Study on Administrative Collaborative Governance of Yellow River Water Pollution Under Sustainable Goals: An Empirical Study Based on China’s Current Legal System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Fundamental Theoretical Research on Administrative Collaborative Governance in River Basins

2.2. Research on Collaborative Governance of Water Pollution by Governments in the YRB

2.3. Research on Collaborative Governance Among Functional Departments for Water Pollution in the YRB

2.4. Literature Summary

3. Research Design

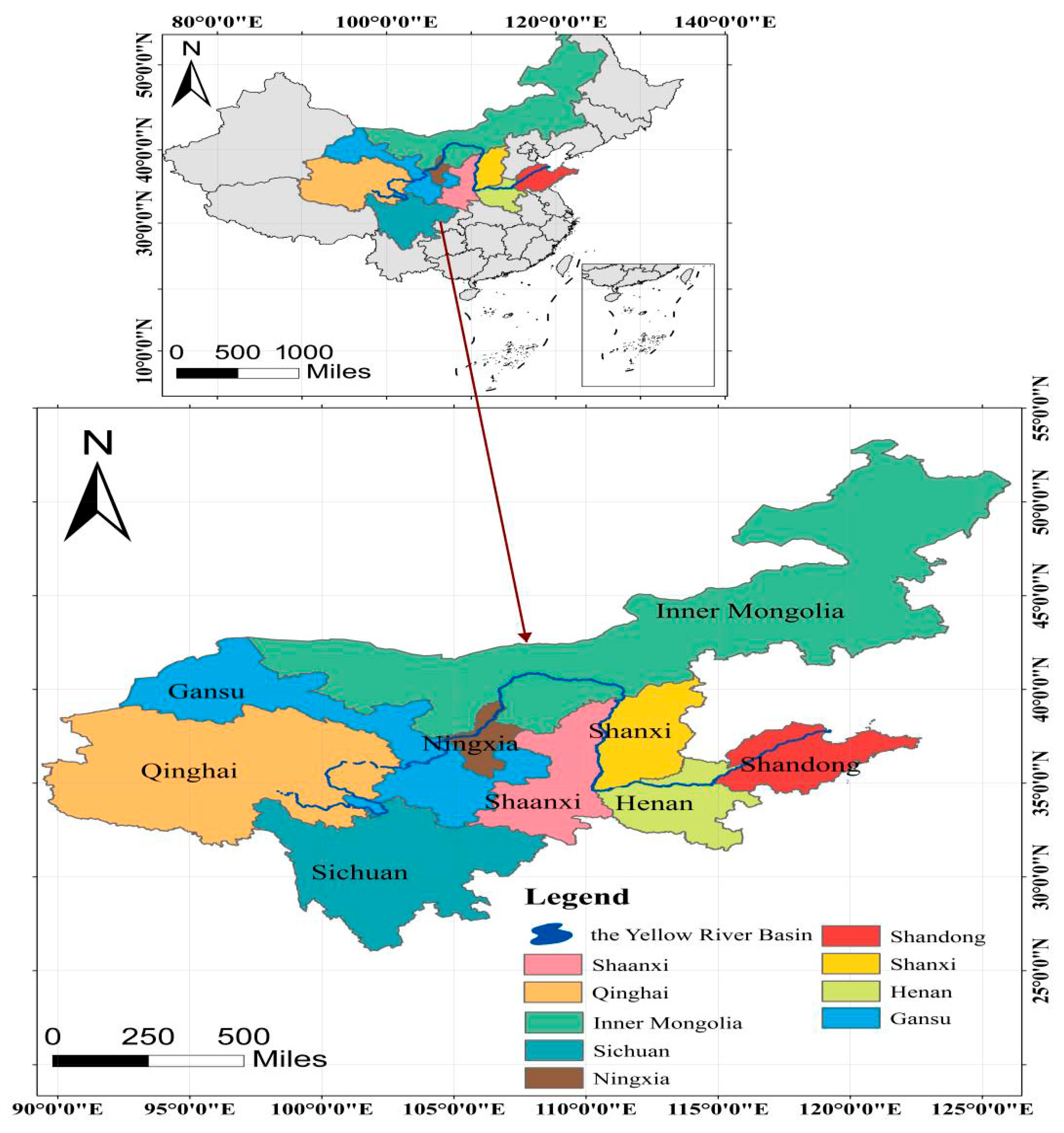

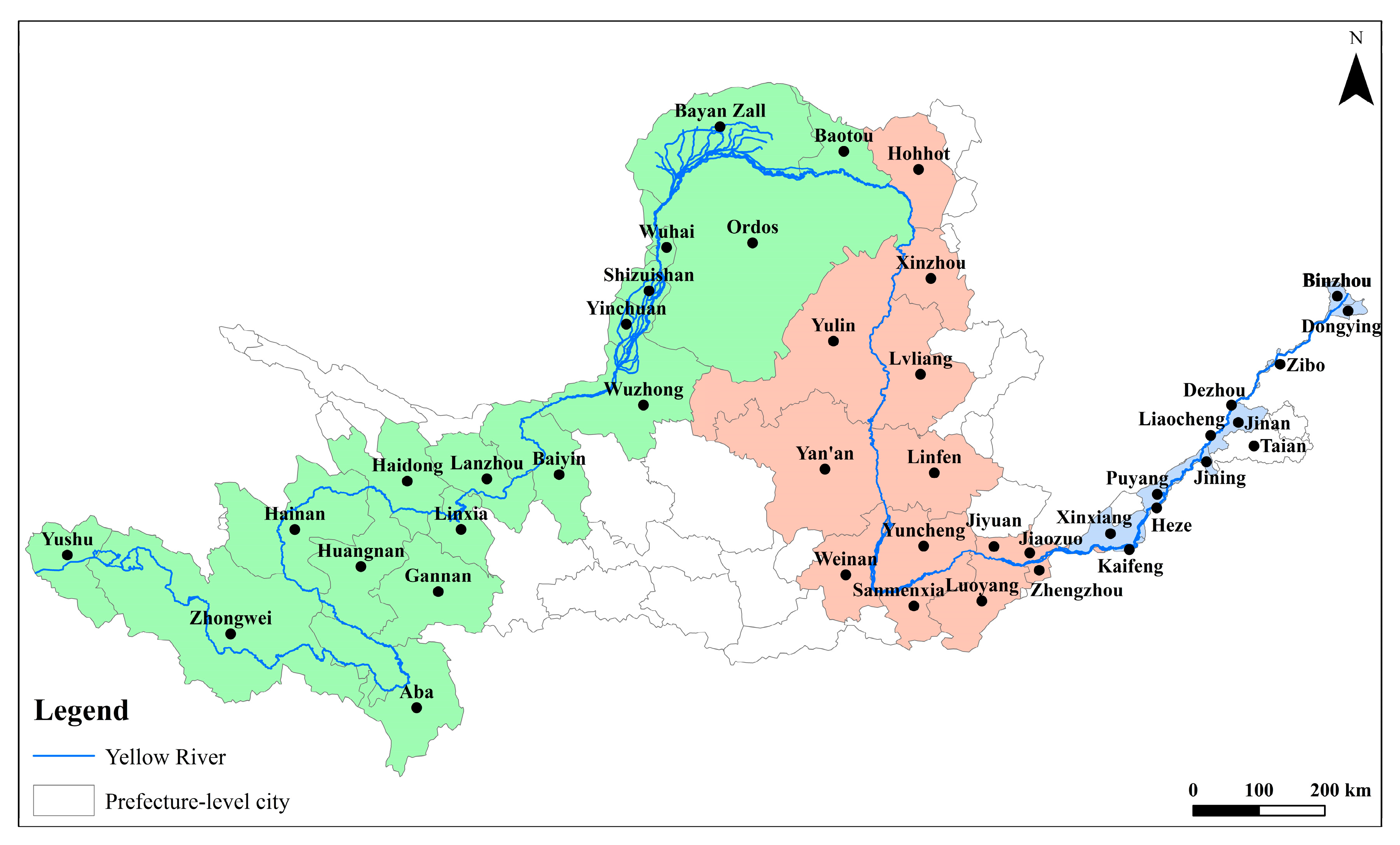

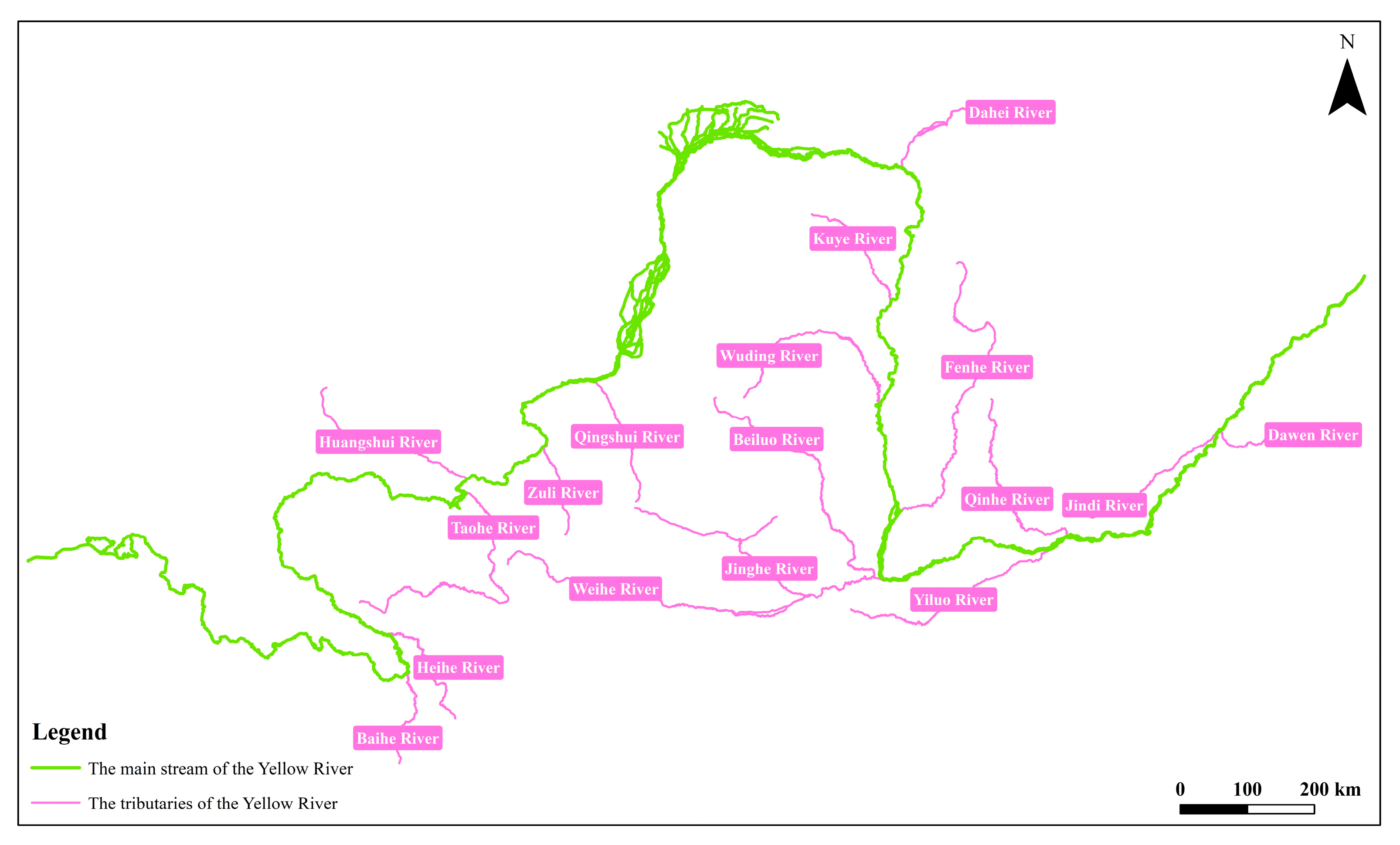

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Methodology

4. Analysis of Current Regulatory Texts

4.1. Compilation of Texts

4.2. Analysis

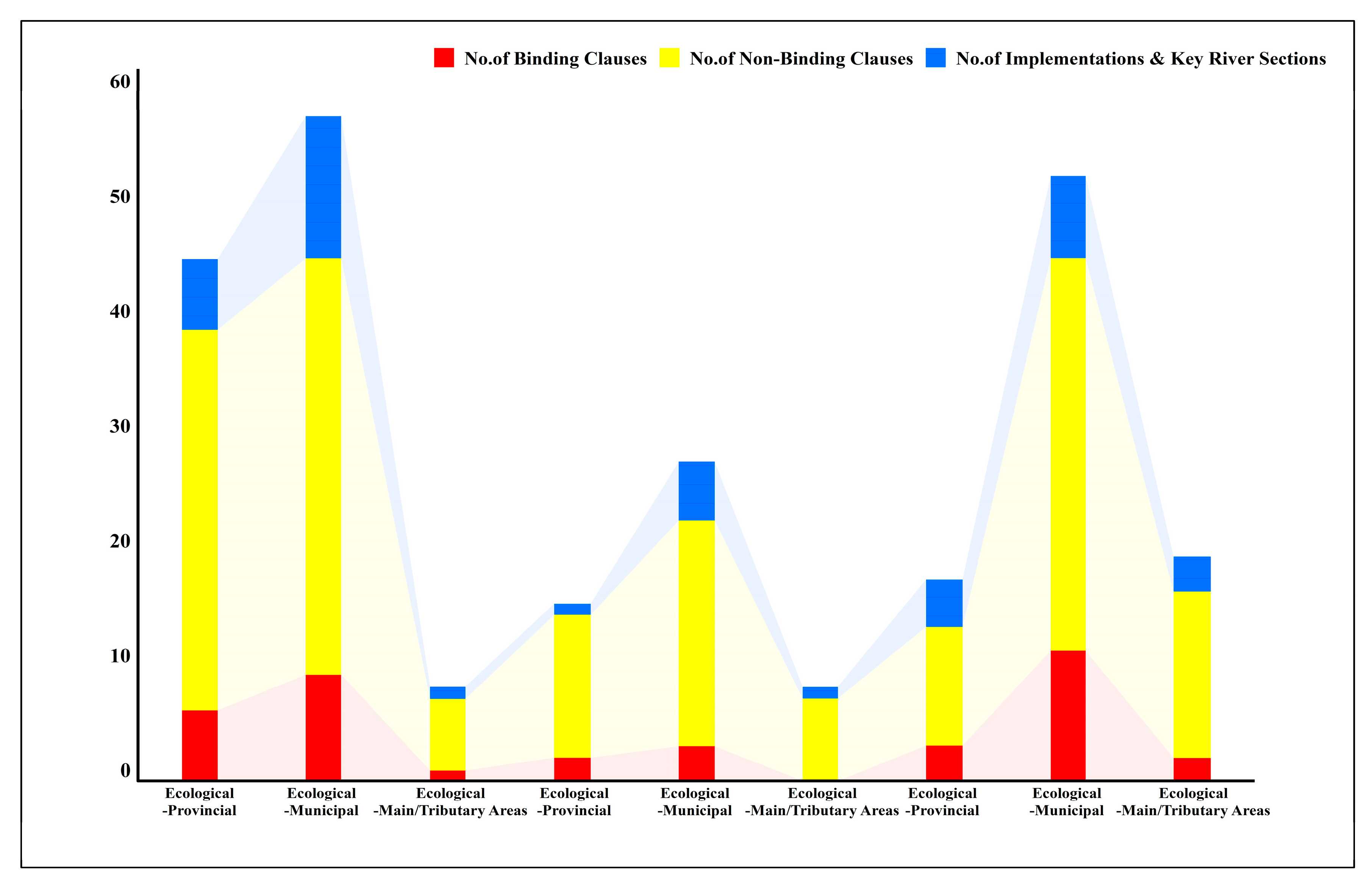

- In the ecological compensation mechanism: At the provincial level, there are 6 binding clauses versus 32 non-binding ones—non-binding clauses are 5.3 times the number of binding ones; at the municipal level, 9 binding clauses versus 35 non-binding ones (non-binding clauses are approximately 3.9 times more); and in main/tributary areas, 1 binding clause versus 6 non-binding ones (non-binding clauses are 6 times more).

- In the coordination mechanism: The number of binding clauses is even smaller. At the provincial level, only 2 binding clauses exist alongside 12 non-binding ones (non-binding clauses are 6 times more); at the municipal level, 3 binding clauses versus 19 non-binding ones (non-binding clauses are approximately 6.3 times more); and there are no binding clauses at all in main/tributary areas, with only 7 non-binding clauses.

- In the emergency response mechanism: Although the number of municipal-level binding clauses is relatively higher (11), non-binding clauses still reach 33 (approximately 3 times more than binding ones); at the provincial level, 3 binding clauses versus 10 non-binding ones (non-binding clauses are 3.3 times more); and in main/tributary areas, 2 binding clauses versus 14 non-binding ones (non-binding clauses are 7 times more).

- Only 6 out of 9 provinces, 12 out of 36 prefecture-level cities, and 1 out of 13 main/tributary areas have signed Ecological Compensation Agreements, with these primarily concentrated in the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River. The coverage and implementation intensity of the ecological compensation mechanism need to be enhanced, as it has not fully exerted its incentive and restrictive role in basin ecological protection.

- Meanwhile, the implementation of the basin coordination mechanism is equally unsatisfactory. Although all 9 provinces along the Yellow River jointly signed a document to establish a basin coordination mechanism, this only covers collaboration at the provincial level. At the local level, only 5 prefecture-level cities and 1 main/tributary area have provisions on “exploring the establishment of a basin coordination mechanism,” and these are mostly concentrated in the middle and lower reaches. Generally, the number of provisions on the basin coordination mechanism is relatively small, with unbalanced regional coverage. In the upper reaches, implementation is minimal only at the provincial level, while municipal-level and main/tributary-level implementation is absent or extremely limited, leading to insufficient coordination and linkage between regions.

- Additionally, the number of provisions on the basin emergency response mechanism is relatively limited, and implementation is also concentrated in the middle and lower reaches, with a lack of implementation in the upper reaches. This indicates that the emergency response mechanism is far from perfect: in the face of various potential sudden ecological incidents in the basin, there is a lack of a comprehensive, efficient, and widely covered emergency response system, making it difficult to carry out rapid and effective emergency disposal and fully safeguard the ecological security of the YRB.

5. Challenges

5.1. Barriers of Authority and Responsibility Among Government Departments

5.2. Interest-Based Conflicts Among Government Departments

5.3. Data Barriers Among Administrative Authorities

5.4. Lack of Mandatory Cross-Administrative Power Collaboration

5.5. Insufficient Mandatory Requirements for Cross-Administrative Emergency Response

5.6. Insufficient Long-Term Effectiveness of Cross-Administrative Collaborative Mechanisms

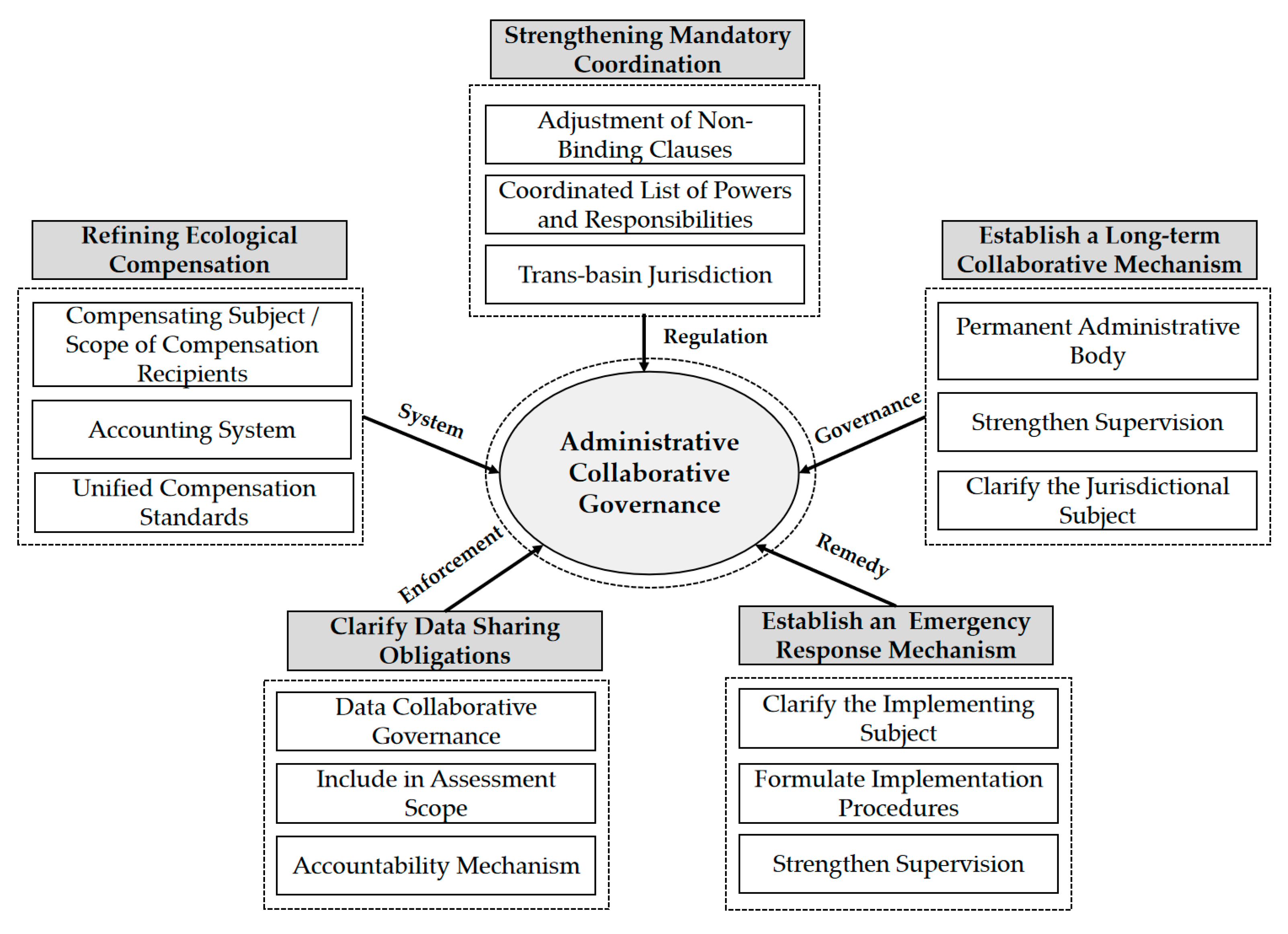

6. Response

6.1. Institutional Design for Mandatory Collaboration in the YRB

6.2. Improving and Refining Policies and Regulations on Ecological Compensation

6.3. Establishing Statutory Obligations for Data Sharing

6.4. Mandating the Establishment of a Compulsory Emergency Response Mechanism

6.5. Establishing a Long-Term Collaborative Governance Mechanism

6.6. Improve the Legislative Design Targeting the Physical Impacts of Pollutants

6.7. Strengthening Data Monitoring and Collaborative Mechanisms

7. Conclusions and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| YRPL | Yellow River Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China |

| WPCL | Law of the People’s Republic of China on Prevention and Control of Water Pollution |

| YRB | Yellow River Basin |

| CPC | Communist Party of China |

| EPL | Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China |

| WL | Water Law of the People’s Republic of China |

| WFD | Water Framework Directive |

| EU | European Union |

| ICPR | International Commission for the Protection of the Rhine |

| COD | chemical oxygen demand |

| PAHs | Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons |

References

- Ren, L.; Yi, N.; Li, Z.; Su, Z. Research on the Impact of Energy Saving and Emission Reduction Policies on Carbon Emission Efficiency of the Yellow River Basin: A Perspective of Policy Collaboration Effect. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Ni, J. Structural characteristics of river networks and their relations to basin factors in the Yangtze and Yellow River basins. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2019, 62, 1885–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Luan, S.; Gao, X.; Wang, H. Spatiotemporal Evolution, Spatial Agglomeration and Convergence of Environmental Governance in China—A Comparative Analysis Based on a Basin Perspective. Land 2024, 13, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Niu, X.; Tang, M.; Zhang, B.T.; Wang, G.; Yue, W.; Kong, X.; Zhu, J. Distribution of microplastics in surface water of the lower Yellow River near estuary. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 707, 135601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Li, W.; Liu, X.; Li, P.; Yan, L.; Liang, C. Synergistic Systems of Digitalization and Urbanization in Driving Urban Green Development: A Configurational Analysis of China’s Yellow River Basin. Systems 2025, 13, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouckaert, F.W.; Wei, Y.; Pittock, J.; Vasconcelos, V.; Ison, R. River basin governance enabling pathways for sustainable management: A comparative study between Australia, Brazil, China and France. Ambio 2022, 51, 1871–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Hagemann, S.; Liu, J. Assessment of impact of climate change on the blue and green water resources in large river basins in China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 74, 6381–6394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L. Water resource sustainable use assessment methodology and an impact factor analysis framework for SDG 6–oriented river basins: Evidence from the Yellow River basin (Shaanxi section) in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 110175–110190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendra, O.; Prasojo, E.; Fathurrahman, R.; Pilbeam, C. Vertical-horizontal actor collaboration in governance network: A systematic review. Public Organ. Rev. 2024, 24, 1233–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, D.L.; Whetten, D.A. (Eds.) Interorganizational Coordination: Theory, Research, and Implementation; Iowa State University Press: Ames, IA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, B.G. Managing horizontal government: The politics of co-ordination. Public Adm. 1998, 76, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, M.; Li, Y.; Ma, L. Impact of ecological governance policies on county ecosystem change in national key ecological functional zones: A case study of Tianzhu County, Gansu Province. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, W.R. Governing cities in the coming decade: The democratic and regional disconnects. Public Adm. Rev. 2010, 70, s137–s144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newig, J.; Fritsch, O. Environmental Governance: Participatory, Multi-Level—And Effective? Environ. Policy Gov. 2009, 19, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl-Wosti, C.; Patterson, J. Commentary: Transformative change in governance systems: A conceptual framework for analysing adaptive capacity and multi-level learning processes in resource governance regimes. Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 71, 102405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, K.; Nabatchi, T.; Balogh, S. An integrative framework for collaborative governance. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2012, 22, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Yan, F.; Sun, Y.; Yan, S. Revealing spatio-temporal differentiations of ecological supply-demand mismatch among cities using ecological Network: A case study of typical cities in the “Upstream-Midstream-Downstream” of the Yellow River Basin. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 166, 112468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenstone, M.; Hanna, R. Environmental regulations, air and water pollution, and infant mortality in India. Am. Econ. Rev. 2014, 104, 3038–3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamtik, M. Policy Coordination Challenges in Governments’ Innovation Policy—The Case of Ontario, Canada. Sci. Public Policy 2017, 44, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Jiang, H.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Hou, S.; Liu, B. The adaptation path of environmental governance in the Yellow River Basin for regional ecological improvement. Aquat. Ecol. 2024, 58, 535–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medema, W.; Adamowski, J.; Orr, C.; Wals, A.; Milot, N. Towards Sustainable Water Governance: Examining Water Governance Issues in Quebec through the Lens of Multi-Loop Social Learning. Can. Water Resour. J. 2015, 40, 373–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Han, J.; Jia, H.; Chang, X.; Guo, J.; Huang, P. Regional Economic Growth and Environmental Protection in China: The Yellow River Basin Economic Zone as an Example. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisbois, M.C.; de Loë, R.C. Power in Collaborative Approaches to Governance for Water: A Systematic Review. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2015, 29, 775–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.T.; Li, X.B.; Xue, G.W.; Gou, X.X. Digital economy, technological innovation, and carbon productivity: Empirical evidence from the Yellow River Basin. Sustain. Futures 2025, 10, 100861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiock, R.C.; Scholz, J.T. (Eds.) Self-Organizing Federalism: Collaborative Mechanisms to Mitigate Institutional Collective Action Dilemmas; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/selforganizing-federalism/27DCCF742A3A48E5E89563EA7C6EB6B0 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Chen, Y.C.; Chen, B.R.; Guo, W.; Jia, J.; Wang, Y.J. Data evaluation algorithm for compensation litigation for ecotope pollution damage in the Yellow River valley caused by industrial wastewater from the perspective of green development. Water Sci. Technol. 2023, 88, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Yang, D.; Sun, J.; Cheng, Y. The Impact of Environmental Regulations on Pollution and Carbon Reduction in the Yellow River Basin, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, J.M.; Crosby, B.C.; Stone, M.M. The design and implementation of cross-sector collaborations: Propositions from the literature. Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 66, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Wang, S.; Wu, X.; Wei, Y.; Cumming, G.S.; Qin, Y.; Li, Y. Identifying regime transitions for water governance in the Yellow River Basin, China. Water Resour. Res. 2023, 59, e2022WR033819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.F.; Yuan, Q.W.; Jiao, Y. Impact of the digital economy on low carbon sustainability: Evidence from the Yellow River Basin. Front. Energy Res. 2024, 12, 1292904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Wen, H.; Wang, S.; Wu, X.; Cumming, G.S.; Fu, B. Quantifying the effects of institutional shifts on water governance in the Yellow River Basin: A social-ecological system perspective. J. Hydrol. 2024, 629, 130638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ongley, E.D. Transjurisdictional Water Pollution Disputes and Measures of Resolution: Examples from the Yellow River Basin, China. Water Int. 2004, 29, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Wu, Y.; Sun, X.; Gu, X.; Ji, R.; Li, M. Environmental governance of Western Europe and its enlightenment to China: In context to Rhine Basin and the Yangtze River Basin. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2021, 106, 819–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Quan, Q.; Yang, S.; Dong, Y. A social-ecological coupling model for evaluating the human-water relationship in basins within the Budyko framework. J. Hydrol. 2023, 619, 129361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Xian, Q.; Cheng, S.; Chen, J. Horizontal ecological compensation policy and water pollution governance: Evidence from cross-border cooperation in China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 105, 107367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Fan, L.; Zhai, L. Evolutionary game analysis of inter-provincial diversified ecological compensation collaborative governance. Water Resour. Manag. 2023, 37, 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Cheng, S.K.; Luo, Y. Desiccation of the Yellow River and the South Water Northward Transfer Project. Water Int. 2005, 30, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Su, H.; Zhang, Y. Evolution Characteristics and Control Suggestions for Agricultural Non-Point Source Pollution in the Yellow River Basin of China. Water 2025, 17, 1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, S.W.; Liao, L.P.; Du, M.Z.; Shi, E.Y. Assessing the effect of the joint governance of transboundary pollution on water quality: Evidence from China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 989106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izaditame, F.; Siebecker, M.G.; Sparks, D.L. Sea-level-rise-induced flooding drives arsenic release from coastal sediments. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 423, 127161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, G.; Yu, C.; Yu, F. Cooperative Strategies in Transboundary Water Pollution Control: A Differential Game Approach. Water 2024, 16, 3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zou, X.; Zhang, C.; Sharifi, S. Has China’s River Chief System Improved the Quality of Water Environment? Take the Yellow River Basin as an Example. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2023, 32, 4403–4416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, D. Study on the fundraising of horizontal ecological compensation under efficiency and fairness: A case study of the Yellow River Basin in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 74862–74876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Zhou, Y.; Deng, Z. The Effectiveness of “River Chief System” Policy: An Empirical Study Based on Environmental Monitoring Samples of China. Water 2021, 13, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Field | Content | Example | Year | Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Theories of Administrative Collaborative Governance in River Basins | The paradigms of river basin governance are highly fragmented. | Hendra et al. [9] | 2024 | Indicate that collaborative governance is crucial. |

| The essence of collaborative governance is to reduce redundancy, gaps, and incoherence in the governance process. | Rogers et al. [10] | 1982 | Proposed the operational mechanism of administrative collaborative governance. | |

| “Lack of collaboration” arises when multiple actors are unwilling to break through their own jurisdictional boundaries. | Peters [11] | 1998 | Identified the fundamental cause of non-collaboration. | |

| The barriers to administrative power need to be broken down. | Zhao et al. [12] | 2023 | Propose that governance effectiveness is related to the breakthrough of administrative power. | |

| Collaborative governance requires actors to overcome limitations of authority and responsibility. | Barnes [13] | 2010 | Proposed requirements for achieving administrative collaborative governance. | |

| Collaborative water pollution governance involves multiple actors. | Newig et al. [14] | 2009 | Highlighted the necessity of collaboration among administrative actors. | |

| Collaboration occurs among cross-departmental and cross-regional government actors. | Emerson et al. [16] | 2012 | Emphasized that river basin administrative collaborative governance is centered on administrative authority and involves government actors from different regions and their internal departments. | |

| Entities exercising administrative power are the leaders in collaborative water pollution governance. | Zhang et al. [17] | 2024 | ||

| Administrative authority-centered collaborative governance mainly involves collaboration between governments and their internal departments. | Greenstone et al. [18] | 2014 | ||

| Collaboration and coordination are needed among actors from different regions and departments. | Tamtik [19] | 2017 | ||

| Research on Collaborative Governance among Governments in the YRB | The government assumes greater responsibility in the governance of the YRB | Tang et al. [20] | 2024 | Give rise to a discussion on the government’s administrative power. |

| Governments sharing administrative boundaries need to cooperate. | Medema [21] | 2015 | Emphasized the importance of cross-regional collaborative governance. | |

| Collaboration among government actors that breaks geographic constraints should be encouraged. | Feng et al. [22] | 2023 | ||

| There is an interest game between upstream and downstream governments. | Brisbois et al. [23] | 2015 | Identified the fundamental cause of conflict among administrative actors. | |

| There are cases of non-sharing of monitoring data between upstream and downstream governments. | Li et al. [24] | 2025 | Pointed out the existence of data barriers within the basin. | |

| Research on Collaborative Governance among Functional Departments in the YRB | A single administrative department cannot address complex water pollution scenarios. | Feiock et al. [25] | 2010 | Highlighted the limitations of governance by a single department. |

| Collaboration among administrative departments is essential. | Chen et al. [26] | 2023 | Stressed the importance of interdepartmental collaboration. | |

| Administrative departments face risks of authority conflicts and overlaps. | Liu et al. [27] | 2023 | Highlighted factors contributing to non-collaboration among departments. | |

| Strategies must be used to balance power differences among departments and manage conflicts effectively. | Bryson et al. [28] | 2006 | Proposed macro-level solutions for interdepartmental collaboration. | |

| Collaboration among administrative departments must break through functional barriers. | Song et al. [29] | 2023 | ||

| There are “information barriers” between departments. | Wang et al. [30] | 2024 | Pointed out that the exercise of discretion among departments exacerbates non-collaborative governance. |

| Serial | Year | Title | Main Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2019 | Speech by Xi Jinping at the Symposium on Ecological Protection and High-Quality Development of the YRB (Zhengzhou, Henan Province) | Emphasizes greater attention to systematic, holistic, and collaborative approaches to protection and governance. |

| 2 | 2020 | Speech by Xi Jinping at the Sixth Meeting of the Central Financial and Economic Affairs Commission | Focuses on the integrity of the entire basin and ecosystem, jointly promoting large-scale protection and collaborative governance. |

| 3 | 2021 | Speech by Xi Jinping at the Symposium on In-Depth Promotion of Ecological Protection and High-Quality Development of the YRB (Jinan, Shandong Province) | Stresses balancing overall and local interests, and strengthening the awareness of unified action. |

| 4 | 2024 | Speech by Xi Jinping at the Symposium on Comprehensive Promotion of Ecological Protection and High-Quality Development of the YRB (Lanzhou, Gansu Province) | Highlights the importance of coordination in Yellow River governance and promotes the construction of an integrated governance system for upstream and downstream. |

| 5 | 2022 | Report to the 20th National Congress of the CPC | Collaborative Promotion of Ecological Protection and Governance of the Yellow River |

| Serial | Year | Title | Main Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2022 | YRPL | Relevant departments of local people’s governments at or above the county level in the YRB, according to the division of responsibilities, are responsible for ecological protection and high-quality development within their administrative regions. |

| 2 | 2014 | EPL | The state establishes a cross-administrative-region mechanism for coordinated environmental pollution control. |

| 3 | 2017 | WPCL | The competent environmental protection department under the State Council, together with the water administration and other relevant departments and governments of provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities, shall establish a joint coordination mechanism for basin water environment protection of major rivers and lakes. |

| 3 | 2022 | Special Session Report on the Draft YRPL | Strengthens legal guarantees for collaborative governance in the basin. |

| 4 | 2023 | Report of the Interprovincial Joint Conference on Ecological Protection and High-Quality Development in the YRB | Deploys measures such as ecological compensation mechanisms and cross-regional collaborative governance. |

| 5 | 2020 | Outline of the Plan for Ecological Protection and High-Quality Development of the YRB | Promotes integrated governance of mountains, rivers, forests, farmlands, lakes, grasslands, and deserts. |

| 6 | 2022 | Report to the 20th National Congress of the CPC | Promotes systematic collaborative governance of ecological protection in the Yellow River. |

| 7 | 2022 | Action Plan for the Tough Battle of Yellow River Ecological Protection and Governance | Requires division of labor and collaboration among localities and departments; establishes and improves mechanisms for coordinated protection and governance of upstream–downstream, left-right banks, and main–tributary streams. |

| 8 | 2025 | Opinions on Comprehensively Advancing Ecological Protection and High-Quality Development of the YRB | Calls for the continuous improvement of the grand collaborative framework for ecological protection of the YRB. |

| 9 | 2016 | Opinions of the CPC Central Committee and the State Council on Fully Implementing the River Chief System | River chiefs at all levels are responsible for organizing, leading, managing, and protecting relevant water pollution prevention efforts, coordinating major issues, and implementing joint prevention and control for upstream–downstream and left-right bank areas that cross administrative boundaries. |

| Region | Year | Title | Main Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qinghai | 2022 | Implementation Plan for Strengthening the Supervision and Governance of Sewage Outlets into the Yellow River in Qinghai Province | Ecology environment departments at all levels are responsible for overall coordination, regular scheduling, guidance, and supervision; other departments collaborate according to the division of responsibilities. |

| Sichuan | 2022 | 14th Five-Year Plan for Ecological and Environmental Protection in Sichuan Province | Explores mechanisms for regional collaborative legislation and harmonized environmental standards, deepens cross-basin and cross-regional ecological cooperation, and promotes the establishment of regional ecological compensation mechanisms. |

| Gansu | 2023 | Gansu Province YRB Ecological Protection and High-Quality Development Regulations | Neighboring regions in the YRB should strengthen communication, cooperation, and information sharing; collaborative legislation may be carried out as needed. |

| Ningxia | 2025 | Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region Ecological and Environmental Protection Regulations | Governments at or above the county level should consult on cross-regional and cross-departmental water pollution prevention and control, strengthen resource and information sharing, and enhance joint emergency response to pollution. |

| Inner Mongolia | No relevant regulations | ||

| Shaanxi | 2022 | Action Plan for the Tough Battle of Yellow River Ecological Protection and Governance | Relevant departments should strengthen collaboration; cities (districts) along the Yellow River should take initiative, refine and allocate tasks, and improve mechanisms for advancing work to ensure effective implementation. |

| Shanxi | 2024 | Comprehensive Action Plan for Ecological and Environmental Governance in Counties along the Mainstream of the Yellow River in Shanxi Province | promote joint protection and governance of cross-boundary water bodies; establish mechanisms for information sharing, joint monitoring, and coordinated response. |

| Henan | 2025 | Notice on the Implementation Plan for Special Actions on Water Ecological Protection in the YRB in Henan Province | Water resources departments and Yellow River affairs departments at all levels in the YRB should consolidate and deepen existing work mechanisms and maintain close communication and collaboration. |

| Shandong | 2024 | Shandong Province Yellow River Protection Regulations | The provincial government should promote the establishment of a collaborative mechanism for ecological and environmental pollution prevention and control across county-level administrative regions in the YRB, organizing departments and governments for joint governance. |

| 2023 | Action Plan for the Tough Battle of Yellow River Ecological Protection and Governance in Shandong Province | Relevant departments should strengthen collaboration, and cities along the Yellow River should refine and allocate tasks and improve mechanisms for advancing work. | |

| Serial | Year | Region | Title | Main Content |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2023 | Xining | Xining Municipal Ecological and Environmental Protection Regulations | The municipal government and neighboring cities/prefectures establish cross-regional ecological protection cooperation mechanisms to achieve coordinated work and resource sharing. |

| 2 | 2021 | Linxia Hui Autonomous Prefecture | Linxia Prefecture YRB Ecological Protection and High-Quality Development Plan | Promotes collaborative governance of industrial pollution sources across regions. |

| 3 | 2010 | Lanzhou | Lanzhou Municipal Action Plan for Environmental Pollution Control | County/district governments and relevant departments should focus on concentrated remediation, strengthen coordination, form linkages, and ensure effective implementation. Departments such as industry and information technology, water resources, housing and urban-rural development, and agriculture and rural affairs collaborate according to their respective responsibilities. |

| 4 | 2023 | Zhongwei | Implementation Plan for Strengthening the Investigation, Remediation, and Supervision of Sewage Outlets into the Yellow River in Zhongwei | County/district governments are responsible for sewage outlet supervision and management. The ecological environment department exercises unified supervision and enforcement. Departments such as industry and information technology, water resources, housing and urban-rural development, and agriculture and rural affairs collaborate according to their respective responsibilities. |

| 5 | 2023 | Wuzhong | Implementation Plan for Strengthening the Investigation, Remediation, and Supervision of Sewage Outlets into the Yellow River in Wuzhong | County governments are responsible for sewage outlet supervision and management. The ecological environment department exercises unified supervision and enforcement. Departments such as industry and information technology, housing and urban-rural development, water resources, and agriculture and rural affairs collaborate according to their respective responsibilities. |

| 6 | 2022 | Yinchuan | Implementation Plan for Building a Demonstration City for Ecological Protection and High-Quality Development in the YRB (“Four Waters and Four Determinations”) | Counties/districts and departments should strengthen coordination and collaboration, establish a multi-department joint meeting system, and coordinate the resolution of major issues. |

| 7 | 2023 | Shizuishan | Plan for Strengthening the Investigation, Remediation, and Supervision of Sewage Outlets into the Yellow River | County governments are responsible for sewage outlet supervision and governance. The ecological environment department exercises unified supervision and enforcement. Departments such as water resources, industry and information technology, and housing and urban-rural development collaborate according to their respective responsibilities. |

| 8 | 2023 | Bayannur | Bayannur Wuliangsuhai Basin Ecological Protection Regulations | The municipal government should establish a comprehensive river basin coordination mechanism to coordinate major cross-regional and cross-departmental matters. |

| 9 | 2022 | Hohhot | Key Points for Promoting Ecological Protection and High-Quality Development in the YRB | Departments and divisions should collaborate according to their responsibilities and tasks to form synergy in their work. |

| 10 | 2021 | Yan’an | Key Points for Promoting Ecological Protection and High-Quality Development in the YRB | The municipal ecology and environment bureau, development and reform commission, and forestry bureau jointly carry out special actions for the control of pollution sources. |

| 11 | 2024 | Zhengzhou | Implementation Plan for the Remediation of Sewage Outlets into the YRB | Relevant units of development zones and the municipal government establish a coordination mechanism for functional departments according to the division of responsibilities, promote the formulation of work plans and specific measures, and carry out the remediation of sewage outlets into the YRB. |

| 12 | 2017 | Xinxiang | Joint Prevention and Control System for Basin Water Pollution | The municipal finance bureau, environmental protection bureau, and water resources bureau are responsible for implementing the upstream and downstream water ecological compensation system for transboundary rivers, strengthening multi-department governance of compensation funds. |

| Counties/cities/districts cooperate to establish joint inspection, handling, and supervision mechanisms for cross-boundary water pollution incidents. For cross-boundary water pollution disputes, relevant counties/cities/districts jointly coordinate and handle them according to law. | ||||

| 13 | 2022 | Tai’an | Tai’an Municipal Regulations for River and Lake Protection and Governance | The Tai’an section of the Yellow River is to be protected and managed collaboratively across regions by the municipal and county governments and their respective river and lake authorities. |

| 14 | 2023 | Jinan | Division of Tasks for the Implementation of the Action Plan for the Tough Battle of Yellow River Ecological Protection and Governance in Shandong Province | Promotes the signing of joint law enforcement agreements for ecological protection in areas along administrative boundaries with neighboring cities along the Yellow River, and improves the cross-city jurisdictional cooperation mechanism for environmental and resource-related public interest litigation. |

| 15 | 2024 | Dongying | Dongying Municipal Yellow River Delta Ecological Protection and Restoration Regulations | The municipal government should strengthen communication and collaboration with relevant cities in the areas of joint pollution control, emergency response, and joint law enforcement. |

| Serial | Tributary | Year | Title | Main Content |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Zuli River | 2023 | Baiyin Zuli River Basin Water Environment Protection Regulations | The municipal and county governments should establish a joint meeting system and improve cross-departmental and cross-regional coordination mechanisms in the basin. |

| Relevant departments should promote collaborative water pollution control according to the division of responsibilities. | ||||

| The municipal government is responsible for establishing a basin-wide coordination mechanism to address major issues. | ||||

| 2 | Wuding River | 2019 | Yulin Wuding River Basin Water Pollution Prevention and Control Regulations | The municipal government establishes a joint coordination mechanism for water pollution prevention and organizes county (city, district) governments in the basin to conduct joint water pollution prevention, emergency response, and other cross-regional pollution control efforts. |

| 3 | Kuye River | No information available. | ||

| 4 | Wei River | 2022 | Shaanxi Wei River Protection Regulations | The provincial government should establish a coordination mechanism to guide and supervise governance of the river’s upstream, downstream, main, and tributary areas, as well as both banks; coordinate major cross-regional and cross-departmental issues and implementation. |

| Communication and cooperation with neighboring provinces (regions) should be strengthened. Departments at or above county level are responsible for water pollution control in the Wei River basin. | ||||

| 2024 | Tianshui Wei River Basin Ecological Protection Regulations | The municipal and county (district) governments should strengthen communication and cooperation with adjacent cities and counties along the Wei River to coordinate major cross-regional issues. | ||

| 5 | Huangshui | 2025 | Xining Huangshui River Basin Water Ecological Environment Protection Regulations | Municipal and county (district) governments should strengthen ties with upstream, downstream, left, and right bank governments at the same level, and establish coordination mechanisms for information sharing, pollution risk assessment and warning, and joint law enforcement. |

| 6 | Dahei River | No information available. | ||

| 7 | Tao River | 2023 | Gannan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture Tao River Basin Ecological Protection Regulations | The government establishes a coordination mechanism to comprehensively guide, coordinate, and supervise major cross-regional and cross-departmental matters. |

| 8 | Qingshui River | 2025 | Wuzhong Qingshui River Basin Collaborative Protection Regulations (Draft for Comments) | When formulating regulatory documents, the municipal and county (district) governments and their departments should solicit written opinions from relevant governments and departments, and resolve issues through consultation. |

| The municipal and relevant county (district) governments should cooperate with neighboring cities/counties to establish joint prevention and control mechanisms, clarify emergency response measures and division of responsibilities, promptly report cross-border water pollution incidents, and collaborate on prevention and control. | ||||

| hongwei Qingshui River Basin Protection Regulations (Draft for Comments) | When formulating administrative regulatory documents, comprehensive plans, and other special plans, the municipal and county (district) governments and their departments should strengthen communication with relevant governments and their departments. | |||

| 9 | Fen River | 2022 | Shanxi Fen River Protection Regulations | Adjacent cities and counties (cities, districts) in the Fen River basin may sign ecological protection compensation agreements. |

| 10 | Dawen River | No information available. | ||

| 11 | Huangfuchuan | No information available. | ||

| 12 | Qin River | 2021 | Changzhi Qin River Basin Ecological Restoration and Protection Regulations | The municipal government should consult with downstream governments to establish a collaborative governance mechanism for upstream and downstream in the basin and coordinate major governance issues. |

| The municipal government should also collaborate with downstream governments to establish ecological protection compensation mechanisms. | ||||

| 2024 | Linfen Qin River Basin Ecological Protection and Restoration Regulations | The municipal government should establish coordination mechanisms with upstream and downstream governments for the development of regulations, planning, supervision, and law enforcement. | ||

| Information on cross-border river water quality and quantity monitoring should be shared. | ||||

| The municipal government should also establish environmental joint prevention and early warning mechanisms and promptly report major risks and issues. | ||||

| A collaborative emergency response mechanism should be established for sudden ecological and environmental incidents, with strengthened preparedness and joint handling. | ||||

| The municipal government should work with upstream and downstream governments to promote ecological protection compensation mechanisms. | ||||

| 2021 | Jincheng Qin River Basin Ecological Restoration and Protection Regulations | The municipal government should consult with downstream governments to establish a collaborative governance mechanism for upstream and downstream, using joint meetings, agreements, etc., to coordinate major governance issues. | ||

| The municipal government should work with upstream and downstream governments to promote ecological protection compensation mechanisms. | ||||

| The municipal government should consult with downstream governments to establish a collaborative governance mechanism. Information on cross-border river water quality and quantity monitoring should be shared. Major risks and issues should be promptly reported. | ||||

| A collaborative emergency response mechanism should be established for sudden ecological and environmental incidents, with strengthened preparedness and joint handling. | ||||

| The municipal government should work with upstream and downstream governments to promote ecological protection compensation mechanisms. | ||||

| 13 | Jindi River | Liaocheng | Preliminary research for the formulation of the Liaocheng Jingdi River Protection Regulations has begun. | |

| 14 | Yiluo River | No information available. | ||

| 15 | Bai River | 2023 | Nanyang Bai River System Water Environment Protection Regulations | Municipal and county (city), district governments should establish a comprehensive coordination mechanism to address issues such as joint law enforcement and collaborative supervision, and urge relevant departments to fulfill their duties in accordance with the law. |

| 16 | Hei River | No information available. | ||

| 17 | Beiluo River | No information available. | ||

| Object | Region | No. of Binding Clauses | No. of Non-Binding Clauses | No. of Implementations & Key River Sections |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YRB Ecological Compensation Mechanism | Provincial | 6 | 32 | 6 (Middle Reaches, Lower Reaches) |

| Municipal | 9 | 35 | 12 (Middle Reaches, Lower Reaches) | |

| Main/Tributary Areas | 1 | 6 | 1 (Middle Reaches) | |

| YRB Coordination Mechanism | Provincial | 2 | 12 | 1 (Upper Reaches, Middle Reaches, Lower Reaches) |

| Municipal | 3 | 19 | 5 (Middle Reaches, Lower Reaches) | |

| Main/Tributary Areas | 0 | 7 | 1 (Middle Reaches, Lower Reaches) | |

| YRB Emergency Response Mechanism | Provincial | 3 | 10 | 4 (Middle Reaches, Lower Reaches) |

| Municipal | 11 | 33 | 7 (Middle Reaches, Lower Reaches) | |

| Main/Tributary Areas | 2 | 14 | 3 (Middle Reaches, Lower Reaches) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hong, L.; Wan, Y.; Xu, L.; Xu, Y. Study on Administrative Collaborative Governance of Yellow River Water Pollution Under Sustainable Goals: An Empirical Study Based on China’s Current Legal System. Sustainability 2026, 18, 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010093

Hong L, Wan Y, Xu L, Xu Y. Study on Administrative Collaborative Governance of Yellow River Water Pollution Under Sustainable Goals: An Empirical Study Based on China’s Current Legal System. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):93. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010093

Chicago/Turabian StyleHong, Lewei, Yaofei Wan, Longyu Xu, and Yao Xu. 2026. "Study on Administrative Collaborative Governance of Yellow River Water Pollution Under Sustainable Goals: An Empirical Study Based on China’s Current Legal System" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010093

APA StyleHong, L., Wan, Y., Xu, L., & Xu, Y. (2026). Study on Administrative Collaborative Governance of Yellow River Water Pollution Under Sustainable Goals: An Empirical Study Based on China’s Current Legal System. Sustainability, 18(1), 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010093