Abstract

The development of New Quality Productive Forces (abbreviated as NQPFs) is crucial for agricultural modernization and agricultural sustainable growth in China. Leveraging panel data from 31 Chinese provinces (2012–2022), we employ a two-way fixed effects model to examine the influence of NQPFs on agricultural sustainable development and the underlying mechanisms. Robustness tests validate that NQPFs exert a significant positive effect on agricultural sustainable development. Agricultural technological innovation emerges as the primary channel through which NQPFs foster agricultural sustainable development. Further analysis indicates that rural economic growth positively moderates this relationship, amplifying NQPFs’ contribution to agricultural sustainability. In addition, the impact of NQPFs exhibits significant variation across regions and agricultural functional zones. Our findings suggest that to foster agricultural sustainable development, governments should prioritize cultivating NQPFs, tailor policies to regional contexts, and concurrently enhance agricultural technology and stimulate rural economic growth.

1. Introduction

Agriculture forms the foundation of a nation, and only with a solid agricultural base can it achieve lasting prosperity. The long-term stable development of agricultural production is crucial for national economic growth and social stability [1]. Resource wastage and environmental strain driven by rapid agricultural expansion have rendered traditional production models unsustainable. Coupled with external challenges—including natural disasters, climate change, and trade risks—these pressures hinder agricultural sustainability and threaten global food security [2]. At this juncture, the global agricultural sector is actively seeking pathways for transformation that are innovation-driven and conducive to sustainable development. The NQPFs are precisely the key to addressing these issues. Centered on innovation, NQPFs differ from traditional economic growth models and development trajectories. Characterized by advanced technology, high efficiency, and quality enhancement, they align with the standards of modern advanced productivity under the new development concept framework [3].

As a form of sustainable productivity, NQPFs enhance agricultural sustainability by promoting industrial upgrading and optimized resource allocation while boosting efficiency through technological innovation [4].

In this context, how can NQPFs strengthen agricultural sustainable development? What are the underlying mechanisms of this impact? And what implications do they hold for China’s agricultural modernization? Answering these questions is essential to accurately understand the role of NQPFs in fostering agricultural sustainable development and to provide valuable insights and recommendations for advancing agricultural modernization process in China and beyond.

2. Literature Review

In recent years, scholars have made remarkable progress in NQPFs research, exploring two core dimensions comprehensively. Theoretically, researchers have conducted in-depth analyses of NQPFs’ scientific connotations. Qi et al. proposed a four-dimensional framework, positing that NQPFs, distinct from traditional productive forces, are centered around four core elements: new infrastructure, new workers, new tools, and new objects of labor [5]. In terms of practical pathways, studies have examined various strategies for advancing NQPFs. Ren and Guo emphasize the critical role of deep integration between new technologies and industries, arguing in favor of modernizing and transforming established sectors while placing a strategic emphasis on developing industries and industrial clusters [6]. Chen emphasizes that advancing NQPFs in the new era requires integrated development of education, technology, talent, and industry, striving to build a mutually reinforcing and advantage-complementary development model [7]. For evaluation system construction, scholars have designed scientific frameworks to assess NQPFs’ advancement. Peng et al. developed an assessment framework founded on three core characteristics of NQPFs: high-tech, high-quality, and highly efficient [8]. Meanwhile, Lu and Guo created a different paradigm for evaluation that emphasizes three aspects: digital productivity, green productivity, and technology productivity [9]. These studies collectively contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of NQPFs, providing both theoretical foundations and practical guidelines for their development in contemporary economic contexts.

Agricultural sustainable development is an enduring, evolving research focus. The WCED first proposed “sustainable development” in 1987, defining it as development that meets present societal needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own (World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). (1987). Our common future. Oxford University Press). Building on this foundation, scholars have since established the conceptual framework for agricultural sustainable development [10,11,12]. Recent literature has focused on two key areas: constructing evaluation frameworks for agricultural sustainability and identifying its influencing factors. On the one hand, many scholars have constructed multidimensional evaluation frameworks, typically classified into three dimensions: economic, social, and environmental [13,14,15,16]. Furthermore, researchers have adopted methodologies including development indices [17], energy analysis [18], synergetic theory, and system dynamics [19] to assess agricultural sustainability, offering diverse quantitative evaluation tools. On the other hand, scholars have explored the factors influencing agricultural sustainability from multiple perspectives. Ecologically, scholars note that ongoing climate change and increased frequency of extreme weather events pose significant barriers to global agricultural sustainability [20,21,22,23]. From a social-environmental perspective, others suggest that improving agricultural sustainability-oriented legal frameworks can facilitate its progress [24]. Meanwhile, from a modern agriculture perspective, scholars argue that extensive farming practices—especially overuse of chemical fertilizers [25] and pesticides [26]—undermine agricultural sustainability. Others propose that innovative agricultural technologies can enhance sustainability—for instance, through cutting-edge applications like nanotechnology [27], the IoT, sensor technology [28] and 5G network [29]. From a bio-based agriculture perspective, scholars emphasize that enhancing agricultural ecological adaptability is vital for boosting the sustainability and stability of agricultural systems [30,31,32]. Other scholars argue that urban agriculture can be developed to promote sustainable development [33]. This comprehensive multidimensional analysis provides a robust foundation for understanding and promoting agricultural sustainable development in various contexts.

Research on the link between NQPFs and agricultural sustainable development is relatively limited. In terms of theory, Jiang and Yin propose that NQPFs can provide innovative approaches and substantial support for advancing agricultural sustainable development through technological innovation, model innovation, and market expansion strategies [34]. Li has identified critical factors influencing productivity enhancement and established relevant transformation mechanisms, offering strategic recommendations for achieving agricultural sustainable development [35]. At the empirical research level, Luo and Song have conducted empirical studies examining the effects of agricultural technology finance in empowering sustainable agriculture advancement [4].

Existing research has extensively discussed the conceptual linkage between NQPFs and agricultural development, but there is still room for deeper exploration regarding the actual mechanisms through which NQPFs may promote sustainable agricultural practices, particularly from an empirical perspective. Thus, this study uses comprehensive provincial panel data from China (2012–2022) to establish robust measurement frameworks for both NQPFs and agricultural sustainability indicators. Through this quantitative approach, we seek to unravel the underlying mechanisms and operational pathways through which NQPFs can catalyze agricultural sustainable development, ultimately offering actionable policy insights for achieving high-quality growth in the sector.

3. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

3.1. NQPFs’ Direct Effect on Agricultural Sustainable Development

Unlike the traditional mode of productivity that relies on resource input and labor quantity, NQPFs, supported by technological innovation and high-caliber workforce, serves as a key driver for high-quality economic development.

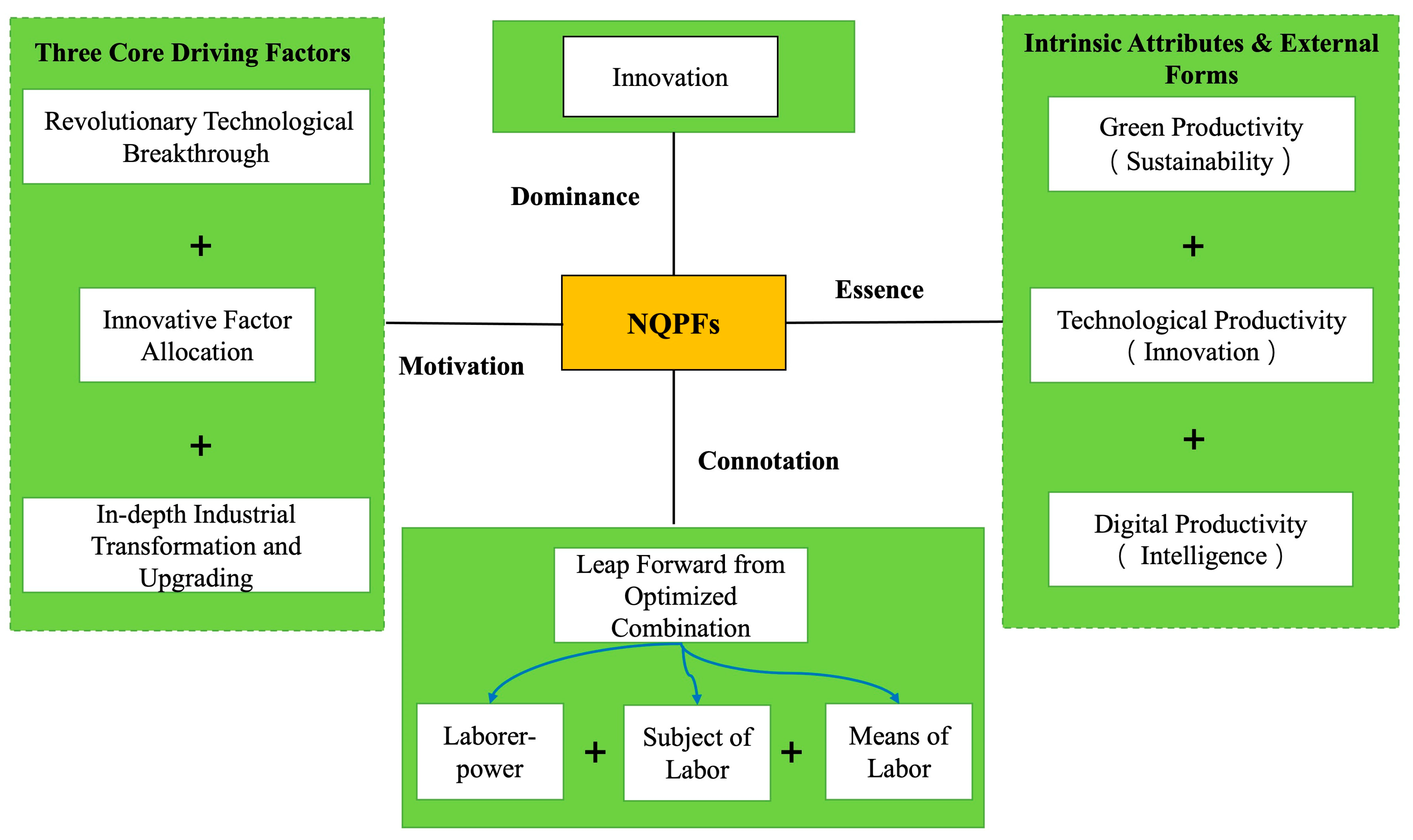

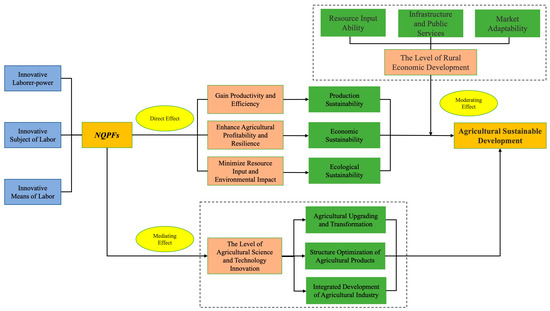

A conceptual framework is constructed to illustrate NQPFs (Figure 1). Specifically, NQPFs are driven by three synergistic factors: revolutionary technological breakthroughs, innovative allocation of production factors, and in-depth industrial transformation and upgrading. Taking innovation as its core guiding principle, NQPFs are essentially defined by the upgrading of laborer-power, means of labor, subject of labor, and the optimized recombination of these elements. Meanwhile, it can be argued that NQPFs are fully embodied and constituted by the integration of technological productivity, green productivity, and digital productivity.

Figure 1.

The framework of NQPFs.

Applying NQPFs to agricultural production can significantly advance agricultural sustainability, as NQPFs represent an advanced form of productivity. According to Marx’s labor theory of value, productivity encompasses three elements: laborer-power, subject of labor, and means of labor. What makes NQPFs “new” lies in their innovative laborer-power, means of labor, and subject of labor [36]. The innovative laborer-power are “new” in that their role has shifted from manual operators to intelligent decision-makers, with core capabilities anchored in data-driven insights and continuous learning. By operating smart tools, interpreting market dynamics, and forecasting future trends, they enable precision-driven, efficient, and market-oriented agricultural management. The innovative subject of labor is “new” in that they achieve seed-level technological independence through breakthroughs in biotechnology while leveraging digital technologies to transform land and environmental factors into digital resources [37]. This transformation expands the boundaries and potential of agricultural production beyond natural resource constraints. Likewise, the innovative means of labor are “new” as they integrate deeply with digital technologies such as cloud computing, big data, and artificial intelligence. This integration facilitates data-informed decision-making, intelligent automation, and green sustainable development in agricultural practices.

Agricultural sustainable development is generally conceptualized across three dimensions: production sustainability, economic sustainability, and ecological sustainability. The three new elements of NQPFs directly contribute to enhancing agricultural sustainable development along each of these dimensions.

3.1.1. Production Sustainability

Production sustainability refers to agriculture’s output capacity and resource-use efficiency, which ensures a stable supply of food and agricultural products. Innovative laborer-power serves as the core vehicle of human capital enhancement in the agricultural sector. Their defining attribute lies in possessing technological literacy tailored to modern farming practices: they are not only capable of precisely deploying agricultural data monitoring technologies and intelligent pest control systems to devise planting strategies and manage diseases and pests, but also proficient in leveraging professional expertise to deliver standardized, end-to-end field management. Their decision-making logic has evolved from a traditional experience-reliant model to one jointly driven by data and science. This transformation of production decision-making paradigms acts as a pivotal impetus for the simultaneous elevation of both unit yield and product quality rates. Innovative subject of labor, such as gene-edited crops and high-yield premium varieties, possess greater genetic potential and improved bioconversion efficiency, delivering higher output with equivalent inputs. Through the application of innovative means of labor, production becomes automated and precise [38], leading to substantial improvements in both resource utilization efficiency and capital efficiency.

3.1.2. Economic Sustainability

Economic sustainability refers to the profitability, market competitiveness, and risk resilience of agricultural operations. Innovative labor-power, equipped with market awareness and branding capabilities, drives the integration of primary, secondary, and tertiary industries by developing agritourism, rural e-commerce, and value-added processing of agricultural products—thereby creating brand premium and diversifying revenue streams. Innovative subject of labor, such as high-quality, nutritious, and functionally enhanced products—including high-oleic soybeans and selenium-enriched fruits—along with traceable green produce, better align with upgraded consumer demands and thus command price premiums in the market. Furthermore, innovative means of labor. Like smart equipment and digital platforms enable precise input application, saving water, fertilizer, pesticides, and other resources, thereby directly reducing production costs [39]. Meanwhile, big data analytics can forecast market trends, inform production and marketing decisions, and mitigate market risks.

3.1.3. Ecological Sustainability

Ecological sustainability refers to the environmental friendliness of agricultural production, ensuring the sustainable use of resources and the health of ecosystems. Innovative labor-power with strong ecological awareness proactively adopts environmentally friendly technologies [40] and engages in Eco-agriculture and circular agriculture practices, serving as both practitioners and promoters of green production methods. Crop varieties resistant to pests, diseases, and environmental stresses help reduce the use of pesticides and chemical fertilizers, while beneficial microbial agents—as innovative subject of labor—improve soil health, suppress soil-borne diseases, and serve as alternatives to synthetic inputs. Precision agriculture technologies, as innovative means of labor, are essential to ecological integrity. Utilizing drones, sensors, and other smart tools, they enable “using less for more” in fertilizer and pesticide application, significantly reducing agricultural non-point source pollution. These systems also improve water use efficiency and promote renewable energy adoption. Based on the above analysis, we propose the following research hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1.

NQPFs contribute to agricultural sustainable development.

Hypothesis 2.

NQPFs enhance the production sustainability of agriculture.

Hypothesis 3.

NQPFs promote the economic sustainability of agriculture.

Hypothesis 4.

NQPFs facilitate the ecological sustainability of agriculture.

3.2. Mediating Effect of Innovation in Agri-Tech

A key mediating factor in enabling agricultural sustainable development through NQPFs is agricultural technology innovation level. NQPFs, for one thing, can enhance agricultural technology innovation level. The development of technical support systems is still plagued by many problems, such as insufficient agricultural R&D funds, inefficient agricultural tech resource allocation, and a shortage of agricultural technical talents [41]. Enhancing and fostering NQPFs, emphasize a leading role of technological innovation, which prompts increased investment in core technologies, cutting-edge technologies, and fundamental agricultural research. To maximize efficiency, we must strategically allocate resources, consolidate various agricultural technologies, and foster robust collaboration to drive innovation in agricultural science and technology—ultimately paving the way for NQPFs gains. Furthermore, the development of NQPFs not only motivates the cultivation and introduction of talent in the agricultural field through the establishment of targeted recruitment mechanisms for top-tier scarce talents and the exploration of “order-oriented” training models by universities, producing more innovative, interdisciplinary, and application-oriented professionals, but also stimulates innovation among agricultural science and technology talents, guiding them to focus on key production factors and breaking through core technologies, thereby continuously improving the advancement of agricultural technological innovation. For another, increased level of agricultural technological innovation fosters agricultural sustainable development [42]. Specifically, firstly, it drives agricultural transformation and upgrading. Agricultural transformation refers to the shift from a low-efficiency, high-input, high-emission production to a high-efficiency, low-input, green, and sustainable development state. Raising the level of agricultural technological innovation encourages the creation of novel accomplishments, propels the modernization of infrastructure and machinery [43], increases agricultural mechanization and enhances both productivity and quality. Simultaneously, relying on technological innovation can guide agricultural production towards intensification and low-carbon transformation, achieving ecological benefits and promoting green and sustainable agricultural development. Secondly, it optimizes agricultural product structure. Enhancing the level of agricultural technological innovation makes it easier to address major technology bottlenecks in seed sources and reduces the disparity in autonomous innovation capacities between the domestic seed industry and developed nations, particularly for crucial agricultural products like dairy cows, corn, and soybeans. Thirdly, it fosters a comprehensive growth model for agriculture in tandem with the secondary and tertiary sectors. Constrained by mechanisms of synergic advancement and loose interest connections, the amalgamation of agricultural and livestock sectors with secondary and tertiary sectors is limited. with short agricultural production chains, low added value, a large proportion of primary agricultural products, and low levels of deep processing. Increasing agricultural science and technology innovation capabilities fosters precise alignment of innovation chains with industrial chains, breaks down barriers in technological advancements, industrial manufacturing and processing, market models, and industrial development, and propels coordinated growth of agriculture alongside secondary and tertiary sectors [41]. Agricultural sustainable development is facilitated by the natural unification of agricultural upgrading and transformation, the optimization of agricultural product structure, and the integrated growth of agricultural industries. Based on this, we propose:

Hypothesis 5.

NQPFs empower agricultural sustainable development by enhancing the level of agricultural technological innovation.

3.3. Moderating Effect of Rural Economic Development

Enhanced rural economic development boosts agricultural sustainable development through NQPFs. First, the improvement in rural economic development level indicates that rural regions have more capacity to invest in resources, which allows them to supply crucial resources, including capital, technology, and expertise, for the production and advancement of NQPFs, thus satisfying requirements of sustainable agricultural development. In addition to being dependent on agriculture, rural economic growth is also strongly tied to the expansion of non-agricultural economies. Secondly, regions with greater rural economic advancement exhibit superior infrastructure and public service amenities, facilitating the introduction of new agricultural technologies and management methods [44]. The broader coverage of communication and network services in these areas allows farmers to access new agricultural technologies more readily through information technology means, applying the new technologies brought by NQPFs to agricultural production, thus enhancing agricultural productivity and resource utilization efficiency. Lastly, the greater the percentage of agriculture in the rural economy, the slower the rural economic growth rate. Rural economic growth not only relies on agriculture but is also closely related to the development of non-agricultural economies [45]. Consequently, the rural economy’s varied growth offers agricultural producers with stronger market adaptability. By expanding industrial boundaries, agricultural producers can timely adjust planting structures and production methods based on the dynamic changes in market demand, effectively dispersing the impact of single industry risks on the agricultural economy and enhancing the stability and sustainability of agriculture. Accordingly, we propose:

Hypothesis 6.

The impact of NQPFs on agricultural sustainable development is positively moderated by the level of rural economic development.

3.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

Due to significant disparities in rural infrastructure construction, economic development levels, industrial structure, natural resource endowments, and urbanization levels across different Chinese provinces, there are wide variations in the NQPFs’ development. Consequently, regional variation may be seen in the pushing factors of NQPFs on agricultural sustainable development. Existing research indicates that 30% of counties (cities) in China have fallen into the “over-development trap,” with the eastern region being the most severely affected [46]. The eastern region boasts a relatively developed economy, yet it primarily relies on secondary and tertiary industries, with agriculture accounting for a comparatively small proportion of its economic structure [47], and is highly industrialized and urbanized. From a resource allocation perspective, the agricultural economy may have been marginalized, with more resources flowing into industrial and service sectors. The introduction of NQPFs might exacerbate resource shortages in the agricultural economy, leading to adverse effects. Moreover, despite its economic prosperity, the eastern region faces challenges such as scarce land resources, water scarcity, and significant environmental pressures. The implementation of NQPFs could require considerable resource inputs, potentially leading to crowding-out effects in the agricultural economy. Conversely, the central and western areas exhibit a higher agricultural presence, with NQPFs developing late but rapidly. Leveraging the late-mover advantage, NQPFs may more effectively promote agricultural sustainable development in these areas. Furthermore, strategic initiatives like the “The Growth of Central China” and “Western Region-Wide Expansion” have effectively stimulated economic, technological, and talent development in the central and western areas [48]. Additionally, policy backing in these areas provides strong momentum for NQPFs to empower agricultural sustainable development.

Because of the significant variations in resource availability and the functional positioning and characteristics of different agricultural functional zones in China, there is noticeable variation in how NQPFs affect the agricultural sustainable development. Main grain-producing areas, typically rich in resources with strong production capacities, serve as crucial zones for national food security. These areas benefit from fertile soil, ample water resources, and favorable climatic conditions, suitable for large-scale, high-efficiency agricultural production. The introduction of NQPFs, such as digital agriculture, intelligent equipment, and biotechnology, can further enhance production efficiency and resource utilization in these areas, advancing sustainable growth in agriculture. Grain balance zones share advantages with both main producing and consuming areas, and their agricultural development levels are relatively balanced, covering production, processing, and sales comprehensively [49]. Consequently, the NQPFs in these zones can positively affect agricultural sustainable development. Meanwhile, main grain-consuming areas, characterized by their economic prosperity and high urbanization levels, have promoted the non-agricultural transfer of rural labor, significantly reducing the enthusiasm for grain cultivation [50]. NQPFs may not be able to effectively support agricultural sustainable development in these regions due to their limited land and water resources and reliance on outside agricultural products. We put out the following research hypotheses in light of these facts:

Hypothesis 7.

Regional heterogeneity is demonstrated by the empowerment of NQPFs on agricultural sustainable development.

Hypothesis 8.

Functional area heterogeneity is demonstrated by the empowerment of NQPFs on agricultural sustainable development.

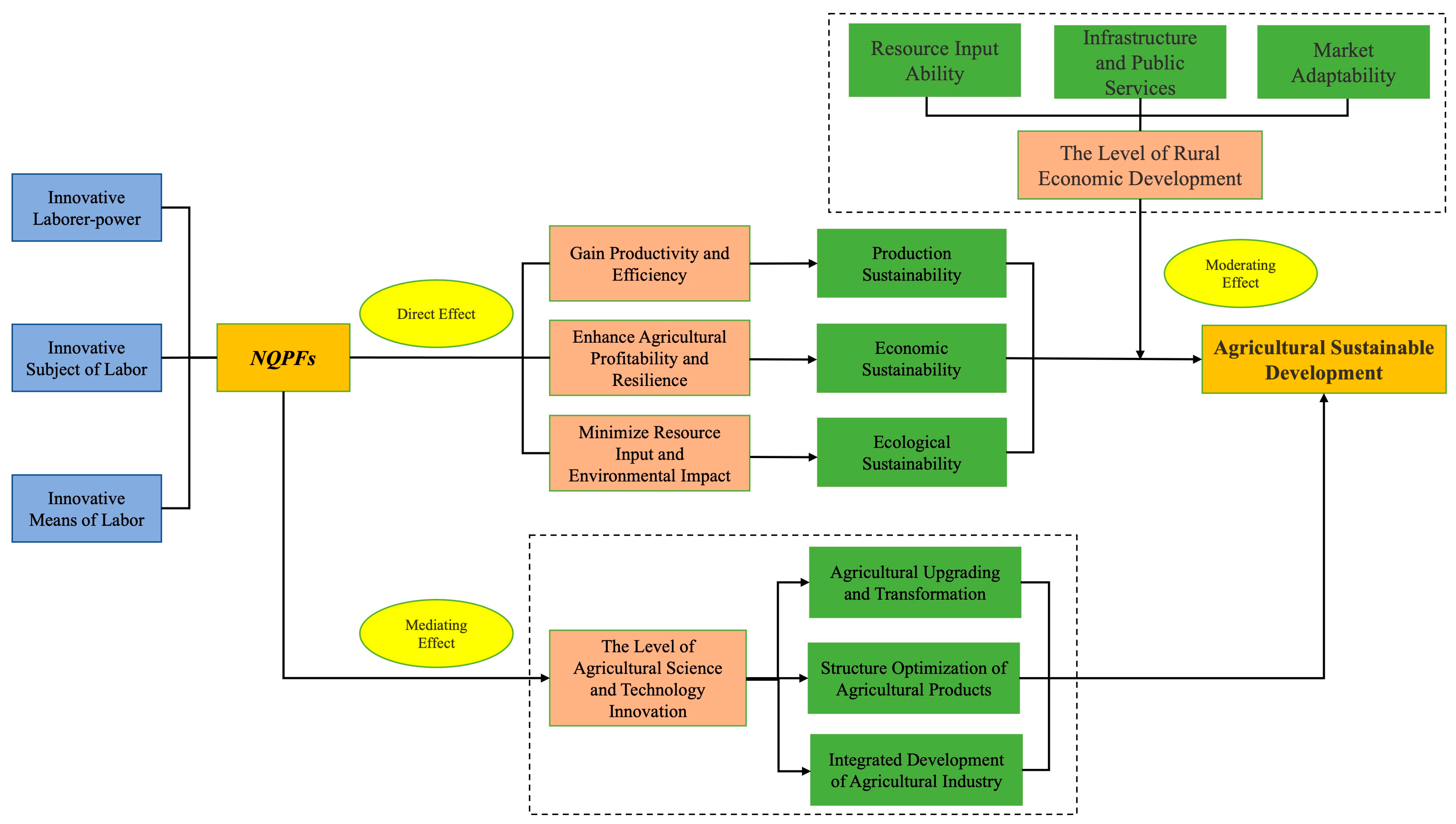

In conclusion, in order to more clearly illustrate the path mechanism and driving path of NQPFs enabling agricultural sustainable development, we draw the following figure to present the theoretical path of NQPFs empowering agricultural sustainable development (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mechanism and Pathway of NQPFs Empowering Agricultural Sustainable Development.

4. Research Design

4.1. Model Specification

4.1.1. Benchmark Regression Model

To examine NQPFs’ impact on agricultural sustainability, we conduct F-tests and Hausman tests on panel data from 31 Chinese provinces. Test results consistently show that the fixed-effects model is the most suitable for the sample data across different regression specifications. Consequently, the following benchmark regression model is established:

ASDit = α0 + α1NQPFsit + α2Controlsit + σi + μt + εit

In Equation (1), variables are defined as follows: the dependent variable (ASDit) denotes the agricultural sustainability index of province i in year t. Meanwhile, NQPFsit serves as the explanatory variable, representing the NQPFs index of province i in year t. Controlsit is a vector of control factors influencing agricultural sustainability. σi and μt indicate province-specific and time-specific fixed effects, respectively, capturing unobserved heterogeneity across regions and time periods. εit represents the stochastic error term, capturing unobserved random factors influencing the model.

4.1.2. Mediation Effect Model

Building upon the theoretical framework established earlier, this study examines the transmission mechanism of NQPFs on agricultural sustainable development, with agricultural technological innovation as the mediating variable. we adopt Jiang’s two-step mediation analysis method to construct the following mediation model [51]:

TECit = β0 + β1NQPFsit + β2Controlsit + σi + μt + εit

In Model (2), the degree of agricultural technical innovation is represented by TECit, while other variables consistent with Model (1).

4.1.3. Moderating Effect Model

Building upon the preceding theoretical analysis, we systematically examine the intrinsic relationship between NQPFs and agricultural sustainable development. To elucidate this mechanism, we introduce rural economic development level as a moderating variable and incorporate its interaction term into the baseline regression model. Due to potential dimensional discrepancies between NQPFs (the core explanatory variable) and GDP, directly constructing their interaction term may lead to multicollinearity, reducing the reliability of estimation results. Thus, we first conduct Z-score standardization on NQPFs and GDP separately, and then constructs the interaction term Z_NQPFs*Z_GDP using the standardized variables. This approach enables us to empirically test the moderating effect of rural economic development in the process whereby NQPFs enhance agricultural sustainable development. Constructed model is specified as follows:

ECOit = γ0 + γ1Z_NPQFsit + γ2Z_GDPit + γ3Z_NQPFsit*Z_GDPit + γ3Controlsit + σi + μtεit

In Model (3), Z_NQPFs*Z_GDP denotes the standardized interaction term between NQPFs and rural economic development, with other variables consistent with those in Model (1).

4.2. Data Sources and Variable Descriptions

4.2.1. Data Sources

This study uses balanced panel data from 31 Chinese provinces (excluding Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan) covering the period 2012–2022. The data are primarily sourced from the National Bureau of Statistics of China and several authoritative yearbooks, including the China Environmental Statistical Yearbook, China Rural Statistical Yearbook, China Statistical Yearbook, China Science and Technology Statistical Yearbook, and China Industrial Statistical Yearbook. Linear interpolation is used to supplement missing data, ensuring data completeness.

4.2.2. Variable Selection and Descriptions

Dependent variable: Agricultural Sustainable Development. Existing research indicates that sustainable agriculture requires the integration of production sustainability, economic sustainability, and ecological sustainability [52]. Based on this, combined with the principle of data availability, we select a multi-dimensional set of indicators to comprehensively evaluate the level of agricultural sustainable development across China’s provinces. The entropy method is used to determine indicator weights, objectively quantifying the comprehensive agricultural sustainability index. The selection basis and definitions of indicators are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Agricultural Sustainable Development Index System.

Independent variable: NQPFs. This paper builds an indicator system to evaluate NQPFs via three perspectives: digital productivity, green productivity, and technological productivity. There are 15 tertiary indicators and 5 secondary indicators in the system. The level of NQPFs in each province is measured using the entropy method. The selection basis and definitions of indicators are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

NQPFs evaluation index system.

Controlled Variables. Based on the studies by Zhou and Yin [70] and Song et al. [71], and considering the well-established theoretical and empirical links between these variables and agricultural sustainability (including socioeconomic drivers, policy interventions, external factors, and environmental shocks) as well as data availability, we select six controlled variables: the degree of natural disasters (DIS), the level of government agricultural support (SAG), urban-rural income distribution (UID), urbanization rate (CR), regional openness (RO), and the degree of industrialization (DOI).

Mechanism Variable. According to existing research, agricultural R&D spending and agricultural science and technology staff are two important variables that are essential for examining agricultural technological innovation [72]. In order to create the agricultural technical innovation level index, or TEC, we combine these two metrics—agricultural R&D spending and agricultural science and technology staff—and use the entropy technique. Specifically, agricultural R&D expenditure is adjusted by multiplying it by the ratio of agricultural output value to total output value. Similarly, the number of agricultural science and technology personnel is adjusted using the same ratio.

Moderator variable. Rural economic development serves as the moderating variable. Following Huang [73], it is measured by rural per capita GDP. Table 3 presents detailed definitions for all variables.

Table 3.

Variable definition and description.

5. Empirical Results Analysis

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 4 presents the descriptive statistics of all variables. NQPFs have a mean of 0.199, a standard deviation of 0.181, ranging from 0.03 to 0.88. This indicates a significant disparity in NQPFs advancement across regions, with a generally low overall level and substantial variations. The Agricultural Sustainable Development indicator shows an average of 0.457, with a standard deviation of 0.063, ranging from a low of 0.318 to a high of 0.7. While there is significant room for improvement, its regional variations are less pronounced than those of NQPFs. The agricultural technological innovation level has a maximum of 1.001, a minimum of 0.013, and a standard deviation of 0.2, indicating substantial regional differences in China’s agricultural technological innovation. Most regions have significant potential to enhance agricultural technological innovation. Other variables are generally consistent with previous studies, further confirming their universality and importance in the agricultural sustainable development.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics Results.

5.2. Baseline Regression

To examine whether NQPFs directly promote agricultural sustainability, we take NQPFs as the core explanatory variable and agricultural sustainability as the dependent variable. We use Model (1) for panel regression and adopt a stepwise approach by gradually incorporating control variables. Column (1) of Table 5 presents the regression results without control variables, indicating that NQPFs significantly promote agricultural sustainability, with a coefficient of 0.068. Column (2) incorporates natural disasters severity and government agricultural support as control variables. building on Column (2), Column (3) further incorporates urban-rural income disparity and the rate of urbanization into the model. Column (4) incorporates all control variables. After including all the control variables, regression coefficient of the NQPFs is significant at the 1% level, confirming that NQPFs significantly promote agricultural sustainable development. Hypothesis 1 is thus confirmed.

Table 5.

The baseline regression results.

It is worth noting from Table 5 that both the SAG and DOI variables exhibit a negative impact on agricultural sustainable development. The underlying reasons may be as follows. First, a higher proportion of agricultural expenditure in the total fiscal budget often reflects a relatively small overall fiscal capacity and an inflexible spending structure in the region, which may rely excessively on agricultural subsidies. For farmers, excessive price support or protective procurement prices can lead to over-reliance on such policies, reducing their incentive to adopt sustainable practices and thereby hindering the transition to green agricultural development. Moreover, this negative impact may also arise from the inefficient allocation of government-funded resources or the traditional subsidy approach, which tends to focus on output rather than green technologies. Second, a wider urban-rural income gap accelerates the outflow of young and able-bodied laborers from rural areas, leaving behind an aging population and extensive farming practices. This exacerbates the shortage of skilled labor, discourages the adoption of green technologies, and leads to insufficient long-term investment, collectively contributing to the decline in agricultural sustainability.

In addition, we further decomposed agricultural sustainable development into three dimensions: production sustainability (abbreviated as ProdS), economic sustainability (abbreviated as EnS)and ecological sustainability (abbreviated as EcS), and conducted regression analysis, respectively. The results are presented in Columns (5), (6) and (7) of Table 5. The corresponding regression coefficients for the three dimensions are 0.230, 0.400 and 0.071, all of which are significant at the 1% statistical level. Thus, Hypotheses 2, 3 and 4 are verified.

5.3. Robustness Tests

We validate the baseline model and regression outcomes using three robustness methods: substituting the dependent variable, excluding centrally administered cities, and winsorization.

5.3.1. Replacing the Dependent Variable

Relying solely on the comprehensive evaluation index to measure agricultural sustainable development may be insufficient. We attempt to measure agricultural sustainable development from additional dimensions. Based on study of Guo et al. [74]. The “quality efficiency” indicator is selected to assess agricultural sustainable development, and regression is re-performed accordingly. Further confirming the strength of the earlier findings, the results, as depicted in Column (1) of Table 6, reveal that upon swapping the dependent variable, NQPFs coefficient stands at 0.302, and it is statistically noteworthy with a 1% significance level.

Table 6.

Robustness test results.

5.3.2. Excluding Municipalities Directly Under the Central Government

Urban regions directly administered by the central government often significantly differ in economics, culture, and governance from standard provinces. These differences may increase sample heterogeneity, affecting the accuracy and reliability of statistical results. Consequently, after removing these municipalities, we re-run the model to test its robustness. The regression outcomes, shown in Column (2) of Table 6, reaffirm the reliability of the baseline data. Specifically, the coefficient for NQPFs stands at 0.122 and is highly significant, with a p-value well below 1%.

5.3.3. Winsorization of Samples

After applying winsorization at the 1% threshold to all variable values to mitigate the influence of outliers, the regression analysis was re-run. The robustness of the earlier results is confirmed by these updated findings, presented in Column (3) of Table 6. Notably, the coefficient for NQPFs post-winsorization stands at 0.057 and retains statistical significance at the 1% level.

5.4. Endogeneity Test

5.4.1. Instrumental Variables (IV) Approach

Both NQPFs and agricultural sustainable development indicators in this study are comprehensive indices calculated using the entropy method. Linear interpolation was used to supplement missing data, which may cause deviations from real values and potential endogeneity problems. To mitigate these issues, we use a two-way fixed effects model with six controls to mitigate omitted variable bias: natural disasters, degree of openness, government support for agriculture, urbanization rate, industrialization level, and urban-rural income distribution. For more complex endogeneity issues (e.g., reverse causality, measurement errors), we further use the first lag of NQPFs as an instrumental variable (IV), whose validity is supported by three key rationales. First, lagged NQPFs are highly correlated with current NQPFs. Second, lagged NQPFs are exogenous to current model disturbances and not affected by contemporaneous unobserved factors. Third, the agricultural production system exhibits significant adjustment lag: the long cycles of agricultural technology promotion and facility construction mean that prior productivity inputs have a sustained impact on current outcomes. Meanwhile, current short-term natural or policy shocks cannot retroactively alter lagged NQPF levels, a unique agricultural attribute that strengthens the IV’s applicability.

The IV test results (Column 1 of Table 7) show that the coefficient of NQPFs is 0.071, confirming the robustness of previous findings.

Table 7.

Endogeneity test results.

5.4.2. System GMM

Building on the static IV approach to address endogeneity, and considering the inherent time-lag effects of agricultural development, potential bidirectional causality, and omitted variable bias, this study further includes the one-period lagged term of agricultural sustainability (L.ASD) as an explanatory variable. The system GMM method is employed for empirical testing, with detailed results presented in Column (2) of Table 7. The findings indicate that, even after controlling for endogeneity, NQPFs continue to exhibit a significant promoting effect on agricultural sustainable development, with a coefficient of 0.045. This suggests that endogeneity does not substantially undermine the reliability of the empirical results.

5.5. Mechanism Test

This study adopts a two-step approach to test the mediating effects, drawing on the methodological framework put forward by Jiang [51]. Table 8 reports the mediating effect test results. NQPFs significantly boost agricultural sustainable development, as shown in Column (1). Column (2) shows that NQPFs significantly enhance agricultural technological innovation. Farmer earnings growth is a key indicator of sustainable agriculture, and existing research shows that advances in agricultural technological innovation increases farmers’ incomes [75]. Furthermore, empirical studies have confirmed that agricultural science and technology innovation can effectively promote sustainable growth in the agricultural economy [76]. These results indicate that enhancing agricultural innovation is key to promoting agricultural sustainable development. Through accelerating the transformation of scientific achievements and enhancing independent innovation capabilities, it significantly fosters agricultural sustainable development. Consequently, the pathway through which NQPFs promote agricultural sustainable development by elevating agricultural science and technology innovation level has been clearly established, thereby validating Hypothesis 5.

Table 8.

Results of the mediation effect test.

6. Extended Analysis

6.1. Moderating Effect Analysis

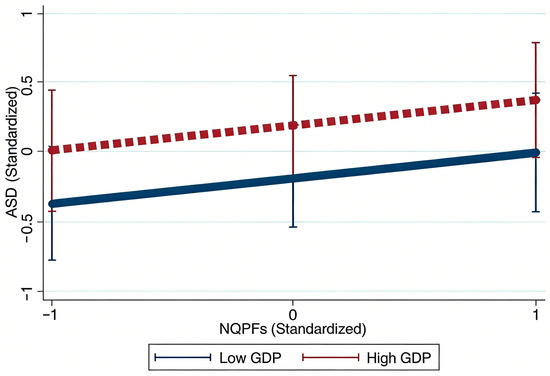

To validate Hypothesis 6, we construct an interaction term between NQPFs and rural economic development to examine its moderating role in the process of NQPFs empowering agricultural sustainable development. which was previously proposed. As shown in Table 9, after incorporating the interaction term, the regression results remain statistically significant. Rural economic development positively moderates the relationship between NQPFs and agricultural sustainability, with the interaction term’s coefficient of 0.005.

Table 9.

The results of the moderation effect test.

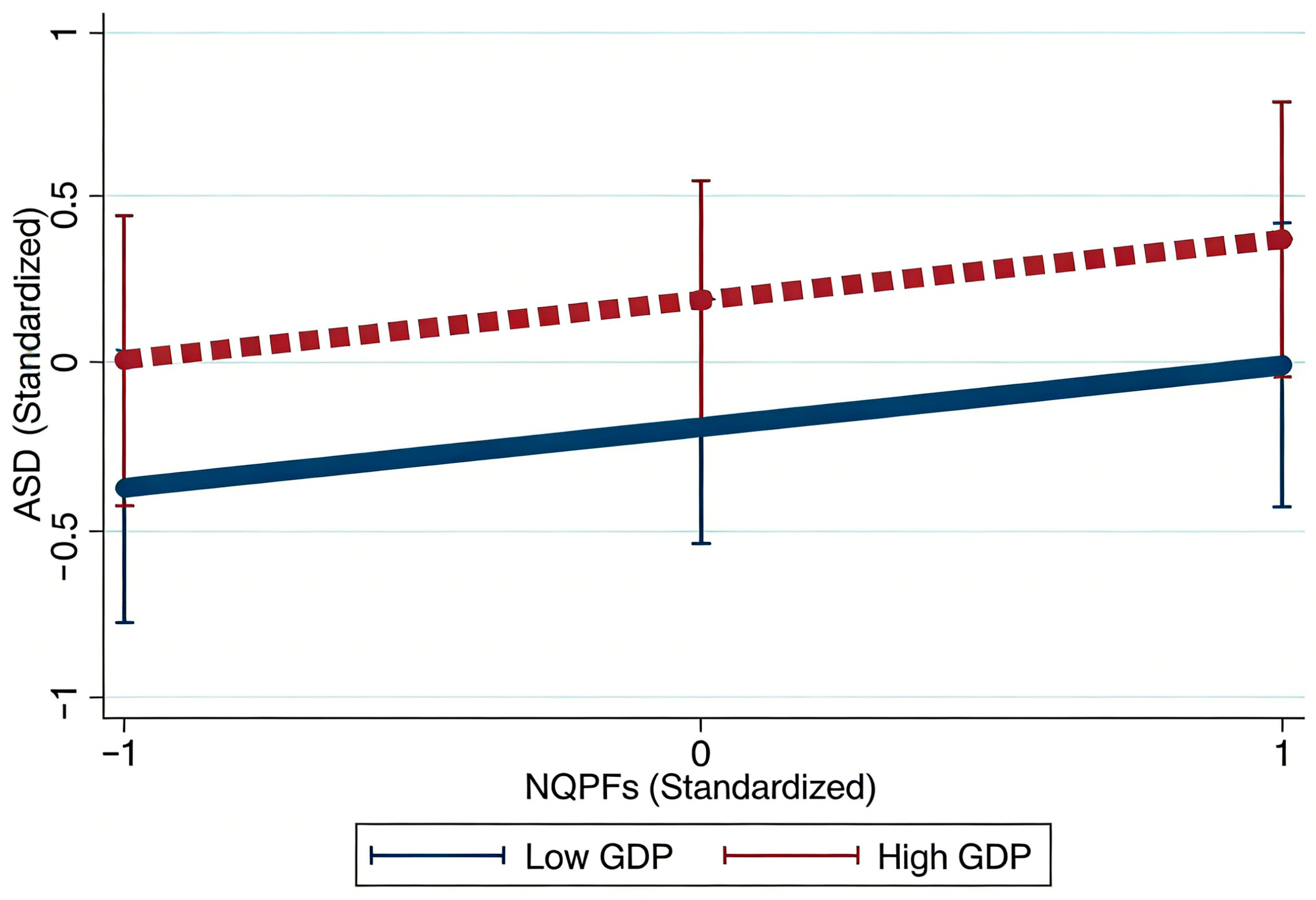

Further insights can be derived from the marginal effect visualization in Figure 3: for the low-GDP group (blue line), the marginal effect of NQPFs on agricultural sustainable development (ASD) is negative and statistically significant (error bars do not cross the zero line), indicating that an increase in NQPFs significantly inhibits agricultural sustainability when GDP is relatively low. In contrast, for the high-GDP group (red line), the marginal effect of NQPFs on agricultural sustainable development (ASD) becomes positive and statistically significant (error bars also do not cross the zero line), meaning that an increase in NQPFs significantly promotes agricultural sustainability when GDP is relatively high. Hypothesis 6 is thus verified.

Figure 3.

The Moderating Effect of GDP on the NQPFs–ASD Relationship. Notes: The blue line (with blue error bars) represents the marginal effect of NQPFs on ASD for the low-GDP group; the red dashed line (with red error bars) represents the marginal effect for the high-GDP group.

6.2. Heterogeneity Test and Empirical Results

To validate Hypotheses 7 and 8 presented earlier, this study conducts empirical testing through two dimensions: regional heterogeneity and agricultural functional zone heterogeneity.

6.2.1. Regional Heterogeneity

China’s vast territory is divided into 31 provincial-level administrative units. In order to accurately assess the diverse socioeconomic conditions across these regions and provide a factual basis for the Central Committee of the Communist Party and the State Council to formulate targeted regional policies, the country is categorized into three major areas—eastern, central, and western—based on factors such as natural geography, economic foundation, development status, and degree of openness. The eastern region, which includes 11 provinces such as Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Guangdong, is the most economically developed and highly open. The central region—including six provinces (e.g., Shanxi, Henan, Hubei)—acts as a national transportation hub and key grain production base, connecting eastern and western China. The western region, covering the largest area with abundant natural resources, still lags behind in economic development; it consists of 14 provinces and autonomous regions such as Sichuan, Guizhou, and Yunnan. We further conduct regression analysis to explore the regional heterogeneity in the impact of NQPFs on agricultural sustainable development.

The regional analysis of heterogeneity uncovers notable geographic variations in how NQPFs influence agricultural sustainable development, as illustrated in Table 10. In the eastern region, NQPFs fail to have a favorable effect on agricultural sustainable development, as indicated by a coefficient of −0.025. In contrast, the central and western regions exhibit a strong positive impact of NQPFs, with coefficients of 0.196 (central) and 0.155 (western), both significant at the 1% level. These results provide empirical support for Hypothesis 7. An examination of the underlying reasons reveals a crowding-out effect of NQPFs on agricultural sustainable development in the eastern region. This is closely associated with the “resource curse” concept, introduced by Auty, which refers to the phenomenon where abundant natural resources in certain countries or regions fail to drive economic growth and instead hinder development [77]. Domestic scholars have also confirmed the applicability of the “resource curse” hypothesis in China [78,79].

Table 10.

Regional heterogeneity test results.

Specifically, that is, given the robust development of secondary and tertiary industries in the east, new technologies and factors of production tend to be absorbed more readily by non-agricultural sectors offering higher returns. Consequently, traditional agriculture is crowded out, reducing the efficiency of NQPFs in promoting agricultural sustainability and thus exerting a slight inhibitory effect. In contrast, the central and western regions exhibit a marginal enhancement effect of NQPFs on agricultural sustainable development. In the central and western regions—where agriculture still accounts for a relatively large share and factor endowments are weak—the net inflow of technologies, capital, talent, data, and other factors driven by NQPFs can quickly address traditional shortcomings [80], directly promoting agricultural sustainability.

6.2.2. Agricultural Functional Zone Heterogeneity

Based on the characteristics of agricultural functional zones, this study classifies the sample into three types: major grain-producing areas (13 regions, 41.94%), grain-balanced areas (11 regions, 35.48%), and grain-deficit areas (7 regions, 22.58%). In terms of regional composition, the major production zones cover the largest area, followed by grain-balanced areas, while grain-deficit areas constitute the smallest proportion. As detailed in Table 11, the results show that in major grain-producing areas, the coefficient of NQPFs is 0.183, significant at the 1% confidence level. In grain-balanced areas, the coefficient is 0.094, also significant at the 1% level. This suggests that these areas effectively utilize NQPFs to foster agricultural sustainable development. However, in grain-deficit areas, the coefficient of −0.087 is statistically insignificant at the 1% level, indicating that NQPFs do not effectively promote agricultural sustainability in these regions. These results provide empirical support for Hypothesis 8.

Table 11.

Results of agricultural functional area heterogeneity.

The disparity arises from the following factors: major grain-producing and balanced zones possess superior resource endowments and benefit from concentrated policy support, enabling the large-scale application of NQPFs such as agricultural drones and big data platforms. These technologies significantly enhance efficiency, reduce resource and environmental costs, and comprehensively promote sustainable agricultural development. In contrast, grain-deficit areas are characterized by advanced economies and high urbanization levels, where agriculture constitutes a relatively small share of the economy. With high labor and land costs, production factors tend to flow toward more lucrative secondary and tertiary industries. As a result, the adoption and expansion of NQPFs are constrained in these regions.

An interesting finding is that a cross-reference of Table 10 and Table 11 reveals a clear regional pattern: major grain-producing areas are mainly concentrated in central China, grain-balanced areas in the western region, and grain-deficit areas almost entirely along the eastern coast. This confirms that the findings from Table 10 and Table 11 are mutually corroborative, collectively showing a distinct geographical gradient in NQPFs’ empowering effect: Central > Western > Eastern China.

7. Conclusions

7.1. Research Findings and Policy Recommends

7.1.1. Research Findings

This study uses a panel dataset spanning 31 Chinese provinces (2012–2022) to explore the relationship between NQPFs and agricultural sustainable development. It explores their driving processes, underlying mechanisms, and heterogeneous impacts. The principal findings are as follows:

First, NQPFs significantly promote agricultural sustainable development—a conclusion robustly validated through extensive testing.

Sencond, Mechanism analysis reveals that NQPFs empower agricultural sustainable development primarily by elevating agricultural science and technology innovation.

Third, Extended analysis demonstrates that rural economic development levels exert a notable moderating effect on NQPFs’ sustainability empowerment.

Finally, The empowering effect of NQPFs exhibits significant heterogeneity across regions and agricultural functional zones.

This study constructs a novel functional mechanism pathway of “NQPFs—Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Level—Agricultural Sustainable Development”, verifies the positive moderating effect of rural economic development level in this process, and thereby clarifies the two core focus points for NQPFs to boost agricultural sustainable development. In summary, the findings of this study can provide solid theoretical support and practical guidance for relevant authorities to formulate policies advancing agricultural modernization.

7.1.2. Policy Recommends

We make the following policy recommendations in light of the findings:

First, accelerate NQPFs development. Governments should boost R&D funding for cutting-edge technologies such as biotech, AI, and renewables to enhance productivity and industrial integration. Institutional innovations such as improving IP protection and policy support are crucial to foster NQPFs growth and agricultural sustainable development.

Second, tailor the advancement of NQPFs to align with the specific conditions of different regions and agricultural functional zones:

(1) Eastern region: Incentivize high-tech enterprises and internet platforms via tax benefits and spatial planning support to participate in agricultural value chain upgrading, thereby boosting product added value and attracting high-end production factors.

(2) Central region: Prioritize agricultural scale expansion and mechanization, strengthen farmer skill training, and facilitate the rural workforce’s shift from manual labor to technical roles [81].

(3) Western region: Introduce advanced agricultural machinery, optimize infrastructure to enhance production efficiency and market competitiveness [82], and accelerate digital agriculture development through the integration of big data and IoT technologies into production.

(4) Major grain-producing areas: Expand high-performance agricultural machinery subsidies; promote precision seeding, smart irrigation and harvest loss-reduction technologies [83]; build large-scale standardized grain bases; strengthen black soil conservation and high-standard farmland construction; and support R&D breakthroughs in bio-breeding and improved seed propagation.

(5) Grain-balanced areas: Construct on-site cold chain infrastructure and promote agricultural product e-commerce and contract farming models.

(6) Major grain-marketing areas: Support local enterprises in establishing direct procurement bases in major producing and balanced areas; develop an agricultural supply-demand big data platform to realize precise production-marketing matching and low-carbon supply chain management.

Third, enhance the level of agricultural scientific and technological innovation. Increase investment in mechanization, informatization, and smart agriculture [2]. Enhance agricultural education to cultivate skilled talent and establish innovation platforms with integrated services. Financial incentives such as subsidies and preferential policies can retain rural talent, while industry–university–research collaboration will optimize innovation systems [41].

Fourth, elevate the degree of economic growth in rural areas. Improve rural financial mechanisms and digital inclusive finance to support agricultural scientific and technological innovation [42]. To close the gap between urban and rural areas and promote sectoral collaboration, strengthen transportation, telecommunications, and energy infrastructure and promote rural digitalization through e-commerce and smart agriculture.

7.2. Limitations of the Study and Future Research Directions

NQPFs are not unique to China, but rather represent a synthesis and practical application of established global economic and development theories—such as Schumpeterian Theory of Innovation, Endogenous Growth Theory, National Innovation Systems, and the Global Green and Digital Transitions. This research addresses four fundamental questions: whether NQPFs influence agricultural sustainable development, through what mechanisms, under what conditions these effects are enhanced, and how the effects vary across regions. It establishes a novel “NQPFs–Agricultural Technological Innovation–Agricultural Sustainable Development” empowerment mechanism and identifies key driving pathways.

However, this study has several limitations. First, due to its reliance on provincial-level data from China, the generalizability of the findings to other contexts may be limited. Second, although agricultural technology innovation and rural economic development are incorporated as mediating and moderating variables, other unexplored factors may also exist. Third, the analysis assumes linear relationships between variables, whereas threshold or diminishing effects may exist in reality.

Therefore, future research should seek to extend and validate these findings through cross-country comparative studies involving diverse political–economic systems, agricultural structures, and resource endowments. Additional efforts are needed to identify other drivers of agricultural sustainable development to establish a more comprehensive explanatory framework. Moreover, the introduction of nonlinear models could help examine potential threshold effects or complex interactions, thereby enabling a more precise understanding of the mechanisms through which NQPFs influence agricultural sustainable development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Y.; methodology, Y.C.; software, Y.C.; validation, Y.C.; formal analysis, Y.C.; investigation, Y.C.; resources, Y.C.; data curation, Y.C.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.C.; writing—review and editing, Y.C.; visualization, Y.C.; supervision, Z.Y.; funding acquisition, Z.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Sichuan Provincial Department of Science and Technology, Research on the Forging Mechanism and Regional Collaborative Path of Rural "Three-industry" Integration Empowering Agricultural Resilience in Sichuan Province (SCJJ25RKX050); and China West Normal University, Research on the Microeconomic Foundation of Rural Revitalization (SCXTD2022-4).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study were derived from the National Bureau of Statistics of China, China Environmental Statistical Yearbook, China Rural Statistical Yearbook, China Statistical Yearbook, China Science and Technology Statistical Yearbook, China Industrial Statistical Yearbook. Detailed data are available on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to appreciate the editors and the anonymous reviewers for their insightful suggestions to improve the quality of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tang, J.; Liu, J. Evaluation and coupling coordination analysis of provincial agricultural sustainable development: A case of 11 provinces in the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Econ. Geogr. 2022, 42, 179–185. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Huo, Y. How to empower agricultural economic resilience through NQPFs: Mechanism analysis and promotion approach. J. Hubei Univ. Philos. Soc. Sci. 2025, 52, 164–173. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, M.; Cao, M.; Huang, H. Research on the Connotation, Characteristics and Development Path of New Quality Productive Force. World Surv. Res. 2024, 11, 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, G.; Song, X. The Mechanisms and Effects of Agricultural Science and Technology Finance Enabling Sustainable Agricultural Development under New Competitive Relationships. Sci. Manag. Res. 2024, 42, 116–126. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, W.; Zhao, C.; Su, Z. A Study on the Development Path of NQPFs Based on Four “New” Dimensions. J. Lanzhou Univ. Soc. Sci. 2024, 52, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, B.; Guo, H. Strategic logic and practical path of the formation of NQPFs under the background of the new scientific and technological revolution. J. Bus. Econ. 2024, 8, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. Research on the core essence, theoretical continuity and practical path of NQPFs. J. Jiangxi Norm. Univ. Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2024, 57, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Yang, Y. A study on the measurement, dynamic evolution, and driving factors of NQPFs development in China. Soft Sci. 2025, 39, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Guo, Z. NQPFs in urban areas: Level measurement, spatiotemporal evolution and influencing factors: A study based on the panel data of 277 cities in China from 2012 to 2021. Soc. Sci. J. 2024, 4, 124–133. [Google Scholar]

- Batie, S.S. Sustainable Development: Challenges to Profession of Agricultural Economics. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1989, 71, 1083–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, W. The theoretical connotation of sustainable development: The 20th anniversary of UN conference on environment and development in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2012, 22, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H.; Kong, X.; Chu, B. Strengthening the technical and economic research of agricultural sustainable development and agricultural modernization: Summary of academic views of the academic symposium of China Society of Agricultural Technical and Economic Studies. J. Agrotech. Econ. 1999, 6, 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Talukder, B.; Blay-Palmer, A.; vanLoon, G.W.; Hipel, K.W. Towards Complexity of Agricultural Sustainability Assessment: Main Issues and Concerns. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2020, 6, 100038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathaei, A.; Štreimikienė, D. A systematic review of agricultural sustainability indicators. Agriculture 2023, 13, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Ma, Z. Research on evaluation of agricultural sustainable development level based on entropy method: An example of Anhui Province. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2019, 47, 231–233+237. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M. Evaluation of agricultural sustainable development level in Henan Province based on entropy method. South China Agric. 2024, 18, 129–132. [Google Scholar]

- Valizadeh, N.; Hayati, D. Development and validation of an index to measure agricultural sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 123797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H. Evaluation of sustainable development of agricultural ecology in Jiangsu Province. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2019, 40, 164–170. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Chen, L.; Zhang, A. Evaluation of China’s Agricultural Sustainable Development Based on SD Synergetics Model. J. Jiaying Univ. 2024, 42, 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Saleem, A.; Anwar, S.; Nawaz, T.; Fahad, S.; Saud, S.; Rahman, T.U.; Khan, M.N.R.; Nawaz, T. Securing a sustainable future: The climate change threat to agriculture, food security, and sustainable development goals. J. Umm Al-Qura Univ. Appl. Sci. 2025, 11, 595–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.; Zhang, J. Progress and Challenges of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in the World and China. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2024, 39, 804–808. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, H.; Xu, R.T.; Canadell, J.G.; Thompson, R.L.; Winiwarter, W.; Suntharalingam, P.; Davidson, E.A.; Ciais, P.; Jackson, R.B.; Janssens-Maenhout, G.; et al. A comprehensive quantification of global nitrous oxide sources and sinks. Nature 2020, 586, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, X.; LV, X. Climate-smart agriculture under the Sustainable Development Goals: Concept discrimination, basic issues and implications from China’s practice. Geogr. Res. 2023, 42, 2018–2035. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Zhu, M.; Chen, W. Constraint and incentive: Research on sustainable development mechanism of agriculture and rural areas. Agric. Econ. 2019, 2, 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, A.; Yadav, K.; Abd-Elsalam, K.A. Nanofertilizers: Types, Delivery and Advantages in Agricultural Sustainability. Agrochemicals 2023, 2, 296–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.; Luo, R. China’s agricultural green development under the “double carbon” goal: Theoretical framework, dilemma review and solution. Rural. Econ. 2023, 2, 106–115. [Google Scholar]

- Vejan, P.; Abdullah, R.; Khadiran, T.; Ismail, S.; Nasrulhaq Boyce, A. Role of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria in agricultural sustainability—A review. Molecules 2016, 21, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morchid, A.; El Alami, R.; Raezah, A.A.; Sabbar, Y. Applications of internet of things (IoT) and sensors technology to increase food security and agricultural sustainability: Benefits and challenges. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 102509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ur Rehman, W.; Koondhar, M.A.; Afridi, S.K.; Albasha, L.; Smaili, I.H.; Touti, E.; Aoudia, M.; Zahrouni, W.; Mahariq, I.; Ahmed, M.M.R. The role of 5G network in revolutionizing agriculture for sustainable development: A comprehensive review. Energy Nexus 2025, 17, 100368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.-N.; Pan, Z.-C.; Zhu, W.; Wu, E.-J.; He, D.-C.; Yuan, X.; Qin, Y.-Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, R.-S.; Thrall, P.H.; et al. Enhanced agricultural sustainability through within-species diversification. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, J. Applying plant ecological knowledge to increase agricultural sustainability. J. Ecol. 2017, 105, 865–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, L.P.; Wulster-Radcliffe, M.C.; Aaron, D.K.; Davis, T.A. Importance of Animals in Agricultural Sustainability and Food Security. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 1377–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thwaites, H.J.; Hume, I.V.; Cavagnaro, T.R. The case for urban agriculture: Opportunities for sustainable development. Urban For. Urban Green. 2025, 110, 128861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Yin, T. NQPFs enabling sustainable agricultural development: Internal logic and practical approach. Contemp. Rural. Financ. Econ. 2024, 10, 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. Study on the mechanism of NQPFs to sustainable development of agricultural economy from the perspective of rural revitalization. China Collect. Econ. 2024, 36, 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, W. The era connotation and core significance of NQPFs. Mao Zedong Res. 2024, 6, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.; Song, M.; Wu, Q. The connotation, development dilemmas and pathways of new quality productive forces in agriculture. Contemp. Econ. Res. 2025, 5, 90–98. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, X.; Qi, Y.; Lan, H. Theoretical logic and practical path of green transformation of agriculture promoted by NQPFs forces from the perspective of “productivity-mode of production-relationships of production”. J. Sichuan Norm. Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2025, 52, 87–95, 202–203. [Google Scholar]

- Pu, L.; Han, X. The promoting effect of new agricultural quality productivity on agricultural and rural modernization. J. Shandong Agric. Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2025, 27, 112–120, 128. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y. Theoretical logic and practical path of NQPFs accelerating agricultural green transformation. Acad. J. Zhongzhou 2024, 12, 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Liang, H.; Qin, H. The influence of agricultural science and technology resource flow on the high-quality development of agriculture from the perspective of NQPFs. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2024, 44, 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Ji, D.; Zhang, L.; An, J.; Sun, W. Rural Financial Development Impacts on Agricultural Technology Innovation: Evidence from China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winarno, K.; Sustiyo, J.; Aziz, A.A.; Permani, R. Unlocking agricultural mechanisation potential in Indonesia: Barriers, drivers, and pathways for sustainable agri-food systems. Agric. Syst. 2025, 226, 104305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, A.; Wang, S. Mechanism and effect of NQPFs on agricultural resilience—Based on the analysis of panel data of 30 provincial administrative regions in China. J. Hunan Agric. Univ. Soc. Sci. 2025, 26, 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Deller, S.C.; Gould, B.W.; Jones, B. Agriculture and Rural Economic Growth. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2003, 35, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Zhang, P. Myth of the digital economy: Can it continually contribute to a low-carbon status and sustainable development? Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2025, 110, 107688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, M. The Impact of Digital Economy on High-Quality Development of Agriculture—Analysis Based on the Mediating Effect of Technological Innovation. Theory Pract. Financ. Econ. 2025, 46, 111–117. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, T. Study on the Influence of NQPFs on Rural Revitalization—An Empirical Test Based on Intermediary Effect and Threshold Effect. J. Party Sch. Leshan Munic. Comm. C.P.C 2025, 27, 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wei, Y. Impact of new quality agricultural productive forces on farmers’ income growth. J. Agro-For. Econ. Manag. 2024, 23, 446–455. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Chen, D.; Yu, G.; Pu, J. Impact of agricultural productive services on food security based on spatial spillover effects and heterogeneity analysis. J. Chin. Agric. Mech. 2024, 45, 344–352. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, T. Mediating effects and moderating effects in causal inference. China Ind. Econ. 2022, 5, 100–120. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Gao, W. Sustainable development of agriculture and rural areas in China and scientific and technological countermeasures. Resour. Sci. 1996, 1, 1–9. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=cP5JN5wNT8CgeVDB8p5aeFDVh76NRSsu3T5iPtwNf5q5VobZxR9FBNOPY7vw5kbI2yb_AmheEqWQ_50GWYrqiT0imj8B8RDPqnVE25KYt8nU-zt_KsrYlk8kD8tlgdGh6FL2aZJjGKHqKRlO7uel6oHiRs--5S9l7fUot1e_ZQ4=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Zhao, Y.; Gao, R. Research on the impact mechanism of rural population aging on agricultural ecological efficiency. Res. Agric. Mod. 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.X.; Zhou, Y. Measurement of agricultural economic development level in Heilongjiang Province. Coop. Econ. Sci. 2025, 18, 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Mao, J.; Zhang, X. Digital financial inclusion and agricultural green development—From the perspectives of easing financial constraints. Rural. Financ. Res. 2024, 2, 39–57. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.L. Spatiotemporal differentiation of rural residents’ income in Hunan and its influencing factors. Hunan Agric. Sci. 2024, 1, 84–92. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.D.; Li, C.B.; Cao, Y.X.; Gao, W.X. Spatiotemporal characteristics and development paths of agricultural green development level. J. Southwest For. Univ. Soc. Sci. 2024, 8, 62–68. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, J.C.; Li, Z.P.; Cui, X.R.; Liu, B. Digital economy driving new-quality productive forces: Mechanism and regional differences. Product. Res. 2025, 11, 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.M.; Ji, F. Digital economy empowering the development of new-quality productive forces: Mechanism analysis and spatial spillover. Mod. Financ. Econ. J. Tianjin Univ. Financ. Econ. 2025, 45, 25–46. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Wang, Y.P.; Guo, Z.A. The impact of digital infrastructure construction on the development of new-quality productive forces. Shanghai Econ. Res. 2024, 12, 16–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ming, H.R.; Xue, G. Research on the dynamic threshold effect of green taxation and new-quality productive forces: Evidence from China based on the “Porter Hypothesis”. Tax Econ. Res. 2025, 30, 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, R.; Sun, H.; Tuo, C.J.; Lu, Y. Can the coordination of digital and green policies empower the development of new-quality productive forces? Empirical evidence from the dual pilots of big data comprehensive experimental zones and low-carbon cities. Soft Sci. 2025, 39, 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, C.W.; Li, W.Y.; Chen, H.Q.; Xiang, X.H.; Wang, Y.Y. How does factor agglomeration affect new-quality productive forces through dual innovation? Stud. Sci. Sci. 2025, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Mai, X.L.; Mai, X.M.; Yan, B. Research on the impact of new-quality productive forces on the high-quality development of marine economy based on spatial econometric model. Mar. Sci. Bull. 2025, 44, 117–130. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.L.; Wei, Q.F. Banking competition, technology credit supply and new-quality productive forces. Int. Financ. Res. 2025, 11, 108–120. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, G.B.; Shen, Y.Y. How can new infrastructure empower the improvement of new-quality productive forces? Mod. Econ. Res. 2025, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Qiao, G.J.; Cai, J.R. Research on the impact of population aging on the development of new-quality productive forces. Northwest Popul. J. 2025, 46, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.H.; Pan, T. The impact of new-quality productive forces on urban-rural integrated development and its internal mechanism. J. Chongqing Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2025, 31, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.L.; Liu, H.J.; Yang, Q. Spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of the coupling coordination between carbon emission intensity and new-quality productive forces. Ecol. Econ. 2025, 41, 13–21+41. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=cP5JN5wNT8BsdD9KTLk0Dzb_HBhUw1UtTlCAdOJ2ycbtr4iCAj62vfl_N0hlHfwbXsVD0VavOLWcVZBlBO3G6w-iE8_O7BEWgPO4p9Tge1wW_oGQKBOFK3-y6QacafAI1vAjyHI9FYCtVoClv6RqHqF9H4UVJjcIL2uh3p5C85ridjjBJID0fA==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Zhou, S.; Yin, Z. Does agricultural insurance promote the green development of agriculture in China? J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 1, 49–61. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Fan, X.; Chen, P. Scale operation and green development of agriculture—Observations on agricultural green total factor productivity. J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2024, 4, 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Zheng, R.; Li, P.; Huang, S. Evaluation and analysis of agricultural science and technology innovation efficiency in Henan Province. J. Henan Agric. Univ. 2018, 52, 464–469, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X. Research on statistical measurement and improvement path of China’s rural industrial chain modernization. Stat. Decis. 2024, 40, 90–94. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S.; Xu, Y.; Huang, J. Evaluation of agricultural green development level based on entropy-weighted TOPSIS model: A case study of Henan Province. J. Zhejiang Univ. Agric. Life Sci. 2024, 50, 221–230. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Lin, W. Agricultural technology innovation, spatial correlation and farmers’ income. Financ. Econ. 2018, 7, 70–82. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Xiang, G.; Zhang, L. Environmental regulation, technological innovation and sustainable growth of agricultural economy. J. Anhui Agric. Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2021, 30, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Auty, R.M. Sustaining Development in Resource Economies: The Resource Curse Thesis; Routledge: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, C.; Ma, P.; Liao, S. A quantitative test of the resource curse and its micro-mechanism: Evidence from CFPS data. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2018, 28, 138. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, M.; Wei, H. Natural resource endowment and the behavior of Chinese local governments. Econ. Perspect. 2016, 1, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Jiang, W.; Pei, E. The impact of market integration on industrial chain resilience: A quasi-natural experiment based on the fair competition review system. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2024, 44, 21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, M.; Cheng, Y.; Chang, M. Agricultural new quality productivity empowering agricultural total factor productivity: Theoretical mechanism and empirical test. J. Jiangxi Univ. Financ. Econ. 2025, 4, 88–100. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Wang, T. Green new quality productivity and domestic-international dual circulation in agriculture: Mechanism analysis and empirical test. Stat. Decis. 2025, 41, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, S.; Singh, S. Role of innovation for sustainable development in agriculture: A review. Agric. Rev. 2025, 46, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.