Abstract

This study investigates critical research gaps in procurement management challenges faced by Chinese contractors in international engineering–procurement–construction (EPC) projects under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), with a particular focus on sustainability-oriented outcomes. It examines the following: (1) prevalent procurement inefficiencies, such as communication delays and material shortages, encountered in international EPC projects; (2) the role of supply chain INTEGRATION in enhancing procurement performance; (3) the application of social network analysis (SNA) to reveal inter-organizational relationships in procurement systems; and (4) the influence of stakeholder collaboration on achieving efficient and sustainable procurement processes. The findings demonstrate that effective supply chain integration significantly improves procurement efficiency, reduces delays, and lowers costs, thereby contributing to more sustainable project delivery. Strong collaboration and transparent communication among key stakeholders—including contractors, suppliers, subcontractors, and designers—are shown to be essential for mitigating procurement risks and supporting resilient supply chain operations. SNA results highlight the critical roles of central stakeholders and their relational structures in optimizing resource allocation and enhancing risk management capabilities. Evidence from case studies further indicates that Chinese contractors increasingly adopt sustainability-oriented practices, such as just-in-time inventory management, strategic supplier relationship management, and digital procurement platforms, to reduce inefficiencies and environmental impacts. Overall, this study underscores that supply chain INTEGRATION, combined with robust stakeholder collaboration, is a key enabler of sustainable procurement and long-term competitiveness for Chinese contractors in the global EPC market. The purpose of this study is to identify critical procurement management challenges and propose evidence-based solutions for Chinese contractors. It further aims to develop a sustainability-oriented framework integrating supply chain integration and stakeholder collaboration to enhance competitiveness.

1. Introduction

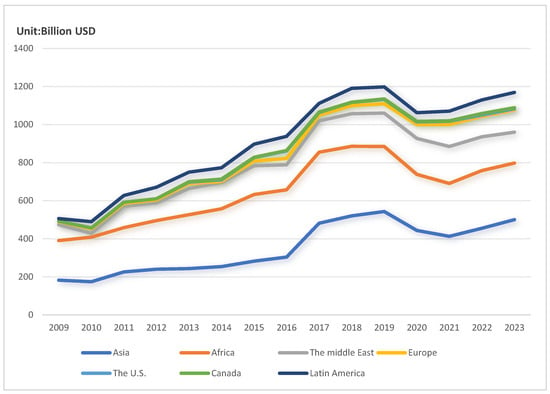

The “Go Global” policy and the “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI) have significantly accelerated the growth of China’s global contracting sector. Since 2009, Chinese contractors have persistently penetrated worldwide markets, progressively encompassing regions like the Middle East, Asia, Africa, Europe, the United States, Canada, and Latin America. The overall business volume has persisted in its growth. The “Belt and Road Initiative,” initiated in 2013, has intensified China’s involvement in global infrastructure development, fostering commerce, investment, and collaboration across these areas. This effort has been a crucial catalyst for the globalization of Chinese contractors, especially in the execution of massive infrastructure projects, including roads, trains, electricity, and utilities. In the last ten years, Chinese contractors have progressively engaged in high-value EPC (Engineering-Procurement-Construction) projects, utilizing their skills to obtain significant contracts in growing markets. In 2023, China’s ENR Top 225 contractors maintain a substantial influence in these regions, as seen in Figure 1, with international revenues indicating their expanding presence.

Figure 1.

Regional Distribution of International Business Revenue for Chinese ENR Top 225 Contractors from 2009 to 2023. Data Source: Engineering News-Record (ENR), United States, from 2009 to 2023. Unit: Billion (USD).

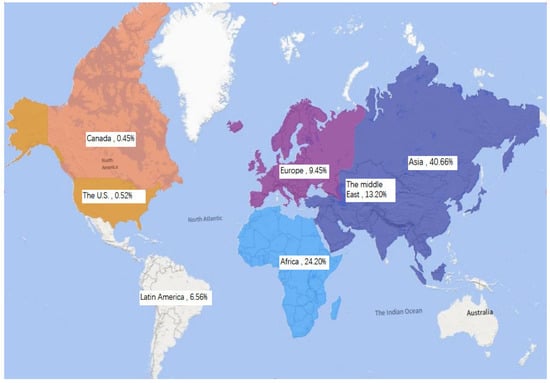

This tendency closely fits with the goals of the Belt and Road Initiative, which seeks to enhance economic and infrastructure connections between China and the global community. The overseas activities of Chinese contractors are predominantly focused in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, but also expanding into established markets such Europe, the United States, and Canada. Figure 2 illustrates the regional distribution of overseas revenues for China’s ENR Top 225 contractors in 2023, emphasizing the growing presence of Chinese construction firms in global markets.

Figure 2.

Regional Distribution of International Business Revenue for Chinese ENR Top 225 Contractors in 2023. Data Source: Engineering News-Record (ENR), United States, 2023.

With the increasing market share of Chinese contractors in the international contracting sector, the EPC (Engineering-Procurement-Construction) integrated contracting model, recognized for its efficient integration and resource allocation benefits, is progressively preferred by both clients and contractors in global projects. Under the EPC model, the customer mandates the contractor to do construction, as well as design, procurement, commissioning, and additional responsibilities [1]. This approach is appropriate for projects characterized by elevated technical specifications, significant professionalism, intricate procedures, and a substantial quantity of non-standard equipment [2,3]. In recent years, the proliferation of high-tech projects in sectors such as power generation, chemicals, and mining has led customers to favor a singular general contractor to execute the design, procurement, building, and commissioning phases.

The EPC model necessitates that contractors have advanced management skills to effectively coordinate various operations in design, procurement, and construction. If a contractor possesses inadequate management skills, they will not only fail to fully exploit the EPC model’s benefits in resource integration but may also incur substantial project losses [4]. The intricacies of international EPC project procurement frequently give rise to numerous challenges, including delayed communication impacting procurement timelines, tardy delivery of design documents hindering procurement strategies, incomplete or rigid procurement plans, absence of shortage warning systems resulting in work interruptions due to material deficits, and inadequate communication between design and construction teams leading to the use of inappropriate materials or equipment. Consequently, enhancing procurement management is essential for the successful execution of the entire project.

Due to the pivotal role and management difficulties of procurement in international EPC projects, general contractors must implement innovative strategies to improve procurement management. In conventional procurement management, the interactions among stakeholders, including contractors, suppliers, customers, and consulting engineers, are generally perceived as transient contractual associations. Due to varying objectives and interests, each party competes to obtain a greater share of benefits, frequently resulting in procurement challenges such as insufficient collaboration, ineffective interface management, fragmented processes that diminish procurement efficiency, and information asymmetry that escalates transaction costs, ultimately inflating construction expenses or compromising quality [5,6,7].

Numerous experts advocate for the incorporation of supply chain integration in building project management to optimize disjointed operations and minimize costs and duration [8,9,10]. Supply chain integration underscores enduring collaboration among stakeholders to synchronize intricate and varied procurement procedures [11,12]. Its essence is in dismantling internal and external organizational barriers, facilitating the effective transmission of essential information and resources across participant borders, minimizing managerial and technological redundancy, and improving supply chain efficiency [13,14,15]. Recent studies indicate that contractors ought to consolidate the whole procurement process with an emphasis on supply chain value creation, therefore optimizing the contributions of each stakeholder in international EPC project procurement [16,17,18]. This is essential for attaining optimal procurement performance and securing a competitive edge [19,20,21]. Consequently, examining procurement management through the lens of supply chain integration in multinational EPC projects is of considerable theoretical and practical significance for enhancing the management capabilities of contractors in such projects [22,23].

This study is designed to examine critical difficulties in procurement management for international EPC projects, emphasizing the role of Chinese contractors within the Belt and Road Initiative. The initial part presents a summary of the global expansion of Chinese contractors and the influence of the Belt and Road Initiative on international infrastructure [24,25,26,27,28,29]. The second portion provides a literature analysis, examining pertinent research on procurement management in EPC projects. The third portion employs social network analysis and case studies to derive findings regarding stakeholder interactions and procurement procedures. The fourth component presents supply chain integration, analyzing its capacity to enhance procurement efficiency and diminish expenses. The study ultimately examines the theoretical and practical ramifications of incorporating supply chain management into procurement strategies and finishes with suggestions for enhancing procurement and project results [30].

The purpose and motivation for this paper are summarized as follows. Empirical evidence of this paper from international EPC projects starkly positions procurement as the pivotal nerve center, commanding 40–60% of total contract value while directly dictating schedule viability, budget integrity, and quality outcomes. Real-world case studies consistently expose overwhelming systemic pressures: intricate stakeholder networks, massive procurement volumes with demanding technical specifications, protracted equipment lead times that strain logistics and warehousing, harsh site conditions impeding heavy machinery transport, and relentless quality imperatives for electromechanical systems [31,32,33,34]. Field research further documents how volatile external forces—market fluctuations, geopolitical instabilities, and cultural divergence—render international engineering service procurement exceptionally fragile. Critically, data-driven investigations reveal that conventional transactional paradigms, where contractors, suppliers, owners, and consultants pursue fragmented self-interests, catastrophically amplify these challenges. Documented instances across multinational projects show resulting dysfunctions—information bottlenecks, delayed design releases, rigid procurement plans, and adversarial interfaces—that spawn information asymmetries, escalate transaction costs, and inflate construction expenditures [35].

This empirical convergence of high stakes and systemic failure urgently motivates a radical transformation grounded in proven practice. Concrete examples from global EPC delivery demonstrate that project success increasingly hinges not merely on procuring equipment, but on orchestrating a seamless value creation ecosystem where every supply chain participant maximizes collective contribution. Recent quantitative studies and industry benchmarks compellingly substantiate that embedding procurement management within an integrated supply chain framework fundamentally reconfigures this dynamic. Empirical analyses show that fostering long-term collaborative partnerships and dismantling organizational silos enables contractors to synchronize complex procurement tasks, accelerate information and resource flows, eliminate redundancies, and align incentives toward shared objectives—directly translating into measurable performance gains. This evidence-based shift—from transactional exchange to strategic supply chain integration—represents not an incremental improvement, but an essential competitive imperative validated by successful multinational implementations, offering general contractors a proven pathway to master EPC complexities and secure sustainable market leadership.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Procurement Management in International Engineering EPC Initiatives

In international engineering EPC projects, the requisite materials and equipment are generally classified into engineering materials, temporary construction materials, construction tools and equipment, spare parts, construction materials, electromechanical equipment essential for the project, permanent electromechanical equipment for the finalized project, auxiliary life and office facilities, and testing equipment [22,23]. Recent studies have highlighted the essential function of procurement management in the execution of international engineering EPC projects, primarily evident in the following aspects: Procurement acts as a conduit between design and construction, with materials and equipment constituting the essential basis for both phases. Equipment and material expenditures represent a substantial portion of the total contract value in EPC projects [35]. There exists a considerable reliance on external entities, such as suppliers and logistics service providers. Procurement necessitates extensive communication and negotiation with these external organizations. In contrast to design and construction, the general contractor exercises diminished control over procurement, especially concerning equipment with extended lead times. Unlike conventional manufacturing, EPC projects frequently incorporate non-standard components, and suppliers typically do not maintain buffer stocks for these projects. Large electromechanical equipment is expensive and entails protracted production cycles. Effective procurement management can markedly improve overall project performance [36,37].

Nonetheless, owing to the intricacies of procurement processes in international engineering EPC projects, numerous critical concerns presently arise: Procurement activities in these projects comprise numerous interdependent tasks, rendering the flow of information vital [38]; De la Garza (1994) [39] contends that procurement encompasses various stakeholders, including the owner, design team, construction team, equipment and material suppliers, government agencies, equipment operators, and maintenance teams, resulting in fragmentation of procurement activities due to the extensive number of participants; ongoing and repetitive information exchange is necessary among project participants, and fragmented work may foster adversarial relationships between organizations [39,40]; Baily (1990) [41] posits that in worldwide procurement, the time of procurement activities is challenging to forecast, particularly concerning discussions, approvals, and transportation, with extended procurement cycles for electromechanical equipment. This results in considerable uncertainty regarding delivery timelines, and the communication and approval of drawings and data among suppliers, designers, and owners may further impede procurement advancement. The technical specifications of significant electromechanical equipment may be interconnected with components from various suppliers; the overlap among procurement, design, and construction processes heightens the risk of cost overruns and schedule delays due to inadequate information and frequent modifications [41].

Numerous researchers have suggested strategies to enhance procurement performance in projects, such as concurrent engineering [42,43], lean construction [44], partnerships [45,46], and logistics and supply chain management [47,48,49]. Williams (1995) [47] advocates for the selection of familiar and dependable suppliers to streamline procurement processes and reduce procurement cycles; Love et al. (2011) [48] contend that downstream participants in procurement should engage in upstream activities to actively mitigate issues such as rework and redundant design. They promote collaboration from the project’s inception to mitigate and diminish tensions thereafter; Nguyen and Mohamed (2018) [49] advocates for the reorganization of procurement procedures and project information flows, the elimination or reduction in duplicate processes, and the utilization of information technology to enhance the storage, retrieval, and processing of information; Bresnen (2000) [50] advocates for dismantling barriers between organizations and project functions to enhance communication, coordination, and collaboration; Mackelprang et al. (2014) [51] developed incentive contracts predicated on transfer payments and production costs for the strategic procurement of materials in large engineering projects, with the objective of accurately reflecting suppliers’ true cost information and promoting enhanced effort in production and manufacturing. Biet al. (2011) [52] introduced a procurement risk assessment model, which, through empirical research, demonstrated its capacity to achieve a more efficient and precise evaluation of procurement risks in EPC projects, thereby providing a foundation for the implementation of procurement risk management strategies. Yeo et al. (2002) [53] contend that partnerships can mitigate issues such as fragmented processes, lack of integration, and adversarial relationships, advocating for the management of uncertainties in procurement through supply chain integration [50,51,52].

In international engineering EPC projects, procurement management functions as a critical conduit between design and construction, commanding a substantial share of total project expenditure while remaining inherently susceptible to systemic complexities. The process is characterized by extensive stakeholder fragmentation, encompassing owners, designers, contractors, suppliers, and regulatory agencies, which necessitates continuous information exchange yet cultivates adversarial inter-organizational relationships. Compounding these challenges, protracted lead times for major electromechanical equipment, unpredictable approval cycles, and technical interdependencies across suppliers introduce profound temporal uncertainties. The concurrent execution of procurement with design and construction phases further amplifies vulnerabilities, as non-standardized components, absence of supplier buffer stocks, and diminished contractor control render projects acutely exposed to cost overruns and schedule delays stemming from information asymmetries and recurrent modifications.

To mitigate these pervasive challenges, scholarly research advocates for integrated strategic frameworks that transcend traditional procurement boundaries. These encompass concurrent engineering principles to synchronize stakeholder activities, lean construction methodologies to eliminate process redundancies, and collaborative partnerships to foster trust-based relationships and supply chain integration. Critical success factors include early engagement of downstream participants in upstream processes, deployment of information technologies to enhance data storage and retrieval, and implementation of incentive-aligned contractual mechanisms that elicit authentic cost information and motivate superior supplier performance. Furthermore, systematic risk assessment models and organizational barrier deconstruction have demonstrated efficacy in reducing fragmentation, improving coordination, and establishing resilient procurement ecosystems capable of navigating the uncertainties inherent in global EPC project delivery.

2.2. Theory of Supply Chain Integration

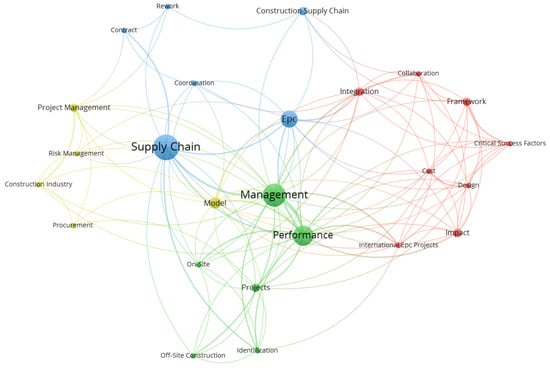

Figure 3 depicts a comprehensive term co-occurrence network encompassing 173 interconnected supply chain integration terminologies derived from author and index synonyms, wherein 25 keywords satisfied the minimum occurrence threshold of two. The network reveals scholarly emphasis on critical domain interactions, reflecting increasing recognition of seamless integration and strategic cooperation in optimizing supply chain relationships within complex construction environments. Effective governance and coordination mechanisms are therefore essential for fostering stakeholder collaboration, thereby enhancing project performance and outcomes.

Figure 3.

Co-occurrence network of research on Supply chain integration.

The initial studies on supply chain management (SCM) originate from Kraljic (1983) [54] and Shapiro (1984) [55], who authored significant articles on SCM and logistics in the Harvard Business Review. Since that time, the notion of Supply Chain Management (SCM) has swiftly progressed, resulting in a plethora of definitions in the literature.

Copacino (1997) [56] characterize Supply Chain Management (SCM) as the administration of the movement of resources and goods from suppliers to customers, highlighting the interrelation of business processes. The Supply Chain Council [53] defines Supply Chain Management (SCM) as the processes involved in the production and delivery of the final product, including the entire range from the original supplier to the end consumer, emphasizing its cross-functional and cross-enterprise nature [53].

Cooper et al. (1997) [57] characterize Supply Chain Management (SCM) as the amalgamation of business processes from the end user to the primary suppliers, emphasizing the management of both upstream and downstream relationships to provide value at reduced costs. Handfield et al. (2002) [58] define supply chain management (SCM) as the amalgamation of activities and information flows from raw materials to the end user, highlighting the need of relationship management to attain competitive advantage.

Mentzer et al. (2001) [59] characterize the supply chain as a sequence of organizations engaged in the movement of products, services, capital, and information, differentiating among direct, extended, and ultimate supply chains. The Japanese Journal of Business Administration highlights supply chain management (SCM) as a cohesive process that transcends corporate boundaries to optimize resources and eradicate waste [56].

These definitions jointly emphasize three critical aspects: (1) the necessity for comprehensive integration of supply chain activities; (2) the significance of managing product, service, and information flows across enterprises; and (3) integration as the most effective strategy for attaining supply chain efficiency [57].

Since the 1980s, supply chain integration has been acknowledged as fundamental to supply chain management and a crucial determinant of performance and competitive advantage. Widely recognized concepts of supply chain integration emphasize both internal and external collaboration [58,59]. Internal integration pertains to collaboration across divisions, whereas external integration concerns the exchange of information between companies.

Supply chain integration refers to the extent of collaboration between an organization and its stakeholders, as well as the management of internal and external processes, to facilitate the efficient movement of products, services, information, and decisions, thereby providing value to customers at reduced costs and increased speed [60,61].

In summary, supply chain integration involves fostering cooperation and trust, improving communication, and leveraging technology to accelerate information flow, ultimately enhancing supply chain efficiency.

Supply Chain Management (SCM) has proliferated into multiple conceptualizations since its inception in the 1980s, yet its core tenet remains steadfastly anchored in holistic process integration across organizational boundaries. Synthesizing the definitional contributions of Copacino, the Supply Chain Council, and Cooper et al., [53,56,57] SCM is fundamentally a systematic approach that orchestrates upstream and downstream partnerships, converging material, information, and financial flows from raw material sourcing to end-user delivery to generate superior customer value and competitive advantage [62]. This theoretical framework collectively underscores three foundational pillars: (1) comprehensive integration of supply chain activities, (2) cross-enterprise coordination of resource flows, and (3) strategically driven efficiency optimization. Of paramount significance, supply chain integration constitutes both the cornerstone and critical performance determinant of SCM, encompassing intra-organizational cross-functional synergy and extra-organizational information sharing and strategic collaboration with external stakeholders. Its underlying imperative involves cultivating trust-based mechanisms, enhancing communication efficacy, and leveraging technological affordances to accelerate information velocity, thereby culminating in integrated performance outcomes of cost reduction, responsiveness enhancement, and customer value accretion.

2.3. The Benefits of Supply Chain Integration

Supply chain integration is frequently perceived as a collaborative competitive advantage, signifying the strategic superiority achieved through supply chain collaboration that surpasses that of market rivals. These advantages are linked to synergies derived from collaborative behaviors, which individual organizations cannot attain alone [63]. Jap (1999) [64] posits that integration can amplify these benefits, yielding superior returns for all stakeholders involved [64]. Integration yields value through cost reductions from best practice dissemination, enhanced collaborative capacities, superior decision-making, increased profitability via resource synergies, and innovation fostered by the interchange of ideas. While company synergies may not yield immediate gains, they might offer enduring strategic advantages. Cao et al. (2011) [34] delineate five principal advantages of supply chain integration: process efficiency, flexibility, synergy, quality, and innovation [34].

Supply chain integration enables companies to achieve performance improvements that surpass the whole expenditure, which is why several leading models in supply chain management prioritize it. Recent research examining the link between integration and performance have produced contradictory outcomes owing to varying assumptions regarding the components of integration [65,66]. One research identified little advantages in concentrating on the content of integration, whilst another revealed more substantial benefits by prioritizing the stakeholders engaged in integration [67]. Much research predominantly concentrates on certain elements of integration, such as customer or supplier integration, rather than the overarching notion, resulting in conflicting conclusions [67,68,69]. Consequently, a more thorough understanding of supply chain integration is necessary to examine its benefits in a more rigorous and dependable manner.

Supply chain integration constitutes a collaborative competitive advantage that generates synergistic value—encompassing enhanced process efficiency, flexibility, quality, innovation, and profitability—unattainable by individual organizations and exceeding aggregate expenditures. Nevertheless, empirical investigations of the integration-performance nexus have produced contradictory outcomes, attributable to fragmented analytical frameworks focusing on discrete components (e.g., customer/supplier integration) rather than the holistic construct, thereby necessitating more comprehensive conceptualizations for rigorous and reliable benefit assessment.

2.4. The Imperative of Supply Chain Integration in Procurement Management for International EPC Projects

Supply chain integration in construction is predominantly theoretical, since general contractors possess little actual experience. He Bosen (2007) [65] delineates strategies for effective supply chain management, including long-term partnerships [70], supplier reduction [71], information sharing [72], and trust-based collaboration [73], all underscoring the need of cooperation and communication [74].

Manufacturing technologies for supply chain management are intricate and designed for stable supply chains; however, their applicability in construction, which depends on transient, project-based supply chains, is ambiguous [75]. Construction supply chain management must exhibit flexibility to accommodate evolving project requirements.

Construction professionals routinely make supply chain choices; nevertheless, the management of extensive data and coordination among many stakeholders continues to provide challenges [76,77]. Innovation is crucial for enhancing procurement management and managing many stakeholders [78,79].

For international EPC projects, supply chain integration is crucial for leveraging resources and improving procurement efficiency [80,81]. Research into supply chain integration can help identify bottlenecks, enhance management capabilities, and improve project outcomes.

2.5. Theory of Stakeholder Management

The Project Management Institute (PMI) [81] characterizes stakeholder management as the methodical identification, analysis, and strategizing of actions to engage and influence stakeholders. Contemporary research in the construction sector primarily concentrates on three domains: essential components of stakeholder management, stakeholder management procedures and methodologies, and stakeholder relationship management.

- (1)

- Essential Components of Stakeholder Management

Jergeas et al. (2000) [82] determined that “communication, shared objectives, and project priorities” are essential for enhancing stakeholder management. Olander et al. [83] (2005) proposed five essential components: stakeholder requirements analysis, transparent communication, solution assessment, project organization, and media relations [83]. Yang et al. (2011) [84] underscored social responsibility, prompt communication, and information contribution. In 2011, Yang et al. identified 15 essential characteristics from the standpoint of construction practitioners, including regular contact with stakeholders [84].

- (2)

- Processes and Methods for Stakeholder Management

Karlsen (2002) [85] delineated the stakeholder management process: identifying stakeholders, understanding their attributes, facilitating communication, and formulating solutions [85]. Walker et al. (2008) [86] categorized the process into stages: identification, prioritization, visualization, involvement, and communication monitoring [86]. Young (2013) [78] delineated three stages: stakeholder identification, information gathering, and impact assessment. Nonetheless, a cohesive process model is absent. Chinyio et al. (2008) [87] examined stakeholder engagement techniques in UK construction, whereas Reed (2009) [88] addressed stakeholder analysis in natural resource management. Stakeholder management techniques are varied and insufficient [78,87].

2.6. Necessity of Integration of Procurement Management Supply Chain for International Engineering EPC Project

Despite the growth of China’s foreign EPC projects, persistent inefficiencies—including fragmented workflows, overlapping phases, and complex organizational structures—have drawn criticism, underscoring the need for innovative strategies. Supply chain integration, which strategically aligns material flows, production processes, and data streams from suppliers to end consumers, offers a promising solution. While manufacturing industries have achieved notable success through such integration, the construction sector, particularly international EPC projects, has lagged in adoption due to limited practitioner awareness, missing opportunities to revolutionize procurement management and optimize stakeholder coordination.

Empirical evidence suggests that embedding procurement within a supply chain value creation framework could significantly enhance EPC project performance. By fostering long-term partnerships, dismantling organizational silos, and enabling efficient information and resource flows, integration streamlines procurement processes and reduces redundancies. This approach allows general contractors to leverage synergies, improve resource allocation, and achieve competitive advantages in cost, quality, and schedule—transforming procurement from a transactional function into a strategic, value-creating activity essential for superior project outcomes.

However, comprehensive supply chain integration remains rarely implemented in the global EPC sector, partly because many practitioners, including project managers and contractors, inadequately comprehend its complexities or their impact on the supply chain. Given fluctuating global contexts and evolving procurement demands, it is imperative to incorporate supply chain supervision into EPC procurement analysis. Addressing this research gap is crucial for equipping Chinese contractors with the theoretical insights and practical tools needed to consolidate supply networks, enhance resource management, and elevate the global competitiveness of EPC enterprises.

3. Methods

3.1. Analysis of Inter-Organizational Stakeholder Relationships Utilizing Social Network Analysis

This study employs purposive sampling of seasoned procurement managers, project managers, and chief engineers from ENR 2023-leading Chinese EPC contractors, whose 10–15+ years of international experience ensures profound understanding of complex procurement intricacies. Representativeness is guaranteed through geographical breadth (projects across Asia, Africa, Latin America, Middle East, and Oceania) and sectoral diversity (hydropower, thermal power, municipal, mineral resources), while their end-to-end involvement in procurement strategy, supplier management, contract execution, quality control, and logistics yields authentic empirical insights. Their cross-functional collaboration with design, construction, and operations teams, coupled with multi-stakeholder engagement (owners, consultants, logistics providers), furnishes a holistic perspective on procurement’s globalization impact, effectively bridging theoretical models with practical validation and advancing procurement management scholarship.

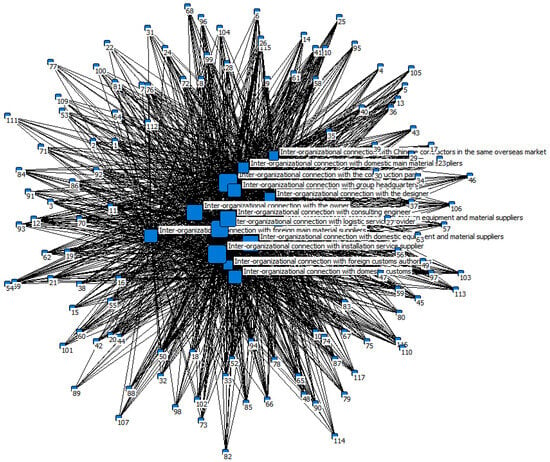

In addition, the survey data on stakeholder cooperation was analyzed using social network analysis to examine the collaborative linkages between the general contractor and stakeholders. Employing social network analysis to examine joint stakeholder influence and organizational strategies, this study maps network dispersion among procurement participants and inter-organizational connections within supply chain integration.

Data were collected via field surveys and online questionnaires from management of four leading Chinese EPC contractors listed in the 2023 ENR250, yielding 117 valid responses from 180 distributed surveys (response rate: 65%). The sample of 117 respondents, comprising exclusively seasoned professionals and senior experts, is highly targeted and representative.

The nodes labeled 1–117 signify the 117 participants in the survey research. The red nodes represent different stakeholders, with the size of each node indicating its betweenness centrality and degree of influence, the spatial arrangement reflecting their relative importance, and the distance between nodes denoting their similarity. The survey data on inter-organizational links was evaluated using social network analysis to examine the network relationships between the general contractor and stakeholder organizations, resulting in the stakeholder inter-organizational relationship network illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

An illustration of the connections between different organizations inside a social network.

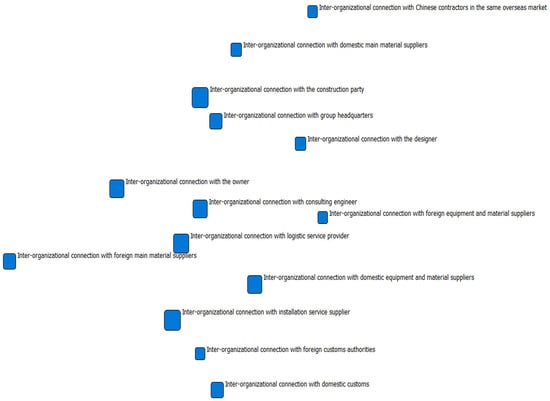

The network diagram has been streamlined for improved clarity. Figure 5 illustrates the distribution of inter-organizational relationships among stakeholders in the reduced form.

Figure 5.

An extended social network diagram showing the inter-organizational connections between stakeholders.

The ranking of intermediary centrality among the inter-organizational links of the stakeholders is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Stakeholders’ intermediate centrality score for inter-organizational relationships.

The aforementioned data indicate that the general contractor sustains strong inter-organizational relationships with all stakeholders. The intermediary centrality scores of stakeholders in inter-organizational links (Table 1) reveal that the construction party has the highest score, represented by the largest node, indicating that its inter-organizational connections have the most substantial impact on the overall procurement process. The foundational structure of the building project must adhere to the requirements and designs of the mechanical and electrical systems, and the construction process requires the general contractor to supply various materials and resources that meet the construction standards. Therefore, collaboration and communication with the construction team throughout all aspects of the procurement process are essential to ensure the smooth implementation of interconnected procurement and construction activities.

The distribution of inter-organizational ties among stakeholders (Figure 5) indicates that both domestic and foreign equipment suppliers, as well as the design party, occupy relatively important positions, highlighting the significance of their inter-organizational links in the procurement process. The quality and production schedule of significant mechanical and electrical equipment are essential factors affecting the project’s timely and planned execution. Establishing strong inter-organizational relationships with local and international equipment suppliers enables real-time monitoring of production status, hence maintaining the quality and progress of critical mechanical and electrical equipment. Furthermore, procurement involves executing the design intent, requiring excellent communication with the design team to guarantee accurate execution of the design. The general contractor must convey the owner’s procurement needs and viewpoints to the design team; hence, establishing an efficient communication channel between the owner and the design team is crucial for the project’s flawless execution.

Furthermore, as seen in Figure 5, the inter-organizational relationships between the general contractor and the group headquarters/domestic equipment suppliers, together with the construction party/domestic primary material suppliers, exhibit notable similarity. This suggests that individuals tasked with sustaining relationships with diverse stakeholders exhibit a considerable degree of resemblance. This discovery may assist the general contractor in refining the internal organizational framework and personnel distribution to improve the efficiency of organizational structures and business operations.

The network formed via collaboration and inter-organizational relationships with procurement stakeholders is the general contractor’s social capital. This social capital, founded on trust and communication within partnerships, allows the general contractor to enhance resource utilization from the social network, thereby reducing formal transaction costs linked to contractual relationships and informal transaction costs arising from trust-based interactions in complex procurement processes. The results of the social network analysis illustrate the importance of social capital among various players in the international EPC project procurement process. By leveraging these insights, the general contractor may effectively utilize the social capital developed via network contacts, hence improving procurement efforts and maximizing overall project execution.

3.2. Case Studies

From 2009 to 2019, Chinese contractors consistently broadened their footprint in international markets, obtaining projects in different geographical areas, including Asia, Africa, the Middle East, Europe, North America, and the Caribbean. This expansion was propelled by the rising worldwide demand for infrastructure development and the competitive benefits provided by Chinese companies in cost efficiency and project execution speed. Consequently, the total business volume increased steadily. In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic significantly disrupted global supply chains and construction activity, resulting in a temporary decline in international contracting volumes. The uncertainty surrounding travel restrictions, material shortages, and fluctuating economic conditions posed challenges to ongoing projects. Despite this setback, Chinese contractors demonstrated resilience and adaptability, and by 2023, international business volumes showed signs of recovery, reflecting renewed confidence in global infrastructure investments. The regional distribution of international business revenue for Chinese ENR [1].

Three exemplary case studies of international EPC projects have been selected for further examination based on the previously indicated data analysis. The inquiry aims to identify the principal challenges encountered in procurement and to outline the procurement management strategies employed by general contractors.

3.2.1. The EPC Project for the Thái Bình Phase II Boiler Island in Vietnam

- (1)

- An overview of the project

The Vietnam Thái Bình Phase II project (Figure 6) comprises two 600 MW subcritical coal-fired power stations located around 20 km southeast of Thái Bình city in Thái Bình province. The Vietnam Oil and Gas Group (PVN) funds the effort. Upon the contract’s activation, Unit 1 is anticipated to be commissioned in 39 months, while Unit 2 is expected to be commissioned in 45 months. The project’s general contractor is undertaking its inaugural substantial EPC (Engineering, Procurement, and Construction) project. Upon completion, it will significantly mitigate the power deficit in the Thái Bình region of Vietnam.

Figure 6.

The Vietnam Thái Bình. Data Source: Photograph taken by the author.

- (2)

- The principal challenges in procurement management

In Vietnam, the types of projects encounter the following principal procurement challenges:

- Procurement management is essential in EPC projects. Unlike traditional construction projects, EPC projects need the general contractor to acquire mechanical and electrical equipment and supplies, as well as to coordinate all aspects of the construction process. Expertise in managing EPC projects is essential for the effective execution of the project. Nevertheless, Project A signifies the inaugural large-scale EPC undertaking by the general contractor, which possesses insufficient experience in project management.

- Design management is essential for acquiring permanent electromechanical equipment. Designers must participate in the thorough procurement process for permanent electrical and mechanical equipment in EPC projects, which includes preparing the procurement schedule per the owner’s contract requirements, developing bidding documents, prequalifying suppliers, conducting procurement bidding, selecting suppliers, executing contracts, overseeing production, inspecting equipment, managing installation and delivery, and accepting completion and formal operation. To ensure the project’s success, the general contractor must improve the designer’s oversight.

- Validation of supplier information is essential. Certain suppliers provide insufficient information, and the filing process is lengthy. Owing to language and professional limitations, the general contractor solely transmits the suppliers’ technical documents to the owners. The technical requirements of mechanical and electrical equipment are often assessed by owners and consulting engineers, leading to inefficient document approval processes.

- Domestic and foreign norms are distinct from each other. International projects often adhere to European or American standards, and the general contractor frequently choose domestic large-scale suppliers with existing cooperative connections when picking vendors. If domestic suppliers do not meet the contract specifications and the owner rejects the provided goods, it will significantly affect the contractor’s progress and costs.

- Procurement of essential resources from other countries. The general contractor can obtain cement, lumber, reinforcement, admixtures, fly ash, and other essential materials from the local market. When sourcing materials from an overseas country, the general contractor must adeptly oversee the procurement process, emphasizing disparities in material standards and associated issues.

- (3)

- A plan for procurement administration

The particular procurement management techniques for the various types of projects are as follows:

- Develop a comprehensive procurement process management system and ensure its strict execution. The procurement of permanent mechanical and electrical equipment for the project is administered by the international business section of the general contractor, supervised by the group headquarters. Enforce the procurement management process and system rigorously, guaranteeing thorough dynamic oversight of the EPC general contract, procurement schedule formulation, technical document preparation, bidding, supplier selection, contract execution, production supervision, logistics and transportation, warehouse management, acceptance, installation, delivery, and operation.

- Stakeholder management must be prioritized. The designer is tasked for delineating the technical standards in the contract, ensuring that the technical specifications for equipment procurement comply with the primary contract’s stipulations. The supervision and control of design drawings must be prioritized to prevent delays in the submission and approval of mechanical and electrical equipment design drawings, which might affect the procurement process. To ensure equipment acceptance, the principal contract for permanent equipment technology and standards must require that mechanical and electrical equipment suppliers comprehensively comprehend and comply with the provisions of the main contract for equipment standards.

- An effective method for interface management An effective interface management process and system is established through communication channels and information distribution methods including stakeholders, such as owners, designers, and suppliers. This system specifies the responsibilities of each party and facilitates the efficient integration between the owner and supplier. By establishing an efficient interface management system with the owner’s personnel, the owner will be able to participate in factory acceptance testing (FAT) and pre-approve technical documents. The assembly of mutually agreed technical documents would streamline the approval procedure, hence minimizing disputes during implementation and favorably impacting the equipment manufacture timeline.

- Effective administration of information transfer. The general contractor has established a specialized working group to ensure real-time control of the whole procurement process, focusing on the full design and procurement of mechanical and electrical equipment while immediately monitoring the procurement activities. Submit weekly procurement reports to corporate headquarters about the status of equipment bids and data approvals. Prompt communication among stakeholders and the seamless flow of information throughout the procurement supply chain improve information flow management, allowing the general contractor to make accurate and effective decisions.

- Developing a prudent purchasing plan requires thorough assessment of several factors. Formulate a procurement strategy for primary construction materials proactively, conduct an economic analysis of material acquisition costs, price volatility, supply dynamics, and price determinants, and undertake a technical evaluation of the performance and standards of materials obtained from foreign suppliers to create a logical purchasing plan and continuously enhance it based on prevailing conditions. To reduce procurement expenses, it is crucial to ensure the quality and quantity of materials meet construction criteria.

- To achieve success in the international market, establish a partnership with Chinese contractors. Collaboration with Chinese contractors in the international market facilitates knowledge transfer and mutual assistance. It may be necessary to enlist the assistance of a Chinese contractor within the same market if there is a shortage of steel bars during concrete pouring. To comply with the construction schedule, the contractor provides substantial support and delivers steel bars at local prices for this project.

- Enhance expertise in warehouse management and the distribution of mechanical and electrical equipment. The existence of equipment issues and the lack of accessories are the principal obstacles affecting the installation and commissioning process; thus, identifying absent non-standard components will significantly influence the building schedule. An excellent emergency response has been instituted by the general contractor for cases of missing components, with the supplier’s customer service staff arranged to do on-site inspections prior to delivery, and the manufacturer promptly alerted to rectify the issue.

3.2.2. A Fijian Renewable Energy Project

- (1)

- An overview of the project

The Fiji Renewable Energy project (Figure 7) is located northwest of Fiji’s main island and comprises a high-voltage transmission line, a power plant structure, a switching station, a barrage, and a water transport system. The Fiji National Electricity Authority possesses a comprehensive EPC contract for this project. The construction duration is 1072 days, with a total contract value of around 125 million US dollars. The project faces several hurdles, including Fiji’s South Pacific location, excessive rainfall, and adverse construction circumstances. Fiji is considered a high-risk market by the industry; its local regulations and technical specifications are akin to those of Australia and New Zealand, while the contract terms are stringent and the implementation standards are elevated.

Figure 7.

A renewable energy project in Fiji B. Data Source: Photograph taken by the author.

- (2)

- Critical challenges in procurement management

The subsequent critical procurement challenges pertain to Fiji B renewable energy initiatives:

- There is a deficiency of materials in the local market. The small geographical area and emerging industry in Fiji create a restricted local material market, resulting in a shortage of construction supplies. Some materials are not accessible for local acquisition, or their costs are three to four times higher than those in the domestic market. Fiji’s ideal vacation system yields a greater frequency of holidays, resulting in prolonged delivery delays from local vendors.

- There are differences in design principles and criteria. Due to historical considerations concerning Fiji, Australia, and New Zealand, the project generally conforms to the Australian New Zealand standard, with technological equipment requirements mostly derived from this standard. Furthermore, local vendors are either unfamiliar with the standard or have never seen it, leading to a restricted understanding of its specific needs.

- Electrical and mechanical devices must comply with stringent quality standards. The proprietor contends that welding and anti-corrosion treatment of pressure equipment are essential, and that the welding must be executed by ASME-certified welders. Fiji, being an island nation, possesses heightened salinity in its air and water, requiring rigorous anti-corrosion measures that most local manufacturers either lack expertise in or fail to focus sufficiently.

- (3)

- A technique for managing procurement

The procurement management of renewable energy projects in Fiji employs the following strategies:

- An effective system for quality management is necessary. To ensure effective oversight of the whole process, including bid invites, bid evaluations, contract negotiations, equipment manufacture, inspections, and factory acceptance, it is prudent to enlist a competent equipment manufacturing supervision firm. Furthermore, sustaining regular connection with the supervisory firm will enable real-time oversight of production advancement and equipment condition. Incorporate rigorous quality standards into communications with designers and suppliers, emphasizing material selection, welding procedures, and corrosion protection specifications, while reinforcing the project’s high quality benchmarks; in accordance with the contract, engage a consultant to conduct the factory acceptance, and proceed with packing and shipping following acceptance approval.

- Procurement of domestic materials. Develop a proactive procurement plan that corresponds with the schedule of design drawings. The 316 L stainless steel pipe employed in the project’s oil, gas, and water pipelines was previously manufactured according to the design specifications. The general contractor swiftly formulated a procurement plan, obtaining supplies locally, which resulted in a cost that was fifty percent cheaper than the local pricing for this steel component. Moreover, consumable supplies are sourced domestically wherever possible, hence promoting construction projects and reducing procurement costs. Due to the high cost of procuring explosives and associated materials locally, such as those employed in construction. To address this issue, the general contractor, referencing the omission of this item in the contract and the production of third-country products in China, agreed to source explosives from China following extensive discussions with the owner and consulting engineers, thereby assuming a proactive role in the construction process.

- Contractual risk transfer transpires when the acquisition of permanent home equipment. The bidding and contract documentation for the permanent equipment includes relevant portions of the EPC contract as appendices to the technical component, intended to transfer the risks related to the permanent electromechanical equipment. The objective is to translate the entire set of contracts into Chinese and identify the risk factors associated with the equipment, so improving the understanding of the EPC contract provisions by procurement staff and suppliers.

- Acquiring goods and equipment locally might significantly impact the timeframe or fail to meet domestic procurement rules. The lack of intermittent materials, such as pipe joints, bolts, paint, and other flammable and explosive items that are difficult to transport, along with fire extinguishers, hydrants, and other domestic products with particular specifications, does not meet the fire safety standards for goods, fire systems, and water supplies. The domestic procurement of drainage pipes and associated materials does not meet the progress criteria.

- Third Country Procurement: Employing the third country procurement technique is crucial for the efficient implementation of the project concerning equipment and materials that are difficult to obtain in the domestic or Fijian market. The contract stipulates that Belray brand oil must be employed for hydraulic hoists, governors, and other hydraulic components, with the general contractor sourcing the oil directly from Belray’s headquarters in the United States.

3.2.3. Zambian Energy Transmission and Transformation Project

- (1)

- An overview of the project

Two switch station upgrades and a 129.2 km single-loop double-split 330 KV transmission line are part of Project Zambia C (Figure 8). The project is an EPC general contract controlled by the Zambia National Power Company. The contract stipulates a duration of 18 months. This is the inaugural overseas transmission project executed by the general contractor, encountering multiple hurdles, such as a 65 km mountainous segment, 18 km of swamps, and traversing hills, mountains, rivers, marshes, as well as roads, railways, and high-voltage lines.

Figure 8.

Project for the transmission and transformation of electricity in Zambia C. Data Source: Photograph taken by the author.

- (2)

- The principal challenges in procurement management

Several critical procurement challenges are linked to the Zambia transmission and transformation line project:

- Geographical restrictions: Because Zambia is a landlocked country in central Africa, a lot of its imports and exports are transshipped through the ports of Beira, Mozambique, Durban, South Africa, and Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

- Transportation of materials for specialized use. The equipment for the C project is procured from China, a considerable distance away, and metal components, such as tower materials, are susceptible to corrosion during maritime shipping.

- Building under adverse situations. Due to the terrain constraints of the project, transporting equipment and materials to the construction site is exceedingly challenging.

- (3)

- A plan for procurement administration

The procurement management strategies for the Zambia transmission and transformation line project are as follows:

- A perfect logistics management system is needed. To facilitate the effective movement of equipment and supplies to the project site, it is essential to develop specific transportation management strategies. In this project, all cables and tower materials are procured domestically and carefully packaged into containers before to shipping. This is a deliberate measure to safeguard the materials from any damage or corrosion during transit and to ensure their arrival at the building site in optimal condition.

Approximately 150 containers are utilized for transporting the tower materials. This form of containerized shipping is preferred over bulk bundling utilized by some organizations because of its enhanced protection for the products. Bulk bundling, while often cost-effective, can lead to significant losses due to environmental exposure, mistreatment, or other risks associated with unsecured transportation.

Additionally, the containers may serve as provisional storage units at the project location, offering protection from environmental factors and unauthorized access until the materials are needed for construction. This dual feature is particularly beneficial in remote or undeveloped areas where safe storage facilities may be limited.

The use of containerized shipping for the tower materials in this project indicates a strategic approach to transportation management. It underscores the imperative of protecting high-value goods during transportation and aligns with the goal of ensuring timely and efficient delivery, which is essential for maintaining the project schedule and minimizing losses.

- Establishing a robust working partnership and managing the interface with foreign customs authorities are crucial.

The general contractor of Project C has implemented a strategy of consistent contact and communication to foster a positive relationship with the Zambian customs officers. This ongoing dialogue is crucial for staying informed about changes in customs legislation and for obtaining information on tax exemption processes. The project possesses tax-exempt status; nevertheless, this benefit relies on the timely approval of tax exemptions, which is closely linked to the project owner’s ability to provide initial funds.

The lack of initial funding from the project owner was an obstacle throughout the project’s initial phase. The financial deficit hindered the prompt approval of the tax exemption, resulting in a potential tax liability that may exceed the project’s designated expenditures. Despite this obstacle, the general contractor maintained diligent communication and effective interface management with the Zambian customs department.

The general contractor’s adept management of the problem underscores the need of proactive stakeholder engagement, especially while traversing bureaucratic processes in a foreign country. Through maintaining clear communication and using their understanding of local customs processes, the general contractor effectively reduced risks and secured a successful project conclusion.

- Cultivate a collaborative partnership with the logistics service provider.

Under extraordinary circumstances, logistical difficulties may occur due to constraints related to equipment size and the specifics of the construction site. Establishing a collaborative alliance with logistics service providers is crucial for overcoming these logistical obstacles. This project includes a building site where the wide river requires the installation of a tower on a central island in the water. However, the challenge arises from the absence of significant vessels capable of navigating the river for the transportation of essential equipment and supplies, complicating the logistics considerably.

To address this difficulty, the general contractor resourcefully employed tower poles as makeshift lifting and hoisting devices, demonstrating adaptability and inventiveness. A partnership with Autoworld UK yielded a solution for providing suitable vessels capable of navigating the river’s conditions and carrying significant cargoes. This partnership was crucial for transporting the large and heavy tower components to the main island, where the trans-river tower was to be erected.

In addition to securing the boats, the general contractor coordinated the construction of temporary piers on both banks of the river. These piers served as vital infrastructure, enabling the safe loading and unloading of materials and offering robust platforms for assembly and lifting operations. The erection of these provisional structures required careful design and execution to ensure their capacity to support the weight and dimensions of the equipment while withstanding the river’s current and diverse environmental conditions.

The general contractor’s proactive approach and effective partnership with Autoworld UK highlight the importance of strategic problem-solving in project management. The team adeptly resolved the logistical challenges of the river crossing by utilizing the expertise of specialized logistics suppliers and unconventional methods. This ensured that the project adhered to the deadline and that the trans-river tower installation was conducted without compromising safety or quality.

4. Discussion

This report offers significant insights into the procurement management challenges encountered by Chinese contractors in international EPC projects, especially with the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The research identifies many crucial areas where procurement inefficiencies, including communication delays, material shortages, and logistical obstacles, can severely impede project performance. Nonetheless, it illustrates how measures such as supply chain integration and stakeholder collaboration may alleviate these challenges and enhance procurement performance [88].

This study highlights the significance of supply chain integration in improving procurement efficiency. By consolidating procurement procedures over the whole project life cycle, Chinese contractors may mitigate delays, guarantee material availability, and diminish the risk of cost overruns. This corresponds with prior research that emphasizes the significance of supply chain integration in building projects. This study’s findings further demonstrate that in international EPC projects, where stakeholders encompass various countries and cultures, supply chain integration transcends logistics to include the alignment of communication, decision-making, and resource allocation processes. The effective integration of these procedures proved essential for maximizing procurement results and minimizing inefficiencies [1].

Collaboration among stakeholders emerges as a significant issue in the study. Efficient collaboration and communication among contractors, suppliers, subcontractors, and designers were identified as essential for facilitating seamless procurement and project execution. This underscores that procurement is not a solitary endeavor but a collaborative process involving several stakeholders whose activities are interconnected. Social network analysis (SNA) shown that robust, coordinated networks among stakeholders enhance resource allocation, expedite problem-solving, and mitigate procurement risks. This discovery underscores the necessity for Chinese contractors to cultivate robust, enduring relationships with overseas suppliers and subcontractors, a strategy that may be especially advantageous in projects characterized by intricate supply chains and varied stakeholders.

This study’s application of social network analysis (SNA) provides a unique contribution to procurement research. SNA offered a distinctive viewpoint on the influence of inter-organizational connections on procurement management in EPC projects. The results indicate that the prominence and robustness of linkages within the project network significantly affect procurement efficiency. Central stakeholders in the network, including primary suppliers or subcontractors, can enhance collaboration and expedite decision-making, hence minimizing delays and expenses. This underscores the necessity of meticulously maintaining stakeholder networks to guarantee the seamless flow of information and the prompt and precise execution of decisions. The function of Social Network Analysis in identifying pivotal actors and enhancing interactions among stakeholders warrants additional investigation, particularly in international and cross-cultural settings [2].

Furthermore, the survey indicates that procurement tactics, including just-in-time (JIT) inventory management, supplier relationship management, and the utilization of digital procurement platforms, are progressively being embraced by Chinese contractors to improve procurement performance. These solutions, although well-established in supply chain management, demonstrate notable efficacy in international EPC projects, where the control of supply chain risks is critical. The utilization of digital platforms facilitates real-time communication, improves transparency, and optimizes procurement procedures, hence reducing mistakes and delays [89].

The study highlights the competitive edge that supply chain integration and efficient stakeholder collaboration afford Chinese contractors in the global EPC industry. By enhancing procurement procedures and minimizing inefficiencies, Chinese contractors are more effectively positioned to compete with global enterprises. This is especially significant with the Belt and Road Initiative, where the growing number of multinational projects offers both benefits and constraints. The capacity to oversee intricate supply chains, alleviate procurement risks, and cultivate robust stakeholder relationships provides Chinese contractors a significant advantage in effectively obtaining and implementing overseas contracts.

This study underscores the essential importance of supply chain integration, stakeholder participation, and social network analysis in addressing procurement difficulties and enhancing project results in multinational EPC projects. The findings expand comprehension of how Chinese contractors may adeptly maneuver the intricacies of global procurement and improve their competitive stance in the international EPC market. Future study may investigate the influence of cultural variances on procurement methodologies, the function of technology in improving stakeholder participation, and the enduring advantages of strategic supplier partnerships in multinational initiatives [3].

Table 2 synthesizes the performance benefits of supply chain integration as demonstrated in the study, emphasizing its multifaceted value in addressing procurement challenges specific to Chinese contractors operating within complex international EPC environments.

Table 2.

Supply Chain Integration as a Strategic Framework for Procurement Management in International EPC Projects [1].

Supply chain integration emerges as a foundational strategy, transcending traditional logistics to encompass the holistic alignment of communication, decision-making, and resource allocation throughout the project lifecycle. This integration directly mitigates delays and cost overruns while ensuring material availability, thereby validating and extending previous construction management research to the complex, multi-cultural context of international EPC projects [1,88].

The critical role of stakeholder collaboration is equally prominent. Procurement is fundamentally a relational endeavor, where seamless coordination among contractors, suppliers, subcontractors, and designers determines project success. The application of Social Network Analysis (SNA) represents a distinctive methodological contribution, revealing that network centrality and linkage robustness are significant predictors of procurement efficiency. Central stakeholders—such as primary suppliers—act as collaboration catalysts, accelerating decision-making and problem-solving while reducing costs. This suggests that Chinese contractors must strategically invest in cultivating durable, trust-based relationships with overseas partners to navigate intricate supply chains effectively [2].

Furthermore, the adoption of established supply chain strategies—including just-in-time inventory management, supplier relationship management, and digital procurement platforms—demonstrates considerable efficacy in controlling supply chain risks. Digital tools, in particular, enhance real-time communication and transparency, optimizing processes and minimizing costly errors [89]. These integrated approaches collectively provide Chinese contractors with a measurable competitive edge in the global EPC market, positioning them more favorably against international competitors within the expanding BRI framework.

Future research should prioritize three interrelated areas: (1) examining how cultural differences influence procurement methodologies and stakeholder engagement dynamics; (2) exploring the evolving role of technology in facilitating cross-cultural collaboration; and (3) assessing the long-term sustainability and value creation of strategic supplier partnerships in multinational contexts. Such investigations would deepen theoretical understanding while providing practitioners with evidence-based strategies to sustain competitive advantages in an increasingly complex global procurement landscape [3].

5. Conclusions

This study offers significant insights into the procurement management challenges encountered by Chinese contractors in international EPC projects under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), emphasizing the need of supply chain integration and stakeholder participation. The results indicate that efficient supply chain integration markedly enhances procurement efficiency, minimizes delays, and decreases costs. Robust coordination among stakeholders—contractors, suppliers, subcontractors, and designers—is essential for reducing procurement risks and ensuring effective project execution. Furthermore, social network analysis (SNA) provides a distinctive viewpoint, emphasizing the significance of inter-organizational interactions and the pivotal role of important stakeholders in enhancing procurement results. Case studies demonstrate how tactics including just-in-time inventory management, supplier relationship management, and digital procurement platforms successfully mitigate supply chain risks and improve procurement performance in multinational EPC projects [90].

This study possesses many drawbacks. The research relies on a limited number of case studies from multinational EPC projects, which may not adequately reflect the variety of procurement management approaches across all international EPC projects. Secondly, whereas social network research offers significant insights into stakeholder connections, the influence of cultural disparities on procurement processes and stakeholder collaboration remains little examined. Cultural differences can significantly influence cross-border initiatives and impact the efficacy of supply chain integration. Ultimately, although the study emphasizes the utilization of digital procurement platforms and supply chain integration methodologies, their actual efficacy across various project types and scales need more confirmation.

Subsequent investigations may examine various critical domains: (1) Increasing the sample size to encompass a wider array of worldwide EPC projects across various locations and project kinds, to improve the generalizability of the results; (2) Examining the influence of cultural variances on procurement practices, especially in cross-cultural environments, to enhance comprehension of how culture affects stakeholder collaboration and supply chain integration; (3) Assessing the efficacy of digital procurement technologies across diverse project scales and complexities, to evaluate their practical applications and challenges; and (4) Investigating the long-term sustainability of supplier relationships in international projects, analyzing how strategic supplier partnerships impact long-term procurement performance and risk management [91].

Based on the study’s findings and identified gaps, the following recommendations are offered for Chinese contractors operating in international EPC projects:

First, contractors should prioritize establishing dynamic supply chain integration frameworks that embed cultural intelligence into their procurement strategies. This involves conducting pre-project cultural assessments to understand stakeholder values, communication preferences, and decision-making styles in host countries. By integrating cultural liaison officers or local procurement specialists into project teams, contractors can bridge cultural divides and facilitate more effective stakeholder coordination. Simultaneously, implementing standardized yet flexible digital procurement platforms with multilingual interfaces and region-specific compliance modules will enhance real-time collaboration. Contractors should also develop tiered supplier relationship management programs that categorize partners based on strategic importance, providing capacity-building support to key local suppliers to ensure long-term reliability and create mutually beneficial ecosystems that extend beyond single project cycles [90].

Second, to address the study’s limitations and strengthen organizational capabilities, contractors must institutionalize knowledge management systems that capture procurement performance data across diverse project scales and geographical contexts. This includes creating centralized repositories of case studies, risk scenarios, and cultural negotiation patterns to build organizational memory and reduce reliance on individual expertise. For enhanced risk mitigation, contractors should adopt hybrid inventory strategies that combine just-in-time principles with strategic buffer stock allocations based on country-specific risk indices (e.g., political stability, logistics infrastructure). Furthermore, establishing cross-project learning networks—potentially facilitated by industry associations or BRI-specific consortia—will enable contractors to share best practices, validate digital tool efficacy across different operational environments, and collectively develop standardized metrics for measuring long-term supplier relationship sustainability, thereby advancing the industry’s procurement maturity in the global EPC market [91].

This study enhances the comprehension of procurement management in multinational EPC projects, highlighting the essential significance of supply chain integration and stakeholder participation. The results offer theoretical and practical insights for Chinese contractors aiming to enhance procurement strategies and elevate project outcomes in the progressively globalized EPC market. Subsequent study will enhance these findings and yield more complete strategies for managing procurement in intricate international projects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H.; software, J.H.; validation, J.H.; formal analysis, J.H.; data curation, J.H.; writing—original draft preparation, J.H.; writing—review and editing, J.H.; supervision, K.K.O.; project administration, J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because it involved the collection of anonymized and aggregated survey data, which posed no risk to participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Participation was voluntary, and respondents were assured that their answers would remain anonymous and used solely for academic research purposes.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this article are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Faculty of Engineering at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University and Guangdong Electric Power Design Institute Co., Ltd. Special thanks are extended to Kelvin K. Orisaremi for his invaluable support of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BRI | Belt and Road Initiative |

| EPC | Engineering, Procurement, and Construction |

| SNA | Social Network Analysis |

| ENR | Engineering News Record |

| JIT | Just In Time |

| PMI | The Project Management Institute |

References

- Huang, J.; Li, S.M. Adaptive strategies and sustainable innovations of Chinese contractors in the Belt and Road Initiative: A social network and supply chain integration perspective. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Fu, X.; Chen, X.; Wen, X. Supply Chain Management for the Engineering Procurement and Construction (EPC) Model: A Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Li, S.M. Data-Driven Analysis of Supply Chain Integration’s Impact on Procurement Performance in International EPC Projects. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenherr, T.; Swink, M. Revisiting the arcs of integration: Cross-validations and extensions. J. Oper. Manag. 2012, 30, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, F.; Robinson, E.P. Flow coordination and information sharing in supply chains: Review, implications, and directions for future research. Decis. Sci. 2002, 33, 505–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]