Abstract

Pleurotus ostreatus, commonly known as the oyster mushroom, is increasingly recognized as a key agrobiotechnological resource within sustainable development frameworks due to its ecological adaptability, rich nutritional profile, and broad socioeconomic contributions. This review integrates agroecological, socioeconomic, and biotechnological dimensions to examine its taxonomic identity, resilience to diverse environmental conditions, and efficiency in organic waste bioconversion. The species plays a critical role in circular bioeconomy strategies by advancing environmental sustainability, improving food and nutrition security, and supporting rural livelihoods through accessible, low-cost cultivation practices. Additionally, P. ostreatus demonstrates significant nutraceutical and pharmacological properties, making it a promising candidate for innovative biotechnological applications. Drawing on global and local case studies, this review highlights the species’ capacity to strengthen resilient agroecological systems and inclusive approaches to public health and livelihoods. Promoting its cultivation further enhances community well-being by generating equitable economic opportunities, empowering small-scale producers, and fostering social cohesion through sustainable food networks and shared resource systems. According to Mexico’s agroecological conditions, P. ostreatus represents a potential alternative to generate socioeconomic and nutritional benefits for the population at large.

1. Introduction

Pleurotus ostreatus, commonly known as the oyster mushroom, has emerged as a model organism in agrobiotechnology due to its capacity to transform lignocellulosic agricultural residues into nutritionally valuable biomass [1]. This bioconversion process not only addresses waste management and environmental degradation but also contributes to sustainable agricultural models and circular bioeconomy systems [2], promoting both ecological balance and economic viability.

Among edible fungi, Pleurotus species are notable for their fast growth, low input requirements, and adaptability to diverse agro-industrial by-products [3]. These features make them ideal for decentralized food production and climate-resilient farming, particularly in regions with limited resources [4]. Their cultivation exemplifies a low-carbon, high-efficiency production model that enhances food security and rural development [5].

In Mexico, Pleurotus species hold significant potential due to the country’s rich fungal biodiversity and deeply rooted ethnomycological traditions. Indigenous communities, such as the Mixtec, Zapotec, Mazatec, and Mayan people, have long harvested and utilized wild mushrooms, including Pleurotus, for culinary, medicinal, and cultural purposes [6]. This traditional knowledge underscores the socioecological relevance of Pleurotus and its value in preserving biocultural heritage, while also highlighting the need to integrate ancestral practices into modern agroecological systems [7,8]. Moreover, P. ostreatus has become one of the most economically important cultivated mushrooms in Mexico, with recent national estimates indicating an annual production of approximately 7000–8500 tons, representing nearly 30–35% of the country’s total edible mushroom output. The cultivated area dedicated to oyster mushrooms has expanded to more than 450 production units nationwide, generating an estimated market value exceeding 450–500 million MXN annually and supporting small and medium-scale producers across central and southern states such as Puebla, Hidalgo, Estado de México, Veracruz, and Chiapas [9,10]. These economic indicators highlight the strategic importance of P. ostreatus within Mexico’s agrifood sector, reinforcing its potential to strengthen regional food sovereignty and rural economies.

Ecologically, P. ostreatus functions as a primary saprotroph, decomposing a wide array of lignocellulosic substrates such as straw, corn stover, sawdust, and coffee pulp [11]. This enzymatic capacity to break down lignin and cellulose plays a vital role in nutrient cycling and soil regeneration in forest and agricultural ecosystems [12]. Moreover, its enzymatic plasticity supports its application in bioremediation and sustainable land management programs [13].

As functional foods, Pleurotus mushrooms are valued for their high protein content, essential micronutrients, and bioactive compounds with antioxidant, immunomodulatory, and lipid lowering effect [14,15]. Solid-state fermentation using locally available substrates enhances biological efficiency and productivity, particularly under resource-limited conditions [16]. In Mexico, local studies have reported high yields of Pleurotus species cultivated on a wide variety of native agricultural substrates [17].

Despite its wide use, the full biotechnological potential of P. ostreatus remains underexplored. Emerging approaches in omics technologies, including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, combined with next-generation tools in biochemistry and molecular biology, offer powerful avenues to better understand its physiology, genetic diversity, and metabolic pathways [17]. These insights are critical for improving commercial strains, enhancing substrate utilization, and unlocking novel nutraceutical and pharmaceutical applications [17,18,19].

Globally, the mushroom market is expanding, with Pleurotus species accounting for nearly 25% of total production. However, its cultivation is concentrated in Asia, while Latin America, despite its favorable agroecological conditions, remains underrepresented. Expanding local production could generate sustainable income for smallholders and promote regional food sovereignty [20,21].

Beyond its agronomic value, P. ostreatus contributes to sustainable food systems and rural livelihoods, particularly for women and marginalized groups. Spent substrates can be reused as organic fertilizers or livestock feed, reinforcing holistic waste valorization strategies [22]. Moreover, its role in environmental biotechnology, especially in mycoremediation, positions P. ostreatus at the intersection of agricultural innovation, ecology, and social development [23].

This review explores the agrobiotechnological potential of P. ostreatus by elucidating its agroecological roles, socioeconomic contributions, and relevance in bioinnovation. A transdisciplinary and culturally inclusive framework is essential to fully harness its capacity to contribute to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

2. Biological Aspects of Edible Fungi

Edible fungi constitute a diverse group of macroscopic organisms that fulfill essential ecological, nutritional, and economic functions. Among them, P. ostreatus, commonly known as the oyster mushroom, is one of the most extensively cultivated species worldwide due to its rapid growth, high nutritional profile, and capacity to degrade a wide range of lignocellulosic substrates [9,11,23,24]. A comprehensive understanding of their biological characteristics, including morphology, reproductive biology, and physiological responses, is essential for optimizing cultivation practices and unlocking their full biotechnological potential.

In Mexico, P. ostreatus is one of the principal cultivated mushrooms in small and medium scale production units, where it is grown on regionally abundant residues such as maize stover, bean haulms, pumpkin and squash residues, sugarcane by products, coffee pulp, prickly pear glochids, and mixed agroforestry wastes. These systems integrate mushroom production into diversified agroecosystems and contribute to food security, income diversification, and circular use of biomass in rural communities.

2.1. Morphology and Mycelial Architecture

The morphological characteristics of P. ostreatus, as with other basidiomycetes, are primarily defined by two structures: the vegetative mycelium and the reproductive basidiocarp (fruiting body). The mycelium comprises an extensive network of hyaline, septate hyphae with strong substrate colonization capacity (Figure 1). These hyphae exhibit apical growth, frequent branching, and hyphal fusion (anastomosis), enabling efficient resource acquisition and substrate degradation [25].

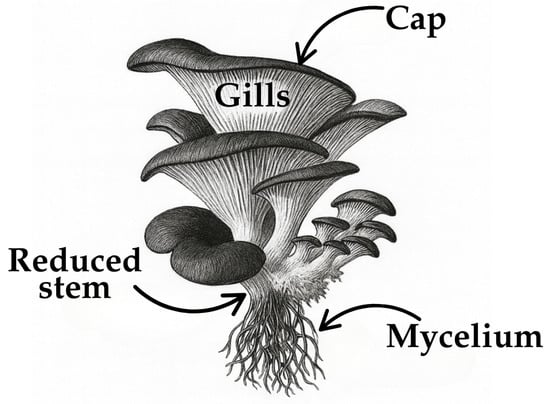

Figure 1.

Morphological structure of Pleurotus ostreatus (Oyster mushroom). The diagram illustrates key anatomical components including the cap (pileus), gills (lamellae), a reduced stem (stipe), and the mycelium, which anchors the fungus and absorbs nutrients from the substrate.

The fruiting body is typically fan-shaped with a laterally attached stipe and conspicuous gills (lamellae) on the lower surface, where basidiospores are produced on basidia. These reproductive structures are responsible for the dispersal and propagation of the fungus under favorable environmental conditions. The expression of both macroscopic and microscopic traits is influenced by factors such as relative humidity, temperature, CO2 concentration, and light exposure. These variables not only shape morphological development but also affect physiological efficiency and fruiting body productivity [26].

Environmental parameters modulate morphogenesis at both vegetative and reproductive stages. For instance, appropriate photoperiod and humidity levels are critical for pileus expansion and gill differentiation, while suboptimal conditions can result in malformed or reduced fruiting structures. The adaptability of P. ostreatus morphology to such external cues contributes to its high yield and resilience under diverse cultivation conditions [27].

2.2. Reproductive Biology and Spore Production

P. ostreatus reproduces sexually through the production of basidiospores and can propagate asexually by mycelial fragmentation. Basidiospores are generated on the surface of basidia, located within the hymenial layer of the lamellae (gills) of the fruiting body (Figure 2). These haploid spores can germinate under favorable environmental conditions to produce monokaryotic mycelia. When two compatible monokaryons undergo hyphal fusion (plasmogamy), a dikaryotic mycelium is formed, which can initiate the development of mature fruiting bodies [28].

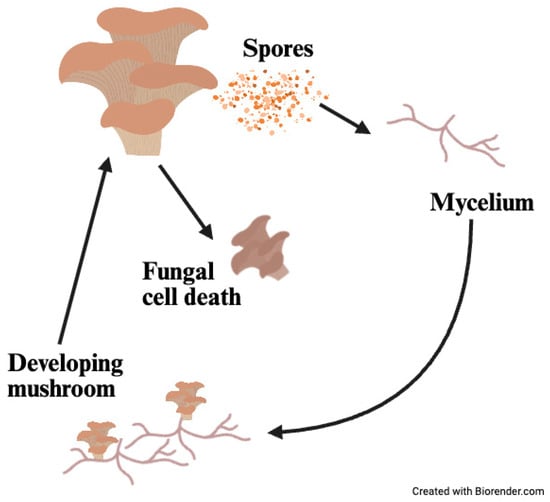

Figure 2.

Reproductive cycle of P. ostreatus (Oyster mushroom). The diagram illustrates the life stages of the fungus, beginning with spore release, followed by mycelium development from germinated spores. The mycelium grows through the substrate, leading to the formation of a developing mushroom. After maturation, the mushroom undergoes fungal cell death, completing the cycle and initiating new spore release.

Spore productivity, germination efficiency, and viability are critical parameters for the selection and breeding of elite commercial strains. These reproductive traits are particularly important in spawn production and genetic improvement programs, which aim to enhance biological efficiency, yield, and tolerance to abiotic stress [29].

Beyond P. ostreatus, other species such as P. eryngii, P. pulmonarius, and P. djamor exhibit similar reproductive mechanisms but differ in spore morphology, viability rates, and environmental requirements for fruiting. For instance, P. eryngii tends to produce fewer but larger basidiospores, while P. djamor is known for its rapid life cycle and high spore productivity under tropical conditions. These interspecific differences highlight the importance of reproductive biology in tailoring cultivation protocols to species-specific traits and environmental contexts [30].

In Mexico, strain selection and spawn quality have been optimized to accommodate regional temperature regimes and rustic infrastructure. Subtropical strains of P. ostreatus used in central and southern Mexico tolerate relatively high fruiting temperatures (up to 26–28 °C) without severe loss of yield, enabling year-round production in simple growing rooms with limited climate control [16]. This reproductive plasticity is essential for integrating mushroom cultivation into smallholder systems where cold rooms or advanced environmental controls are rarely available.

2.3. Physiological Traits and Lignocellulolytic Enzyme Activity

Mushrooms are macrofungi with complex physiological systems that rely on the secretion of extracellular enzymes to access nutrients from lignocellulosic materials. These enzymes decompose complex polymers such as lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose into simpler, assimilable molecules [31]. Among edible fungi, Pleurotus species exhibit some of the most efficient lignocellulolytic systems, making them valuable in both ecological and industrial contexts. P. ostreatus, the most widely studied species, produces a versatile enzymatic arsenal that includes laccases, manganese peroxidases (MnPs), lignin peroxidases (LiPs), cellulases, and xylanases [32]. These enzymes act synergistically to degrade plant biomass, enabling the fungus to colonize a broad range of agricultural residues such as wheat straw, sugarcane bagasse, corn stalks, and sawdust. Laccases and MnPs, in particular, play a key role in lignin degradation, a process critical for accessing cellulose and hemicellulose embedded in plant cell walls.

Different Pleurotus species exhibit varying enzymatic profiles depending on their ecological niche and genetic makeup. For instance, Pleurotus eryngii (king oyster mushroom) has shown high laccase activity, which enhances its ability to degrade aromatic compounds and pollutants, positioning it as a strong candidate for environmental bioremediation [33]. Similarly, P. pulmonarius demonstrates robust cellulolytic activity, which supports its effectiveness in composting and agricultural residue recycling [34].

The activity and expression levels of these enzymes are influenced by multiple factors, including the type and composition of the substrate, the carbon-to-nitrogen (C:N) ratio, pH, moisture content, and temperature [35]. Solid-state fermentation systems often enhance enzyme yield due to favorable microaerophilic conditions and substrate stability. For example, cultivation of P. ostreatus on banana leaves and spent coffee grounds has led to significant increases in both laccase and cellulase activities, improving biological efficiency and biomass conversion [36]. Beyond nutritional roles, these enzymatic capabilities support key biotechnological applications. In environmental contexts, Pleurotus spp. are used for the degradation of persistent organic pollutants (e.g., dyes, phenols, and pesticides). In industrial biotechnology, their enzymes are applied in paper bleaching, bioethanol production, and the formulation of eco-friendly detergents [37].

2.4. Substrate Colonization and Growth Dynamics

The colonization of lignocellulosic substrates by P. ostreatus is a complex and dynamic process governed by the coordinated action of extracellular enzymes, efficient nutrient assimilation, and the progressive expansion of its mycelial network. This process is crucial for successful fruiting body development and overall biological efficiency [38].

In optimal conditions, P. ostreatus typically completes substrate colonization within 14 to 21 days, depending on variables such as substrate type, particle size, moisture content, aeration, and temperature [39]. Rapid mycelial growth is considered a key agronomic trait, as it reduces vulnerability to contamination by competing microorganisms and shortens the overall production cycle. These characteristics are particularly advantageous in small-scale or decentralized cultivation systems, where resource constraints and sanitation challenges are common [40].

P. ostreatus exhibits a remarkable ability to adapt to a broad spectrum of agro-industrial residues, including wheat straw, sugarcane bagasse, sawdust, banana leaves, coffee pulp, and cotton stalks [41]. This substrate versatility supports its integration into circular bioeconomy strategies by enabling the recycling of agricultural waste while generating high-quality protein biomass. Studies have shown that the colonization rate and subsequent yield are directly influenced by substrate porosity, C:N ratio, and pre-treatment methods, such as pasteurization or alkali soaking, which enhance substrate digestibility and reduce microbial competition [42].

The kinetics of colonization can be further optimized through selective breeding of high-performing strains, as well as through the use of nutrient-enriched spawn carriers or amendments like gypsum and wheat bran, which improve aeration and nutrient availability. Monitoring parameters such as hyphal density, color changes, and CO2 evolution can provide reliable indicators of colonization progress and physiological health [43].

Overall, the efficient substrate colonization capacity of P. ostreatus reinforces its suitability for sustainable food production and waste valorization models, especially in resource-limited environments. Its rapid and robust colonization behavior enhances productivity and strengthens its role as a bioeconomic agent for rural development and low-input agricultural systems [44].

The colonization of substrates by edible fungi is a multifactorial process involving enzymatic degradation, nutrient assimilation, and spatial expansion of the mycelial network. In the case of P. ostreatus, colonization is typically completed within 17 days, depending on substrate composition and environmental conditions [39]. Rapid mycelial expansion is an important agronomic trait, as it reduces contamination risk and shortens the production cycle. Moreover, P. ostreatus displays a high adaptability to various agro-industrial residues, including straw, coffee pulp, and sawdust, which promotes its use in circular bioeconomy systems [41].

2.5. Biological and Production Features of Pleurotus ostreatus in Mexico and Their Relevance to Local Agriculture and Food Systems

The biological attributes of P. ostreatus rapid mycelial growth, efficient lignocellulose degradation, high biological efficiency (BE), and relatively broad tolerance to temperature and humidity are particularly advantageous under Mexican agroecological conditions. Rural and periurban production units can rely on locally collected residues (maize, beans, squash, sugarcane, coffee, and nopal by products) as substrates, thereby transforming low-value biomass into nutrient dense food while reducing open field burning and residue accumulation.

At the production level, Mexican studies collectively show that P. ostreatus can achieve BE values ≥ 100% on multiple local residue combinations, with production cycles completed in 30–60 days even in rustic infrastructure [45,46]. These cycles are compatible with smallholder labor calendars and can be integrated into existing cropping systems without displacing staple crops.

From a food systems perspective, P. ostreatus contributes high-quality protein, dietary fiber, micronutrients, and bioactive compounds to local diets, with potential to diversify food baskets and improve household nutrition in communities where animal protein may be limited or expensive [15]. The relatively low entry cost and scalability of oyster mushroom cultivation have made it a viable micro-enterprise option, often led by women and producer groups, thereby strengthening local value chains and contributing to rural livelihoods [45].

Finally, the reuse of spent mushroom substrate (SMS) as organic amendment or livestock feed which is increasingly documented in Mexico and elsewhere closes nutrient loops and enhances the sustainability of agroecosystems, aligning P. ostreatus production with the principles of circular bioeconomy and agroecology [47]. Taken together, these biological and production characteristics justify a focused treatment of P. ostreatus in the context of Mexican agriculture and support its promotion as a strategic species for resilient, low-carbon local food systems.

3. Taxonomic Classification of Pleurotus spp.

The genus Pleurotus comprises one of the most ecologically and economically significant groups of edible macrofungi, cultivated worldwide and valued for their nutritional richness and biotechnological potential [48]. As shown in Table 1, species of this genus have been progressively discovered over the last 150 years, each exhibiting distinct ecological adaptations and functional properties. These fungi are primarily saprotrophic, colonizing lignocellulosic substrates such as decaying logs, stumps, and fallen branches, especially in tropical and subtropical forests.

Table 1.

Taxonomic chronology and functional characterization of selected Pleurotus species.

Biogeographical and molecular studies have established that the genus Pleurotus represents one of the most prominent groups of wood-decaying fungi across terrestrial ecosystems, primarily due to its robust ligninolytic enzyme systems, particularly laccases and versatile peroxidases [15]. Among these, P. ostreatus has garnered considerable attention for its broad agronomic adaptability, high yield potential, and global economic importance in mushroom cultivation [49].

Accurate species delimitation within this genus is crucial for ecological monitoring, biodiversity conservation, and the selection of superior commercial strains. Advances in molecular systematics, including ITS (internal transcribed spacer) sequencing and phylogenetic analyses, have significantly improved the resolution of species complexes and clarified taxonomic ambiguities within Pleurotus. As of current classifications, over 200 species are attributed to the oyster mushroom group [50], with eight species, P. ostreatus, P. eryngii, P. pulmonarius, P. djamor, P. sajor-caju, P. cystidiosus, P. citrinopileatus, and P. cornucopiae, being cultivated commercially on a global scale.

In Mexico, native Pleurotus species such as P. albidus, P. djamor, and the recently described P. bajocalifornicus and P. australis have been identified in diverse forest ecosystems, including temperate and tropical regions. These species demonstrate promising lignocellulolytic activity, thermal tolerance, and adaptability to local agro-industrial residues, making them valuable candidates for biotechnological applications such as bioremediation, enzyme production, and rural bioeconomy development. Their integration into strain improvement programs could enhance both productivity and environmental sustainability in local mushroom cultivation systems [17,47].

3.1. Taxonomic Hierarchy and Morphological Constraints

P. ostreatus is classified taxonomically as follows: Kingdom Fungi, Phylum Basidiomycota, Class Agaricomycetes, Order Agaricales, Family Pleurotaceae, and Genus Pleurotus. This genus comprises one of the most diverse and ecologically significant clades of saprotrophic fungi, primarily involved in wood decay across various ecosystems [7].

Historically, classification was based on macroscopic features, such as pileus shape, gill attachment, and spore color, and microscopic structures like basidiospore size and hyphal clamp connections. However, many of these morphological traits are highly plastic and environmentally influenced, making them unreliable for species delimitation, especially among cryptic or closely related taxa [50].

Recent advances in molecular biology have provided high-resolution tools for resolving these taxonomic ambiguities. DNA-based techniques such as ITS sequencing, isozyme profiling, and single-copy nuclear gene analyses have revealed extensive cryptic speciation within the P. ostreatus complex and allowed for more accurate phylogenetic placement. Although RAPD (Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA) is primarily used to assess intraspecific genetic variability, it has also been employed in preliminary differentiation of closely related Pleurotus isolates, helping to identify genetic polymorphisms that complement higher-resolution sequencing approaches [48,49].

A landmark study employing 40 single-copy orthologous genes demonstrated that the P. ostreatus complex is monophyletic and consists of at least 20 phylogenetically distinct species, several of which remain undescribed. The evolutionary origin was traced to East Asia during the Late Eocene (~39 mya), with subsequent diversification driven by climatic fluctuations and intercontinental dispersal events [49,50].

In Mexico, over 20 species of Pleurotus have been reported, but only about seven are currently considered valid based on modern taxonomic criteria. Notably, P. ostreatus, P. columbinus, P. djamor, and P. pulmonarius are the most frequently studied and cultivated species, although the wild progenitors of commercial strains are often unknown or misidentified [7].

3.2. Genetic Diversity and Species Delimitation

Recent molecular studies have revealed extensive genetic diversity within the genus Pleurotus, uncovering cryptic species and significant intraspecific variation, particularly in P. ostreatus. This diversity is often shaped by geographical and ecological factors, leading to genetic divergence between strains from temperate and tropical regions, likely due to historical isolation and environmental adaptation [51,52,53,54,55].

To resolve taxonomic ambiguities and accurately delimit species, multilocus sequence analysis (MLSA) and DNA barcoding using nuclear and mitochondrial markers—such as ITS, RPB2, and EF1α—have proven effective [52,55]. However, high levels of intraisolate variation in these genes may compromise their utility for barcoding, underscoring the importance of using combined molecular approaches (Table 2).

Additional studies using ISSR (inter-simple sequence repeat), RAPD and SSRs (Simple sequence repeats) have demonstrated moderate to high genetic polymorphism among commercial and wild isolates, which is critical for breeding programs, conservation, and strain authentication [56]. Notably, microsatellite markers have been especially useful for establishing core collections and assessing the population structure of cultivated strains [57]. Understanding genetic diversity and species boundaries in Pleurotus is therefore fundamental for both taxonomy and biotechnological exploitation, ensuring accurate identification and optimized strain development across diverse cultivation systems.

Table 2.

Molecular tools used for the identification and characterization of Pleurotus species.

Table 2.

Molecular tools used for the identification and characterization of Pleurotus species.

| Fungal Species | Molecular Tool | Achieved | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pleurotus spp. | ITS (Internal Transcribed Spacer) | Molecular identification and differentiation of species within the genus | [58] |

| P. ostreatus/P. sapidus | PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) | Differentiation between P. ostreatus and P. sapidus | [59] |

| P. eryngii | EF1α and RPB2 (genes) | Phylogeny of the P. eryngii complex | [60] |

| P. eryngii | AFLP and RFLP (DNA-fingerprinting) | Genotypic identification in the P. eryngii complex | [61] |

| Pleurotus spp. | ITS (in silico analysis) | Evaluation of PCR biases for fungi | [62] |

| Pleurotus spp. | Mitochondrial rRNA subunits (V4, V6, V9) | Phylogenetic relationships among species | [63] |

| Pleurotus spp. | ITS and morphology | Genetic diversity among Jordanian isolates | [64] |

| P. ostreatus | CRISPR/Cas9 | Marker-free gene editing in P. ostreatus | [65] |

3.3. Phylogenetic Relationships and Molecular Approaches

The ITS region of nuclear ribosomal DNA has been adopted as the universal barcode marker for fungi due to its high interspecific variability and strong discriminatory power across Basidiomycota, including Pleurotus species [52]. Combined with other loci such as the large subunit (nLSU), RNA polymerase II second subunit (RPB2), and translation elongation factor 1-α (EF1-α), ITS sequencing provides robust phylogenetic resolution and has revealed the existence of at least 20 distinct phylogenetic species within the P. ostreatus complex.

Advanced phylogenetic analyses using multilocus datasets have confirmed that P. ostreatus forms a well-supported monophyletic clade, closely related to species such as P. pulmonarius and P. eryngii [63]. Intraspecific variability, likely shaped by biogeographic isolation and artificial selection, contributes to the rich phylogenetic structure within P. ostreatus populations [66].

Molecular markers such as amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP), RAPD, and simple sequence repeats (microsatellites) have also been employed to assess genetic diversity, gene flow, and strain differentiation within Pleurotus spp. [57]. AFLP and RAPD analyses have demonstrated high polymorphism levels, revealing considerable intra- and inter-population variation across commercial and wild isolates [67,68].

These tools are indispensable for resolving species delimitation, monitoring biodiversity, and enhancing breeding programs through precise genetic selection. The integration of phylogenomic and population-level molecular data continues to refine our under-standing of evolutionary dynamics within the Pleurotus genus and underpins its applications in biotechnology and sustainable agriculture.

4. Ecological Aspects of Pleurotus ostreatus

P. ostreatus is a widely distributed saprotrophic fungus with significant ecological and biotechnological relevance. Native to temperate and subtropical forests, P. ostreatus plays a crucial role in nutrient cycling by decomposing lignocellulosic biomass. Its remarkable ability to colonize a wide variety of substrates, tolerate diverse environmental conditions, and secrete a suite of ligninolytic enzymes positions it as a keystone organism in forest ecosystems and a promising agent for sustainable agriculture and organic waste valorization [11,26].

4.1. Saprophytic Lifestyle and Substrate Versatility

As a primary saprotroph, P. ostreatus predominantly colonizes decaying wood, leaf litter, and a variety of agricultural residues [49]. Its extensive hyphal network infiltrates complex organic matter, enzymatically digesting plant polymers and facilitating nutrient acquisition while contributing to soil humus formation. Owing to their rapid mycelial growth and high biological efficiency, often approaching 100%, Pleurotus species are readily cultivated on a wide array of agro-industrial substrates [69]. These mushrooms are nutritionally rich, providing high-quality proteins, dietary fiber, essential amino acids, carbohydrates, water-soluble vitamins, and trace minerals. Moreover, they contain a di-verse array of bioactive compounds with functional and therapeutic potential.

Pleurotus mushrooms are valued not only for their nutritional and medicinal properties but also for their flavor, aroma, and preservation qualities, which support their status as a culinary delicacy [13]. P. ostreatus exhibits exceptional lignocellulolytic capabilities, particularly on hardwoods such as beech and oak, though it also thrives on non-woody substrates including straw, corn stalks, and banana leaves [29]. The morphological and ecological diversity is illustrated in Figure 3. Such plasticity underpins its broad geo-graphic distribution and robust adaptability to diverse ecological niches, including both natural and managed agroecosystems.

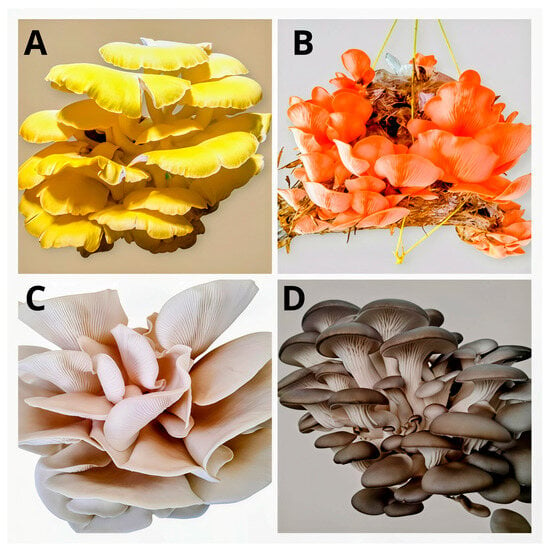

Figure 3.

Morphological diversity of Pleurotus species cultivated on different substrates: (A) P. citrinopileatus (yellow oyster), (B) P. djamor (pink oyster), (C) P. ostreatus (white oyster), and (D) P. ostreatus (gray oyster). All photographs are original and were taken by the authors.

4.2. Decomposition of Organic Matter and Enzymatic Activity

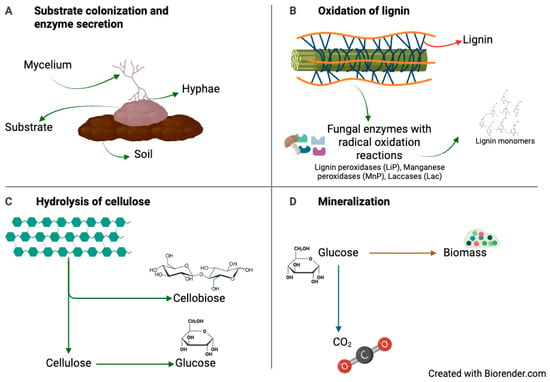

The ecological significance of P. ostreatus resides in its ability to produce a comprehensive suite of extracellular enzymes capable of degrading lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose. Among these, laccases and manganese peroxidases (MnPs) play a pivotal role in its ligninolytic system, facilitating the oxidative depolymerization of lignin and enhancing access to embedded carbohydrates [26]. This enzymatic arsenal enables P. ostreatus to efficiently decompose recalcitrant organic matter, positioning it as a critical agent in forest litter degradation and composting systems.

By accelerating the breakdown of plant biomass, P. ostreatus contributes significantly to carbon cycling, nutrient mineralization, and the restoration of soil organic matter. Its activity improves soil structure, enhances microbial biodiversity, and increases bioavailability of essential nutrients, thus playing a foundational role in ecosystem productivity. Furthermore, its robust enzymatic profile underlies its application in biotechnological processes such as mycoremediation, biopulping, and the treatment of lignin-rich industrial effluents (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The mechanism of decomposition of organic matter by Pleurotus ostreatus. (A) Mycelial colonization of lignocellulosic substrates and extracellular enzyme secretion. (B) Lignin oxidation by fungal oxidative enzymes. (C) Hydrolysis of cellulose into cellobiose and glucose by cellulolytic enzymes. (D) Glucose mineralization into biomass or CO2 through fungal metabolism.

4.3. Ecological Adaptability and Environmental Conditions

Pleurotus ostreatus demonstrates remarkable ecological resilience, thriving across a broad range of environmental conditions. It is capable of vegetative growth at temperatures between 10 °C and 30 °C, with optimal fruiting typically occurring between 20 °C and 26 °C. The species also exhibits moderate tolerance to variable pH levels (ranging from slightly acidic to neutral) and diverse moisture regimes. However, high relative humidity, generally above 85%, is essential for the successful development of fruiting bodies [24].

These physiological tolerances confer substantial ecological plasticity, allowing P. ostreatus to remain productive across a broad mesophilic range of temperatures and relative humidity, as long as CO2 levels and substrate moisture are adequately managed. In practice, this species can complete its life cycle and maintain acceptable yields on very heterogeneous lignocellulosic resources, from forest wood and cereal straws to agro-industrial by-products and aromatic plant residues, while preserving normal basidiocarp morphology and biological efficiency. Recent experimental work has shown that P. ostreatus can be successfully cultivated on combinations of hazelnut branches, hazelnut husks, wheat straw, rice husk, and spent coffee grounds, as well as on soybean and sunflower seed processing residues, without major reductions in yield, which illustrates its capacity to adapt to variable microclimatic and nutritional conditions typical of marginal or degraded agroecosystems [70,71]. By exploiting this substrate and climate flexibility, P. ostreatus can colonize and fruit not only in temperate and subtropical forests but also in agroforestry systems, home gardens, and low-input production units established on degraded or low-fertility soils, where other cultivated fungi are less competitive. In parallel, recent nature-based solution frameworks highlight Pleurotus-based cultivation systems as effective tools for valorizing organic residues, improving soil quality, and contributing to mycoremediation of contaminated or disturbed sites, thereby linking oyster mushroom farming with ecological restoration and circular bioeconomy strategies [72]. Taken together, these lines of evidence support the view that the ecological and physiological plasticity of P. ostreatus underpins its widespread cultivation and makes it a promising candidate for sustainable mushroom farming and integrative restoration interventions in diverse environments.

4.4. Role in Agroecosystems and Circular Bioeconomy

Beyond forest ecosystems, P. ostreatus is increasingly utilized in agricultural settings due to its dual functionality in organic waste valorization and sustainable food production. It efficiently bioconverts agricultural residues (wheat straw, corn cobs, and cotton stalks) that are often incinerated or discarded, into high-value edible biomass, thereby mitigating environmental pollution and promoting resource efficiency [11].

Furthermore, its cultivation synergizes with composting systems by initiating the early degradation of lignocellulosic matter, enhancing compost quality and accelerating humus formation, which improves soil structure and fertility. For example, the integration of P. ostreatus into composting piles composed of sugarcane bagasse and poultry litter has been shown to reduce composting time while enriching the final product with fungal-derived nutrients and microbial stability. In the Mexican context, several circular bioeconomy initiatives have demonstrated that P. ostreatus cultivation transforms agro-residues into multiple co-products: mushrooms for food, spent substrate as organic fertilizer, and enzyme-rich biomass for soil regeneration. Case studies in Veracruz, Puebla, and Chiapas reveal successful small-scale and semi-industrial systems utilizing coffee husk, corn stover, and forestry by-products to enhance local sustainability, reduce waste accumulation, and create alternative income streams for rural producers [20].

5. Agroecological, Social, and Economic Contributions

The integration of agroecological principles into agricultural systems is increasingly essential for addressing global challenges such as soil degradation, excessive reliance on external inputs, and persistent rural poverty. P. ostreatus, presents a multifunctional solution through its agroecological adaptability, bioeconomic utility, and sociocultural relevance. Mushroom cultivation, particularly of P. ostreatus, is expanding rapidly in developing regions, where it supports food security for a global population projected to exceed 9.7 billion by 2050 [49].

5.1. Agroecological Roles and Waste Bioconversion

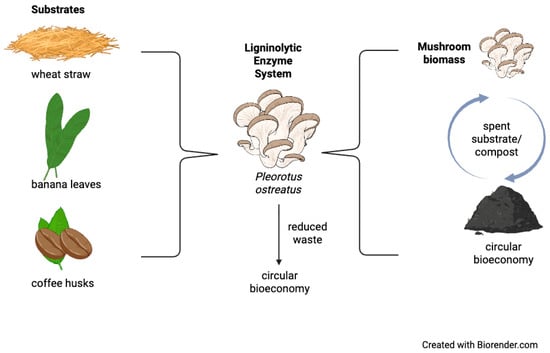

One of the most significant agroecological functions of P. ostreatus lies in its saprotrophic capability to bioconvert lignocellulosic agricultural waste into valuable biomass (Figure 5). Substrates such as wheat straw, sugarcane bagasse, banana leaves, and coffee husks serve as nutrient-rich media for mushroom cultivation [11]. Through its potent ligninolytic enzyme system, P. ostreatus facilitates the breakdown of complex plant polymers like lignin and cellulose, contributing to biomass recycling and reducing greenhouse gas emissions, making it a cornerstone species in low-input, closed-loop farming systems.

Figure 5.

Bioconversion of agricultural residues by Pleurotus ostreatus and its role in the circular bioeconomy.

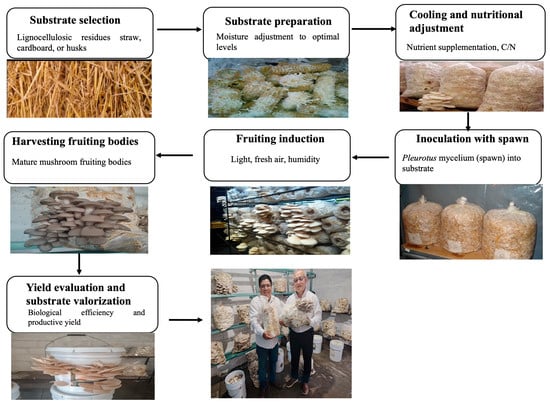

Post-harvest, the spent mushroom substrate (SMS) retains high organic and microbial content, and can be repurposed as a soil conditioner, organic fertilizer, or substrate amendment. Its use enhances soil structure, microbial diversity, and moisture retention capacity, thereby reducing dependence on synthetic agrochemicals [24]. These practices align with agroecological principles that emphasize nutrient recycling, soil regeneration, and environmental sustainability [5] (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Artisanal cultivation process of P. ostreatus on lignocellulosic substrates.

Beyond fruiting, the agroecological impact of P. ostreatus extends through the continuous transformation of the substrate. During colonization, the ligninolytic enzyme system partially depolymerizes lignin and hemicellulose, decreases the C:N ratio, and increases the proportion of water-soluble organic compounds, thereby “pre-conditioning” agricultural residues for subsequent microbial turnover and humus formation [73]. This bioconversion is central to circular bioeconomy strategies because it transforms low-value residues into two complementary products: edible mushroom biomass and a biologically active spent substrate that can re-enter the production system as a soil amendment or as a component of new cultivation mixtures [72].

Recent studies show that spent Pleurotus substrates improve soil physical structure (bulk density, porosity, and water-holding capacity) and supply organic carbon and plant-available nutrients when applied at agronomic rates, resulting in higher vegetable yields and enhanced nutrient-use efficiency compared with unfertilized controls [74]. Composting or co-composting P. ostreatus spent substrate with manures further accelerates humification, stabilizes organic matter, and reduces salinity and phytotoxicity, generating composts that increase microbial biomass, enzyme activities related to C, N and P cycling, and long-term soil fertility [75,76]. Taken together, these processes illustrate how the saprotrophic activity of P. ostreatus operationalizes nutrient recycling and waste valorization in low-input farming systems, providing a practical agroecological tool to improve soil quality while minimizing the environmental burden of lignocellulosic agricultural residues.

5.2. Socioeconomic Benefits and Rural Development

The cultivation of P. ostreatus is increasingly recognized as a viable livelihood strategy in resource-constrained environments due to its low capital investment, short growth cycle, and reliance on locally available substrates [25,67]. In rural communities across Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Southeast Asia, oyster mushroom production has emerged as a tool for food security, economic resilience, and income diversification.

Importantly, P. ostreatus cultivation promotes gender equity by offering women accessible, home-based economic opportunities. In many regions where access to land and formal employment is limited for women, mushroom farming supports their participation in household income generation and agricultural decision-making. Training programs and cooperative models have further enhanced skills development, knowledge transfer, and market access, particularly within indigenous and marginalized populations [77].

5.3. Inclusive and Sustainable Local Economies

The economic value of P. ostreatus extends beyond fresh food production. It underpins the development of microenterprises through value-added products such as dried mushrooms, mushroom powders, and nutraceutical extracts. Its low environmental footprint and high market demand make it a strategic commodity for promoting socially inclusive bioeconomies, where economic equity and environmental stewardship intersect [24].

Moreover, mushroom cultivation supports progress toward several United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), SDG 5 (Gender Equality), and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production). As such, P. ostreatus is a key component in agroecological transitions and territorial development strategies that seek to build more resilient and equitable food systems [78].

The integration of agroecological principles into agricultural systems has become imperative in addressing global challenges such as soil degradation, unsustainable input use and rural poverty. P. ostreatus, one of the most widely cultivated edible fungi worldwide, offers a multifunctional approach to sustainable development through its agroecological adaptability, bioeconomic potential, and socio-cultural relevance. Oyster mushroom cultivation is rapidly growing in developing countries, where it can contribute to food security for the world’s growing population, which is expected to reach 9.7 billion by 2050 [49].

6. Importance in Food, Health, and Medicine

The consumption of edible mushrooms is increasing every year due to their nutritional advantages (rich in valuable proteins, minerals, and dietary fibers) [79]. Pleurotus fungi, also known as basidiomycetous fungi, have been a part of human culture for thousands of years. They exhibit anti-cancer, antitumor, antibacterial, and immunomodulatory effects, having biotechnological, medicinal, and esthetic applications. They are also versatile, highly resistant to illnesses and pests, and do not require special growing conditions. These properties make them readily marketable, and can be found in supermarkets worldwide, generating multimillion-dollar sale revenues [80]. It has been reported by Stanley and Odu [81] that oyster mushroom constitutes of 25–30% protein, 2.50% fat, 17–44% sugar content, 7–38% mycocellulose, and approximately 8–12% mineral (potassium, phosphorus, calcium, and sodium). Furthermore, mushrooms contain a great quantity of dietary fiber and given their chemical structure, they show immunostimulatory and anticancer activity [82,83,84]. Other biological properties of the mushrooms are being antidiabetic, antioxidant, and anti-tumor [85].

Food insecurity and malnutrition are among the major problems in most developing countries recently. Mushroom cultivation is one of the promising strategies to overcome these challenges [86]. In recent decades, global interest in functional and nutraceutical foods has increased significantly, not only for their nutritional value but also for their ability to promote health and prevent disease. Among these, P. ostreatus, commonly known as the oyster mushroom, has emerged as a prominent biofunctional food due to its exceptional nutritional profile and a broad spectrum of pharmacological properties. Widely cultivated across continents, P. ostreatus embodies a paradigmatic edible fungus bridging traditional dietary roles and emerging biotechnological functions [87,88].

Historically, mushrooms have been regarded as special foods. The Greeks believed they conferred strength to warriors; the Pharaohs considered them delicacies; and the Romans referred to them as the “Food of the Gods,” reserving them for festive occasions. Today, mushrooms are increasingly accepted both as food and as dietary supplements. Academic institutions and research centers around the world are actively investigating bioactive metabolites derived from fungi [89].

6.1. Nutritional Composition and Food Value

Pleurotus spp. are one of the most important commercially farmed edible mushrooms, with a global estimated annual production of 6.46 × 106 tons. P. ostreatus is recognized for its excellent nutritional profile, which includes high-quality proteins, essential amino acids, dietary fiber, vitamins, and minerals. Its protein content ranges from 15% to 30% of dry weight, positioning it as a valuable alternative protein source, particularly in regions with limited access to animal-derived products [87].

Moreover, it is a rich source of B-complex vitamins (B1, B2, B3, B5, B9), vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol after UV light exposure), and trace elements such as selenium, potassium, and iron [77,81]. It also provides both soluble and insoluble fiber, which support gut health and promote satiety. Its antioxidant profile includes phenolic compounds, flavonoids, ergothioneine, and carotenoids, which contribute to the mitigation of oxidative stress and reduction in the risk of chronic diseases, such as cancer and cardiovascular disorders [77,82].

6.2. Functional Properties and Health Benefits

The bioactive compounds in P. ostreatus confer a wide range of therapeutic properties. Among the most notable are β-glucans and protein-polysaccharide complexes, which have demonstrated immunomodulatory activity by stimulating macrophage activation, cytokine release, and natural killer (NK) cell function [88]. These immunological effects make P. ostreatus a strong candidate for supportive therapies in immunocompromised individuals and in cancer immunotherapy.

Extracts of P. ostreatus have also shown antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria as well as certain fungal pathogens. This activity is mainly attributed to phenolic acids and lectins, which disrupt microbial membranes and inhibit cell replication [90,91,92].

In addition, the oyster mushroom has demonstrated hypocholesterolemic effects in both animal models and human subjects. The underlying mechanism involves inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase and increased fecal excretion of bile acids, driven by the synergistic action of dietary fiber, ergosterol, and lovastatin-like compounds naturally produced by the fungus [77,84].

6.3. Nutraceutical and Pharmaceutical Applications

Owing to its compositional and functional attributes, P. ostreatus is being increasingly incorporated into nutraceutical formulations including capsules, powders, and functional snacks and is also being explored for pharmaceutical use (Table 3). Its extracts have demonstrated anti-inflammatory, hepatoprotective, and neuroprotective effects, with potential applications in managing metabolic syndrome, liver disorders, and age-related cognitive decline [88]. Fungal chitin and its deacetylated derivative chitosan possess antimicrobial bioactivity and can be used as accelerators of wound healing [93,94].

Table 3.

Pleurotus species. Biological features, bioactive compounds, medical and nutraceutical importance.

6.4. Global Relevance of Edible Mushrooms

Hait et al. [99] emphasize that edible mushrooms exert numerous positive effects on human health, representing a valuable contribution in the global fight against malnutrition and in strengthening food security. P. ostreatus is the second most cultivated edible mushroom worldwide after Agaricus bisporus. It has economic and ecological values and medicinal properties [11]. Due to their high nutritional value and wide range of health benefits, mushrooms are considered an essential food source. As vegan-friendly alternatives to meat, they are rich in proteins, fiber, minerals, vitamins, and provide high caloric value.

Medicinal mushrooms such as P. ostreatus are emerging as therapeutic agents with a broad range of biofunctional properties [100]. They exhibit antibacterial, antifungal, biofilm-inhibiting, antitumor, antidiabetic, COVID-19, neuroprotective, antiviral, prebiotic, immunosuppressive, and immuno-modulatory effects. In addition to their well-documented immunostimulatory properties, these compounds also stand out for their significant anti-inflammatory potential [101]. Bioactive compounds extracted from mushrooms have also been reported to improve the health status of patients with rheumatoid arthritis [102], further underscoring their value as therapeutic resources in chronic inflammatory conditions. The incorporation of functional foods with anti-inflammatory properties, like mushrooms, vegetables, legumes, and fish, represents an effective strategy for managing persistent inflammation.

7. Future Perspectives and Biotechnological Innovation

The field of biotechnology presents a valuable opportunity to utilize a wide range of organisms, including mushrooms, to develop effective solutions for environmental challenges such as the accumulation of agricultural waste [18]. P. ostreatus, commonly known as the oyster mushroom, has gained considerable attention not only for its nutritional and medicinal properties but also for its potential in various biotechnological applications. As global issues such as environmental degradation, plastic pollution, and the need for sustainable food systems intensify, P. ostreatus emerges as a promising organism for innovative solutions [65]. This section explores future perspectives and biotechnological innovations associated with P. ostreatus, focusing on genetic engineering, metabolite profiling, bioplastic production, and its integration into circular economy models.

7.1. Genetic Engineering and Synthetic Biology

Advancements in genetic engineering have opened new avenues for enhancing the capabilities of P. ostreatus. Techniques such as CRISPR-Cas have been used to modify specific genes, resulting in strains with improved growth rates, substrate utilization, and resistance to environmental stresses [65]. Additionally, synthetic biology approaches are being explored to engineer P. ostreatus strains capable of producing novel bioactive compounds, thereby expanding its potential applications in the pharmaceutical and nutraceutical industries [103].

7.2. Metabolite Profiling and Functional Compounds

Metabolite profiling of P. ostreatus has revealed a rich spectrum of bioactive compounds, including polysaccharides, phenolic compounds, and terpenoids, which exhibit antioxidant, antimicrobial, and immunomodulatory activities [104]. Advanced analytical techniques, such as high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS), have facilitated the identification and quantification of these metabolites, enabling the development of functional foods and dietary supplements [105].

7.3. Bioplastic Production and Mycelium-Based Materials

The mycelial network of P. ostreatus has been utilized to produce biodegradable materials, offering a sustainable alternative to conventional plastics. By cultivating P. ostreatus on agricultural and plastic waste substrates, researchers have developed fungal composites suitable for packaging, insulation, and even textile applications [105]. These mycelium-based materials are not only biodegradable but also possess favorable mechanical properties, making them strong candidates for various industrial uses.

7.4. Integration into Circular Economy Models

P. ostreatus has become a key player in circular economy models due to its ability to convert agricultural and industrial waste into high-value-added products. This fungus efficiently degrades lignocellulosic materials such as agave bagasse, coffee husks, and wheat straw, generating edible biomass and useful byproducts like biofertilizers, bioenergy, and biodegradable materials [18]. A notable example can be found in communities in the state of Hidalgo, Mexico, where local agro-industrial residues have been repurposed to cultivate native strains of P. ostreatus, thereby promoting sustainable food production and creating new income opportunities for small-scale producers. Moreover, the post-harvest spent mushroom substrate (SMS) is applied as an organic soil amendment, sustainably closing the production loop [106].

7.5. Pleurotus Breeding by Traditional Genetic

The genetic breeding of P. ostreatus is a key process for developing strains with higher yields and better agronomic traits. A fundamental technique is based on hybridization derived from the genetic variability present in the fungal spores. The process begins with the collection of millions of spores from a selected fruiting body. When germinated on a culture medium, each spore gives rise to a monokaryotic mycelium, which contains only one type of nucleus and is incapable of producing mushrooms [98]. In this way, a library of monokaryotic cultures is generated, each with a unique genetic combination. These isolates are evaluated to select those showing desirable traits, such as high growth rate or dense mycelial structure. Subsequently, the selected monokaryons are crossed with one another. When two compatible monokaryotic mycelia fuse, they form a new dikaryotic mycelium, which contains two genetically distinct nuclei in each cell and has the ability to fruit [99]. These new hybrid dikaryons are cultivated on substrate to assess their productive performance. The goal is to identify strains with superior characteristics, such as higher biological efficiency (more kilograms of mushroom per kilogram of substrate), improved shape, color, or greater disease resistance [100]. This methodology is essential for innovation in the edible mushroom cultivation industry [101], enabling the development of high-yielding strains that are vital for large-scale commercial production [102].

8. Conclusions

In the face of the intersecting global crises of climate change, food insecurity, and social inequality, P. ostreatus emerges as a sustainable, biological solution capable of addressing multiple challenges, from environmental degradation to nutritional gaps. With its ability to recycle lignocellulosic waste and promote ecological restoration, this mushroom provides a model for sustainable agriculture that not only improves soil health but also aligns with circular bioeconomy and agroecological strategies. Its biotechnological versatility, coupled with its nutritional and therapeutic value, positions it as a critical ally in the global fight for food security. In the Mexican context, P. ostreatus presents a unique opportunity to strengthen rural agricultural systems and local economies. Its cultivation can improve nutrition in vulnerable regions, while also promoting the sustainable use of agro-industrial waste and the conservation of natural resources, paving the way for a rural bioeconomy and economic empowerment of communities. Through local training programs and the integration of traditional knowledge, rural communities do not merely grow mushrooms, they build capacity for agricultural innovation, while preserving bioculture and the sustainability of their ecosystems.

The development of an agricultural model based on P. ostreatus can be pivotal for strengthening social economies, providing decentralized income opportunities, especially for women and youth in rural areas. However, these advances must be supported by public policies that promote technology transfer, support research on local strains, and foster collaboration between science and communities. Only through an integrated approach, combining local knowledge with biotechnological innovation, can the full potential of this mushroom be realized, ensuring its positive impact on community well-being and the sustainable management of natural resources.

By integrating P. ostreatus cultivation into Mexico’s local agricultural systems, not only can food security be enhanced, but it also contributes to strengthening rural economies, food sovereignty, and community resilience in the face of climate change and economic globalization. In this way, the mushroom, as both a biological and socioeconomic resource, opens new pathways to building a more equitable, healthy, and sustainable future, where responsible resource management becomes the foundation for inclusive development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Á.G.-J., H.S.-E. and R.R.-R.; validation, C.I.R.-M. and L.A.M.-G.; investigation, R.R.-R., H.S.-E., P.S.-M., A.G.-J. and C.I.R.-M.; resources, M.S.A.-N., F.A.R.-M. and L.A.M.-G.; data analysis, M.Á.G.-J., C.I.R.-M. and R.R.-R.; manuscript writing, C.I.R.-M., A.G.-J., J.C.M.-G. and R.R.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Tecnológico Nacional de México No. 22004.25-P and 21914.25-P.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for publication was obtained from all identifiable human participants in the figures.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Miguel Ángel Gómez Jiménez (CVU No. 1324722) gratefully acknowledges the support of the Master of Science in Sustainable Agroecosystems Graduate Program at the Tecnológico Nacional de México (TECNM). He also expresses his sincere appreciation to the SECIHTI for the financial support provided through the National Scholarship Program for Graduate Studies under the 2023-2 call.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Moreno-Bayona, D.A.; Gómez-Méndez, L.D.; Blanco-Vargas, A.; Castillo-Toro, A.; Herrera-Carlosama, L.; Poutou-Piñales, R.A.; Salcedo-Reyes, J.C.; Díaz-Ariza, L.A.; Castillo-Carvajal, L.C.; Rojas-Higuera, N.S.; et al. Simultaneous Bioconversion of Lignocellulosic Residues and Oxodegradable Polyethylene by Pleurotus Ostreatus for Biochar Production, Enriched with Phosphate Solubilizing Bacteria for Agricultural Use. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirabella, N.; Castellani, V.; Sala, S. Current Options for the Valorization of Food Manufacturing Waste: A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.Z.; Hafiz, M.H. Cultivation of Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus Flabellatus) on Different Substrates. Int. J. Sustain. Crop Prod. 2009, 4, 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Sadh, P.K.; Duhan, S.; Duhan, J.S. Agro-Industrial Wastes and Their Utilization Using Solid State Fermentation: A Review. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2018, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippoussis, A.; Zervakis, G.; Diamantopoulou, P. Bioconversion of Agricultural Lignocellulosic Wastes through the Cultivation of the Edible Mushrooms Agrocybe Aegerita, Volvariella Volvacea and Pleurotus spp. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2001, 17, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-García, U.; Carrera-Martínez, A.; Martínez-Reyes, M.; Hernández-Santiago, F.; Evangelista, F.R.; Díaz-Aguilar, I.; Olvera-Noriega, J.W.; Pérez-Moreno, J. Traditional Knowledge and Use of Wild Mushrooms with Biocultural Importance in the Mazatec Culture in Oaxaca, Mexico, Cradle of the Ethnomycology. For. Syst. 2023, 32, e007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, G. Genus Pleurotus (Jacq.: Fr.) P. Kumm. (Agaricomycetideae): Diversity, Taxonomic Problems, and Cultural and Traditional Medicinal Uses. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2000, 2, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno Fuentes, Á. A Food Resource for Natives and Mestizo Groups of Mexico: The Wild Mushrooms. An. Antropol. 2014, 48, 241–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carminati, G.; Di Foggia, M.; Garagozzo, L.; Di Francesco, A. Mushroom By-Products as a Source of Growth Stimulation and Biochemical Composition Added-Value of Pleurotus Ostreatus, Cyclocybe Cylindracea, and Lentinula edodes. Foods 2024, 13, 2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Martínez, B.d.M.; Vargas-Sánchez, R.D.; Torrescano-Urrutia, G.R.; Esqueda, M.; Rodríguez-Carpena, J.G.; Fernández-López, J.; Perez-Alvarez, J.A.; Sánchez-Escalante, A. Pleurotus Genus as a Potential Ingredient for Meat Products. Foods 2022, 11, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, C. Cultivation of Pleurotus ostreatus and Other Edible Mushrooms. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 85, 1321–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melanouri, E.-M.; Dedousi, M.; Diamantopoulou, P. Cultivating Pleurotus Ostreatus and Pleurotus Eryngii Mushroom Strains on Agro-Industrial Residues in Solid-State Fermentation. Part I: Screening for Growth, Endoglucanase, Laccase and Biomass Production in the Colonization Phase. Carbon Resour. Convers. 2022, 5, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, M.; Guzman, G.; Guzman-Davalos, L. Pleurotus Opuntiae (Durieu et Lev.) Sacc. (Higher Basidiomycetes) and Other Species Related to Agave and Opuntia Plants in Mexico−Taxonomy, Distribution, and Applications. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2012, 14, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayirnao, H.-S.; Sharma, K.; Jangir, P.; Kaur, S.; Kapoor, R. Mushroom-Derived Nutraceuticals in the 21st Century: An Appraisal and Future Perspectives. J. Future Foods 2025, 5, 342–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, J.; Jang, K.-Y.; Oh, Y.-L.; Oh, M.; Im, J.-H.; Lakshmanan, H.; Sabaratnam, V. Cultivation and Nutritional Value of Prominent Pleurotus Spp.: An Overview. Mycobiology 2021, 49, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaitán-Hernández, R.; Silva-Huerta, A. Use of Local Agricultural Wastes to the Production of Pleurotus Spp., in a Rural Community from Veracruz, México. Rev. Mex. Micol. 2016, 43, 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Nakazawa, T.; Kawauchi, M.; Otsuka, Y.; Han, J.; Koshi, D.; Schiphof, K.; Ramírez, L.; Pisabarro, A.G.; Honda, Y. Pleurotus Ostreatus as a Model Mushroom in Genetics, Cell Biology, and Material Sciences. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Ramady, H.; Abdalla, N.; Fawzy, Z.; Badgar, K.; Llanaj, X.; Törős, G.; Hajdú, P.; Eid, Y.; Prokisch, J. Green Biotechnology of Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus Ostreatus L.): A Sustainable Strategy for Myco-Remediation and Bio-Fermentation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekan, A.S.; Myronycheva, O.S.; Karlsson, O.; Gryganskyi, A.P.; Blume, Y.B. Green Potential of Pleurotus Spp. in Biotechnology. PeerJ 2019, 7, e6664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastranzo-Pérez, L.A.; Hernández-Domínguez, E.M.; Falcón-León, M.P.; Álvarez-Cervantes, J. Pleurotus Spp: A Cosmopolitan Fungi of Biotechnological Importance. Sci. Agropecu. 2025, 16, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Bonilla, A.; Meneses, M.E.; Pérez-Herrera, A.; Armengol-Álvarez, D.; Martínez-Carrera, D. Dietary Supplementation with Oyster Culinary-Medicinal Mushroom, Pleurotus Ostreatus (Agaricomycetes), Reduces Visceral Fat and Hyperlipidemia in Inhabitants of a Rural Community in Mexico. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2022, 24, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulam, S.; Üstün, N.; Pekşen, A. Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus Ostreatus) as a Healthy Ingredient for Sustainable Functional Food Production. J. Fungus 2022, 13, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladipo, A.; Alabi, V.; Muse, S.; Ehizojie, O.; Saheed, E.; Oladoye, P.O. Mycoremediation: A Biobased Approach toward Environmental Sustainability. In Management of Mycorrhizal Symbiosis for Mycoremediation and Phytostabilization; Wu, Q.-S., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 285–308. [Google Scholar]

- Royse, D.J.; Baars, J.; Tan, Q. Current Overview of Mushroom Production in the World. In Edible and Medicinal Mushrooms; Diego, C.Z., Pardo-Giménez, A., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- de Mattos-Shipley, K.M.J.; Ford, K.L.; Alberti, F.; Banks, A.M.; Bailey, A.M.; Foster, G.D. The Good, the Bad and the Tasty: The Many Roles of Mushrooms. Stud. Mycol. 2016, 85, 125–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellettini, M.B.; Fiorda, F.A.; Maieves, H.A.; Teixeira, G.L.; Ávila, S.; Hornung, P.S.; Júnior, A.M.; Ribani, R.H. Factors Affecting Mushroom Pleurotus spp. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 26, 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, L.; Wu, X. The Metacaspase Gene PoMCA1 Enhances the Mycelial Heat Stress Tolerance and Regulates the Fruiting Body Development of Pleurotus ostreatus. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, P.G.; Chang, S.-T. Mushrooms: Cultivation, Nutritional Value, Medicinal Effect, and Environmental Impact; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004; ISBN 9780203492086. [Google Scholar]

- Girmay, Z.; Gorems, W.; Birhanu, G.; Zewdie, S. Growth and Yield Performance of Pleurotus Ostreatus (Jacq. Fr.) Kumm (Oyster Mushroom) on Different Substrates. AMB Express 2016, 6, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, A.; Franco, H. Productividad y Calidad de Los Cuerpos Fructíferos de Los Hongos Comestibles Pleurotus pulmonarius RN2 y P. Djamor RN81 y RN82 Cultivados Sobre Sustratos Lignocelulósicos. Inf. Tecnológica 2013, 24, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganash, M.; Abdel Ghany, T.M.; Al Abboud, M.A.; Alawlaqi, M.M.; Qanash, H.; Amin, B.H. Lignocellulolytic Activity of Pleurotus ostreatus under Solid State Fermentation Using Silage, Stover, and Cobs of Maize. Bioresources 2021, 16, 3797–3807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurfitri, N.; Mangunwardoyo, W.; Saskiawan, I. Lignocellulolytic Enzyme Activity Pattern of Three White Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus (Jacq.) P. Kumm.) Strains during Mycelial Growth and Fruiting Body Development. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1725, 012056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpinar, M.; Ozturk Urek, R. Direct Utilization of Peach Wastes for Enhancements of Lignocellulolytic Enzymes Productions by Pleurotus Eryngii under Solid-State Fermentation Conditions. Chem. Pap. 2022, 76, 6699–6712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inácio, F.D.; Ferreira, R.O.; de Araujo, C.A.V.; Peralta, R.M.; de Souza, C.G.M. Production of Enzymes and Biotransformation of Orange Waste by Oyster Mushroom, Pleurotus pulmonarius (Fr.) Quél. Adv. Microbiol. 2015, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aimable, N.; Mediatrice, H.; Claude, I.; Biregeya, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Liu, P.; Li, J.; Lin, Z.; Lu, G.; et al. Enzymatic Activity and Nutrient Profile Assessment of Three Pleurotus Species Under Pasteurized Cenchrus Fungigraminus Cultivation. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpinar, M.; Ozturk Urek, R. Decolorization and Degradation Potential of Enhanced Lignocellulolytic Enzymes Production by Pleurotus eryngii Using Cherry Waste from Industry. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2020, 67, 760–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasiku, S.A.; Wakil, S.M.; Alao, O.K. Degradation of Lignocellulosic Substrates by Pleurotus ostreatus and Lentinus squarrosulus. Asia J. Appl. Microbiol. 2023, 10, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elisashvili, V.; Kachlishvili, E.; Penninckx, M. Lignocellulolytic Enzymes Profile during Growth and Fruiting of Pleurotus Ostreatus on Wheat Straw and Tree Leaves. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 2008, 55, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velázquez-Cedeño, M.A.; Mata, G.; Savoie, J. Waste-Reducing Cultivation of Pleurotus ostreatus and Pleurotus pulmonarius on Coffee Pulp: Changes in the Production of Some Lignocellulolytic Enzymes. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2002, 18, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, S.; Saha, R.; Das, P.; Saha, A.K. Cultivation and Medicinal Properties of Wild Edible Pleurotus ostreatus of Tripura, Northeast India. Vegetos 2019, 32, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimoh, M.A.; Akinyemi, S.A.; Olatunji, O.A.; Olowolaju, E.D.; Okunlola, G.O. Cultivation of Pleurotus ostreatus on Agricultural Wastes and Effects on Nutritional Composition of the Fruiting Body. Int. J. Veg. Sci. 2023, 29, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economou, C.N.; Diamantopoulou, P.A.; Philippoussis, A.N. Valorization of Spent Oyster Mushroom Substrate and Laccase Recovery through Successive Solid State Cultivation of Pleurotus, Ganoderma, and Lentinula Strains. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 5213–5222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bánfi, R.; Pohner, Z.; Kovács, J.; Luzics, S.; Nagy, A.; Dudás, M.; Tanos, P.; Márialigeti, K.; Vajna, B. Characterisation of the Large-Scale Production Process of Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) with the Analysis of Succession and Spatial Heterogeneity of Lignocellulolytic Enzyme Activities. Fungal Biol. 2015, 119, 1354–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widiastuti, H.; Suharyanto; Wulaningtyas, A.; Sutamihardja. Activity of Ligninolytic Enzymes during Growth and Fruiting Body Development of White Rot Fungi Omphalina sp. and Pleurotus ostreatus. Hayati 2008, 15, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morán Arellanos, T.; Bautista Ortega, J.; Sobal Cruz, M.; Rosales Martínez, V.; Martínez, B.C.; Huicab Pech, Z.G. Potencial Biotecnológico de Residuos Vegetales Para Producir Pleurotus Ostreatus En Zonas Rurales de Campeche. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agric. 2020, 11, 685–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jesús-Rivera, L.; Álvarez-Sánchez, M.E.; Ramírez-Pérez, F.; Maldonado-Torres, R. Glóquidas de Tuna Para La Producción Comercial de Hongo Seta. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agric. 2022, 13, 1445–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Arenas, O.; Ángeles Valencia-De Ita, M.; Rivera-Tapia, J.A.; Tello-Salgado, I.; Villarreal Espino-Barros, O.A.; Ángel Damián-Huato, M. Capacidad productiva de Pleurotus ostreatus utilizando alfalfa deshidratada como suplemento en diferentes sustratos agrícolas productive capacity of pleurotus ostreatus using dehydrated alfalfa as supplement in different agricultural substrates. Agric. Soc. Desarro. 2018, 15, 145–160. [Google Scholar]

- Corrêa, R.C.G.; Brugnari, T.; Bracht, A.; Peralta, R.M.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Biotechnological, Nutritional and Therapeutic Uses of Pleurotus spp. (Oyster mushroom) Related with Its Chemical Composition: A Review on the Past Decade Findings. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aditya; Neeraj; Jarial, R.S.; Jarial, K.; Bhatia, J.N. Comprehensive Review on Oyster Mushroom Species (Agaricomycetes): Morphology, Nutrition, Cultivation and Future Aspects. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zervakis, G.; Balis, C. A Pluralistic Approach in the Study of Pleurotus Species with Emphasis on Compatibility and Physiology of the European Morphotaxa. Mycol. Res. 1996, 100, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunyard, B.A.; Chaichuchote, S.; Nicholson, M.S.; Royse, D.J. Ribosomal DNA Analysis for Resolution of Genotypic Classes of Pleurotus. Mycol. Res. 1996, 100, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Han, L.-H.; Liu, X.-B.; Zhao, Z.-W.; Yang, Z.L. The Saprotrophic Pleurotus Ostreatus Species Complex: Late Eocene Origin in East Asia, Multiple Dispersal, and Complex Speciation. IMA Fungus 2020, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avin, F.A.; Bhassu, S.; Tan, Y.S.; Shahbazi, P.; Vikineswary, S. Molecular Divergence and Species Delimitation of the Cultivated Oyster Mushrooms: Integration of IGS1 and ITS. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 793414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.; Yan, Z.-F.; Kook, M.; Li, C.-T.; Yi, T.-H. Genetic and Chemical Diversity of Edible Mushroom Pleurotus Species. Biomed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 6068185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.-L.; Li, Q.; Peng, W.-H.; Zhou, J.; Cao, X.-L.; Wang, D.; Huang, Z.-Q.; Tan, W.; Li, Y.; Gan, B.-C. Intra- and Inter-Isolate Variation of Ribosomal and Protein-Coding Genes in Pleurotus: Implications for Molecular Identification and Phylogeny on Fungal Groups. BMC Microbiol. 2017, 17, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilas, P.M.; Jadhav, A.C.; Dhavale, M.C.; Hasabnis, S.N.; Gaikwad, A.P.; Jadhav, P.R.; Ajit, P.S. Molecular Diversity among Wild Edible Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus spp.) from Western Ghat of Maharashtra. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2020, 9, 1394–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.-H.; Lee, G.-A.; Lee, S.-Y.; Gwag, J.-G.; Kim, T.-S.; Kong, W.-S.; Seo, K.-I.; Lee, G.-S.; Park, Y.-J. Development and Characterization of New Microsatellite Markers for the Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus). J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 19, 851–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoch, C.L.; Seifert, K.A.; Huhndorf, S.; Robert, V.; Spouge, J.L.; Levesque, C.A.; Chen, W.; Bolchacova, E.; Voigt, K.; Crous, P.W.; et al. Nuclear Ribosomal Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) Region as a Universal DNA Barcode Marker for Fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 6241–6246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulmalk, H.W. Rapid Differentiation of Pleurotus ostreatus from Pleurotus sapidus Using PCR Technique. J. Univ. Zakho 2013, 1, 153–157. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Estrada, A.E.; Jimenez-Gasco, M.d.M.; Royse, D.J. Pleurotus eryngii Species Complex: Sequence Analysis and Phylogeny Based on Partial EF1α and RPB2 Genes. Fungal Biol. 2010, 114, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbanelli, S.; Della Rosa, V.; Punelli, F.; Porretta, D.; Reverberi, M.; Fabbri, A.A.; Fanelli, C. DNA-Fingerprinting (AFLP and RFLP) for Genotypic Identification in Species of the Pleurotus eryngii Complex. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 74, 592–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellemain, E.; Carlsen, T.; Brochmann, C.; Coissac, E.; Taberlet, P.; Kauserud, H. ITS as an Environmental DNA Barcode for Fungi: An in Silico Approach Reveals Potential PCR Biases. BMC Microbiol. 2010, 10, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, P.; Labarère, J. Phylogenetic Relationships of Pleurotus Species According to the Sequence and Secondary Structure of the Mitochondrial Small-Subunit RRNA V4, V6 and V9 Domains The GenBank Accession Numbers for the Sequences Reported in This Paper Are given in Methods. Microbiology 2000, 146, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aref Hasan, H.; Mohamad Almomany, A.; Hasan, S.; Al-Abdallat, A.M. Assessment of Genetic Diversity among Pleurotus spp. Isolates from Jordan. J. Fungi 2018, 4, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koshi, D.; Ueshima, H.; Kawauchi, M.; Nakazawa, T.; Sakamoto, M.; Hirata, M.; Izumitsu, K.; Sumita, T.; Irie, T.; Honda, Y. Marker-Free Genome Editing in the Edible Mushroom, Pleurotus ostreatus, Using Transient Expression of Genes Required for CRISPR/Cas9 and for Selection. J. Wood Sci. 2022, 68, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pánek, M.; Wiesnerová, L.; Jablonský, I.; Novotný, D.; Tomšovský, M. What Is Cultivated Oyster Mushroom? Phylogenetic and Physiological Study of Pleurotus ostreatus and Related Taxa. Mycol. Prog. 2019, 18, 1173–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekowati, N.; Mumpuni, A.; Muljowati, J.S.; Ratnaningtyas, N.I.; Maharning, A.R. Genetic Diversity of Pleurotus ostreatus (Jacq.) P. Kumm. Strains in Java Based on Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA Markers. Biodiversitas 2021, 22, 3488–3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhao, S.; Xu, F. Examining Genetic Relationships of Chinese Pleurotus ostreatus Cultivars by Combined RAPD and SRAP Markers. Mycoscience 2013, 54, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atila, F. Evaluation of Suitability of Various Agro-Wastes for Productivity of Pleurotus djamor, Pleurotus citrinopileatus and Pleurotus eryngii Mushrooms. J. Exp. Agric. Int. 2017, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akcay, C.; Ceylan, F.; Arslan, R. Production of Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus Ostreatus) from Some Waste Lignocellulosic Materials and FTIR Characterization of Structural Changes. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doroški Petković, A.; Klaus, A.; Vunduk, J.; Cvetković, S.; Nikolić, B.; Rabrenović, B.; Tomasevic, I.; Djekic, I. Pleurotus Ostreatus Cultivation for More Sustainable Soybean and Sunflower Seed Waste Management. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 339, 113866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotti, M.; Cecchi, G.; Canonica, L.; Di Piazza, S. A Review of Nature-Based Solutions for Valorizing Aromatic Plants’ Lignocellulosic Waste Through Oyster Mushroom Cultivation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gałązka, A.; Jankiewicz, U.; Orzechowski, S. The Role of Ligninolytic Enzymes in Sustainable Agriculture: Applications and Challenges. Agronomy 2025, 15, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bonis, M.; Sambo, P.; Zanin, G.; Cardarelli, M.; Nicoletto, C. Spent Pleurotus Substrate as Organic Fertilizer to Improve Yield and Soil Fertility: The Case of Baby Leaf Lettuce Production. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2025, 105, 5874–5886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, P.; Wang, M.; Cui, Y.; Tuo, Y.; Zhao, B.; Wang, N. Evaluation of Chemical Properties and Humification Process during Co-Composting of Spent Mushroom Substrate (Pleurotus Ostreatus) and Pig Manure under Different Mass Ratios. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2024, 193, 105858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]