Abstract

In this analysis, the dynamic nexus between green governance, energy transition, and carbon emissions in the period spanning 1990 and 2022 for the twenty-one member economies of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and partner economies is examined. Employing Feasible Generalized Least Squares (FGLS), Driscoll–Kraay Standard Errors (DKSE), and Quantile-on-Quantile Regression (QQR), this analysis encompasses the effects of the use of renewable energy sources, economic growth, and changes in the population on carbon emissions. Results for the analysis show that the adoption of renewable energy sources, tough environmental regulations, and green innovation play a significant role in offsetting carbon emissions since the results are more pronounced at the tail ends of the distribution of carbon emissions. Conversely, changes in the level of population and economic growth are identified as potential exacerbators of environmental concerns. In offering implications for policymakers, this analysis argues that environmental laws and taxation and green innovation are potential means of improving environmental governance in achieving the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals and climate change commitments. By addressing the issue of differential environmental effects based on varying levels of carbon emissions, this analysis makes contributions to the expanding literature on sustainable environmental governance in the twenty-first-century energy economy.

1. Introduction

emissions in the case of OECD nations have demonstrated varying relationships between the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In fact, many studies demonstrate that the SDGs can lower emission rates. In addition, findings are negative for the consumption of renewable energy sources, eco-innovation, clean energy sources, and institutional quality indexes [1]. The hypothesis of Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) confirms this statement. It describes that emission rates can be lowered in the course of augmenting levels of economic development. Still, GDP, electric power demand, and trade liberalization augment emission rates. Some prior research works demonstrate that during the period from 1960 to 1995, the OECD nations decreased their emission rates in the least-cost manner due to advancements in energy efficiency and simultaneously due to fuel switches [2]. Decomposition analysis indicates that product-related emission rates can be lowered, whereas consumption-based analysis indicates that environmental pressure in the course of emission exportation to poor nations still remains [2]. Social sustainability and technological innovation are recognized as important factors for attaining carbon neutrality [3].

The literature on renewable energy reveals its vital contributions towards fulfilling the SDGs for OECD nations. There are several instances that illustrate the benefits of renewable energy on the SDGs in a favorable manner. Renewable energy has been observed to enhance the adjusted net savings per capita in the long run and contribute towards achieving the SDGs [4]. The application of renewable energy leads to easy fulfillment of SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) and SDG 13 (Climate Action) due to the addition of the backload capacity factor to the SDGs. An energy transition in the case of OECD nations reveals their requirement to fulfill SDG 7 and SDG 13 commitments. In addition to this requirement, structural transformation leads to reductions in disparities in the efficiency of renewable energy [5]. Human capital, technological change, and energy prices are highly influential for the member nations of OECD as potential vital factors in making energy transitions sustainable. In addition to this requirement, it has been observed that wind energy, hydropower, or total renewable energy leads to decreased risks of energy security [6].

Some of the findings on economic growth include the following. Positive correlations are obtained when economic growth is correlated with investment, openness of economy, and lower inflation rates. Smaller economies of OECD nations are associated with higher growth rates [7]. Large disparities are observed in GDP per capita in different nations in the OECD. Factors influenced by GDP per capita are essentially employment growth and not labor productivity changes. Financial development is an important determinant of GDP growth, and domestic credit, market capitalization, and share turnover rates are important for GDP per capita [8]. Research and Development (R&D) and Information and Communication Technology (ICT) are the factors required in the long-term growth process and must be ensured in an integrated policymaking environment. Business R&D is associated with higher rates of economic growth, whereas government R&D is devoid of any favorable effects on GDP growth [9]. Countries that enjoy higher growth rates also share some special factors for this condition. These include increased workforce, human capital creation, and increased use of ICT. In turn, economic growth is mutually causally influential on human development indicators, leading to increased income disparities [7].

When focusing on the relation between population growth and SDGs in relation to OECD nations, certain implications arise. Upon the full implementation of the SDGs, world population growth can rapidly decrease, and the improvement in health, education, and reproductive health can lead to an expected range of 8.2–8.7 billion in 2100 [10]. Studies show that the current average annual growth in the populations of OECD nations stands at 0.6% per year. In some nations that exhibit higher immigration levels, such as in Australia, Canada, and the US, this growth rate is higher. In contrast, nations such as Germany and Hungary are experiencing decreased populations due to low birth rates. In the years to come, the growth of populations in the OECD nations would decrease to less than 0.2% in 2050. It is expected that the defining aspect of 21st-century demography will be aged populations. This is expected to be influenced mainly by falling fertility rates. In turn, this would lead to lower GDP growth, investments, and real interest rates in the OECD nations. However, certain changes can be achieved through reforms and behavior modifications [11].

Environmental policies are becoming less sector-specific and are moving towards integrated approaches that embed environmental considerations within economic choices. In the case of OECD member nations, environmental review and the polluter pays principle are considered vital in making optimal environmental policy choices based on analysis and recommendations and for accessing information [12]. Analysis indicates that the outcome of different environmental policy choices is complicated. Fiscal and R&D-based environmental policies and investments have achieved success in lowering PM2.5 emission levels, whereas economic and incentive-based environmental policies have achieved only less-than-optimal results within the current environment. There exists an EPS “dose response” relationship. Environmental Policy Stringency (EPS) lessens total carbon emissions and Ecological Footprints per capita, besides favoring solar and wind energy developments [13]. Environmental policies and changes in the energy sector are identified to lower emission levels due to environmental factors, whereas GDP and foreign investment contribute to the increased effects of climate change [14].

Green innovation is vital for environmental sustainability and economic development. Green innovation has been proven to lower emissions and contribute to better environmental conditions. In effect, this outcome is very useful when integrated into the use of clean energy and environmental taxes. However, the efficiency of carbon taxation has been somewhat inconsistent [15,16]. In evaluating the data, it can be seen that the use of energy and environmental sustainability is very important for bettering the performance of eco-innovation in the OECD [17]. Green innovation can lead to green growth. In addition, the use of clean energy, environmental innovation, and political stability are other contributors to green growth. Green financial programs are also very helpful in supporting green innovation and lower trade-adjusted emissions. Technological innovation depends on geographical areas. Transportation and manufacturing are favored in different areas, such as Oceania and Asia, respectively [18].

Countries of the OECD were selected for this analysis due to the level of their advanced economy, emissions, and the simultaneous implementation of environmental policies. In addition, the intricate nexus of economic growth and sustainable development of the OECD member nations makes them an important testing ground for this analysis. Technologically and politically, the climate change action scenarios of the member nations of the OECD act as precedents for such action in the international community at large. By juxtaposing the different facts about the determinants of emissions in relation to Renewable Energy, Institutional Quality, Economic and Population Growth, Environmental Policies, and Green Innovation, this analysis seeks to arrive at some conclusions about such action that would lead to the goal of carbon neutrality and achieving the SDGs. Though existing literature has managed to find a general relationship between renewable energy sources and emission cuts, its standard approach to the topic has tended to treat all economic states uniformly affected by the relationship. The positioning of this analysis at the margins of the existing debate is such that it directly considers the issues of heterogeneity from environmental policy outcomes and ‘nonlinearities from green innovation.’ The main marginal contributions by this study can thus be stated as follows: (1) It goes beyond averages for mean outcomes to consider variations between low-pollution states and high-pollution states by employing ‘Quantile-on-Quantile’ estimates on the topic. (2) It seeks to focus on particular ‘thresholds’ at which pure marginal gain becomes ‘substantial gain’ according to the present level of ‘carbon intensity for each nation from green innovation.’ (3) The main marginal contributions of this study would finally be to show that one-size-fits-all approaches to standard environmental taxation policies may fail in countries that lack standard institutional levels for enforcement.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Emission and Renewable Energy

Consumption of renewable energy sources has been observed to decrease emissions significantly in different nations and periods. Many studies have observed that for every 1% increment in the use of renewable energy sources, there is a decrease in emissions of around 0.5–1.25% [19]. This observation remains valid for large-scale energy-consuming nations, nations that rely on natural resources for consumption, and nations that have large carbon emissions. The use of renewable energy sources in reducing Emissions are reinforced when accountability increases. The literature confirms that the Environmental Kuznets Curve can be described in relation to the inverted U-shaped curve between GDP and emissions per capita [20]. Rolling window analysis indicates that the use of renewable energy sources is gaining importance in reaching carbon neutrality. In emerging nations, the per capita emission may rise when it surpasses the capacity of the increased use of renewable sources of energy [21].

The use of renewable sources of energy contributes greatly to the reduction in carbon emissions in OECD nations. Renewable energy and emissions in OECD nations are negatively correlated, meaning that the more use of renewable energy, the lower the emissions of [22]. Geothermal energy, biomass hydrogen, and solar energy are the types of renewable energy that are highly effective in reducing emissions in the top 27 OECD nations. There is a causality that exists between emission and renewable energy in OECD nations, and this indicates that the two vary in relation to each other [23]. Economic growth increases emission in nations except when the use of renewable energy has an elasticity of between −0.016 and −0.5% in those nations.

Moreover, aside from the net benefits, the current literature also stresses that the net emissions-reducing ability of renewable energy sources is actually very sensitive to the carbon weight of the energy sector that already exists. Based on the nonlinear models, the more carbon-polluting sectors will benefit more from the abatement benefits of renewables than the already relatively cleaner energy structure that relies more heavily upon the service sector and nuclear power sources [24,25,26]. Even the negative limitations in the integration of solar power into the energy mix, as well as its intermittency characteristics, are also foreseen to have reduced the effectiveness of the net emissions-reducing ability in the early stages of the transition process.

2.2. Emission and Economic Growth

emissions and economic growth in the OECD nations reveal complicated patterns that are contrary to conventional environmental models. It has been shown in several pieces of work that the existence of EKC models in Asia and other regions has some variation [27]. There exists a quadratic relationship that confirms the EKC model, and an inverted N-shaped relationship that invalidates the conventional environmental predictions of the EKC model [28]. Generally, the N-shaped relationship has been observed in the case of OECD nations. Consumption of renewable energy sources and quality of institutions are negatively influencing factors for emission, whereas non-renewable energy sources and industries are positively influencing factors that augment emission. Oil prices are negatively correlated with emissions. Technological change lessens the sensitivity of economic growth to pollutants [27].

emissions connect economic growth and the SDGs. There have been very complicated relationships that have developed in different scenarios. Many studies have shown that, in the short run, economic growth leads to increased emissions, and the use of renewable energy can decrease them, achieving SDGs 7 and 13 [29]. Nonetheless, this is different based on the level of development. In developing countries, the EKC holds, yet in low-income nations, the relationship is U-shaped [30]. Energy use is one of the factors that contribute to emissions in the short and long run. Some interventions in different nations have attempted to decouple economic growth and emissions based on changes in energy and carbon intensities. Results have confirmed the importance of holistic governance that deals with several SDGs together [31].

The relationship between economic growth and emissions has increasingly been seen through the prism of structural transformations instead of income levels. Recent findings have revealed that economic growth has a positive impact on reduced emissions only when the economy undergoes transformations toward a low-energy-sector-oriented economy and improves its energy efficiency. However, economic growth that relies either on the expansion of the industry or the manufacturing sector for export purposes worsens the existing emission levels even within the high-income economies of the OECD countries. This has triggered debates to move toward the perception that the EKC is conditional and not universal in nature [32].

2.3. Emission and Population Growth

Population growth has been identified as the force driving the rise in emissions globally. It has been projected that it would account for half of the rise in emissions in 2025 [33]. However, this factor has been observed to be differential for the OECD nations. Analysis of the OECD nations has identified the existence of evidence for the quadratic relationship between economic growth and emission in those nations [27]. Factors such as urbanization augment emission levels, and the use of green and renewable energy reduces emission. Fossil fuels and energy consumption are usual augmenters of emissions. Thus, the need for the development of clean energy resources and environmental protection policies remains paramount [34].

Environmentally, Luxembourg is faced with many problems owing to its fast-rising population and development. Luxembourg has the highest emissions per capita in the OECD nations. This is especially due to commuting rates and low fuel costs relative to its rival nations [35]. Comparing the different regions in Europe, it can be seen that the effect of the population on emissions differs in terms of elasticity. In the case of Luxembourg, it has been proven that the Environmental–Economic Balance (ECB) exists between economic growth and environmental quality. Nonetheless, environmental protection and developmental growth can be achieved when programs are in place [36]. The consumption of green energy in Luxembourg is very promising and holds hope for reaching the 2030 and 2050 climate aims [37].

Demographic dynamics affect greenhouse gas emissions not only through scale but also through population concentration, behavior, and structure. In OECD countries, aging can dampen the growth of greenhouse gas emissions, while population concentration and migration-related population growth can enhance transport and housing-related emissions. It has been noted in more recent research on population growth and the environment that population growth and population composition can and should be treated separately, in that city density, household size, and transport behavior can have more far-reaching implications than population growth per se [38,39].

2.4. Emission and Environmental Policies

Econometric studies conducted on the OECD countries showed complex and state-dependent relationships between economic variables and natural events. Although a certain reduction could be achieved through environmental taxes and more stringent regulatory policies, a strong heterogeneity of policy effectiveness has been pointed out in the literature. In this regard, for instance, the ‘polluter pays’ approach and environmental assessments are essential in a given country but prove incomplete depending on the country’s own decisions regarding its economic system and sectoral integration, which is dealt with and explored in this study, recognizing that the effectiveness of a measure is necessarily related to the current degree of pollution. The use of renewable sources of energy shows a negative relationship between the variables [14]. Nonetheless, the results for green innovation are inconclusive. Some reports demonstrate positive coefficients, whereas others present insignificant results [15]. GDP correlates positively with emissions, but this pattern may be inverted in higher income ranges, as proposed in the EKC hypothesis. Politically stable factors are highly effective in lowering emissions. Back-casting on past data indicates that decoupling phenomena for the GDP–emissions relationship diverged for different nations of the OECD between 1990 and 2019 [3].

Denmark has higher per capita greenhouse gas emissions compared to the average in the EU. In spite of this, it is at the forefront of climate change and green economy action. Denmark has taken an integrated approach to environmental policy that encompasses carbon taxes and tax reforms. Climate change action in Denmark aims at making the country independent of fossil fuels and aims at cutting greenhouse gases by 70% compared to those of 1990 levels in 2030 and making the country independent of fossil fuels in 2050 [40]. Denmark is at the forefront in the use of carbon tax systems. Scientific analysis argues that it is an effective way of lowering emissions [41]. It is difficult to achieve cost-effective emission cuts in every sector. Financial sagacity and energy efficiency play an important role in helping to achieve consumption-based emission cuts. It can play an important role in countering financial risks that are climate-change-related [42].

Also, “more recent contributions to environmental economics stress the nonlinear nature of the effective toolkit and its interaction with the state of the environment,” pointing to the fact that taxes or market instruments work best when the level of environmental discharges crosses the point where the cost of controls exceeds that of compliance costs. Below this point, “inadequate enforcement and political opposition weaken the effectiveness of environmental policies,” suggesting that this can explain why environmental policies do not work in low-emission states but have been highly effective in high-emission areas [43].

2.5. Emission and Green Innovation

There is evidence of a dominantly negative link between emissions and green innovation in the case of OECD nations. It has been observed that many studies have indicated that emissions for OECD nations decrease [15]. Interestingly, this implies that it is a nonlinear relationship [26]. Increasing evidence shows that the relationship between green innovation and carbon emissions is no longer a linear process. In particular, the present study points to the nonlinear effects of green innovation and distinct regimes in which the role of technological change can differ or face a ‘‘rebound effect’’ in more advanced levels of technology. Through a closer look at these nonlinear relations, we are now in a position to examine why the role of innovation is more significant in a higher percentile of carbon emissions in which there is a greater possibility of replacing inefficient and carbon-rich infrastructure. There are three regimes that have been identified in which the effect of environmental innovation changes, including the possible rebound effect at higher levels. The effect of green innovation has been observed to be much more important in higher percentiles of carbon emissions. Renewable energies and environmental measures are often quoted as contributing factors in green innovation [15]. R&D spending leads to reductions in emissions, and it increases with energy intensity. Interestingly, it implies that green innovation is an important approach for fulfilling climate objectives in the case of OECD nations.

In the area of environmental patents, Germany is at the forefront of the pack, after the United States of America, Japan, and South Korea. However, efficiency and emissions are influenced by the level of development of the country in question. The EKC hypothesis has been validated [44]. Innovative factors have played a role in the reduction in emissions in European nations, albeit less influential compared to the effects of economic activities. Innovation and emissions are country-specific and are positively associated with certain investments within sectors and emissions [45]. Germany’s vigorous environmental movement and its lead role in environmental protection demonstrate the efficiency of its climate change policy.

Green innovation directs emission reductions through both efficiency and substitution dynamics; however, green innovation has an impact in a way that is determined by nonlinear dynamics as well as rebound. Although nascent green innovation might contribute to rising greenhouse gas emissions in the short term due to expansion in size, established innovation systems might help transition out of carbonate capital and thus reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Nonlinear and quantile regression analysis has verified that in high-emission economies, green innovation has maximum emission-reducing potential because small increments in green technological changes give high returns [26,46].

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Data

Data for this analysis came from an imbalanced panel data set of 33 members of the OECD. It can be asserted that this group of nations makes for an optimal case analysis because of the members’ level of development and their substantial share of CO2 emissions in the world. All this is indicated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Profile of the 33 OECD Member Nations by Regional and Emission Characteristics (1990–2022).

In this analysis, an annual panel data set for the years 1990–2022 is collated from internationally recognized institutional repositories, specifically the World Development Indicators (WDI) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which provide standardized, peer-validated, and harmonized longitudinal data across member nations. There are six main variables that are identified in this analysis to capture the dynamics of the environmental and economic systems. emissions (CE), consumption of renewable energy (REN), economic growth (EG), and growth of population (PG) are derived from the WDI sources. Environmental policies (EPs), GDP contributed by tax revenues connected to the environmental domain, and green innovation (gi), the progression of environmental-related technological innovation, are obtained from the OECD sources. All the variables are taken in their conventional units designated in their specific sources. Details of the variables are highlighted in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of variables, definitions, and data sources for the drivers of carbon emissions in the 33 OECD Member Nations (1990–2022).

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics for the variables used in this study, including CE, REN, EG, PG, EP, and GI, based on 759 observations. The results indicate substantial variability across variables, with CE exhibiting high dispersion and pronounced right skewness, reflecting the presence of extreme values. Several variables deviate from normality, as confirmed by skewness, kurtosis, and Jarque–Bera statistics, suggesting non-normal distributions. These characteristics justify the use of advanced econometric techniques capable of handling heterogeneity and distributional asymmetries.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics of the sampled variables for the 33 OECD Member Nations by Regional and Emission Characteristics (1990–2022).

3.2. Methodology

This study uses advanced panel data and econometric methods to examine the determinants of carbon emissions (CE) in OECD countries. First, Pesaran, Frees, and Fisher tests were applied to identify potential inter-unit dependence. Second-generation unit root tests, i.e., Cross-Sectionally Augmented IPS (CIPS) and Cross-Sectionally Augmented Dickey–Fuller (CADF), were then applied to determine the stationarity levels of the variables. Next, a slope heterogeneity test was conducted to determine whether slope coefficients differed across countries. Westerlund and advanced Dickey–Fuller (DF) panel cointegration tests were applied to investigate long-run relationships between the series. FGLS and Driscoll–Kraay (DKSE) estimators, robust to cross-dependence, were used to estimate long-run coefficients. Finally, the Quantile–Quantile (QQR) method was applied to examine the effects of independent variables on each distributional quantile. By contrast to traditional OLS Regression or other forms of Quantile Regression, the value of QQR for this analysis is its ability to trace the role of particular levels of specific independent variables (for instance, very high levels of renewable energy use) as determinants of specific levels of the dependent variable (for instance, high carbon emission rates). The nonlinear effects of policy reaction to environmental policy instruments apply specifically to OECD economies, enabling us to test whether an effective policy for low emissions has the same effects at high emissions. The choice of the QQR method is justified by its theoretical underpinnings to account for the presence of intrinsic heterogeneity as well as cross-sectional dependence that exists in the economies of OECD member states. Conventional methods relying on mean estimates, such as FGLS and DKSE, yield a valuable overall effect but disregard the ‘extremes’ that are primarily subject to policy interventions. The main strength of the QQR approach derives from its ability to treat parameters not only within the context of the overall distribution of carbon emissions, which serves as its dependent variable, but also within the context of the overall distribution of their drivers, such as the penetration of renewable energy sources or innovations. As such, QQR captures asymmetry effects, where, for instance, a certain level of green innovations creates high ‘returns’ within a high-emission ‘dirty’ state of an industrialized economy but only creates marginal gains within a low-emission ‘clean’ economy that is primarily service-oriented. We applied these methods to capture broad environmental trends and identify how socio-economic factors affect carbon emissions differently at various levels of the distribution. Algorithm 1 below corresponds to the empirical construction of the QQR “surface” figures reported in Section 4.

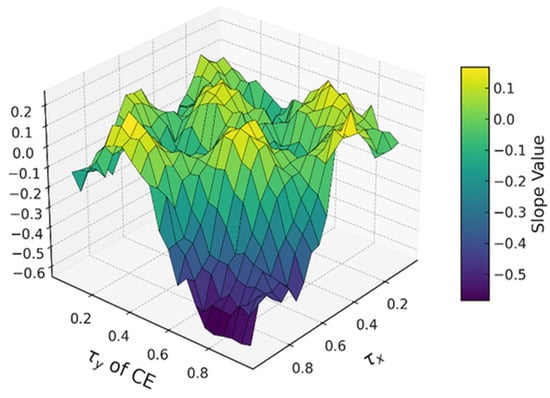

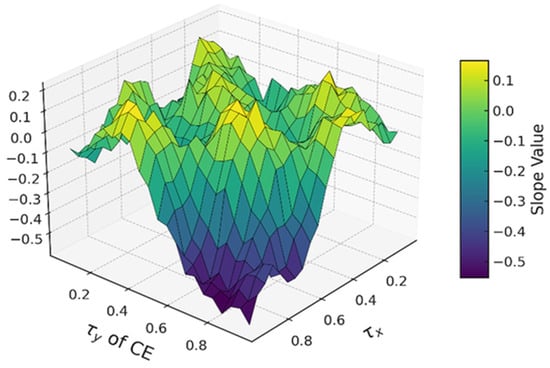

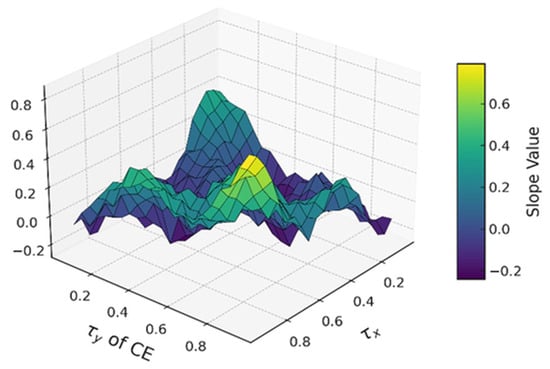

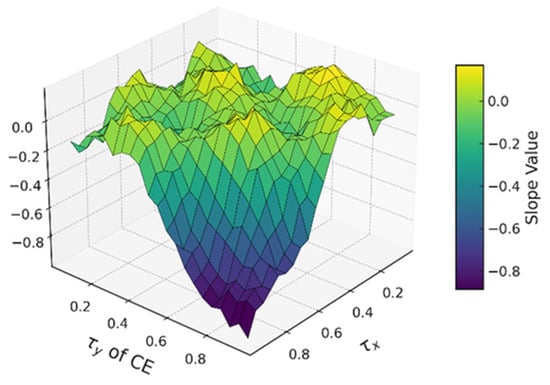

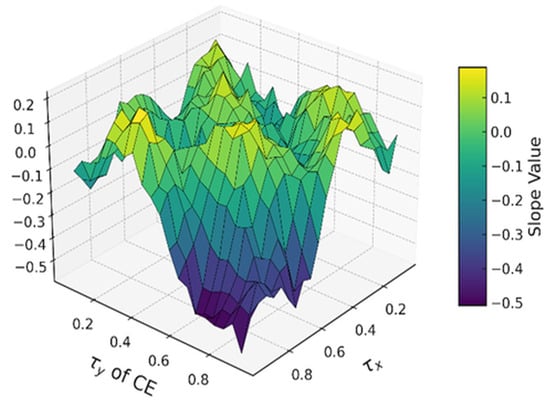

| Algorithm 1. Quantile-on-Quantile Regression (QQR) Procedure |

| Select quantile grids: Define quantiles for the dependent variable and for each explanatory variable over τ ∈ {0.05, 0.10, …, 0.95}. Compute conditional quantiles: For each τy, obtain the τy quantile of CE; for each τx, obtain the τx-quantile of the chosen regressor X. Local approximation: Around each regressor quantile τx, apply a local linear approximation (kernel-weighted) linking CE(τy) to deviations of X from X(τx). Estimate slope surfaces: For every (τx, τy) pair, estimate the QQR slope coefficient β(τx, τy), producing a quantile-by-quantile response surface. Repeat for all regressors: Run Steps 2–4 separately for REN, EG, PG, EP, GI to obtain each surface (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5). Interpretation: Interpret β (τx, τy) as the effect of regressor X at quantile τx on CE at quantile τy (e.g., “high X–high CE” vs. “low X–low CE”). |

Figure 1.

Quantile-on-Quantile Surface Between REN and CE.

Figure 2.

Quantile-on-Quantile Surface Between EG and CE.

Figure 3.

Quantile-on-Quantile Surface Between PG and CE.

Figure 4.

Quantile-on-Quantile Surface Between EP and CE.

Figure 5.

Quantile-on-Quantile Surface Between GI and CE.

The estimated basic model is as follows:

where : carbon emissions, : renewable energy, : economic growth, : population growth, : environmental policies, : green innovation.

In panel data analysis, one must first determine whether there is cross-sectional dependence between units. In country groups with high economic interaction, such as OECD countries, it is quite possible that shocks may spread across countries. Therefore, the presence of cross-sectional dependence (CD) plays a role in determining the tests and estimation methods to be used. Therefore, in this study, Pesaran CD, Frees’ test, and Fisher’s test were used to determine inter-unit dependence.

Pesaran CD Test Formula:

where : the correlation between the error terms of units i and j; N: number of horizontal sections; and T: time dimension.

The Pesaran CD statistic is evaluated under the assumption of a standard normal distribution. The hypotheses for the test are defined as follows:

H0.

No cross-sectional dependence ( = 0)

H1.

Cross-sectional dependence exists ( ≠ 0)

In the next stage, since cross-sectional dependency was detected in the panel data structure of the study, second-generation unit root tests CIPS (Cross-Sectionally Augmented IPS) and CADF (Cross-Sectionally Augmented Dickey–Fuller) tests developed by Pesaran were applied in order to determine the stationarity levels of the series.

Basic Regression Equation of the CADF Test:

where : the value of the variable; : the average value of all units; : unit root parameter; and Δ: first difference operator.

CIPS statistics are obtained by averaging the CADF statistics for the entire panel.

The hypotheses for the test are defined as follows:

H0.

The series contains a unit root (non-stationary)

H1.

The series is stationary

Because cross-sectional dependence was detected in the panel, the slope heterogeneity test was used to examine whether the coefficients were similar across countries. It is unrealistic to expect the coefficients to be homogeneous across OECD countries. The test developed by Pesaran and Yamagata calculates the Delta statistic using the estimated slope coefficients for each country.

The general formula of the test is as follows:

where S is the Swamy test statistic, showing the spread of the estimation of the slope to the joint weighted estimate, and k is the number of independent variables in the model. In this study, the values of k = 5 and include the variables ren, eg, pg, ep, and gi.

After determining the stationarity levels of the variables, the existence of a long-run relationship in the panel was examined using Westerlund and the improved DF cointegration tests. The Westerlund test uses error-correcting dynamics to determine whether the series share a common long-run equilibrium.

The basic logic of the test is based on the following error correction equation:

Here, if < 0, cointegration is present. In addition to the Westerlund test, Modified Dickey–Fuller (MDF), DF, Adjusted Dickey–Fuller (ADF), and unadjusted DF tests calculated for the panel were also applied.

In order to obtain accurate long-run estimates, two techniques that can effectively handle cross-sectional dependence and heterogeneity for this panel data were applied. These are the FGLS and DKSE techniques. The FGLS estimator is a method that can effectively address heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation from the residuals, hence yielding more accurate estimates. The DKSE method, on the other hand, offers standard errors that remain robust to the type of cross-sectional dependence, regardless of the panel dimensions.

The study uses the Quantile-on-Quantile Regression (QQR) technique to investigate the differential effects of the independent variables on average, as well as across the whole distribution of carbon emissions. The QQR method investigates the different quantiles of the dependent and independent variables simultaneously to discover if there is a uniform effect of low, medium, and high emissions. With this technique, the value of the independent variable for a given quantile is paired with the value of the carbon emissions for a given quantile, and a corresponding slope coefficient for each quantile and independent variable is estimated. In the context of “Green Governance,” the salient advantage offered by this method is the identification of the “rebound effect” and the diminishing returns of innovation, which are subtleties that are obscured in average estimators, such as the FGLS and DKSE estimators. This is because the QQR approach provides a three-dimensional perspective on the relationship, facilitating more effective “tailored” policies, rather than the “one-size-fits-all” approach.

4. Results and Discussion

The results in Table 4 show consistent evidence of cross-sectional dependence within the panel data set. The Pesaran CD, Fisher, and Frees tests yield highly significant statistics, with p-values equal to 0.00, thereby leading to a strong rejection of the null hypothesis of no cross-sectional dependency at the 1% significance level. The results show that the countries in our study are interconnected; therefore, economic shocks in one nation likely influence environmental outcomes in others.

Table 4.

Results of cross-sectional dependence (CSD) tests for environmental and economic variables across the studied countries.

Table 5 reports the findings of the unit root tests for both CIPS and CADF, and it is clear that there is strong evidence to reject the null of homogeneous non-stationarity for each of the variables included in this analysis. For each of the series CE, REN, EG, PG, EP, and GI, the test statistics for both the CIPS and CADF tests are highly significant at the 1% level, as denoted by the triple asterisk. The repeated significance of the test indicates that the variables in this analysis are not stationary at the unit root level and are instead stationary in levels.

Table 5.

Second-generation panel unit root test results (CIPS and CADF).

From Table 6 below, it can be seen that the results of the slope test of heterogeneity are highly significant at the 1% level for both Δ and ΔAdj statistics, having values of −5.88 and −6.29, respectively, and p-values of 0.00. Consequently, the null hypothesis of slope homogeneity is rejected, and this implies that the relationship between the variables of interest varies significantly across the cross-sectional units.

Table 6.

Results of the Pesaran and Yamagata slope heterogeneity test.

The findings of the cointegration test in Table 7 present strong and consistent evidence of rejection of the null hypotheses of no cointegration amongst the variables. Even though the Westerlund test is only marginally significant at the 10% level (p-value of 0.07), still the values of the other test statistics, such as Modified Dickey–Fuller, Dickey–Fuller, Augmented Dickey–Fuller, and their unadjusted versions, are very large and of much higher significance at the 1% level (p-value of 0.00), and thus present sufficient evidence about the existence of a stable long-run equilibrium relationship amongst the variables in the panel data.

Table 7.

Panel cointegration diagnostics: Westerlund and modified Dickey–Fuller test statistics.

From Table 8, it can be observed that the results of the point estimates of the FGLS and the DKSE models are similar in terms of the sign of the coefficients and their level of significance, and this makes them highly robust in determining the factors that influence CE. In both the FGLS and the DKSE models, it is observed that the coefficients of the variables REN, EG, and GI are negatively and significantly associated with CE, and this implies that the increased use of REN, EG, and GI is a contributing factor in reducing carbon emissions. However, the coefficients of the variables PG and EP are positively and significantly associated with CE in both models, and this implies that PG and EP are some of the factors that contribute to increased carbon emissions. Even though there are slight differences in the magnitudes and significance levels of the FGLS and the DKSE estimates, it can be concluded that the results are similar and highly valid in determining that the increased use of REN, proper EG, and improved GI can help in reducing carbon emissions in the future.

Table 8.

Static panel analysis results using Feasible Generalized Least Squares (FGLS) and Driscoll–Kraay Standard Errors (DKSEs).

For quantile-in-quantile model, τx is the independent variable (X) at the REN, EG, PG, EP, or GI quantile level. It exists between 0.05 and 0.95 on the graph; therefore, we are not looking at the raw value of X, but where it stands in the distribution. τy is the dependent variable (CE) quantile level. It also ranges between 0.05 and 0.95 and tells us if we are considering the effect in low-emission environments, mid-level emissions, or high-emission environments. The Z-axis represents the estimated slope coefficient for each combination of τx-τy from the Quantile-On-Quantile Regression. A negative slope means that increasing the independent variable lowers CE at the specified quantile combination. A positive slope would imply that an increase in the independent variable increases CE at that quantile pair.

The choice of QQR is validated by the heterogeneity observed in the results. From Figure 1, the slope of the QQR is generally negative for most quantile values, and this implies that as the level of REN penetration increases, the level of CO2 emissions for the distribution will decrease. However, when both REN and CE are in higher quantiles, it indicates that in environments that emit higher CO2, it is better to increase the share of renewable energy to decrease emissions. It approaches zero for lower quantiles of REN, and this implies that within environments that use less REN, renewable energy does not play an important role, especially in environments that use little REN. When REN and CE are in higher quantiles, results show that a higher share of renewable energy has been found to be strongly effective in highly emitting systems. From a policymaker’s standpoint, this is because nations such as Germany or Australia have historically been among the top carbon emitters, but these nations have managed to cut their carbon emissions by integrating high levels of windy or sunny energy into their energy mix. In highly emitting quantiles, the energy system is highly ‘carbon-saturated,’ which means that for every megawatt of renewable energy, carbon-emitting energy in the form of coal is directly displaced.

Referring to Figure 2, it can be seen that the slope of QQR for EG is generally negative, especially in the mid-to-high quantiles of EG and in the top quantiles of CE, indicating that when emission levels are higher, economic growth can be paired with decreased emissions, perhaps due to efficiency gains in the economy. However, in the lower quantiles of EG, the slope is flat or slightly positive in some quantiles of CE, indicating that in lower-growth scenarios, economic activities can continue to rely on carbon-intensive sectors, degrading environmental outcomes.

In Figure 3, the slope of robust is generally positive in most combinations of quantiles for PG, indicating that as average population growth increases, CO2 emissions will further rise, especially when emissions are already high, perhaps due to increased energy use and consumption. Even when the quantiles are lower for PG, the positivity of the slope indicates that in highly emitting nations, any slight growth in the country’s population would contribute to increased emissions.

In EP of Figure 4, there is a strong and steady negative slope of QQR, and this is strongest for large EP quantiles and large CE quantiles. This implies that good environmental tax structure and legislation are very effective in lowering emissions in large environmental issue country-years or large EP quantile-years. For small EP quantile-years, it is slightly negative or zero, such that poor environmental policies are less effective in lowering emissions irrespective of the size of the CE quantile. The result that environmental tax structures (EP) are more effective for large CE quantile-years implies that fiscal instruments also work when there is a certain degree of industrial carbon intensity. In a high-polluting environment such as the USA or Türkiye, carbon taxes or environmental taxes can serve as an effective deterrent by incorporating environmental externalities. The slope becomes zero for low EP and low CE quantiles, indicating a ‘policy inertia’ where insufficient environmental legislation does not bring any change since the economic cost of pollution is not high enough to induce a change in behavior.

GI also shares the same negative slope index pattern as REN, and for the largest reductions in CE, the high–high quantile area (high GI, high CE) is identified as the most significant. This can indicate that in circumstances of large emissions, and perhaps with additional precedence for abandoning current, carbon-based methods in favor of modern environmental methods, the additional benefits are particularly substantial. In situations of low GI, the slope is less steep, and it implies that in scenarios in which widespread use of environmental methods has not yet occurred, less emission reduction is possible (Figure 5). The high–high quantile region for GI and CE is determined to be the most crucial for reduction. This can be understood with reference to the concept of ‘technological leapfrogging.’ In the high-emitting OECD nations and countries where their industrial base is aging, the application of green innovation (for example, carbon capture or hydrogen-based fuel cells) leads to leapfrogging over carbon-based growth. This is seen in the case of nations such as Denmark, where ground-breaking green innovation has led to a better decoupling between growth and emissions compared with nations with lower innovation quantiles. In low-innovation pathways, nations could be ‘locked-in’ to carbon industries under which modern environmental practices are too costly and/or unavailable.

Results of this analysis reveal that the consumption of renewable energy, green innovation, and efficiency are negatively associated with carbon emissions, while the effects of population and economic growth are positively influencing factors. Results are consistent with many findings in the literature. For instance, [47] revealed that the use of renewable energy has played a significant role in lessening environmental pollution in large renewable energy-consuming nations, and this complements the negative coefficients of the QQR surfaces for REN. In addition, [48] indicated that both the use of renewable energy and green innovation are factors that can positively influence environmental quality, and this confirms this paper’s findings on GI.

Notwithstanding the fact that most of the results are aligned with the existing literature, there were some findings that did not entirely support our initial expectations. First of all, economic growth and carbon emissions have not displayed a uniformly negative relationship across all quantile levels but have manifested positive or weakly negative associations in low-carbon regimes, thereby implying the lack of a shift away from carbon-intensive sources even in some OECD countries. Moreover, environmental policies have not displayed effectiveness in lower quantile levels of environmental emissions and stringency, thereby implying the possible necessity of overcoming particular enforcement or pollution thresholds before the effectiveness of fiscal and regulatory channels. Finally, the abatement effect of green innovation has been relatively more sizable in a high-carbon regime than in a low-carbon one.

The affirmative effect of population on emissions is also in line with the literature on demography and the environment. Ref. [49], for example, have confirmed that increases in population are correlated to increased energy consumption and emissions, supporting the strong and affirmative association between PG and CE. In addition, the affirmative associations between economic growth and emissions for the lower quantile can be explained in parallel with the findings of [50], which highlighted that emerging or infant economies still rely on coal for several purposes.

However, certain literature reports contradict certain findings of the current analysis. For example, findings by [51] reveal that EG may lead to a decrease in environmental emissions for nations in the process of structural transformation towards pollution-free sectors, and this contradicts the finding of the current analysis that supports the EG-CE link in certain quantiles. These findings may arise due to differences in the nature of their economies.

Contradictions are also seen in the literature on environmental policies. Though the present analysis finds that EP has weak or contradictory effects in the lower quantiles, [52] indicated that environmental taxation has had a significant effect on emission reduction in the long run, which is further confirmed in [53] concerning institutional quality and power of regulation in emerging markets. In light of such findings, it can be hypothesized that the enforcing capacity of each country might play an important role in determining the effect of environmental policies on emission reductions.

Despite existing literature that reveals that green energy has emission reductions, some literature, including that of [54], finds that green energy has little effect on emissions. Such disparities can be justified when green energy makes little addition to the total energy consumption of the nation.

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

The findings from the empirical analysis have yielded unequivocal evidence about the influencing factors in carbon emissions in the OECD. Estimates from the FGLS and DKSE equations have clearly shown the following: firstly, it appears that the impact of renewable energy consumption, economic growth, and green innovation is significant in reducing carbon emissions. This is particularly remarkable since the contrasting factor, population growth, is a persistent amplifier of ecosystem deterioration. Most importantly, the findings from the Quantile-on-Quantile Regression analysis have clearly shown the following: firstly, the impact is highly heterogeneous in nature. This is also the case since the impact of renewable energy consumption and green innovation is most effective at the upper quantiles. Quantile-on-Quantile Regression analysis further confirms the above results and adds that the effect of each of the above factors on lowering carbon emission rates remains different at different points in the distribution of carbon emission, and on the other hand, environmental prices are always effective in each scenario, especially in those areas that face or are threatened by environmental problems.

In combination, the evidence points to the role of structural conditions in the economy, demographic forces, the effectiveness of policies, and institutional capacity in influencing the course of carbon emissions. Further, such relationships vary in different sections of the emissions distribution, emphasizing the need for contextual approaches over standardized policies.

Findings reveal that, in addition to focusing on those that are more influential in reaching this objective, it is also necessary to address those that are expected to exacerbate the situation. Increasing investments in the use of renewable sources of energy remains vital, and this effort must be given closer attention in environments that emit higher rates of greenhouse gases, as it can be very influential in terms of reducing such emissions.

By nature, the growing number of people means higher emissions, and for this reason, planning for cities and energy use must change and include factors like optimized transport systems and better use of resources. Improving environmental tax treatment can achieve considerable emissions reductions, especially in those nations that have higher emissions in terms of carbon output.

Having strong institutional quality is also required because improving governance leads to better implementation of environmental standards and thus helps in embracing environmentally friendly technologies. Policies need to be specific based on the position of the country or region in relation to emissions because effects are different for different levels of emissions.

In conclusion, in making future policies, it would be important to use analytical tools that incorporate the observed heterogeneity and cross-sectional dependence, making proposed policies empirically valid and context-specific.

Limitations and Future Prospects

Although the econometric evidence is strong, this study admits a number of limitations, which form a rich area for further study. Although the results can be seen as a roadmap for both advanced and partner economies, the applicability of the results to poor economies that are not part of the OECD might be more complex due to variations in the strength of institutions and industry structures. Future work can be conducted to apply this study to either the African or Southeast Asian region to verify whether the values for the QQR coefficients are comparable to those obtained from a different “locked-in” carbon dependency setting.

This study makes use of macroeconomic panel data to portray large-scale country-specific dynamics. It does not incorporate perspectives or methods that incorporate microeconomic firm dynamics or household consumption patterns that are responsible for a significant amount of emissions. Future research can be conducted to incorporate firm-level datasets to study how governance practices at a corporate firm level can alter the QQR coefficients for firms that are subject to environmental taxes.

In this study, we made use of a set of environmental governance and innovation variables as a premise for results. Adding values for financial stability, trade openness, or geopolitical risks as additional elements for models might help to further refine the QQR surfaces.

Future research can be conducted to break down emissions into industry-specific sectors such as transportation, industry, and agriculture to help policymakers derive a roadmap that is not based solely on a sector’s overall “Kt of equivalent” as used in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.T.-S. and M.S.; methodology, F.T.-S. and M.S.; software, M.S.; validation, F.T.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P. and S.Ü.-E.; writing—review and editing, F.T.-S. and M.S.; visualization, F.T.-S.; supervision, F.T.-S. and M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

In this analysis, annual panel data for the years 1990–2022 is collated from trusted international sources such as the World Development Indicators (WDI) and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). There are six main variables that are identified in this analysis to capture the dynamics of the environmental and economic systems. emissions (ce), consumption of renewable energy (ren), economic growth (eg), and growth of population (pg) are derived from the WDI sources. Environmental policies (ep), GDP contributed by tax revenues connected to the environmental domain, and green innovation (gi), and the progression of environmental-related technological innovation, are obtained from the OECD sources. All the variables are taken in their conventional units designated in their specific sources.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Obobisa, E.S. An econometric study of eco-innovation, clean energy, and trade openness toward carbon neutrality and sustainable development in OECD countries. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 3075–3099. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J. Decomposition of Aggregate CO2, Emissions in the OECD: 1960–1995. Energy J. 1999, 20, 147–155. [Google Scholar]

- Magazzino, C.; Pakrooh, P.; Abedin, M.Z. A decomposition and decoupling analysis for carbon dioxide emissions: Evidence from OECD countries. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 28539–28566. [Google Scholar]

- Güney, T. Renewable energy and sustainable development: Evidence from OECD countries. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2021, 40, e13609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Sinha, A.; Tan, Z.; Shah, M.I.; Abbas, S. Achieving energy transition in OECD economies: Discovering the moderating roles of environmental governance. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 168, 112808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbakwuru, V.; Obidi, P.O.; Salihu, O.S.; MaryJane, O.C. The role of renewable energy in achieving sustainable development goals. Int. J. Eng. Res. Updates 2024, 7, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzger, N.; Shenai, V. Economic growth and human development in OECD countries: A twenty-year study of data 2000–2019. J. Eur. Econ. 2021, 20, 585–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, A.; Blanco Arana, C. Financial Development and Economic Growth: A Study For OECD Countries in the Context of Crisis. REM Working Paper 046–2018. 2018. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3224317 (accessed on 22 August 2018).

- Baily, M.N. The sources of economic growth in OECD countries: A review article. Int. Product. Monit. 2003, 7, 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Abel, G.J.; Barakat, B.; Kc, S.; Lutz, W. Meeting the Sustainable Development Goals leads to lower world population growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 14294–14299. [Google Scholar]

- Aksoy, Y.; Basso, H.S.; Smith, R.P.; Grasl, T. Demographic structure and macroeconomic trends. Am. Econ. J. Macroecon. 2019, 11, 193–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffing, K.G. The role of the organization for economic cooperation and development in environmental policy making. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2010, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohag, K.; Islam, M.M.; Hammoudeh, S. From policy stringency to environmental resilience: Unraveling the dose-response dynamics of environmental parameters in OECD countries. Energy Econ. 2024, 134, 107570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Abid, N.; Yang, S.; Ahmad, F. From crisis to resilience: Strengthening climate action in OECD countries through environmental policy and energy transition. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 115480–115495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kafeel, K.; Zhou, J.; Phetkhammai, M.; Heyan, L.; Khan, S. Green innovation and environmental quality in OECD countries: The mediating role of renewable energy and carbon taxes. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 2214–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sami, F.; Khan, S.; Alamri, A.M.; Zaidan, A.M. Green innovation and low carbon emission in OECD economies: Sustainable energy technology role in carbon neutrality target. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 59, 103401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavi, R.K.; Standing, C. Eco-innovation analysis with DEA: An application to OECD countries. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Inf. Syst. 2017, 12, 133–147. [Google Scholar]

- Mensah, C.N.; Long, X.; Dauda, L.; Boamah, K.B.; Salman, M.; Appiah-Twum, F.; Tachie, A.K. Technological innovation and green growth in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development economies. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 240, 118204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gierałtowska, U.; Asyngier, R.; Nakonieczny, J.; Salahodjaev, R. Renewable energy, urbanization, and CO2 emissions: A global test. Energies 2022, 15, 3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szetela, B.; Majewska, A.; Jamroz, P.; Djalilov, B.; Salahodjaev, R. Renewable energy and CO2 emissions in top natural resource rents depending countries: The role of governance. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 872941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, W.; Rabnawaz, K. Renewable energy and CO2 emissions in developing and developed nations: A panel estimate approach. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1405001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perone, G. The relationship between renewable energy production and CO2 emissions in 27 OECD countries: A panel cointegration and Granger non-causality approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 139655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahendra, E.G.G.; Gunarto, T.; Aida, N. The role of energy transition and intensity on CO2 in oecd countries. Int. J. Account. Manag. Econ. Soc. Sci. 2025, 3, 1001–1012. [Google Scholar]

- Sadorsky, P. Renewable energy consumption and income in emerging economies. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 4021–4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apergis, N.; Payne, J.E. Renewable energy, output, CO2 emissions, and fossil fuel prices in Central America: Evidence from a nonlinear panel smooth transition vector error correction model. Energy Econ. 2014, 42, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, D.Ç.; Esen, Ö.; Yıldırım, S. The nonlinear effects of environmental innovation on energy sector-based carbon dioxide emissions in OECD countries. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 182, 121800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaghdoudi, T. Oil prices, renewable energy, CO2 emissions and economic growth in OECD countries. Econ. Bull. 2017, 37, 1844–1850. [Google Scholar]

- Bulut, A.; Tekdemir, N. The inverted n-shaped relationship between economic growth and CO2 emissions: Evidence from OECD countries. Econ. Ann. 2025, 70, 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, A.; Kayani, F.N.; Rafae, G.A.E.; Kayani, U.N.; Aziz, A.L. Transitioning towards low carbon economy: Role of renewable energy, economic growth and FDI in achieving SDGs. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2025, 15, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.; Kautish, P.; Shahbaz, M. Unveiling the complexities of sustainable development: An investigation of economic growth, globalization and human development on carbon emissions in 64 countries. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 3612–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngankam, B.T. Sustainable Development Goals Synergies/Trade-offs: Exploring Long-and Short-Run Impacts of Economic Growth, Income Inequality, Energy Consumption and Unemployment on Carbon Dioxide Emissions in South Africa. J. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 12, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, D.I. The environmental Kuznets curve after 25 years. J. Bioeconomics 2017, 19, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, A. Population growth and global carbon dioxide emissions. In Proceedings of the IUSSP Conference, Salvador de Bahia, Brazil, 18–24 August 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H.; Khan, M.K.; Rehman, A.; Dagar, V.; Oryani, B.; Tanveer, A. Impact of globalization, institutional quality, economic growth, electricity and renewable energy consumption on Carbon Dioxide Emission in OECD countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 24191–24202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandt, N. Vers une Croissance Plus Verte en Luxembourg; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Irokanulo, J.U.; Beton Kalmaz, D. Revisiting the EKC validity in Luxembourg and the time-varying causality between environmental quality and its main determinants. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2025, 36, 639–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, R. Review and growth prospects of renewable energy in Luxembourg: Towards a carbon-neutral future. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Smart Grid and Renewable Energy (SGRE), Doha, Qatar, 8–10 January 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- O'neill, B.C.; Dalton, M.; Fuchs, R.; Jiang, L.; Pachauri, S.; Zigova, K. Global demographic trends and future carbon emissions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 17521–17526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liddle, B. Impact of population, age structure, and urbanization on carbon emissions/energy consumption: Evidence from macro-level, cross-country analyses. Popul. Environ. 2014, 35, 286–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batini, N.; Parry, I.; Wingender, P. Climate Mitigation Policy in Denmark: A Prototype for Other Countries. 2020/235. 2020. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/publications/wp/issues/2020/11/12/climate-mitigation-policy-in-denmark-a-prototype-for-other-countries-49882 (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Ghazouani, A.; Xia, W.; Ben Jebli, M.; Shahzad, U. Exploring the role of carbon taxation policies on CO2 emissions: Contextual evidence from tax implementation and non-implementation European Countries. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyebanji, M.O.; Kirikkaleli, D.; Awosusi, A.A. Consumption-based CO2 emissions in Denmark: The role of financial stability and energy productivity. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2023, 19, 1485–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghion, P.; Dechezleprêtre, A.; Hemous, D.; Martin, R.; Van Reenen, J. Carbon taxes, path dependency, and directed technical change: Evidence from the auto industry. J. Political Econ. 2016, 124, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pata, U.K.; Sofuoglu, E.; Ahmed, Z.; Kizilkaya, O. Eco-innovation and environmental sustainability in Germany: An empirical approach with smooth structural shifts. In Natural Resources Forum; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Doran, N.M.; Bădîrcea, R.M.; Jianu, E.; Antoniu, M.E.; Ciobanu, R.M.; Ciobanu, Ș.C.F. Unveiling CO2 Emission Dynamics Under Innovation Drivers in the European Union. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Aghion, P.; Bursztyn, L.; Hemous, D. The environment and directed technical change. Am. Econ. Rev. 2012, 102, 131–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, E.; Seker, F. Determinants of CO2 emissions in the European Union: The role of renewable and non-renewable energy. Renew. Energy 2016, 94, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsalobre-Lorente, D.; Shahbaz, M.; Roubaud, D.; Farhani, S. How economic growth, renewable electricity and natural resources contribute to CO2 emissions? Energy Policy 2018, 113, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poumanyvong, P.; Kaneko, S. Does urbanization lead to less energy use and lower CO2 emissions? A cross-country analysis. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 70, 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destek, M.A.; Sinha, A. Renewable, non-renewable energy consumption, economic growth, trade openness and ecological footprint: Evidence from organisation for economic Co-operation and development countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 118537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Solarin, S.A.; Mahmood, H.; Arouri, M. Does financial development reduce CO2 emissions in Malaysian economy? A time series analysis. Econ. Model. 2013, 35, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkos, G.E.; Paizanos, E.A. The effect of government expenditure on the environment: An empirical investigation. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 91, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamazian, A.; Rao, B.B. Do economic, financial and institutional developments matter for environmental degradation? Evidence from transitional economies. Energy Econ. 2010, 32, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocal, O.; Aslan, A. Renewable energy consumption–economic growth nexus in Turkey. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 28, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.