Abstract

Supercritical CO2 modifies deep coal reservoirs through the coupled effects of adsorption-induced deformation and geochemical dissolution. CO2 adsorption causes coal matrix swelling and facilitates micro-fracture propagation, while CO2–water reactions generate weakly acidic fluids that dissolve minerals such as calcite and kaolinite. These synergistic processes remove pore fillings, enlarge flow channels, and generate new dissolution pores, thereby increasing the total pore volume while making the pore–fracture network more heterogeneous and structurally complex. Such reservoir restructuring provides the intrinsic basis for CO2 injectivity and subsequent CH4 displacement. Both adsorption capacity and volumetric strain exhibit Langmuir-type growth characteristics, and permeability evolution follows a three-stage pattern—rapid decline, slow attenuation, and gradual rebound. A negative exponential relationship between permeability and volumetric strain reveals the competing roles of adsorption swelling, mineral dissolution, and stress redistribution. Swelling dominates early permeability reduction at low pressures, whereas fracture reactivation and dissolution progressively alleviate flow blockage at higher pressures, enabling partial permeability recovery. Injection pressure is identified as the key parameter governing CO2 migration, permeability evolution, sweep efficiency, and the CO2-ECBM enhancement effect. Higher pressures accelerate CO2 adsorption, diffusion, and sweep expansion, strengthening competitive adsorption and improving methane recovery and CO2 storage. However, excessively high pressures enlarge the permeability-reduction zone and may induce formation instability, while insufficient pressures restrict the effective sweep volume. An optimal injection-pressure window is therefore essential to balance injectivity, sweep performance, and long-term storage integrity. Importantly, the enhanced methane production and permanent CO2 storage achieved in this study contribute directly to greenhouse gas reduction and improved sustainability of subsurface energy systems. The multi-field coupling insights also support the development of low-carbon, environmentally responsible CO2-ECBM strategies aligned with global sustainable energy and climate-mitigation goals. The integrated experimental–numerical framework provides quantitative insight into the coupled adsorption–deformation–flow–geochemistry processes in deep coal seams. These findings form a scientific basis for designing safe and efficient CO2-ECBM injection strategies and support future demonstration projects in heterogeneous deep coal reservoirs.

1. Introduction

The global response to climate change and the advancement of carbon-neutral strategies pose an urgent challenge for the energy sector: achieving coordinated progress in greenhouse gas emission reduction and clean energy production [1,2,3,4]. Among various mitigation technologies, CO2 geological sequestration is recognized as a key pathway for low-carbon utilization of fossil energy [5,6,7,8]. Within this framework, CO2-ECBM (enhanced coalbed methane recovery using CO2 injection) has attracted growing attention. CO2-ECBM simultaneously enables geological storage of CO2 and improved extraction of CBM (coalbed methane) through the competitive adsorption of CO2 and CH4 on coal surfaces [9,10,11,12,13]. Numerous international pilot tests have demonstrated that CO2 injection can significantly enhance methane recovery, especially in low-permeability or depleted CBM reservoirs [14,15].

However, whether and to what extent CO2 injection can enhance recovery in China’s deep coal reservoirs remains insufficiently understood. In the eastern Ordos Basin, although the Yanchuannan and Jinzhong blocks contain abundant CBM resources, field data indicate that single-well production typically ranges only from 500–1500 m3/d, and nearly one-third of wells exhibit persistently low productivity [16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. These challenges underscore the need for advanced stimulation technologies such as CO2-ECBM. Yet, large-scale deployment is hindered by limited understanding of deep-reservoir microstructural evolution, multi-phase/multi-field coupling mechanisms, and engineering parameter optimization [23,24,25,26,27,28].

Previous studies have provided valuable insights, but key scientific questions governing CO2-ECBM in deep coal seams remain unresolved. These include the following:

- (1)

- How supercritical CO2 reshapes the pore–fracture system through coupled adsorption-induced deformation and geochemical dissolution;

- (2)

- How adsorption swelling, stress redistribution, and mineral dissolution jointly control permeability evolution and govern long-term injectivity;

- (3)

- How injection pressure and other engineering parameters affect methane displacement efficiency and the stability of CO2 storage. A clear understanding of these mechanisms is essential for establishing a scientific basis for CO2 injection strategies in deep, heterogeneous coal reservoirs.

To address these gaps, this study integrates physical simulation experiments with multi-field coupled numerical modeling to systematically reveal the fundamental mechanisms of CO2-ECBM. Laboratory experiments quantify the evolution of pore–fracture structures under supercritical CO2 exposure, adsorption-induced stress–strain responses, and permeability variations under reservoir-relevant conditions. Numerical simulations further elucidate the coupled impacts of adsorption swelling, mineral dissolution, stress redistribution, and multiphase flow on reservoir permeability, CO2 injectivity, and CH4 displacement efficiency. Based on these experimental and numerical results, the enhancement potential of CO2 injection is evaluated, and optimal engineering parameter ranges for deep-reservoir CO2-ECBM are identified.

Overall, this research establishes a comprehensive mechanistic and quantitative assessment framework for CO2-ECBM in China’s deep coal seams. The findings provide essential theoretical and technical support for feasibility evaluation, engineering design, and future demonstration projects, offering significant implications for improving CBM development efficiency and advancing national carbon-reduction goals.

2. Study Area Overview

The Yanchuannan and Jinzhong CBM blocks are situated within the tectonic transition zone on the eastern margin of the Ordos Basin, spanning the border region of southern Yan’an City, Shaanxi Province, and Jinzhong City, Shanxi Province. This area is characterized by the typical hilly–gully topography of the loess plateau. The regional geology is dominated by gently dipping monoclinal structures, with strong reservoir heterogeneity, significant variations in coal seam burial depth, intense surface erosion, and highly fragmented terrain, all of which significantly influence CBM accumulation and development. Geographically, the Jinzhong block is concentrated in the central part of the Jinzhong Basin, featuring complex hydrogeological conditions. The experimental and numerical parameters used in this study were determined based on representative geological conditions of the Yanchuannan and Jinzhong CBM blocks in the eastern Ordos Basin. The target coal seams occur at depths of approximately 1280–2200 m. Correspondingly, the in situ temperature ranges from 33.5–44.3 °C, and the reservoir pressure is typically 13–16 MPa, with horizontal stresses generally between 12–40 MPa. The coal reservoirs exhibit strong heterogeneity, characterized by well-developed but variably connected face and butt cleats, porosity typically within 0.5–4%, and permeability commonly ranging from 0.001 to 0.5 mD. The regional stress field is dominated by high horizontal stresses, which strongly control cleat openness and the degree of coal matrix deformation during CO2 injection. Formation water types include NaHCO3- and CaCl2-dominated waters, with salinities between 2700 and 49,513 mg/L, as measured in representative water samples from the Yanchuannan and Jinzhong blocks. These geological characteristics serve as the basis for selecting the experimental temperature–pressure conditions and for defining key parameters in the multi-field coupled numerical simulations.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Experimental Study

The coal samples used in this study were obtained from standard coring and sample preparation procedures provided by the mining company/laboratory. All samples were collected using conventional dry coring without the use of liquid-based coring fluids, avoiding potential alteration of pore structures caused by drilling mud invasion or fluid-induced swelling. After coring, the samples were immediately sealed, transported, and stored under controlled laboratory conditions to minimize moisture exchange and structural disturbance. Prior to testing, the samples were trimmed into standard core plugs using a low-speed diamond cutting system (made in China University of Mining and Technology) to preserve the original pore–fracture system as much as possible.

3.1.1. Characterization of Pore–Fracture Structure Evolution Under Supercritical CO2

- (1)

- Experimental Samples and Geological Background

The coal samples used in this study were collected from the Jining (JN 1) and Zuoquan (ZQ 3) coal mines. The JN 1 mine is located in the southern margin of the Yanchuannan CBM block, whereas the ZQ 3 sample originates from the eastern section of the Jinzhong block. These two sites were selected because they are representative of the geological conditions in the key CBM development blocks of the Qinshui Basin, exhibiting typical variations in burial depth, coal rank, and reservoir stress conditions. The combination of JN 1 and ZQ 3 allows for a more comprehensive evaluation of CO2–ECBM mechanisms under contrasting but regionally relevant geological settings (Figure 1). The experimental conditions were determined based on representative in situ parameters of the two study blocks. The Yanchuannan coal seam occurs at depths of approximately 1200–1350 m, with in situ temperatures of 33.5–42 °C, reservoir pressures of 12–15 MPa, and horizontal stresses ranging from 12 to 40 MPa. The Jinzhong block contains deeper coal seams at 1600–2200 m, where temperatures range from 40–45 °C, reservoir pressures range from 15–18 MPa, and the horizontal stress field remains dominant. These unified geological parameters provide a consistent basis for determining the subsequent experimental temperature-pressure settings.

Figure 1.

Sample photo ((a) JN-1 of No.2 coal in the Jining Coal Mine and the (b) Zuo Quan Coal Mine ZQ-3) (The labels for the specimen strip and specimen number in the diagram are in Chinese; other fields are left blank).

- (2)

- Experimental Scheme and Reaction Apparatus

Reactions were conducted for 14 days under formation-representative conditions: 38 °C and 15 MPa for JN-1, and 44.3 °C and 13.6 MPa for ZQ-3 (Table 1). A high-pressure CO2–water–rock reaction system was used to precisely control temperature, pressure, and fluid environment, enabling simulation of long-term CO2–coal geochemical interactions.

Table 1.

Supercritical CO2–Water–Coal Reaction Experimental Parameter Settings.

- (3)

- Multi-Method Characterization System

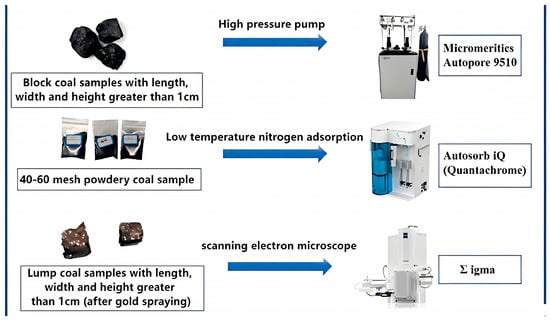

A combined analytical approach was adopted, including mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), low-temperature gas adsorption (N2/CO2), and low-field NMR (Figure 2). MIP quantified the macropore volume and size distribution; SEM captured fracture development and mineral dissolution; gas adsorption characterized pore types following the IUPAC classification; and NMR provided full-scale pore size distributions and heterogeneity assessments through multifractal analysis.

Figure 2.

Experimental method for characterization of pore fracture structure before and after reaction.

3.1.2. Stress–Strain and Permeability Response to Supercritical CO2 Injection

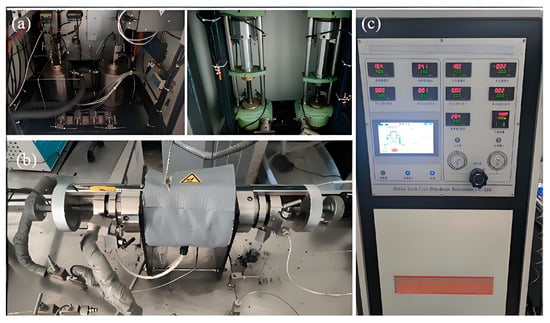

This experiment simulated CO2-driven methane displacement under deep reservoir constraints. A dedicated temperature-pressure-controlled system (Figure 3) was utilized to precisely regulate the thermal and confining conditions required for the experiments. Isothermal adsorption tests quantified CO2 adsorption behavior, while adsorption–volumetric strain tests monitored coal matrix deformation. Permeability tests were conducted under constant confining pressure with injection pressures increasing from 2 to 10 MPa. The combined results revealed the coupled effects of effective stress and CO2-induced adsorption swelling on coal deformation and permeability evolution, providing a mechanistic basis for understanding coal reservoir responses during CO2 injection.

Figure 3.

Core Equipment (the equipment was independently developed by China University of Mining and Technology, Xuzhou, Jiangsu Province, China) ((a) Reference Cylinder and Ring Pressure Booster (b) Fixture System (c) Temperature and Pressure Control System).

3.2. Multi-Field Coupled Numerical Simulation

Based on previous experimental findings, this study developed a multi-field coupled mathematical model for CO2-ECBM to systematically evaluate CO2 injectivity in deep coal reservoirs and its enhancing effect on methane production. The model incorporates the interactions among the seepage, stress, and temperature fields and is implemented using the COMSOL Multiphysics 6.2 numerical simulation platform. The following fundamental assumptions were adopted during model construction: CO2 and CH4 undergo competitive adsorption–desorption within the coal matrix micropores; gas diffusion in the matrix follows Fick’s law, while fluid flow in the fracture system conforms to Darcy’s law; and the deformation of the coal skeleton is simplified as linear elastic to describe the mechanical response.

The established model forms a fully coupled multi-physics system describing the CO2-ECBM process through a set of governing equations and numerical methods [29,30,31,32]. Coupling among the physical fields is achieved through stress-seepage-temperature interactions. For numerical implementation, the simulation first initializes fluid properties, relative permeability curves, and the system of partial differential equations. The seepage governing equations are then discretized and solved using a backward differentiation formula, yielding the pressure, saturation, velocity, and adsorbed-phase distributions. Within each time step, porosity and permeability are dynamically updated, and iterative calculations are performed to ensure convergence until the entire simulation period is completed.

- (1)

- Matrix system gas flow equations, describing the diffusion process of gas from the matrix to the fractures:where VL,i and PL,i represent the Langmuir volume and Langmuir pressure constants of gas component i (e.g., i = 1 for CH4 and i = 2 for CO2) corresponding, respectively, to the maximum adsorption capacity and the pressure at half-maximum adsorption; Pm,i is the matrix-phase partial pressure of gas component i; Ps is the gas pressure in the cleat system, which provides the diffusion driving force; Pfgi denotes the equilibrium free-gas pressure of component i; ρ is the bulk density of the coal matrix (kg·m−3); Mg,i is the molar mass of gas component i; R is the universal gas constant; T is the thermodynamic temperature (K); ϕm denotes the matrix porosity; and τi is the diffusion time constant of gas component I in the coal matrix.

- (2)

- Fracture system fluid migration equations, describing gas-water two-phase flow based on Darcy’s law:where Sg and SW are the gas-phase and water-phase saturations in the cleat system (dimensionless); ϕf is the cleat porosity (dimensionless, ratio of cleat volume to total coal volume); bk is a correction parameter associated with coal adsorption/desorption behavior; krg and krw are the gas-phase and water-phase relative permeabilities (dimensionless, correcting flow capacity of each phase in cleats), respectively; k is the absolute permeability of the cleat system (mD); μg,i and μw are the dynamic viscosities of gas component and water (Pa·s); ρw is the density of water (kg·m−3); Pf,w is the water-phase pressure in the cleat system; Q is the source sink term for the water phase (kg·m−3·s−1).

- (3)

- Coal rock stress field control equation, based on linear elastic theory and considering adsorption-induced swelling strain:where G denotes the shear modulus of coal (Pa); ui,jj represents the second-order spatial derivative of the displacement component ui (subscripts i j indicate coordinate components); ν is Poisson’s ratio (dimensionless); Fi is the body force component (N·m−3); αm and αf are the dimensionless effective stress coefficients for the matrix and cleat system, respectively; K is the bulk modulus of coal (Pa); Ti is the spatial derivative of temperature and εS,i is the initial strain component (dimensionless).

- (4)

- Temperature field governing equation, describing energy conservation in the reservoir:where (ρCP)eff is the effective volumetric heat capacity of the coal-gas-water system (J·(m3·K)−1); λeff is the effective thermal conductivity of the system (W·(m·K)−1); αT is the thermal expansion coefficient of coal (K−1); qi is the mole fraction of gas component i; ρs is the coal matrix density(kg·m−3);

- (5)

- Porosity and permeability dynamic evolution equations, characterizing the influence of effective stress and adsorption swelling effects on reservoir properties:where S0 is the matrix total strain term (defined in the third equation, dimensionless); ΔεV is the volumetric strain variation (dimensionless); Kf is the bulk modulus of the cleat system (Pa); Ks is the bulk modulus of the coal matrix.

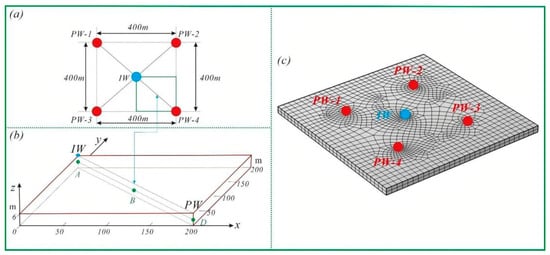

For geometric construction and mesh generation, a representative well pattern consisting of one central injection well and four surrounding production wells was established. The computational domain is defined as 200 m × 200 m × 3 m, with a uniform wellbore diameter of 0.2 m. Three-dimensional meshing was conducted using a swept-mesh strategy. For subsequent analysis, the model diagonal AD and a representative observation point B were selected as key locations for extracting and discussing simulation results (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Geometric model and mesh generation. ((a) Reference Cylinder and Ring Pressure Booster (b) Fixture System (c) Temperature and Pressure Control System).

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Evolution of Coal Reservoir Pore–Fracture Structure Under Supercritical CO2

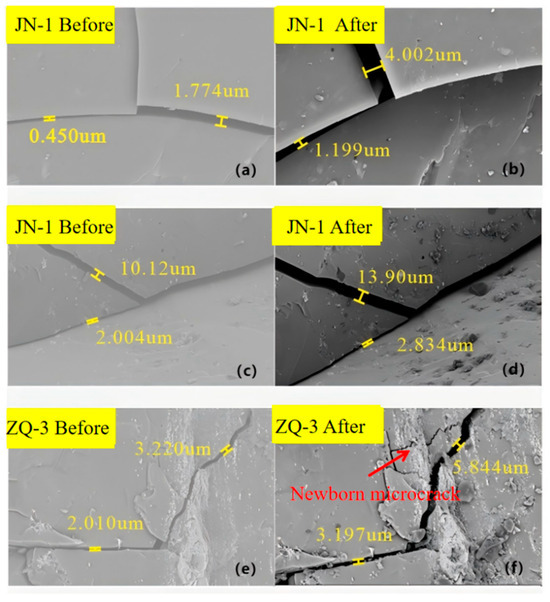

Figure 5 presents representative SEM images of the JN-1 and ZQ-3 samples before (left column) and after (right column) the CO2–water–rock interaction, clearly illustrating the microstructural evolution induced by the reaction. Prior to exposure, the JN-1 sample exhibits a relatively compact and intact microstructure. Pre-existing pores and fractures display limited apertures, with measured widths ranging from submicron to micrometer scale (approximately 0.450–10.12 μm; Figure 5a,c), indicating a comparatively tight pore–fracture system. After interaction, the JN-1 sample shows pronounced fracture widening and pore enlargement. Several fractures expand markedly (e.g., from ~0.450–1.774 μm to ~1.199–4.002 μm in Figure 5a,b, and from ~2.004–10.12 μm to ~2.834–13.90 μm in Figure 5c,d), while fracture boundaries become noticeably rougher and more irregular. These morphological changes suggest that mineral dissolution along fracture surfaces and structural interfaces plays a dominant role, promoting pore-space reconstruction and enhancing connectivity among adjacent pores and fractures.

Figure 5.

Comparison of microstructure of coal samples before and after reaction. ((a) Microcrack morphology of JN-1 coal sample before reaction (local view I); (b) Microcrack morphology of JN-1 coal sample after reaction (local view I); (c) Microcrack morphology of JN-1 coal sample before reaction (local view II); (d) Microcrack morphology of JN-1 coal sample after reaction (local view II); (e) Microstructure of ZQ-3 coal sample before reaction; (f) Microstructure of ZQ-3 coal sample after reaction with newly generated microcracks.).

A similar but more heterogeneous response is observed in the ZQ-3 sample. Before reaction, ZQ-3 contains only a few isolated microfractures with relatively small apertures (approximately 2.010–3.220 μm; Figure 5e), and the matrix remains comparatively intact. Following CO2 exposure, these pre-existing fractures are significantly enlarged (up to ~3.197–5.844 μm; Figure 5e,f), and, more importantly, newborn microcracks emerge and propagate along mechanically weak zones within the matrix. The development of these new fractures reflects a coupled effect of chemical dissolution and stress redistribution, whereby CO2–water–rock reactions weaken mineral bonds and facilitate microcrack initiation and coalescence. Overall, the SEM observations demonstrate that supercritical CO2 interaction promotes both pore development and fracture connectivity in coal, although the extent of alteration varies spatially. Some pores and fractures exhibit only limited enlargement, reflecting the intrinsic heterogeneity of the coal matrix. Locally rigid or well-cemented domains may resist chemical attack, while adsorption-induced coal swelling can partially counteract dissolution-driven fracture opening, thereby constraining microstructural modification. These SEM-based observations are consistent with trends identified by MIP analysis, collectively confirming the non-uniform yet systematic impact of CO2–water–rock interactions on coal microstructures.

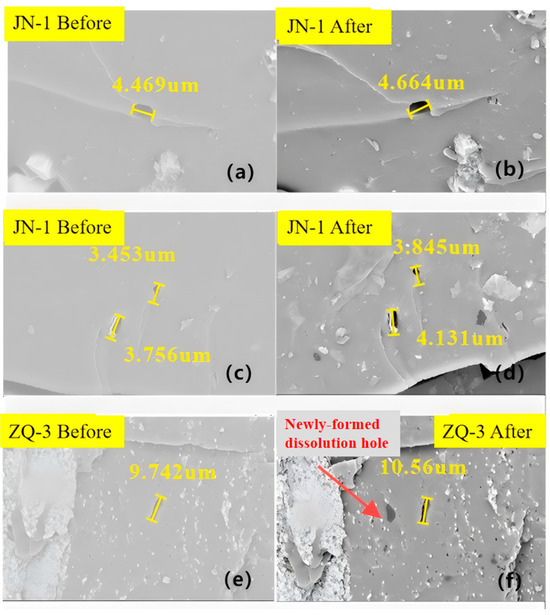

Further SEM observations (Figure 6) indicate that CO2 not only drives fracture development but also reshapes pore morphology: secondary gas pores expand, dissolution features appear, and mineral fillings along fracture walls are significantly reduced. The formation of dissolution pores-particularly prominent in sample ZQ-3-further diversifies pore types and strengthens three-dimensional network connectivity.

Figure 6.

Comparison of microstructure and dissolution pores of coal samples before and after reaction. ((a) Microstructure and dissolution pores of JN-1 coal sample before reaction (local view I); (b) Microstructure and dissolution pores of JN-1 coal sample after reaction (local view I); (c) Microstructure and dissolution pores of JN-1 coal sample before reaction (local view II); (d) Microstructure and dissolution pores of JN-1 coal sample after reaction (local view II); (e) Microstructure and dissolution pores of ZQ-3 coal sample before reaction; (f) Microstructure and dissolution pores of ZQ-3 coal sample after reaction showing newly formed dissolution holes.).

The quantitative data from high-pressure mercury intrusion experiments and the qualitative characterization from SEM form a perfect closed loop of the study: the total pore volume of the JN-1 coal sample increased from 0.1717 mL/g before the reaction to 0.1819 mL/g after the reaction, an increase of 5.94%, quantitatively confirming the pore space expansion effect of CO2 on coal. This forms a qualitative-quantitative cross-verification with the fracture expansion and pore enlargement observed by SEM, collectively revealing the significant potential of CO2 for pore expansion and permeability enhancement in coal reservoirs. It is noteworthy that the chemical reaction of the CO2–water–coal three-phase system is the key mechanism driving the aforementioned microstructural modifications.

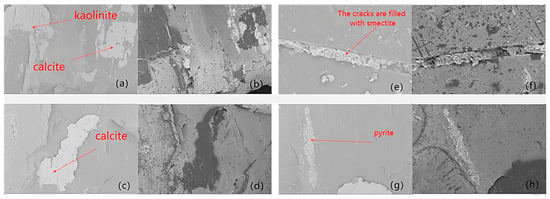

SEM and mineralogical analysis results (Figure 7) provide direct evidence of mineralogical alterations during the CO2–water–rock reaction. Specifically, Figure 7a,b show that both calcite and kaolinite experienced noticeable dissolution, with their particle boundaries becoming blurred and micro-surface roughness significantly increased. Figure 7c,d further confirm the extensive dissolution of calcite, where large calcite aggregates display irregular edges and dissolution pits, indicating active chemical erosion by acidic CO2-bearing fluids. In Figure 7e,f, pre-existing microcracks are completely filled with smectite, illustrating secondary mineral precipitation during the reaction. The presence of smectite infilling suggests ion migration and transformation of aluminosilicate minerals, which may locally reduce permeability. Figure 7g,h present the distribution of pyrite, where its morphology remains largely intact, implying that pyrite is relatively stable under the experimental conditions and undergoes minimal reaction compared with carbonate and aluminosilicate minerals. Overall, although the macroscopic dimensions of some mineral grains did not change markedly, their micro-surfaces became rougher and dissolution features became more pronounced, creating more pore space and enhancing micro-fracture development. Supercritical CO2 dissolves soluble minerals within pores and fractures, widens existing flow paths, and-through adsorption-induced coal matrix swelling-redistributes internal stresses to promote the opening of primary fractures and the generation of new ones. These coupled chemical and mechanical effects jointly optimize the coal’s pore–fracture network structure.

Figure 7.

Changes in mineral composition after reaction. ((a) Distribution of kaolinite and calcite before reaction; (b) Mineralogical features after reaction corresponding to panel (a); (c) Calcite occurrence before reaction; (d) Calcite morphology after reaction corresponding to panel (c); (e) Microcrack characteristics before reaction; (f) Microcracks filled with smectite after reaction; (g) Pyrite occurrence after reaction; (h) Pyrite-related microstructural features after reaction (magnified view).).

The differences in the microscopic responses of the different coal samples (JN-1 and ZQ-3) are inferred to be related to the coal’s intrinsic properties, such as mineral composition, organic matter content, and initial pore structure characteristics. The more pronounced development of new fractures and dissolution pores in the ZQ-3 coal sample may originate from its higher content of soluble minerals or more developed initial weak interfaces. This also suggests that the microstructural modification effect of CO2 on coal exhibits a coal-type dependency. The structural improvements at the micro-scale not only provide more abundant storage space for the transformation of CH4 from the adsorbed state to the free state but also, by enhancing the connectivity of the pore–fracture network, reduce the resistance to fluid migration. This provides a fundamental microscopic basis for the optimization of macroscopic seepage efficiency and the effective sequestration of CO2.

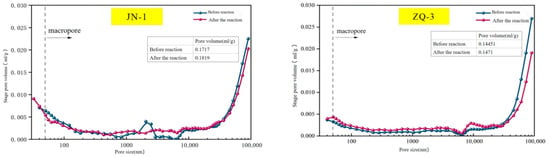

Mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP) results demonstrate that the supercritical CO2–water–coal reaction significantly influenced the pore volume and pore size distribution of the coal samples. Specifically, the total pore volume of the JN-1 sample increased from 0.1717 mL/g before the reaction to 0.1819 mL/g after treatment, while that of the ZQ-3 sample also rose from 0.1445 mL/g to 0.1471 mL/g, indicating an overall expansion of the pore space induced by the reaction process (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Total pore volume reaction change in the JN-1 coal sample and the ZQ-3 coal sample.

Further analysis of the mercury intrusion curves reveals a dual effect of the supercritical CO2–water–coal interaction: for macropores with diameters less than 40 μm, pore volume increased noticeably due to the dissolution of pore-filling minerals. In contrast, for macropores larger than 40 μm, a reduction in pore volume was observed, which is primarily attributed to pore blockage caused by mineral precipitation and the formation of secondary minerals.

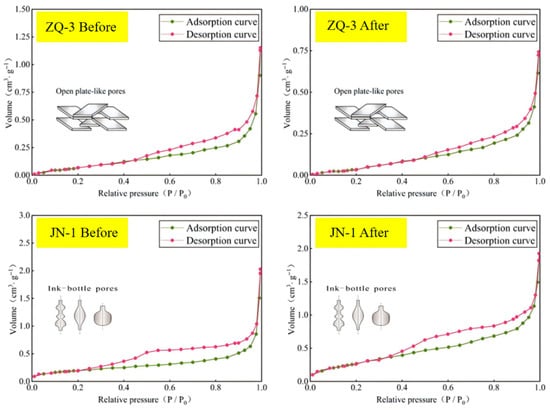

Low-temperature gas adsorption analysis revealed no significant alteration in the pore structure morphology of the coal samples following the supercritical CO2–water–coal reaction. According to the IUPAC pore classification criteria, the adsorption–desorption isotherms of the ZQ-3 sample exhibited characteristics typical of slit-shaped pores, while the JN-1 sample displayed a pattern consistent with ink-bottle shaped pores. The morphology of the adsorption–desorption curves remained largely consistent before and after the reaction for both samples, indicating that under the experimental conditions applied, the supercritical CO2–water–coal interaction did not induce a noticeable change in pore geometry, and the pore structure morphology remained overall stable (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Changes in pore structure and morphology of coal samples.

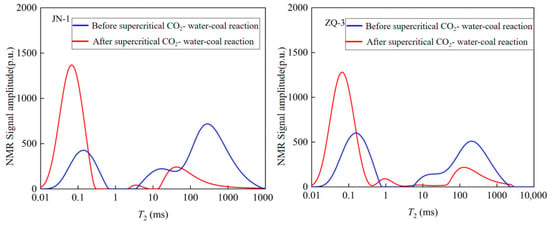

Low-field NMR T2 spectrum analysis further revealed a weakening signal in the micropore region (0.1–10 ms), indicating an increase in micropore size; and an enhanced signal in the seepage pore region (>10 ms), reflecting a change in the proportion of seepage pores (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Changes in total pore size distribution after coal sample reaction.

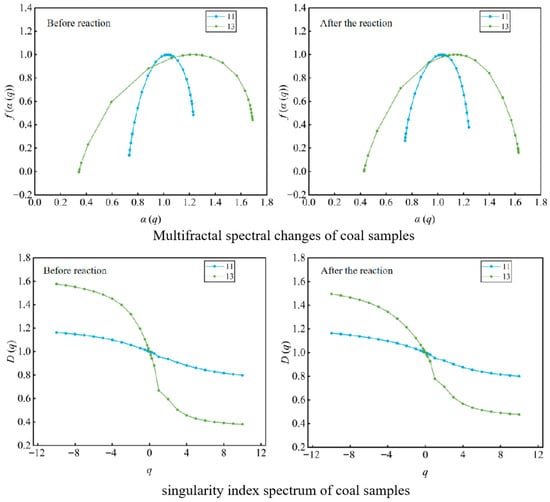

After reaction, the multifractal spectrum of the coal samples showed increased spectrum width, increased singularity index, and worsened spectrum symmetry, comprehensively reflecting a significant enhancement in the heterogeneity and complexity of the coal reservoir’s pore–fracture structure. The heterogeneity change was more pronounced in the low-dimensionality region (micropores) (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Changes in Multifractal Spectrum and Singularity Index Spectrum of Coal Samples.

The experimental results demonstrate that coal modification under supercritical CO2 is governed by two coupled mechanisms: adsorption-induced swelling and CO2–water–coal geochemical dissolution. Adsorption-induced swelling primarily affects the coal matrix, redistributing internal stresses and promoting the propagation of existing micro-fractures as well as the initiation of new ones, especially along mineral–organic interfaces. At the same time, supercritical CO2 exhibits strong penetration capability, allowing it to rapidly access micro- and nano-scale pores, which increases adsorption efficiency and enlarges the reaction contact area, thereby accelerating microstructural alteration. In parallel, dissolution reactions occur preferentially in mineral-rich weak zones, where calcite, kaolinite, and other soluble minerals are removed, transforming isolated pores into interconnected channels. This effect is particularly pronounced in coal types with higher carbonate or clay mineral content, such as the ZQ-3 sample. The synergistic action of swelling and dissolution produces an “internal expansion + external cleaning” effect: the coal matrix expands internally while mineral dissolution cleans and enlarges pore–throat pathways, collectively increasing pore volume, enhancing connectivity, and reducing flow resistance. However, this modification is not uniformly distributed. The intensified heterogeneity and asymmetrical fracture development caused by these processes may generate preferential flow channels, leading to uneven CO2 sweep, early gas breakthrough, and localized instability of CO2 storage. Therefore, although supercritical CO2 enhances the absolute permeability and flow capacity of the coal reservoir, the resulting heterogeneity must be carefully considered when evaluating CO2 injectivity, sweep efficiency, and long-term sequestration performance.

4.2. Stress–Strain and Permeability Response of Coal Reservoir to Supercritical CO2 Injection

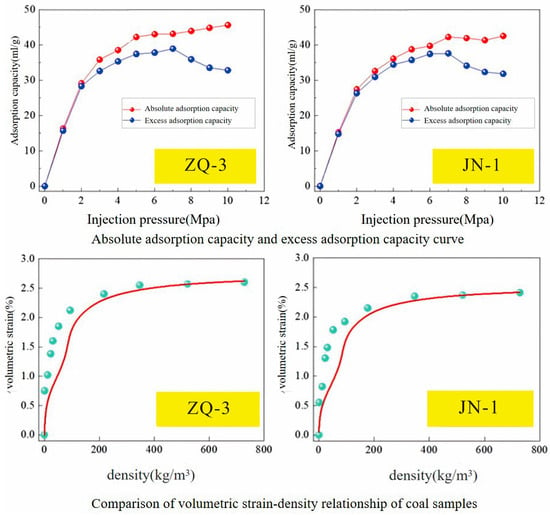

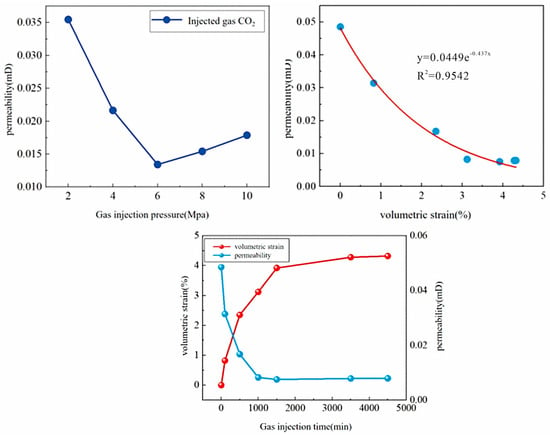

The CO2 adsorption capacity increased with rising pressure, following a typical Langmuir-type trend, consistent with classical adsorption theory. In the low-pressure stage (below the critical pressure of approximately 7.4 MPa), the adsorption capacity increased rapidly, primarily dominated by monolayer adsorption of CO2 molecules on the coal matrix surface. As the pressure exceeded the critical value, the adsorption rate significantly decreased, indicating the gradual formation of multilayer adsorption or approach to saturation within the coal pores, with the adsorption mechanism shifting from surface-dominated to pore-filling dominated. The volumetric strain also exhibited a Langmuir-type progressive saturation characteristic with increasing CO2 density (equivalent to injection pressure) (Figure 12). Notably, in the low-pressure region (<2 MPa), the experimentally measured volumetric strain values were significantly higher than theoretical predictions, reflecting a stronger adsorption-induced swelling potential of the coal matrix under low-stress conditions. This discrepancy may originate from the microstructural heterogeneity of coal and the adsorption-strain coupling effect, suggesting certain limitations of classical theories in describing the mechanical response of coal under multi-physical field interactions.

Figure 12.

Absolute Adsorption Capacity and Excess Adsorption Capacity Curves, and Comparison of Coal Sample Volumetric Strain vs. Density Relationship.

Regarding permeability evolution, the permeability exhibited distinct staged response characteristics during CO2 injection. Under a confining pressure of 15 MPa, permeability showed complex non-linear evolution with changing CO2 injection pressure. When the injection pressure increased from 2 MPa to 6 MPa, the coal permeability decreased significantly; however, when the pressure was further raised to 10 MPa, the permeability showed a certain degree of “rebound”. Further analysis indicated that permeability decreased negatively exponentially with increasing volumetric strain, and its evolution process could be divided into three typical stages: In the initial stage (<500 min), permeability dropped sharply, primarily controlled by adsorption-induced coal matrix swelling and the compression of seepage space. In the intermediate stage (500–1500 min), adsorption approached equilibrium, the rate of volumetric strain increase slowed, the decline in permeability diminished, and it gradually reached a minimum value. In the later stage (>1500 min), permeability slowly recovered, possibly related to stress concentration at fracture tips induced by supercritical CO2 and micro-fracture propagation, reflecting the potential of mechanical effects to modify seepage channels (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

CO2 Gas Permeability vs. Injection Pressure Relationship Curve and Evolution Law of Coal Volumetric Strain and Permeability Over Time.

The evolution of the pore–fracture system in coal reservoirs following supercritical CO2 injection is fundamentally governed by the coupled competition among adsorption-induced swelling, mineral dissolution, and secondary precipitation. These processes jointly reshape the internal structure of the reservoir, thereby exerting a first-order control on permeability evolution and engineering performance.

Multidimensional characterization reveals that supercritical CO2, driven by strong adsorption capacity, induces matrix swelling that expands primary micro-fractures and facilitates the development of newly formed fracture networks. When combined with mineral dissolution—which removes clay and carbonate fillings within pores—this leads to a substantial increase in total pore volume and a marked improvement in the connectivity of the pore–fracture system. Evidence from low-field NMR T2 spectra further confirms the promotion of pore transformation, with micropores progressively converting into seepage-effective pores, thus forming more efficient pathways for fluid migration.

However, the structural evolution exhibits a clear pore-size-dependent dual effect. Dissolution reactions predominantly enlarge pores within the small–medium size range, while secondary mineral precipitation favors deposition within larger pores and fracture apertures, resulting in partial blockage. This phenomenon reflects the dynamic equilibrium between dissolution and precipitation, emphasizing that pore enlargement and pore constriction coexist throughout the CO2-coal interaction. It is particularly noteworthy that low-temperature gas adsorption results show minimal changes in the geometric morphology of coal pores, whereas multifractal analysis demonstrates a significant increase in structural heterogeneity. This indicates that the primary enhancement mechanism of permeability arises not from altering the fundamental pore geometry, but from redistributing pore size fractions, improving hierarchical complexity, and generating more interconnected flow channels. These insights provide a deeper understanding of the multi-field coupling mechanism governing reservoir modification. While adsorption-induced swelling may cause short-term permeability reduction near the wellbore, the synergistic effects of mineral dissolution and pore-size restructuring ultimately alleviate flow resistance and improve long-term seepage capacity. From an engineering perspective, this underscores the necessity of regulating injection pressure, rate, and thermodynamic conditions to balance dissolution and precipitation processes, thereby precisely controlling the operational window in which permeability enhancement is maximized.

4.3. Numerical Simulation of Supercritical CO2 Displacing Coalbed Methane

4.3.1. Influence of Injection Pressure on Reservoir Permeability

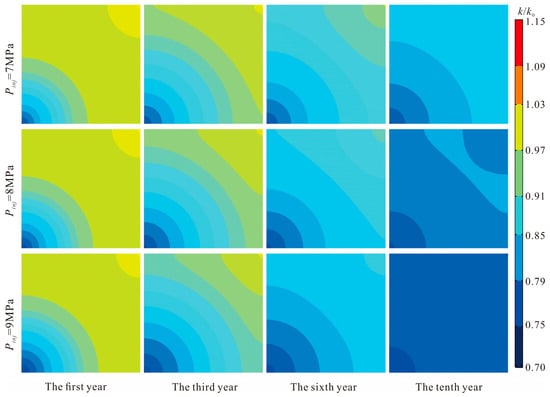

During CO2 injection into the reservoir, permeability—as a key parameter controlling fluid migration efficiency and storage performance—is directly governed by the coupled effects of injection pressure and injection duration, exhibiting significant spatiotemporal heterogeneity. In the initial injection phase, permeability evolution displays distinct near-wellbore differentiation: in the vicinity of the injection well, intense physical adsorption of CO2 onto the reservoir matrix, particularly in coal seams, induces matrix particle swelling and constriction of pore throats. Concurrently, geochemical effects triggered by CO2 dissolution, such as mineral dissolution-reprecipitation and clay mineral swelling, further obstruct flow pathways, collectively leading to a continuous decline in permeability in this region. In contrast, near production wells yet unaffected by CO2 influx, the expulsion of reservoir fluids is accompanied by the release of effective matrix stress and matrix shrinkage, resulting in a slight dilation of pore space and a transient, modest recovery in permeability.

With prolonged injection, CO2 continuously diffuses and displaces deeper into the reservoir under the driving force of pressure differentials, progressively expanding its zone of influence. The region of reduced permeability, initially confined to the vicinity of the injection well, gradually extends further into the reservoir interior, leading to a marked increase in the spatial proportion of overall low-permeability zones. Once the CO2 front reaches the production well, a fundamental shift occurs in the reservoir fluid environment. Competitive adsorption between CO2 and native reservoir fluids, such as methane and formation water, becomes dominant. The stronger adsorption affinity of CO2 causes renewed matrix swelling, completely offsetting the earlier pore-enhancement effect resulting from matrix shrinkage. Consequently, permeability near the production well transitions from the previous slight recovery to a sustained decline, a trend that intensifies with increasing CO2 saturation.

As a key external driver governing CO2 migration dynamics and interaction intensity within the reservoir, injection pressure exerts a strong amplifying effect on both the rate and spatial pattern of permeability evolution. The results of this study show that the expansion of the permeability-reduction zone increases almost linearly with injection pressure, with higher pressures producing more rapid permeability decline. The underlying mechanism reflects the multi-field coupling of adsorption, diffusion, and geochemical reactions under elevated pressure conditions.

Mechanistically, increasing injection pressure enhances the chemical potential and adsorption driving force of CO2, thereby accelerating both the adsorption rate and ultimate adsorption capacity. This intensifies matrix swelling, redistributes internal stresses, and promotes the progressive closure of micro-fractures in the near-wellbore region. Meanwhile, higher pressure elevates the diffusion coefficient and displacement efficiency of CO2 in the pore–fracture system, enabling the CO2 influence front to advance more rapidly into the formation. The faster propagation of the influence front causes the permeability-reduction zone to enlarge in a pressure-dependent manner.

Additionally, elevated pressure conditions significantly accelerate the kinetics of geochemical reactions. Processes such as carbonate dissolution, clay hydration-swelling, and secondary mineral precipitation become more pronounced, cumulatively narrowing pore throats and obstructing flow pathways. These findings are consistent with existing studies showing that CO2 adsorption capacity and adsorption-induced swelling are positively correlated with pressure. However, the present study further quantifies this dependency, demonstrating a proportional increase in both the spatial extent of permeability damage and the rate of permeability decline with each incremental rise in injection pressure (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Influence Law of Injection Pressure and Injection Time on the Extent of Permeability Reduction Zone.

From an engineering standpoint, optimizing injection pressure requires balancing CO2 injectivity, sweep efficiency, and long-term reservoir integrity. Excessively high injection pressures may enhance storage capacity and enlarge the CO2 sweep radius but simultaneously accelerate permeability degradation, posing risks to long-term sealing effectiveness and adversely affecting CH4 displacement efficiency in ECBM or storage-production coupling scenarios. In contrast, pressures that are too low restrict CO2 migration and reduce storage efficiency. Moreover, the coupling between pressure and permeability evolution is further modulated by reservoir heterogeneity, initial permeability architecture, mineral composition, and formation temperature-factors that must be incorporated into pressure-management strategies for field application.

4.3.2. Influence of Injection Pressure on Coalbed Methane Production Enhancement and Carbon Sequestration

As a synergistic technology crucial for achieving the “Dual Carbon” goals and a win-win situation for energy development, the coupled influence mechanism of injection pressure the core control parameter on CO2 sequestration efficiency and CH4 production capacity has attracted much attention. After CO2 is injected into the coal reservoir via the injection well, driven by concentration gradients and pressure differences, it first undergoes physical adsorption in the micropores and fracture system of the coal matrix near the injection well. This process stems from the significantly higher adsorption affinity of coal organic matter for CO2 compared to CH4, and the coal matrix, as a typical porous medium, provides a foundation for rapid CO2 adsorption with its surface-rich adsorption sites. The adsorption behavior of CO2 molecules disrupts the original mechanical equilibrium of the coal matrix, inducing volumetric swelling deformation in the coal, specifically manifested as elastic expansion of micropore walls and compressive deformation of the fracture network. As injection time prolongs, the adsorption capacity of the coal matrix for CO2 gradually approaches saturation, and the adsorption-induced swelling deformation also continuously increases until eventually stabilizing. At this point, the pore–fracture structure of the coal reservoir reaches a new state of mechanical equilibrium, laying the foundation for subsequent CH4 displacement and long-term CO2 sequestration.

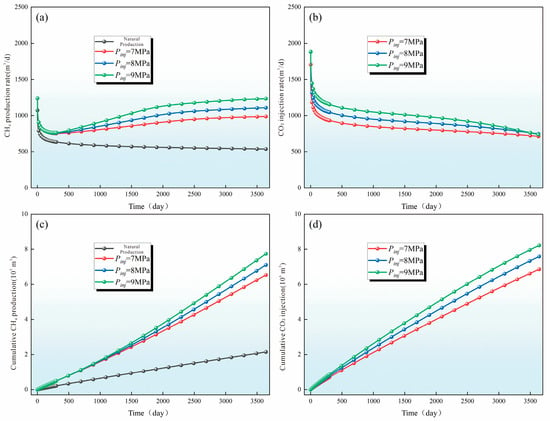

The level of injection pressure fundamentally governs the synergistic performance of CBM production enhancement and CO2 sequestration. The results of this study confirm that higher injection pressures are more favorable for simultaneously improving CH4 recovery and increasing CO2 storage capacity in the target reservoir. The underlying mechanisms can be interpreted in depth from two interrelated perspectives (Figure 15). On one hand, elevated injection pressure markedly intensifies the competitive adsorption dynamics between CO2 and CH4. Under high-pressure conditions, the adsorption driving force and mass-transfer rate of CO2 increase substantially, leading to both accelerated adsorption kinetics and a notable rise in adsorption capacity. This enables CO2 to rapidly occupy high-energy adsorption sites on the coal matrix, displacing pre-adsorbed CH4 through a pressure-enhanced “molecular squeezing” or site-competition effect. Consequently, a greater proportion of CH4 transitions from the adsorbed phase to the free phase, where it can more readily migrate toward production wells, thereby improving recovery efficiency. Simultaneously, higher pressure significantly increases the diffusion coefficient, advection velocity, and displacement efficiency of CO2 in the pore–fracture network. This promotes rapid outward propagation of the CO2 influence front from the near-well region into deeper zones of the reservoir, effectively enlarging the sweep radius. The expansion of the sweep domain enhances the volume of CH4 participating in displacement, thus increasing the overall production scale. Moreover, the pressure amplification effect improves the mobilization of CH4 trapped in low-permeability domains, allowing more complete reservoir drainage. On the other hand, elevated injection pressure is essential for efficient and secure CO2 sequestration. High pressure elevates the adsorption saturation of CO2 in the coal matrix and substantially increases its solubility in formation water, facilitating the formation of a stable aqueous CO2 solution. When conditions permit, CO2 transitions into the supercritical state, exhibiting lower viscosity and higher density, which enhances its storage density while reducing mobility and leakage risk. In addition, the adsorption-induced swelling of the coal matrix becomes more pronounced under high-pressure CO2 exposure. This swelling contributes to the partial closure of micro-fractures and the tightening of pore throats, generating a beneficial “self-sealing” effect. Such self-induced sealing not only improves CO2 retention and long-term storage stability but also suppresses ineffective CH4 loss through unintended flow paths, thereby further reinforcing the dual benefits of production enhancement and sequestration. Collectively, these mechanisms demonstrate that high injection pressure acts as a multi-dimensional enhancer—simultaneously strengthening CH4 displacement efficiency, CO2 trapping mechanisms, reservoir sweep effectiveness, and storage security. This underscores the importance of optimized pressure regulation for maximizing the coupled benefits of CO2-ECBM operations.

Figure 15.

Influence of Injection Pressure on CH4 Production Dynamics and CO2 Sequestration Performance. ((a) Evolution of CH4 production rate under different CO2 injection pressures; (b) Evolution of CO2 injection rate under different injection pressures; (c) Cumulative CH4 production under different CO2 injection pressures; (d) Cumulative CO2 injection under different injection pressures.).

5. Conclusions

Supercritical CO2 induces coupled adsorption–swelling and geochemical dissolution effects that jointly reshape the pore–fracture system of deep coal reservoirs. Adsorption swelling promotes the expansion and reactivation of micro-fractures, while mineral dissolution removes pore fillings and creates new flow channels. Although the fundamental pore geometry remains unchanged, the pore–fracture network becomes more heterogeneous and structurally complex. This restructuring significantly enhances pore volume and connectivity, providing the intrinsic basis for CO2 injectivity and CH4 displacement.

The permeability evolution of coal under CO2 injection follows a characteristic three-stage pattern—rapid decline, slow attenuation, and gradual rebound—controlled by the competition among adsorption swelling, mineral dissolution, and stress redistribution. A negative exponential correlation between permeability and volumetric strain demonstrates that swelling dominates early permeability loss, whereas fracture reactivation and dissolution progressively alleviate flow blockage at higher pressures. This dynamic evolution reveals the essential multi-field coupling mechanism governing deep-reservoir CO2–ECBM performance.

Injection pressure is the dominant engineering parameter regulating CO2 migration, permeability evolution, CH4 displacement efficiency, and storage stability. Higher injection pressures accelerate CO2 adsorption, diffusion, and sweep expansion, thereby enhancing competitive adsorption and improving methane production. However, excessively high pressures enlarge the permeability-reduction zone and may induce formation instability or fracture blockage, whereas insufficient pressure limits the effective sweep volume. An optimal injection-pressure window is therefore essential for balancing injectivity, sweep efficiency, and long-term storage security.

The integrated experimental–numerical framework developed in this study provides quantitative insight into CO2–coal multi-field interactions and offers a scientific basis for designing CO2-ECBM strategies in deep, heterogeneous coal reservoirs. The combined laboratory measurements and multi-physics simulations comprehensively describe the adsorption–deformation–flow–geochemistry coupling process, enabling accurate evaluation of CO2 injectivity and production-enhancement potential in the Yanchuannan and Jinzhong blocks. These results offer critical theoretical and technical support for future CO2-ECBM demonstration and for improving CBM development efficiency under carbon-neutrality goals.

Author Contributions

H.G.: data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, project administration, and writing—original draft. Y.T.: data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, methodology, resources, and writing—review & editing. H.Z.: data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, project administration, and writing—review & editing. Y.L.: software, supervision, data curation, and writing—review & editing. Y.C.: software, supervision, data curation, and writing—review & editing. X.L.: software, supervision, data curation, and writing—review & editing. Y.G.: validation, software, supervision, data curation, and writing—review & editing. C.L.: software, supervision, data curation, visualization, and writing—review & editing. C.H.: software, supervision, data curation, visualization, and writing—review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42302194); the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province, China (No. BK20231084); and the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2021A1515110723).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Hequn Gao, Yinan Cui, Xin Li, Yue Gong, Chao Li were employed by the East China Oil and Gas Company. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Li, Y.L.; Wei, Y.F.; Zhu, F.Q.; Du, J.Y.; Zhao, Z.M.; Ouyang, M. The path enabling storage of renewable energy toward carbon neutralization in China. Etransportation 2023, 16, 100226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.S. The view of technological innovation in coal industry under the vision of carbon neutralization. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2021, 8, 1197–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Min, Z.; Yang, M.X.; Yan, J. Exploration of the implementation of carbon neutralization in the field of natural resources under the background of sustainable Development—An overview. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, H.Y.; Lau, Y.Y.; Wang, T.N.; Wang, W.; Zhang, G.S. Climate change, carbon peaks, and carbon neutralization: A bibliometric study from 2006 to 2023. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Y.; Liu, X.M.; Zhang, Z.Q. Application of red mud in carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) technology. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2024, 202, 114683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.H. Low-carbon utilization of coal gangue under the carbon neutralization strategy: A short review. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2023, 25, 1978–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.P.; Zhang, Z.M.; Guo, Z.H.; Su, C.; Sun, L.H. Energy structure transformation in the context of carbon neutralization: Evolutionary game analysis based on inclusive development of coal and clean energy. J. Clean Prod. 2023, 398, 136626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storrs, K.D.P.; Lyhne, I.; Drustrup, R. A comprehensive framework for feasibility of CCUS deployment: A meta–review of literature on factors impacting CCUS deployment. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2023, 125, 103878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mon, M.T.; Tansuchat, R.; Yamaka, W. CCUS technology and carbon emissions: Evidence from the United States. Energies 2024, 17, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, M.; Misra, S. A review of experimental research on Enhanced Coal Bed Methane (ECBM) recovery via CO2 sequestration. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2018, 179, 392–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.X.; He, N.P.; Xu, L.; Peng, C.H.; Chen, H.; Yu, G.R. Eco-CCUS: A cost-effective pathway towards carbon neutrality in China. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2023, 183, 113512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, A.; Gensterblum, Y. CBM and CO2-ECBM related sorption processes in coal: A review. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2011, 87, 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.W.; Yu, H.J.; Bai, Y.S.; Wang, Y.J.; Hu, H.Q. Numerical study on the influence of temperature on CO2-ECBM. Fuel 2023, 348, 128613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.F.; Zhao, Y.X.; Yuan, L. CO2-ECBM in coal nanostructure: Modelling and simulation. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2018, 54, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.W.; Bai, D.R.; Xu, C.M.; He, M.Y. Challenges and opportunities for engineering thermochemistry in carbon-neutralization technologies. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2023, 10, nwac217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.D.; Sang, S.X.; Zhou, X.Z.; Wang, Z.L.; Niu, Q.H.; Mondal, D. Modelling of geomechanical response for coal and ground induced by CO2-ECBM recovery. Gas Sci. Eng. 2023, 113, 204953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.J.; Yao, Y.B.; Liu, D.M.; Cai, Y.D.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.W. Nuclear magnetic resonance T2 cutoffs of coals: A novel method by multifractal analysis theory. Fuel 2019, 241, 715–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.L.; Wang, E.Y.; Li, B.B.; Kong, X.G.; Xu, J.; Peng, S.J.; Chen, Y.X. Laboratory experiments of CO2-enhanced coalbed methane recovery considering CO2 sequestration in a coal seam. Energy 2023, 262, 125473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Wang, L.; Naveen, P.; Longinos, S.N.; Hazlett, R.; Ojha, K.; Panigrahi, D.C. Influence of competitive adsorption, diffusion, and dispersion of CH4 and CO2 gases during the CO2-ECBM process. Fuel 2024, 358, 130065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.D.; Lin, X.S.; Zhu, W.C.; Hu, Z.; Hao, C.M.; Su, W.W.; Bai, G. Effects of coal permeability rebound and recovery phenomenon on CO2 storage capacity under different coalbed temperature conditions during CO2-ECBM process. Energy 2023, 284, 129196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.J.; Yao, Y.B.; Liu, D.M.; Cai, Y.D.; Liu, Y. Characterizations of full-scale pore size distribution, porosity and permeability of coals: A novel methodology by nuclear magnetic resonance and fractal analysis theory. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2018, 196, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, S.L.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, T.Y.; He, W.; Hu, W.Q.; Yin, H.C.; Ma, L.S.; Hong, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, B. Numerical simulation of CO2-ECBM for deep coal reservoir with strong stress sensitivity. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, J.H.; Xue, J.H.; Zhang, C.; Fang, X.Q. Experimental studies on the changing characteristics of the gas flow capacity on bituminous coal in CO2-ECBM and N2-ECBM. Fuel 2021, 291, 120115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujioka, M.; Yamaguchi, S.; Nako, M. CO2-ECBM field tests in the Ishikari Coal Basin of Japan. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2010, 82, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwakipunda, G.C.; Wang, Y.T.; Mgimba, M.M.; Ngata, M.R.; Alhassan, J.; Mkono, C.N.; Yu, L. Recent advances in carbon dioxide sequestration in deep unmineable coal seams using CO2-ECBM technology: Experimental studies, simulation, and field applications. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 17161–17186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishal, V.; Singh, T.N.; Ranjith, P.G. Influence of sorption time in CO2-ECBM process in Indian coals using coupled numerical simulation. Fuel 2015, 139, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Y.; Wang, J.L.; Li, H.Y.; Liu, J.R.; Xu, J.C.; Sun, W.Y.; Wang, X.P.; Chen, Z.H. A generalized adsorption model of CO2-CH4 in shale based on the improved Langmuir model. Fuel 2025, 379, 132971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.J.; Yao, Y.B.; Liu, D.M.; Cai, Y.D.; Liu, Y. Nuclear magnetic resonance surface relaxivity of coals. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2019, 205, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.Y.; Wen, H.; Fan, S.X.; Wang, Z.P.; Fei, J.B.; Wei, G.M.; Chen, X.J.; Wang, H. Experimental study of CO2-ECBM by injection liquid CO2. Minerals 2022, 12, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L.; Sang, S.X.; Zhou, X.Z.; Liu, X.D. Numerical study on CO2 sequestration in low-permeability coal reservoirs to enhance CH4 recovery: Gas driving water and staged inhibition on CH4 output. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 214, 110478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.D.; Sang, S.X.; Zhou, X.Z.; Wang, Z.L. Coupled adsorption-hydro-thermo-mechanical-chemical modeling for CO2 sequestration and well production during CO2-ECBM. Energy 2023, 262, 125306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damen, K.; Faaij, A.; Bergen, F.V.; Gale, J.; Lysen, E. Identification of early opportunities for CO2 sequestration—Worldwide screening for CO2-EOR and CO2-ECBM projects. Energy 2005, 30, 1931–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.