Abstract

Phytoremediation is a cost-effective and sustainable method for the remediation of minewaste contaminated with heavy metals such as arsenic (As). However, mine waste soil is often nutrient-limited, especially in nitrogen (N), impairing plant growth and phytoremediation. This study aimed to assess how planting density together with soil amendments, biochar, and an isolated indigenous nitrogen-fixing bacterium (NFB) (Bacillus subtilis) affect the efficacy of phytoremediation by Juncus pauciflorus of an As-contaminated mine waste soil from Bendigo, Victoria. Three plant densities, including 9, 26, and 44 plants/m2, were grown in As-contaminated mine waste soil amended with biochar (10% w/w) and B. subtilis (8.1 × 108 CFU/mL) and incubated for 100 days. Plant biomass, plant As uptake, soil As concentration, bacterial abundance (total and NFB using 16S and nifH gene copy numbers, respectively), and total soil N were assessed. Juncus pauciflorus at a higher density (44 plants/m2) promoted the greatest biomass and total As uptake, 70.22 g/m2 and 209.53 mg/m2, respectively. Plant density significantly influenced the root–shoot partitioning of As. Higher densities increased shoot uptake (BAFsoil→shoot), and TFroot→shoot values remained >1 across all treatments, confirming the active translocation of As to the shoots, suggesting both phytostabilisation and phytoextraction potential by J. pauciflorus. Planting density significantly reduced soil As, ranging from 8000 mg/kg to 9500 mg/kg, compared to the initial concentration (13,032 mg/kg). The abundance of 16S and nifH genes was stable among treatments, ranging from 7 log10 copies/g to 12 log10 copies/g. TN content in soils amended with 44 plants/m2 contained the highest TN content at day 33, approximately 7000 mg/kg. This study is the first to report that higher planting density of J. pauciflorus amended with biochar and NFB provides the strongest phytoremediation performance in highly As-contaminated mine soil by enhancing As uptake and accumulation in aboveground biomass. Most importantly, the results show that plant density also regulates the plant’s remediation strategy, shifting J. pauciflorus between phytostabilisation at dense planting and greater phytoextraction at lower density. These findings support the use of native plants in combination with biochar and microbial amendment as a sustainable strategy for remediating As-contaminated mine waste.

1. Introduction

Arsenic (As) contamination at mining sites is of widespread environmental concern. Recent research confirms that mining and mineral processing are the key sources of As release into the environment [1,2]. The anthropogenic annual release of As into the environment is reported to be in the range 1500–5600 × 109 g, significantly exceeding the natural rates of As release through weathering, which range between 60 and 44 × 109 g/year [3]. Significant amounts of waste materials, residues, and excess soil are produced and typically discarded in open areas through mining activities. Leaching of As from these materials causes contamination in the surrounding soil, with As concentrations often exceeding thousands of mg/kg [2,4]. For example, in Chile, mine tailings from semi-arid regions contain up to 36,000 mg/kg [5], while As concentrations of 47,000 mg/kg have been reported in gold mine tailings in Victoria, Australia [6]. These As-contaminated mine soils threaten ecosystems and human health through water sources, food chains, and directly impact the growth and activities of both plants and the soil microbial community [7,8]. Long-term exposure to As can cause health effects to humans, including skin lesions, cardiovascular disorders, and various cancers [9]. Arsenic exposure to plants can reduce the synthesis of chlorophyll, disrupt photosynthesis, decrease biomass yield, and thus restrict plant productivity in contaminated mine soils [10,11]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to remediate these As-contaminated mine wastes.

Multiple remediation approaches have been explored for As-contaminated mine soils, including electrokinetic extraction, soil washing, and chemical stabilisation. However, those methods often require high cost, intensive labour, create secondary contamination and change soil properties. Recent studies have demonstrated that phytoremediation can be effectively applied to reduce As-contaminated mine waste. This eco-friendly and cost-efficient method utilises plants to absorb As from the soil and involves phytoextraction and phytostabilisation in the remediation process [12,13]. Phytoextraction refers to the process of contaminant absorption from soil and translocation to the above-ground parts of the plant, while phytostabilisation is the process of stabilising contaminants in the soil by plant roots. The effectiveness of phytoremediation applications has been previously reported in As-contaminated mine soil. For example, Pteris vittata and Brassica juncea have shown a high capacity for phytoextraction by accumulating As up to 2000 mg/kg in their fronds and shoots. However, although phytoremediation has been effectively applied, plant growth is frequently inhibited by nitrogen (N) deficiency in mine soils, which are lower than the normal soil range, varying from 500 to 20,000 mg/kg [14,15,16]. Nitrogen is an essential macronutrient required for plant growth in significant amounts (approximately 1000 µg N/kg of dry matter) [17]. Native plant species are commonly chosen for phytoremediation due to their inherent adaptation to local soil and climate conditions, which promotes greater metal stress tolerance and more stable long-term establishment [18,19].

Adding soil amendments, such as biochar and/or nitrogen-fixing bacteria (NFB) like Bacillus subtilis, has been used to enhance soil N content [20,21]. Biochar refers to a carbon-rich solid product formed through biomass pyrolysis and gasification under oxygen-restricted conditions, exhibiting high stability characteristics that can persist in the soil for an extended period [22,23,24]. The application of biochar to soils has gained increasing interest due to its capacity to improve soil fertility, including soil N [25,26]. A previous study showed that biochar increased N content from 27.5 mg/kg to 29.8 mg/kg after biochar addition in an abandoned As mine site [27]. In addition, biochar has been known to elevate microbial activity and stabilise heavy metals [28]. Bacillus subtilis, a nitrogen-fixing bacterium (NFB) that lives freely or is associated with the rhizosphere of plants, has been used as an inoculant to increase soil N availability through the conversion of atmospheric N (N2) to ammonia (NH3), which can be utilised by plants [29,30]. Previous studies have demonstrated that B. subtilis can be applied to increase N in conjunction with biochar. For example, Ibrahim et al. [31] found that co-applying biochar and Bacillus spp. promoted long-term N supply. Furthermore, combined applications of biochar and B. subtilis increased ammonia nitrogen (NH4-N) in soil by 53.16% [32]. Co-applying biochar and Bacillus subtilis have not only increased soil fertility and N content but has also significantly enhanced phytoremediation efficiency in metal-contaminated soils [13,33,34].

Another factor that is important in determining the efficacy of any phytoremediation process, especially in the initial 12-month period of establishment, is planting density. To date, few studies have examined the impact of planting density on As phytoremediation. Most previous studies have focused on selecting suitable plants, such as Pteridium aquilinum, Corrigiola telephiifolia, Cyperus exaltatus [35], and Juncus pauciflorus [13], or using different soil amendments, such as biochar, compost, and iron [13,36], rather than assessing how planting density affects As phytoremediation. Investigating plant density is crucial to achieving better outcomes of phytoremediation, particularly during pilot or full commercial applications. Higher plant density can increase root biomass production, rhizosphere interactions, and contaminant accumulation [37,38]. However, excessive density can lead to nutrient competition among plants, resulting in limited individual plant growth and ineffective phytoremediation [38,39].

This study examines the impacts of different densities of J. pauciflorus on the phytoremediation of As-contaminated mine waste amended with biochar with B. subtilis. Juncus pauciflorus has been previously reported to effectively remediate As-contaminated mine waste amended with biochar, presenting an approximately twofold increase in overall plant biomass and approximately 35% higher As uptake per plant [13]. This study aims to assess the impact of planting density of J. pauciflorus for As phytoremediation by assessing total As uptake. In addition, the impact of the treatment on plant biomass, soil total nitrogen (TN) and soil microbial abundance was investigated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Soil, Plant, and Biochar Collection

The mine waste soil was obtained from a former mine site in Bendigo, Victoria, Australia (36.76121° S, 144.24190° E). Arsenic concentration in the collection site has been previously reported, reaching between 2230 and 18,000 mg/kg [40]. Soil As concentrations were analysed before use (see Section 2.2). Mine waste soil (40 kg) from a depth of 0–50 cm was collected, placed in sterile and sealed containers and taken to the laboratory for further processing. Before use, soil samples were maintained at 4 °C. Biochar was kindly donated by Barwon Water, produced from Logan City’s biosolids gasification facility.

Juncus pauciflorus was purchased from Regen Nurseries in Bangholme, Victoria, Australia. The plants were purchased in tube stocks at the same growth stage.

2.2. Pre-Assessment Soil and Biochar Characteristics

2.2.1. pH

pH of soil and biochar was determined using a HANNA Instruments edge pH meter (Keysborough, Victoria, Australia). A ratio of 1:10 w/v was prepared by diluting 1 g of soil/biochar with 9 mL of Milli-Q deionised water. The solution was shaken for 24 h at room temperature before measurement, conducted in triplicate. Table 1 reports the pre-assessment analysis of the soil and biochar.

Table 1.

Pre-assessment of soil and biochar characteristics.

2.2.2. Arsenic

The As concentration of dried, sieved soil (<2 mm) was assessed using the US EPA method 3050B [41]. In brief, 1 g of soil was added to 10 mL HNO3 (70%) in a covered glass, then heated to 95 °C until no further brown fumes were visible. An aliquot (2 mL) of water was added, followed by H2O2 (30%, 3 mL); the solution was then diluted to 50 mL with Milli-Q water and filtered using a 0.45 µm filter before ICP-MS analysis [42].

2.2.3. Total Nitrogen

Total nitrogen (TN) kits from HACH (2672245-AU) (Loveland, Colorado, USA) were used to determine TN content in soil. A 1:10 ratio of soil/biochar and Milli-Q water was used, with analysis conducted in triplicate. The kits used ranged from 1–25 mg/L N, with the test conducted following Method 10071.

2.2.4. Soil Texture

Soil texture was identified using RemScan (Ziltek Pty. Ltd., Edwardstown, SA, Australia), which applied calibration models relating MIR spectra to reference sand and clay fractions [43,44].

2.2.5. Organic Matter

Samples were allowed to dry naturally, processed to <2 mm and subsequently dried at 105 °C before analysis until a constant weight was achieved. Following drying, a muffle furnace was used to heat the samples at 550 °C for 2 h. Organic matter (OM) content was calculated from the mass loss after ignition and reported as a percentage of the dry soil weight:

where W1 is the oven-dried soil weight, and W2 is the weight after ignition.

2.3. Isolation of Nitrogen-Fixing Bacteria from Mine Waste Soil

Nitrogen-fixing bacteria (NFB) were isolated from mine soils using Jensen’s selective agar media (HiMedia, India). Mine soil (1 g) was diluted in 9 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 0.01 M), followed by serial dilution. All plates were incubated at 30 °C for 8 days. All colonies were re-cultured for purification.

2.4. Extraction of DNA from Nitrogen-Fixing Bacterial Isolates and Identification of nifH Genes from Nitrogen-Fixing Bacteria Using PCR

A PowerSoil® DNA Isolation Kit (MO BIO Laboratories, Inc., Carlsbad, CA USA) was utilised to extract the DNA from the bacterial isolates, following the manufacturer’s protocol. All 29 pure NFB isolates were screened for the presence of the nifH gene. The nifH gene is a well-known indicator for NFB. Primers Ueda 19F (5′GCIWTYTAYGGIAARGGIGG3′)/Ueda 407R (5′AAICCRCCRCAIACIACRTC3′), nifHF (5′TACGGNAARGGSGGNATCGGCAA3′)/nifHI (5′AGCATGTCYTCSAGYTCNTCCA3′), and nifH2f (5′GAAGGTCGGCTACCAGAACA3′)/nifH5r (5′AAGTTGATCGAGGTGATGACG3′) were utilised. PCR amplifications were carried out in 25 µL reaction volumes containing 12.5 µL of PCR Master Mix, 1 µL of each primer, 2 µL of NFB DNA, and 8.5 µL of nuclease-free water. Thermal cycling comprised an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 2 min, 25 cycles of denaturation (94 °C, 30 s), annealing (60 °C, 30 s), and extension (72 °C, 30 s), followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. After PCR products were obtained, 1.5% agarose powder (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was prepared for gel electrophoresis, using 90 V for 30 min. The BIO-RAD ChemiDoc system was used to visualise the gel product.

2.5. Identification of Nitrogen-Fixing Bacteria Using MALDI-TOF

Once the nifH genes were detected in the bacterial isolates, the isolates were identified using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) (Bruker Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA), based on the MALDI Biotyper Compass Library (version 2022). Colonies obtained from fresh cultures were placed on the target plate, then treated with 1 µL of 70% formic acid and allowed to dry. Following drying, the matrix solution (1 µL) was added and dried completely. The plate was then inserted into the MALDI-TOF instrument for identification.

2.6. Preparation of NFB Culture

A single colony of the refreshed isolate was cultured in nutrient broth (50 mL in a 100 mL Erlenmeyer flask) at 28 °C overnight with shaking at 150 rpm until exponential growth was achieved. Cells were pelleted at 8000× g for 25 min at 4 °C; the pellet was washed twice with sterile distilled water and resuspended to a final density of 8.1 × 108 CFU/mL (OD600 = 0.5) [45,46].

2.7. Mesocosm Experiment

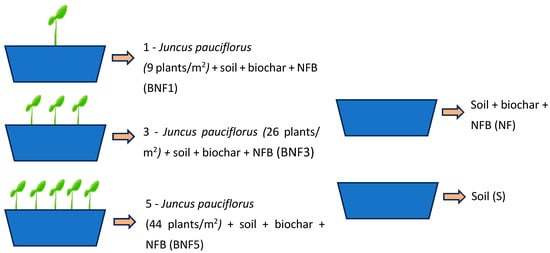

Mesocosms (60 × 19 × 16 cm) were filled with 18 kg of As-contaminated soils and thoroughly mixed with 10% biochar (w/w). NFB suspension was added at approximately 900 mL per pot, and the soil was thoroughly mixed. Plants from tube stock with different densities, 9, 26, and 44 plants/m2 (labelled BNF1, BNF3 and BNF5, respectively) were transplanted into mesocosms containing mine soil, biochar, and NFB. Control mesocosms were also prepared containing (i) no plants, only biochar and NFB (NF), and (ii) unamended soil only (S), with both controls amended with 900 mL of water and mixed (Figure 1). Mesocosms were established in triplicate (n = 3) and incubated in a greenhouse for 100 days, with regular watering; soil moisture was adjusted to about 80% of the maximum water-holding capacity. To analyse As concentration and other soil properties, soil samples were collected from each pot at four time points (0, 33, 67, and 100 days). Biomass and As uptake were reported both per plant and per unit area. Mesocosm values were converted to m2 by normalising to the surface area of each pot (0.114 m2).

Figure 1.

Illustration of the experimental design. BNF1: 9 plants/m2, added with biochar and NFB, BNF3: 26 plants/m2, added with biochar and NFB, BNF5: 44 plants/m2, added with biochar and NFB, NF: biochar and NFB, S: soil.

2.8. Measurement of Plant Biomass

After 100 d incubation, plants were carefully removed, and soil particles attached to the plant surface were removed by washing with tap water. All shoots and roots were then separated and subsequently rinsed with deionised water before the analysis. Shoots and roots were dried for 72 h at 60 °C before further processing and repeatedly weighed until a constant weight was obtained.

2.9. Determination of Arsenic Concentration in Plants

ICP-MS (Agilent 7700c, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was utilised to measure As concentrations in plants. Before analysis, dried plants were ground with a mortar and pestle. As concentrations were determined using the method described by Cai, Georgiadis [47], with modifications. Briefly, 0.1 g of dried shoots and roots were placed into glass tubes, and 70% HNO3 and 30% H2O2 (10 mL aliquot) were added. The solutions were then diluted with Milli-Q water (40 mL) and filtered using a 0.45 µm nylon syringe filter (25 mm diameter; FilterBio®, Nantong City, Jiangsu, China) before analysis by ICP-MS using US EPA method 6020B [42]. Peach leaves NIST 1547 from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), and blanks were used for quality assurance and quality control.

2.10. Determination of Arsenic Concentration in Soils

Arsenic concentration in soils post-treatments was assessed using the same method as previously described in Section 2.2.2.

2.11. Determination of Bioaccumulation Factor (BAF) and Translocation Factor (TF)

Two coefficients, the bioconcentration factor (BAF) and translocation factor (TF), were used to describe arsenic phytoremediation behaviour, including phytoextraction and phytostabilisation mechanisms. The BAF was calculated to assess the accumulation of As from soil into plant tissues (Equation (1)), whereas the TF was used to evaluate the translocation of As from roots to shoots (Equation (2)):

2.12. Soil Bacterial Analysis

2.12.1. DNA Extraction

SPINeasy® DNA Pro Kits for soil (MP Biomedicals, CA, USA) were used to extract DNA from soil, following the instructions from the manufacturer. The rhizosphere was collected by shaking the soil adhering to the plant root surface. Before extraction, soil and rhizosphere were homogenised using Fastprep® at 6 m/s for 40 s. To measure DNA quality and quantity, a NanoDrop Lite spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used. Samples were kept at −20 °C for further analysis.

2.12.2. Quantification of 16S and nifH Gene

Quantification of total bacterial (16S) and nitrogen-fixing bacterial (nifH) abundance was performed using quantitative PCR (qPCR) in a QIAGEN Rotor-Gene machine (Qiagen, Venlo, Limburg, The Netherlands). The selected primer pair 341-F (5′CCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG3′) and 518-R (5′ATTACCGCGGCTGCTGG3′) was applied to quantify 16S [48], while nifHF (5′TACGGNAARGGSGGNATCGGCAA3′) and nifHI (5′AGCATGTCYTCSAGYTCNTCCA3′) were used for the nifH gene [49]. qPCR was performed in a 20 µL reaction volume comprising 10 µL of qPCR master mix (SensiFAST SYBR No-ROX Kit, Bioline, Heidelberg, Germany), 8.2 µL of PCR-grade water, 1 µL of DNA template, and 0.4 µL of each primer [48].

2.13. Data Analysis

The data were analysed using R (version 2023.12.1+402). Before the analysis, data were examined for normality and homogeneity of variance. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD was applied for parametric data, while the Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s post hoc test was used for non-parametric data. A significant level of p < 0.05 was applied.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Identification of Nitrogen-Fixing Bacterial Isolates from Mine Soil

Nitrogen-fixing bacteria (NFB) were isolated from soil using Jensen agar medium, resulting in 29 purified isolates. PCR analysis and gel electrophoresis revealed that 4 of these isolates possessed the nifH gene and were identified as Bacillus subtilis. These four isolates were subsequently used in greenhouse experiments.

3.2. Plant Growth in Mine Waste

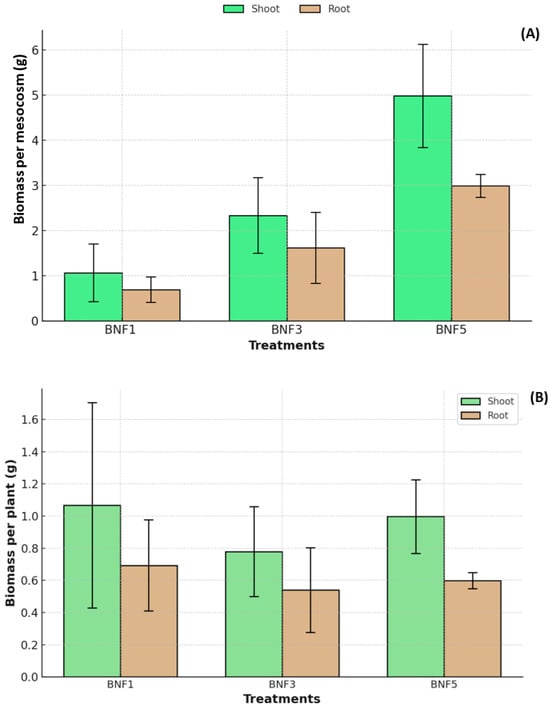

After 100 days, all plants in all treatments grew, with plants from all treatments showing significantly higher shoot biomass compared to root biomass (Figure 2A). However, after 100 days of incubation, Juncus pauciflorus showed significant differences in biomass among treatments (p < 0.05). Total plant biomass in mesocosms was, as expected, highest in the densest planting density treatment (44 plants/m2, BNF5) for both shoot (4.99 g/mesocosm) and root (2.99 g/mesocosm). In comparison, lower plant densities (9 plants/m2 and 26 plants/m2) produced lower shoot and root biomass, 2.34 g/mesocosm and 1.10 g/mesocosm and root biomass of 1.62 g/mesocosm and 0.69 g/mesocosm, respectively (Figure 2A). However, there were no significant differences in shoot, root, or total biomass per plant among planting density treatments (p > 0.05) (Figure 2B). This result confirmed, as expected, that higher plant density (44 plants/m2) significantly improved plant biomass per m2 when the soil was amended with biochar and B. subtilis. The higher number of individual plants in the mesocosm may be a key factor in increasing biomass in BNF5. The results indicate that each plant survived and grew well at all three plant densities, with no evidence of any reduced growth due to excessive competition among plants and the highest plant density. This result suggests that the combination of biochar and B. subtilis promoted a suitable microenvironment for plants to grow and survive by supplying sufficient nutrients.

Figure 2.

(A) Total biomass of shoot and root of Juncus pauciflorus per pot after 100 days among treatments. (B) Total biomass of the shoot and root of Juncus pauciflorus per plant after 100 days among treatments. BNF1: 9 plants/m2, BNF3: 26 plants/m2, BNF5: 44 plants/m2. The bars represent mean and standard deviation (n = 3). The other treatments (S and NF) were excluded because no plants were planted.

Biochar plays vital roles in increasing soil porosity, retaining water, and providing surfaces for microbial colonisation [50]. Bacillus subtilis contributes to N fixation and phytohormone secretion, which can stimulate root growth [51]. Both biochar and B. subtilis may have contributed to increased N availability and microbial activity in the rhizosphere, which can reduce resource competition among plants and potentially improve nutrient circulation in the mesocosms due to the denser root system [52,53,54]. This result confirms that increasing plant density has the potential to be an effective strategy to improve the productivity of biomass during phytoremediation under biochar and bacteria treatment.

Previous studies have reported varying outcomes regarding the effects of plant density on phytoremediation in contaminated soil. For example, Qin et al. [37] used different plant densities of Festuca arundinacea: 10, 15, 20, 25, 30 g seeds/m2 for the phytoremediation of Cd-polluted soil. They reported that plant biomass increased as planting density increased; however, plant biomass decreased significantly after reaching an optimum peak at 20-plant/m2 density. Another study was conducted using a high density of Eucalyptus globulus (2500, 5000, and 10,000 plants/ha). The result showed that higher plant density decreased shoot and root biomass, from 4.06 kg/plant to 1.98 kg/plant. In addition, Zheng et al. [55] studied the impacts of plant density (1, 3, 6 individuals per pot) on Trifolium repens with and without biochar on Cd-contaminated soil. They found that 3-plant density was the best treatment to promote biomass with biochar application. In the current study, higher density significantly increased biomass yield, highlighting that this may be a key parameter for future work on As-phytoremediation.

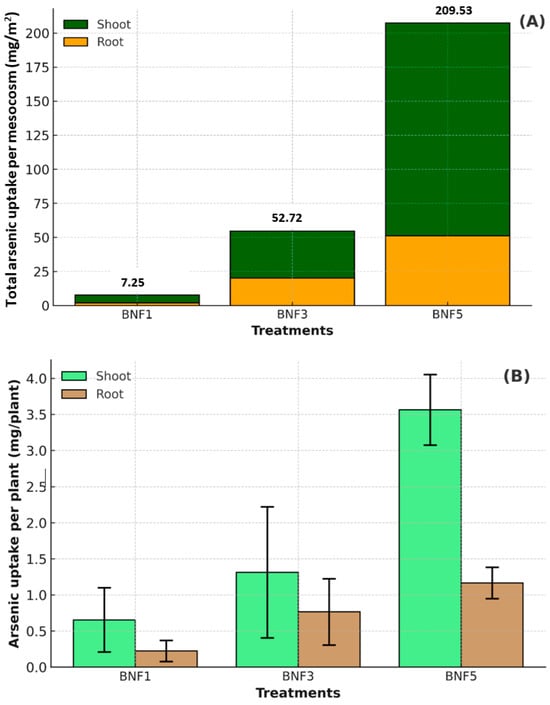

3.3. Arsenic Concentration in Plants and Total As Uptake

Figure 3 illustrates the total As uptake in the shoot and root per m2, as well as As concentration per plant. The results confirm that the total As uptake increased significantly (p < 0.05) with increasing plant density (Figure 3A). The greatest total As uptake (209.5 mg/m2) was observed in mesocosms containing 44 plants/m2 (BNF5), followed by mesocosms with 26 plants/m2 (BNF3) (52.7 mg/m2) and 9 plants/m2 (BNF1) (7.3 mg/m2). This result shows that a higher number of plants promoted a significantly higher cumulative As uptake per m2. Individual As uptake per plant is presented in Figure 3B, which also increased with higher density. BNF5 (44 plants/m2) exhibited the highest accumulation of As in shoots (≈3.5 mg/plant) and (≈1.2 mg/plant) in roots. Although higher plant density may cause competition among individual plants, the elevated rhizosphere volume and combined activity of microorganisms likely enhanced the ability of each plant to accumulate more As [56,57].

Figure 3.

(A) Total arsenic uptake (mg/m2) in shoot and root of Juncus pauciflorus grown under three planting densities (9 plants/m2, 26 plants/m2, 44 plants/m2). The values represent the total As uptake per mesocosm, converted to an area basis. (B) Arsenic concentration (mgperplant) in shoot and root of J. pauciflorus. The values represent the mean uptake per individual plant within each mesocosm. The data are presented as means ± standard deviation (n = 3). Treatments without plants (S = soil, NF = B. subtilis) were excluded since no plant biomass was present for uptake analysis.

Limited studies have investigated the influence of planting density on As uptake during phytoremediation. Lim et al. [58] found that planting density did not affect As accumulation in Eruca sativa. However, they did not specify the actual planting density, comparing only low-density and high-density. Another study used five densities (10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 g seeds/m2) of Festuca arundinacea in Cd-polluted soil. They found that the density of planting can affect the ratios of various leaf types, with the greatest accumulation of Cd observed in senescent and dead leaves recorded at a density of 20 g seeds/m2 [37]. Among those studies, soil amendments were not used. This current study is the first to highlight that higher plant density effectively enhances As uptake with the addition of amendments (biochar and NFB).

Importantly, the relative distribution of As within shoot and root was influenced by planting density. BNF1, with the lowest density (9 plants/m2) and BNF3, with an intermediate density (26 plants/m2), showed a balanced distribution of As between shoot and root. In contrast, the highest planting density (BNF5, 44 plants/m2) resulted in greater As accumulation in shoot (76%) relative to root (24%). These trends suggest that higher plant density affects the pathway of J. pauciflorus in accumulating As internally, with increasing densities creating an enhancement of As concentration in above-ground biomass under biochar and B. subtilis amendments.

In this study, the highest As concentration was observed in the shoot rather than in the root. However, a previous study showed that pots containing a single J. pauciflorus amended with biochar exhibited greater As accumulation in the root rather than in the shoot, indicating a phytostabilisation pathway [13]. Increased plant density and rhizosphere activity may be a crucial factor affecting the As accumulation pathway in plants. The higher plant density used in this current study increased overall root surface area and extended the rhizosphere volume, which may facilitate microbial activity and As mobilisation. This process may promote more soluble As (III) to be translocated to the above-ground part of the plant, resulting in higher As concentration in shoot, indicating a phytoextraction pathway [59,60]. To the best of our knowledge, this shift in the As accumulation pathway from phytostabilisation to phytoextraction has not been previously reported. A change in the As distribution pathway has notable ecological implications. Higher As accumulation in shoot could increase the risk of trophic transfer if ingested by herbivores or detritivores. This study shows that As concentration in plant shoot at all plant densities ranges from approximately 500 mg/kg to 3500 mg/kg, all of which significantly exceed the accepted limit of As for animal feed (2 mg/kg) [61]. This high value of As in plant shoot could be harmful to herbivores and might present significant ecological risks if ingested. Therefore, an appropriate post-harvest management grazing exclusion of the application of J. pauciflorus is required. The biomass of the aboveground parts with high As concentration should be harvested and removed to minimise the potential for secondary contamination.

3.4. Bioaccumulation Factor (BAF) and Translocation Factor (TF)

In this study, the Bioconcentration Factor (BAF) and Translocation Factor (TF) were measured as indicators of phytostabilisation and phytoextraction pathways in contaminated soils. The ability of plants to accumulate As from soil into root or shoot is indicated by BAF, whereas TF represents the translocation of As from root to shoot. These two coefficients are crucial to assess whether a plant primarily retains As in its root or transports it to its shoot. In general, if both BAF and TF values are <1, the plant generally accumulates metal in its root; this mechanism is known as phytostabilisation. In contrast, BAF and TF values >1 indicate enhanced metal uptake and partial translocation to aboveground tissues, which are commonly associated with phytoextraction processes [62].

Table 2 presents the BAF for both shoot and root, as well as the TF across various planting densities. All treatments showed BAF < 1, with the highest BAF (soil → shoot) observed at the highest plant density (44 plants/m2, 0.403), significantly greater than the BAF values obtained from BNF1 (9 plants/m2, 0.072) and BNF3 (26 plants/m2, 0.175). However, TF (root → shoot) in all treatments exceeded 1, with the TF value from BNF1 being the greatest (2.115). This indicates that BNF1 (9 plants/m2) exhibited higher translocation efficiency of As from root to shoot compared to plants grown at higher densities. At lower plant densities, reduced root competition may have enhanced the efficiency of As translocation to the shoot. This interpretation is consistent with the established theory, suggesting that lower root density elevated the efficiency of ion uptake and increases the transfer of substances through the xylem to the upper parts of the plant [63]. Although BNF5 (44 plants/m2) had the highest total As in the shoot, this was primarily due to its much larger shoot biomass. However, when expressed as a ratio (TF), As translocation efficiency declined with increasing plant density compared to the low-density treatment. The dense root may have inhibited the transport of As from root to shoot, promoting greater As retention within the root [64,65].

Table 2.

Variation in BAF and TF among planting densities. Results are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3), with different letters indicating significant differences between treatments within the same column. NF and S treatments were excluded from BCF and TF analyses due to the absence of plant growth (non-planted controls).

Juncus pauciflorus, grown individually in 1 L pots (≈0.0133 m2/plant) and amended with biochar, was previously investigated for its capability to remediate As-contaminated mine waste. The study showed that both BAF and TF values were <1, indicating a dominant phytostabilisation mechanism [13]. In contrast, the present study showed that increasing planting density (9–44 plants/m−2) led to higher BAF values for both soil-to-shoot and soil-to-root pathways. However, although TF values remained above 1, they did not exhibit a consistent increase with planting density. TF values > 1 indicate partial As translocation from root to shoot. However, the relative enhancement of phytoextraction-related behaviour at higher planting densities is driven by greater shoot biomass rather than higher translocation efficiency. Enhanced As translocation to aboveground tissues may be supported by increased nutrient and water uptake induced by biochar and NFB, which boost root metabolism, microbial activity, and xylem transport [66].

3.5. Arsenic Concentration in Soil

Arsenic concentration in soil in all treatments was examined throughout the plant incubation period to determine whether plant density under biochar and B. subtilis addition influences overall As level in soil. At day 100, As concentrations in all amended soils were significantly reduced relative to the unamended control (S) (13,032 mg/kg). Among the treatments with amended soil, the lowest As concentration (8000 mg/kg) was observed in the treatment with low density, 9 plants/m2, followed by 9000 mg/kg in 44 plants/m2, 9300 mg/kg in 26 plants/m2, and the NF treatment containing only biochar and B. subtilis (9500 mg/kg).

The reduced As concentration in all amended treatments compared to the control treatment is potentially due to the biochar properties and microbial activity, in addition to plant density. Biochar immobilises As in contaminated soils by offering a large specific surface area, a porous structure, and diverse functional groups that adsorb As, thereby decreasing its mobility and bioavailability [67]. Additionally, microbial activity linked to the amendments can alter soil pH and redox conditions, which in turn impact As distribution and retention in the soil [68,69,70]. No significant differences in soil As concentrations could be observed between treatments (Table 3). This may be due to heterogeneity in As concentrations within the soil. This would be expected when contaminated soil is contaminated rather than being spiked with As post-sampling.

Table 3.

Arsenic concentration in soil at day 100 of plant incubation. Values are means ± standard deviation (n = 3). Different letters within a column indicate significant differences among treatments.

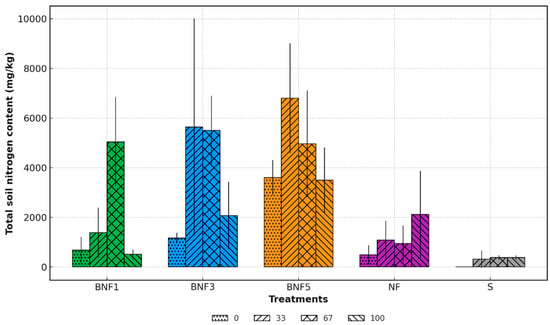

3.6. Total Nitrogen (TN) Content in Soil

Total Nitrogen (TN) in soil was measured to determine the impact of plant density, biochar, and B. subtilis amendments on N retention. It was expected that greater plant density would increase soil TN content because of root activity and microbial activity, consistent with previous reports indicating enhancement of soil nutrient levels and alteration of microbial community under high planting density. Significant differences were detected among treatments and within treatments across the period (p < 0.05) (Figure 4). Treatments with the highest plant density (44 plants/m2, BNF5) produced the highest TN content at day 33, approximately 7000 mg/kg, followed by BNF3 (26 plants/m2), 5500 mg/kg, while the control unamended soil (S) indicated low stable values ( ̴ 400 mg/kg). Across all treatments, TN increased from day 0 to 33 and 67, followed by a decline at day 100. The significant increase suggests N fixation occurring in mesocosms amended with B. subtilis and/or the release of bound N from the biochar. Interestingly, treatment NF, which only contains biochar and B. subtilis without plants, retained N in the soil, which resulted in consistently high soil TN at day 100. This study highlights the synergistic effect of B. subtilis and higher plant density, which may have enhanced root exudation and microbial activity that elevated soil TN. Overall, this study confirms that J. pauciflorus with biochar and B. subtilis amendments can increase TN in mine waste soil.

Figure 4.

Total Nitrogen (TN) content among treatments over time of incubation. BNF1: 9 plants/m2, BNF3: 26 plants/m2, BNF5: 44 plants/m2. The data are presented as the mean (n = 3). The error bar represents standard deviation.

Limited studies have demonstrated the effects of plant density in enhancing soil TN, especially when amended with biochar and NFB. However, several studies relate to our findings. For example, different densities of 1, 3, and 6 of Trifolium repens were applied with the addition of biochar in Cd-contaminated soil in pots with dimensions 54 cm long × 28 cm wide × 5 cm deep, which were equivalent to approximately 6.6, 19.8 and 39.7 plants/m2. The result revealed that soil TN significantly increased with denser plant density (three and six plants) [55]. This study supports the current findings that increasing plant density increases soil TN (Figure 4).

3.7. Abundance of 16S Gene and nifH Gene in Soil and Rhizosphere

Mine soils used in this study contain high As concentrations and limited N availability, which can impact the size and nature of the soil bacterial community. To evaluate the size of the general bacterial composition, 16S rRNA was measured, while nifH gene abundance was assessed to evaluate the presence of nitrogen-fixing bacteria populations under limited N conditions.

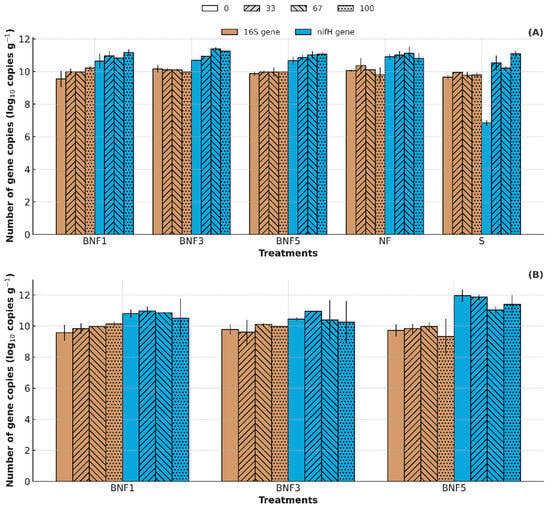

Figure 5 illustrates the number of copies of 16S and nifH genes in soils and rhizosphere during four sampling times. The abundance of the 16S rRNA gene in both soil and rhizosphere remained stable across treatments and sampling days (9.5–10 log10 copies/g), indicating that there was no significant change in overall bacterial populations. In contrast, the abundance of nifH gene was higher, ranging between 7.8 and 12 log10 copies/g. nifH abundance was consistently highest in the rhizosphere in BNF5, with the higher plant density (44 plants/m2), while 16S abundance again remained unchanged. This trend highlights that the population of NFB were more responsive to planting density and amendments than the total bacterial community.

Figure 5.

(A) 16S and nifH gene abundance in soil. (B) 16S and nifH gene in the rhizosphere. BNF1: 9 plants/m2, BNF3: 26 plants/m2, BNF5: 44 plants/m2. The data are presented as the mean (n = 3). The error bar represents standard deviation.

The higher nifH abundance may be due to the influence of biochar and B. subtilis amendments, which are known to support diazotrophic populations [29,71]. However, it should be noted that nifH gene abundance reflects the overall diazotrophic microbial community and does not specifically confirm the survival or activity of the inoculated B. subtilis strain, as strain-specific markers were not used in this study. The higher response in the higher planting density suggests that planting density with the addition of these amendments played a role in promoting the presence of nifH genes within the rhizosphere.

4. Conclusions

This study assessed the influence of plant density on As phytoremediation of mine waste soil using J. pauciflorus. Higher plant density (44 plants/m2) resulted in the greatest plant biomass and As uptake. However, the study showed that higher plant density may influence the phytoremediation mechanisms from phytostabilisation to phytoextraction. This change was linked to the alteration of As distribution between root and shoot, with higher plant density leading to increased BAF but reduced TF values, though TF values remained >1, indicating that As translocation from root to shoot still occurred. Higher planting density (44 plants/m2) enhanced the abundance of the nifH gene in the soil and rhizosphere, which may contribute to increasing soil TN. Higher plant density promoted the highest soil TN content on day 33, indicating the synergetic effects of biochar and B. subtilis in supplying N to the soil. These findings highlight the potential of plants with higher density in remediating As mine waste soil. In addition, the results suggest that integrating native vegetation with biochar and microbial amendment may provide a sustainable, plant-based approach for the remediation of As-contaminated mine waste, with potential implications for environmentally sustainable mine land rehabilitation. Future studies should be conducted in the field on a larger scale to evaluate whether this approach works effectively at an actual As-contaminated mine site. In addition, this study did not include other complementary analyses, such as As speciation and N mineralisation rates, which would be important for elucidating the underlying mechanisms of As phytoremediation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, F.H., L.S.K., K.S., A.S., P.N. and A.S.B.; investigation, F.H.; resources, A.S.B.; data curation, F.H.; writing—original draft preparation, F.H.; writing—review and editing, L.S.K., J.A.B., K.S., A.S., P.N. and A.S.B.; visualisation, F.H., L.S.K., K.S., A.S., P.N. and A.S.B.; supervision, L.S.K., K.S., J.A.B., A.S., P.N. and A.S.B.; project administration, F.H. and A.S.B.; funding acquisition, A.S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the RMIT University Research Scholarship and the Beasiswa Indonesia Bangkit (BIB), funded by the Ministry of Religious Affairs of the Republic of Indonesia and the Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge RMIT University, ARC Training Centre for the Transformation of Australia’s Biosolids Resource, and Beasiswa Indonesia Bangkit (BIB) Scholarship for supporting this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mandal, B.K.; Suzuki, K.T. Arsenic round the world: A review. Talanta 2002, 58, 201–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, F.; Huang, J.; Li, H.; Peng, X.; Xia, L.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, T.; Liu, Z.; He, Q.; Luo, F. Biogeochemical behavior and pollution control of arsenic in mining areas: A review. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1043024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlesinger, W.H.; Klein, E.M.; Vengosh, A. The global biogeochemical cycle of arsenic. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2022, 36, e2022GB007515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.S.; Pandey, P.K.; Martín-Ramos, P.; Corns, W.T.; Varol, S.; Bhattacharya, P.; Zhu, Y. A review on arsenic in the environment: Contamination, mobility, sources, and exposure. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 8803–8821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mora-Sánchez, F.J.; Gómez-Álvarez, A.; Encinas-Romero, M.A.; Valenzuela-García, J.L.; Jara-Marini, M.E.; Encinas-Soto, K.K.; Villalba-Atondo, A.I.; Dórame-Carreño, G. Granulometric and Geochemical Distribution of Arsenic in a Mining Environmental Liability in a Semi-arid Area. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2024, 87, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollson, C.J.; Smith, E.; Scheckel, K.G.; Betts, A.R.; Juhasz, A.L. Assessment of arsenic speciation and bioaccessibility in mine-impacted materials. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 313, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, M.C.d.S.; Hott, R.d.C.; Santos, M.J.d.; Santos, M.S.; Andrade, T.G.; Bomfeti, C.A.; Rocha, B.A.; Barbosa, F., Jr.; Rodrigues, J.L. Arsenic in mining areas: Environmental contamination routes. IJERPH 2023, 20, 4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Makishah, N.; Taleb, M.A.; Barakat, M. Arsenic bioaccumulation in arsenic-contaminated soil: A review. Chem. Pap. 2020, 74, 2743–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, C.; Gudka, S.; De Meyer, S.; Dennekamp, M.; Netherway, P.; Moslehi, M.; Chaston, T.; Mikkonen, A.; Martin, J.; Taylor, M.P. Arsenic in Soil: A Critical and Scoping Review of Exposure Pathways and Health Impacts. Environments 2025, 12, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnegan, P.M.; Chen, W. Arsenic toxicity: The effects on plant metabolism. Front. Physiol. 2012, 3, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, D.; Datta, S.; Mishra, R.; Agarwal, P.; Kumari, T.; Adeyemi, S.B.; Kumar Maurya, A.; Ganguly, S.; Atique, U.; Seal, S. Negative impacts of arsenic on plants and mitigation strategies. Plants 2023, 12, 1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Majumdar, A.; Srivastava, S. Approaches for assisted phytoremediation of arsenic contaminated sites. In Assisted Phytoremediation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 221–242. [Google Scholar]

- Huslina, F.; Khudur, L.S.; Besedin, J.A.; Nahar, K.; Shah, K.; Surapaneni, A.; Netherway, P.; Ball, A.S. The Phytoremediation of Arsenic-Contaminated Waste by Poa labillardieri, Juncus pauciflorus, and Rytidosperma caespitosum. Environments 2025, 12, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, J.P.T.; David, C.P.C. Soil amelioration potential of legumes for mine tailings. Philipp. J. Sci. 2014, 143, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Banning, N.; Grant, C.; Jones, D.; Murphy, D. Recovery of soil organic matter, organic matter turnover and nitrogen cycling in a post-mining forest rehabilitation chronosequence. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2008, 40, 2021–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Chen, G.; Zhang, C.; Melillo, J.M.; Hall, C.A. Pattern and variation of C: N: P ratios in China’s soils: A synthesis of observational data. Biogeochemistry 2010, 98, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Maiti, S.K. Nitrogen recovery in reclaimed mine soil under different amendment practices in tandem with legume and non-legume revegetation: A review. Soil Use Manag. 2022, 38, 1113–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, M.; Faz, A.; Zornoza, R.; Martinez-Martinez, S.; Acosta, J.A. Phytoremediation potential of native plant species in mine soils polluted by metal (loid) s and rare earth elements. Plants 2023, 12, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, H.; Mahroof, S.; Ahmad, K.S.; Sadia, S.; Iqbal, U.; Mehmood, A.; Shehzad, M.A.; Basit, A.; Tahir, M.M.; Awan, U.A. Harnessing native plants for sustainable heavy metal phytoremediation in crushing industry soils of Muzaffarabad. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 38, 104141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purakayastha, T.; Bera, T.; Bhaduri, D.; Sarkar, B.; Mandal, S.; Wade, P.; Kumari, S.; Biswas, S.; Menon, M.; Pathak, H. A review on biochar modulated soil condition improvements and nutrient dynamics concerning crop yields: Pathways to climate change mitigation and global food security. Chemosphere 2019, 227, 345–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Tang, J.; Xi, X.; Zhang, S.; Liang, G.; Zhou, W.; Wang, X. Responses of soil nutrients and microbial activities to additions of maize straw biochar and chemical fertilization in a calcareous soil. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2018, 84, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, P.; Wang, J.; Pan, Y.; Shen, B.; Wu, C. Review of biochar for the management of contaminated soil: Preparation, application and prospect. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 659, 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Rajapaksha, A.U.; Lim, J.E.; Zhang, M.; Bolan, N.; Mohan, D.; Vithanage, M.; Lee, S.S.; Ok, Y.S. Biochar as a sorbent for contaminant management in soil and water: A review. Chemosphere 2014, 99, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Shen, B.; Liu, L. Insights into biochar and hydrochar production and applications: A review. Energy 2019, 171, 581–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal, J.; Ahmad, W.; Munsif, F.; Khan, A.; Zou, Z. Advances and prospects of biochar in improving soil fertility, biochemical quality, and environmental applications. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1114752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Jabeen, N.; Chachar, Z.; Chachar, S.; Ahmed, S.; Ahmed, N.; Laghari, A.A.; Sahito, Z.A.; Farruhbek, R.; Yang, Z. The role of biochar in enhancing soil health & interactions with rhizosphere properties and enzyme activities in organic fertilizer substitution. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1595208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.; Chen, S.; Zhang, D.; Wang, J.; Lei, M.; Ju, T.; Wei, H. Influence of biochar on the arsenic phytoextraction potential of Pteris vittata in soils from an abandoned arsenic mining site. Chemosphere 2024, 352, 141389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Ma, J.; Liu, K.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J. Biochar-Based Remediation of Heavy Metal-Contaminated Soils: Mechanisms, Synergies, and Sustainable Prospects. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, S.; Varma, A.; Choudhary, D.K. Perspectives on nitrogen-fixing Bacillus species. In Soil Nitrogen Ecology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 359–369. [Google Scholar]

- Threatt, S.D.; Rees, D.C. Biological nitrogen fixation in theory, practice, and reality: A perspective on the molybdenum nitrogenase system. FEBS Lett. 2023, 597, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, M.M.; Guo, L.; Zhang, H.; Wu, F.; Zou, S.; Xing, S.; Mao, Y. Comparative impact of Bacillus spp. on long-term N supply and N-cycling bacterial distribution under biochar and manure amendment. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2022, 22, 882–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Wang, J.; Yan, Y.; Wang, J.; Shao, W.; Wu, Z. Biochar-based Bacillus subtilis inoculants promote plant growth: Regulating microbial community to improve soil properties. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xing, Y.; Fu, X.; Ji, L.; Li, T.; Wang, J.; Chen, G.; Qi, Z.; Zhang, Q. Biochemical mechanisms of rhizospheric Bacillus subtilis-facilitated phytoextraction by alfalfa under cadmium stress–Microbial diversity and metabolomics analyses. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 212, 112016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deka, D.; Patwa, D.; Nair, A.M.; Ravi, K. Influence of biochar amendment on removal of heavy metal from soils using phytoremediation by Catharanthus roseus L. and Chrysopogon zizanioides L. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 53552–53569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyia, P.C.; Ozoko, D.C.; Ifediegwu, S.I. Phytoremediation of arsenic-contaminated soils by arsenic hyperaccumulating plants in selected areas of Enugu State, Southeastern, Nigeria. Geol. Ecol. Landsc. 2021, 5, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besedin, J.A.; Khudur, L.S.; Besedin, D.A.; Netherway, P.; Juhasz, A.L.; Batra, A.; Huslina, F.; Biek, S.K.; Aguilar, G., Jr.; Ball, A.S. Assessment of biochar, compost, and iron amendments to enhance the phytostabilisation of arsenic in gold mine waste by the Australian native plant species Poa labillardieri (Steud.). Chemosphere 2025, 391, 144728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Shi, X.; Wang, Z.; Pei, C.; Cao, M.; Luo, J. Influence of planting density on the phytoremediation efficiency of Festuca arundinacea in cd-polluted soil. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2021, 107, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; He, M.; Qi, S.; Wu, J.; Gu, X.S. Effect of planting density and harvest protocol on field-scale phytoremediation efficiency by Eucalyptus globulus. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 11343–11350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Meng, F.; Tong, Y.; Chi, J. Effect of plant density on phytoremediation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons contaminated sediments with Vallisneria spiralis. Ecol. Eng. 2014, 73, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, S.; Dobson, K. Environmental Audit (s 53V): Gold Mining Tailings at Clay Gully, Maiden Gully, Victoria; AECOM Australia Pty Ltd.: Fortitude Valley, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- EPA. Method 3050B: Acid Digestion of Sediments, Sludges, and Soils. 1996. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-12/documents/3050b.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2023).

- EPA. Method 6020B Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry. 2014. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-12/documents/6020b.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2023).

- Thomas, C.L.; Hernandez-Allica, J.; Dunham, S.J.; McGrath, S.P.; Haefele, S.M. A comparison of soil texture measurements using mid-infrared spectroscopy (MIRS) and laser diffraction analysis (LDA) in diverse soils. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soriano-Disla, J.M.; Janik, L.J.; Forrester, S.T.; Grocke, S.F.; Fitzpatrick, R.W.; McLaughlin, M.J. The use of mid-infrared diffuse reflectance spectroscopy for acid sulfate soil analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 646, 1489–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Verma, P.C.; Chaudhry, V.; Singh, N.; Abhilash, P.; Kumar, K.V.; Sharma, N.; Singh, N. Influence of inoculation of arsenic-resistant Staphylococcus arlettae on growth and arsenic uptake in Brassica juncea (L.) Czern. Var. R-46. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 262, 1039–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, T.; Yu, H.; Li, F.; Zeng, W.; Wu, X.; Shen, L.; Yu, R.; Liu, Y.; Li, J. Antimony-oxidizing bacteria alleviate Sb stress in Arabidopsis by attenuating Sb toxicity and reducing Sb uptake. Plant Soil 2020, 452, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Georgiadis, M.; Fourqurean, J.W. Determination of arsenic in seagrass using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Spectrochim. Acta Part B At. Spectrosc. 2000, 55, 1411–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khudur, L.S.; Gleeson, D.B.; Ryan, M.H.; Shahsavari, E.; Haleyur, N.; Nugegoda, D.; Ball, A.S. Implications of co-contamination with aged heavy metals and total petroleum hydrocarbons on natural attenuation and ecotoxicity in Australian soils. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 243, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaby, J.C.; Buckley, D.H. A comprehensive evaluation of PCR primers to amplify the nifH gene of nitrogenase. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, E.; Kim, K.-H.; Kwon, E.E. Biochar as a tool for the improvement of soil and environment. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1324533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, A.; Tabassum, B.; Abd_Allah, E.F. Bacillus subtilis: A plant-growth promoting rhizobacterium that also impacts biotic stress. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 26, 1291–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, T.; Huang, X.; Zhou, X.; Wu, J.; Kamran, M.A.; Yu, X.; Qian, J. Biochar and Bacillus subtilis co-drive dryland soil microbial community and enzyme responses. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1603488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Shah, S.; Jamal, A.; Saeed, M.F.; Mihoub, A.; Zia, A.; Ahmed, I.; Seleiman, M.F.; Mancinelli, R.; Radicetti, E. Combined effect of biochar and plant growth-promoting rhizbacteria on physiological responses of canola (Brassica napus L.) subjected to drought stress. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2024, 43, 1814–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, F.; Khan, I.U.; Rutherford, S.; Dai, Z.-C.; Li, G.; Du, D.-L. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria and biochar production from Parthenium hysterophorus enhance seed germination and productivity in barley under drought stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1175097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.-L.; Wang, Y.-F.; Mo, J.; Zeng, P.; Chen, J.; Sun, C. Effects of biochar application and nutrient fluctuation on the growth, and cadmium and nutrient uptake of Trifolium repens with different planting densities in Cd-contaminated soils. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1269082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barra Caracciolo, A.; Terenzi, V. Rhizosphere microbial communities and heavy metals. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Narayanan, M.; Shi, X.; Chen, X.; Li, Z.; Natarajan, D.; Ma, Y. Plant growth-promoting bacteria in metal-contaminated soil: Current perspectives on remediation mechanisms. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 966226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.; McBride, M.B.; Kessler, A. Arsenic bioaccumulation by Eruca sativa is unaffected by intercropping or plant density. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2017, 228, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.-J.; McGrath, S.P.; Meharg, A.A. Arsenic as a food chain contaminant: Mechanisms of plant uptake and metabolism and mitigation strategies. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2010, 61, 535–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, V.; Edrisi, S.A.; Chen, B.; Gupta, V.K.; Vilu, R.; Gathergood, N.; Abhilash, P.C. Biotechnological Advances for Restoring Degraded Land for Sustainable Development. Trends Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 847–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM). Scientific Opinion on arsenic in food. EFSA J. 2009, 7, 1351. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Singh, S.P.; Tong, Y.W. Phytoremediation of metals: Bioconcentration and translocation factors. In Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 19–37. [Google Scholar]

- Giehl, R.F.; von Wirén, N. Root nutrient foraging. Plant Physiol. 2014, 166, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemens, S. Toxic metal accumulation, responses to exposure and mechanisms of tolerance in plants. Biochimie 2006, 88, 1707–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Yang, K.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Bao, L.; Zhang, N. Research progress on the uptake and transport of antimony and arsenic in the soil-crop system. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1610041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, H.; Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Zhou, J.; Lv, C. Effects of Biochar and Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria on Plant Performance and Soil Environmental Stability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakeem, K.R.; Alharby, H.F.; Bamagoos, A.A.; Pirzadah, T.B. Biochar promotes arsenic (As) immobilization in contaminated soils and alleviates the As-toxicity in soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.). Chemosphere 2022, 292, 133407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhine, E.D.; Garcia-Dominguez, E.; Phelps, C.D.; Young, L. Environmental microbes can speciate and cycle arsenic. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 9569–9573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, H.; Caggìa, V.; Gómez-Chamorro, A.; Fischer, D.; Coll-Crespí, M.; Liu, X.; Chávez-Capilla, T.; Schlaeppi, K.; Ramette, A.; Mestrot, A. The effects of soil microbial disturbance and plants on arsenic concentrations and speciation in soil water and soils. Expo. Health 2024, 16, 805–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.-S.; Park, J.-H.; Kim, S.-J.; Jeong, H.Y.; Ahn, J.S. Redox transformation of soil minerals and arsenic in arsenic-contaminated soil under cycling redox conditions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 378, 120745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davys, D.; Rayns, F.; Charlesworth, S.; Lillywhite, R. The effect of different biochar characteristics on soil nitrogen transformation processes: A review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.