Abstract

Aggressive corporate tax avoidance represents a significant fiscal and governance challenge in developing economies, where public revenues are critical for sustainable development and enforcement capacity is often uneven. This study examines whether environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance constrains corporate tax avoidance and whether this relationship is conditioned by national institutional quality. Using a multi-country panel of 2464 publicly listed non-financial firms from 14 developing economies over the period 2015–2023, the analysis employs fixed-effects estimation, dynamic System GMM, and instrumental-variable (2SLS) techniques to address unobserved heterogeneity and endogeneity concerns. The results indicate that stronger ESG performance is associated with significantly lower levels of tax avoidance; however, this effect is highly contingent on institutional quality. ESG exerts a substantive disciplining role primarily in governance-strong environments characterized by effective regulation and credible enforcement. Heterogeneity analyses further reveal that the ESG–tax avoidance relationship is driven mainly by the governance and environmental pillars, is more pronounced among large firms, varies across regions, and strengthens over time as ESG frameworks mature. In contrast, the social ESG dimension and smaller firms exhibit weaker or insignificant effects, consistent with symbolic compliance in low-enforcement settings. By integrating stakeholder, legitimacy, agency, and institutional theories, this study advances a context-sensitive understanding of ESG effectiveness and helps reconcile mixed findings in the existing literature. The findings offer policy-relevant insights for regulators and tax authorities seeking to strengthen fiscal discipline and development financing in developing economies.

1. Introduction

Aggressive tax planning has emerged as a critical policy and governance challenge across both advanced and emerging economies. Its consequences are particularly severe in developing countries, where fiscal capacity is often constrained and public revenues are essential for financing infrastructure, social welfare, and long-term development objectives. By exploiting regulatory gaps, complex tax rules, and weak enforcement mechanisms, aggressive tax planning undermines governments’ ability to mobilize domestic resources and erodes confidence in the fairness and integrity of corporate conduct [1,2,3]. As a result, corporate tax behavior is increasingly viewed not merely as a technical financial decision, but as an ethical and governance issue reflecting firms’ broader commitments to transparency, accountability, and social responsibility [4,5,6].

Corporate income taxation represents a critical component of public revenue systems in developing economies. According to the OECD Corporate Tax Statistics, corporate tax revenues accounted for approximately 16% of total tax revenues and 3.2% of GDP globally in 2021. Importantly, reliance on corporate taxation is substantially higher in developing regions, where corporate taxes constitute, on average, 18.7% of total tax revenues in Africa, 18.2% in Asia and the Pacific, and 15.4% in Latin America and the Caribbean, compared to only 10.2% in OECD member countries. This heightened dependence implies that aggressive corporate tax avoidance poses a systemic fiscal risk for developing economies, directly constraining governments’ capacity to finance public investment, social expenditure, and sustainable development objectives [7].

Unlike traditional corporate governance mechanisms—such as board composition, ownership structure, or executive oversight—which primarily function as internal monitoring devices, ESG frameworks operate as extended governance systems. ESG integrates stakeholder oversight, reputational discipline, and external accountability beyond firms’ internal controls. While conventional governance tools rely on formal internal mechanisms, ESG practices embed firms within broader regulatory, market, and societal evaluation processes. Prior studies show that ESG engagement can constrain managerial opportunism by enhancing transparency, reducing information asymmetry, and exposing firms to intensified scrutiny from investors, regulators, and civil society [4,8,9]. Through legitimacy pressures and market-based evaluation, ESG practices are therefore particularly relevant for governance outcomes involving ethical discretion, such as corporate tax avoidance [10,11].

Against this backdrop, a growing body of literature examines whether ESG performance functions as a disciplining mechanism capable of constraining aggressive tax planning. Drawing on stakeholder and legitimacy theories, prior studies argue that firms with strong sustainability commitments face heightened external scrutiny, making aggressive tax strategies reputationally costly and increasingly inconsistent with claims of responsible business conduct. Empirical evidence provides partial support for this argument, showing that firms with higher ESG performance tend to exhibit lower tax avoidance, reduced book–tax differences, and more conservative tax strategies [4,11,12,13]. Recent evidence further suggests that governance-related ESG dimensions and board-level sustainability mechanisms are particularly effective in curbing aggressive tax behavior by strengthening oversight and accountability structures [12,14,15].

However, empirical findings remain mixed. Cross-country, emerging-market, and meta-analytical studies document substantial heterogeneity in the ESG–tax relationship across institutional settings, ESG measurement approaches, and tax avoidance proxies [1,5,6]. Moreover, several studies report ESG–tax decoupling, whereby firms strategically deploy ESG disclosures or sustainability initiatives to mitigate reputational risks while continuing aggressive tax planning practices [9,10,16]. These findings suggest that ESG performance alone may be insufficient to systematically explain variations in corporate tax behavior, particularly across heterogeneous governance environments and regulatory regimes.

A key explanation for these mixed results is that the ESG–tax relationship does not operate in isolation but is embedded within national institutional environments. Institutional quality shapes enforcement credibility, regulatory oversight, and the economic and reputational costs associated with non-compliance. This institutional dimension is especially salient in developing countries, where governance quality varies widely and enforcement is often uneven. Weak rule of law and limited administrative capacity may allow firms to benefit from ESG signaling without substantively altering tax practices, whereas stronger institutional environments intensify monitoring and increase the legal and reputational costs of aggressive tax planning [5,17]. Prior research consistently highlights that institutional quality conditions the effectiveness of transparency initiatives, governance reforms, and sustainability practices more broadly [18,19].

Despite its theoretical and policy relevance, the moderating role of institutional quality remains underexplored in the ESG–tax literature, particularly from a developing-country perspective. Existing studies predominantly focus on single-country settings or samples dominated by advanced economies, limiting the generalizability of findings to contexts characterized by weaker institutions, evolving ESG frameworks, and heightened vulnerability to revenue losses from aggressive tax planning [6,13,17]. Consequently, it remains unclear under what institutional conditions ESG commitments translate into substantive fiscal discipline rather than symbolic compliance.

Addressing these gaps, this study investigates whether ESG performance constrains aggressive corporate tax planning in developing countries and whether this relationship is contingent on national institutional quality. Two research questions guide the analysis. First, does stronger ESG performance reduce aggressive tax planning among firms operating in developing economies? Second, does institutional quality moderate the ESG–tax relationship by strengthening ESG’s disciplinary effect in governance-robust environments?

To answer these questions, the study assembles a multi-country panel of firms from 14 developing economies, combining standardized ESG indicators, firm-level financial data, and national measures of institutional quality. This design enables a systematic examination of how sustainability performance interacts with governance environments to shape corporate tax behavior in contexts where aggressive tax planning poses significant risks to development outcomes.

This study makes five key contributions. First, it provides novel cross-country evidence on the ESG–tax avoidance relationship in developing economies, a context that remains underexplored despite its substantial fiscal and governance relevance. Second, it advances theory by integrating stakeholder, legitimacy, agency, and institutional perspectives into a unified framework that explains both the direction and conditionality of ESG effects on corporate tax behavior. Third, the study demonstrates that ESG’s disciplining role is heterogeneous across firm size, ESG dimensions, and regional institutional contexts. Fourth, it shows that ESG effectiveness is dynamic rather than static, strengthening as sustainability frameworks and enforcement mechanisms mature. Finally, by employing a comprehensive empirical strategy—including fixed-effects estimation, dynamic System GMM [20], instrumental-variable (2SLS) identification, and heterogeneity analyses—the study provides robust evidence on when ESG commitments translate into substantive fiscal discipline rather than symbolic compliance.

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Theoretical Framework

The relationship between ESG performance and corporate tax behavior is best understood through an integrated theoretical framework combining stakeholder theory, legitimacy theory, and agency theory, with institutional theory providing a critical contextual layer. This multi-theoretical approach is particularly appropriate in developing-country settings, where governance quality, regulatory enforcement, and monitoring capacity vary substantially across countries [1,6].

From a stakeholder theory perspective, firms are embedded in a network of relationships with investors, regulators, employees, customers, and broader society, all of whom increasingly expect responsible and transparent corporate behavior. Although aggressive tax planning may remain legally permissible, it is often perceived as socially undesirable because it undermines public finances and violates norms of fiscal fairness. Firms with stronger ESG performance therefore face heightened stakeholder scrutiny and normative pressure to align sustainability commitments with responsible tax conduct. In this sense, ESG functions as an extended governance mechanism that increases the reputational, relational, and market-based costs of aggressive tax avoidance. Empirical evidence supports this view, showing that firms with higher ESG or CSR engagement tend to exhibit lower tax avoidance, smaller book–tax differences, and more conservative fiscal strategies [4,8,12,21].

Legitimacy theory further explains why sustainability-oriented firms may refrain from aggressive tax behavior. Corporate legitimacy depends on maintaining congruence between organizational actions and prevailing societal norms and expectations. As taxation has increasingly become a salient component of corporate social responsibility and ESG credibility, aggressive tax planning may threaten organizational legitimacy when it contradicts firms’ publicly stated sustainability narratives. Recent research emphasizes that corporate tax behavior is no longer evaluated in isolation but is scrutinized as part of a firm’s broader ESG profile by investors, regulators, and civil society [18,22]. Consequently, firms with strong ESG profiles face greater pressure to ensure consistency between sustainability disclosures and actual tax practices. However, legitimacy pressures are uneven across institutional contexts. In weak-governance environments—common in many developing economies—firms may strategically deploy ESG disclosures to manage reputational risk while continuing aggressive tax planning, reflecting symbolic rather than substantive compliance [9,10].

Agency theory highlights the internal incentive structures that motivate aggressive tax behavior. Managers may engage in tax avoidance to improve short-term financial performance, meet earnings targets, or extract private benefits, particularly when monitoring mechanisms are weak. ESG frameworks—especially governance-related dimensions—complement traditional internal governance mechanisms by enhancing transparency, reducing information asymmetry, and strengthening monitoring beyond formal board and ownership structures. Prior studies show that ESG-driven governance arrangements and board-level sustainability mechanisms constrain managerial discretion and limit opportunities for opportunistic financial and tax-related behavior [5,12,23,24].

While stakeholder, legitimacy, and agency theories predict that ESG engagement should discourage aggressive tax behavior, they do not fully explain the substantial cross-country heterogeneity documented in the empirical literature. Institutional theory provides this missing contextual dimension. The effectiveness of ESG commitments depends critically on the quality of national institutional environments, including regulatory quality, rule of law, and government effectiveness. These institutional characteristics shape both the enforcement of tax regulations and the credibility of sustainability practices [17,19].

In countries with strong institutional frameworks, firms face higher probabilities of detection, more effective regulatory oversight, and stronger stakeholder scrutiny. Under such conditions, inconsistencies between ESG claims and aggressive tax behavior are more easily identified, sanctions are more credible, and reputational penalties are more severe. Conversely, in weak institutional environments, firms may benefit from ESG signaling without materially altering tax planning behavior, facilitating the ESG–tax decoupling observed in several emerging-market and cross-country studies [6,10,16]. This institutional contingency explains why prior research reports mixed and context-dependent findings regarding the ESG–tax avoidance relationship.

Taken together, stakeholder and legitimacy theories explain the external pressure channels through which ESG performance raises the reputational and normative costs of aggressive tax behavior, while agency theory captures the internal governance mechanisms through which ESG reduces managerial discretion and opportunism [4,8,12]. Institutional theory integrates these perspectives by explaining when these external and internal mechanisms translate into substantive behavioral outcomes rather than symbolic compliance [1,6]. Specifically, institutional quality conditions the credibility of enforcement, the intensity of monitoring, and the salience of reputational sanctions, thereby amplifying or weakening ESG’s disciplining effect on corporate tax avoidance [2,10].

Accordingly, ESG should be viewed as a complementary governance mechanism whose effectiveness depends on institutional enforcement and monitoring capacity rather than as a substitute for traditional corporate governance tools. The integrated theoretical logic underpinning the study is summarized in Figure 1, which illustrates the direct effect of ESG performance on corporate tax avoidance and the moderating role of institutional quality.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework of ESG Performance, Institutional Quality, and Corporate Tax Avoidance.

2.2. Hypotheses Development

2.2.1. ESG Performance and Corporate Tax Avoidance

Building on stakeholder, legitimacy, and agency theories, ESG performance is expected to function as an extended governance mechanism that constrains aggressive corporate tax behavior. From a stakeholder perspective, firms with stronger ESG performance are subject to heightened scrutiny from investors, regulators, and civil society, which increases the reputational and relational costs associated with aggressive tax planning. Even when tax avoidance remains legally permissible, it may be perceived as inconsistent with broader societal expectations regarding fairness, fiscal responsibility, and sustainable value creation [4,8].

Legitimacy theory further suggests that firms committed to sustainability seek alignment between publicly disclosed ESG narratives and internal financial practices. As corporate taxation has increasingly become a salient dimension of ESG credibility, aggressive tax strategies may undermine organizational legitimacy and expose firms to reputational penalties, regulatory attention, and stakeholder backlash [18,22]. Consequently, firms with stronger ESG profiles face greater incentives to adopt more conservative tax strategies in order to maintain consistency between sustainability commitments and actual corporate behavior.

Agency theory complements this view by emphasizing the internal governance role of ESG frameworks. ESG-related governance mechanisms—such as enhanced disclosure, stronger monitoring, and board-level oversight—reduce information asymmetry and constrain managerial discretion, thereby limiting opportunities for opportunistic tax behavior driven by short-term performance incentives or private benefits [5,12]. Empirical evidence across developed and emerging markets supports these theoretical arguments, documenting a negative association between ESG or CSR performance and various measures of tax avoidance, including book–tax differences and effective tax rates [4,8,12,21].

Although prior studies report mixed findings, recent meta-analytical and review evidence suggests that ESG performance is more likely to constrain aggressive tax behavior when reputational and governance pressures are salient, particularly for firms engaging in extreme or aggressive tax practices [1,6]. Based on this integrated theoretical reasoning, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1.

ESG performance is negatively associated with corporate tax avoidance.

2.2.2. The Moderating Role of Institutional Quality

While ESG frameworks provide an external governance mechanism, their effectiveness is not uniform across institutional environments. Institutional theory posits that national governance structures—such as regulatory quality, rule of law, and government effectiveness—shape the credibility of enforcement, the intensity of monitoring, and the economic and reputational costs associated with non-compliance. These institutional characteristics are particularly important in developing countries, where governance quality and enforcement capacity vary substantially across jurisdictions [17,19].

In countries with stronger institutional quality, ESG disclosures are more likely to be monitored, verified, and enforced by regulators, investors, and other stakeholders. Under such conditions, inconsistencies between ESG claims and aggressive tax behavior are more easily detected, sanctions are more credible, and reputational penalties are more severe. As a result, ESG performance is more likely to translate into substantive fiscal discipline rather than symbolic compliance. Empirical evidence supports this conditional view, showing that the ESG–tax avoidance relationship is stronger in governance-robust environments and weaker or insignificant in settings characterized by weak enforcement and limited regulatory capacity [1,6,10].

Conversely, in weak institutional environments, firms may exploit ESG signaling to enhance legitimacy and manage reputational risk without materially altering aggressive tax planning practices. This ESG–tax decoupling has been documented in several emerging-market and cross-country studies, where weak rule of law and limited enforcement reduce the disciplining power of sustainability commitments [9,10,16]. Accordingly, institutional quality is expected to condition the effectiveness of ESG as a governance mechanism. Based on this reasoning, the following moderating hypothesis is proposed:

H2.

Institutional quality strengthens the negative relationship between ESG performance and corporate tax avoidance.

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample Selection and Data Collection

This study employs a multi-country panel dataset to examine whether ESG performance constrains corporate tax avoidance (also referred to as tax aggressiveness or aggressive tax planning) and whether this relationship is conditioned by national institutional quality in developing economies. Firm-level ESG scores, financial statements, and accounting data are obtained from Refinitiv Eikon (version 2024; London Stock Exchange Group, London, UK), which provides standardized and internationally comparable ESG metrics and is widely used in sustainability, governance, and tax avoidance research [4,8].

The sample period spans 2015–2023. The starting year (2015) reflects a structural shift in global sustainability governance following the adoption of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the expansion of ESG disclosure frameworks, which substantially improved ESG data coverage, consistency, and cross-country comparability, particularly in developing economies [1,6,18]. The end year (2023) corresponds to the latest period for which firm-level ESG, tax, and institutional quality data are consistently available and validated across all sampled countries at the time of data collection, thereby avoiding reporting gaps, data revisions, and survivorship bias. Similar sample endpoints are commonly adopted in recent ESG–tax avoidance studies relying on Refinitiv/Eikon data [9,12].

The initial universe consists of publicly listed firms covered by Refinitiv Eikon in 14 developing countries. Following established practice in ESG–tax research [8,12], several filters are applied. Financial institutions are excluded due to their distinct regulatory environments, accounting standards, and tax regimes. Firms with missing ESG scores, tax variables, or key financial information are removed. Observations with implausible or extreme tax outcomes are excluded, and all continuous variables are winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles to mitigate the influence of outliers, consistent with prior tax avoidance studies [11]. To ensure panel reliability and support fixed-effects and interaction estimations, firms are required to have at least three consecutive years of observations, in line with prior ESG–tax panel research [17].

The detailed sample construction process is summarized in Appendix A, Table A1.

Country-level institutional quality indicators are drawn from the World Governance Indicators (WGI, 2024 release; World Bank, Washington, DC, USA), capturing regulatory quality, rule of law, and government effectiveness, which are widely used proxies for institutional quality in cross-country governance and tax studies [17,19]. Macroeconomic control variables, including GDP growth and inflation, are obtained from the World Bank World Development Indicators (WDI, 2024 edition; World Bank, Washington, DC, USA) [14].

The final analytical sample consists of 2464 publicly listed non-financial firms, yielding 17,424 firm-year observations, across Brazil, China, Colombia, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Jordan, Malaysia, Mexico, Morocco, Philippines, South Africa, Thailand, and Turkey. Firms are listed on their respective national stock exchanges, as reported in Appendix A, Table A2. For additional transparency, an indicative country-level distribution of firms is reported in Appendix A, Table A3.

All regression models include industry, year, and country fixed effects to control for unobserved heterogeneity across sectors, time, and institutional environments.

3.2. Research Model and Identification Strategy

The empirical strategy is designed to evaluate (i) the direct effect of ESG performance on corporate tax avoidance and (ii) the moderating role of national institutional quality in shaping this relationship. This framework is grounded in stakeholder, legitimacy, and institutional theories, which jointly predict that ESG commitments constrain aggressive tax behavior more effectively in governance-robust environments.

To ensure a rigorous and transparent identification strategy, the analysis follows a three-stage empirical sequence:

- Baseline fixed-effects estimation, assessing whether ESG performance is associated with lower levels of corporate tax avoidance after controlling for unobserved firm heterogeneity.

- Moderation analysis, introducing institutional quality and its interaction with ESG performance to test whether governance environments condition the ESG–tax avoidance relationship.

- Endogeneity-robust estimations, employing dynamic panel System GMM and instrumental-variable (2SLS) regressions to address potential reverse causality, simultaneity, and persistence in tax behavior [25].

All econometric analyses are conducted using Stata (version 17; StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA). This layered approach mitigates concerns related to omitted variable bias, dynamic endogeneity, and feedback effects between ESG engagement and corporate tax strategies, which are well documented in the sustainability and tax avoidance literature.

3.3. Measurement Equations

3.3.1. Baseline Model

To analyze the association between ESG performance and corporate tax avoidance (also referred to as tax aggressiveness or aggressive tax planning) for firms operating in developing countries, the following panel-data regression model is specified:

where BTD denotes book–tax differences, used as a proxy for corporate tax avoidance; i indexes firms and t denotes the fiscal year (2015–2023). ESG captures firm-level sustainability performance, and X is a vector of firm-level and macroeconomic control variables. Firm-level controls include firm size, profitability, leverage, and asset tangibility, while GDP growth and inflation capture macroeconomic conditions. Firm fixed effects (μi), year fixed effects (λt), and country fixed effects (δc) are included to control for unobserved heterogeneity across firms, time, and institutional environments.

BTDi,t = α0 + α1·ESGi,t + α2·Xi,t + μs + λt + δc + εi,t

3.3.2. Moderation Model

To assess whether institutional quality conditions the ESG–tax avoidance relationship, the following interaction model is estimated:

where WGI captures national institutional quality based on the World Governance Indicators, reflecting regulatory quality, rule of law, and government effectiveness. The interaction term (ESG × WGI) tests whether stronger institutional environments amplify the disciplining effect of ESG performance on corporate tax avoidance. A significantly negative coefficient on the interaction term supports the moderating hypothesis. Detailed definitions of all variables are provided in Table 1.

BTDi,t = γ0 + γ1·ESGi,t + γ2·WGIc,t + γ3·(ESGi,t × WGIc,t) + γ4·Xi,t + μs + λt + δc + vi,t

Table 1.

Definitions and Measurement of Variables.

3.3.3. Endogeneity Considerations

Panel-data estimation reduces bias arising from unobserved firm-specific heterogeneity and improves estimation efficiency. However, ESG performance and tax avoidance may still be jointly determined or influenced by unobserved factors. To address these concerns, the baseline and moderation models are complemented by dynamic panel System GMM and 2SLS estimations, following best practice in recent ESG, governance, and tax avoidance studies [15,25]. System GMM explicitly accounts for persistence in tax behavior and potential reverse causality, while 2SLS provides additional identification based on external instruments.

4. Empirical Investigation

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 reports the descriptive statistics for the variables used in the empirical analysis. The mean value of BTD (0.072) indicates moderate levels of corporate tax avoidance, while its positive skewness and high kurtosis suggest that a subset of firms engages in relatively aggressive tax planning, consistent with heterogeneous tax behavior in developing economies. The average ESG score (58.40) reflects moderate but uneven sustainability performance, with substantial dispersion providing sufficient variation to assess ESG’s potential disciplining role. The mean WGI value (−0.142) indicates generally weak governance environments, while its wide range highlights considerable institutional heterogeneity across countries. Firm-level characteristics and macroeconomic variables also exhibit meaningful variation, reflecting diverse financial structures and economic conditions. All continuous variables are winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles to mitigate the influence of outliers [6,25].

Table 2.

Summary of Descriptive Statistics.

4.2. Correlation Matrix and Multicollinearity Diagnostics

Table 3 reports the Pearson correlation matrix for the variables used in the analysis. Overall, the correlation coefficients are moderate in magnitude, indicating that multicollinearity is unlikely to pose a serious concern in the regression estimations.

Table 3.

Correlation Matrix and VIF.

Consistent with prior evidence, BTD is negatively correlated with ESG performance, suggesting that firms with stronger sustainability engagement tend to exhibit lower levels of corporate tax avoidance [4,8]. Institutional quality (WGI) is also negatively associated with tax avoidance, while being positively correlated with ESG performance, indicating that governance-robust environments are conducive to both stronger sustainability practices and lower tax aggressiveness [1,17].

Firm-level controls display correlations in line with expectations. Firm size is negatively correlated with BTD and positively correlated with ESG performance, while leverage shows a positive association with tax avoidance, consistent with the use of debt-related tax shields [11,18]. Correlations involving macroeconomic variables are low, suggesting that GDP growth and inflation capture country-level conditions largely orthogonal to firm-specific characteristics.

Importantly, none of the pairwise correlation coefficients exceed conventional thresholds (|r| ≥ 0.70). Variance inflation factor (VIF) diagnostics, reported in Table 4, further confirm that multicollinearity does not materially affect the empirical models, with all VIF values well below the commonly accepted threshold of 10 [25].

Table 4.

Fixed-Effects Panel Regression Results.

4.3. Baseline Regression Results

Table 4 reports the baseline fixed-effects regression results and robustness tests using two alternative measures of corporate tax avoidance. Models (1) and (2) employ BTD as the dependent variable, while Models (3) and (4) use the cash effective tax rate (Cash ETR) to capture cash-based tax avoidance behavior. Using both accrual- and cash-based proxies ensures that the findings are not driven by the choice of a specific tax avoidance measure.

In Model (1), the coefficient on ESG performance is negative and highly significant, indicating that firms with stronger sustainability performance exhibit lower BTD and, therefore, lower levels of tax avoidance. This result provides strong support for H1 and is consistent with prior evidence that ESG engagement strengthens governance and constrains opportunistic tax planning [4,8]. The finding aligns with stakeholder and legitimacy perspectives, suggesting that sustainability-oriented firms face greater reputational and accountability pressures to adopt responsible fiscal behavior.

Model (2) introduces institutional quality and its interaction with ESG performance. Following standard practice, ESG and institutional quality are mean-centered prior to constructing the interaction term to reduce multicollinearity and facilitate interpretation [11]. The interaction term (ESG × WGI) is negative and statistically significant, indicating that the inverse relationship between ESG performance and tax avoidance becomes stronger as institutional quality improves. This result supports H2 and suggests that governance conditions amplify the disciplining effect of ESG commitments.

Beyond statistical significance, the estimated coefficients are economically meaningful. A one-standard-deviation increase in ESG performance (approximately 17 points) is associated with a reduction in BTD of about 1.4 percentage points of total assets, representing a sizable decline relative to the sample mean BTD of 7.2%. Moreover, a one-standard-deviation improvement in institutional quality further strengthens this effect by approximately 25–30%, highlighting the importance of governance environments in translating ESG engagement into substantive fiscal discipline. The direct effect of institutional quality is also negative and significant, reaffirming its independent role in constraining aggressive tax behavior.

Models (3) and (4) re-estimate the baseline and moderation specifications using Cash ETR as an alternative proxy for tax avoidance. Because higher Cash ETR values indicate greater tax compliance, positive coefficients reflect reduced tax avoidance. Consistent with the BTD results, ESG performance is positive and statistically significant in Model (3), indicating that sustainability-oriented firms remit higher cash taxes. This finding confirms that ESG constrains tax avoidance not only through accrual-based mechanisms but also through actual cash tax payments [20,22].

In Model (4), the interaction between ESG performance and institutional quality remains positive and statistically significant, indicating that stronger governance environments reinforce the tax-compliance effect of ESG performance. Although the magnitude of the interaction is smaller than in the BTD specifications, the consistency in sign and significance across both tax measures underscores the conditioning role of institutional quality. The direct effect of institutional quality is also positive and significant, suggesting that firms operating in higher-quality institutional environments remit higher cash taxes.

Across all specifications, the control variables behave in line with theoretical expectations and prior literature. Firm size, leverage, and asset tangibility are positively associated with BTD and negatively associated with Cash ETR, reflecting scale- and structure-related opportunities for tax planning. Profitability is negatively related to BTD and positively related to Cash ETR, indicating that more profitable firms tend to avoid the reputational and regulatory risks associated with aggressive tax behavior. At the macroeconomic level, higher GDP growth is associated with lower tax avoidance, while higher inflation is linked to greater fiscal aggressiveness.

All models include industry, year, and country fixed effects, mitigating concerns that the results are driven by sectoral characteristics, macroeconomic shocks, or country-specific factors [21,26,27]. The improvement in model fit following the inclusion of institutional quality and its interaction with ESG further suggests that governance conditions explain meaningful cross-country variation in corporate tax avoidance.

Marginal Effects of Institutional Quality

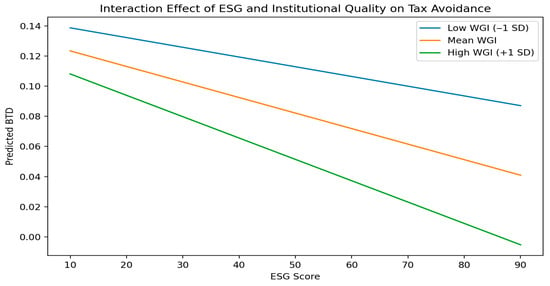

Figure 2 and Figure 3 illustrate the marginal effects of ESG performance on corporate tax avoidance at different levels of institutional quality, derived from the fixed-effects moderation models reported in Table 4. Figure 2 shows that the negative association between ESG performance and BTD becomes progressively stronger as institutional quality improves. This pattern indicates that ESG commitments are more effective in curbing aggressive tax planning when firms operate in governance environments characterized by stronger regulatory quality, rule of law, and enforcement credibility.

Figure 2.

Marginal Effect of ESG Performance on Book–Tax Differences.

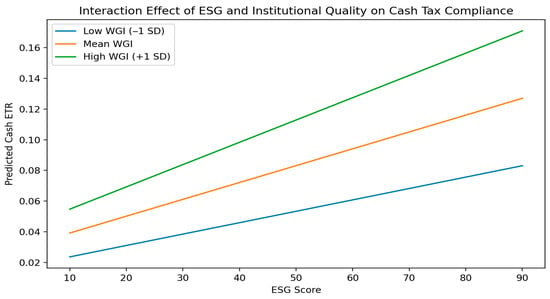

Figure 3.

Marginal Effect of ESG Performance on Cash Effective Tax Rates.

This figure illustrates the marginal effect of ESG performance on book–tax differences at low (−1 SD), mean, and high (+1 SD) levels of institutional quality, based on the fixed-effects moderation model reported in Table 4.

Using Cash ETR as an alternative measure of tax avoidance, Figure 3 reveals a consistent moderating pattern. The positive association between ESG performance and cash tax payments strengthens with higher institutional quality, implying that sustainability-oriented firms remit higher cash taxes when governance conditions are more robust. Although the magnitude of the interaction effect is smaller than in the accrual-based specifications, the direction and significance remain stable.

This figure illustrates the marginal effect of ESG performance on cash effective tax rates at low (−1 SD), mean, and high (+1 SD) levels of institutional quality, based on the fixed-effects moderation model reported in Table 4.

Overall, the marginal effects analysis provides clear visual confirmation of H2, demonstrating that institutional quality amplifies the disciplining role of ESG performance on corporate tax avoidance. These results reinforce the interpretation that ESG functions as a complementary governance mechanism whose effectiveness depends critically on the surrounding institutional framework.

4.4. Dynamic Panel Data Analysis

To address potential endogeneity, dynamic persistence, and simultaneity between ESG performance and corporate tax avoidance, the baseline models are re-estimated using the two-step System GMM estimator developed by Blundell and Bond [26]. This approach is widely applied in ESG–tax and corporate governance research when tax behavior exhibits persistence and key explanatory variables may be endogenous [10]. These concerns are particularly relevant in developing-country contexts, where firms often maintain stable tax planning routines and ESG practices may co-evolve with regulatory pressure, legitimacy concerns, and institutional conditions [5,9,28]. The following dynamic specification is estimated:

where BTDi,t−1 captures the persistence of tax avoidance, ESGi,t denotes the sustainability score, WGIc,t measures institutional quality, ESGi,t × WGIc,t captures the moderating effect of institutional quality, and Xi,t is the set of firm-level and macroeconomic controls (SIZE, ROA, leverage, asset tangibility, GDP growth, inflation). Firm-specific fixed effects (μi) and year effects (λt) control for unobserved heterogeneity and common time shocks.

BTDi,t = δ BTDi,t−1 + β1 ESGi,t + β2 WGIc,t + β3 (ESGi,t × WGIc,t) + β4 Xi,t + μi + λt + εi,t

Following best practice in dynamic ESG and corporate governance research, the lagged dependent variable, ESG performance, and institutional quality are treated as endogenous and instrumented using their own lagged levels and differences, while macroeconomic variables are treated as exogenous. To mitigate instrument proliferation, the instrument matrix is collapsed and lag depth is restricted, consistent with recent guidance for emerging-market System GMM applications [26].

Importantly, the number of instruments is kept below the number of cross-sectional units, ensuring reliable inference. As reported in Table 5, the Hansen test yields p-values of 0.347 and 0.291, indicating that the null hypothesis of instrument validity cannot be rejected. The Arellano–Bond tests further support model adequacy: the AR(1) test is statistically significant (p < 0.01), as expected in first-differenced equations, while the AR(2) test is insignificant (p > 0.10), indicating the absence of second-order serial correlation. Together, these diagnostics confirm that the moment conditions are correctly specified and that the System GMM estimator is appropriate for the analysis [29,30].

Table 5.

Dynamic Panel Data Results: System GMM Estimates.

Consistent with standard practice in dynamic panel estimation, the System GMM models are estimated on a reduced sample, as firms with insufficient time-series observations or valid lag structures are automatically excluded. The reduction in observations also reflects the inclusion of lagged dependent variables and restrictions on the instrument set.

The positive and highly significant coefficient on the lagged dependent variable confirms the dynamic persistence of corporate tax avoidance. In Model (1), ESG performance remains negative and statistically significant after controlling for endogeneity, indicating that sustainability-oriented firms exhibit lower tax avoidance even in a dynamic setting. This provides further support for H1 and reinforces the fixed-effects findings, consistent with arguments that ESG engagement enhances transparency, internal controls, and monitoring, thereby constraining aggressive tax planning [4,10,31].

Model (2) incorporates the interaction between ESG performance and institutional quality. The interaction term (ESG × WGI) is negative and statistically significant, indicating that stronger governance environments amplify the capacity of ESG practices to constrain tax avoidance, providing further support for H2. This result aligns with institutional theory and recent empirical evidence suggesting that ESG initiatives exert stronger behavioral effects in contexts characterized by credible regulatory oversight and effective enforcement [2,9]. In contrast, weak institutional environments may allow ESG activities to function primarily as reputational signals without materially constraining fiscal behavior [8,9].

Overall, the dynamic panel GMM estimates are fully consistent with the baseline fixed-effects results, confirming that the observed ESG–tax avoidance relationship and its institutional contingency are robust to endogeneity, simultaneity, and persistence concerns.

4.5. Instrumental Variable (2SLS) Robustness Analysis

To further strengthen the empirical identification of the ESG–tax avoidance relationship, this study conducts an additional robustness analysis using an instrumental-variable approach estimated via two-stage least squares (2SLS) (Table 6). This analysis addresses residual endogeneity concerns that may arise if ESG performance is jointly determined with corporate tax behavior or influenced by unobserved governance-related factors.

Table 6.

Instrumental Variable (2SLS) Regression Results.

Consistent with recent ESG–tax studies that explicitly employ instrumental-variable strategies [6,10,32,33], ESG performance is treated as endogenous and instrumented using industry–year average ESG scores, excluding the focal firm. This instrument captures exogenous variation in ESG adoption driven by peer effects, industry norms, and regulatory expectations, while remaining plausibly unrelated to firm-specific tax avoidance decisions except through its influence on ESG performance. Prior research shows that industry-level ESG intensity strongly predicts firm-level ESG engagement but does not directly affect individual firms’ tax planning behavior, thereby satisfying both relevance and exclusion conditions [6,10,34].

The first-stage regression confirms a strong and positive association between the instrument and firm-level ESG performance, with F-statistics well above conventional thresholds, indicating that weak-instrument concerns are unlikely [11]. In the second stage, the predicted values of ESG performance obtained from the first-stage regression are used to estimate their effect on corporate tax avoidance, measured by BTD. Standard errors are heteroskedasticity-robust and clustered at the firm level to account for within-firm dependence [32].

The 2SLS estimates indicate that ESG performance remains negatively and statistically significantly associated with BTD, suggesting that sustainability-oriented firms engage in lower levels of tax avoidance even after explicitly accounting for endogeneity. When institutional quality is incorporated as a moderating factor, the interaction between ESG performance and WGI remains negative and statistically significant, indicating that governance conditions continue to shape the strength of the ESG–tax avoidance relationship within the IV framework. These results are consistent with instrumental-variable evidence reported in recent ESG–tax studies across different institutional settings [6,10].

Overall, the 2SLS results corroborate the baseline and dynamic panel findings and confirm that the observed relationship between ESG performance, institutional quality, and corporate tax avoidance is not driven by reverse causality or omitted-variable bias.

4.6. ESG Pillar-Level Effects on Corporate Tax Avoidance

To examine whether the relationship between ESG performance and corporate tax avoidance is driven by specific sustainability dimensions, this study disaggregates the composite ESG score into its environmental (E), social (S), and governance (G) pillars. Prior research emphasizes that ESG components operate through distinct theoretical channels and may therefore exert heterogeneous effects on corporate tax behavior that are obscured by aggregate indices [3,6,10,16].

The baseline fixed-effects models are re-estimated by replacing the composite ESG score with each pillar score in turn (Columns 1–3 of Table 7). The moderation specifications further incorporate WGI and pillar-specific interaction terms (Columns 4–6), allowing an assessment of how environmental legitimacy pressures, social stakeholder engagement, and governance-based monitoring mechanisms influence corporate tax avoidance.

Table 7.

ESG Pillar-Level Fixed-Effects Regression Results.

The results reported in Table 7 reveal pronounced heterogeneity across ESG dimensions. The governance pillar exhibits the strongest and most consistent negative association with tax avoidance, both in the baseline and moderation specifications. This finding supports agency theory, suggesting that governance-related ESG mechanisms—such as enhanced transparency, accountability, and internal controls—directly constrain managerial discretion and reduce opportunistic tax behavior. Moreover, the significant interaction between the governance pillar and institutional quality (G × WGI) indicates that governance-oriented ESG practices are particularly effective in environments characterized by stronger regulatory enforcement and oversight [4,6,11].

The environmental pillar also displays a statistically significant negative relationship with tax avoidance, consistent with legitimacy-based explanations. Environmentally responsible firms face greater public visibility, regulatory attention, and reputational exposure, making aggressive tax planning increasingly costly and inconsistent with environmental commitments. The significant interaction between the environmental pillar and institutional quality (E × WGI) suggests that these external legitimacy pressures are amplified in countries with stronger institutional frameworks, where monitoring and enforcement are more credible [3,10].

In contrast, the social pillar shows weaker and statistically insignificant effects across both baseline and moderation specifications. This pattern suggests that social initiatives—such as employee welfare, community engagement, or diversity practices—are less directly connected to fiscal decision-making in developing-country contexts. Where disclosure scrutiny and enforcement capacity are limited, social ESG activities may remain partially decoupled from tax strategies, consistent with prior evidence on selective ESG adoption and symbolic compliance [8,9].

Overall, the pillar-level analysis confirms that the negative association between ESG performance and corporate tax avoidance is not an artifact of composite index aggregation. Rather, it is driven primarily by governance- and environment-related ESG mechanisms, which impose both internal monitoring and external legitimacy pressures on firms’ tax behavior. These findings reinforce the integrated theoretical framework and strengthen the robustness and interpretability of the main results.

5. Heterogeneity Analysis

5.1. Heterogeneity Analysis Based on Firm Size

To further examine whether the effect of ESG performance on corporate tax avoidance varies across organizational characteristics, this study conducts a heterogeneity analysis based on firm size [33]. In developing-country capital markets, firm size distributions are typically skewed, with a small number of large corporations and a broad base of medium- and small-sized firms. To account for this non-normality, firms are classified as small or large based on whether their total assets fall below or above the sample average—an approach commonly adopted in emerging-market accounting and finance research [6,10,14].

Using this criterion, approximately 42% of the sample (1035 firm) are classified as small firms, while 58% (1429 firms) are classified as large firms. This distribution reflects the structural characteristics of developing economies, where relatively few firms possess the scale, governance capacity, and market visibility typically associated with large corporations.

The baseline and moderation models are re-estimated separately for each sub-sample. The results reveal clear size-based asymmetries in the ESG–tax avoidance relationship.

As shown in Table 8, for large firms, ESG performance is negatively and statistically significantly associated with BTD, indicating that sustainability-oriented large firms engage in lower levels of tax avoidance. The magnitude of this effect exceeds that observed in the full sample, reflecting the heightened scrutiny, reputational exposure, and reporting obligations faced by larger firms. Large firms are typically more visible to regulators, investors, tax authorities, and civil society, which increases the probability that inconsistencies between ESG commitments and tax behavior are detected and sanctioned. Moreover, the interaction between ESG performance and institutional quality (ESG × WGI) is negative and statistically significant, suggesting that stronger governance environments further amplify ESG’s disciplining effect on tax avoidance. This finding indicates that institutional enforcement mechanisms are more effective when firms possess sufficient organizational capacity to internalize regulatory and reputational pressures. These results are consistent with prior evidence that large firms face stronger stakeholder monitoring and regulatory expectations, making ESG–tax alignment more binding [2,10].

Table 8.

Heterogeneity Analysis—Firm Size.

In contrast, for small firms, ESG performance is statistically insignificant across both baseline and moderation specifications, indicating no meaningful reduction in tax avoidance. The interaction between ESG and institutional quality is also insignificant, suggesting that stronger national governance does not materially strengthen the ESG–tax relationship for smaller firms. This pattern reflects lower firm visibility, weaker enforcement intensity, and limited internal governance capacity among smaller firms, which reduces the behavioral consequences of ESG adoption. Smaller firms often face less stringent disclosure requirements and lower scrutiny from regulators and external stakeholders, allowing ESG practices to remain largely symbolic rather than behaviorally constraining [5,8,9]. In developing-country contexts with uneven regulatory enforcement, symbolic ESG adoption may even facilitate strategic decoupling between sustainability narratives and fiscal behavior [1].

Overall, the heterogeneity analysis demonstrates that the disciplining effect of ESG performance on corporate tax avoidance is both size-dependent and institutionally contingent. ESG commitments exert economically and behaviorally meaningful influence primarily among larger firms, where organizational visibility, enforcement exposure, and governance capacity allow sustainability practices to translate into concrete fiscal discipline. Among smaller firms, ESG initiatives appear less effective in constraining aggressive fiscal practices, reflecting structural limitations, lower scrutiny, and weaker enforcement pressures in developing-country environments.

5.2. Regional Heterogeneity Analysis

Given the multi-country scope of the sample, this study examines whether the ESG–tax avoidance relationship varies across regional institutional contexts. Developing economies differ substantially in regulatory maturity, enforcement credibility, and ESG diffusion across regions such as Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Prior research emphasizes that ESG effectiveness is inherently context-dependent and shaped by region-specific governance trajectories [1,2,6,27].

To capture this variation, the baseline and moderation models are re-estimated separately for firms headquartered in Asia, Latin America, and MENA, consistent with recent cross-country ESG–tax avoidance studies [6,10,33].

The results in Table 9 reveal pronounced regional heterogeneity. The negative association between ESG performance and tax avoidance is strongest and most consistent in Asian economies, where ESG disclosure frameworks and regulatory oversight have developed more rapidly, allowing ESG commitments to translate into substantive constraints on aggressive tax planning [3,24]. In Latin America, ESG performance also exhibits a negative relationship with tax avoidance, but the effect is weaker, reflecting uneven enforcement capacity and regulatory consistency across countries in the region [33].

Table 9.

Regional Heterogeneity in the ESG–Tax Avoidance Relationship.

In contrast, in MENA countries, the direct effect of ESG performance on tax avoidance is weaker and less stable. However, the interaction between ESG performance and institutional quality is strong and statistically significant, indicating that ESG initiatives constrain tax behavior primarily when supported by stronger national governance frameworks. This finding is consistent with institutional theory and prior evidence of ESG–tax decoupling in governance-weak environments [8,9,28].

Overall, the regional analysis confirms that ESG effectiveness is not uniform across developing economies but depends critically on regional institutional development, enforcement credibility, and ESG maturity. These findings complement the baseline and heterogeneity analyses and underscore the importance of institutional context in shaping the fiscal consequences of corporate sustainability engagement.

5.3. Temporal Heterogeneity Analysis: ESG Maturity over Time

To assess whether the effectiveness of ESG practices in constraining corporate tax avoidance evolves as sustainability frameworks mature, this study conducts a temporal heterogeneity analysis using the longitudinal structure of the dataset. Prior research suggests that ESG mechanisms may initially function as symbolic signals but become more substantive as disclosure standards, stakeholder scrutiny, and enforcement capacity strengthen over time, particularly in developing economies [31,35,36].

Accordingly, the sample period (2015–2023) is divided into an early ESG adoption phase (2015–2018) and a mature ESG phase (2019–2023), consistent with evidence documenting notable improvements in ESG reporting quality and regulatory attention after 2018 [37]. The baseline and moderation models are re-estimated separately for each sub-period.

The results reported in Table 10 reveal clear temporal heterogeneity. During the early adoption phase, ESG performance exhibits a weak and statistically insignificant association with tax avoidance, and the moderating role of institutional quality is limited. This pattern suggests that early ESG practices in developing countries were largely symbolic and insufficient to constrain fiscal behavior, consistent with legitimacy-based disclosure arguments [8,9].

Table 10.

Temporal Heterogeneity in the ESG–Tax Avoidance Relationship.

In contrast, during the mature ESG phase, ESG performance shows a strong and statistically significant negative association with tax avoidance, while the interaction between ESG performance and institutional quality becomes larger and statistically significant. This indicates that, as ESG frameworks mature, institutional quality increasingly amplifies ESG’s disciplining effect on corporate tax behavior. These findings are consistent with recent evidence showing that ESG effectiveness strengthens once sustainability practices are embedded within more credible regulatory and monitoring environments [22,37].

Overall, the temporal analysis demonstrates that the ESG–tax avoidance relationship is dynamic rather than static. ESG commitments constrain aggressive tax behavior primarily in later stages of ESG institutionalization, when sustainability practices move beyond symbolic signaling and acquire substantive governance relevance. This temporal perspective complements the firm-size and regional heterogeneity analyses and reinforces the importance of both institutional context and ESG maturity in shaping corporate tax behavior in developing economies.

6. Discussion

This study provides robust evidence that ESG performance constrains corporate tax avoidance in developing economies, but that this effect is conditional rather than automatic. ESG operates as an effective governance mechanism only when supported by adequate institutional enforcement, organizational capacity, and sufficiently mature sustainability frameworks.

Consistent with H1, firms with stronger ESG performance exhibit significantly lower levels of tax avoidance. This finding aligns with stakeholder and legitimacy theories, which emphasize that sustainability-oriented firms face heightened reputational exposure, ethical expectations, and scrutiny from investors, regulators, and civil society, increasing the expected costs of aggressive tax behavior [3,4,10]. Importantly, the magnitude of the estimated effects indicates economically meaningful reductions in BTD, confirming that ESG commitments translate into substantive fiscal discipline rather than symbolic disclosure alone.

More critically, the results provide strong support for H2 by demonstrating that institutional quality significantly moderates the ESG–tax avoidance relationship. ESG’s constraining effect is substantially stronger in countries characterized by higher regulatory quality, stronger rule of law, and more effective government institutions. This finding is consistent with institutional theory and prior evidence showing that governance environments shape the credibility and behavioral consequences of ESG practices [2,6]. In governance-strong settings, inconsistencies between ESG claims and tax behavior are more visible, more likely to be sanctioned, and therefore more costly, reinforcing alignment between sustainability commitments and responsible fiscal conduct.

The study also helps reconcile mixed findings in prior ESG–tax research. Evidence of weak or insignificant ESG effects in governance-weak contexts—such as Palestine and other emerging markets [8,9]—suggests that ESG may function primarily as a legitimacy signal where enforcement is limited. The present results clarify that ESG effectiveness is context-dependent, explaining why ESG appears impactful in some institutional settings but largely symbolic in others.

The heterogeneity analyses further deepen this interpretation. First, the firm-size analysis shows that the disciplining effect of ESG is concentrated among large firms, which face stronger stakeholder monitoring, greater reputational exposure, and more developed governance capacity. In contrast, ESG performance has no statistically meaningful impact on tax avoidance among smaller firms, consistent with evidence that limited visibility, weaker enforcement intensity, and capacity constraints reduce the behavioral consequences of ESG adoption [5]. This highlights organizational visibility as a key transmission channel through which ESG affects fiscal outcomes.

Second, the pillar-level analysis demonstrates that ESG is not a monolithic construct. The governance and environmental pillars drive the negative association with tax avoidance, while the social pillar plays a limited role. Governance-related ESG mechanisms directly constrain managerial discretion through enhanced transparency and internal controls, consistent with agency theory [4,6,11]. Environmental performance operates through legitimacy and reputational channels by increasing public and regulatory scrutiny [3,10]. In contrast, social initiatives appear less directly linked to fiscal decision-making in developing-country contexts, where social disclosures may remain partially decoupled from core financial strategies [8,9]. These findings confirm that ESG effectiveness is mechanism-specific rather than index-driven.

Third, the regional and temporal heterogeneity analyses show that ESG effectiveness varies across institutional trajectories and over time. ESG exhibits the strongest tax-disciplining effect in Asia and during the mature ESG phase (post-2018), where disclosure standards, regulatory coordination, and stakeholder scrutiny have strengthened. In contrast, ESG effects are weaker or conditional in regions and periods characterized by lower enforcement credibility. Together, these results underscore that ESG operates within region- and time-specific institutional dynamics, not universal governance templates.

Taken together, the consistency of findings across fixed-effects models, dynamic System GMM estimation, instrumental-variable identification, and multiple heterogeneity analyses strengthens confidence in the study’s conclusions. ESG commitments translate into substantive fiscal discipline only when embedded in supportive institutional environments, sufficient organizational capacity, and mature sustainability frameworks.

7. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Given the disproportionate reliance of developing economies on corporate income taxation, this study’s evidence that ESG performance—when reinforced by strong institutional quality—constrains corporate tax avoidance has direct implications for fiscal sustainability and development financing. This study examines how ESG performance and institutional quality jointly shape corporate tax avoidance in developing countries using a multi-country panel of 2464 publicly listed firms (17,424 firm-year observations). Three key conclusions emerge. First, firms with stronger ESG performance engage in significantly lower levels of tax avoidance, indicating that sustainability can function as a meaningful governance mechanism. Second, this relationship is institutionally contingent: ESG is substantially more effective in governance-strong environments, where regulatory quality and enforcement reinforce behavioral alignment. Third, the ESG–tax relationship is heterogeneous, with economically meaningful effects concentrated among large firms and driven primarily by governance- and environment-related ESG dimensions.

These findings carry important policy implications for developing economies. ESG reforms implemented without parallel improvements in institutional quality risk encouraging symbolic compliance rather than genuine fiscal responsibility. In governance-weak settings, sustainability disclosures may enhance legitimacy without constraining aggressive tax practices, underscoring the need for credible enforcement, regulatory coordination, and accountability mechanisms.

More broadly, the study contributes to the ESG, tax governance, and sustainability reporting literature by demonstrating that responsible corporate taxation emerges not only from firm-level sustainability commitments but also from national governance systems and organizational structures. The consistency of results across fixed-effects, dynamic GMM, and instrumental-variable approaches strengthens confidence that the observed relationships reflect substantive governance mechanisms rather than spurious correlations.

From a theoretical perspective, the findings integrate stakeholder, legitimacy, agency, and institutional theories into a coherent framework. Stakeholder and legitimacy perspectives explain why ESG-oriented firms face stronger normative and reputational pressures, while agency theory highlights the role of governance mechanisms in constraining managerial opportunism. Institutional theory clarifies that these pressures translate into substantive fiscal outcomes only when supported by strong governance frameworks that limit symbolic ESG adoption.

- Policy Implications

The results highlight that ESG effectiveness in developing countries depends critically on institutional quality. Strengthening regulatory quality, rule of law, and enforcement capacity is essential for ESG initiatives to translate into meaningful reductions in tax avoidance. Integrating tax transparency indicators into ESG reporting frameworks can further enhance accountability and reduce the scope for sustainability disclosures to function as reputational shields.

Regulatory oversight should also be differentiated by firm size. While large firms exhibit stronger ESG–tax alignment, smaller firms face capacity and visibility constraints. Policymakers can address these gaps through simplified disclosure requirements, targeted compliance support, and digital reporting tools. Finally, closer alignment between national ESG initiatives and international tax governance frameworks—such as the OECD BEPS project and the Global Minimum Tax—can strengthen enforcement and support sustainable development objectives.

- Limitations and Future Research

This study has limitations that open avenues for future research. ESG and institutional quality indicators may not fully capture qualitative differences in sustainability practices or enforcement intensity. The focus on developing countries enhances policy relevance but limits generalizability to advanced economies, suggesting scope for comparative studies. Informal institutions, political connections, and corruption dynamics warrant further examination. Future research could also exploit regulatory shocks or natural experiments to strengthen causal inference.

Overall, the findings demonstrate that ESG performance constrains corporate tax avoidance in developing countries only when supported by strong institutions, sufficient firm-level capacity, and mature sustainability frameworks, underscoring that ESG effectiveness is not inherent but institutionally contingent.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M. and M.A.; methodology, M.M.; software, M.M.; validation, M.M. and M.A.; formal analysis, M.M.; investigation, M.M.; resources, M.M.; data curation, M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.; writing—review and editing, M.M. and M.A.; visualization, M.M.; supervision, M.A.; project administration, M.M.; funding acquisition, not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia [Project No. KFU260269].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study were obtained from Refinitiv Eikon under license and are therefore not publicly available. Data may be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and subject to data provider restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the academic support provided by Amman Arab University and King Faisal University. During the preparation of this work, the authors used QuillBot (version 2025) for assistance in proofreading and enhancing the manuscript’s readability. Following the use of this tool, the authors accurately reviewed and revised the content as necessary. The authors fully assume responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ESG | Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| WGIs | World Governance Indicators |

| BTDs | Book–Tax Differences |

| ETR | Effective Tax Rate |

| Cash ETR | Cash Effective Tax Rate |

| CSR | Corporate Social Responsibility |

| ROA | Return on Assets |

| LEV | Leverage |

| SIZE | Firm Size |

| TANG | Asset Tangibility |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| INF | Inflation |

| FE | Fixed Effects |

| GMM | Generalized Method of Moments |

| 2SLS | Two-Stage Least Squares |

| IV | Instrumental Variable |

| TCFD | Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures |

| NFRD | Non-Financial Reporting Directive |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

Appendix A. Supplementary Information on Sample Construction and Country Coverage

Table A1.

Sample Construction Process (2015–2023).

Table A1.

Sample Construction Process (2015–2023).

| Screening Stage | Number of Firms |

|---|---|

| Initial universe of publicly listed firms | ≈5850 |

| Exclusion of financial institutions | 4980 |

| Exclusion of firms without ESG scores | 3720 |

| Exclusion of firms with missing tax variables | 3050 |

| Minimum data requirement (≥3 consecutive years) | 2640 |

| Removal of implausible/extreme tax observations | 2464 |

| Final analytical sample | 2464 |

Notes: The figures are illustrative and approximate, based on Refinitiv Eikon coverage and ESG–tax avoidance research. The final sample includes 2464 firms from 2015 to 2023, totaling 17,424 firm-year observations.

Table A2.

Country Coverage and Stock Exchanges of Sampled Firms.

Table A2.

Country Coverage and Stock Exchanges of Sampled Firms.

| Country | Main Stock Exchange(s) |

|---|---|

| Brazil | B3 (Brasil Bolsa Balcão) |

| China | Shanghai Stock Exchange; Shenzhen Stock Exchange |

| Colombia | Bolsa de Valores de Colombia |

| Egypt | Egyptian Exchange (EGX) |

| India | Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE); National Stock Exchange (NSE) |

| Indonesia | Indonesia Stock Exchange (IDX) |

| Jordan | Amman Stock Exchange (ASE) |

| Malaysia | Bursa Malaysia |

| Mexico | Bolsa Mexicana de Valores (BMV) |

| Morocco | Casablanca Stock Exchange |

| Philippines | Philippine Stock Exchange (PSE) |

| South Africa | Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) |

| Thailand | Stock Exchange of Thailand (SET) |

| Turkey | Borsa Istanbul |

Notes: All firms are publicly listed non-financial companies from Refinitiv Eikon with valid ESG scores, tax variables, and at least three consecutive years of data from 2015 to 2023.

Table A3.

Distribution of Firms by Country (2015–2023).

Table A3.

Distribution of Firms by Country (2015–2023).

| Country | No. of Firms | Approx. % of Sample |

|---|---|---|

| China | 620 | 25.2% |

| India | 420 | 17.0% |

| Brazil | 280 | 11.4% |

| South Africa | 210 | 8.5% |

| Malaysia | 170 | 6.9% |

| Turkey | 150 | 6.1% |

| Mexico | 130 | 5.3% |

| Thailand | 110 | 4.5% |

| Indonesia | 95 | 3.9% |

| Philippines | 75 | 3.0% |

| Egypt | 70 | 2.8% |

| Morocco | 55 | 2.2% |

| Colombia | 50 | 2.0% |

| Jordan | 29 | 1.2% |

| Total | 2464 | 100% |

Notes: This table shows the country distribution of 2464 publicly listed non-financial firms in the sample, based on Refinitiv Eikon coverage across stock exchanges. The total number of firm-year observations is 17,424 from 2015 to 2023.

References

- Mitroulia, M.; Chytis, E.; Kitsantas, T.; Skordoulis, M.; Kalantonis, P. ESG strategy and tax avoidance: Insights from a meta-regression analysis. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2025, 18, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Ballesta, J.P.; Yagüe, J. Tax avoidance and the cost of debt for SMEs: Evidence from Spain. J. Contemp. Account. Econ. 2023, 19, 100362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider-Maunoury, G.; Bouchacourt, J. Sustainable finance and tax issues: How could advanced ESG analysis deter tax avoidance? J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2025, 18, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, B.; Lee, J.H.; Cho, J.H. The effect of ESG performance on tax avoidance—Evidence from Korea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakhli, A. Do Women on Corporate Boardrooms Have an Impact on Tax Avoidance? The Mediating Role of Corporate Social Responsibility. Corp. Gov. 2022, 22, 821–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgharbawy, A.; Aladwey, L.M.A. ESG performance, board diversity and tax avoidance: Empirical evidence from the UK. J. Financ. Report. Account. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Corporate Tax Statistics 2024; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/tax/corporate-tax-statistics/ (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Jarboui, A.; Kachouri Ben Saad, M.; Riguen, R. Tax avoidance: Do board gender diversity and sustainability performance make a difference? J. Financ. Crime 2020, 27, 1389–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariff, A.M.; Kamarudin, K.A.; Musa, A.Z.; Mohamad, N.A. Financial constraints, corporate tax avoidance and environmental, social and governance performance. Corp. Gov. 2024, 24, 1525–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemiolo, S.; Farnsel, C. Complements, substitutes or neither? A review of the relation between corporate social responsibility and corporate tax avoidance. J. Account. Lit. 2023, 45, 474–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elamer, A.A.; Boulhaga, M.; Ibrahim, B.A. Corporate tax avoidance and firm value: The moderating role of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) ratings. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 7446–7461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Hu, W.; Jiang, P. Does ESG performance affect corporate tax avoidance? Evidence from China. Finance Res. Lett. 2024, 61, 105056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipatnarapong, J.; Beelitz, A.; Jaafar, A. Corporate social responsibility and tax avoidance: Evidence from BRICS countries. Corp. Gov. 2025, 25, 1628–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amara, N.; Bouzgarrou, H.; Bourouis, S.; Alshdaifat, S.M.; Al Amosh, H. The Interaction Effect of Female Leadership in Audit Committees on the Relationship between Audit Quality and Corporate Tax Avoidance. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2025, 18, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qutait, Z.; Salem, S. The role of corporate social responsibility in the tax avoidance of Palestinian companies. Asian Rev. Account. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solikhah, B.; Chen, C.L.; Weng, P.-Y.; Al-Faryan, M.A.S. Related party transactions and tax avoidance: Does government ownership play a role? Corp. Gov. 2025, 25, 763–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai, H.M.; Dang, K.N.; Nor, N.M.; Nguyen, H.T.; Nguyen, K.V. Corporate tax avoidance and stock price crash risk: The moderating effects of corporate governance. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2025, 20, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, T. Relationship between corporate social responsibility and tax avoidance: International evidence. Soc. Responsib. J. 2019, 15, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpa, F.; Signori, S. Understanding Corporate Tax Responsibility: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2023, 14, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannarou, L.; Tzeremes, P. CSR performance and corporate tax avoidance in the hospitality and tourism industry: Do women directors moderate this relationship? Int. Hosp. Rev. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, W.; Meng, Q.; Cao, Y.; Liu, J. Impact and moderating mechanism of corporate tax avoidance on firm value from the perspective of corporate governance. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2025, 99, 103926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.M.; Lee, S.J. ESG controversies and corporate tax avoidance. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2025, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, R.; Bond, S. Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. J. Econom. 1998, 87, 115–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.; Anwar, W.; Zahir-Ul-Hassan, M.K.; Ahmed, A. Corporate Governance and Tax Avoidance: Evidence from an Emerging Market. Appl. Econ. 2024, 56, 2688–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koay, G.Y.; Sapiei, N.S. The role of corporate governance on corporate tax avoidance: A developing country perspective. J. Account. Emerg. Econ. 2025, 15, 84–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Yim, S.; Zhang, L. The cost of ESG rating disagreement: Increased corporate tax avoidance in China. Int. Tax Public Financ. 2025, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Xu, C.; Zhan, W.; Lin, G.; Schneider, F. Like adding oil to the fire or pouring water on it? The effect of the digital economy on corporate tax avoidance: Evidence from China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2025, 212, 123936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Han, J.; Işık, C. Can digital transformation be a “powerful tool” to curb corporate tax avoidance? Mechanism analysis and policy implications based on Chinese data. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 102, 104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Zhang, M.; Guo, X.; Jiang, Y. ESG disclosure and firm long-term value: The mediating effect of tax avoidance. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 83, 107728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersten, L.F.; Qari, S. The association between gender diversity of companies’ executives and corporate tax avoidance. Corp. Gov. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Jiawei, G.; Jebran, K. CFO status in TMT informal hierarchy and corporate tax aggressiveness. Rev. Quant. Financ. Account. 2025, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]