Abstract

The transition toward sustainable transport systems requires decision-support tools that help organizations navigate strategic choices under environmental, economic, and operational constraints. This study introduces the Holistic Multi-Period Fleet Planning Problem (HMPFPP), a nonlinear optimization model designed to support long-term, sustainability-oriented fleet modernization. The model integrates investment costs, operational performance, emission limits, and dynamic demand into a unified analytical framework, enabling organizations to assess the long-term consequences of their decisions. A notable feature of the HMPFPP is the inclusion of outsourcing as a strategic option, which expands the decision space and helps maintain service performance when internal fleet capacity is constrained. An illustrative ten-year scenario demonstrates that the model generates non-uniform but cost-efficient transition pathways, in which legacy vehicles are gradually replaced by cleaner technologies, and temporary fleet downsizing can be optimal during low-demand periods. Outsourcing is activated only when joint emission and budget constraints make fully internal service provision infeasible. Across the tested instance, the HMPFPP is solved within seconds on standard hardware, confirming its computational tractability for exploratory planning. Taken together, these results indicate that data-driven optimization based on the HMPFPP can provide transparent and robust support for sustainable fleet management and transition planning.

1. Introduction

The global imperative to mitigate climate change has placed significant pressure on all sectors of the economy to decarbonize, with heavy-duty commercial freight transport among the most challenging areas for technological transformation. The logistics sector, which is still heavily reliant on fossil-fuel-powered vehicles, faces a complex transition toward a sustainable fleet of diverse new-energy technologies, such as battery-electric and hydrogen-powered vehicles. Designing this transition requires long-term fleet renewal strategies that balance economic viability with financial constraints, evolving policy frameworks, and the dynamic nature of modern energy systems. Effectively managing this replacement process is essential for achieving corporate sustainability goals and aligning business strategies with the broader shift toward clean energy and low-carbon operations.

The main motivation of this study is to support decision-makers in navigating this increasingly complex transition landscape. Organizations must simultaneously evaluate technological alternatives, comply with tightening emission regulations, identify viable investment trajectories, and ensure continuity of service provision under dynamic demand conditions. Existing approaches typically address these aspects in isolation, creating a need for an integrated analytical model that captures the interplay among operational, environmental, economic, and strategic factors across multiple time periods.

The existing literature is dominated by multi-period Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) models that schedule fleet replacements under explicit policy and operational constraints, as exemplified by [1]. These models typically aim to minimize the total cost of ownership while satisfying service demand and regulatory requirements. Although they offer valuable insights, they still have essential limitations. First, many models do not incorporate dynamic grid decarbonization trajectories, which are critical for evaluating the lifecycle emissions of electric vehicles [2]. Second, they often offer limited mechanisms to address policy uncertainty, despite its central role in long-term investment decisions [3]. Third, most existing frameworks focus on public transit buses or light-duty vehicles rather than the operational realities of heavy-duty freight transport [4,5]. Among models aligned with policy-based fleet replacement, [1] offers the strongest reference point, complemented by [6,7].

To address these limitations, we develop an approach inspired by the well-established MARKAL (MARKet ALlocation) model [8,9], a multi-period nonlinear optimization framework widely used for energy system analysis. MARKAL represents an energy system through a Reference Energy System (RES), capturing flows from primary resources to end-use demand via various technologies [10]. The model ensures that energy demand is met in each period while accounting for technological characteristics, emissions, and economic parameters. Its flexibility and systemic perspective make it well-suited to sector-specific planning problems, including transport electrification [11,12,13].

Building on these conceptual foundations, this study introduces the Holistic Multi-Period Fleet Planning Problem (HMPFPP). The proposed model couples gradual technology transition with partial demand outsourcing, representing both legacy and new-energy vehicle technologies through their technical and economic attributes, including emissions, purchase and operating costs, and efficiency. Service demand activates the available technological capacities in each period, and the model determines the optimal number of legacy and new-technology vehicles subject to financial, environmental, and operational constraints. By explicitly modeling the trade-off between internal fleet operation and outsourcing to external service providers, the HMPFPP reflects realistic strategic choices faced by logistics operators navigating the energy transition. The model ensures service provision while enabling progressive replacement of older technologies with cleaner alternatives.

Beyond its methodological contribution, the study engages with the broader sustainability challenges inherent in long-term fleet modernization. The transition toward cleaner technologies is not merely a technological substitution, but a systemic transformation shaped by interdependencies between emission trajectories, investment capacity, regulatory constraints, evolving energy-system characteristics, and the resilience of service provision. By capturing these interconnections within a multi-period decision-support framework, the HMPFPP offers an integrated perspective on how organizations can design feasible, economically justified, and environmentally aligned fleet transition pathways, thereby contributing to the analytical foundations needed to navigate the structural complexities of sustainable mobility transitions. This work also aligns with the central themes of sustainability research concerning low-carbon transitions in transportation systems. Prior studies have shown that fleet modernization, emission-constrained decision-making, and policy-driven adoption of clean technologies constitute significant challenges for sustainable transport planning. Research in this area, including [1,14,15], highlights the need for analytical tools that integrate environmental constraints into operational and investment decisions. The HMPFPP contributes to this research stream by providing a system-level framework capable of evaluating long-term decarbonization pathways under technological, regulatory, and economic pressures. The importance of this study for sustainability lies in its ability to operationalize long-term decarbonization strategies in the transportation sector. By explicitly linking fleet evolution with emission caps, budget constraints, and technological characteristics, the model enables organizations to quantify the environmental implications of different transition pathways. It not only identifies cost-effective modernization plans but also reveals how regulatory instruments and financial limitations shape achievable sustainability outcomes. In doing so, the HMPFPP strengthens the analytical basis for designing realistic, evidence-based, and policy-aligned decarbonization strategies for heavy-duty transport and supports the development of cleaner, more resilient transport systems.

The research questions addressed in this paper are as follows:

- RQ01: How can a holistic multi-period optimization model be developed to integrate financial, operational, regulatory, and strategic decisions for heavy-duty fleet transition?

- RQ02: How can the optimal mix of technologies (legacy, electric, hydrogen, etc.) be determined under investment limitations and evolving emission regulations?

- RQ03: How does the strategic option of outsourcing transport services influence fleet replacement strategies and sustainability outcomes?

The proposed HMPFPP model addresses these gaps through a multi-perspective optimization structure that simultaneously considers economic, operational, and environmental objectives. Its nonlinear nature—driven by discounted costs and interdependencies between investment and operational decisions—captures long-term strategic behavior while remaining computationally tractable using standard NLP/MINLP solvers such as LINGO. This makes the HMPFPP a practical exploratory tool for scenario analysis supporting policy and investment decision-making.

The main contribution of this paper is the development of a comprehensive decision-support model, HMPFPP, that unifies decision dimensions typically addressed separately in the literature [15]. The HMPFPP integrates regulatory, financial, operational, and technological considerations within a unified, coherent nonlinear optimization model. By doing so, it provides a structured way to assess how investment limitations, emission constraints, and service requirements jointly shape sustainable fleet modernization pathways. A further contribution is the explicit incorporation of outsourcing as a strategic option. While outsourcing is widely used in practice, it is rarely modeled in fleet transition optimization. Its inclusion expands the decision space, allowing organizations to evaluate how external service provision interacts with emission limits, budget constraints, and internal fleet capacity. This feature supports more realistic and operationally grounded sustainability-oriented decision-making. In methodological terms, the HMPFPP builds on the conceptual foundations of MARKAL to develop a transport-sector-focused formulation that remains computationally tractable while capturing the system’s dynamic behavior. This enhances its suitability for scenario-based analysis and for exploring long-term planning decisions under evolving policy and market conditions. Overall, the HMPFPP contributes to sustainable management by providing a transparent, data-driven approach that helps organizations understand the multi-period implications of their decisions and design feasible, economically viable, and environmentally aligned fleet transition strategies.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related literature on fleet transition, multi-period optimization, and energy system modeling. Section 3 introduces the conceptual formulation of the HMPFPP model, and Section 4 presents its nonlinear program with detailed notation and constraints. Section 5 provides an illustrative example demonstrating the model’s behavior under dynamic demand, emission caps, and financial limitations. Section 6 concludes the study and outlines directions for future research.

2. Related Papers

Recent research on sustainable transportation increasingly emphasizes the need for structured methods that support long-term fleet modernization in response to technological, regulatory, and market-driven changes. Studies in both public transit and urban freight demonstrate that transitioning to low- and zero-emission powertrains requires navigating complex decisions about technology adoption, replacement timing, infrastructure readiness, and compliance with environmental policies. The literature highlights that these decisions are typically addressed through multi-period optimization models, most often based on Mixed-Integer Linear Programming, which aim to minimize lifecycle costs while satisfying operational and emission-related constraints. However, despite substantial methodological progress, existing frameworks frequently treat key decision layers—such as investment planning, operational viability, regulatory alignment, and strategic flexibility—as separate or only loosely connected. This fragmentation highlights the need for more comprehensive decision-support models that can capture the full complexity of fleet transition in rapidly evolving energy systems.

An important complementary research stream concerns the relationship between energy system evolution, sustainability goals, and decision-support techniques. Decarbonization efforts increasingly require models capable of addressing technological uncertainty, renewable energy integration, and long-term environmental risk. Recent studies show that disruptive technological change in the energy sector imposes new forms of strategic uncertainty that must be addressed with analytical tools [16]. To support technology evaluation and sustainability-oriented investment decisions, MCDM methods have been widely applied in renewable energy planning [17,18,19]. Extensions incorporating neutrosophic logic provide improved robustness when dealing with imprecise or ambiguous data—an important feature in early stage sustainability-oriented decisions [20,21]. Collectively, these contributions highlight the importance of decision-support models that integrate environmental performance, technological characteristics, and investment constraints—principles that align closely with the motivation behind the HMPFPP.

A vast and expanding body of literature has emerged to address the core optimization challenge of sustainable fleet transition, with MILP constituting the dominant methodological approach. MILP models are adept at co-optimizing multiple decision variables, including vehicle acquisition and retirement schedules, fleet composition, and depot charging strategies [7,14,22,23,24,25,26,27]. Their primary strength lies in identifying cost-optimal pathways within budgetary constraints and under policy constraints such as emission caps or Zero-Emission Zone (ZEZ) deadlines. Foundational and recent work in the public transit sector demonstrates the maturity of MILP approaches for optimizing bus fleet electrification [22,23,24,28,29], and more recently, these models have been extended to urban freight and commercial vehicle fleets [14,30,31].

Beyond single-objective formulations, multi-objective optimization frameworks capture trade-offs between economic, environmental, and operational goals. These models generate Pareto frontiers that help decision-makers balance competing objectives such as TCO and greenhouse gas emissions, reflecting the inherently multi-criteria nature of fleet transition planning [32,33,34]. This trend illustrates a shift from purely cost-minimizing models to formulations that explicitly embed sustainability considerations.

Uncertainty remains a pervasive challenge in long-term planning. In response, deterministic MILP models have been extended to stochastic programming and robust optimization to ensure resilience under uncertain cost, energy-price, or policy trajectories [28,35]. Complementary approaches, such as real options analysis, reinterpret fleet investment as flexible, adaptive decision sequences [36,37]. Scenario-based planning further supports the evaluation of regulatory and market uncertainty [30,38,39].

As the transition toward electric mobility accelerates, infrastructure co-planning has become a key research theme. Increasingly, studies emphasize that fleet replacement and charging infrastructure deployment must be co-optimized to ensure feasibility under operational and grid constraints [29,40,41]. More advanced models adopt bi-level formulations to capture interactions between fleet operators and electric utilities [29].

Environmental dimensions of fleet transition have also matured. Earlier work focused on tailpipe emissions, whereas recent studies incorporate Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) covering vehicle production, operation, and end-of-life [24,31,42,43]. Integrating LCA into optimization remains challenging due to nonlinearities and data uncertainty, but it provides a more comprehensive representation of environmental impacts. MCDM/A methods such as AHP and TOPSIS complement these models by enabling inclusion of qualitative sustainability criteria and stakeholder concerns [42].

Despite these advances, the literature exhibits a persistent sectoral imbalance: public transit fleets have received far more attention than freight logistics, where operational heterogeneity and distributed decision-making complicate model design [14,30,31]. Even advanced strategic models—such as portfolio-based approaches [6] or policy-driven fleet replacement formulations [1]—tend to emphasize prescriptive scheduling rather than managerial flexibility.

The key research gap this paper addresses is the lack of a truly integrative decision-support framework. Most existing studies isolate major decision layers such as replacement scheduling, infrastructure planning, logistics, and regulatory compliance. Even the most policy-aligned models [1] do not explicitly account for the strategic role of outsourcing, despite its influence on costs, emissions, and operational resilience. A comprehensive model should integrate these dimensions within a single, multi-period structure to reconcile policy constraints, operational feasibility, and financial limitations [24,29]. Additional gaps arise in the inconsistent treatment of interacting policy instruments—including carbon taxes, scrappage incentives, and differentiated subsidies—which remain underrepresented in optimization models [23,28,36,38,44].

Finally, strategic flexibility remains insufficiently represented. Few studies model the managerial decision of balancing internal fleet resources with outsourced service flows, despite their practical relevance for risk management and cost-efficiency. In summary, although the literature provides robust tools for specific facets of fleet transition, a holistic model that jointly addresses financial, operational, regulatory, technological, and strategic dimensions remains lacking. Emerging advances in approximate dynamic programming [4] and digital decision-support systems [45,46] point to more adaptive and data-driven approaches, but integrating these strands into a cohesive optimization framework—such as the proposed HMPFPP—remains an essential step toward actionable decision support for sustainable fleet transition.

3. Holistic Multi-Period Fleet Planning Problem

The HMPFPP is formulated as a strategic-level decision problem. Its objective is to satisfy a known transport service demand in each planning period t, while minimizing the total discounted cost over the planning horizon, discounted to the decision point at rate .

To fulfill the required transport service k—representing resource, energy, or service categories (LOAD)—the operator must allocate adequate capacity in each period t from three potential sources:

- legacy vehicles of the old technology i, represented by decision variable ,

- newly acquired vehicles of the new technology j, represented by decision variable ,

- outsourced services from external service providers s, represented by variable , incurring a unit cost .

The parameter k does not explicitly appear in variables X and Y, as the technological categories i and j already encapsulate the service and resource characteristics associated with each vehicle type. The relationships between vehicle technologies and service or energy categories are defined at the parameter level via coefficients g and h, which specify the per-unit resource consumption or energy demand for each technology.

At the beginning of each planning period, the operator owns a stock of vehicles, (the legacy fleet), which can be used to meet part of the demand. At any time, the operator may sell a portion of legacy vehicles, purchase new-technology vehicles of either old or new technology, or outsource part of the demand to third-party providers. New-technology vehicles are assumed to be procured at the beginning of each period and become operational immediately. Vehicle sales occur at the end of each period.

Investment decisions are subject to budget constraints: for vehicles of the old technology and for those of the new technology. The proceeds from vehicle sales are reinvested, augmenting the respective budgets and for old and new technologies.

Each vehicle type is characterized by the following:

- purchase price (, ) and resale price (, ),

- fixed operating costs (, ) and variable operating costs (, ),

- maintenance costs per period (, ),

- fuel or energy demand per resource category k (, ),

- emissions of pollutants of type v (, ).

These parameters jointly determine the total lifecycle cost and environmental impact of each technology within the planning horizon.

The HMPFPP is inherently nonlinear due to discounted future costs and nonlinear interdependencies between investment and operational decisions across multiple periods. Despite this, it remains computationally tractable using optimization software that supports NLP/MINLP formulations, such as LINGO, which enables the derivation of feasible, practically meaningful solutions over realistic planning horizons. Alternatively, the problem can be reformulated as an MILP by linearizing nonlinear expressions via auxiliary variables and constraints. While this guarantees formal optimality proofs, it significantly increases model size and computational complexity. Consequently, the nonlinear formulation is preferred for early planning and scenario evaluation, whereas the linear reformulation is suited for applications requiring rigorous optimality verification.

4. Nonlinear Program for the Holistic Multi-Period Fleet Planning Problem

The following paragraphs provide a detailed explanation of all equations in the model, including the meaning of each constraint and its role in the decision structure, complementing the notation listed in Table 1. For the Holistic Multi-Period Fleet Planning Problem, the following nonlinear program was developed (1)–(28).

Table 1.

Notation used in the HMPFPP.

The objective function (1) minimizes the discounted total cost of operating and expanding the fleet over the planning horizon. It includes purchase components of fleet expansion for new and legacy vehicles ( and ), maintenance costs ( and ), fixed and variable operating costs (, , , ), and costs of external resource, energy, or service flows (). These expenditures are offset by revenues from the sale of legacy and new-technology vehicles ( and ). All monetary values are discounted using the factor to account for the time value of money. Constraint (2) ensures resource, energy, and service balance for each category k and period t. Total supply—comprising flows purchased from external service providers and net contributions from legacy and new technologies (outputs minus required inputs)—must satisfy the demand . Maintenance costs for legacy and new-technology vehicles are defined in Constraints (3) and (4) as proportional to the number of units in operation, using coefficients and . Constraint (5) enforces emission limits by requiring that total emissions generated by all operating technologies for each emission type v and period t do not exceed the allowable upper limit . Investment constraints (6) and (7) restrict, for each period t, the total purchase and maintenance costs for new and legacy technologies, respectively, ensuring that the available budgets and are not exceeded. Constraints (8) and (9) define total revenues from selling legacy and new-technology vehicles as the product of unit sale prices and the number of units sold in each period. Constraints (10) and (11) impose that no net purchase or sale of vehicles occurs in the initial period, i.e., the planning horizon begins without prior transactions. Initial fleet levels are enforced in Constraints (12) and (13), which define the number of legacy vehicles present at the beginning of the horizon and ensure that no new-technology vehicles are in operation at . Constraint (14) ensures that the combined capacity of all legacy and new-technology vehicles in each period meets the required service level . Constraints (15) and (16) define the purchase components of fleet dynamics ( and ) through piecewise expressions: these variables capture positive changes in fleet size relative to the previous period and equal zero when the fleet does not expand. These definitions introduce nonlinearity into the model by distinguishing between increases and non-increases in fleet size. Finally, Constraints (17)–(28) specify variable domains, including non-negativity, integrality of fleet size variables, non-negativity of cost and revenue variables, and real-valued domains for net purchase/sale variables ( and ).

5. Illustrative Example

In this section, we present an illustrative example designed to demonstrate the behavior of the Holistic Multi-Period Fleet Planning Problem (HMPFPP) under deliberately challenging conditions. The aim of this example is not to replicate a specific real-world case, but to demonstrate how the nonlinear model responds to complex interactions among emissions constraints, investment limits, outsourcing costs, and dynamically changing demand.

The numerical instance is constructed for a ten-year planning horizon, in which investment, operation, and modernization decisions are made annually. Computational experiments were conducted to evaluate the model’s solvability using standard, commonly available computing resources. The nonlinear model was implemented in the LINGO optimization environment (NLP/MINLP mode), and all computations were performed on a laptop equipped with an Intel® Core™ i7-4710HQ processor (2.50 GHz, 4 cores) and 16 GB RAM. The results confirm that the HMPFPP can be solved efficiently without dedicated high-performance computing infrastructure, supporting its applicability in practical decision-support systems.

5.1. Input Data for the Illustrative Example

The initial fleet consists of 10 legacy vehicles (), representing older technology with relatively high unit emissions () and higher variable () and fixed () operating costs. These vehicles can be progressively replaced with low-emission alternatives. In the numerical example, the parameter is assumed to vary across periods to reflect changes in the upstream electricity mix’s emission intensity. In the illustrative example, the emission factor of the new technology varies between 0.195 and 0.95 across the planning horizon. These values reflect time-dependent characteristics of the upstream energy mix rather than differences between multiple technologies. Even in periods with higher emission factors (e.g., 0.95), the new technology remains a lower-emission option relative to the legacy fleet (0.995), thereby preserving its role as the environmentally superior choice in the model. The unit purchase cost of new-technology vehicles is . Both old and new-technology cars can be sold, with unit resale prices of and , respectively, (constant across periods).

Although the unit cost of outsourced service flows was intentionally set to an extremely high value (10,000,000) to discourage its use, the model still resorts to external services beginning in period 6. Meanwhile, fuel or energy consumption is identical across both technologies (), isolating the impact of emissions and cost parameters on the optimization decisions. This behaviour is consistent with the structure of the HMPFPP: in this part of the horizon, the combination of emission limits, investment budgets, and rapidly increasing demand makes it infeasible to satisfy the entire service requirement using internal fleet resources alone. In such situations, outsourcing serves as a “last-resort” option that remains available despite its prohibitive cost. Thus, the appearance of outsourced service flow does not indicate that it is economically attractive, but rather that no feasible internal solution exists under the imposed regulatory and financial constraints. We also incorporate modernization costs for legacy vehicles, modeled through coefficients and . Investment budgets are limited to for new technology and for the legacy fleet. The environmental constraint imposes an upper limit on emissions in each period, , forcing a gradual reduction in high-emission vehicles in the fleet. Demand for transport services () varies substantially over the planning horizon, ranging from low-demand periods (e.g., ) to peaks of up to . Service provision efficiency is described by the parameters and , where, for instance, means that one new-technology vehicle covers one unit of demand. A discount factor of is applied throughout the entire horizon to reflect the time value of money. These data serve to illustrate the properties of the nonlinear HMPFPP model and the resulting optimal fleet transition path.

5.2. Results

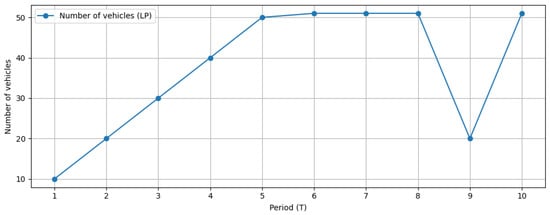

Figure 1 presents the evolution of the fleet size over the ten-year planning horizon. In the first years, the total number of vehicles increases systematically, reaching 51 units, which corresponds to the limit set by demand and the imposed budget and emission constraints. A noticeable drop in fleet size occurs in period 9, where the model reduces the fleet to 20 units. This behavior is a direct consequence of the significantly lower demand in that period (). Since maintaining a larger fleet would generate unnecessary operating and maintenance costs, the model reduces the active fleet to the minimum sufficient to meet demand while remaining within emission constraints. In the following period, when demand rises again, the model restores the required fleet size by repurchasing vehicles.

Figure 1.

Change in the number of vehicles over time.

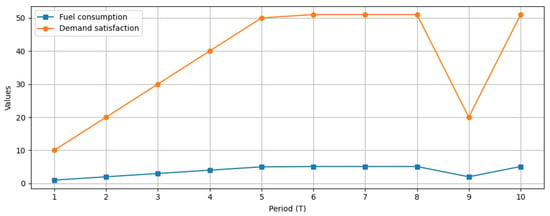

Figure 2 shows the relationship between fuel consumption and the satisfaction of transport demand. Initially, fuel consumption follows the increasing trend of demand. Following the introduction of new, more efficient technology, the same level of demand is met with lower fuel consumption, indicating an improvement in the fleet’s overall efficiency. This effect becomes evident from period 3 onward, when the share of new-technology vehicles in the fleet begins to dominate.

Figure 2.

Fuel consumption vs. demand satisfaction.

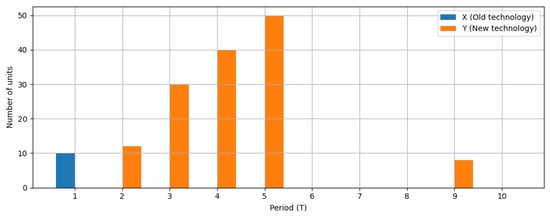

Figure 3 illustrates the structure of the fleet in terms of old and new technologies. On the horizon, almost all vehicles are still equipped with older, high-emission technologies. Due to the imposed emission limits and the increasing demand, the model gradually replaces legacy vehicles with new ones. The most intensive transition occurs in periods 2–5, when the emission constraint becomes binding and forces an accelerated adoption of low-emission technologies.

Figure 3.

Technology utilization over time.

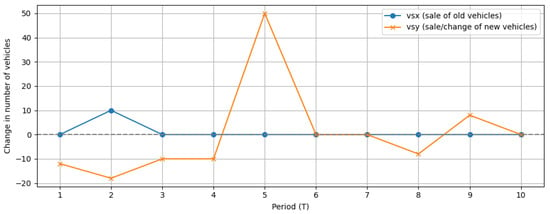

Figure 4 shows the changes in the fleet composition resulting from purchases and sales of vehicles. Positive values indicate an increase in the number of units, while negative values indicate a decrease. The irregularity of these changes reflects the model’s response to dynamically changing demand, emission limits, and investment budgets. The sharp reduction in the fleet in period 9 is consistent with the temporary decrease in demand and the aim of minimizing unnecessary maintenance and operational costs. Once demand increases again in period 10, the model responds by rebuilding the fleet through new purchases.

Figure 4.

Sales and fleet changes over time.

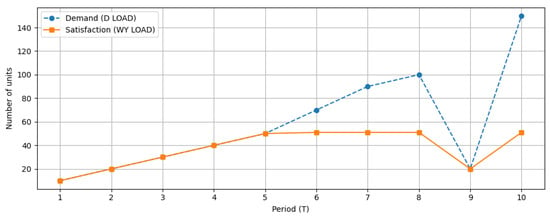

Finally, Figure 5 compares the demand for transport services with the actual level of service delivered by the fleet. In the early periods, demand is fully satisfied using internal resources. Beginning from period 6, part of the demand must be outsourced to external service providers. This is caused by the simultaneous effects of emission limits, budget constraints, and an insufficient fleet size relative to rapidly growing demand. The model uses outsourcing only when indispensable, as the cost of external services is significantly higher than the cost of internal production.

Figure 5.

Demand vs. satisfaction.

The temporary reduction in the fleet to 20 vehicles in period 9 is a rational result of the model’s cost-minimization structure. Since demand in this period is exceptionally low, using more cars would only increase costs without providing additional benefits. Selling unneeded vehicles reduces maintenance and operating expenditures, while increasing revenue from resale, both of which enhance the objective value. In the subsequent period, when demand rises sharply, the model rebuilds the fleet accordingly. This behavior is consistent with the economic interpretation of the decision variables and reflects the strategic flexibility embedded in the HMPFPP formulation.

5.3. Discussion

The illustrative example, based on a simulation with a ten-year planning horizon, demonstrates how the proposed HMPFPP model behaves under dynamically changing demand, evolving environmental constraints, and limited investment budgets. The experiment was intentionally designed as a demanding scenario: the legacy fleet consists of high-emission, cost-intensive vehicles. At the same time, the new technology offers improved cost–technical characteristics and substantially lower emissions. This configuration enables a meaningful examination of the model’s decision-making logic and its capacity to support long-term fleet transformation.

The simulation results indicate that, under the assumed parameters, the internal fleet fully satisfied transport demand until the fifth period. Beginning in period 2, the model initiated a systematic replacement of older units with new, more efficient vehicles. This modernization pathway highlights the HMPFPP’s ability to optimize fleet composition dynamically in response to operational needs, long-term cost implications, and regulatory constraints. In this regard, the illustrative example directly supports RQ01, demonstrating that the holistic, multi-period framework effectively integrates financial, operational, environmental, and strategic considerations into a unified decision-making mechanism for transitioning to a heavy-duty fleet. As demand increased substantially between periods 6 and 8, the combination of stringent emission limits and restricted investment budgets made it impossible for the internal fleet to meet the entire service requirement. Consequently, part of the demand was satisfied through outsourcing to an external service provider. This outcome provides a crucial insight into the model’s ability to assess the strategic role of outsourcing under environmental and budgetary constraints. It also supports RQ03, showing that the HOMPFPP can capture the trade-off between internal fleet expansion and the use of external services, thereby enabling more realistic and operationally robust planning. An exciting system response occurs in period 9. Due to a temporary decline in demand, the entire service requirement could again be met internally. The reduced workload, combined with previously implemented modernization actions, eliminated the need for outsourcing during that period. At the same time, the model found it economically beneficial to sell part of the legacy fleet and repurchase vehicles in the subsequent period. This behavior results from the interaction between discounting, emission constraints, and investment limits: postponing certain acquisitions to a later period can reduce the discounted cost while satisfying all constraints. Although such behavior may initially appear counterintuitive, it reflects economically consistent optimization logic. It suggests a direction for future refinement of investment-related constraints to avoid cyclical purchase–sale patterns in practical applications. In the final period, renewed emission pressure and high demand again necessitated limited outsourcing. Throughout the entire horizon, the model not only determined optimal acquisition and sale decisions but also identified opportunities for strategic intra-fleet substitutions—replacing legacy vehicles with lower-emission units when justified by regulatory and cost conditions. This detailed, period-specific optimization directly contributes to RQ02, providing insights into how the optimal technological mix evolves over multiple years when incorporating emission limits, cost structures, and investment restrictions.

Beyond fleet size and composition, the simulation generated valuable information on resource consumption patterns, such as fuel usage, and their relationship with demand fulfillment. The model can be extended to forecast internal and external demand for additional materials or energy carriers, further enhancing its applicability in comprehensive resource planning contexts. With a computation time of only 0.90 s, the proposed formulation proved highly efficient for the tested instance size, demonstrating that even nonlinear and multi-period configurations of the HMPFPP can be solved on standard computing hardware. This confirms the model’s practicality for use in industrial decision-support environments, where rapid evaluation of multiple scenarios is often required. It should also be emphasized that the illustrative example is constructed under deterministic assumptions: demand, investment budgets, emission caps, and technology-related costs are treated as known trajectories over the planning horizon. As a result, the reported fleet evolution and outsourcing patterns represent one baseline transition pathway conditional on these assumptions rather than a precise forecast. In practice, uncertainty in demand, energy prices, or regulatory stringency could materially affect results, for example, by shifting the timing of replacement decisions, altering the periods when outsourcing becomes necessary, or changing the relative shares of legacy and new technologies in the optimal fleet mix. From a methodological perspective, however, the HMPFPP is compatible with established uncertainty-handling frameworks. The same model structure can be embedded into scenario-based analyses (with alternative trajectories of demand, prices, or policy), extended to stochastic programming formulations with scenario trees, or reformulated as a robust optimization model that protects against adverse realizations of key parameters. In each case, the core decision logic of the HMPFPP remains unchanged, while the treatment of input data is adapted to capture different forms of uncertainty. Overall, the results validate the HMPFPP as a powerful tool for long-term, sustainability-oriented fleet transition planning and fully align with the central objectives and research questions guiding this study.

6. Conclusions

This study introduced the Holistic Multi-Period Fleet Planning Problem (HMPFPP), a nonlinear, MARKAL-inspired decision-support model designed to guide long-term transitions toward cleaner and more energy-efficient transport fleets. By integrating financial, operational, regulatory, and strategic dimensions within a single framework, the HMPFPP offers a unified perspective on how organizations can navigate the increasing complexity of sustainability-oriented fleet management.

Regarding organizational decision-making (RQ01), the model shows that fleet operators act as organizational energy consumers, with their investment and operational behaviors shaped simultaneously by capital constraints, regulatory pressures, and evolving service requirements. The holistic formulation captures how organizations adjust their decisions under sustainability-driven constraints, offering insights into the adoption trajectories of low- and zero-emission technologies. Regarding technology transition and fleet modernization (RQ02), the model illustrates how emission limits, lifecycle cost structures, and efficiency parameters collectively influence the gradual replacement of legacy vehicles with cleaner alternatives. The illustrative example demonstrates that transition pathways are not uniform; optimal strategies combine progressive replacement, selective retention of existing assets, and investment timing to balance economic feasibility and regulatory compliance. These results enhance our understanding of how emerging technologies diffuse into operational settings and how long-term decisions evolve under changing energy system conditions. The explicit representation of outsourcing as a strategic option (RQ03) highlights an increasingly relevant aspect of business innovation in the transport sector. The findings indicate that external service provision becomes necessary when emission caps, investment limits, and rising demand simultaneously constrain internal capacity. This feature distinguishes the HMPFPP from prior optimization models and reflects the growing importance of hybrid operational strategies that combine internal assets with market-based service provision.

Beyond the specific research questions, the HMPFPP offers several broader implications. It provides decision-makers with a transparent, data-driven tool for evaluating modernization strategies, investment requirements, and long-term service capacity—supporting more informed and accountable decisions in sustainability-oriented management. It also provides a basis for policy analysis by simulating how fleet operators respond to emission limits, discount rates, and budget constraints, thereby enabling the assessment of policy instruments and regulatory interventions. Furthermore, the model’s computational tractability and modular design make it suitable for integration into digital decision-support systems, opening opportunities for interdisciplinary applications across operations research, energy economics, and sustainable management.

Like many strategic optimization models, the HMPFPP is formulated in deterministic terms. Demand, cost parameters, and regulatory constraints are represented as known trajectories over the planning horizon, and the illustrative example is constructed under fixed assumptions about investment budgets, emission limits, and technology characteristics. This simplification is deliberate: the model is intended as a strategic-level planning tool that provides a transparent baseline for analyzing long-term fleet transition paths under specified policy and market conditions. As such, the results should be interpreted as indicative of structural relationships between emissions, costs, and fleet composition rather than as exact forecasts. In real-world applications, fluctuations in demand, energy prices, or regulatory requirements may cause deviations from the model-identified nominal pathways and alter the relative attractiveness of specific modernization strategies.

These modelling choices imply several limitations that future research can address. First, the deterministic treatment of demand and cost trajectories ignores short-term volatility and long-term uncertainty, which may be significant in sectors exposed to fuel price shocks, business cycles, or disruptive technological change. Second, the regulatory environment is modeled as exogenously specified emission caps and budgets, whereas in practice, policy instruments may evolve endogenously in response to observed behaviours or macroeconomic conditions. Third, the illustrative instance abstracts from infrastructure constraints, behavioural factors, and heterogeneous risk preferences across decision-makers, all of which can influence transition dynamics. Researchers can overcome these limitations by embedding the HMPFPP within scenario-based analyses, by coupling it with stochastic or robust optimization layers, or by integrating it into richer simulation environments that capture behavioural and institutional complexity.

Future extensions of the HMPFPP may therefore incorporate uncertainty explicitly, for example by introducing stochastic demand and energy price processes, or by representing regulatory trajectories through multiple policy scenarios. Scenario-dependent parameters could be used to generate families of transition pathways and to study how sensitive optimal fleet strategies are to alternative assumptions about technology costs, emission limits, or outsourcing conditions. Stochastic or robust variants of the model could provide worst-case or distributional guarantees for key performance indicators, such as total cost or cumulative emissions, thereby enhancing its value as a risk-aware decision-support tool. Additional research directions include extending the model to multi-energy systems (e.g., combined electricity, hydrogen, and biofuels), coupling it with infrastructure planning modules, or linking it with approximate dynamic programming approaches to capture adaptive decision-making over time better.

Future research may also incorporate behavioral, economic, or uncertainty-related factors, such as scenario-dependent energy prices, stochastic demand, differentiated infrastructure requirements, or user-specific adoption barriers. Extensions toward multi-energy systems, hydrogen-based technologies, or dynamic grid-emission factors would further enhance the model’s practical relevance for real-world planning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K., K.G. and R.K.; methodology, A.K., K.G. and R.K.; software, A.K.; validation, A.K., K.G. and R.K.; investigation, A.K. and K.G.; data curation, A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, K.G.; writing—review and editing, A.K., K.G. and R.K.; visualization, R.K.; supervision, A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research project was partly supported by the program “Excellence initiative—research university” granted to the AGH University of Krakow.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT 5.1 for proofreading.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AHP | Analytic Hierarchy Process |

| HMPFPP | Holistic Multi-Period Fleet Planning Problem |

| LCA | Lifecycle Assessment |

| LP | Linear Programming |

| MARKAL | MARKet ALlocation model |

| MCDM/A | Multi-Criteria Decision Making/Aiding |

| MILP | Mixed-Integer Linear Programming |

| MINLP | Mixed-Integer Non-Linear Programming |

| NLP | Non-Linear Programming |

| RES | Reference Energy System |

| TCO | Total Cost of Ownership |

| ZEZ | Zero-Emission Zone |

References

- Ahani, P.; Arantes, A.; Garmanjani, R.; Melo, S. Optimizing Vehicle Replacement in Sustainable Urban Freight Transportation Subject to Presence of Regulatory Measures. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelati, M.H. A Multi-Period MILP for Strategic Transportation Electrification under Incentive Expiry and Fuel Price Volatility. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Bus. Sci. 2025, 6, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Tian, X.; Guan, X. An approximate dynamic programming algorithm for multi-period maritime fleet renewal problem under uncertain market. Int. J. Shipp. Transp. Logist. 2023, 16, 96–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkelmann, J.; Spinler, S.; Neukirchen, T. Green transport fleet renewal using approximate dynamic programming: A case study in German heavy-duty road transportation. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2024, 186, 103547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Chen, S. Fleet replacement decisions under demand and fuel price uncertainties. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2018, 60, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahani, P.; Arantes, A.; Melo, S. A portfolio approach for optimal fleet replacement toward sustainable urban freight transportation. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2016, 48, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmer, A. Strategic vehicle fleet management—The replacement problem. LogForum—Sci. J. Logist. 2016, 12, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbone, L.G.; Giesen, G.; Goldstein, G. User’s Guide for MARKAL (BNL/KFA v. 2.0): A Multi-Period, Linear-Programming Model for Energy Systems Analysis; Technical Report; Brookhaven National Laboratory: Upton, NY, USA, 1983; originally published as OSTI-ID-5419690.

- Manne, A.S.; Wene, C.O. MARKAL-MACRO: A Linked Model for Energy-Economy Analysis; Technical Report; Brookhaven National Laboratory: Upton, NY, USA, 1992. [CrossRef]

- Seebregts, A.J.; Goldstein, G.A.; Smekens, K.E.L. Energy/Environmental Modeling with the MARKAL Family of Models; Technical Report ECN-Policy Studies Report RX-01039; Energy Research Centre of the Netherlands (ECN): Petten, The Netherlands; International Resources Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2001.

- Krzyzanowski, D.A.; Kypreos, S.; Barreto, L. Supporting hydrogen based transportation: Case studies with Global MARKAL Model. Comput. Manag. Sci. 2008, 5, 207–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciuk, K.; Santos, C.A.G.; Kulesza, L.; Gawlik, A.; Orzel, A.; Jakubiak, M.; Bajdor, P.; Pytel, S.; Specht, M.; Krzykowska-Piotrowska, K.; et al. An Analysis of Engine Type Trends in Passenger Cars: Are We Ready for a Green Deal? Transp. Telecommun. 2024, 25, 113–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubiak, M. Environmental Impact of Air Transport—Case Study of Krakow Airport. Logistyka 2015, 2, 277–283. [Google Scholar]

- Saafi, M.A.; Gordillo, V.; Alharbi, O.; Mitschler, M. Investigating the Future of Freight Transport Low Carbon Technologies Market Acceptance across Different Regions. Energies 2024, 17, 4925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieda, B.; Książek, R.; Gdowska, K.; Korcyl, A. Decision-Making for Multi-Period Fleet Transition Towards Strategic Decision-Making for Multi-Period Fleet Transition Towards Zero-Emission: Preliminary Study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrashdi, I.; Ali, A.M.; Sallam, K.M.; Abdel-Basset, M. Assessment and Analysis of Development Risks under Uncertainty: The Impact of Disruptive Technologies on Renewable Energy Development. Energy Nexus 2025, 17, 100371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agliata, R.; Busato, F.; Presciutti, A. MCDM-Based Analysis of Site Suitability for Renewable Energy Community Projects in the Gargano District. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sah, B.; Singh, A.R.; Deng, Y.; He, X.; Kumar, P.; Bansal, R.C. A review of multi criteria decision making (MCDM) towards sustainable renewable energy development. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 69, 596–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Dutta, R.; De, S.; De, S. Review of multi-criteria decision-making for sustainable decentralized hybrid energy systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 202, 114676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haralambopoulos, D.A.; Polatidis, H. Renewable energy projects: Structuring a multi-criteria group decision-making framework. Renew. Energy 2003, 28, 961–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Monem, A.; Abdel Gawad, A. A Hybrid Model Using MCDM Methods and Bipolar Neutrosophic Sets for Select Optimal Wind Turbine: Case Study in Egypt. Neutrosophic Sets Syst. 2021, 42, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier, S.; Jabali, O.; Mendoza, J.E.; Laporte, G. The electric bus fleet transition problem. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2019, 109, 174–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahide, O.C.G.; Satoglu, S.I. Optimal Bus Fleet Conversion Planning for Decarbonization: Case Study of Istanbul Metrobus. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 189850–189870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figliozzi, M.A.; Boudart, J.A.; Feng, W. Economic and Environmental Optimization of Vehicle Fleets: Impact of Policy, Market, Utilization, and Technological Factors. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2011, 2252, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korcyl, A.; Książek, R.; Gdowska, K. A MILP Model for Route Optimization Problem in a Municipal Multi-Landfill Waste Collection System. In ICIL 2016: 13th International Conference on Industial Logistics, Zakopane, Poland, 28 September–1 October 2016, Conference Proceedings; Sawik, T., Ed.; AGH University of Science and Technology, International Center for Innovation and Industrial Logistics: Kraków, Poland, 2016; pp. 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Korcyl, A.; Książek, R.; Gdowska, K. A MILP Model for the Municipal Solid Waste Selective Collection Routing Problem. Decis. Mak. Manuf. Serv. 2019, 13, 13–36. [Google Scholar]

- Gdowska, K. Operations Research in Municipal Solid Waste Management: Decision-Making Problems, Applications, and Research Gaps. Decis. Mak. Manuf. Serv. 2021, 15, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, N.; Kocuk, B.; Yuksel, T. A Dynamic Strategic Plan for the Transition to a Clean Bus Fleet using Multi-Stage Stochastic Programming with a Case Study in Istanbul. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.23387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emiliano, W.; Alvelos, F.; Telhada, J.; Lanzer, E.A. An optimization model for bus fleet replacement with budgetary and environmental constraints. Transp. Plan. Technol. 2020, 43, 488–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Hartman, J.C.; Wilson, G.R. An Integrated Model and Solution Approach for Fleet Sizing with Heterogeneous Assets. Transp. Sci. 2005, 39, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, A.; Taghipour, S. Optimal Replacement of a Fleet of Assets with Economic and Environmental Considerations. In Proceedings of the 2018 Annual Reliability and Maintainability Symposium (RAMS), Reno, NV, USA, 22–25 January 2018; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miettinen, K. Nonlinear Multiobjective Optimization; International Series in Operations Research & Management Science; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1999; Volume 12. [Google Scholar]

- Deb, K. Multi-Objective Optimization Using Evolutionary Algorithms; Wiley-Interscience Series in Systems and Optimization; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gdowska, K.; Książek, R.; Korcyl, A.; Krawiec, K.; Trela, M. Optimizing Multi-Period Fleet Utilization and Transition in Municipal Solid Waste Management. In Proceedings of the 45th International Business Information Management Association Conference (IBIMA): Advancements in Artificial Intelligence and Computer Security in Modern Computing, Cordoba, Spain, 25–26 June 2025; Soliman, K.S., Ed.; International Business Information Management Association: Cordoba, Spain, 2025; pp. 676–690. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Gholami Shirkoohi, M.; Akter, R.; Mérida, W. Urban transit decarbonization via stochastic programming and statistical inference under uncertainty. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2025, 142, 104711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, C.; Han, R. Optimal fleet replacement management under cap-and-trade system with government subsidy uncertainty. Multimodal Transp. 2023, 2, 100077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avenali, A.; De Santis, D.; Giagnorio, M.; Matteucci, G. Bus fleet decarbonization under macroeconomic and technological uncertainties: A real options approach to support decision-making. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2024, 190, 103690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubaiat, S. Exploring the Feasibility of Introducing Alternative Fuel Vehicles into Fleet. Master’s Thesis, Utah State University, Logan, UT, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columbu, G.; Magni, C.A.; Baschieri, D. Greening the fleet: Financial modeling for vehicle replacement in waste management. SSRN Electron. J. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Pautsch, G.R. A vehicle replacement policy for motor carriers in an unsteady economy. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2005, 39, 463–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yang, M.; Zhang, R.; Peng, R. Joint Optimization of Electric Bus Infrastructure Planning, Fleet Composition, and Charging Schedule Considering Multi-Gun Charging and Compatibility. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 6690–6701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghipour, S.; Salari, N. Optimal sustainable vehicle replacement model. In Proceedings of the 2015 Annual Reliability and Maintainability Symposium (RAMS), Palm Harbor, FL, USA, 26–29 January 2015; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabian, A.; Ghaleb, M.; Taghipour, S. Optimal Replacement, Retrofit, and Management of a Fleet of Assets under Regulations of an Emissions Trading System. Eng. Econ. 2020, 66, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Y.A.; Hrairi, M.; Kattan, I.A. Improvement of greenhouse by reducing gas emissions using replacement policy. Int. J. Energy Technol. Policy 2012, 8, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alp, O.; Tan, T.; Udenio, M. Transitioning to sustainable freight transportation by integrating fleet replacement and charging infrastructure decisions. Omega 2022, 109, 102595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Nagar, D.; Ramanath, V.; Subbaiah, S.B. Optimal Transition of Fleets to Electric Vehicle using Mathematical Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Transportation Electrification Conference (ITEC-India), Chennai, India, 12–15 December 2023; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.