Abstract

Microgrids are evolving from simple hybrid systems into complex, multi-energy platforms with high-dimensional optimization challenges due to technological diversification, sector coupling, and increased data granularity. This review systematically examines the intersection of microgrid optimization and metaheuristic algorithms, focusing on the period from 2015 to 2025. We first trace the technological evolution of microgrids and identify the drivers of increased optimization complexity. We then provide a structured overview of metaheuristic algorithms—including evolutionary, swarm intelligence, physics-based, and human-inspired approaches—and discuss their suitability for high-dimensional search spaces. Through a comparative analysis of case studies, we demonstrate that metaheuristics such as genetic algorithms, particle swarm optimization, and the gray wolf optimizer can reduce the computation time to under 10% of that required by an exhaustive search while effectively handling multimodal, constrained objectives. The review further highlights the growing role of hybrid algorithms and the need to incorporate uncertainty into optimization models. We conclude that future microgrid design will increasingly rely on adaptive and hybrid metaheuristics, supported by standardized benchmark problems, to navigate the growing dimensionality and ensure resilient, cost-effective, and sustainable systems. This work provides a roadmap for researchers and practitioners in selecting and developing optimization frameworks for the next generation of microgrids.

1. Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to review and investigate where and how the topics of microgrids and metaheuristic algorithms intersect. This review is motivated by three key observations. First, the literature on microgrid optimization is vast and rapidly expanding, yet it remains fragmented between engineering case studies and algorithmic developments, with few works synthesizing the broader trend toward metaheuristics. Second, while previous reviews have cataloged optimization tools or algorithms in isolation (e.g., [1,2]), they often lack a forward-looking analysis of how the fundamental characteristics of the optimization problem—specifically its growing dimensionality and data granularity—dictate the necessity of a paradigm shift from classical to metaheuristic methods. Third, the accelerating convergence of sector coupling and digitalization in microgrids creates an urgent need to guide researchers and practitioners in selecting and developing appropriate optimization frameworks. Therefore, this work not only provides a perspective on how microgrids are evolving and how metaheuristic algorithms will increasingly be used but also establishes a structured rationale for why this intersection is critical for the field’s future. Consequently, this review aims to systematize the relationship between microgrid complexity and metaheuristic suitability, guiding the selection and development of optimization algorithms for next-generation energy systems.

This review is based on a comprehensive analysis of the scientific literature, including peer-reviewed journal articles, conference proceedings, and key industry reports published primarily between 2015 and 2025. This decade captures the rise in smart multi-energy microgrids and the corresponding proliferation of metaheuristic applications in energy system optimization. Publications were identified through systematic searches in major databases (e.g., Scopus and Web of Science), using keyword combinations such as ‘microgrid optimization’, ‘metaheuristic algorithms’, ‘hybrid renewable energy systems’, ‘genetic algorithm’, and ‘particle swarm optimization’. The selection prioritized studies that: (1) presented original case studies applying metaheuristics to microgrid sizing or operation; (2) introduced or benchmarked novel or hybrid metaheuristic algorithms in an energy context; or (3) provided critical reviews of trends in microgrid technologies or optimization methodologies. This approach ensures that the review captures both established practices and emerging innovations at the intersection of these fields.

The urgent need to reduce carbon emissions and promote sustainability requires us to rapidly modernize energy supply and use. Accordingly, a major transformation is taking place, with power supply increasingly relying on renewable energy, especially solar and wind [3,4], while electrification is being increasingly prioritized, e.g., with the shift to e-mobility [5], heat pumps [6], power-to-fuel alternatives [7], etc. There is also a growing decentralization in power generation, with many consumers becoming prosumers [8]. This comes also with a growing sector coupling, especially combined heat and power (CHP) [9], and an emerging attention to nexus aspects, specifically water energy and food energy [10]. Furthermore, thanks to the growing digitalization, the energy system is becoming smarter. Such digitalization is based on several pillars: advanced metering [11], the Internet of Things (IoT) [12,13], artificial intelligence [14,15,16], and blockchain [17,18,19].

Studies and roadmaps to achieve a renewables-dominated energy supply have intensified in the last decade [20]. Many of these projections focus on national scenarios, e.g., [21], while some also consider broader geographies, e.g., Europe [22,23]. Thereby, renewable energy targets and alternatives are assessed under the consideration of resource availability, technical feasibility, cost effectiveness, contribution to climate goals, etc. [24]. As an example, Zubi et al. proposed a renewables power mix for Spain that complements PV and wind with dispatchable power plants, specifically hydropower, biomass and CSTP (concentrating solar thermal power), with thermal storage [25,26]. These studies provide support for decision makers to shape renewable energy projections and targets, which have become increasingly ambitious in recent years, as can be observed in the EU Green Deal, among others. Similarly, in a rather bottom-up approach, several cities around the globe have committed to shift their total energy consumption to renewables by 2050, including Frankfurt, Hamburg, Copenhagen, and Vancouver, among others. The Hague has set such a target for 2040, and Malmö and Växjö for 2030. These targets are not less important than the macro approach, as they emphasize the key role that energy democracy can play in enforcing and accelerating a much-needed transition [27].

Distributed power generation, especially rooftop PV, is expected to form a significant component in the transition to a mix based on renewables. Germany was an early adopter of rooftop PV funding schemes, with the 1000 Roofs Program having been introduced in 1990 and accomplished in 1992 with few MWs connected to the grid. Yet, rooftop PV is a paradigm on how a modest start can eventually evolve into a game changer. Today, the global installed rooftop PV capacity exceeds 300 GW, and this is still a small fraction of a global potential of around 20 TW. Joshi et al. calculated that 0.2 million km2 of rooftop area around the globe can be used to install PV systems [28]. Their study provides a quantification of the potential under the consideration of the levelized cost of electricity (LCoE) at a high spatiotemporal resolution. They conclude that 10 PWh of electricity from rooftop PV can be generated annually for costs between 4 and 10 c$/kWh, and an additional 17 PWh for costs between 10 and 28 c$/kWh.

A much smaller role than PV in distributed power generation is played by urban wind turbines, which is basically due to technological and regulatory lag [29]. Exploiting urban wind energy faces the challenges of low wind speed and high turbulence intensity [30]. Urban turbines have also strict noise requirements to avoid affecting the wellbeing of nearby residents [31]; considering aerodynamic and mechanical transmission noise, 40 dB should not be exceeded [32]. Yet, this domain has advanced notably in recent years and is expected to play a bigger role in the future [33].

The growing reliance on variable renewable energy, especially PV and wind power, comes together with a growing population of batteries in the power system [34]. These can have a variety of roles, including variable renewable energy balancing, peak-load shifting, supply of ancillary services, etc. A wide range of battery chemistries are being implemented in power systems, including lead–acid, lithium-ion, sodium–sulfur, flow batteries, etc., while the R&D in new chemistries is intensifying [35]. Other energy storage technologies, such as fly wheels [36] and supercapacitors [37], are also emerging, among others, within the context of high-power-density applications, such as fast electric vehicle (EV) charging. While power system batteries will be mostly stationary, by 2035 there will also be a big number of EVs in circulation with a global battery capacity averaging roughly 5 kWh per capita. Tapping this huge power storage potential of EVs for the benefit of the power system comes with major challenges due to the fragmented capacity and mobility [38]. Several EV smart charging schemes are currently under demonstration: unidirectional smart charging (V1G) [39], vehicle-to-grid (V2G) [40], vehicle-to-home (V2H) [41], etc. These ongoing developments increasingly couple the power supply and mobility, creating new requirements for the electricity grid while also providing new opportunities in power system optimization.

A growing sector trend is currently taking place, in which heat and electricity are coupled. This comes within the context of maximizing efficiency but also exploiting renewable energy resources. In particular, HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning) demands are increasingly being covered with heat pumps, due to their outstanding efficiency advantage in low-temperature applications. Thereby, local generators such as PV or wind can provide the needed electricity, while the pumped heat can originate from the air [42], or from shallow geothermal resources [43]. While there is already a long tradition of using solar thermal collectors for heat supply, mostly in the form of hot water for showering and space heating, photovoltaic thermal hybrid solar collectors (PVT) have been gaining more attention in recent years [44]. Cogeneration systems using biomass are also finding broader use. While biomass can be exploited directly for heat supply, its added value is higher when used in a CHP approach, e.g., with electricity sold to the grid and residual heat to a district heating network. Coupling heat and electricity supply also opens new opportunities in the form of power-to-heat solutions to facilitate PV and wind power integration [45,46].

The intensifying distributed power generation comes together with the emergence of prosumer platforms, such as microgrids and virtual power plants. Microgrids are hybrid energy systems that exploit local energy resources (PV, wind, small hydro, etc.) to satisfy the local demand autonomously [47]. Microgrids have become a key technology in rural electrification in developing regions while gaining momentum in conventional power systems. Grid-connected microgrids can facilitate the local reliance on low-carbon energy technologies while creating investment opportunities at community level and reducing electricity costs. This comes with enhanced supply reliability, as the local consumers depend primarily on the microgrid while having also the backup of the main grid [48].

Significant power sector upgrades are also currently taking place through digitalization [49]. This allows us to collect and process data with high time and space granularity and use it for power system monitoring and operation [50,51]. Digitalization is finding its way to prosumer platforms as well and will change how such systems are engineered, operated, maintained, analyzed, and upgraded. For instance, conventional microgrids are initially designed for a lifetime and changes are performed when such a need emerges (e.g., shortage of supply, reliability problems, etc.). Yet, digitalization allows us to monitor the energy flow in such a system, the reliability of its single components, the consumer behavior and habits, the effect of weather events, etc., to eventually optimize operation and continuously perform small upgrades. This allows us to maximize the reliability of a microgrid while minimizing the cost of energy. Digitalization also opens new opportunities in demand-side management (DSM) [52,53] and peer-to-peer (P2P) trading [54,55,56]. As an example, Zubi et al. proposed the use of distributed PV systems for P2P EV charging on a blockchain-enabled platform [57]. With this said, digitalization also comes with a computational cost: an aspect that must be properly evaluated in terms of hardware and software to eventually manage such systems at a workable pace and within a reasonable cost.

Importantly, general trends in the main grid—most notably, sector coupling and digitalization—also propagate to smaller prosumer platforms. Consequently, microgrids are evolving into more complex smart multi-energy systems that supply not only electricity but also heat and e-mobility energy. As a result, this work argues that the future of microgrid optimization is inherently tied to metaheuristic algorithms, which are uniquely suited to solving the emerging high-dimensional problems by using high-granularity data within a reasonable computational time. While this shift enhances the added value and performance of microgrids, it also introduces new technological challenges that must be understood and addressed. By bridging the fields of microgrid engineering and optimization algorithms, this review sheds light on these challenges and charts a path forward.

Some works in this field attempt to define a single “best” optimization approach for microgrids (e.g., [1]). While such studies offer valuable insights, they often impose rigid boundaries on how a microgrid is defined and, consequently, on the optimization problem itself. In contrast, this work views microgrids as an evolving domain, where technological diversification and sector coupling continuously reshape the optimization landscape. From an algorithmic perspective, what matters then are the problem’s fundamental characteristics: its dimensionality, the granularity of the search space, the noise level of the objective function, and whether it is single- or multi-objective. It is the simultaneous consideration of these aspects—rather than a search for the universally best algorithm—that leads to a proper understanding of the optimization task and the suitability of the available tools. Accordingly, the focus of this review is to examine how the potential of metaheuristic algorithms can be harnessed to address the evolving challenges of microgrid optimization, particularly in the context of increasing dimensionality and data granularity.

Beyond technological and digital drivers, the evolution of microgrids is increasingly shaped by a dynamic regulatory landscape. Growing policy mandates for decarbonization, energy security, and grid resilience are accelerating the deployment of multi-energy and smart microgrids. Future regulatory frameworks are expected to address critical aspects such as interoperability standards, grid-connection codes for bidirectional power flow, market mechanisms for P2P trading and ancillary services, and safety protocols for emerging storage technologies and V2G integration. While a detailed analysis of regulatory policies is beyond the scope of this work—which focuses on the algorithmic optimization challenges arising from technological complexity—it is acknowledged that these regulatory developments will define the operational boundaries and economic viability within which the optimized microgrid systems of the future will function.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 examines the evolution of microgrids from simple hybrid systems to smart multi-energy platforms, highlighting technological drivers—such as sector coupling, diverse storage, and digitalization—that increase optimization dimensionality and data granularity. Section 3 provides a systematic overview of metaheuristic algorithms, categorizing them by inspiration (evolutionary, swarm intelligence, physics-based, and human-inspired) and discussing their exploration–exploitation balance, which is crucial for a high-dimensional search. Section 4 synthesizes the intersection of these two fields, reviewing case studies where metaheuristics have been applied to microgrid sizing and presenting a comparative analysis of algorithmic performance. Finally, Section 5 concludes by identifying key trends, underscoring the necessity of metaheuristics for future microgrids, and proposing directions for future research—most notably, the development of standardized high-dimensional benchmark problems. Following this structure, the review moves from the problem context (microgrid complexity) to the solution landscape (metaheuristics) and finally to their integrated application, providing a clear roadmap for researchers and practitioners.

2. Microgrids

An important development in the energy sector is the cost evolution of knowledge-based technologies, i.e., renewables, versus resource-based technologies, i.e., fossil fuels. While the first is characterized by a positive learning rate with substantial cost reductions over time, the second is characterized by an unavoidable scarcity and general upward cost trend that comes together with energy insecurity and a major environmental impact. PV has become a paradigm of such a contrast, especially when it comes to the learning rate [58]. The favorable development of renewables creates valuable opportunities for climate action [59], energy security [60], energy poverty mitigation [61], energy justice [62], environmental justice [63], energy democracy [64], etc. Microgrids, which are often referred to as hybrid renewable energy systems, exploit these advantages to provide dependable power supply solutions directly where the energy is needed.

In a broad definition, a microgrid can be characterized as a cluster of interconnected power generators and loads with its own power system boundaries that act as a single entity. Such a system can be off-grid or grid-connected. Even if it is grid-connected, a microgrid must have the ability to fully operate in island mode [48]. Modern power systems must bring multiple quality criteria that have become fundamental for the power consumer, including tight margins for nominal values (voltage and frequency) and power availability on demand (including peak demand), while power outages should be rare, and restoration should be fast. The expectations on a microgrid in this regard are not different.

The current centralized grid in developed countries has its seeds in relatively small city level grids that eventually underwent interconnection and centralization driven by the growing energy demand and the related potential to exploit the economies of scale, as well as the need to untap large hydropower resources. These early power systems from the late 19th century are practically microgrids. In the last few decades, microgrids made a comeback: this time in association with renewable energy. Modern microgrids have their roots in the 1990s, when financial support programs for rooftop PV took off in Germany, Japan, and California, initiating and accelerating with that of the distributed PV market. This trend was later followed in many other countries. Initially, due to their minor role, it was tolerated that such systems feed variable, non-dispatchable power into the grid, independently of the local demand. Nevertheless, it soon became clear that a major transition was happening, with more power consumers becoming prosumers [65]. In the late 1990s, researchers began exploring how to confront this growing prosumer role and plan and manage distributed energy resources in an integrative way that exploits the local energy potentials for reliability, resilience, and profitability [66]. This led to an architecture that matches demand and generation locally in a subsection of the grid, allowing for energy autonomy [67]. This development eventually led to the grid-connected microgrid of today, which was soon exploited as a key technology for rural electrification in developing countries as well.

The optimal sizing of a microgrid is fundamental to assure a reliable power supply at a reasonable cost [68]. The bibliometric analysis on microgrid optimization performed by Arar Tahir et al. shows that this topic has increasingly gained relevance in recent years [69]. The optimal sizing of a microgrid is based on the simulation of its operation to eventually calculate its key performance metrics, such as LCoE, loss of power supply probability (LPSP), carbon footprint, etc. [70]. The LCoE is calculated over the project’s lifetime, while the operational performance is simulated typically on an hourly basis over one year to capture the renewable variability and demand patterns. This process is repeated for different microgrid configurations and sizes of components to eventually settle on the best obtained solution. All candidate solutions must be simulated in line with the microgrid energy management strategy in accordance with real-life operation. For instance, in a PV–wind–battery–diesel microgrid, in each simulation step, the electricity demand is compared with the combined power generation from the PV and wind to determine the net energy. In the case of surplus, the battery is charged to the maximum and beyond that, the excess energy is curtailed. On the other hand, if the net energy is negative, then the battery is used to cover the gap. Should the battery reach the minimum state of charge, then the diesel generator is used to cover the gap and recharge the battery. An overview of energy management in microgrids is available in the references [71,72,73,74], among others.

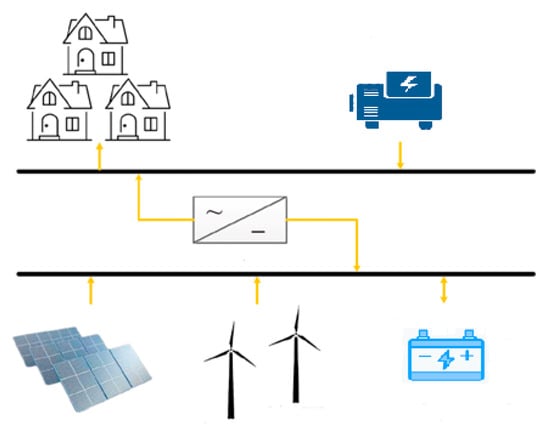

While the broad definition of microgrids as a local power system with their own boundaries indicates wide technological diversity, it must be highlighted that not all microgrid configurations receive equal attention [75]. The PV–wind–battery–diesel configuration illustrated in Figure 1 is currently the dominant one at deployment level. PV or wind or both combined are used as the renewable energy source. As these are variable resources, energy storage, mostly lead–acid or lithium-ion batteries, are common components in current microgrids. Furthermore, many existing microgrids include a diesel generator for backup. Some studies optimize microgrids under the consideration of DSM potentials. This can include flexible electric demand, e.g., for water pumping [76], power-to-heat options [77], hydrogen production via electrolysis [78], etc.

Figure 1.

PV–wind–battery–diesel microgrid.

From an optimization perspective, the classical microgrid presented in Figure 1 represents a relatively low-dimensional optimization problem. It typically requires sizing four to five main variables: the PV generator capacity, the number and type of wind turbines, the battery bank chemistry and capacity, and the rating of the diesel backup generator. If demand-side management is considered, a discrete set of alternative demand profiles may be added. This results in a search space that can often be explored exhaustively. In contrast, the evolution toward smart multi-energy systems drastically increases the dimensionality of the problem. The optimization variable set expands to include the following, for example: the choice and size of multiple storage technologies (e.g., Li-ion battery, supercapacitor bank, flywheel), the capacity of thermal components (solar thermal collectors, PVT, heat pumps, thermal storage), the integration of EV charging infrastructure with V1G/V2G capabilities, and the parameters for real-time digital control strategies. This shift from a handful to many interdependent decision variables transforms the optimization from a low-dimensional task that is solvable by an exhaustive search (ES) into a high-dimensional one, where the combinatorial explosion of possible configurations makes an ES computationally intractable.

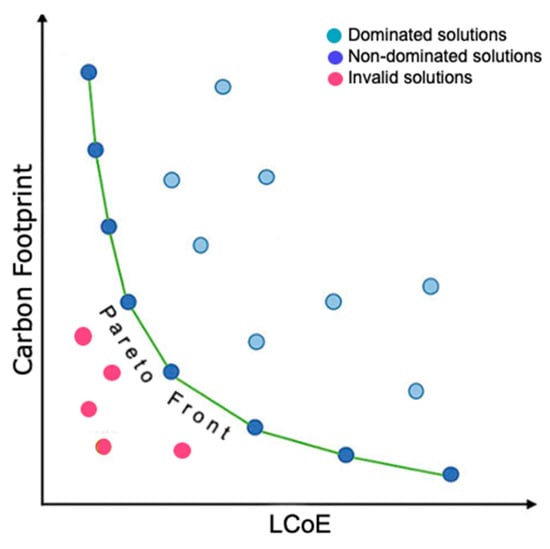

The optimization of the microgrid in Figure 1 could be of a single objective, e.g., minimal LCoE, or a multi-objective, e.g., a compromise between low LCoE and a small carbon footprint. A widely used method for multi-objective optimization is the Pareto Front, as illustrated in Figure 2. In a Pareto Front, each candidate solution has an LCoE and a carbon footprint. Some solutions result as dominated, meaning that there is at least one other solution with both lower LCoE and a smaller carbon footprint. A dominated solution is in the shadow of another and hence is classified as irrelevant. On the other hand, when comparing two not dominated solutions, then one is better in terms of LCoE and the other is better in terms of carbon footprint. As illustrated in Figure 2, the Pareto Front is a line of not dominated solutions. All these solutions are valid in principle. Settling on one solution can be performed by weighing the objectives. For instance, the carbon footprint can be represented in a carbon cost and merged into the LCoE. Furthermore, the optimization is performed with constraints, e.g., for a solution to be valid, it must comply with an LPSP threshold (e.g., < 1%) or otherwise be discarded. Further discussion on multi-objective optimization in microgrids is provided in the references [79,80,81,82,83], among others.

Figure 2.

Two-objective optimization using Pareto Front.

Significant efforts have been dedicated to the development of standard microgrid optimization tools such as HOMER, iHOGA, and HYBRID2, among others [2], and their use in case studies. These tools have a set environment and can only be used within certain boundaries. Hence, some modelers prefer to rely on their own programing. Within this aspect, platforms such as MATLAB or GAMS are often used. Furthermore, some modelers opt for coding with Python, C++, Java, etc. Programming provides more freedom in exploring optimization algorithms.

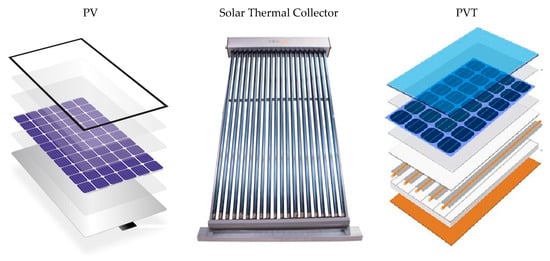

The future challenge in microgrid optimization will be its growing complexity, which comes in the form of the growing number of components in such a system and their technological diversity. While conventional PV panels have been the standard in microgrids, sector coupling will increasingly include solar heat as part of the microgrid boundaries. This is performed in the form of using PV panels and solar thermal collectors as separate components, or by opting for PVT. The three solar collector options are illustrated in Figure 3. Such microgrids can be connected to both the power grid and a district heating network [44].

Figure 3.

Solar collectors for power and heat generation.

New concepts for urban wind turbines are emerging, including those by Flower Turbines, IBIS Power, O-Innovations, and Aeromine Technologies, as illustrated in Figure 4. For instance, Flower Turbines is commercializing vertical-axis rooftop wind turbines that are one to few meters high with a tulip-like shape. The turbine starts generating power at a wind speed of just 0.7 m/s. Urban wind turbines do not necessarily compete with PV panels for roof space [84]. For instance, a layout that accommodates both is the POWERNest by IBIS Power, where vertical turbines are placed underneath solar panels, allowing for maximum power generation per m2. As the technologies mature and incentives are provided, urban wind turbines will become increasingly common in microgrids, thereby enhancing technological diversity, but also imposing new challenges upon system optimization.

Figure 4.

Emerging technologies in urban wind turbines.

Electricity storage is one of the aspects that will also become more complex as energy and power requirements in microgrids become more demanding, especially with the growing role of e-mobility, including the need for fast charging and the opportunities and challenges that V1G and V2G bring [85]. An overview on energy storage systems is provided by Ahmed et al. [86], among others. Table 1 summarizes the power storge technologies that are most relevant within the present and future microgrid context.

Table 1.

Summary of power storage technologies that are relevant within the microgrid context.

Lead–acid batteries have long been the dominant technology in microgrids, basically due to their technological maturity, abundant commercial offer, and low cost. They are used in microgrids as stationary battery-banks to store variable renewable energy and dispatch it as needed. Yet, in the current state of the art, lithium-ion (Li-ion) batteries are crystalizing as the dominant technology with the highest market share in new capacities. Currently, Li-ion batteries are being used as stationary systems, while their V1G and V2G potential remain relatively untapped. This aspect, however, is likely to change in the future with the growing digitalization of the power system. The use of V1G in a microgrid has been explored, among others, by Elkadeem et al. [102], while V2G has been the subject of the case study by Nadimuthu et al. [103]. Furthermore, as Li-ion batteries have a much longer cycle life, second-hand batteries can be used in power systems after a first life in EVs [104,105]. Such second-life batteries could, among others, be engineered to EV charging points, including fast charging. Should the Li-ion battery market continue to grow at the current pace without putting effective collection and recycling schemes in place, then lithium will become a critical material. This has increased interest in sodium-ion (Na-ion) batteries. Na-ion batteries are emerging as a competitor due to their better circular economy and low-cost perspectives [106]. They are currently finding an initial use in EVs, mainly in entry-level cars with a relatively small battery pack (e.g., the Yiwei EV, a brand under China’s JAC backed by VW Group).

Furthermore, supercapacitors are an emerging technology that is finding its way to microgrids. For instance, Caparrós-Mancera et al. conducted an experimental analysis on the influence of a supercapacitor bank on a microgrid [107]. The study contrasts operation with a conventional energy storage system using lead–acid or Li-ion batteries. The hybrid system outperformed the conventional one by far, demonstrating a smooth dynamic response, longer battery life, and operational protection of equipment that is sensitive to peak currents. Also, Babaei et al. conducted a study on optimizing hybrid energy storage in a microgrid that includes a Li-ion or lead–acid battery in combination with a supercapacitor bank [108]. The optimization allows us to maximize the supercapacitor utilization to prolong battery life. Alharbi et al. combine a Li-ion battery and a supercapacitor bank in a solar microgrid with PEM (proton exchange membrane) fuel cell backup to effectively manage the fast response to variations without affecting battery life [109].

Flywheel energy storage systems (FESS) have been gaining traction in recent years. This is an outstanding technology for short-term charge and discharge cycles. Under such conditions, it provides advantages in fast response, high roundtrip efficiency, durability and good performance, both in terms of energy storage and providing ancillary services [110]. Hence, FESS are well-suited to store variable renewable energy, especially within the context of microgrids [111]. Furthermore, such a system can provide solutions for fast EV charging [112]. EV charging points using FESS are marketed by Levistor and Zooz, among others. Flywheels make good partners in hybrid power storage systems, especially in combination with batteries, where they can absorb fluctuations and cover many ancillary services, thereby extending battery life and improving system performance while reducing the LCoE [113,114].

The expanding portfolio of energy storage technologies, summarized in Table 1, is a primary driver of increased optimization dimensionality in modern microgrids. Unlike a classical system with a single battery type, a designer must now choose between chemistries (e.g., Li-ion vs. Na-ion) and then between complementary technologies (e.g., pairing batteries with supercapacitors or flywheels). Each technology introduces distinct decision variables: not only capacity (kWh) but also power rating (kW), chemistry-specific degradation models, cost trajectories, and operational constraints (e.g., cycle life, response time). This multi-technology, multi-parameter selection problem transforms storage sizing from a single-variable task into a high-dimensional combinatorial one. Consequently, the search space for an optimal hybrid storage system grows exponentially, making ES impractical and elevating the importance of metaheuristics that can navigate such complex, discrete, and constrained design spaces.

Sector coupling in microgrids opens an opportunity for power-to-heat solutions [115]. For instance, a study by Maranda et al. elaborates on converting excess PV energy in a microgrid into domestic hot water [116], while Häring et al. focus on the demand for space heating [117]. On the other hand, Rosales-Asensio et al. explore the polygeneration potential (power, heating, and cooling) of a microgrid within the context of a resilient building design (e.g., for a hospital) [118]. Polygeneration microgrids have also been explored by Wang et al. with the inclusion of a micro-gas turbine for combined heat and power generation [119]. With the growing attention to sector coupling, the term multi-energy microgrid has become common in the literature and has been discussed, among others, by Sasidhar et al. [120] and Horrillo-Quintero et al. [121].

Heat pumps have a major efficiency advantage in multi-energy microgrids, especially for low temperature demands of roughly up to 120 °C [42]. This is more than enough for residential demands and is also high enough for some industries such as the food industry, where there is high demand for hot water and low-temperature steam. Heat pumps can be complemented with thermal storage and hence become a key component in DSM, which is valuable in power systems based on variable renewable energy, especially microgrids. Accordingly, solar and wind peaks can be converted into heat and stored as is convenient. The same principle applies to heat pumps connected to a district heating network [44]. Hence, heat pumps provide new opportunities to boost efficiency and economize the energy supply but also add complexity to a microgrid to be optimized under sector coupling. Such optimization requires us to opt for the heat source while calculating the heat pump’s nominal power and the thermal storage capacity [122]. Air-source or geothermal heat pumps can be used in such systems. Geothermal heat pumps are more costly to install but have the advantage of the constant temperature of the shallow earth.

A diesel generator has so far been a common component in microgrids, especially when it comes to off-grid systems. For instance, Dufo-Lopez et al. performed a case study for Zaragoza and Jaca in Spain where a PV-wind-battery microgrid with and without a diesel generator are contrasted [123]. Thereby, the authors concluded that the diesel generator improves profitability and system reliability, and even reduces the carbon footprint on a life cycle basis, as it allows us to reduce the size of the other microgrid components. Hence, due to its low fraction in the overall energy supply, the use of diesel in microgrids has not been considered as a “spoiler” of a renewable energy system so far. This said, there are also many studies that propose implementing the biodiesel of biogas as a backup fuel in microgrids, e.g., [124,125], to maximize the environmental benefits of such systems. Biofuels are produced from feedstocks such as vegetable oils, tallow, sugar crops, starch crops, agricultural residues, forestry residues, municipal solid waste, etc. Depending on the specific feedstock, different processes are used. For instance, sugar and starch crops are processed into ethanol via fermentation, while forestry residues and solid municipal waste are gasified to syngas using the Fischer–Tropsch pathway. Extensive details on this topic are available in the reference [126]. Such solutions enhance the role of microgrids as a key component within a circular economy. As an example, municipal solid waste could be processed to the backup fuel needed in microgrids in a win–win approach.

A microgrid is optimized and engineered using initial inputs regarding the expected demand profile, solar and wind data, cost of components, expected performance, etc. In traditional microgrids, this is followed by relatively shallow monitoring and limited intervention. This notion, however, is increasingly challenged by a growing digitalization, which is finding its way to microgrids as well. Accordingly, the term smart microgrids has become common in the literature in recent years, with authors focusing on several key digitalization aspects, including digital twins [127,128], wireless communication [129], IoT [130], edge and cloud computing [131], blockchain-enabled P2P power transaction [132,133], etc. For instance, Kabalci et al. propose a smart metering system to monitor the power flow in a microgrid and transmit the collected data via wireless communication [134], while Silva et al. developed an IoT-based energy management system for the monitoring and operation of a microgrid with a web-based graphical user interface [135]. Hence, a state-of-the-art microgrid accumulates real-time data on the hourly demand, solar and wind power generation, performance of components, etc., and can recalculate the system using these new inputs and eventually suggest upgrades. Such an online cloud-based platform has been set, among others, by the company Brightmerge. This approach results in improved system reliability but comes together with intensive data collection and a higher computational cost, which can then be reduced by using metaheuristic algorithms. Hence, as is the case of sector coupling, digitalization will also require the use of metaheuristics in microgrid optimization. The difference is that sector coupling does so by shifting the optimization problem from a low-dimensional to a high-dimensional one, while digitalization increases the granularity of the used data and the calculation frequency.

3. Metaheuristic Algorithms

Optimization refers to finding the input parameters of a function that result in its minimum (e.g., cost) or maximum (e.g., profit). There is a wide diversity of optimization algorithms, including classical algorithms, which have been predominantly suggested in the theory of math before the invention of the microprocessor. Classical algorithms use the gradients of a continuous function to find its optimum. Hence, they are implemented when dealing with differentiable functions. Yet, real-world problems typically include variables with discrete values, resulting in a non-differentiable objective function. Some works in the field of optimization stick to classical algorithms by linearizing such problems. The effectiveness of this approach depends on the specific problem: most importantly, how many discrete variables are there and how noisy the objective function is.

Often, optimization cannot be performed by using derivates, and for that there is a wide range of alternatives [136]. These assume little to nothing about the objective function and hence are often referred to as black-box optimization algorithms. When navigating a search space, the more potential solutions are explored, the higher the probability for a better result. An optimization, however, should be limited to realistic computational cost boundaries. Hence, the question becomes which search approach can bring the best result within such boundaries. This is a key question in the field of optimization, which has led to the development of a wide range of strategic methodologies that allow us to guide and narrow the search towards high quality solutions.

A widely used optimization approach is ES. This requires that all variables are represented in discrete values and all possible combinations are calculated. This is a deterministic approach that leads to the global optimum. ES is often referred to as a brute-force search, as it lacks strategy and hence most of the computational cost is spent evaluating low quality solutions. A chronic problem of an ES is the so-called combinatorial explosion, which is also referred to as the curse of dimensionality. When facing high-dimensional problems with high granularity, the computational cost of an ES becomes prohibitive. This is especially true as many real-world problems require a timely solution and hence cannot realistically be solved with ES. A good example of this are stock trading tools, where satisfactory advice within a short period of time is useful, while the ideal one after prolonged waiting is not so anymore. Hence, ES is used when the problem to solve can be limited to a manageable search space. When this is the case, ES is often preferred, as it guarantees finding the global optimum. For this reason, it is also often used as a baseline method to benchmark other algorithms.

The setbacks of brute-force search are tackled, among others, in the dividing rectangles algorithm (DIRECT), also referred to as “pattern search”, as the search space is split into regions that are equivalent to dividing a field into small geometric shapes. The initial scanning of the search space identifies the regions that are more promising as potential hosts of the optimum. The more promising a region, the more refined the search within its boundaries, i.e., the more it is subdivided and explored. Although the DIRECT algorithm is deterministic, there is no guarantee that the optimum will be localized, as the search can be guided into the wrong region and eventually become trapped in a local minimum. DIRECT algorithms have proven efficient in problems with up to six variables, while their performance becomes worse when confronting high-dimensional problems [137]. Hence, they have widely been used in low-dimensional problems, including in energy systems modeling [138,139]. The limitations of DIRECT search are very much related to the lack of randomness in its search strategy, which limits its ability to agnostically explore the search space, making it susceptible to deceptive local optima. This is especially true for noisy objective functions. Further information on the DIRECT algorithm is available in the references [140,141,142].

Algorithms that use a random search have good exploration qualities but are non-deterministic. Yet, a random search can help find a good solution to the objective function in a fraction of the time of an ES [143]. Within this context, Monte Carlo methods have widely been used to solve complex optimization problems. In such methods, the search space is explored through random sampling. While performing the search, each time the algorithm finds a better solution, it adopts it as the current optimum and continues the sampling. Thereby, the algorithm monitors the pace of improvement. At the initial stage of the calculation, the algorithm will update the optimum relatively frequently and thereby register significant improvements, but later, the improvements become more rare and less significant, which implies that a good enough solution has been found. Random search is purely exploratory, i.e., uncoordinated, and hence it does not become guided by localized high-quality solutions for good (helping find a way to the global optimum) or for bad (misguiding the search to a local optimum).

While Monte Carlo methods stand out for their exploration approach, the DIRECT algorithm is very much focused on exploitation. “Exploration” and “Exploitation” are key terms in the navigation of a search space. Exploration is a diversification of the search through randomness, while exploitation implies an intensification of the search in certain regions, typically around identified high-quality solutions. A good compromise between exploration and exploitation is achieved in population algorithms, which are often used for challenging objective functions that are high-dimensional and noisy. Such an algorithm seeds a population of agents that move in the search space, relying on rules that bring together coordination and randomness, i.e., where identified good solutions provide a hint on where/how to further explore the search space. This implies using the experience gained in the search process to iterate a strategic approach. Hence, while randomness remains a key element in the search, bias decisions make it more efficient. Thereby, the population concept adds robustness to the search, increasing the likelihood of overcoming local optima and converging with the best solution. Population algorithms are classified into four groups depending on whether they are inspired by evolution, swarm intelligence, the laws of physics, or human behavior. As they are non-deterministic, they are often referred to as metaheuristic algorithms.

Evolutionary algorithms mimic the behavior of natural evolution. Such algorithms exploit the fact that certain candidate solutions can lead to better ones if these are combined, and the fittest outcomes are selected. This leads over iterations of higher-quality solutions, and eventually to an optimum. Evolutionary algorithms include genetic algorithms (GA) [144,145,146], evolutionary programming [147,148], differential evolution [149,150], and evolution strategy [151,152]. GA are among the early optimization methods in computer science and are the most used evolutionary algorithms. In the process of evolution, individuals that are fit survive to pass their genes to the next generation. The recombination of genes within a population results in a new generation. Some of the new individuals are fitter than their parents, and hence are favored in the natural selection process. Over generations, this repeated recombination and natural selection results in the improvement of the average fitness of the population. Additionally, occasional DNA replication errors result in mutations, which are equivalent to a random change in a gene. If such mutation improves fitness, then it prevails and spreads within the evolution process.

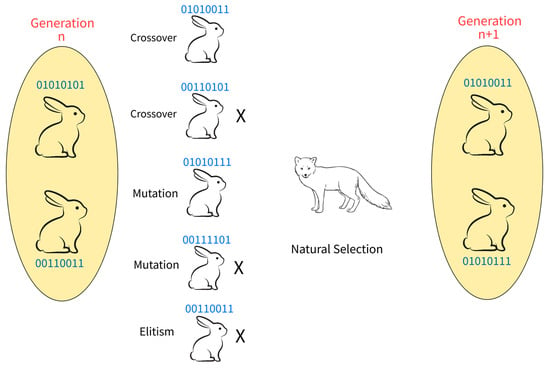

The natural process of evolution has inspired the idea of GA. A GA generates higher-quality solutions from a population of candidate solutions (individuals) through crossover, mutation, and selection, and iterates this process until a satisfactory fitness level or a determined number of iterations is reached. As an example, assuming an objective function with four variables, A-B-C-D, and two good candidate solutions, A1-B1-C1-D1 and A2-B2-C2-D2, then the offspring of these parents could be A1-B1-C2-D2 and A2-B2-C1-D1. In this way, a new generation of solutions can be produced, and the better of these can be selected through a fitness function to eventually be used in the next iteration. New solutions are also produced through a random change in a variable and only the mutations that lead to better solutions are considered further in the iteration. All individuals in the iteration must undergo evaluation by the fitness function, which is typically the value of the objective function in the optimization problem being solved.

The initial population in a GA optimization can be in the hundreds, or even thousands, depending on the objective function. The individuals are often selected randomly to cover the search space properly and assure genetic diversity, but it is also possible to perform such seeding in a biased way, favoring areas where optimal solutions are likely to be found [153]. As inspired by nature, reproduction in GA is traditionally performed with couples of solutions, yet some research suggests that more than two parents can generate higher-quality solutions [154,155]. Furthermore, some variants of GA allow the best individuals in a generation to pass on to the next generation in a process called elitism to prevent the loss of high-quality solutions in the evolution process. Figure 5 provides an illustrative example of the evolution of candidate solutions in GA.

Figure 5.

Evolution of candidate solutions in GA.

Key parameters in the implementation of GA are the probabilities of crossover and mutation. These have a high impact on the convergence speed and quality of the solution. While the crossovers exploit the pool of genes in the population to converge, mutations explore other options by randomly introducing genes that are outside of the population. Hence, a proper fine-tuning of the probabilities of crossover and mutation allows for a proper exploration of the search space to eventually converge in a high-quality solution. To optimize this process, adaptive genetic algorithms have been developed. These monitor the average fitness improvement from generation to generation and accordingly adapt the probabilities of crossover and mutation.

Another important category of metaheuristic algorithms is those inspired by swarm intelligence. There is plenty to learn from the social behavior of animals in swarms, i.e., herds, flocks, schools, colonies, etc. In a swarm, the individuals share information and act in a group to achieve a common target. Understanding how ants find shortcuts to food, bees forage and collect nectar, a wolf pack chases its prey, birds migrate, fireflies mate, penguins survive together in the harsh winter, etc., has helped scientists to develop new optimization algorithms that can solve complex problems with a reasonable computational cost. As nature is rich in such lessons, it is no wonder that the largest variety of metaheuristics is found in swarm intelligence algorithms. In general, such algorithms use good candidate solutions as reference points to navigate the search space. The resulting bias exploration allows us to find better solutions and update the reference points until additional improvements seem impossible and a consensus on the optimum is reached.

A well-established and widely used swarm intelligence algorithm is particle swarm optimization (PSO), which was first introduced in 1995 by Kennedy and Eberhart [156] and improved a few years later [157,158]. The algorithm was initially intended for simulating social behavior, but then turned out to be a good tool for solving optimization problems. Several variants of PSO have been proposed since its introduction, e.g., by He and Wang [159] and Roy et al. [160]. An extensive review on PSO is available in [161].

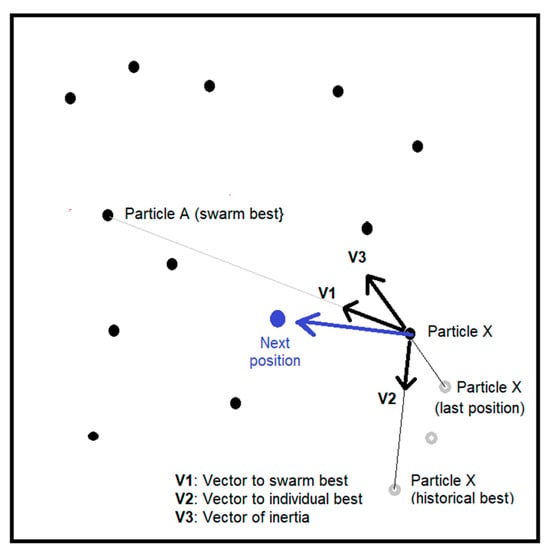

The PSO algorithm localizes an optimum by iteratively exploring the search space and exploiting good candidate solutions in a swarm typology, referred to as particles. The movement of particles in such a simulation mimics swarm behavior in nature, such as bird flocking or fish schooling. The iteration process in PSO is illustrated in Figure 6. When a particle moves in the search space, it does so with a victor that integrates three orientation components. The first component is the position of the collective best, which is the minimum recorded by the entire swarm so far. The second is the position of the personal best of the particle, i.e., the minimal point that the particle has visited in its journey so far. The third is the particle’s inertia, which is the continuity from the last to the current position. In other words, the particle makes one step towards the collective best, one step towards the personal best, and one step in line with its last direction, and with that it reaches its new position. The size of each of these steps is subject to a random function within a defined range. This implies that the next position of a particle in the search space is stochastic within certain boundaries, which compromises exploration and exploitation. This process is conducted by all particles and repeated with each iteration. At the end of each iteration, the personal best of each particle and the collective best are updated to set the basis for the next iteration. This process is repeated until the particles converge in the best recorded solution. Once a particle falls in the best solution, it cannot leave it, because at this iteration stage, its personal best and the collective best become the same point. With this said, as long as not all particles have converged in one point, the exploration process continues, as any free particle can still report a new optimum, updating to the collective best.

Figure 6.

Illustration of the PSO iteration process.

A challenge in implementing PSO is to find the right equilibrium between exploration and exploitation to avoid premature convergence in a local minimum while maintaining a reasonable computational effort. The key parameters are the number of particles seeded in the search space and their velocity, i.e., the maximum distance they are set to move in one iteration. To optimize this aspect, self-tuning algorithms have been developed, which dynamically adjust the simulation parameters and hence maximize the performance of the algorithm [162]. Some authors have also suggested parallelization, i.e., a partitioning of the search space in multiple regions and assigning each region to a separate swarm [163].

Another swarm intelligence algorithm that has gained relevance in recent years is the gray wolf optimizer (GWO), suggested by Mirjalili et al. in 2014 [164]. The algorithm mimics the social hierarchy and hunting behavior of gray wolves. The pack is led by the alpha wolf, which is not necessarily the strongest, but is the best in terms of managing the pack. The second level in the hierarchy are the beta wolves, which follow the alpha while also commanding the lower hierarchy wolves. The deltas are the next in the hierarchy and finally, there are the omegas. In addition to the social hierarchy, group hunting is remarkable in gray wolves. In the first stage the wolfs track, chase and approach the prey. In the second stage, they encircle and harass the prey. Finally, the wolves attack the prey.

In the GWO, the search starts with agents, equivalent to wolves, dispersed over the search space. The position of each wolf is a candidate solution. The algorithm calculates the fitness of each solution and ranks the best three as alpha, beta, and delta, while all other solutions are omegas. The omega wolves assume that the prey, i.e., the optimum, is in the proximity of alpha, beta, and delta, i.e., somewhere in between these three points. Accordingly, each omega takes the positions of the three wolves as reference points. Hence, the movement of an omega is composed of three vectors, one in the direction of the alpha, one in the direction of the beta, and one in the direction of the delta. The magnitude of each vector is subject to a random function but cannot exceed a set maximum. In this way, it is assured that the movement of the omegas is stochastic within a certain orientation towards the leading wolves. This assures a balance between exploration and exploitation. After each iteration, the positions of all omegas are updated, the fitness of each position is calculated, and the best three solutions among all wolves are ranked. The process repeats, and after a certain number of iterations, the governing alpha is considered the optimum.

A list of common swarm intelligence algorithms is provided in Table 2, with a briefing on their inspiration and analogy. Further details on swarm intelligence algorithms can be found, among others, in the reference [165].

Table 2.

Metaheuristic algorithm based on swarm intelligence.

Population algorithms also include algorithms inspired by the laws of physics, which define the relation between candidate solutions based on the controlling rules of physical methods. Thereby, one of the most used algorithms is simulated annealing [196], which mimics the crystal growth behavior in metals through a controlled heating and subsequent cooling process. Other examples include gravitational search [197], artificial electric field [198], ray optimization [199], equilibrium optimizer [200], Henry gas solubility [201], charged system search [202], water cycle [203,204], colliding bodies optimization [205], multiverse optimizer [206], and black hole algorithm [207]. For instance, in the black hole algorithm, the best solution in the population is considered the black hole, and all other solutions (stars) are pulled toward it. If a star is absorbed, it is replaced by a new random solution.

Finally, there are the metaheuristic algorithms inspired by human behavior, which mimic our ability to acquire knowledge, communicate, interact, etc. An example is the gaining and sharing knowledge-based algorithm, which mimics the ability of humans to exchange knowledge during their lifespan, i.e., at junior and senior levels [208,209,210,211,212]. Another example is the harmony search algorithm, which mimics the search for a melody that is in harmony with a piece being composed [213,214]. Other examples of algorithms inspired by human behavior are the imperialist competitive algorithm [215], group counseling optimization [216], exchange market algorithm [217], and the teaching–learning-based optimization [218,219], among others.

Many of the algorithms mentioned here have variations, based on differences in the iteration process. This aspect adds to the diversity of metaheuristics. There are also hybrid optimization tools that operate with two algorithms instead of one algorithm, with certain coordination and with the purpose of exploiting the benefits of both, i.e., combining the strengths and overcoming the weaknesses of two individual algorithms. Such hybrid algorithms have been increasingly gaining relevance in recent years. For instance, PSO is often regarded as one of the most successful metaheuristic algorithms. Yet, while its exploitation ability is outstanding, it is considered relatively limited when it comes to the general search space exploration. This setback can be overcome through hybridization with GWO. In this way, the good exploration ability of GWO and the good exploitation ability of PSO are combined. Such a PSO-GWO hybrid has been developed by Chopra et al. [220]. In another example, Kamboj et al. highlight that the Harris Hawks optimizer can become easily trapped in a local optimum in constrained engineering optimization problems [221]. To avoid such stagnation, the authors suggest a hybrid Harris Hawks—sine cosine algorithm, and confirm a better outcome compared to the individual algorithms. In another example, Liu et al. hybridize PSO with differential evolution to solve constrained numerical and engineering optimization problems [222]. The authors report that the hybridization improved performance, both in terms of the obtained solution and computational effort. Other hybrid algorithms include the combination of ant colony optimization and GA by Liu et al. [223], artificial bee colony and differential evolution by Xue et al. [224], bees algorithm and GA by Yuce et al. [225], flower pollination algorithm and GWO by Pan et al. [226], multi-verse and the Harris Hawks by Ewees and Abd-Elaziz [227] and the whale optimization algorithm and simulated annealing by Mafarja and Mirjalili [228].

The proliferation of hybrid algorithms underscores a pragmatic response to the fact that no single algorithm excels at all problems. Generalizing from these case studies, hybridization is most advantageous when confronting optimization problems with specific challenging characteristics: (1) highly multimodal and deceptive landscapes, where a strong global explorer (e.g., GWO) is needed to locate promising regions, and a strong local exploiter (e.g., PSO) is required to refine the solution; (2) problems with distinct phases, such as microgrid sizing where an initial broad technology selection must be followed by precise component tuning; and (3) problems where one algorithm is prone to premature convergence (stagnation) and benefits from periodic ‘restarts’ from a companion algorithm. Conversely, hybridization may offer diminishing returns for low-dimensional, convex, or computationally cheap-to-evaluate problems, where the added complexity and parameter tuning of a hybrid scheme may outweigh its marginal performance gains. The decision to hybridize should therefore be guided by the problem’s dimensionality, landscape modality, and computational budget, aligning the complementary strengths of the constituent algorithms to the specific structure of the microgrid optimization task at hand.

The development of metaheuristics with the current multiplicity has led to some criticism. Especially when it comes to some swarm intelligence algorithms, the inspiration from nature and its metaphoric dimension seem to have distracted from the true objective upon some occasions, which is the effective and efficient resolution of optimization problems. Yet, guidance within this plethora can be found through benchmarking platforms. Two benchmarking platforms are common for evaluating algorithmic performance: The Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), IEEE [229] and the Comparing Continuous Optimizer (COCO) [151]. CEC is the most elaborate platform and is widely used to benchmark metaheuristics. It includes a wide range of test functions to evaluate the performance of algorithms. Key evaluation criteria include the solution’s proximity to the optimum and the search time. In practice, to provide a proper impression about the performance of an algorithm, it should be evaluated with a wide range of tasks, including classical test functions and real-world engineering problems. An overview on the best practices for benchmarking algorithms is provided by Beiranvand et al. [230], and further discussion on this topic can also be found in the references [231,232,233].

Table 3 provides a list of benchmarking functions that are used to evaluate metaheuristic algorithms [234]. Taking the Sphere function as an example, the number of dimensions can be set with the value of n, and the boundaries of the search space with the range of x. For instance, if n = 10 and x is an integer in the −20 to 20 range, then there are 4110 possible combinations for this objective function. It is already clear that the minimum of this function is at xi = 0. Knowing that, metaheuristic algorithms can be tested for their ability to find, or at least approximate, the optimum. The solutions reached by different algorithms and their computational cost (number of iterations, calculation time, etc.) can then be contrasted for benchmarking purposes.

Table 3.

Benchmark functions to evaluate metaheuristic algorithms.

An important concept in optimization is the no-free-lunch (NFL) theorem suggested by Wolpert and Macready [235]. NFL implies that modelers have no easy fix (i.e., free lunch) to the diversity of optimization problems, i.e., an algorithm that outranks all others in all kinds of problems, and hence could be used as a global standard. This implies that it is the proper understanding of the characteristics of the objective function that provides the basis for an adequate choice of optimization algorithms. Thereby, the benchmarking provided by recognized platforms, such as CEC and COCO, which cover a wide range of test functions, provides a solid reference in the choice of algorithms. Comparative studies that contrast the performance of several algorithms used in a certain field also provide a valid guidance for future work.

4. Microgrid Optimization Algorithms

The historical dominance of ES in microgrid optimization, exemplified by tools like HOMER, stems from the field’s early focus on low-dimensional problems. A classic PV–wind–battery–diesel system, with discrete sizing options for the four main components, might entail a few thousand possible configurations. While each configuration requires a computationally intensive annual simulation (e.g., 8760 hourly time steps), the total search space often remains manageable for ES. However, as argued in Section 2, the evolution toward smart, multi-energy microgrids introduces a combinatorial explosion of decision variables: choices among multiple storage chemistries, the integration of thermal components and EVs, and parameters for digital control strategies. This high-dimensionality renders ES computationally intractable. The empirical evidence for this paradigm shift is clear. For instance, Dufo-Lopez et al. demonstrated that optimizing a PV–wind–battery–diesel system with a high resolution and multi-objective constraints would require over 9 days of computation, using ES to evaluate 81 million combinations. Implementing GA via the HOGA software yielded a high-quality solution in just 66 min—a reduction in computation time to under 0.5% of the ES requirement [123]. Similarly, Sigarchian et al. replicated the global optimum for a complex PV–CSP–Battery–Propane microgrid using PSO in one-sixth of the time required by ES [236]. These case studies provide a fundamental validation: for the complex microgrids of the present and future, metaheuristics are not merely convenient but essential to deliver solutions within practical timeframes.

The literature reveals a rich tapestry of metaheuristic applications, with performance being contingent on the specific problem landscape. Table 4 provides a comparative summary of key case studies. Broadly, algorithms can be categorized by their demonstrated strengths in the microgrid context. Established performers such as GA and PSO remain widely used due to their robustness and mature implementations. GA, embedded in tools like iHOGA, has proven highly effective for general-purpose microgrid sizing [237,238]. PSO is frequently reported to converge rapidly with near-optimal solutions, offering a reliable balance between exploration and exploitation [239,240].

Table 4.

Comparison of metaheuristic algorithms in microgrid sizing case studies.

Newer swarm-based algorithms often demonstrate marginal to significant improvements in solution quality, which is attributed to their sophisticated exploration mechanisms. GWO has shown consistent performance, and in some cases slightly outperforms GA in final LCoE [241]. Algorithms like the grasshopper optimization algorithm [242], Harris Hawks optimization [244], and manta ray foraging optimization [243] have topped comparative studies in specific cases, suggesting their efficacy in navigating high-dimensional, multimodal search spaces. The social spider optimizer outperformed several contemporaries, including GWO and the whale optimization algorithm, in a constrained sizing problem [247]. This diversity underscores the NFL theorem: no single algorithm is universally best. The “best” choice is inherently linked to the problem’s dimensionality, constraint rigidity, and landscape modality. Certain algorithms, such as the improved Archimedes optimization algorithm, demonstrated superior solution quality for specific, constrained problems, while GWO converged faster [246].

Recognizing the complementary strengths of different metaheuristics, hybrid algorithms have emerged as a powerful approach for the most challenging optimization problems. These hybrids strategically combine a global explorer with a local refiner. An example is the GWO-PSO hybrid, which leverages GWO’s broad exploration to identify promising regions of the search space and PSO’s strong exploitation to converge precisely with the optimum. Suman et al. applied this hybrid to a complex PV–wind–battery–biogas–diesel system and found that it outperformed a suite of standalone algorithms, including ant lion optimization and artificial bee colony, in achieving a superior trade-off between LCoE and reliability [245]. Other successful hybrids, such as GWO–Sine Cosine [248] and harmony search–simulated annealing [249], reinforce the principle that hybridization is particularly advantageous for microgrid problems involving multi-technology portfolios, strict multi-objective constraints, and highly deceptive solution landscapes.

The collective evidence from these case studies allows us to move from isolated results to generalizable guidelines. Algorithm selection should be a deliberate choice informed by problem characteristics:

- -

- For traditional, low-dimensional sizing: If the problem involves a handful of well-established components (e.g., standard PV–battery–diesel), ES (e.g., using HOMER) remain viable. For faster results, GA or PSO are excellent, proven metaheuristic alternatives.

- -

- For higher-dimensional, multi-technology design: When the design space expands to include novel storage, sector coupling, or multiple technology options, prioritize algorithms with strong exploration capabilities. GWO or manta ray foraging are strong candidates to effectively navigate the enlarged search space.

- -

- For complex, constrained, and multi-objective problems: For optimizations with stringent reliability (LPSP), environmental, or cost objectives, consider hybrid algorithms (e.g., GWO-PSO). Their balanced approach is tailored to find robust solutions in complex, constrained landscapes.

- -

- The pragmatic benchmarking step: Given the NFL theorem, the most reliable approach for a specific, novel microgrid project is to shortlist two to three promising algorithms based on the above guidelines and benchmark them on a simplified version of the problem. This empirically identifies the most efficient solution for the task at hand.

This framework emphasizes that effective optimization is not about finding a mythical “best algorithm” but about matching the algorithm’s intrinsic search strategy to the signature of the microgrid optimization problem.

While the comparative studies in Table 4 are invaluable, a significant barrier to systematic progress is the lack of standardized, high-dimensional benchmark problems based on real-world multi-energy microgrids. Current comparisons often use different case studies, load profiles, and cost assumptions, making direct, unequivocal algorithm ranking difficult. Future research efforts must prioritize the community development of open-access benchmark suites that include high-resolution data, a validated simulation engine, and known optimal solutions. This would provide a common ground for rigorous, reproducible comparisons and accelerate the development of next-generation optimization tools that are capable of designing truly sustainable and resilient energy systems.

5. Conclusions

This review has systematically examined the convergence of microgrid engineering and metaheuristic optimization, charting a necessary paradigm shift driven by escalating system complexity. The transition from simple, low-dimensional hybrid systems to smart, multi-energy microgrids—characterized by high dimensionality from sector coupling and fine data granularity from digitalization—renders classical ES methods computationally intractable for forward-looking design. Consequently, metaheuristic algorithms are expected to evolve from a convenient alternative into an essential toolkit.

The analysis of case studies (Section 4) confirms that metaheuristics such as GA, PSO, and GWO can identify near-optimal solutions in a fraction of the time required by ES, often achieving computational savings exceeding 90%. Their performance is best understood through their inherent search philosophies: evolutionary algorithms (e.g., GA) provide robust, general-purpose solvers; swarm intelligence algorithms offer a spectrum from strong exploitation (e.g., PSO) for rapid refinement to strong exploration (e.g., GWO) for navigating high-dimensional, multimodal search spaces. The NFL theorem correctly asserts that no single algorithm is universally superior. Therefore, effective algorithm selection must be guided by the specific signature of the microgrid optimization problem at hand.

For practitioners, selecting an appropriate metaheuristic begins with characterizing the problem’s dimensionality (number of interdependent technology and sizing variables), landscape modality (influenced by discrete technology choices), constraint rigidity, and computational budget. For traditional, low-dimensional sizing tasks, ES or established tools remain viable, while GA or PSO offer efficient metaheuristic alternatives. For high-dimensional designs involving novel technology portfolios or multi-energy integration, algorithms with strong exploration capabilities are advisable. For problems requiring fine-tuning or with smoother landscapes, strong exploiters like PSO are effective. For the most complex problems, hybrid strategies (e.g., GWO-PSO) that sequentially balance exploration and exploitation are increasingly valuable. Engineers should adopt a pragmatic approach: benchmark a few candidate algorithms on a simplified problem, leverage documented successes from similar case studies, and favor algorithms with adaptive parameter tuning to reduce the calibration overhead.

Future microgrid optimizers must account for pervasive uncertainties—in renewable generation, load profiles, economics, and component performance—to ensure reliable and cost-effective operation. Deterministic approaches risk under- or over-sizing systems. Metaheuristics are particularly well-suited for integration with stochastic, robust, or chance-constrained optimization frameworks, due to their ability to handle non-linear, non-convex search spaces. The next evolution will involve adaptive metaheuristics that can update solutions in response to real-time operational data, bridging the gap between design-stage planning and operational resilience.

The central thesis of this review—that increasing problem dimensionality mandates a shift to metaheuristics—is now widely accepted. However, rigorous comparison and advancement of algorithms are hampered by the lack of standardized, high-dimensional benchmarks based on real-world, multi-energy microgrids. To propel the field, a concerted effort is needed to develop open-access benchmark suites. These should be created through collaboration between academia, industry, and standardization bodies, and must include the following: (1) a complete problem definition with high-resolution data, (2) a validated reference simulation engine, (3) known optimal or best-known solutions for verification, and (4) standardized key performance indicators for algorithms (solution quality, convergence speed, robustness). Effective benchmarks will be modular, scalable, and eventually incorporate stochastic elements to evaluate performance under uncertainty. Establishing such a common testing ground is imperative for meaningful algorithm comparison, innovation, and the development of trusted tools for engineering practice.

The evolution of microgrids into smart, multi-energy systems is inexorably linked to the adoption and refinement of metaheuristic optimization. Their role will only grow, as digitalization enables data-driven, real-time system adaptation. Ultimately, the successful deployment of these complex systems depends not only on algorithmic advances but also on the parallel development of supportive regulatory frameworks that ensure secure, equitable, and market-integrated operation. This review provides the landscape and roadmap to navigate this critical intersection of energy engineering and computational intelligence. Finally, this work underscores that advanced metaheuristic optimization is not merely a computational tool but an essential enabler for the sustainable design and operation of the next generation of microgrids, directly contributing to decarbonization and energy resilience goals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.Z., S.M.; methodology, G.Z., S.M.; validation, G.Z., S.M.; formal analysis, G.Z.; investigation, G.Z.; resources, G.Z.; data curation, G.Z.; writing—original draft, G.Z.; writing—review and editing, G.Z., S.M.; visualization, G.Z.; supervision, G.Z.; project administration, G.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Ghassan Zubi was employed by the company HyStandards GmbH. The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| CEC | Congress on Evolutionary Computation |

| CHP | Combined Heat and Power |

| COCO | Comparing Continuous Optimizer |

| DIRECT | Dividing Rectangles Algorithm |

| DSM | Demand-Side Management |

| ES | Exhaustive Search |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| FESS | Flywheel Energy Storage System |

| GA | Genetic Algorithms |

| GWO | Gray Wolf Optimizer |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| LCoE | Levelized Cost of Electricity |

| Li-ion battery | Lithium-Ion Battery |

| LFP battery | Lithium–Iron–Phosphate Battery |

| LPSP | Loss of Power Supply Probability |

| Na-ion battery | Sodium-Ion Battery |

| NFL | No Free Lunch |

| P2P | Peer-to-Peer |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| PVT | Photovoltaic Thermal Hybrid Solar Collector |

| V1G | Unidirectional Smart Charging |

| V2G | Vehicle-to-Grid |

References

- Thirunavukkarasu, M.; Sawle, Y.; Lala, H. A comprehensive review on optimization of hybrid renewable energy systems using various optimization techniques. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 176, 113192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavadias, K.A.; Triantafyllou, P. Hybrid renewable energy systems’ optimisation, A review and extended comparison of the most used software tools. Energies 2021, 14, 8268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Wind Energy Council. Global Wind Report 2024; Global Wind Energy Council: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, E.; Kumar, P.; Kumar, S.; Adelodun, A.A.; Kim, K.H. Solar Energy: Potential and future prospects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 894–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency. Global EV Outlook 2024; IEA: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2024 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- International Energy Agency. The Future of Heat Pumps; IEA: Paris, France, 2022; Available online: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/4713780d-c0ae-4686-8c9b-29e782452695/TheFutureofHeatPumps.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).