Abstract

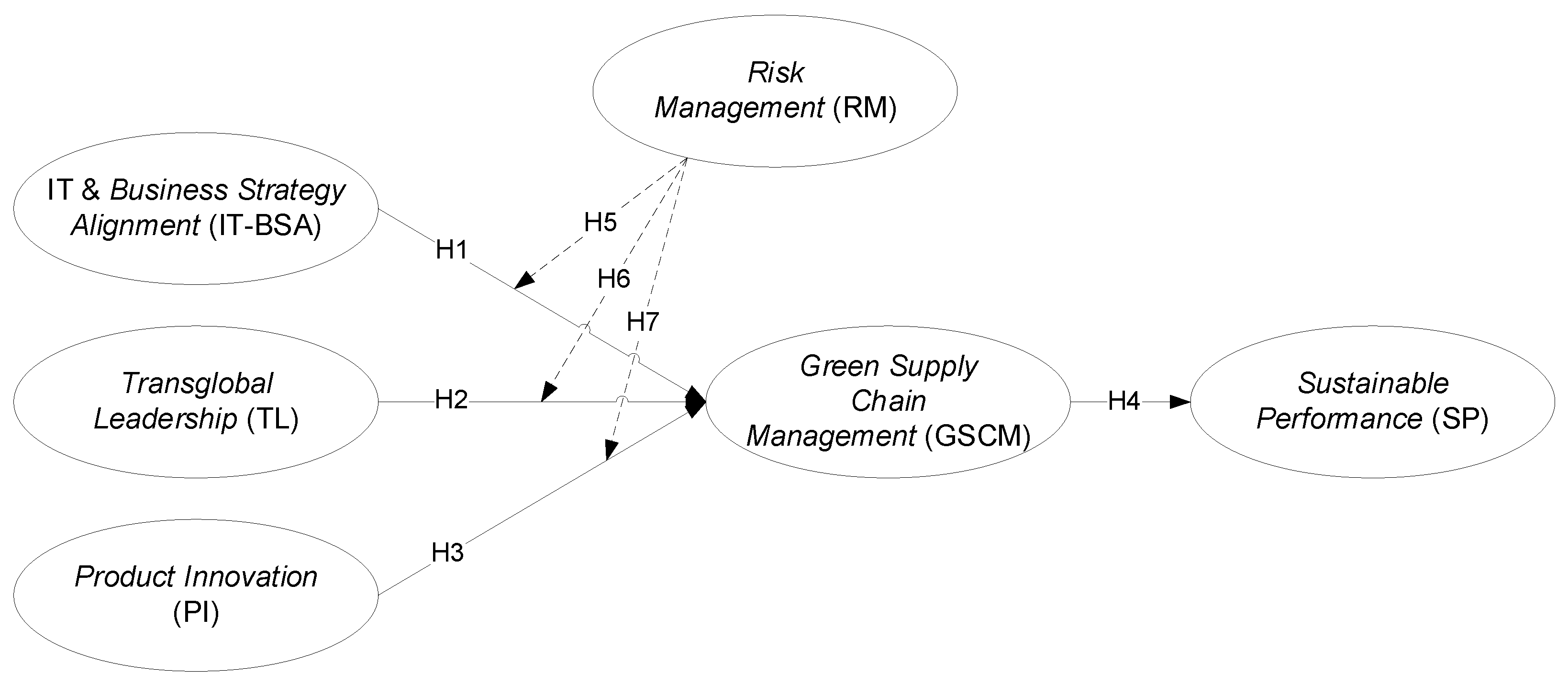

This study aims to investigate the impact of strategic drivers, specifically IT & Business Strategy Alignment (IT-BSA), Transglobal Leadership (TL), and Product Innovation (PI), on the adoption of Green Supply Chain Management (GSCM) and its subsequent effect on Sustainable Performance (SP). A key objective is to examine the moderating role of Risk Management (RM) in the relationship between these drivers and GSCM. This research employs a quantitative methodology, utilizing survey data collected from 216 middle and top Indonesian oil and gas managers. The hypothesized relationships were tested using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). The findings reveal that IT-BSA, TL, and PI are significant positive GSCM antecedents. Furthermore, GSCM has a strong, positive impact on SP. The results confirm that RM significantly and positively moderates the influence of all three strategic drivers on GSCM adoption. These findings provide a clear managerial roadmap, highlighting that an active risk management framework is critical for translating internal capabilities into effective sustainability practices, thereby enhancing a firm’s competitive advantage and long-term performance.

1. Introduction

In the contemporary business landscape, organizations operate within increasingly dynamic, complex, and unpredictable contexts [1]. Global supply chains face intensifying public and regulatory pressure due to a predominant share of corporate greenhouse gas emissions and substantial pressures on natural resources [2]. This reality has pressured firms to adopt environmentally friendly practices, especially within their supply chain activities [3,4]. GSCM has emerged as an essential strategic approach for integrating environmental considerations into the entire supply chain, from product design and material sourcing to manufacturing and end-of-life management. Ahmad & Karadas [5] stated that the fundamental goal of GSCM is to reduce environmental impact and improve organizational performance on the path toward sustainable development. This initiative assists firms in enhancing their Sustainable Performance—a multidimensional construct encompassing environmental, social, and economic performance—across all upstream and downstream activities [6]. The positive relationship between GSCM practices and the achievement of SP is well-documented in the literature, establishing GSCM as a critical pathway for firms aiming to balance profitability with ecological and social responsibilities [7,8,9,10]. This tension between competitiveness and sustainability is particularly acute in carbon-intensive and high-risk sectors such as upstream oil and gas, where firms must simultaneously ensure operational safety, maintain energy security, and respond to rising expectations related to the global energy transition [11].

The successful implementation of GSCM is not spontaneous but is driven by a confluence of organizational capabilities and strategic orientations. Leadership, in particular, is a decisive factor, as effectively guiding a group of employees is fundamental to executing organizational strategies [12]. Leadership, such as transglobal leadership, with its emphasis on cognitive, moral, emotional, cultural, business, and global intelligence [13], has been shown to positively influence the adoption of GSCM [5,14]. A supply chain leader drives improvement and change across all areas, from process design to fostering innovation and team loyalty [12]. Alongside leadership, innovation stands out as a critical antecedent. Specifically, green innovation, which refers to revolutionary environmental advancements in practices, processes, and products, is a core component of GSCM [15,16]. Furthermore, the alignment of technology with business strategy is a powerful enabler. The adoption of Industry 4.0 technologies and its alignment with business strategy, for instance, is significantly and positively correlated with GSCM practices and subsequent sustainability performance [17], demonstrating that technological advancement is crucial for achieving green objectives.

Despite a growing body of research establishing the links between these drivers (e.g., IT & business strategy alignment, transglobal leadership, product innovation) and GSCM, and between GSCM and Sustainable Performance, the findings are inconsistent. This variance suggests that the relationships are complex and may be influenced by contextual or organizational factors acting as moderators. While some studies have explored the moderating role of institutional pressures [18] or demographic factors like gender [19], a critical variable, particularly pertinent to high-stakes industries like oil and gas, remains underexplored, which is risk management. The oil and gas sector operates in a dynamic and unpredictable environment, where exploring and managing risks are prerequisites for survival and success [20]. The view of risk management has evolved from a siloed approach to a holistic, firm-wide framework known as Enterprise Risk Management (ERM). A firm’s perception of risk and its management capability directly shape its strategic approach [21]. Crucially, studies show that SMEs tend to follow either an “active” or “passive” ERM approach, which in turn affects whether their strategic orientation is offensive (“prospectors”) or defensive (“defenders”) [22]. This moderating mechanism is likely to be particularly salient in high-risk industries such as the oil and gas sector, where governance and stakeholder pressures increasingly require the integration of sustainability into risk management [23], and where risk assessment frameworks are used to support sustainable, lower-risk operations [24]. The implementation of GSCM is an inherently proactive, forward-looking strategic decision. Therefore, a significant research gap exists in understanding how a firm’s established risk management posture influences its willingness and ability to translate strategic drivers into tangible GSCM practices.

To investigate these complex interrelationships, this study is grounded in the firm’s Resource-Based View (RBV). The RBV posits that a firm can achieve a sustainable competitive advantage by developing and deploying valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable resources and capabilities [25]. According to Grant [26], a firm’s internal strengths and weaknesses are more controllable than external factors and thus form the foundation of its strategy. Following this logic, this study conceptualizes IT-Business Strategy Alignment, Transglobal Leadership, and Product Innovation as valuable tangible and intangible resources, including technological, human, and organizational capital. The firm’s Risk Management framework is positioned as a critical dynamic capability that governs how these internal resources are orchestrated. Consequently, GSCM is viewed as a higher-order organizational capability that, when effectively developed through the bundling of these strategic resources, leads to enhanced Sustainable Performance.

Addressing this gap is theoretically important because, from the resource-based view, green supply chain practices depend on how firms configure valuable, rare, and hard-to-imitate capabilities, while the risk-based view clarifies how sector-specific hazards condition the conversion of those capabilities into performance. It is also particularly in high-risk and carbon-intensive sectors such as the upstream oil and gas industry. In Indonesia, upstream activities are coordinated by the national regulator, Satuan Kerja Khusus Pelaksana Kegiatan Usaha Hulu Minyak dan Gas Bumi (SKK Migas), which oversees Production Sharing Contract (PSC) contractors. Practically, PSC companies under SKK Migas supervision must simultaneously manage operational, environmental, and social risks while responding to energy transition and ESG pressures [23]. For these organizations, understanding how different risk management approaches can enable or hinder investments in green technologies, process innovations, and GSCM practices is crucial for designing risk governance systems that support, rather than constrain, sustainable performance [24].

This study aims to address the identified gap by examining the antecedents of GSCM and its subsequent impact on performance within the Indonesian oil and gas industry. Specifically, this paper seeks to answer the following research questions:

- (RQ1): How do strategic drivers (IT-Business Strategy Alignment, Transglobal Leadership, and Product Innovation) and the moderating effect of Risk Management influence the adoption of GSCM practices?

- (RQ2): Does implementing GSCM practices affect Sustainable Performance?

This article proceeds as follows: Section 2 reviews the underpinning theories and develops the research hypotheses and theoretical model. Section 3 outlines the research methodology, including the instrument design, sampling procedures, and data collection process. In Section 4, the data analysis and corresponding results are presented. Section 5 provides a detailed discussion of the findings. The final section concludes the paper by summarizing the key findings, acknowledging the limitations, and suggesting directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Underpinning Theory

2.1.1. Theoretical Foundation: Resource-Based View (RBV)

RBV is a foundational theory in strategic management that explains how firms achieve and sustain a competitive advantage. The central premise of the RBV, as Grant [26] articulated, is that a firm’s competitive advantage stems primarily from its unique and valuable internal resources and capabilities rather than its positioning in the external market environment. This inside-out approach focuses on a firm’s internal strengths and weaknesses, which are more readily controllable than external factors. Resources within this view are broadly categorized and include physical capital and intangible assets such as human capital, financial capital, technological capital, and organizational capital [27]. For these resources to provide a sustained competitive advantage, they must be valuable, rare, difficult to imitate, and non-substitutable (VRIN) [25,28,29]. The RBV, therefore, offers a robust framework for understanding how the strategic management and orchestration of a firm’s unique internal assets can lead to superior performance.

In the context of this study, RBV serves as the main theoretical lens for conceptualizing IT–Business Strategy Alignment, Transglobal Leadership, and Product Innovation as strategic resources and capabilities that can be bundled and leveraged to support the development of GSCM practices. By viewing these constructs as part of a firm’s resource base, RBV helps explain how their effective configuration and deployment can ultimately enhance Sustainable Performance, particularly in high-risk and capital-intensive contexts such as the upstream oil and gas industry. Building on this resource-based perspective, the following subsections elaborate on the main strategic drivers and outcome constructs used in the proposed model.

2.1.2. Strategic Drivers of Green Supply Chain Management

Strategic drivers are the internal orientations, resources, and capabilities that enable firms to translate sustainability ambitions into concrete supply chain practices. In line with the RBV perspective, this study focuses on three interrelated strategic drivers that are particularly relevant for the development of GSCM, namely IT–Business Strategy Alignment (IT-BSA), Transglobal Leadership (TL), and Product Innovation (PI). Together, these drivers shape how information is used to support environmental decision-making, how people are mobilized around sustainability goals, and how products and processes are redesigned to reduce environmental impacts along the supply chain.

IT–Business Strategy Alignment has been a significant and persistent challenge for organizations [30]. This concept, also referred to as ‘fit’ [31], ‘harmony’ [32], ‘fusion’ [33], ‘integration’ [34], or ‘linkage’ [35], involves coordinating activities across IT and non-IT domains to create business value. It is not a static state but a dynamic relationship that requires ongoing adjustment. Effective alignment is built upon six key dimensions: (1) Communications between business and IT, (2) the use of Value Analytics to measure IT’s contribution, (3) formal IT Governance processes, (4) a strong Partnership between the functions, (5) a flexible and forward-looking IT Scope, and (6) strategic IT Skills Development [30]. When these dimensions are mature, IT can be leveraged as a fundamental driver of business strategy, positively impacting overall company performance. In the context of GSCM, such alignment ensures that environmental and supply chain objectives are embedded in core business processes rather than treated as isolated initiatives.

Building on this technological and strategic alignment, Leadership is fundamentally a process of influencing and guiding the behavior of individuals or groups toward achieving a specific set of goals [36]. Emerging from traditional leadership styles like transactional and transformational leadership, Transglobal Leadership is a recent conceptualization designed for a globalized world [37]. It is defined as an effective leadership style across diverse countries and cultures, enabling leaders to manage global production, marketing, and sales to achieve a competitive advantage [13]. This leadership model is characterized by six core types of intelligence that a leader must possess [13]: (1) Cognitive intelligence (IQ), (2) Moral intelligence (ethics), (3) Emotional intelligence (empathy and connection), (4) Cultural intelligence (understanding local values), (5) Business intelligence (understanding business components), and (6) Global intelligence (understanding international laws and procedures). Such leadership capabilities are essential for articulating a sustainability vision and coordinating the behavioral and cultural changes required for GSCM implementation.

Complementing alignment and leadership, Product Innovation is the successful commercial exploitation of new ideas of process encompassing technical design, R&D, manufacturing, and marketing activities to bring a new or improved product to market [38]. Product innovation performance is widely conceptualized as having two distinct dimensions: efficacy and efficiency [39]. Efficacy reflects the degree of market success of the innovation, such as extending product range, increasing market share, or opening new markets. Efficiency, on the other hand, reflects the resources expended to achieve that success, measured by factors like development time, project cost, and overall project efficiency compared to competitors. When innovation efforts are specifically aimed at eliminating negative environmental consequences, they are termed green or eco-innovations, which are critical for implementing GSCM [15,40].

Taken together, IT-BSA, TL, and PI form a complementary bundle of strategic drivers that can facilitate the integration of environmental considerations into supply chain planning and operations. Aligned IT architectures provide the information backbone for monitoring and coordinating green initiatives, transglobal leaders offer the direction and commitment needed to embed sustainability into decisions, and environmentally oriented product innovations create demand for cleaner processes and reverse logistics solutions. This integrated configuration of strategic drivers provides the basis for examining how they influence GSCM and, through GSCM, Sustainable Performance in the empirical model of this study.

2.1.3. Risk Management, Green Supply Chain Management, and Sustainable Performance

Risk management (RM) has shifted from focusing on individual risks to adopting an all-encompassing perspective known as Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) [41]. Hunziker [42] stated that ERM is a holistic framework for identifying, assessing, and monitoring all threats and opportunities that may affect an entity’s ability to achieve its objectives. An organization’s approach to ERM is heavily influenced by the management’s interpretation and evaluation of risks [43]. This leads firms to adopt either an active ERM approach, which results in a more offensive or “prospector” strategy, or a passive approach, which results in a more defensive or “reactor” strategy [22]. This strategic orientation, shaped by the firm’s risk management posture, has considerable implications for its competitiveness and willingness to embrace proactive initiatives like GSCM [44,45]. In this study, GSCM is conceptualized as a primary channel through which risk-related decisions are translated into sustainability-oriented supply chain practices.

GSCM is an organizational philosophy that emerges from integrating environmental concerns into the entire supply chain [46]. This practice ranges from green purchasing of raw materials to the integrated life-cycle management of products, including reverse logistics to close the loop [47]. The scope of GSCM includes key practices such as internal environmental management, which involves top management commitment and ISO 14001 certification [48]; green purchasing from environmentally certified suppliers; and investment recovery through the sale of scrap and used materials [49]. Implementing these multifaceted practices is intended to reduce environmental risks and impacts, thereby improving the organization’s and its partners’ ecological efficiency and performance [50]. In doing so, GSCM provides a concrete operational mechanism through which firms pursue broader sustainability goals along the supply chain.

Sustainable Performance (SP) is a holistic concept that moves beyond traditional financial metrics to assess a firm’s long-term viability across three interconnected dimensions: economic, environmental, and social [7,51]. This “Triple Bottom Line” approach comprehensively evaluates a company’s impact [9]. The economic dimension includes traditional performance metrics like reliability, responsiveness, flexibility, cost, and quality. The environmental dimension focuses on a firm’s impact on the natural world, including reducing air, water, and land pollution; responsible use of resources; and managing dangerous materials. The social dimension assesses the consequences of a company’s activities on its stakeholders, encompassing work conditions, human rights, customer health and safety, and fair business practices. Integrating these three dimensions is essential for evaluating the true sustainability of a firm’s operations [51]. In this study, SP is treated as the ultimate outcome of GSCM implementation, so that the relationships among RM, GSCM, and SP capture how risk governance, green supply chain practices, and triple-bottom-line results are intertwined.

Taken together, RM, GSCM, and SP are closely interconnected. A firm’s risk management posture can either encourage or constrain investments in green technologies, process changes, and supply chain collaborations that underpin GSCM. In turn, the extent and quality of GSCM practices influence how effectively firms improve their economic, environmental, and social outcomes. Positioning RM as a moderating variable in this study reflects the idea that risk management conditions the strength of the relationships between strategic drivers and GSCM, and between GSCM and SP, particularly in high-risk and carbon-intensive contexts such as the upstream oil and gas industry.

2.2. Theoretical Model and Hypotheses Development

2.2.1. Antecedents of Green Supply Chain Management

The alignment of information technology with business strategy is a critical enabler for modernizing supply chains. Digital Technologies and Industry 4.0 paradigms allow for data collection, processing, and analysis, improving environmental planning, resource monitoring, and overall decision-making processes. Specifically, technologies like the Internet of Things (IoT) and Big Data Analytics (BDA) are essential for implementing GSCM practices by enabling real-time supply chain optimization, enhancing transparency, and monitoring production to reduce waste and energy expenditure [52,53]. The strategic alignment of IT and business ensures that these technological investments are not made in isolation but are leveraged to support core business goals, such as sustainability. This alignment fosters a shared understanding and creates a flexible IT infrastructure supporting complex, cross-functional environmental initiatives [30]. Therefore, a high level of IT-Business Strategy Alignment is expected to facilitate the effective implementation of GSCM.

H1.

IT & Business Strategy Alignment positively and significantly affects GSCM.

Leadership is fundamental to driving significant organizational change, and implementing GSCM is no exception. Effective leadership is essential for developing the vision, articulating the strategy, and mobilizing the resources necessary for green initiatives. Studies have shown that leadership styles directly influence the effectiveness of GSCM practices, as leaders are responsible for encouraging participation and creating a supportive environment [5,12,14]. This study employs the concept of Transglobal Leadership, which is particularly relevant for the globalized and culturally diverse nature of the oil and gas industry. A transglobal leader possesses the cognitive, cultural, and global intelligence required to manage complex international supply chains and to champion sustainability goals across different organizational and national boundaries [13]. Such leadership fosters the inter-employee trust and cross-functional cooperation necessary for a successful GSCM program.

H2.

Transglobal Leadership has a positive and significant effect on GSCM.

Product Innovation (PI) is intrinsically linked to GSCM, as the design of products determines a significant portion of their life-cycle environmental impact. Eco-innovation—developing products and services with clear environmental benefits—is a cornerstone of GSCM [54,55]. Practices such as designing products for reduced material and energy consumption, reuse and recycling, and avoiding hazardous substances are central to product innovation and GSCM [39,49]. The connection is direct; green product and process innovations facilitate GSCM practices like green purchasing and green manufacturing, fulfilling stakeholders’ ecological demands [56]. Therefore, a firm’s capability in product innovation is a direct antecedent to its ability to implement GSCM effectively.

H3.

Product Innovation has a positive and significant effect on GSCM.

2.2.2. Green Supply Chain Management on Sustainable Performance

The ultimate goal of implementing GSCM practices is to improve a firm’s holistic performance. Sustainable Performance (SP) is a multidimensional construct comprising economic, environmental, and social performance [47,51]. The literature provides strong evidence that GSCM positively influences all three pillars of sustainability. Environmental performance is the most direct outcome, with GSCM practices leading to a reduction in air emissions, wastewater, solid waste, and the consumption of hazardous materials [7,57,58]. Economic performance is enhanced through GSCM by reducing the costs of materials, energy, and waste treatment, while simultaneously improving corporate image and market share [8,53,58]. Finally, GSCM contributes to social performance by improving workplace safety, enhancing relationships with the community, and ensuring the firm acts as a responsible corporate citizen [7,59]. By integrating these dimensions, GSCM enables firms to move beyond a purely financial focus to achieve long-term, sustainable success.

H4.

GSCM has a significant positive effect on Sustainable Performance.

2.2.3. Risk Management as Moderation

The relationship between strategic drivers and the implementation of GSCM does not occur in a vacuum. Organizations operate in highly dynamic and unpredictable environments where risk is a constant factor [1], especially those in the oil and gas sector. ERM is the holistic framework used to identify, assess, and monitor all threats and opportunities facing a firm [60,61]. Crucially, a firm’s approach to ERM shapes its overall strategic orientation. Based on Brustbauer [22], firms with a passive ERM approach tend to be defensive and reactive, while those with an active ERM approach are more offensive and proactive, better able to exploit strategic opportunities. Implementing GSCM is a proactive, resource-intensive, and strategic undertaking, not merely a defensive compliance measure. Therefore, it is logical to posit that a firm’s risk management framework will moderate the impact of its strategic drivers on GSCM adoption. An active RM approach creates an organizational context that values and supports long-term strategic initiatives, thereby strengthening the positive influence of IT-BSA, TL, and PI on GSCM. Conversely, a passive RM approach may stifle these initiatives by prioritizing short-term risk avoidance over strategic green investments, thus weakening the relationship.

H5.

Risk Management significantly and positively moderates the effect of IT & Business Strategy Alignment on GSCM.

H6.

Risk Management significantly and positively moderates the effect of Transglobal Leadership on GSCM.

H7.

Risk Management significantly and positively moderates the effect of Product Innovation on GSCM.

Figure 1 above presents the complete conceptual model guiding this research. This model visually depicts all the hypothesized relationships between the antecedent variables (IT-Business Strategy Alignment, Transglobal Leadership, Product Innovation), the moderating variable (Risk Management), the mediating variable (Green Supply Chain Management), and the outcome variable (Sustainable Performance), which will be empirically tested in the subsequent sections of this study.

Figure 1.

Hypothesis Model.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sampling and Data Collection

The unit of analysis for this study is oil and gas companies operating in Indonesia. The target population was defined explicitly as companies registered as Production Sharing Contract (PSC) Contractors under the supervision of SKK Migas and have entered the production stage. SKK Migas (Satuan Kerja Khusus Pelaksana Kegiatan Usaha Hulu Minyak dan Gas Bumi) is the Special Task Force for Upstream Oil and Gas Business Activities, an institution formed by the Government of the Republic of Indonesia to manage and control upstream oil and gas projects so that the state receives maximum benefit for the prosperity of the people. Focusing on firms in the production stage ensures that the organizations have established and mature supply chain and risk management processes relevant to this research.

A purposive sampling technique was employed to select respondents for this study. As a non-probabilistic approach, purposive sampling does not allow for statistical generalization to the entire population and may introduce selection bias. This method was chosen to ensure the participants possessed deep and relevant knowledge of the study’s complex variables [62]. The target respondents were key informants holding middle and top management positions in supply chain management, operations, procurement, and strategic planning departments. This respondent group is considered the most appropriate as these managers are directly involved in strategic decision-making, aligning IT and business processes, leadership initiatives, innovation strategies, risk management framework implementation, and evaluating GSCM practices and their impact on sustainable performance. Thus, the sampling strategy prioritizes information-rich cases and expert judgment over random selection, and the findings should be interpreted as analytically generalizable to comparable PSC contractors rather than statistically representative of all firms in the sector.

Primary data was gathered using a quantitative electronic survey. A structured questionnaire was developed using Google Forms and distributed to the targeted respondents via email. This method was deemed adequate for reaching a specific and geographically dispersed professional audience, a practice consistent with contemporary supply chain research. After this period, 216 complete responses were obtained, forming the final sample utilized for data analysis in this study.

The demographic profile of the respondents indicates a sample with significant professional experience. In terms of gender, the participants were predominantly male, with 169 respondents (78.32%), compared to 47 female respondents (21.68%). The age distribution shows a mature cohort, with the largest group of respondents falling within the 38–42 age bracket (25.46%), followed by those aged 33–37 (23.61%) and 43–47 (22.69%). Regarding work experience, the majority of respondents possessed substantial industry knowledge, with the largest group having 0–5 years of experience (36.11%), and a significant portion having 6–10 years (24.07%) and 11–15 years (18.52%) of experience, respectively.

3.2. Measurement and Data Analysis

The variables in this study were operationalized using established scales from prior literature, with all items measured on a 5-point Likert scale to capture respondent perceptions. To assess IT-BSA, this study adopted the six dimensions from the Strategic Alignment Maturity (SAM) model developed by Luftman et al. [30], which are communications (IT-BSA 1), value analytics (IT-BSA 2), IT governance (IT-BSA 3), partnering (IT-BSA 4), IT scope (IT-BSA 5), and IT skills development (IT-BSA 6). For Transglobal Leadership (TL), the construct was operationalized using the scale from Pujiono et al. [13], which is based on six core intelligences: cognitive (TL 1), emotional (TL 2), cultural (TL 3), business (TL 4), global (TL 5), and moral intelligence (TL 6). The measurement scale for Product Innovation (PI) was derived from Alegre et al. [39], focusing on the two key dimensions of innovation performance: efficacy (PI 1) and efficiency (PI 2). This study measures Risk Management (RM) by employing the framework from Brustbauer [22], which evaluates Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) activities across three primary dimensions: risk identification (RM 1), risk assessment (RM 2), and risk monitoring (RM 3). The measurement of Green Supply Chain Management (GSCM) practices was adapted from the validated model by Zhu et al. [49], consisting: internal environmental management (GSCM 1), green purchasing (GSCM 2), and investment recovery (GSCM 3). Lastly, the Sustainable Performance (SP) measurement was adopted from the comprehensive framework by Chardine-Baumann & Botta-Genoulaz [51], which assesses performance across three primary pillars: economic (SP 1), environmental (SP 2), and social performance (SP 3).

This study employed second-order Partial Least Squares–Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) to empirically test the proposed theoretical framework and hypotheses. This statistical technique was selected for its flexibility in handling non-normal data distributions and its capacity to estimate complex models with multidimensional, higher-order constructs [63]. The model was specified as a reflective–reflective hierarchical component model, in which IT-BSA, TL, PI, RM, GSCM, and SP were treated as second-order reflective constructs indicated by their respective first-order dimensions. All estimations were performed using SmartPLS version 3.0.

3.3. Common Method Bias

Given that the data for this research was collected from a single respondent within each organization at a specific time, the potential for Common Method Bias (CMB) was recognized as a possible concern. To mitigate this issue, both procedural and statistical remedies were implemented. As a procedural measure, all participants were assured of the anonymity of their participation and the confidentiality of their responses. This assurance reduces social desirability bias by encouraging honest and thoughtful answers [3,64]. As a statistical remedy, a full collinearity test examined the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values for the latent constructs. Following Kock and Lynn [65], this statistical test helps to ensure that the shared variance among constructs does not significantly inflate the results, thereby confirming that CMB is not a substantial threat to the validity of the findings in this study.

4. Results

This study utilized second-order PLS-SEM to test the proposed theoretical framework and its hypotheses empirically. The model in this study is designed as a reflective-reflective type, making PLS-SEM particularly appropriate for its prediction-oriented objectives. The analysis followed an established two-stage approach: first, the evaluation of the measurement model for reliability and validity, and second, the assessment of the structural model to test the hypothesized paths [66]. In line with the standards proposed by Latan [67], the model estimation used a path weighting scheme with a maximum of 300 iterations in the PLS algorithm. Furthermore, an accelerated, bias-corrected (BCa) bootstrap procedure was employed for hypothesis testing, using 5000 resamples at a 5% significance level.

4.1. Evaluation of Measurement Model

The initial step involved assessing the quality of the measurement model [68]. As shown in Table 1, all constructs demonstrated strong reliability and validity. First, all outer loading values exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.708. The Composite Reliability (CR) values for all constructs ranged from 0.799 to 0.884, and Cronbach’s Alpha values were between 0.801 and 0.874, all well above the recommended threshold of 0.70, confirming high internal consistency. Furthermore, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for each construct was greater than the 0.50 benchmark, with values ranging from 0.769 to 0.835. This indicates that all constructs have adequate convergent validity, meaning each construct explains most of the variance in its respective indicators.

Table 1.

Results of Evaluation of Measurement Model.

In reflective measurement, the basic criterion is that the indicator with the highest standardized loading best represents its underlying variable. Using this criterion, the strongest indicators are: IT skills development (IT-BSA6, 0.917) for IT–Business Strategy Alignment; emotional intelligence (TL2, 0.928) for Transglobal Leadership; innovation efficacy (PI1, 0.873) for Product Innovation; risk monitoring (RM3, 0.869) for Risk Management; internal environmental management (GSCM1, 0.897) for Green Supply Chain Management; and economic performance (SP1, 0.933) for Sustainable Performance. These indicators provide the clearest representation of their respective constructs, while the remaining items also contribute but with comparatively smaller loadings.

To assess discriminant validity, the Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations was examined [68]. The results in Table 2 show that all HTMT values are below the conservative threshold of 0.85, with the highest value being 0.832. This confirms that each construct is distinct from the others in the model, thereby establishing sufficient discriminant validity. Overall, the evaluation of the measurement model confirms that all constructs are reliable and valid for subsequent structural model analysis.

Table 2.

Results of HTMT.

4.2. Evaluation of Structural Model

After confirming the measurement model, the structural model was evaluated to test the hypothesized relationships. Before that, multicollinearity was assessed by examining the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values for each construct. As detailed in Table 3, all VIF values were below the threshold of 3.3 [69], with the highest being 2.811, indicating that multicollinearity is not a significant issue in this model.

Table 3.

Variance Inflation Factors (VIF).

The results for the direct effect hypotheses are presented in Table 4. The model demonstrates moderate to substantial explanatory power for the endogenous variables. The antecedents collectively explain 65.9% of the variance in GSCM (R2 = 0.659), and GSCM explains 37.2% of the variance in Sustainable Performance (R2 = 0.372), which means GSCM and SP have moderate explanatory power [70]. All four direct effect hypotheses were supported. IT & Business Strategy Alignment (β = 0.329, p = 0.002), Transglobal Leadership (β = 0.468, p < 0.001), and Product Innovation (β = 0.382, p < 0.001) all have a significant and positive effect on Green Supply Chain Management, supporting H1, H2, and H3, respectively. Furthermore, GSCM was found to have a strong, significant positive effect on Sustainable Performance (β = 0.515, p < 0.001), supporting H4.

Table 4.

Significance of Direct Effect.

These results for H1 indicate that firms with higher levels of IT–Business Strategy Alignment tend to implement GSCM practices more extensively, as aligned IT and business processes provide the information infrastructure needed for green purchasing, internal environmental management, and investment recovery. For H2, the relatively large coefficient for Transglobal Leadership suggests that leadership capabilities oriented toward global and cross-cultural contexts play a particularly important role in driving the adoption of GSCM practices. The support for H3 shows that firms with stronger Product Innovation performance are more likely to embed environmental considerations into product and process design, which in turn reinforces green supply chain activities. Finally, the strong positive path in H4 confirms that more intensive implementation of GSCM is associated with higher Sustainable Performance, improving economic, environmental, and social outcomes simultaneously.

The significance of the moderation effects of Risk Management was also tested, with the results shown in Table 5. All three moderation hypotheses were found to be significant and positive. Risk Management was confirmed to positively moderate the relationship between IT-BSA and GSCM (β = 0.188, p < 0.001), TL and GSCM (β = 0.288, p < 0.001), and PI and GSCM (β = 0.235, p < 0.001). These results provide strong support for H5, H6, and H7, indicating that the presence of a robust risk management framework strengthens the influence of strategic drivers on the adoption of GSCM practices.

Table 5.

Significance of Moderation Effect.

These results for H5 indicate that the positive effect of IT–Business Strategy Alignment on GSCM becomes stronger when firms exhibit higher levels of Risk Management, meaning that aligned IT and business processes are more effectively translated into green supply chain practices under a more developed risk governance posture. For H6, the relatively larger interaction coefficient between Transglobal Leadership and Risk Management suggests that leadership capabilities are particularly sensitive to the firm’s risk management approach, with stronger risk management further enhancing the contribution of leadership to GSCM adoption. The support for H7 shows that the impact of Product Innovation on GSCM also increases as Risk Management becomes more robust, implying that innovative products and processes are more likely to be accompanied by green supply chain activities when they are embedded within systematic risk identification, assessment, and monitoring.

Finally, the model’s out-of-sample predictive power was assessed using the PLSpredict procedure. The results in Table 6 show that all Q2predict values for the indicators of the endogenous constructs are positive, confirming that the model has predictive relevance. Furthermore, when comparing the prediction errors (RMSE, MAE) of the PLS-SEM model against the linear model (LM) benchmark, the PLS-SEM model demonstrated lower or comparable error values for the majority of the indicators. This indicates that the structural model possesses a moderate level of predictive accuracy [68].

Table 6.

PLSpredict Results.

5. Discussion

5.1. Hypothesis Results

This study aimed to develop and empirically test a moderated model examining the antecedents of Green Supply Chain Management (GSCM) and its subsequent impact on Sustainable Performance (SP), with a particular focus on the moderating role of Risk Management (RM). The research was contextualized within the Indonesian oil and gas industry, a sector where sustainability and risk are paramount concerns. The empirical results provide strong support for the proposed theoretical framework, as all hypothesized direct and moderating relationships were found to be significant and positive. This section discusses these findings in detail, linking them to existing literature and the specific context of the study. Beyond confirming each hypothesis, the combined pattern of results clarifies how internal strategic drivers, risk governance, and GSCM interact as an integrated system that channels firm resources into sustainability outcomes, thereby enriching RBV-based explanations of green supply chain behavior.

The findings confirm that IT-BSA, TL, and PI are significant positive antecedents of GSCM adoption. The positive effect of IT-BSA on GSCM (H1) aligns with extensive research highlighting the enabling role of digital technologies in modern supply chains [17,53,71]. In the capital-intensive and technologically advanced Indonesian oil and gas sector, a robust alignment ensures that investments in technologies like IoT and data analytics are not merely for operational efficiency but are strategically directed to support complex environmental monitoring, logistics optimization, and regulatory compliance, which are core components of GSCM [52,53]. From RBV perspective, IT–BSA represents a strategic architectural capability—a system-level competence that allows firms to mobilize information resources toward environmental goals. When aligned with green objectives, this capability becomes rare and inimitable, generating sustained competitive advantage [25]. In theoretical terms, the finding shows that IT-BSA can be understood not only as a driver of efficiency and cost reduction, but also as a sustainability-oriented capability that helps explain why some firms are better than others at embedding environmental objectives into their supply chain processes.

Similarly, the significant positive influence of Transglobal Leadership on GSCM (H2) underscores the critical role of leadership in driving strategic change [5,8]. Operating within a global ecosystem that involves multinational partners, diverse local communities, and strong government oversight (including Indonesia’s SKK Migas), Transglobal Leaders—equipped with the cognitive, cultural, and global intelligence described by Pujiono et al. [13]—act as boundary-spanners who bridge multinational corporate expectations (e.g., ISO 14001, GHG Protocol) with local socio-ecological priorities and values (e.g., CSR and gotong royong norms). Within SKK Migas’s governance ecosystem, effective sustainability transformation depends not only on technical compliance but also on collaborative leadership mindsets capable of reconciling global ESG standards with Indonesian contextual realities; accordingly, SKK Migas could institutionalize such competencies through targeted programs like a Leadership and Governance Acceleration Program (LGAP) or ESG-based capacity-building modules for operator executives, ensuring that sustainability leadership is treated as a core strategic competency rather than an ancillary skill and thereby fostering the stakeholder buy-in and cross-functional cooperation required for successful GSCM implementation. This result, therefore, supports the view of TL as a relational capability that connects internal processes with external stakeholder expectations, providing a micro-foundation for the development and institutionalization of GSCM practices.

The support for H3, which posits a positive relationship between Product Innovation and GSCM, is consistent with the literature [15,40]. While the “product” in oil and gas refers to energy commodities, innovation extends to processes and outputs such as developing cleaner fuels, creating technologies to reduce emissions, and implementing circular economy principles [39]. These eco-innovations are fundamental to GSCM because they directly enable practices such as green purchasing and green manufacturing, reinforcing the view that innovation is a direct antecedent of advanced green practices [72,73,74]. In the Indonesian context, the significant relationship between Product Innovation and GSCM also indicates that SKK Migas-regulated firms are already leveraging innovation to support decarbonization through cleaner fuels, methane reduction technologies, and circular economy initiatives. This aligns with SKK Migas’s 2030 Net Zero Roadmap, which emphasizes technology-driven emission reduction and resource recovery. The finding further suggests that SKK Migas can evolve from being a regulator to becoming an innovation enabler by establishing joint R&D clusters among operators, universities, and technology startups, and by integrating innovation metrics into performance-based regulation (PBR), thereby strengthening Indonesia’s position in the ASEAN low-carbon energy transition. More broadly, the evidence positions PI as a dynamic capability that enables firms to periodically renew their technological and process configurations so that GSCM can be upgraded in line with increasingly stringent environmental and stakeholder demands.

The strong positive impact of GSCM on SP (H4) was robustly supported, aligning with a significant body of prior research [8,9,10]. This relationship holds across all three pillars of sustainability within the Indonesian oil and gas context. Environmentally, GSCM directly addresses the core operational risks of the industry by reducing emissions and waste [7]. Economically, the efficiencies gained from GSCM lead to cost reductions, while an improved sustainability profile enhances corporate image and strengthens relationships with key stakeholders like SKK Migas, potentially leading to better market access and financial performance [75]. Socially, GSCM contributes to improved workplace safety and fosters positive community relations [76], both of which are essential for maintaining a social license to operate in Indonesia. These findings reinforce that GSCM is not merely an environmental strategy but a comprehensive approach to achieving balanced and durable organizational success, while also confirming that environmental efficiency, operational reliability, and social legitimacy are mutually reinforcing. For SKK Migas, the evidence provides empirical justification to elevate GSCM indicators within oversight Key Performance Indicators and to use GSCM metrics to assess the holistic sustainability maturity of each contractor, with clear linkages to fiscal incentives, contract extensions, or recognition programs. Conceptually, this reinforces the idea of GSCM as a higher-order capability that bundles operational, environmental, and social routines to generate complementary improvements in economic, environmental, and social performance, rather than forcing firms to choose between them.

The most significant contribution of this study is the confirmation of the moderating role of Risk Management (H5, H6, and H7). The results indicate that a firm’s RM approach significantly strengthens the positive relationship between all three strategic drivers and GSCM adoption. This finding empirically validates the framework proposed by Brustbauer [22], which distinguishes between passive (defensive) and active (offensive) risk management orientations. The implementation of GSCM in the high-stakes oil and gas sector is a proactive, strategic investment with long-term benefits but considerable short-term risks and costs [72,73,74]. In a firm with a passive RM approach, such an initiative might be viewed as an unnecessary risk and thus be stifled [77,78]. However, a firm with an active ERM framework perceives risk management as a tool to create and protect value [79,80,81]. Such a firm is more likely to recognize the long-term strategic advantages of GSCM—such as enhanced reputation, improved social license to operate, and future-proofing against regulations—and will, therefore, create an organizational environment that empowers leadership, innovation, and strategic IT to translate their potential into a fully implemented GSCM program [82,83,84]. This confirms that a mature RM capability acts not as a constraint, but as a critical enabler for strategic sustainability initiatives.

The moderating pattern observed in H5–H7 refines existing GSCM models by showing that the strength of the links between strategic drivers and GSCM is contingent on how risk is framed and governed within the firm. When RM is more active and opportunity-oriented, the effects of IT-BSA, TL, and PI on GSCM become stronger; when RM is more passive and defensive, these effects are likely to be attenuated. In this way, RM can be interpreted as a higher-order governance mechanism that activates or dampens the influence of other capabilities on green supply chain adoption.

In the Indonesian upstream oil and gas sector, these findings also speak to the governance role of SKK Migas. Because contractors operate under a common regulatory and contractual framework, system-level interventions by SKK Migas can shape the configuration of IT-BSA, TL, PI, RM, and GSCM beyond individual firm boundaries. For example, alignment requirements in reporting and digital platforms can indirectly strengthen IT-BSA; leadership expectations and competency frameworks can support TL; and joint innovation agendas and technology roadmaps can foster PI. At the same time, risk-based supervision and guidance influence how RM is framed and operationalised across contractors. The moderated structure identified in this study, therefore, suggests that SKK Migas is not only a compliance-oriented regulator, but also a potential meta-governor of capabilities that underpin GSCM and, ultimately, SP in the Indonesian oil and gas industry.

Collectively, these findings provide robust support for the application of the RBV in explaining the development of sustainable supply chains. The results empirically demonstrate that strategic assets such as IT-Business Strategy Alignment, Transglobal Leadership, and Product Innovation function as valuable internal resources and capabilities that form the building blocks for advanced environmental strategies. The significant moderating effect of Risk Management highlights its crucial role as a dynamic capability, governing how other resources are effectively orchestrated to build a complex, higher-order GSCM capability. The final positive impact of GSCM on Sustainable Performance confirms the central tenet of RBV: that the unique bundling and strategic deployment of internal resources and capabilities lead to a sustained competitive advantage, which in this context is manifested as superior environmental, economic, and social outcomes [27,29]. Taken together, this study offers a more interpretative and theoretically grounded account of how resource endowments, risk governance, and GSCM jointly contribute to sustainability performance in high-risk industries, providing insights that are transferable beyond the specific empirical context.

5.2. Theoretical and Managerial Implications

From a theoretical perspective, this study extends resource-based explanations of sustainability by showing how IT–Business Strategy Alignment, Transglobal Leadership, and Product Innovation operate as complementary internal resources that jointly support the development of GSCM capabilities and, in turn, Sustainable Performance. By explicitly modeling Risk Management as a moderating variable, the study also adds a risk-based view to the GSCM literature, highlighting that the conversion of strategic resources into green supply chain capabilities is contingent on the firm’s risk management posture. This integrated framework enhances the understanding of how strategic drivers, risk governance, and GSCM interact in high-risk and capital-intensive industries, while remaining conceptually transferable to organizations in other sectors and institutional settings.

From a managerial perspective, the findings suggest that GSCM should be treated as a strategic capability rather than a purely compliance-oriented activity. Managers are encouraged to deliberately invest in three mutually reinforcing drivers: aligning IT and business strategies to support environmental monitoring and supply chain transparency; developing leadership competencies that can mobilize diverse stakeholders around sustainability goals; and fostering product innovation that systematically reduces the life-cycle environmental impacts of products and processes. At the same time, risk management needs to be positioned as a strategic enabler of sustainability, where an active and integrated approach legitimizes and supports long-term green investments instead of constraining them. Organizations that embed these elements into their strategic planning and governance systems are better equipped to translate GSCM practices into improved economic, environmental, and social performance, making the practical implications of this model relevant for a wide range of firms beyond the specific empirical context of this study.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations that suggest directions for future research. First, the analysis is based on cross-sectional survey data from PSC contractors under SKK Migas in the production stage, which strengthens internal validity but limits generalizability to other segments, countries, or high-risk industries. Future studies could replicate and extend the model in different institutional and sectoral contexts. Second, the use of self-reported data from a single respondent per firm may introduce common method bias despite the procedural and statistical remedies applied; subsequent research could employ multi-respondent, longitudinal, or mixed-method designs. Third, the PLS-SEM model focuses on the core constructs derived from RBV and a risk-based view and does not include additional control variables such as firm size, type of operation, or managerial experience. Future research is encouraged to incorporate these controls and/or conduct multi-group analyses to more finely capture contextual influences on the relationships between strategic drivers, risk management, GSCM, and Sustainable Performance.

6. Conclusions

This study empirically validates a model explaining the drivers of GSCM and its impact on Sustainable Performance in Indonesia’s oil and gas industry. It confirms that IT & Business Strategy Alignment, Transglobal Leadership, and Product Innovation are key drivers of GSCM adoption, which in turn boosts Sustainable Performance. The research also highlights that proactive Risk Management plays a crucial moderating role, strengthening the influence of strategic drivers on GSCM implementation, positioning risk management as a strategic enabler for sustainability in high-risk industries.

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. The research is context-specific, focusing solely on PSC contractors in the upstream oil and gas sector of a single developing country, Indonesia. This may limit the generalizability of the findings to other industries or to developed economies. The study also relies on cross-sectional data collected from a single respondent per firm at one point in time, which raises the possibility of common method bias and constrains the ability to draw strong causal inferences.

The limitations of this study open several avenues for future research. Scholars are encouraged to replicate and extend the model in other industrial sectors (e.g., mining, chemicals) and in different geographical and institutional contexts to assess the robustness and transferability of the findings. Future studies could also employ multi-respondent, longitudinal, or mixed-method designs to obtain a richer and more robust picture of the underlying relationships. In addition, subsequent research may incorporate control variables such as firm size, type of operation, or managerial experience, and/or conduct multi-group analyses to more finely capture contextual influences on the relationships between strategic drivers, RM, GSCM, and SP.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P.S., K.H., C.R.D. and Z.Z.; methodology, A.P.S., K.H., C.R.D. and Z.Z.; software, A.P.S.; validation, A.P.S.; formal analysis, A.P.S.; investigation, A.P.S., K.H., C.R.D. and Z.Z.; data curation, A.P.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P.S.; writing—review and editing, A.P.S., K.H., C.R.D. and Z.Z.; visualization, A.P.S.; supervision, K.H., C.R.D. and Z.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of Universitas Brawijaya (Approval No. 06215/UN10.F0301/B/PP/2025) on 14 August 2025. All procedures complied with relevant guidelines, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants received standardized information about the study and provided verbal informed consent prior to participation. The consent process emphasized voluntariness and anonymity.

Data Availability Statement

To protect participant confidentiality, the data are unavailable publicly. Access may be granted to qualified researchers upon reasonable request to alexstendel@student.ub.ac.id (corresponding author).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- McMullen, J.S.; Shepherd, D.A. Entrepreneurial Action And The Role Of Uncertainty In The Theory Of The Entrepreneur. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 132–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Lu, L.; Liu, J.; Zhou, J.; Wang, X.; Li, F. A Study of the Factors Contributing to the Impact of Climate Risks on Corporate Performance in China’s Energy Sector. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, I.; Zailani, S.; Rahman, M.K. Predicting employees’ engagement in environmental behaviours with supply chain firms. Manag. Res. Rev. 2021, 44, 825–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.; Holt, D. Do green supply chains lead to competitiveness and economic performance? Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2005, 25, 898–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.F.; Karadas, G. Managers’ Perceptions Regarding the Effect of Leadership on Organizational Performance: Mediating Role of Green Supply Chain Management Practices. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 21582440211018686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwish, S.; Shah, S.M.M.; Ahmed, U. The role of green supply chain management practices on environmental performance in the hydrocarbon industry of Bahrain: Testing the moderation of green innovation. Uncertain Supply Chain. Manag. 2021, 9, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, H.U.; Zahid, M.; Ullah, M.; Al-Faryan, M.A.S. Green supply chain management and firm sustainable performance: The awareness of China Pakistan Economic Corridor. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 414, 137502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, A.; Bao, Y.; Nabi, N.; Dulal, M.; Asha, A.A.; Islam, M. Impact of Strategic Orientations on the Implementation of Green Supply Chain Management Practices and Sustainable Firm Performance. Sustainability 2021, 13, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Ikram, A.; Rehan, M.F.; Ahmad, A. Going green: Impact of green supply chain management practices on sustainability performance. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 973676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, F.H.; Dunnan, L.; Jamil, K.; Mustafa, S.; Atif, M.; Gul, R.F.; Guangyu, Q. Mediating Role of Green Supply Chain Management Between Lean Manufacturing Practices and Sustainable Performance. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 810504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hajri, A.; Hamouda, A.M.; Abdella, G.M. Sustainability-Based Strategic Framework for Digital Transformation in the Oil and Gas Industry. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 52114–52133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jermsittiparsert, K.; Srihirun, W. Leadership in supply chain management: Role of gender as moderator. Int. J. Innov. Creat. Chang. 2019, 5, 448–466. [Google Scholar]

- Pujiono, B.; Setiawan, M.; Sumiati; Wijayanti, R. The effect of transglobal leadership and organizational culture on job performance—Inter-employee trust as Moderating Variable. Int. J. Public Leadersh. 2020, 16, 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Najmi, A. Developing and analyzing framework for understanding the effects of GSCM on green and economic performance. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2018, 29, 740–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunarya, E.; Nur, T.; Rachmawati, I.; Suwiryo, D.H.; Jamaludin, M. Antecedents of green supply chain collaborative innovation in tourism SMEs: Moderating the effects of socio-demographic factors. Uncertain Supply Chain Manag. 2023, 11, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Seman, N.A.; Govindan, K.; Mardani, A.; Ozkul, S.; Zakuan, N.; Saman, M.Z.M.; Hooker, R.E. The mediating effect of green innovation on the relationship between green supply chain management and environmental performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadge, A.; Mogale, D.; Bourlakis, M.; Maiyar, L.M.; Moradlou, H. Link between Industry 4.0 and green supply chain management: Evidence from the automotive industry. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 169, 108303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Luthra, S.; Joshi, S.; Kumar, A.; Jain, A. Green logistics driven circular practices adoption in industry 4.0 Era: A moderating effect of institution pressure and supply chain flexibility. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 383, 135284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.T.; Dang, W.V. Environmental commitment and firm financial performance: A moderated mediation study of environmental collaboration with suppliers and CEO gender. Int. J. Ethic-Syst. 2021, 37, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuen, A.; Feiler, P.F.; Teece, D.J. Dynamic capabilities in the upstream oil and gas sector: Managing next generation competition. Energy Strat. Rev. 2014, 3, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbane, B. Small business research: Time for a crisis-based view. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2010, 28, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brustbauer, J. Enterprise risk management in SMEs: Towards a structural model. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2016, 34, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manumayoso, B.; Utami, A.D.R.K.; Gabunia, L. Oil and Gas Fiscal Term Regulations Based on Ecological Justice. J. Sustain. Dev. Regul. Issues 2024, 2, 233–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagoda, K.; Wojcik, P. Implementation of risk management and corporate sustainability in the Canadian oil and gas industry. Account. Res. J. 2019, 32, 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.M. The Resource-Based Theory of Competitive Advantage: Implications for Strategy Formulation. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1991, 33, 114–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Chen, P.-K. Enhancing the resilience of sustainable supplier management through the combination of win–win lean practices and auditing mechanisms—An analysis from the resource-based view. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 962008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Rodrigues, V.S. Synergetic effect of lean and green on innovation: A resource-based perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 219, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibin, K.T.; Dubey, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Hazen, B.; Roubaud, D.; Gupta, S.; Foropon, C. Examining sustainable supply chain management of SMEs using resource based view and institutional theory. Ann. Oper. Res. 2020, 290, 301–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luftman, J.; Lyytinen, K.; ben Zvi, T. Enhancing the measurement of information technology (IT) business alignment and its influence on company performance. J. Inf. Technol. 2017, 32, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatraman, N. The Concept of Fit in Strategy Research: Toward Verbal and Statistical Correspondence. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 423–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luftman, J.N.; Lewis, P.R.; Oldach, S.H. Transforming the enterprise: The alignment of business and information technology strategies. IBM Syst. J. 1993, 32, 198–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaczny, T. Is an alignment between business and information technology the appropriate paradigm to manage IT in today’s organisations? Manag. Decis. 2001, 39, 797–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weill, P.; Broadbent, M. Leveraging the New Infrastructure: How Market Leaders Capitalize on Information Technology; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, J.C.; Venkatraman, H. Strategic alignment: Leveraging information technology for transforming organizations. IBM Syst. J. 1999, 38, 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quick, J.C.; Nelson, D.L. Leadership development: On the cutting edge. Consult. Psychol. J. Pr. Res. 2008, 60, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, J.A.; Kanungo, R.N.; Menon, S.T. Charismatic leadership and follower effects. J. Organ. Behav. 2000, 21, 747–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soete, L.; Freeman, C. The Economics of Industrial Innovation; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Alegre, J.; Lapiedra, R.; Chiva, R. A measurement scale for product innovation performance. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2006, 9, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag, S.; Dhamija, P.; Bryde, D.J.; Singh, R.K. Effect of eco-innovation on green supply chain management, circular economy capability, and performance of small and medium enterprises. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 141, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvey, S.S.; Odei-Mensah, J. The measurements and performance of enterprise risk management: A comprehensive literature review. J. Risk Res. 2023, 26, 778–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunziker, S. Setting up Enterprise Risk Governance. In Enterprise Risk Management: Modern Approaches to Balancing Risk and Reward; Springer Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2021; pp. 165–208. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.K. The Impact of CEO Characteristics on Corporate Sustainable Development. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2013, 20, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radner, R.; Shepp, L. Risk vs. profit potential: A model for corporate strategy. J. Econ. Dyn. Control. 1996, 20, 1373–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyt, R.E.; Liebenberg, A.P. The Value of Enterprise Risk Management. J. Risk Insur. 2011, 78, 795–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hoek, R.I. From reversed logistics to green supply chains. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 1999, 4, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J. Relationships between operational practices and performance among early adopters of green supply chain management practices in Chinese manufacturing enterprises. J. Oper. Manag. 2004, 22, 265–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14001:2015; Environmental Management Systems—Requirements with Guidance for Use. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J.; Lai, K.-H. Confirmation of a measurement model for green supply chain management practices implementation. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2008, 111, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, M.-C.; Tai, P.-Y.; Chu, C.-Y. Developing a smart green supplier risk assessment system integrating natural language processing and life cycle assessment based on AHP framework: An empirical study. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 207, 107671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chardine-Baumann, E.; Botta-Genoulaz, V. A framework for sustainable performance assessment of supply chain management practices. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2014, 76, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahani, P.; Meier, C.; Wilke, J. Digital Supply Chain Management Agenda for the Automotive Supplier Industry. In Shaping the Digital Enterprise; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmaker, C.L.; Al Aziz, R.; Ahmed, T.; Misbauddin, S.; Moktadir, A. Impact of industry 4.0 technologies on sustainable supply chain performance: The mediating role of green supply chain management practices and circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 419, 138249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confente, I.; Scarpi, D.; Russo, I. Marketing a new generation of bio-plastics products for a circular economy: The role of green self-identity, self-congruity, and perceived value. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 112, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, M.; Germani, F.; Grimaldi, M.; Radicic, D. Policy mix or policy mess? Effects of cross-instrumental policy mix on eco-innovation in German firms. Technovation 2022, 117, 102194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Ali, S.; Khan, Z. Eco-innovation and energy productivity: New determinants of renewable energy consumption. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 271, 111028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, R.; Mansouri, S.A.; Aktas, E. The relationship between green supply chain management and performance: A meta-analysis of empirical evidences in Asian emerging economies. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 183, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, S.; Nilashi, M.; Almulihi, A.; Alrizq, M.; Alghamdi, A.; Mohd, S.; Ahmadi, H.; Azhar, S.N.F.S. Green Supply Chain Management practices and impact on firm performance: The moderating effect of collaborative capability. Technol. Soc. 2021, 67, 101766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajan, M.P.; Shalij, P.R.; Ramesh, A.; Augustine, P.B. Lean manufacturing practices in Indian manufacturing SMEs and their effect on sustainability performance. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2017, 28, 772–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meulbroek, L.K. Integrated risk management for the firm: A senior manager’s guide. J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 2002, 14, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagach, D.; Warr, R. The Characteristics of Firms That Hire Chief Risk Officers. J. Risk Insur. 2011, 78, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S.; Greenwood, M.; Prior, S.; Shearer, T.; Walkem, K.; Young, S.; Bywaters, D.; Walker, K. Purposive sampling: Complex or simple? Research case examples. J. Res. Nurs. 2020, 25, 652–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepeda-Carrion, G.; Cegarra-Navarro, J.-G.; Cillo, V. Tips to use partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) in knowledge management. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N.; Lynn, G.S. Stevens Institute of Technology Lateral Collinearity and Misleading Results in Variance-Based SEM: An Illustration and Recommendations. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13, 546–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Matthews, L.M.; Matthews, R.L.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. Int. J. Multivar. Data Anal. 2017, 1, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latan, H. PLS Path Modeling in Hospitality and Tourism Research: The Golden Age and Days of Future Past. In Applying Partial Least Squares in Tourism and Hospitality Research; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2018; pp. 53–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common Method Bias in PLS-SEM. Int. J. e-Collaboration 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. Commentary: Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. MIS Q. 1998, 22, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Trujillo-Gallego, M.; Sarache, W.; Jabbour, A.B.L.d.S. Digital technologies and green human resource management: Capabilities for GSCM adoption and enhanced performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 249, 108531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narimissa, O.; Kangarani-Farahani, A.; Molla-Alizadeh-Zavardehi, S. Drivers and barriers for implementation and improvement of Sustainable Supply Chain Management. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandil, T.T. Green Human Resource Competency Mechanisms: Moderator Role Between Green Supply Chain and the Oil and Gas Industry Environmental Performance. Vision J. Bus. Perspect. 2023, 09722629231180684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atstāja, D.; Mukem, K.W. Sustainable Supply Chain Management in the Oil and Gas Industry in Developing Countries as a Part of the Quadruple Helix Concept: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Cheah, J.-H.; Lim, X.-J.; Ramachandran, S. Why does “green” matter in supply chain management? Exploring institutional pressures, green practices, green innovation, and economic performance in the Chinese chemical sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 427, 139182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Ullah, M.; Wang, L.; Ullah, F.; Khan, R. Green supply chain management practices and triple bottom line performance: Insights from an emerging economy with a mediating and moderating model. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 357, 120575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, J.; Hallstedt, S.I. Company Risk Management in Light of the Sustainability Transition. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciocoiu, C.N.; Radu, C.; Colesca, S.E.; Prioteasa, A. Exploring the link between risk management and performance of MSMEs: A bibliometric review. J. Econ. Surv. 2025, 39, 1523–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S. The role of knowledge and organizational support in explaining managers’ active risk management behavior. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2019, 32, 345–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J. The effect of enterprise risk management on corporate risk management. Finance Res. Lett. 2023, 55, 103950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Lv, W.; Wang, J. The impact of digital transformation on firm performance: A perspective from enterprise risk management. Eurasian Bus. Rev. 2024, 14, 369–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimon, D.; Madzík, P. Standardized management systems and risk management in the supply chain. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2019, 37, 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Farnoosh, A.; McNamara, T. Risk analysis in the management of a green supply chain. Strat. Change 2021, 30, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.; Rasheed, R.; Ngah, A.H.; Jayaratne, M.D.R.P.; Rahi, S.; Tunio, M.N. Role of information processing and digital supply chain in supply chain resilience through supply chain risk management. J. Glob. Oper. Strat. Sourc. 2024, 17, 429–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.