Abstract

Alpine grasslands on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau are highly sensitive to climate change and human disturbances, and their degradation poses serious threats to ecosystem stability and soil conservation. Belowground bud banks form the foundation of vegetative regeneration, yet their variation along degradation gradients and the soil factors regulating these changes remain insufficiently understood. In this study, we investigated the density and composition of belowground buds in grasses, sedges, and forbs across four degradation levels during the peak growing season and examined the soil controls shaping these responses. The results showed that moderate degradation significantly increased total bud density, indicating enhanced clonal renewal capacity, whereas severe degradation markedly reduced bud-bank potential. Bud types from different functional groups responded differently to soil conditions: rhizome buds of grasses were mainly driven by soil fertility, while tiller buds were more sensitive to soil compaction and carbon–nitrogen availability; rhizome buds of sedges could still develop in compact, nutrient-poor soils; and bud types of forbs were more responsive to variations in soil nutrient status or soil structure. Structural equation modeling further revealed that the formation of the belowground bud is primarily influenced by soil physico-chemical properties, particularly soil nutrients, which regulate regenerative capacity under degraded alpine grasslands. This study reveals the variation patterns of belowground bud banks along degradation gradients in alpine grasslands on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau and their responses to soil factors, and it elucidates the pathways through which degradation mediates belowground bud bank dynamics via soil physico-chemical properties, particularly soil nutrients, thereby providing a scientific basis for understanding the regeneration potential of alpine grasslands and for the sustainable management and ecological restoration of degraded alpine grasslands.

1. Introduction

Alpine grasslands on the Qinghai–Tibet (QTP) Plateau are among the most climate-sensitive and ecologically fragile ecosystems in the world [1,2]. Owing to its status as the ‘Asian Water Tower’ and the ‘Third Pole,’ the QTP plays a crucial role in global climate regulation, atmospheric moisture transport, and the Asian monsoon system [3,4]. As the world’s largest high-elevation ecological unit, environmental changes on the QTP are considered to exert profound influences on climate processes across East Asia, Central Asia, and even the mid-latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere [5,6], highlighting its importance for both regional and global environmental stability. In recent decades, alpine grasslands have undergone increasing degradation driven by long-term overgrazing, global warming, reduced precipitation, and intensified human activities [7], manifested as accelerated soil erosion, declines in vegetation cover and productivity, loss of biodiversity, and weakened ecosystem services [8,9]. As the most important ecological barrier and water-conservation zone of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau, alpine grasslands play an irreplaceable role in maintaining regional soil and water retention, regulating climate, and supporting pastoral production [4,10]. Their continued degradation therefore poses severe threats to ecosystem stability and land productivity. Thus, understanding how grasslands maintain community renewal through clonal reproduction under degradation pressures is essential for elucidating their recovery mechanisms and guiding the restoration of degraded alpine grasslands.

Vegetation regenerative capacity is fundamental to the recovery and long-term persistence of degraded alpine grasslands. The belowground bud bank, composed of tiller buds, rhizome buds, and root-sprouting buds, serves as the principal regenerative reserve that enables perennial plants to withstand disturbances, maintain populations, and rapidly reoccupy space [11]. In alpine ecosystems, seed germination and seedling establishment are often constrained by low temperatures, a thick sod layer, intense interspecific competition, and short growing seasons [12,13]. In contrast, the formation and maintenance of bud banks require relatively low resource investment and offer high survival probabilities [14]. Consequently, clonal reproduction serves as the dominant pathway for community regeneration in these systems [15,16,17]. Previous studies have shown that moderate disturbance can enhance compensatory tillering and thereby promote plant regenerative capacity [18,19,20]. Under severe degradation, however, deteriorated soil moisture and nutrient conditions [21] and increased mortality of dominant parental plants [22] weaken the regenerative potential of bud banks. Nevertheless, research on how belowground bud-bank abundance changes along degradation gradients remains very limited.

All types of belowground buds originate from meristems located on buried rhizomes, stem bases, or basal nodes [23], and their formation and survival occur directly within the soil environment. Existing research on soil controls of belowground bud banks has mostly focused on single soil dimensions. For example, nitrogen or phosphorus addition alone can stimulate the formation of tiller and rhizome buds in Poa pratensis [24], whereas nutrient deficiency or oversupply generally suppresses bud-bank replenishment and renewal [22]. Drought markedly reduces belowground buds in grasslands [25,26], and soil moisture in the Zoige alpine meadow is positively correlated with the densities of short-rhizome buds and tiller buds [27]. Soil physical properties also influence bud formation. Increased soil compaction suppresses root proliferation [28] and reduces the formation of tiller in grasses [29]. Reduced soil aeration limits oxygen diffusion and decreases root and bud survival in oats [30]. Salt stress also commonly reduces tiller production and rhizome growth in oats [31]. Previous studies further indicate that precipitation is the principal driver of bud bank dynamics in alpine grasslands, whereas soil nutrients dominate regulation in temperate grasslands [32]. However, it remains unclear whether and how different plant functional groups exhibit differentiated responses to these multidimensional soil factors. Plant functional groups often display distinct sensitivities to soil conditions due to differences in clonal growth strategies and physiological traits. Most clonal grasses possess strong rhizomatous expansion capacity and respond sensitively to increases in soil fertility [33,34]. Many sedge species develop well-formed aerenchyma and highly penetrative root systems [35,36]. For example, Carex humilis produces new peripheral ramets through rhizome-derived buds, while older central ramets gradually senesce, forming an outward-expanding ring-like clonal structure that allows population renewal and spatial expansion even in dense soils [37]. Forbs generally exhibit high functional trait plasticity. Under nutrient-poor or resource-limited conditions, they tend to increase allocation to belowground storage organs to maintain survival, whereas in nutrient-rich soils they accelerate population expansion through enhanced tillering [38]. Nevertheless, few studies have systematically examined how the bud banks of different functional groups diverge in their responses to integrated soil factors.

Although soil factors are known to be closely associated with bud bank dynamics, they are hierarchically coupled within soil systems. Soil physical properties influence microbial activity and decomposition processes [39]. Microbial biomass determines the potential for organic matter breakdown [40], and soil enzyme activities regulate nutrient release efficiency [41]. This suggests that bud bank formation may be jointly driven by the direct effects of soil fertility and the indirect effects of soil physical structure mediated through microbial and enzymatic pathways. However, few studies have been able to integrate the multi-level soil factors and their associated processes influencing belowground buds. Therefore, we proposed three hypotheses in this study: (1) Moderate degradation enhances belowground bud bank accumulation through compensatory clonal responses, whereas severe degradation suppresses bud renewal; (2) Different functional groups exhibit divergent response patterns of their belowground bud types to soil nutrient availability and soil physical conditions; and (3) the formation of the belowground bud is primarily influenced by soil physico-chemical properties, particularly soil nutrients. This study investigates the response mechanisms of belowground buds in different plant functional groups of alpine grasslands to soil factors, providing scientific insights into the relationship between plant potential productivity and soil, and offering important theoretical support for the development of effective restoration strategies and ecological recovery in degraded alpine grasslands.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Sampling Sites

The study was conducted in Tuohua Village, Haiyan County, Haibei Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Qinghai Province, China (37°17′56″ N, 100°45′15″ E), at an average elevation of 3206 m. The research area covers approximately 15 hm2. The region is characterized by a typical plateau continental monsoon climate without an absolutely frost-free period. The mean annual air temperature is 1.4 °C, with average temperatures of −24.8 °C during the non-growing season and 12.5 °C during the growing season. The average annual precipitation is 425 mm [42,43]. The soil type in the study area is classified as Gelic Cambisol [44]. The vegetation is classified as typical alpine meadow. Grasses are mainly composed of Stipa purpurea, Poa pratensis, and Elymus nutans; sedges are dominated by Kobresia humilis and Carex moorcroftii; and forbs primarily include Potentilla bifurca, and Potentilla multifida.

According to the national standard “Classification Criteria for Degradation, Desertification and Salinization of Natural Grasslands” (GB 19377–2003) [45] and the Qinghai provincial standard “Classification of Alpine Grassland Degradation” (DB63/T 981–2011) [46], the rangelands in Tuohua Village were classified into four degradation levels: non-degraded (ND), lightly degraded (LD), moderately degraded (MD), and severely degraded (SD) (Table 1). Within each degradation level, the sampling plots have been fenced for more than 5 years. Grazing impacts can be effectively alleviated after more than four years of fencing [47]. The plots were selected with spatial independence, and the distance between plots was maintained at over 3 km to avoid interference from microtopography, soil conditions, and climatic factors. To minimize human disturbance, all plots had been fenced prior to sampling.

Table 1.

Detailed information on sampling sites across different degradation levels in alpine grasslands.

2.2. Sampling and Identification of Belowground Buds

The growing season is a critical period during which belowground buds are actively formed and renewed [14]. In this study, field sampling was conducted in August 2024, corresponding to the peak growing season, across four degradation levels: non-degraded (ND), lightly degraded (LD), moderately degraded (MD), and severely degraded (SD). Seven independent plots were randomly selected at each degradation level, with a minimum distance of 15 m between plots. Within each plot, a 0.5 m × 0.5 m quadrat was randomly set up to investigate vegetation characteristics. Plant height and coverage in each quadrat were recorded, and aboveground biomass (AGB) was clipped at ground level, oven-dried at 65 °C to constant weight. Following vegetation surveys, belowground bud bank samples were collected adjacent to each vegetation quadrat. The sampling and identification of belowground buds followed standardized methods outlined in previous studies [23,48], with seven soil monoliths sampled in each plot, each measuring 25 cm × 25 cm in area and 20 cm in depth. The monoliths, including aboveground plant parts, were transported to the laboratory, where the soil was gently washed away to separate plant roots and buds. Bud types were identified according to their position of origin [23], and bud densities for different functional groups were subsequently calculated.

2.3. Soil Sampling and Soil Property Measurements

After the bud bank sampling, soil sampling for soil property measurements followed standardized methods described in previous studies conducted on the Tibetan Plateau [44,48]. Specifically, three soil cores (0–20 cm) were randomly collected within each vegetation quadrat using a soil auger (7 cm diameter) and combined into a composite sample. Each soil variable was measured with seven replicates. Soil bulk density (BD) and soil moisture (SM) were determined using the cutting-ring and oven-drying methods. Undisturbed soil samples were collected from the 0–20 cm depth using a 100 cm3 cutting ring and oven-dried at 105 °C to a constant weight to calculate BD, while SM was calculated based on the difference between fresh and oven-dried soil mass.

A portion of each composite soil sample was stored at 4 °C in insulated containers and transported to the laboratory for the determination of soil enzyme activities. Urease activity was determined using the phenol–sodium hypochlorite colorimetric method; sucrase activity using the DNS colorimetric method; catalase (CAT) activity using KMnO4 titration; and alkaline phosphatase (AKP) activity using the pNPP colorimetric method [49]. All enzyme measurements were performed in triplicate to ensure analytical accuracy.

The remaining soil samples were air-dried and sieved through a 2 mm mesh for physicochemical analyses. Soil pH and electrical conductivity (EC) were measured in a 1:2.5 soil-to-water suspension. Soil organic carbon (SOC), total nitrogen (TN), available nitrogen (AN), total phosphorus (TP), available phosphorus (AP), total carbon (TC), and available potassium (AK) were quantified using the potassium dichromate oxidation method, Kjeldahl digestion, alkaline hydrolysis diffusion, acid digestion–molybdenum antimony colorimetry, high-temperature dry combustion, Olsen extraction, sodium hydroxide fusion, and ammonium acetate extraction, respectively [50,51]. Microbial biomass carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus (MBC, MBN, MBP) were determined using the chloroform fumigation–extraction method [52,53].

2.4. Data Analysis

Prior to analysis, belowground bud density was tested for normality (Shapiro–Wilk) and homogeneity of variance (Levene’s), with transformations applied when necessary. Differences in bud density among degradation levels (ND, LD, MD, SD) for grasses, sedges, and forbs were examined using one-way ANOVA, followed by Duncan’s multiple range test (p < 0.05) in SPSS 27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Boxplots and significance annotations were produced in Origin 2023 (OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA, USA). Mantal tests were performed in R using linkET to assess bud–environment associations. Redundancy analysis (RDA) was conducted using vegan, with visualization via ggplot2. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was built using piecewiseSEM to quantify direct and indirect soil effects on bud density. All R analyses were performed in R 4.5.2 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria), with significance set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Changes in Belowground Bud Density Under Different Degradation Levels

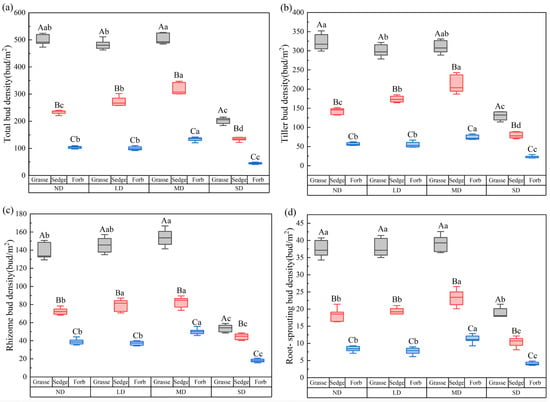

Different degradation levels significantly affected the belowground bud density of the three functional groups (p < 0.05; Figure 1). The total bud density of all functional groups peaked under MD, whereas the lowest values were observed under SD, which were significantly lower than those at the other degradation levels (p < 0.05; Figure 1a). The variation in tiller bud density closely mirrored that of total bud density across all three functional groups (p < 0.05; Figure 1a,b). Rhizome bud density in grasses peaked under MD and was significantly higher than at all other degradation levels (p < 0.05; Figure 1c). For sedges and forbs, the densities of tiller buds, rhizome buds, and root-sprouting bud all reached their highest values under MD, while no significant differences were observed between ND and LD (p< 0.05; Figure 1b–d).

Figure 1.

Variations in belowground bud density across degradation gradients for three plant functional groups. Uppercase letters indicate significant differences among functional groups within the same degradation level (p < 0.05), whereas lowercase letters indicate significant differences among degradation levels within the same functional group (p < 0.05). ND: non-degraded; LD: lightly degraded; MD: moderately degraded; SD: severely degraded. (a) Variations in total belowground bud density across degradation gradients for three plant functional groups; (b) Variations in tiller bud density across degradation gradients for three plant functional groups; (c) Variations in rhizome bud density across degradation gradients for three plant functional groups; (d) Variations in root-sprouting bud density across degradation gradients for three plant functional groups.

3.2. Differential Responses of Belowground Buds to Soil Factors

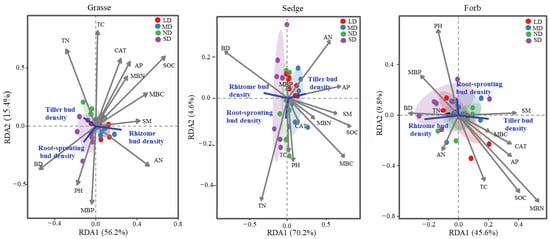

The redundancy analysis (RDA) revealed distinct and directionally differentiated relationships between belowground bud types and soil factors across functional groups (Figure 2). In the grass functional group, rhizome bud density was positively correlated with SOC, AP, AN, TC, MBC, MBN, MBP, CAT, and SM. Tiller bud density showed positive associations with TN, BD, and TC, while root-sprouting bud density was mainly influenced positively by BD, pH, and MBP. In sedges, tiller bud density was positively associated with AN, AP, SOC, MBC, MBN, CAT, and SM. Rhizome bud density was positively related to BD but negatively correlated with AN, AP, SOC, MBC, MBN, CAT, and SM, while root-sprouting bud density showed positive relationships with TC, pH, TN, CAT, MBC, MBN, SOC, and SM. For forbs, tiller bud density was positively correlated with SOC, AP, CAT, MBC, MBN, SM, and TC; rhizome bud density was positively related to BD, TN, AN, and MBP; and root-sprouting bud density was positively associated with pH, MBP, and SM.

Figure 2.

RDA-based relationships between tiller, rhizome, and root-sprouting bud densities and soil environmental variables across degradation gradients for the three plant functional groups. SOC: soil organic carbon, TC: total carbon, TN: total nitrogen, AP: available phosphorus, AN: available nitrogen, SM: soil moisture, BD: soil bulk density, pH, MBC: microbial biomass carbon, MBN: microbial biomass nitrogen, MBP: microbial biomass phosphorus, CAT: catalase activity. Colored points denote sampling plots under four degradation levels (ND, LD, MD, SD), and ellipses represent the 95% confidence intervals for each level.

3.3. Key Soil Drivers Shaping Belowground Bud Assemblages Across Functional Groups

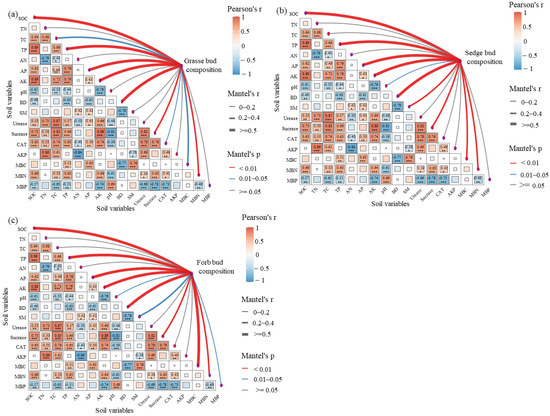

Mantel tests revealed significant and functionally differentiated positive correlations between belowground bud composition and soil variables across the three functional groups (Figure 3). For grasses, belowground bud composition showed highly significant positive correlations with SOC, TP, AP, AK, BD, Sucrase, and MBN (p < 0.01), together with significant positive correlations with TC, CAT, and MBC (0.01 ≤ p < 0.05; Figure 3a). In sedges, belowground bud composition exhibited highly significant positive correlations with SOC, TP, AP, AK, BD, Sucrase, MBN, and MBC (p < 0.01), as well as a significant positive correlation with pH (0.01 ≤ p < 0.05; Figure 3b). Forbs were primarily driven by SOC, TP, AP, AK, BD, Sucrase, MBN, and MBC (p < 0.01), while pH, SM, and MBP also showed significant positive correlations (0.01 ≤ p < 0.05; Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

Mental analysis identifies key soil factors governing the formation of underground buds in various functional groups. Grasse bud composition includes grass tiller bud density, rhizome bud density, and root-sprouting bud density. Sedge bud composition includes sedge tiller bud density, rhizome bud density, and root-sprouting bud density. Forb bud composition includes tiller bud density, rhizome bud density, and root-sprouting bud density of other herbaceous plants. Significance levels are applied (*** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05). TP: total phosphorus, AK: Available Potassium, Urease: Urease Activity, Sucrase: Sucrase Activity, AKP: Alkaline Phosphatase Activity. Other soil variables are defined as in Figure 2. (a) Mantel analysis between soil factors and grasse forb bud composition; (b) Mantel analysis between soil factors and sedge bud composition; (c) Mantel analysis between soil factors and forb bud composition.

3.4. Mechanistic Pathways Through Which Soil Factors Shape Belowground Bud Formation

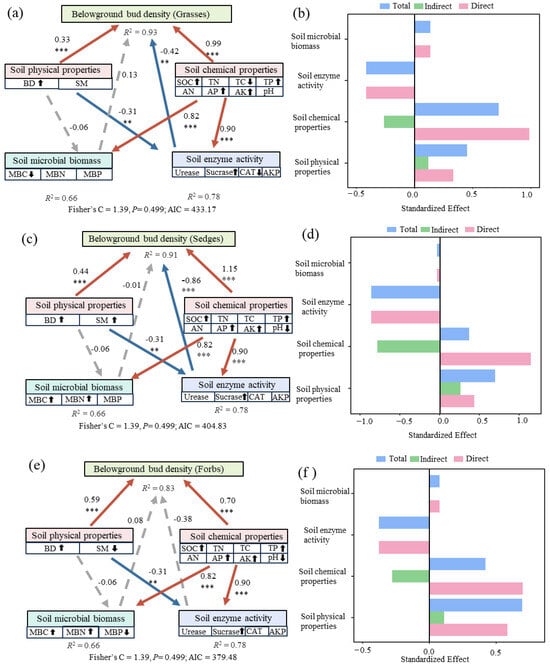

The structural equation models explained 93% of the variation in belowground bud density for grasses, 91% for sedges, and 83% for forbs (Figure 4). Soil chemical properties, particularly soil fertility, were the strongest direct positive drivers across all functional groups, with standardized path coefficients of 0.99 (grasses), 1.15 (sedges), and 0.70 (forbs), all of which were highly significant. Soil microbial biomass had no significant effect on belowground bud density in grasses and forbs. Soil enzyme activity exhibited a negative effect on grasses and sedges bud density. Soil physical properties had a significant positive effect on belowground bud density in grasses, sedges, and other forbs.

Figure 4.

Structural equation models (SEM) illustrating the effects of soil factors on belowground bud density across three plant functional groups. *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01. (a) Grasses, (c) Sedges, and (e) Forbs. Red solid arrows indicate significant positive effects, blue solid arrows indicate significant negative effects, and grey dashed arrows represent nonsignificant paths; R2 denotes the explained variance of each endogenous variable. Panels (b,d,f) show the standardized direct (pink), indirect (green), and total (blue) effects of soil factors on belowground bud density for grasses, sedges, and forbs, respectively. Soil physical properties: BD, SM; Soil chemical properties: SOC, TC, TN, TP, AN, AP, AK, pH; microbial biomass: MBC, MBN, MBP; soil enzyme activity: CAT, Urease, Sucrase, AKP. The arrows “↑” and “↓” represent the positive and negative correlations between the corresponding soil factors and belowground buds, respectively, and these correlations were identified through Mantel analysis.

4. Discussions

4.1. Moderate Degradation Promoted Bud Renewal, Whereas Severe Degradation Caused Functional Collapse

Our results indicate that the total bud density of the three functional groups peaked at the moderately degraded (MD) stage and its lowest value under severe degradation (SD). This indicates that moderate disturbance can stimulate compensatory tillering and vegetative reproduction [54], consistent with previous findings that moderate grazing intensity promotes the belowground bud density of perennial herbaceous plants [55]. These findings support our first hypothesis that moderate degradation enhances bud bank accumulation through compensatory clonal responses, whereas severe degradation suppresses. As degradation intensifies, soil nutrient availability and moisture decline [56], and nutrient limitation triggers a redistribution of plant resources. Due to their high energetic demands, apical meristems are preferentially suppressed, whereas belowground buds and rhizomes receive more carbon and nutrients to maintain regenerative potential [14,57]. Drought and nutrient deficiency also reduce auxin transport from apical buds while increasing cytokinin levels in roots, thereby weakening apical dominance and promoting the activation of lateral buds and basal dormant buds [58,59]. These responses collectively enhance clonal renewal capacity under stress, leading to stronger activation and accumulation of the belowground bud bank under moderate stress during the peak growing season. Since the size of the bud bank strongly depends on the number of surviving parent individuals, extensive mortality of adult plants in severely degraded (SD) grasslands [60] results in a sharp decline in total bud density [61]. Meanwhile, severe degradation is often accompanied by pronounced reductions in soil moisture and nutrients, causing soils to become dry, compacted, and infertile [62]. Such adverse conditions slow bud formation and markedly increase bud mortality [63]. Therefore, moderate degradation promotes bud renewal, whereas severe degradation leads to functional collapse during the peak vegetation growth period.

In conclusion, under moderate degradation conditions, moderate disturbance promotes compensatory growth in plants, which facilitates the formation and accumulation of underground buds, thereby enhancing the regenerative capacity of grasslands. In contrast, in severely degraded grasslands, a significant reduction in underground bud density leads to a marked decline in its function as a source of grassland productivity, thus weakening the stability of the grassland community. Therefore, maintaining a moderate level of disturbance is crucial for preserving the regenerative potential of grasslands. These findings provide a scientific basis for improving the ecological restoration capacity and productivity of degraded grasslands.

4.2. Functional Divergence in Belowground Bud Responses to Soil Environmental Factors

The results showed that, in grasses, rhizome buds were oriented in the same direction as SOC, AN, AP, TC, MBC, MBN, MBP, CAT, and SM in the RDA ordination space, indicating a strong positive association between these fertility-related factors and rhizome bud density. Rhizome buds originate from nodes on belowground rhizomes [13], and perennial rhizomatous grasses typically store substantial amounts of photosynthates and nutrients in rhizomes to support regeneration and sustained horizontal expansion [64,65]. Moreover, high soil organic carbon and microbial biomass enhance nutrient turnover, which facilitates rhizome development and lateral elongation [66]. Tiller buds were mainly positively correlated with TN, BD, and TC, indicating that their formation is more sensitive to soil C–N availability and soil physical conditions. Because tiller buds occur at the plant base, reduced soil aeration and increased compaction can inhibit their formation and emergence [67]. Although nutrient limitations, particularly nitrogen deficiency, generally suppress tillering [68], the response is not linear: moderate nitrogen enrichment can increase tiller number and improve stand structure, whereas excessive nitrogen input can suppress tiller initiation [69]. Nutrients act as one of the regulatory factors affecting tillering, while the formation of tiller buds is fundamentally governed by light cues, apical dominance, and hormonal regulation [65]. Therefore, rhizome buds in grasses are more dependent on fertility-related factors, whereas tiller buds are more strongly constrained by soil compaction and C–N supply rather than high nutrient input alone. Mantel analysis further revealed strong positive correlations between overall grass bud composition and SOC, TP, AP, AK, BD, Sucrase, and MBN (p < 0.01), indicating that both fertility-related factors and soil structural attributes are key drivers of bud bank construction. This is consistent with the RDA results showing that rhizome buds align with nutrient gradients, while tiller buds correspond to soil physical structure, highlighting that grass bud banks exhibit greater regenerative potential under fertile and well-aerated soil conditions.

In sedges, tiller bud density was positively correlated with fertility-related factors such as AN, AP, SOC, MBC, MBN, CAT, and SM, whereas rhizome buds showed negative correlations with SOC, AN, AP, MBC, CAT, and SM, but a positive correlation with BD. This indicates that rhizome buds of sedges can persist well under more compact, relatively low fertility, and drier soil conditions. This may be attributed to increased soil compaction and reduced aeration under severe degradation [70], which lead to shorter rhizomes and lower nutrient requirements in plants [67]. Meanwhile, sedge species generally exhibit low growth rates, low tissue construction costs, and high individual survival capacity, representing typical stress-tolerant (S-strategy) groups [71]. Mantel analysis further revealed that the overall bud composition of sedges was strongly and positively correlated with SOC, TP, AP, AK, BD, Sucrase, MBN, and MBC (p < 0.01), indicating that although different bud types respond differently to soil conditions, both fertility-dfactors and soil structural attributes jointly determine the formation of sedge bud banks, rather than a single factor acting alone.

For forbs, tiller buds were positively correlated with SOC, AP, CAT, MBC, MBN, SM, and TC, whereas rhizome buds were regulated by BD, TN, AN, and MBP. These two bud types differ in their sensitivity dimensions to soil factors: tiller buds respond more strongly to variations in soil nutrient availability, moisture, and microbial activity, while rhizome buds are more sensitive to soil structural constraints and locally available nutrients. This differentiated response pattern indicates that the bud bank of forbs does not rely solely on high fertility soils [38] but can sustain renewal capacity under diverse soil conditions. Many forb species possess high functional trait plasticity by adjusting biomass allocation and regenerative structures [72]. Mantel analysis further revealed that their overall bud composition was jointly driven by multiple factors (including SOC, TP, AP, AK, BD, Sucrase, MBN, and MBC), consistent with the RDA results showing that tiller buds align with fertility-related factors, whereas rhizome buds respond to both soil structure and selected nutrient elements. These findings suggest that forb bud banks are capable of responding to changes in soil fertility while also adapting to variations in soil structure and compaction, enabling them to maintain strong regenerative and expansion capacity under heterogeneous soil conditions in degraded grasslands.

In summary, rhizome buds of grasses were more dependent on fertility-related factors, those of sedges persisted better under compact and low-fertility soils, and forbs showed complementary responses along fertility and structural dimensions. These patterns of functional differentiation support our second hypothesis that belowground bud types of different functional groups exhibit distinct response modes to soil nutrient availability and soil physical conditions under peak-season conditions.

4.3. Soil Physico-Chemical Properties Directly Affect Belowground Bud Formation

The structural equation model (SEM) in this study showed that Soil chemical properties, particularly soil fertility, were the primary direct drivers of belowground bud density across all three functional groups, with standardized path coefficients reaching highly significant levels in grasses (0.99), sedges (1.15), and forbs (0.70). This result is consistent with the preceding RDA and Mantel analyses, indicating that regardless of functional group identity, soil fertility remains the fundamental limiting factor determining bud bank size, which aligns with the high demand of rhizome based clonal structures for carbon assimilation and nutrient supply [38,61]. Under conditions of nutrient decline caused by degradation, plants increasingly rely on allocating limited resources to survival and regenerative structures [73]. Sedges exhibited the highest chemical-related path coefficient in the SEM (1.15), particularly with soil nutrients driving the formation of sedge belowground buds, suggesting that their overall bud bank size is strongly dependent on nutrient inputs. Although the RDA showed that rhizome buds of sedges tend to be maintained under low-fertility and highly compact soil conditions, while tiller buds increase markedly with improvements in nitrogen and phosphorus availability, sedges, despite being typical S-strategy species [71], still rely on basic nutrient supply for long-term persistence and reproduction.

The soil physical properties have a significant positive driving effect on belowground bud formation, with standardized path coefficients reaching highly significant levels in grasses (0.33), sedges (0.44), and forbs (0.59). Soil bulk density (BD) is the primary factor driving the formation of belowground buds. This phenomenon may be related to the frequent seasonal freeze–thaw cycles in alpine grassland soils, which affect the distribution of water and nutrients in the soil [74,75]. When soil bulk density (BD) is higher, it indicates a more compact soil with lower porosity. During the freeze–thaw process in alpine grasslands, water freezes and is retained in the soil, and when it thaws, the water does not rapidly carry nutrients away. Water and the nutrients dissolved within it remain in the soil for a longer time, reducing excessive loss of water and nutrients, thereby providing a more stable growth environment for belowground buds [76]. On the other hand, belowground buds serve as an important survival strategy for grassland plants to cope with adverse environments [14]. Soil compaction limits root growth and affects aboveground growth. Plants compensate for root growth limitations by proliferating belowground buds, thereby maintaining the survival and expansion of aboveground populations. For example, as sand burial depth increases, plants such as Psammochloa villosa and Phragmites australis show an increase in the number of belowground buds [77]. This indicates that they respond to soil compaction and environmental changes through the proliferation of belowground buds.

In summary, this study reveals the crucial role of soil physicochemical properties, particularly soil fertility, in the formation of underground buds, supporting our third hypothesis that belowground bud formation is jointly regulated by soil physico-chemical properties, especially soil nutrients. The results indicate that soil fertility in alpine grasslands is a key factor limiting bud bank size. This finding provides a scientific basis for grassland restoration and management, emphasizing the potential to enhance grassland productivity and ecological resilience by regulating soil fertility factors to promote the formation of underground bud banks.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that belowground bud density peaks at the moderately degraded stage and declines sharply under severe degradation, indicating that moderate disturbance can stimulate clonal regeneration in alpine grasslands, whereas excessive degradation weakens bud bank renewal capacity. Different plant functional groups exhibited differences in their bud responses to soil factors. In grasses, rhizome buds were primarily driven by soil fertility, whereas tiller buds were more strongly affected by soil compaction and C–N availability. Rhizome buds of sedges were able to persist in compact and low-fertility soils, while the various bud types of forbs were more sensitive to changes in soil nutrients or structure. The SEM showed that the formation of the belowground bud is primarily influenced by soil physico-chemical properties, particularly soil nutrients. This study elucidates the response characteristics and soil-driven mechanisms of belowground bud banks along degradation gradients during the peak growing season, providing important insights for understanding degradation and recovery processes in alpine grasslands.

Author Contributions

K.H.: Writing—original draft, Software, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation; Q.Z.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—review and editing; H.D.: Investigation; X.W. (Xiaoli Wang): Investigation; L.H.: Investigation; X.W. (Xiaoxing Wei): Supervision, Validation, Funding acquisition, Project administration; J.L.: Formal analysis; Q.W.: Validation, Writing—review and editing; J.W.: Formal analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Natural Science Foundation of Qinghai Province (Grant No. 2023-ZJ-942J); Qinghai Province Kunlun Talent Program (Grant No. 2024-LJ87).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Grasses used in the study are mainly composed of Stipa purpurea, Poa pratensis, and Elymus nutans; sedges in the study are dominated by Kobresia humilis and Carex moorcroftii; and forbs in the study primarily include Potentilla bifurca, and Potentilla multifida. Our study does not involve any genetically modified materials or model plant species. All plant materials used in this research are naturally occurring wild species collected from alpine grasslands in Qinghai Province, China. Accordingly, there are no cell lines, no deposited genetic materials, and no accession numbers associated with this study. The plant materials were not obtained from any company, institute, or individual, but were sampled in situ from natural grassland ecosystems following standard ecological field survey protocols.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available upon request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Wu, R.; Hu, G.; Ganjurjav, H.; Gao, Q. Sensitivity of Grassland Coverage to Climate across Environmental Gradients on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Chen, Y.; Xiong, J.; Ye, C.; Yong, Z.; Wang, Y.; He, D.; Xu, S. Relationships between Climate Change, Phenology, Edaphic Factors, and Net Primary Productivity across the Tibetan Plateau. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 107, 102708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, P.F.; Salles, T.; Zahirovic, S.; Müller, R.D. A Glimpse into a Possible Geomorphic Future of Tibet. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 613–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immerzeel, W.W.; Lutz, A.F.; Andrade, M.; Bahl, A.; Biemans, H.; Bolch, T.; Hyde, S.; Brumby, S.; Davies, B.J.; Elmore, A.C.; et al. Importance and Vulnerability of the World’s Water Towers. Nature 2020, 577, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Koo, M.S.; Ardilouze, C.; Saha, S.K.; Mechoso, C.R.; Nobre, P.; Nayak, H.P.; Senan, R.; Takaya, Y.; Bottino, M.J. Spring Surface and Subsurface Temperature Anomalies over the Tibetan Plateau and Their Teleconnection to the Northern Hemisphere Circulation. Clim. Dyn. 2024, 62, 2907–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.P.; Zhou, X.J.; Wu, G.X.; Xu, X.D.; Zhao, Q.Y.; Liu, Y.L.; Duan, A.M.; Xie, Y.K.; Ma, Y.M.; Zhao, P.; et al. Global Climate Impacts of Land-Surface and Atmospheric Processes Over the Tibetan Plateau. Rev. Geophys. 2023, 61, e2022RG000771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, Q.; Zou, F. Spatio-Temporal Changes of Vegetation Net Primary Productivity and Its Driving Factors on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau from 2001 to 2017. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhai, L.; Sang, H.; Cheng, S.; Li, H. Effects of Hydrothermal Factors and Human Activities on the Vegetation Coverage of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Shang, Z.; Gao, J.; Boone, R.B. Enhancing Sustainability of Grassland Ecosystems through Ecological Restoration and Grazing Management in an Era of Climate Change on the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 287, 106684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergola, M.; De Falco, E.; Cerrato, M. Grassland Ecosystem Services: Their Economic Evaluation through a Systematic Review. Land 2024, 13, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimešová, J.; Martínková, J.; Bartušková, A.; Ott, J.P. Belowground plant traits and their ecosystem functions along aridity gradients in grasslands. Plant Soil 2023, 487, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.P.; Wu, G.L.; Shi, Z.H. Post-fire species recruitment in a semiarid perennial steppe on the Loess Plateau. Aust. J. Bot. 2013, 61, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, J.; Venn, S.E. Climate change may alter seed and seedling traits and shift germination and mortality patterns in alpine environments. Ann. Bot. 2025, 136, 651–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ott, J.P.; Klimešová, J.; Hartnett, D.C. The ecology and significance of below-ground bud banks in plants. Ann. Bot. 2019, 123, 1099–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vítová, A.; Macek, P.; Leps, J. Disentangling the interplay of generative and vegetative propagation among different functional groups during gap colonization in meadows. Funct. Ecol. 2017, 31, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, E.; Hartnett, D.C. The role of seed and vegetative reproduction in plant recruitment and demography in tallgrass prairie. Plant Ecol. 2006, 187, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körner, C. Concepts in Alpine Plant Ecology. Plants 2023, 12, 2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulbright, T.E.; Ortega-Santos, J.A.; Hines, S.L.; Drabek, D.J.; Saenz, R., III; Campbell, T.A.; Hewitt, D.G.; Wester, D.B. Relationships between plant species richness and grazing intensity in a semiarid ecosystem. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 13, e10668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, P.J.; Lawes, M.J.; Murphy, B.P.; Russell-Smith, J.; Nano, C.E.; Bradstock, R.; Enright, N.J.; Fontaine, J.B.; Gosper, C.R.; Radford, I.; et al. A synthesis of post-fire recovery traits of woody plants in Australian ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 534, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herben, T.; Klimešová, J.; Chytrý, M. Effects of disturbance frequency and severity on plant traits: An assessment across a temperate flora. Funct. Ecol. 2018, 32, 799–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbdelRahman, M.A.E. An overview of land degradation, desertification and sustainable land management using GIS and remote sensing applications. Rend. Fis. Acc. Lincei. 2023, 34, 767–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Duan, N.; Liu, C.; Li, H.; Xu, L. Allometry of bud dynamic pattern and linkage between bud traits and ecological stoichiometry of Nitraria tangutorum under fertilizer addition. PeerJ. 2023, 11, e14934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klimešová, J.; Klimeš, L. Bud banks and their role in vegetative regeneration—A literature review and proposal for simple classification and assessment. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2007, 8, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L. Effects of Nitrogen and Phosphorus Addition on Biomass and Underground Buds of Artificial Grassland of Poa pratensis L. var. anceps Gaud. cv. Qinghai. Master’s Thesis, Qinghai University, Xining, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, J.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, Y.; Ma, Q.; Yu, Q.; Zhu, J.; Zuo, X.; Broderick, C.M.; Collins, S.L.; Han, X.; et al. Responses of bud banks and shoot density to experimental drought along an aridity gradient in temperate grasslands. Funct. Ecol. 2023, 37, 1211–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Hou, X.Z.; Zhu, J.L.; Miao, R.H.; Adomako, M.O. Nitrogen addition and drought impose divergent effects on belowground bud banks of grassland community: A meta-analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 15, 1464973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, X.; Su, P.; Zhou, Z.; Shi, R. Belowground Bud Bank Distribution and Aboveground Community Characteristics along Different Moisture Gradients of Alpine Meadow in the Zoige Plateau, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogorek, L.L.; Gao, Y.; Farrar, E.; Pandey, B.K. Soil compaction sensing mechanisms and root responses. Trends Plant Sci. 2025, 30, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhandiram, N.P.K.; Humphreys, M.W.; Fychan, R.; Davies, J.W.; Sanderson, R.; Marley, C.L. Do agricultural grasses bred for improved root systems provide resilience to machinery-derived soil compaction? Food Energy Secur. 2020, 9, e227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arduini, I.; Baldanzi, M.; Pampana, S. Reduced growth and nitrogen uptake during waterlogging at tillering permanently affect yield components in late sown oats. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.W.; Peiliang, S.; Cui, Y.H.; Hanif, A.; Yang, Z.-Z.; Li, R.-L.; Mu, C.-S.; Rasheed, A. Physiological responses and adoptive mechanisms in oat against three levels of salt stress. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2023, 51, 13249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, N.; Liu, Z.; Yang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Xiao, D. Contrasting Belowground Bud Banks and Their Driving Factors between Alpine and Temperate Grasslands in China. Global Ecol. Conserv. 2024, 54, e03070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilts, J.A.; Mittelbach, G.G.; Reynolds, H.L.; Gross, K.L. Resource heterogeneity, soil fertility, and species diversity: Effects of clonal species on plant communities. Am. Nat. 2011, 177, 574–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.-F.; Wang, C.-L.; Fang, T.; Shao, F.-F.; Chen, Y.-H.; Wang, R.; Huang, W.-J.; Luo, F.-L.; Zhu, Y.-J. Clonal plants display a guerrilla architecture and acquisitive strategy in high-moisture areas of marsh wetlands in northern China. J. Plant Ecol. 2025, 18, rtaf078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, E.J.W.; Colmer, T.D.; Blom, C.; Voesenek, L.A.C.J. Changes in growth, porosity, and radial oxygen loss from adventitious roots of selected mono- and dicotyledonous wetland species with contrasting types of aerenchyma. Plant Cell Environ. 2000, 23, 1237–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, M.; Korresnalo, A.; Laiho, R.; Lohila, A.; Makiranta, P.; Pihlatie, M.; Tuittila, E.-S.; Kohl, L.; Putkinen, A.; Koskinen, M. Plant phenology and species-specific traits control plant CH4 emissions in a northern boreal fen. New Phytol. 2023, 238, 1019–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikberg, S.; Mucina, L. Spatial variation in vegetation and abiotic factors related to the occurrence of a ring-forming sedge. J. Veg. Sci. 2002, 13, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kleunen, M.; Fischer, M.; Schmid, B. Effects of intraspecific competition on size variation and reproductive allocation in a clonal plant. Oikos 2001, 94, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visconti Moreno, E.F.; Valenzuela Balcázar, I.G.; Agudelo Archila, D.P. Evaluation of microorganisms response to soil physical conditions under different agriculture use systems. Rev. Fac. Nac. Agron. Medellín 2024, 77, 10573–10583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Liu, K.; Ahmed, W.; Jing, H.; Qaswar, M.; Kofi Anthonio, C.; Maitlo, A.A.; Lu, Z.; Liu, L.; Zhang, H. Nitrogen mineralization, soil microbial biomass and extracellular enzyme activities regulated by long-term N fertilizer inputs: A comparison study from upland and paddy soils in a red soil region of China. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwituze, Y.; Nyiraneza, J.; Fraser, T.D.; Dessureault-Rompré, J.; Ziadi, N.; Lafond, J. Carbon, Nitrogen, Phosphorus, and Extracellular Soil Enzyme Responses to Different Land Use. Front. Soil Sci. 2022, 2, 814554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Lin, Z.; Wei, X.; Peng, C.; Yao, Z.; Han, B.; Xiao, Q.; Zhou, H.; Deng, Y.; Liu, K.; et al. Precipitation increase counteracts warming effects on plant and soil C:N:P stoichiometry in an alpine meadow. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1044173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.T.; Wang, Y.M.; Wang, X.Z.; Li, J.N.; Li, J.; Yang, D.; Guo, Z.G.; Pang, X.P. Consequences of plateau pika disturbance on plant–soil carbon and nitrogen in alpine meadows. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1362125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Z.; Zhao, X.Q.; Liu, W.T.; Feng, B.; Lv, W.; Zhang, Z.X.; Yang, X.X.; Dong, Q.M. Plant biomass partitioning in alpine meadows under different herbivores as influenced by soil bulk density and available nutrients. Catena 2024, 240, 108017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 19377–2003; Parameters for Degradation, Sandification and Salification of Rangelands. General Admin-istration of Quality Supervision. Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2003.

- DB63/T 981–2011; The Classification of Degrading Grades of Alpine Steppe. Qinghai Provincial Bureau of Quality and Technical Supervision: Xining, China, 2011.

- Zhan, T.Y.; Zhao, W.W.; Feng, S.Y.; Hua, T. Plant Community Traits Respond to Grazing Exclusion Duration in Alpine Meadow and Alpine Steppe on the Tibetan Plateau. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 863246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yu, C.; Pang, X.P.; Jin, S.H.; Zhang, J.; Guo, Z.G. The disturbance and disturbance intensity of small and semi-fossorial herbivores alter the belowground bud density of graminoids in alpine meadows. Ecol. Eng. 2018, 113, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, S.Y. Soil Enzyme and Research Method; Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Cai, Y.; Hou, F.; Jia, Z.; Bowatte, S. Sheep grazing impacts on soil methanotrophs and their activity in typical steppe in the Loess Plateau, China. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2022, 175, 104440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Hu, W.; Zhang, X.; Li, M.; Yang, Y.; Che, R. Land degradation decreased crop productivity by altering soil quality index generated by network analysis. Soil Tillage Res. 2025, 246, 106354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookes, P.C.; Landman, A.; Pruden, G.; Jenkinson, D.S. Chloroform fumigation and the release of soil nitrogen: A rapid direct extraction method to measure microbial biomass nitrogen in soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1985, 17, 837–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, E.D.; Brookes, P.C.; Jenkinson, D.S. An extraction method for measuring soil microbial biomass C. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1987, 19, 703–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Cao, Q.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Tong, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Huo, L.; Wei, K. Response of growth and reproductive traits to mowing tolerance mechanism in Elymus species. J. Plant Ecol. 2025, 18, rtaf096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Du, J.; Zhang, B.; Ba, L.; Hodgkinson, K.C. Grazing intensity and phenotypic plasticity in the clonal grass Leymus chinensis. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2017, 70, 740–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y.; Xiao, Y.M.; Wang, W.Y.; Yang, X.Y.; Zhou, G.Y. Alpine steppe degradation weakens ecosystem multifunctionality through the decline in climax dominant species on the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1650352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rog, I.; Hilman, B.; Fox, H.; Yalin, D.; Qubaja, R.; Klein, T. Increased belowground tree carbon allocation in a mature mixed forest in a dry versus a wet year. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2024, 30, e17172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bechtold, U.; Field, B. Molecular mechanisms controlling plant growth during abiotic stress. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 2753–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurepa, J.; Smalle, J.A. Auxin/Cytokinin Antagonistic Control of the Shoot/Root Growth Ratio and Its Relevance for Adaptation to Drought and Nutrient Deficiency Stresses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Bao, G.; Zhang, P.; Feng, X.; Ma, J.; Lu, H.; Shi, H.; Wei, X.; Tang, B.; Liu, K. Changes in bud bank and their correlation with plant community composition in degraded alpine meadows. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1259340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilandžija, D.; Stuparić, R.; Galić, M.; Zgorelec, Ž.; Leto, J.; Bilandžija, N. Carbon balance of Miscanthus biomass from rhizomes and seedlings. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ren, Z.; Ma, P.; Wang, Z.; Niu, D.; Fu, H.; Elser, J.J. Effects of grassland degradation on ecological stoichiometry of soil ecosystems on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 722, 137910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Huang, A.; Zhou, T.; Liu, M.; Ma, S.; Zhao, N.; Wang, X.; Sun, J. Patterns and drivers of the belowground bud bank in alpine grasslands on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1095864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Wang, W.; Zhao, W.; He, Z.; Du, J. Typical rhizomatous clonal grass Psammochloa villosa changes resource allocation during clonal expansion to fit arid sandy habitats. Ecol. Evol. 2025, 15, e72432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.H.; Liu, J.; Dong, M. Ecological Consequences of Clonal Integration in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig, J.; Paulucci, G.; Guiderdoni, E.; Gantet, P. Regulation of Shoot and Root Development through Mutual Signaling. Mol. Plant 2012, 5, 974–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, M.A.; Anderson, W.K. Soil compaction in cropping systems: A review of the nature, causes and possible solutions. Soil Tillage Res. 2005, 82, 121–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Faria Melo, C.C.; Amaral, D.S.; de Mello Prado, R.; de Moura Zanine, A.; de Jesus Ferreira, D.; Drummond, L.C.D. Silicon reduces nitrogen stress and improves growth and yield of forage grass under excessive fertilization in tropical soils. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaitzidis, A.; Kadoglidou, K.; Mylonas, I.; Ghoghoberidze, S.; Ninou, E.; Katsantonis, D. Investigating the impact of tillering on yield and yield-related traits in European rice cultivars. Agriculture 2025, 15, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xue, X.; Peng, F.; You, Q.; Hao, A. Meta-analysis of the effects of grassland degradation on plant and soil properties in the alpine meadows of the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2019, 20, e00774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Hou, G.; Sun, J.; Zong, N.; Shi, P. Degradation Shifts Plant Communities from S- to R-Strategy in an Alpine Meadow, Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 795, 149572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipowsky, A.; Roscher, C.; Schumacher, J.; Michalski, S.G.; Gubsch, M.; Buchmann, N.; Schulze, E.-D.; Schmid, B. Plasticity of functional traits of forb species in response to biodiversity. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2015, 17, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Lai, C.; Peng, F.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, W.; Song, X.; Luo, S.; Sun, J.; Chen, X.; Chen, B.; et al. Restoration of degraded alpine meadows from the perspective of plant–soil feedbacks. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2024, 60, 941–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Li, X.; Ding, M.; Shi, F.; Zuo, F.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X. Characteristics of Water Retention, Nutrient Storage, and Biomass Production Across Alpine Grassland Soils in the Qilian Mountains. Geoderma Reg. 2023, 35, e00721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; He, J.S. Warming Enhances Soil Freezing and Thawing Circles in the Non-Growing Season in a Tibetan Alpine Grassland. Food Sci. 2017, 47, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Van der Bolt, F.; Cornelis, W. Predicting Bulk Density of Soils with Varying Degree of Structural Degradation Using Single and Multi-Parameter Based Pedotransfer Functions. Soil Tillage Res. 2025, 250, 106503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.T.; Dong, Y.W.; Qian, J.Q.; Tao, J.; Li, D.M.; Xin, Z.M.; Zhang, Z.M.; Zhu, J.L. Trade-offs in the adaptation strategy of two dominant rhizomatous grasses to sand burial in arid sand dunes. Plant Ecol. 2025, 18, rtae088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.