Abstract

The Qinling–Bashan mountainous region and its surrounding areas in Shaanxi Province constitute a critical ecological security barrier and significant socio-economic zone within China, currently experiencing mounting ecological stress from both natural processes and anthropogenic activities. This study proposes an ecological restoration zoning framework built upon assessments of ecological vulnerability (EV) and ecosystem service value (ESV). The InVEST model was used to quantify major ecosystem services, while the Vulnerability Scoping Diagram (VSD) model evaluated ecological vulnerability. Both the ESV and EV layers were classified using the natural breaks method and aggregated at the township level to delineate restoration zones. Unlike previous studies relying on subjective judgment, this study constructs a standardized ‘vulnerability–service value’ decision matrix for the Qinling–Bashan region, providing a clear technical pathway for spatial restoration. Key findings include the following: (1) Spatial Vulnerability Pattern: The Qinling and Bashan mountain cores exhibit predominantly low vulnerability (potential and slight), while severe vulnerability is concentrated in the urbanizing Guanzhong Plain, emphasizing the need for urban ecological restoration. (2) Dominant Ecosystem Services: Carbon storage and net primary productivity (NPP) together account for 93% of the total ESV, highlighting the importance of forest conservation for national climate regulation. (3) Zoning Strategy: Four functional zones were defined, with the largest being the ecological conservation zone (44.8%), while a smaller ecological restoration zone (2.8%) in urban peripheries requires targeted intervention.

1. Introduction

Ecosystems supply vital resources for human life and well-being, with their health directly influencing the availability and quality of these resources [1], thus supporting community livelihoods and economic stability [2]. In recent years, ecological and environmental issues have become a global focus [3,4]. Since the 20th century, rapid urbanization and industrialization have accelerated socio-economic development, yet irrational human activities have severely disturbed natural systems—altering human–land relationships, accelerating habitat loss, reducing biodiversity, and degrading ecosystem services [5]. In parallel, climate change has profoundly affected global ecosystems, further intensifying imbalances in ecosystem structure, function, and service provision, with potential consequences being habitat contraction, ecosystem health deterioration, and regional instability [6].

Mountain ecosystems are particularly vulnerable to the combined pressures of climate change and human activity because of their complex terrain, fragile ecological structure, and strong dependence on agricultural ecosystems and natural resources [7]. Globally, mountain regions such as the Andes, the Alps, and the Himalayas are experiencing concurrent stressors, including accelerated warming, glacier and snowpack retreat, hydrological regime shifts, habitat fragmentation, biodiversity loss, and intensified land use and development. Due to their steep environmental gradients and high habitat heterogeneity, mountain ecosystems respond sensitively to disturbances, and recent studies indicate that climate change and unsustainable land-use practices are weakening key ecosystem services such as water regulation, carbon storage, soil conservation, and biodiversity maintenance. These challenges are also evident in the Qinling–Bashan region of China [8].

In recent years, the Qinling–Bashan region has faced pronounced ecological pressures driven by climate change and rapid economic development, posing serious challenges to regional ecosystem health. The uneven spatiotemporal distribution of precipitation has intensified water scarcity in areas such as the Guanzhong Basin and increased the frequency of extreme climatic events. Meanwhile, rapid urbanization and industrial expansion have continuously elevated water demand, while non-point source pollution and infrastructure construction have further aggravated ecological degradation [9,10]. As a climatic and ecological transition zone between northern and southern China, and a nationally important water conservation area and ecological security barrier, the Qinling–Bashan region plays an irreplaceable role in China’s ecological security pattern. Its ecosystems are characterized by high ecological importance and a strong sensitivity to both climate variability and human disturbance, making the region a critical testing ground for ecological vulnerability assessment and restoration-oriented spatial zoning.

Ecological restoration is a key approach for recovering damaged ecosystem structure and function and for improving ecosystem services [11]. Ecological restoration zoning, in particular, provides a holistic and systematic basis for prioritizing interventions and supporting targeted environmental governance [12,13]. Considerable progress has been made in restoration zoning in the Qinling–Bashan region; however, due to the lack of unified technical standards, existing studies have employed diverse methods across spatial scales. Some studies rely on single indicators—such as ecological vulnerability [14] or ecosystem service supply–demand relationships [15]—which may oversimplify the region’s complex terrain and climatic conditions. Other studies delineate zones based on ecological source areas and conservation constraints (e.g., ecosystem services, habitats, protected areas, ecological red lines) [16], or integrate ecological risk/vulnerability within land-use analysis [17]. Nevertheless, three limitations remain prominent: (1) the absence of a unified zoning framework; (2) inconsistencies in indicator systems and evaluation methods; and (3) insufficient consideration of socio-economic disturbance and adaptive capacity. Accordingly, although prior work has generated valuable insights into ecological vulnerability patterns [18,19,20] and ecosystem service evaluation [21,22,23], an operable framework that explicitly couples socio-ecological vulnerability (including exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity) with ecosystem service value for restoration-oriented zoning is still lacking. In particular, few studies translate the integrated vulnerability–service relationship into transparent zoning rules that directly support restoration decision-making involving human–nature interactions.

To address this gap, this study integrates ecological vulnerability and ecosystem services within a unified analytical framework tailored to the ecological structure and functional characteristics of the Qinling–Bashan region. Ecological vulnerability reflects the sensitivity of regional systems to external disturbances and their recovery capacity [18], whereas ecosystem services represent ecological value and contributions to human well-being [19]. Coupling these two dimensions enables a more comprehensive identification of areas facing high ecological risk yet delivering critical functions, thereby improving the relevance of zoning for restoration prioritization. Traditional vulnerability evaluations typically prioritize physical–environmental indicators (slope, terrain variability, vegetative cover, erosion potential) while insufficiently addressing the socio-economic dimensions and coping mechanisms [24,25]. To overcome these limitations, we applied the VSD (Vulnerability Scoping Diagram) framework, which systematically deconstructs vulnerability into exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity components, enabling integrated socio-ecological analysis [26].

Moreover, while some studies have attempted to integrate vulnerability with ecosystem services, many have relied on simple overlay analysis or composite indices with limited interpretability and inconsistent combination rules. Here, we employ natural breaks classification, layer overlay, and township-level aggregation to construct an explicit and operational “vulnerability–service value” decision matrix. This matrix-based rule set is designed to enhance the transparency, reproducibility, and policy readiness of ecological restoration zoning, thereby strengthening the linkage between scientific assessment and spatial governance.

This study has important ecological, methodological, and policy implications. Ecologically, by jointly considering socio-ecological vulnerability and ecosystem service value, it provides a scientific basis for identifying priority restoration areas and enhancing ecosystem health, ecological security, and regional resilience in the Qinling–Bashan Mountains. Methodologically, it advances restoration-oriented spatial zoning by integrating the VSD framework with ecosystem service assessment and an explicit decision-matrix rule system to create a unified operational pathway [27]. From a policy perspective, the proposed zoning scheme offers direct technical support for territorial spatial planning, ecological conservation, and restoration decision-making, and provides a transferable reference for restoration planning in other vulnerable mountain regions.

Building on this foundation, the current study seeks to accomplish the following: (i) develop a comprehensive framework for ecological restoration zoning; (ii) examine the spatial distribution patterns of socio-ecological vulnerability and ecosystem service values; and (iii) delineate targeted ecological restoration zones and propose corresponding protection and restoration strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

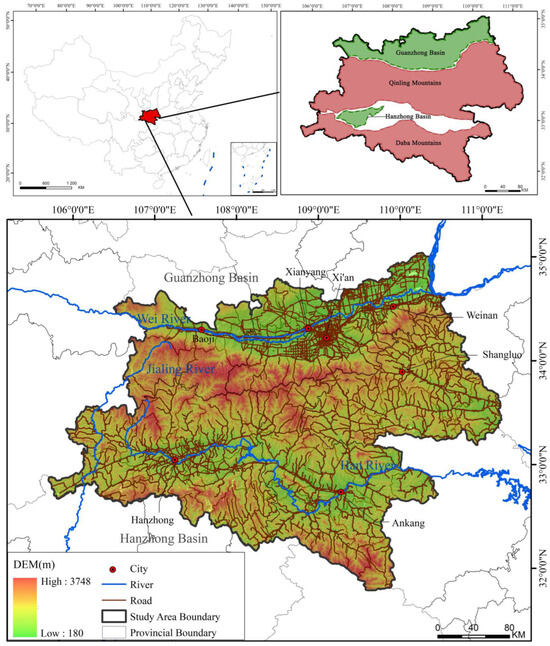

The research area is located within the territory of Shaanxi Province, China, mainly covering the Qinling Mountain Range and the basin areas on both its north and south sides, covering approximately 108,000 square kilometers (Figure 1). The southern boundary of the region is adjacent to the provincial boundary of Shaanxi, while the northern boundary extends to the northern boundary of the Guanzhong Plain. To accurately define the research scope, the boundary line is demarcated based on the county-level administrative divisions, which can more finely reflect the geographical and socio-economic characteristics of the region.

Figure 1.

Location of the study area.

This region holds exceptional strategic importance at the national scale for three critical reasons: (1) it is a key ecological barrier separating China’s northern and southern climatic zones and serving as the watershed between the Yellow River and Yangtze River basins; (2) it is a nationally recognized biodiversity hotspot harboring over 3800 plant species and numerous rare and endemic fauna, including the giant panda; and (3) it is a vital water-source region supplying both the Guanzhong urban cluster and the South-to-North Water Diversion Project, directly affecting water security for millions of residents across northern China [28].

As a geographic divide, the Qinling range demarcates the northern Yellow River basin from the southern Yangtze River basin, giving rise to distinctly different climate and hydrological regimes. These contrasts exert considerable influence on both ecological vulnerability and ecosystem service functions throughout the region. To the north, warm temperate monsoon conditions transition from semi-humid to semi-arid, and this zone represents the demographic, economic, and administrative center of Shaanxi Province. This confluence of intensive urbanization, agricultural expansion, and limited water availability elevates ecological vulnerability through habitat fragmentation and water stress. This simultaneously increases the exposure of densely populated areas to environmental risks.

Owing to its dense river network and adequate water conditions, the region can sustain diverse water demands associated with industrial development, agricultural irrigation, and daily domestic use. The Wei River traverses this region as one of the Yellow River’s principal tributaries, supplying critical freshwater that sustains both urban ecosystems and the dense population concentrated within the Guanzhong Basin. However, the semi-arid climate limits the region’s capacity for water yield and soil conservation services, making the northern slope particularly sensitive to climate variability and human disturbance.

The southern slope falls under a subtropical humid monsoon climate and is characterized by hilly terrain with long river courses and abundant water resources. These favorable climatic and topographic conditions support dense forest cover and high net primary productivity, resulting in substantially higher ecosystem service provision—particularly in carbon storage, water conservation, and biodiversity maintenance—compared to the northern slope. Several major Yangtze River tributaries—including the Jialing, Han, and Danjiang—originate within the study area, positioning it as a hydrologically significant region at both the regional and national scales. Its designation as a primary water source protection zone for the South-to-North Water Diversion Project underscores its vital function in providing dependable, clean surface water to northern regions and metropolitan areas, contributing fundamentally to China’s water security [29]. Despite its ecological advantages, the southern slope’s rugged topography and relatively lower population density create challenges for socio-economic development, resulting in lower adaptive capacity in some areas, while also reducing human-induced ecological vulnerability in core conservation zones. This north–south environmental gradient—characterized by contrasting climate, topography, land-use intensity, and socio-economic development patterns—creates spatially heterogeneous patterns of ecological vulnerability and ecosystem service capacity, which form the basis for the differentiated restoration zoning strategies developed in this study.

Focusing on the Qinling–Bashan Mountain area for ecological restoration zoning is essential due to its multifaceted strategic significance. As a nationally designated ecological security barrier, this region serves three irreplaceable functions: (1) Climate Regulation and Watershed Protection—acting as the natural dividing line between China’s subtropical and temperate zones while controlling water flow to two of the nation’s largest river systems; (2) Biodiversity Conservation Hotspot—exhibiting exceptional biological diversity, including vascular plant endemism exceeding 30%, and serving as a crucial refuge for several nationally protected flagship species, such as Ailuropoda melanoleuca (giant panda), Rhinopithecus roxellana, and Nipponia nippon; (3) Strategic Water Source Region—providing high-quality freshwater to over 100 million people through natural runoff and the South-to-North Water Diversion infrastructure, making it indispensable for national water security.

Beyond these ecological functions, the region supplies vital natural resources—including timber, medicinal plants, and agricultural land—that underpin socio-economic development in adjacent plains, creating complex human–nature interactions that necessitate scientifically informed restoration zoning. The development activities in these plains, including non-point source pollution and infrastructure construction, like roads, have profound impacts on the landscape, biodiversity, and ecological connectivity of the Qinling National Park.

Recent socio-economic growth has significantly increased water demand on both sides of the Qinling Mountains. The northern slope faces challenges like large fluctuations in surface runoff due to seasonal rainfall and insufficient water conservation capacity, potentially failing to meet the increasing water needs of the Guanzhong Basin in the future. The South-to-North Water Diversion Project further intertwines the water resource dynamics between the northern and southern slopes. Additionally, issues such as resource overexploitation and escalating pollution adversely affect water usage on the northern slope.

The southern slope experiences uneven social population distribution, leading to significant spatial differences in water resource utilization. Combined with the contradiction between relatively lagging economic development and regional ecological vulnerability, these factors pose major challenges to water resource security in the Qinling area. Addressing these issues necessitates conducting specific analyses of localized problems to formulate an effective ecological restoration zoning framework. By implementing targeted restoration measures, we aim to more effectively solve local environmental issues, alleviate the uneven spatial utilization of water resources, and improve the quality of life for residents, thereby promoting the harmonious coexistence of economic development and ecological protection [30].

2.2. Datasets

This study uses data from 2020 across key indicators—socio-economic, meteorological, vegetation, land use, and soil characteristics—harmonized to the WGS84 coordinate system at a 1 km resolution for consistent analysis.

- (1)

- DEM data

The DEM (Digital Elevation Model) data, with a spatial resolution of 30 m, were sourced from the Geospatial Data Cloud website (http://www.gscloud.cn/) (accessed on 23 July 2023).

- (2)

- Land use and land cover data

Land use classification was based on Landsat 8 imagery obtained from the Resource and Environment Science Data Center (Chinese Academy of Sciences). Eight land cover categories were identified: arable land, forest, grassland at three coverage levels (high, medium, and low), water bodies, urban built-up land, and unused land.

- (3)

- Meteorological data

Annual precipitation and mean temperature were obtained from the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Resource and Environment Science Data Center. Monthly solar radiation, average temperatures, and actual ET data came from the National Earth System Science Data Center, while potential ET data were accessed through the Global Aridity and PET Database.

- (4)

- Vegetation cover data

Vegetation coverage was characterized using NDVI derived from SPOT/VEGETATION imagery. The MVC technique was applied during data processing, which was carried out by the Resource and Environment Science Data Center (Chinese Academy of Sciences) to maintain data integrity and precision.

- (5)

- Socio-economic data

County administrative boundaries originated from the Shaanxi Surveying and Mapping Geographic Information Bureau, while demographic and economic indicators (population and GDP) were compiled from the Shaanxi Statistical Yearbook. These socio-economic variables were converted to a spatial format using IDW interpolation for compatibility with natural data layers. Spatially explicit population and GDP density datasets were obtained from the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Resource and Environment Science Data Center.

- (6)

- Soil data

This study mainly incorporates soil content data, obtained from the Harmonized World Soil Database, and root limit layer data, sourced from the Climate Change Data.

The main datasets used in this study, including their data sources, observation years, and spatial resolutions, are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of datasets used in this study.

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Ecological Vulnerability Calculation

- (1)

- Construction of the index system

In the study of ecological vulnerability, selecting an appropriate model is crucial for a scientific understanding of the vulnerability of ecosystems. The VSD (Vulnerability Scoping Diagram) model index, used to measure the overall vulnerability of ecosystems to various environmental stresses and disturbances, is widely applied in the construction and estimation of ecological vulnerability indicator systems due to its comprehensiveness and practicality.

The VSD framework is a theoretical tool focused on assessing the vulnerability of socio-ecological systems. This framework defines ecological vulnerability through three key aspects, including the degree of exposure to disturbances, inherent sensitivity, and capacity for adaptation [31,32]. This comprehensive approach ensures that multiple facets of vulnerability are considered, providing a holistic assessment of ecosystems facing environmental stress and change. The IPCC’s Fourth (AR4) and Fifth (AR5) Assessment Reports offer critical scientific insights into climate change, focusing on the key factors influencing it and potential response strategies. These two frameworks offer a scientific basis and policy reference for understanding global climate change. Unlike the IPCC framework, the VSD framework is a specialized theoretical tool for evaluating the vulnerability of socio-ecological systems. The VSD framework differs from IPCC approaches—which center on climate impact drivers and policy mechanisms—by providing integrated vulnerability assessment across three key dimensions: exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity. Its systematic and comprehensive design makes VSD especially effective for complex environmental assessments requiring the synthesis of multi-scale, multi-element information. It not only provides a clear assessment approach but also helps researchers and decision-makers identify and understand the vulnerability of socio-ecological systems under different environmental stresses, thus providing support for developing effective adaptation and mitigation strategies. Overall, both the VSD framework and the IPCC frameworks provide important scientific bases and tools for climate change research and policy formulation, but their focuses and application scopes differ significantly. The VSD framework’s integrated approach allows for a more nuanced understanding of vulnerability in specific socio-ecological contexts, complementing the broader assessments provided by the IPCC.

In this study, the indicator system’s construction follows three principles: each indicator must be validated through empirical research on ecological vulnerability and must reflect a key process in one of the three VSD dimensions; data sources must be reliable and at the township scale, covering the period around 2020; indicators must reflect the specific ecological and social coupling characteristics of the Qinling–Bashan Mountain region. Sensitivity indicators mainly represent factors that make the region more prone to soil erosion and ecological degradation. These are mostly natural factors. The Qinling–Bashan region is a transition zone between the northern and southern climates, and its vegetation is highly sensitive to disturbances. Therefore, NDVI reflects the sensitivity of the vegetation to climate and human activities. Exposure indicators refer to factors such as population density, GDP, water usage, pollution emissions, land use, and road density. These indicators reflect the region’s high population density, intensive urbanization and agriculture, significant industrial water use, wastewater discharge, and expansion of cultivated and construction land, which increase the ecological exposure level. Adaptability indicators (such as food production, fiscal income, and financial reserves) reflect the ability to invest in ecological restoration [33]. The amount of food production reflects the human system’s ability to respond to disturbances, thus being classified as an adaptability indicator.

Fifteen indicators were ultimately selected following an assessment of data accessibility and currency. For each indicator, its directional relationship with the criterion layer was established—positive correlations were labeled as ‘+’ type indicators, whereas negative correlations were assigned a ‘−’ designation. Table 1 provides comprehensive details of this classification. The corresponding formulas are expressed as follows:

An integrated ecological vulnerability index (V) was developed to reflect ecosystem susceptibility by accounting for exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity. The first two components increase vulnerability, while adaptive capacity counteracts vulnerability through its mitigating effect. Indicator layers were normalized and weighted to derive the three components, which were subsequently aggregated based on Equation (1) and normalized to obtain V. The resulting index was then classified into different vulnerability categories using the Natural Breaks (Jenks) approach [34].

- (2)

- Determination of indicator weights

The entropy weight method is a widely used technique for determining the relative importance of factors or indicators in multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) problems. It is based on the concept of entropy, which measures the uncertainty or disorder within a dataset. In this method, the weight of each factor is inversely proportional to the entropy value of that factor. A higher entropy indicates more uncertainty, meaning the factor has less weight in the final decision, while a lower entropy indicates a more certain factor, meaning it has a higher weight. This method allows for an objective determination of the importance of each factor without the need for subjective judgment [35]. This study applied the entropy weight method to assign suitable weights to various ecological and socio-economic factors during the ecological restoration zoning process. This method is particularly useful when we need to aggregate various indicators with different dimensions or units, ensuring that each factor contributes proportionally based on its relative importance. To eliminate dimensional differences among indicators, we applied range normalization (i.e., the min–max method) to transform all variables into comparable dimensionless values. Indicator weights are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Indicator system and weights of ecological vulnerability assessment in the study area.

For indicators with a positive correlation, the formula for the normalization process is as follows:

For indicators with a negative correlation, the formula for the normalization process is as follows:

is used to describe the normalized value of indicator i at grid cell j. The normalization is based on the original indicator value x and its observed maximum and minimum .

2.3.2. Ecosystem Service Estimation

Ecosystem service estimation is essential for evaluating the benefits ecosystems provide to society, such as windbreaks and sand fixation, soil conservation, water source conservation, and biodiversity maintenance. An ecosystem service assessment was conducted using the InVEST modeling framework, which enables the quantitative evaluation of multiple ecosystem functions. The analysis focused on food supply, carbon storage, water source conservation, soil conservation, and vegetation net primary productivity (NPP), given their relevance to ecosystem productivity, food security, climate regulation, hydrological balance, and soil integrity. The InVEST framework was jointly developed by Stanford University, the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), and The Nature Conservancy (TNC). The assessment provides critical insights to guide policymakers and resource managers in developing ecological protection and resource management strategies, thereby fostering sustainable regional development. The selected services encompass key ecosystem benefits in the area [36], and the evaluation method is as follows:

- (1)

- Food supply service

Food supply is vital for human survival, with its value based on production volume. Utilizing the 2020 Shaanxi Statistical Yearbook, national agricultural data, and local records, which report an average grain price of 2.32 yuan/kg, this study correlates ecosystem food supply capacity with NDVI and land use types [37]. It estimates the food supply through land use, referencing regional data, and assesses spatial distribution. The formula for calculation is as follows:

In the formula, FSx represents the food supply yield of grid cell x, NDVI represents the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) corresponding to land use type j, NDVIsumj represents the sum of the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index for land use type j, and Ssumj represents the agricultural product yield corresponding to land use type j. Here, cereal grains are the main products of arable land, meat products originate from pastureland, and aquatic products are the output of water body land use.

- (2)

- Carbon storage service

Carbon storage, facilitated by photosynthesis in vegetation, is a key ecosystem service that absorbs atmospheric CO2 and releases an equivalent volume of O2, with a quantifiable ratio of 2.67 g of oxygen per gram of carbon fixed. This study calculates the value of carbon sequestration services using the carbon tax method, valuing 1 ton of carbon at approximately 940 yuan. The market value method is applied to estimate the value of oxygen release, with the national price set at 460 yuan per ton [38]. In this study, carbon storage in the Qinling–Bashan Mountain area is categorized into four pools: aboveground biomass (stems, branches, bark, leaves), belowground biomass (roots), soil carbon (organic matter in soils), and dead organic carbon (the carbon in plant materials that have fallen and have not yet been completely decomposed by microorganisms) [39]. Carbon storage was quantified using 2020 land use data as a reference, with estimates derived from land-type-specific carbon density values. The computational approach is given below:

where C denotes total carbon storage for the study area or assessment unit; and represent aboveground and belowground carbon pools, respectively; indicates soil carbon content; and refers to carbon stored in dead organic matter. The carbon intensity of different types of land use is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Carbon intensity of different types of land use (Mg/ha).

- (3)

- Water source conservation service

Water source conservation is essential for sustainable societal development, with ecosystems playing a key role in water cycle regulation and availability. The Qinling–Bashan Mountain area’s southern slope, a vital water source region in China, significantly impacts local water security. This study utilizes the Budyko model with annual precipitation data to assess the water conservation service, considering factors like precipitation, evapotranspiration, and vegetation cover [40].

The variable Yxj represents water yield at grid cell x, derived from land use type j for water conservation assessment. P(x) and AETxj correspond to annual precipitation and evapotranspiration, respectively, while w_x integrates climate–soil characteristics. Moisture availability is characterized by the dryness index—the ratio of potential to actual precipitation—for each land–vegetation combination. Vegetation-specific water loss is adjusted through kxj, and Z (Zhang coefficient) parameterizes seasonal rainfall distribution. Soil water accessible to plants (PAWC) at grid cell x is constrained by either soil depth (MaxSoilDepthx) or root penetration depth (RootDepthx), whichever is smaller. Textural components (sand, silt, clay) and organic matter content were extracted from the Chinese Soil Database (http://vdb3.soil.csdb.cn/) (accessed on 1 July 2023). All relevant spatial parameters, including land-use-dependent root depths and evapotranspiration coefficients (Kxj), are listed in Table 4 and were configured within the InVEST Water Yield Module.

Table 4.

Parameters of the InVEST Water Production Module.

To quantify the value of water source conservation services, methods such as the shadow engineering method and market price method are commonly used. This paper employs the shadow engineering method to simulate the water retention and regulation function of reservoirs, and their value is assessed by considering the construction cost of reservoir capacity. Referring to relevant technical standards such as the “China Water Conservancy Yearbook” [41], it is understood that the construction cost of reservoir capacity in China is 6.2 yuan per cubic meter. The method for calculating the value of water source conservation is as follows:

Here, the total economic worth of water conservation services is expressed as VP (yuan), while Yxj captures the water retention amount at grid cell x. The parameter P represents reservoir construction costs per unit volume (yuan/m3).

- (4)

- Soil conservation service

The soil conservation service describes the ecological function that prevents nutrient loss and sediment accumulation in the soil, thereby preserving soil fertility and maintaining water–soil resources within a given region. This ecosystem service emerges from complex interactions among topographic features, climate patterns, vegetative cover, soil characteristics, and anthropogenic influences. Following the Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation (RUSLE), we quantified soil conservation as the difference between potential and actual soil erosion rates [42,43].

Within soil conservation assessment, determining slope length and gradient factors constitutes an essential component of erosion risk evaluation. The slope length factor (L) captures how slope distance influences erosion intensity. Its computation requires two inputs: λ, representing the horizontal distance of overland water flow, and m, the slope length exponent derived from slope steepness through empirical relationships or published values. As slope length increases, the L factor rises correspondingly, indicating greater erosion susceptibility on extended slopes. The relevant formulas are presented below:

λ: slope length (m), representing the horizontal flow distance of runoff; θ: slope angle (degrees), derived from the DEM; m: slope length index, determined according to the empirical relationship between slope steepness and erosion sensitivity.

The slope gradient factor represents the effect of slope steepness (gradient) on soil erosion. The calculation of the slope gradient factor requires the following steps: using DEM data, converting the slope gradient data from degrees to radians by multiplying by π/180, and, based on the slope gradient data, using the following formula to calculate the slope gradient factor S, where θ represents the slope gradient in radians:

Soil erosion at the grid cell level is characterized by three metrics: actual erosion (SDRm), potential erosion (SDRp), and soil conservation capacity (SC), all expressed in t·hm−2·a−1. The rainfall erosivity factor (R) reflects the erosive potential of intense precipitation events and was computed using Wischmeier’s empirical model based on multi-year monthly mean rainfall data [44]. P denotes the support practice factor. Soil erodibility (K), indicating soil susceptibility to detachment by rainfall and runoff, was derived following Williams’ approach using soil organic carbon information [45]. Topographic influences were captured through slope length (L) and slope steepness (S) factors. The cover-management factor (C) expresses the ratio of erosion under the existing land management relative to continuous bare fallow conditions.

The soil conservation service mitigates erosion-related ecological issues, enhancing soil fertility and reducing river siltation. Its ecological value lies in cutting silt deposition and sustaining soil fertility. The estimation of the value of soil conservation services can be calculated using the following formula:

In the formula: vs. represents the value of soil conservation (in yuan), Vsoil is the value of reducing silt deposition (in yuan), Vnutrition is the value of maintaining soil fertility (in yuan), A(x) is the proportional coefficient for the reduction in silt deposition, with a value of 24%; ρ is the soil bulk density (in t/m3), with a value of 0.82; Cn represents the content of the nutrients nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium in the soil, with values of 0.1%, 0.04%, and 1.5%, respectively; Vx is the unit price for the reduction in silt deposition (in yuan/m3), with a value of 17.39; V(n) represents the unit prices for nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium in 2015 (in yuan/t), with values of 1250, 2286, and 653, respectively [44].

- (5)

- Vegetation net primary productivity service

Vegetation NPP indicates the organic matter production capacity of green vegetation, representing the net output from photosynthesis minus plant respiration. Critical in ecosystem material cycling and energy flow, this study applies the CASA model to calculate the study area’s NPP [45].

Three parameters define the productivity calculation: NPP(x,t) for spatiotemporal vegetation productivity at cell x and month t; APAR(x,t) for monthly intercepted photosynthetic radiation (MJ/m2·yr−1); and ε for the radiation use efficiency (gC/MJ).

To quantify the value of organic matter created by net primary productivity, this paper adopts the energy equivalent method as an alternative to the traditional replacement value method. Through this approach, the net vegetation primary productivity can be converted into a measure of organic matter production, and then the service value of net vegetation primary productivity in a specific area can be estimated and quantified using the replacement value method, with reference to the market value of standard coal. The following is the calculation method for the service value of net vegetation primary productivity:

In this equation, Vom quantifies the aggregate economic worth of net vegetation productivity (yuan); NPP(x) measures the yearly organic matter generation per grid cell x (gC/m2·a−1); Ax serves as the organic carbon conversion coefficient; C is the organic carbon mass (t); and Pom reflects the market valuation of plant-produced organic matter (yuan/t). Applying the replacement cost methodology, conversion factors were established as follows: a biological carbon to organic matter ratio of 1:2.2, and an organic matter to standard coal energy equivalent of 1:0.067. Consequently, each gram of biological carbon corresponds to 1.494 g of standard coal. Economic valuation utilized the 2015 standard coal market price of 520 yuan/t [46].

The main parameters, calculation approaches, and key references for the five ecosystem services are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Main parameters, calculation approaches, and key references for the five ecosystem services.

2.3.3. Ecological Restoration Zoning Procedure

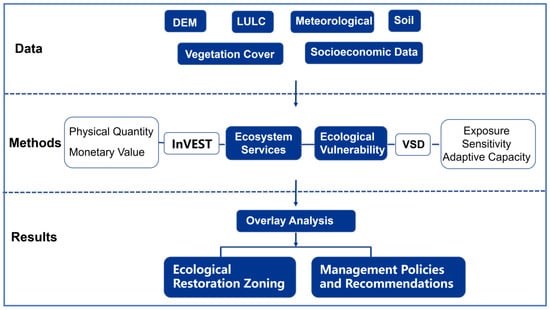

This section outlines the technical procedure used to identify and delineate ecological restoration zones, integrating ecological vulnerability and ecosystem service values. The procedure consists of three primary steps:

- (1)

- Ecological vulnerability and ecosystem service values were classified at the pixel level using ArcGIS 10.5, applying the natural breaks method for both.

- (2)

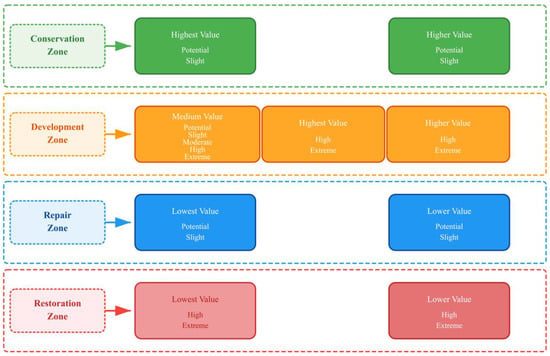

- Overlaying and Analyzing Layers: The classified layers for ecological vulnerability and ecosystem services were overlaid and analyzed to identify regions with different combinations of vulnerability and service levels (Table 6).

Table 6. Zoning basis for ecological restoration.

Table 6. Zoning basis for ecological restoration. - (3)

- Pixel-based zoning results often appear fragmented and are less practical for regional planning. Therefore, we aggregated the zoning results to the township scale using a majority-area principle:

For each township, the area proportion of the four zoning categories was calculated.

The category with the largest area proportion was assigned as the township’s dominant ecological restoration zone.

Minor fragmented patches were smoothed to improve spatial coherence and enhance applicability for ecological management. The methodology is illustrated in Figure 2, which shows the flow of the entire process.

Figure 2.

Methodological flowchart.

3. Results

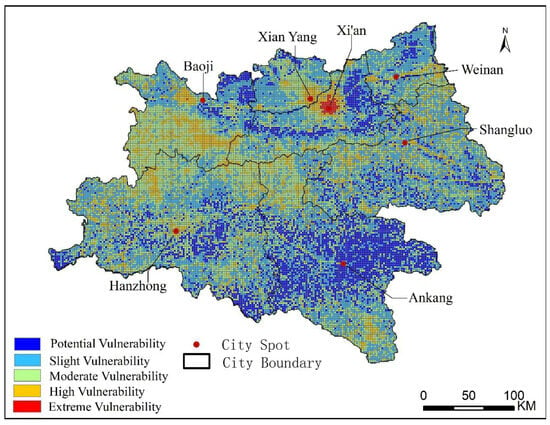

3.1. Spatial Distribution Characteristics of Ecological Vulnerability

The spatial distribution of ecological vulnerability in 2020 (Figure 3, Table 7) shows clear spatial differentiation between urban and mountain areas. Extreme and high vulnerability (12.7% combined) is concentrated in the Xi’an city center and the Hanzhong urban area, where population density exceeds 1000 persons/km2, land is predominantly used for construction, and industrial activities are intensive. In contrast, low vulnerability (55.8%: potential 18.9% + slight 36.9%) is found mainly in the Qinling and Bashan mountain areas, which are dominated by forest cover with limited human activities. Moderate vulnerability (31.5%) occurs primarily in agricultural lands between urban centers and mountain areas, particularly in the Guanzhong Plain and around the Hanzhong Basin. This spatial pattern reflects the north–south environmental differences described in Section 2.1: the Guanzhong Plain in the north has a semi-arid climate and high population density, while the southern mountains have a humid climate and dense forests.

Figure 3.

Ecological vulnerability spatial distribution map in 2020.

Table 7.

Area proportion of each ecological vulnerability level.

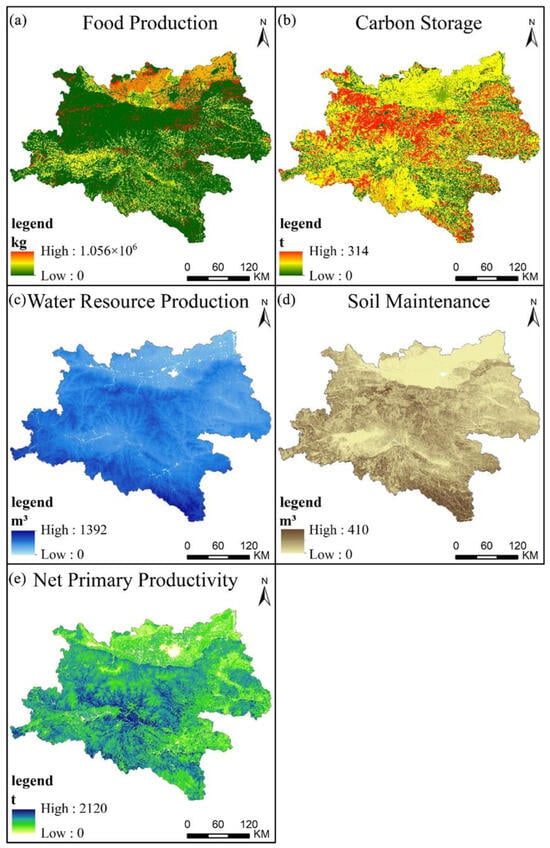

3.2. Ecosystem Service Quantification

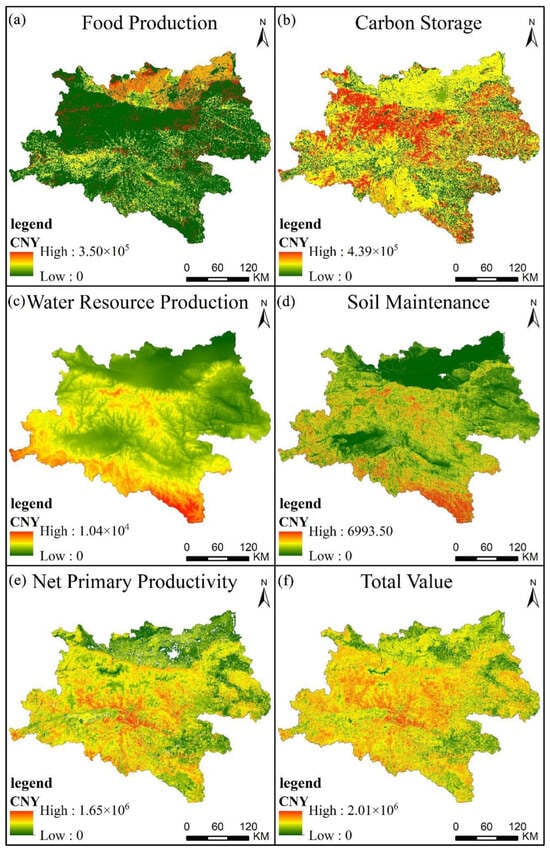

The spatial distribution of the quantity and value of ecosystem services is shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5, respectively, with the quantity and value showing a basically consistent pattern.

Figure 4.

Spatial distribution of the quantity of ecosystem services in 2020.

Figure 5.

Spatial distribution of the value of ecosystem services in 2020 (unit: CNY·km−2·yr−1).

- (1)

- Food supply service

In 2020, the study area’s food supply totaled 1.09 million tons (Figure 4a), with an economic value of CNY 4.976 billion (Figure 5a). The spatial distribution follows a north–south gradient, with higher values in the northern Guanzhong Basin, especially in Xianyang and Weinan, where arable land is primarily used for wheat, soybean, and corn cultivation. The Hanzhong Basin and parts of Ankang show moderate values from wheat and rice cultivation. Mountain areas and the Xi’an urban core show low values due to limited agricultural land.

- (2)

- Carbon storage service

In 2020, the carbon sequestration (carbon storage) service value of the Qinling–Bashan region was CNY 17.056 billion (Figure 5b). High values are found in the Qinling and Bashan mountains, where forest and grassland ecosystems dominate. Low values occur in the Guanzhong and Hanzhong Basins, where construction land and reduced vegetation predominate. The spatial pattern relates to vegetation density and land use intensity.

- (3)

- Water source conservation service

In 2020, the total water conservation volume in the study area reached 572 million m3 (Figure 4c), corresponding to an economic value of CNY 0.566 billion (Figure 5c). The spatial distribution characteristics of water source conservation volume are closely related to the water vapor source conditions, topography, and vegetation coverage of the study area. Spatially, regions with higher water source conservation are primarily concentrated in the Bashan Mountain area and the main peaks of the Qinling Mountains. Overall, the water source conservation capacity of the Bashan Mountain area is slightly higher than that of the Qinling Mountain area. This may be because the Bashan Mountain area can meet the marine water vapor brought by the South Asian and East Asian monsoons earlier, and due to the blocking effect of the mountain massif, it has more sources of precipitation. Additionally, both the Bashan and Qinling Mountain areas are dominated by forests and grasslands with high vegetation coverage, where the vegetation cover is good, which can conserve abundant precipitation. In contrast, the central urban areas of the Guanzhong Basin on the northern side of the Qinling Mountains and the urban areas along the river valleys on the southern slope have relatively lower water source conservation volumes, with some areas almost reaching zero. These areas are primarily designated for construction, with frequent human activity, extensive arable and industrial land, and lower vegetation cover, resulting in a decreased capacity for water source conservation.

- (4)

- Soil conservation service

In 2020, soil conservation within the study area totaled 1.369 billion tons (Figure 4d), with an associated economic worth of CNY 0.361 billion (Figure 5d). A clear topographic gradient emerged in the spatial distribution: the lowland basins of Guanzhong and Hanzhong exhibited minimal conservation capacity, contrasting sharply with the high-retention mountainous zones. The Bashan Mountains showed slightly greater soil retention compared to the adjacent Qinling range. Such spatial variation can be attributed to the corresponding distributions of vegetation coverage and precipitation intensity throughout the study area.

- (5)

- Vegetation net primary productivity service

In 2020, the economic value of vegetation net primary productivity (NPP) in the Qinling–Bashan region reached CNY 62.289 billion. NPP is notably higher in the transitional zones of the Qinling and Bashan Mountains and the plains, where dense vegetation and fertile soils contribute to higher productivity. In contrast, urban clusters in the Guanzhong Basin exhibit lower NPP values, with extensive construction and human activities potentially suppressing vegetation growth and productivity.

- (6)

- Total value of ecosystem services

The total ecosystem service value (ESV) in 2020 was CNY 85.4 billion (Figure 4 and Figure 5). Net primary productivity (CNY 62.3 billion, 73.0%) and carbon storage (CNY 17.1 billion, 20.0%) together accounted for approximately 93% of the total ESV, indicating their dominant contributions to ecosystem service provision in the study area. High ESV areas are mainly located in the Qinling and Bashan mountains, where forest cover exceeds 70%, and ESVs are generally higher than CNY 800,000·km−2·yr−1. In contrast, low ESV areas are concentrated in the Guanzhong Basin and Hanzhong Basin, including the Xi’an metropolitan area, where vegetation cover is generally below 30%. ESV in urban core areas is lower than CNY 100,000·km−2·yr−1, accounting for only about 10% of mountain values. Water conservation (CNY 0.57 billion, 0.7%) and soil retention (CNY 0.36 billion, 0.4%) exhibit spatial patterns similar to those of carbon storage and NPP, with higher values in mountainous areas. The Bashan Mountains show slightly higher values than the Qinling Mountains, likely due to greater precipitation. In contrast, food supply services (CNY 5.0 billion, 5.9%) display an opposite spatial pattern, with higher values concentrated in agricultural plains.

3.3. Ecological Restoration Zoning

Identifying and measuring key areas for ecological restoration is crucial for developing rational and optimized ecological restoration strategies. This paper’s ecological restoration zoning integrates the current state of systematic assessment of ecological vulnerability and ecosystem service, the orientation of national development strategies, and the actual needs of local socio-economic development. It considers multiple dimensions such as the natural conditions, ecological foundation characteristics, and the level of socio-economic development of the study area.

The synthesis of vulnerability and ecosystem service assessments enables their classification into four management units with distinct restoration priorities. These units—spanning conservation through active restoration interventions—are defined according to criteria outlined in Figure 5, with their geographic distribution mapped in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of ecological restoration zoning.

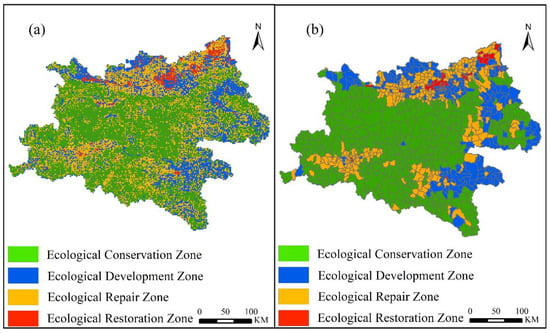

Figure 7a: Ecological restoration zoning results based on pixel calculations. This figure displays ecological restoration zones at the high-resolution grid level, reflecting the fine spatial distribution of ecological vulnerability and ecosystem service values. Figure 7b: Ecological restoration zoning results based on township units. This figure, built upon Figure 7a, merges and adjusts the results using townships as basic units, generating more practical and coherent ecological restoration zones.

Figure 7.

Ecological restoration zoning. (a) pixel-level zoning map; (b) township-level zoning map obtained by aggregating and adjusting the pixel-based results.

The area distribution of LUCC types across the four ecological restoration zones is summarized in Table 8.

Table 8.

Area distribution of LUCC types across ecological restoration zones (km2).

- (1)

- Ecological restoration zone (2.8%, 2820 km2)

This zone mainly covers areas with low ecosystem service and high ecological vulnerability, which are under significant pressure from ecological environment deterioration (Figure 7). The area covers 2820 km2, representing 2.8% of the total study area, and is primarily located near cities in the Guanzhong Basin on the northern slope of the Qinling Mountains. Land use is dominated by urban construction (28.7%, 810 km2) and agricultural land (48.6%, 1370 km2), followed by grassland (17.8%, 503 km2). Forest land makes up only a small portion (3.5%, 100 km2), reflecting a generally weak ecological baseline. As a result, ecosystem services in the region are severely degraded, with low levels of carbon storage, net primary productivity (NPP), and water conservation capacity, and limited provisioning services. Meanwhile, driven by intensive urbanization, high population density, and concentrated heavy industrial activities, the region exhibits high to extreme ecological vulnerability.

- (2)

- Ecological repair zone (31.0%, 31,584 km2)

Intermediate ecosystem service capacity coupled with spatially differentiated vulnerability characterizes this 31,584 km2 zone (31.0% of total area; Figure 7). Its geographic extent includes Guanzhong’s central–eastern lowlands, the intermontane Hanzhong depression, and the Ankang region’s western margin. Nearly seven-tenths of the landscape supports either cultivation or grazing activities, while forested terrain covers roughly one-quarter. Urban development remains limited. Regulating services—carbon sequestration, watershed protection, soil stabilization—function at moderate intensity, whereas provisioning services, especially crop production, show greater prominence. Multiple stressors—farming intensity, land use heterogeneity, and peri-urban pressures—collectively maintain elevated vulnerability across this transitional zone.

- (3)

- Ecological development zone (21.5%, 21,909 km2)

This zone is mainly located in the western Guanzhong Basin (Baoji and northern Xianyang) and the southeastern areas (Ankang and Shangluo). Overall, both ecosystem service value (ESV) and ecological vulnerability are relatively low. Land use is dominated by grassland (40.8%, 8945 km2) and agricultural land (36.3%, 7960 km2), followed by forest land (17.6%, 3850 km2), while urban land accounts for a small proportion (4.9%, 1080 km2). As a result, the ecological baseline of the region is relatively weak; however, the intensity of human development activities is low, and direct disturbances to ecosystems remain limited, resulting in relatively low urgency for ecological protection. Overall, the region has potential for ecological development and is suitable for moderate-scale construction activities. During the development process, strict adherence to ecological protection red lines is essential to enhance ecosystem service functions without damaging the local ecological environment, thereby achieving coordinated ecological and economic benefits (Figure 7).

- (4)

- Ecological conservation zone (44.8%, 45,616 km2)

This zone primarily includes areas with high ecosystem services and low ecological vulnerability, where stringent protection measures are essential to maintain the stability of ecological functions. The focus here is on effectively preserving biodiversity and ecological services while preventing any potential degradation of ecological functions (Figure 7). The area spans roughly 45,616 km2, representing 44.8% of the total study area, and is primarily located in the Qinling and Bashan Mountain regions in the southern part of the study area. Land use is dominated by forest land (43.6%, 19,905 km2) and grassland/meadow (36.8%, 16,800 km2), with agricultural land accounting for 19.2% (8775 km2). Influenced by this land use pattern, ecosystem services in the region are primarily driven by carbon storage and net primary productivity (NPP), which together contribute more than 75% of the regional carbon sequestration and biomass production, while water conservation and soil retention functions also remain at relatively high levels. Benefiting from relatively intact forest cover, low intensity of human disturbance, and favorable hydroclimatic conditions, the overall ecological vulnerability of the region is low, mainly characterized by potential and slight vulnerability levels.

Specifically, the ecological development zones are mainly found in the northwest of Baoji City, the northern parts of Xianyang City, the southern areas of Xi’an and Weinan Cities, as well as the southeastern parts of Ankang City and the Shangluo area. These regions feature relatively favorable ecological environments and significant development potential, making them ideal for fostering ecological economic growth and the sustainable use of resources. The ecological conservation zones cover most of the study area, particularly the central and western parts of the Qinling Mountains and the Daba Mountain region. These areas have high ecosystem service values and play a critical role in biodiversity and ecological security, serving as the core areas for maintaining regional ecological stability. The ecological repair zones are primarily located in the northern Qinling area of the Guanzhong Plain, the southern slopes of the Hanzhong Basin, and the central parts of Ankang City. These areas are in urgent need of restoration due to the impacts of ecological degradation, but they have the potential for sustainable recovery through green development and ecological restoration. Finally, the ecological restoration zones are concentrated in the urban core areas of Xi’an and the eastern parts of Weinan. These highly urbanized areas face significant anthropogenic pressure and require ecological restoration to enhance their ecological functions and improve their environmental quality.

4. Discussion

4.1. Prominent Ecological Issues in Various Zones

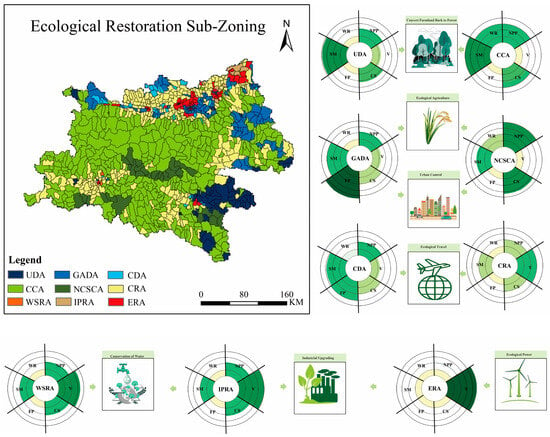

In the current research landscape, there is a growing understanding and emphasis on ecosystem services. However, most studies tend to focus on specific ecosystems or environmental issues, with relatively limited research on ecological restoration zoning [47,48]. Compared to previous studies, a key feature of this study is that it not only considers the dominant role of various ecosystems within the broader environmental system but also places a strong emphasis on their ecological vulnerability. This nuanced approach allows for a more accurate identification of the specific contributions of different ecosystems to human well-being, thereby enabling the development of more targeted and effective recommendations for ecological restoration. This study divides the region into four main ecological function zones: Ecological Development Zone, Ecological Repair Zone, Ecological Conservation Zone, and Ecological Restoration Zone. Based on the characteristics of each zone, further refinements are made. The Ecological Development Zone is subdivided into three categories based on development goals: Urban Development Area (UDA), Green Agriculture Development Area (GADA), and Comprehensive Development Area (CDA). The Ecological Conservation Zone is divided into two sub-zones: Comprehensive Conservation Area (CCA) and Net Primary Productivity–Carbon Storage Conservation Area (NSCCA). The Ecological Repair Zone is further categorized into three areas: Water Source Restoration Area (CRA), Industrial Pollution Restoration Area (ESVRA), and Comprehensive Restoration Area.

For the Development and Conservation Zones, the focus is on identifying areas with high ecosystem service values. These areas have low ecological vulnerability, and the zoning differences primarily focus on enhancing ecosystem service functions. The goal is to clearly define the dominant service types in each sub-zone and develop differentiated development strategies accordingly. In contrast, the Repair and Restoration Zones exhibit high vulnerability characteristics. These areas require an in-depth investigation into their causes of vulnerability, particularly focusing on high-risk regions. These strategies aim to address identified vulnerabilities by enhancing ecosystem service functions. Radar charts are used to visually compare ecosystem services and vulnerabilities in each sub-zone, helping to determine which dominant service types should be prioritized for each sub-zone. This tool also effectively reveals the imbalance between high-risk areas and their corresponding service functions.

Differentiated Development Strategies: For low-vulnerability areas (Development and Conservation Zones), the strategy focuses on strengthening existing ecosystem service functions to improve productivity, sustainability, and resilience. For high-vulnerability areas (Repair and Restoration Zones), targeted interventions based on specific vulnerability characteristics are needed. These interventions should rely on ecosystem service functions to reduce risks and improve ecological balance. Here is the explanation for each zone, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Ecological restoration sub-zoning.

Urban Development Area (UDA): Located near urban centers, this area is suitable for urban construction and development due to its high level of urbanization. The ecosystem service evaluation of this area shows strong performance in Soil Maintenance (SM), Net Primary Productivity (NPP), and Carbon Storage (CS), indicating that the region has significant advantages in maintaining its soil quality, vegetation productivity, and carbon sequestration functions. In contrast, Food Production (FP) and Water Resource Conservation (WR) are relatively weak, reflecting the need to improve agricultural production efficiency and water resource management capabilities. Notably, the ecological vulnerability (V) of this area is low, meaning that ecological risks are generally manageable. The current focus should be on enhancing FP and WR functions while maintaining the existing advantages in SM, NPP, and CS to achieve a balanced development of ecosystem services. Specific optimization measures include the following: Enhancing Food Production (FP): Due to urbanization, a significant amount of agricultural land has been occupied, resulting in a low local food self-sufficiency rate. To address this, urban agriculture should be developed by promoting rooftop farms, community gardens, and vertical farming, utilizing idle urban spaces to grow fruits and vegetables. Strengthening Water Resource Conservation (WR): Currently, the high proportion of urbanized surfaces accelerates rainwater runoff and insufficient groundwater recharge. To tackle this, sponge city facilities should be built to enhance water retention and promote sustainable water management.

Green Agriculture Development Area (GADA): This area is in a region with concentrated human economic activity and serves as a crucial source of food supply. It has been designated as a key area for green ecological agricultural development. The main services of the Green Agriculture Development Area (GADA) are Food Production (FP) and Soil Maintenance (SM), while Water Resource Conservation (WR), Net Primary Productivity (NPP), and Carbon Storage (CS) are relatively lower, and Vulnerability (V) is also at a low level. To enhance food production capacity and ensure food security, this study recommends drawing from successful experiences in other regions and promoting the application of sustainable agricultural technologies. Specific optimization measures include promoting ecological agriculture, organic farming, and precision agriculture models; reducing the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides to lower soil and water pollution; increasing the added value of agricultural products, promoting agricultural output diversification, and improving the efficiency of land utilization; and avoiding excessive land development, maintaining soil health, and ensuring water quality is not polluted. These measures will not only improve food production efficiency but also ensure the long-term sustainability of the regional ecological environment.

Comprehensive Development Area (CDA): The core governance objective of the integrated development zone should be to comprehensively protect and restore natural ecosystems, particularly by maintaining biodiversity and ensuring the sustainable use of natural resources [49], while simultaneously promoting the coordinated development of the regional economy and society. Given that the region’s ecosystem service value is relatively high and stable, balancing ecological protection with economic development is particularly important. To achieve this goal, it is recommended to closely integrate ecological protection with economic development and promote a green transition. For instance, ecological compensation mechanisms can be implemented to offset the economic losses caused by ecological protection efforts, and the industrial structure can be optimized to encourage traditional industries to shift towards greener and lower-carbon alternatives. Additionally, developing eco-tourism and other green industries can not only stimulate local economic growth but also raise public awareness about the importance of ecological protection, thus fostering the long-term sustainable development of the region [50].

Comprehensive Conservation Area (CCA): The comprehensive conservation area has a high ecological value balanced with low ecological vulnerability, making it suitable as a core area for comprehensive ecosystem protection. The main task in this area is ecological conservation, not increasing agricultural production. The focus is on protecting and maintaining the original functions of its ecosystems, ensuring a sustainable supply of natural resources and ecosystem services. By reducing human activity that interferes with the ecological environment, the conservation area should maintain the health and stability of the ecosystem. In this context, soil conservation is the area’s primary service, with strong soil conservation capacity. Therefore, this area is ideal for concentrating efforts on protecting soil resources and ensuring the continued ecological function of the land. Additionally, the integrated protection area has a relatively balanced ecosystem service value, supporting both agricultural production and ecological stability, making it a key incentive for the region’s sustainable development [51]. The combination of these attributes reinforces the role of the Comprehensive Conservation Area as essential for long-term ecological health, supporting both ecological and socio-economic objectives.

NPP—Carbon Storage Conservation Area (NCSCA): Compared to the Comprehensive Conservation Area, the NPP—Carbon Storage Conservation Area (NCSCA) places greater emphasis on net primary productivity (NPP) and carbon storage (CS), focusing on the protection and maintenance of ecological carbon sink functions. The ecological functions of this area are directly linked to core services such as biodiversity conservation, climate regulation, and soil and water conservation, and have significant impacts on global ecological balance [11]. Therefore, a series of integrated protection measures is required. First, the protection of existing carbon sinks should be strengthened to prevent human activities from weakening carbon storage capacity. Second, regular monitoring of NPP and other ecosystem dynamics is necessary to track trends and changes. Finally, the establishment of protected areas, the implementation of ecological migration policies, and a focus on protecting key ecological areas such as wetlands and forests are essential. Limiting human activities and reducing ecological pressure will be crucial. These measures will help sustain regional ecological functions and contribute to global ecological stability.

Water Source Repair Area (WSRA): In the water source repair area surrounding Hanzhong, ecological vulnerability is high, mainly due to wastewater discharge that pollutes water quality. As an important water source for the South-to-North Water Diversion Project (Central Route), water resource protection in this region is crucial. To reduce water pollution, key measures should be taken to control industrial, agricultural, and domestic wastewater discharge, promote wastewater treatment technologies, and improve water quality to ensure the sustainable supply of water resources. Additionally, restoring wetlands and aquatic plants can enhance the self-purification capacity of water sources. Water-saving technologies and devices should also be promoted to reduce water wastage and improve water resource use efficiency. These measures will help improve water quality, ensure the sustainable supply of water resources, and contribute to the healthy development of the regional ecological environment.

Industrial Pollution Repair Area (IPRA): The Industrial Pollution Repair Area is located around Weinan City, one of the major industrial bases in Shaanxi Province, and faces high ecological vulnerability primarily due to the impact of industrial pollution. The emissions of industrial gases, wastewater, and solid waste pose a serious threat to the ecosystem functions in the area. To control industrial pollution, it is essential to strengthen pollution source management, enhance waste treatment capacity, reduce industrial emissions, and encourage businesses to adopt environmentally friendly technologies for green production. Additionally, industrial upgrading should be promoted to decrease the proportion of high-pollution and high-energy consumption industries, while developing clean energy and environmentally friendly industries to drive a low-carbon economy. Furthermore, ecological restoration should be carried out on severely polluted land and water bodies to restore ecosystem functions, promote vegetation recovery, and soil remediation, thus improving the stability of the ecosystem.

Comprehensive Repair Area (CRA): This area not only focuses on water source and industrial pollution issues but also involves the restoration of multiple ecosystems. Ecological vulnerability arises from various factors, including pollution, ecological degradation, and land use changes, making its restoration goals more comprehensive. In the face of significant ecological vulnerability, a combined strategy of natural recovery and human intervention is required. The intervention measures will focus on addressing current ecological challenges, such as strictly controlling the encroachment of agriculture, industry, and urbanization in the region, and preventing excessive land development. Specific measures include the following: implementing large-scale vegetation restoration projects and constructing ecological protective forests; developing ecological corridors within the region to provide migration and habitat pathways for plants and animals, and promoting gene flow between species; focusing on natural recovery by repairing the intrinsic functions of ecosystems, promoting natural succession, and gradually enhancing the self-regulation and recovery capacity of the ecosystem; establishing ecological protection zones to limit unnecessary development activities, providing space for natural ecosystem recovery.

Ecological Restoration Area (ERA): Ecological reconstruction areas are typically regions that have suffered severe ecological degradation due to factors such as human activities or natural disasters, and require systematic, comprehensive restoration interventions. This process involves a multidisciplinary approach, considering ecology, environmental science, sociology, and economics. Ecological restoration is a complex and long-term process, requiring the development and implementation of a series of strategies such as converting cropland to forest, soil and water conservation, and wetland restoration. The success of restoration efforts depends on fully considering the needs and participation of local communities to ensure that restoration measures are integrated with local livelihoods. By providing technical support, financial assistance, and training, communities can be encouraged to actively engage in ecological restoration projects, fostering the synergistic development of ecological, social, and economic benefits, thereby achieving the region’s sustainable revival.

4.2. Empirical Zoning and Strategies

For different ecological restoration zones, focusing on the issues at hand and considering their needs for development, this study has formulated management and development strategies for each ecological restoration zone, as follows:

Ecological restoration zone:

This zone is primarily located in the core area of the Guanzhong Basin along the Wei River, where transportation networks, urban infrastructure, and urbanization levels are well developed. It is one of the most active regions for human activity. Although some studies [52] suggest that the negative ecological impacts of human activities in the western Baoji and Hanzhong areas have been decreasing, the natural ecological foundation of this zone remains relatively weak. Existing research indicates that rapid urban expansion has intensified human–land conflicts [53]. Industrial pollution and inappropriate water use continue to impose considerable pressure on the already fragile ecosystems in this region.

Management Goal: Rebuild ecological structure and restore ecosystem functioning.

Operational strategies should focus on comprehensive engineering-based and management-oriented ecological restoration measures. Key actions include implementing soil remediation, wetland reconstruction, and river rehabilitation projects to restore degraded ecosystems; relocating or transforming high-pollution industries while promoting the development of clean and low-impact industries; and strictly controlling excessive land development and delimiting urban expansion boundaries to reduce further ecological pressure. In addition, large-scale vegetation restoration and the construction of urban–rural ecological green space systems should be promoted to enhance ecosystem structure and function. Improving agricultural water-use efficiency through the adoption of water-saving irrigation technologies is also essential. Furthermore, urban ecological land management should be strengthened, with targeted remediation of contaminated soils and degraded green spaces to improve overall environmental quality.

Ecological repair zone:

This area is mainly distributed along the northern and southern edges of the Guanzhong Basin, functioning as a transitional zone between the basin and the surrounding mountainous regions. Rapid urbanization and intensive agricultural production have placed pressure on the local ecological foundation, resulting in varying degrees of ecological disturbance. According to previous studies [54], targeted measures are required to alleviate ecological stress and enhance recovery potential.

Management Goal: Reduce ecological pressure and support natural recovery.

Operational strategies should emphasize ecosystem-based and biodiversity-oriented restoration approaches. Key measures include promoting ecological agriculture by reducing the application of chemical fertilizers and pesticides, and strengthening the protection of existing forests and grasslands through strict prevention of deforestation. Riparian buffer zones should be established along rivers to enhance ecological corridor functions and protect aquatic and terrestrial habitats. Enclosure-based forest restoration and small-scale afforestation projects can be implemented to facilitate natural regeneration and improve vegetation structure. In addition, biodiversity conservation policies and habitat protection measures should be strictly enforced. Where appropriate, moderately fragile farmland can be converted to forest or grassland. Finally, ecological patch connectivity should be improved through strategic corridor planning and targeted vegetation restoration, thereby enhancing landscape connectivity and overall ecosystem resilience.

Ecological development zone:

This area has a poor ecological foundation and low ecological production service value, but it has some production and development potential. In response to this, [55] suggests that such regions are suitable for controlled urban development and agricultural activities. Based on protecting the ecological foundation of the area, it is essential to fully utilize the local ecological endowment, vigorously promote ecological agriculture, develop specific agricultural eco-tourism areas in regions with suitable conditions, and develop the ecological tourism economy in areas with historical and cultural value, enhancing the agricultural and tourism-based cultural value of the regional ecosystem. In addition, it is necessary to strictly control the growth of urban boundaries, promote the development of related ecological industries, and ensure the protection of ecological and agricultural land red lines in the area. Development strategies must optimize the planting structure, use agricultural ecological resources rationally and efficiently, strictly control the scale of urban and industrial development, and ensure regional ecological security. For key areas that need restoration, such as water areas, forest land, and wetlands, it is essential to carry out relevant soil and water conservation work according to local conditions, strengthen regional connectivity, actively develop a green economy, and reduce destruction to the area. In regions with suitable conditions, it is vital to increase afforestation efforts, carry out soil restoration work, and establish ecological protection forest belts. Eco-tourism and characteristic ecological forestry oriented towards ecological construction should also be developed [56].

Ecological conservation zone:

This area has a good ecological environment and high ecosystem service value, located in the core of the vast Qinling–Daba Mountain region, and its distribution is roughly the same as the research presented in [57]. It plays an important role as an ecological barrier. The main restoration and management goals for the ecological protection zone are related to natural recovery. Referring to the opinions of [58] and others, some areas with high urban disturbance risks can take artificial disturbance measures. Existing ecosystems with high service value, such as forests, grasslands, and lakes, should be protected to further improve ecological functions. By establishing ecological protection zones, forest land conservation can be reinforced, vegetation cover can be stabilized, and the negative impacts associated with human disturbance can be effectively reduced. It is vital to promote ecological migration projects, implement relocation in areas unsuitable for living and production, and guide the population to move to more suitable surrounding areas for construction.

To examine the validity and practical relevance of our zoning results, we compared them with the ecological conservation scheme established in the Shaanxi Provincial Territorial Spatial Planning (2021–2035) and the Regulations of Shaanxi Province on the Protection of the Ecological Environment of the Qinling Mountains. Overall, our zoning outcomes show strong consistency with the province’s ecological management priorities. The ecological conservation zones identified in this study are mainly located in the core mountainous areas of the Qinling–Daba Mountains, and they broadly overlap with the ecological protection redline delineated in the provincial plan, including the Qinba Mountain region, the Ziwuling–Huanglongshan biodiversity conservation area, and riparian zones within the Weihe River Basin. The provincial plan proposes an ecological security pattern of “one mountain, two rivers, four zones, and six belts,” and our conservation zones align closely with the “Qinba low-mountain and hilly ecological function zone” identified therein. Similarly, the restoration zones in our study are concentrated in the Xi’an metropolitan area and eastern Weinan, which is consistent with the provincial plan’s emphasis on improving urban ecology and controlling the boundary of urban expansion.

However, we also observed some differences that may provide additional insights for planning. First, the provincial plan designates the northern foothills of the Qinling Mountains as the “ecological protection belt of the northern Qinling foothills,” whereas in our analysis, some parts of this area were identified as restoration zones due to relatively high vulnerability scores. This suggests that even within officially designated protection belts, there are localized areas that require more intensive restoration efforts, and that single-indicator or boundary-based approaches may overlook such areas.

The methodological framework proposed in this study is conceptually general and can serve as a reference for other mountainous ecological barrier regions. For example, the Hengduan Mountains in southwestern China—another national-level ecological barrier characterized by high biodiversity value and complex terrain—could benefit from a similar integrated VSD–InVEST approach. Adapting the framework to that region would require incorporating region-specific vulnerability indicators such as permafrost degradation, glacier retreat, and shifts in vertical vegetation belts, as well as calibrating parameters according to local precipitation regimes and vegetation characteristics. Although necessary local adjustments are required, the core logic of the framework—overlaying classified vulnerability and ecosystem service value layers to derive differentiated management zones—has broad applicability in mountainous areas facing the challenge of balancing ecological conservation and socio-economic development.

4.3. Highlights and Limitations