Abstract

Critical mineral supply chains underpin electric mobility, power electronics, clean hydrogen, and advanced manufacturing. Drawing on the resource-based view (RBV), the relational view, and dynamic capabilities, we conceptualize advantage not as ownership of ore bodies but as orchestration of multi-tier resource systems: upstream access, midstream processing know-how, standards and permits, and durable inter-organizational ties. In a world of high concentration at key stages (refining, separation, engineered materials), full “decoupling” is economically costly and technologically constraining. We argue for structured cooperation among the United States, European Union, China, and other producers and consumers, combined with selective domestic capability building for bona fide security needs. Methodologically, we conduct a structured conceptual synthesis integrating RBV, relational view, dynamic capabilities, and network-of-network research, combined with a structured comparative policy analysis of U.S./EU/Chinese instruments anchored in official documents. We operationalize the argument via technology–material dependency maps that identify midstream bottlenecks and the policy/standard levers most likely to expand qualified, compliant capacity.

1. Introduction

Global decarbonization [1,2] and digitalization [3,4] are colliding with the physical constraints of minerals and material supply chains [5,6]. Batteries, permanent-magnet motors, power electronics, electrolyzers, and advanced semiconductors all depend on a small set of inputs whose refining and processing are geographically concentrated. The International Energy Agency (IEA) reports that the average market share of the top three refining countries for key energy minerals rose from ∼82% in 2020 to 86% in 2024, with roughly 90% of supply growth coming from a single leading supplier in each value chain (Indonesia for nickel; China for cobalt, graphite, and rare earths) [7]. Concentration is projected to remain high through 2035, declining only marginally even if announced projects proceed [7].

Public policy has become a structural feature of this supply environment. The European Union’s Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA) sets 2030 benchmarks for domestic capacity—≥10% extraction, ≥40% processing, ≥25% recycling—and a diversification target of ≤65% dependence on any single third-country supplier at each value-chain stage, with permitting pathways for designated “Strategic Projects” [8]. The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) has formalized a critical-material methodology based on “importance to energy” and “supply risk,” listing short-term criticals such as cobalt, dysprosium, gallium, natural graphite, iridium, and neodymium, and identifying near-critical concerns that include lithium, nickel, magnesium, and silicon carbide [9,10]. China, for its part, has introduced item-specific export licensing—not blanket bans—on gallium/germanium [11] items (announced July 2023) and on certain graphite products (effective 1 December 2023), framing these measures in national-security and non-proliferation terms and specifying permit procedures [12,13].

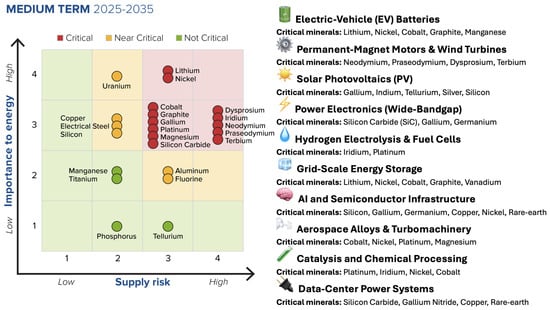

As shown in Figure 1, the Department of Energy’s critical-mineral assessment [9] highlights how strategic vulnerability and technological indispensability intersect in the midstream of the energy transition. Materials such as lithium, nickel, cobalt, and graphite anchor electrochemical storage, while rare-earth elements—including neodymium, praseodymium, dysprosium, and terbium—enable high-efficiency motors and wind-turbine generators. Gallium and silicon carbide underpin next-generation power electronics, and platinum-group metals such as iridium and platinum are irreplaceable for hydrogen electrolysis and fuel-cell catalysis. Collectively, these materials form the “red quadrant” of the DOE matrix, where both importance to energy and supply risk are high. Their clustering reveals that the bottlenecks shaping decarbonization are not purely geological but embedded in refining, separation, and qualification capabilities concentrated in a few countries. This observation motivates the cooperation-first framework advanced in the paper—prioritizing joint standards, reciprocal market access, and predictable licensing to mitigate supply risk without fragmenting global innovation networks.

Figure 1.

DOE Critical Minerals Matrix (2025–2035) and Associated Technology Systems. The left panel reproduces the U.S. Department of Energy’s medium-term criticality assessment, plotting materials by importance to energy (vertical axis) and supply risk (horizontal axis). Red indicates critical, yellow near-critical, and green not-critical status. Based on [9].

This paper adopts a cooperation-first stance. Full “decoupling” or severe tariff wars [14,15] of mineral and material supply chains would be economically costly [16], slow [17], and technologically constraining [18] because the most capability-intensive steps—separation, refining, metalization, and engineered materials (e.g., NdFeB magnets [19]; anode-active materials)—are where scale, tacit know-how, and qualification standards congeal. The permanent-magnet case illustrates the point: China accounted for about 92% of global NdFeB magnet manufacturing in 2020, alongside dominance in upstream separation/metalization [20]. Replicating that midstream ecosystem wholesale would require long lead times, large capital outlays, and parallel testing/qualification regimes. A more practical path is structured cooperation—reciprocal market access [21,22], co-investment at bottlenecks, interoperable testing/traceability [23], and predictable licensing [24,25], paired with targeted domestic capability [26] where bona fide national-security or continuity-of-supply needs justify it [27]. That approach aligns with official analyses projecting persistent midstream concentration even under optimistic investment scenarios [7].

1.1. Conceptual Lens: From RBV to a Network-RBV

We frame the issue using the resource-based view (RBV) [28,29] and the dynamic-capabilities perspective. Under RBV, sustained advantage stems from resources and capabilities that are valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable [28,30,31,32]. Dynamic capabilities emphasize a firm’s ability to sense, seize, and transform as conditions change [33,34]. Applied to critical-mineral supply chains, the relevant “resources” extend well beyond ore bodies to include the following: (i) access rights and permits; (ii) midstream know-how and capacity (separation, refining, alloying, component manufacturing); (iii) standards, certifications, and supplier qualification records; (iv) relational assets such as long-term offtakes and joint ventures; and (v) reconfiguration capabilities—switching chemistries, routes, or partners.

Public policy is not a mere backdrop; it is part of the resource environment that shapes appropriability, imitability, and timing [35]. CRMA’s benchmarks and permitting clocks, DOE’s material lists and matrices, and China’s item-specific licensing all influence the isolating mechanisms around midstream capabilities without foreclosing trade when documentation and scope are clear [8,10,12,20]. We label this synthesis a network-RBV, which integrates insights from the resource-based view (RBV), dynamic capabilities, and network-of-network theory. Traditional RBV highlights firm-level resources as the foundation of advantage [28,29], while dynamic capabilities extend this lens to explain how organizations reconfigure assets in turbulent environments [34,36]. Recent research on intertwined supply networks and network-of-networks [37,38] demonstrates that resilience and innovation increasingly emerge at the level of interconnected systems rather than isolated chains. Building on these strands, the network-RBV posits that advantage in technology races (e.g., EVs, wind, hydrogen, power electronics, AI infrastructure) [39,40,41] is generated not by any single firm or country, but by orchestrated systems of resources spanning borders. In practice, such a system might combine one region’s upstream access with another’s separation capacity and a third’s component engineering, linked through standards and qualification data that reduce friction. The more concentrated and tacit the midstream step, the higher the returns to cooperative orchestration relative to do-it-alone replication.

1.2. Interdependence with Real Security Frictions

Three stylized facts motivate a cooperation-first posture. First, demand is rising but investment signals softened in 2024: following sharp price surges in 2021–2022, prices for key energy minerals declined, with lithium falling markedly since 2023; exploration and investment growth slowed relative to prior years [7]. Second, concentration is greatest in midstream stages—refining/processing, engineered materials, and often recycling—where top-three shares remain elevated and projected balances are tight in many materials through 2035 [7]. Third, policy frictions are real and expanding: since 2023, export controls and licensing measures have increased in number and scope; Chinese authorities emphasize that licensing permits compliant exports—a practical nuance for firms planning cross-border R&D and trade [7,12].

These facts argue for practical interdependence. Countries can and should reduce single-point exposures for defense and critical-infrastructure uses. Yet most will still rely on cross-border flows of intermediates and components for the foreseeable future. As an illustration, even with new projects in multiple regions, today’s baseline—where oxide separation, metalization, and NdFeB magnet fabrication are concentrated—means allied efforts will take time to scale; during that interval, standard alignment, predictable licensing, and qualification-aware contracts can deliver near-term resilience gains [20].

1.3. Contribution and Stance of This Paper

This paper makes three contributions. First, it develops a neutral, policy-aware network-RBV that treats public instruments (benchmarks, permitting clocks, item-specific licensing, standard/qualification regimes) as meta-resources shaping firm- and alliance-level capabilities [8,9,12]. Second, it maps technologies to materials and chokepoints, highlighting midstream steps where joint standards, reciprocal market access, and co-investment are most likely to reduce risk without fragmenting supply [7]. Third, it advances a cooperation-first agenda: build selective in-house capability for clearly sensitive nodes (e.g., particular magnet grades; critical catalyst preparation/recovery), while structuring cross-border deals—of the kind the CRMA explicitly envisions—to diversify sources under clear test and documentation rules [8].

2. Network-RBV for Critical-Mineral Supply Chains

We use this policy footing to motivate the shift from a firm-centric RBV to a network-RBV (Table 1) [8,10,42,43].

Table 1.

Policy positioning of selected materials across U.S., EU, and China.

The resource-based view (RBV) is the right starting point, but mineral supply chains push it beyond the firm [28,29,30]. Classic RBV argues that advantage rests on resources and capabilities that are valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable [28,32]. In minerals, the attributes that determine performance and risk live in midstream transformations: separation, refining, metalization, engineered materials [51] (e.g., NdFeB magnets), anode-active materials [52], and catalyst preparation/recovery [53]. These steps accumulate tacit routines, long qualification records, and process control that are difficult to purchase and slow to copy [54]. The theoretical move is to therefore relocate RBV’s locus: from the single firm to the network that turns raw inputs into qualified intermediates for downstream technologies.

Two observations drive the shift. First, the hard problem is rarely discovering ore; it is producing consistent, qualified inputs—turning rare-earth oxides into magnet alloys, precursor salts into uniform cathode powders, metallurgical silicon into device-grade carbides, or spent catalysts into reusable iridium [55,56]. Second, the “glue” that makes these capabilities usable—permits, standard access, accreditation, long-dated offtakes, and predictable licensing—is itself a scarce, time-intensive asset, often co-created with partners and regulators [8,10]. In minerals, then, VRIN properties are frequently network-level: what matters is the orchestrated bundle of access, processing, logistics, certification, and relationships rather than any single plant.

This intuition aligns with the network-of-network view [37,38]. Specifically, performance comes from the parallel alignment of several overlapping layers, not a single supplier graph [37]. In the context of critical minerals, a route is usable only if it is open simultaneously across four layers: physical flow (plants, ports, logistics) [57], contract/control (offtakes, tolling, audit rights) [58], standards/qualification (tests, certificates, serial status), and licensing/compliance (item-specific scopes, permits, documentation) [59]. A path for cathode precursor, magnet alloy, or anode-active material is feasible only when it exists in all four; the firm’s effective endowment is therefore the intersection of what it owns, controls, or can access across these layers [60]. Seen this way, policy instruments are layer editors that reshape multi-layer reachability. Permitting clocks and “Strategic Project” status expand physical-flow options; long-dated offtakes and co-investment strengthen the contract layer; standards and MRAs make qualification portable; item-specific licensing clarifies which compliance edges are open. In combination—and this is the cooperation-first payoff—these edits enlarge the multi-layer intersection, creating more parallel, qualified, and permitted routes, lowering switching costs and shortening time-to-serial status without fragmenting trade.

Within this frame, policy operates like a meta-resource in concentrated midstreams. Four instrument families are pivotal. Eligibility and benchmark regimes (criticality lists; processing/extraction/recycling targets) channel demand and finance toward qualified nodes, altering appropriability. Permitting clocks and strategic-project status compress time-to-imitate for credible entrants without lowering technical standards. Item-specific licensing and compliance scopes add predictability at sensitive nodes while still allowing legitimate trade under clear documentation. And standards plus mutual-recognition arrangements (MRAs) make test results portable across jurisdictions, reducing repeated qualification and shrinking switching costs [8,10]. Designed well, these instruments are coordination devices: they enlarge the set of reliable suppliers and accelerate time-to-serial status, rather than fragmenting trade.

Dynamic capabilities take on a particular texture here. Sensing is not just watching prices; it includes monitoring standard bodies, permitting practice, and chemistry pivots. Seizing means securing tolling capacity, signing offtakes that underwrite expansions at bottlenecks, and standing up shared pilot lines to generate serial-status data. Transforming involves designing for material flexibility, modularizing flowsheets to tolerate variable feed, and relocating steps or partners when routes change. Crucially, cooperation amplifies these capabilities: common test protocols and reciprocal acceptance shorten qualification; predictable licensing turns uncertainty into a manageable schedule variable; scoped data exchange reduces duplication.

Because many VRIN (Valuable, Rare, Inimitable, and Non-substitutable) attributes [61] lie outside the focal firm, governance is central. Long-term offtakes stabilize flows and make expansions financeable, but they must preserve multi-sourcing to avoid lock-in. Tolling and joint ventures can share tacit know-how while protecting IP and compliance obligations if audit rights and change-control are clear [62,63]. Standard bodies reduce switching costs when they specify a minimal, performance-relevant test set with transparent uncertainty bounds and sampling plans.

We distill the logic into four connected claims. First, the advantage of mineral-intensive technologies stems from systems, not single assets: upstream access, midstream processing and qualification know-how, logistics and recovery loops, standard access, and long-dated contracts. The VRIN property is often network-level [64], and the managerial problem is orchestration. Second, public instruments act as isolating mechanisms that can integrate or fragment markets; when eligibility lists, diversification benchmarks, permitting clocks, licensing scopes, and MRAs are aligned, they lower switching costs and broaden cooperative equilibria—without broad decoupling [8,10]. Third, dynamic capabilities and cooperation are complements: sensing, seizing, and transforming pay off more when tests and data are interoperable and market access is reciprocally predictable [33]. Fourth, proximity to bottlenecks magnifies rent potential; co-investment and standard harmonization at separation, metalization, engineered materials, epitaxy, and catalyst preparation/recovery deliver the largest system-wide resilience gains.

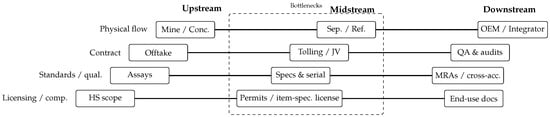

Figure 2 makes the network-RBV idea operational. The top row traces the material from Mine/Concentrate to Separation/Refining and on to the OEM/Integrator—a straight physical path. Beneath it, the contract/control row shows the legal and financial rails that make that movement enforceable: an Offtake upstream, Tolling/JV agreements at midstream, and downstream QA and audit rights. The standard/qualification row captures technical acceptance: upstream assays establish baseline quality; midstream specs and serial status reflect qualification data and durability testing; downstream MRAs/cross-acceptance make those results portable across jurisdictions. The licensing/compliance row shows regulatory feasibility: upstream HS (Harmonized System) [65] scope clarifies product definitions; midstream permits/item-specific license (e.g., for certain graphite or Ga/Ge items) determine whether exports are lawful; downstream End-use docs complete the file. The single horizontal line in each row represents one candidate route; it is only truly available when the same node sequence is open in parallel across all rows. This is the practical meaning of the firm’s effective resource endowment: what it owns/controls/accesses intersected with what is multi-layer reachable. The midstream dashed frame emphasizes where tacit know-how and long qualification cycles concentrate (separation/refining, tolling/JV execution, specification/serial status, permitting/licensing). Cooperation-first levers work by editing layers to increase overlap—accelerating permits, underwriting tolling via offtakes, standardizing tests and recognizing results, and publishing predictable license scopes—thereby creating more parallel, qualified, and permitted routes through the network without duplicating entire supply chains.

Figure 2.

Network-of-network RBV: a route is usable only if the same path exists across physical, contract, standard, and licensing layers; the dashed box marks midstream bottlenecks where policy can expand multi-layer reach.

The scope is broad but not universal. Where a material is readily substitutable at design time or qualification is trivial; the “network premium” shrinks and competition looks like a commodity market. Where a node is tied to defense or critical-infrastructure uses and subject to stringent controls, the feasible set for cooperation narrows; there, the pragmatic move is a minimum viable domestic capability [66] kept warm and sized to a quantified risk window—plus mutually recognized stockpiles, while leaving the wider commercial ecosystem integrated.

The pay-off of a network-RBV is practical clarity. It explains why full “decoupling” is costly and hard-to-imitate capabilities [67] sit in midstream nodes with long qualification cycles—and why cooperation is not naïve: interoperable tests, reciprocal recognition of accredited results, predictable licensing, and co-investment at bottlenecks are capability multipliers that expand reliable access without diluting legitimate security controls [8,10]. The rest of the paper operationalizes these ideas by (i) mapping technologies to materials and identifying where bottlenecks sit today, (ii) comparing the principal policy instruments of the United States, European Union, and China as elements of the resource environment, and (iii) detailing cooperation designs—standards, reciprocal access, shared pilot lines, and data interoperability [68].

Despite growing work on critical-mineral risk and intertwined supply networks, three gaps remain. First, much of the discussion is still implicitly upstream- and ownership-centered, whereas the most binding constraints frequently sit in qualification-heavy midstream transformations (separation, refining, engineered materials). Second, network-of-network resilience research often characterizes structure and propagation but does not connect bottlenecks to RBV-style isolating mechanisms (rarity, inimitability, time-to-copy) that explain why some nodes remain durable chokepoints. Third, policy instruments are typically treated as external “context,” rather than as rule systems that directly alter what firms can reliably own, control, or access across layers (physical, contract, standards, licensing). This paper addresses these gaps by proposing a network-RBV that endogenizes policy as a meta-resource and makes bottlenecks operational through technology–material mapping.

- Research problem. Critical-mineral vulnerabilities are increasingly shaped by midstream capabilities—qualification-heavy processing, engineered materials, and compliance regimes—rather than ore ownership alone. Yet existing supply-chain and network-of-network research rarely connects these bottlenecks to RBV-style isolating mechanisms and to public policy instruments as part of the resource environment.

- Research questions:

- How do public instruments (benchmarks, permitting, licensing scopes, standards/MRAs) function as meta-resources that reshape network-level VRIN attributes in critical-mineral supply systems?

- Under what boundary conditions does a cooperation-first governance design expand the effective resource endowment at bottlenecks more efficiently than wholesale replication/decoupling?

- Propositions:

- (Network-level VRIN) In qualification-heavy midstreams, the locus of VRIN attributes shifts from firm-owned assets to multi-party resource systems (owned, controlled, and accessed capacity across the network).

- (Policy alignment effect) Standard interoperability and mutual recognition agreements (MRAs), together with predictable licensing scopes, increase the set of feasible multi-layer routes and reduce switching and qualification costs.

- (Cooperation × dynamic capabilities) The returns to sensing–seizing–transforming capabilities are higher in rule-aligned networks than in fragmented regimes.

- (Boundary conditions) The network-RBV is most applicable where concentration, tacit know-how, and long qualification cycles dominate; it weakens for commodity-like, easily substitutable nodes and narrows in tightly controlled defense applications where minimum viable domestic capability is rational.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 develops the network-RBV mechanism and defines effective resource endowment in multi-layer networks, addressing RQ1 conceptually. Section 3 applies this lens to compare policy instrument families across jurisdictions and clarifies how they edit multi-layer reachability. Section 4 operationalizes the framework through a technology–material mapping that locates qualification-heavy midstream bottlenecks. Section 5 translate these mechanisms into governance implications and theoretical contributions, and we conclude by summarizing boundary conditions and a testable empirical agenda linked to RQ2.

We restricted policy evidence to primary, official sources (statutes, agency reports, and official criticality lists) for the U.S., EU, and China, prioritizing documents from 2018 onward and supplementing with earlier foundational instruments where necessary to ensure continuity. Academic sources were selected through targeted searches spanning the resource-based view, relational view, dynamic capabilities, and network-of-network/resilience literature, prioritizing peer-reviewed studies and widely cited foundational works, complemented by recent sector-specific research on supply chain collaboration and resource-critical industries. Policy instruments were coded into four families—benchmarks/eligibility, permitting/strategic projects, licensing scopes, and standards/mutual recognition agreements (MRAs)—and compared based on how each shapes multi-layer route feasibility and the portability of qualification and compliance across jurisdictions.

3. Operationalizing Network-RBV: Policy Instruments, Bottlenecks, and Technology Systems

This section operationalizes the network-RBV framework by moving from theory to practice. It examines how critical-mineral vulnerabilities are shaped, mitigated, and sometimes amplified through concrete policy instruments, technology–material dependencies, and governance choices at qualification-heavy midstream nodes. Rather than treating policy and technology as separate domains, the chapter shows how benchmarks, permitting regimes, licensing scopes, standards, and mutual recognition arrangements jointly determine which supply routes are feasible, compliant, and scalable in practice.

The section proceeds in four parts. It first compares the institutional landscapes of the United States, the European Union, and China, highlighting how different policy toolkits edit access to critical materials and midstream capabilities. It then maps priority technologies to their material dependencies and identifies where bottlenecks truly reside, emphasizing refining, engineered materials, and qualification-intensive processes rather than upstream extraction alone. The third section extends this logic to AI infrastructure, demonstrating how advanced packaging, power electronics, optics, and facility equipment embed new critical-mineral constraints. The final section synthesizes these insights through comparative case studies, illustrating how different governance approaches affect the portability of qualified capacity and the scope for cooperation-first strategies. Together, the chapter grounds the network-RBV in observable policy and technological systems and clarifies where coordinated rules and targeted investment can most effectively expand resilient, compliant supply.

3.1. Institutional Landscape and Policy Instruments

A cooperation-first strategy has to begin with how the major jurisdictions define the problem and set the rules. The United States, the European Union, and China use different toolkits, yet they now share a recognizable architecture: (i) taxonomies of “critical/strategic” materials; (ii) targeted support for midstream steps (separation, refining, engineered materials, recycling, standards/testing); and (iii) eligibility or licensing rules for specific items. Reading through our network-RBV lens, these instruments act as meta-resources: they shape appropriability and imitability at bottlenecks and, depending on design, can either fragment markets or—preferably—coordinate them [8,9,10].

The U.S. Department of Energy’s Critical Materials Assessment (CMA) provides the policy grammar—“importance to energy” × “supply risk”—and an accompanying list that guides R&D, demonstrations, standard work, and procurement-relevant programs [9,10]. The CMA identifies short-term criticals/near-criticals—including lithium, natural graphite, cobalt, dysprosium, neodymium, terbium, gallium, iridium, and silicon carbide—and, crucially, directs attention to midstream capacity and qualification, not only upstream mining [9]. The USGS Mineral Commodity Summaries supply the statistical backbone—production, trade, and U.S. import reliance—which firms and governments use as a common baseline [69,70,71].

The Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA) translates strategy into clear 2030 benchmarks—at least 10% extraction, 40% processing, 25% recycling of EU consumption for strategic raw materials—and a ≤65% exposure cap to any single third-country supplier at each value-chain stage, with permitting pathways for designated Strategic Projects [8].

Rather than a single public list analogous to CMA/CRMA, China relies on sectoral industrial policy and item-specific export licensing at sensitive nodes. Two measures are especially relevant to midstream bottlenecks discussed in this paper: (i) controls on gallium/germanium-related items (announced July 2023, implemented 1 August 2023) and (ii) a permit regime for certain graphite products (effective 1 December 2023) [12,13].

Standards and mutual recognition. Concentrate standard-setting and MRAs where VRIN-like attributes reside: rare-earth separation/metalization and magnet fabrication; anode-active material processing; catalyst preparation/recovery for PEM; and SiC/GaN epitaxy/wafering. A minimal, performance-relevant test set—e.g., coercivity/temperature stability for magnet grades; PSD/BET/first-cycle efficiency for graphite AAM; dislocation densities and reliability tests for SiC/GaN; iridium loading and mass-activity for PEM—paired with MRAs can reduce redundant testing and shorten time-to-serial status [8,9].

Reciprocal market-access compacts. Where one side brings offtake certainty and the other installed midstream know-how, long-dated purchase agreements with embedded qualification plans (ramp gates, acceptance limits, change-control) make expansions financeable without over-committing either party. USGS baselines help size minimum viable domestic capability for defense/continuity needs without duplicating entire chains [69].

Licensing dialogues as technical workstreams. In the gallium/germanium and graphite cases, published scope definitions and document requirements allow firms to plan logistics and R&D within known lead times. Regular technical consultations among agencies, standard bodies, and industry can narrow interpretive gaps (tariff lines, purity thresholds, “de minimis” recycled content) and reduce the risk premia that deter midstream investment [12,13].

Shared diagnostics. Recent assessments emphasize that demand for energy-relevant minerals is still rising and refining/processing concentration remains high, even as new projects are announced—one reason decoupling would be slow and costly, and why co-investment at bottlenecks, standard reciprocity, and predictable licensing deliver outsized returns [7,8,9,69].

Each side has legitimate objectives; none benefit from supply fragmentation at scale. The instruments already on the books—CMA matrices and USGS baselines in the U.S., CRMA benchmarks and permitting in the EU, and item-specific licensing (and significant midstream capacity) in China—are compatible with a cooperate-where-you-can, invest-where-you-must posture. Used together, they enlarge the reliably accessible portion of the global resource system while preserving space for targeted domestic capability where continuity genuinely requires it [8,9,12].

3.2. Technologies, Materials, and Where the Bottlenecks Really Are

Technology selection followed two inclusion rules: (1) technologies central to energy transition and/or AI infrastructure and (2) technologies whose performance depends on a narrow set of materials with qualification-heavy midstream transformations. Material dependencies were drawn from DOE criticality assessments and supporting technical sources, cross-checked against EU CRMA documentation and IEA supply concentration discussions. Bottlenecks were labeled ‘make-or-break’ when the midstream step simultaneously exhibited high concentration, long qualification cycles, and low short-run substitutability at design time. Table 2 links priority technologies to their material dependencies and identifies the midstream transformations—separation, refining, metalization, engineered materials, catalyst preparation, and recycling—where tacit know-how and qualification data concentrate. To keep the paper factual and neutral, the “policy levers” column anchors to official, stable sources [8,9,12,13,69]. The short narratives that follow place those nodes in a cooperation-first frame: standards and reciprocal recognition to lower switching costs; reciprocal market access and offtakes to underwrite expansions; targeted domestic capability where bona fide security or continuity requires it. “Make-or-break stage” names the step where capabilities are hardest to imitate quickly and where qualification, standards, and compliance dominate timelines.

Table 2.

Technologies, salient materials, and midstream bottlenecks; official policy levers.

A few cross-cutting facts motivate the cooperation-first stance that runs through the paper. Refining and processing are concentrated: the International Energy Agency reports that the average market share of the top three refining countries for key energy minerals rose markedly between 2020 and 2024, with much of the growth attributed to a single leading supplier across several value chains; this concentration is expected to persist into the 2030s even as new projects come online [7]. This is precisely why coordinated standards, reciprocal market access, and co-investment at midstream nodes dominate the near-term resilience agenda [7,8].

The NdFeB case illustrates how value and risk accumulate as we move downstream. DOE’s supply-chain work shows concentration increasing from mining to separation, metal refining, and magnet manufacturing; by 2020 the dominant producer accounted for the overwhelming share of global magnet output—the stage with the highest added value [9]. The U.S. Section 232 report synthesizes similar conclusions and, notably, does not recommend broad import restrictions, emphasizing allied cooperation and targeted capability building [20]. In network-RBV terms, the rent-bearing assets are not ore bodies but the tacit routines, qualification data, and process control that turn separated oxides into consistent magnet alloys and finished magnets. Cooperation that aligns grade and durability testing, enables reciprocal audit recognition, and uses long-dated offtakes to underwrite expansions that lower imitation and switching frictions without excluding compliant incumbents [8].

For graphite anodes, the capability bottleneck is the anode-active material (AAM) step for both synthetic and natural graphite. This is where impurity control, particle morphology, coating, and binder systems are qualified over long cycles with cell makers. DOE’s assessment treats natural graphite as a short-term critical; USGS tracks market structure and—importantly, for firms—documents the evolving U.S. trade baseline and policy context [9,70]. Since 1 December 2023, certain graphite products require export permits from China; authorities have characterized this as a licensing system with specified documentation [13]. For cooperation, that implies designing commercial flows and R&D exchanges around predictable license scopes and interoperable AAM testing protocols. Under the EU’s CRMA benchmarks, reciprocal recognition of test data and sustainability audits can accelerate diversification while keeping legitimate cross-border trade and joint pilot lines on stable, rule-based footing [8].

In hydrogen PEM, the scarcest capability is not a mine but a catalyst system containing the following: iridium loadings, fabrication, and especially recycling. DOE’s critical-material work highlights iridium as a short-term concern for energy technologies; NREL analyses emphasize that cost and scalability hinge on lowering Ir loadings and closing recycling loops [9,72]. A cooperation-first approach focuses on shared standards for recycled catalyst feed, durability testing protocols, and data sharing on degradation so that refurbished or recycled materials qualify across jurisdictions.

For power electronics (SiC/GaN), the bottleneck is epitaxy and wafering—a tooling-intensive step with long qualification cycles. DOE flags SiC within energy-relevant materials; reliability standards and device-qualification protocols function as the principal isolating mechanisms [9]. Given lead times for epi tools and fabs, the fastest way to reduce risk is standard reciprocity across reliability testing and reciprocal market access for epi/wafer supply under well-understood compliance regimes, while building limited in-house capability for defense-critical uses; this aligns with CRMA’s design to diversify through a mix of domestic projects and qualified third-country partnerships [8].

Two synthesis points follow. First, the hardest-to-replicate capabilities are midstream and deeply intertwined with standards, qualification records, and compliance. That is why abrupt decoupling is slow and expensive, and why structured cooperation—joint standards, reciprocal audit recognition, transparent licensing, and purchase commitments that underwrite expansions—delivers resilience faster [8,9]. Second, where national-security or continuity-of-operation concerns are material (certain magnet grades; specific catalyst functions), selective domestic capability and mutually recognized stockpiles provide insurance without fragmenting the wider ecosystem [7]. These conclusions are consistent with the IEA’s finding that refining concentration remains high even with an expanding project pipeline and with the EU’s preference, in CRMA, for meeting benchmarks via domestic projects and third-country partnerships [7,8].

This sets up the next step. The logic of a network-RBV implies that governance—contracts, standards, data, and finance—is capability. The following section moves from “where the bottlenecks are” to “how to govern them”: templates for offtakes that include qualification; tolling and JV structures with IP and compliance guardrails; mutual-recognition arrangements for testing and traceability; shared pilot-line governance; and practical definitions of minimum viable domestic capacity for genuine security use-cases [8,9,69]. The aim is not to prescribe a single model but to lay out a cooperation-first toolkit that countries and firms can adapt while keeping the system open, predictable, and resilient.

3.3. Why Critical Minerals Matter for AI Infrastructure

Artificial-intelligence capability is ultimately bounded by physical infrastructure: chips and memory, server and storage assemblies, optical interconnects, and the power systems that feed ever-denser racks. Each layer leans on a distinct set of minerals and engineered materials, with the tightest constraints sitting in midstream steps such as advanced packaging, high-efficiency power conversion, and precision magnetics. This section maps those links and ties them back to our cooperation-first stance: target the true bottlenecks with standards, predictable licensing, and bankable offtakes—while building limited in-house capacity only where continuity or security demands it.

Modern AI accelerators combine advanced-node logic dies with high-bandwidth memory (HBM) stacks [73] joined by through-silicon vias (TSVs) on silicon interposers [74]. The material stack is broader than “just silicon”: TSVs and fine-pitch interconnects are metalized (commonly copper with liners), and the interposer/stack adds multiple lithography, etch, dielectric, and metallization steps. Industry sources describe additional material-engineering steps beyond conventional DRAM to build HBM (TSV etch/fill, insulation, and interposer connections) [75]. Demand pressure is acute because HBM is produced by a handful of firms; packaging innovations (larger interposers, new substrates) have become national priorities, as illustrated by news on Japan’s interposer initiatives aimed at cost and throughput gains for multi-chiplet processors [76].

At the server level, AI racks concentrate far more power per unit volume; every point of conversion loss translates into extra heat and cost. Two shifts are visible. First, hyperscalers have moved from 12 V to 48 V rack distribution to cut resistive losses and cable bulk—codified in Open Compute Project (OCP) requirements and widely deployed [77,78]. Second, power supplies and rectifiers are adopting wide-bandgap devices—GaN at lower voltages and SiC at higher powers—for PFC and DC–DC stages, improving efficiency and power density relative to silicon switches [79,80,81]. On storage, hard-disk drives (HDDs) remain dominant for cold and warm tiers in cloud centers, which keeps Nd–Fe–B magnets (Nd/Pr with Dy for high-coercivity grades) embedded in large populations of voice-coil and spindle motors. Cloud providers and drive makers have publicized programs to capture and reuse these rare-earth materials from retired drives, while analyst/industry reporting notes continued growth in nearline HDD exabyte shipments [82,83].

Inside and between racks, optical I/O increasingly limits AI cluster scale. Today’s pluggable and co-packaged optics marry silicon photonics (waveguides, modulators) with III–V lasers (commonly indium phosphide) through hybrid or heterogeneous integration. Academic and industry sources converge: Si photonics handles routing and modulation cost-effectively, while InP-family materials supply efficient light sources and detectors, with the ecosystem racing toward higher lane rates and 1.6 Tb/s modules [84,85,86]. For our purposes, AI networking leans on indium, phosphorus, and (in some devices) gallium/arsenic alongside silicon, plus precision packaging metals and ceramics.

The step change in rack power (often tens of kW per rack, and much higher for AI pods) ripples outward to the building and grid interfaces. Three material groups dominate: (i) copper and aluminum for conductors, busbars, and switchgear—data center power-distribution equipment accounts for a large share of site copper [87]; (ii) transformer steels (grain-oriented silicon steel) and copper windings for medium- and high-voltage interconnects, with utilities and suppliers flagging tighter transformer markets as AI-driven loads climb [88,89]; and (iii) wide-bandgap semiconductors (SiC/GaN) again—this time in building-scale rectifiers, UPSs, and high-efficiency power shelves [79,81,90].

The International Energy Agency projects that data-center electricity demand could more than double by 2030 to roughly 945 TWh, with AI-optimized facilities a leading driver [7]. Even under that growth, data centers remain a minority share of global demand growth—but local impacts on siting, interconnection queues, and long-lead equipment are non-trivial, explaining why some operators pursue behind-the-meter generation and accelerated interconnects [91]. Forecast-oriented analyses expect rising demand for copper (conductors, busbars) and transformer capacity tied to AI build-outs, and increased SiC/GaN content in PSUs/UPSs [92,93,94].

Three points follow from the AI stack. First, bottlenecks are midstream and qualification-heavy: advanced packaging (HBM + interposers), optical modules (Si photonics + InP lasers), and wide-bandgap power stages (epi/wafer and device fabrication) concentrate tacit know-how and long test cycles—precisely where shared test protocols, mutual recognition of accredited results, and qualification-aware offtakes pay off [75,79,84]. Second, the power plane is a material problem: copper, aluminum, silicon-steel, and WBG devices determine how quickly sites scale and how efficiently racks run [92,93,94]. Third, magnets and storage remain non-trivial: even as SSDs expand for hot tiers, hyperscale archives lean on HDDs—so predictable access and, where sensible, recovery loops at decommissioning help stabilize supply [82].

For HBM/interposers, push common acceptance tests for TSV/interposer reliability and thermo-mechanical stress, and structure offtakes that underwrite additional stacking and packaging capacity with explicit qualification gates [75]. For optics, treat InP–Si hybrid integration as a shared platform and align reliability tests for lasers and modulators so suppliers qualify across jurisdictions without duplicating months of testing [84,85]. For power shelves/UPS, codify WBG device test suites and sampling plans so GaN/SiC modules qualified in one region move faster elsewhere and fold licensing/classification notes into purchase contracts to de-risk lead times [79,90]. For facility equipment, long-lead transformers and high-capacity switchgear benefit from reciprocal procurement visibility and scheduling norms; the mineral inputs (silicon-steel, copper) are not exotic, but the timelines are [88,89].

3.4. Comparative Policy Case Studies: How the U.S., EU, and China Address Critical-Mineral Bottlenecks

This section provides three short case studies that illustrate how the United States, the European Union, and China each address the critical-mineral problem through distinct mixes of diagnostics, capacity-building, and rule-setting. Read through the network-RBV lens advanced in this paper; the common thread is that policy is not merely background context: it directly edits the feasibility of qualified, compliant routes through the multi-layer network (physical flow, contracts, standards/qualification, and licensing). The cases differ primarily in which layer is emphasized, and in how predictability is produced for private actors planning investments at qualification-heavy midstream nodes Table 3.

Table 3.

AI infrastructure: technologies, salient materials, midstream bottlenecks, and policy/standard levers.

3.4.1. Case Study 1: United States—Risk-Based Criticality and Targeted Midstream Scale-Up

The U.S. approach is anchored in a risk-based diagnostic that explicitly links materials to energy technologies through a two-dimensional framework: “importance to energy” and “supply risk.” The Department of Energy’s Critical Materials Assessment (CMA) evaluates material criticality using this structure and, in doing so, places attention not only on upstream extraction but also on midstream constraints that determine whether supply is usable for downstream technologies, including processing capability, reliability, and qualification frictions [9]. Complementing the analytical assessment, the DOE has also formalized the 2023 Critical Materials List via a Federal Register notice, providing an official reference point that supports coordination across public programs and private planning [95].

A salient implementation example is the DOE’s December 2025 announcement of up to USD 134 million in funding to strengthen rare-earth element supply chains. The announcement frames the effort as support for commercially viable pathways to recover, refine, and scale rare-earth supply chains, aligning directly with the midstream and qualification-heavy steps where durable capability tends to reside [96]. In network-RBV terms, the key strength of this approach is its coherence: a transparent prioritization grammar (importance × risk) that is explicitly tied to instruments intended to expand qualified capacity at bottlenecks, thereby enlarging the reliably accessible portion of the global resource system without requiring economy-wide decoupling [9,96].

3.4.2. Case Study 2: European Union—Binding 2030 Benchmarks and Strategic Projects Under the CRMA

The EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA) translates strategic concern into measurable, time-bound benchmarks across the supply chain. The Commission’s CRMA materials emphasize 2030 capacity targets for strategic raw materials—10% extraction, 40% processing, and 25% recycling—and a diversification constraint that seeks to limit dependence on any single third country to no more than 65% of annual EU needs at each relevant stage [8,97]. These commitments are notable because they treat midstream scale-up as a policy object in its own right, rather than as an assumed consequence of upstream development. In the logic of network-RBV, such benchmarks function as meta-resources that can re-shape appropriability and time-to-imitate by concentrating finance, permitting attention, and industrial coordination at qualification-heavy nodes [97].

Operationally, the CRMA’s “Strategic Projects” mechanism is designed to accelerate delivery by coordinating investment and streamlining processes for designated projects. In March 2025, the Commission adopted, for the first time, a list of 47 Strategic Projects intended to boost domestic strategic raw material capacities, providing a concrete implementation channel for the Act’s benchmarks. From a bottleneck perspective, this institutional design is well-matched to the problem of long-cycle midstream capacity: it explicitly recognizes that feasibility is constrained not only by capital availability but also by permitting clocks, project sequencing, and the practical time required to reach serial-status qualification in downstream supply relationships [8].

3.4.3. Case Study 3: China—Item-Specific Export Licensing at Chokepoints (Ga/Ge and Graphite)

China’s approach differs in that it combines extensive installed midstream capacity with a licensing-centered instrument at sensitive nodes. In July 2023, Chinese authorities communicated that items related to gallium and germanium would be subject to export controls implemented via licensing, emphasizing that the policy is framed in national-security and non-proliferation terms and that exporters apply for permits under specified procedures [12,98]. In October 2023, China also announced export controls on certain graphite materials and related products, again framed as a permit regime rather than a blanket ban [13,99]. Subsequent MOFCOM remarks in December 2023 indicated that export applications were being received and that compliant applications could be approved following review procedures, reinforcing the characterization of licensing as an administrative channel that conditions trade on documentation and scope compliance [100].

Interpreted through the network-RBV lens, item-specific export licensing is best understood as a powerful “editor” of the compliance layer at precisely those midstream chokepoints where switching is slow because qualification cycles are long and substitutability is limited in the short run. Licensing can therefore influence not only quantities but also planning horizons, inventory strategies, and the perceived risk premium associated with reliance on a concentrated node. The central governance implication is that the economic impact depends heavily on the transparency and predictability of scope definitions, documentation requirements, and review timelines, because those features determine whether cross-border flows can be scheduled as a manageable constraint or must be treated as stochastic disruption risk [12,13,100].

3.4.4. Synthesis

Across the three cases, the cooperation-first logic advanced in this manuscript is most directly supported by instruments that make qualified capacity portable and schedulable: clear criticality taxonomies that coordinate investment priorities, permitting and project-designation pathways that compress time-to-build, and licensing regimes whose published scopes and documentation requirements reduce uncertainty for compliant trade. In practical terms, these cases motivate the paper’s emphasis on standard interoperability and mutual recognition, predictable licensing scopes, and qualification-aware contracting as the fastest levers to expand feasible multi-layer routes through midstream bottlenecks without requiring wholesale duplication of entire supply chains [9,97,99].

4. Discussion

This paper argued that durable advantage in mineral-intensive technologies is created not by isolated assets but by networked resource systems: bundles that span upstream access, midstream know-how, qualification data, logistics and recovery loops, and the standards and permits that bind them. Public instruments—criticality lists, diversification benchmarks, permitting clocks, and item-specific licensing—operate as meta-resources that shape appropriability and imitation at bottlenecks. Reading through this lens, persistent midstream concentration does not inevitably imply fragmentation or decoupling; rather, it makes the design of interoperable rules and cooperative governance the central managerial and policy task. The cooperation-first stance developed here follows directly: structure predictable access and shared standards wherever feasible, and build selective domestic capability only where genuine security or continuity requires it.

4.1. Theoretical Contributions

The first contribution is to relocate RBV’s VRIN locus from the focal firm to a multi-party resource system. We formalize the effective resource endowment, emphasizing that advantage in mineral-intensive sectors is co-produced by owned assets, contracted capacity (offtakes, tolling, joint ventures), and interoperable access via alliances and standards. This move clarifies why the hardest-to-replicate capabilities—separation, refining, metalization, engineered materials, anode-active materials, epitaxy and wafering, and catalyst preparation and recycling—often lie beyond the balance sheet of any single firm yet remain central to performance under shocks.

The second contribution is to endogenize policy into RBV as a set of isolating mechanisms that can either widen or narrow the feasible set for cooperation. Eligibility determinations and diversification benchmarks channel demand and finance toward qualified nodes, permitting clocks compress time-to-imitate for credible entrants without diluting technical rigor, item-specific licensing turns uncertainty into a schedulable compliance task, and mutual recognition of testing and audits reduces switching costs across jurisdictions. Treating these instruments as meta-resources integrates institutional design with capability building and replaces the false dichotomy between “market” and “policy” with a unified account of how rules and routines jointly shape rents.

A third contribution links dynamic capabilities to cooperation architecture. Sensing is richer when standards work and licensing dialogues are transparent; seizing is less risky when qualification steps are explicit and embedded in contracts; transforming is faster when results are portable across regimes and when pilot lines or recycling hubs shorten validation loops. The prediction is straightforward: the return to dynamic capabilities is higher in standard-interoperable, rule-aligned networks than in fragmented ones. Finally, by highlighting bottleneck proximity as a determinant of rent potential, the framework refines RBV for minerals: the closer a capability sits to a qualification-heavy midstream node, the greater the payoff to governance choices that make compliant capacity travel—an observation that also structures an empirical agenda around time-to-qualification, portability of test data, exposure to licensing scopes, and days-of-cover at critical stages.

Our novelty is not the individual components of RBV, dynamic capabilities, or network resilience, but their integration into a single operational claim about the locus of advantage and vulnerability in critical minerals: VRIN attributes often reside in qualification-heavy midstream resource systems spanning firms and jurisdictions, and policy instruments function as meta-resources that reshape what capacity can be reliably accessed across layers (physical, contractual, standards, licensing). Network-of-network resilience typically emphasizes topology and shock propagation; network-RBV explains why certain chokepoints persist (time-to-copy, tacit know-how, compliance/qualification constraints) and how governance alignment expands feasible routes without assuming full replication.

4.2. Policy Recommendations

A cooperation-first strategy follows from the theory without requiring sweeping institutional overhauls. The priority is to make qualified capacity portable. Standards and mutual recognition should focus where qualification friction binds most—magnet grades and rare-earth processing, graphite anode-active materials, wide-bandgap epitaxy and device reliability, PEM catalyst preparation and recycling feed quality, and optical-module reliability for silicon–III–V hybrids [101]. The operative principle is minimal, performance-relevant test suites with clear sampling plans and uncertainty bounds so that results accepted in one jurisdiction are usable in another. Where rules differ, publish the mapping and the delta tests, so suppliers can plan validation once rather than restart from zero.

Finance should be tied to qualification pathways rather than generic capacity targets. Long-dated offtakes and framework agreements can underwrite expansions at midstream nodes if they include explicit acceptance criteria, change-control, and staged ramp gates; the same instruments should preserve multi-sourcing to avoid lock-in. Licensing should be treated as a technical workstream: scope definitions, document packs, and review clocks must be public and stable enough that logistics and joint R&D can be scheduled with confidence. When items are sensitive, define “minimum viable domestic capability” against a quantified continuity window and pair it with mutually recognized stockpiles, avoiding wholesale duplication of entire chains while keeping interoperability with global standards.

Institutional cooperation is most productive where it reduces redundant effort. Shared pilot lines at bottlenecks, supported by jointly governed data rooms with clear IP and confidentiality guardrails, can generate qualification results that travel and shorten learning curves for entrants without relaxing safety or environmental assurance. Public diagnostics should be published on a rolling basis—exposure indices, qualification lead times, project-to-serial conversion rates—so that buyers and suppliers can coordinate expansions and procurement calendars and make diversification bankable. The same logic applies in AI infrastructure: advanced packaging for HBM and interposers, optical modules that combine silicon photonics with III–V lasers [102], wide-bandgap power stages [103], and long-lead facility equipment all benefit from common reliability tests, predictable licensing, and forward scheduling of constrained inputs such as transformer steel and copper windings.

None of this denies the need for screening where defense or critical-infrastructure uses are involved; it channels that need into narrow, transparent guardrails while keeping the wider commercial ecosystem open. The test of success is practical: shorter times to qualification at bottlenecks, a larger share of volume moving under interoperable standards, more capacity additions achieving serial status on schedule, and improved days-of-cover for truly sensitive nodes—achieved without broad fragmentation of trade. That is how countries and firms can compete vigorously on innovation while cooperating on the rules that make the system more predictable, resilient, and ultimately faster to scale.

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

This paper is conceptual and comparative in nature. While it develops a network-RBV framing and uses cross-jurisdictional policy evidence to motivate the argument, it does not estimate causal effects of particular policy instruments on investment, prices, or welfare outcomes. The contribution is therefore best interpreted as theory-building and mechanism clarification, rather than impact evaluation.

A second limitation concerns the construction of the technology–material mapping and bottleneck identification. The tables rely on secondary and official sources and on stylized criteria for labeling midstream constraints. As a result, important micro-level determinants of feasibility—including firm-specific contracts, qualification datasets, and proprietary process parameters—are not directly observed. Relatedly, the policy discussion abstracts from confidential national-security assessments and other restricted information that often shapes country-specific decisions. For this reason, the notion of “minimum viable domestic capability” is advanced as a governance principle (i.e., when it may be rational to maintain a baseline capability under high control and low substitutability), not as a prescriptive recommendation for any single country.

Future research can strengthen and test the proposed mechanisms in several ways. First, comparative case studies focused on qualification-heavy nodes (e.g., magnet grades, graphite anode-active materials, or SiC epitaxy) could directly assess how standard interoperability, licensing scopes, and qualification portability affect switching costs and effective capacity access. Moreover, event-study designs around discrete changes in licensing, permitting, or standard regimes could provide sharper evidence on timing and adaptation channels.

5. Conclusions

This paper advances a cooperation-first account of critical-mineral supply chains grounded in a networked resource-based view. Durable advantage resides in resource systems—bundles that span upstream access, midstream know-how, qualification data, logistics and recovery loops, and the standards and permits that bind them—rather than in isolated assets. Public instruments—criticality lists and diversification benchmarks, permitting clocks and strategic-project pathways, item-specific licensing, and mutual recognition of testing and audits—operate as meta-resources that shape appropriability and imitation precisely at midstream bottlenecks. Read together, these elements explain why broad decoupling is slow and costly, and why interoperable standards, predictable licensing, and qualification-aware contracts are the fastest levers to expand reliably accessible capacity.

Empirically and managerially, the paper maps priority technologies to salient materials and locates the make-or-break stages—separation, refining, metallization, engineered materials, anode-active materials, epitaxy/wafering, and catalyst preparation/recycling—then translates those maps into a governance toolkit: focus standard-setting and mutual recognition where qualification frictions bind; write offtakes and framework agreements around explicit acceptance criteria and staged ramps; treat licensing as a technical workstream with published scopes and documentation; size minimum viable domestic capability narrowly for genuinely sensitive use-cases; and use shared pilot lines and data rooms to make test results travel without diluting safety or environmental assurance. The same logic carries into AI infrastructure, where advanced packaging, optical modules, wide-bandgap power stages, and long-lead facility equipment amplify the value of standard reciprocity, predictable licensing, and forward scheduling.

The stance is pragmatic. Each jurisdiction can protect bona fide security interests while enlarging the global set of qualified, auditable capacity. Success is practical and measurable: shorter time-to-qualification at bottlenecks, a larger share of volume moving under interoperable standards, more capacity additions reaching serial status on schedule, and improved continuity at truly sensitive nodes—achieved without broad fragmentation of trade. The framework’s boundary conditions are clear: it applies most strongly where midstream steps are concentrated and qualification-heavy; in commodity-like nodes the network premium shrinks, and in tightly controlled defense applications cooperation space narrows. These limits point to a concrete research path: comparative case studies at specific bottlenecks, causal evaluation of standard reciprocity and licensing clarity on time-to-qualification and investment timing, and network models that estimate the marginal value of expanding the effective resource endowment through specific instruments and contracts.

The core message is straightforward: compete hard on innovation, and cooperate on the rules that let legitimate capacity scale and travel. With portable standards, predictable licenses, and contracts that underwrite expansions without lock-in, the result is more qualified supply, faster—precisely where it is most needed to accelerate electrification, strengthen advanced manufacturing, and power AI infrastructure—while preserving room for targeted domestic capability where continuity genuinely requires it.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.K. and A.A.; methodology, Z.K.; formal analysis, A.A.; investigation, I.J.; resources, A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.K.; writing—review and editing, I.J.; visualization, I.J.; supervision, Z.K.; project administration, A.A.; funding acquisition, Z.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was carried out with the financial support of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan within the framework of grant funding for young scientists on research and (or) scientific-technical projects for 2025–2027 (Project IRN AP27508139 “A data-centric approach to enhancing the resilience of semiconductor and strategically important mineral supply chains”).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study, data sharing is not applicable.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this work, the authors used GrammarlyGO Version 9.95.0, an AI writing assistant, in order to improve the flow, style, and grammar of the manuscript. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, X.; Sabo, R.; Rosa, L.; Niazi, H.; Kyle, P.; Byun, J.S.; Wang, Y.; Yan, X.; Gu, B.; Davidson, E.A. Nitrogen management during decarbonization. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Mac Kinnon, M.; Carlos-Carlos, A.; Davis, S.J.; Samuelsen, S. Decarbonization will lead to more equitable air quality in California. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inceoglu, I.; Vanacker, T.; Vismara, S. Digitalization and resource mobilization. Br. J. Manag. 2024, 35, 576–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eerola, T.; Eilu, P.; Hanski, J.; Horn, S.; Judl, J.; Karhu, M.; Kivikytö-Reponen, P.; Lintinen, P.; Långbacka, B. Digitalization and natural resources. Geol. Surv. Finland Open File Res. Rep. 2021, 50, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dou, S.; Xu, D.; Zhu, Y.; Keenan, R. Critical mineral sustainable supply: Challenges and governance. Futures 2023, 146, 103101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhamra, R.; Small, A.; Hicks, C.; Pilch, O. Impact pathways: Geopolitics, risk and ethics in critical minerals supply chains. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2025, 45, 985–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2025. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-critical-minerals-outlook-2025 (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- European Commission. Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA)—Internal Market & SMEs. 2024. Available online: https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/sectors/raw-materials/areas-specific-interest/critical-raw-materials/critical-raw-materials-act_en (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- U.S. Department of Energy. 2023 Critical Materials Assessment. 2023. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/eere/ammto/articles/2023-doe-critical-materials-assessment (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- U.S. Department of Energy. What Are Critical Materials and Critical Minerals? 2023. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/cmm/what-are-critical-materials-and-critical-minerals (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Wesselkaemper, J.; Newkirk, A.C.; Hendrickson, T.P.; Helal, N.; Rao, P.; Smith, S.J.; Haddad, A.Z. Enhancing supply resilience for critical materials: Case study of gallium supply in the United States. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 222, 108436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Council Information Office of the PRC (SCIO). Press Briefing on Export Controls Related to Gallium and Germanium Items. 2023. Available online: https://english.scio.gov.cn/pressroom/2023-07/07/content_91665949.htm (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- International Energy Agency, Policies Database. Announcement on the Optimisation and Adjustment of Temporary Export Control Measures for Graphite Items. 2023. Available online: https://www.iea.org/policies/17933-announcement-on-the-optimisation-and-adjustment-of-temporary-export-control-measures-for-graphite-items (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Ivanov, D. Supply chain stress testing for tariff shocks and trade conflicts: Methods, models, and reciprocal influence of operations and economics. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2025, 72, 3559–3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Ivanov, D.; Chutani, A.; Xing, X.; Jia, F.J.; Huang, G.Q. New normal, new norms: Towards sustainable and resilient global logistics and supply chain management. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2025, 201, 104276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Tian, K.; Wu, T.; Yang, C. The lose-lose consequence: Assessing US-China trade decoupling through the lens of global value chains. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2021, 17, 429–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajgelbaum, P.D.; Khandelwal, A.K. The economic impacts of the US–China trade war. Annu. Rev. Econ. 2022, 14, 205–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajgelbaum, P.; Goldberg, P.; Kennedy, P.; Khandelwal, A.; Taglioni, D. The US-China trade war and global reallocations. Am. Econ. Rev. Insights 2024, 6, 295–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.; Ma, B.M.; Chen, Z. Developments in the processing and properties of NdFeb-type permanent magnets. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2002, 248, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Commerce. Publication of a Report on the Effect of Imports of Neodymium-Iron-Boron (NdFeB) Permanent Magnets on the National Security. Federal Register. 2023. Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/02/14/2023-03078/publication-of-a-report-on-the-effect-of-imports-of-neodymium-iron-boron-ndfeb-permanent-magnets-on (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Anderson, J.E.; Yotov, Y.V. Tariff Reciprocity; NBER Working Paper 34052; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shy, O. Do Firms Benefit From Reciprocal Tariffs? SSRN Working Paper. 2025. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5207902 (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Huang, J.; Tan, G.; Teh, T.H.; Zhou, J. Network Interoperability in Multi-Sided Markets; Working Paper 24-03; NET Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gallini, N.T.; Winter, R.A. Licensing in the Theory of Innovation. RAND J. Econ. 1985, 16, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallini, N.T. Deterrence by Market Sharing: A Strategic Incentive for Licensing. Am. Econ. Rev. 1984, 74, 931–935. [Google Scholar]

- Heath, J.B. The New National Security Challenge to the Economic Order. Yale Law J. 2019, 129, 1020. [Google Scholar]

- Kooi, O. Power and Resilience: An Economic Approach to National Security Policy; Working Paper; Quantitative Model on Resilience and National Security Externalities; University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernerfelt, B. A Resource-Based View of the Firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1984, 5, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peteraf, M.A. The Cornerstones of Competitive Advantage: A Resource-Based View. Strateg. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. The Resource-Based View of the Firm: Ten Years After 1991. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockett, A.; Thompson, S. The Resource-Based View and Economics. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 723–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Martin, J.A. Dynamic Capabilities: What Are They? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 1105–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.; Singh, R.K.; Mishra, R.; Subramanian, N. Developing climate neutrality among supply chain members in metal and mining industry: Natural resource-based view perspective. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2024, 35, 804–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, B.; Ganga, G.M.D.; Godinho Filho, M.; De Santa-Eulalia, L.A.; Thürer, M.; Queiroz, M.M.; Moraes, K.K. Timing and interdependencies in blockchain capabilities development for supply chain management: A resource-based view perspective. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2025, 125, 1645–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, D.; Dolgui, A. Viability of intertwined supply networks: Extending the supply chain resilience angles towards survivability. A position paper motivated by COVID-19 outbreak. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 2904–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolgui, A.; Gusikhin, O.; Ivanov, D.; Li, X.; Stecke, K. A Network-of-Networks Adaptation for Cross-Industry Manufacturing Repurposing. IISE Trans. 2024, 56, 666–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, S. Arms Race or Innovation Race? Geopolitical AI Development. Geopolitics 2025, 30, 1907–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.A.; Pereira, L.M.; Santos, F.C.; Lenaerts, T. To Regulate or Not: A Social Dynamics Analysis of the Race for AI Supremacy. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.12393. [Google Scholar]

- Han, T.A.; Pereira, L.M.; Santos, F.C.; Lenaerts, T. Mediating Artificial Intelligence Development through Negative and Positive Incentives. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.00403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Energy Technology Laboratory (NETL). What Are Critical Minerals & Materials? 2024. Available online: https://www.netl.doe.gov/resource-sustainability/critical-minerals-and-materials/what-are-critical-minerals-materials (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Intereconomics. The EU’s Quest for Strategic Raw Materials: What Role for Mining and Recycling? 2023. Available online: https://www.intereconomics.eu/contents/year/2023/number/2/article/the-eu-s-quest-for-strategic-raw-materials-what-role-for-mining-and-recycling.html (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- The Guardian. China’s Rare Earths and US Arms Firms: Supply Chain Pressures. 2025. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/apr/16/china-trade-war-us-arms-firms-rare-earths-supply (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Wikipedia Contributors. Rare Earth Industry in China. 2025. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rare_earth_industry_in_China (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- U.S. Geological Survey, Minerals Yearbook 2021. Platinum-Group Metals. Technical Report. 2023. Available online: https://pubs.usgs.gov/myb/vol1/2021/myb1-2021-platinum-group.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- U.S. Army War College Strategic Studies Institute. China in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: A New Dynamic in Critical Mineral Supply. 2024. Available online: https://ssi.armywarcollege.edu/SSI-Media/Recent-Publications/Article/3938204/china-in-the-democratic-republic-of-the-congo-a-new-dynamic-in-critical-mineral/ (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Chemistry World. Congo’s Cobalt Conundrum. 2021. Available online: https://www.chemistryworld.com/news/congos-cobalt-conundrum/4021696.article (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Center for Strategic and International Studies. The Consequences of China’s New Rare Earths Export Restrictions. 2023. Available online: https://www.csis.org/analysis/consequences-chinas-new-rare-earths-export-restrictions (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Center for Strategic and International Studies. China Imposes Its Most Stringent Critical Minerals Export Restrictions Yet. 2023. Available online: https://www.csis.org/analysis/china-imposes-its-most-stringent-critical-minerals-export-restrictions-yet-amidst (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, S.Q.; D’Ariano, A.; Chung, S.H.; Masoud, M.; Li, X. A bi-level programming methodology for decentralized mining supply chain network design. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 250, 123904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shammari, H.; Farhad, S. Heavy liquids for rapid separation of cathode and anode active materials from recycled lithium-ion batteries. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 174, 105749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Neyts, E.C.; Cao, X.; Zhang, X.; Jang, B.W.L.; Liu, C.J. Catalyst Preparation with Plasmas: How Does It Work? ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 2093–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudrenko, I. Adoption of Blockchain in Critical Minerals Supply Chain Risk Management. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Supply Chain Manag. 2024, 17, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Liu, J.C.; Wang, W.W.; Zhou, L.L.; Ma, C.; Guan, X.; Wang, F.R.; Li, J.; Jia, C.; Yan, C. Catalytic properties of trivalent rare-earth oxides with intrinsic surface oxygen vacancy. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.Y.; Sriram, B.; Wang, S.F.; Kogularasu, S.; Chang-Chien, G.P. A comprehensive review on emerging role of rare earth oxides in electrochemical biosensors. Microchem. J. 2023, 193, 109140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilko, J.; Karandassov, B.; Myller, E. Logistic infrastructure and its effects on economic development. China-USA Bus. Rev. 2011, 10, 1152–1167. [Google Scholar]

- Jaafar, M.; Abdul-Aziz, A.R. Resource-based view and critical success factors: A study on small and medium sized contracting enterprises (SMCEs) in Malaysia. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2005, 5, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, B.T.T.; Nguyen, P.V. Driving business performance through intellectual capital, absorptive capacity, and innovation: The mediating influence of environmental compliance and innovation. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2024, 29, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bester, M.H.; Russell, T.; van Heerden, J.; Carey, R. Reconciliation of the mining value chain—Mine to design as a critical enabler for optimal and safe extraction of the mineral reserve. J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 2016, 116, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]