Abstract

This study investigates how economic growth, financial integration, social integration, and knowledge management shape CO2 emissions in Saudi Arabia using quarterly data from 1995Q1 to 2024Q4. It applies kernel-regularized quantile regression to capture nonlinear and state-dependent effects across the conditional distribution of emissions without imposing restrictive parametric assumptions, while regularization mitigates overfitting and multicollinearity. The results reveal strong distributional heterogeneity. Economic growth is emission-augmenting and is strongest at the lower tail, weaker around the median, and positive again in the upper tail. Financial integration reduces emissions across quantiles, most strongly under low-emission states, while social integration is mostly near-neutral beyond the lower tail. Knowledge management increases emissions throughout, and quantile Granger causality is concentrated in the upper quantiles, indicating stronger predictive linkages when emissions are high. Based on these findings, this study proposes precise, quantile-specific policy guidelines across the distribution.

1. Introduction

From Rio’s 1992 UNFCCC to the latest COP summits, sustainability has been the organizing principle of global climate governance and transition roadmaps. Deliberations consistently emphasize the human and ecological toll of escalating heat—manifest in severe weather and environmental degradation [1,2]. Reflecting this urgency, COP28’s UAE Consensus urged accelerated adaptation in food production, expanded investments in efficiency and clean energy, and a firm move away from unabated fossil fuel use (UAE Consensus, 2024). For Saudi Arabia, these priorities dovetail with national transition ambitions and reinforce the imperative to deliver on the United Nations 2030 Agenda—advancing climate action (SDG 13), affordable and clean energy (SDG 7), innovation and industrial upgrading (SDG 9), and resilient, opportunity-creating growth (SDG 8).

As nations continue to rely on oil, gas, and coal, natural capital diminishes and environmental pressures mount, reinforcing the case for a shift to cleaner energy systems. In hydrocarbon-intensive contexts such as Saudi Arabia, progress hinges not only on technology and finance but also on the systematic capture, codification, and diffusion of organizational knowledge—i.e., effective knowledge management (KM). KM enables energy producers, utilities, and regulators to institutionalize best practices in efficiency, methane abatement, and the grid integration of renewables [3,4]. Financial integration (FI) can channel diversified capital—green bonds, sustainability-linked instruments, and cross-border project finance—into these priorities [5,6], while social integration (SI) strengthens networks of collaboration that speed learning, standard setting, and public acceptance. Together, KM, FI, and SI form mutually reinforcing levers for reducing CO2 intensity without derailing growth.

Entrepreneurial and firm-level dynamics are pivotal in this transition. KM practices—communities of practice, lessons-learned repositories, and data-driven performance dashboards—raise the absorptive capacity, shorten the innovation cycle, and scale process improvements across both large incumbents and small and medium-sized enterprises [3,7]. SI complements these efforts by building trust and information flows across supply chains, clusters, and professional associations, thereby lowering coordination costs for deploying clean technologies and demand-side management. FI, in turn, widens the menu of risk-sharing arrangements and brings international sustainability standards to bear on domestic projects [8,9]. When KM equips organizations to identify, adapt, and routinize greener practices, and SI and FI reduce frictions in funding and diffusion, the result is a tighter coupling between innovation efforts and measurable environmental sustainability (lower CO2 per unit of output).

Saudi Arabia’s accelerating digital transformation amplifies these mechanisms. Advanced analytics, industrial IoT, and AI—embedded in asset integrity, leak detection, load forecasting, and desalination—produce high-frequency data that KM systems can curate into actionable knowledge. This data-knowledge pipeline strengthens continuous-improvement loops in utilities, petrochemicals, transport, and buildings. SI expands the reach of these loops by connecting universities, standards bodies, and industry alliances; FI mobilizes blended finance and performance-based contracts to move pilots into scale. In combination, digitalization enables KM to operate at speed and scope, while SI and FI provide the channels and capital for system-level decarbonization.

Yet, capability and governance gaps remain. Emission mitigation at scale requires durable KM routines (e.g., root-cause learning, cross-site benchmarking), credible ESG assurance, and integrated planning that aligns investment portfolios with science-based targets [10,11]. Expanding ESG disclosure and assurance frameworks can heighten accountability and comparability, but their real impact depends on how effectively firms learn from disclosures and translate them into operational change [12]. Against this backdrop, the present study examines how KM, FI, and SI jointly shaped environmental sustainability—proxied by CO2 emissions—in Saudi Arabia over 1995Q1–2024Q4, illuminating whether integration (financial and social) strengthens the pathway through which organizational knowledge is converted into lower carbon intensity.

The contribution is threefold. First, this study contributes by providing the first empirical evidence for Saudi Arabia on how social and financial integration jointly influence the path of environmental sustainability, and by translating these findings into a practical policy blueprint that resource-rich, integration-intensive economies with similar structures can adapt to accelerate low-carbon transition without sacrificing growth. Second, it informs policy design for advancing SDGs 7, 9, and 13 in a resource-rich economy seeking high-productivity, low-carbon growth. Third, this study employed the novel kernel-regularized quantile regression (KRQR), as formulated by [13], to capture heterogeneous, state-dependent effects across the CO2 distribution. KRQR models nonlinear interactions via kernel functions without imposing restrictive parametric forms and uses regularization to curb overfitting and multicollinearity—features well suited to complex, interdependent drivers such as KM, FI, and SI. By replacing purely linear or single-state techniques with KRQR, the analysis recovers how these levers bite differently in lower- versus higher-emission states, providing decision-relevant insight into where knowledge practices and integration policies yield the greatest decarbonization payoffs.

2. Theoretical Framework and Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Framework

Knowledge management (KM) shapes CO2 by transforming how firms and economies create, absorb, and deploy knowledge to cut carbon intensity. Through the codification and sharing of best-practice routines, KM accelerates process and product eco-innovation (e.g., energy-efficient production lines, low-carbon logistics), strengthens organizational “absorptive capacity,” and reduces information frictions that slow green technology diffusion [14]. In competitive, regulated settings, KM also complements dynamic capabilities—continuous learning, experimentation, and cross-functional integration—that enable compliance at lower cost and stimulate “innovation offsets” consistent with the Porter hypothesis, thereby lowering CO2 per unit of output [15]. Still, KM can raise total emissions if efficiency gains expand output or energy service demand (rebound/scale effects), implying that KM’s net effect on CO2 hinges on complementary policies (carbon pricing, standards), digitalization that improves measurement and control, and the firm’s baseline energy mix [15,16].

Integration—social (people, ideas, norms) and financial (cross-border capital flows)—alters ES through classic scale, composition, and technique channels. Greater social integration deepens transnational knowledge spillovers and norm diffusion [17], which can shift production toward cleaner techniques and raise the societal demand for abatement; yet, it can also expand activity (scale) or relocate dirty stages of value chains unless institutions are strong ([18] p. 199). Financial integration mobilizes capital for green technologies, reduces the cost of clean investment, and disciplines high-emitting firms via global investors’ ESG preferences; conversely, weak governance risks “pollution-haven” dynamics and carbon-intensive capital deepening [19]. The net CO2 outcome is therefore conditional on the regulatory quality, carbon pricing, financial development, and energy structure: with robust institutions and green finance, integration complements KM to drive technique upgrades and decarbonization; without them, scale/composition effects dominate and CO2 rises [20].

2.2. Literature Review

This section presents a concise review of the literature on factors that shape environmental sustainability, with a focus on knowledge management and integration in its social and financial dimensions. The evidence is organized into the following subsections, where each strand is discussed in detail.

2.2.1. Knowledge Management and CO2 Emissions

Knowledge management is seen as a substantive lever for decarbonization across firm, sector, supply chain, and cross-country settings [4,20,21]. At the firm level, knowledge management turns routines, absorptive capacity, and problem solving into lower energy intensity and effective abatement choices, as shown for Chinese-listed firms, where knowledge outputs measured through green innovation and managerial specialization are associated with reduced corporate CO2 over 2000–2021 using IV and GMM designs [22]. Sector evidence points the same way, since knowledge-driven innovation in the Chinese construction industry during 2005–2020 lowered emissions under two-way fixed effects [23]. Process-intensive activities also benefit because global cement plants that use codified best practices and peer comparison achieve reductions in their process emission intensity through structured benchmarking and diffusion of know-how [7]. Digital infrastructures add a data governance channel, since controlling dark data through better knowledge practices saves energy in data centers and reduces associated emissions. Organizational culture matters as well because cross-sectional evidence shows that knowledge practices lift environmental awareness [3] and sustainable behaviors, creating a behavioral complement to technological upgrading [4].

Beyond individual firms, knowledge becomes more powerful when embedded in networks that accelerate learning and coordination. Along industrial chains, shared knowledge resources strengthen the carbon reduction capability by aligning standards, interfaces, and joint problem solving across upstream and downstream actors [24]. Formal knowledge sharing between maritime ports and liners under carbon policies improves equilibrium abatement, indicating that coordinated information flows can realign incentives within supply chains [11]. Cross-border diffusion adds a macro-channel since European panel evidence shows that climate technology spillovers lower national CO2 once knowledge travels across jurisdictions [2]. Multi-region analyses further indicate that spillovers in energy innovation mitigate emissions even where aggregate research and development has mixed environmental effects, which highlights the importance of what type of knowledge diffuses rather than how much is spent in total [25]. Table 1 presents the summary of the above studies.

Table 1.

Knowledge management and environmental sustainability.

2.2.2. Integration (Social and Financial) and CO2 Emissions

The environmental effect of integration is component-specific and context-dependent. Social integration often raises emissions through consumption convergence, mobility, and lifestyle diffusion, which is consistent with the positive links between social integration and CO2 in China and across large country panels [25,26]. Financial integration also tends to elevate environmental pressure in many emerging settings where inflows amplify scale effects and carbon-intensive investment, a result that appears in broad samples of developing economies and in several South Asian assessments, with integration strongly connected to CO2 alongside energy use [27,28]. Yet, the same financial channel can reduce emissions when resource rents, policy credibility, and regulation align, as shown by the OPEC sample, where financial openness is associated with lower CO2 while non-OPEC countries experience the opposite sign [29]. Political integration frequently mitigates emissions by tightening environmental commitments and rule harmonization, while trade and economic integration show mixed outcomes that hinge on technology diffusion versus scale and composition effects, with several panels reporting reductions in high-rule-of-law regions and increases where governance is weak or the industry mix is carbon-heavy [30].

Distributional results add another layer. Globalization reduces CO2 at the cleaner end of the emission distribution, suggesting that countries in low-emission states have the institutional and technological capacity to convert openness into efficiency and cleaner production, whereas high emitters may translate the same openness into larger-scale effects and carbon lock-in [31]. Recent studies on emerging economies and the OIC group reinforce this heterogeneity, with economic and social integration frequently associated with higher CO2, and with new evidence suggesting that economic integration alone can raise emissions in post-1990 samples, although magnitudes differ by income and the depth of capital markets [31,32]. Taken together, the literature implies that social integration (SI) and financial integration (FI) often exert upward pressure on CO2 unless complemented by strong institutions, credible carbon pricing, and technology standards, whereas political integration (PI) and well-governed trade and economic integration (EI) and TI can channel spillovers toward abatement. Table 2 presents the summary of the above studies.

Table 2.

Integration (social and financial) and CO2 emissions.

3. Data and Method

3.1. Data

This study examines the effect of knowledge management (KM) on CO2 emissions in the case of Saudi Arabia. In this study, environmental sustainability is used to proxy CO2 emissions, on the grounds that CO2-intensive activities are a primary driver of deteriorating environmental quality and are embedded in broader sustainability outcomes. By focusing on environmental sustainability, the analysis captures not only direct carbon emissions but also the underlying structural and policy factors that shape long-run CO2 dynamics. Additional drivers of ES considered are social integration (SI), financial integration (FI), and economic growth (EG), using data from 1995Q1 to 2024Q4. The dependent variable is CO2, while the regressors are SI, FI, EG, and KM. Most variables—including KM, SI, and FI—are constructed as indices, whereas EG and CO2 are measured in per-capita terms.

This study used the eight World Development Indicator (WDI) series to measure knowledge management (KM). Specifically, KM is proxied by internet users (% of population), secure internet servers (per 1 million people), research and development expenditure (% of GDP), researchers in R&D (per million people), high-technology exports (% of manufactured exports), scientific and technical journal articles, patent applications by residents, and the gross tertiary enrolment ratio (both sexes, %).

Likewise, this study uses the KOF Globalisation Index social and financial globalization sub-indices directly, without constructing new composites. Social integration (SI) corresponds to the social globalization dimension, which aggregates interpersonal, informational, and cultural globalization, while financial integration (FI) corresponds to the financial globalization sub-dimension within economic globalization, as defined in the revised KOF Globalisation Index. Both SI and FI are taken in their standard composite (overall) form, combining de facto and de jure components, and are only transformed by converting them to natural logarithms to stabilize variance and ease interpretation.

Annual series were converted to quarterly frequency using the quadratic match-sum approach, thereby mitigating small-sample limitations. Further details on variable definitions and construction are provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Data measurement and sources.

3.2. Kernel-Regularized Quantile Regression Method

This study employed kernel-regularized quantile regression, suggested in [13]. Let denote the dependent variable and the vector of determinants for observation (, ). The approach builds on Kernel-Regularized Least Squares (KRLS), suggested by [39], which represents the regression function in a reproducing-kernel Hilbert space:

with typically the Gaussian RBF kernel,

and coefficients () estimated by minimizing a ridge-regularized objective (penalty ) to prevent overfitting.

To obtain distribution-sensitive effects that are robust to outliers and heteroskedasticity, KRLS is integrated with quantile regression. For a target quantile (), the conditional quantile of is modeled as

with estimated by minimizing the pinball (check) loss plus ridge penalty,

where . This “KRQR” estimator captures nonlinearities via kernels, regularizes complexity, and recovers effects at multiple parts of the EQ distribution (here, 0.10, 0.30, 0.50, 0.70, 0.90).

KRQR is implemented with a Gaussian RBF kernel, where the bandwidth (σ) is selected using the median-distance heuristic and then fine-tuned by cross-validation, while the regularization parameter (λ) is chosen via grid search to minimize the out-of-sample prediction error. The model is estimated at five quantiles of the conditional dependent-variable distribution, τ = 0.10, 0.30, 0.50, 0.70, and 0.90. To construct confidence intervals and assess the stability of the estimates, we use a nonparametric bootstrap with 500 replications for each quantile.

4. Results

4.1. Basic Data Information

Table 4 presents basic data information. The results show compact dispersion for EG (mean and median: 8.65; SD: 0.067) and FI (mean/median: 2.70; SD: 0.044), while KM varies more widely around a negative mean (−0.285) with a right-skewed distribution (skewness: 1.30) and leptokurtosis (3.86), indicating occasional high-positive realizations despite a low central tendency; CO2 is strongly left-skewed (−1.61) and sharply peaked (5.25), and SI is mildly left-skewed (−0.517) with flatter tails (1.83). Normality diagnostics via Jarque–Bera indicate clear departures from Gaussian behavior for KM, ES, and SI (JB 36.00, 74.40, and 11.80 with p-values of 0.000, 0.000, and 0.003, respectively), whereas EG and FI do not reject normality at conventional levels (JB 1.46, p 0.481; JB 2.74, p 0.254). Correlation patterns suggest KM is tightly aligned with EG (0.75) and SI (0.747) and moderately with CO2 (0.527), hinting that higher KM co-moves with stronger EG and social indicators; ES also co-moves notably with SI (0.671). By contrast, FI is only weakly related to the others (0.264 with KM; 0.037 with EG; −0.016 with ES; 0.323 with SI), implying limited contemporaneous associations with these dimensions.

Table 4.

Basic data information.

4.2. Diagnostic Tests

Table 5 presents the diagnostic tests. As shown in Table 5 Part A, KM, EG, and SI fail both Terasvirta and White linearity checks with p-values near zero, ES shows milder nonlinearity with Terasvirta (p 0.069) and White (p 0.032), while FI appears linear with p-values above 0.80. The Keenan test chiefly flags SI with p 0.024, which reinforces the stronger signals from Terasvirta and White. The BDS test rejects the i.i.d. null for every series with p-values near zero, indicating higher-order dependence even where parametric misspecification tests are quieter. Trend and persistence diagnostics are also unambiguous, since Mann–Kendall identifies monotonic trends across all variables with p-values at or below 0.004, and the Runs test rejects randomness throughout with p-values near zero, supporting models that accommodate serial dependence, structural evolution, or regime behavior. Distributional and variance properties caution against strict Gaussian and homoskedastic assumptions. Table 5 Part B shows strong departures from normality for KM, CO2, and SI under Jarque–Bera and Shapiro with p-values near zero, with KM exhibiting significant skewness and marginal excess kurtosis, CO2 combining skewness with heavy tails with kurtosis (p 0.0016), and SI failing both skewness and kurtosis checks. EG and FI look closer to Gaussian under Jarque–Bera with p-values of 0.481 and 0.254, yet Shapiro suggests mild departures at the ten percent level with p-values of about 0.075 and 0.085. the variance stability is also problematic, as Table 5 Part C indicates heteroskedasticity for KM, EG, ES, and SI under White or ARCH LM with p-values at or below 0.007, and even FI shows conditional heteroskedasticity under ARCH LM despite a null White test with p 0.863.

Table 5.

Diagnostic tests.

4.3. Stationarity Features

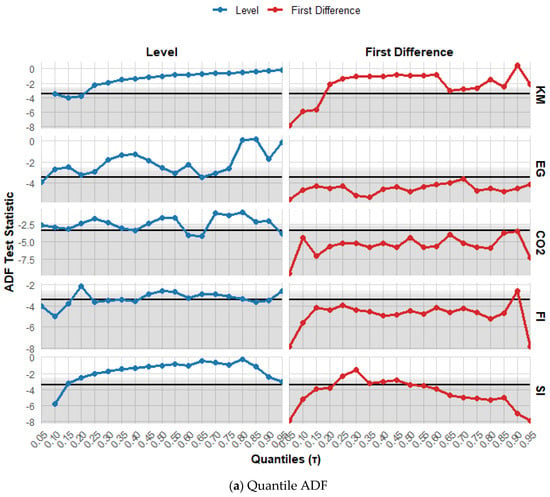

Figure 1a,b show the quantile stationarity attributes of the series. Across both quantile ADF and quantile PP panels, the null of a unit root is not rejected for most variables in levels over wide ranges of quantiles, while it is decisively rejected after first differencing, indicating stationarity of the differenced series. KM, EG, and SI display test statistics that hover near or above the critical benchmark in levels for many quantiles, so the unit root null generally holds there, but their first differences fall well below the threshold across almost all quantiles, so the null is rejected, and these series are best treated as integrated of order one. ES and FI show pockets where the level statistics dip below the critical line for some quantiles, hinting at partial-level stationarity, yet the strongest and most uniform evidence comes at first differences where both tests reject the unit root across nearly the entire quantile grid.

Figure 1.

Quantile PP and ADF.

4.4. Kernel-Regularized Quantile Regression

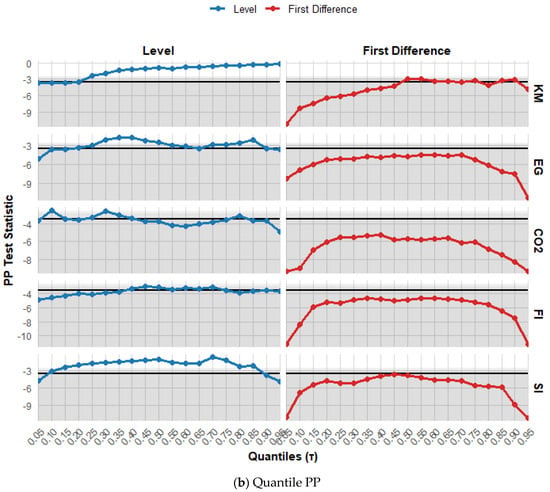

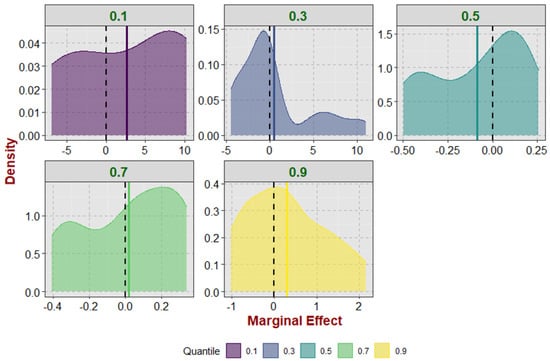

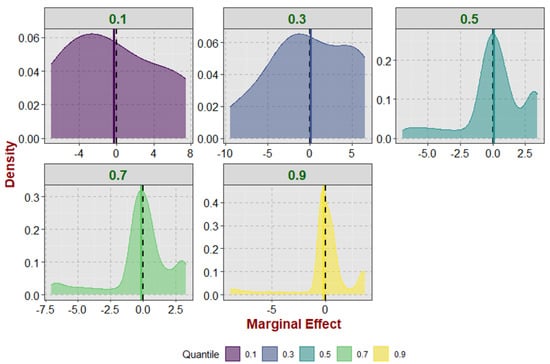

Figure 2 plots the marginal effect of economic growth (EG) on CO2 emissions in Saudi Arabia across quantiles (τ = 0.1–0.9). The figure indicates clear quantile heterogeneity, with the sign and intensity of the growth–emission link changing across emission regimes. At the lower tail (τ = 0.1), the marginal-effect distribution is overwhelmingly to the right of the zero line, with a large positive central tendency, implying that when CO2 emissions are relatively low, additional growth is strongly emission-augmenting—consistent with early-stage scale effects (higher energy demand, transport activity, and industrial throughput) dominating any efficiency improvements. At τ = 0.3, the distribution concentrates around small positive values with limited mass below zero, suggesting that as the economy moves into a lower–middle-emission state, growth still tends to raise CO2 but with a more moderate and stable effect. Around the median (τ = 0.5), the density straddles zero with substantial mass on both sides and only a slight tilt, indicating near-neutral average effects: under “typical” conditions, gains from efficiency, technology upgrading, and structural change partly offset the scale effect, producing limited decoupling. At higher quantiles (τ = 0.7 and τ = 0.9), the distributions shift further to the right and become wider, showing that in high-emission regimes, the emission impact of growth is again more clearly positive and more heterogeneous across states of the economy. Overall, the multimodal and skewed shapes imply that a single mean elasticity would be misleading; policy relevance lies in improving the composition and energy intensity of growth—accelerating diversification toward less carbon-intensive sectors, tightening energy-efficiency standards, and expanding low-carbon power—so that expansions in output translate into weaker (or eventually negative) marginal effects on CO2, especially in the upper tail, where growth currently coincides with stronger emission pressure.

Figure 2.

Effect of EG on ES.

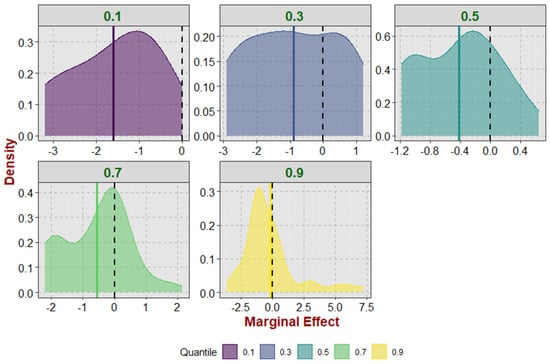

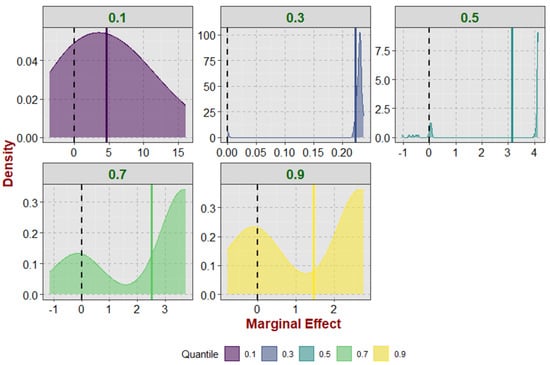

Figure 3 shows that the marginal effect of financial integration (FI) on CO2 emissions (ES) in Saudi Arabia is consistently negative across all quantiles, meaning that deeper FI is generally associated with lower CO2 emissions per capita throughout the conditional distribution. At the lower quantiles (τ = 0.1 and 0.3), the density is concentrated well below zero, indicating the strongest emission-reducing effect when CO2 levels are relatively low. Around the median (τ = 0.5), the distribution remains negative but moves closer to zero, suggesting a weaker mitigating impact at typical emission levels. At τ = 0.7, the estimates still cluster on the negative side and are nearer to zero, implying that FI continues to reduce CO2 but with a more modest magnitude. Even at the upper tail (τ = 0.9), the central mass remains negative, although the distribution becomes more dispersed with a noticeable right tail—showing that while FI usually supports emission reductions, the size of the effect can vary, and occasional outcomes may be closer to neutral.

Figure 3.

Effect of FI on CO2.

Figure 4 depicts the distribution of the marginal effect of social integration (SI) on CO2 emissions across the conditional quantiles (τ = 0.1–0.9), where the dashed vertical line at zero denotes “no effect.” At the lower quantiles (τ = 0.1 and τ = 0.3), the densities are wide and clearly straddle zero, indicating substantial heterogeneity: stronger SI can be associated with lower CO2 in some episodes (negative effects) but also with higher CO2 in others (positive effects), consistent with the idea that social connectedness may either diffuse conservation norms or, alternatively, scale mobility and consumption. Around the median (τ = 0.5), the distribution becomes more concentrated around zero, implying that SI has a small average influence on CO2 emissions under typical conditions, although a modest right-side mass suggests occasional emission-increasing responses. At higher quantiles (τ = 0.7 and especially τ = 0.9), the densities are tightly clustered near zero, showing that when CO2 emissions are relatively high, the marginal impact of SI is mostly near-neutral, with only thin tails on either side—suggesting that SI’s role is more conditional and context-dependent than uniformly emission-reducing or emission-increasing.

Figure 4.

Effect of SI on CO2.

Figure 5 illustrates the marginal effect of knowledge management (KM) on CO2 emissions across the conditional distribution (τ = 0.1–0.9). In all panels, the density of the marginal effect lies predominantly to the right of the zero benchmark (dashed line), indicating that KM is generally associated with higher CO2 emissions, although the magnitude and dispersion vary by quantile. At the lower tail (τ = 0.1), the distribution is broadly positive with a sizeable central mass, suggesting that even under relatively low-emission conditions, strengthening knowledge capture, sharing, and deployment tends to raise emissions—consistent with a scale/throughput channel that outweighs incremental efficiency gains. Around τ = 0.3, the effect remains positive but becomes tightly concentrated at small positive values, implying a more stable but modest KM–emission linkage in lower–middle-emission states. At the median (τ = 0.5), the distribution exhibits sharp peaks at high positive marginal effects, signaling threshold-type behavior where KM improvements can coincide with pronounced increases in emissions once certain operational or production intensities are reached. In the upper quantiles (τ = 0.7 and τ = 0.9), the densities become wider and partly bimodal, with limited probability mass near or below zero but dominant right-tail weight, indicating that under high-emission regimes, the emission-augmenting impact of KM is stronger and more heterogeneous. This pattern aligns with contexts such as Saudi Arabia, where formal KM infrastructure is deeply embedded in energy and heavy industry. Better project execution, faster problem solving, and the rapid diffusion of operational know-how can increase utilization and output in carbon-intensive activities. Thus, efficiency improvements (e.g., digital knowledge systems, predictive maintenance, logistics optimization) lower unit costs and downtime but may ultimately encourage higher production levels, thereby increasing aggregate CO2 emissions when the energy mix remains fossil fuel-dominated.

Figure 5.

Effect of KM on CO2.

4.5. Quantile Granger Causality Result

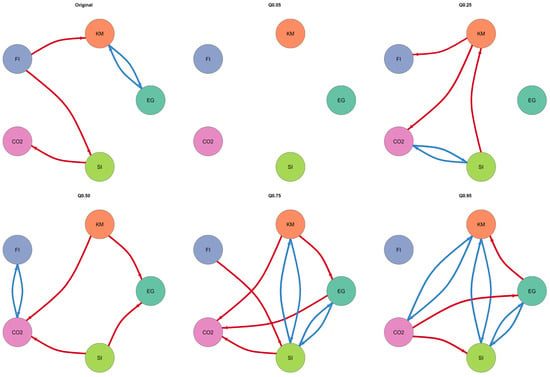

Figure 6 shows the quantile Granger causality. In the full-sample baseline, economic growth and knowledge management form a feedback loop, while several one-way links run toward social integration, including impulses from financial integration and ecological sustainability. This configuration suggests that, on average, growth and knowledge reinforce each other, and that shifts in finance and environmental conditions tend to transmit through the social channel. At the lower tail, near the fifth quantile, the system is quiet with no statistically detected causal arrows. This indicates that during very subdued conditions, the variables move largely independently, so shocks do not propagate meaningfully across domains. By the twenty-fifth quantile the web begins to form. Ecological sustainability pushes financial integration and social integration, and knowledge management sends impulses to social integration. Environmental conditions therefore act as an origin point for spillovers once the system moves away from the extreme low end, while social integration remains a key receiver.

Figure 6.

Quantile Granger causality result. Note: this study used lag 4.

Around the median, the network reorients toward growth. Ecological sustainability, social integration, and knowledge management each transmit to economic growth, and ecological sustainability and financial integration display two-way causality. This pattern implies that in typical conditions, improvements or setbacks in environmental performance, social dynamics, and knowledge practices quickly map into growth outcomes, while the finance–environment block moves together with mutually reinforcing feedback. Upper-tail dynamics are more interconnected. At the seventy-fifth quantile, social integration becomes a central hub that both receives from and feeds back to other variables, and growth interacts closely with environmental and knowledge nodes. Shocks in social or environmental dimensions at this stage can circulate through the system rather than dissipate, consistent with tighter coupling among domains when activity and emissions are elevated.

At the ninety-fifth quantile, the network is dense and multi-directional, with feedbacks linking ecological sustainability, economic growth, knowledge management, and social integration. Influence no longer runs along a single chain, and disturbances in one domain are likely to reverberate widely. For policy, this quantile view implies that interventions should be tailored to conditions. Little coordination is needed in the far low tail; early prevention and targeted support matter in lower–mid conditions, where environmental shocks begin to spill over; growth-focused coordination is critical around the median; and fully integrated packages are required in the upper tail, where feedback loops can amplify both gains and setbacks.

4.6. Discussion of Findings

The effect of economic growth on CO2 emissions in Saudi Arabia changes across the emission distribution, which means that the growth emission link is not constant across regimes. At the lower tail, where emissions are relatively low, the marginal effects are strongly positive, which is consistent with scale effects in an oil-based economy where added output increases the energy demand, transport activity, and industrial throughput faster than efficiency gains can offset. Evidence for Saudi Arabia repeatedly reports a positive growth emission association using time series methods and finds limited support for automatic turning-point dynamics without deeper structural change in production and energy systems [40,41]. As the economy moves toward typical emission conditions, the distribution around the median shifts closer to zero, suggesting that improvements in efficiency, incremental technology upgrading, and modest structural adjustment partly counterbalance scale effects, producing only limited decoupling rather than a sustained decline in emission intensity [42]. At higher quantiles, the distributions shift back toward clearly positive values and become wider, indicating that when Saudi Arabia is in a high-emission regime, growth is again more emission-augmenting, and the effect varies more across states of the economy. This aligns with sector-based evidence suggesting that emissions are closely tied to the energy intensity of value added and to the dominance of energy-intensive activities, so growth episodes linked to heavy industry, petrochemicals, and fossil-based power generation are more likely to translate into higher emissions [42].

We also found that financial integration is associated with lower CO2 emissions across all quantiles, with the strongest emission-reducing effect when emissions are relatively low and a smaller effect as emissions rise. Saudi-focused evidence links globalization dimensions, including financial channels, to better environmental outcomes when they support cleaner technology diffusion, efficiency investment, and access to capital for low-carbon infrastructure [43]. Related evidence on Saudi Arabia and broader country groups finds that financial development and openness can contribute to emission reductions by easing financing constraints for cleaner production and by improving technology adoption, even while growth and energy use remain upward pressures on emissions [9,44]. The weakening of the negative effect toward the upper tail is still consistent with this mechanism because existing fossil intensive infrastructure and industrial lock-in can limit how much marginal financial integration translates into immediate emission cuts in high-emission states [45].

Likewise, social integration has mixed effects at the lower tail and becomes close to neutral as emissions rise, which fits competing channels that can operate in opposite directions. On the one hand, greater social connectedness can diffuse environmental awareness, conservation practices, and policy support, which can reduce emissions. On the other hand, it can raise mobility, consumption, and energy-using lifestyles, which can increase emissions, especially in episodes where demand-side growth dominates. Saudi evidence on globalization suggests that social globalization can be associated with higher emissions on average, yet the variability in distributions is consistent with the idea that social forces do not always move emissions in one direction and can depend on accompanying policy and demand conditions [28,43]. The near-zero pattern at higher quantiles suggests that when emissions are already high, the main drivers are more likely to be the energy supply structure, industrial scale, and efficiency policy rather than marginal changes in social connectedness, so social integration alone is unlikely to deliver large emission reductions without stronger structural reforms [6].

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

5.1. Conclusions

This study explores, for the first time, the effects of knowledge management, social integration, and financial integration on CO2 emissions. To uncover these relationships, it employs novel quantile-based techniques—specifically kernel-regularized quantile regression and quantile Granger causality—using quarterly data from 1995Q1 to 2024Q4. This study assesses how economic growth, financial integration, social integration, and knowledge management affect CO2 emissions in Saudi Arabia using quantile-based evidence from τ = 0.1 to τ = 0.9. Economic growth is generally emission-augmenting and is strongest at τ = 0.1, smaller at τ = 0.3, near-neutral around τ = 0.5, and clearly positive again at τ = 0.7 and τ = 0.9. Financial integration consistently reduces emissions across all quantiles, with the largest reductions under cleaner states and weaker but still negative effects toward the upper tail. Social integration is regime-dependent, with effects that straddle zero at low quantiles and become mostly near-neutral at the median and upper quantiles. Knowledge management is persistently associated with higher emissions across the distribution, suggesting that efficiency gains can be outweighed by scale and throughput effects in carbon-intensive activities when the energy mix remains fossil fuel-dominated.

5.2. Practical Implications

The distributional evidence for Saudi Arabia indicates that decarbonization policy should be regime-contingent rather than guided by single average growth elasticity. Because economic growth is emission-augmenting at the lower tail and again in the upper tail, early-stage policy in relatively low-emission states should focus on preventing a rapid rise in marginal emissions as output expands. This requires binding efficiency standards for buildings, cooling loads, and energy-intensive industries, the rapid scaling of renewables for power and desalination, strict methane monitoring with enforceable limits on venting and routine flaring, and systematic reductions in grid losses. Under typical conditions, where the growth effect becomes near-neutral around the median, the priority is to lock in structural decoupling through design choices for new capacity, including electrification by default, clean-power procurement through long-term contracts, and diversification toward sectors with intrinsically lower-carbon intensity so that incremental growth does not recreate carbon-intensive pathways.

In high-emission regimes where the growth effect becomes clearly positive and more dispersed, stronger levers are needed to bend the upper tail of the emission distribution. These include the faster electrification of transport and process heat, expansion of clean firm power and system flexibility, and credible early offtake arrangements that accelerate green hydrogen and other abatement options in hard-to-abate activities. Price and tariff reforms that better reflect carbon intensity can reinforce these shifts while protecting vulnerable households through targeted compensation and efficiency support. Since financial integration is consistently emission-reducing across quantiles but becomes more variable at the top end, the policy aim should be to preserve its mitigating role by steering capital toward transition-consistent assets. This can be achieved through taxonomy-aligned disclosure, the rigorous verification of use-of-proceeds, and preferential financing conditions for grid reinforcement, storage, and large-scale efficiency upgrades, combined with prudential guardrails such as emission performance covenants, credible transition plans for major emitters, and financed-emission targets for banks and institutional investors. At the upper end of the distribution, screening mechanisms that avoid lock-in of unabated carbon-intensive projects and blended-finance platforms that channel foreign capital into verified transition investments become especially important.

Social integration shows near-neutral average effects but clear state dependence, so urban and behavioral policy should tilt connectivity toward conservation rather than rebound consumption. In fast-growing cities, inclusion and public space investments should be paired with transit-first planning, congestion and parking management, and strict appliance and cooling standards supported by targeted rebates. During cleaner periods, when stronger connectedness can scale household demand, time-of-use pricing and transparent information on the real-time grid carbon intensity can shape consumption timing and intensity. As emissions rise, social networks can be mobilized for community retrofits, neighborhood solar-plus-storage, and demand response participation. Finally, because knowledge management is associated with higher emissions across quantiles, digitalization and KM support should be tied to verified reductions in emission intensity that exceed any utilization gains, reinforced by clean-power sourcing, electrified process upgrades, internal carbon pricing, and absolute emission controls where needed, alongside innovation pipelines for grid flexibility, clean process heat, and circular industrial solutions.

5.3. Managerial Implications

For managers in Saudi Arabia’s energy-intensive firms and large service providers, the evidence implies that operational and investment decisions should be state-contingent rather than guided by average effects, since economic growth tends to raise emissions in both low- and high-emission regimes, while financial integration generally supports emission reductions, and social integration is mostly near-neutral but context-dependent. In lower-emission periods, firms can expand activity without triggering a sharp rise in CO2 by securing clean electricity through long-term procurement, enforcing high-efficiency operating setpoints for cooling and process systems, and tightening integrity and maintenance programs to minimize methane leakage, flaring, and unplanned outages. Under typical conditions where the growth effect is close to neutral, the focus should be on preventing future lock-in by electrifying new capacity by design, aligning procurement and supplier requirements with forthcoming carbon constraints, and prioritizing efficiency and digital upgrades that deliver measurable intensity reductions. In higher-emission periods, managers should implement predefined flexibility playbooks that shift or curtail noncritical loads, dispatch storage and demand response, reschedule maintenance to reduce system stress, and scale back the most carbon-intensive units first, while accelerating electrification of transport fleets and process heat where feasible. Across all regimes, governance should rely on simple, auditable triggers and KPIs, such as the emission intensity, energy intensity, methane performance, and share of clean electricity, supported by internal carbon prices in capital budgeting, ESG-linked financing structures that reward verified reductions, and knowledge management routines that are tied to independently verifiable intensity improvements so that learning and digitalization do not translate into rebound-driven emission increases.

5.4. Limitations of Study and Future Directions

This study has limitations that also point to future research. First, focusing on Saudi Arabia limits the generalizability, so extending the framework to GCC or MENA samples would test whether the state-dependent patterns hold more broadly. Second, using CO2 emissions as the sole proxy for environmental sustainability misses wider ecological pressures, so future work should add indicators such as the ecological footprint and load capacity factors. Third, quarterly macro-proxies for knowledge management, social integration, and financial integration may mask sector and firm heterogeneity, so richer sectoral or firm-level measures and multiple environmental metrics would strengthen inference. Finally, although the quantile approach captures nonlinear and regime-contingent links, the observational design constrains causal interpretation and may not fully reflect structural breaks, so regime-switching or time-varying quantile models with explicit break handling would be valuable.

Author Contributions

A.K. and H.Y.A. wrote the entire manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adebayo, T.S.; Ozsahin, D.U.; Olanrewaju, V.O.; Uzun, B. Decoding the environmental role of nuclear and renewable energy consumption: A time-frequency perspective. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2025, 223, 111660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahko, J.; Alola, A.A. The effects of climate change technology spillovers on carbon emissions across European countries. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngoc Huynh, H.T.; Thanh Nguyen, N.T.; Vo, N.N.Y. The influence of knowledge management, green transformational leadership, green organizational culture on green innovation and sustainable performance: The case of Vietnam. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2024, 10, 100436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weina, A.; Yanling, Y. Role of Knowledge Management on the Sustainable Environment: Assessing the Moderating Effect of Innovative Culture. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 861813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Jiang, P.; Murshed, M.; Shehzad, K.; Akram, R.; Cui, L.; Khan, Z. Modelling the dynamic linkages between eco-innovation, urbanization, economic growth and ecological footprints for G7 countries: Does financial globalization matter? Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 70, 102881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akadiri, S.S.; Akpan, U.; Aladenika, B.; Adebayo, T.S. Asymmetric effect of financial globalization on carbon emissions in G7 countries: Fresh insight from quantile-on-quantile regression. Energy Environ. 2023, 34, 1285–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack-Vergara, Y.L. Sustainability knowledge management through Benchmarking: The case of CO2 emissions from cement production: Gestão do conhecimento em sustentabilidade através de Benchmarking: O caso das emissões de CO2 da produção de cimento. Stud. Environ. Anim. Sci. 2022, 3, 693–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbass, K.; Amin, N.; Khan, F.; Begum, H.; Song, H. Driving sustainability: The nexus of financial development, economic globalization, and renewable energy in fostering a greener future. Energy Environ. 2025, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Ramzan, M.; Hafeez, M.; Ullah, S. Green innovation-green growth nexus in BRICS: Does financial globalization matter? J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hayali, I.A.; Sultan, W.H.; Al-Hayali, Y.G. The Role of Certain Knowledge Management Processes in Improving Environmental Sustainability: An Exploratory Study of the Opinions of a Sample of Employees in the Iron and Steel Company in Mosul. J. Port Sci. Res. 2024, 7, 352–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xu, H.; Lyu, Y. Emission reduction technologies for shipping supply chains under carbon tax with knowledge sharing. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2023, 246, 106869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baratta, A.; Cimino, A.; Longo, F.; Solina, V.; Verteramo, S. The Impact of ESG Practices in Industry with a Focus on Carbon Emissions: Insights and Future Perspectives. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, T.S. Transforming Environmental Quality: Examining the Role of Green Production Processes and Trade Globalization through a Kernel Regularized Quantile Regression Approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 501, 145232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, W.M.; Levinthal, D.A. Absorptive Capacity: A New Perspective on Learning and Innovation. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; van der Linde, C. Toward a New Conception of the Environment-Competitiveness Relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, P.M. Endogenous Technological Change. J. Polit. Econ. 1990, 98, S71–S102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, H.D. A view from the macro side: Rebound, backfire, and Khazzoom–Brookes. Energy Policy 2000, 28, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keck, M.E.; Sikkink, K.A. Activists beyond Borders: Advocacy Networks in International Politics; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-0-8014-7128-5. [Google Scholar]

- Antweiler, W.; Copeland, B.R.; Taylor, M.S. Is Free Trade Good for the Environment? Am. Econ. Rev. 2001, 91, 877–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, G.M.; Krueger, A.B. Economic Growth and the Environment. Q. J. Econ. 1995, 110, 353–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smuts, H.; Merwe, A. van der From dark data to insight: The role of knowledge management in promoting digital decarbonisation. S. Afr. J. Inf. Manag. 2025, 27, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Wang, Y. Does enterprise green innovation contribute to the carbon emission reduction? Evidence from China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1519258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Qin, Q.; Yang, Y. The Impact of Green Innovation on Carbon Emissions: Evidence from the Construction Sector in China. Energies 2023, 16, 4529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimian, G.C.; Maftei, M.; Jablonský, J.; Marin, E.; Olaru, S.M. The Influence of Digitalization on Greenhouse Gas Emissions in European Union. The Analysis of Mediating Effect of Renewable Energy Consumption. J. Knowl. Econ. 2025, 2, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldieri, L.; Bruno, B.; Lorente, D.B.; Paolo Vinci, C. Environmental innovation, climate change and knowledge diffusion process: How can spillovers play a role in the goal of sustainable economic performance? Resour. Policy 2022, 79, 103021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destek, M.A. Investigation on the role of economic, social, and political globalization on environment: Evidence from CEECs. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2020, 27, 33601–33614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Khan, S.; Ali, A.; Bhattacharya, M. The Impact Of Globalization On CO2 Emissions In China. Singap. Econ. Rev. 2017, 62, 929–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.B.; Saleem, H.; Shabbir, M.S.; Huobao, X. The effects of globalization, energy consumption and economic growth on carbon dioxide emissions in South Asian countries. Energy Environ. 2022, 33, 107–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaies, B.; Nakhli, M.S.; Sahut, J.-M. What are the effects of economic globalization on CO2 emissions in MENA countries? Econ. Model. 2022, 116, 106022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wu, W.; Yao, P. Assessing the financial efficiency of healthcare services and its influencing factors of financial development: Fresh evidences from three-stage DEA model based on Chinese provincial level data. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 21955–21967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, S.; Ozturk, I.; Majeed, M.T.; Akram, R. Globalization and CO2 emissions in the presence of EKC: A global panel data analysis. Gondwana Res. 2022, 106, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekun, F.V.; Ozturk, I. Economic globalization and ecological impact in emerging economies in the post-COP21 agreement: A panel econometrics approach. Nat. Resour. Forum 2025, 49, 637–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulucak, R.; Danish; Ozcan, B. Relationship between energy consumption and environmental sustainability in OECD countries: The role of natural resources rents. Resour. Policy 2020, 69, 101803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustofa, H.Z. The relationship between economic growth, population, FDI, globalization, and CO2 emissions in OIC member countries. Environ. Res. Technol. 2025, 8, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.; Yang, L.; Lahr, M.L. Globalization’s effects on South Asia’s carbon emissions, 1996–2019: A multidimensional panel data perspective via FGLS. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gygli, S.; Haelg, F.; Potrafke, N.; Sturm, J.-E. The KOF Globalisation Index—Revisited. Rev. Int. Organ. 2019, 14, 543–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WDI World Bank Open Data. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- OWID OWID Homepage. Our World Data. 2025. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/ (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Hainmueller, J.; Hazlett, C. Kernel Regularized Least Squares: Reducing Misspecification Bias with a Flexible and Interpretable Machine Learning Approach. Polit. Anal. 2014, 22, 143–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raggad, B. Carbon dioxide emissions, economic growth, energy use, and urbanization in Saudi Arabia: Evidence from the ARDL approach and impulse saturation break tests. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 14882–14898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agboola, M.O.; Bekun, F.V.; Joshua, U. Pathway to environmental sustainability: Nexus between economic growth, energy consumption, CO2 emission, oil rent and total natural resources rent in Saudi Arabia. Resour. Policy 2021, 74, 102380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samargandi, N. Sector value addition, technology and CO2 emissions in Saudi Arabia. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 78, 868–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, M.M.A.; Elroukh, A.W. The impact of globalization on environmental sustainability in Saudi Arabia. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2025, 12, 101714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Baloch, M.A.; Danish, null; Meng, F.; Zhang, J.; Mahmood, Z. Nexus between financial development and CO2 emissions in Saudi Arabia: Analyzing the role of globalization. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2018, 25, 28378–28390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acheampong, A.O. Modelling for insight: Does financial development improve environmental quality? Energy Econ. 2019, 83, 156–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.