Socio-Economic and Environmental Benefits of Agroforestry and Its Multilevel Barriers to Adoption: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

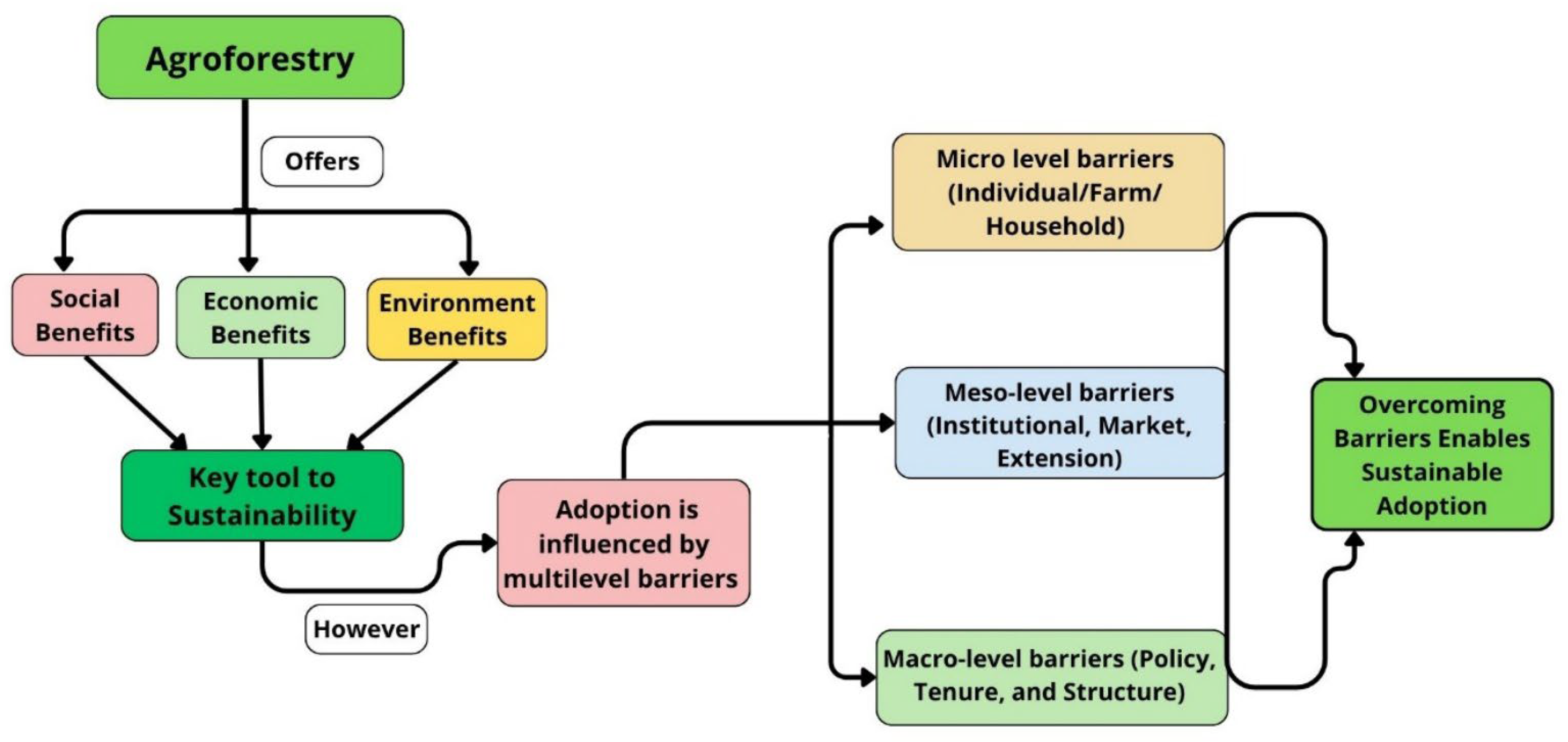

- What socio-economic and environmental benefits of agroforestry are reported?

- How do these benefits support long-term sustainability?

- Why are farmers not adopting agroforestry practices despite several benefits?

- What types of barriers exist at micro, meso, and macro levels?

2. Methodology

2.1. The PRISMA Approach

2.2. Database Identification and Screening

- (i)

- The study focuses on at least one of the agroforestry or its different types

- (ii)

- Different benefits (social, economic, and environmental) to the small farmers

- (iii)

- Addressing challenges or adoption barriers of agroforestry

2.3. Eligibility: Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Analysis

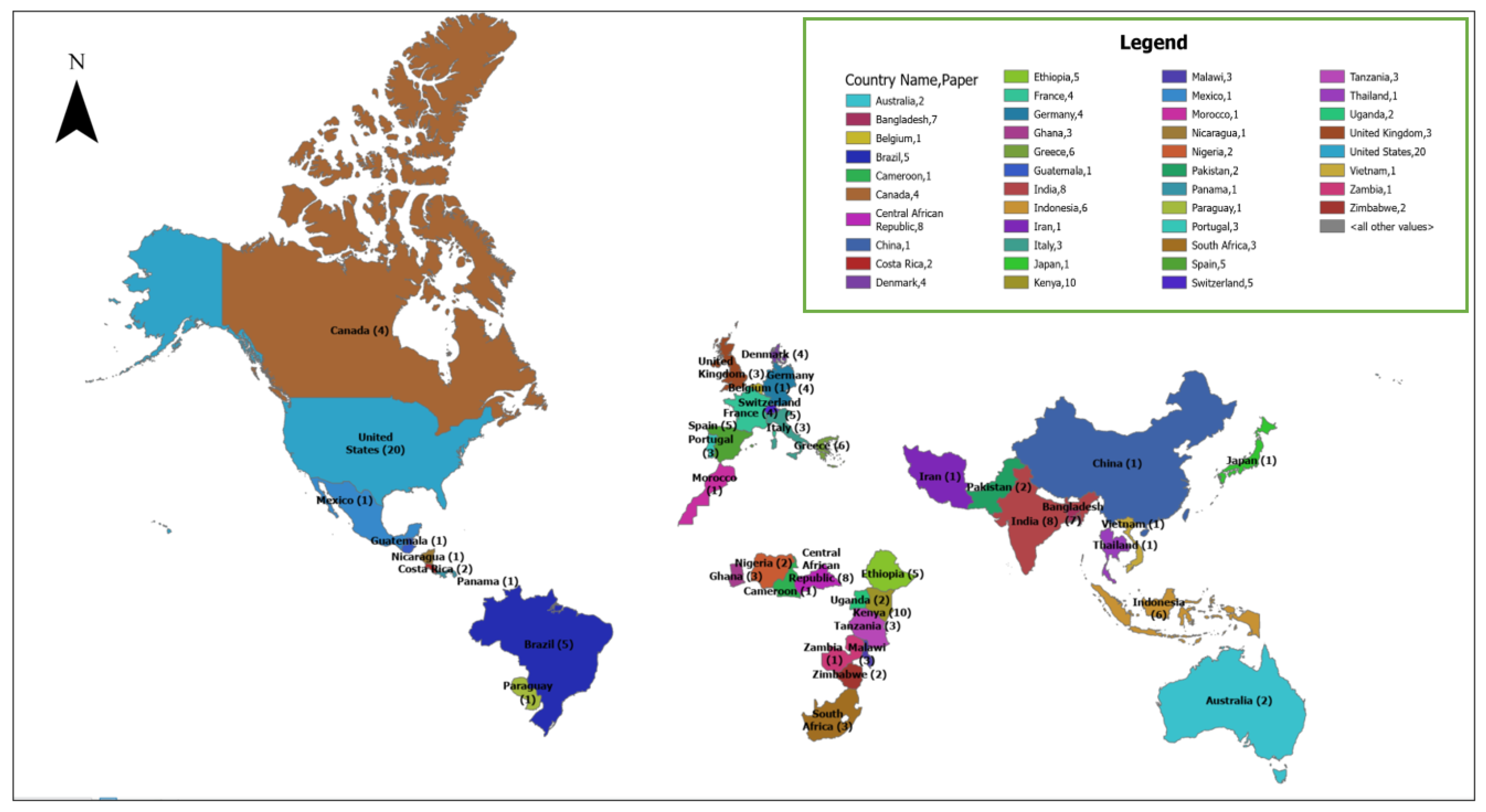

3.1.1. Geographical Locations of Reviewed Articles

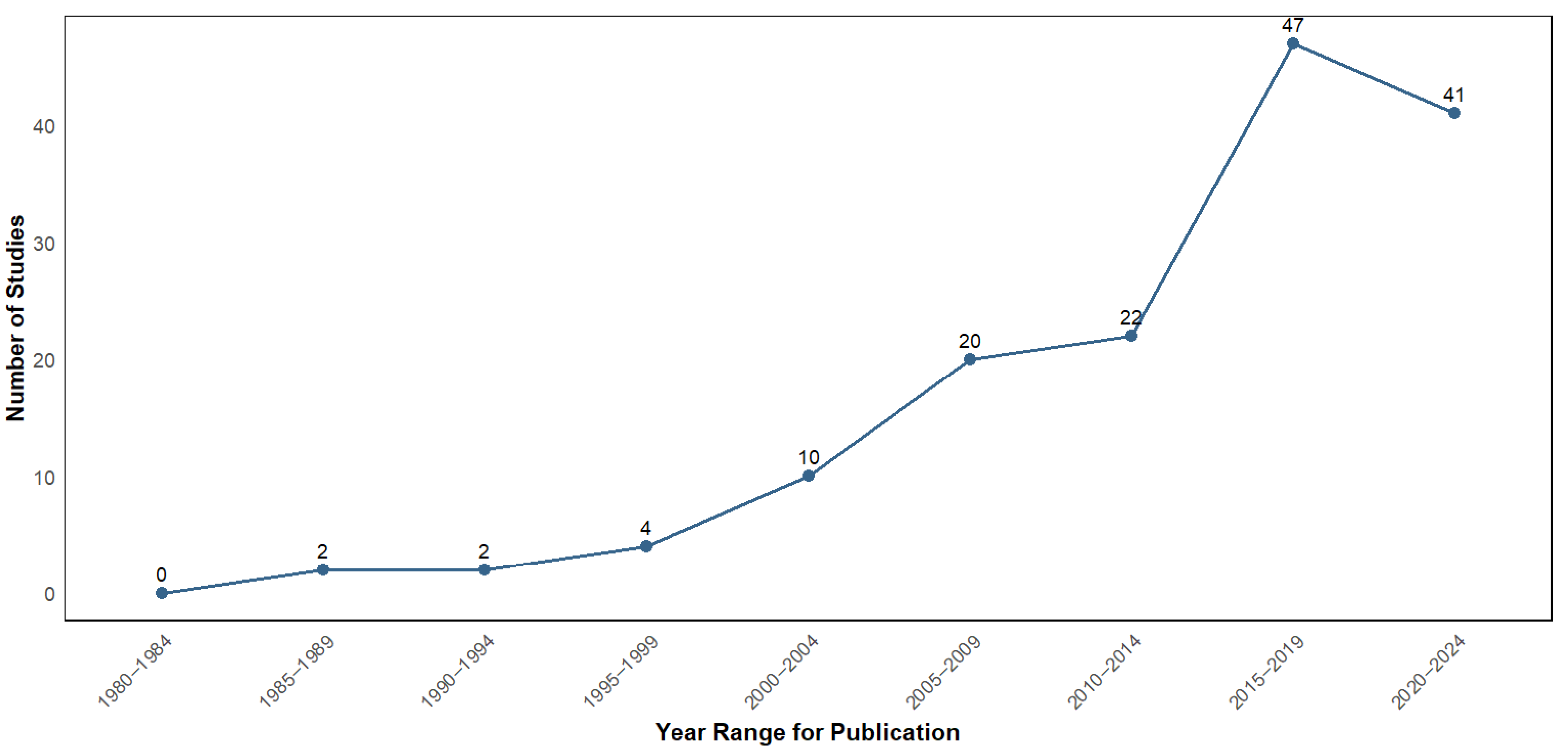

3.1.2. Publication per Year

3.1.3. Reviewed Articles Consisting of Social, Economic, and Environmental Benefits with Their Barriers to Adoption

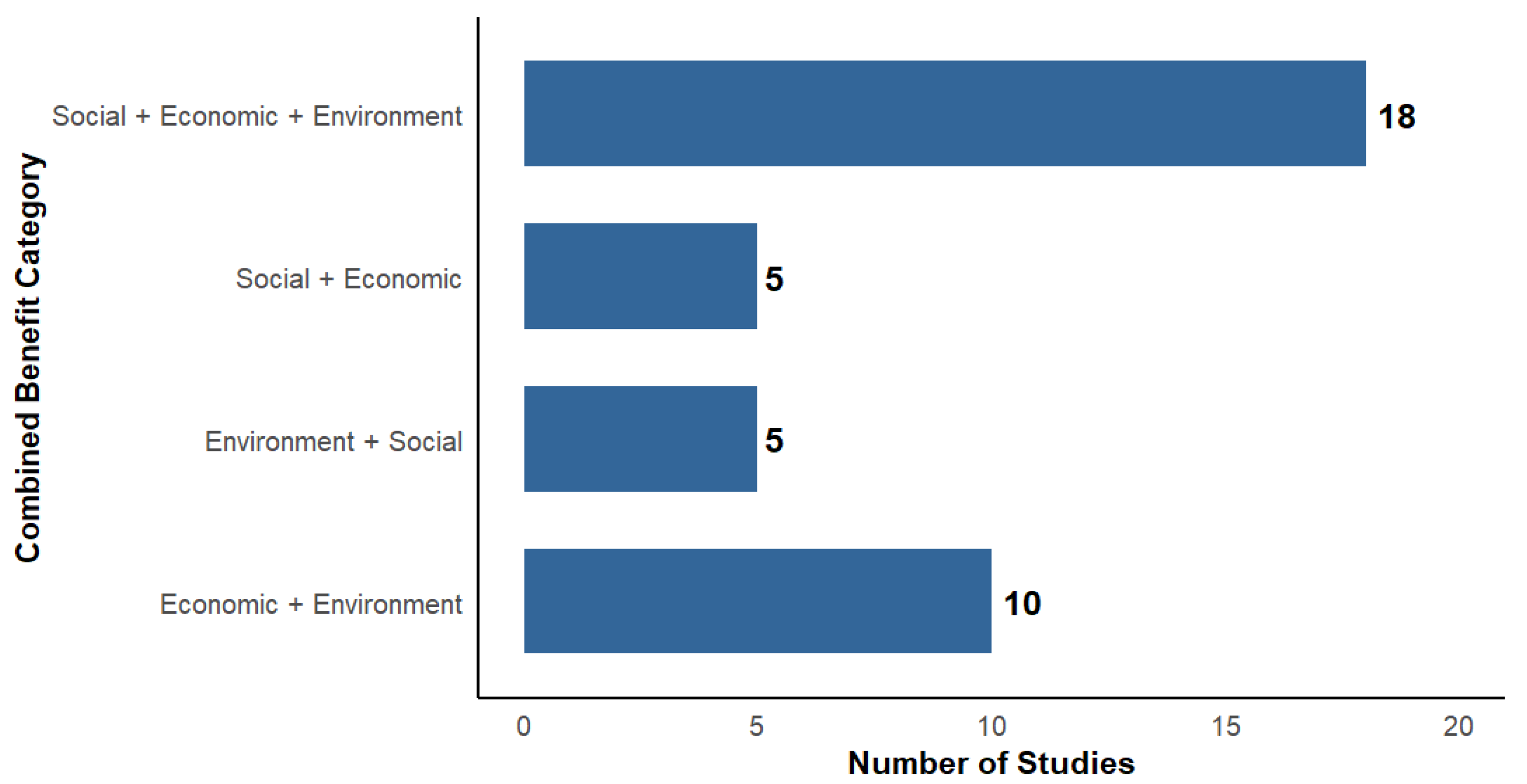

3.1.4. Reviewed Articles Consisting of Combined Benefits

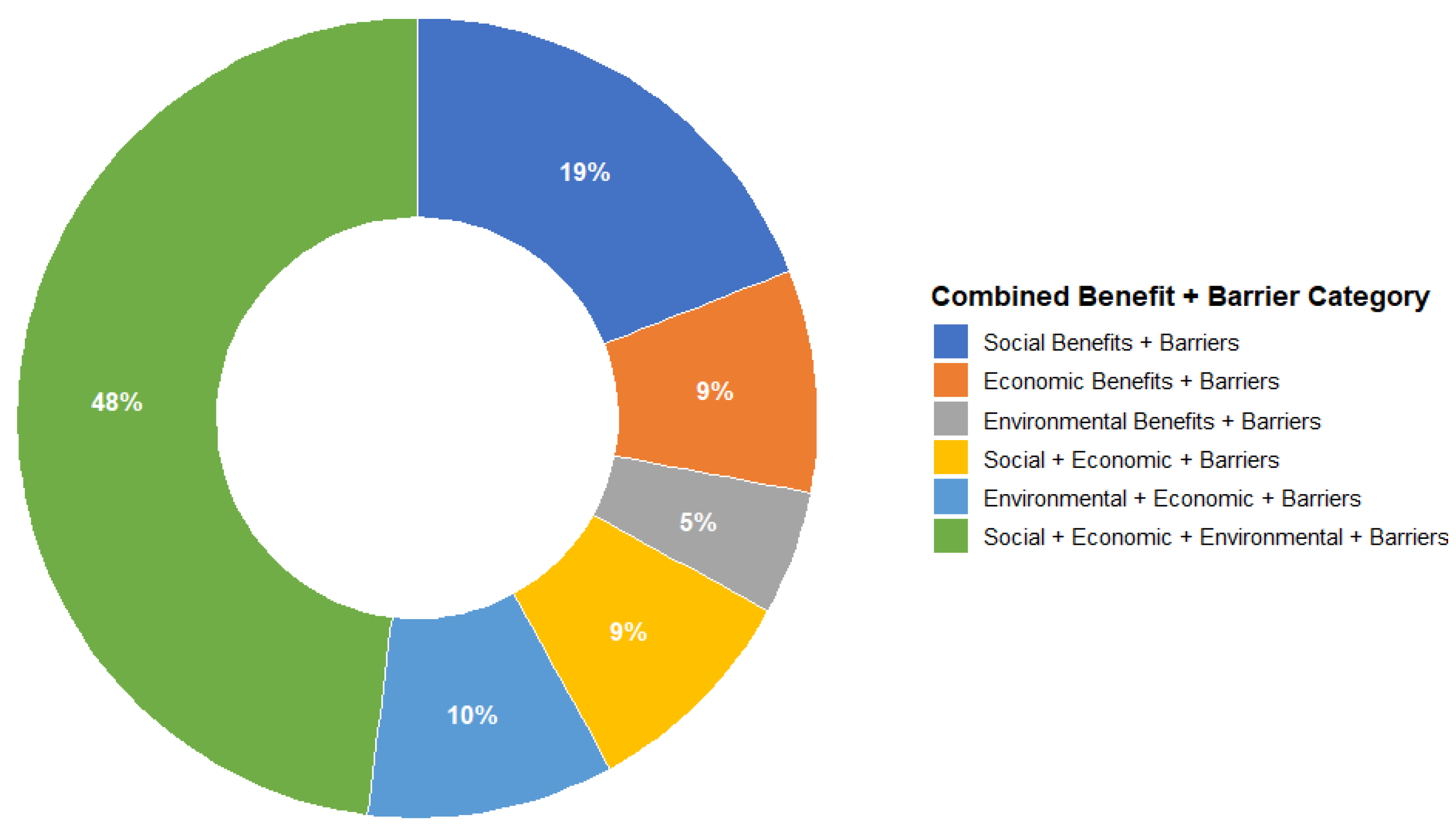

3.1.5. Reviewed Articles Consisting of Combined Benefits, Including Barriers

3.2. Qualitative Analysis: Explored Benefits of Agroforestry from Reviewed Articles

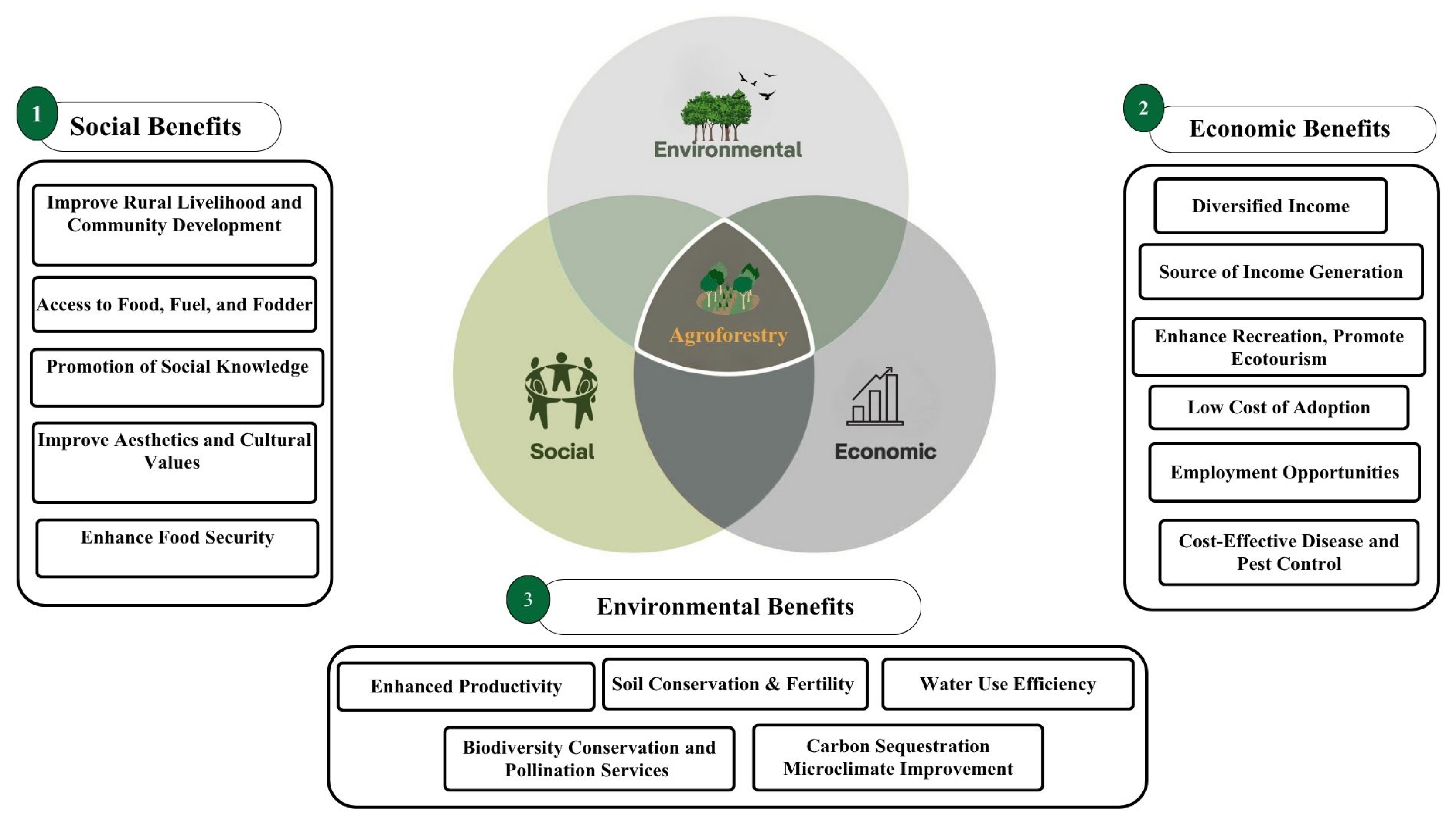

3.2.1. Social Benefits

Improve Rural Livelihood and Community Development

Access to Food, Fuel, and Fodder

Promotion of Social Knowledge

Improve Aesthetics and Cultural Values

Enhance Food Security

3.2.2. Economic Benefits

Diversified Income

Source of Income Generation

Enhance Recreation, Promote Ecotourism

Low Cost of Adoption

Employment Opportunities

Cost-Effective Disease and Pest Control

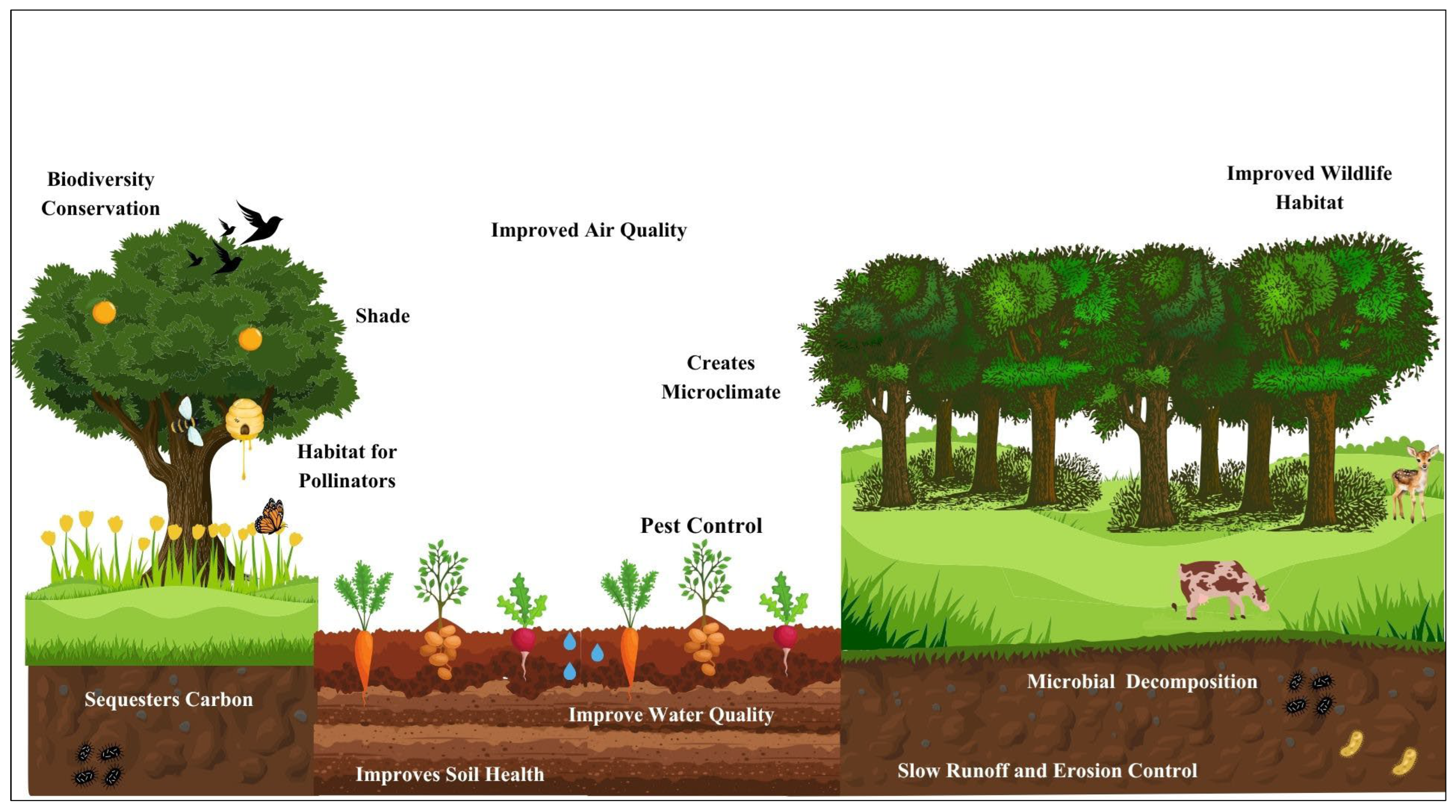

3.2.3. Environmental Benefits

Enhanced Productivity

Soil Conservation and Enhancing Soil Fertility

Enhance Water Use Efficiency and Erosion Control

Biodiversity Conservation and Pollination Services

Carbon Sequestration

Microclimate Improvement

3.3. Adoption Barriers to Agroforestry Systems

3.3.1. Micro-Level Barriers for Adopting Agroforestry Systems

3.3.2. Meso-Level Barriers for Adopting Agroforestry Systems

3.3.3. Macro-Level Barriers for Adopting Agroforestry Systems

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). The Future of Food and Agriculture—Alternative Pathways to 2050; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/I8429EN/i8429en.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Flies, E.J.; Brook, B.W.; Blomqvist, L.; Buettel, J.C. Forecasting Future Global Food Demand: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Model Complexity. Environ. Int. 2018, 120, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchie, H.; Roser, M. Half of the World’s Habitable Land Is Used for Agriculture. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/global-land-for-agriculture (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO); International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD); United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF); World Food Programme (WFP); World Health Organization (WHO). The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023: Urbanization, Agrifood Systems Transformation and Healthy Diets Across the Rural–Urban Continuum; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023; Available online: https://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/cc3017en (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Akanmu, A.O.; Akol, A.M.; Ndolo, D.O.; Kutu, F.R.; Babalola, O.O. Agroecological Techniques: Adoption of Safe and Sustainable Agricultural Practices among the Smallholder Farmers in Africa. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1143061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, A.G.; Eusebio, G.d.S.; Fasiaben, M.d.C.R.; Moraes, A.S.; Assad, E.D.; Pugliero, V.S. The Economic Impacts of the Diffusion of Agroforestry in Brazil. Land Use Policy 2021, 108, 105489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskandar, J.; Iskandar, B.S.; Partasasmita, R. Responses to Environmental and Socio-Economic Changes in the Karangwangi Traditional Agroforestry System, South Cianjur, West Java. Biodiversitas 2016, 17, 332–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). UNESCO Raises Global Alarm on the Rapid Degradation of Soils. 2024. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/unesco-raises-global-alarm-rapid-degradation-soils (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Richardson, K.; Steffen, W.; Lucht, W.; Bendtsen, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Donges, J.F.; Drüke, M.; Fetzer, I.; Bala, G.; von Bloh, W.; et al. Earth Beyond Six of Nine Planetary Boundaries. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadh2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amundson, R. Soil and Human Security in the 21st Century. Science 2015, 348, 1261071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The European Commission’s Priorities. 2024. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/priorities-2024-2029_en (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Chatterjee, A.; Lal, R.; Wielopolski, L.; Martin, M.Z.; Ebinger, M.H. Evaluation of Different Soil Carbon Determination Methods. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2009, 28, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, H.; Godfray, H.; Garnett, T. Food Security and Sustainable Intensification. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 369, 20120273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, J.P.; Reckziegel, R.B.; Borrass, L.; Chirwa, P.W.; Cuaranhua, C.J.; Hassler, S.K.; Hoffmeister, S.; Kestel, F.; Maier, R.; Mälicke, M.; et al. Agroforestry: An Appropriate and Sustainable Response to a Changing Climate in Southern Africa? Sustainability 2020, 12, 6796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, P.R. The Coming of Age of Agroforestry. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2007, 87, 1613–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Noordwijk, M. Agroforestry as Nexus of Sustainable Development Goals. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 449, 012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zomer, R.J.; Euro-Mediterraneo, C.; Climatici, C.; Trabucco, A.; Coe, R. Trees on Farms: An Update and Reanalysis of Agroforestry’s Global Extent and Socio-Ecological Characteristics; World Agroforestry Centre: Bogor, Indonesia, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perfecto, I.; Vandermeer, J. Biodiversity Conservation in Tropical Agroecosystems. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1134, 173–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jose, S.; Udawatta, R.P. Agroforestry and Ecosystem Services; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 9783030800604. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, P.K.R. Agroforestry Systems and Environmental Quality: Introduction. J. Environ. Qual. 2011, 40, 784–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castle, S.E.; Miller, D.C.; Ordonez, P.J.; Baylis, K.; Hughes, K. The Impacts of Agroforestry Interventions on Agricultural Productivity, Ecosystem Services, and Human Well-Being in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2021, 17, e1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhlman, T.; Farrington, J. What Is Sustainability? Sustainability 2010, 2, 3436–3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M.A.; Gregory, P.J. Soil, Food Security and Human Health: A Review. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2015, 66, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, S. Agroforestry for Ecosystem Services and Environmental Benefits: An Overview. Agrofor. Syst. 2009, 76, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udawatta, R.P.; Rankoth, L.M.; Jose, S. Agroforestry and Biodiversity. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, P.K.R.; Kumar, B.M.; Nair, V.D. Agroforestry as a Strategy for Carbon Sequestration. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2009, 172, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhlis, I.; Syamsu Rizaludin, M.; Hidayah, I. Understanding Socio-Economic and Environmental Impacts of Agroforestry on Rural Communities. Forests 2022, 13, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, T.; Sprunger, C.D. Sensitive Measures of Soil Health Reveal Carbon Stability Across a Management Intensity and Plant Biodiversity Gradient. Front. Soil Sci. 2022, 2, 917885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D.R. Soil Health and the Revolutionary Potential of Conservation Agriculture. In Rethinking Food and Agriculture: New Ways Forward; Woodhead Publishing: London, UK, 2021; pp. 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christin, Z.L.; Bagstad, K.J.; Verdone, M.A. A Decision Framework for Identifying Models to Estimate Forest Ecosystem Services Gains from Restoration. For. Ecosyst. 2016, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauss, J. What Is Cocoa Sustainability? Mapping Stakeholders’ Socio-Economic, Environmental, and Commercial Constellations of Priorities. Enterp. Dev. Microfinance 2017, 28, 228–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulibaly, J.Y.; Chiputwa, B.; Nakelse, T.; Kundhlande, G. Adoption of Agroforestry and the Impact on Household Food Security among Farmers in Malawi. Agric. Syst. 2017, 155, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheiri, M.; Kambouzia, J.; Sayahnia, R.; Soufizadeh, S.; Mahdavi Damghani, A.; Azadi, H. Environmental and Socioeconomic Assessment of Agroforestry Implementation in Iran. J. Nat. Conserv. 2023, 72, 126358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Noordwijk, M.; Tomich, T.P.; Verbist, B. Negotiation Support Models for Integrated Natural Resource Management in Tropical Forest Margins. Ecol. Soc. 2002, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gochera, A.; Worku, H. Mangifera indica (L.) Tree as Agroforestry Component: Environmental and Socio-Economic Roles in Abaya-Chamo Catchments of the Southern Rift Valley of Ethiopia. Cogent Food Agric. 2022, 8, 2098587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, S. Agroforestry for Conserving and Enhancing Biodiversity. Agrofor. Syst. 2012, 85, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmott, A.; Willmott, M.; Grass, I.; Lusiana, B.; Cotter, M. Harnessing the Socio-Ecological Benefits of Agroforestry Diversification in Social Forestry with Functional and Phylogenetic Tools. Environ. Dev. 2023, 47, 100881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montambault, J.R.; Alavalapati, J.R.R. Socioeconomic Research in Agroforestry: A Decade in Review. Agrofor. Syst. 2005, 65, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, T.; Wilkes, A.; Jallo, C.; Namoi, N.; Bulusu, M.; Suber, M.; Bernard, F.; Mboi, D.; Mulia, R.; Simelton, E.; et al. Making trees count: Measurement, Reporting and Verification of Agroforestry under the UNFCCC. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 284, 106569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, A.; Kandji, S.T. Carbon Sequestration in Tropical Agroforestry Systems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2003, 99, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, R.P.; Ligonja, P.J. Social Perception of Soil Conservation Benefits in Kondoa Eroded Area of Tanzania. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2015, 3, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavalapati, J.R.; Shrestha, R.K.; Stainback, G.A.; Matta, J.R. Agroforestry Development: An Environmental Economic Perspective. In New Vistas in Agroforestry; Nair, P.K.R., Rao, M.R., Buck, L.E., Eds.; Advances in Agroforestry; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2004; Volume 1, pp. 299–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köthke, M.; Ahimbisibwe, V.; Lippe, M. The Evidence Base on the Environmental, Economic and Social Outcomes of Agroforestry Is Patchy—An Evidence Review Map. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 925477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amare, D.; Darr, D. Farmers’ Intentions Toward Sustained Agroforestry Adoption: An Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Sustain. For. 2022, 42, 869–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service (USDA NASS). USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service. 2024. Available online: https://www.nass.usda.gov (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Mazhar, R.; Ghafoor, A.; Xuehao, B.; Wei, Z. Fostering Sustainable Agriculture: Do Institutional Factors Impact the Adoption of Multiple Climate-Smart Agricultural Practices Among New Entry Organic Farmers in Pakistan? J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 283, 124620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyani, P.; Andoh, J.; Lee, Y.; Lee, D.K. Benefits and Challenges of Agroforestry Adoption: A Case of Musebeya Sector, Nyamagabe District in Southern Province of Rwanda. For. Sci. Technol. 2017, 13, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, G.G.; Nair, P.K.R.; Duffy, C.P.; Franzel, S.C. Constraints to the Adoption of Fodder Tree Technology in Malawi. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 12, 641–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouassi, J.-L.; Kouassi, A.; Bene, Y.; Konan, D.; Tondoh, E.J.; Kouame, C. Exploring Barriers to Agroforestry Adoption by Cocoa Farmers in South-Western Côte d’Ivoire. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkomoki, W.; Bavorová, M.; Banout, J. Adoption of Sustainable Agricultural Practices and Food Security Threats: Effects of Land Tenure in Zambia. Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.C.; Ordoñez, P.J.; Brown, S.E.; Forrest, S.; Nava, N.J.; Hughes, K.; Baylis, K. The Impacts of Agroforestry on Agricultural Productivity, Ecosystem Services, and Human Well-Being in Low-and Middle-Income Countries: An Evidence and Gap Map. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2020, 16, e1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancin, S.; Sguanci, M.; Andreoli, D.; Soekeland, F.; Anastasi, G.; Piredda, M.; De Marinis, M.G. Systematic Review of Clinical Practice Guidelines and Systematic Reviews: A Method for Conducting Comprehensive Analysis. MethodsX 2024, 12, 102532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 371, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finfgeld-Connett, D. Use of Content Analysis to Conduct Knowledge-Building and Theory-Generating Qualitative Systematic Reviews. Qual. Res. 2014, 14, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templier, M.; Paré, G. A Framework for Guiding and Evaluating Literature Reviews. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2015, 37, 112–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusenbauer, M.; Haddaway, N.R. Which Academic Search Systems Are Suitable for Systematic Reviews or Meta-Analyses? Evaluating Retrieval Qualities of Google Scholar, PubMed, and 26 Other Resources. Res. Synth. Methods 2020, 11, 181–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacFarlane, A.; Russell-Rose, T.; Shokraneh, F. Search Strategy Formulation for Systematic Reviews: Issues, Challenges and Opportunities. Intell. Syst. Appl. 2022, 15, 200091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; MacQueen, K.; Namey, E. Applied Thematic Analysis; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkansah-Dwamena, E. Why Small-Scale Circular Agriculture Is Central to Food Security and Environmental Sustainability in Sub-Saharan Africa? The Case of Ghana. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2023, 4, 995–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Octavia, D.; Suharti, S.; Murniati; Dharmawan, I.W.S.; Nugroho, H.Y.S.H.; Supriyanto, B.; Rohadi, D.; Njurumana, G.N.; Yeny, I.; Hani, A.; et al. Mainstreaming Smart Agroforestry for Social Forestry Implementation to Support Sustainable Development Goals in Indonesia: A Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.M.; Takeuchi, K. Agroforestry in the Western Ghats of Peninsular India and the Satoyama Landscapes of Japan: A Comparison of Two Sustainable Land Use Systems. Sustain. Sci. 2009, 4, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.; Bezner Kerr, R.; Deryng, D.; Farrell, A.; Gurney-Smith, H.; Thornton, P. Mixed Farming Systems: Potentials and Barriers for Climate Change Adaptation in Food Systems. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2023, 62, 101270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.K.; Sharma, A.; Singh, G.S. Traditional Agricultural Practices in India: An Approach for Environmental Sustainability and Food Security. Energy Ecol. Environ. 2020, 5, 253–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Bohra, B.; Pragya, N.; Ciannella, R.; Dobie, P.; Lehmann, S. Bioenergy from Agroforestry Can Lead to Improved Food Security, Climate Change, Soil Quality, and Rural Development. Food Energy Secur. 2016, 5, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlidis, G.; Tsihrintzis, V.A. Environmental Benefits and Control of Pollution to Surface Water and Groundwater by Agroforestry Systems: A Review. Water Resour. Manag. 2018, 32, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemagi, D.; Duguma, L.; Minang, P.A.; Nkeumoe, F.; Feudjio, M.; Tchoundjeu, Z. Intensification of Cocoa Agroforestry Systems as a REDD+ Strategy in Cameroon: Hurdles, Motivations, and Challenges. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2015, 13, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iiyama, M.; Neufeldt, H.; Dobie, P.; Njenga, M.; Ndegwa, G.; Jamnadass, R. The Potential of Agroforestry in the Provision of Sustainable Woodfuel in Sub-Saharan Africa. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2014, 6, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvache, M.F.; Santos, R.; Antunes, P.; Santos-Reis, M. Long-Term Monitoring of Mediterranean Socio-Ecological Systems. Agrofor. Syst. 2021, 95, 459–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mganga, K.Z.; Musimba, N.K.R.; Nyariki, D.M. Combining Sustainable Land Management Technologies to Combat Land Degradation and Improve Rural Livelihoods in Semi-Arid Lands in Kenya. Environ. Manag. 2015, 56, 1538–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, R.; Hasan, M.K.; Kabir, K.H.; Darr, D.; Roshni, N.A. Agroforestry Systems and Their Impact on Livelihood Improvement of Tribal Farmers in a Tropical Moist Deciduous Forest in Bangladesh. Trees For. People 2022, 9, 100315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, A.J.; Correa Cano, M.E.; Parkes, B. The Deployment of Intercropping and Agroforestry as Adaptation to Climate Change. Crop Environ. 2022, 1, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiptot, E.; Franzel, S.; Degrande, A. Gender, Agroforestry and Food Security in Africa. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2014, 6, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadele, M.; Birhane, E.; Kidu, G.; G-Wahid, H.; Rannestad, M.M. Contribution of Parkland Agroforestry in Meeting Fuel Wood Demand in the Dry Lands of Tigray, Ethiopia. J. Sustain. For. 2020, 39, 841–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbow, C.; Van Noordwijk, M.; Luedeling, E.; Neufeldt, H.; Minang, P.A.; Kowero, G. Agroforestry Solutions to Address Food Security and Climate Change Challenges in Africa. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2014, 6, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njenga, M.; Gitau, J.K.; Iiyama, M.; Jamnadassa, R.; Mahmoud, Y.; Karanja, N. Innovative Biomass Cooking Approaches for Sub-Saharan Africa. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2019, 19, 14066–14087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemel, S.A.K.; Hasan, M.K.; Akter, R.; Roshni, N.A.; Sayem, A.; Rasul, S.; Islam, M.T. Delving into Piper Chaba- Based Agroforestry System in Northern Bangladesh: Ecosystem Services, Environmental Benefits, and Potential Conservation Initiatives. Trees For. People 2024, 16, 100523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ickowitz, A.; Rowland, D.; Powell, B.; Salim, M.A.; Sunderland, T. Forests, Trees, and Micronutrient-Rich Food Consumption in Indonesia. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0154139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parra-López, C.; Sayadi, S.; Garcia-Garcia, G.; Ben Abdallah, S.; Carmona-Torres, C. Prioritising Conservation Actions Towards the Sustainability of the Dehesa by Integrating the Demands of Society. Agric. Syst. 2023, 206, 103613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosrenaud, E.; Okia, C.A.; Adam-Bradford, A.; Trenchard, L. Agroforestry: Challenges and Opportunities in Rhino Camp and Imvepi Refugee Settlements of Arua District, Northern Uganda. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungmachon, M.R. Knowledge and Local Wisdom: Community Treasure. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2012, 2, 174–181. [Google Scholar]

- Nath, T.K.; Jashimuddin, M.; Kamrul Hasan, M.; Shahjahan, M.; Pretty, J. The Sustainable Intensification of Agroforestry in Shifting Cultivation Areas of Bangladesh. Agrofor. Syst. 2016, 90, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdam, J.H.; Burgess, P.J.; Graves, A.R.; Rigueiro-Rodríguez, A.; Mosquera-Losada, M.R. Classifications and Functions of Agroforestry Systems in Europe; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 6, pp. 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentrup, G.; Hopwood, J.; Adamson, N.L.; Vaughan, M. Temperate Agroforestry Systems and Insect Pollinators: A Review. Forests 2019, 10, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, G.; Aviron, S.; Berg, S.; Crous-Duran, J.; Franca, A.; de Jalón, S.G.; Hartel, T.; Mirck, J.; Pantera, A.; Palma, J.H.N.; et al. Agroforestry Systems of High Nature and Cultural Value in Europe: Provision of Commercial Goods and Other Ecosystem Services. Agrofor. Syst. 2018, 92, 877–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanastasis, V.P.; Mantzanas, K.; Dini-Papanastasi, O.; Ispikoudis, I. Traditional Agroforestry Systems and Their Evolution in Greece. In Advances in Agroforestry; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 6, pp. 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, C.; Valdivia, C. Recreation and Agroforestry: Examining New Dimensions of Multifunctionality in Family Farms. J. Rural Stud. 2010, 26, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, N.; Jacobson, M.G. A Case for Consumer-Driven Extension Programming: Agroforestry Adoption Potential in Pennsylvania. Agrofor. Syst. 2006, 68, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrity, D.P.; Akinnifesi, F.K.; Ajayi, O.C.; Weldesemayat, S.G.; Mowo, J.G.; Kalinganire, A.; Larwanou, M.; Bayala, J. Evergreen Agriculture: A Robust Approach to Sustainable Food Security in Africa. Food Secur. 2010, 2, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, R.K.; Alavalapati, J.R.R.; Kalmbacher, R.S. Exploring the Potential for Silvopasture Adoption in South-Central Florida: An Application of SWOT-AHP Method. Agric. Syst. 2004, 81, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorlakson, T.; Neufeldt, H. Reducing Subsistence Farmers’ Vulnerability to Climate Change: Evaluating the Potential Contributions of Agroforestry in Western Kenya. Agric. Food Secur. 2012, 1, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verchot, L.V.; Van Noordwijk, M.; Kandji, S.; Tomich, T.; Ong, C.; Albrecht, A.; Mackensen, J.; Bantilan, C.; Anupama, K.V.; Palm, C. Climate Change: Linking Adaptation and Mitigation through Agroforestry. Mitig. Adapt. Strat. Glob. Change 2007, 12, 901–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Admasu, T.G.; Jenberu, A.A. The Impacts of Apple-Based Agroforestry Practices on the Livelihoods of Smallholder Farmers in Southern Ethiopia. Trees For. People 2022, 7, 100205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, C.; Toth, G.G.; Hagan, R.P.O.; McKeown, P.C.; Rahman, S.A.; Widyaningsih, Y.; Sunderland, T.C.H.; Spillane, C. Agroforestry Contributions to Smallholder Farmer Food Security in Indonesia. Agrofor. Syst. 2021, 95, 1109–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, V.D.; Graetz, D.A. Agroforestry as an Approach to Minimizing Nutrient Loss from Heavily Fertilized Soils: The Florida Experience. Agrofor. Syst. 2004, 61, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, M.B.; Burgess, P.J.; Fike, J.H. Agroforestry for Healthy Ecosystems: Constraints, Improvement Strategies and Extension in Pakistan. Agrofor. Syst. 2021, 95, 995–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, L.; Krishnamurthy, P.K.; Rajagopal, I.; Peralta Solares, A. Can Agroforestry Systems Thrive in the Drylands? Characteristics of Successful Agroforestry Systems in the Arid and Semi-Arid Regions of Latin America. Agrofor. Syst. 2019, 93, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escribano, M.; Díaz-Caro, C.; Mesias, F.J. A Participative Approach to Develop Sustainability Indicators for Dehesa Agroforestry Farms. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 640–641, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, G.d.C.; Schlindwein, M.M.; Padovan, M.P.; Vogel, E.; Ruviaro, C.F. Environmental Performance of Agroforestry Systems in the Cerrado Biome, Brazil. World Dev. 2019, 122, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, T.H.; Khan, M.F.; Gilani, M.W.; Buajan, M.M.; Iftikhar, S.; Tunon, J.; Wu, N. Potentials of Agroforestry and Constraints Faced by the Farmers in Its Adoption in District Nankana Sahib, Pakistan. Int. J. Dev. Sustain. 2017, 6, 586–593. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.; Scherr, S.J. Forest Carbon and Local Livelihoods: Assessment of Opportunities and Policy Recommendations; CIFOR Occasional Paper No. 37; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Bogor, Indonesia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bellow, J.G.; Hudson, R.F.; Nair, P.K.R. Adoption Potential of Fruit-Tree-Based Agroforestry on Small Farms in the Subtropical Highlands. Agrofor. Syst. 2008, 73, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosier, R.H. The Economics of Smallholder Agroforestry: Two Case Studies. World Dev. 1989, 17, 1827–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, P.T. Designing Agroforestry Innovations to Increase Their Adoptability: A Case Study from Paraguay. J. Rural Stud. 1988, 4, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adane, F.; Legesse, A.; Welde Amanuel, T.; Belay, T. The Contribution of a Fruit Tree-Based Agro Forestry System for Household Income to Smallholder Farmers in Dale District, Sidama Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Adv. Plants Agric. Res. 2019, 9, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardini, A. Agroforestry Systems in Italy: Traditions Towards Modern Management. In Advances in Agroforestry; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 6, pp. 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Pearce, B.D.; Wolfe, M.S. Reconciling Productivity with Protection of the Environment: Is Temperate Agroforestry the Answer? Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2012, 28, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantera, A.; Papadopoulos, A.; Papanastasis, V.P. Valonia Oak Agroforestry Systems in Greece: An Overview. Agrofor. Syst. 2018, 92, 921–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, M.A.; Roy, R.M.; Bari, M.S.; Ray, P.C.; Rahman, M.S.; Hasan, M.F. Livelihood Improvements Through Agroforestry: Evidence from Northern Bangladesh. Small-Scale For. 2018, 17, 505–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, K.; Wadud, M.A.; Mondol, M.A.; Alam, Z.; Rahman, G.M.M. Impact of Agroforestry Practices on Livelihood Improvement of the Farmers of Char Kalibari Area of Mymensingh. J. Agrofor. Environ. 2011, 5, 77–80. [Google Scholar]

- Grado, S.C.; Husak, A.L. Economic Analyses of a Sustainable Agroforestry System in the Southeastern United States. In Valuing Agroforestry Systems. Advances in Agroforestry; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2004; Volume 2, pp. 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaba, K.F.; Chirwa, P.; Syampungani, S.; Ajayi, C.O. Contribution of Agroforestry to Biodiversity and Livelihoods Improvement in Rural Communities of Southern African Regions. In Environmental Science and Engineering; Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2010; pp. 461–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.E.; Miller, D.C.; Ordonez, P.J.; Baylis, K. Evidence for the Impacts of Agroforestry on Agricultural Productivity, Ecosystem Services, and Human Well-Being in High-Income Countries: A Systematic Map Protocol. Environ. Evid. 2018, 7, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duguma, B.; Gockowski, J.; Bakala, J. Smallholder Cacao (Theobroma cacao Linn.) Cultivation in Agroforestry Systems of West and Central Africa: Challenges and Opportunities. Agrofor. Syst. 2001, 51, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremen, C.; Iles, A.; Bacon, C. Diversified Farming Systems: An Agroecological, Systems-Based Alternative to Modern Industrial Agriculture. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, B.; Vishwakarma, A.; Padbhushan, R.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, R.; Kumari, R.; Kumar Yadav, B.; Giri, S.P.; Kaviraj, M.; Kumar, U. Hedge and Alder-Based Agroforestry Systems: Potential Interventions to Carbon Sequestration and Better Crop Productivity in Indian Sub-Himalayas. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 858948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quandt, A.; Neufeldt, H.; McCabe, J.T. Building Livelihood Resilience: What Role Does Agroforestry Play? Clim. Dev. 2018, 11, 485–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, D.; Acquay, H.; Biltonen, M.; Rice, P.; Silva, M.; Nelson, J.; Lipner, V.; Giordano, S.; Horowitz, A.; D’amore, M. Environmental and Economic Costs of Pesticide Use. BioScience 1992, 42, 750–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Liu, W.; Chen, J.; Bruijnzeel, L.A.; Mao, Z.; Yang, X.; Cardinael, R.; Meng, F.R.; Sidle, R.C.; Seitz, S.; et al. Reductions in Water, Soil, and Nutrient Losses and Pesticide Pollution in Agroforestry Practices: A Review of Evidence and Processes. Plant Soil 2020, 453, 45–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pumariño, L.; Sileshi, G.W.; Gripenberg, S.; Kaartinen, R.; Barrios, E.; Muchane, M.N.; Midega, C.; Jonsson, M. Effects of Agroforestry on Pest, Disease and Weed Control: A Meta-Analysis. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2015, 16, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sileshi, G.; Schroth, G.; Rao, M.R.; Girma, H. 5 Weeds, Diseases, Insect Pests, and Tri-Trophic Interactions in Tropical Agroforestry. Ecol. Basis Agrofor. 2007, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beule, L.; Corre, M.D.; Schmidt, M.; Göbel, L.; Veldkamp, E.; Karlovsky, P. Conversion of Monoculture Cropland and Open Grassland to Agroforestry Alters the Abundance of Soil Bacteria, Fungi and Soil-N-Cycling Genes. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samra, J.S.; Vishwanatham, M.K.; Sharma, A.R. Biomass Production of Trees and Grasses in a Silvopasture System on Marginal Lands of Doon Valley of North-West India 2. Performance of Grass Species. Agrofor. Syst. 1999, 46, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Lehmann, L.M.; De Jalón, S.G.; Ghaley, B.B. Assessment of Productivity and Economic Viability of Combined Food and Energy (Cfe) Production System in Denmark. Energies 2019, 12, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sereke, F.; Graves, A.R.; Dux, D.; Palma, J.H.N.; Herzog, F. Innovative Agroecosystem Goods and Services: Key Profitability Drivers in Swiss Agroforestry. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 35, 759–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, L.M.; Borzęcka, M.; Żyłowska, K.; Pisanelli, A.; Russo, G.; Ghaley, B.B. Environmental Impact Assessments of Integrated Food and Non-Food Production Systems in Italy and Denmark. Energies 2020, 13, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newaj, R.; Rai, P. Aonla-Based Agroforestry System: A Source of Higher Income under Rainfed Conditions. Indian Farming 2005, 55, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczak, K. Changes in Producer Attitudes Towards Windbreaks in Eastern Nebraska, 1983 to 2009. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, NE, USA, 2009. Available online: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/envstudtheses/1 (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Ferber, A.E.; Ford, A.L.; McCrory, S.A.; Ferber, A.E.; Ford, A.L. Good Windbreaks Help Increase South Dakota Crop Yields; Agricultural Experiment Station Circular No. 114; South Dakota State College, Agricultural Experiment Station: Brookings, SD, USA, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Bahadur, R. Impact of Multipurpose Trees on Productivity of Barley in Arid Ecosystem. Ann. Arid. Zone 1998, 37, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanish, S.A.; Sathya Priya, R. Review on Benefits of Agro Forestry System. Int. J. Agric. Sci. Res. 2013, 2, 80–91. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi Surki, A.; Nazari, M.; Fallah, S.; Iranipour, R.; Mousavi, A. The Competitive Effect of Almond Trees on Light and Nutrients Absorption, Crop Growth Rate, and the Yield in Almond–Cereal Agroforestry Systems in Semi-Arid Regions. Agrofor. Syst. 2020, 94, 1111–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, N.; Nair, P.K.R.; Chakraborty, S.; Nair, V.D. Changes in Soil Carbon Stocks across the Forest-Agroforest-Agriculture/Pasture Continuum in Various Agroecological Regions: A Meta-Analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 266, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udawatta, R.P.; Kremer, R.J.; Adamson, B.W.; Anderson, S.H. Variations in Soil Aggregate Stability and Enzyme Activities in a Temperate Agroforestry Practice. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2008, 39, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aertsens, J.; De Nocker, L.; Gobin, A. Valuing the Carbon Sequestration Potential for European Agriculture. Land Use Policy 2013, 31, 584–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambrick, A.D.; Whalen, J.K.; Bradley, R.L.; Cogliastro, A.; Gordon, A.M.; Olivier, A.; Thevathasan, N.V. Spatial Heterogeneity of Soil Organic Carbon in Tree-Based Intercropping Systems in Quebec and Ontario, Canada. Agrofor. Syst. 2010, 79, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baah-Acheamfour, M.; Carlyle, C.N.; Bork, E.W.; Chang, S.X. Trees Increase Soil Carbon and Its Stability in Three Agroforestry Systems in Central Alberta, Canada. For. Ecol. Manag. 2014, 328, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimaro, O.D.; Desie, E.; Verbist, B.; Kimaro, D.N.; Vancampenhout, K.; Feger, K.H. Soil Organic Carbon Stocks and Fertility in Smallholder Indigenous Agroforestry Systems of the North-Eastern Mountains, Tanzania. Geoderma Reg. 2024, 36, e00759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-H.; Jose, S. Soil Respiration and Microbial Biomass in a Pecan-Cotton Alley Cropping System in Southern USA. Agrofor. Syst. 2003, 58, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sida, T.S.; Baudron, F.; Kim, H.; Giller, K.E. Climate-Smart Agroforestry: Faidherbia Albida Trees Buffer Wheat Against Climatic Extremes in the Central Rift Valley of Ethiopia. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018, 248, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, M.E.; Borden, K.A. Nutrient Acquisition Strategies in Agroforestry Systems. Plant Soil 2019, 444, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, A.S.F.; Leite, L.F.C.; De Freitas Iwata, B.; De Andrade Lira, M.; Xavier, G.R.; Do Vale Barreto Figueiredo, M. Microbiological Process in Agroforestry Systems. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 32, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnankambary, Z.; Ilstedt, U.; Nyberg, G.; Hien, V.; Malmer, A. Nitrogen and Phosphorus Limitation of Soil Microbial Respiration in Two Tropical Agroforestry Parklands in the South-Sudanese Zone of Burkina Faso: The Effects of Tree Canopy and Fertilization. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2008, 40, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, G.A.; Nair, V.D.; Nair, P.K.R. Silvopasture for Reducing Phosphorus Loss from Subtropical Sandy Soils. Plant Soil 2007, 297, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulya, N.A.; Harianja, A.H.; Sayekti, A.L.; Yulianti, A.; Djaenudin, D.; Martin, E.; Hariyadi, H.; Witjaksono, J.; Malau, L.R.E.; Mudhofir, M.R.T.; et al. Coffee Agroforestry as an Alternative to the Implementation of Green Economy Practices in Indonesia: A Systematic Review. AIMS Agric. Food 2023, 8, 762–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udawatta, R.P.; Garrett, H.E.; Kallenbach, R.L. Agroforestry and Grass Buffer Effects on Water Quality in Grazed Pastures. Agrofor. Syst. 2010, 79, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udawatta, R.P.; Krstansky, J.J.; Henderson, G.S.; Garrett, H.E. Agroforestry Practices, Runoff, and Nutrient Loss. J. Environ. Qual. 2002, 32, 1214–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco Sepúlveda, R.; Aguilar Carrillo, A. Soil Erosion and Erosion Thresholds in an Agroforestry System of Coffee (Coffea arabica) and Mixed Shade Trees (Inga Spp and Musa Spp) in Northern Nicaragua. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2015, 210, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamau, S.; Barrios, E.; Karanja, N.K.; Ayuke, F.O.; Lehmann, J. Soil Macrofauna Abundance Under Dominant Tree Species Increases along a Soil Degradation Gradient. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2017, 112, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahad, S.; Chavan, S.B.; Chichaghare, A.R.; Uthappa, A.R.; Kumar, M.; Kakade, V.; Pradhan, A.; Jinger, D.; Rawale, G.; Yadav, D.K.; et al. Agroforestry Systems for Soil Health Improvement and Maintenance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Weigl, D.; Droppelmann, K.; Huwe, B.; Zech, W. Nutrient Cycling in an Agroforestry System with Runoff Irrigation in Northern Kenya. Agrofor. Syst. 1999, 43, 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, J.H.N.; Graves, A.R.; Bunce, R.G.H.; Burgess, P.J.; de Filippi, R.; Keesman, K.J.; van Keulen, H.; Liagre, F.; Mayus, M.; Moreno, G.; et al. Modeling Environmental Benefits of Silvoarable Agroforestry in Europe. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2007, 119, 320–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, Z.L.; Bird, S.B.; Emmett, B.A.; Reynolds, B.; Sinclair, F.L. Can Tree Shelterbelts on Agricultural Land Reduce Flood Risk? Soil Use and Management. Soil Use Manag. 2004, 20, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, P.K.R.; Garrity, D. Agroforestry—The Future of Global Land Use; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; Volume 9, pp. 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.; Cajaiba, R.L.; Bastos, R.; Gonzalez, D.; Petrescu Bakış, A.L.; Ferreira, D.; Leote, P.; Barreto da Silva, W.; Cabral, J.A.; Gonçalves, B.; et al. Why Do Agroforestry Systems Enhance Biodiversity? Evidence From Habitat Amount Hypothesis Predictions. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 9, 630151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvade, S. Agroforestry: Refuge for Biodiversity Conservation. Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Eng 2014, 2, 424–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varah, A.; Jones, H.; Smith, J.; Potts, S.G. Temperate Agroforestry Systems Provide Greater Pollination Service than Monoculture. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 301, 107031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, C.; Martin-Chave, A.; Cortet, J.; Hedde, M.; Capowiez, Y. How Agroforestry Systems Influence Soil Fauna and Their Functions—A Review. Plant Soil 2020, 453, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, K.R.; Potvin, C. Variation in Carbon Storage among Tree Species: Implications for the Management of a Small-Scale Carbon Sink Project. For. Ecol. Manag. 2007, 246, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, R.K. Agroforestry Systems: Sources of Sinks of Greenhouse Gases? Agrofor. Syst. 1995, 31, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.G.; Kirschbaum, M.U.F.; Beedy, T.L. Carbon Sequestration and Net Emissions of CH4 and N2O Under Agroforestry: Synthesizing Available Data and Suggestions for Future Studies. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 226, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, P. Carbon Storage Benefits of Agroforestry Systems. Agrofor. Syst. 1994, 27, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardon, P.; Reubens, B.; Reheul, D.; Mertens, J.; De Frenne, P.; Coussement, T.; Janssens, P.; Verheyen, K. Trees Increase Soil Organic Carbon and Nutrient Availability in Temperate Agroforestry Systems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 247, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavan, S.B.; Dhillon, R.S.; Sirohi, C.; Uthappa, A.R.; Jinger, D.; Jatav, H.S.; Chichaghare, A.R.; Kakade, V.; Paramesh, V.; Kumari, S.; et al. Carbon Sequestration Potential of Commercial Agroforestry Systems in Indo-Gangetic Plains of India: Poplar and Eucalyptus-Based Agroforestry Systems. Forests 2023, 14, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, G.S.; Kandpal, B.; Das, A.; Babu, S.; Mohapatra, K.; Devi, A.G.; Devi, H.L.; Chandra, P.; Singh, R.; Barman, K. Impact of 28 Year Old Agroforestry Systems on Soil Carbon Dynamics in Eastern Himalayas. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 283, 111978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L. Agroforestry Systems: Meta-Analysis of Soil Carbon Stocks, Sequestration Processes, and Future Potentials. Land Degrad. Dev. 2018, 29, 3886–3897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschora, H.; Cherubini, F. Co-Benefits and Trade-Offs of Agroforestry for Climate Change Mitigation and Other Sustainability Goals in West Africa. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 22, e00919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.E.; DuVal, A.; Isaac, M.E.; Hohmann, P. At the Roots of Chocolate: Understanding and Optimizing the Cacao Root-Associated Microbiome for Ecosystem Services. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 42, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Noordwijk, M. Agroforestry as Part of Climate Change Response. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 200, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinael, R.; Chevallier, T.; Cambou, A.; Béral, C.; Barthès, B.G.; Dupraz, C.; Durand, C.; Kouakoua, E.; Chenu, C. Increased Soil Organic Carbon Stocks under Agroforestry: A Survey of Six Different Sites in France. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 236, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.B. Agroforestry Management as an Adaptive Strategy against Potential Microclimate Extremes in Coffee Agriculture. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2007, 144, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, A.F.; Fernandes-Filho, E.I.; Daher, M.; Gomes, L.d.C.; Cardoso, I.M.; Fernandes, R.B.A.; Schaefer, C.E.G.R. Microclimate and Soil and Water Loss in Shaded and Unshaded Agroforestry Coffee Systems. Agrofor. Syst. 2021, 95, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosati, A.; Borek, R.; Canali, S. Agroforestry and Organic Agriculture. Agrofor. Syst. 2021, 95, 805–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodt, S.B.; Fontana, N.M.; Archer, L.F. Feasibility and Sustainability of Agroforestry in Temperate Industrialized Agriculture: Preliminary Insights from California. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2020, 35, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awoke, M.D.; Hafner, J.; Kimaro, A.A.; Lana, M.A.; Löhr, K.; Sieber, S. Development of an Integrated Assessment Framework for Agroforestry Technologies: Assessing Sustainability, Barriers, and Impacts in the Semi-Arid Region of Dodoma, Tanzania. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2023, 21, 2285161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.H.; Lovell, S.T. Agroforestry—The Next Step in Sustainable and Resilient Agriculture. Sustainability 2016, 8, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzekraoui, H.; El Khalki, Y.; Mouaddine, A.; Lhissou, R.; El Youssi, M.; Barakat, A. Characterization and Dynamics of Agroforestry Landscape Using Geospatial Techniques and Field Survey: A Case Study in Central High-Atlas (Morocco). Agrofor. Syst. 2016, 90, 965–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, P.E.; Owooh, B.; Idassi, J. Assessment of the Adoption of Agroforestry Technologies by Limited-Resource Farmers in North Carolina. J. Ext. 2014, 52, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, C.E.; Quinn, J.E.; Halfacre, A.C. Digging Deeper: A Case Study of Farmer Conceptualization of Ecosystem Services in the American South. Environ. Manag. 2015, 56, 802–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García de Jalón, S.; Burgess, P.J.; Graves, A.; Moreno, G.; McAdam, J.; Pottier, E.; Novak, S.; Bondesan, V.; Mosquera-Losada, R.; Crous-Durán, J.; et al. How Is Agroforestry Perceived in Europe? An Assessment of Positive and Negative Aspects by Stakeholders. Agrofor. Syst. 2018, 92, 829–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Xiong, K.; Zhu, D.; Xiao, J. Revelation of Coupled Ecosystem Quality and Landscape Patterns for Agroforestry Ecosystem Services Sustainability Improvement in the Karst Desertification Control. Agriculture 2023, 13, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flinzberger, L.; Zinngrebe, Y.; Plieninger, T. Labelling in Mediterranean Agroforestry Landscapes: A Delphi Study on Relevant Sustainability Indicators. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 1369–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenwerth, K.L.; Hodson, A.K.; Bloom, A.J.; Carter, M.R.; Cattaneo, A.; Chartres, C.J.; Hatfield, J.L.; Henry, K.; Hopmans, J.W.; Horwath, W.R.; et al. Climate-Smart Agriculture Global Research Agenda: Scientific Basis for Action. Agric. Food Secur. 2014, 3, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Morcillo, M.; Burgess, P.; Mirck, J.; Pantera, A.; Plieninger, T. Scanning Agroforestry-Based Solutions for Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation in Europe. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 80, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, S.W.; Bannister, M.E.; Nair, P.K.R. Agroforestry Potential in the Southeastern United States: Perceptions of Landowners and Extension Professionals. Agrofor. Syst. 2003, 59, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Current, D.A.; Brooks, K.N.; Ffolliott, P.F.; Keefe, M. Moving Agroforestry into the Mainstream. Agrofor. Syst. 2009, 75, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, K.K.; Fujiwara, T.; Sato, N.; Hyakumura, K. Evolving and Strengthening the Cooperative Approach for Agroforestry Farmers in Bangladesh: Lessons Learned from the Shimogo Cooperative in Japan. Sustainability 2018, 10, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdivia, C.; Barbieri, C.; Gold, M.A. Between Forestry and Farming: Policy and Environmental Implications of the Barriers to Agroforestry Adoption. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 2012, 60, 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.M.; Bentrup, G.; Kellerman, T.; MacFarland, K.; Straight, R.; Ameyaw, L. Windbreaks in the United States: A Systematic Review of Producer-Reported Benefits, Challenges, Management Activities and Drivers of Adoption. Agric. Syst. 2021, 187, 103032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlagne, C.; Bézard, M.; Drillet, E.; Larade, A.; Diman, J.-L.; Alexandre, G.; Vinglassalon, A.; Nijnik, M. Stakeholders’ Engagement Platform to Identify Sustainable Pathways for the Development of Multi-Functional Agroforestry in Guadeloupe, French West Indies. Agrofor. Syst. 2023, 97, 463–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Theme | Micro Level Barriers (Farm/Household/Individual) | References |

|---|---|---|

| Economic Barriers |

| [48,66,79,87,95,99,124,172,173,174,175] |

| Technical Knowledge and Information Barriers |

| [66,79,92,95,99,172,173,176,177,178,179,180] |

| Social and Cultural Barriers |

| [48,64,73,173,180,181,182,183] |

| Biophysical and Environmental Barriers |

| [41,49,66,79,95,99,113,174,176,184] |

| Theme | Meso Level Barriers (Institutional, Market, Extension) | References |

|---|---|---|

| Institutional Barriers |

| [46,66,92,172,173,174,179,180] |

| Market/Value Chain Barriers |

| [64,92,95,99,124,172,181,185,186] |

| Community/Social Barriers |

| [181,182,183,185,187,188] |

| Theme | Macro Level Barriers (Policy, Tenure, and Structure) | References |

|---|---|---|

| Economic Barriers |

| [47,49,50,51,62,79,172,188] |

| Policy Barriers |

| [89,134,172,173,181,184,189] |

| Environmental Barriers |

| [66,174,175,184,187,188] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bhandari, S.; Paudel, S.; Upadhaya, S. Socio-Economic and Environmental Benefits of Agroforestry and Its Multilevel Barriers to Adoption: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2026, 18, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010005

Bhandari S, Paudel S, Upadhaya S. Socio-Economic and Environmental Benefits of Agroforestry and Its Multilevel Barriers to Adoption: A Systematic Review. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleBhandari, Sudha, Santosh Paudel, and Suraj Upadhaya. 2026. "Socio-Economic and Environmental Benefits of Agroforestry and Its Multilevel Barriers to Adoption: A Systematic Review" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010005

APA StyleBhandari, S., Paudel, S., & Upadhaya, S. (2026). Socio-Economic and Environmental Benefits of Agroforestry and Its Multilevel Barriers to Adoption: A Systematic Review. Sustainability, 18(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010005