Abstract

This study investigates how first responder departments in Virginia’s 8th congressional district incorporate AI to enhance resilience within their teams and the communities they serve. Drawing on interviews with key personnel, the study employs an inductive thematic analysis to trace how AI is perceived to influence emergency communication, situational awareness, decision-making, and disaster management. Findings reveal an interplay between AI tools and human-centered resilience, with four key themes emerging: community engagement, training, team cohesion, and mental health. These themes underscore that AI is a technical asset that can support emotional well-being, institutional trust, and enhance operational readiness. The study contributes to ongoing debates on AI’s role in disaster management by underlining the human dimensions of technology alongside its implications for community resilience.

1. Introduction

As emergencies become more frequent and complex, artificial intelligence (AI) is starting to play a larger role in disaster management systems. While often discussed in terms of automation, AI is increasingly used in ways that involve human judgment, social coordination, and effective communication. Beyond its technical scope, AI mediates interpersonal coordination, supports responder well-being, and reconfigures communicative practices among first responders and civilians. These transformations signal a broader shift in how resilience is implemented as a socio-technical process shaped through ongoing interactions between humans and intelligent systems.

A central challenge in contemporary disaster risk management is that existing AI deployments overwhelmingly emphasize infrastructure, prediction, and operational efficiency. Prior research highlights advancements in awareness, drone and sensor networks, predictive maintenance, and real-time monitoring [1,2,3,4]. While these developments expand logistical capacity, they often neglect the human and institutional dimensions that make disaster risk management sustainable, namely, trust-building, equitable communication, and the long-term strengthening of relationships between responders and communities. This gap risks reinforcing technically sophisticated yet socially disconnected approaches that erode the foundations of long-term resilience.

This study addresses these challenges by examining the human-facing functions of AI integration within the social fabric of emergency response. Focusing on disaster management personnel in Virginia’s 8th congressional district, this paper examines how AI technologies are perceived to strengthen resilience across internal and external dimensions between first responders and their community. In this framework, internal resilience refers to the ability of first responders to sustain and strengthen their core operations and organizational practices, ensuring that internal systems remain adaptable and sustainable. External resilience, by contrast, reflects the capacity of responders and the communities they serve to maintain connectedness and mutual trust through effective communication, shared understanding, and collaborative knowledge-building during emergencies. Using the four-loop model of resilience to develop a systemic approach to AI adaptation, this research foregrounds the human–AI interface and advances sustainable disaster risk management. In turn, it identifies resilient practices that improve immediate operational outcomes while strengthening social and communicative foundations necessary for long-term, community-centered resilience.

2. AI-Driven Resilience in Disaster Management

Artificial intelligence in emergency management has evolved to deliver adaptive, data-driven, and communicatively responsive infrastructures. Leveraging machine learning (ML), predictive modeling, and natural language processing (NLP), AI technologies are reshaping crisis communication and reconfiguring emergency response coordination in real-time [5]. As AI capabilities become embedded within public service systems, the term remains fluid, often shaped by public perception and rapidly evolving technological infrastructures. For this study, AI is understood as a branch of computer science concerned with developing machines capable of performing tasks that require human intelligence, such as learning, reasoning, perception, language processing, and problem-solving [6,7].

A core component of AI-driven resilience in disaster management lies in emergency communications, where AI-powered NLP models are currently used to analyze fragmented or emotionally charged messages from emergency calls and texts to extract vital information, such as incident type, location, and urgency. Crisis communication is rarely monolingual, and language barriers have long slowed response times, increased misunderstanding, and disproportionately harmed marginalized communities. Recent work demonstrates that integrating multilingual automatic speech recognition, machine translation, and speech-to-speech synthesis can enable responders to receive, translate, and retransmit critical information in near real-time across languages [8]. Such systems not only accelerate dispatch decisions but also ensure that non-English speakers can convey the urgency, affect, and nuance of their situations without relying on human intermediaries [9]. These models also analyze historical and real-time data to detect patterns, such as natural disasters, floods, or tornadoes. As environmental events evolve, predictive AI models support preventative decision-making, such as determining efficient evacuation routes and prioritizing resource distribution based on foreseen patterns of need [10].

2.1. Advancements and Methodologies

Advanced ML and deep learning (DL) approaches analyze information from satellite imagery, sensor networks, meteorological, and geological data to forecast hazards, estimate damage, and map risk, providing early detection of wildfires, storms, and floods. By leveraging real-time monitoring from data analytics devices and integrating predictive operations into emergency operation centers, these tools support scenario planning, optimize evacuation routing, and pre-position critical resources, and enhance rapid decision-making under disaster conditions, enabling citizen-centric crisis management [11,12]. In particular, coupling predictive models with simulation-based decision support and digital-twin representations enables real-time matching of observed damage to precomputed scenarios, offering immediate guidance while updated observations are assimilated and higher-fidelity re-runs are performed as needed [10]. Such DL models enhance early-warning systems and real-time damage assessment, with the World Economic Forum and McKinsey & Company noting that AI’s value lies in accelerating building damage evaluations and enhancing target-setting for aid relief [11,13]. Beyond single-model speedups, the operational value comes from embedding analytic outputs into workflows, making them actionable for resource allocation and evacuation decisions, rather than relying solely on standalone model accuracy [14].

AI can also ingest social media posts, images, and citizen-generated content to detect emergent crises and map community needs in real-time. AI-enhanced crowdsourcing is one such means that illustrates how ML algorithms can process massive streams of social media data to coordinate community-grounded emergency responses, albeit with issues of data accuracy and algorithmic transparency [15]. Recognizing that AI systems are embedded in socio-technical contexts, recent work emphasizes the need for trust-aware AI in disaster risk management, highlighting the importance of interpretability, bias mitigation, and the institutional embedding of AI tools to better support human oversight [11,16,17].

Alongside these capabilities, recent studies have examined the growing role of AI in mental-health support during and after disasters, where large language models, sentiment-analysis systems, and conversational agents are used to detect psychological distress in social-media streams, provide low-threshold psychosocial support, and assist responders in identifying populations at risk of anxiety, depression, or trauma [18]. Even so, scholars argue that AI-driven mental-health chatbots must be evaluated not only for predictive utility but also for safety, privacy, fairness, and overall trustworthiness, demonstrating accurate detection of emotional cues, transparency about model limitations, reliability under crisis conditions, and ongoing monitoring to prevent biased or clinically inappropriate responses [19]. Findings from recent meta-analytic reviews emphasize that although communication-competent CAs can foster positive user evaluations, the effects on actual usage and health outcomes remain inconsistent, underscoring the need for rigorous evaluation frameworks and safeguards when deploying AI for mental health support in high-stakes disaster environments [20].

Despite the critical advancements, existing AI deployments overwhelmingly prioritize infrastructure, prediction, and operational efficiency. The literature centers on what AI can detect, classify, or optimize, but devotes considerably less attention to how AI shapes the human and institutional conditions of resilience, including trust, communication, and the quality of relationships between responders and communities. Crowdsourcing and social-media analytics capture community signals, yet they do not directly cultivate institutional trust or long-term relational capacity. Ethical and explainable AI frameworks emphasize interpretability but rarely consider how AI can enhance institutional legitimacy or facilitate equitable communication for culturally diverse populations. Many AI initiatives remain technologically sophisticated but socially under-integrated, risking solutions that are effective in narrow technical terms but disconnected from the communities they aim to protect.

2.2. AI and Social Resilience

Increasingly, AI plays a transformative role in strengthening “resilience” within disaster management and public safety systems. Resilience is understood here as a relational and socio-institutional capacity through which individuals, networks, and coupled social–ecological systems learn, adapt, reorganize, and, when necessary, transform in response to shocks and prolonged stresses. This approach underscores that resilience entails more than the restoration of prior conditions; it is a forward-looking and generative process that enables systems to reorganize in response to disruption. Siambabala Manyena’s ‘bounce forward’ concept elaborates this point by conceptualizing resilience as continuity within transformed institutional and social environments [21], while Carl Folke’s synthesis of resilience thinking further clarifies how persistence, adaptability, and transformability operate as interdependent qualities that guide public safety institutions in assessing risk, designing interventions, and cultivating social learning across scales [22]. These dimensions are therefore central to how emergency systems position AI not simply as a technical instrument but as a mediator of the communication infrastructures through which resilience is produced.

Embedding AI in disaster and emergency contexts, particularly in multilingual, high-pressure environments, requires treating AI as a partner in a joint human–autonomy system that augments situational awareness, supports dynamic decision-making, and enables adaptive coordination under uncertainty [23]. Achieving such human–AI collaborative resilience depends on task allocation between human and AI agents, transparent decision support, and the integration of AI capabilities with human expertise and institutional practices within a tightly coupled socio-technical architecture, enhancing not only response speed but also organizational learning and institutional memory [24]. Ethical safeguards are essential, extending beyond algorithmic fairness to include human-in-the-loop review, culturally sensitive language processing, error-reporting mechanisms, and equitable access, while active oversight, continuous auditing, and accessible documentation ensure accountability and prevent inequities [25]. Public trust in AI-augmented emergency systems hinges on perceptions of competence, integrity, and benevolence, reinforced when agencies transparently disclose how AI categorizes risk, allocates resources, and makes decisions, and when mechanisms for oversight or appeals are in place [24,26]. In this way, AI functions not merely as a technical tool but as a mediator of communication and institutional relationships that underpin socially legitimate, ethically responsible, and resilient emergency operations [24].

Within this broader architecture, blockchain technologies complement AI by introducing decentralization, immutability, and enhanced transparency, giving safety and emergency actors access to consistent, tamper-resistant risk information and effectively resolving information asymmetry through trustworthy real-time data flows [27]. By enabling transparent data sharing, more accurate sanctions, and faster decision-making among interdependent actors, blockchain reshapes behavioral dynamics, allowing participants to “choose positive strategies at a faster pace,” including compliance, refusal of misconduct, and stricter oversight [27]. These insights reinforce that AI integration alone cannot cultivate institutional resilience; rather, resilience emerges when predictive and communicative AI tools are embedded within trustworthy infrastructures that improve oversight, reduce opportunities for error or manipulation, and strengthen public legitimacy.

Resilience, therefore, synthesizes several interlocking elements. First, agency and adaptive capacity refer to the human and collective abilities to interpret threats, improvise responses, and institutionalize lessons so that provisional actions evolve into routinized practices [28]. Adaptability captures the capacity of actors to influence resilience by modifying institutional arrangements in response to changing internal dynamics, whereas transformability denotes the ability to shift systems onto alternative pathways when existing structures become untenable [22]. Second, institutional form and memory shape how adaptive practices scale and persist [28]. Social-ecological memory, redundancy, cross-scale linkages, and feedback loops provide communities with options for reorganization and renewal [29,30]. Third, social capital and relational trust shape how resources, information, and mutual aid circulate, as bridging ties connect dispersed networks and inhibit the emergence of exclusive, localized resilience that reinforces marginalization [22,28].

Accordingly, frameworks that embed AI within responder–community ecosystems must prioritize issues of power, community recognition, and institutional legitimacy and trust, rather than relying solely on efficiency metrics. AI enhances resilience only to the extent that it aligns with local agency and knowledge, supports the bridging of social capital, and operates within accountable, polycentric governance arrangements that institutionalize social learning and ethical oversight [31,32]. Karina Korostelina’s work further deepens this understanding through the Four Loop model, which conceptualizes resilience as an ongoing community process shaped by interconnected dynamics [33]. At its core are resilience practices that enable recovery, adaptation, and transformation during periods of strain. These practices influence how conflict is perceived and experienced, recalibrating communal interpretations and responses. Identity and power relations guide which practices emerge, while newly formed practices reconfigure intergroup dynamics. External resources flow into community systems and are, in turn, reshaped by community-driven practices. Community capacities evolve through this continual interaction, reinforcing well-being and strengthening the foundation for collective stability. Within such a framework, AI functions as a mediating force that conditions communicative pathways, institutional choices, and resource flows, thereby shaping the very processes through which social resilience is enacted.

Seen through these analytic lenses, artificial intelligence should be conceptualized not as a narrow technical fix, but as a mediator of communicative, informational, and institutional architectures by which resilience is produced. As such, AI is beginning to influence resilience in two key ways: by supporting more timely and fair delivery of services, and by helping to strengthen the trust between responders, agencies, and the communities they serve. Predictive analytics, for example, can be used to map risk and target culturally competent interventions, ensuring inclusion and responsiveness in highly diverse communities [4,34,35]. On the relational side, algorithmic systems shape transparency, accountability, trust, strengthen legitimacy, and bridge ties and local agency. When AI augments social learning, transforming improvisation into institutional memory, enabling timely feedback loops, and revealing cross-scale redundancies, it contributes directly to the forward-looking resilience process [22,29,36].

By foregrounding these relational and institutional dimensions, the study makes two contributions: First. It shifts attention beyond purely infrastructural or predictive AI deployments to ask how AI can mediate the communicative and social architectures through which resilience is enacted. Second, it proposes a framework for embedding AI within responder-community ecosystems that emphasizes mutual recognition, collaborative accountability, and institutional legitimacy, thereby aligning technical capacity with social resilience.

3. Materials and Methods

This research draws on 17 semi-structured qualitative interviews with departmental leadership and frontline personnel from emergency management departments within Virginia’s 8th congressional district, including Arlington County, Fairfax County, and Fairfax City. This jurisdiction was chosen due to its early and ongoing integration of AI into disaster and emergency management workflows, including the incorporation of an AI-powered natural language chatbot for operational support.

Participants were recruited to reflect a cross-section of the disaster management ecosystem, spanning multiple agencies and operational expertise. Department heads were initially contacted through email outreach to explain the purpose of the study and recruit volunteers. Those who expressed interest were invited to participate, and they were also encouraged to share the invitation with colleagues and first responders who might be relevant to the study. The sample included one representative from the City of Fairfax Mayor’s office, one individual from the Arlington Fire Department, two individuals from the Fairfax Department of Public Safety and Communications of the 911 Dispatch Operations Bureau, two members from Fairfax Public Health Emergency Management and Division of Emergency Preparedness and Response, three representatives from the Fairfax Police Department, three individuals from Fairfax Emergency Management and Security, five participants from the Fairfax Fire Department. All interviews were conducted via Zoom™ and lasted approximately one hour.

The interviews were structured around a set of guiding questions designed to understand participants’ roles in emergency response and communications, the procedures implemented within their organizations, and their perspectives on integrating AI technologies into emergency response systems. Key topics included perceived strengths and weaknesses of current procedures, the potential benefits and challenges of AI integration, and how AI could be incorporated into Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) and Standard Operating Guidelines (SOGs). This approach ensured a consistent set of themes across interviews while allowing for a detailed exploration of participants’ experiences and perspectives on AI in emergency management. The study was conducted in compliance with the Institutional Review Board guidelines to ensure the confidentiality of all participants. No personal identifiers, including names, will be disclosed to protect participant anonymity. All transcriptions, data, results, and coding were compiled into an internal report and securely stored on a database drive by the interview management team.

Interview responses were transcribed and analyzed using a multi-stage inductive approach grounded in thematic analysis, which facilitated the bracketing and coding processes of the textual data. Thematic analysis, also known as grounded theory, is a research practice that requires the systematic comparison of themes and emerging data points through the researcher’s heavy involvement with the collected data, involving processes of coding, theme building, and term definition [37,38,39]. This process of analysis involves building, identifying, and describing patterns that reveal both implicit and explicit ideas within the data, which form the basis for the research results [40,41]. As described by Uwe Flick, the grounded theory method for data analysis enables theories to be discovered and formulated as work is conducted with the subject, based on relevance to the studied research topic, rather than because they form a representative sample of a general population [39]. As this stage of research involves multiple interviews, which develop data as they are coded to produce themes and patterns, the use of grounded theory allows theoretical assumptions to be reformulated throughout the research process as information is gathered [39].

All data preprocessing involved standard qualitative procedures, including transcription, anonymization, and manual review to ensure accuracy. No computational AI models, machine-learning pipelines, automated classifiers, or natural language processing algorithms were used at any stage of the data analysis process. Instead, thematic coding was conducted entirely by hand, following iterative cycles of open coding, axial coding, and theme consolidation.

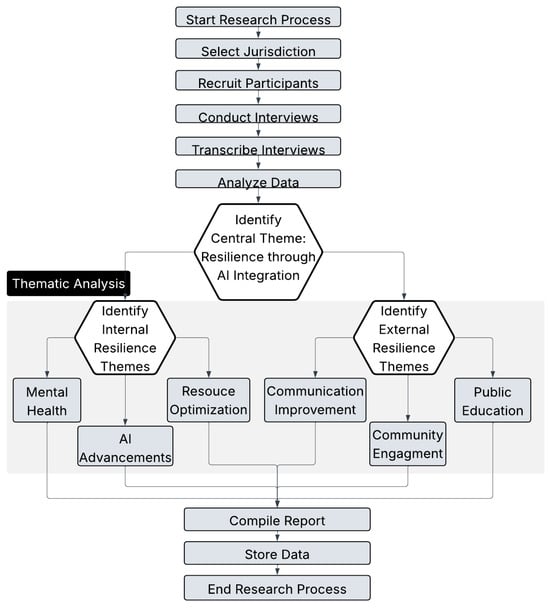

After the interviews were collected, the researcher read through the transcripts several times to familiarize themselves with the data and highlight key components related to communication and AI. The interviews were then re-read and bracketed based on emerging resilience constructs, which arose as recurring patterns across the data. This process led to further bracketing of internal and external aspects of resilience, which helped to clarify how first responders viewed the strengths and weaknesses of resilience within the context of AI integration. Once bracketing was complete, the researcher began the coding process, identifying themes and patterns related to the use of AI and resilience. These codes were developed to represent the most prominent themes, which were then applied to the data to identify recurring patterns, compare code frequencies, and explore relationships between codes. Intercoder reliability and peer debriefing were established by conducting a secondary round of coding to compare the initial coding and presenting it to the research group, ensuring that no new members were added after multiple iterations, and ensuring consistency between the analyzed data (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Methodological Framework.

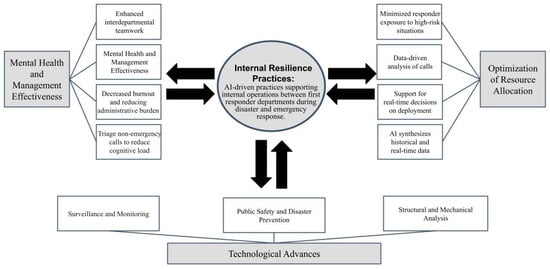

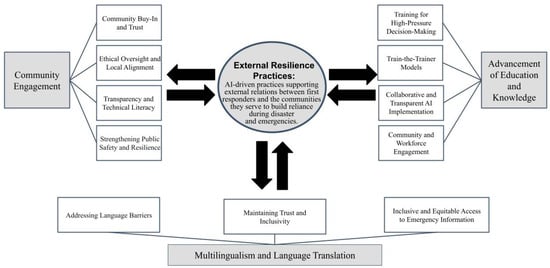

The identification and interpretation of resilience-related themes were guided by Karina Korostelina’s Four Loops model of resilience, which served as the conceptual foundation for understanding how AI-supported practices influence recovery, adaptation, transformation, and community capacities [33]. This method identified recurring patterns across participant narratives, leading to the emergence of a central theme: resilience through AI integration. Additional thematic coding identified two closely connected themes. The first, internal resilience, includes workplace cohesion, mental health, and the ability of institutions to adapt. The second, external resilience, involves building public trust, improving communication, and enhancing coordination among emergency management agencies, as depicted in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Internal Resilience through AI Implementation in Disaster Management.

Figure 3.

External Resilience through AI Implementation in Disaster Management.

4. Results

The analysis revealed two interrelated dimensions of resiliency: internal and external. Internal resiliency encompasses practices that integrate AI into first responder communication, disaster management operations, and interdepartmental coordination. These practices focus on three key areas: (a) technological advancement, (b) mental health and management effectiveness, and (c) optimization of resource allocation. External resilience encompasses strategies that strengthen the relationships between first responders and the communities they serve, facilitating the integration of AI into disaster management. These practices focus on three key areas: (a) building community engagement, (b) advancement in education and knowledge, and (c) the furtherance of multilingualism and language translation. Together, these dual dimensions provide a twofold approach to resilience, where the intersection between AI systems with internal capacities and broader community-oriented practices establishes a social foundation for sustainable disaster management.

4.1. Internal Resilience Practices

Findings indicate that first responders perceive AI as a mechanism that supports communication across departments. Respondents described AI systems as reinforcing the institutional structures, procedural, communicative, and cognitive, that enable departments to function cohesively under the pressure of disaster response. Three themes emerged: Technological advancements, mental health resilience, and the allocation of human and disaster relief resources in ways that make the institution itself more adaptable and resilient.

4.1.1. AI-Enabled Technologies

AI integration in first responder operations includes the use of surveillance, facial recognition, contraband and fraud detection, wildfire prediction, and collision prevention. The Fairfax Police Department has deployed flock cameras, interconnected surveillance units designed to monitor large areas, that autonomously track movement patterns, detect anomalies, and alert responders to suspicious activity, enabling police to make better informed operational decisions. Similarly, the Fairfax Fire Department utilizes thermal imaging technology to detect fire conditions, locate individuals in dense smoke, darkness, or debris, and assess heat signatures to track survivors, fire spread, hazardous materials, structural integrity, temperature, and gas presence, enabling first responders to navigate safely, make real-time decisions, and improve search and rescue efficiency. Officials highlighted that these technologies enhance operational efficiency and play a crucial role in protecting the community. One interviewee explained that AI-driven tools improve first responders’ situational awareness by analyzing mechanical and thermal responses within buildings:

Another respondent highlighted the role of AI in supporting interdepartmental decision-making and situational assessment: “Maybe something else is going on, and a building engineer could come in and intervene early before there truly is a problem. And I think the other thing that we could incorporate is building occupant situational awareness.”[AI helps] look at mechanical and thermal responses within buildings to improve our, our first responders’ situational awareness so that they can have a better understanding of where in the building is the greatest stress, strain, deformation, vibration—all of those things—to make good, informed decisions that may prevent occupants from being caught in a collapse.

Arlington County first responders anticipate AI-driven technologies’ continued growth within their work, with one interviewee highlighting their potential to enhance efficiency and public safety:

The goal is to develop a streamlined information repository for timely report compilation and versatile database applications, representing a collective aspiration for improved efficiency and better data utilization in operational processes. This enables first responders to anticipate operational needs and implement coordinated, interdepartmental practices that function collaboratively within disaster management operations.I think anything that makes us more efficient prevents disasters, saves lives, saves property, you know, ensures that the community feels safe. And that’s the other thing, is that communities need to feel safe. Your, your, perspective is your reality. If you feel like you’re not safe, then you’re not safe, because you feel unsafe. And so, I sort of feel like artificial intelligence, we have to continue to pursue the highest and best use of this technology.

4.1.2. Mental Health and Management Effectiveness

A second theme involves how AI transforms mental health support for first responders by easing cognitive load, improving operational efficiency, and boosting workplace safety. By analyzing emergency call data, detecting behavioral patterns, and supporting real-time resource allocation, AI assists dispatch teams in determining when to deploy specialized co-responder units, particularly those that include mental health professionals. Depending on the crisis at hand, mental health professionals aid in high-risk interventions, reducing exposure to unpredictable or violent scenarios. “We don’t believe that mental health clinicians should go to an emergency mental health crisis with zero protection, because people that are irrational and suicidal, may be armed with weapons.” AI is now analyzing calls and assisting in informed decision-making based on call tone, verbal choice, and pattern recognition. Responder safety, necessary external assistance, and community well-being are becoming increasingly prioritized. As a result, this ensures the correct responders are directed to a crisis, thus reducing the burden on first responders by redirecting cases involving mental health crises to appropriate emergency mental health clinicians.

Beyond field-level interventions, respondents discussed how AI integration contributes to internal resilience by automating routine administrative tasks. In Fairfax County, 911 dispatch centers handle between 100 and 200 calls daily, which take emotional, mental, and physical tolls during daily operations. Respondents discussed how AI-powered tools, such as NPLs and chatbots, have been deployed to support triage, reporting, and data management. These integrated systems alleviate operational pressure on dispatchers by automating workflows and minimizing time-intensive documentation processes.

Constant exposure to high-stress environments and an overwhelming volume of calls can lead to burnout, decision fatigue, and a decline in mental well-being. Chatbot systems reduce cognitive overload and emotional fatigue by triaging non-emergency calls and filtering routine inquiries before they reach dispatchers, allowing for more focused and higher-quality interactions. In effect, chatbot integration protects the psychological health of emergency workers while sustaining, and often improving, the quality and efficiency of emergency response systems.

Respondents across emergency departments linked this reduction in bureaucratic strain to marked improvements in psychological well-being, workplace efficiency, and team cohesion. By automating administrative tasks such as data entry, case routing, and reporting, AI reduces unnecessary strain, allowing personnel to focus on complex tasks that require human judgment, empathy, and discretion. These findings suggest that internal resilience goes beyond individual coping; it enhances interdepartmental cohesion and communication, supported by intelligent automation.

4.1.3. Resource Optimization

The third finding depicts how AI systems increasingly enhance resource utilization and human resource management during crisis conditions. By synthesizing large volumes of real-time and historical data, including incident logs, weather conditions, traffic flows, and GIS records, AI enables precision in policy development and human resource allocation. For instance, law enforcement respondents emphasized that routine documentation processes are being reimagined through AI-driven interfaces and body cameras. One participant outlined a future practice in which AI could automatically extract relevant data from audiovisual records, thereby minimizing manual input:

Beyond administrative automation, participants highlighted AI’s ability to facilitate real-time situational analysis and resource optimization under crisis conditions. For instance, AI can integrate real-time wind patterns, temperature changes, and terrain data during a wildfire to recommend optimal evacuation routes and firefighting tactics. Similarly, an emergency management official emphasized AI’s ability to synthesize large datasets in crisis scenarios, such as tornado aftermaths, to optimize the deployment of firefighting and medical response teams. The official noted that AI-driven decision-making could surpass human cognitive capabilities in rapidly assessing and prioritizing critical resource allocation.Everything’s body cameras, or video. And I really do believe that police reporting, there’s gonna be intuitive or AI will just kind of do that… They basically hold the driver’s license of the person up in front of their body camera, and then hold up some notes. It’s kind of like the camera takes all of that in.

Participants also described AI as contributing to broader planning and preparedness efforts. By integrating historical trends, weather data, incident patterns, and geospatial information, AI was viewed as enhancing the organization’s ability to anticipate operational needs and distribute personnel and equipment more effectively: “Artificial intelligence holds the promise of being able to take data from various sources, historic data, current data, data being collected real-time from a variety of different sources, and put it together and be far more specific and predictive in what a potential threat is, where it is, when it is.” These findings suggest that AI systems facilitate the reconfiguration of agency within emergency infrastructures, thereby redefining the relationship between human judgment, technological mediation, and institutional response. In doing so, AI becomes a critical actor in shaping how resilience is pre-emptively constructed—through communicative precision, predictive modeling, and automated coordination.So let’s say a tornado comes through, and then you start getting data about flooding, fires, injuries. That putting data like that into a system that can tell you the best way to deploy your available resources would also be a help instead of just relying on human commanders to say, well, we’ve got these three teams of firefighters and let’s prioritize it and send them these places based on the knowledge we have in the moment… In a way that might be quicker and more efficient than what the human mind can possibly process with the available information they have.

4.2. External Resilience Practices

Findings show that first responders consistently framed community resilience as dependent on how AI is understood, accepted, and used by the public. Across interviews, participants described AI as a communicative and relational resource, one that gains its effectiveness only when embedded in transparent, collaborative, and culturally inclusive practices. Three themes emerged: community trust and legitimacy, education and shared understanding, and linguistic accessibility.

4.2.1. Community Trust

Findings from this study underscore that community involvement is essential to the success of AI-driven initiatives, as resilience depends on a cooperative relationship between those implementing AI and those affected by it. One official emphasized, “There’s fear of AI, right? Like people are afraid of AI. So, like, before we employ it broadly, or really, in a meaningful way, there’s got to be like, buy-in from the community.” Community buy-in reflects a broader recognition that successful integration of AI into public systems does not solely rely on building the right technology, but on earning public trust through open, social processes. AI-driven tools enhance resilience when residents understand their purpose, feel included in decision-making, and trust the institutions deploying them.

Interviews revealed that trust is not generated by AI itself, but rather through processes of engagement that reduce fear, demonstrate accountability, and signal respect for community autonomy. One such means is through information engagement, which involves efforts to explain how AI tools work, what data they rely on, and where their limitations lie. Respondents replied that this is important because if AI is deployed without explanation, “people [are] going to think we’re hiding something or misusing [it]”; thus, transparency and early dialogue function as trust-building mechanisms that preempt suspicion. Another means was through participatory engagement, which provides opportunities for residents to influence decisions, shape implementation, and define acceptable use. This is essential for building shared ownership of AI systems, as it ensures that their technical functions are clearly explained in ways that foster legitimacy. Respondents emphasized that trust unravels when agencies move ahead without bringing residents along, noting that “people are generally suspicious… and they want to know what’s going on in terms of their privacy, the impact of it, and they ask some hard questions.” Building trust requires multiple touchpoints over time, early conversations, pilot stages, ongoing monitoring, and repeated opportunities for residents to revisit concerns as technologies evolve. These findings demonstrate that perceptions of fairness, transparency, and consent directly influence whether AI systems strengthen or undermine community resilience. When communities perceive AI as aligned with their values, they see emergency systems as more trustworthy, responsive, and protective, reinforcing relational resilience between residents and responders.

4.2.2. Education and Shared Understanding

A second theme involved the role of education and training in shaping perceptions of AI as a supportive tool for both responders and the broader community. Respondents described training as essential not only for technical proficiency but for building a shared understanding of how AI supports judgment, decision-making, and public safety. Implemented training strategies aim to equip the community with the skills needed for proficient AI use, fostering engagement and collaboration, and enhancing the community’s interaction with AI. This sentiment is echoed in the emergency management sector, where officials recognize the importance of structured training before full-scale implementation: “We’re going to train somebody who’s going to get primarily trained. And this is usually how we do a lot of our larger trainers: we will train a very small group of people to be the trainers. And then we will send them out to the masses to train everybody else.” This process was seen as critical to embedding new technologies into the institutional culture and extends to include the communication of underlying rationales, expectations, and implications of AI systems.

4.2.3. Multilingualism and Inclusive Communication

A third theme centered on multilingual communication as a critical dimension of community resilience. Respondents described language barriers as a persistent challenge in emergency response, particularly in linguistically diverse jurisdictions such as Fairfax County. Traditional translation resources, such as language lines, were frequently seen as slow, inconsistent, or unable to handle dialectical variation:

Several respondents expressed concerns that these services are not a perfect solution and can hinder response time as they do not account for dialectical variation, informal speech, or urgency, jeopardizing response accuracy. As one dispatcher recounted, there have been times when they had to rely on guesswork because the language line either did not recognize the dialect or took too long to connect with someone who did.

AI-enabled language processing technologies, currently in pilot integration, were widely viewed by respondents as a promising intervention in emergency communications. Specifically, chatbots and AI translators trained on extensive multilingual datasets were cited for their ability to recognize dialectical variations and deliver context-sensitive translations in real-time. As one responder explained: “We have some dispatchers who are bilingual, but we don’t cover all the languages. There’s just no way we could. And there have been times where we do have people who speak Urdu, and, if I don’t know, some people don’t even know it’s a language… this is where AI will be key.” Participants emphasized that accurate translation is not merely a logistical need; it shapes whether residents feel understood, respected, and safe during emergencies. One official underscored the importance of contextual accuracy:

These perceptions demonstrate that AI-enabled linguistic tools contribute to relational resilience by making emergency communication more inclusive, reducing misinterpretation, and ensuring public trust.However, if you have a rare dialect, you know, you can theoretically get anyone on language lines. And sometimes, it would take minutes and minutes. And the person would just say a language, and you’d be like, okay, hold on, and you try to get a language and, and even with Spanish, you know, the interpretation delays, and the some of the challenges they’re not getting, with context or intent behind your question, that’s a great point about language and AI, to accurately translate. Especially if they understand the context and the environment you’re in.

4.3. Limitations

Within the study, respondents acknowledged limitations related to the integration of AI into emergency response, particularly in terms of ethical and security concerns. They expressed discomfort with AI potentially conflicting with human judgment, highlighting the challenge of balancing technological advancements with frontline expertise.

4.3.1. Security Concerns

Participants noted that AI technologies used in disaster management systems are vulnerable to security risks, particularly as they become more interconnected and reliant on data exchange. Such breaches could involve manipulating data, disrupting critical functions, or gaining unauthorized control over communication channels, all of which could severely undermine the effectiveness of first responders. This vulnerability raises significant concerns about the security of sensitive data and the potential for malicious manipulation to compromise operational integrity. Manipulating data sources can introduce false information into AI algorithms, leading to misguided resource allocation, delayed responses, or even the deployment of responders to non-existent incidents, jeopardizing their safety and wasting valuable resources. Participants noted that in certain scenarios, hackers could intentionally falsify data, leading to the misdirection of responders to non-existent or less critical incidents. This not only wastes valuable time and resources but also exposes responders to unnecessary risks, thereby delaying assistance to those who genuinely need it. In addition, altering environmental data, such as temperature or occupancy information during emergencies like fires, poses another layer of risk, misleading responders regarding the severity and location of the incident, which in turn could result in ineffective action and compromised safety. This was also reflected in a growing apprehension not only about data manipulation but also about the misuse of surveillance footage and personal data, further complicating the security landscape of AI in first responder operations.

4.3.2. Ethical Dimensions

Interviews revealed concerns about the potential conflict between AI-generated recommendations and human judgment, adding complexity to decision-making processes. Respondents emphasized the challenge of relying on AI-driven insights versus trusting the expertise and intuition developed through years of frontline experience. As one first responder explained, “We’re just now starting to crawl. What does it mean to have an ethical AI usage policy internally and externally? We are trying to navigate this, but it’s something we have to do. First, the technology available is outpacing our comfort. You know, we’re eager, but we also have reservations.” This statement underscores the broader hesitation expressed by responders: while they acknowledge AI’s potential, they remain cautious about its unregulated impact on their work.

These ethical concerns extend beyond departmental protocols and influence how responders view AI in the context of public safety. Risks associated with generative AI, including deepfakes and other forms of misinformation, heighten the potential for social and civil disorder, escalating tensions, eroding public trust, and undermining the credibility of emergency responders. One respondent further cautioned,

Hereby, the appeal of AI-powered decision-making is tempered by the susceptibility of these systems to errors, spread misinformation, and ultimately undermine public trust in both technology and first responders.My concern is the response and reaction to it [AI], and I think the misunderstanding, my concern is if we move too fast…but if we move too fast, we’ll lose community trust, and we cannot afford to do that. I guess my concern, right off the bat, is AI helps, it doesn’t do the work, you still have to do and check the work.

5. Discussion

The integration of AI into emergency communication systems has significantly enhanced disaster management and resilience, strengthening internal operations and community engagement. Our study reveals that embedding AI within first responder agencies not only streamlines operational processes but also bolsters resilience by fostering trust and cooperation between responders and the communities they serve, particularly during times of crisis.

5.1. Strengthening Community Engagement and Trust

Findings from this study demonstrate that community engagement is not a peripheral consideration but a central mechanism through which AI contributes to sustainable resilience. First responders consistently emphasized that AI’s value depends on how communities interpret its intentions, fairness, and relevance to their lived experiences. Integrating AI into emergency response systems in Virginia’s 8th Congressional District signals a shift in how institutional actors interface with communities, positioning resilience as both a technological capacity and a communicative relationship during crisis management. AI systems do not merely support operational capacity; they shape public perceptions of institutional competence, cultural sensitivity, and procedural legitimacy, key predictors of resilience during high-risk events. In multilingual communities, AI facilitates communicative clarity, a prerequisite for trust and compliance in emergency response. This is particularly salient in communities where law enforcement may have been historically viewed with suspicion or fear, as the ability to establish immediate, culturally competent communication reduces friction and reframes institutional encounters as collaborative rather than coercive.

Beyond translation, participants described AI as strengthening resilience by enhancing culturally responsive outreach and facilitating the equitable distribution of resources. Respondents highlighted post-COVID community preparedness efforts that rely on partnerships with grassroots organizations. These networks became essential during the pandemic, enabling behavior change and vaccine uptake through trusted local actors. AI-supported demographic analysis and hotspot detection enabled agencies to identify underserved neighborhoods more effectively, thereby strengthening the credibility of institutions and ensuring fair access to services. Equally important is how AI supports human decision-making under conditions of information overload. Participants consistently described AI as a decision-support tool that augments, not replaces, professional judgment, enabling responders to process dense information environments with greater speed and clarity. One respondent presented a compelling case for using AI to automate threat detection and response systems, particularly in addressing violent threats. Following the Parkland shooting in 2017, Fairfax County schools experienced a wave of 60 threats within a week, many of which were copycat incidents posted online [42]. The respondent noted that AI could be used as a tool in the future to help optimize the system by quantifying what was a valid threat by identifying patterns and comparing new threats with past events at high speed, concluding that AI could help differentiate between ‘false flags,’ ‘copycats,’ and legitimate threats more efficiently than current methods, as they rely heavily on manual analysis and collaboration with the FBI Behavioral Science Unit. AI extends human situational awareness, increasing accuracy and reducing uncertainty during rapidly escalating events, thereby demonstrating to the public that institutional systems are capable, responsive, and transparent.

Public confidence in emergency services is a core component of social resilience. As noted in one interview with the County Health Department, persistent distrust of government institutions, particularly among historically marginalized groups, makes the relational dimensions of AI-supported communication indispensable to resilience-building. AI assists this process indirectly by freeing human responders from cognitive and bureaucratic load, allowing them to focus on relational engagement. By shifting administrative burdens to automated systems, responders gain the time and emotional bandwidth necessary to engage empathetically, communicate more effectively, and address community concerns with greater nuance.

Still, several first responders expressed unease about how AI is applied in practice. They pointed out that if a system is built on flawed assumptions, it could, for example, prevent law enforcement from being dispatched to a high-risk mental health crisis, potentially putting both responders and community members in danger. Such concerns underscore that resilience is shaped not only by technological accuracy but by the ethical alignment between AI outputs and frontline expertise. First-responder agencies consistently emphasized that meaningful AI integration must therefore be anchored in explicit accountability structures, sustained oversight, and deliberate governance processes. Several respondents stressed that deployment cannot precede the establishment of guidelines, monitoring, and transparency mechanisms, noting that community buy-in and visible oversight are essential to avoiding the perception that agencies are exploiting the technology. This expectation extends internally as well: departments acknowledged that they must first develop shared ethical frameworks and data-governance norms, explaining, “We need to have conversations about the ethical use of all this…We have to make sure we have wise use of the information that we do have. We don’t want to arbitrarily scrape.”. At the same time, many also viewed AI as a potential check on human prejudice, suggesting it could help mitigate our counteract bias in assessment processes, while still recognizing that AI system are built upon data and system that may themselves be bias, underscoring the need for ongoing validation and continuous evaluation to maintain fairness in high-stakes decision support. Human–AI teaming research reinforces this orientation, arguing that effective collaboration depends on calibrated trust, clearly defined functional boundaries, and machine-in-the-loop paradigm that allows humans to monitor, correct, and override algorithmic outputs [43]. These frameworks suggest that AI systems must be embedded within governance structures that support interpretability, sustain human authority, and ensure that accountability flows remain transparent, thereby integrating emerging technologies into existing professional and ethical ecosystems rather than displacing them.

These factors further underscore that AI enhances resilience when integrated into structures that foster transparency and legitimacy. Systems designed to reduce information asymmetry strengthen supervision and incentive effectiveness, as transparent, tamper-resistant data flows create the conditions under which communities view institutional actions as fair and trustworthy [27]. These dynamics matter because AI’s capacity to improve early detection, resource targeting, or decision support is only as effective as the public’s willingness to accept those decisions as legitimate. When communities perceive that information is handled openly and reliably, AI-enabled actions reinforce rather than erode institutional credibility. In this way, trustworthy infrastructures do not merely support AI’s technical functions; they directly enhance the relational foundations of resilience by signaling procedural fairness, reducing suspicion, and strengthening the social contracts upon which emergency response depends.

5.2. Mental Health and Operational Well-Being

A second major finding highlights how first responders perceive AI as a mechanism that strengthens both organizational resilience and workforce well-being, particularly in internal mental health situations and in crisis response. Qualitative data from first responders indicate that integrating AI into response and disaster management infrastructures enhances community interdepartmental resilience by improving operational efficiency and promoting psychological and occupational well-being among first responders. One respondent emphasized that the historic burden of mental health response from under-resourced public health systems, during which some inadequately trained officers were sent to handle behavioral health incidents, contributed to exacerbating workforce stress. Currently, AI-enabled triage systems in use are widely described as reducing emotional strain by improving accuracy in directing incidents to the appropriate response teams, thereby preventing misalignment between crisis needs and personnel expertise. AI-enabled dispatch systems that analyze caller language, tone, situational metadata, and historical incident data to assess urgency and risk were perceived as enhancing both responder safety and public legitimacy by enabling more precise, proportional, and ethically grounded deployment decisions. These systems suggest when to deploy co-responder units comprising both law enforcement and mental health clinicians, a practice that aligns with co-responder models demonstrated to reduce involuntary detentions and psychiatric hospitalizations by over 16% in San Mateo County, with a 17% reduction in mental health-related calls [44]. When AI systems flag high-risk indicators such as weapon references or incoherent speech, they enable safer responses, safeguarding responders and reinforcing legitimacy in community engagement. As an officer pointed out, in jurisdictions that prioritize clinician-led responses, the absence of law enforcement in high-risk scenarios could expose responders to harm. AI’s ability to highlight situational cues in real time was therefore framed as essential in ensuring balanced deployments that respect both community-centered mental health approaches and responder safety. If trained adequately with ethical and contextual sensitivity, AI systems can identify these risks in real-time, ensuring that safety remains a central concern in deployment decisions. The emotional and cognitive demands placed on dispatchers and officers, particularly in high-volume, multilingual jurisdictions like Fairfax, are mitigated by AI tools that automate administrative processes. AI chatbots and natural language processing tools now manage call intake, incident transcription, and records management with increasing sophistication, assuming routine, structured tasks that would otherwise consume limited human resources and enabling overstretched systems to maintain continuity of care without parallel staffing increases, thereby reinforcing the division of labor central to resilience frameworks [45]. By relieving personnel of reparative administrative burdens, AI enables emergency personnel to dedicate their cognitive capacity to high-stakes human interactions that strengthen community trust, such as de-escalation, trauma-informed care, and collaborative decision-making. The empirical findings align closely with the Safety-II framework, which conceptualizes resilient systems not simply as those that avoid failure but as those that maintain successful performance under varying and unpredictable conditions [46]. AI-enabled triage, dispatch analysis, and administrative automation function as capacity amplifiers that support this form of resilience by absorbing routine, predictable cognitive load, allowing first responders to redirect their attention toward the complex, relational, and ethically charged aspects of mental-health crises. In this sense, the observed improvements in decision accuracy, workload reduction, and cross-unit coordination parallel to Erik Hollnagel’s claim that resilient socio-technical systems depend on reallocating tasks so that humans can focus on the adaptive, variable, and high-stakes portions of work [46]. Several respondents perceived AI as contributing to a more sustainable emergency management environment by reducing burnout risks, increasing decision accuracy, and offering predictable structures for processing complex information. This capacity reflects principles identified in resilience research on resource-constrained environments, where effective outcomes hinge on the ability to coordinate across multiple subsystems, such as transportation, communications, environmental conditions, and public safety, and allocate resources in ways that mitigate cascading effects [47]. While concerns continue about over-reliance on automation, first responders affirmed that policing, by nature, must remain grounded in human connection. These findings also reflect foundational principles from socio-technical systems theory, which holds that organizations function most effectively when their social and technical components are jointly optimized rather than treated as independent layers [48]. The respondents’ emphasis on AI as a tool that enhances, rather than replaces, human judgment thereby mirrors Trist and Emery’s argument that technical systems must be integrated in ways that preserve the autonomy, expertise, and meaning of human roles [48]. In this case, AI’s ability to handle transcription, call-taking tasks, and linguistic processing supports first responders by reducing unnecessary strain and enabling personnel to engage directly in de-escalation and trauma-informed care. This joint optimization clarifies why first responders repeatedly emphasized that AI should remain subordinate to human judgment, as the socio-technical balance must be maintained for both operational legitimacy and ethical integrity. AI, in this framing, strengthens resilience not by replacing interpersonal relations but by enabling them. Over time, AI’s role in disaster management supports continuous feedback, measured response, and adaptive learning; core attributes of sustainable, resilient systems.

6. Conclusions

This study of AI integration within Virginia’s 8th congressional district’s disaster emergency response systems provides insight into the evolving relationships between technology, public service, and resilience. While dominant discourses on AI in these fields prioritize technical capabilities such as predictive analytics, automation, and resource optimization, this study foregrounds AI’s human-centered functions, including the cultivation of institutional trust, the mitigation of psychological strain among responders, improved linguistic accessibility, and enhanced communicative coordination across public service networks.

AI has not replaced human roles in emergency response; instead, it strengthens the human aspects of the work. Using AI to ease administrative burdens enables first responders to navigate high-stress, complex situations with greater clarity, supporting their capacity to remain in the field. As interview data showed, real-time language processing aids situational awareness, ethical responsiveness, and institutional legitimacy. These findings align with broader theoretical arguments that resilience is not a static trait, but rather a communicative and adaptive capacity co-produced by technology and public trust, demonstrating that AI’s value in first-response environments lies not in automation alone but in supporting a resilient socio-technical ecology where human expertise, organizational processes, and AI systems are interdependently aligned to sustain ethically grounded and operationally adaptive public safety.

At the community level, AI can strengthen collective preparedness and rebuild confidence in public institutions when designed with cultural sensitivity and implemented through participatory practices. Through equitable language access, targeted public health outreach, or collaborative training models, AI can help close historical gaps in service, particularly among linguistically diverse or underserved populations.

By recentering attention on the human–AI interface, this study presents an alternative vision of intelligent infrastructure that understands resilience not only as a product of technical robustness but as a communicative relationship between institutions and the communities they serve. In doing so, it contributes to ongoing conversations in critical data studies, crisis informatics, and public sector innovation regarding the development of AI systems that support better outcomes and foster more effective relationships between humans and the technologies they rely on.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.R.B. and K.V.K.; Formal analysis, J.R.B.; Data curation, J.R.B.; Methodology, J.R.B. and K.V.K.; Validation, J.R.B.; Visualization, J.R.B. and K.V.K.; Writing—original draft, J.R.B. and K.V.K.; Writing—review and editing, J.R.B. and K.V.K.; Supervision, K.V.K.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by award # 60NANB24D145 from the National Institute of Standards and Technology to the Center of Excellence in Command, Control, Communications, Computing, Cyber, and Intelligence (C51) at George Mason University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in compliance with the Institutional Review Board guidelines to ensure the confidentiality of all participants. Ethical review and approval were not required for this study in accordance with U.S. federal regulation 45 CFR 46.104(d)(2), as interviews were conducted anonymously and participation was voluntary.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| EMS | Emergency Medical Services |

| GIS | Geographic Information Systems |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| SOG | Standard Operating Procedures |

| SOP | Standard Operating Guidelines |

References

- Taherifard, N.; Simsek, M.; Kantarci, B. Bridging connected vehicles with artificial intelligence for smart first responder services. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Global Conference on Signal and Information Processing, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 11–14 November 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Sessions, R. Artificially Intelligent (AI) Drones for First Responders. In Proceedings of the AI and Semantic Technologies for Intelligent Information Systems, AMCIS, Virtual, 10 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dimou, A.; Kogias, D.G.; Trakadas, P.; Perossini, F.; Weller, M.; Balet, O.; Daras, P. Faster: First responder advanced technologies for safe and efficient emergency response. In Technology Development for Security Practitioners; Akhgar, B., Kavallieros, D., Sdongos, E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 447–460. [Google Scholar]

- Rane, N.; Choudhary, S.; Rane, J. Artificial intelligence for enhancing resilience. J. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 5, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, N.; Manikyala, A.; Gade, P.K.; Asadullah, A.B.M.; Kommineni, H.P. Emergency Response Planning: Leveraging Machine Learning for Real-Time Decision-Making. Emergency 2021, 6, 50–62. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, N.J. Artificial Intelligence: A New Synthesis; Morgan Kaufmann Publishers, Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ogie, R.I.; Rho, J.C.; Clarke, R.J. Artificial Intelligence in Disaster Risk Communication: A Systematic Literature Review. In Proceedings of the 2018 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Disaster Management, Sendai, Japan, 4–7 December 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Behravan, M.; Mohammadrezaei, E.; Azab, M.; Gračanin, D. Multilingual standalone trustworthy voice-based social network for disaster situations. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 15th Annual Ubiquitous Computing, Electronics & Mobile Communication Conference (UEMCON), Yorktown Heights, NY, USA, 17–19 October 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 264–270. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Homeland Security: Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning for Emergency Communications. Available online: https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/2024-09/24_0916_st_aimltn.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2024).

- Andrae, S. Artificial Intelligence in Disaster Management: Sustainable Response and Recovery. In Cases on AI-Driven Solutions to Environmental Challenges; Tariq, M., Sergio, R., Eds.; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 73–114. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, K.H.; Wu, Y.Z.; Su, W.R.; Lin, L.Y. A simulation evacuation framework for effective disaster preparedness strategies and response decision making. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2024, 313, 733–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subrahmanyam, S. The Role of AI in Crisis Management and Disaster Response. In Citizen-Centric Artificial Intelligence for Smart Cities; Sharma, A., Mansotra, V., Singh, P., Eds.; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Palmdale, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 227–260. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum. Available online: www.weforum.org/stories/2020/01/natural-disasters-resilience-relief-artificial-intelligence-ai-mckinsey (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Abid, S.; Roosli, R.; Nazir, U.; Kamarudin, N. AI-enhanced crowdsourcing for disaster management: Strengthening community resilience through social media. Int. J. Emerg. Med. 2025, 18, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albahri, A.; Khaleel, Y.; Habeeb, M.; Ismael, R.; Hameed, Q.; Deveci, M.; Homod, R.; Albahri, O.; Alomoodi, A.; Alzubaidi, L. A systematic review of trustworthy artificial intelligence applications in natural disasters. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 118, 109409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffarian, S.; Taghikhah, F.; Maier, H. Explainable artificial intelligence in disaster risk management: Achievements and challenges. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 98, 104123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyena, S.B. Disaster Resilience in Development and Humanitarian Interventions. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Northumbria, Newcastle, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, H.; Shilpa. AI-Driven Healthcare: Transformation and Advancement. In Citizen-Centric Artificial Intelligence for Smart Cities; Sharma, A., Mansotra, V., Singh, P., Eds.; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Palmdale, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 139–164. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, Y.; Xia, W.; Bates, D.W.; Hartstein, G.L.; Kim, H.T.; Li, M.L.; Nelson, B.W.; Stromeyer, C., IV; King, D.; Suh, J.; et al. Standardizing and scaffolding healthcare AI-chatbot evaluation. medRxiv 2024. medRxiv:2024.07.21.24310774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Nan, Y.; Li, Z.; Meng, J. Effectiveness of Communication Competence in AI Conversational Agents for Health: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e76296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyena, S.B.; O’Brien, G.; O’Keefe, P.; Joanne Rose, J. Disaster resilience: A bounce back or bounce forward ability? Local Environ. 2011, 16, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C. Resilience (republished). Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagos, D.H.; Alami, H.E.; Rawat, D.B. AI-driven human-autonomy teaming in tactical operations: Proposed framework, challenges, and future directions. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.09788. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, N.; Zhang, X. When Misunderstanding Meets Artificial Intelligence: The Critical Role of Trust in Human-AI and Human-Human Team Communication and Performance. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1637339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Visave, J. Transparency in AI for emergency management: Building trust and accountability. AI Ethics 2025, 5, 3967–3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benk, M.; Kerstan, S.; von Wangenheim, F.; Ferrario, A. Twenty-four years of empirical research on trust in AI: A bibliometric review of trends, overlooked issues, and future directions. AI Soc. 2025, 40, 2083–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Deng, J.; Li, X.; Ma, J.; He, W.; Wang, C. The mechanism of blockchain technology in safety risk monitoring. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyena, S.B. Disaster resilience: A question of ‘multiple faces’ and ‘multiple spaces’? Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2014, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Carpenter, S.R.; Walker, B.; Scheffer, M.; Chapin, T.; Rockström, J. Resilience Thinking: Integrating Resilience, Adaptability and Transformability. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 20. Available online: https://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol15/iss4/art20 (accessed on 3 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Biggs, R.; Schlüter, M.; Schoon, L. Principles for Building Resilience: Sustaining Ecosystem Services in Social-Ecological Systems; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- McCrea, R.; Walton, A.; Leonard, R. A conceptual framework for investigating community wellbeing and resilience. Rural Soc. 2014, 23, 270–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townshend, I.; Awosoga, O.; Kulig, J.; Fan, H. Social cohesion and resilience across communities that have experienced a disaster. Nat. Hazards 2015, 76, 913–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korostelina, K.V. Neighborhood Resilience and Urban Conflict: The Four Loops Model; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Samaei, S.R. Using Artificial Intelligence to Increase Urban Resilience: A Case Study of Tehran. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Advanced Research in Science, Engineering and Technology, Brussels, Belgium, 18 January 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zohuri, B.; Moghaddam, M.; Mossavar-Rahmani, F. Business resilience system integrated artificial intelligence system. Int. J. Theor. Comput. Phys. 2022, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson, P.; Folke, C.; Hughes, T.P. Navigating the transition to ecosystem-based management of the Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 9489–9494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavin, H. Understanding Research Methods and Statistics in Psychology; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Russel, H.B.; Ryan, G. Text Analysis: Qualitative and Quantitative Methods. In Handbook of Methods in Cultural Anthropology; Russel, H.B., Ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1998; pp. 595–645. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. An Introduction to Qualitative Research, 6th ed.; Sage Publications Limited: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G.; MacQueen, K.; Namey, E. Introduction to Applied Thematic Analysis; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Raji, I.D.; Smart, A.; White, R.N.; Mitchell, M.; Gebru, T.; Hutchinson, B.; Barnes, P. Closing the AI accountability gap: Defining an end-to-end framework for internal algorithmic auditing. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, New York, NY, USA, 27–30 January 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Berretta, S.; Tausch, A.; Ontrup, G.; Gilles, B.; Peifer, C.; Kluge, A. Defining human-AI teaming the human-centered way. Front. Artif. Intell. 2023, 6, 1250725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dee, T.S.; Geiser, K.; Gerstein, A.; Pyne, J.; Woo, C. Impact Report: San Mateo County Community Wellness and Crisis Response Team; John W. Gardner Center for Youth and Their Communities: Stanford, CA, USA, 2004; Available online: https://gardnercenter.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/media/file/ImpactReport_2024-10-15.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Meadi, M.R.; Sillekens, T.; Metselaar, S.; van Balkom, A.; Bernstein, J.; Batelaan, N. Exploring the ethical challenges of conversational AI in mental health care: Scoping review. JMIR Ment. Health 2025, 12, e60432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollnagel, E. Safety-I and Safety-II: The Past and Future of Safety Management; CRC Press: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Su, C.; Du, P.; Deng, J.; Wang, X. Resource allocation for resilience and safety enhancement in resource-based cities under multi-dimensional interdependencies. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2025, 39, 6329–6346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trist, E.L. The Evolution of Socio-Technical Systems; Ontario Quality of Working Life Centre: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1981; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.