1. Introduction

Hurricanes are among the most destructive natural hazards globally, producing widespread structural damage and generating millions of cubic yards of debris [

1,

2,

3]. Effective debris management is essential for minimizing risks to public safety, restoring infrastructure functionality, and accelerating recovery timelines [

4]. Climate change is intensifying the frequency and severity of Atlantic hurricanes, placing greater demands on disaster response systems [

5,

6]. In 2024, the Atlantic hurricane season recorded 18 named storms, 11 hurricanes, and 5 major hurricanes [

7]. A notable example is Hurricane Michael in 2018, which generated an estimated 37.4 million cubic yards of debris and triggered over

$1 billion in Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Public Assistance grants, mirroring the impact patterns of past high-intensity hurricanes such as Katrina [

8]. As such events become more frequent and severe, the development of predictive, automated debris detection systems is critical to improving resource allocation, accelerating clearance operations, and reducing logistical bottlenecks in post-disaster environments [

9,

10].

The evolution of debris estimation methods has progressed from labor-intensive manual surveys, often inconsistent due to subjectivity and access constraints, to aerial photography and satellite imagery, which expanded coverage and reduced human error [

9]. The integration of GIS-based tools improved spatial analysis, and advances in LiDAR, UAV photogrammetry, and terrestrial laser scanning enabled high-resolution, rapid data collection for post-hurricane assessments [

11,

12]. More recently, multispectral and hyperspectral imaging have enhanced material differentiation, further refining debris classification [

13,

14]. FEMA has also advanced its debris assessment capabilities through models such as Hazus-MH, which uses storm history, terrain data, and structural vulnerability assessments to estimate debris volumes [

15,

16]. While effective at a regional scale, these models struggle to capture fine-scale structural complexity and the rapid environmental changes that occur immediately after a hurricane [

17].

Artificial intelligence, particularly machine learning and deep learning, offers transformative potential for debris detection by combining automation with high classification accuracy [

18]. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and other deep learning methods applied to imagery and 3D point clouds have demonstrated superior recall and processing efficiency compared to manual inspection or traditional feature-based models [

19,

20]. Integrating AI with LiDAR point clouds has improved debris and partially collapsed structure detection, increasing recall by 20–30% over conventional methods [

21,

22]. Despite these advances, a clear research gap remains because few operational workflows systematically combine multiscale point cloud feature extraction with supervised learning to produce high-fidelity, transferable debris classification across spatially distinct disaster zones.

Compared to conventional LiDAR classification workflows and deep learning approaches, the Three-Dimensional Multi-Attributes, Multiscale, Multi-Cloud (3DMASC) framework offers several advantages. First, it computes over 80 multiscale geometric, radiometric, and echo-based features, enabling robust characterization of complex disaster environments [

23]. Second, its multi-cloud capability supports direct comparison of co-registered datasets from different sensors, preserving spectral and sampling characteristics [

23]. Third, the method is interpretable, with feature importance rankings and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis, both of which are often lacking in black-box machine learning and deep learning models [

23,

24]. These attributes make 3DMASC particularly suitable for disaster response scenarios where transparency, scalability, and adaptability to varying data sources are critical.

This study addresses this gap by developing and evaluating a machine learning-based workflow for hurricane debris classification using the 3DMASC framework in CloudCompare. The approach leverages a Random Forest classifier trained on bi-temporal LiDAR data to automate semantic labeling of both stable and damage-specific features, aiming to provide scalable and precise support for post-hurricane response operations. The primary hypothesis is that multiscale feature extraction combined with supervised learning can classify hurricane debris and structural damage from LiDAR point clouds with accuracy comparable to that achieved for persistent features. The guiding research question is whether a 3DMASC–Random Forest framework applied to bi-temporal LiDAR data can deliver accurate and transferable debris classification suitable for operational disaster response.

This work demonstrates the potential to significantly shorten disaster assessment timelines from weeks to hours, providing rapid situational awareness to prioritize high-impact clearance zones and support resource allocation. While the framework is highly effective for mapping stable features, additional refinements are needed for detailed damage classification before full operational deployment.

2. Methodology

2.1. The 3DMASC Framework

The 3DMASC [

23] framework was used for semantic classification of 3D point cloud data. Implemented as an open-source plugin in CloudCompare, 3DMASC calculates over 80 handcrafted features, including geometric descriptors such as curvature and roughness, radiometric statistics such as intensity mean and standard deviation, echo-based metrics, and dimensionality measures from principal component analysis. These features are computed at multiple spherical neighborhood scales, allowing the model to capture both fine and broad structural patterns. The “Multi-Cloud” capability enables direct comparison between co-registered point clouds from different sensors, preserving their spectral and sampling characteristics while supporting ratio and difference computations. Classification is performed with a supervised Random Forest model trained on a labeled subset of points, typically with no more than 2000 samples per class. Output includes per-point semantic labels, probability scores, and feature importance rankings, with interpretability supported through SHAP analysis.

2.2. Study Area and Data Sources

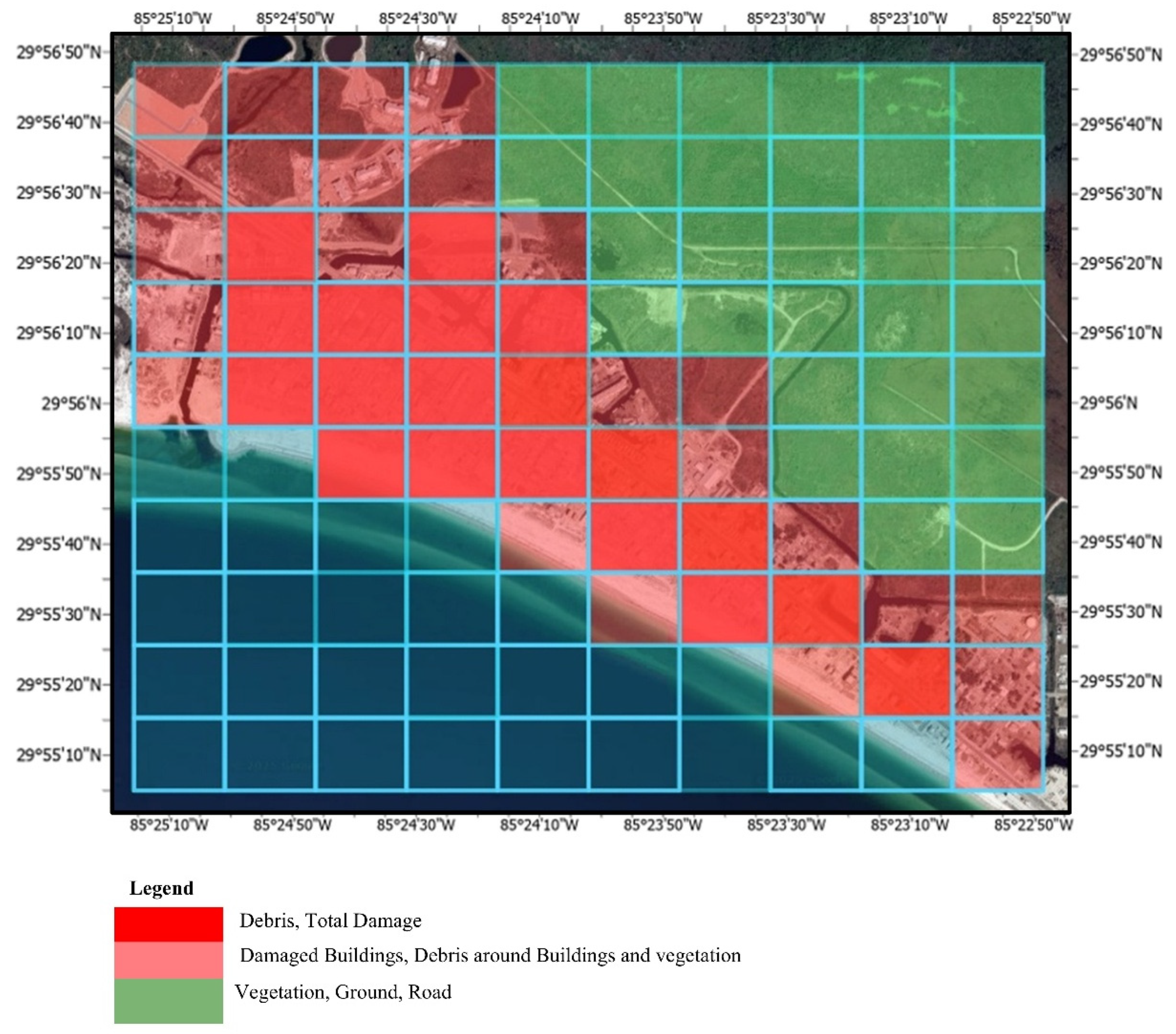

The study focuses on Mexico Beach (

Figure 1), a small coastal city in Bay County, Florida, USA (centered approximately at 29.94° N, 85.41° W), located along the Gulf of Mexico. The area lies on a low-lying coastal plain with elevations generally below 10 m above sea level. Sandy soils, sparse coastal vegetation, and a mix of residential, commercial, and recreational infrastructure characterize it. Its shoreline consists of sandy beaches backed by dune systems, interspersed with small inlets and marshes. The region is highly exposed to tropical cyclone impacts due to its location within the Gulf’s hurricane corridor.

On 10 October 2018, Hurricane Michael made landfall near Mexico Beach as a Category 5 storm with sustained winds of approximately 260 km/h and storm surge heights exceeding 4 m in some areas. The event resulted in catastrophic structural damage, widespread vegetation loss, and the deposition of substantial debris across the urban and natural landscape. Post-event surveys estimated more than 37 million cubic yards of hurricane-generated debris within the affected counties, with Mexico Beach among the most severely impacted locations.

The classification experiment utilized two bi-temporal topo-bathymetric LiDAR datasets to characterize pre- and post-hurricane conditions. The pre-hurricane dataset, “2017 Northwest Florida Water Management District (NWFWD) LiDAR: Lower Choctawhatchee,” was acquired by the NWFMD between 9 April and 17 May 2017. The post-hurricane dataset, “2018 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) FEMA Post-Michael Topobathy LiDAR: Florida Panhandle,” was collected by the USACE between 24 October and 4 November 2018. Both datasets were obtained from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration [

7] and delivered in the Log ASCII Standard [

19] format, containing XYZ coordinates, intensity values, and return numbers, but no Red, Green, or Blue (RGB) attributes.

To support visual interpretation and aid manual labeling, high-resolution aerial imagery was integrated into the workflow. Post-event imagery was sourced from the “2018 NOAA National Geodetic Survey (NGS) Disaster Supplemental Survey (DSS) Natural Color 8-Bit” dataset, while pre-event reference imagery was obtained from the “2017 NOAA NGS Oblique Natural Color 8-Bit” dataset. These datasets provided visual confirmation of structural conditions and debris presence where LiDAR features alone were insufficient.

2.3. Experimental Design and Data Preprocessing

Two non-overlapping areas were defined for training and testing. Zone A (training) covered approximately 2.37 km2, bounded by coordinates Xmin = −9,509,953.48, Ymin = 3,496,203.85 and Xmax = −9,508,209.76, Ymax = 3,497,560.60. Zone B (testing) covered approximately 0.95 km2, bounded by Xmin = −9,506,296.45, Ymin = 3,493,905.81 and Xmax = −9,505,274.10, Ymax = 3,494,851.72. Both zones shared similar environmental characteristics and urban structures, enabling the classifier to generalize effectively. The larger training zone was chosen to ensure exposure to diverse hurricane damage patterns and background features.

All point clouds were transformed into a standard projected coordinate system. Statistical outlier removal was applied to eliminate noise, and ground points were separated from off-ground points using a progressive morphological filter to separate ground from non-ground LiDAR returns, following the algorithm implementation described by [

25]. The pre- and post-hurricane datasets were co-registered using the iterative closest point ICP) alignment tool in CloudCompare to ensure spatial consistency between epochs. ICP is a widely used method for aligning 3D point clouds by minimizing the distance between corresponding points [

26].

2.4. Semantic Labeling

The training zone was subdivided into 100 uniform grids, each approximately 154 m × 154 m (23,700 m

2) in size, to facilitate systematic sampling for semantic labeling. These grids were used solely to organize the selection of training data and to ensure spatial diversity, not to represent LiDAR acquisition resolution. The LiDAR point density remained consistent with the original airborne survey specifications. Within each grid, semantic labeling was performed by integrating LiDAR-derived features with the auxiliary imagery. Ten semantic classes were defined based on relevance to hurricane damage detection and their distinguishable geometry in 3D point clouds: Ground, Road, Vegetation, Building, Ocean/Water, Vehicle, Fence, Power Line, Damaged Building, and Debris. Descriptions of these classes are provided in

Table 1. A maximum of 2000 points per class was used to maintain balanced training samples across categories with vastly different abundances. This threshold was selected after preliminary tests showed that increasing the sample count beyond 2000 per class did not improve classification accuracy but significantly increased training time. No explicit oversampling, cost-sensitive weighting, or synthetic data augmentation was applied; instead, we relied on the per-class cap to partially mitigate extreme class imbalance while preserving a simple, reproducible workflow. This threshold aligns with prior LiDAR classification studies [

27,

28]. It mitigates the extreme imbalance between stable classes (millions of points) and rare damage classes, preventing the Random Forest classifier from being dominated by overrepresented categories.

2.5. Feature Extraction

Feature computation in 3DMASC followed a standardized naming convention: [FeatureType]_[Scale]_[Statistic], where “Scale” refers to the spherical neighborhood diameter. The features selected for each class are shown in

Table 2 and were chosen based on a combination of prior literature [

29,

30] and empirical evaluation using feature importance scores from preliminary Random Forest runs. Features with consistently high importance and low redundancy were retained for each class. This format allowed precise control over feature selection and supported multiscale analysis. A complete description of all 3DMASC features used in this study is provided in

Supplementary Table S1.

2.6. Model Training, Classification, and Performance Evaluation

The Random Forest classifier was trained on the labeled dataset from Zone A (

Figure 2). Cross-validation in Zone A was conducted using a 5-fold scheme, with the manually labeled grid cells partitioned into spatially disjoint folds to avoid spatial autocorrelation between training and test samples. In each fold, 80% of the points were used to train the Random Forest model, and 20% were used for validation. The final trained model was then applied to the independent test zone (Zone B) for evaluation. Classification performance was assessed using a confusion matrix, overall accuracy, and per-class precision, recall, and F1-scores.

2.7. Assumptions

The pre-hurricane airborne LiDAR was acquired in 2017, and the post-hurricane collection was conducted several weeks after Hurricane Michael in 2018. To quantify and address this temporal mismatch, we restricted the training labels to features and structures known to be stable across acquisitions (e.g., ground, water, buildings, power lines). We inspected all training tiles using high-resolution imagery to ensure consistency. Damage-related labels were manually verified against post-event National Agriculture Imagery Program (NAIP) and NOAA imagery to minimize mislabeling. Although temporal mismatch introduces unavoidable uncertainty in the exact geometry of vegetation and small objects, our approach mitigates its influence on classification outcomes.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Pre-Hurricane Classification Performance

The pre-hurricane classification focused exclusively on stable, persistent land cover and infrastructure categories, as damage-related classes were absent before Hurricane Michael (

Figure 3). Using bi-temporal LiDAR data processed through the 3DMASC framework, the Random Forest classifier achieved an overall classification accuracy of 0.9711 when applied to approximately 20 million points in the training zone. These points correspond to the complete LiDAR coverage of Zone A after preprocessing and co-registration. The distribution follows the original acquisition pattern of the airborne LiDAR survey, which is generally uniform along flight lines. No random sampling was applied; instead, semantic labeling was performed on systematically defined grids as described in

Section 2.4. These points were distributed across six semantic classes: ground, road, vegetation, water, power lines, and other permanent structures. The spatial configuration of the pre-hurricane sampling is shown in

Figure 3.

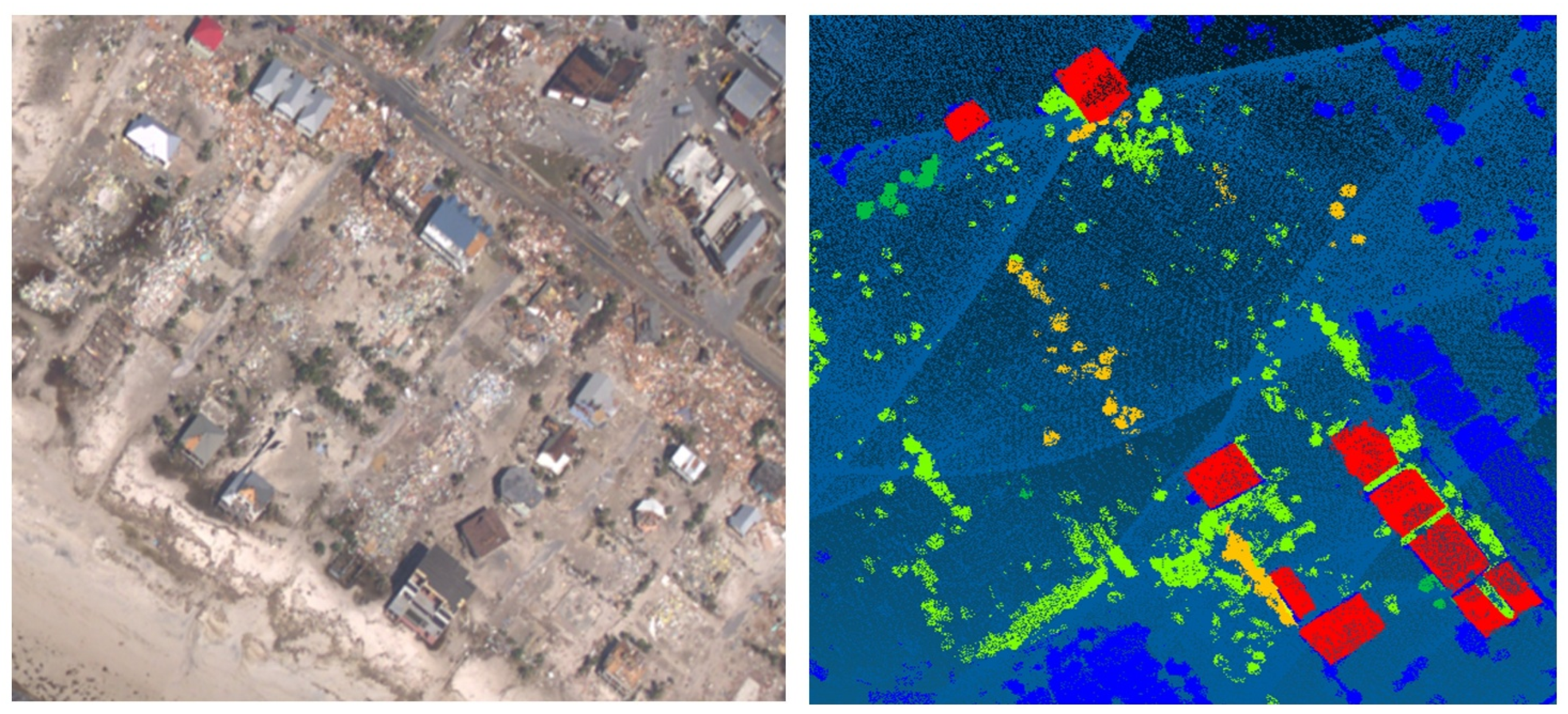

To illustrate the classification output in the pre-hurricane setting,

Figure 4 presents a side-by-side view of Zone A, showing the original pre-hurricane image alongside the corresponding segmented classification produced by the 3DMASC–Random Forest model. The reference image (

Figure 4a) provides the unclassified visual context of the study area. In contrast, the segmented map (

Figure 4b) depicts the predicted semantic classes, color-coded according to the class IDs defined in

Table 1. This visual comparison shows the model’s ability to delineate stable features such as ground, water, and power lines, while also revealing localized areas of confusion between similar classes, particularly along boundaries between ground, roads, and vegetation.

The corresponding confusion matrix (

Table 3) demonstrates consistently high performance for most stable classes. Ground (Class 2) achieved a precision of 0.998 and an F1-score of 0.86, although recall (0.75) was reduced due to confusion with roads and vegetation. Such misclassification is a well-documented challenge in LiDAR-based urban mapping, where similar elevation profiles and reflectance values between ground and adjacent surfaces can blur semantic boundaries. Previous work by [

24] has shown that while multiscale feature extraction can mitigate these effects, it cannot eliminate class overlap in heterogeneous urban environments.

Roads (Class 3) displayed substantial precision (0.943) but extremely low recall (0.093), indicating that many true road segments were misclassified as ground (

Table 3). This underdetection likely stems from surface blending caused by sediment deposition, pavement degradation, or occlusion by overhanging vegetation. A 2025 study by [

31] found similar issues in satellite-based road damage detection, where debris and vegetation significantly reduced model performance.

Vegetation (Class 4) was underrepresented in the training dataset, resulting in poor precision and a near-zero F1-score. Although recall reached 0.67, vegetation was frequently misclassified as ground, particularly in sparsely vegetated or flat areas. This misclassification is consistent with findings by [

32], who showed that low-stature vegetation and grasslands often return LiDAR signals similar to bare earth, especially in semiarid regions or sloped terrain. The absence of complementary RGB or multispectral data further magnifies this effect, making it challenging to distinguish vegetation from surrounding ground surfaces.

Water (Class 6) achieved near-perfect classification performance (F1-score: 0.99), aided by its flat geometry and consistently low-reflectance intensity values. These attributes are well-documented in LiDAR-based coastal and river mapping. Ref. [

33] demonstrated that water surfaces exhibit uniform radiometric and geometric profiles, making them highly distinguishable in airborne laser bathymetry.

Power lines (Class 11) recorded high precision (0.99) and recall (0.93), yielding an F1-score of 0.96 (

Table 3). Nonetheless, the confusion matrix revealed that some power line points were misclassified as ground (Class 2). This error is likely to occur where cables sag close to the ground or are partially obscured by nearby structures or vegetation, reducing their geometric distinctiveness. Ref. [

34] reported similar challenges in airborne LiDAR filtering, noting that thin, elevated features such as power lines are difficult to detect in cluttered environments, especially when surrounded by vegetation or complex urban surfaces.

As expected, no predictions were made for damage-related classes, Damaged Buildings (Class 17) and Debris (Class 18), in the pre-hurricane dataset. All values for these categories were recorded as non-applicable (NaN), confirming that the classifier did not erroneously assign damage labels to non-impacted areas.

3.2. Post-Hurricane Classification Performance

Following Hurricane Michael, the classification task was expanded to include damage-specific and transient classes in addition to the stable features assessed in the pre-hurricane analysis. The post-hurricane sampling design is shown in

Figure 5, with the trained Random Forest classifier applied to the independent test zone (Zone B). The corresponding post-disaster confusion matrix (

Table 4) shows an overall classification accuracy of 0.97, indicating the robustness of the 3DMASC framework in segmenting a diverse set of semantic classes in a highly complex, post-disaster environment.

Stable classes such as ground, roads, vegetation, buildings, and water retained consistently high performance, with precision and recall scores exceeding 0.95 in all cases. Ocean/water (Class 6) achieved near-perfect classification (F1-score: 0.99), reflecting its distinctive planar geometry and low-reflectance intensity profile. The work by [

33] on topo-bathymetric LiDAR confirms that water surfaces are highly separable due to their flat geometry and low radiometric reflectance, especially in shallow coastal and riverine environments. These properties hold across both pre- and post-event datasets, making water classification highly reliable.

In contrast, performance declined for damage-related or small, transient classes. Vehicles (Class 7) recorded the lowest recall (0.13), with many instances misclassified as ground or buildings. This limitation is standard in LiDAR-based urban mapping, particularly when small objects are underrepresented in the training dataset or lack distinctive geometric features. Ref. [

35] reported similar challenges in detecting compact urban targets, noting that vehicles often suffer from low recall in object detection models due to occlusion and poor point density in dense urban scenes.

Damaged buildings (Class 17) achieved an F1-score of 0.58, with frequent confusion between debris and intact buildings. This disparity reflects the inherent structural ambiguity of post-disaster environments: partially collapsed roofs, fragmented walls, and debris piles often produce irregular or incomplete LiDAR returns that resemble other disturbance classes. Point cloud sparsity over rubble, combined with the absence of RGB attributes, further limits the classifier’s ability to capture fine-scale damage signatures. Class imbalance also contributes to lower performance, as damaged buildings were substantially underrepresented in the training data compared with intact structures. For instance, ref. [

36] found that accurately separating damaged buildings from debris requires high-resolution 3D segmentation and contextual modeling, particularly when structural boundaries are irregular or obscured.

Debris (Class 18) achieved a moderate F1-score of 0.77, with most misclassifications occurring into ground and damaged building classes. This pattern reflects the inherent challenge of identifying scattered material fragments, which often lack consistent shape, structure, or elevation. Ref. [

37] observed that terrain-like LiDAR returns from irregular surfaces can mimic bare earth, especially in the absence of complementary RGB or multispectral datasets.

Across these damage-related and small-object classes, two factors appear to drive the reduced performance. First, although we limited the maximum number of training samples to 2000 points per class, vehicles and partially collapsed structures occupy very small spatial extents and are represented by comparatively few independent object instances. Consequently, many local geometric configurations present in the validation area were not observed during training, a limitation consistent with prior findings on class imbalance in LiDAR-based classification workflows [

5,

6]. Second, the 3DMASC features associated with debris, damaged buildings, and surrounding ground often overlap because point densities over rubble are low, returns are noisy and irregular, and color information is unavailable. Similar challenges have been reported in disaster mapping studies where LiDAR-only datasets lack RGB or multispectral attributes, reducing feature separability between visually similar classes [

14,

37]. This combination of limited small-object samples and weak feature separation explains much of the confusion observed between vehicles, debris, and damaged buildings in the post-hurricane classification.

To evaluate the classifier’s ability to generalize beyond the training extent, we applied the model trained on Zone A to the independent post-hurricane test zone (Zone B). This validation area contains a representative mix of intact infrastructure and hurricane-induced damage, making it an effective benchmark for assessing performance on both persistent and transient classes. The classification output (

Figure 6) shows that stable features, such as roads, buildings, and water bodies, were segmented with consistently high fidelity, indicating strong transferability of the model to new spatial contexts.

3.3. Environmental Complexities and Scene-Level Ambiguities

Several classification errors in the post-hurricane dataset can be traced to scene-level complexities typical of disaster-affected environments. One of the most persistent issues was confusion between roads and ground surfaces, particularly in areas affected by mudflows, sediment deposition, and debris accumulation [

38]. These conditions altered both the geometric and radiometric properties of road surfaces, making them nearly indistinguishable from adjacent terrain. Similar blending effects have been documented in post-flood LiDAR analyses, where sediment-laden surfaces reduce the separability of engineered features from surrounding ground.

Another source of misclassification arose from inland water pooling on damaged land surfaces, which was sometimes labeled as ocean or other permanent water bodies. This occurred because temporary and permanent water bodies share similar flatness and low reflectance values, particularly in low-lying coastal zones where storm surge and rainfall-induced flooding persisted [

39]. Such ambiguities are well documented in hydrologic remote sensing, where ephemeral water can mimic the spectral and geometric signatures of stable aquatic features.

A further challenge involved vegetated rubble, zones where fallen trees and partially collapsed structures formed hybrid configurations that confused the classifier. In these cases, buildings retained partial vertical form but were entangled with vegetation, leading to frequent mislabeling between building, vegetation, and debris classes [

40]. Similar effects have been observed in landslide and wind damage mapping, where structural collapse and biomass accumulation produce mixed-class artifacts.

Temporal misalignment between LiDAR and supporting aerial imagery also introduced inconsistencies [

41]. For example, structures labeled as damaged in the LiDAR dataset may have been cleared or altered by the time imagery was acquired, leading to semantic lag in the training labels. This issue is particularly problematic in rapidly evolving disaster zones and has been noted in studies comparing LiDAR- and imagery-based change detection systems.

Furthermore, mixed-class borders, such as transition zones between debris piles, damaged buildings, and intact structures, produced classification artifacts [

42]. These edge effects are challenging to model, especially when transitional geometries are underrepresented in training data. Similar boundary-related errors have been reported in hybrid ensemble models for landslide susceptibility mapping, where overlapping features degrade classification accuracy. A visual example of these spatial ambiguities is provided in

Figure 6, which shows the classifier’s performance in the post-hurricane validation area.

In addition, the current workflow operates purely at the point level, without explicit contextual descriptors that summarize neighborhood structure or object-level connectivity, and without explicit pre–post change metrics (e.g., elevation differences between epochs) as features. These omissions likely contribute to the difficulty of distinguishing small or partially collapsed objects whose local geometry is similar to the surrounding background, a limitation noted in previous work on multi-temporal LiDAR change detection and contextual modeling for structural damage assessment [

35,

36,

42].

Although the framework achieved high accuracy for stable classes, the performance for damage-specific categories, debris (F1 = 0.77), and damaged buildings (F1 = 0.58), is below the threshold typically required for operational deployment in emergency management. These results indicate that the current approach is best suited for rapid preliminary assessments and situational awareness rather than detailed damage quantification. Further development, including integration of RGB/multispectral data, improved representation of small objects, and class balancing, is necessary before the method can be considered operationally ready.

3.4. Data Requirements for Applying the Workflow

Applying the 3DMASC–Random Forest framework requires bi-temporal airborne LiDAR datasets with sufficient point density to support multiscale geometric feature extraction, particularly for small or thin objects such as vehicles, fences, and power lines. Accurate co-registration between pre- and post-event point clouds is essential, as misalignment can distort curvature-, roughness-, and PCA-based descriptors. The datasets should include geometric and radiometric attributes such as XYZ coordinates, intensity, and return numbers. At the same time, RGB or multispectral imagery is not mandatory; it significantly improves class separability and supports accurate manual labeling. Consistent radiometric calibration and a uniform projected coordinate system are also crucial for maintaining feature stability across flight lines. The workflow performs best when applied to high-quality airborne LiDAR with minimal occlusion, and users working with lower-density data or variable acquisition geometries should expect reduced class separability and higher uncertainty. Finally, adequate computational resources are required to process large point clouds and efficiently extract more than 80 multiscale features.

3.5. Limitations

This study involved several data-related and methodological constraints that shape the performance and generalizability of the proposed workflow. A central limitation is the absence of RGB or multispectral information in the airborne LiDAR datasets. Without color-based cues, the classifier relied entirely on geometric and radiometric attributes, which are less discriminative in cluttered or structurally complex environments. This constraint contributed directly to several of the misclassification patterns observed after Hurricane Michael. Debris, damaged buildings, and bare ground often shared similar geometric signatures, especially in areas with sparse or irregular point sampling, leading to confusion between debris and ground, or between damaged and intact structures. The very low recall for vehicles similarly reflects the difficulty of distinguishing small objects whose shapes and intensities closely resemble those of surrounding surfaces when spectral information is unavailable.

Point cloud sparsity further limited the detectability of narrow or small features. Vehicles, fences, power lines, and other thin structures require dense point coverage for accurate representation, and the airborne LiDAR acquisitions did not consistently capture this detail. Class imbalance also affected model generalization were stable features dominated the landscape, whereas vehicles and partially collapsed structures were underrepresented both spatially and in the training dataset. Although capping the number of training points per class reduced the most extreme imbalance, it did not compensate for the low number of distinct objects available for training. More advanced balancing approaches, such as oversampling, cost-sensitive learning, or synthetic augmentation, were not applied here but may improve recognition of minority classes.

Several sources of uncertainty stem from the data alignment and labeling process. Temporal mismatches between LiDAR and auxiliary imagery meant that cleanup activities, temporary repairs, and natural processes such as erosion or vegetation die-off could alter the landscape between acquisitions, reducing correspondence between labels and actual post-event conditions. Transitional zones, such as areas where debris overlapped with damaged buildings or where vegetation mixed with structural collapse, were inherently ambiguous and underrepresented in the training data, leading to edge-related misclassifications. Manual labeling also introduced subjectivity, particularly in partially collapsed structures or vegetated rubble, where boundaries are difficult to delineate consistently.

Methodological constraints further shaped model performance. The workflow relies on pointwise 3DMASC descriptors and does not incorporate contextual, object-level, or explicit multi-temporal change features. This simplifies implementation but limits the ability to distinguish small or partially collapsed objects whose local geometry resembles nearby ground or intact structures. The Random Forest classifier, while robust and interpretable, lacks spatial reasoning and may be outperformed by graph-based methods or deep learning models in scenes with complex structural relationships. Additionally, the 3DMASC feature set was optimized for airborne topo-bathymetric LiDAR; its performance across other LiDAR modalities, such as UAV LiDAR, terrestrial laser scanning, or mobile mapping systems, remains untested and may require re-engineering of features.

Operational considerations present additional challenges. Extracting over 80 multiscale features is computationally intensive, and real-time or near-real-time deployment may require reduced feature sets, GPU acceleration, or model compression. The workflow also does not explicitly quantify classification uncertainty. Although probability scores were generated, they were not mapped or analyzed to identify regions of low confidence, which is critical for operational disaster response, where uncertainty-aware decision support is needed.

Finally, the workflow’s generalizability is constrained by the study area’s geographic specificity. Both training and testing were conducted in Mexico Beach, Florida, a homogeneous coastal environment with consistent terrain and building typologies. Performance in regions with different architectural patterns, vegetation structures, or topographic complexity remains untested and will require further validation, retraining, or adaptation before operational deployment in other settings.

3.6. Future Work

Future research should expand the evaluation of this framework across a broader range of disaster scenarios, geographic settings, and LiDAR acquisition conditions to assess its scalability and robustness. Testing the model on both high- and low-density point clouds, as well as datasets acquired under variable flight parameters or weather conditions, would better reflect real-world emergency deployments and reveal how reliably the workflow performs under operational constraints.

Enhancing the semantic outputs with quantitative damage metrics represents another key direction. Extending the classification framework to estimate debris volume would enable direct quantification of hurricane-generated waste, thereby linking semantic mapping to practical decision-making tasks such as debris removal planning and resource allocation.

Several methodological improvements could further strengthen discrimination of damage-related classes. Integrating multi-source data, including RGB or multispectral imagery, UAV photogrammetry, or thermal measurements, would introduce spectral cues essential for separating visually distinct but geometrically similar materials, such as debris, bare ground, and partially damaged structures. Incorporating contextual and multi-temporal change descriptors, such as object-level metrics, neighborhood connectivity, or explicit height differences between co-registered pre- and post-event point clouds, may also improve the detection of complex or mixed damage patterns.

Model development presents additional opportunities. While this study used a Random Forest classifier, more advanced ensemble methods and deep learning architectures tailored for 3D small-object detection (for example, point-based or voxel-based neural networks) may improve the recognition of vehicles and partially collapsed structures. Evaluating such models under the same bi-temporal LiDAR conditions would clarify their potential advantages and trade-offs.

Addressing class imbalance remains a significant challenge. Future work will investigate oversampling of minority classes, cost-sensitive learning, and synthetic data augmentation to improve recall for underrepresented categories such as vehicles, vegetation, and partially collapsed buildings. These techniques may reduce bias toward majority classes without requiring additional data acquisitions.

Finally, future research should examine strategies for increasing reliability across diverse operational environments. This includes mitigating the effects of temporal scene evolution, co-registration inaccuracies, and variations in LiDAR sensor characteristics. Approaches such as domain adaptation, uncertainty-aware prediction outputs, and sensor-specific feature calibration may help ensure consistent performance as the workflow is applied to heterogeneous landscapes and acquisition conditions.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrated the applicability of the 3DMASC framework, coupled with a Random Forest classifier, for automated semantic classification of pre- and post-hurricane LiDAR data in a coastal disaster context. Using Mexico Beach, Florida, as a case study for Hurricane Michael, the method achieved high classification accuracy in both stable and disaster-affected environments. Pre-hurricane classification reached an overall accuracy of 0.9711, effectively mapping stable classes such as ground, water, and buildings, while also delivering high precision and recall for power lines despite minor misclassifications. Post-hurricane classification maintained a comparable accuracy of 97%, with stable features consistently segmented at high fidelity.

While damage-specific classes, such as debris and damaged buildings, were identified with moderate success, classification performance in these categories was challenged by scene-level ambiguities, structural overlap, and limited training samples. Misclassifications were most frequent in transitional zones and for small, underrepresented features such as vehicles, reflecting known limitations of LiDAR-only datasets without RGB or multispectral attributes.

Despite these challenges, the framework proved robust, interpretable, and transferable between spatially distinct zones, highlighting its potential for rapid situational awareness and preliminary damage assessments in coastal hurricane-affected regions where high-quality LiDAR data is available. However, this workflow was validated only for Mexico Beach, Florida, and its applicability to other regions remains untested. Broader generalization to diverse landscapes, particularly those lacking high-quality LiDAR or labeled training data, will require further validation.

Future improvements should focus on integrating multi-source datasets (RGB or multispectral imagery, UAV photogrammetry, thermal data), incorporating contextual and multi-temporal features, addressing class imbalance, and developing automated tools for debris volume estimation. These enhancements are essential for improving separation between visually similar classes, detecting small objects, and supporting operational-grade disaster mapping and long-term resilience analysis.