Abstract

Food waste undermines the four dimensions of food security, availability, accessibility, utilization, and stability, while imposing adverse economic, social, and environmental impacts on sustainable food systems. Understanding the behavioral determinants of food consumption rationalization is essential for addressing this challenge in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. This study examines household food waste behaviors within a knowledge-based framework that integrates three interconnected constructs: awareness of food waste consequences, behavioral knowledge of waste-reduction practices, and actual engagement in conservation strategies. Data were collected from 255 households (response rate: 66%) in Buraydah City through an electronic questionnaire administered in shopping malls. Using Baron and Kenny mediation analysis and multiple linear regression, awareness of waste consequences influences conservation practices both directly (β = 0.132, p < 0.001) and indirectly through behavioral knowledge (accounting for 68.6% of the total effect), explaining 74.9% of the variance in household conservation behaviors (R2 = 0.749). The analysis reveals that awareness of waste consequences influences conservation practices both directly and indirectly through behavioral knowledge, establishing a mediation pathway. Together, these knowledge dimensions significantly explain variations in household conservation behaviors. The findings highlight the critical interplay between awareness and practical behavioral knowledge in driving sustainable food consumption practices. These insights provide empirical guidance for policymakers and agencies seeking to develop targeted interventions that integrate consequence messaging with practical behavioral training to effectively reduce household food waste and promote food security in Saudi Arabia.

1. Introduction

Minimizing food waste is a critical strategy for addressing global challenges, including climate instability, food insecurity, and resource scarcity. This multifaceted problem not only degrades the natural environment but also poses significant risks to public health [1]. Research shows that reducing food waste improves food quality and sustainability [2]. Food waste has serious consequences for food security, the environment, and the economy, as discussed globally, with 79 kg of food waste per capita and 1 billion meals lost daily [1,3]. Economic losses from global food waste total USD 2.6 trillion. This includes USD 700 billion in environmental effects, USD 1 trillion in production and waste losses, and USD 900 billion in quality-of-life losses [4]. Food waste accounts for approximately 28% of the world’s agricultural land, resulting in 1.03 billion tons of waste annually. Currently, 29.6% of the world’s population is moderately to severely food insecure, yet consumer behavior results in the wastage of 60% of food [1]. These facts show that achieving Sustainable Development Goal targets, particularly reducing food waste by 50% by 2030, is difficult [5].

Food waste has far-reaching consequences beyond food security. They deplete resources and reduce future productivity in the food system. Water, land, energy, labor, and capital are needed to produce and distribute food waste. Long-term agricultural sustainability is compromised [6]. Air, water, and soil pollution degrade the ecosystem while depleting resources [7]. Over time, agricultural systems become increasingly responsive to production. In vulnerable agrarian systems, water shortages and nitrogen loss-induced soil erosion increase the costs of resources [8]. Food waste accounts for 8% of global greenhouse gas emissions, third after the US and China [1]. Climate change-causing emissions make climate stabilization and environmental protection harder [9]. Food waste emits greenhouse gases, which can contribute to changes in weather patterns, including increased precipitation, droughts, and poorer agricultural production due to fluctuations in temperature and water availability. Environmental impacts on complex food systems create interconnected vulnerabilities [10]. Many processes affect food security and nutritional adequacy for current and future populations. Food waste reduces US and global food availability. Commodity pricing raises food prices, making it harder for people to obtain. Physical waste depletes nutrition. Unsustainable resource use harms food and nutritional security. Food waste affects all sectors of the global food system; therefore, we must address production, distribution, consumption, and waste management [11].

Food waste represents a critical sustainability issue that directly undermines the dimensions of food security, including availability, access, utilization, and stability [12]. Reducing food waste is a crucial priority for sustainable development, as it provides cost-effective alternatives to increased production and improves food availability [13]. Achieving the 2050 population projections requires a 60% increase in food production, provided that food waste reduction is also implemented simultaneously [1,14].

In Saudi Arabia, food waste represents a critical sustainability challenge. Current estimates indicate an annual waste generation of approximately 2330 million tons (105 kg per capita), accounting for 18.9% of the national waste index and valued at USD 40.48 billion annually. These losses generate annual economic impacts equivalent to 1.9% of gross domestic product [15,16]. Given that Saudi Arabia imports 80% of its food commodities at a yearly cost exceeding USD 12 billion, reducing food waste has a direct impact on national economic sustainability and import dependency. The significance of this challenge is evident in the Kingdom’s strategic prioritization, with food waste identified as a critical risk to food security in national food security strategy documentation [17,18]. Research indicates that food waste behavior functions as a conscious phenomenon, primarily linked to cognitive factors rather than habitual patterns, suggesting substantial potential for intervention through enhanced awareness initiatives [19,20,21]. Consumer-level interventions are crucial, as production-focused solutions are limited without simultaneous changes in consumer behavior [22,23]. Addressing food waste requires comprehensive, consumer-focused measures, particularly as 8.1% of the Saudi population faces severe food insecurity [24].

Consumer engagement occurs when people acknowledge the consequences of food waste and are willing to change their behavior [25]. Awareness campaigns about the environmental, economic, and moral impacts of certain actions can affect behavior, such as shopping with a purpose and reusing leftovers. However, a lack of knowledge and practical assistance makes waste-reduction strategies difficult to implement [26]. Changing habits requires adopting ethical attitudes and acquiring knowledge about food storage and purchasing [27]. Knowledge of environmental challenges, notably landfills and water scarcity, increases responsible consumerism and sustainability [28]. Focusing on food storage and shopping habits reduces waste by 10% in households that shop once a week [29]. This indicates that practical planning abilities significantly reduce waste [30,31]. Cognitive variables, such as food management knowledge and awareness, have the most significant impact on food waste. Some cultural factors, including religion, can prevent food waste [31]. Since it changes many people’s behavior, consumer-level prevention is the most effective intervention. Educational initiatives for young adults, combined with digital communication tools and social media platforms, may be beneficial [23]. Understanding how food waste affects knowledge, behavioral knowledge, and conservation practices is crucial to reducing food waste at all stages of consumption and encouraging sustainable food consumption [24,32,33]. Finding the best means to distribute knowledge ensures that everyone can access it, thereby bridging the gap between knowledge and practice. This supports Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 initiatives, which aim to reduce food waste [10,27]. This study proposes a paradigm that examines the interaction between knowledge of food waste, knowledge of food conservation, and food conservation practices. This study extends traditional KAP by: (1) distinguishing consequences knowledge (theoretical knowledge of impacts) from behavioral knowledge (practical knowledge of implementation), and (2) testing whether behavioral knowledge mediates the relationship between consequence-awareness and practice, thereby identifying distinct motivational and capability mechanisms. The framework integrates the Knowledge-Attitude-Practice (KAP) model’s sequential progression with NAT’s mechanism and SCT’s emphasis on capability development. Behavioral knowledge serves as a mediator through which consequence-awareness translates into practice, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Knowledge-practice integration in household food waste reduction: a mediation framework indicating the behavioral knowledge mediates food waste awareness and conservation practice.

Understanding household food waste requires theoretical frameworks integrating knowledge, attitudes, and practices. While Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) emphasizes intention, Social Practice Theory (SPT) reframes consumption as socially situated, and Value-Belief-Norm (VBN) Theory establishes pathways from values through awareness to personal norms, this study employs a KAP framework distinguishing between consequence knowledge (understanding why waste reduction matters) and behavioral knowledge (understanding how to implement practices), operating as motivational drivers and capability enablers, respectively. This dual-knowledge model clarifies why awareness campaigns alone fail to produce sustained behavior change, provides cultural resonance within the Saudi Arabian context where food waste is psychologically driven, and enables precision in intervention design. The mediation model quantifies direct versus indirect effects, enabling evidence-based resource allocation, with approximately 40% of intervention resources allocated to consequence messaging and 60% to practical training. Food waste in Saudi Arabia amounts to 2330 million tons annually, valued at USD 40.48 billion, equivalent to 18.9% of the country’s total waste. This figure is particularly urgent, given the 80% dependency on food imports, which incurs yearly costs exceeding USD 12 billion. Consumer-level interventions that integrate consequence messaging with practical behavioral training demonstrate significantly greater effectiveness than either approach independently, making the dual-knowledge mediation model essential for advancing intervention effectiveness and supporting Saudi Vision 2030′s food security objectives [10,27].

Research Hypotheses and Theoretical Rationale

This study proposes that knowledge of consequences translates into food waste reduction practices through a dual-mechanism mediation framework that integrates Norm Activation Theory (NAT) and Social Cognitive Theory (SCT). H1: posits that consequence knowledge has a statistically significant total effect on conservation practices through both direct motivational pathways (β = 0.132, p < 0.001) and indirect capability pathways. Grounded in NAT, consequence awareness across four domains—religious-ethical (M = 4.73, highest), economic (M = 3.82), food security (M = 3.58), and environmental (M = 3.15, lowest), activates personal moral responsibility. The religious-ethical domain dominates (83.1% report “completely know” Islamic prohibition of wastefulness), reflecting the cultural embeddedness of Islamic stewardship principles. However, the modest direct effect (31.4% of total impact) reveals that motivation alone produces limited behavior change, requiring capability enhancement for sustained practice [22]. H2: specifies that motivated individuals actively seek behavioral knowledge, operating through Social Cognitive Theory’s knowledge-seeking mechanism. Individuals who understand the consequences experience psychological dissonance between their values (reducing waste and honoring Islamic teachings) and their capabilities (a lack of practical knowledge), motivating them to seek information and acquire skills. This is evidenced empirically: 47.8% of respondents engage with food preservation organizations explicitly teaching behavioral knowledge, with 86.9% reporting high satisfaction. Communication preferences reveal that motivated individuals prioritize efficient knowledge-delivery channels (WhatsApp, M = 3.70; Snapchat, M = 3.53; SMS, M = 3.38) over passive formats (Facebook, M = 2.22; Zoom, M = 2.49), demonstrating that motivation drives active knowledge acquisition rather than passive exposure [34]. H3: proposes that behavioral knowledge mediates the consequence-practice relationship through partial mediation, with capability (not motivation) as the dominant mechanism. The bivariate correlations reveal this pattern: behavioral knowledge predicts practice strongly (r = 0.86), while consequence knowledge predicts practice moderately (r = 0.42), indicating that knowing how (capability) substantially outweighs knowing why (motivation). The indirect pathway through behavioral knowledge accounts for 68.6% of the total effect, while direct motivational effects account for 31.4%. This decomposition has critical intervention implications: approximately 68% of resources should target capability development (practical training, skill-building), while 32% should target motivation (awareness messaging). Partial (not complete) mediation persists because activated personal moral norms maintain independent effects: individuals with strong awareness of consequences implement practices even with imperfect knowledge, driven by an intrinsic sense of responsibility. This integrated model explains why awareness campaigns alone achieve modest behavior change (10–20% variance), while dual-component interventions combining consequence messaging with behavioral training achieve substantial change (74.9% variance explanation), a 4-fold improvement, supporting evidence-based intervention design for household food waste reduction in Saudi Arabia [35]. The integrated model predicts that knowledge of consequences is necessary but insufficient for behavior change. Direct effects reflect motivational activation; indirect effects reflect capability enhancement. Mediation analysis enables the decomposition of mechanisms and informs the design of evidence-based interventions, balancing consequence messaging with practical behavioral training.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Study Area

The city of Buraydah is situated in the north-central part of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, spanning an area of approximately 1300 square kilometers. Its population is estimated, according to the 2022 Saudi population census, to be approximately 677,647 people. The city of Buraydah is considered the agricultural hub of the Qassim region and the entire Kingdom. Agriculture represents the foundation of the regional economy, characterized by the availability of groundwater and fertile lands suitable for agriculture, and is rich in the quality of agricultural production of various types of crops, including wheat, vegetables, fruits, and dates [36].

The region features the world’s largest date palm endowment farm. The project features approximately 200,000 diverse palm trees, with a production quantity exceeding 5000 tons, and has obtained multiple international certifications, including recognition from the Guinness Book of World Records and the European Organization for Organic Agriculture (Ecocert) certificate for the production of organic dates. The study area also encompasses the world’s largest date market, which produces 390,000 tons annually and exports to over 20 countries worldwide [37].

2.2. Research Design and Data Collection Method

The survey was conducted using a convenience, non-probability sample of household shoppers at various locations in major grocery store outlets. This method was used because a complete database of the study population, including contact information for the study population units, was not available. Therefore, this method is suitable for ensuring access to respondents in shopping malls, as grocery stores are a key stage in the food consumption process and are relevant to the study’s topic and objectives. It is also effective for practical communication with shoppers who play a direct role in purchasing and managing food within the household. An electronic questionnaire was presented to shoppers via a link containing a QR code (See Supplementary Materials, Annex S1). Data collection began on 1 June 2025, and continued for up to 2 successive months. Respondents were given the freedom to complete the questionnaire at any location, whether in the shopping mall, upon returning home, or through a family member in their home. The total number of families was determined to be 163,904, and the average number of family members in the study area is four individuals, according to the General Authority for Statistics [38]. The sample size was determined to be 383 according to Stephen Thompson’s equation [39]. A total of 255 Participants completed the questionnaire, which represents a response rate of 66%.

where N is the community size, Z, the standard score corresponding to the significance level of 0.95, is equal to 1.96, D, the error rate is equal to 0.05, and P, Property availability and neutrality ratio = 0.50

2.3. Questionnaire as a Survey Tool

A comprehensive, structured questionnaire was developed to systematically evaluate participants’ knowledge, attitudes, and behavioral practices concerning food waste management. The instrument was organized into four distinct sections, each designed to assess specific dimensions of food waste awareness and behavior. The initial section assessed participants’ foundational knowledge of the food waste concept utilizing a three-point ordinal scale, with response categories denoted as follows: 1 (Don’t know), 2 (Somewhat know), and 3 (Know). This measurement approach provided a preliminary evaluation of conceptual understanding across the respondent population. The three-point scales were selected because they are easier for participants to understand and conceptually suitable for measuring binary capability in knowledge or behavioral items. Statistical limitations due to reduced variance were addressed by increasing the sample size (N = 255, exceeding the minimum required N = 217 at α = 0.05, power = 0.80) and employing nonparametric tests (Kruskal–Wallis or Mann–Whitney) for ordinal data analysis. The subsequent section examined participants’ knowledge of the multifaceted consequences of food waste, encompassing ethical and religious dimensions, as well as economic, environmental, and food security implications. Responses to this section were elicited using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not completely known) to 5 (completely known). The operational definitions of food waste and the constituent knowledge components were derived from and aligned with established literature in the field [11,15,16,40]. The third section comprised a dual assessment of food-saving behaviors, distinguishing between knowledge and actual practice. Knowledge of food-saving behaviors was measured on a three-point scale (1 = “Don’t know,” 2 = “Somewhat know,” 3 = “Completely know”).

In contrast, the frequency of behavioral practice was evaluated using a parallel three-point scale (1 = “Don’t practice,” 2 = “Sometimes practice,” 3 = “Always practice”). Item development adhered to guidelines established by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [41], while the design of practice-oriented items was informed by contemporary empirical research on food conservation behaviors [42,43]. Notably, only respondents who demonstrated at least partial knowledge of food-saving practices (response categories 2 or 3) were subsequently queried regarding their behavioral engagement; respondents indicating no knowledge were systematically excluded from this component of the survey. The final section investigated participants’ management strategies for surplus food, presenting four mutually exclusive behavioral responses: 4 (applying appropriate refrigeration or freezing for subsequent consumption), 3 (donating to individuals in need), 2 (providing to animals), and 1 (disposing of via trash). Complementary items assessed respondents’ satisfaction with their experiences utilizing food preservation organizations on a five-point scale (1 = not at all satisfied to 5 = very satisfied). They evaluated their preferences for information dissemination channels regarding food waste using an analogous five-point Likert scale (1 = not strongly preferred to 5 = strongly preferred).

Regarding the rationale for selecting the 5-point Likert scale, it captures the intensity and certainty of understanding regarding food waste impacts, as consequence awareness operates on a continuum from unawareness to absolute certainty. The 3-point scales for behavioral knowledge and practice measure binary capability, whether individuals possess knowledge of or engage in specific conservation behaviors, reflecting the categorical, implementation-oriented nature of these constructs. Our sample size (N = 255) exceeds the minimum required by power analysis (N = 217, α = 0.05, power = 0.80), ensuring adequate statistical power despite the more parsimonious 3-point scales. Pilot testing demonstrated adequate variance in 3-point scales (SD = 0.32–0.43), confirming sufficient discriminative ability. Sensitivity analysis confirmed that regression coefficients remained stable (r > 0.95) across alternative scale treatments, validating the robustness of our findings regardless of scale specification. This differential scaling approach optimizes measurement precision while maintaining statistical validity and practical interpretability.

2.4. Data Analysis

A descriptive analysis, utilizing percentages, frequency distributions, arithmetic means, and standard deviations (SD), was employed to achieve the research objectives. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 30 was used. Inferential statistical analyses, including independent samples t-tests, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and multiple linear regression, were used to interpret the relationships between variables. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to determine the strength and direction of the relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable. The Baron and Kenny methodology was also followed to analyze the mediation between the components of the paper’s conceptual framework [44]. The mediation model was selected to address a critical gap in the food waste literature: understanding not only whether knowledge influences behavior, but also how this influence occurs. By testing behavioral knowledge as a mediator, this study identifies two pathways: a direct impact of consequence-awareness on behavior (through motivation and responsibility), and an indirect influence through practical skill development. This distinction has important implications for intervention design. Bootstrapped confidence intervals were calculated for indirect effects to provide robust estimates of the significance of the mediation pathway. Sobel tests were also conducted to confirm the significance of mediated effects. All statistical analyses employed two-tailed significance tests with an alpha level of 0.05.

2.5. Validity and Reliability

The questionnaire was evaluated to achieve the study’s objectives and then presented to the scientific committees in the Department of Agricultural Extension and the College of Food and Agricultural Sciences at King Saud University. A pilot test of the questionnaire was conducted with 40 participants in the study area prior to data collection, and reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient, as shown in Table 1. However, the full reliability and validity assessment of the measurement model, including consequences, knowledge, behavioral knowledge, and behavioral practice, is provided in Table S1.

Table 1.

Reliability coefficients (Cronbach’s alpha) for the dimensions and axes of the study tool.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Economic Characteristics of the Respondents (Participants)

The demographic profile of the study group exhibited significant characteristics across various dimensions. The gender distribution indicated that females comprised the majority, at 62.7%, in contrast to males, who made up 37.3%. The participants’ ages were widespread, with the biggest group being those between the ages of 35 and 49 (42.7%), followed by those under 34 (32.2%), and those over 50 (25.1%). The participants had high levels of education, with 69.8% having completed university studies and 6.7% having pursued postgraduate studies (Master’s or PhD). Fifteen percent of the sample had completed secondary school, while 5% had completed intermediate school, and 2% had completed elementary school. Analysis of family composition revealed that most participants resided in medium-sized homes. The largest group (45.5%) consisted of families with 5–7 persons. There were 32.5% of the sample families with 2–4 members, and 22.0% of the sample families with 8–10 members. The monthly family income exhibited considerable economic variability within the sample. The distribution was pretty even across income groups: 15.3% earned < 5000 riyals, 25.1% earned between 5000 and 10,000 riyals, 18.8% earned between 10,000 and 15,000 riyals, and 18.8% earned 15,000 riyals or more. A significant 22.0% of participants chose not to reveal their income information, suggesting a possible sensitivity towards financial disclosure (Table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution of study sample members according to their demographic characteristics.

3.2. Knowledge of the Concept of Food Waste

The vast majority of participants demonstrated a deep awareness of food waste, with 86.3% correctly stating that it refers to food that is intended to be eaten but is not. Another 11.4% were somewhat aware of the concept, and only 2.4% stated they knew nothing about food waste. The results show that the people in the research had a clear idea of what food waste is. Most of the people who answered demonstrated responsible ways to dispose of extra food. Most of them (64.7%) used the best storage methods, putting extra food in the fridge or freezer for later use. In total, 20.4% of people gave items to people in need, while 13.3% of people used them as animal feed. A tiny percentage (1.6%) threw away extra food in the trash, which suggests that most people know how to handle food properly and reduce waste. Approximately half of the participants (53.3%) remained in contact with food preservation groups, and 47.8% reported using their services. People who used these groups were generally satisfied with the services they received: 86.9% reported being delighted with the services overall (62.3% stated they were entirely happy, and 24.6% said they were glad to some extent). There was very little dissatisfaction, with only 1.6% of people being unhappy and none reporting depression. On the other hand, 11.5% reported being somewhat satisfied. This indicates that most people had positive experiences with the Food Preservation Society’s services, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Frequency distributions and percentages of knowledge, behavior, and coping with food preservation societies.

3.3. Level of Knowledge of the Effects of Food Waste

In Table 4, participants understood the impact of food waste on various aspects, including religious, economic, environmental, and food security. Table 4 demonstrates knowledge levels by effect, with mean scores from 4.73 to 3.15. The Islamic religious principle against wastefulness received the highest mean score (4.73), indicating it was the most significant influence. The participants’ notion of resource responsibility matches Islamic values. In economics, the awareness that wasted food leads to decreased income rated second (M = 4.29), while the comprehension that wasted food costs manufacturing, transportation, and storage ranked third (M = 4.16). That throwing away food makes things more expensive was fifth (M = 3.87), and that Kingdom people waste a lot of food was sixth (M = 3.77). Food waste was recognized as a significant issue, with a mean of 3.61. Participants knew that food waste reduces food availability (M = 4.13, rank 1) and raises food prices (M = 4.00, rank 2). Throwing away healthy food makes it harder to find it in third place (M = 3.81), and it wastes natural resources in fourth place (M = 3.72). Environmental comprehension was moderate to good. People initially learned that food waste wastes production resources (M = 3.82). Food waste contributes to ecological contamination through excessive resource use, a phenomenon that individuals are aware of (M = 3.64). Third place went to awareness of pesticide and fertilizer loss environmental issues (M = 3.52). Knowledge that the National Program aims to halve food waste by 2030 ranked fourth (M = 3.40). The least known information was that food waste contributes to increased greenhouse gas emissions (M = 3.15), scoring lowest in all categories. The consequences of food waste on all areas were moderately well-known, as the average knowledge score was 3.80.

Table 4.

Knowledge of the Effects of Food Waste across Religious, Economic, Environmental, and Food Security Dimensions. A: I don’t know exactly, B: don’t know, C: I know to some extent, D: I know, F: I know exactly.

3.4. Knowing the Behaviors of Rationalizing Food Consumption

Data in Table 5 illustrated that participants demonstrated significant comprehension of food conservation methods and initiatives aimed at reducing food waste. The average scores for these behaviors, ranging from 2.85 to 2.51, are presented in Table 5. The average score was 2.67. The fundamental aspect of water conservation is the efficient utilization of this resource to reduce waste. The mean score was 2.85, indicating a considerable awareness of this behavior among individuals. The second most critical factor was ensuring that food was devoid of stains, decay, stickiness, and discoloration (M = 2.82). The third most critical aspect was ensuring that canned items were not bulging, rusted, cracked, or leaking (M = 2.79). Consuming items with the shortest shelf life ranked fourth (M = 2.74), while refraining from providing excess food at meals ranked fifth (M = 2.73). Monitoring expiration dates during purchasing ranked sixth (M = 2.69), indicating a moderate level of comprehension. Documenting a list of dietary requirements prior to shopping ranked ninth (M = 2.63). Refraining from allowing prepared food to remain at room temperature for over two hours ranked as the eighth most significant factor (M = 2.62), while avoiding grocery shopping while hungry was the ninth most considerable factor (M = 2.60). Refraining from purchasing unnecessary food items due to sales ranked tenth (M = 2.54), while adhering to the food requirements list during shopping ranked eleventh (M = 2.52). The evaluation of storage instructions on products yielded the lowest mean score (M = 2.51), indicating that respondents deemed this task the least significant in relation to their comprehension of conservation techniques. The mean knowledge score of 2.67 suggests that individuals demonstrated a moderate to high level of awareness regarding the food conservation activities examined.

Table 5.

Knowledge of Food Conservation Behaviors and Preventive Measures. A: I don’t know exactly, B: don’t know, C: I know to some extent.

3.5. Practice and Implementation of Food Conservation Behaviors

Participants conserved food moderately to highly in their daily activities. Table 6 ranks these activities by mean score, which varied from 2.77 to 2.23 with an average of 2.47 (SD = 0.43). The majority of practices were constant. Buying food without stains, rot, stickiness, or discoloration was of high importance. Its mean score of 2.77 indicates quality-consciousness. The second most essential thing was checking canned goods for bulging, rust, damage, or leaking (M = 2.76). Drinking water sensibly to avoid waste was the third most important (M = 2.75). Fourth place (M = 2.71) was achieved by eating the shortest-lasting items first. Shoppers checked expiration dates fifth (M = 2.67). The sixth most important thing was not leaving prepared food at room temperature for more than two hours (M = 2.63). Not overserving meals took seventh place (M = 2.58) with mediocre implementation. Making a food list before shopping was tenth (M = 2.55), and sticking to it while shopping was ninth (M = 2.51). Reading product storage instructions was rated eighth (M = 2.50), with the least utilization. Avoiding sales that led to buying undesirable food was rated tenth (M = 2.31), with 10.4% and 48.5% unsure due to limited practice. Avoiding shopping when hungry yielded the lowest mean score (M = 2.23), indicating the poorest execution, with 13.4% of participants being uninformed and 50.2% being confused. The knowledge score of 2.67 was substantially higher than the practice score of 2.47. Participants were more aware of food conservation practices in theory than in practice, suggesting a gap between knowledge and actual behavior (Table 6).

Table 6.

Practice and Implementation of Food Conservation Behaviors. A: I don’t know exactly, B: don’t know, C: I know to some extent.

3.6. Respondents’ Preference for Means of Knowledge Transfer on the Subject of Food Waste

Respondents had several options for learning about reducing food waste and conserving resources. Table 7 ranks ten communication platforms by mean preference scores from 3.70 to 2.22. All techniques were “Average” preferred. The most popular method to communicate knowledge was WhatsApp, with a mean score of 3.70. A 38.4% considered it highly recommended, and 23.5% agreed. Snapchat ranked second (M = 3.53), with 32.2% highly recommending it and 27.8% favoring it. The X platform placed fourth (M = 3.35), while mobile text messaging placed third (M = 3.38). Lectures ranked sixth (M = 3.32), indicating that traditional teaching methods were still popular. TikTok placed sixth (M = 3.29), suggesting that people are becoming increasingly interested in short-form video, despite 22% not liking it. Instagram was ninth (M = 3.01), and YouTube was seventh (M = 3.26). The Zoom app. ranked tenth (M = 2.49), with 31.8% intensely hating it and 10.2% recommending it remarkably. This indicates that synchronous virtual meetings are less popular. Facebook scored lowest (M = 2.22). Only 10.2% strongly approved it, while 44.3% strongly disliked it. This suggests that people are reluctant to share knowledge on this platform. WhatsApp, Snapchat, and mobile text messages were the most popular platforms for food waste education. Facebook and Zoom were the least popular.

Table 7.

Level of preference for knowledge transfer methods.

3.7. Examining the Correlation Between Awareness of Food Waste Consequences and Rationalization of Food Consumption: A Mediation Analysis

A mediation model was employed to investigate the interrelations among three principal variables: awareness of the consequences of food waste (theoretical knowledge), understanding of food conservation practices (behavioral knowledge), and the implementation of food rationalization activities. This investigation aimed to determine whether behavioral knowledge acts as a mediator in the relationship between theoretical knowledge and actual behavioral practices, using the Baron and Kenny technique. Initial analysis indicated statistically substantial relationships among all three variables. A considerable link existed between knowing how to conserve food and actually doing so (r = 0.86, p < 0.001). This means that being aware of the right actions is closely linked to doing them. Understanding the repercussions of food waste was positively correlated with actual activity (r = 0.42, p < 0.001), indicating a direct link between awareness of the consequences of food waste and subsequent action. Moreover, awareness of the repercussions of food waste showed a strong correlation with awareness of food conservation practices (r = 0.36, p < 0.001), thereby affirming that theoretical comprehension enhances the development of behavioral knowledge (Table 8).

Table 8.

Correlation Coefficients Between Knowledge of Food Waste, Knowledge of Food Conservation Behaviors, and Actual Practice of Food Rationalization Behaviors.

- Step 1: The Immediate Impact of Food Waste Awareness on Behavioral Practice

Regression analysis investigated the direct influence of awareness on the effects of food waste on food rationalization habits (Table 9). Awareness of food waste impacts has shown a favorable and statistically significant impact on behavioral practice (B = 0.221, β = 0.421, p < 0.001), signifying a robust link. This model elucidated 17.7% of the variance in food conservation practices (R2 = 0.177, F(1, 253) = 54.59, p < 0.001), demonstrating that theoretical knowledge alone yields significant predictive value for behavioral results.

Table 9.

Regression results for predicting behavioral practices through knowledge of the effects of food waste.

- Step 2: The effect of knowing about food waste on knowing how to behave

The correlation between awareness of food waste consequences and understanding of food conservation practices was further analyzed (Table 10). Theoretical knowledge was a strong predictor of behavioral knowledge (B = 0.139, β = 0.357, p < 0.001), and knowledge of the impacts of food waste explained 12.7% of the variance in behavioral knowledge (R2 = 0.127). This phase confirmed that moving from knowing what happens to food waste to having practical behavioral information made sense.

Table 10.

Regression results for predicting behavioral knowledge through knowledge of the effects of food waste.

- Step 3: Complete Mediation Model Incorporating Behavioral Knowledge

The full mediation model was evaluated by concurrently inputting both the independent variable (awareness of food waste consequences) and the mediating variable (awareness of food conservation methods) to predict actual behaviors (Table 11). The standardized effect of understanding the impacts of food waste decreased from β = 0.421 to β = 0.132; however, it remained statistically significant (p < 0.001), indicating partial mediation. Behavioral knowledge had a significantly greater impact on practice (B = 1.088, β = 0.809, p < 0.001), substantially exceeding the direct influence of theoretical information. The complete model accounted for 74.9% of the variance in food rationalization behaviors (R2 = 0.749), indicating a markedly enhanced predictive capability relative to the simple model, hence illustrating the approach’s considerable efficacy.

Table 11.

Regression results for predicting the practice of behaviors through knowledge of effects and knowledge of behaviors.

These findings validate partial mediation, indicating that awareness of food waste impacts behavior both directly and indirectly, through shaping behavioral knowledge. The significant drop in the direct effect coefficient, while still statistically substantial, indicates that behavioral knowledge is a crucial link between theoretical understanding and practical behavior. These findings highlight the need for formulating comprehensive awareness campaigns that integrate theoretical insights into the ramifications of food waste with practical behavioral directives, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of translating awareness into sustainable food conservation practices. The direct effect of knowledge on conservation practice (R2 = 0.177) accounts for 17.7% of the variance, which may appear modest. However, this is consistent with social psychological research on behavioral prediction [cite: relevant studies]. When behavioral knowledge is included as a mediator, the model explains 74.9% of the variance in conservation practice (combined R2), demonstrating substantial improvement. This suggests that the indirect pathway through behavioral knowledge accounts for a considerable amount of behavioral variance. Additionally, conservation behavior in real-world household contexts is influenced by numerous factors beyond knowledge (financial constraints, household structure, storage availability, time availability, habit persistence), indicating that explaining 74.9% of variance through knowledge-based mechanisms is substantial. The direct pathway captures intrinsic motivation effects (understanding consequences directly activates norms), while the indirect pathway captures capability effects (motivation drives knowledge-seeking, enabling behavior). Both mechanisms make a meaningful contribution to understanding behavior.

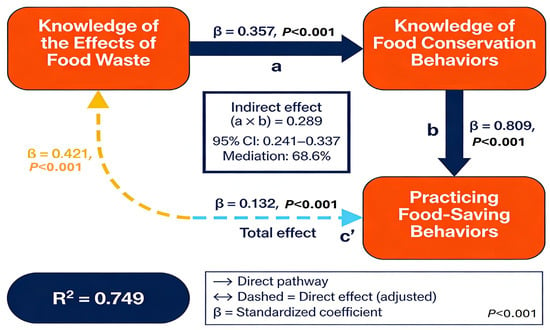

Knowledge of food conservation behaviors served as a critical mechanism for translating consequence awareness into food-saving practices, with the model explaining 74.9% of the variance in behavioral outcomes (R2 = 0.749), as shown in Figure 2. Knowledge of the effects of food waste demonstrated a substantial total effect on practice (β = 0.421, p < 0.001), decomposing into direct (β = 0.132, p < 0.001) and indirect pathways through conservation knowledge (β = 0.357, p < 0.001). The strongest relationship was between conservation knowledge and the implementation of practice (β = 0.809, p < 0.001), with the indirect effect accounting for 68.6% of the total influence. These results support partial mediation, wherein behavioral knowledge, understanding concrete, actionable strategies for food waste reduction, represents the proximal determinant of food-saving practice. The findings align with Social Cognitive Theory’s emphasis on behavioral capability as an essential mediator that translates motivational awareness into action, while supporting Norm Activation Theory by demonstrating that consequence awareness activates motivation for behavioral knowledge acquisition. Intervention implications are significant: awareness campaigns establishing the consequences of food waste are necessary but insufficient; sustained behavior change requires complementary investment in behavioral knowledge development through practical instruction in meal planning, food storage, and waste reduction. The high explanatory power of the knowledge-based model positions behavioral knowledge acquisition as a high-leverage intervention target for promoting household food waste reduction aligned with Saudi Vision 2030 objectives.

Figure 2.

Knowledge of food conservation behaviors mediates the relationship between awareness of the consequences of food waste and food-saving practices. Path a represents the effect of consequence awareness on conservation knowledge (β = 0.357, p < 0.001); path b represents the effect of conservation knowledge on food-saving behavior (β = 0.809, p < 0.001); path c’ represents the direct effect adjusted for mediation (β = 0.132, p < 0.001). The indirect effect (a × b = 0.289, 95% CI: 0.241–0.337) represents 68.6% of the total effect (0.421), indicating strong mediation. The model explains 74.9% of the variance in practicing food-saving behaviors (R2 = 0.749). All pathways are statistically significant at p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

4.1. General Discussion

This study shows that household food waste reduction is driven by a tripartite knowledge pathway linking awareness of consequences, behavioral knowledge of conservation practices, and their enactment in daily life. A dual-component intervention that combines consequence awareness (moral motivation) with behavioral knowledge (practical capability) explains 74.9% of practice variance, versus 17.7% for consequence awareness alone, confirming the central mediating role of behavioral knowledge. Effective programs must integrate “why” and “how” elements by clarifying environmental (e.g., climate change), economic, and food security impacts, while strengthening key behaviors such as reading storage instructions, sticking to shopping lists, avoiding shopping when hungry, and resisting unnecessary promotions. Allocating approximately 40% of communication resources to consequence-focused messaging and 60% to practical training provides concrete guidance for actors working toward Saudi Vision 2030′s goal of halving food waste, especially when framed through Islamic stewardship and economic responsibility, and targeted at behaviors such as impulse buying and poor label use. Preferences for WhatsApp, Snapchat, and SMS among female household decision-makers highlight promising channels for integrated outreach that blends consequence messaging with structured skills training, supported by partnerships with food preservation and food security associations. At the same time, future work should test optimal message ratios and identify barriers that hinder the translation of knowledge into sustained conservation behavior.

4.2. Theoretical Contributions and Framework Alignment

This study advances the KAP model through methodological innovation, distinguishing between consequence knowledge (theoretical understanding of impacts) and behavioral knowledge (practical understanding of implementation), with behavioral knowledge functioning as a mediator [32]. This refinement addresses a critical gap in the environmental behavior literature, where traditional KAP models assume a linear progression [25,26,27]. Our findings demonstrate that knowledge operates through dual pathways, aligning with both Norm Activation Theory (NAT) and Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) [35,45,46].

The mediation model’s empirical findings offer theoretical clarity lacking in prior KAP research. The direct pathway (β = 0.132, p < 0.001) reflects NAT’s mechanism whereby consequence awareness activates personal moral responsibility, maintaining independent effects on behavior [47]. The indirect pathway (accounting for 68.6% of total influence) reflects SCT’s emphasis on behavioral capability as a prerequisite for translating motivation into action [48,49]. This dual-mechanism model explains why awareness campaigns alone produce modest behavior change (17.7% variance explained) while integrated consequence-plus-capability interventions achieve substantial improvement (74.9% variance explained), resulting in a 4.2-fold effectiveness gain [22,35]. The partial mediation pattern (not complete mediation) confirms that consequence knowledge maintains direct effects while facilitating knowledge-seeking, demonstrating theoretically distinct motivational and capability pathways [44,50].

4.3. Contextualized Findings: Cultural and Regional Significance

The finding that religious-ethical consequence awareness dominates (M = 4.73, with 83.1% reporting “completely know” Islamic prohibitions) compared to environmental awareness (M = 3.15, in the lowest category) reflects Saudi Arabia’s unique cultural context, where Islamic stewardship principles provide powerful motivational frames [51,52]. This pattern contradicts Western literature, which emphasizes environmental appeals, and validates the theoretical argument that knowledge effectiveness is culturally contingent [23,53]. Environmental knowledge deficiency (greenhouse gas emissions M = 3.15) identifies a specific intervention target: connecting abstract climate impacts to concrete regional concerns (water scarcity, Islamic stewardship principles) rather than relying on global climate messaging [9,54].

The 98.4% surplus food conservation rate (storage, donation, or animal feed) versus 1.6% disposal reflects conscious, deliberate food management behavior driven by cognitive factors rather than habitual patterns [19,20]. This finding empirically supports the behavioral nature hypothesis that food waste in Saudi Arabia is amenable to behavioral intervention through knowledge enhancement [24,32].

The knowledge-practice gap (knowledge M = 2.67 vs. practice M = 2.47; a 7.5-percentage-point difference) reveals implementation barriers that operate independently of awareness [26,31]. Low scores for impulse-control behaviors (avoiding hungry shopping, M = 2.23, and avoiding sales-driven purchases, M = 2.31) and list adherence (M = 2.52) suggest that competing immediate priorities and habit persistence override awareness [27,55]. This pattern suggests that interventions must address implementation barriers through environmental design, habit formation support, and concrete feedback mechanisms, rather than merely transferring knowledge [56,57].

4.4. Mediation Model: Mechanism and Intervention Implications

The mediation analysis reveals that behavioral knowledge serves as the proximal determinant of food-saving practice, with substantially greater effect (β = 0.809) than theoretical knowledge alone [48]. This finding operationalizes SCT’s argument that knowing “how to reduce waste” (behavioral knowledge) is more influential than knowing “why to reduce waste” (consequence knowledge) [35,49]. However, the presence of direct effects (β = 0.132) indicates that motivated individuals implement practices even with imperfect practical knowledge, driven by intrinsic moral responsibility [25,47].

The empirical pathway decomposition provides actionable resource allocation: consequence messaging should represent approximately 40% of intervention resources (direct effect pathway with 31.4% of total influence). In comparison, behavioral training should account for 60% (an indirect effect pathway with a 68.6% total influence). This evidence-based allocation differs substantially from typical awareness-focused campaigns that emphasize consequences without equivalent investment in practical skill-building [22,58].

4.5. Implications for Intervention Design and Policy

Integration of Dual-Component Messaging: Effective interventions require simultaneous emphasis on consequence awareness (“Why: Food waste depletes resources, violates Islamic principles, threatens food security”) and behavioral capability (“How: List-making before shopping, checking expiration dates, proper storage methods”) [26,28,31]. Current separation of these components in awareness campaigns explains their limited effectiveness [23]. Integrated messaging campaigns should present consequences and practical solutions as complementary elements within single communications [59,60].

Channel Selection and Digital Strategy: WhatsApp (M = 3.70) and Snapchat (M = 3.53) emerge as high-efficacy channels, reflecting Saudi demographic preferences for direct, rapid messaging over passive platforms [61,62]. Facebook (M = 2.22) and Zoom (M = 2.49) demonstrate limited utility, suggesting that synchronous/passive platforms conflict with knowledge-acquisition preferences [63]. Given that 62.7% of household food managers are female, WhatsApp-based interventions targeting female household decision-makers represent an optimal allocation of resources [64,65].

Food Preservation Association Expansion: Current usage (47.8%) coupled with exceptionally high satisfaction (86.9% completely satisfied) indicates proven institutional effectiveness with substantial expansion potential [30,32]. Organizations should: (1) shift from in-person services to WhatsApp-based behavioral training modules, increasing accessibility and reach [61,66]; (2) develop modular training addressing low-performance domains (list-making, label-reading, impulse shopping avoidance) [29,67]; (3) establish retail partnerships positioning behavioral support at critical decision points (grocery store information kiosks) [68]; and (4) target female household managers through gender-sensitive program design acknowledging competing time demands [64].

Environmental Knowledge Enhancement: The systematic deficiency in environmental awareness, particularly regarding greenhouse gas emissions (M = 3.15), represents both a limitation and an opportunity for intervention [9,28]. Rather than relying on abstract global climate messaging, effective campaigns should localize environmental impacts through water scarcity frames that align with Saudi regional concerns and Islamic stewardship principles, connecting food waste to resource depletion that contradicts Islamic teachings on stewardship [52,54,69]. Targeted Behavior Modification: Specific behaviors demonstrate intervention resistance: avoiding hungry shopping (M = 2.23 practice score, 13.4% uninformed) and avoiding impulse purchases (M = 2.31). These low scores suggest that point-of-purchase psychological interventions (e.g., smartphone shopping list notifications, contactless payment reminders) may prove more effective than knowledge transfer alone [55,67,68].

Future research priorities include: (1) longitudinal studies tracking behavior change persistence following dual-component interventions using objective waste audits rather than self-report; (2) randomized controlled trials manipulating consequence-versus-behavioral messaging ratios to establish optimal allocation; (3) qualitative research exploring knowledge-practice gap barriers (time constraints vs. competing priorities vs. active non-compliance); (4) systematic moderation analysis across demographic strata; (5) comparative regional research testing generalizability; and (6) mechanistic research explicitly testing Norm Activation versus Self-Efficacy pathways through moderated mediation analyses.

5. Study Limits

Convenience sampling at shopping mall locations introduces selection bias; however, the findings remain descriptive of urban, regularly shopping households in Buraydah, and shopping malls provide strategic access to primary food managers. Resource constraints precluded the use of stratified random sampling, and geographic confinement limits the generalizability to other Saudi regions. Self-reported behavioral data is prone to social desirability bias, female overrepresentation (62.7%), and university education overrepresentation (76.5%), which may inflate knowledge levels. Income non-disclosure (22%) can mask economic barriers, and a lack of seasonal assessment provides only a temporal snapshot. The cross-sectional design precludes causal inference; however, mediation analysis suggests the theorized mechanisms. Future research employing longitudinal designs with stratified sampling by region, income, and education level, as well as objective behavioral measures and complete demographic representation, would strengthen the evidence. Despite these limitations, the findings provide robust mechanistic evidence for knowledge-practice mediation and establish guidance on resource allocation for dual-component interventions that support Saudi Vision 2030′s food security objectives.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su18020686/s1, the questionnaire is attached as Annex S1 and Table S1 for the reliability and validity assessment of the measurement model, including consequences, knowledge, behavioral knowledge, and behavioral practice.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Preparation, and Formal analysis, O.M.A.-T.; Data collection and organization, O.M.A.-T., M.A.A. and F.O.A.; Review and editing, Preparation of original draft, O.M.A.-T., F.O.A. and H.B. Conceptualization and methodology, O.M.A.-T. and F.O.A.; Formal analysis, M.I.M.; Writing—original draft preparation, H.M.M. and H.B.; Writing—review and editing, H.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Researchers would like to thank the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Qassim University for financial support (QU-APC-2026).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Deanship of Graduate Studies, King Saud University, REF NO. KSU–HE-25 (protocol code 693 and date of approval 19 May 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations Environment Programme. Food Waste Index Report 2024; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2024; Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/publication/food-waste-index-report-2024 (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Brennan, A.; Browne, S. Food waste and nutrition quality in the context of public health: A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiad, M.G.; Meho, L.I. Food loss and food waste research in the Arab world: A systematic review. Food Secur. 2018, 10, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Food Wastage Footprint: Full Cost Accounting; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). The State of Food and Agriculture 2019. In Moving Forward on Food Loss and Waste Reduction; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019; Available online: https://www.fao.org/interactive/state-of-food-agriculture/2019/en/ (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Bisangwa, E. The Effects of Halving Lost and Wasted Food on Food Security, Water, Land and Fertilizer Resources—A Quantitative Comparison Between Developed and Less Developed Regions. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, USA, 2019. Available online: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Baig, M.B.; Gorski, I.; Neff, R.A. Understanding and addressing waste of food in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 26, 1633–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummu, M.; De Moel, H.; Porkka, M.; Siebert, S.; Varis, O.; Ward, P.J. Lost food wasted resources: Global food supply chain losses and their impacts on freshwater, cropland, and fertiliser use. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 438, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdock, A. What You Need to Know About Food Waste and Climate Change; University of California News: Oakland, CA, USA, 2017; Available online: https://www.universityofcalifornia.edu/news/what-you-need-know-about-food-waste-and-climate-change (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Baig, M.B.; Al-Zahrani, K.H.; Schneider, F.; Straquadine, G.S.; Mourad, M. Food waste posing a serious threat to sustainability in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia–A systematic review. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 26, 1743–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE). Food Losses and Waste in the Context of Sustainable Food Systems. In A Report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014; Available online: www.fao.org/cfs/cfs-hlpe (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Ishangulyyev, R.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.H. Understanding food loss and waste—Why are we losing and wasting food? Foods 2019, 8, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KC, K.B.; Haque, I.; Legwegoh, A.F.; Fraser, E.D.G. Strategies to Reduce Food Loss in the Global South. Sustainability 2016, 8, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Environment, Water and Agriculture. Food Security Strategy and Implementation Plan: Executive Summary; Ministry of Environment, Water and Agriculture: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2018. Available online: https://www.mewa.gov.sa/en/Ministry/initiatives/SectorStratigy/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Saudi Grains Organization (SAGO). Baseline: Food Loss and Waste Index in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia; King Fahd National Library: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2021; Available online: https://www.academia.edu/51050246/Quantifying_Food_Loss_and_Waste_in_Saudi_Arabia (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Baig, M.B.; Alotaibi, B.A.; Alshammari, G.M.; Shah, A.A. Food waste in Saudi Arabia: Causes, consequences, and combating measures. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, M.A.; Chang, S.K.; Hefni, D. A comprehensive review on challenges and choices of food waste in Saudi Arabia: Exploring environmental and economic impacts. Environ. Syst. Res. 2024, 13, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu’azu, N.D.; Blaisi, N.I.; Naji, A.A.; Abdel-Magid, I.M.; AlQahtany, A. Food waste management current practices and sustainable future approaches: A Saudi Arabian perspective. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2019, 21, 678–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Rural Transformation—Key for Sustainable Development in the Near East and North Africa. In Overview of Food Security and Nutrition 2018; FAO: Cairo, Egypt, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Althumiri, N.A.; Basyouni, M.H.; Duhaim, A.F.; AlMousa, N.; AlJuwaysim, M.F.; BinDhim, N.F. Understanding food waste, food insecurity, and the gap between the two: A nationwide cross-sectional study in Saudi Arabia. Foods 2021, 10, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The General Grain Organization (SAGO). Results and Initiatives of the Food Loss and Waste Study in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia; King Fahd National Library: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2019; Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/545730749/Baseline-230719 (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Stancu, V.; Haugaard, P.; Lähteenmäki, L. Determinants of consumer food waste behaviour: Two routes to food waste. Appetite 2016, 96, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Global Food Losses and Food Waste—Extent, Causes and Prevention; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2011; ISBN 978-92-5-107205-9. [Google Scholar]

- Jagau, H.L.; Vyrastekova, J. Behavioral approach to food waste: An experiment. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 882–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, V.; Gombos, S. Household food waste reduction determinants in Hungary: Towards understanding responsibility, awareness, norms, and barriers. Foods 2025, 14, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, A.E.; Yildirim, P. Understanding food waste behavior: The role of morals, habits, and knowledge. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, S.; Cerchione, R.; Salo, J.; Ferraris, A.; Abbate, S. Measurement of consumer awareness of food waste: Construct development with a confirmatory factor analysis. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 337–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananda, J.; Karunasena, G.G.; Mitsis, A.; Kansal, M.; Pearson, D. Analysing behavioural and socio-demographic factors and practices influencing Australian household food waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 306, 127280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, I.; Kamal, K.T.; Bhattacharjee, P.; Taqi, H.M.M.; Ali, S.M. Improving consumer awareness for reducing food waste using partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) approach. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2025, 100, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Li, F.; Zhao, X.; Liu, H.; Liu, X. The association between religious beliefs and food waste: Evidence from Chinese rural households. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.C.; Chen, X.; Yang, C. Consumer food waste behavior among emerging adults: Evidence from China. Foods 2020, 9, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szakos, D.; Szabó-Bódi, B.; Kasza, G. Consumer awareness campaign to reduce household food waste based on structural equation behavior modeling in Hungary. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 24580–24589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, F.; Dehghani, A.; Ratansiri, A.; Ghaffari, M.; Raina, S.K.; Halimi, A.; Rakhshanderou, S.; Isamel, S.A.; Amiri, P.; Aminafshar, A.; et al. ChecKAP: A Checklist for Reporting a Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice (KAP) Study. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2024, 25, 2573–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alzghoul, B.I.; Seedahmed, H.M.; Ibraheem, K.M. Developing and Validating a Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice (KAP) Questionnaire for Pain Management. Open Public Health J. 2025, 18, e18749445181057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs. Comprehensive Urban Vision Report for the City of Buraydah (Future Saudi Cities Programme); Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2019. Available online: https://www.momra.gov.sa (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Ministry of Media, Buraydah. Saudi Digital Encyclopedia (Saudipedia). 2025. Available online: https://saudipedia.com/en/article/271/government-and-politics/ministries/ministry-of-media (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- General Authority for Statistics. Saudi Census 2022 Statistics: Household Statistics (Buraydah Region); General Authority for Statistics: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2022. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.sa/en/ (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Thompson, S.K. Sampling; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Volume 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiteau, J.M. Food Loss and Waste in the United States and Worldwide. World Hunger News. Available online: https://www.worldhunger.org/food-loss-and-waste-in-the-united-states-and-worldwide/ (accessed on 13 June 2018).

- General Food and Drug Authority. Reducing Food Waste. Awareness Campaigns. Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. 2018. Available online: https://www.sfda.gov.sa/ar/awarenesscampaign/74336 (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Ali, I.A.S. Rural women’s behavior related to reducing household food waste in some sugar beet villages in Alexandria Governorate. J. Adv. Agric. Res. 2020, 25, 140–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nasser, M.K.; Al-Tarawneh, M.S. Analyzing the Behavior of Jordanian Families Towards Reducing Household Food Waste: A Case Study of Families in Amman. Master’s Thesis, Jerash University, Jerash, Jordan, 2022. Available online: https://search.emarefa.net/detail/BIM-1454006 (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neff, R.A.; Spiker, M.L.; Truant, P.L. Wasted food: US consumers’ reported awareness, attitudes, and behavior. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attiq, S.; Habib, M.D.; Kaur, P.; Hasni, M.J.S.; Dhir, A. Drivers of food waste reduction behaviour in the household context. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 94, 104300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robelia, B.; Murphy, T. What do people know about key environmental issues? A review of environmental knowledge surveys. Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 18, 299–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanes, K.; Dobernig, K.; Gözet, B. Food waste matters—A systematic review of household food waste practices and their policy implications. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 978–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, Z.M.; Ismail, A.; Rahim, N.; Apandi, S.R.M.; Farook, F. The Impact of Environmental Knowledge on Food Waste Reduction and Sustainability Practices among Hospitality Students in Malaysia. Inf. Manag. Bus. Rev. 2024, 16, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Werf, P.; Seabrook, J.A.; Gilliland, J.A. The quantity of food waste in the garbage stream of southern Ontario, Canada, in households. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Commerce and Industry. Initiative for Rationalizing Food Consumption and Preserving It from Waste; The National Committee for the Campaign on Rationalizing Food Consumption, Ministry of Commerce and Industry: Kuwait City, Kuwait, 2023. Available online: https://pafn.gov.kw/assets/images/Uploads/18022024.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Etim, E.; Choedron, K.T.; Ajai, O.; Duke, O.; Jijingi, H.E. Systematic review of factors influencing household food waste behaviour: Applying the theory of planned behaviour. Waste Manag. Res. 2024, 43, 803–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanes, K.; Stagl, S. Food waste fighters: What motivates people to engage in food sharing? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 211, 1491–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papargyropoulou, E.; Lozano, R.; Steinberger, J.K.; Wright, N.; bin Ujang, Z. The food waste hierarchy as a framework for the management of food surplus and food waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 76, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azazz, A.M.; Elshaer, I.A. Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, social media usage and food waste intention: The role of excessive buying behavior and religiosity. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobaih, A.E.E. Excessive food buying in Saudi Arabia amid COVID-19: Examining the effects of perceived severity, religiosity, consumption culture and attitude toward behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alotaibi, B.A.; Kassem, H.S. Adoption of sustainable water management practices among farmers in Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why Do People Act Environmentally and What Are the Barriers to Pro-Environmental Behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. New Environmental Theories: Toward a Coherent Theory of Environmentally Significant Behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, W.; Hwang, K.; McDonald, S.; Oates, C.J. Sustainable Consumption: Green Consumer Behaviour When Purchasing Products. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable Food Consumption: Exploring the Consumer “Attitude–Behavioral Intention” Gap. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2006, 19, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty Years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A New Meta-Analysis of Psycho-Social Determinants of Pro-Environmental Behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denton, A. Voices for Environmental Action? Analyzing Narrative in Environmental Governance Networks in the Pacific Islands. Glob. Environ. Change 2017, 43, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D.; Mertig, A.G.; Jones, R.E. New Trends in Measuring Environmental Attitudes: Measuring Endorsement of the New Ecological Paradigm: A Revised Nep Scale. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldagari, S.; Kabir, S.F.; Fini, E.H. Investigating Aging Properties of Bitumen Modified with Polyethylene-Terephthalate Waste Plastic. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 173, 105687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alandia, G.; Rodriguez, J.P.; Jacobsen, S.E.; Bazile, D.; Condori, B. Global Expansion of Quinoa and Challenges for the Andean Region. Glob. Food Secur. 2020, 26, 100429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canova, L.; Bobbio, A.; Benincà, A.; Manganelli, A.M. Predicting Food Waste Avoidance: Analysis of an Extended Model of the Theory of Planned Behavior and of Relevant Beliefs. Ecol Food Nutr. 2024, 63, 539–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordono, L.S.; Flora, J.; Zanocco, C.; Boudet, H. Food Practice Lifestyles: Identification and Implications for Energy Sustainability. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, N. The Approach of Social Practice Theory Towards Sustainable Food Consumption: An Analysis of a Questionnaire Survey on Purchasing Behavior. J. Environ. Sociol. 2020, 26, 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.; Xu, S.; Hua, Y.; Li, M.; Tang, L.; Lin, Z. Impact of Knowledge-Attitude-Practice Model Nursing Based on Reproductive Health Education on Patients with Reproductive Tract Infections. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2025, 313, 114593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.