Abstract

Accurate modeling and parameter estimation of photovoltaic (PV) systems are vital for advancing energy sustainability and achieving global decarbonization goals. Reliable PV models enable better integration of solar resources into smart grids, improve system efficiency, and reduce maintenance costs. This aligns with the vision of sustainable energy systems that combine intelligent optimization with environmental responsibility. The recently introduced Black-Winged Kite Algorithm (BWKA) has shown promise by emulating the predatory and migratory behaviors of black-winged kites; however, it still suffers from issues of slow convergence, limited population diversity, and imbalance between exploration and exploitation. To address these limitations, this paper proposes an Improved Black-Winged Kite Algorithm (IBWKA) that integrates two novel strategies: (i) a Soft-Rime Search (SRS) modulation in the attacking phase, which introduces a smoothly decaying nonlinear factor to adaptively balance global exploration and local exploitation, and (ii) a Quadratic Interpolation (QI) refinement mechanism, applied to a subset of elite individuals, that accelerates local search by fitting a parabola through representative candidate solutions and guiding the search toward promising minima. These dual enhancements reinforce both global diversity and local accuracy, preventing premature convergence and improving convergence speed. The effectiveness of the proposed IBWKA in contrast to the standard BWKA is validated through a comprehensive experimental study for accurate parameter identification of PV models, including single-, double-, and three-diode equivalents, using standard datasets (RTC France and STM6_40_36). The findings show that IBWKA delivers higher accuracy and faster convergence than existing methods, with its improvements confirmed through statistical analysis. Compared to BWKA and others, it proves to be more robust, reliable, and consistent. By combining adaptive exploration, strong diversity maintenance, and refined local search, IBWKA emerges as a versatile optimization tool.

1. Introduction

Photovoltaic (PV) devices convert sunlight into electrical energy, and their efficiency largely depends on the properties of the semiconductor materials used. Among these, silicon, produced in monocrystalline, polycrystalline, and amorphous forms, remains the most widely adopted because it offers a good trade-off between performance, cost, and durability. These material differences directly affect power output, long-term reliability, and the way solar systems are managed. To accurately assess and optimize PV performance, it is crucial to model key electrical parameters such as reverse saturation currents, ideality factors, series and shunt resistances, and photocurrent generation [1]. The nonlinear electrical behavior of PV cells is commonly captured using equivalent circuit models, which effectively replicate their current–voltage (I–V) characteristics under real-world conditions. The one-diode model (One-DM) [2,3], two-diode model (Two-DM), three-diode model (Three-DM) [4], and the more recently proposed four-diode model (Four-DM) [5] are among the most widely adopted approaches. Each successive model increases in complexity by introducing additional diode branches, thereby improving its ability to replicate physical effects such as carrier recombination, diffusion currents, and junction leakage mechanisms. This refinement improves the accuracy of the models, allowing them to more faithfully represent the real behavior of PV systems and deliver reliable performance predictions across diverse operating conditions [6].

A wide array of optimization techniques has been proposed in the literature for estimating the parameters of PV models. In [7], a Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) framework was introduced to advance the accuracy and computational efficiency of PV parameter estimation. This work integrated the five-parameter circuit with Giddings–LaChapelle theory. A PSO-based parameter extraction approach was applied experimentally validated on different PV technologies with application on a 12-MW PV farm. Despite this PSO application developed for a multi-zone PV model under nonuniform snow and shading conditions, the comparative assessments with other methods are ignored and the implementations are limited for simple One-DM equivalent circuit. In [8], the Lightning Attachment Procedure Optimization (LAPO) algorithm was applied through a three-stage framework: (i) initial parameter extraction using conventional methods, (ii) determination of partial uncertainties, and (iii) calculation of instantaneous parameters. This strategy addressed the One-DM while explicitly considering measurement uncertainties. The validation results confirmed LAPO’s effectiveness in managing uncertain parameters, offering improved robustness compared to traditional approaches. Nonetheless, its use remained restricted to the simplified One-DM, limiting its applicability for more complex PV models. In [9], a modified Differential Evolution (DE) version has been described by exploiting directional cues extracted from differential vectors within the evolving population. Rather than depending exclusively on random perturbations, the algorithm involved directional information to steer candidate solutions more intelligently through the search space. This guided navigation enhances its ability to probe different regions effectively, reducing the chance of premature convergence and ensuring more reliable optimization outcomes.

In [10], attention was shifted to the Three-DM model, which incorporated three diodes to better capture recombination losses and nonlinear effects within the p–n junction. To manage this added complexity, an enhanced Improved Whale Optimization Optimizer (IWO) was introduced. This variant integrated a stochastic coefficient vector along with two adaptive search strategies based on random agents, enabling a stronger balance between exploration and exploitation. Validation using real-world datasets from commercial PV modules such as KC200GT and MSX-60 demonstrated the algorithm’s effectiveness in precisely estimating the nine unknown parameters of the Three-DM, highlighting its potential for high-fidelity PV modeling. In [11], an Optimizer Leveraging Multiple Initial Populations was specifically developed to address the difficulties of multimodal optimization and parameter estimation in PV models. It employed a strategy of initializing four distinct populations to ensure diversity at the start of the search. These populations were later merged into a single elite pool, enabling a more comprehensive exploration of the solution space and significantly lowering the risk of premature convergence to suboptimal solutions. In [12], the Flower Pollination Optimization (FPO) algorithm has also been employed for PV parameter estimation, with particular emphasis on the Three-DM model. Findings revealed that FPO delivered superior performance in this configuration compared to its application on the simpler One-DM and Two-DM models. This enhancement stems from FPO’s intrinsic strategy of alternating between local and global pollination within a single update step, thereby improving accuracy in complex PV models. In [13], the Adaptive Manta Ray Foraging Optimizer (AMRFO) was developed by introducing success-history-based parameter adaptation for tuning the control parameter and a selection strategy based on top-performing candidates to enhance population diversity. Applied to PV parameter extraction, AMRFO outperformed seven competing algorithms across six experimental datasets, achieving low mean error, high success rates, and computational efficiency. However, despite its advantages, the reported results indicated that for certain benchmark cases such as the RTC France cell, the mean error values remained significantly higher than those achieved by other recently developed approaches [14]. In this context, several metaheuristic techniques were applied in PV parameter extraction seeking for enhanced convergence speed and precision such as the differential evolution algorithm [15], the Black Widow Optimization [16], Kangaroo Escape Optimizer [17], hybrid Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO) versions [18,19], snake optimization metaheuristic algorithm [20], Kepler optimizer [21], Pontogammarus maeoticus swarm optimizer [22], elephant herding optimization algorithm [23], Chaos Game Optimization [24], Artificial Rabbits Algorithm [25], and Nutcracker Optimization Algorithm [26].

The Black-Winged Kite Algorithm (BWKA) represents a recent advancement in the domain of nature-inspired meta-heuristic optimization techniques, drawing inspiration from the behavioral patterns of black-winged kites (Elanus caeruleus). Introduced in 2024 [27], the BWKA simulates kites’ predation tactics, including hovering, diving attacks, and stochastic adjustments, and their migratory behaviors, involving leader-guided navigation and dynamic environmental adaptations. By mapping these biological processes to computational strategies, BWKA effectively balances global search through dive-like attacks and local refinement via hovering. The BWKA operates through two primary phases: attack and migration. The attack phase mimics the kite’s predatory sequence, where individuals in the population adjust positions based on observed prey. The migration phase involves dynamic group movement under a leader, with replacements if fitter, promoting adaptability and preventing stagnation. In the BWKA, the swarm is guided using a leader strategy, incorporating Cauchy mutation for broader perturbations, especially beneficial in high-dimensional spaces.

Extensive benchmarking has validated BWKA’s efficacy in [27], with testing on CEC-2017 and CEC-2022. Also, its practical has been further evidenced in real applications like tension/compression spring design, welded beam optimization, and pressure vessel problems [27]. The BWKA has inspired numerous variants and applications across diverse fields. In [28], an improved version has been developed with integration of osprey optimization and crossover strategies in order to boost the global search accuracy and local development. Other modifications incorporated Brownian motion for migration, opposition-based learning, and chaotic perturbations, as seen in revamped iterations [29]. In energy systems, the BWKA optimized clustering protocols for Internet of Things (IoT) networks, enhancing energy efficiency in wireless communications [30]. Also, it has been designed for localization in wireless sensor networks by employing modified distance metrics for range-free positioning to enhance the accuracy in dynamic environments [31]. For battery management, a hybrid Kernel extreme machine learning has been optimized by improved BKWA for predicting lithium-ion battery state of health, aiding electric vehicle reliability [32]. Additionally, BKWA variants have been utilized for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) applications for minimizing the energy consumption and collision risks in single or multi-UAV path optimization scenarios [33,34]. In renewable energy, it has been performed for optimal sizing of hybrid systems, balancing cost and performance under uncertain conditions [35]. Healthcare sees its use in predicting patient waiting times via boosted machine learning models, streamlining hospital operations [36]. Additionally, in building energy management, multi-strategy-enhanced BWKA identifies RC parameters for air-conditioning load aggregation, supporting efficient demand response [37].

The Black-Winged Kite Algorithm (BWKA) faces several limitations that have spurred researchers to develop enhanced variants. Primarily, it suffers from premature convergence to local optima, limiting its ability to find global solutions in multimodal or high-dimensional problems [38]. An imbalance between exploration and exploitation often results in inefficient searches, either overly broad or excessively localized [39]. Additionally, slow convergence speeds hinder performance on complex functions, while poor initial population distribution reduces search diversity [36]. Furthermore, the initial population distribution in BWKA resulted in poor uniformity, since random initialisation produced an uneven distribution of solutions, leading to clustering in specific regions of the search space while overlooking others, hence obstructing variety and global search from the outset [32]. This paper proposes an Improved Black-Winged Kite Algorithm (IBWKA) by integrating two novel strategies. A Soft-Rime Search (SRS) modulation is the first that is integrated in the attacking phase, which introduces a smoothly decaying nonlinear factor to adaptively balance global exploration and local exploitation. Also, a Quadratic Interpolation (QI) refinement mechanism is the second which is applied to a subset of elite individuals to accelerate local search by fitting a parabola through representative candidate solutions and guiding the search toward promising minima. The proposed IBWKA and the standard BWKA are developed for accurate parameter identification of PV models.

The key contributions of this study can be summarized as follows:

- A novel IBWKA is proposed integrating SRS modulation for adaptive exploration–exploitation balance and QI refinement for accelerated deterministic local search.

- These dual enhancements directly address BWKA’s limitations of premature convergence, poor diversity, and slow convergence in complex multimodal problems.

- Comprehensive validation on two benchmark PV datasets using one-, two-, and three-diode models.

- Demonstrated superior accuracy and robustness of IBWKA over classical and modern optimization algorithms through statistical metrics, histograms, convergence curves, and error analysis.

- Provided practical evidence that IBWKA yields physically consistent and reliable PV parameter estimations, ensuring its suitability for real-world renewable energy applications.

2. Problem Formulation of PV Parameters Identification

Accurate modeling of PV cells requires identifying unknown parameters of equivalent circuit models. Although the Shockley diode equation is widely applied, practical deviations from ideal behavior, caused by series resistance (Rs), shunt resistance (Rsh), and complex carrier conduction, necessitate refined parameter estimation to ensure reliable performance prediction.

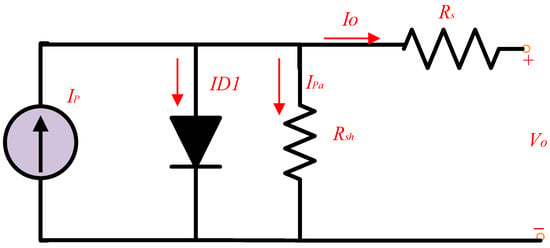

2.1. One-DM

The single-diode model represents a solar cell as a current source (photocurrent, Ip), a diode (D1), and two resistances (Rs and Rsh). The diode’s ideality factor (α1) accounts for non-ideal conduction effects, while the reverse saturation current (IR1) models leakage behavior. Based on Kirchhoff’s Current Law, the output current can be expressed as a nonlinear function of output voltage (Vo), cell temperature (T), and fundamental constants (k and q).

In this model, five parameters must be estimated from measured I–V data which are:

The equivalent circuit of the single-diode model (One-DM) is illustrated in Figure 1. Based on Kirchhoff’s Current Law (KCL), the output current of the PV cell can be formulated as a nonlinear function of the output voltage (Vo) and the reverse saturation current (IR1), as expressed in Equation (2) [40].

where Thv is the thermal voltage (Equation (2)), which is calculated using the cell temperature (T) and Boltzmann’s constant (k = 1.3806503 × 10−23 J/K), while the Shockley diode equation incorporates the elementary charge (q = 1.60217646 × 10−19 C) to account for electron charge effects.

Figure 1.

One-DM equivalent circuit.

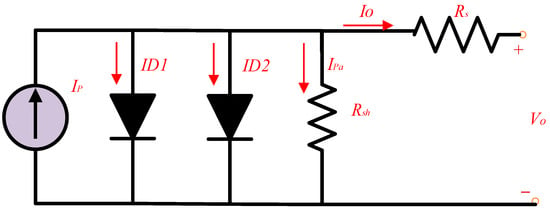

2.2. Two-DM

The equivalent circuit of the two-DM is shown in Figure 2. In this representation, diode D1 models the diffusion current of minority carriers, while diode D2 accounts for recombination effects within the space-charge region of the p–n junction. The associated reverse saturation currents are denoted as IR1 (diffusion) and IR2 (recombination). Applying KCL yields the current–voltage relationship expressed in Equation (4).

Figure 2.

Two-DM equivalent circuit.

In this model, the additional diode introduces two more parameters, alongside those already present in the One-DM. Thus, a total of seven parameters must be extracted:

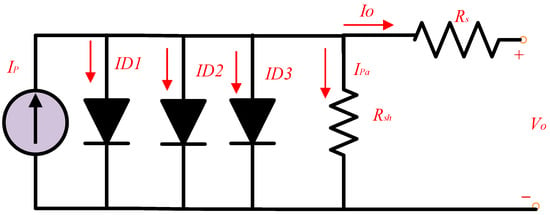

2.3. Three-DM

The three-DM, illustrated in Figure 3, extends the previous configurations by introducing a third diode (D3) in parallel with D1 and D2. This additional diode further accounts for complex recombination and leakage effects not captured by simpler models. Applying KCL provides the current–voltage relation expressed in Equation (6).

Figure 3.

Three-DM equivalent circuit.

In this formulation, α3 and IR3 represent the ideality factor and reverse saturation current of the third diode, respectively. Consequently, the Three-DM involves nine parameters to be identified:

2.4. PV Modules Handling

The mathematical expressions of the single-, double-, and three-diode models can be extended to represent PV modules consisting of Ns series-connected cells and Npa parallel-connected cells. By incorporating these scaling factors, the final formulations of the models are obtained as shown in Equations (8)–(10).

2.5. Objective Model

The accuracy of parameter estimation is evaluated using the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) criterion, defined as [41]:

where MP denotes the number of experimental data points, and are the measured and calculated currents at a given voltage, and X represents a candidate solution containing the estimated PV model parameters. Minimizing RMSE ensures the best possible fit between the simulated and measured I–V characteristics of the PV cell or module.

3. Proposed IBWKA with a Soft-Rime and Quadratic Interpolation

3.1. Step 1: Initialization

The BWKA optimization process begins by creating a starting population of search agents, called black-winged kites (Bwi). These candidate solutions are randomly distributed across the permissible range of the design variables to ensure wide exploration of the search domain. The position of the i-th agent is expressed as:

where NBw is the population size, Dim indicates the dimension, Lpk and Upk are the minimum and maximum limits of the k-th variable, is a random vector uniformly distributed in [0, 1]. After generating the population, each candidate is evaluated using the objective function to compute its fitness (Fiti). The best-performing solution with the lowest fitness value (FitBest) is then designated as the leader (BwLeader), which will guide the swarm in subsequent iterations.

3.2. Attacking Phase in BWKA

This stage simulates the hunting strategy of the black-winged kite, which alternates between hovering to monitor its prey and executing a sudden dive attack. The position of the i-th kite in the k-th dimension at the next iteration is updated as:

where is the current position; R1 ∈ [0, 1] is a uniformly distributed random value, ρ is a fixed probability parameter (commonly set to 0.9), and α is a nonlinear adaptive factor formulated as:

with It and Itmax being the current and maximum iteration counts. Through this mechanism, two alternative behaviors emerge: (i) Hovering (local search) and (ii) Dive attack (global exploration. When the probability threshold is met in the first scenario, the kite hovers in the air, impacted by wind conditions and prey detection, causing a sinusoidal disruption that pushes solutions outward in random directions, encouraging global exploration and avoiding premature convergence. In the second scenario, when the criterion is not met, the kite simulates a diving attack. The method modifies position via linear perturbation, bringing the solution closer to the present position and aligning with local exploitation. In both situations, the control factor (α) begins big in early iterations, permitting experimental motions, but drops nonlinearly as the algorithm advances, moving focus from global exploration to local exploitation.

3.3. Migration Phase

In this stage, kites adjust their positions through a leader-guided strategy combined with Cauchy perturbations to maintain exploration diversity. The position update is governed by two displacement rules, determined by comparing the fitness of the current individual with that of a randomly selected peer:

where Cy(0,1) is a random number drawn from the Cauchy distribution, Fiti and FitRi denote the fitness of the i-th kite and a randomly chosen reference solution, and β is a nonlinear adaptive coefficient given as:

The formulation enables two search behaviors: explorative migration, where the kite moves away from the leader if a random peer performs better, and exploitative migration, where the kite is drawn towards the leader.

3.4. Boundary Control, Fitness Evaluation and Leader Updating

After updating the positions of the kites, the boundary constraints are checked to ensure that every variable remains within the feasible search domain. This mechanism prevents out-of-range solutions by projecting any exceeded values back into the permissible limits:

Next, the fitness of each updated solution () is evaluated, producing a new fitness value (Fit_newi). A greedy selection rule is then applied and if the new solution is superior, it replaces the old one. Otherwise, the previous solution is retained:

At the population level, the BWKA also checks whether any improved candidate outperforms the current global leader. If so, the leader is immediately updated to this superior solution:

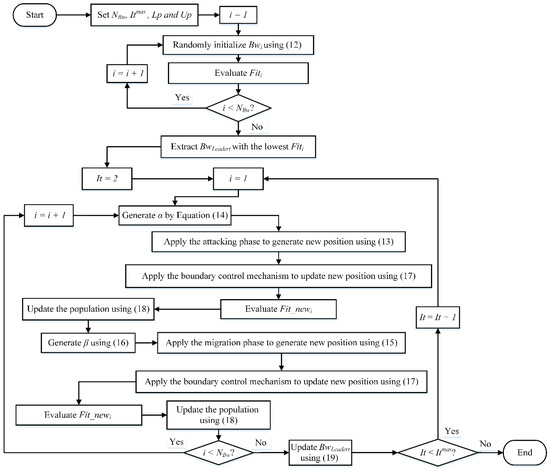

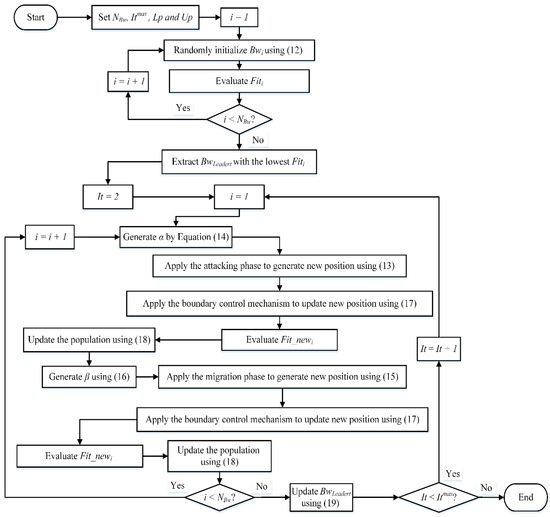

This cycle of boundary enforcement, evaluation, and leader replacement continues iteratively until the termination condition is satisfied. At the end of the process, the final leader and its fitness value are returned as the best solution found by the algorithm. Figure 4 displays the main steps of the BWKA.

Figure 4.

Main steps of standard BWKA.

3.5. Proposed Improved BWKA (IBKWA) Version

In the proposed model, dual modifications are inserted onto the standard BKA. The first modification includes the Soft-Rime Search (SRS) strategy [42] to upgrade the attacking behavior of the black Kites which supports the adaptive exploration-exploitation balance. While the migration behavior is preserved, the second modification includes the Quadratic Interpolation (QI) strategy which is added after in order to further support the deterministic local refinement [43].

3.5.1. Modified Attacking Behavior with SRS Modulation

In the proposed IBKWA, a Rime factor (δRf) is added that smoothly decays with iterations. This factor is large in the Early iterations, encouraging exploration with strong random perturbations, and it decays smoothly in the Later iterations, reducing randomness and promoting exploitation [44]. This helps balance exploration and exploitation adaptively instead of relying only on fixed probability conditions. Therefore, Equation (13) is modified to be as follows:

where δRf is a nonlinear Rime factor, defined as:

where R3 and R4 refer to random numbers drawn from [0, 1]; round is the round function to approximate the inside term towards the nearest round.

3.5.2. Addition of QI Modulation

The Standard BKA Relies only on attacking and migration operators where no dedicated local refinement mechanism. Therefore, the QI strategy is added to improve the local exploitation by fitting a parabola through three fitness samples and jumping to the estimated minimum [45]. Only a subset of the population (20%) undergoes QI each iteration to avoid heavy computational cost. The proportion of individuals undergoing QI was selected empirically based on preliminary experiments. Several ratios (e.g., 10%, 20%, and 30%) were evaluated to examine the trade-off between solution accuracy and computational cost. Ratios below 20% provided limited refinement benefits, while higher ratios resulted in marginal accuracy improvements at a noticeably increased computational expense. Therefore, selecting 20% achieves an effective balance between convergence enhancement and computational efficiency. This refinement step accelerates convergence once promising regions are found. After the main update via modified attack and migration, a parabolic line search is extracted using QI between the current, the mean and the leader solutions and so the new position based on QI (Bw_QIi) can be evaluated as follows:

where R5 symbolizes random numbers drawn from [0, 1];

where , , and are the positions of the i-th individual, the population centroid, and the current best solution, respectively. Their corresponding fitness values are , , and . Finally, a greedy selection mechanism ensures that only the superior solution is retained:

Through this strategy, QI enhances promising individuals and prevents performance degradation, resulting in a balanced boost in optimization accuracy and convergence stability. Figure 5 displays the main steps of the proposed IBWKA.

Figure 5.

Main steps of proposed IBWKA.

4. Simulation Results

4.1. Case Studies: PV Cell and Module Evaluation

The effectiveness of the proposed IBWKA is validated using two benchmark PV devices: the R.T.C. France solar cell and the STM6_40/36 PV module.

- Case 1 (R.T.C. France cell): This is a commercial silicon-based PV cell tested under standard conditions of 1000 W/m2 irradiance and 33 °C operating temperature. Its key electrical specifications include an open-circuit voltage of 0.5727 V, a short-circuit current of 0.7605 A, and a maximum power point (MPP) defined by 0.4590 V and 0.6755 A.

- Case 2 (STM6_40/36 module): This module consists of 36 series-connected cells [46]. The evaluation is performed under an ambient temperature of 51 °C and irradiance of 1000 W/m2.

The feasible ranges of the electrical parameters to be optimized for the one-, two-, and three-diode models are summarized in Table 1, along with the technical specifications of both devices. These bounds ensure that the extracted parameters remain physically meaningful and consistent with manufacturer data.

Table 1.

Parameter boundaries for RTC France and STM6_40/36 PV modules.

4.2. Applications of R.T.C France PV

The proposed IBWKA is applied to the parameter estimation of the R.T.C. France PV cell, and its performance is compared with the standard BWKA. The task involves extracting the unknown parameters of the three equivalent models investigated (One-DM, Two-DM, and Three-DM). These parameters govern the cell’s electrical characteristics, and their accurate identification is crucial for replicating the measured I–V curves.

Table 2 summarizes the extracted parameters for all three models. Also, the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) are tabulated as additional evaluation metrics. Both BWKA and IBWKA succeed in finding physically consistent solutions that fall within the expected bounds. For the One-DM, the two algorithms deliver nearly identical results across all five parameters, reflecting the relatively simple model structure. However, IBWKA consistently provides refined estimates of diode ideality factors and reverse saturation currents, improving alignment with experimental I–V data as model complexity increases.

Table 2.

Extracted parameter values of the RTC France obtained using the proposed IBWKA.

On the level of objective scores, the RMSE values reported in the table confirm the superiority of IBWKA. While BWKA achieves competitive results, IBWKA attains lower RMSEs for both the Two-DM (9.8249 × 10−4 vs. 9.8281 × 10−4) and Three-DM (9.8250 × 10−4 vs. 9.8435 × 10−4). These improvements are significant in PV modeling, where slight parameter adjustments can strongly affect maximum power prediction and overall accuracy.

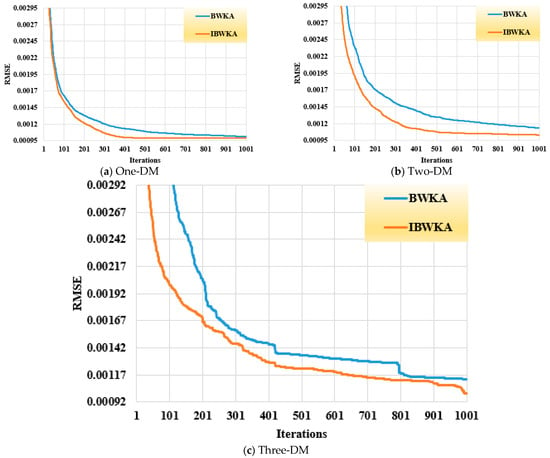

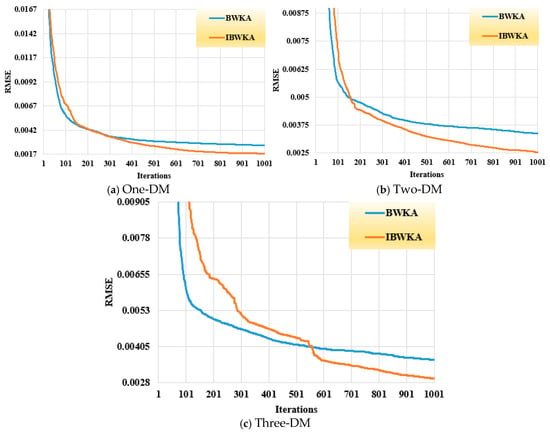

Figure 6 illustrates the average RMSE convergence trends for the three models across 1000 iterations. Concerning the differences observed in the simulation results, the convergence behaviors in Figure 6 reflect the RMSE evolution for different diode models of the R.T.C. France cell. The smoother and faster convergence of IBWKA compared to BWKA highlights its improved exploration–exploitation balance, particularly for higher-dimensional models such as the Three-DM. This stability is particularly visible in the Three-DM, where the optimization landscape is highly nonlinear and prone to premature convergence.

Figure 6.

RMSE convergences of the BWKA and the proposed IBWKA for the R.T.C. France cell considering the three DMs.

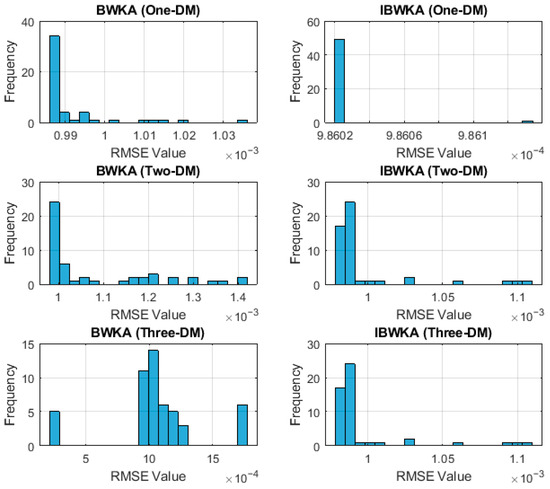

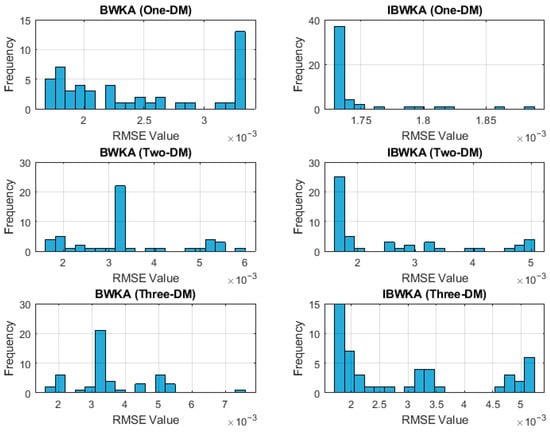

Figure 7 presents the distribution of RMSE values obtained from 50 independent runs for each model. In Figure 7, the vertical axis labeled “Frequency” represents the number of occurrences of RMSE values falling within each predefined RMSE interval. It indicates how often a particular RMSE range appears over the 50 independent executions performed for each algorithm and diode model. The histograms clearly show that IBWKA produces tighter distributions around the minimum RMSE compared to BWKA. For the Three-DM, BWKA’s results are more dispersed, with several runs yielding higher error values above 1.2 × 10−3, while IBWKA maintains a consistent clustering near 9.82 × 10−4. This indicates that IBWKA not only achieves higher accuracy but also demonstrates superior robustness and repeatability across stochastic runs. The accompanying numerical data confirm these observations. BWKA shows greater fluctuations, particularly in the Two-DM and Three-DM, where RMSE values occasionally rise significantly (e.g., 0.00141–0.00175). By contrast, IBWKA’s results remain tightly bounded with minimal variance, underscoring its reliability in handling multimodal and high-dimensional search spaces.

Figure 7.

Histogram of the obtained RMSE values using BWKA and IBWKA for the R.T.C. France cell of the three DMs.

4.3. Comparative Performance on the R.T.C. France PV Cell

To further emphasize the effectiveness of the proposed IBWKA, its performance is benchmarked against a wide spectrum of existing optimization algorithms for the parameter extraction of the R.T.C. France PV cell. The comparisons cover both the One-DM and Two-DM cases.

Table 3 reports the RMSE values obtained by IBWKA alongside numerous classical and recently developed algorithms, including Classified perturbation mutation PSO (CPMPSO), Flexible PSO (FPSO), Enriched Harris Hawks Algorithm (EHHA), hybridized PSO–GWO (PSOGWO), Barnacles Mate Optimizer (BMO), RIME, Multi-Verse Algorithm (MVA), Neighborhood Laplace BMO (NLBMO), Lightning Attachment Procedure Algorithm (LAPA), and Hybrid Firefly and Pattern Search Algorithm (HFPSA). The results reported in Table 3 are the best-known RMSE values extracted from previously published studies, where each algorithm was evaluated using its own optimally tuned parameter settings. As shown, the IBWKA achieves an RMSE of 9.8602 × 10−4, which is lower than the majority of the compared methods. Algorithms such as BMO, PSOGWO, and HFPSA exhibit much higher RMSEs (up to two orders of magnitude larger), indicating less reliable convergence for this problem. Traditional and hybrid methods like MVO, NLBMO, FPSO, and EHHO fall significantly behind, underscoring IBWKA’s ability to efficiently balance exploration and exploitation.

Table 3.

Performance comparison of the proposed IBWKA against the others for the R.T.C. France PV (one-DM).

The analysis is extended in Table 4, where IBWKA is evaluated against advanced algorithms such as the Dwarf Mongoose Optimizer (DMO) [14], RIME, and ESMA. To provide a comprehensive perspective, the table reports not only the minimum RMSE but also statistical measures (median, average, worst, and standard deviation) over 50 independent runs.

Table 4.

Performance comparison of the IBWKA against the others for the R.T.C. France PV module (two-DM).

As shown, the IBWKA attains the best minimum RMSE of 9.8249 × 10−4, slightly outperforming all compared methods. This demonstrates its ability to locate highly accurate parameter solutions even in the more complex Two-DM case involving seven unknowns. It achieves the lowest standard deviation (2.988 × 10−5) among all algorithms, confirming its robustness and reduced variance across stochastic runs. By contrast, ESMA and RIME exhibit much higher variability, indicating susceptibility to local optima or instability. Beyond the minimum error, IBWKA maintains competitive median and average RMSE values. From both Table 3 and Table 4, the results confirm that IBWKA is not only capable of achieving high accuracy but also its improvements are particularly evident in the Two-DM, where parameter dimensionality increases, and many algorithms struggle with premature convergence.

In this regard, Table 5 provides a comparative qualitative overview of the proposed IBWKA, and several recent state-of-the-art optimization algorithms applied to the R.T.C. France solar cell benchmark. As shown, several hybrid algorithms like PSOGWO and HFPSA improve performance using implicit local exploitation, but their mechanisms limit fine-tuned search near the global optimum. In contrast, algorithms such as MVO, RIME, FPSO, and BMO focus on global exploration, yielding only moderate performance. The proposed IBWKA combines adaptive global exploration and deterministic local refinement through SRS and QI, achieving the lowest reported RMSE with enhanced convergence stability. This is notably better than the original BWKA, which lacks local refinement and has higher error rates.

Table 5.

Comparative Overview of IBWKA and Recent Competing Algorithms on the RTC France Cell.

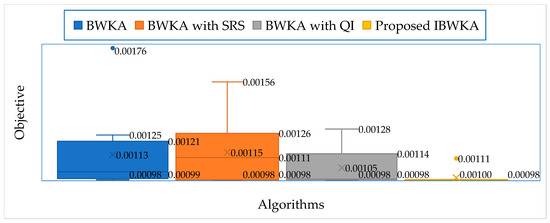

4.4. Ablation Study on the Contributions of SRS and QI Mechanisms

To assess the individual and combined impacts of the proposed SRS and QI mechanisms, an ablation study is conducted in this work. The primary objective of this analysis is to isolate the contribution of each enhancement and to verify that the superior performance of the proposed IBWKA does not stem from incidental effects, but rather from the synergistic integration of both mechanisms. In this study, four algorithmic variants are systematically investigated: (i) the standard BWKA, (ii) BWKA augmented only with the SRS mechanism, (iii) BWKA augmented only with the QI mechanism, and (iv) the proposed IBWKA, which simultaneously integrates both SRS and QI mechanisms.

All variants are applied to the R.T.C. France cell considering the Three-DM. The resulting RMSE distributions are illustrated using boxplots in Figure 8, while a detailed numerical comparison is summarized in Table 6 in terms of minimum, average, maximum, and standard deviation (StD) of RMSE values, along with the relative improvement percentages with respect to the proposed IBWKA.

Figure 8.

RMSE distributions of the BWKA with suggested mechanisms via boxplots.

Table 6.

Ablation study of the proposed IBWKA to assess individual contributions of SRS and QI mechanisms.

From the minimum RMSE perspective, the proposed IBWKA achieves the lowest value of 9.8249 × 10−4, outperforming the standard BWKA, BWKA with SRS only, and BWKA with QI only by 0.188%, 0.091%, and 0.089%, respectively. In terms of average RMSE, the IBWKA records an average RMSE of 9.9514 × 10−4, demonstrating relative improvements of 12.03%, 13.10%, and 5.64% against the standard BWKA, BWKA with SRS, and BWKA with QI, confirming that the combined use of SRS and QI substantially enhances solution quality across repeated runs. The maximum RMSE values further highlight the robustness of the proposed IBWKA. The worst-case RMSE of IBWKA is limited to 1.1094 × 10−3, which corresponds to improvement margins of 36.88%, 28.86%, and 13.48%, respectively, against BWKA, BWKA with SRS, and BWKA with QI. Finally, the proposed IBWKA achieves a remarkably low StD of 3.97 × 10−5, with high stability improvements of 83.34%, 78.59%, and 66.40%, respectively, against BWKA, BWKA with SRS, and BWKA with QI. These findings clearly demonstrate that IBWKA effectively mitigates premature convergence and avoids poor-quality solutions even under unfavorable stochastic conditions.

4.5. Validation Through I–V/P–V Characteristics and Absolute Error Analysis

The accuracy of the proposed IBWKA in parameter estimation is further validated through graphical and numerical comparisons between the measured and simulated characteristics of the R.T.C. France PV cell.

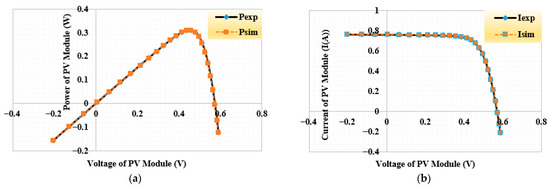

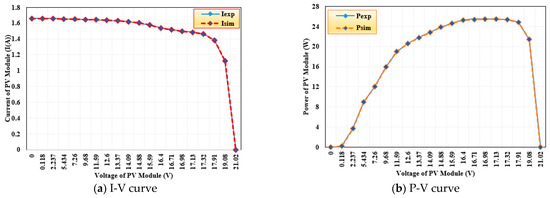

Figure 9a,b illustrate the simulated current–voltage (I–V) and power–voltage (P–V) curves of the Three-DM model obtained using IBWKA alongside the corresponding experimental data. In Figure 9, it is clarified that the results correspond to the R.T.C. France solar cell modeled using the Three-DM, with parameters extracted by the proposed IBWKA under standard test conditions of 1000 W/m2 irradiance and a cell temperature of 33 °C. The extremely close alignment between the two sets of curves indicates that the estimated parameters not only minimize the RMSE statistically but also yield a highly realistic and physically consistent electrical representation of the PV device. This tight overlap across the entire operating range, from short-circuit to open-circuit conditions, demonstrates the method’s capability to preserve both local and global accuracy.

Figure 9.

(a) I-V and (b) P-V curves for the three-DM using the proposed IBWKA of the R.T.C. France cell.

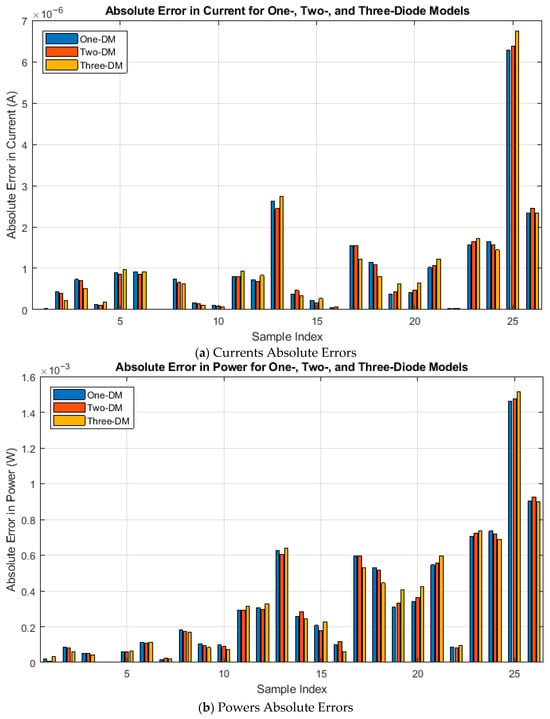

Figure 10a,b provide further insight by presenting the absolute errors between measured and simulated values for current and power, respectively, across the One-DM, Two-DM, and Three-DM cases.

Figure 10.

Errors in currents and powers between the simulated and measured data using IBWKA for R.T.C. France cell.

As shown, the Three-DM achieves the lowest overall error profile, benefiting from its more detailed physical representation of recombination and diffusion mechanisms. From Figure 10a, the errors remain extremely small, ranging from 7.69 × 10−9 to 6.74 × 10−6 A, which indicates the high precision of the IBWKA in capturing the nonlinear current response of the PV cell. From Figure 10b, the absolute errors in power vary between 2.01 × 10−6 and 1.43 × 10−3 W, which are negligible relative to the rated power of the device. These low deviations confirm that IBWKA not only predicts electrical currents with exceptional fidelity but also accurately models the energy conversion performance, making it reliable for efficiency-oriented PV applications. The peak observed at sample index 25 in Figure 10 corresponds to the operating region around the maximum power point region of the I–V and P–V characteristics. In this region, the current–voltage relationship exhibits strong nonlinearity, and even small deviations in the estimated PV model parameters can lead to relatively larger discrepancies in both current and power values. Consequently, the absolute errors tend to reach their maximum near this operating point rather than at the open-circuit or short-circuit regions. While all three diode-based models achieve commendable accuracy, the Three-DM consistently exhibits the best fit, validating the value of incorporating additional recombination pathways in complex PV modeling.

4.6. Applications for STM6_40_36 PV Module

The proposed IBWKA is further validated using the STM6_40/36 PV module, a system comprising 36 series-connected cells. As in the previous case, the optimization is performed for the One-DM, Two-DM, and Three-DM representations, which require five, seven, and nine unknown parameters, respectively. The optimized parameter values obtained by the original BWKA and the proposed IBWKA are summarized in Table 7. As shown, both BWKA and IBWKA converge to nearly identical parameter sets, reflecting reliability in capturing the physical behavior of the PV module. For the One-DM, both algorithms achieve the same RMSE of 1.7298 × 10−3, while for the Two-DM and Three-DM, IBWKA slightly outperforms BWKA, reaching 1.6982 × 10−3 and 1.7004 × 10−3, respectively.

Table 7.

Extracted parameter values of the STM6_40_36 PV module obtained using the IBWKA.

To further assess robustness, Table 8 presents the statistical analysis over multiple independent runs. As shown, the IBWKA consistently matches or slightly improves the best-case RMSE compared to BWKA across all three models. Considering the average RMSE, the IBWKA exhibits a marked reduction in average RMSE values (e.g., 1.7861 × 10−3 vs. 2.6020 × 10−3 in One-DM, and 2.9424 × 10−3 vs. 3.5847 × 10−3 in Three-DM), highlighting its superior reliability in repeated trials. For the worst-case scenarios, even under less favorable initial conditions, IBWKA yields substantially lower worst-case RMSE values, thereby avoiding catastrophic convergence failures common in BWKA. Moreover, the standard deviation values achieved by IBWKA are consistently lower than those of BWKA in the One-DM case (1.6260 × 10−4 vs. 8.3251 × 10−4), in the Two-DM case (1.1522 × 10−3 vs. 1.295 × 10−3), in the Three-DM case (1.2184 × 10−3 vs. 1.26 × 10−3), reflecting greater convergence stability. These results confirm that IBWKA maintains accuracy not only for single-cell studies but also when extended to module-level applications.

Table 8.

Statistical indices of BWKA and IBWKA for STM6_40_36 PV module.

Moreover, Figure 11 illustrates the average RMSE convergence profiles of BWKA and IBWKA for the One-DM, Two-DM, and Three-DM cases of the STM6_40/36 PV module over 1000 iterations. As shown, for the One-DM and Two-DM, the proposed IBWKA consistently achieves a steeper descent in RMSE values during the early and middle phases of the optimization process. This indicates its improved exploration capability, allowing it to rapidly identify promising regions of the solution space. For the Three-DM, the IBWKA demonstrates greater exploitation in the second half of iterations and finally it consistently maintains a lower overall error throughout the optimization run. Also, the curve intersection observed at a certain iteration is attributed to the dynamic interaction between exploration and exploitation phases. In the early iterations, enhanced exploration mechanisms may temporarily yield similar or overlapping error levels across models. As optimization progresses, the IBWKA consistently outperforms the baseline algorithm and stabilizes at lower error levels. This intersection reflects transitional behavior during the shift from global exploration to local exploitation.

Figure 11.

RMSE convergences of BWKA and IBWKA for the STM6_40_36 PV module considering the three DMs.

To evaluate the robustness of the proposed IBWKA, Figure 12 presents the histograms of RMSE values obtained over 50 independent runs for the One-DM, Two-DM, and Three-DM of the STM6_40/36 module. As shown, the proposed IBWKA declares tighter clustering. Across all three diode-based models, IBWKA produces a narrow concentration of RMSE values around the minimum (≈1.18 × 10−3 for the Three-DM). By contrast, BWKA shows wider dispersion with values occasionally rising as high as 3.31 × 10−3 for the One-DM, 3.328 × 10−3 for the 3.33 × 10−3 for 3.33 × 10−3 for the Three-DM. The IBWKA demonstrates greater repeatability by consistently converging close to the best solutions achieving 76%, 48% and 30% for the One-DM, Two-DM, and Three-DM, respectively, across different runs. For higher-dimensional search spaces such as the Three-DM (nine parameters), IBWKA effectively mitigates premature convergence and avoids local optima.

Figure 12.

Histogram of the obtained RMSE by BWKA and IBWKA for the STM6_40_36 PV module of the three DMs.

In addition to the statistical results, Figure 13a,b compares the experimental and simulated I–V and P–V characteristics of the STM6_40/36 module for the Three-DM model using IBWKA. In this figure, the STM6_40/36 PV module of 36 series-connected cells is addressed under an irradiance of 1000 W/m2 and an operating temperature of 51 °C, using the same Three-DM formulation and IBWKA-derived parameters. The curves show a near-perfect overlap, confirming that the parameters extracted by IBWKA accurately reproduce the real-world electrical behavior of the module. This alignment extends across the entire operating range, from short-circuit current to open-circuit voltage, as well as at the maximum power point. The close match between experimental and simulated results demonstrates IBWKA’s ability to generalize from cell-level studies (R.T.C. France) to more complex module-level configurations (STM6_40/36).

Figure 13.

I–V and P–V curves of experimental and simulated results for TDM of STM6_40_36 PV module.

5. Conclusions

This study introduced an IBWKA for accurate parameter estimation of PV models, including single-diode (One-DM), double-diode (Two-DM), and triple-diode (Three-DM) equivalents. The proposed IBWKA incorporated two novel modifications into the standard BWKA framework. First, SRS strategy adaptively modulates exploration and exploitation through a nonlinear decay factor, ensuring a gradual transition from broad global search to refined local exploitation. Second, QI mechanism, applied to a subset of the population, which provides deterministic local refinement and accelerates convergence in promising regions. Also, an ablation study is conducted to assess the individual impacts of the proposed SRS and QI mechanisms.

5.1. Main Findings

The effectiveness of IBWKA was validated on two benchmark datasets: the R.T.C. France cell and the STM6_40/36 PV module, considering one-, two-, and three-diode models. The ablation analysis indicated that IBWKA achieves the lowest minimum, average, maximum RMSE and standard deviation, highlighting the IBWKA’s robustness and stability, with enhancements reducing premature convergence and ensuring better solution quality under various conditions. For the RTC France cell, across all scenarios, the proposed IBWKA outperformed the standard BWKA and various advanced optimizers in accuracy, stability, and robustness across all scenarios. For the STM6_40/36 module, IBWKA similarly secured minimal RMSE across all models, confirming its capacity to deliver physically meaningful and precise parameter extraction. The statistical indices highlighted IBWKA’s remarkable stability. Additionally, histograms of RMSE values demonstrated that IBWKA exhibits tightly clustered distributions around global minima, while BWKA displays broader dispersions with occasional high-error outliers, demonstrating its robustness in high-dimensional and multimodal search spaces. Moreover, visual comparisons between simulated and experimental I–V and P–V curves confirmed the fidelity of the IBWKA-derived models, with an almost perfect overlap. These results demonstrate IBWKA’s ability to capture the real electrical behavior of PV systems with high reliability.

5.2. Limitations of the Proposed IBWKA and Future Work

Despite the strong performance of the proposed IBWKA, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, sensitivity to initialization remains inherent to population-based metaheuristics. Although the designed incorporated SRS enhances early exploration and mitigates poor initial distributions, highly clustered or unfavorable initial populations may still slow convergence, particularly in optimization problems including high-dimensional variables. Second, the introduction of the proposed QI refinement increases the computational overhead per iteration. While QI is applied only to a limited subset of elite individuals to control complexity, the overall computational cost of IBWKA is moderately higher than that of the standard BWKA. Finally, although IBWKA demonstrates robust performance on standard benchmark PV datasets, its effectiveness may degrade in highly constrained, discontinuous, or dynamically changing optimization environments, where frequent reinitialization or adaptive parameter tuning would be required.

Addressing these limitations represents promising directions for future research which can be mitigated through adaptive population initialization, dynamic control of QI frequency, computational cost reduction, and extension to dynamic or real-time optimization. Also, future work can be conducted by reimplementing strong recent optimizers, such as the Resistance–Capacitance (RC) optimizer [57], hybrid butter–flower algorithm [58], Wave Optics Optimizer (WOO) [59], KangarooEscape Optimizer (KEO) [60], Centered Collision Optimizer (CCO) [61], and traffic jam optimizer [62] under identical parameter bounds, population sizes, and stopping criteria.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.S.; Methodology, A.M.S.; Software, A.M.S.; Validation, S.Z.A.; Formal analysis, S.Z.A.; Investigation, S.Z.A.; Data curation, A.M.S.; Writing—original draft, A.M.S.; Writing—review & editing, S.Z.A.; Visualization, A.M.S.; Supervision, S.Z.A.; Funding acquisition, S.Z.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University for funding this research work through the project number (PSAU/2025/01/35267).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, X.; Wang, S.; He, K. Parameter estimation of various PV cells and modules using an improved simultaneous heat transfer search algorithm. J. Comput. Electron. 2024, 23, 584–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidaighbi, S.; Elyaqouti, M.; Hmamou, D.B.; Saadaoui, D.; Assalaou, K.; Arjdal, E. A new hybrid method to estimate the single-diode model parameters of solar photovoltaic panel. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2022, 15, 100234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piliougine, M.; Guejia-Burbano, R.A.; Petrone, G.; Sánchez-Pacheco, F.J.; Mora-López, L.; Sidrach-de-Cardona, M. Parameters extraction of single diode model for degraded photovoltaic modules. Renew. Energy 2021, 164, 674–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajetunmobi, O.; Khan, T.A.; Rizvi, S.A.A.; Ali, R.H. Improved parameter estimation of triple-diode photovoltaic systems. J. Comput. Electron. 2025, 24, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saripalli, B.P.; Gamgula, B.; Ravilisetty, R.; Kumar, P.; Singh, G.; Singh, S. Advanced parameter extraction optimization technique for the four-diode model approach. E-Prime—Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 2024, 10, 100861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbassi, R.; Abbassi, A.; Jemli, M.; Chebbi, S. Identification of unknown parameters of solar cell models: A comprehensive overview of available approaches. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 90, 453–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khenar, M.; Taheri, S.; Cretu, A.M.; Hosseini, S.; Pouresmaeil, E. PSO-based modeling and analysis of electrical characteristics of photovoltaic module under nonuniform snow patterns. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 197484–197498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben, R. Messaoud Extraction of uncertain parameters of a single-diode model for a photovoltaic panel using lightning attachment procedure optimization. J. Comput. Electron. 2020, 19, 1192–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Wang, K.; Tao, S.; Jin, T.; Dai, H.; Cheng, J. A state-of-the-art differential evolution algorithm for parameter estimation of solar photovoltaic models. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 230, 113784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Wang, K.; Yao, Y.; Zhu, M.; Zhuang, L.; Chen, H.; Li, J.; Yan, L.; Gao, S. Parameter Adaptive Manta Ray Foraging Optimization for Global Continuous Optimization Problems and Parameter Estimation of Solar Photovoltaic Models. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2025, 18, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choulli, I.; Elyaqouti, M.; Saadaoui, D.; Lidaighbi, S.; Elhammoudy, A.; Abazine, I.; Ydir, B. Mitigating local minima in extracting optimal parameters for photovoltaic models: An optimizer leveraging multiple initial populations (OLMIP). Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2024, 92, 367–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chellaswamy, C.; Taha; Shaji, M.; Rao, R.Y.; Jawwad, M.; Sharma, G. A Novel Optimization Method for Parameter Extraction of Industrial Solar Cells. In Proceedings of the 2019 Innovations in Power and Advanced Computing Technologies, i-PACT 2019, Vellore, India, 22–23 March 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premkumar, M.; Jangir, P.; Sowmya, R. Parameter extraction of three-diode solar photovoltaic model using a new metaheuristic resistance–capacitance optimization algorithm and improved Newton–Raphson method. J. Comput. Electron. 2023, 22, 439–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, G.; Smaili, I.H.; Almalawi, D.R.; Ginidi, A.R.; Shaheen, A.M.; Elshahed, M.; Mansour, H.S. Dwarf Mongoose Optimizer for Optimal Modeling of Solar PV Systems and Parameter Extraction. Electronics 2023, 12, 4990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Ji, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, W. An Improved Differential Evolution for Parameter Identification of Photovoltaic Models. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhiarasan, M.; Cotfas, D.T.; Cotfas, A. Black Widow Optimization Algorithm Used to Extract the Parameters of Photovoltaic Cells and Panels. Mathematics 2023, 11, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, S.Z.; Shaheen, A.M. A novel kangaroo escape optimizer for parameter estimation of solar photovoltaic cells/modules via one, two and three-diode equivalent circuit modeling. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 32669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premkumar, M.; Shankar, N.; Sowmya, R.; Jangir, P.; Kumar, C.; Abualigah, L.; Derebew, B. A reliable optimization framework for parameter identification of single-diode solar photovoltaic model using weighted velocity-guided grey wolf optimization algorithm and Lambert-W function. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2023, 17, 2711–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janani, C.; Babu, B.C.; Krishnasamy, V. An accurate parameter estimation approach to modeling of solar photovoltaic module using hybrid grey wolf optimization. Optim. Control Appl. Methods 2023, 44, 601–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belabbes, F.; Cotfas, D.T.; Cotfas, P.A.; Medles, M. Using the snake optimization metaheuristic algorithms to extract the photovoltaic cells parameters. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 292, 117373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, G.; Alnami, H.; Ginidi, A.R.; Shaheen, A.M. An improved Kepler optimization algorithm for module parameter identification supporting PV power estimation. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Han, W.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, J.; Cao, S. A photovoltaic parameter identification method based on Pontogammarus maeoticus swarm optimization. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 11, 1204006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.Q.; Liu, C.Y.; Zhao, D.L.; Wang, Y.Q. Parameter identification of photovoltaic cell model based on improved elephant herding optimization algorithm. Soft Comput. 2023, 27, 5797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogar, E. Chaos Game Optimization-Least Squares Algorithm for Photovoltaic Parameter Estimation. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2023, 48, 6321–6340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaili, I.H.; Moustafa, G.; Almalawi, D.R.; Ginidi, A.; Shaheen, A.M.; Mansour, H.S. Enhanced Artificial Rabbits Algorithm Integrating Equilibrium Pool to Support PV Power Estimation via Module Parameter Identification. Int. J. Energy Res. 2024, 8913560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Yu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Tian, L. Parameter Extraction of Solar Photovoltaic Model Based on Nutcracker Optimization Algorithm. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, W.C.; Hu, X.X.; Qiu, L.; Zang, H.F. Black-winged kite algorithm: A nature-inspired meta-heuristic for solving benchmark functions and engineering problems. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shi, B.; Qiao, W.; Du, Z. A black-winged kite optimization algorithm enhanced by osprey optimization and vertical and horizontal crossover improvement. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, S.; Kaliyaperumal, D.; Gharehchopogh, F.S. A revamped black winged kite algorithm with advanced strategies for engineering optimization. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, S.J.; Santhakumar, D. Black-winged kite algorithm-based energy efficient Clustering Protocol for Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 16th International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Communication Networks (CICN), Indore, India, 22–23 December 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Yang, S. Range-free localization algorithm based on modified distance and improved black-winged kite algorithm. Comput. Netw. 2025, 259, 111091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Song, Z.; Meng, J.; Wu, C. Prediction of Lithium-Ion Battery State of Health Using a Deep Hybrid Kernel Extreme Learning Machine Optimized by the Improved Black-Winged Kite Algorithm. Batteries 2024, 10, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xu, B.; Zheng, Y.; Yue, Y.; Xiong, M. Path Optimization Strategy for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Based on Improved Black Winged Kite Optimization Algorithm. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wang, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, L. A Multi-Objective Black-Winged Kite Algorithm for Multi-UAV Cooperative Path Planning. Drones 2025, 9, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, S.; Kaliyaperumal, D.; Porselvi, T.; Sangeetha, S.V.T.; Alroobaea, R.; Emara, A. Optimal sizing of hybrid renewable energy systems relying on the black winged kite algorithm for performance evaluation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 20568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, K.; Zhang, C.; Shao, X.; Shen, H.; Heidari, A.A.; Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Gao, Z. An enhanced black-winged kite algorithm boosted machine learning prediction model for patients’ waiting time. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2025, 105, 107425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Shi, C.; Hu, F.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, K.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y. RC parameter identification and load aggregation analysis of air-conditioning systems: A multi-strategy improved black-winged kite algorithm. Energy Build. 2025, 337, 115641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, H.; Elkhanchouli, K.; Elghouate, N.; Bencherqui, A.; Tahiri, M.A.; Karmouni, H.; Sayyouri, M.; Moustabchir, H.; Askar, S.S.; Abouhawwash, M. A modified black-winged kite optimizer based on chaotic maps for global optimization of real-world applications. Knowl. Based Syst. 2025, 318, 113558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Yue, Y. Heuristic Optimization Algorithm of Black-Winged Kite Fused with Osprey and Its Engineering Application. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, V.J.; Salam, Z.; Ishaque, K. Cell modelling and model parameters estimation techniques for photovoltaic simulator application: A review. Appl. Energy 2015, 154, 500–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, V.J.; Salam, Z. Coyote optimization algorithm for the parameter extraction of photovoltaic cells. Solar Energy 2019, 194, 656–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, S.; Zhao, X.; Zu, G.; Lu, L.; Cheng, C. An algorithm for lane detection based on RIME optimization and optimal threshold. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gafar, M.; Sarhan, S.; Shaheen, A.M.; Ginidi, A.R. Simultaneous Allocation of PV Systems and Shunt Capacitors in Medium Voltage Feeders Using Quadratic Interpolation Optimization-Based Gaussian Mutation Operator. Int. J. Energy Res. 2025, 8881949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, S.A.; Shaheen, A.M.; Alqahtani, M.H.; Al Faiya, B.M. Enhancement of rime algorithm using quadratic interpolation learning for parameters identification of photovoltaic models. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwakeel, A.S.; Shaheen, A.M.; Moustafa, G.; Al Faiya, B.; Smaili, I.H. Integrated fluid antenna systems with reconfigurable intelligent surfaces via quadratic interpolation optimization. Cluster Comput. 2025, 28, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, N.T.; Pora, W. A parameter extraction technique exploiting intrinsic properties of solar cells. Appl. Energy 2016, 176, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şenel, F.A.; Gökçe, F.; Yüksel, A.S.; Yiğit, T. A novel hybrid PSO–GWO algorithm for optimization problems. Eng. Comput. 2019, 35, 1359–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, E.E.; El-Hameed, M.A.; El-Fergany, A.A.; El-Arini, M.M. Parameter extraction of photovoltaic generating units using multi-verse optimizer. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2016, 17, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beigi, A.M.; Maroosi, A. Parameter identification for solar cells and module using a Hybrid Firefly and Pattern Search Algorithms. Solar Energy 2018, 171, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakmi, S.H.; Alnami, H.; Moustafa, G.; Ginidi, A.R.; Shaheen, A.M. Modified Rime-Ice Growth Optimizer with Polynomial Differential Learning Operator for Single- and Double-Diode PV Parameter Estimation Problem. Electronics 2024, 13, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, S.M.; Salahshour, E.; Malekzadeh, M.; Gordillo, F. Parameters identification of PV solar cells and modules using flexible particle swarm optimization algorithm. Energy 2019, 179, 358–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Ge, S.; Qu, B.; Yu, K.; Liu, F.; Yang, H.; Wei, P.; Li, Z. Classified perturbation mutation based particle swarm optimization algorithm for parameters extraction of photovoltaic models. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 203, 112138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizk-Allah, R.M.; El-Fergany, A.A. Conscious neighborhood scheme-based Laplacian barnacles mating algorithm for parameters optimization of photovoltaic single- and double-diode models. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 226, 113522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, M.H.; Mustaffa, Z.; Saari, M.M.; Daniyal, H. Barnacles Mating Optimizer: A new bio-inspired algorithm for solving engineering optimization problems. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2020, 87, 103330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Jiao, S.; Wang, M.; Heidari, A.A.; Zhao, X. Parameters identification of photovoltaic cells and modules using diversification-enriched Harris hawks optimization with chaotic drifts. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 118778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devarajah, L.A.; Ahmad, M.A.; Jui, J.J. Identifying and estimating solar cell parameters using an enhanced slime mould algorithm. Optik 2024, 311, 171890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravichandran, S.; Manoharan, P.; Jangir, P.; Selvarajan, S. Resistance–capacitance optimizer: A physics-inspired population-based algorithm for numerical and industrial engineering computation problems. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaire, U.M.; Hiremath, S.R.; Londhe, K.; Manjusha, C.B.; Mahapatra, A.S. Hybrid butter-flower algorithm: Novel metaheuristic optimization algorithm. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2026, 477, 117148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Gu, S.; Liang, Y.; Ouyang, K.; Li, Y.; Wang, K.; Wu, G.; Fan, C. Wave Optics Optimizer: A novel meta-heuristic algorithm for engineering optimization. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2026, 152, 109337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljumah, A.S.; Alqahtani, M.H.; Ginidi, A.R.; Shaheen, A.M. A novel Kangaroo Escape Algorithm for efficient combined heat and power economic dispatch: Feasibility analysis and validations. Energy Rep. 2025, 14, 2535–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Chen, T.; Wang, H. Centered Collision Optimizer: A novel and efficient physics-based metaheuristic optimization algorithm for solving complex real-world engineering optimization problems. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2026, 448, 118491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shang, Z. Traffic jam optimizer: A novel swarm-based metaheuristic algorithm for solving global optimization problems. Appl. Math. Model. 2026, 150, 116410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.