Abstract

The Dal Lake ecosystem is a vital freshwater body situated in the heart of Srinagar, Kashmir, India. It is not only a natural asset but also a cornerstone of environmental health, economic vitality, cultural heritage, and urban sustainability. In the last few decades, the condition of the lake ecosystem and water quality has deteriorated significantly owing to the intensification of the eutrophication process. Effective integrated management of the lake is crucial for the long-term sustainable development of the region and the communities that rely on it for their livelihoods. The main reasons for eutrophication are the substantial quantity of anthropogenic pollution, especially nutrients, discharged from the catchment area of the lake and the overexploitation of the lake space and its biological resources. The research presented in this paper aimed to diagnose the state of the lake by analysing trends in eutrophication development and its long-term changes related to the catchment area and lake ecosystem relationships. The research period was 25 years, from 1997 to 2023. Land use and land cover data and water quality monitoring data, which are the basis for trophic state assessment, allowed us to analyze the long-term dynamics of eutrophication in the reservoir. For these purposes, GIS-generated thematic maps were created by using QGIS software version 3.44.1, and an appropriate methodology for quantifying eutrophication was chosen and adapted to the specifics of Dal Lake. The obtained results provide a foundation for a eutrophication management strategy that considers the specificity of the Dal Lake ecosystem and the impact of the catchment area. The outcomes highlighted the varied trophic conditions in different lake basins and the dominance of eutrophic conditions during the study period. The research highlights the complexity of the problem and underscores the need for a comprehensive lake management system.

1. Introduction

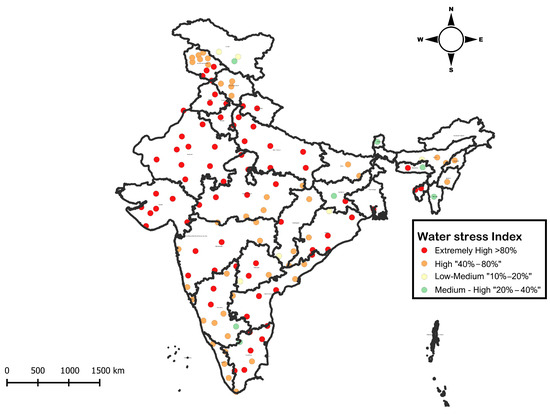

Water resources are essential for sustainable development, human well-being, health, food security, and climate change resilience [1]. Freshwater constitutes less than 3% of the total global water resources, of which only one-third is available for human use [2]. Long-term satellite-based monitoring and assessment have revealed that significant changes in global water resource availability present significant challenges for global sustainability [1]. Climate change, population growth, intensive urbanization, and overexploitation of water resources, including both groundwater and surface water resources, are causing water deficits in metropolitan cities worldwide [3,4]. India, one of the largest countries in terms of population, is the most dependent on water resources and faces a serious water crisis. Due to rapid population growth, industrialisation, agricultural expansion, and poor water management, per capita water availability has decreased, along with decreasing levels of water tables and increased water contamination [5,6]. The water demand is significantly higher than the water supply. Approximately 1.3 billion people live in India, and approximately 163 million people do not have a proper drinking-water supply near their residences. Nearly 600 million people in different regions have insufficient water (Figure 1). In Jammu and Kashmir, a combination of glacial retreat, geopolitical tensions, poor infrastructure, and inefficient water management drives water scarcity [4,7].

Figure 1.

Water stress map of India.

Eutrophication is a serious problem that is increasing globally due to excessive nutrient loading in aquatic ecosystems, primarily due to wastewater discharge, agricultural and urban runoff, and land use change, leading to harmful impacts on aquatic ecosystems, such as disturbances to ecological equilibrium, loss of biodiversity, and water quality degradation [1,8]. The consequences of this process are massive algal blooms, oxygen deficits, deterioration in the living conditions of hydrobionts, and water consumption patterns [1]. Globally, eutrophication affects over 50% of lakes in Asia and 40% in Europe and North America [2], resulting in declines in fish productivity, alterations in aquatic food webs, production of toxins by cyanobacteria, and the loss of ecosystem resources [9,10].

In India, specifically in the Kashmir Valley, the threat of eutrophication within freshwater resources is increasing owing to population increases, untreated sewage discharge into water resources, lack of proper agricultural practices, and poor water management [11]. Dal Lake is an essential freshwater body and has been experiencing significant deterioration for the past few decades. Increasing anthropogenic activity exerts extensive pressure on the lake’s water ecosystem. Increased nutrient loads lead to the transformation of the lake into a eutrophic water body, which adversely affects the water quality, ecosystem health and livelihood of the people [12]. The restoration and management efforts undertaken by the Lake Conservation and Management Authority (LCMA), such as dredging, sewage treatment management, and de-weeding using mechanical machinery, provide a temporary improvement but fail to meet the management policies [13].

The present study aimed to analyse the eutrophication development trend of Dal Lake over 25 years (1997–2023) based on the chosen methodology of trophic state assessment using the ITS (Tropic State Index) and the GIS-based Spatial Temporal Analysis. The results obtained will constitute the basis for developing a Dal Lake management strategy.

2. Study Area

2.1. Location and Characteristics of Dal Lake

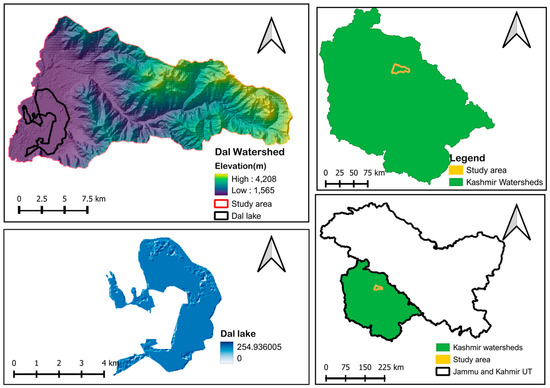

Dal Lake is located between 34°04′ and 34°11′ N and 74°48′ 74°53′ E in the Northeast of the Srinagar valley in the western Himalayas (1583 m above sea level). The lake embraces a total area of above 23 km2, of which approximately 12 km2 is the total open water spread area. The Dal Lake catchment is spread over 314 km2 and is divided into sub-catchments: (1) Tailbal Dachigam, (2) Hillside, (3) North sub-catchment, and (4) Centre sub-catchment. Among the sub-catchments of the Dal Lake, 70% of the area distribution of the drainage catchment is contributed by the Tailbal Dachigam sub-catchment [14]. The lake is divided into four basins: Hazaratbal, Nishat, Nigeen, and Gagribal. They are connected through interconnecting channels. Telbal Nallah, also known as the Dachigam stream, is the primary inflow entering the northern side of the lake through the Hazaratbal Basin. The inflow stream originates from the Marsar lake in the Dachigam sub-catchment [15]. The shoreline extends approximately 15.5 km2 and is surrounded by Mughal-era gardens and hotels, making it a tourist attraction, and has been regarded as the cradle of civilisation in the Kashmir valley, known as the ‘liquid heart ‘of Srinagar city [16]. The water retention capacity of Dal Lake is approximately 15.45 million cubic meters (Mm3). The basin of the lake primarily has crystalline rock beneath the basin and is part of the Tethyan Geosyncline. The Kashmir Valley is surrounded by the Himalayas in the north and the Pir Panjal range in the south. The climate is principally affected by its geographical location, shown in Figure 2 [17].

Figure 2.

Location of Dal Lake in Srinagar.

The lake is classified as a warm monomictic lake with thermal stratification throughout the year. The water temperature of the lake changes between 1° and 11 °C during the winter season, whereas in the winter, the air temperature drops to as low as −11 °C, due to the periodic freezing of the lake. During summer, the temperature is between 12° and 30 °C [18].

2.2. Historical Origin of Dal Lake

Dal Lake in Srinagar, Kashmir, has a profound history, rooted in both myth and geology. Old legends credit the sage Durvasa with its creation, whereas geologists propose its beginnings as either a remnant of a Pleistocene lake or a floodplain lake [19]. In the history of books, it is mentioned that in the 18th and 19th centuries, Srinagar city started growing towards the lake, resulting in far-reaching changes in its surroundings that laid the formation of the bunds that divided the lake into three sectors, viz. Bod—Dal, Lokut Dal and Sonder Khun [19]. The origin of the Dal Lake can be traced to the Pleistocene–Holocene period, when the Kashmir valley was captured by a water body known as Lake Karewa (Wular-Dal paleo—lake system). Processes like tectonic upliftment and sedimentation proceeded and resulted in the lake’s gradual change that left behind smaller residual lakes, including Dal Lake, Wular, Manasbal and Anchar [20]. Human settlements were established at Dal Lake more than 2000 years ago, and Nagas and Aryans have been quoted in early Kashmiri records, which are believed to have been settlement areas around the lake periphery. By the 3rd century BCE, under Ashoka’s rule, Srinagar was considered an essential urban centre near Dal Lake [21]. During the Sultanate period (14th–16th centuries), Dal Lake and its catchment area became central to the development of Srinagar city, providing people with livelihoods, water, transportation, and food resources. Dal Lake was widely used for irrigation and fisheries reasons. The two canals, Nallah Amir Khan and Nallah Mar, were established during that time to have conveyance to other water bodies, as the lake connected with the Jhelum river, which helped in regulating the inflow and drainage [14]. During the Mughal period (16th–18th centuries), Emperor Akbar and later Jahangir transformed the Dal Lake into an attraction of art, architecture, and recreation. Around the shoreline of the famous Mughal gardens, such as Nishat Bagh, Shalimar Bagh, Chashmashahi, and Naseem Bagh, they were built between 1616 and 1635 CE. These gardens will have Mughal landscape designs, integrating water terraces and panoramic lake views [22]. After the downfall of the Mughal dynasty, the lake and its catchment received neglect during the Afghan and Sikh rule (18th and 19th centuries), and it was found that encroachments increased, and part of the lake was transformed into floating gardens (Raad) and used for vegetable cultivation. These floating islands are formed of decomposed vegetation and soil, and people derive their livelihoods from them. However, accelerated siltation and nutrient accumulation within the lake area have also become a concern [23].

In general, in addition to the different basins, the Dal can be roughly differentiated into the open water body and the parts mainly in the west and southwest that consist of marshy lands and numerous inhabited islands. These islands, with their vegetation area and artificially constructed floating gardens, are the place for residents, who are involved in other work such as crafts and trades onshore and on the lake and occupied by market gardeners, who cultivate the floating gardens and lotus fields [24]. A Dal Lake farmer paddles his vegetables and lake goods to market. Up and down the river go the dungs. Floating gardens consist of long strips of lake reed, approximately six feet in width. These strips can be moved from location to location and are anchored at each corner by poles inserted into the lake bottom. During the Dogra rule (1847–1947), tourism and navigation were established in Kashmir. The introduction of the houseboats (Doongs) by British residents transformed Dal Lake into a colonial-era resort destination [24].

After the independence of India, Dal Lake became both an ecological and socio-economic attraction point for Kashmir. However, due to rapid urbanization, population growth, and the ecological condition of the lake, it has deteriorated significantly. Studies from the 1970s onwards have revealed progressive eutrophication, weed growth, and siltation [25]. In the 1990s, there were extensive encroachments of environmental regulations, such as direct sewage inflows from the Srinagar catchment into the Dal Lake, which caused serious visible degradation. The lake area reportedly decreased from 25–26 km2 (early 20th century) to approximately 20 km2 by 2020 [26]. To address these problems, the Lake Conservation and Management Authority (LCMA), formerly known as the Dal Development Authority, was established in 2012 to address the problems of the Dal Lake and put efforts into its conservation and protection.

2.3. Geology and Geomorphology of Dal Lake

Dal Lake occupies a significant area of the western Himalayas and reflects a complex geological structure that shows both its tectonic setting and sedimentary evolution. Scientists believe that Dal Lake has a post-glacial origin and is considered a remnant of a vast Pleistocene lake that was once spread all over the Kashmir Valley. The tectonic shift and fluvial processes, followed by the transformation of the glaciers, resulted in the gradual separation of the Jhelum River from the present basin. The alternative hypothesis is that the origin of the lake is from the old flood spill channels of the Jhelum River [27]. According to the prevailing theory, Dal Lake is the remnant of a vast Pleistocene lake that once covered the entire Kashmir valley during the post-glacial period approximately 2.5 million years ago [18].

Geologically, the Kashmir Valley is an intermontane synclinal basin bounded by the Pir Panjal Range in the southwest and the Zanskar Range in the northeast, with Dal Lake located in one of its central lowest depressions [28]. The bedrock geology of the lake region comprises Siluro Devonian quartzite, shale, and limestone from the Zabarwan Hills. Thick layers of Quaternary Karewa deposits, which include lacustrine clays, silts, sands, and peat, are layered on top of these deposits and represent different stages of the ancient Karewa Lake’s depression [25]. The seismic vulnerability of the Dal Lake area is classified as Zone V on the seismic Zoning Map of India, showing the most severe earthquake zone where mostly frequent damaging earthquakes of intensity IX could be expected [14]. The lithology of the Dal Lake Basin is significantly led by fine-grained clays and organic silts interspersed with detrital material, which is available from the Telbal-Dachigam catchment. It introduces quartz, feldspar, and calcite-rich sediments, whereas urban runoff contributes organic-rich deposits, specifically in Hazratbal and the Hazratbal basins [18]. The catchment area of the Dal Lake is characterised by geological formations dominated by alluvium, Karewas, Triassic Limestone, Panjal Taps, Agglomeratic and pyroclastic slates, conglomerates and pyroclastic products [29].

The geomorphological evolution of Dal Lake has been significantly affected by the Dachigam Telbal Nallah System, which signifies the primary surface water input to the lake and is supposed to be maintained on two major structural lineaments that dominate its sequence and sediment transport capacity. By depositing sediments, migratory channels, and forming deltas at stream confluences, this network of streams, along with many minor tributaries and springs, has significantly influenced the interior shape of the lake [30,31]. The extension of marshes and floating gardens, interconnected with reduced water circulation, has increased internal nutrient cycling and sediment trapping, which has significantly increased vulnerability to eutrophication.

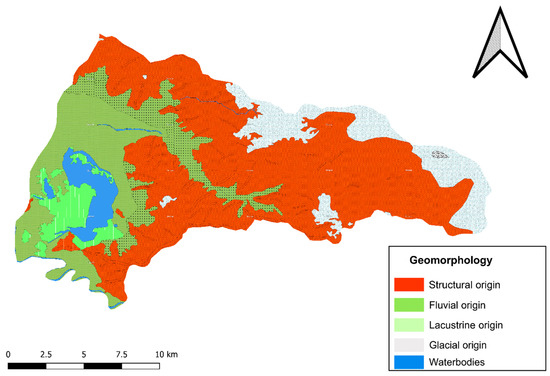

The geomorphological map of Dal Lake and its catchment area, shown in Figure 3, represents a detailed view of the major landscape-forming processes and spatial patterns that explain the physical characteristics of the basin and reflect the integrated influence of tectonic, fluvial, lacustrine, and glacial processes that have influenced the shaping of the current landscape over geological time.

Figure 3.

Geomorphological map of Dal Lake and its catchment.

The structural origin is dominated by the eastern and northern parts of the catchment. These areas have formed mainly because of tectonic processes, such as folding, faulting, and uplift, which are the main features of the NW Himalayan setting. The areas are occupied by hard rocks (such as Panjal Traps, slates, and limestones) and mostly have steep topography, escarpments, and ridges that allow direct runoff towards the central valley. This structural makeup is responsible for the high relief and shaping of the drainage that goes into the catchment.

The areas with a fluvial origin (shown in green in Figure 4) are connected to the zones where the water and sediment transported by rivers and streams (especially from Telbal and Dachigam Nallahs) have created extensive alluvial fans, channels, and flood plains. These areas are also known for their fertile soils, moderate slopes, and continuing active disposition and relocation of channels. In the movement of the sediments from the higher structural terrain to the lower reaches of the catchment and along the periphery of Dal Lake, these fluvial processes have played an essential role [32]. Lacustrine (light green in Figure 4) and glacial origin areas (white in Figure 4) are dominant near the Dal Lake vicinity. These lacustrine zones were formed by ancient lakes and ponding events that were rich in fine silt and clay sediments, which settled down, developing the level terraces and wetland soils rich in organic matter, whereas the glacial zones indicate the remnants of the post glaciation as moraines, glacial outwash plains, and other depositional objects from the Quaternary period and evolution of the Dal lake contributed from that period [33].

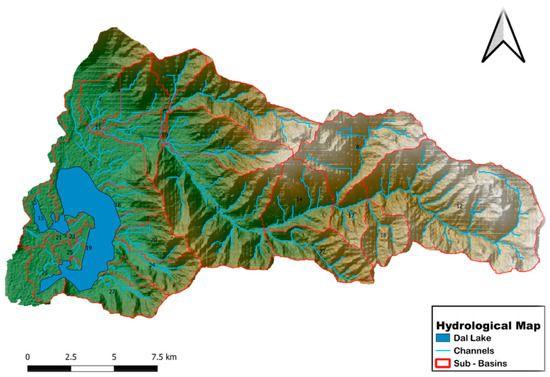

Figure 4.

Hydrological model of Dal Lake and its catchment area.

2.4. Hydrology and Bathymetry of Dal Lake

The hydrology of Dal Lake is controlled by a catchment of approximately 337 km2, with the primary inflow accounting for 80% of the water supply through the Telbal Nallah system and the remaining 20% from all other streams [34]. There is an oligotrophic Marsar lake at a high altitude in the Himalayas, which provides water supply to Dal Lake and maintains the lake’s feeding. The lake has three outlets: (1) from the western side through the Nigeen basin, which connects to the Khushal Sar wetland via the Nallah Amir Khan channel; (2) an outlet of the lake open towards the Brari Nambal wetland; and (3) an outlet that goes directly to the Jhelum river via the Tsunti kul water channel [35]. Lake hydrology and its catchment are influenced by multiple interactions of climatic, topographic, and geomorphic factors that regulate the inflow and outflow and maintain the water balance dynamics of the lake. The hydrological model of Dal Lake is shown in Figure 4.

The hydrological map provides an overview of Dal Lake and its catchment area, illustrating the main lake area (in blue), the network of inflowing and outflowing channels, and delineated sub-basins (red lines). The hydrological system highlights a network of streams originating from the Zabarwan range and adjacent uplands, all flowing towards Dal Lake and determining the maintenance of the annual water balance and water feeding. The map in Figure 5 also shows the various outflows via different channels, whereas various sub-basins demonstrate the spatial configuration of water flow and runoff contributions within the watershed. This unique hydrological connectivity across the central Kashmir basin, where lake outflow is mainly regulated through the Nallah Amir Khan, which connects Dal Lake to the Anchar Lake and extends further via the Doodhganga—Jhelum system, helps maintain the water balance in Dal Lake.

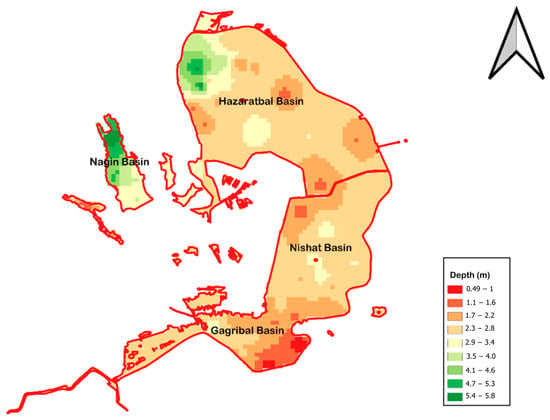

Figure 5.

Bathymetric map of Dal Lake.

The bathymetry of Dal Lake plays an essential role in hydrodynamics, sedimentation processes, and ecological vulnerability. Surveys and published data revealed that the mean shallow depth of the lake is around 1–2 m, with maximum depths recorded up to approximately 5–6 m in the central basins [36]. Zutshi and Rashid Uddin reported, based on lake maps and surveys by Thomas George Montgomerie and their comparison with the latest lake dimensions, that the open water of Dal Lake is 10.56 sq. km [18]. The depth of the Dal Lake ranges from 2.5 m to 6 m, with a length of 7.44 km and a width of 3.5 km [8]. The bathymetric map of Dal Lake, shown in Figure 5, provides a detailed visual representation of the lake depth distribution across the different basins.

The map illustrates the depth variation, with shallower zones of depth (0.4–2.8 m) observed in the Nishat and Gagribal basins, whereas deeper zones of depth (up to 5.8 m) are observed in the Nagin and North Hazaratbal basins. Table 1 illustrates the physical and morphological dimensions of Dal Lake.

Table 1.

Morphological characteristics of Dal Lake [18].

There has been a significant change in the morphology of the lake during recent decades due to human impact, and the lack of ecosystem has been elevated because of agriculture, irrigation, water consumption, and, more specifically, changes have been identified in shallow lakes, which are more sensitive to environmental alterations and are represented by unfavourable morphometric parameters [37].

3. Land Use and Land Cover

Land use and land cover (LULC) dynamics play a crucial role in the ecological and hydrological integrity of Dal Lake and its catchment. Rapid urbanization, deforestation, and agricultural development have tremendously increased the changes in the land cover patterns within the lake catchment over the past few decades [38]. Such changes in land cover patterns have directly resulted in elevated sedimentation and lake silting, water pollution, nutrient enrichment, adverse deterioration of water quality, and disturbance in the lake ecosystem. The most spectacular and dangerous symptom of this is eutrophication, which leads to the continuing decline of the Dal Lake [39]. Previous studies revealed that uncontrolled urban expansion, followed by the transformation of agricultural and wetland areas into residential areas, is the primary driver of the deterioration of the lake ecosystem [38]. Moreover, a change in floating gardening has been observed: once an agricultural gem for the residents of Dal Lake, there is now a significant loss of traditional agricultural practices and livelihoods connected to the lake [38]. The higher catchment also faces significant forest and rangeland degradation, which leads to an increase in soil erosion and sediment transport into the Dal Lake [13].

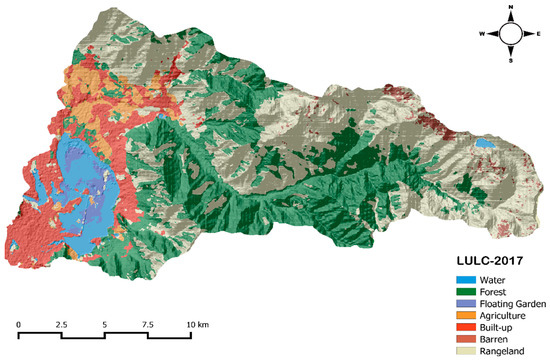

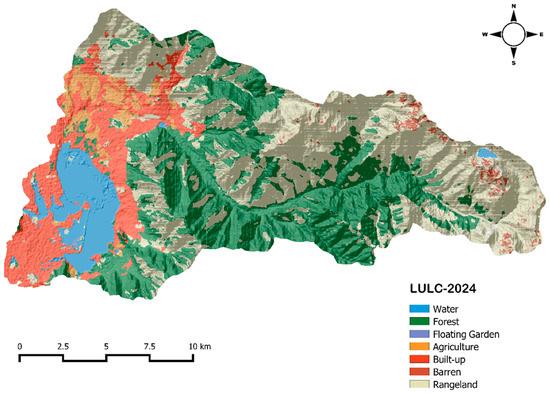

To evaluate the spatial and temporal land cover changes within the Dal Lake catchment, LULC maps for the period of 2017–2024 were created (Figure 6 and Figure 7, respectively). The Esri Landcover Explorer dataset (2024), which is based on Sentinel-2 imagery and deep learning classification, was used as the primary data source. The data were managed, analysed, and visualised in QGIS (v3.34), and area computation from the raster data and change detection were performed. The maps were then evaluated to quantify the spatial changes across the seven LULC classes: water, forest, floating gardens, agricultural, built-up, barren, and rangeland areas.

Figure 6.

Land use and land cover of the Dal Lake catchment in 2017.

Figure 7.

Land use and land cover in the Dal Lake catchment in 2024.

Table 2 shows the results of the quantitative analysis, which illustrates the significant LULC 7-year changes over the period from 2017 to 2024.

Table 2.

Area statistics of LULC classes in Dal Lake catchment for 2017–2024 period.

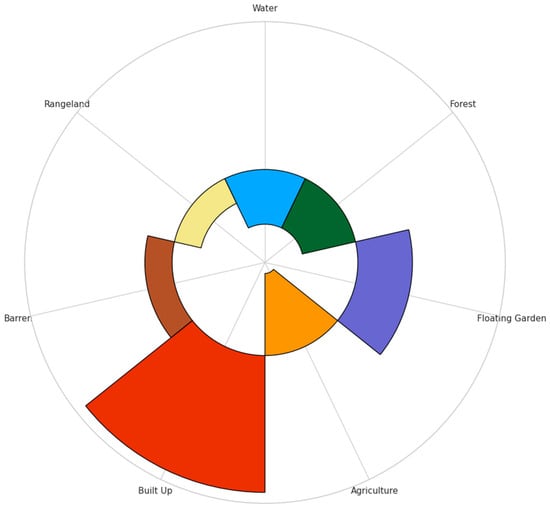

The built-up area of the Dal catchment increased significantly by about 19.1% from 33.80 × 106 m2 in 2017 to 40.26 × 106 m2 in 2024, a total gain of 6.46 × 106 m2, revealing the expansion of the urban encroachments around the lake. Whereas the agricultural area declined by approximately 17.56% from 11.50 × 106 m2 to 9.43 × 106 m2, the area under the floating gardens showed a significant reduction by 96.53% from 4.74 × 106 m2 to 0.16 × 106 m2. These declines are associated with the previous research on aquatic vegetation decreases and land transformation for residential use [38]. Correspondingly, forest and rangeland areas are reducing by around 1.87% and 2.17% from 1.97 × 106 m2 and 2.62 × 106 m2, respectively, revealing that there is significant anthropogenic stress in the upland catchment. Comparatively, the water bodies show expansion of approximately 31.77% because of the restoration activities undertaken by the Lake Conservation and Management Authority (LCMA), also due to hydrological variability. A radial chart of LULC variations is visualised in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Radial chart of LULC change of Dal Lake catchment (2017–2024).

4. Assessment Methodology of Dal Lake Trophic State

4.1. Data Sources

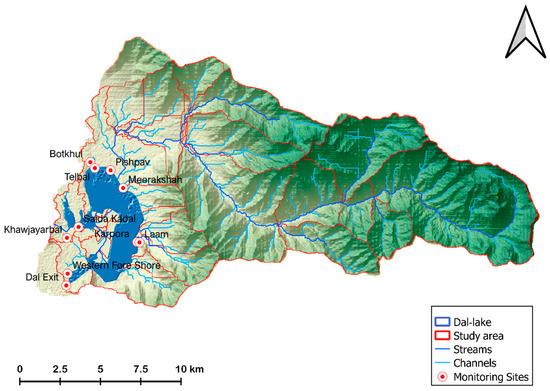

The research study on the Dal Lake ecosystem commenced with data collection, followed by the organisation and statistical evaluation of long-term water quality data. The data were sourced from the Lake Conservation Authority (LCMA) and the Jammu and Kashmir Pollution Control Board (JKPCB) as well as the University of Kashmir (KU) for the period from 1997 to 2023. The monitoring sites are located across the basins of Dal Lake, as depicted in Figure 9. The dataset included the annual values of the following parameters: chemical oxygen demand (COD), total phosphorus (TP), orthophosphate (P-PO4), total nitrogen (TN), ammonium nitrogen (N-NH4), (WT) water temperature (T) as the factors (causes) of eutrophication; however, pH dissolved oxygen (DO) and transparency are indicators of the changes caused by eutrophication.

Figure 9.

Monitoring sites in the Dal Lake.

The data were gathered and cleaned, systematically arranged and managed in Excel format. The descriptive statistical analysis was conducted using R Programming to calculate key summary statistics, mean, median, minimum and maximum values. These metrics help in understanding the distribution of parameters, central tendencies and dynamics of the parameters. The annual trend analysis in the data was carried out to identify any significant changes or patterns in lake water quality for a 26-year period, which was the basis for understanding the eutrophication drivers in the Dal ecosystem.

4.2. Trophic State Assessment Method

The lake eutrophication level can be assessed with a wide variety of trophic state assessment methods, including the Carlon Trophic State Index (TSI) [40]. The OECD classification system and the Vollenweider nutrient loading model are widely used methods [41,42]. The Vollenweider model focuses on the nutrient loading rates and critical thresholds for eutrophication but mostly on the accurate hydrological data, such as inflow volumes, which are difficult to obtain for complex systems like Dal Lake [42]. Determining the trophic status of water, which represents the ecosystem’s metabolism (energy supply, accumulation, and consumption), is a crucial step in evaluating eutrophication. Water ecosystems’ biotic balance, or the equilibrium between the production and decomposition of organic matter produced by aquatic vegetation, is reflected in their trophic state. Therefore, it follows that the ecological status of the water body may be diagnosed using this method of biotic balance assessment. The accurate evaluation of the trophic levels of water bodies remains a significant challenge, linked to its execution and results interpretation, despite the abundance of classifications and quantitative indicators for different types of water created by different authors. There are still significant issues with the accurate measurement of the trophic levels of water bodies, related to both the application and the interpretation of their findings.

Therefore, creating and implementing indicators that align with the objectives of managing and protecting water resources and satisfying the following criteria are highly necessary tasks:

- To represent anthropogenically caused changes in aquatic ecosystems and their fundamental roles.

- To be simply interpretable, based on a small quantity of facts, and flexible for many circumstances.

- To be appropriate for tackling application challenges and process predictions.

- Their evaluation should be simple and have a reasonable cost [43].

Considering the above comparative evaluation of tropical state assessment methods, a reliable, cost-effective and methodology easily adopted for specific conditions was selected to achieve the research objective. In the current study, therefore, the Index of Tropic State (ITS) method was used, which was originally developed and implemented by previous researchers for assessing the tropic condition, demonstrating the ability to easily adapt to a variety of specific conditions in different regions. This approach is grounded in the biotic balance concept, which reflects the essence of the eutrophication process. Consequently, the trophic state of Dal Lake was assessed by applying the ITS approach, which quantitively represents the lake’s biotic balance, which can be calculated on the basis of Equation (1) [18].

where

- pH—pH value

- [DO%]—water saturation with oxygen, measured simultaneously with pH

- a—slope coefficient of pH-DO% linear regression

- n—the number of measurements

The corresponding boundary values and classification range of the ITS index applied for the Tropic State Index are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

ITS boundary values for different trophic states of water [18].

The verification of the assessment results obtained using ITS was performed against classical indices, which demonstrates the strong correlation with Carlson‘s and OECD classification (R > 0.85), while remaining more adaptable to humid subtropical and data-limited environments [44]. Studies on Dal Lake revealed that the use of optical methods for assessing the eutrophication dynamics in Dal Lake having dense aquatic vegetation and turbidity is not reliable and effective [38]. The justification for choosing the method of the trophic state assessment based on ITS is as follows: ITS makes it possible to precisely identify the trophic state based on the biotic balance in water, which is a fundamental characteristic of any aquatic ecosystem.

- ITS is based solely on two typical hydro-chemical water quality measurements, which are essential in the absence of routine monitoring and its limited scale.

- It enables rapid and effective operational monitoring and is straightforward, affordable, and simple to interpret and understand.

- The lack of historical data on conventional eutrophication indicators (chlorophyll-a, nutrients, transparency, etc.) permits a retroactive evaluation of the tropic condition of water.

- An efficient lake management system is ensured by ITS, a numerical indicator that serves as the foundation for developing mathematical prognostic models and resolving engineering and application challenges.

The validity and reliability of the ITS index application in the assessment of the rivers, lakes, dams, reservoirs and coastal sea waters have also been verified by different authors [45,46,47,48].

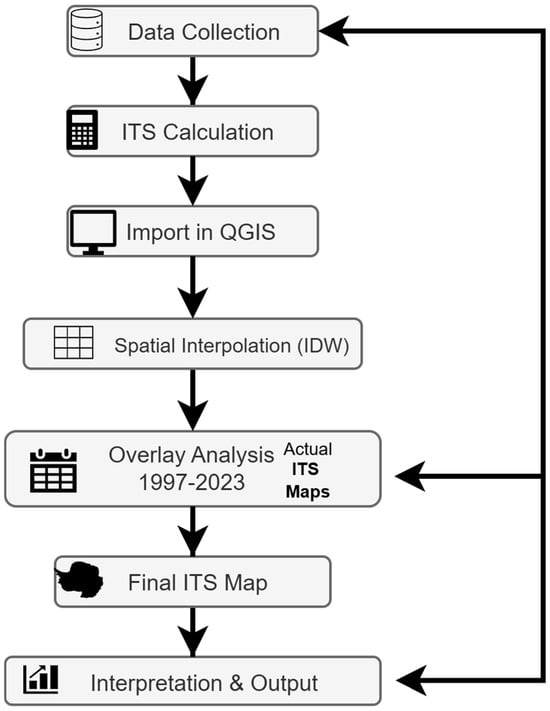

4.3. GIS-Based Spatial Analysis Method

GIS-based geostatistical analysis was performed by using QGIS Software (Version 3.44.1) to visualise the spatial and temporal evolution of eutrophication in Dal Lake in the period from 1997 to 2023. The dataset containing the calculated ITS values, ITS levels and coordinates of monitoring sites was imported into QGIS for spatial analysis. The Inverse Distance Weighting (IDW) technique was employed for the ITS values to spatially interpolate them across Dal Lake. IDW estimates the unknown values based on the weighted average of surrounding sampled points, with nearby sampling points applying significant influence, thus generating a smooth and continuous spatial representation of tropic variability across the different basins of the Dal Lake.

The general mathematical expression of the IDW algorithm used in this study is given as follows:

where

where

- Z(x0)—estimated ITS value at an unsampled location,

- Z(xi)—measured ITS value at the ith sampling point,

- di—distance between the unknown point and the sampled point xi,

- p—power parameter controlling the influence of distance (commonly p = 2),

- n—total number of sampling points considered in the estimation [49].

The interpolated ITS thematic maps were created separately for each year from 1997 to 2023. The final thematic map was created using an overlay technique, where all GIS thematic layers were superimposed to generate the final ITS thematic layer that showed the spatial distribution of eutrophication conditions across different basins of the Dal Lake (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Flow chart of GIS-based method for eutrophication analysis in Dal Lake.

4.4. Data Analysis and Verification

Data analyses were carried out to analyse the long-term trends in water quality parameters that are associated with the eutrophication processes in Dal Lake. The analysis was carried out to evaluate the temporal variability of key parameters pH value, water saturation with oxygen (DO%), nutrient concentrations, TN and TP, and water temperature, transparency and mineral forms of nitrogen and phosphorus to assess the reliability of the ITS as an indicator of the lake tropic condition. The verification of the ITS method applicability for Dal Lake conditions was carried out by correlation and regression analysis between the pH and DO%, a relationship that reflects the changes in biotic balance.

5. Results of Tropic State Assessment

5.1. ITS Assessment Method Results

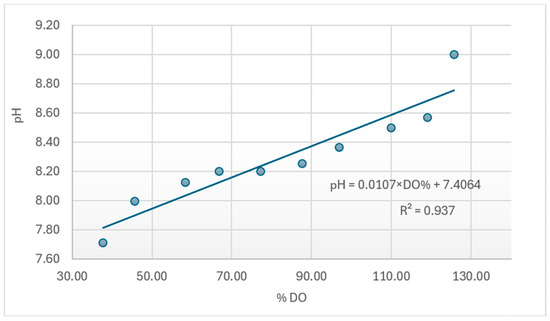

A linear model mathematically explains how a dependent variable (pH) changes with an independent variable, water saturation with oxygen (DO%), together with water trophic conditions, through a linear equation. Linear regression relates more explanatory variables to a response variable using linear coefficients [49]. The precondition of the ITS index application justification requires the confirmation of a linear relationship between pH and DO%, which is observed in the aquatic systems that are experiencing eutrophication. To verify the prerequisite and assess the reliability of the ITS for assessing the trophic status of Dal Lake, a correlation analysis was performed to analyze the interdependence between these variables. The analysis was based on the weighted mean values of pH and DO% from a 25-year monitoring period (monitoring dataset for 1997–2023), providing the statistical foundation for confirming the validity of the ITS approach.

The statistical analysis was carried out at the significance level of alpha = 0.05, with Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) employed to assess the strength of the relationship between pH values and DO%. A strong correlation was observed between the pH and DO% (r = 0.93). The regression coefficient (a), representing the proportional relationship between the pH and DO%, was obtained from the regression equation of the dataset. The result of the regression analysis shown in Figure 11 demonstrates the statistical validity of the relationship used in the ITS model.

Figure 11.

Linear relationship between pH and DO% in Dal Lake.

The highly significant correlation, indicated by the coefficient value (r = 0.93), validated the chosen ITS index for evaluating the tropic state and facilitated the creation of a regression equation tailored to the conditions of the studied water body, serving as a foundation for estimating the tropic state level.

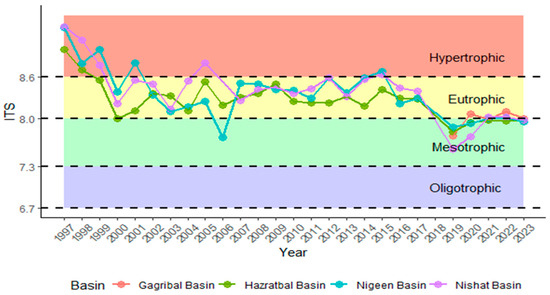

5.2. Temporal Progression of Eutrophication Development Based on ITS Assessment Method

The temporal analysis of the ITS values for Dal Lake for the period 1997–2023 allowed us to evaluate the trends of eutrophication development across all four basins: Hazratbal, Nishat, Nigeen and Gagribal. As shown in Figure 12, the eutrophication status during the late 1990s was significantly high; all the basins were characterised by hypereutrophic status. This is due to the intense nutrient enrichment from the catchment and discharge of untreated sewage into the lake.

Figure 12.

Eutrophication development trend (1997–2023).

Over the studied 25-year period of 1997 to 2023, all the basins were mostly characterized by high trophic status, balancing on the border of eutrophic and hypereutrophic conditions, indicating increased eutrophication development in the lake and the disturbance of its self-purification mechanisms. In the year 2000, the trophic level showed a decreasing tendency from hypereutrophic to eutrophic conditions, indicating a slight improvement in the ecological balance in the Dal Lake. Most probably, the reason behind this is the improvement in the lake management activities by LCMA. Figure 12 clearly illustrates that from the period of 2006 to 2017, all basins of the Dal Lake remained in a state of eutrophic condition, revealing relative stability.

Whereas the Hazratbal basin is showing higher values of the ITS, as compared to the other basins, indicating that it is under high anthropogenic loadings from the inflow streams and nearby residential areas, causing higher eutrophication in the basin. The eutrophication level dropped from the eutrophic level to the mesotrophic level in the years 2019–2020, reflecting the improvement in the Dal Lake eutrophication status, but the level turned back to the eutrophic level afterwards until 2023.

5.3. GIS-Based Thematic Representation of Eutrophication Trends in Dal Lake

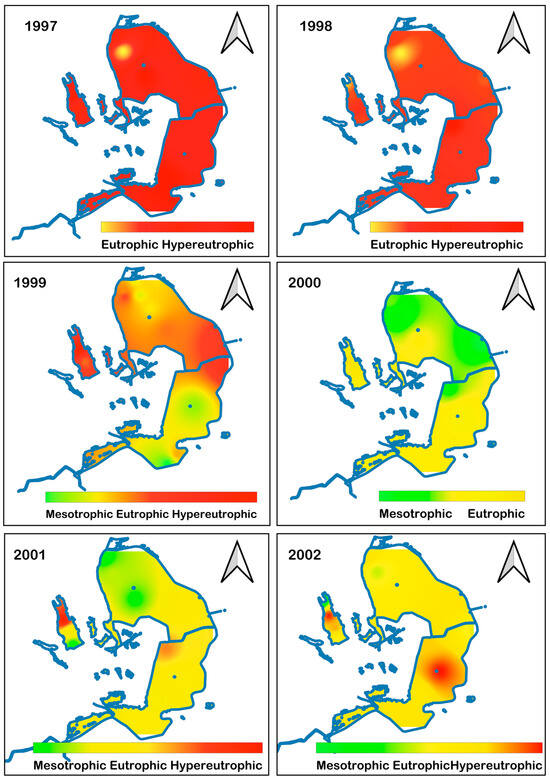

The analysis of the eutrophication development intensity was assessed by using GIS-based mapping of ITS values for the period 1997–2002. The Inverse Distance Weighting (IDW) technique in QGIS was used to interpolate the calculated ITS values at each monitoring site and to produce a series of GIS thematic maps that demonstrate the eutrophication dynamics trends in Dal Lake. The generated thematic maps reveal different spatial variations in the tropic status of Dal Lake (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Spatial variation in eutrophication development in Dal Lake “1997–2002”.

The thematic map clearly illustrates the transition from the hypereutrophic level to the moderate mesotrophic conditions across the basins over the research period. In the years 1997–1998, Dal Lake was in a very unfavorable hypertrophic state, threatening its ecosystem. In the year 1999, it can be seen that the tropical status of the northern and western parts of the Dal Lake shifted to eutrophic and mesotrophic and showed a spatial improvement tendency. This shift to mesotrophic continued to the year 2000, where a significant area of the lake exhibited a mesotrophic state. In the years 2001 and 2002, a larger portion of the lake was in a eutrophic condition, and some parts of the area in the Nigeen basin showed a mesotrophic state in the year 2002. The years 2001 and 2002 showed a more balanced distribution of tropic states, dominated mostly by eutrophic and moderately by mesotrophic, with limited hypereutrophic patches.

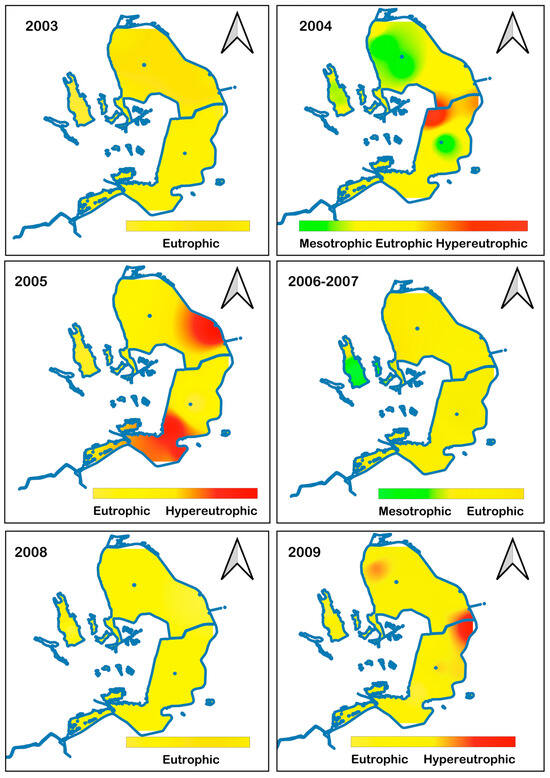

The continuation of the eutrophication variability from the year 2003 to 2009 is shown in the thematic map (Figure 14). In the year 2003, the lake was completely returned to eutrophic conditions. By 2004, the trophic status level of the lake changed to mesotrophic, particularly in the Hazaratbal basin and Nishat basin. But, during the year 2005, specifically in the Hazaratbal and Gagribal basins, it can be seen that the trophic state level changed again into a hypereutrophic condition, while the rest of the area was under eutrophic conditions. In the year 2006–2007, the Nagin basin tropic state level improved to a mesotrophic condition, and other basins of the lake exhibited eutrophic conditions. In 2009, a small part of the Nishat basin showed a hypereutrophic condition, while the whole lake overall showed an eutrophic level.

Figure 14.

Spatial variation in eutrophication development in Dal Lake “2003–2009”.

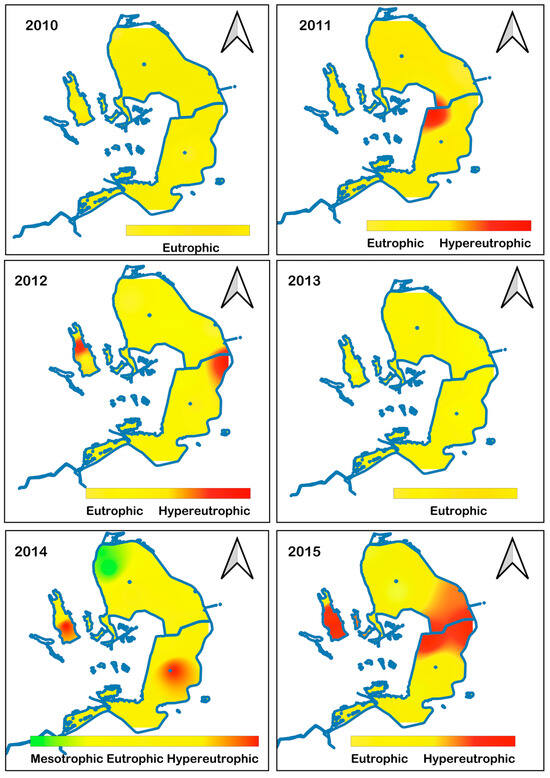

From 2010 to 2015, Dal Lake experienced continued tropic state spatial variability, so the overall area of the lake mostly remained eutrophic (Figure 15). The trophic state level of the lake in the year 2010 was predominantly eutrophic and can be seen in all the basins, whereas, in the year 2011, part of the Nishat basin showed a hypereutrophic condition. In the year 2012, there were more pronounced trends, specifically in the Nishat and Nagin basins, reflecting the tropic state level changes as hypereutrophic patches. In the year 2013, the lake shifted completely into the eutrophic state, showing a slight improvement. In the year 2014, a part of the Hazratbal basin turned into a mesotrophic state, but the hypertrophic patches can be seen in the Nishat and Nagin basins.

Figure 15.

Spatial variation in eutrophication development in Dal Lake “2010–2015”.

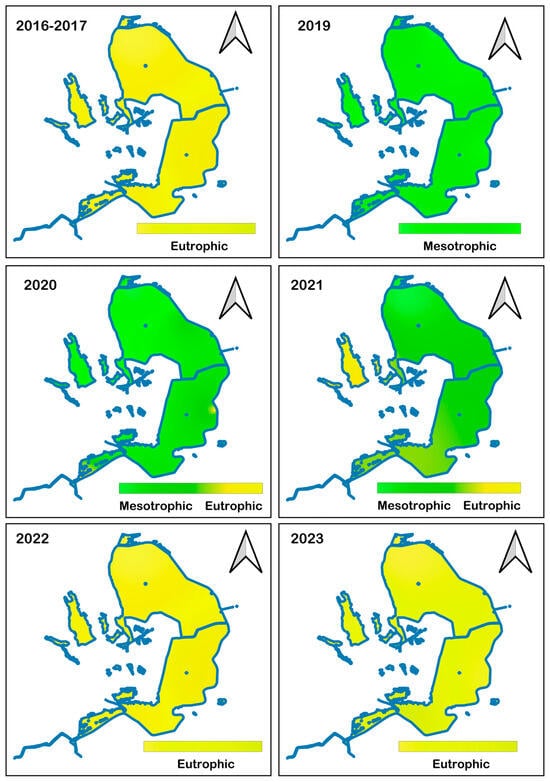

The Dal Lake tropic state condition degraded again in the year 2015, with a large area of hypereutrophic conditions in both the Nishat and Nagin basins. The thematic maps concerning the period 2016–2023, shown in Figure 16, reveal the significant spatial and temporal changes in the lake tropic state. From 2016 to 2017, the whole lake was under eutrophic conditions. The trophic state level of the lake significantly drifted to mesotrophic in the subsequent years 2019, 2020 and 2021, specifically in the central and northern regions of the lake, signifying an improvement in ecological conditions and the temporal stabilization of biotic balance. But, in the year 2021, the Nagin basin achieved the eutrophic level.

Figure 16.

Spatial variation in eutrophication development in Dal Lake “2016–2023”.

However, the trophic state shifted to eutrophic conditions in 2022 and 2023, which is evident in all the basins. These thematic maps clearly illustrate the temporal patterns in the trophic status of the lake, with most of the years significantly dominated by eutrophic conditions.

6. Discussion

Eutrophication of freshwater ecosystems is a key issue in water resource management. This study aimed to assess the trophic status of the Dal Lake and the trends of its long-term development. A reliable eutrophication assessment approach needs to be applied based on an appropriate methodology, which is suitable for adaptation to the specific conditions of the Dal Lake ecosystem. Among numerous eutrophication assessment methods, the biotic balance approach based on the ITS index was selected, which was adopted for the Dal Lake ecosystem and proved to be a reliable assessment method in the conditions of an insufficient monitoring data bank of Dal Lake.

The applied assessment methodology enabled the evaluation of the trophic condition of Dal Lake and its basins without incurring the substantial expenditures associated with collecting water samples and analysing numerous water characteristics, particularly hydrobiological ones. Specifically, it is very useful under an inadequate monitoring system and the inability to provide regular, sufficiently frequent measurements of the full range of eutrophication indicators, whereas the values of pH and DO% are the fundamental hydro-chemical parameters of water quality assessed in routine monitoring.

The Dal Lake’s ecosystem is highly unstable, and its self-purification mechanisms are unable to maintain stable trophic conditions. Fluctuating trophic conditions in the lake over the long term confirm this fact. Increasing anthropogenic pressure, resulting from the delivery of excessive nutrient loads from point and diffuse sources in the catchment area, the excessive exploitation of the lake’s biological resources and its surface for recreational, transportation, horticultural, residential, and other purposes, is straining the self-regulatory capacity of this ecosystem. Furthermore, the situation is exacerbated by changing climatic conditions.

A positive aspect of the research results is that the lake’s condition has been slowly improving, based on a comparison of its initial trophic state in 1998, when the lake was characterised by an extremely high trophic level, with subsequent years. This is the result of activities aimed at rehabilitating the ecosystem and improving its condition and water quality. However, it is important to remember that, as the research has shown, there is a direct correlation between changes in the lake’s catchment area management and its ecological condition, which indicates that without rationalizing land use in the catchment area and reducing external pollutant loads, it will be difficult to achieve measurable results. The spatiotemporal ITS analysis highlighted that Dal Lake experienced significant eutrophication between 1997 and 2023. It also appeared that land use changes and weak wastewater management, anthropogenic loads from the urban areas, impact the Dal Lake ecosystem irreversibly. However, it also appeared that even some separate restoration efforts from the LCMA (e.g., 2019–2021) can improve the lake’s status. The persistent eutrophic state in the Dal Lake signifies the immediate integrated watershed lake management strategy, followed by the catchment nutrient management, enhancing the sewage treatment capacity and technology and regulation of urban encroachment. However, long term ITS/GIS-based monitoring provides an ecologically justified and low-cost framework for the adaptive management and effective restoration and monitoring of the Dal Lake.

7. Conclusions

Dal Lake is not only a natural asset but also a cornerstone of environmental health, economic vitality, cultural heritage, and urban sustainability in Kashmir. An appropriate integrated management approach to the lake is essential for long-term sustainable development of the region and the communities that depend on it. The potential of the lake cannot be underestimated and embraces such aspects of development as environmental sustainability (climate change adaptation and mitigation, biodiversity maintenance, water ecosystems protections and water cycle regulation); economic sustainability (tourism, fisheries, local agriculture and crafts); urban suitability (green mobility, flood management, community integration); as well as social and cultural sustainability. To fully utilise this potential, the prior environmental challenges must be met, including one of the most significant, the mitigation of eutrophication of the lake.

The novelty of this research study consists of the following: (1) the application of the balance approach to the assessment of the trophic state and its adaptation to the specific regional and ecological conditions of the Dal Lake for the first time; (2) the first application of the ITS index to evaluate the eutrophication process in a lake with a humid subtropical climate; (3) the modification of the index calculation formula to the specificity of the lake under study; (4) the confirmation of the viability of employing the selected assessment methodology; (5) the evaluation of the specificity of the course and dynamics of lake eutrophication, accounting for spatial and temporal variations within the lake; (6) the GIS-based spatiotemporal assessment was applied to the Dal Lake first to assess the tropic status of the lake; (7) creation of GIS thematic maps of eutrophication development in the period 1997–2023, allowing us to visualize the tropic status trends of the whole lake and within specific basins with even small spatial and temporal differences. Such results of deep, detailed analysis of eutrophication development for a multi-year period appeared for the first time and cannot be found in other publications.

Author Contributions

I.A. methodology, writing—original draft, data curation, formal analysis, visualization. E.N.D. conceptualization, funding acquisition, writing, review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Research project supported by the program “Excellence Initiative–Research University” for the AGH University of Krakow. Interdisciplinary university grants for research work carried out with the participation of PhD students—1st edition, 2024, number 9709.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used in this study is not publicly available through open data portals; data can be obtained from the corresponding author and organizations based on reasonable requests.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ITS | Tropic State Index |

| LULC | land use land cover |

| LCMA | Lake management and authority |

| JKPCB | Jammu and Kashmir Pollution Control Board |

| TN | total nitrogen |

| TP | total phosphorus |

| COD | chemical oxygen demand |

| NH4 | ammonium nitrate |

| PO4 | Phosphate |

| WT | water temperature |

| T | transparency |

References

- Scanlon, B.R.; Fakhreddine, S.; Rateb, A.; de Graaf, I.; Famiglietti, J.; Gleeson, T.; Grafton, R.Q.; Jobbagy, E.; Kebede, S.; Kolusu, S.R.; et al. Global water resources and the role of groundwater in a resilient water future. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO World Water Assessment Programme. Water and Climate, 2020. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://www.unesco.org/sites/default/files/medias/fichiers/2024/12/Annual%2520report%25202020.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwiG7d77pvORAxU55TQHHQSyIvkQFnoECB8QAQ&usg=AOvVaw2cHgDTtIhQgHCS27CPIKgs (accessed on 4 September 2013).

- Shemer, H.; Wald, S.; Semiat, R. Challenges and Solutions for Global Water Scarcity. Membranes 2023, 13, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musie, W.; Gonfa, G. Fresh water resource, scarcity, water salinity challenges and possible remedies: A review. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhusoodhanan, C.G.; Sreeja, K.G.; Eldho, T.I. Climate change impact assessments on the water resources of India under extensive human interventions. Ambio 2016, 45, 725–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, M.U. Kashmirs Hydro Dilemma: Water Resources Management Challenges. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2023, 11, 822–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I. Water legislation in India as priority aspect of water resources management. J. Civ. Eng. Environ. Archit. 2024, 71, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabalais, N.N.; Turner, R.E.; Díaz, R.J.; Justić, D. Global change and eutrophication of coastal waters. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2009, 66, 1528–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.-L.; Tao, S.; Dawson, R.W.; Li, B.-G. A GIS-based method of lake eutrophication assessment. Ecol. Model. 2001, 144, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Cao, M.; Gao, W.; Cheng, G.; Duan, Z.; Hou, X.; Zhang, Y. Spatial-temporal source apportionment of nitrogen and phosphorus in a high-flow variable river. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 53, 101839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Parvaze, S.; Huda, M.B.; Allaie, S.P. The Changing Water Quality of Lakes—A Case Study of Dal Lake, Kashmir Valley; Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, S.; Singh, S.; Kumar, R.; Malik, S.A.; Sheikh, J.H.; Sudershan, A. Understanding water dynamics in Dal Lake: A comprehensive analysis of physiological parameters and seasonal variations. Water Sci. Technol. 2024, 90, 1250–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.A.; Achyuthan, H.; Krishnan, H.; Lone, A.M.; Saju, S.; Ali, A.; Lone, S.A.; Malik, M.S.; Dash, C. Heavy metal concentration and ecological risk assessment in surface sediments of Dal Lake, Kashmir Valley, Western Himalaya. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.; Jeelani, G.; Shah, R.A. Hydrogeochemistry of Dal Lake and the potential for present, future management by using facies, ionic ratios, and statistical analysis. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 74, 3301–3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, I.A.; Dar, A.Q. Spatio-temporal variation in physio-chemical parameters over a 20-year period, potential future strategies for management: A case study of Dal Lake, NW Himalaya India. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2020, 20, 101102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, R.A.; Ganaiee, Y.A.; Singh, S.P. Hydrogeochemical analysis of an urban lake: A case study of Dal Lake, NW Himalaya, India. Int. J. Appl. Sci. 2023, 9, 251–258. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, S.; Bali, B.S.; Arora, P.; Ali, S.N.; Morthekai, P.; Muneer, W.; Wani, A.H.; Yaseen, A.; Zaman, M.; Ganai, B.A. Apportioning and modeling the anthropogenic fingerprints in a Himalayan freshwater lake over the last ~ 3.7 ka: Insights into pollution chronology and future policy implications. Environ. Chem. Ecotoxicol. 2025, 7, 547–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Neverova-Dziopak, E.; Kowalewski, Z. Assessment of Spatio-Temporal Dynamics of Dal Lake’s Trophic State. Water 2025, 17, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangan Datta. Dal Lake—Sikhara Ride. Available online: https://rangandatta.wordpress.com/2013/09/04/dal-lake-sikhara-ride/ (accessed on 4 September 2013).

- Raza, M.; Ahmad, A.; Mohammad, A. The Valley of Kashmir: A Geographical Interpretation; Carolina Academic Press: New Delhi, India, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, M.A. A Chronicle of the Kings of Kashmir, 1st ed.; Indological Publishers: Delhi, India, 1979; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, A.A. Mughal Gardens in Kashmir: A Review. Int. Educ. Res. J. 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, R.A.; Ganaiee, Y.A.; Singh, S. Examining water quality for pollution status of Dal Lake, Srinagar, India. Int. J. Geogr. Geol. Environ. 2023, 5, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, W.R. The Valley of Kashmir; H. Frowde: London, UK, 1895. [Google Scholar]

- Qadri, H.; Yousuf, A.R. Dal Lake Ecosystem: Conservation Strategies and Problems; Research Gate: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 1453–1457. [Google Scholar]

- World Lake Database—ILEC. Available online: https://wldb.ilec.or.jp (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Kumar, S.; Rao, P.S.; Kumar, D.; Sharma, N. Assessment of Sediments and Application of Hydrodynamic Model for Sediment Management in Dal Lake, India; Central Board of Irrigation and Power: New Delhi, India, 2020; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Vishwakarma, C.A.; Sen, R.; Singh, N.; Singh, P.; Rena, V.; Rina, K.; Mukherjee, S. Geochemical Characterization and Controlling Factors of Chemical Composition of Spring Water in a Part of Eastern Himalaya. J. Geol. Soc. India 2018, 92, 753–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeelani, G.; Shah, A.Q. Geochemical characteristics of water and sediment from the Dal Lake, Kashmir Himalaya: Constraints on weathering and anthropogenic activity. Environ. Geol. 2006, 50, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, M.S. Geomorphological Field Guide Book on Kashmir Himalaya. In International Conference on Geomorphology; Koul, M.N., Ed.; International Association of Geomorphologists (IAG): New Delhi, India, 2017; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Dal Lake. Wikipedia. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dal_Lake (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Rai, S.P.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, B. Estimation of Rates and Pattern of Sedimentation and Useful Life Dal-Nagin Lake in Jammu and Kashmir Using Natural Fallout of Cs-137 and Pb-210 RadioIsotopes; National Institiute of Hydrology: Roorkee, India, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kundangar i, M.R.D. Dal Lake: A Monograph; Kashmir Life: Srinagar, India, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, J.; Qiao, Y. Comparative Study on Water Resource Protection Legislation between China and India. December 2021. Available online: https://www.clausiuspress.com/conference/article/artId/7198.html (accessed on 26 December 2021).

- Dar, S.A.; Srivastava, P. Water Quality Status of an Urban Lake, Dal in Kashmir Himalaya, India. Uttar Pradesh J. Zool. 2021, 42, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Mushtaq, B.; Qadri, H.; Yousuf, A.R. Comparative Assessment of Limnochemistry of Dal Lake in Kashmir. J. Earth Sci. Clim. Change 2018, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikanth, C.V.; Vasudevan, S.; Balamurugan, P.; Selvaganapathi, R. Morphometry Characteristics Delineation and Bathymetry Mapping of Lake Dal, Kashmir valley, India using Geospatial Techniques. Res. Rev. Int. J. Multidiscip. 2018, 3, 216–220. [Google Scholar]

- Rather, I.A.; Dar, A.Q. Assessing the impact of land use and land cover dynamics on water quality of Dal Lake, NW Himalaya, India. Appl. Water Sci. 2020, 10, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T.; Gupta, G.; Sharma, A.; Kaur, B.; Alsahli, A.A.; Ahmad, P. Multivariate Statistical Approach to Study Spatiotemporal Variations in Water Quality of aHimalayan Urban Fresh Water Lake. Water 2020, 12, 2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, R.E. A trophic state index for lakes1. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1977, 22, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspers, H. OECD: Eutrophication of Waters. Monitoring, Assessment and Control.—154 pp. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development 1982. (Publié en français sous le titre »Eutrophication des Eaux. Méthodes de Surveillance, d’Evaluation et de Lutte«). Int. Rev. Gesamten Hydrobiol. Hydrogr. 1984, 69, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollenweider, R.A.; Giovanardi, F.; Montanari, G.; Rinaldi, A. Characterization of the trophic conditions of marine coastal waters with special reference to the NW Adriatic Sea: Proposal for a trophic scale, turbidity and generalized water quality index. Environmetrics 1998, 9, 329–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neverova-Dziopak, E. Surface Water Eutrophication in Poland: Assessment and Prevention. In Quality of Water Resources in Poland; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 321–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpowicz, M.; Kuczyńska-Kippen, N.; Sługocki, Ł.; Czerniawski, R.; Bogacka-Kapusta, E.; Ejsmont-Karabin, J. Trophic status index discrepancies as a tool for improving lake management: Insights from 160 Polish lakes. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 981, 179581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, S.A.; Meraj, G.; Yaseen, S.; Bhat, A.R.; Pandit, A.K. Assessing the impact of anthropogenic activities on spatio-temporal variation of water quality in Anchar lake, Kashmir Himalayas. Int. J. Environ. Sci. 2013, 3, 1625–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassiljev, A.; Blinova, I. Overview of water quality problems in Estonia with the focus on drained peat areas as a source of nitrogen. IAHS-AISH Proc. Rep. 2013, 361, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Skwierawski, A. The use of the integrated trophic state index in evaluation of the restored shallow water bodies. Ecol. Chem. Eng. 2013, 20, 1275–1283. [Google Scholar]

- Neverova-Dziopak, E.; Droździk, A. Verification of the possibility of its index application to assess the trophic state of the Dobczycki Reservoir. J. Civ. Eng. Environ. Arch. 2016, 63, 281–294. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mamoori, S.K.; Al-Maliki, L.A.; Al-Sulttani, A.H.; El-Tawil, K.; Al-Ansari, N. Statistical analysis of the best GIS interpolation method for bearing capacity estimation in An-Najaf City, Iraq. Environ. Earth Sci. 2021, 80, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.