-depth interviews (n = 20) with representatives from all four helices. In these conversations, we explored their motivations, perceived benefits, and views on Comon’s contribution to collaboration across sectors.

Our analysis of these interviews led to ten value dimensions that together captured the different ways in which the project created impact. These dimensions ranged from concrete results, such as new prototypes and improved digital skills, to more intangible value, including stronger networks, greater awareness of local health challenges, and increased cross-sector learning.

Stakeholders later validated these value dimensions, and they were published in both a public report and an academic article [44]. Through a further academic study and qualitative analysis methods, the 10 value dimensions were synthesized the ten value dimensions into seven broader categories: entrepreneurial capacity, connective capacity, knowledge capacity, instrumental capacity, agenda setting, hedonism, and altruism. This grouping provides a coherent structure for interpreting the different types of value identified in the evaluation.

Because these categories cover both tangible and intangible forms of value, they offer a useful lens for understanding how LLs in general, and ULLs in particular, create impact in a more abstract and holistic way.

- Key-insights/findings and adaptations for the LLAM

This use case contributed to the development of the LLAM in the following ways:

- Through 20 in-depth interviews across all four helices, the Comon project introduced a stakeholder-centered assessment method grounded in participants’ motivations and perceived value.

- The Comon project provided the empirical basis for identifying seven overarching value dimensions of an Urban Living Lab.

- The project established a shared vocabulary of value dimensions, including entrepreneurial capacity, connective capacity, knowledge capacity, instrumental capacity, agenda setting, hedonism, and altruism.

- These seven categories were incorporated into the LLAM as a deductive framework for assessing broad, diverse, and holistic forms of impact and value creation in LLs.

- By synthesizing 10 initial dimensions into seven structured categories, the Comon project delivered a clear, evidence-based lens for interpreting both tangible and intangible outcomes.

- This integration helped bridge practice-based insights with emerging theoretical perspectives on value creation in ULLs.

- Use Case 3: City of Ghent—Living Lab Community of Practice (2021–2023)

- Context

The Living Lab Community of Practice (CoP) was a meta-level initiative set up by the City of Ghent’s Innovation Department to strengthen learning and knowledge exchange across several ongoing LLs in the city. It brought together projects such as Collections of Ghent, Comon, and a range of university- and city-led initiatives in education, urban planning, and social innovation. The goal of the CoP was to bring together insights from these diverse initiatives and to build a shared understanding of how their societal impact could be assessed and improved.

The CoP started with two introductory meetings in which members jointly defined the main ambition: to develop a shared approach for evaluating the impact of LLs in the City of Ghent. Building on this foundation, two additional workshops/focus groups were organized in which members worked with a preliminary version of what would later become the Living Lab Assessment Method (LLAM).

In these sessions, insights from the CoGhent and Comon projects were combined with experiences from other LL initiatives in the city. Through structured reflection and joint analysis, these inputs were synthesized and integrated into an evolving assessment framework. Within this collaborative setting, the method received its formal name, LLAM (Living Lab Assessment Method), and its conceptual foundations were collectively validated.

By enabling practitioners to compare needs, evaluation practices, and methodological challenges across projects, the CoP played a key role in building a coherent and shared evaluative framework. This process ultimately led to the formal consolidation of the LLAM.

- LLAM Operationalization

The formal version of the LLAM was developed in this use case, as creating a shared impact framework became the main goal of the CoP. To support this process, two sequential focus groups (FG1 and FG2) were organized with LL coordinators and team members, who participated as lead users (Table 3).

Table 3.

Participants in Community of Practice Focus Groups (Use Case 3).

- Focus Group 1

FG1 (n = 8) looked at LLs from a broad, cross-project perspective. Using a Theory of Change approach, participants mapped general project goals, activities, outputs, and assumptions about how these create value in LLs.

By combining this with the value dimensions proposed by Robaeyst et al. [44], the group identified a set of recurring value themes that matter for LLs, such as network capacity building, skills development, instrumental capacity, real solution generation, agenda setting, and knowledge capacity enhancement. For each of these themes, first ideas for qualitative and quantitative indicators were drafted to guide later data collection.

A key result of FG1 was a recalibration of the value dimensions proposed by Robaeyst et al. [44] into six impact and value dimensions that better fit the LL context. Most dimensions only needed small changes in wording. However, the dimension “altruism” was reinterpreted and merged into “real solution generation,” because it fit more naturally with the intended outcomes in that category. The dimension “hedonism” was viewed as an additional, non-essential form of value creation in Living Labs. It did not align well with the types of value typically generated in Living Lab projects. Since participants also emphasized the need for a clear and practical focus in the LLAM, this dimension was left out of the model. Together, these steps led to the first draft of the LLAM impact framework.

- Focus Group 2

FG2 (n = 6) then tested, validated, and refined the draft framework by applying the LLAM to participants’ own LL projects. This hands-on use helped clarify important conceptual differences, such as the distinction between outcomes and longer-term impacts, and led to more operational and precise indicator definitions.

FG2 also produced two concrete methodological tools: a step-by-step application guide to help practitioners implement the LLAM, and the Living Lab Value Fingerprint, a spider chart that visualizes expected, emerging, and achieved impacts. The latter responded to a recurring challenge in LL projects: the lack of clear and quickly understandable visualizations of impact-related information.

At the end of this use case, the result was a framework that was ready to be applied in a real-world setting.

- Key-insights/learning and adaptations for the LLAM

This use case contributed to the development of the LLAM in the following ways:

- The framework received its formal name: Living Lab Assessment Method (LLAM).

- Iterative refinement through repeated application within the Community of Practice strengthened both robustness and usability.Peer-based co-validation improved conceptual clarity and ensured contextual relevance across diverse Living Lab settings.

- Theoretical impact concepts were aligned with practitioners’ experiential knowledge, resulting in more appropriate and realistic value dimensions.

- The Living Lab Value Fingerprint was developed as a practical tool to visualise the value a project intends to generate or has achieved, while a complementary step-by-step application guide was created to support operational use and improve applicability of the LLAM.

- Cross-project learning was reinforced, creating a shared evaluative language and increasing practitioner ownership of the method.

- Use Case 4: Ghent Labour Pact—Six Experimental Living Lab Projects (2023–2024)

- Context

The Ghent Labor Pact (Arbeidspact) was a city-led initiative that used LL methodologies to address challenges in work and activation, such as unemployment, workforce development, and social inclusion. Within this program, the City of Ghent funded 14 small-scale innovation projects. Six of these were selected to pilot the LLAM, after city officials who had taken part in the Community of Practice (Use Case 3) recognized that the method offered a structured, holistic, and participatory way to evaluate projects.

Three of these projects had already been completed and three were still ongoing. Together, they provided an important opportunity to test the LLAM’s applicability across several parallel projects in a new policy domain and a different LL context.

In practice, the Labor Pact enabled reflection on two complementary levels. First, the LLAM supported project-level assessment by making the added value of the Arbeidspact funding visible at the level of each individual project. This allowed the City of Ghent to review progress, outcomes, and learning processes in a more systematic and comparable way.

Second, the combined insights from these project evaluations fed into a broader strategic discussion about the role of local government in Ghent’s urban innovation ecosystem. Reflections on project-level value creation helped the City to rethink its role not only as a funder, but also as an enabling actor within a wider landscape of social and labor-market innovation. The full and public report of the Ghent Labour Pact assesment exercise can be found through the following link: https://stad.gent/nl/werken-ondernemen/nieuws-evenementen/onderzoek-heeft-het-projectenfonds-van-het-gentse-arbeidspact-meerwaarde-gecreeerd (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- LLAM Operationalization

Three workshops were organized in 2023–2024 (Table 4). In Workshops 1 and 2, project teams reconstructed their Theory of Change by identifying inputs, activities, outputs, and intended outcomes. They then used the Living Lab Value Fingerprint to visualize their impact profiles. Workshop 1 focused on projects that had already been completed, while Workshop 2 focused on projects that were still in progress and could still be adjusted. Together, these sessions provided an overview of the six selected projects and the value or impact they generated.

Table 4.

Overview of Workshops in the Ghent Labour Pact (Use Case 4).

Workshop 3 shifted the focus to the program level. Here, participants examined shared impacts across projects, recurring challenges, and the strategic role of the City of Ghent as both a funder and a facilitator of innovation.

The insights from these workshops can be summarized on two connected levels: project-level operationalization and program-level operationalization.

- Project-Level operationalisation

Across the six experimental projects funded through the Labor Pact, the LLAM made a broad range of value creation and value capture visible. This included concrete outputs such as prototypes, digital tools, and new service concepts, as well as more intangible but equally important forms of impact.

The LLAM helped clarify how the projects contributed to less tangible dimensions such as ecosystem network development and stronger collaborations, knowledge development and exchange, cross-organizational learning, and better alignment between partners.

The LLAM proved especially helpful in Workshops 1 and 2. When project teams wrote out their Theory of Change, they uncovered assumptions and gaps in their plans that had not been visible before. This made it easier to adjust ongoing projects. For example, some teams decided to involve extra partners once they saw who was missing, such as mental health organizations in youth projects or IT support services in projects with digital training.

By making these elements explicit, the LLAM also supported clearer conversations between project teams and City officials about what counts as success. The method helped everyone see that value is not only created when a project is fully implemented or scaled up. Some projects that ended earlier still created important value by generating insights, strengthening networks, or exposing structural barriers in the wider innovation ecosystem.

- Cross-Project Operationalisation

Workshop 3 moved the focus to a more strategic, cross-project perspective. By comparing the six projects that piloted the Living Lab Assessment Method (LLAM) and looking at them side by side, we could reflect more broadly on the changing role of the City of Ghent in the local innovation ecosystem. The LLAM provided a shared language to talk about types of value that are usually not captured by standard innovation metrics, especially relational, organizational, and knowledge-based impacts.

This comparison showed which kinds of impact appeared most often across projects and where structural problems remained. As a result, the discussion shifted toward broader policy questions and pushed the City to think about its role as an enabler of experimentation and social innovation. A central question emerged: should the City mainly assess projects based on scalable, measurable innovation outcomes, or should it also recognize systemic value created by projects that do not reach full implementation?

The LLAM showed that systemic value can include stronger and broader networks, the creation and sharing of knowledge, better knowledge exchange across services and organizations, and greater resilience in the local social innovation landscape. These insights positioned the LLAM not only as an analytical framework, but also as a tool that supports policy learning and informs strategic decision-making within the municipal administration.

- Key insights/findings and adaptations for the LLAM

The use case contributed to LLAM development in the following ways:

- The LLAM showed that it can be used not only for evaluation, but also for reflection and learning. It helped teams clarify their assumptions, strengthen their Theory of Change, and adjust activities to improve value creation.

- The method captured a broad range of value, including knowledge development, stronger networks, better collaboration, and learning effects, even when projects did not reach full implementation.

- The LLAM provided a shared language and structure that made it easier to compare projects and to discuss types of value that are not covered by traditional metrics.

- The pilot confirmed that the LLAM can be applied in a new policy domain (employment and social inclusion), demonstrating its flexibility across different innovation contexts.

- Cross-project comparison supported strategic learning by showing where value accumulated across initiatives and where extra support or coordination was needed.

- The exercise encouraged deeper reflection on the role of local government in the innovation ecosystem, encouraging the City of Ghent to reconsider how it enables, supports, and evaluates experimental projects.

3.2. The LLAM and Its Components

As noted in the introduction, and based on the methodological development of the LLAM, the next sections present the main components of the method. Together, they form the foundation for the LLAM manual, which is also introduced at the beginning of the paper and offers a complete description of the LLAM in its final, consolidated form after application and validation in the use cases.

More specifically, the following sections describe the theoretical models that underpin the LLAM, the goals and purposes that guide its use, the value dimensions, explained in more detail, the Living Lab Value Fingerprint as a visual tool to express impact and value, and the practical steps needed to operationalize the LLAM in real projects, supported by its components and relevant templates.

3.2.1. Theoretical Foundations of the LLAM and Their Synergy

The LLAM starts from the idea that value in LLs is not created in a simple, linear way. Instead, it emerges over time through interactions between different actors. This process is strongly shaped by the local institutional, social, and political context in which a LL operates. Because of this, value creation in LLs cannot be captured well with fixed, predefined indicators or with a single evaluation at the end of a project. It requires an assessment approach that is sensitive to context, open to interpretation, and able to make causal relationships explicit.

To respond to these characteristics, the LLAM combines three complementary methodological approaches. First, it uses participatory assessment methods that actively involve stakeholders in the evaluation process [45,46]. Second, it draws on an empirically grounded value framework that supports a broad, holistic view of what counts as value in ULLs [44]. Third, it uses the Theory of Change (ToC) as a structured way to describe how activities are expected to lead to outcomes and impact [47,48].

These three approaches come from different research traditions, but they are combined in the LLAM because together they address the complex, multi-actor, and evolving nature of LL processes. When applied in practice, they create feedback loops within LLs: LLs become stronger by learning from impact assessment and adjusting their inputs and activities, while the LLAM itself is refined using data from real LL cases. This iterative relationship is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Shows how the Living Lab Assessment Method (LLAM) links participatory assessment, value dimensions of ULLs, and Theory of Change components to the inputs, activities, outputs, and outcomes of a living lab project through iterative feedback loops.

First, participatory assessment is a core foundation of the LLAM. In this approach, stakeholders are not only seen as sources of information, but as active contributors to reflection and evaluation [45,46]. Through stakeholder workshops and interviews, the LLAM gathers reflections that are rooted in practice and experience, including tacit knowledge and learning processes. These participatory methods are particularly useful for identifying less tangible forms of value, such as learning, trust, empowerment, and network development. However, participatory assessment by itself can be rather unstructured, which makes it harder to clearly identify value, track how it evolves over time, or compare results across projects. It is also important to note that participatory practices are already a core part of how LLs operate and are intrinsic to the LL concept itself [18].

The second foundation of the LLAM is a set of empirically derived value creation dimensions for ULLs [44] (Table 5). These dimensions are based on earlier research and provide a shared language that helps stakeholders reflect on value creation across different projects and contexts. They are not meant to be fixed indicators or strict performance measures. Instead, they act as guiding reference points for interpreting what happens in LL practice, for example in areas like knowledge creation, collaboration, agenda-setting, and experimentation, while still leaving room for context-specific meaning.

Table 5.

Overview of the seven value dimensions of Robaeyst et al. [44].

Finally, the Theory of Change forms the third foundation of the LLAM and adds analytical clarity by making expectations about change explicit. By linking inputs, activities, outputs, and outcomes, the Theory of Change helps stakeholders jointly describe how LL activities can lead to short-term and long-term value and impact. A key element of this process is to make underlying assumptions and contextual conditions explicit.

On their own, participatory assessment and Theory of Change each have limitations in Living Lab settings. Participatory approaches are strong at capturing lived experiences and new forms of value, but they often lack structure. Theory of Change, by contrast, gives a clear causal logic, but can become too abstract or technical if it is not closely tied to what stakeholders actually experience. These issues are especially important in LLs, where value creation is non-linear, develops over time, and involves many actors with different perspectives and time horizons. The LLAM addresses these limitations by combining participatory assessment and Theory of Change into one iterative process, supported by the empirically grounded value framework developed by Robaeyst et al. [44]. Stakeholder engagement through workshops is directly linked to building, testing, and refining the Theory of Change. The value dimensions help ground both reflection and causal reasoning in real LL practice. At the same time, insights from participatory assessment can lead to changes in the Theory of Change or to new ways of understanding how value is created.

3.2.2. Application Purposes of the LLAM

By combining the theoretical foundations described above with flexible use across different contexts and stages of an LL project, the LLAM is designed to serve multiple purposes. The LLAM can be used in a summative way to evaluate completed LLs, in a formative way to guide the development of new projects, in a reflective way to support collective learning, and as a communicative tool to translate outcomes for different audiences.

Table 6 summarizes these objectives and shows how the LLAM addresses each of them. Below, these application purposes and their underlying goals are explained in more detail.

Table 6.

Overview of goals and purposes of the LL Value Assessment Framework.

The main purpose of the LLAM is to support the systematic assessment of LLs during or after their implementation (summative use). Across all use cases, participants stressed the importance of capturing both visible and latent forms of value creation. LLs generate many types of value, but a large part of this value often remains invisible or is not fully recognized at policy or strategic levels. The first goal of the LLAM is therefore to make these “hidden” forms of value visible, so that the broader contributions of LLs can be better understood and acknowledged. Closely related to this is the challenge of how to define and measure such value in practice. A second goal of the LLAM is to deepen understanding of how both visible and invisible forms of value creation can be defined, measured, and supported with evidence. Participants noted that existing Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), which are mostly quantitative, do not capture the multidimensional nature of value creation in LLs. For this reason, the LLAM promotes a mixed-method approach that combines quantitative and qualitative indicators to enable a more comprehensive and meaningful assessment.

A second application purpose of the LLAM is to co-create LL projects together with local and involved stakeholders. The aim is not only to design projects that are relevant in their local context, but also to align goals and expectations before the LL starts. In this role, the framework acts as a goal-setting and alignment tool. It provides a structured set of value dimensions that help stakeholders discuss, prioritize, and negotiate desired outcomes from the beginning. This proactive use increases awareness of methodological choices and supports strategic alignment among project partners regarding how value should be created and for whom.

Third, beyond the project level, the LLAM is also meant to support holistic and long-term reflection on LLs as a governance and innovation approach. By comparing different use cases, the framework helps identify recurring patterns, success factors, and challenges. This reflective function supports policymakers and practitioners in drawing strategic insights, informing the design of future initiatives, and enabling learning across projects.

Fourth, the LLAM also has an important communicative function. By giving a clear and structured overview of different types of value creation, it makes it easier to communicate LL outcomes in a credible, transparent, and stakeholder-sensitive way. Because LLs are inherently multi-stakeholder settings, this clarity supports more focused and effective communication. It helps build shared understanding, improves collaboration, and strengthens the legitimacy of LL practices in broader policy and societal debates.

3.2.3. LLAM Impact/Value Dimensions

To translate the LLAM into concrete metrics for assessing value creation, we used the value framework developed by Robaeyst et al. to see how different value dimensions could be operationalized within specific projects. The seven value creation dimensions proposed by Robaeyst et al. [44] were consolidated into six key dimensions for the LLAM as described in use case 3.

The resulting framework is intentionally designed to stay adaptable to each LL context, so that every LL process can be assessed with context-specific metrics or forms of evidence. Because these impact and value dimensions are broad and multi-level, they also help LL practitioners look at value in a more comprehensive and holistic way.

To show this adaptability, we include a set of example measurement approaches that emerged from the second focus group in Use Case #3. In that workshop, LL lead users defined concrete ways to translate the LL impact and value dimensions into qualitative metrics and data collection strategies. Although these measurements may also be useful in other LL settings, but they are not meant to function as universal indicators.

- Skill capacity development

The LL stimulates a wide range of growth, development, and improvement that people experience in various aspects of their life and work. This development is supported and encouraged through participation in the experimental setting of a LL, where efforts are made to stimulate “T-shaped skills” [49], which are situated along both a horizontal axis of general skills that can be applied in various contexts and a vertical axis of domain-specific skills and knowledge.

- Example of measurement

The campus-based LL 3IDLabs is aimed at improving VUCA-skills (skills that help recognizing and understanding the complexities of a rapidly changing world). As a set of Horizontal skills, these can be measured through the application of a [questionnaire] among participating students. Although the framework explicitly challenges a counterfactual approach, participants still fall back to quantitative or statistical measures. This might be due to bias towards mechanical objectivity.

- Network capacity improvement

The LL helps create meaningful encounters within the innovation ecosystem in order to strengthen the network capacity of stakeholders. It does this by setting up facilities and organizing events that offer inclusive environments where diverse groups can meet and interact.in this way, the pilot project aims to build a culture of diversity and engagement among different partners. This requires not only actively promoting inclusivity when designing activities, but also creating physical spaces that make it easy and inviting for diverse participants to take part.

- Example of measurement

The Urban Living Lab of Collections of Ghent aimed to establish new collaborations within the Ghentian ecosystem among a diverse set of stakeholders. This was evaluated through specific use cases resulting directly from the project, such as instigating [new project proposals] and the introduction of a [yearly master thesis collaboration] between Ghent University and a Ghentian museum institution. In this context, the assessment and impact evaluation were predominantly qualitative in nature and not conducive to quantitative measurement. The wide variety of examples that provide empirical evidence for this improvement require an open-ended assessment.

- Knowledge capacity enhancement

The Living lab stimulates the development and sharing of new substantive as well as methodological knowledge, forming a dynamic process that offers innovative perspectives to participating stakeholders. This approach promotes mutual understanding and respect for multidisciplinarity and expertise. The shared and developed knowledge is validated and illustrated in an interdisciplinary setting, involving academics, industry, government, and citizens.

- Example of measurement

In the Labor pact project, a subproject was organized aimed at identifying and engaging isolated youth, also known as “Hikikomori” in Japanese, in the labor market. During the project, a new method was developed [generation of new knowledge] utilizing Reddit and Discord, which was then taught in 3 workshops to social workers [events on which newly generated knowledge is shared] in the city of Ghent who work with youth to help integrate them into the labor market.

- Instrumental capacity

The LL helps local ecosystem partners carry out and communicate their own mission and tasks. This means offering support to organizations and stakeholders in the ecosystem, for example by providing resources, advice, networking opportunities, or other forms of help. The main goal is to empower these partners to reach their own objectives. For instance, a civil organization that works with foreign-speaking newcomers may want to reach as many people in this group as possible. In that case, the LL can act as a facilitator by organizing new events and supporting the organization in achieving this goal.

- Example of measurement

The project Comon measured the instrumental capacity by conducting [20 interviews] with participating stakeholders. During these interviews, members of various participating organizations shared how the LL contributed to their own mission. These contributions were then documented in concrete [“impact stories”], serving as evidence for the added instrumental value of the project.

- Societal agenda-setting

The LL helps to communicate and make visible socially relevant issues or complex “wicked problems,” and aims to put them on the broader societal agenda. This process helps ensure that the central issue gets the attention it needs and increases understanding among other stakeholders who might not usually engage with these topics.

- Example of measurement

The Living Lab Comon measured this dimension by tracking the [number of public events] organized around the theme of “understandability in healthcare.” Additionally, they considered the number of [attendees reached] through these events and the frequency of [project mentions] on public radio, television, or in newspapers.

- Real solutions generation

The LL embraces a proactive approach to urban challenges within the local city context. In this dimension, the focus lies on finding concrete solutions for the complex societal issues related to the central theme of the Living Lab. These solutions are then applied and tested within a real-life environment to determine their added value within the realm of the central theme.

- Example of measurement

The CoGhent Living Lab created a series of artifacts that supported reuse and reinvention. In a funded program called the cocreation fund, small initiatives [got funding] to make use of this infrastructure. The LL also developed [first demonstrators] of several cutting edge data technologies and data standards. Furthermore, several [technology and artifact spin-offs & spin-outs] sprouted out of the living lab.

3.2.4. LLAM Tools and Operationalisation

As described in Section 3.2.1, Participative Assessment, Theory of Change and Value Framework form the core of the LLAM. However, these theories are still quite abstract. To make them more usable for practitioners working in real-world Living Lab contexts, further operationalization is needed. In this paper, we therefore introduce two practical tools that help to translate the LLAM into concrete, applicable guidance.

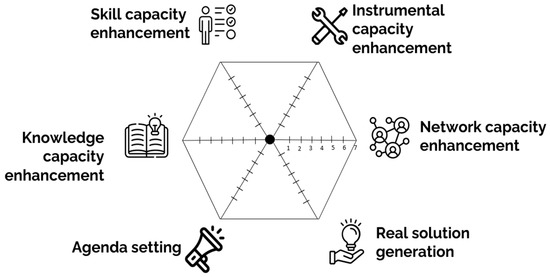

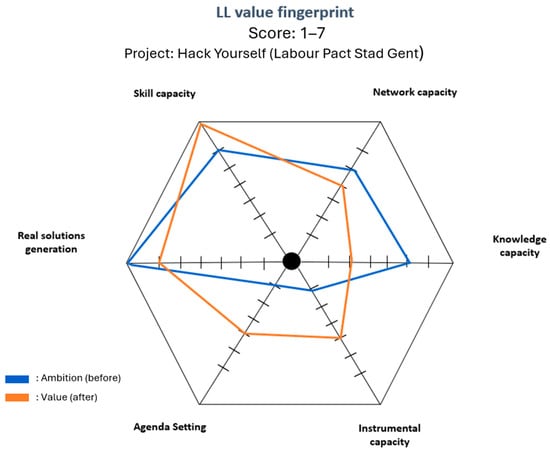

Central to this operationalization is the LL Value Fingerprint (Figure 2). This is a visual tool that supports dialogue and helps make the added value of LLs easier to discuss, compare, and understand for different stakeholder groups. It was developed in the City of Ghent Community of Practice (Use Case #3) and is used to guide structured conversations about impact and value throughout a LL project. The fingerprint shows each dimension of value creation defined in the LLAM and allows stakeholders to give a score between 1 and 7. These scores are based on shared perceptions formed through discussion. They are not statistical measures, but qualitative indicators that help clarify perspectives, surface differences, and build a shared understanding of what is important. A participatory approach is essential: involving both LL stakeholders and governmental actors reduces the risk of self-reporting bias and keeps the interpretation of value aligned with the project’s context. The 7-point scale was chosen because it offers enough nuance while still being easy to use. To support consistent scoring and address possible differences in interpretation, we include a suggested rubrics matrix in the Supplementary Materials of this paper. This matrix helps stakeholders apply and justify their scores. The fingerprint can be used before the start of a project to clarify ambitions, during implementation to monitor progress, and after completion to reflect on achieved value. This enables a longitudinal perspective that shows how expectations, experiences, and outcomes evolve over time. A final note concerns comparability. Stakeholders should be explicit about what can and cannot be compared within and between projects. Comparisons between Living Labs are possible but should be approached with caution, since the 1–7 scores are shaped by dialogue and local context. As a result, cross-Lab comparability is less relevant. In contrast, comparisons within the same Living Lab over time are more reliable and insightful, as they shed light on how value creation develops and enable more meaningful reflection on processes and outcomes. In Figure 3, we present a completed LL Value Fingerprint for the project “Hack Yourself”, which was one of the projects that got assessed in use case 4, Ghent Labour Pact.

Figure 2.

The LL Value Fingerprint, each dimension can be scored on a 1–7 scale that needs to be decided upon in a reflective and participatory manner.

Figure 3.

A completed LL Value Fingerprint for one Ghent Labour Pact project (Use Case 4). Comparing the initial and final fingerprints enabled the project to assess its impact and added value, and to reflect on differences between expected and realised outcomes.

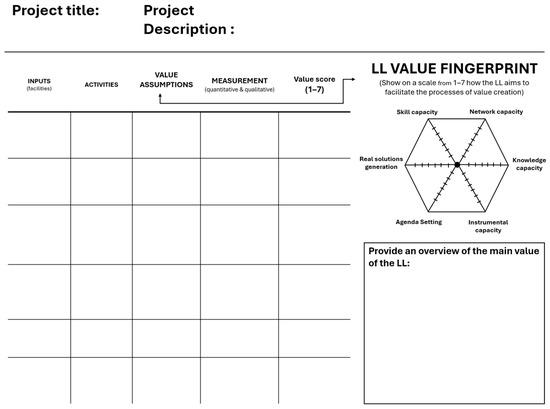

Complementing the LL Value Fingerprint, we developed the LLAM template (Figure 4) to provide a concrete, practical version of the method and to capture the essential elements of the Theory of Change (ToC). The template offers a clear structure for documenting the core components of a ToC: inputs, activities, value assumptions, and the measurements that empirically support these assumptions. Once the value assumptions have been defined, the LL Value Fingerprint can be completed. Together, the template and the fingerprint allow stakeholders to trace how the expected value is connected to planned activities and intended outcomes. The template also formalizes governance arrangements, such as roles, decision rights, frequency of interaction, and principles for data stewardship. This creates clarity about responsibilities and supports transparency throughout implementation. As the project progresses, the template functions as a living document. It is revisited during monitoring and consolidated in the final assessment, providing a traceable account of how value was conceptualized, pursued, and ultimately realized. By filling in the template and the fingerprint during and after the project, unintended outcomes can also be identified and included in the assessment of the Living Lab’s impact and value.

Figure 4.

The LLAM template that operationalizes the theory of change paradigm and the 6 value dimensions through the LL value fingerprint.

These tools can be applied in different phases of a LL project. In the following sections, we describe three key stages: initial, mid-project, and post-project. We explain how the LLAM can be used in each of them. Ideally, the LLAM is applied across all phases to create a coherent trajectory. In practice, however, it can also be used only in selected phases or in an iterative way, depending on the Living Lab’s needs, scale, and stage of development.

- Operational Phases of LLAM Application

- A. Initial Phase, before the LL project: Design, Alignment, and Baseline

Objectives:

- Develop a shared and testable Theory of Change.

- Align stakeholder expectations across the six value dimensions.

- Define governance, decision-making, and data stewardship practices.

- Establish a baseline for later comparison.

Core activities:

During a structured workshop, stakeholders complete the LLAM template and the LL Value Fingerprint. They identify inputs, activities, outputs, and intended outcomes, and make underlying assumptions explicit. The resulting template forms the initial reference point for monitoring and is revisited in the mid-project phase.

- B. Mid-Project Phase: Reflective Monitoring and Steering

Objectives:

- Assess progress relative to plans and the baseline.

- Evaluate emerging value creation.

- Revalidate the Theory of Change.

- Identify risks, bottlenecks, and contextual changes.

- Adjust goals, activities, or processes where needed.

- Strengthen alignment among stakeholders.

Core activities:

In a mid-term workshop, stakeholders review evidence from implementation and rescore the LL Value Fingerprint. Differences from the baseline highlight where value creation lags, exceeds expectations, or evolves differently. The Theory of Change is revisited and adjusted accordingly. All revisions are documented in the LLAM template to ensure continuity and transparency.

- C. Post-Project Phase: Assessment, Comparison, and Learning

Objectives:

- Consolidate and interpret all available evidence.

- Compare intended, evolving, and realised value creation.

- Identify success mechanisms, limitations, and failure points.

- Distinguish project-specific insights from system-level lessons.

- Produce communicable outputs for governance, funding, and dissemination.

Core activities:

Evidence is consolidated and a final Value Fingerprint is created and compared with earlier versions, showing the project’s value trajectories. A reflection workshop focuses on drawing actionable insights, identifying enabling and constraining factors, and clarifying which lessons can inform other projects or policies. For Living Labs in broader portfolios, LLAM also supports cross-case comparison. The process concludes with a communication package containing narrative summaries, visualisations, and an evidence annex tailored to key stakeholders.

4. Discussion

This paper departs from the observation that Living Labs (LLs), and in particular Urban Living Labs (ULLs), have become increasingly prominent instruments for addressing complex and “wicked” urban challenges [14,16,17]. They are frequently described as user-centred Open Innovation ecosystems that contribute to the development of more sustainable and inclusive cities [6,18,19,20]. Despite this growth, several authors highlight that the assessment of LLs and ULLs remains insufficiently developed [19,23,31,32,50]. Existing evaluations often rely on qualitative case descriptions or anecdotal evidence [3,23,51], which, while detailed, are difficult to generalize and offer limited guidance for practitioners who must present credible results to funders and policymakers. Technical or quantitative approaches, such as digital twins, promise more standardization [16,33,34], yet frequently focus on easily measurable outputs and tend to overlook relational, tacit or emergent forms of value creation.

In response to these challenges, this paper introduces the Living Lab Assessment Method (LLAM). The method integrates participatory assessment with stakeholders, a value framework capturing multiple types of impact [44], and a Theory of Change structure that makes causal assumptions explicit through context-specific indicators. In doing so, LLAM provides a balanced alternative between narrative case-based evaluation and indicator-driven monitoring. The method is grounded in three strands of LL and ULL scholarship. The first concerns the place-based and user-centred nature of LLs embedded within specific urban environments and governance configurations [10,16,17,18,19,20] This work underscores the contextual sensitivity of LL impact, a principle that LLAM operationalizes through participatory assessment and its Theory of Change logic. The second strand highlights the ongoing absence of robust and practically usable assessment frameworks [19,23,31,32,50]. LLAM addresses this gap by translating abstract notions of impact into a concrete, replicable process for daily LL practice. The third strand focuses on governance challenges that LLs frequently encounter, including short project lifespans, precarious funding and divergent stakeholder expectations [28,29,30]. LLAM responds by enabling stakeholders to articulate context-specific understandings of value and success, and by making these assumptions explicit through the LLAM template and the Value Fingerprint [16,17,30].

The LLAM aligns closely with existing assessment instruments while offering a clear broadening of their scope. Akasaka et al. [8], and likewise ENoLL [18], propose self-assessment tools that focus primarily on internal project management processes. While these approaches are valuable, they place less emphasis on value creation and do not systematically incorporate diverse stakeholder perspectives. LLAM, by contrast, positions intended outcomes at the centre of evaluation and integrates insights from multiple actors, including citizens and policymakers. In doing so, it introduces an outcome-oriented, multi-actor perspective into a field still largely shaped by internal process evaluations or single-case narratives [3,23,51]. In addition, positioning LLAM alongside digital-twin assessment strategies [16,33,34] reveals further complementarity. Earlier analyses have already highlighted the limitations of such strategies, yet this juxtaposition also uncovers an opportunity: LLAM can be used to identify relevant digital-twin metrics and adapt them incrementally throughout a Living Lab trajectory. In this way, technically oriented assessment frameworks can be enriched with qualitative, emergent, and context-specific parameters, leading to a more integrated and adaptive evaluation practice.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. The first concerns the context-sensitive nature of the LLAM. Because the method relies on close engagement with local practitioners, its effective use demands time, resources and a willingness among stakeholders to participate meaningfully.

A second limitation concerns the development context. Although LLAM has been tested across multiple use cases, most refinements emerged within a single urban ecosystem. As a result, its applicability cannot be presumed to translate directly to rural settings, industrial environments, or campus-based living labs. Moreover, because the method has so far been applied only in this specific context, validation in an international setting is still lacking.

A third limitation is the method’s reliance on stakeholder self-reporting, which introduces potential biases, including selective recall and the tendency to emphasize positive outcomes. While mitigation strategies such as rubrics matrices can improve consistency, they cannot fully eliminate these issues. Another mitigation strategy would be, the structural involvement of policy stakeholders within concrete LLAM workshops as a control mechanisms to prevent this kind of bias.

A fourth limitation concerns the absence of a systematic mechanism for a more long-term follow-up. Many LL outcomes manifest only after the formal project period ends, and workshop-based assessments alone cannot fully capture such delayed or systemic effects. The LLAM doesn’t assure a long term follow-up. This should be mitigated by the LL practitioners and managers that are responsible for assessing the added value of the project.

Lastly, the quality of facilitation plays a decisive role in the method’s effectiveness. LLAM depends on stakeholders being willing to reflect openly and on facilitators who are able to guide such reflection constructively. If this facilitation is lacking, tools like the Value Fingerprint risk being used as rigid scorecards rather than as qualitative instruments that support reflexive learning.

5. Conclusions

This paper reports the development and testing of the Living Lab Assessment Method (LLAM) as a structured, participatory, and context-sensitive approach for assessing value creation within Living Labs. Developed over five years through close collaboration between researchers, practitioners, and policymakers in Ghent, the method demonstrates how both tangible and intangible forms of value—such as skill development, network strengthening, agenda setting, and concrete solutions—can be made explicit and systematically assessed. The Living Lab Value Fingerprint provides a flexible visual instrument that supports alignment, monitoring, and evaluation throughout the project lifecycle, enabling reflection within single projects and, with appropriate caution, across multiple cases. Together, these elements show how LLAM offers a coherent framework for advancing understanding, practice, and governance of Living Labs.

For the academic community, the paper advances ongoing debates on the evaluation of Living Labs and Urban Living Labs by presenting LLAM as a practice-based method that combines methodological rigour with sensitivity to local context (use case 1, 2, 3 and 4). It responds to longstanding critiques concerning the anecdotal nature of LL evaluations and contributes to more robust foundations for impact assessment (use case 4). The consolidated framework of six operational value dimensions translates established theoretical insights into a usable structure for empirical analysis (use case 3). Furthermore, the Value Fingerprint supports systematic within- and cross-project learning (use case 4), while the documented co-development process illustrates how context-sensitive evaluation frameworks can be constructed in ways that remain connected to broader scholarly debates (use case 3).

For practitioners, LLAM offers a structured and reproducible approach that can be integrated into daily Living Lab operations (use case 1, 2, 3 and 4). It translates abstract discussions on value creation into practical methodological steps and helps articulate a broader range of impacts beyond immediate project outputs (use case 1, 2 and 4). By supporting systematic reflection throughout the project lifecycle, the method strengthens collaboration, facilitates shared understanding among partners, and enhances transparency in evaluation processes (use case 4). The Value Fingerprint further enables teams to compare expected, emerging, and realized forms of value, thereby improving learning and adaptation (use case 4).

For policymakers, LLAM provides a clearer foundation for accountability and strategic decision-making (use case 4). It highlights system-level impacts that extend beyond conventional performance indicators and offers structured value dimensions that make reporting more transparent (use case 2, 3 and 4). Its participatory design ensures alignment between policy goals and project-level activities, while its capacity for cross-project comparison supports portfolio-level analysis (use case 4). In doing so, the method helps policymakers understand how multiple initiatives collectively shape a city’s innovation and governance capacities.

Based upon the status of LL impact assessment literature, and the limitations of this study we define the following lines for future research.

First, future work should strengthen the empirical robustness of the LLAM by testing it across a broader and more diverse range of contexts, both within and beyond its original urban setting in the city of Ghent. Comparative application in rural, industrial, campus-based, and international Living Labs would help reveal which components of the method remain stable across settings and which require contextual adaptation. Extending validation to different governance structures, resource environments, and cultural contexts is essential for understanding the boundaries and transferability of the LLAM. We therefore aim to test the LLAM in at least three additional Living Lab projects situated in these varied (non-urban) and international environments.

Second, future research should explore how long-term reflection and learning can be more systematically integrated into the method. Combining LLAM with foresight approaches, such as scenario planning, trend analysis, and scenario exploration, offers a promising direction for identifying long-term impacts and underlying values that may not be immediately visible. Further examination is needed to determine how such approaches can be meaningfully embedded in Living Lab practice.

Third, there is a need to investigate how digital tools can support and enhance the LLAM without compromising its qualitative and reflective character. Developing and testing a digital interface that assists with data processing, visualization, and scoring could improve usability and consistency. Research should clarify how digital augmentation can strengthen methodological coherence while maintaining the method’s participatory ethos.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su18020779/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.R.; methodology, B.R.; validation, B.R. and T.V.N.; formal analysis, B.R.; investigation, B.R.; resources, T.V.N.; data curation, B.R.; writing—original draft preparation, B.R.; writing—review and editing, T.V.N., J.B., S.V.H., D.S. and B.B.; visualization, B.R., D.S. and B.B.; supervision, B.B.; project administration, T.V.N. and B.B.; funding acquisition, T.V.N. and B.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the fact that the study was conducted under Ghent University’s ethics waiver program and, as such, was not subject to mandatory additional review by the Ethics Review Committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The following public reports that support this study can be found through the following weblinks: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5fca0ec5d2462a1c4e231ac0/t/64f09ae781c39007c21e1f96/1693489901855/O4.4.1+-+Impact+assessment+report+%28includes+D4.4.1+and+D4.4.2%29+%281%29.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2025). https://comon.gent/sites/default/files/inline-files/Comon%20Eindrapport%20Eng.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2025). https://stad.gent/nl/werken-ondernemen/nieuws-evenementen/onderzoek-heeft-het-projectenfonds-van-het-gentse-arbeidspact-meerwaarde-gecreeerd (accessed on 15 December 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

All authors were involved in one or more of the use cases that served as empirical contexts for data collection underpinning this paper. Three of the four use cases conducted in the context of this research were funded by the City of Ghent. Ben Robaeyst, Dimitri Schuurman, and Bastiaan Baccarne are affiliated with the research group imec-MICT-UGent, whose research agenda includes the development and refinement of methodologies for impact assessment in innovation trajectories. This paper contributes to that research objective. Bastiaan Baccarne, Jeroen Bourgonjon, Stephanie Van Hove en Tom Van Nieuwenhove are a member of the COMOM advisory board, which constituted one of the use cases from which data were drawn for this study. Tom Van Nieuwenhove are employed by the City of Ghent, which provided funding for two of the use cases referenced in this paper. Stephanie Van Hove is part of CVSO De Krook, partly funded by Ghent University, Imec and the City of Ghent. All authors are affiliated with one or more organizations. An overview of these affiliations is provided in the affiliation section of the paper.

References

- Chesbrough, H.; Vanhaverbeke, W.; West, J.; Chesbrough, H.; Vanhaverbeke, W.; West, J. (Eds.) New Frontiers in Open Innovation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-0-19-968246-1. [Google Scholar]

- Angrisani, M.; Dell’Anno, D.; Hockaday, T. From Ecosystem to Community. Combining Entrepreneurship and University Engagement in an Open Innovation Perspective. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2022, 88, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.M.; Roijakkers, N.; Fini, R.; Mortara, L. Leveraging Open Innovation to Improve Society: Past Achievements and Future Trajectories. RD Manag. 2019, 49, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigliardi, B.; Ferraro, G.; Filippelli, S.; Galati, F. The Past, Present and Future of Open Innovation. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2020, 24, 1130–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderies, J.M.; Barfuss, W.; Donges, J.F.; Fetzer, I.; Heitzig, J.; Rockström, J. A Modeling Framework for World-Earth System Resilience: Exploring Social Inequality and Earth System Tipping Points. Environ. Res. Lett. 2023, 18, 095001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuurman, D. Bridging the Gap between Open and User Innovation?: Exploring the Value of Living Labs as a Means to Structure User Contribution and Manage Distributed Innovation. Ph.D. Thesis, Ghent University, Gent, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Iakovleva, T.; Bessant, J. FOSTERING USER INVOLVEMENT IN COLLABORATIVE INNOVATION SPACES: INSIGHTS FROM LIVING LABS. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2024, 28, 2450032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akasaka, F.; Mitake, Y.; Watanabe, K.; Tsetsui, Y.; Shimomura, Y. Development of a Self-Assessment Tool for the Effective Management of Living Labs. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2023, 70, 101783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhee, C.; Bancerz, M.; Mambrini-Doudet, M.; Chrétien, F.; Huyghe, C.; Gracia-Garza, J. The Defining Characteristics of Agroecosystem Living Labs. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.; Jones, R.; Karvonen, A.; Millard, L.; Wendler, J. Living Labs and Co-Production: University Campuses as Platforms for Sustainability Science. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 16, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuckrath, C.; Rosales-Carreón, J.; Worrell, E. Conceptualisation of Campus Living Labs for the Sustainability Transition: An Integrative Literature Review. Environ. Dev. 2025, 54, 101143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Følstad, A. Living labs for innovation and development of information and communication technology: A literature review. Electron. J. Virtual Organ. Netw. 2008, 10, 99. [Google Scholar]

- Molinari, M.; Anund Vogel, J.; Rolando, D.; Lundqvist, P. Using Living Labs to Tackle Innovation Bottlenecks: The KTH Live-In Lab Case Study. Appl. Energy 2023, 338, 120877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, R. Wicked Problems Revisited. Des. Stud. 2005, 26, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brons, A.; van der Gaast, K.; Awuh, H.; Jansma, J.E.; Segreto, C.; Wertheim-Heck, S. A Tale of Two Labs: Rethinking Urban Living Labs for Advancing Citizen Engagement in Food System Transformations. Cities 2022, 123, 103552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, A.; Ståhlbröst, A.; Habibipour, A. Transformative Thinking and Urban Living Labs in Planning Practice: A Critical Review and Ongoing Case Studies in Europe. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2021, 29, 1739–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholl, C.; de Kraker, J.; Dijk, M. Enhancing the Contribution of Urban Living Labs to Sustainability Transformations: Towards a Meta-Lab Approach. Urban Transform. 2022, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Living Lab Origins, Developments, and Future Perspectives—Knowledge Hub—ENoLL. Available online: https://knowledgehub.enoll.org/publication/living-lab-origins-developments-and-future-perspectives (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Steen, K.; van Bueren, E. The Defining Characteristics of Urban Living Labs. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2017, 7, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Wirth, T.; Fuenfschilling, L.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Coenen, L. Impacts of Urban Living Labs on Sustainability Transitions: Mechanisms and Strategies for Systemic Change through Experimentation. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2018, 27, 229–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leminen, S.; Westerlund, M.; Nyström, A.-G. Living Labs as Open-Innovation Networks. Innov. Netw. 2012, 2, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Veeckman, C.; Temmerman, L. Urban Living Labs and Citizen Science: From Innovation and Science towards Policy Impacts. Sustainability 2021, 13, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voytenko, Y.; McCormick, K.; Evans, J.; Schliwa, G. Urban Living Labs for Sustainability and Low Carbon Cities in Europe: Towards a Research Agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 123, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, W.; Levinthal, D. Absorptive Capacity: A New Perspective on Learning and Innovation. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, E.; Stappers, P.J. Co-Creation and the New Landscapes of Design. CoDesign 2008, 4, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenger, M.; Bekkers, V. Creating Connective Capacities in Public Governance: Challenges and Contributions. In Beyond Fragmentation and Interconnectivity; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ansell, C.; Torfing, J. (Eds.) Public Innovation Through Collaboration and Design; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-0-203-79595-8. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.; Leminen, S.; Westerlund, M. A Systematic Review of Living Lab Literature. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 213, 976–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascó, M. Living Labs: Implementing Open Innovation in the Public Sector. Gov. Inf. Q. 2017, 34, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersoy, A.; Bueren, E. van Challenges of Urban Living Labs towards the Future of Local Innovation. Urban Plan. 2020, 5, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballon, P.; Van Hoed, M.; Schuurman, D. The Effectiveness of Involving Users in Digital Innovation: Measuring the Impact of Living Labs. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 1201–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paskaleva, K.; Cooper, I. Are Living Labs Effective? Exploring the Evidence. Technovation 2021, 106, 102311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aniche, L.Q.; Edelenbos, J.; Gianoli, A.; Enseñado, E.M.; Makousiari, E.; DeLosRíos-White, M.I.; Caruso, R.; Zalokar, S. Boosting Co-Creation of Nature-based Solutions within Living Labs: Interrelating Enablers Using Interpretive Structural Modelling. Environ. Sci. Policy 2024, 161, 103873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]