Abstract

This work investigated the effects of gamma irradiation on the adsorption capacities of rice husk (RH) for the removal of Cu2+, Cr3+, and Zn2+ ions from aqueous solutions, with potential applications in wastewater remediation. RH samples were gamma-irradiated at doses up to 40 kGy and characterized using SEM-EDS, XRF, FTIR, XRD, and BET analyses. While morphological and textural changes remained subtle, FTIR and SEM-EDS confirmed the formation and intensification of oxygen-containing functional groups, including –OH, –COOH, and C=O, as well as increased exposure of silica (Si–O) on the surfaces, which substantially enhanced surface reactivity of RH toward metal ions. Batch adsorption experiments revealed that 40-kGy irradiated RH samples (RH-40) exhibited the highest removal efficiencies compared to non-irradiated and lower-dose samples (RH-0, RH-10, RH-20, and RH-30), specifically with improvements of 415% for Cu2+, 502% for Cr3+, and 663% for Zn2+ compared to RH-0, determined at the initial concentration of 10 mg/L. Kinetic studies also showed rapid adsorption within the first 10–15 min, dominated initially by boundary-layer diffusion, followed by chemisorption-driven equilibrium behavior. The pseudo-second-order (PSO) model provided an excellent fit for all metals (R2 = 0.999), indicating maximum model-predicted kinetic capacities of 555.56 mg/g (Cu2+), 769.23 mg/g (Cr3+), and 434.78 mg/g (Zn2+). Langmuir isotherms also fitted well (R2 = 0.941–0.995), with predicted monolayer capacities of 535.33 mg/g (Cu2+), 491.64 mg/g (Cr3+), and 318.88 mg/g (Zn2+). Freundlich modeling further indicated favorable heterogeneous adsorption, with KF values of 42.614 (Zn2+), 20.443 (Cr3+), and 16.524 (Cu2+) and heterogeneity factors (n) greater than 1 for all metals. These overall results suggested that gamma irradiation substantially enhanced RH functionality that enabled fast and high-capacity heavy-metal adsorption through surface oxidation and carbon valorization. Gamma-irradiated RH, therefore, represented a promising, low-cost, and environmentally friendly biosorbent for wastewater treatment applications.

1. Introduction

Rice husk (RH) is an abundant agricultural byproduct generated during rice milling, which accounts for approximately 20–30% of the harvested grain mass [1]. RH possesses a unique hierarchical structure consisting of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, with a silica-rich outer layer that provides stiffness, thermal stability, and resistance to microbial degradation [2,3]. Additionally, RH has been widely utilized as a versatile raw material in multiple industries and applications, mainly due to its low density, high ash content (typically 15–20%), and naturally porous morphology. For instance, its silica-rich ash serves as a precursor for producing value-added materials, including precipitated silica, silicon carbide, pozzolanic cement, and lightweight insulation bricks, owing to its high silica content, which can be extracted and transformed into ceramic or construction products [4,5,6,7]. Furthermore, RH is often utilized as a renewable fuel since its high volatile content enables efficient combustion and provides an inexpensive, sustainable source of heat and power [8]. In polymer composites, RH could be used as a reinforcing filler, where its lignocellulosic structure enhances mechanical strength while reducing material consumption and costs [9]. The carbon-rich nature and biodegradability of RH also make it suitable for conversion into biochar, activated carbon, soil amendments, and agricultural mulching materials, which improve soil fertility, water retention, and microbial activity in agriculture [10,11,12].

In addition to the mentioned applications of RH, its utilization as a heavy-metal adsorbent has gained increasing attention as global concerns over wastewater contamination continue to grow. This is due to the industrial effluents from sectors such as electroplating, mining, leather tanning, and metal finishing discharging toxic ions such as Cu2+, Cr3+, and Zn2+, into natural water bodies, where they persist, bioaccumulate, and pose severe risks to ecosystems and human health [13,14]. To alleviate such concerns, RH offers a promising low-cost and sustainable alternative to conventional adsorbents due to its unique physicochemical structures. In particular, its lignocellulosic matrix contains abundant hydroxyl, carboxyl, and methoxy groups that are capable of binding metal ions through complexation, ion exchange, and electrostatic attraction. Additionally, the silica-rich, porous outer layer of rice husk contributes additional surface area and sorption sites that further enhance its ability to adsorb contaminants [15,16]. Examples of work reporting the utilization of RH as a heavy-metal adsorbent include the work of Abdel-Ghani et al., who reported that RH-based sorbents exhibited Pb2+ removal efficiencies of 98.15% at room temperature, suggesting their competitiveness with more expensive synthetic materials [17]. Similarly, Futalan et al. synthesized activated carbon (AC) from RH using lemon-juice activation and obtained Pb2+ removal efficiencies as high as 98.5%, with the adsorption behavior following pseudo-second-order (PSO) kinetics indicative of a chemisorption-dominated mechanism from its oxygen-containing functional groups [18]. Moreover, comprehensive reviews further showed that RH and its derivatives have been successfully applied for the removal of a broad range of metals (Fe2+, Pb2+, Ni2+, Cd2+, Cu2+, Zn2+, and Hg2+) from various industrial wastewaters, including electroplating effluents [15].

Nonetheless, although RH is widely regarded as promising and low-cost biosorbents, its direct use in heavy-metal removal is limited by several constraints. For example, unmodified or merely water-washed RH typically exhibited relatively low adsorption capacities. As shown by Lata and Samadder, the adsorption capacities of unmodified RH were only 0.139–0.147 mg/g for As3+/As5+, 8.58 mg/g for Cd2+, 4.23 mg/g for Pb2+, and 1.42 mg/g for Cd2+ under optimized conditions. Their study further showed that unmodified RH could leach soluble organic matter during drinking-water treatment, resulting in reduced metal uptake and increased chemical and biological oxygen demand (COD and BOD) in the treated effluent, which was incompatible with regulatory water-quality standards [19]. To overcome these drawbacks, several modification strategies have been developed, including alkaline treatment with NaOH or Na2CO3, acid treatment, and grafting with agents such as epichlorohydrin or quaternary ammonium salts, all of which introduce additional functional groups and ion-exchange sites to RH. For instance, NaOH pre-treatment on RH increased Cd2+ removal efficiencies from 53% to 85.4% mg/g [20], while tartaric-acid treatment on RH increased Cu2+ and Pb2+ removal capacities to 29 mg/g and 108 mg/g, respectively [21]. In addition, more intensive approaches that converted RH into AC using chemical activation with H3PO4, ZnCl2, or H2SO4 at elevated temperatures could yield highly porous carbons with greatly enhanced adsorption capacities [22,23]. However, these chemical and thermal modification methods present substantial disadvantages and environmental concerns as they typically require concentrated acids, bases, or metal salts, which are corrosive to equipment and generate large volumes of acidic or saline wastewater that requires subsequent treatment. Furthermore, thermal activation to obtain AC involves high energy consumption, which inevitably increases operational costs and greenhouse gas emissions, thereby complicating potential scale-up and operating against green-chemistry principles, consequently limiting the sustainability of such approaches [24,25].

In addition to the chemical and thermal modification methods previously described, gamma irradiation has emerged as a green and effective approach for modifying surface chemistry in lignocellulosic materials, including RH, to improve their adsorption capacity. This improvement is possible because high-energy photons can cause radiolytic cleavage, chain scission, and oxidation in cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, thereby producing more oxygen-containing functional groups (carboxyl, carbonyl, and hydroxyl) on their surfaces [26]. These newly generated groups subsequently increase the surface polarity and strengthen the interaction between RH and heavy-metal ions by providing more active binding sites and promoting stronger complexation. Nonetheless, while numerous studies have reported the advantages of gamma irradiation in modifying the properties of similar natural materials, its direct application to RH for heavy metal removal has not been thoroughly examined. Some other similar reports utilizing gamma irradiation include the incorporation of gamma-irradiated chitosan into natural rubber foam, which resulted in improved adsorption capacities of Cu2+, Pb2+, Zn2+, and Cd2+ ions relative to non-irradiated samples, when evaluated at the same filler content and testing conditions. This enhancement was primarily due to the increased numbers of amine and hydroxyl groups in chitosan caused by gamma irradiation, which enhanced binding affinity to the concerned heavy metals [27]. Additionally, AC derived from coconut shells as well as their raw powder form both showed higher oil adsorption capacities for diesel, engine oil, and vegetable oil after gamma irradiation, mostly due to surface oxidation and partial pore restructuring in the materials, which made them better bind to metal ions (more oleophilic) [28]. In addition to its ability to improve adsorption capacities, gamma irradiation is considered a reagent-free and tunable modification method (by varying irradiation doses) that reduces the need for corrosive acids or oxidants during chemical treatments, thereby enhancing its capacity for heavy-metal adsorption while adhering to the principles of green chemistry [29].

As aforementioned, this study hypothesized that exposing RH to gamma irradiation would improve its adsorption capacity for Cu2+, Cr3+, and Zn2+ by promoting surface modification and/or structural alterations, thereby enhancing surface polarity and increasing the availability of active binding sites, ultimately facilitating greater metal-ion uptake. To evaluate this potential, RH samples were gamma-irradiated at doses ranging from 0 to 40 kGy in 10-kGy increments, followed by comprehensive physicochemical analyses using SEM-EDS, XRF, BET, FTIR, TGA, and XRD to assess the effects of gamma irradiation. For adsorption behaviors toward individual metal ions, the properties were examined by measuring adsorption capacity and removal efficiency at different initial metal concentrations. The kinetic analyses were also conducted using the pseudo-first-order (PFO), pseudo-second-order (PSO), and intraparticle diffusion (IPD) models to identify the dominant rate-controlling steps, whereas the isotherm analyses were determined using the Langmuir and the Freundlich models. The overall outcomes of this work would clarify whether and how gamma irradiation modifies the surface chemistry and structural characteristics of RH, and assess its feasibility as a clean, reagent-free, and tunable modification method for enhancing heavy-metal remediation. In addition, this work supported the development of sustainable, high-performance sorbents valorized from agricultural wastes for effective environmental treatment applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Chemicals

The RH used in this study was obtained from local farmers in Satun Province, Thailand. Prior to gamma irradiation, RH was dried in a hot-air oven at 105 °C for 24 h to eliminate residual moisture. The dried RH was subsequently passed through a 100-mesh sieve, and its average particle size was determined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Quanta 450, FEI, Tokyo, Japan) and ImageJ (version 1.54p) [30]. The average particle size of the sieved RH was determined to be 118.5 ± 25.1 µm. For gamma irradiation, 100 g of each sample was placed in sealed polyethylene bags and irradiated using a 60Co gamma source (Izotop, Ob-Servo Ignis-09, Budapest, Hungary) with a dose rate of 7.4 kGy/h at the Thailand Institute of Nuclear Technology (Public Organization). The total absorbed doses used in this work were varied from 0 (control) to 40 kGy in 10-kGy increments, of which the upper limit of 40 kGy was chosen as a preliminary setup to show the effects of gamma irradiation on the properties of RH, while avoiding the structural degradation that was often reported at higher doses. Furthermore, the selected dose range ensured a practical balance between irradiation efficiency, processing time, and overall operational cost. The notation of RH-X used throughout the report represented an RH sample that was gamma-irradiated with X kGy. For instance, RH-0 and RH-40 denote non-irradiated RH and 40-kGy irradiated RH samples, respectively.

2.2. Characterization

2.2.1. Determination of Heavy-Metal Adsorption Capacity

The adsorption capacity of RH toward Cu2+, Cr3+, and Zn2+ ions was evaluated using aqueous solutions prepared from Cu(NO3)2·3H2O, Cr(NO3)3·9H2O, and Zn(NO3)2·6H2O, respectively. Stock solutions of each metal ion (1000 mg/L) were prepared in ultrapure water using analytical-grade reagents, and the testing concentrations of 10, 50, and 250 mg/L were obtained through serial dilution. For each experiment, 0.1 g of RH was introduced into 20 mL of the metal solution inside polyethylene centrifuge tubes. The mixtures were agitated using a digital reciprocating shaker (Daihan-Sci RP-20, Daihan Scientific, Wonju, Republic of Korea) at 180 rpm and room temperature for 120 min to ensure equilibrium. After shaking, the suspensions were filtered through Whatman No. 42 filter paper, and the filtrates were collected for analysis [24,31].

The residual concentrations of Cu2+, Cr3+, and Zn2+ ions were then determined using inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS; Agilent 7700, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Prior to measurement, all samples were acidified with 2% (v/v) HNO3 to stabilize the analytes and minimize matrix effects. Calibration curves were constructed using a certified multi-element standard-2A (High Purity Standards, Charleston, SC, USA), with calibration points ranging from 0.1 to 1.0 mg/L at 0.1 mg/L increments, achieving correlation coefficients (R2) above 0.999 for all analytes. It should be noted that since the initial concentrations (up to 250 mg/L) exceeded the calibration range, post-adsorption samples were diluted using 2% HNO3 as needed [24,31]. To ensure reproducibility, each sample was analyzed at least five times, and its corresponding removal efficiency (%Removal) and equilibrium adsorption capacity (qe) were calculated using Equations (1) and (2), respectively:

where C0 is the initial metal concentration (mg/L), Ce is the equilibrium concentration (mg/L), m is the mass of RH (g), and V is the solution volume (L) [31].

2.2.2. Determination of Adsorption Kinetics and Modeling

Kinetic studies were performed using the RH samples that exhibited the highest adsorption capacities for each metal ion. The experimental procedure followed Section 2.2.1, but with contact times adjusted to 1, 3, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 45, 60, 75, 90, and 120 min. The subsequent adsorption capacity at time t, denoted as qt, was calculated using Equation (3):

where Ct is the metal concentration at contact time t. The resulting qt values were then fitted to three common kinetic models: pseudo-first-order (PFO), pseudo-second-order (PSO), and intraparticle diffusion (IPD) [32,33]. It should be noted that the contact times used in this work were selected to comprehensively capture the rapid initial adsorption stage (1–10 min), the transition toward equilibrium (15–45 min), and the final equilibrium region (60–120 min), following established practices in adsorption kinetic studies of lignocellulosic and gamma-modified biosorbents [27].

Pseudo-First-Order (PFO) Model

The PFO model assumes that the adsorption rate is proportional to the number of available sites, often associated with physisorption. Its linear form can be written as shown in Equation (4):

where k1 is the rate constant. A plot of ln(qe − qt) versus t yields a straight line whose slope equals −k1 and a y-intercept equals ln(qe) [32].

Pseudo-Second-Order (PSO) Model

The PSO model reflects chemisorption as the controlling step, as it is applicable to systems dominated by strong adsorbent-adsorbate interactions. The linearized form of PSO can be shown in Equation (5) as follows:

where k2 is the rate constant. A plot of t/qt versus t provides model parameters from the slope (1/qe) and y-intercept (1/k2qe2) [32].

Intraparticle Diffusion (IPD) Model

The IPD model evaluates diffusion of ions within the RH pore structure and is expressed in Equation (6) as follows:

where kid is the intraparticle diffusion constant, and C indicates boundary-layer effects. A linear plot passing through the origin indicates intraparticle diffusion as the sole rate-limiting step, where deviations imply additional mechanisms may occur during the diffusion [33].

It should be noted that linearized kinetic models involving qe on both sides of the equation may lead to artificially high R2. Therefore, model evaluation in this study was based not only on R2 values, but also on the agreement between experimental and predicted adsorption capacities, error analysis, and mechanistic consistency, following recommendations in recent kinetic modeling studies.

2.2.3. Determination of Adsorption Isotherms and Modeling

Similar to the adsorption kinetics, adsorption isotherms were determined using the RH sample with the highest adsorption capacity. Experiments were performed at initial metal concentrations of 10, 50, and 250 mg/L, with 0.1 g of RH and a contact time of 120 min. The equilibrium adsorption capacities (qe) were calculated using Equation (2), and the data were then fitted to the Langmuir and the Freundlich isotherm models [34,35].

Langmuir Model

The Langmuir model, which assumes monolayer adsorption on a uniform surface, was applied using Equation (7):

where qmax denotes the theoretical monolayer capacity, and KL is the binding affinity constant. A plot of Ce/qe versus Ce provides model parameters from the slope (1/qmax) and y-intercept (1/KL·qmax) [34,35].

Freundlich Model

Multilayer adsorption on heterogeneous RH surfaces was evaluated using the Freundlich model, with the linearized form shown in Equation (8) as follows:

where KF and n represent adsorption capacity and heterogeneity factor, respectively [34,35].

2.2.4. Morphology, Elemental Composition, and Porosity

Morphological properties of RH, both non-irradiated and irradiated, were examined using scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) (Quanta 450, FEI, Tokyo, Japan) operated at 15 kV. Elemental compositions, as well as ratios of oxygen to carbon (O/C), were quantified using SEM-EDS and X-ray fluorescence (XRF) (S2 PUMA, Bruker AXS, Madison, WI, USA) [36]. Porosity parameters, including BET surface area, t-Plot pore volume, BJH pore volume, and BJH pore size, were obtained using a surface area and porosity analyzer (3Flex, Micromeritics, Norcross, GA, USA) at 77 K [28].

2.2.5. Functional Groups, Crystallinity, and Thermal Stability

Functional groups of both non-irradiated and irradiated RH samples were identified using Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (Vertex 70, Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) over the wavenumber range of 400–4000 cm−1 to observe irradiation-induced surface chemical changes [37]. Crystalline structure was examined using an X-ray diffractometer (XRD) (D8 Advance, Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA), with Cu Kα radiation, λ = 1.5406 Å, and 2θ = 10–80°. Thermal decomposition behavior was evaluated using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) (TGA/DSC 3+, Mettler-Toledo, Greifensee, Switzerland) from 30–1000 °C at a heating rate of 20 °C/min under nitrogen with a flow rate of 60 mL/min.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 30.0) at a 95% confidence level (p < 0.05). Differences between groups were assessed using Student’s t-test.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Morphological and Pore Characteristics

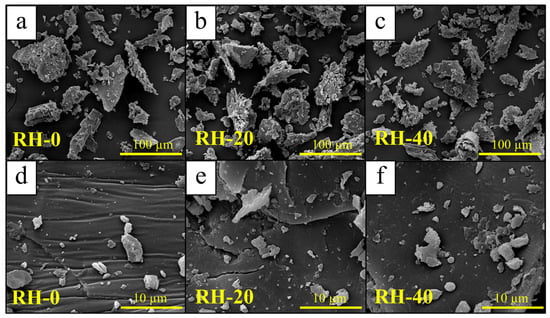

The morphological characteristics of non-irradiated and gamma-irradiated RH samples, evaluated using SEM, are shown in Figure 1. The images illustrate that gamma irradiation generally induced only minor and relatively subtle changes in the surface morphology of RH. In particular, the non-irradiated sample (RH-0) exhibited plate-like fragments with mostly smooth surfaces and limited surface texture. Following gamma irradiation at 20 and 40 kGy, the particle surfaces of RH-20 and RH-40 became relatively smoother. However, these alterations were modest and did not indicate any major structural transformation. Additionally, the average particle sizes of RH-20 (122.1 ± 32.5 µm) and RH-40 (115.0 ± 23.9 µm) were also comparable to RH-0 (118.5 ± 25.1 µm), confirming that gamma irradiation up to 40 kGy did not significantly affect particle dimensions and shapes of RH samples. Therefore, the SEM analysis suggested that gamma irradiation preserved most of the original morphological characteristics of RH, with no substantial changes to bulk structure.

Figure 1.

Micrograph images of (a,d) RH-0, (b,e) RH-20, and (c,f) RH-40.

The minimal effect of gamma irradiation on RH morphology was further supported by the pore-structure data presented in Table 1, as the BET surface areas of RH-0, RH-20, and RH-40 remained substantially low and confined within a narrow range of 1.493–2.106 m2/g. Similarly, the t-plot micropore volumes were essentially negligible for all samples, with the values ranging from −0.0005 to −0.0007 cm3/g, which confirmed the absence of measurable microporosity both before and after gamma irradiation. Although minor variations were observed in the BJH mesopore volumes (decreasing from 0.0090 to 0.0073 cm3/g) and BJH pore size (increasing from 16.48 to 24.81 nm) following gamma irradiation, these changes did not correspond to the development of new pore structures or detectable changes as shown in the SEM images (Figure 1). Instead, they probably reflected minor rearrangements of surface fragments rather than meaningful alterations in the overall porosity of RH. It should be noted that the pore characteristics of RH-0, RH-20, and RH-40 in this work were similar to the report by Gun et al., who showed that the BET surface area, total pore volume, and pore diameter for raw rice husk were 0.6508 m2/g, 0.00172 cm3/g, and 73.02 nm, respectively [38].

Table 1.

Pore characteristics, consisting of BET surface area, t-plot pore volume, BJH pore volume, and BJH pore size, of RH-0, RH-20, and RH-40.

3.2. Functional Groups and Elemental Compositions

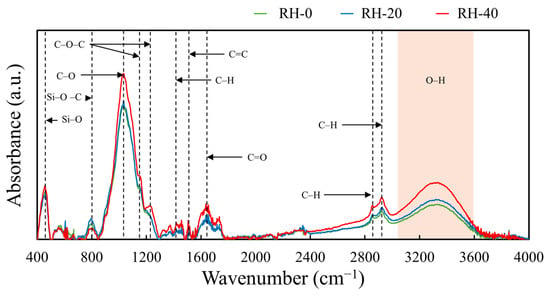

Functional groups of RH samples, identified using FTIR analysis, are shown in Figure 2, which illustrates that RH-0, RH-20, and RH-40 exhibited similar characteristic absorption bands, with prominent peaks observed at 460 cm−1 (Si–O symmetric stretching/bending of amorphous silica), 800 cm−1 (Si–O–C stretching associated with silica-cellulose interactions), 1036 cm−1 (C–O stretching of polysaccharides), 1157 cm−1 (Si–O–Si asymmetric stretching from silica), 1236 cm−1 (C–O–C stretching of cellulose and hemicellulose), 1430 cm−1 (C–H bending vibrations of cellulose and hemicellulose), and 1515 cm−1 (aromatic C=C stretching characteristic of lignin). Additionally, peaks at 2862 and 2932 cm−1 corresponding to aliphatic C–H stretching in cellulose and lignin, as well as a broad band spanning from 3000–3600 cm−1 corresponding to O–H stretching from hydroxyl groups in cellulose and hemicellulose, were also observed. These findings were similar to other studies on the functional groups of RH, which confirmed the typical lignocellulosic and silica-related functionalities present in RH used in this work [39,40,41].

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra of RH-0, RH-20, and RH-40.

Nonetheless, following gamma irradiation, distinct changes in FTIR absorption intensities were observed. Most notably, the Si–O–C band at 800 cm−1 decreased in intensity, indicating that the covalent linkages between silica and the carbohydrate components (cellulose and hemicellulose) were partially cleaved by high-energy photons. Such radiolytic cleavage then disrupted the Si–O–C bonds and generated free silanol (Si–OH) groups along with fragmented carbohydrate chains, resulting in the progressive decoupling of silica from the surrounding biopolymer matrix [42]. On the other hand, the silica network (Si–O) at 460 cm−1 slightly increased following gamma irradiation. This enhancement implied the greater exposure of the underlying silica framework due to the partial valorization or radiolytic degradation of carbonaceous constituents, potentially forming gaseous byproducts such as CO2. The increased exposure of silica also corresponded with the enhanced intensity of the −OH stretching band near 3300 cm−1 due to the increased hydrophilicity and higher abundance of hydroxyl functionalities on the irradiated RH surface [43]. Similar to Si–O, the intensities of C–O and C–O–C bands, corresponding to polysaccharides and ether linkages in cellulose and hemicellulose, along with the aliphatic C–H stretching bands, increased after irradiation. These enhancements suggested that parts of the carbohydrate backbone became exposed as a result of gamma-induced chain scission. Moreover, the increased intensities of C=O and O–H bands implied the occurrence of gamma-induced oxidation on RH samples from the newly generated reactive species such as hydroxyl radicals (•OH), hydrogen radicals (•H), and other oxidizing intermediates that subsequently interacted with glycosidic bonds and aromatic structures in lignin and carbohydrates. These reactions then led to the formation of new carbonyl and hydroxyl groups, ultimately increasing the density of oxygen-containing functionalities on the RH surfaces [44,45].

The occurrence of gamma-induced oxidation and the increase in oxygen-containing functional groups in RH samples were further supported by the elemental compositions obtained from SEM-EDS and XRF analyses (Table 2 and Table 3, respectively). The SEM-EDS results revealed a consistent increase in oxygen content with increasing gamma dose (from 43.2 ± 1.6 wt% in RH-0 to 45.2 ± 1.1 wt% in RH-40), accompanied by a corresponding decrease in carbon content (from 54.1 ± 2.3 wt% in RH-0 to 50.6 ± 1.9 wt% in RH-40). As a result, the O/C ratio increased progressively from 0.80 ± 0.05 in RH-0 to 0.89 ± 0.04 in RH-40, which clearly indicated the enhancement of oxygen-containing surface functionalities after gamma irradiation. This trend was in agreement with the FTIR observations (Figure 2), which showed enhanced intensities of O–H, C–O, C–O–C, and C=O bands that were characteristic products of oxidation-induced chain scission in lignocellulosic materials. Furthermore, the XRF analysis (Table 3) confirmed that the compositions of inorganic and mineral components, particularly Si, K, Ca, S, and P, remained relatively unchanged for all gamma doses, indicating that gamma irradiation selectively modified or affected the organic constituents of RH without majorly altering its mineral compositions. This observed increase in oxygen-containing functional groups after gamma irradiation was consistent with those observed in other irradiated materials, including activated carbons and waste eggshell powder [28,46].

Table 2.

Elemental compositions and oxygen-to-carbon (O/C) ratios of RH-0, RH-20, and RH-40, determined using SEM-EDS.

Table 3.

Compositions of inorganic and mineral components in RH-0, RH-20, and RH-40, determined using XRF.

3.3. Thermal Stability

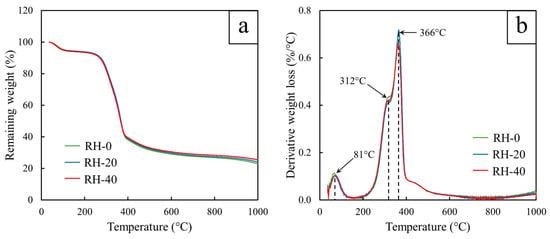

The thermal decomposition behaviors of the RH samples, both before and after gamma irradiation, are shown in Figure 3. The results indicated that RH-0, RH-20, and RH-40 exhibited similar overall decomposition patterns, with an initial mass loss of approximately 5% below 120 °C (Figure 3a), corresponding to the evaporation of physically adsorbed moisture. On the other hand, the major composition events occurred between 250 and 400 °C, which could be attributed to the thermal breakdown of hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin [47]. This behavior was further supported by the derivative weight-loss curves (Figure 3b), which showed two characteristic peaks in this temperature range: a shoulder at 312 °C associated with hemicellulose decomposition and a dominant peak at 366 °C corresponding to cellulose decomposition [48]. Additionally, the positions of these peaks were found to be nearly unchanged for all gamma doses, implying that gamma irradiation did not substantially affect the intrinsic thermal decomposition temperatures of the polysaccharide components. Nonetheless, although the peak temperatures were identical for all samples, slight variations in peak intensity were observed. Specifically, RH-20 and RH-40 exhibited marginally reduced derivative weight-loss intensities compared with RH-0, suggesting a modest reduction in decomposition rate. This behavior was consistent with the gamma-induced oxidation confirmed by FTIR and SEM-EDS analyses, of which the increase in oxygenated species after gamma irradiation would disrupt polymer chain packing and slightly weaken thermal cohesiveness, ultimately lowering the decomposition rate, without noticeably affecting the primary thermal transition temperatures [49].

Figure 3.

TGA results showing (a) remaining weight (%) and (b) derivative weight loss of RH-0, RH-20, and RH-40.

3.4. Crystalline Structure

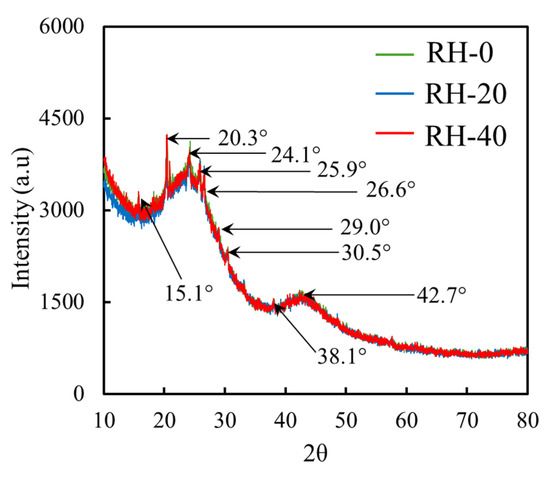

The XRD patterns of RH-0, RH-20, and RH-40 (Figure 4) revealed that all samples exhibited nearly identical diffraction behaviors, implying that gamma irradiation up to 40 kGy did not noticeably alter the crystalline or amorphous structures of RH. All diffractograms displayed a consistent series of broad, low-intensity peaks at 15.1°, 20.3°, 24.1°, 25.9°, 26.6°, 29.0°, 30.5°, 38.1°, and 42.7°, which were typical characteristics of lignocellulosic materials containing amorphous silica and partially ordered cellulose. Furthermore, the broad halo in the 20–26° region, representing the dominant amorphous phase associated with silica and disordered cellulose microfibrils, remained essentially unchanged for all samples, further confirming the structural stability of RH under irradiation [50,51].

Figure 4.

XRD patterns of RH-0, RH-20, and RH-40.

Importantly, no peak shifts or changes in shapes/widths were observed following irradiation, indicating that the irradiation doses employed in this study were insufficient to induce lattice rearrangement, crystallinity loss, or structural degradation within the silica-rich phase or cellulose microdomains. Furthermore, these findings suggested that the crystalline regions of cellulose I and the amorphous silica framework in RH were highly resistant to structural modification under gamma irradiation up to 40 kGy. As a result, while gamma irradiation clearly influenced surface chemistry, as evidenced by FTIR and SEM-EDS analyses, the XRD results confirmed that the bulk structural order and mineral composition of RH remained essentially unaffected.

3.5. Heavy-Metal Adsorption Capacity

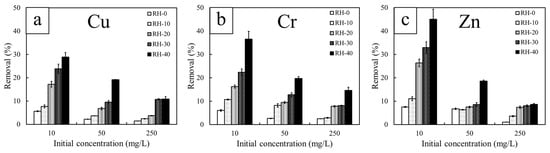

The heavy-metal removal efficiencies (%Removal) of Cu2+, Cr3+, and Zn2+ for non-irradiated and gamma-irradiated RH samples are presented in Figure 5. The overall results indicated that the %Removal progressively increased with increasing gamma doses. Among all conditions, RH-40 consistently exhibited the highest %Removal for all metals and initial concentrations. Specifically, at the initial concentration of 10 mg/L, the %Removal values of RH-40 surpassed those of the RH-0 by 415% for Cu2+, 502% for Cr3+, and 663% for Zn2+, suggesting the substantially enhancing effect of gamma irradiation on adsorption capacities through the gamma-induced chemical modifications within the lignocellulosic matrix of RH. As discussed in Section 3.2, this enhancement was due to the ability of gamma photons to generate radiolytic cleavage and control oxidation within cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, which subsequently introduced additional oxygen-containing functional groups, including hydroxyl (–OH), carbonyl (C=O), and carboxyl (–COOH) moieties, as well as exposing silica networks to its surfaces [52]. These additional functionalities then increased surface polarity, availability of electron-donating sites, and electrostatic attraction or surface complexation with metal ions, thereby enhancing the heavy-metal removal capabilities of the RH samples. Although SEM and BET analyses (Figure 1 and Table 1) indicated minimal increases in surface area and negligible formation of micro- or mesopores, the slight broadening of mesoporous features and loosening of surface fragments may promote faster diffusion pathways and improve accessibility for ion binding [53].

Figure 5.

Heavy metal removal efficiency (%Removal) of non-irradiated and gamma-irradiated RH, determined at different initial concentrations of 10, 50, and 250 mg/L. The heavy metals investigated include (a) copper (Cu), (b) chromium (Cr), and (c) zinc (Zn).

Another notable observation from Figure 5 is the consistent decrease in %Removal with increasing initial concentrations, regardless of gamma doses and metal types. This behavior was observed because the ratio of metal ions to available functional groups on the RH surfaces was relatively small at low concentrations, which allowed most ions to be effectively captured and ultimately removed. However, as the initial concentrations increased, the number of ions in solution exceeded the limited binding sites, leading to progressive site saturation [54]. Given that all RH samples exhibited inherently low surface area and negligible microporosity (Table 1), their capacity to accommodate additional ions became rapidly constrained once these sites were occupied. Although gamma irradiation could introduce additional surface functionalities and enhance metal–ligand interactions in RH, these improvements remained insufficient to compensate for the excessive abundance of ions, thereby resulting in the decline of %Removal at higher concentrations.

Additionally, the results indicated that Zn2+ exhibited higher adsorption capacity than those of Cu2+ and Cr3+ at low initial concentrations, mainly due to its more favorable desolvation characteristics. In particular, Zn2+ had a moderate hydration energy (−2058 kJ/mol) [55], which was substantially lower in magnitude than that of Cu2+ (−2121 kJ/mol) [55] and Cr3+ (−4563 kJ/mol) [56]. The weaker hydration shell of Zn2+ then allowed it to desolvate more easily and better interact with surface oxygen-containing functional groups, consequently promoting effective complexation at low metal concentrations. Cu2+, in contrast, had a slightly more exothermic hydration energy and underwent Jahn–Teller distortion, resulting in an anisotropic and more strongly bound solvation shell that restricted its initial availability for adsorption [57]. Lastly, Cr3+ exhibited the strongest hydration energy among the three metals by forming very stable hexahydrated complexes such as [Cr(H2O)6]3+, which reduced its early-stage adsorption onto the RH surface [58]. However, as the initial concentration increased, Cr3+ began to show the highest removal efficiency among the three metals. This change in the removal behavior was attributed to its much higher charge density (3+) in Cr3+, which increased electrostatic attraction toward negatively charged carboxyl, hydroxyl, and carbonyl groups generated or enhanced after gamma irradiation. In other words, the strong Coulombic force overcame the hydration barrier at these high concentrations, allowing Cr3+ to outcompete Zn2+ and Cu2+ for available binding sites [59]. It is noteworthy that RH-40 consistently demonstrated superior adsorption performance for all tested metals, and was selected as the representative sample for detailed kinetic and isotherm analyses.

3.6. Adsorption Kinetics and Modeling

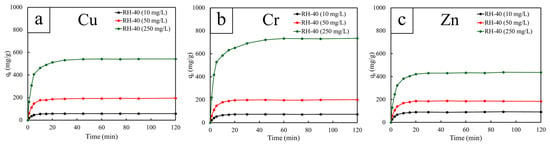

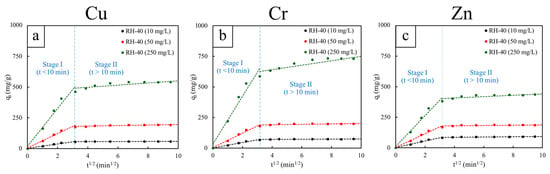

The kinetic adsorption profiles of Cu2+, Cr3+, and Zn2+ onto RH-40 at different initial concentrations (10, 50, and 250 mg/L) are shown in Figure 6. For all three metals, the adsorption process was characterized by a very rapid uptake during the first few minutes, followed by a gradual approach to equilibrium. This fast initial adsorption was attributed to the abundance of accessible surface functional groups, which provided high-affinity binding sites that facilitated metal–ligand interactions. Regardless of metal type or initial concentration, approximately 70–85% of total adsorption occurred within the first 5–10 min, suggesting that the RH surface was dominated by external-site binding rather than by deeper intraparticle diffusion. After approximately 10 min, the adsorption capacities for all conditions began to plateau, implying that most active sites had been occupied and that the system had effectively approached saturation. Furthermore, the effect of initial concentration was also evident from the kinetic trends. For instance, at low concentrations (10 mg/L), the adsorption capacity increased rapidly but reached relatively low equilibrium values (less than 100 mg/g) due to the limited availability of metal ions relative to the excess of binding sites. On the other hand, at the highest concentrations (50 and 250 mg/L), the initial adsorption rates were slightly steeper, with higher adsorption capacities at equilibrium (180–200 mg/g and 400–700 mg/g, respectively), suggesting a greater driving force from a larger concentration gradient. However, saturation was reached within approximately 10–20 min, indicating that the active sites were rapidly filled, in a manner similar to that at low concentrations.

Figure 6.

Heavy metal adsorption capacities (qt) as a function of contact time (t = 1–120 min) for RH-40, determined at different initial concentrations of 10, 50, and 250 mg/L. The heavy metals investigated include (a) copper (Cu), (b) chromium (Cr), and (c) zinc (Zn).

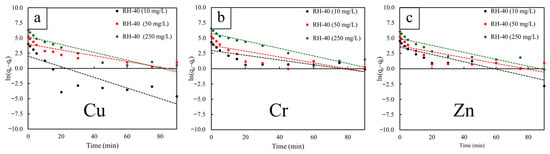

The adsorption kinetics of Cu2+, Cr3+, and Zn2+ onto RH-40 were analyzed using the pseudo-first-order (PFO), pseudo-second-order (PSO), and intraparticle diffusion (IPD) models at initial concentrations of 10, 50, and 250 mg/L (Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9). The PFO model exhibited relatively poor fitting performance, with R2 values ranging only from 0.616 to 0.881 (Table 4). Although the calculated equilibrium capacities (qe) increased with initial concentration, the PFO-estimated qe values were consistently lower than those obtained experimentally. These observations suggested that the physisorption mechanism based on the PFO model could not adequately describe the adsorption behavior of RH-40 [60]. On the other hand, the PSO model provided an excellent fit for all metals and concentrations, with R2 consistently equal to 0.999 (Table 5). The PSO-estimated qe values also closely matched the experimental values, for example, from 58.48 to 555.56 mg/g for Cu2+, from 74.63 to 769.23 mg/g for Cr3+, and from 93.46 to 434.78 mg/g for Zn2+. As a result, the PSO model provided the best empirical description of the adsorption kinetics for RH-40, indicating that the adsorption process was strongly associated with surface interactions involving gamma-induced functional groups [61].

Figure 7.

Pseudo-first-order (PFO) kinetic model fittings for RH-40, determined at different initial concentrations of 10, 50, and 250 mg/L. The heavy metals investigated include (a) copper (Cu), (b) chromium (Cr), and (c) zinc (Zn). The dash lines represent the linear fitting of the data.

Figure 8.

Pseudo-second-order (PFO) kinetic model fittings for RH-40, determined at different initial concentrations of 10, 50, and 250 mg/L. The heavy metals investigated include (a) copper (Cu), (b) chromium (Cr), and (c) zinc (Zn). The dash lines represent the linear fitting of the data.

Figure 9.

Intraparticle diffusion (IPD) kinetic model fittings for RH-40, determined at different initial concentrations of 10, 50, and 250 mg/L. The adsorption process was interpreted in two stages: Stage I (t < 10 min) and Stage II (t > 10 min). The heavy metals investigated include (a) copper (Cu), (b) chromium (Cr), and (c) zinc (Zn). The dash lines represent the linear fitting of the data.

Table 4.

Kinetic parameters of Cu2+, Cr3+, and Zn3+ adsorption for RH-40, obtained from the pseudo-first-order (PFO) model. The parameters include the slope, y-intercept, rate constant (k1), equilibrium adsorption capacity (qe), and correlation coefficient (R2) at different initial concentrations of 10, 50, and 250 mg/L.

Table 5.

Kinetic parameters of Cu2+, Cr3+, and Zn3+ adsorption for RH-40, obtained from the pseudo-second-order (PSO) model. The parameters include the slope, y-intercept, rate constant (k2), equilibrium adsorption capacity (qe), and correlation coefficient (R2) at different initial concentrations of 10, 50, and 250 mg/L.

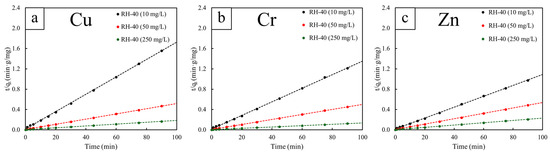

The IPD model further clarified the adsorption mechanism by illustrating two distinct kinetic regions for all metals and concentrations (Figure 9 and Table 6 and Table 7). In Stage I (t < 10 min), the plots exhibited strong linearity (R2 = 0.953–0.984) along with notably high intraparticle diffusion rate constants (kid), both of which increased substantially with initial concentrations. These findings indicated a rapid adsorption phase dominated by boundary-layer diffusion and immediate complexation between metal ions and abundant, high-affinity functional groups present in RH-40. The steep slopes further suggested that approximately 70–85% of total adsorption occurred within the first few minutes, with effective saturation reached at about 10–15 min for all systems. On the other hand, Stage II (t > 10 min) exhibited much lower R2 values (0.342–0.789), indicating deviations from ideal intraparticle diffusion behavior. However, the relatively small RMSE/qe values (1.45–3.02%) suggested that these deviations were minor and primarily resulted from the system approaching equilibrium (the deviations in qt with respect to t1/2 being notably small) rather than from significant diffusion limitations. Based on this observation, it could be concluded that Stage II corresponded to the slow, final occupation of remaining low-energy sites [62,63].

Table 6.

Kinetic parameters of Cu2+, Cr3+, and Zn3+ adsorption for RH-40, obtained from the intraparticle diffusion (IPD) model at Stage I (t < 10 min). The parameters include the slope, y-intercept, rate constant (kid), boundary layer thickness (C), and correlation coefficient (R2) at different initial concentrations of 10, 50, and 250 mg/L.

Table 7.

Kinetic parameters of Cu2+, Cr3+, and Zn3+ adsorption for RH-40, obtained from the intraparticle diffusion (IPD) model at Stage II (t > 10 min). The parameters include the slope, y-intercept, rate constant (k1), boundary layer thickness (C), correlation coefficient (R2), root mean square error (RMSE), and normalized root mean square error (RMSE/qe) at different initial concentrations of 10, 50, and 250 mg/L.

As described above, the combined outcomes from all three kinetic models indicated that the kinetic adsorption of Cu2+, Cr3+, and Zn2+ onto RH-40 was controlled predominantly by rapid surface chemisorption, with boundary-layer diffusion governing the initial uptake stage. The strong agreement with the PSO model, together with the high kid values observed in Stage I and the rapid saturation within 10–15 min, was consistent with the presence of highly reactive oxygen-containing functional groups in RH-40, which enabled fast and efficient heavy-metal adsorption.

3.7. Adsorption Isotherms and Modeling

The isotherm adsorption behavior of Cu2+, Cr3+, and Zn2+ onto RH-40 was evaluated using the Langmuir and the Freundlich isotherm models, and the corresponding parameters are summarized in Table 8 and Table 9. For the Langmuir model, the plots produced high correlation coefficients for all three metals (R2 = 0.941–0.995), indicating that monolayer adsorption on a relatively homogeneous surface is a dominant feature of the system. The maximum adsorption capacities (qmax) obtained from the Langmuir plots followed the order of Cu2+ (535.33 mg/g) > Cr3+ (491.64 mg/g) > Zn2+ (318.88 mg/g), implying the different affinities of these ions toward the oxygen-containing functional groups in RH-40. Among the Langmuir constants (KL), Zn2+ exhibited the highest value (0.0705), which implied the strongest initial binding affinity at low concentrations, consistent with its more favorable hydration and desolvation characteristics. Meanwhile, Cu2+ and Cr3+ showed moderate KL values (0.0169–0.0272), suggesting that although their overall capacities were high, their adsorption strengths at low concentrations were comparatively weaker than that of Zn2+ [64].

Table 8.

Langmuir isotherm parameters for RH-40, consisting of slope, y-intercept, maximum adsorption efficiency (qmax), Langmuir constant (KL), and correlation coefficient (R2).

Table 9.

Freundlich isotherm parameters for RH-40, consisting of slope, y-intercept, heterogeneity factor (n), Freundlich constant (KF), and correlation coefficient (R2).

On the other hand, the Freundlich model provided an excellent fit to the experimental data, providing significantly higher correlation coefficients (R2 = 0.988–0.999) compared with the Langmuir model. This strong agreement indicated that heterogeneous, multilayer adsorption processes may occur alongside monolayer interactions. Furthermore, the Freundlich constant (KF) followed the order Zn2+ (42.614) > Cr3+ (20.443) > Cu2+ (16.524), which suggested that Zn2+ exhibited the strongest affinity for heterogeneous adsorption sites, possibly due to its more favorable desolvation behavior and better compatibility with the oxygen-containing functional groups formed on the RH-40 surfaces [65]. It is important to note that the Freundlich model primarily reflects adsorption behavior at lower concentrations, where ions interact with a broad range of surface sites exhibiting varying binding energies. In this regime, Zn2+, with its moderate hydration energy and comparatively weaker solvation shell, could desolvate more readily and occupy even lower-energy or less uniform sites, resulting in a higher KF value. By contrast, although Cr3+ exhibited the highest Langmuir adsorption capacity (qmax), this behavior emerged predominantly at higher concentrations where monolayer saturation and strong electrostatic interactions governed the metal uptake mechanism. Additionally, heterogeneity factors (n) for all metals exceeded 1 (n = 1.531–2.389), indicating favorable adsorption and confirming that gamma irradiation generated a broad distribution of active binding sites on the RH surfaces [66]. Based on the collective isotherm results, both models adequately described the adsorption behavior of the RH-40 system, although each model represented different aspects of the modified surface. The strong Langmuir fitting suggested that monolayer adsorption dominated on uniformly functionalized regions induced by gamma irradiation, whereas the excellent Freundlich fitting suggested the persistence of surface heterogeneity and the coexistence of multiple types of binding environments.

3.8. Comparative Heavy-Metal Removal Capacities of Gamma-Irradiated RH and Other Biosorbents

Comparisons of heavy-metal removal capacities of RH-0 with RH-40 and other similar biosorbents for Cu, Cr, and Zn are shown in Table 10, which indicates that the adsorption capacities of RH-0 were found to be comparable to those of many commonly reported biosorbents, suggesting that raw RH inherently possesses a reasonable affinity for heavy-metal ions. Specifically, RH-0 exhibited adsorption capacities of 71.1 ± 2.3 mg/g for Cu2+, 124.9 ± 6.3 mg/g for Cr3+, and 52.9 ± 2.9 mg/g for Zn2+, which were within the same range as tamarind (T. indica) seed powder, banana peel biochar, durian shell, tobacco dust, and brown algae reported in previous studies.

Table 10.

Comparative heavy-metal removal capacities of gamma-irradiated RH and other similar biosorbents.

Despite the acceptable removal capacity of RH-0, gamma irradiation substantially modified RH from a conventional biosorbent into a high-performance adsorbent, as evidenced by the substantially higher capacities observed for RH-40. After irradiation, the adsorption capacities of RH-40 increased to 541.5 ± 28.8 mg/g for Cu2+, 732.4 ± 49.2 mg/g for Cr3+, and 431.1 ± 29.4 mg/g for Zn2+, exhibiting several fold enhancements relative to RH-0 and far exceeding those of other biosorbents listed in Table 10. Such improvements clearly showed the effectiveness of gamma irradiation as a non-chemical surface-modification strategy capable of inducing substantial gains in adsorption performance without altering the bulk structure of RH.

It should be noted that, while the present study focused on improving the adsorption performance of RH via gamma-induced surface modification, the post-treatment management of metal-saturated (spent) sorbents, including safe disposal, regeneration, and reuse, has been actively discussed in the adsorption and waste-management reports. For instance, some practical methods to minimize secondary pollution and improve circularity include the following:

- (i)

- Chemical regeneration/desorption (commonly using acids, bases, or chelating agents) to restore adsorption sites and enable multiple adsorption–desorption cycles [75,76];

- (ii)

- Metal recovery from the desorption liquor (precipitation/electrowinning), which was often presented as a complementary step to regeneration to complete the resource recovery procedure [76];

- (iii)

- Repurposing/upcycling of metal-loaded sorbents, where the spent adsorbent was used directly in value-added applications (catalytic or electrochemical materials) to avoid desorption streams and reduce disposal burden [77];

- (iv)

- Stabilization/solidification or immobilization, such as encapsulation in cementitious or geopolymer matrices, to reduce metal leachability and facilitate safer handling and disposal [78].

However, when reuse/regeneration was not feasible, or leaching risk remained unacceptable, regulated disposal (often following leachability assessment and/or prior immobilization) was the appropriate end-of-life route for spent metal-bearing sorbents [79].

4. Conclusions

This work successfully demonstrated that gamma irradiation noticeably enhanced the adsorption performance of rice husk (RH) for the removal of Cu2+, Cr3+, and Zn2+ ions, despite inducing only subtle changes in morphology, crystallinity, and porosity. The improvement was attributed primarily to gamma-induced oxidation, which increased the abundance of oxygen-containing functional groups, such as hydroxyl, carbonyl, and carboxyl groups. This effect increased the exposure of silica networks, which were responsible for strong metal–ligand interactions and improved the hydrophilicity of RH. This chemical functionalization resulted in substantial improvements in adsorption behavior, as evidenced by large increases in removal efficiencies for all metals and the rapid attainment of near-saturation within the first 10–15 min of contact. Kinetic analyses showed that the adsorption profiles were well described by the pseudo-second-order (PSO) model, with rapid uptake occurring at short contact times, consistent with strong surface interactions induced by gamma irradiation. The intraparticle diffusion (IPD) model also indicated a two-stage process: an initial, fast uptake dominated by boundary-layer diffusion, followed by a slower approach to equilibrium as surface sites became saturated. Isotherm analyses further supported these findings, with both Langmuir and Freundlich models fitting the data well, suggesting the coexistence of monolayer adsorption on more uniform high-affinity sites and multilayer adsorption on heterogeneous sites. Based on the overall findings, these results indicated that gamma irradiation exhibited great potential to be used as a clean, tunable, and effective modification method to improve the reactivity and adsorption capacity of agricultural waste-derived adsorbents, especially RH, without the need for chemical activators or complex processing steps. To improve or expand knowledge of waste valorization in wastewater treatment, future research should investigate regeneration and reuse efficiency, assess performance in real wastewater systems, and explore synergistic modification approaches to further enhance adsorption capabilities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.T., T.T. and K.S. (Kiadtisak Saenboonruang); methodology, K.S. (Kulthida Saemood), S.S., S.T.-I. and K.S. (Kiadtisak Saenboonruang); validation, K.S. (Kulthida Saemood), S.S., K.H., P.L., H.M., S.T.-I., S.T., T.T. and K.S. (Kiadtisak Saenboonruang); formal analysis, K.S. (Kulthida Saemood), S.S., K.H., P.L., H.M., S.T.-I., S.T., R.T., T.T. and K.S. (Kiadtisak Saenboonruang); investigation, K.S. (Kulthida Saemood), S.S., K.H., P.L., H.M., S.T.-I., S.T., R.T., T.T. and K.S. (Kiadtisak Saenboonruang); writing—original draft preparation, K.S. (Kiadtisak Saenboonruang); writing—review and editing, K.S. (Kulthida Saemood), S.S., K.H., P.L., H.M., S.T.-I., S.T., R.T., T.T. and K.S. (Kiadtisak Saenboonruang); visualization, K.S. (Kiadtisak Saenboonruang); supervision, K.S. (Kiadtisak Saenboonruang); funding acquisition, K.S. (Kiadtisak Saenboonruang). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Kasetsart University Research and Development Institute (KURDI), Bangkok, Thailand, grant number FF(KU)59.69; the Ministry of Higher Education, Science, Research and Innovation; the Thailand Science Research and Innovation through the Kasetsart University Reinventing University Program 2025; and the Thailand Institute of Nuclear Technology (Public Organization), Nakhon Nayok, Thailand.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Technical support was provided by the Department of Applied Radiation and Isotopes, Kasetsart University (KU), and the Office of Atoms for Peace (OAP). The Kasetsart University Research and Development Institute (KURDI) and the Specialized Center of Rubber and Polymer Materials in Agriculture and Industry (RPM), Faculty of Science, Kasetsart University, provided publication support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of this study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of this manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Korotkova, T.G.; Ksandopulo, S.J.; Donenko, A.P.; Bushumov, S.A.; Danilchenko, A.S. Physical Properties and Chemical Composition of the Rice Husk and Dust. Orient. J. Chem. 2016, 32, 3213–3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.T.; Tran, N.T.; Phan, T.P.; Nguyen, A.T.; Nguyen, M.X.T.; Nguyen, N.N.; Ko, Y.H.; Nguyen, D.H.; Van, T.T.T.; Hoang, D.Q. The Extraction of Lignocelluloses and Silica from Rice Husk using a Single Biorefinery Process and their Characteristics. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2022, 108, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, W.; Martin, J.C.; Oliphant, A.J.; Doerr, P.A.; Xu, J.F.; DeBorn, K.M.; Chen, C.; Sun, L. Extraction of Lignocellulose and Synthesis of Porous Silica Nanoparticles from Rice Husks: A Comprehensive Utilization of Rice Husk Biomass. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2013, 1, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azat, S.; Korobeinyk, A.V.; Moustakas, K.; Inglezakis, V.J. Sustainable Production of Pure Silica from Rice Husk Waste in Kazakhstan. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 217, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Kong, Q.; Liu, Z.; Bi, Z.; Jia, H.; Song, G.; Xie, L.; Zhang, S.; Chen, C.M. High Yield Silicon Carbide Whiskers from Rice Husk Ash and Graphene: Growth Method and Thermodynamics. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 19027–19033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, E.; Ince, C.; Borgianni, Y.; Derogar, S.; Forster, A.M.; Ball, R.J. Enhancing Concrete Durability and Resource Efficiency Through Rice Husk Ash Incorporation: A Data-Driven Approach. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, V.; Panda, S.K.; Singh, V.K. Preparation and Characterization of High-Strength Insulating Porous Bricks by Reusing Coal Mine Overburden Waste, Red Mud and Rice Husk. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 469, 143134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongsiriwattaya, M.; Chompookham, T.; Bupphachot, B. Improvement of Higher Heating Value and Hygroscopicity Reduction of Torrefied Rice Husk by Torrefaction and Circulating Gas in the System. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhot, M.A.; Hassan, M.Z.; Aziz, S.A.; Daud, M.Y.M. Recent Progress of Rice Husk Reinforced Polymer Composites: A Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, Y.; Moriizumi, M.; Shimotsuma, M. Effects of Rice Husk Biochar and Soil Moisture on the Accumulation of Organic and Inorganic Nitrogen and Nitrous Oxide Emissions During the Decomposition of Hairy Vetch (Vicia villosa) Mulch. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2019, 65, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhizkar, M.; Shabanpour, M.; Lucas-Borja, M.S.; Zema, D.A. Effects of Rice Husk Biochar on Rill Detachment Capacity in Deforested Hillslopes. Ecol. Eng. 2023, 191, 106964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezenne, G.I.; Obalum, S.E.; Tanner, J. Physical-Hydraulic Properties of Tropical Sandy-Loam Soil in Response to Rice-Husk Dust and Cattle Dung Amendments and Surface Mulching. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2019, 64, 1746–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wang, Z. Contamination and Health Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in Soil Surrounding an Electroplating Factory in JiaXing, China. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yunus, Z.M.; Al-Gheethi, A.; Othman, N.; Hamdan, R.; Ruslan, N.N. Removal of Heavy Metals from Mining Effluents in Tile and Electroplating Industries using Honeydew Peel Activated Carbon: A Microstructure and Techno-Economic Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 251, 119738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoro, H.K.; Alao, S.M.; Pandey, S.; Jimoh, I.; Basheeru, K.A.; Caliphs, Z.; Ngila, J.C. Recent Potential Application of Rice Husk as an Eco-Friendly Adsorbent for Removal of Heavy Metals. Appl. Water Sci. 2022, 12, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Zhang, Y.; Ge, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Qiu, G. Removal of Heavy Metals from Wastewaters with Biochar Pyrolyzed from MgAl-Layered Double Hydroxide-Coated Rice Husk: Mechanism and Application. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 347, 126425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Ghani, N.T.; Elchaghaby, G.A. Influence of Operating Conditions on the Removal of Cu, Zn, Cd and Pb Ions from Wastewater by Adsorption. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 4, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futalan, C.C.; Diana, E.; Edang, M.F.A.; Padilla, J.M.; Cenia, M.C.; Alfeche, D.M. Adsorption of Lead from Aqueous Solution Using Activated Carbon Derived from Rice Husk Modified with Lemon Juice. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lata, S.; Samadder, S.R. Removal of Heavy Metals using Rice Husk: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Dev. 2014, 4, 165–170. [Google Scholar]

- Montalvo-Andia, J.; Reategui-Romero, W.; Pena-Contreras, A.D.; Alvarez, W.F.Z.; King-Santos, M.E.; Fernandez-Guzman, V.; Guerrero-Guevara, J.L.; Puris-Naupay, J.E. Adsorption of Cd (II) Using Chemically Modified Rice Husk: Characterization, Equilibrium, and Kinetic Studies. Adsorpt. Sci. Technol. 2022, 2022, 3688155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.K.; Lee, C.K.; Low, K.S.; Haron, M.J. Removal of Cu and Pb by Tartaric Acid Modified Rice Husk from Aqueous Solutions. Chemosphere 2003, 50, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, M.M.; Hossain, M.A.; Hossain, M.D.; Johir, M.A.H.; Hossen, J.; Rahman, M.S.; Zhou, J.L.; Hasan, A.T.M.K.; Karmakar, A.K.; Ahmed, M.B. The Potentiality of Rice Husk-Derived Activated Carbon: From Synthesis to Application. Process 2020, 8, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwadibia, P.C.; Eze, J.C.; Anyaogu, D.I.; Abugu, H.O.; Ejikeme, P.M. Adsorptive Capacity of Activated Carbon Derived from Rice Husks for Azo Dye Removal from Solution. Discov. Chem. 2025, 2, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wazir, A.H.; Ullah, I.; Yagoob, K. Chemically Activated Carbon Synthesized from Rice Husk for Adsorption of Methylene Blue in Polluted Water. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2023, 40, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharaka, D.N.; Tissera, N.D.; Priyadarshana, G.; Dahanayake, D. A Comprehensive Review of Hierarchical Porous Carbon Synthesis from Rice Husk. Rice Sci. 2025, 32, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- List, R.; Gonalez-Lopez, L.; Ashfaq, A.; Zaouak, A.; Driscoll, M.; Al-Sheikhly, M. On the Mechanism of the Ionizing Radiation-Induced Degradation and Recycling of Cellulose. Polymers 2023, 15, 4483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intha, T.; Wimolmala, E.; Lertsarawut, P.; Saenboonruang, K. Effects of Gamma-Synthesized Chitosan on Morphological, Thermal, Mechanical, and Heavy-Metal Removal Properties in Natural Rubber Foam as Sustainable and Eco-Friendly Heavy Metal Sorbents. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janlod, C.; Watcharothai, M.; Lertsarawut, P.; Saenboonruang, K. Enhancing Oil Adsorption Capacity via Gamma Irradiation: A Green Approach for Coconut Shell Powder and Coconut Shell-Derived Activated Carbon. Res. Eng. 2025, 28, 107953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnawet, M.; Wimolmala, E.; Lertsarawut, P.; Saenboonruang, K. Surface-Coating of Gamma-Assisted Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO) on Natural Rubber Foam (NRF) for Enhanced Oil Adsorption Performance. React. Func. Polym. 2025, 217, 106490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 Years of Image Analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, H. Heavy Metal Removal from Water by Magnetite Nanorods. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 219, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revellame, E.D.; Fortela, D.L.; Sharp, W.; Hernandez, R.; Zappi, M.E. Adsorption Kinetic Modeling Using Pseudo-First Order and Pseudo-Second Order Rate Laws: A Review. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2020, 1, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadepalli, S.; Murthy, K.S.R.; Sahu, O. Interparticle Diffusion and Thermodynamic Modeling Studies for the Removal of Heavy Metals Using Mixed Adsorbents in Industrial Effluents. Environ. Qual. Manag. 2023, 32, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayyun, T.S.; Mseer, A.H. Comparison of the Experimental Results with the Langmuir and Freundlich Models for Copper Removal on Limestone Adsorbent. Appl. Water Sci. 2019, 9, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, C.S.T.; Almeida, I.L.S.; Rezende, H.C.; Marcionilio, S.M.L.O.; Leon, J.J.L.; Matos, T.N. Elucidation of Mechanism Involved in Adsorption of Pb(II) onto Lobeira Fruit (Solanum lycocarpum) Using Langmuir, Freundlich and Temkin Isotherms. Microchem. J. 2018, 137, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moonlek, B.; Wimolmala, E.; Markpin, T.; Sombatsompop, N.; Saenboonruang, K. Enhancing Electromagnetic Interference Shielding Effectiveness for Radiation Vulcanized Natural Rubber Latex Composites Containing Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes and Silk Textile. Polym. Compos. 2020, 41, 3996–4009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thumwong, A.; Chinnawet, M.; Intarasena, P.; Rattanapongs, C.; Tokonami, S.; Ishikawa, T.; Saenboonruang, K. A Comparative Study on X-ray Shielding and Mechanical Properties of Natural Rubber Latex Nanocomposites Containing Bi2O3 or BaSO4: Experimental and Numerical Determination. Polymers 2022, 14, 3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gun, M.; Arslan, H.; Saleh, M.; Yalvac, M.; Dizge, N. Optimization of Silica Extraction from Rice Husk Using Response Surface Methodology and Adsorption of Safranin Dye. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2022, 16, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, P.J.; Kumar, R.; Pakshirajan, K. Batch and Continuous Removal of Copper and Lead from Aqueous Solution using Cheaply Available Agricultural Waste Materials. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2015, 9, 635–648. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, A.A.H.; Harun, N.Y.; Nasef, M.M. Physicochemical Characterization of Different Agricultural Residues in Malaysia for Bio Char Production. Int. J. Civil Eng. Technol. 2019, 10, 213–225. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R.S.; Salleh, M.N.; Ab Ghani, M.H.; Ahmad, S.; Gan, S. Biocomposites Based on Rice Husk Flour and Recycled Polymer Blend: Effects of Interfacial Modification and High Fibre Loading. BioResources 2015, 10, 6872–6885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltac, A.S.; Mitran, R.-A. Gamma Radiation in the Synthesis of Inorganic Silica-Based Nanomaterials: A Review. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzereogu, P.U.; Omah, A.D.; Ezema, F.I.; Iwuoha, E.I.; Nwanya, A.C. Silica Extraction from Rice Husk: Comprehensive Review and Applications. Hybrid Adv. 2023, 4, 100111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciado, P.; Fraschini, C.; Jamshidian, M.; Salmieri, S.; Safrany, A.; Lacroix, M. Gamma-Irradiation of Cellulose Nanocrystals (CNCs): Investigation of Physicochemical and Antioxidant Properties. Cellulose 2017, 24, 2111–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kumar, G.A. Modification of Lignin Properties using Alpha Particles and Gamma-Rays for Diverse Applications. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2023, 202, 110562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khumsap, S.; Parapichai, N.; Lertsarawut, P.; Saenboonruang, K. Exploring the Potential Utilization of Gamma-Irradiated Waste Eggshell Powder as Oil Sorbents in Natural Rubber Foams. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2025, 226, 112287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, S. Thermal Decomposition, Kinetics and Combustion Parameters Determination for Two Different Sizes of Rice Husk using TGA. Eng. Agric. Environ. Food 2019, 12, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varol, E.A.; Mutlu, U. TGA-FTIR Analysis of Biomass Samples Based on the Thermal Decomposition Behavior of Hemicellulose, Cellulose, and Lignin. Energies 2023, 16, 3674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Lang, X.; Ren, X.; Fan, S. Comparative Evaluation of Thermal Oxidative Decomposition for Oil-Plant Residues via Thermogravimetric Analysis: Thermal Conversion Characteristics, Kinetics, and Thermodynamics. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 243, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubushkin, R.A.; Cherkashina, N.I.; Pushkarshaya, D.V.; Forova, E.V.; Ruchiy, A.Y.; Domarev, S.N. Polylactide-Based Polymer Composites with Rice Husk Filler. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwaningsih, H.; Ervianto, Y.; Pratiwi, V.M.; Susanti, D.; Purniawan, A. Effect of Cetyl Trimethyl Ammonium Bromide as Template of Mesoporous Silica MCM-41 from Rice Husk by Sol-Gel Method. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 515, 012051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Y.; Bian, Z.; Zhang, J.; Ding, A.; Liu, S.; Zheng, L.; Wang, H. Adsorption of Cadmium Ions from Aqueous Solutions by Activated Carbon with Oxygen-Containing Functional Groups. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2015, 23, 1705–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Wang, F.; Sun, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Wu, A.; Zhang, Y. Efficient Removal of Heavy Metal Ions from Wastewater and Fixation of Heavy Metals in Soil by Manganese Dioxide Nanosorbents with Tailored Hollow Mesoporous Structure. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 459, 141583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unlu, N.; Ersoz, M. Adsorption Characteristics of Heavy Metal Ions onto a Low Cost Biopolymeric Sorbent from Aqueous Solutions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 136, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Cui, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, J. Kinetic and Thermodynamic Study of Ag+, Cu2+, and Zn2+ Ion Adsorption on LTA for High-Performance Antibacterial Coating. Coatings 2024, 14, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.W. Ionic Hydration Enthalpies. J. Chem. Educ. 1977, 54, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Pawan; Sharma, S.; Mohit; Satjia, P.; Diksha; Priyanka; Thakur, Y.; Kaur, A. Copper(II) Ion Promoted Reverse Solvatochromic Response of the Silatrane Probe to Spectral Shifts: Preferential Solvation and Computational Approach. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 12043–12061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, J.M.; Pappalardo, R.R.; Marcos, E.S. A Molecular Dynamics Study of the Hydration Based on a Fully Flexible Hydrated Ion Model. J. Chem. Phys. 1998, 109, 1445–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, P.; Singh, B.; Angove, M. Competitive Adsorption Behavior of Heavy Metals on Kaolinite. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2005, 290, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Wang, J. A General Kinetic Model for Adsorption: Theoretical Analysis and Modeling. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 288, 111100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahkarami, E.; Allahkarami, E.; Azadmehr, A.; Shahrabadi, M.E. Kinetics and Statistical Physics Modeling of Heavy Metal Ions Adsorption onto Functionalized Pyrite Composite: Experimental and Modeling. Results Chem. 2025, 17, 102536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish, M.; Arman, I.; Al Mesfer, M.K.; Danish, M.; Ansari, K.B.; Aftab, R.A.; Zaidi, S. Mathematical Models for Characterizing Heavy Metals Batch and Column Adsorption: Study of Adsorption, Transport Parameters, and Numerical Computation Cost. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2025, 50, 3821–3839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Tian, S.; Zhu, Y.; Zhong, W.; Qiu, R.; Han, L. Insight into the Adsorption Isotherms and Kinetics of Pb(II) on Pellet Biochar via In-Situ Non-Destructive 3D Visualization using Micro-Computed Tomography. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 358, 127406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Can, N.; Omur, B.C.; Altindal, A. Modeling of Heavy Metal Ion Adsorption Isotherms onto Metallophthalocyanine Film. Sens. Actuat. B Chem. 2016, 237, 953–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbas, A. Heavy Metal Adsorption onto Agro-Based Waste Materials: A Review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 157, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soetaredjo, F.E.; Kurniawan, A.; Ki, O.L.; Ismadji, S. Incorporation of Selectivity Factor in Modeling Binary Component Adsorption Isotherms for Heavy Metals-Biomass System. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 219, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhurry, S.; Saha, P.D. Biosorption Kinetics, Thermodynamics and Isosteric Heat of Sorption of Cu(II) onto Tamarindus indica Seed Powder. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2011, 88, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Z.; Gao, B.; Mosa, A.; Yu, H.; Yin, X.; Bashir, A.; Ghoveisi, H.; Wang, S. Removal of Cu(II), Cd(II) and Pb(II) Ions from Aqueous Solutions by Biochars Derived from Potassium-Rich Biomass. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 180, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poo, K.M.; Son, E.B.; Chang, J.S.; Ren, X.; Choi, Y.J.; Chae, K.J. Biochars Derived from Wasted Marine Macro-Algae (Saccharina japonica and Sargassum fusiforme) and Their Potential for Heavy Metal Removal in Aqueous Solution. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 206, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, A.; Sisnandy, V.O.A.; Trilestari, K.; Sunarso, J.; Indraswati, N.; Ismadji, S. Performance of Durian Shell Waste as High Capacity Biosorbent for Cr(VI) Removal from Synthetic Wastewater. Ecol. Eng. 2011, 37, 940–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, G.; Xu, W.; Li, T.; Xia, W. Characterization of Cr(VI) Removal from Aqueous Solutions by a Surplus Agricultural Waste—Rice Straw. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 150, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maneechakr, P.; Mongkollertlop, S. Investigation on Adsorption Behaviors of Heavy Metal Ions (Cd2+, Cr3+, Hg2+ and Pb2+) Through Low-Cost/Active Manganese Dioxide-Modified Magnetic Biochar Derived from Palm Kernel Cake Residue. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, B.C.; Aldrich, C. Biosorption of Heavy Metals from Aqueous Solutions with Tobacco Dust. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 5595–5601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, T.A.; Volesky, B.; Mucci, A. A Review of the Biochemistry of Heavy Metal Biosorption by Brown Algae. Water Res. 2003, 37, 4311–4330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsawy, T.; Rashad, E.; El-Qelish, M.; Mohammed, R.H. A Comprehensive Review on the Chemical Regeneration of Biochar Adsorbent for Sustainable Wastewater Treatment. npj Clean Water 2022, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renu; Sithole, T. A Review on Regeneration of Adsorbent and Recovery of Metals: Adsorbent Disposal and Regeneration Mechanism. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2024, 50, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jevremovic, A.; Rakovic, M.; Lezajic, A.J.; Uskokovic-Marmovic, S.; Vasiljevic, B.N.; Gavrilov, N.; Bujuk-Bogdanovic, D.; Milojevic-Rakic, M. Regeneration or Repurposing of Spent Pollutant Adsorbents in Energy-Related Applications: A Sustainable Choice? Sustain. Chem. 2025, 6, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Bai, Y.; Pan, Y.; Chen, C.; Yao, S.; Sasaki, K.; Zhang, H. Application of Geopolymer in Stabilization/Solidification of Hazardous Pollutants: A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 4570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, C.; Rao, Y.; Yu, C.; Luo, Z.; Zhao, H.; Wang, X.; Wu, C.; Wang, Q. Solidification/Stabilization and Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in Municipal Solid Waste Incineration Fly Ash: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 892, 164451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.