Abstract

This study examines the influence of agricultural labor policies on the sustainability and productivity of farming enterprises in Türkiye, with a particular focus on the sector’s increasing reliance on foreign labor. Using primary data collected through face-to-face surveys with 73 agricultural enterprises in the Çumra District of Konya Province during the 2023–2024 production year, supplemented by secondary data from national and international institutions, the research explores how workforce composition, policy regulations, and socio-economic factors affect farm performance. Descriptive and comparative statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS to evaluate demographic characteristics, employment patterns, wage structures, and satisfaction levels among local and foreign workers. The findings indicate that as farm size expands, the use of foreign labor—mainly from Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan—significantly increases, generating cost and productivity advantages but also raising concerns related to social integration and legal employment barriers. Local labor demonstrates greater competence in mechanization but remains insufficient in quantity, deepening the existing labor shortage. A substantial majority (91%) of producers consider current labor regulations restrictive and emphasize the need for government incentives, vocational training programs, and simplified permit procedures for foreign workers. The results highlight the importance of inclusive and adaptive labor policies that harmonize economic efficiency with social cohesion, supporting the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 2, 8, and 11—Zero Hunger, Decent Work and Economic Growth, and Sustainable Cities and Communities.

1. Introduction

The agricultural sector remains a cornerstone of economic growth, employment, and rural development in both developed and developing economies. However, in recent decades, structural transformations—including demographic aging, rapid urbanization, technological change, and climate-induced production risks—have created substantial challenges for the availability, stability, and quality of agricultural labor. In countries such as Türkiye, which possesses significant agricultural potential but faces a rapidly evolving rural labor structure, the effectiveness of agricultural labor policies has become critical for sustaining productivity and ensuring the long-term viability of agricultural holdings. Because the vast majority of Turkish farms are family-based, labor policies directly influence labor allocation decisions, income distribution, production strategies, and the overall social resilience of rural communities. The increasing reliance on seasonal workers, growing informality, youth out-migration, and dependence on migrant labor further amplify the socioeconomic implications of labor-related policy frameworks.

Labor is one of the fundamental factors of production, and its efficient use is indispensable for national economic development. Agriculture continues to be among the most labor-intensive sectors, requiring a balanced policy approach that simultaneously supports rural employment and ensures fair remuneration aligned with productivity levels. Agricultural labor typically consists of both hired and family workers [1]. However, generally low educational attainment among agricultural workers, combined with declining participation in vocational or technical training programs, has constrained human capital formation in rural areas [2,3]. These structural challenges highlight the need to modernize agricultural labor management and strengthen policy mechanisms governing rural labor markets.

Similar labor dynamics have been documented across Europe. Molinero-Gerbeau [4] and Macrì [5] demonstrate that migrant labor has become increasingly essential for maintaining production continuity in Mediterranean agriculture, although this reliance often occurs within informal, precarious, and socially vulnerable employment structures. Such findings underscore the persistent tension between economic efficiency and decent work standards—an issue central to the design and evaluation of agricultural labor policies globally.

Worldwide, agriculture has undergone a major transformation. Although the absolute number of individuals employed in agriculture has increased, the sector’s share in total employment has steadily declined [6]. In many developed economies, agricultural employment now represents less than 5% of the total workforce [7], reflecting the combined effects of mechanization, rising labor productivity, and structural reforms. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization [8], more than 892 million people—approximately 26% of the global workforce—are employed in agriculture, with the majority residing in developing countries. Despite the declining share of agricultural employment, the sector remains a key contributor to poverty reduction, food security, and sustainable development [7,9]. Evidence from rural European regions further suggests that migrant workers contribute not only to agricultural productivity but also to the social revitalization and demographic stabilization of rural communities [10].

In Türkiye, the agricultural sector has experienced similar demographic and structural shifts. As of 2024, approximately 4.83 million individuals are employed in agriculture, accounting for 14.5% of national employment [11]. Rural areas with limited non-agricultural employment opportunities continue to rely predominantly on farming as the primary source of livelihood [12,13,14]. Economic pressures, social change, mechanization, and out-migration—particularly among younger generations [14,15,16,17]—have accelerated population aging in rural Türkiye, where the average age has increased to 58 years, significantly above the national average of 33 [11]. This demographic transition has reduced the active rural labor force, weakened intergenerational continuity, and intensified seasonal labor bottlenecks [13,18,19]. Comparable aging and labor-shortage trends have also been observed across Europe, where Fanelli [20] identifies demographic decline and skill shortages as major obstacles to sustaining agricultural productivity.

In recent years, Türkiye’s agricultural production model has become increasingly dependent on migrant labor. Political instability and large-scale displacement in the Middle East have resulted in the arrival of millions of refugees to Türkiye. Currently, approximately 3.7 million Syrians and 300,000 Afghans reside in the country, with an estimated 450,000–600,000 Syrians working in agriculture and 20,000–25,000 Afghans employed as shepherds [21]. Informal employment in the agricultural sector remains extremely high, reaching 83.5% [22]. This level of informality limits data reliability and complicates policy implementation. Farmers tend to prefer foreign workers due to lower labor costs, the withdrawal of local populations from agriculture, and the relatively higher productivity of migrant laborers [21].

Although prior research has examined agricultural subsidies, pricing policies, and rural development strategies, empirical studies explicitly examining how agricultural labor policies shape labor composition, foreign labor dependency, and the performance and sustainability of farm enterprises remain limited. This study seeks to address this gap by providing an empirical analysis of the interaction between agricultural labor policies and the rising reliance on foreign labor in the Çumra District of Konya.

The primary aim of this study is to examine how Türkiye’s agricultural labor policies intersect with labor market realities—particularly the dependence on foreign workers—and how these dynamics influence labor allocation, wage structures, and the socioeconomic sustainability of agricultural holdings in the Çumra District. Building on empirical patterns observed in the field data and grounded in dual labor market theory and the sustainable livelihoods framework, the study develops the following hypotheses:

H1.

Larger agricultural holdings exhibit significantly higher dependence on foreign labor than small-scale family farms, largely due to increased labor demand and the withdrawal of local workers from agricultural employment.

H2.

Current agricultural labor policies—especially work permit systems, employment regulations, and administrative procedures—shape farmers’ hiring practices, wage decisions, and long-term labor strategies, thereby influencing the sustainability and resilience of agricultural enterprises.

These hypotheses guide empirical analysis and establish a conceptual link between micro-level labor dynamics and broader policy debates surrounding labor shortages, migration, and sustainable rural development.

2. Labor Policies in Agriculture

2.1. Conceptual Background

Labor is one of the fundamental factors of production and a key determinant of agricultural sustainability. In this study, sustainability is addressed as a multidimensional construct reflecting the long-term viability of agricultural production through economic efficiency, social workplace cohesion, and compliance with institutional and regulatory frameworks. According to the dual labor market theory, economies tend to divide employment structures into formal and informal segments, where agriculture—particularly in developing and emerging countries—tends to absorb low-wage and migrant workers to compensate for labor shortages. This segmentation leads to both efficiency and equity challenges, as agricultural workers often operate outside formal labor protections. In the context of the sustainable livelihoods framework, agricultural labor policies influence not only productivity but also rural resilience, income stability, and social cohesion. Thus, the regulation and management of agricultural labor markets play a central role in achieving the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 2—Zero Hunger, SDG 8—Decent Work and Economic Growth, and SDG 10—Reduced Inequalities).

2.2. Labor Market Dynamics

Labor refers to the working-age population that provides effort for the production of goods and services within a given period. The total labor supply includes both employed and unemployed individuals [23]. Labor market performance depends on demographic composition, age distribution, and participation rates [24,25].

Globally, technological change, urbanization, and migration have reshaped labor markets. As of 2019, migrant workers constituted 4.7% of the global workforce [26]. By 2023, 281 million people—representing 3.6% of the global population—were living outside their country of birth [27]. Approximately 60% of these migrants, or 167.7 million individuals, actively participate in international labor markets, reflecting the increasing globalization of labor mobility. Migration flows are driven by both economic disparities and humanitarian crises: as of 2024, 120 million people were forcibly displaced due to conflict and persecution [28]. Migrant remittances reached USD 857 billion in 2023, underscoring migration’s dual role in supporting both host and origin economies [27]. From a policy and institutional perspective, De Rosa et al. [10] demonstrated that migrant labor contributes not only to production continuity but also to social revitalization and the multifunctionality of rural regions, suggesting that agricultural labor policies should integrate social inclusion and rural development goals simultaneously.

2.3. Evolution of Agricultural Labor in Türkiye

Since the establishment of the Republic in 1923, Türkiye’s economy has undergone a significant structural shift. During this period, 75% of the population resided in rural areas, agriculture accounted for 80% of total employment, and 85% of exports originated from agricultural products. Today, the sector’s share in total employment has declined to 14.5% [11]. Between 1980 and 2025, the agricultural workforce decreased from 9.3 million to approximately 4.8 million individuals, reflecting both urban migration and demographic aging.

This transformation has further intensified labor supply challenges. Rural-to-urban migration, the exodus of youth from agriculture, and the growing proportion of elderly farmers have intensified dependence on foreign labor. Türkiye, which hosts more than 4 million refugees and migrants, has become one of the world’s leading destinations for migrant agricultural labor [21]. Approximately 450,000–600,000 Syrians and 20,000–25,000 Afghans are currently engaged in agricultural or livestock production, particularly as seasonal workers and shepherds.

Despite its vital role, agricultural labor in Türkiye is characterized by high informality—83.5% according to SGK [22]—and limited access to social protection. Informality not only undermines workers’ rights but also weakens productivity and the resilience of rural livelihoods. Compared with OECD countries, where informal agricultural employment averages around 8–10%, Türkiye’s situation reveals a persistent institutional gap in labor regulation and enforcement.

2.4. Literature Insights and Policy Context

Previous studies have addressed different dimensions of agricultural labor. Dedeoğlu [29] emphasized that migrant workers are essential to sustaining production, particularly during harvesting stages, while Bayramoğlu and Bozdemir [30] proposed a clearer classification of agricultural labor types to enhance research consistency. Horuztepe [31] analyzed Law No. 6735 on the International Labor Force, which differentiates foreign and domestic employment regulations, especially regarding work permits and occupational restrictions. Us and Akbıyık [32] highlighted the widespread lack of social insurance among agricultural workers, noting that informal employment perpetuates vulnerability. Similarly, Yıldırım and Karakoyun [33] found that seasonal laborers face harsh conditions, low pay, and social exclusion in rural districts such as Çarşamba.

Taken together, these studies indicate that existing labor policies in Türkiye focus primarily on employment generation rather than sustainability or social protection, leaving migrant labor integration insufficiently regulated. Addressing these deficiencies requires a shift toward inclusive policy frameworks that recognize labor as both an economic input and a social foundation for rural development.

2.5. Policy Framework for Sustainable Agricultural Labor

For sustainable agricultural development, labor policies must evolve from short-term employment measures toward holistic, long-term, and rights-based approaches. Key strategic directions include:

- -

- Formalization and Social Protection: Expanding registration systems, implementing digital monitoring for seasonal workers, and extending social security coverage to foreign and local laborers.

- -

- Integration of Migrant Workers: Simplifying work permit processes and providing language and vocational training programs to enhance productivity and social cohesion.

- -

- Youth Engagement in Agriculture: Offering targeted incentives, rural entrepreneurship programs, and access to credit for young farmers to reverse the decline in agricultural participation.

- -

- Gender Equality: Promoting the visibility of women’s agricultural labor and ensuring equal access to social rights and training opportunities.

- -

- Technological and Institutional Support: Encouraging mechanization, automation, and data-driven labor management systems to increase efficiency and resilience.

Such measures are expected to contribute to a sustainable agricultural labor system that aligns with Türkiye’s rural development priorities and international commitments under the SDGs. A balanced approach integrating economic, social, and legal dimensions is essential for ensuring both productivity and equity in the agricultural workforce.

In this context, Macrì [5] argues that effective labor governance requires a combination of regulation, incentives, and institutional coordination to create fair, efficient, and socially sustainable labor systems.

3. Materials and Methods

This study utilized both primary and secondary data sources. Primary data were obtained through face-to-face surveys conducted with agricultural enterprises during 2024, while secondary data were compiled from the literature and official statistics provided by national and international organizations, including the Turkish Statistical Institute (TÜİK), the International Labor Organization (ILO), the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), and the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

3.1. Study Area

The research was conducted in the Çumra District of Konya Province, one of Türkiye’s most agriculturally productive regions. Çumra was purposively selected because of its intensive crop production, high labor demand, and a representative agricultural structure within the Central Anatolia region.

3.2. Sampling Design

To determine the representative number of farms, a stratified random sampling method was applied [34,35]. Based on a 99% confidence level and a 5% margin of error, the required sample size was calculated as 73 agricultural enterprises. The population was divided into four strata according to land size: 3–10 hectares (ha), 10.1–30 ha, 30.1–50 ha, and 50.1+ ha. The selected sample reflects the diversity of enterprise scales and production systems in the region. Although the sample is regional and modest in size, the study offers internally valid empirical insights into agricultural labor dynamics in one of Türkiye’s most intensive agricultural districts. These results are not intended as nationally generalizable outcomes but as regionally grounded evidence that contributes to broader labor policy discussions.

3.3. Survey Design and Data Collection

A structured questionnaire was designed to capture both quantitative and qualitative aspects of agricultural labor use. The survey consisted of closed-ended, open-ended, and 5-point Likert-scale questions, focusing on demographic characteristics, labor structure, wage patterns, satisfaction levels, and policy expectations. Data were collected from farm owners or managers through direct interviews, thereby ensuring consistency and reliability.

3.4. Measurement of Labor Availability

The availability of family labor was calculated in terms of Male Labor Units (MLU), following the conversion coefficients developed by Erkuş et al. [36]. These coefficients adjust labor capacity according to age and gender, as shown in Table 1. Although the MLU is used as a standardized technical measure for quantifying labor availability in agricultural studies, it does not imply gender-based valuation. In this study, MLU represents total household labor capacity irrespective of gender.

Table 1.

Coefficients Used in Converting Population into Male Labor Units.

The total labor force was derived by summing the equivalent male labor units for each household, allowing for comparisons across different farm sizes and demographic compositions [35,37,38].

3.5. Analytical Framework

To assess farmers’ perceptions of labor productivity and satisfaction, multiple Likert-scale questions were analyzed using descriptive statistics [39]. The data were analyzed using SPSS (v. 28) and Microsoft Excel software. Additionally, a SWOT analysis was conducted to evaluate the internal and external factors affecting agricultural labor dynamics and policy effectiveness [40,41].

3.6. Statistical Analysis

To strengthen the empirical examination of labor dynamics in agricultural enterprises, several statistical procedures were implemented in accordance with the structure of the dataset and the nature of the research questions.

Kruskal–Wallis H Test:

To compare differences in foreign labor dependency across farm-size groups, the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis H test was applied. This rank-based procedure, originally developed by Kruskal and Wallis [42] is appropriate when normality assumptions are not satisfied and allows for the evaluation of median differences across more than two independent groups. The test was used to determine whether foreign labor rates differ systematically between farms of varying scales.

Binary Logistic Regression Models:

To identify the key determinants influencing agricultural enterprises’ likelihood of employing foreign labor, binary logistic regression models were utilized. Logistic regression is appropriate when the dependent variable is dichotomous and allows for estimating the probability of an outcome as a function of multiple explanatory variables Hosmer and Lemeshow [43]. In this study, the models were used to evaluate how demographic characteristics of the farm operator (e.g., age, education), structural features of the enterprise (e.g., farm size, family labor capacity), and perception-based factors (e.g., perceived cost advantage, perceived efficiency of foreign workers) affect the decision to hire foreign labor. By estimating odds ratios and assessing the statistical significance of predictors, the method provides a robust analytical framework for understanding how economic, social, and structural conditions jointly shape labor hiring strategies in Turkish agriculture.

A second binary logistic regression model was applied to assess the determinants of farmers perceived positive effects of employing foreign labor. In this model, the dependent variable represented whether farmers reported a positive operational impact of foreign labor (0 = low, 1 = high). Independent variables included foreign labor use, age, education level, farm size, family labor capacity. This model was used to evaluate whether the perceived benefits of foreign labor are shaped primarily by structural factors (farm size, labor availability) or by attitudinal and experiential characteristics. The use of logistic regression enabled the estimation of marginal effects of these explanatory factors on the likelihood of perceiving foreign labor as beneficial.

Mann–Whitney U Test:

To examine pairwise differences between farms that employ foreign workers and those that do not, the Mann–Whitney U test was applied. This non-parametric test, originally developed by Mann and Whitney [44] is suitable for comparing two independent groups when distributional assumptions required for parametric testing are not satisfied.

3.7. Ethical Considerations

Participation in the survey was voluntary, and all respondents were informed about the purpose of the study. Data confidentiality and anonymity were strictly maintained in accordance with academic ethical standards.

4. Research Findings

4.1. Overview of Labor Structure

The demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the population play a significant role in shaping agricultural structures and determining sectoral sustainability [36]. Agriculture is inherently a labor-intensive activity in which household life and production processes are closely intertwined. Consequently, the sustainability of agricultural enterprises depends heavily on the availability, skill level, and continuity of the labor force [45].

In the surveyed farms, the average farm size was 30.85 hectares, and the average household size was 3.46 people. Based on Male Labor Unit (MLU) calculations, the average available family labor was 2.73 MLUs (Table 2). Approximately 92.7% of household members participated directly in agricultural activities, while an estimated 29.2% of the potential labor capacity remained underutilized, indicating partial inefficiencies in labor use.

Table 2.

Family labor force availability in the examined agricultural enterprises (MLU *).

The total labor force across the sample comprises 54.7% family labor and 45.3% foreign labor, illustrating the high dependency of agricultural enterprises on migrant workers. This finding is consistent with [29] and Mahiroğulları [46], who noted the growing reliance on foreign labor in Turkish agriculture and its implications for informality and social protection.

4.2. Family Labor Utilization and Efficiency

Table 3 reveals that labor utilization within family farms hectares as farm size increases. Smaller farms (3–10 ha) utilize 93% of available family labor within their own enterprises, whereas large farms (50.1+ ha) use only 65%. This suggests that mechanization, hired labor, and off-farm income diversification are more prevalent among larger enterprises.

Table 3.

Family labor potential and utilization status in the examined agricultural enterprises (MED *).

Approximately 29% of total family labor remains unused (idle), representing a hidden labor reserve that could be mobilized through targeted rural employment or cooperative initiatives. The negative correlation between farm size and family-labor utilization supports the hypothesis that as farms expand, owners increasingly substitute capital and hired labor for family labor inputs.

4.3. Dependence on Foreign Labor

The use of foreign labor in farms according to farm size groups is given in Table 4. To examine whether the share of foreign labor differs significantly across farm size groups, a Kruskal–Wallis H test was conducted. The analysis revealed a statistically significant difference in the distribution of foreign labor rates among the four farm size categories (H (3) = 9.12, p = 0.027). These results indicate that farm size is significantly associated with the proportion of foreign workers employed, supporting Hypothesis H1. “Post-hoc pairwise comparisons (Dunn test with Bonferroni correction) indicate that the significant differences are mainly between Group 1 (30–100 da) and Group 4 (501+ da) farms, where the foreign labor share is substantially higher in the largest farm category.” Larger farms tend to rely more heavily on foreign labor compared to smaller family-based holdings, likely due to higher labor demand, increased specialization, and the withdrawal of local workers from agricultural employment.

Table 4.

The Use of Family and Foreign Labor in Farms (MED *).

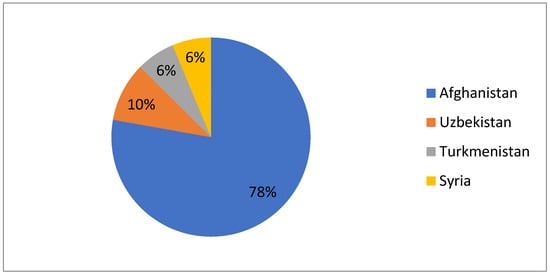

The analysis indicates that 86.7% of all non-family workers in the sample are foreign nationals. The distribution by nationality shows that Afghan workers dominate (77.8%), followed by Uzbek (9.6%), Turkmen (6.3%), and Syrian (6.3%) labor (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of Foreign Workers by Nationality (%).

Afghan workers are concentrated primarily in medium-sized farms (10.1–30 ha), preferred for their perceived discipline and work ethic. By contrast, Syrian workers are more prevalent in larger farms (>50 ha), often as temporary harvest laborers. These patterns suggest a segmentation of the migrant workforce by both nationality and employment duration.

Employment data show that 72.8% of foreign workers are permanent and 27.2% are temporary (Table 5). Except for Syrians—most of whom are seasonal—foreign workers generally remain in long-term employment relationships, reflecting the structural nature of migrant dependency in the regional agricultural economy.

Table 5.

Distribution of Foreign Workers in the Examined Agricultural Enterprises by Duration of Employment.

A logistic regression model was constructed to identify the factors that influence whether agricultural enterprises employ foreign workers. The dependent variable was a binary indicator of foreign worker use (0 = no, 1 = yes), while the independent variables included the age and education level of the farm operator, farm size, family labor capacity (MLU), cost advantages of foreign workers, higher success perception, positive effect perception, and work efficiency of foreign workers (Table 6).

Table 6.

Binary Logistic Regression Model Predicting the Use of Foreign Labor.

The overall performance of the binary logistic regression model indicates that the specification is statistically acceptable and provides meaningful explanatory power regarding the determinants of foreign labor use among agricultural enterprises. The model chi-square value is marginally significant (p = 0.090), suggesting that the set of predictors collectively contributes to explaining variation in the dependent variable rather than representing a null or empty model. The Nagelkerke R2 value of 0.493 further demonstrates that approximately 49.3% of the variance in foreign labor use is explained by the model, indicating a moderate-to-strong explanatory capacity for a socio-economic dataset of this nature. In addition, the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test yields a non-significant result (p = 0.973), confirming that the model aligns well with the observed data and does not exhibit problems of misfit. The classification table shows that the model correctly predicts 74% of cases, which reflects a satisfactory level of predictive accuracy. Collectively, these diagnostics indicate that the model is robust, statistically reliable, and suitable for interpreting the influence of demographic, structural, and perceptual factors on the likelihood of employing foreign labor.

The results of the binary logistic regression model provide important insights into the factors that shape the likelihood of employing foreign workers among agricultural enterprises. Several demographic, structural, and perceptual variables emerged as significant predictors of foreign labor use (Table 6).

Age group shows a positive and significant effect (B = 0.312, p = 0.027), indicating that older farm operators are more likely to hire foreign workers. This finding aligns with literature suggesting that aging farmers increasingly rely on external labor sources as their physical work capacity decreases and family labor becomes insufficient.

Farm size is another significant determinant (B = 0.004, p = 0.024). Larger holdings exhibit a higher probability of employing foreign labor, consistent with the greater labor requirements, scale of operations, and year-round workload associated with medium and large-scale enterprises. This supports the study’s first hypothesis (H1), which proposed that foreign labor dependency increases with farm size.

Family labor availability, measured through Male Labor Units (MLU), has a negative and statistically significant effect (B = −1.104, p = 0.046). Farms with greater family labor capacity are less likely to hire foreign workers, highlighting the substitutive relationship between household labor and external labor markets. This underscores the central role of family-based production structures in determining labor strategies.

Among the perception-based variables, the cost advantage of foreign labor is a strong positive predictor (B = 0.756, p = 0.022). Farmers who perceive foreign labor as more affordable are more inclined to employ non-local workers, reflecting market-driven labor allocation decisions. Similarly, the belief that foreign workers perform tasks more efficiently (“efficiency advantage”) significantly increases the likelihood of foreign labor use (B = 0.691, p = 0.013). These perceptions demonstrate that economic and productivity considerations play a critical role in adoption decisions. Recent evidence indicates that migrant labor can reduce labor costs and expand production capacity, particularly in low-skilled and informal market segments, thereby reshaping native workers’ employment conditions” [47].

Other perceptual factors—including higher success perception and perceived positive effects on operations—exhibit marginal significance (p = 0.053 and p = 0.067, respectively), suggesting a tendency for farmers with favorable evaluations of foreign labor to adopt such practices, although these effects do not reach conventional significance thresholds.

Education level appears to have a negative but statistically non-significant effect (p = 0.061), indicating that while more educated farmers may be somewhat less dependent on foreign labor, this association is not robust.

Overall, the regression results reveal that foreign labor use is primarily shaped by structural constraints (farm size, family labor sufficiency), demographic characteristics (operator age), and economic motivations (perceived cost and efficiency advantages). These findings provide empirical support for the argument that foreign labor has become an adaptive strategy for addressing labor shortages, rising production demands, and the demographic transformation of rural areas. Labor productivity is identified as a core component of sustainable agricultural development, reinforcing the need for coherent labor policies in rural regions [48].

The results of the logistic regression analysis provide important insights into the determinants of foreign labor use among agricultural enterprises in Türkiye. The findings suggest that both structural and perceptual factors significantly shape farmers’ decisions to employ foreign workers. Farm size emerges as a key determinant, with larger farms showing a higher likelihood of hiring foreign labor. This result is consistent with international literature indicating that labor-intensive and commercially oriented farms tend to rely more heavily on migrant workers to meet seasonal labor demands [4,5]. The positive association between age group and foreign worker use suggests that older farm operators may prefer foreign workers due to their perceived reliability and workload capacity, echoing findings from European agricultural labor studies that highlight aging farmers’ increasing dependence on migrant labor.

Family labor capacity (MLU) has a negative and statistically significant effect, indicating that farms with sufficient household labor are less likely to depend on foreign workers. This aligns with dual labor market theories, which emphasize how family labor availability shapes hiring decisions and reduces reliance on external labor sources. Perceptual variables—especially cost advantages and perceived efficiency of foreign workers—also play an important role. The significance of these variables supports previous research showing that migrant workers are often perceived as more cost-effective and more efficient in performing physically demanding tasks, particularly in contexts where local labor supply is limited or unwilling to engage in agricultural work.

Although education level and certain perception variables did not reach statistical significance at the 5% threshold, their marginal p-values indicate trends worth exploring in future studies with larger samples. The moderate-to-strong explanatory power of the model (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.493) suggests that both socio-demographic and attitudinal factors contribute meaningfully to understanding hiring decisions.

Overall, these findings reinforce the view that foreign labor dependency is not merely a response to labor shortages but is shaped by broader structural transformations in rural labor markets, including demographic aging, declining family labor availability, and farmers’ perceptions of productivity and cost efficiency. The results also highlight the need for labor policies that balance the economic benefits of migrant labor with social integration, fair working conditions, and long-term rural sustainability.

To further examine whether key demographic, structural, and perceptual characteristics differ between enterprises that employ foreign workers and those that do not, a Mann–Whitney U test was conducted (Table 7). The results indicate that age is the only variable that shows a statistically significant difference between the two groups (U = 431.0, p = 0.012), suggesting that farms employing foreign workers tend to be operated by older producers. This finding is consistent with the broader demographic trends observed in rural Türkiye, where aging farmers increasingly rely on hired labor due to declining physical capacity and limited availability of family labor.

Table 7.

Mann–Whitney U Test Comparing Farms With and Without Foreign Workers.

Although the remaining variables—education, farm size, family labor capacity, cost advantage perception, and success perception—do not reach statistical significance at the 5% level, several exhibit p-values close to conventional thresholds. This suggests potentially meaningful differences that may become statistically observable in larger or more regionally diverse samples. As such, these findings complement the logistic regression results by highlighting that structural and perceptual factors may still play a role in foreign worker utilization, even if the present sample size limits full statistical detection.

4.4. Labor Shortages and Wage Differentials

The results indicate that 61% of producers experience labor shortages, a key constraint on productivity. Even when workers are available, continuity problems persist due to high turnover and legal uncertainties. Consequently, labor scarcity drives wage inflation, particularly during harvest periods.

Average monthly wages highlight a clear differentiation:

Permanent foreign workers: 30,000 TL (~1000 USD)

Temporary foreign workers: 33,000 TL (~1100 USD)

Permanent local workers: 37,000 TL (~1233 USD)

Temporary local workers: 39,000 TL (~1300 USD)

While local workers earn roughly 20–25% higher wages, producers report preferring foreign labor due to lower cost, reliability, and productivity advantages. In total, 86.7% of surveyed farmers express a preference for employing migrants. This finding aligns with international studies showing that wage differentials are not the sole determinant of hiring decisions—availability and perceived reliability play equally important roles. Evidence from Venezuela–Colombia migration flows shows that migrant labor often fills low-wage, labor-intensive positions avoided by local workers [47]. A comparable pattern emerges in Türkiye, where foreign workers tend to concentrate in tasks characterized by high physical intensity and low domestic labor supply.

4.5. Employer Perceptions and Policy Expectations

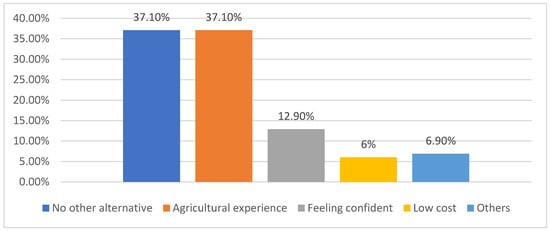

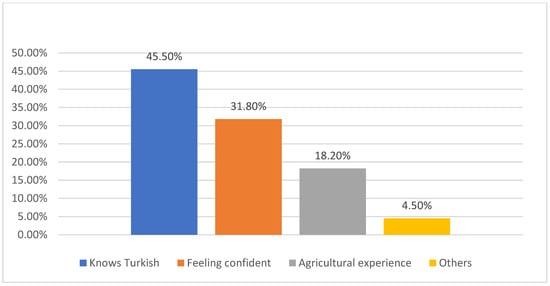

Farmers’ preferences and satisfaction levels reflect pragmatic considerations rather than socio-cultural attitudes. Local workers are valued mainly for their ability to communicate in Turkish (45.5%) and for perceived trustworthiness (31.8%), whereas foreign workers are preferred because of their agricultural experience and the absence of viable local alternatives (each 37.1%) (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Distribution of Producers’ Reasons for Preferring Local Workers (%).

Figure 3.

Distribution of Producers’ Reasons for Preferring Foreign Workers (%).

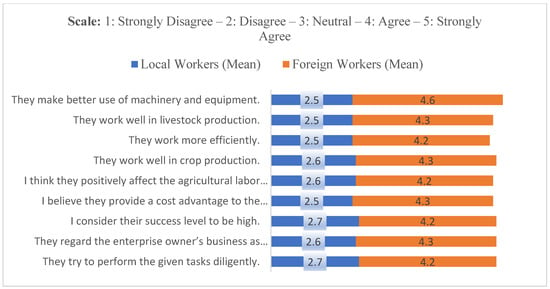

Figure 4 illustrates that producers generally evaluate foreign labor more positively than local labor across productivity, cost, and dedication criteria. However, bureaucratic restrictions on foreign employment are viewed as a major obstacle: 91% of producers believe that legal barriers limit their access to necessary labor.

Figure 4.

Employer’s Satisfaction with the Workforce.

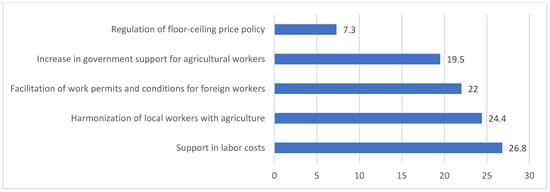

Regarding policy expectations (Figure 5), the most common demands include: Labor cost support (26.8%), Incentives for domestic workers (24.4%), Simplification of foreign work permits (22%), Increased social and insurance support (19.5%), and price-policy regulation (7.3%).

Figure 5.

Producers’ policy expectations regarding the labor force (%).

These expectations reveal that producers view labor policy primarily through an economic lens, emphasizing cost reduction and administrative flexibility rather than long-term social integration measures. In this study, social integration refers to the degree of institutional, cultural, and interpersonal adaptation between local and foreign workers within agricultural enterprises, shaping labor stability and cooperation dynamics.

4.6. Anticipated Strategies for Labor Sustainability

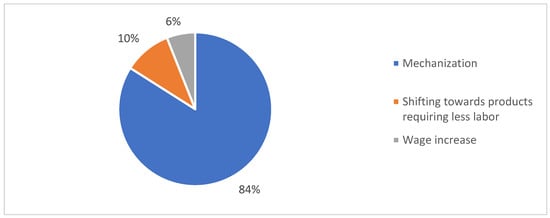

Producers’ future labor strategies (Figure 6) demonstrate an adaptive approach to labor scarcity: 84% intend to invest in mechanization, 10% plan to switch to less labor-intensive crop patterns, and 6% aim to increase wages to retain workers.

Figure 6.

Future labor force strategies in enterprises (%).

These strategies indicate a gradual transition toward capital substitution and technology-driven production, which may enhance efficiency but also risk reducing rural employment opportunities in the long term.

When interpreted through the lens of sustainability, this trend underscores the necessity for balanced policy design—promoting mechanization while ensuring decent work standards and the inclusion of vulnerable labor groups.

The binary logistic regression model developed to assess the determinants of farmers’ positive perceptions toward foreign labor demonstrates an acceptable overall model fit and provides meaningful explanatory insights (Table 8). The model chi-square value indicates that the set of predictors collectively improves the explanatory power compared to a null model, while the Nagelkerke R2 of 0.312 shows that approximately 31.2% of the variance in positive effect perception is accounted for by the included variables—an adequate level for socio-economic field research based on survey data. The Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit statistic yields a non-significant result, confirming that the model aligns well with the observed data and does not suffer from specification errors. The classification accuracy of 68% further supports that the model performs reasonably well in predicting positive perception categories.

Table 8.

Binary Logistic Regression Model Predicting the Level of Positive Effect Perception.

Regarding individual predictors, the results reveal that most demographic and structural variables do not exert statistically significant effects on farmers’ perceptions. Neither the age nor the education level of the farm operator shows a meaningful influence, suggesting that positive evaluations of foreign labor are not strongly shaped by personal characteristics. Similarly, farm size is not a significant predictor, indicating that perceptions do not necessarily differ between small- and large-scale enterprises. Among the examined determinants, family labor capacity (MLU) emerges as the only variable with a statistically significant effect (B = −0.551, p = 0.042). This negative association implies that farmers with higher levels of available family labor are less likely to hold positive perceptions of foreign labor, likely because family-based production systems reduce dependence on external workers and moderate attitudes toward their contributions. Although foreign worker use, cost advantages, and efficiency-related factors were expected to influence perception levels, these variables remain statistically insignificant in this reduced model specification.

Taken together, these findings suggest that while the model sufficiently meets statistical adequacy criteria, positive perceptions toward foreign labor are primarily shaped by household labor dynamics rather than demographic or economic considerations. In contexts where family labor is limited, farmers may perceive foreign workers more favorably due to their contribution to reducing labor shortages and maintaining production continuity. Conversely, farms with adequate internal labor resources tend to exhibit more neutral or less positive perceptions. This highlights the central role of household labor availability in shaping attitudinal responses toward migrant labor in rural agricultural systems.

The findings of this study provide important insights into the evolving dynamics of agricultural labor in Türkiye, particularly in the context of rising dependence on foreign workers. The descriptive results and regression analyses collectively indicate that foreign labor has become a structural and strategic component of agricultural production rather than a temporary response to short-term labor shortages. This aligns with international evidence demonstrating that migrant labor plays an increasingly central role in sustaining agricultural output in countries facing demographic aging and declining rural labor availability [4,5].

The logistic regression results show that farm size, cost advantages, perceived work efficiency, and limited family labor capacity significantly influence producers’ decisions to employ foreign workers. Similar patterns have been documented in Mediterranean and European agriculture, where larger farms and labor-intensive production systems exhibit higher demand for migrant labor due to year-round workload and scale-related labor needs. The significant negative effect of family labor availability confirms the persistence of the family farm model, echoing prior work suggesting that household labor remains a critical determinant of labor allocation strategies in rural economies.

The findings also suggest that economic motivations—especially cost considerations and efficiency gains—are key drivers of labor substitution and complementarity. This is consistent with dual labor market theory, which posits that employers often rely on migrant labor to fill low-wage, low-prestige, or physically demanding tasks that local workers are unwilling to perform. At the same time, the non-significant but directionally meaningful associations of positive perceptions indicate that social and experiential factors may also influence hiring decisions, though these are secondary to structural and economic determinants.

Overall, the results support the argument that agricultural enterprises are adapting to broader demographic and labor market transformations by integrating foreign workers into their labor strategies. However, the findings also highlight mismatches between existing policy frameworks and labor market realities—particularly regarding informality, bureaucratic barriers to work permits, and the need for clearer institutional coordination. These limitations resonate with previous studies emphasizing the importance of aligning labor governance with the practical needs of rural producers while safeguarding worker rights and social cohesion.

4.7. Synthesis and SWOT Interpretation

The integrated SWOT analysis (Table 9) provides a comprehensive overview of Türkiye’s agricultural labor system.

Table 9.

SWOT Analysis of Agricultural Labor Force Policies.

Strengths include the availability of foreign labor, the persistence of traditional agricultural knowledge, and relatively low labor costs.

Weaknesses involve widespread informality, cultural barriers, and inadequate legal protection.

Opportunities arise from integrating migrant workers into formal labor markets and expanding vocational training.

Threats include social tensions, displacement of local labor, and the long-term erosion of rural employment through mechanization.

These findings suggest that labor policy reform must balance productivity, equity, and sustainability. Policies that encourage formalization, protect worker rights, and link technological modernization with inclusive labor practices are essential to ensuring resilient and socially cohesive rural economies.

Recent literature emphasizes that migrant labor should not be perceived solely as a temporary or low-cost solution but as a structural component contributing to the multifunctionality of agricultural systems. De Rosa et al. [10] highlighted that immigrant workers in Italian agriculture play a pivotal role not only in ensuring production continuity but also in revitalizing rural areas socially and demographically. Their integration into local farming systems supports innovation, diversification, and social sustainability. This perspective aligns with the findings of the present study, which demonstrate that foreign labor in Türkiye similarly enhances production efficiency while addressing demographic decline in rural regions. Therefore, agricultural labor policies should recognize the multifaceted contributions of migrant workers and design inclusive frameworks that promote both economic productivity and rural resilience.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

This study offers an empirical assessment of the agricultural labor structure in Türkiye, revealing that labor-related challenges in rural production are intensifying while dependence on foreign workers is rapidly expanding. Although foreign labor offers cost and productivity advantages, the role of domestic labor remains essential in mechanization, farm management, and knowledge transfer. The findings demonstrate that agricultural enterprises are increasingly integrated into a dual labor system, where domestic and foreign labor coexist under asymmetric legal and social conditions. The binary logistic regression and non-parametric statistical analyses provide empirical evidence reinforcing these structural patterns, indicating that farm size, family labor availability, and economic perceptions are key drivers shaping foreign labor employment.

The widespread employment of workers from Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan indicates that these migrant groups have become structural components of Turkish agriculture rather than temporary substitutes. However, excessive bureaucratic restrictions on foreign employment hinder the sustainable supply of labor and create uncertainty for producers. Balancing labor demand and social integration is thus central to ensuring both productivity and rural cohesion. In particular, logistic model results indicate that producers’ perceived cost advantages and efficiency gains significantly increase the likelihood of foreign labor use, while greater family labor capacity reduces dependence on external workers. These findings highlight the need for policy instruments that alleviate structural labor shortages rather than solely relying on informal or short-term labor arrangements.

The results highlight that agricultural labor policies must move beyond short-term responses and adopt comprehensive, multi-dimensional frameworks that address economic efficiency, social justice, and institutional reform. Statistically significant model diagnostics—such as a strong model fit (Hosmer–Lemeshow p = 0.973), an acceptable classification accuracy (74%), and a moderate-to-high explanatory power (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.493)—indicate that the empirical relationships identified in this study are robust and can meaningfully inform long-term policy design. In this regard, the study’s findings underscore the need for coordinated, evidence-based interventions that strengthen both labor productivity and the resilience of rural livelihoods. The key policy implications and recommendations are summarized below.

5.1. Economic and Productivity-Oriented Recommendations

Reduce labor costs through targeted subsidies and premium support mechanisms, while ensuring transparency and accountability in their implementation. Such financial mechanisms can ease producers’ dependency on informal labor markets and contribute to stabilizing long-term labor availability. Given that cost advantage is a significant predictor of foreign labor use (p = 0.022), subsidies designed to balance wage disparities between local and foreign workers could help regulate the labor market and reduce informality.

Encourage youth participation in agriculture by offering entrepreneurship programs, access to microcredit, and start-up grants that promote sustainable rural employment. This approach is vital in reversing demographic aging trends and creating a renewed domestic labor supply. Model results showing age as a significant determinant of foreign labor use (p = 0.027) indicate that younger farmers could reduce long-term dependency on migrant labor.

Implement productivity-linked wage systems to align compensation with output, thereby improving motivation and equity among workers. Linking wages to performance can also help reduce conflicts between domestic and foreign workers regarding perceived workload disparities. Efficiency perceptions were found to significantly influence labor choices (p = 0.013), implying that productivity-sensitive incentive mechanisms could enhance labor harmony and farm-level efficiency.

5.2. Social and Human Capital Development

Improve working conditions, making agricultural employment more attractive to domestic labor through improved housing, fair wages, and secure contracts. Improving job quality is essential for restoring the competitiveness of local labor relative to migrant workers.

Provide continuous vocational training to both local and migrant workers, focusing on modern agricultural practices, mechanization, and digital skills. Training programs can mitigate skills mismatches and improve overall labor productivity across farm types. Given that education level showed a negative (though non-significant) association with foreign labor use, skill development initiatives may help to amplify the role of local labor in modern agricultural tasks.

Foster social integration by introducing language and cultural orientation programs for foreign laborers to promote mutual understanding and community cohesion. Strengthened social cohesion reduces workplace tensions and supports safer, more inclusive working environments.

5.3. Institutional and Legal Framework

Simplify work permit regulations for seasonal and permanent foreign workers, while enforcing labor rights and occupational safety standards. A streamlined legal framework can reduce informality and strengthen regulatory compliance among employers. The model results indicate that structural constraints—rather than individual preferences—primarily motivate foreign labor use. Therefore, easing bureaucratic burdens while improving regulatory oversight is essential for a well-functioning labor system.

Formalize employment relations by expanding digital registration systems and linking them with social security databases to reduce informality. Digital systems also allow policymakers to monitor regional labor deficits more accurately and respond proactively.

Strengthen institutional coordination among the Ministry of Labor, Ministry of Agriculture, and local administrations to ensure coherent labor governance. Improved coordination will help align national labor policy with local labor market realities.

5.4. Technological and Sustainability Transitions

Promoting mechanization and smart agriculture technologies can reduce dependency on manual labor while increasing production efficiency. Technological adoption is especially crucial for large enterprises that report chronic labor shortages.

Investments in renewable energy and precision farming systems can contribute to the creation of sustainable, climate-resilient employment opportunities. These investments enhance environmental performance while supporting higher-skilled rural jobs.

Labor policies should be integrated into the broader sustainability agenda, with interventions aligned with SDGs 2 (Zero Hunger), 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), and 10 (Reduced Inequalities). Aligning labor strategies with global goals strengthens the policy legitimacy and long-term strategic direction of agricultural reform.

The study’s empirical evidence provides concrete pathways for linking agricultural labor dynamics to sustainability objectives, particularly through improved labor governance and equitable workforce strategies.

5.5. Concluding Remarks

Effective management of agricultural labor policies is fundamental for ensuring both economic sustainability and social cohesion in Türkiye’s rural areas. Achieving a balanced integration of domestic and foreign labor requires adaptive policy instruments that are inclusive, equitable, and forward-looking. The empirical models presented in this study suggest that foreign labor use is not merely a short-term response to labor shortages, but a structural adjustment strategy shaped by demographic trends, farm size, and economic perceptions.

Future policies should prioritize generational renewal, labor market modernization, and lawful integration mechanisms that support both productivity and human dignity. The future of agricultural sustainability depends on transforming labor governance—from a reactive framework addressing immediate shortages to a proactive model that strengthens productivity, human dignity, and rural well-being in harmony with global sustainability goals. Future studies could expand the sample to multiple regions and incorporate time-series data to assess the long-term effects of labor policies on farm performance.

Author Contributions

The presented research was conjointly designed and elaborated. All the authors contributed both to the discussion and to the writing of this paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Selçuk University (protocol code E-29529695-900-876027, approval date: 16 November 2024) for studies involving human participants.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions related to survey respondents.

Acknowledgments

This article is derived from the master’s thesis of Nasir Ahmad Hamidy, entitled “Evaluation of The Impact of Labor Policies in Agriculture on Agricultural Enterprises; The Case of Çumra District”, completed at Selçuk University, Institute of Science, Department of Agricultural Economics, under the supervision of Hasan Arısoy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Iancu, T.; Adamov, T.C.; Petroman, C.; Şuba, A.; Pascariu, L. Aspects Characterizing the Labor Force from Romanian Agriculture. Agric. Manag./Lucr. Științifice Ser. I Manag. Agric. 2020, 22, 51. [Google Scholar]

- Gherman, R.; Dincu, A.-M.; Iancu, T.; Toader, C.S. Impact of Human Resources on Performance of Companies. Lucr. Științifice Manag. Agric. 2013, 15, 237–242. [Google Scholar]

- Otiman, P.; Mateoc-Sîrb, N.; Mănescu, C. Economie Rurală (Rural Economy); Mirton Publishing House: Timișoara, Romania, 2013; p. 61. [Google Scholar]

- Molinero-Gerbeau, Y.; López-Sala, A.; Șerban, M. On the Social Sustainability of Industrial Agriculture Dependent on Migrant Workers. Romanian Workers in Spain’s Seasonal Agriculture. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrì, M.C.; Orsini, S. Policy Instruments to Improve Foreign Workforce’s Position and Social Sustainability of the Agriculture in Italy. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roser, M. Employment in Agriculture. Our World in Data 2013. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/employment-in-agriculture (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- OECD. OECD Dataset; Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development: Paris, France, 2025. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/data/datasets.html (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- FAO. Food and Agriculture Data; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2024. Available online: https://www.fao.org/home/en (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Mortan, M.; Rațiu, P.; Vereș, V.; Baciu, L. A Global Analysis of Agricultural Labor Force. Manag. Chall. Contemp. Soc. 2016, 9, 57. [Google Scholar]

- De Rosa, M.; Bartoli, L.; Leonardi, S.; Perito, M.A. The Contribution of Immigrants to Multifunctional Agricultural Systems in Italy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TÜİK. Agricultural Statistics 2025; Turkish Statistical Institute: Ankara, Türkiye, 2025. Available online: https://data.tuik.gov.tr (accessed on 26 October 2025). (In Turkish)

- Gümüş, S.; Olgun, F.; Adanacıoğlu, H. Türkiye’de Kırsal Alanda Yoksulluğu Azaltma ve Gelir Çeşitliliği Yaratma Olanakları. Ege Üniv. Ziraat Fakültesi Dergisi 2012, 49, 275–286. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Aşkın, E.; Yayar, R.; Oktay, Z. Kırsal Göçün Ekonometrik Analizi: Yeşilyurt İlçesi Örneği. Cumhur. Üniv. İktisadi İdari Bilim. Derg. 2013, 14, 231–252. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz, E.; Turğut, U.; Tosun, D.; Gümüş, S. İzmir İlindeki Çiftçilerin Kırsal Nüfusun Yaşlanma Eğilimi ve Tarımsal Faaliyetlerin Devamlılığına İlişkin Görüşleri. Tarım Ekon. Derg. 2020, 26, 109–119. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Cebeci, B.; Oruç, E.; Kurtaslan, T. Kırsal Alanda Yaşayan Çocukların Gelecek Yaşamları ve Tarım Sektörü Konusundaki Düşünceleri. Türkiye 2014, 11, 3–5. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Yalçın, G.E.; Kara, F.Ö. Kırsal Göç ve Tarımsal Üretime Etkileri. Harran Tarım Ve Gıda Bilim. Derg. 2016, 20, 154–158. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevinç, G.; Davran, M.K.; Sevinç, M.R. Türkiye’de Kırdan Kente Göç ve Göçün Aile Üzerindeki Etkileri. İktisadi İdari Siyasal Araştırmalar Derg. 2018, 3, 70–82. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, D.; Yıldız, N.; Ilgaz, Y.; Güneş, M.; Yıldız, D. Türkiye’deki Tarımsal İşgücünün Demografik ve Yapısal Dönüşümü Projesi Ön Raporu; Su Politikaları Derneği Uygulama Araştırma Merkezi: Ankara, Türkiye, 2017. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, M.; Urinboyev, R.; Wigerfelt Svensson, A.; Lundqvist, P.; Littorin, M.; Albin, M. Migrant Agricultural Workers and Their Socioeconomic, Occupational, and Health Conditions—A Literature Review; Occupational Health Review; Lund University: Lund, Sweden, 2013; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Fanelli, R.M. Barriers and Drivers Underpinning Newcomers in Agriculture: Evidence from Italian Census Data. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donat, İ. Tarımda İthal İşçi Dönemi. Gazete Oksijen. 2021. Available online: https://gazeteoksijen.com/yazarlar/irfan-donat/tarimda-ithal-isci-donemi (accessed on 26 October 2025). (In Turkish).

- SGK. İstatistikler (Statistics); Sosyal Güvenlik Kurumu: Ankara, Türkiye, 2024. Available online: https://www.sgk.gov.tr/Home/Index2/ (accessed on 26 October 2025). (In Turkish)

- Gündoğan, N.; Biçerli, M.K. Çalışma Ekonomisi; Anadolu Üniversitesi Yayınları: Eskişehir, Türkiye, 2004. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Cerev, G.; Yenihan, B. İşgücü Piyasasi Temel Kavramlari Doğrultusunda Elaziğ İli İşgücü Piyasasinin Mevcut Durumu ve Analizi. Fırat Üniv. Harput Araştırmaları Derg. 2017, 4, 77–90. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- TÜSİAD. İşgücü Piyasası ve İşsizlik; Aralık: İstanbul, Türkiye, 2002; ISBN 975-8458-57-4. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- ILO. ILO Global Estimates on International Migrant Workers; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2024. Available online: https://www.iom.int/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- UNHCR. The UN Refugee Agency. 2024. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/tr/en (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Dedeoğlu, S. Tarımsal Üretimde Göçmen İşçiler: Yoksulluk Nöbetinden Yoksulların Rekabetine. Çalışma Toplum 2018, 1, 37–68. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Bayramoğlu, Z.; Bozdemir, M. Tarım Sektöründe İşgücü Terminolojisinin Tanımlanması. Turk. J. Agric. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 8, 773–783. [Google Scholar]

- Horuztepe, G.S. Türkiye’de Çalışan Yabancıların İş Kanunundan Kaynaklanan Hak ve Yükümlülükleri. Specialization Thesis, Uzmanlık Tezi T.C. Aile, Çalışma ve Sosyal Hizmetler Bakanlığı, Ankara, Türkiye, 2021. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

- Us, K.; Akbıyık, N. Tarım Sektöründe İstihdam ve Çalışanların Sosyal Güvenliği. EconHarran 2023, 7, 25–36. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım, M.; Karakoyun, O. Mevsimlik Tarım İşçiliği Üzerine Bir Araştırma: Çarşamba (Samsun) İlçesi Örneği. 19 Mayıs Sos. Bilim. Derg. 2023, 4, 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamane, T. Elementary Sampling Theory; Prentice Hall Inc.: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Düğmeci, H.Y. Yağlık Ayçiçeği Üreten Tarım İşletmelerinin Ekonomik Analizi: Konya İli Çumra İlçesi Örneği; Selçuk Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü: Konya, Türkiye, 2020. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Erkuş, A.; Bülbül, M.; Kıral, T.; Açıl, A.F.; ve Demirci, R. Tarım Ekonomisi, Ankara Üniversitesi Ziraat Fakültesi Eğitim. Araştırma Geliştirme Vakfı Yayınları 1995, 5, 298. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Oğuz, C.; Bayramoğlu, Z. Tarım Ekonomisi; Atlas Kitabevi: Konya, Türkiye, 2018. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Fidan, N. Bitkisel Üretimde Maliyet Değişiminin Hayvansal Ürün Piyasası Üzerine Etkisinin Kısmi Denge Modeli ile Açıklaması; Selçuk Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü: Konya, Türkiye, 2019. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Clason, D.L.; Dormody, T.J. Analyzing Data Measured by Individual Likert-Type Items. J. Agric. Educ. 1994, 35, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houben, G.; Lenie, K.; Vanhoof, K. A Knowledge-Based SWOT-Analysis System as an Instrument for Strategic Planning in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Decis. Support Syst. 1999, 26, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oğuz, C.; Karakayacı, Z. Tarım Ekonomisinde Araştırma ve Örnekleme Metodolojisi; Atlas Akademi: Konya, Türkiye, 2017. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Kruskal, W.H.; Wallis, W.A. Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1952, 47, 583–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmer, D.W.; Lemeshow, S. Applied Logistic Regression; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, H.B.; Whitney, D.R. On a Test of Whether One of Two Random Variables Is Stochastically Larger than the Other. Ann. Math. Stat. 1947, 18, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arısoy, H. Tarımsal Araştırma Enstitüleri Tarafından Yeni Geliştirilen Buğday Çeşitlerinin Tarım İşletmelerinde Kullanım Düzeyi ve Geleneksel Çeşitler İle Karşılaştırmalı Ekonomik Analizi-Konya ili Örneği. Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Selçuk Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü, Konya, Türkiye, 2004. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

- Mahiroğulları, A. Türkiye’de Kayıtdışı İstihdam ve Önlemeye Yönelik Stratejiler. Süleyman Demirel Üniv. İktisadi İdari Bilim. Fakültesi Derg. 2017, 22, 547–565. [Google Scholar]

- Prieto Bustos, W.; Castillo Robayo, C.D.; Campo Robledo, J.; Molina Dominguez, J. Impact of Venezuelan Migration on the Informal Workforce of Native Workers in Colombia. Economies 2024, 12, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Hu, J.; Huang, Q. Sustainable Development between Demonstration Farm and Agricultural Labor Productivity: Evidence from Family Farms in the Mountainous Area of Western China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.