Abstract

In the face of rapid aging, depression in later life has become a prominent issue in urban public health and environmental research. As potential places for social activities and emotional healing, the social stayability of shaded community spaces is an essential environmental factor influencing the mental well-being of the elderly. In order to overcome the challenge of depression relief in later life, it is important to investigate what attributes of social stayability in shaded spaces influence the mental well-being of the elderly, as well as their gap structures. This study innovatively develops a fuzzy multi-criteria decision-making method and builds an analytical framework combining Fuzzy-BWM and VIKOR to comprehensively evaluate three dimensions of physical accessibility, facilities, and spatial conditions, and environmental comfort and safety of shaded spaces. Using the Pioneer community in Panyu, Guangzhou, and the Yuehan community in Macau as empirical cases, this study integrates expert judgment and residents’ perception data to identify the key attributes and gap structure of shaded space stayability in mitigating depression-related psychological risk and promoting emotional restoration and psychological well-being among older adults. The results show that facilities and spatial conditions have the greatest impact on social stayability. The two attributes of sitting comfort and public service facilities are the dominant factors that affect stay intention and emotional recovery. Environmental comfort and safety have a secondary but stable supporting effect on psychological security. This study reveals the coupling relationship between functional configuration and perceptual experience and advocates for the transformation of urban renewal thinking from spatial optimization to psychological health promotion. This study’s results offer theoretical support and policy implications for building restorative, inclusive, and age-friendly cities. The findings provide a quantitative basis for decision making regarding sustainable community space governance and intervention prioritization.

1. Introduction

Population aging is one of the most significant demographic transitions of the 21st century. It is expected that the world population aged 60 years and above will increase at an unprecedented rate in the next few decades [1]. As the most populous nation in the world, China has experienced a significant aging trend in recent years. In 2020, the Seventh National Census showed that the proportion of the population aged 60 and above and 65 and above reached 18.7% and 13.5%, respectively [2]. Aging is more than a demographic process; it is also a process that affects many aspects of human life, such as health, social relationships, and the spatial environment [3]. Of course, health problems are critical in an aging society, and people’s concerns about health have also evolved from preventing single physical diseases to exploring the essence of psychological and social health [4]. Among them, depression is considered the most typical psychological disorder and social vulnerability among the elderly [5]. Depression is a multidimensional mental disorder that features a systemic disturbance of emotion, cognition, and social function. It originates from the interaction of neurobiological imbalance, psychological vulnerability, and social deprivation. It is one of the most tenacious and destructive health burdens in modern aging societies [6]. Since this emotional state is closely related to social relationships and social interactions, community public spaces, as the crossroads of social relationships and emotional experience, are important places to reshape the mental health of the elderly [7]. Among them, outdoor spaces with green shade and restorative functions can reduce the threshold to use the environment, increase opportunities for social interaction, and play a unique role in alleviating depression in lonely elderly people [8,9].

Previous research on community public spaces has shown that neighborhood green spaces and street shade can significantly increase opportunities for elderly residents to go out and stay, thereby creating everyday social spaces that help alleviate depressive symptoms and improve psychological well-being [10]. At the same time, the social stayability of shaded areas often depends on the combined effects of multiple specific attributes, including physical accessibility [11], seat and facility conditions [12], thermal comfort in the environmental dimension [13], and a sense of security [14], as well as neighborhood visibility and interaction opportunities in the social dimension [15]. These attributes do not function in isolation but promote social interaction and emotional restoration through the synergistic effect of “use–stay–socialize,” thereby alleviating depressive symptoms among the elderly to a certain extent [16]. However, most existing studies rely on the subjective perceptions and evaluations of community green spaces by the elderly [17,18,19,20], rather than adopting objective measures (such as the number of seats, shade coverage, and visual transparency). This reliance on subjective evaluation may weaken the practical guiding value of research findings on community space governance and design optimization. More importantly, most existing studies still tend to analyze each attribute as an independent variable, lacking a systematic examination of their interaction mechanisms and relative weight distributions [21]. It is important to clarify that, although depression is clinically defined as a mental disorder, this study does not aim to diagnose or assess clinical depression among older adults. Rather, the focus is placed on depressive symptoms as they are experienced in everyday life contexts, particularly core manifestations such as low mood and reduced interest or pleasure. This conceptualization is well established within environmental health and public health research, where the emphasis lies on population-level mental health outcomes rather than clinical diagnosis. Previous studies have demonstrated that validated self-report instruments are capable of reliably capturing these core depressive symptoms and are widely applied in depression screening and risk identification at the population level. Compared with clinical diagnostic criteria, symptom-based measures are more responsive to variations in daily environmental and social conditions, making them especially suitable for examining how community spatial characteristics relate to mental health. Within this research context, depressive symptoms are therefore not treated as a proxy for clinical diagnosis, but as a theoretically grounded and empirically valid outcome variable that reflects older adults’ emotional responses during everyday spatial use and social interaction.

In addition, previous studies have mostly employed linear statistical modeling methods to explore the relationship between attributes of community green spaces or tree-shaded environments and depression, as well as subjective feelings among the elderly. For example, some studies have used structural equation modeling (SEM) to examine the relationships among community environmental quality, social interaction, and depressive symptoms in older adults [22]. Although the mechanism by which the community environment indirectly affects depression through social connections and emotional recovery pathways has been revealed, it often simplifies the generation mechanism of mental health into a static causal chain, ignoring the potential synergy and feedback relationships among spatial attributes. Some studies have also verified the correlation between green space exposure and depression in older adults based on large-scale samples; however, their indicators mainly remain at the macro level, such as the total amount of green space and frequency of visits, while neglecting the spatial details of older adults’ daily stays and social experiences [23]. Although its regression framework, based on linear regression, has enabled overall trends to be identified, it is still challenging to identify interactions and priorities among different spatial elements. As a result, it is also hard for the method to explain psychological mechanisms and support design practices. Hence, this study expresses the belief that previous research may have overlooked the comprehensive role of different shaded social stayability attributes in alleviating depression in the elderly. This may further lead to a decrease in the efficiency of resource allocation in community space optimization and governance [24]. Therefore, this study attempts to overcome the aforementioned deficiencies by addressing the following two key issues:

- (1)

- Which environmental elements of shaded community spaces play the most important role in alleviating depression in the elderly?

- (2)

- Which attributes of tree-shaded social spaces show obvious deficiencies and need to be given priority attention in optimizing community spaces to alleviate depression and promote the mental health and emotional well-being of the elderly?

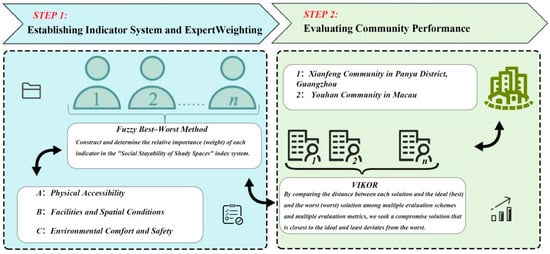

Based on the above, the present study used a Fuzzy BWM–VIKOR model and randomly chose the Xianfeng community in Panyu District, Guangzhou, and the Yuehan community in Macau as empirical cases to study the attributes of community tree shading and social stayability in alleviating depression. Unlike previous studies using linear analytical frameworks largely based on subjective perceptions of the elderly, this study combined older adults’ subjective perceptions and objective environmental measurements. It used a multi-attribute decision making analysis based on field data to explore and identify spatial deficiencies and give priority to intervention. The research findings not only enriched scholars’ understanding of the relationship between community environments and depression in home-based care but also provided evidence bases for optimizing resource allocation and setting intervention priorities in community space planning and governance.

2. Methodology

2.1. Construction of Evaluation Index System

Within the analytical frameworks of environmental psychology and urban design, the built environment is widely regarded as playing an important role in shaping the social participation and emotional well-being of older adults [25]. Different attributes of social lingerability of shaded spaces are believed to have different impacts on older adults’ lingering behavior and social behavior in spaces, which in turn helps to alleviate depression [12,26]. In the field of restorative environments, micro-scale environment factors, such as shade, seating, and green spaces, are believed to have a significant impact on psychological restoration and social tendency [27]. However, the “Age-Friendly City” framework proposed by the World Health Organization systematically classifies spatial conditions, but it is still largely macro-dimensional at the city level and cannot reflect the micro-scale spatial attributes of everyday community shaded spaces [28]. Therefore, based on the above theoretical frameworks and related studies, it is necessary to construct a measurement index system that can better reflect the characteristics of social stayability of community spaces.

Accessibility is the basic prerequisite for social stay in shaded spaces. Walking accessibility and road connectivity are believed to have a significant impact on outdoor activities and social behavior of older adults, and thus can alleviate depression by promoting social participation, improving social connections and the emotional experience [29,30]. The lack of public transportation access further leads to poor mobility and social exclusion, which reduces the potential benefits of using shaded spaces for social and psychological well-being [31]. In terms of the effectiveness of facilities and spatial conditions in alleviating depression in the elderly, there are different conclusions in empirical studies. Some studies found that better seating and public facilities could significantly prolong the time of stay of older adults and promote social behavior, which in turn could improve psychological restoration and positive emotions [32,33]. However, some studies found that if the spatial scale or layout is not suitable for users’ needs, the usage rate of facilities will decrease significantly, even when they exist [34]. This shows that the effectiveness of the use of facilities and spatial conditions is not linear, but depends on whether the facilities and spatial environment can meet the actual needs of older adults. In addition, the environment of comfort and safety also affects older adults’ use of shaded spaces. Adequate shading and effective regulation of microclimate can significantly alleviate heat distress, which, in turn, prolongs outdoor stays, improves positive emotions and social behavior, and further alleviates depression [35]. In addition, insufficient lighting at night, line of sight blockage, or excessive seclusion will make the space unoccupied or abandoned due to a lack of a sense of security [36,37]. Therefore, environmental comfort and safety determine not only whether older adults can stay, but also whether they dare to stay. They serve as an essential guarantee for the social and psychological health benefits of shaded social spaces. Accordingly, after reviewing relevant empirical research, the evaluation indicators used in this study are presented as follows (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Evaluation metrics.

2.1.1. Physical Accessibility

Physical proximity determines whether shaded spaces can actually be part of older adults’ lives [49]. Proximity in space is not associated with geographical distance, but rather measured by the time it takes to walk and the continuity of the path. If the route is interrupted or has to make a detour, even a short straight-line distance can decrease the probability that older adults go out [38,50]. For older adults, if physical function declines, access to public transportation becomes an important factor in maintaining independent mobility and in frequently visiting places beyond walking distance [40]. At the same time, the convenience of access is not only related to physical proximity. Physically accessible ramps, clear signs, and continuity of the pedestrian route can minimize feelings of exclusion and inferiority among older adults due to their mobility restrictions or disorientation, thus helping them enter the space and maintain social relations [51].

2.1.2. Facilities and Space Conditions

Facilities and spatial conditions make it possible for older adults to stay in shaded spaces [52]. Comfortable and sufficient seating makes older adults stay longer and increases the duration of social interaction, and facilities like drinking water points and public restrooms physically and psychologically encourage older adults to go out [12,53]. Sunshades and rain shelters make it possible for the shaded space to keep its social functions during extreme weather conditions. It has been proven that pavilions and corridors can provide physical protection during hot and rainy weather conditions, make older adults stay longer, and maintain the regular duration of social interaction [44]. Meanwhile, if the space is reasonably divided, older adults can find quiet corners to rest in shaded spaces, and they can also find open spaces to gather in groups. Using this hierarchical layout, they can choose to stay outside or inside according to the situation and participate in social activities more freely [45].

2.1.3. Comfortable and Safe Environment

Comfortable and safe environments directly impact the sustainability, risk feeling, and emotional recovery of older adults in shaded spaces [54]. An adequate and persistent tree canopy can provide shade, moderate the thermal environment through transpiration, enhance the physical comfort of older adults, prolong their time spent in shaded spaces, and increase opportunities for social interaction [55]. Thermal comfort is an overall reflection of the microclimate. When the design of shaded space considers the thermal comfort of older adults, the overall comfort and tolerance of older adults will be greatly enhanced. It can prolong their stay duration and increase opportunities for social interaction [56]. Uniform daytime lighting can reduce glare, while a well-designed night-time lighting layout can enhance visibility and reduce the risk of falls. Older adults can stay and communicate more safely in shaded spaces [57,58]. At the same time, a larger proportion of green natural elements perceived in a shaded space supports improved mental health and less stress, a more aesthetic and restorative experience, and older adults’ willingness to go out and socialize [59].

2.2. Methods for Exploring the Relationship Between Social Stayability in Tree-Shaded Spaces and Depression in the Elderly

In recent years, numerous studies have employed various correlation analysis models to examine the effects of urban environmental characteristics on depression among older adults. For example, P. Wang et al. (2024) employed a multilevel logit regression model and found that the tree coverage rate around residential areas was significantly negatively correlated with depressive symptoms among older adults: the higher the level of community greening, the lower the risk of depression [60]. In addition, a study using a structural equation model found that, after controlling for demographic characteristics, community park green spaces had a direct and significant alleviating effect on depression among older adults. At the same time, green spaces also indirectly reduced depression levels by promoting social interaction and emotional recovery [22]. In addition, several studies have examined the relationship between the perceived neighborhood environment and depression among older adults using a multiple mediation model. Results showed that older adults’ satisfaction with community health services, safety, and leisure resources can reduce depressive symptoms significantly through cognitive social capital [61].

In addition to the quantitative models shown above, some empirical studies have also explored the impact of multidimensional elements in community spaces on the alleviation of depression among older adults. For example, Wang et al. used street-view image data to quantify visual green spaces in urban communities in Shanghai and then integrated it with structural equation modeling (SEM) to study its impact on depression among older adults [62]. Results showed that the more greenery present within the older adults’ visual field, the less depression they exhibited, and this effect of greenery was mainly realized through promoting social interaction and emotional recovery from depression, i.e., an indirect effect. Furthermore, tree-shaded spaces with relatively good visibility and pedestrian-friendly design can enhance older adults’ sense of belonging and psychological resilience and maintain a depression-alleviating effect in the process of their daily activities [62].

Although the existing literature is constantly deepening the understanding of the association between the community environment and depression among older adults, most research methods are still limited to statistical correlation analyses, such as linear regression or structural equation modeling. These methods adopt an isolated and linear perspective on the relationships between environmental factors and depression among older adults. Therefore, correlation-based approaches, which depend on assumptions that hold only under certain conditions, cannot reflect the multidimensional and complex impact of environmental factors on the perception and decision making of older adults in real-world scenarios [24]. They are also unable to reflect the comprehensive impact of multiple environmental factors on the perception and decision making of older adults [63]. Therefore, there is still a research gap in exploring the comprehensive impact of specific elements of community spaces on depression among older adults. This study uses a multi-attribute decision making analysis to explore the comprehensive impact of attributes of community spaces related to shaded social spaces and stayability on depression in older adults. This is very important for helping decision-makers make optimal decisions regarding the physical environment of communities and allocate resources (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Data sources and measurement methods of indicators.

2.3. The Fuzzy Best–Worst Methodology

In multi-criteria decision making (MCDM) research, pairwise comparison is a key and widely used method. It transforms experts’ subjective judgments from qualitative information into quantitative data and calculates the corresponding weights. However, traditional approaches are often tedious and complex in practical application. For example, the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) requires decision-makers to make at least n(n − 1)/2 pairwise comparisons when evaluating n criteria. This exponential growth not only increases the workload but also easily causes cognitive fatigue and judgment bias [64]. In practice, almost inevitably, there will be inconsistencies in pairwise comparisons. As multiple studies have pointed out, the consistency test of AHP often fails in complex systems, which subsequently leads to unreliable and unclear outputs [65]. In order to overcome the drawbacks of the traditional pairwise comparison method, the best–worst method (BWM) has been proposed to simplify the evaluation process by requiring individuals to only compare the most and least important criteria from all compared criteria, which subsequently reduces the workload and enhances consistency [66,67]. In many real-world scenarios, experts tend to express their judgments in verbal form, such as referring to a criterion as being “moderately important” or “very important” instead of assigning specific scores. Qualitative reasoning is difficult to convert into quantitative form, which subsequently leads to a certain loss of information [68]. To overcome the aforementioned issues, researchers have further developed the BWM method by incorporating fuzzy set theory into the model, which has been previously reviewed as Fuzzy-BWM [69].

Experts’ linguistic judgments, such as being “very important”, are transferred into triangular or trapezoidal fuzzy numbers, which are subsequently processed using a fuzzy optimization model to estimate the weights of criteria, which are finally defuzzified and normalized to obtain final crisp values. The Fuzzy-BWM method overcomes the issue of subjectivity and linguistic judgment while still maintaining the advantage of the original BWM method. Since its first proposal, the method has been applied in various research fields. Multiple recent reviews state that the method is not only used on its own, but also used in combination with various multi-criteria decision-making methods, which subsequently lead to more reliable and interpretable outputs [67]. Since then, the method has found increasing applications in various fields such as sustainable development, transportation, healthcare, urban design, etc. [64,70]. For example, Amiri et al. (2020) combined BWM with the fuzzy aggregation method when applying it to evaluate hospital performance in order to determine the relative importance of evaluation criteria [71,72].

In this study, Fuzzy-BWM is applied as an extension of the traditional best–worst method (BWM) and incorporates fuzzy set theory to better reflect the uncertainty that appears in experts’ linguistic judgments. In practice, the procedure can be divided into the following main steps [67]:

Step 1: Define a set of standard criteria, such as accessibility, seating and facilities conditions, thermal comfort and safety, and social dimensions such as neighborhood visibility and opportunities for interaction .

Step 2: Each expert first selects the most important criterion as the best criterion and the least important criterion as the worst criterion.

Step 3: Based on fuzzy pairwise comparison, obtain the relative importance evaluation between the optimal criterion and the remaining criteria.

Step 4: Based on fuzzy pairwise comparison, obtain the relative importance evaluation of all criteria relative to the worst criterion.

Step 5: Obtain the optimal fuzzy weights of each criterion by solving the nonlinear optimization model Formula (9).

In order to derive the optimal weights, the following min–max problem should be constructed [67]:

where and represent the pairwise comparisons between the best criterion and the other criteria and between the other criteria and the worst criterion, respectively. The basis of this method is to minimize the maximum absolute difference between the weight ratio and the number of pairwise comparisons.

In order to overcome the uncertainty of expert judgment, fuzzy theory is proposed to cover a wider range of expert opinions. Each fuzzy number (l, m, u) consists of three parts: a lower bound (l), a middle bound (m), and an upper bound (u). In addition, the fuzzy number follows a specific membership function, as shown below [73]:

The fuzzy arithmetic operator of two fuzzy numbers and can be calculated:

According to Formula (1), taking into account the fuzziness in expert judgment, the fuzzy weight is obtained by calculating the following nonlinear problem [74]:

where and are the fuzzy pairwise comparisons of the best criterion with other criteria and the fuzzy pairwise comparisons of all criteria with the worst criterion, respectively. The fuzzy pairwise comparison is performed according to the language table shown in Table 1. The optimal weights and are obtained by solving (9). In order to simplify the process of the proposed fuzzy BWM method, the pseudo code design is shown in Equation (1).

The algorithm includes fuzzy pairwise comparisons of the best criterion with other criteria and fuzzy pairwise comparisons of all criteria with the worst criterion. The fuzzy pairwise comparisons are performed according to the language table in Table 1. By solving (9), the optimal weights are and . In order to facilitate the implementation of the proposed fuzzy BWM method, the pseudo code shown in Equation (1) is designed (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Triangular fuzzy scales used for pairwise comparisons.

The clear weight is obtained by converting the fuzzy weight (10):

The reliability of the obtained fuzzy weights can be tested by evaluating the consistency ratio (CR) metric. The closer the CR is to zero, the more accurate the weights are. If , the pairwise comparisons are completely consistent; otherwise, they are inconsistent. Therefore, the maximum inconsistency occurs when both and are equal to . The CR of fuzzy pairwise comparison is evaluated based on the following formula:

where is the clarity value of obtained by solving Formula (9), and CI is the consistency index evaluated according to Formula (12).

where is the upper bound of the maximum value for pairwise comparisons.

2.4. VIKOR Technique

As one of the multi-criteria decision making (MCDM) methods, VIKOR is widely used to rank and prioritize candidate solutions based on established evaluation criteria. The core idea is to evaluate each solution by comparing its closeness to the ideal solution, where the optimal solution should show the smallest deviation from the ideal solution. As a compromise ranking method, VIKOR is particularly suitable for dealing with situations where there are conflicting evaluation criteria. Its typical implementation process usually includes five main steps [75,76].

Step 1: Create a decision matrix.

In the context of this study, the decision matrix is defined as a matrix structure that presents the performance of different community tree-lined social spaces under given evaluation attributes. When there are m community spaces to be evaluated and n indicators related to the social stayability of the tree-shaded area, the corresponding decision matrix can be expressed as follows:

Step 2: Determine the best and worst values for all criteria.

In this step, it is important to first identify benefit criteria (BC) and non-benefit criteria (NC). Benefit criteria, such as shade coverage, seating comfort, or green visibility, are attributes whose higher values contribute to improved social engagement and, in turn, alleviate loneliness among older adults. Cost criteria, on the other hand, are attributes whose lower values are more desirable, such as walking distance to a space or ambient noise levels. On this basis, the optimal value () and the worst value () of each indicator can be further defined.

Step 3: Calculate the values of utility metric () and regret metric ().

In the VIKOR method, the LP metric is used as an aggregation function to achieve trade-off ranking of solutions. and are regarded as and , respectively. The LP metric is defined as follows:

According to Formula (16), the parameters and are used to reflect two types of information, respectively: among them, represents the “group utility” or majority opinion measured from the overall perspective, while reflects the minimum individual regret value from the opposing perspective.

where is the weight of the criterion derived from the fuzzy BWM.

Step 4: Calculate the VIKOR index ().

where v is the maximum group utility weight (usually set to 0.5), and the other values are , ,

Step 5: Prioritize the tree-lined social spaces in each community from small to large based on the value of the compromise ranking index .

In the final step, the optimal community shaded social space needs to be determined. Specifically, the space corresponding to the minimum value of the compromise ranking index is regarded as the solution with the best overall performance. In the implementation of the VIKOR method, after sorting , and in descending order, two conditions need to be further tested to ensure the validity of the optimal solution. First, it is necessary to verify whether the “acceptable advantage” is established through the following formula.

In Formula (20), and represent the first-ranked and second-ranked community tree-lined social spaces, respectively, and is the total number of evaluated spaces. If this condition is not met, the set ,…, is considered the optimal solution, where k is the maximum number that satisfies The second condition is called “acceptable stability”, which means that the community space ranked first should also be ranked first in the ranking of and/or . If this condition is not met, and should be considered as the best options. It should be pointed out that the process of identifying critical community spaces should adopt a reverse testing method; that is, the critical solution should be finally confirmed by sorting the VIKOR index in ascending order (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of research methods (all graphical elements were created by the authors based on original data and analyses).

3. Empirical Research

3.1. Empirical Case Description

The Greater Bay Area—famous for its highly dense urban pattern, institutional diversity, and coexistence of multiple cultures—has long served as an important center of economic activity and policy innovation. Within this context, we chose two communities for our case studies, namely, the Xianfeng community in Guangzhou’s Panyu District and the Yuehan community in Macau. A comparison of the two communities may shed light on how the urban form and renewal stage would affect the relationship between tree-shaded social accessibility and the mental well-being of older adults. In addition, we examined the environmental performance of the two communities. Based on the findings, we further suggested context-specific guidelines for improvement.

Both neighborhoods can be described as aging community spaces shaped by long-established daily habits and a growing demand for environmental upgrading. Although they are situated in different cities, the Pioneer and Yuehan communities share comparable conditions—intensified aging, a shortage of public spaces, and untapped potential for shaded environments. In the past, their open areas were often underused. With recent renewal projects, however, traditional streets, greenery, and recreational zones have been gradually restored. While keeping their original spatial patterns, both communities have added walkways, seating, and shading systems through a series of small interventions, creating a better-connected network centered on shaded gathering points. Studying these two cases provides a useful basis for understanding how shaded social spaces evolve in different urban contexts and reveals both general and region-specific features of age-friendly design.

These two communities are different in community scale, renewal strategy, and daily use. The Pioneer community in Panyu is relatively large in scale and preserves the old network of alleys and lanes. The renovation strategy in Pioneer was to enhance lighting, walking, and recreation while preserving the old neighborhood layout—creating a new community with both a historic context and daily uses. In comparison, the Yuehan community is situated in a much more crowded district of Macau. The old neighborhood in Macau is facing micro-granularity problems of environmental renovation due to a lack of land. Pocket gardens, shading facilities, and corner resting areas were added to improve the daily use experience for the older residents. Although these daily uses improved conditions in the old neighborhood, the overall environment was still constrained at a dense level. In summary, Pioneer is more like a restoration of the environment of a traditional neighborhood, while Yuehan is more like refining the environment in an old town at the micro-granularity scale. These two cases show the diversity of strategies used in renovating old urban neighborhoods.

The two sites exhibited variation in shading form, facility conditions, and user density. To provide a solid foundation for the comparative analysis presented above, the research integrated resident questionnaires and field-based spatial measurements at two study locations. The two study locations were measured in terms of both subjective perception and objective environment. The two methods provided an empirical basis for ranking indicator weights and gap ranking using the Fuzzy-BWM and VIKOR models, respectively. This comparative analysis clarifies how the structure of tree-shaded social spaces in communities is different from one another in terms of type and provides a reference for related urban renewal projects and age-friendly environment planning.

3.2. Data Collection

In the data collection and respondent selection phase, 15 experts were sent the first-phase questionnaire of the fuzzy best–worst method (Fuzzy-BWM). To ensure the professional rigor and interdisciplinary validity of the indicator weighting process, the 15 experts involved in the first phase of the Fuzzy-BWM questionnaire were drawn from multiple disciplines closely related to community spaces and older adults’ mental health. Specifically, the expert panel comprised six specialists in architectural design, primarily engaged in public space design, community architecture, and age-friendly environment research; seven experts in urban and rural planning and urban design, with research and practical experience in community space planning, public space governance, or urban regeneration; and two mental health professionals, both psychologists with clinical or public mental health backgrounds who are familiar with the assessment of depressive symptoms and mental health issues among older adults. In the second phase, the VIKOR survey was administered to 280 residents in the Guangzhou and Macau areas (approximately 150 people aged 60 or above in Guangzhou and Macau, respectively). Twenty-two questionnaires were eliminated from the analysis due to the fact that their responses were completely identical. Experts were selected from “multi-disciplinary collaboration and complementary expertise”. Most experts were from urban planning, architectural design, and psychology. In the first phase, the experts in these fields evaluated the importance and relative weights of the “shaded social stayability” indicators for depression in older adults based on their experience and judgment. All participants should have a rich theoretical or practical basis in certain fields, for example, landscape architecture or environmental psychology. The expert panel for this phase included university faculty and medical experts to ensure the indicator system was both scientific and operational. The second phase (VIKOR) questionnaire was designed based on the indicator system established in the Fuzzy-BWM phase, using a 9-point Likert scale to collect elderly residents’ subjective evaluations of the social livability and psychological state of the tree-shaded space. This study deliberately differentiates the use of expert data and resident data to serve distinct methodological purposes. Expert judgments are employed in the Fuzzy Best–Worst Method (Fuzzy-BWM) to determine the relative importance of evaluation indicators, drawing on experts’ professional knowledge of spatial and environmental attributes. In contrast, resident survey data are used to assess the performance levels of these indicators, capturing users’ lived experiences and perceptual evaluations. By assigning experts and residents to separate roles in the weighting and evaluation stages, the approach reduces the potential influence of divergent value orientations on the results. This hierarchical integration of expert judgment and user perception is a well-established practice in multi-criteria decision-making research and is widely adopted to balance technical expertise with experiential evidence [45].

4. Research Results and Discussion

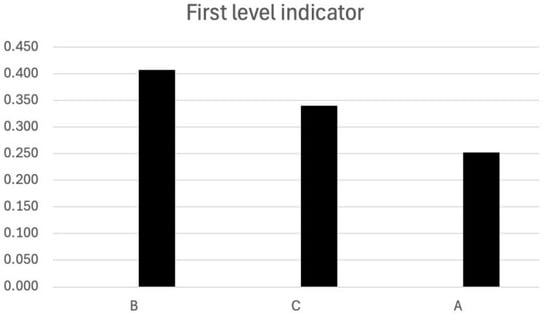

This study uses the Fuzzy-BWM (Fuzzy Best–Worst Method) to conduct a weight analysis of the indicator system to determine the importance level of each dimension and criterion and its relative influence in the overall evaluation system. The results show that the order of importance of the three first-level dimensions is facilities and spatial conditions (B) > environmental comfort and safety (C) > physical accessibility (A) (see Figure 2). This ranking reflects the general belief among experts that physical accessibility is a basic condition for improving the social stayability of shaded spaces, but the key to determining the long-term stay and social activity of the elderly lies in the comprehensive optimization of facility configuration and environmental quality.

Figure 2.

Weight distribution of first-level indicators (all graphical elements were created by the authors based on original data and analyses).

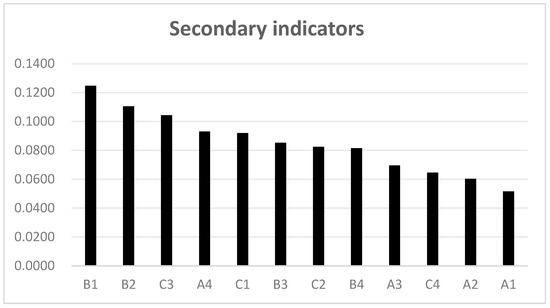

Specifically, the dimension of facilities and spatial conditions (B) has the highest weight, indicating that perfect functionality and spatial organization are the dominant factors in forming high-frequency usage behavior. In this dimension, indicators such as the number and comfort of seats (B1) and public service facilities (B2) have higher weights (see Figure 3), indicating that high-quality rest facilities and basic service configuration are the primary factors driving the use and social behavior of the elderly and are an important foundation for promoting interactive behavior and psychological safety. The environmental comfort and safety (C) dimension ranks second, with the weight concentrated on the two indicators of lighting and night lighting safety (C3) and green shade coverage (C1), indicating that lighting safety and shade supply at the environmental level have a direct impact on willingness to stay and psychological security. In contrast, physical accessibility is less important, but public transportation accessibility (A3) and convenient entrances and exits (A4) remain essential prerequisites for building an inclusive spatial system. This means that accessibility is essential as a prerequisite, but its marginal impact is lower than factors such as facility capacity and environmental safety/shading.

Figure 3.

Relative weights and rankings of secondary indicators (all graphical elements were created by the authors based on original data and analyses).

In summary, the results of Fuzzy-BWM reveal the hierarchical structure and interdependence of various dimensions in elderly-friendly tree-lined spaces: facility conditions are the core, environmental quality is the perceived support, and accessibility is the basic guarantee. Therefore, in the subsequent VIKOR improvement phase, this study determined the improvement order based on the principle of “high-weight dimensions first, key criteria first”. That is, priority should be given to optimizing indicators with higher weights and larger performance gaps in the facilities and spatial conditions dimensions while combining key elements of the environmental comfort and safety dimensions to form a multi-level and systematic improvement path. In addition, this method guarantees appropriate investment in the desired areas and offers a solid ground for gap value analysis in the following steps. After assigning weights to all the metrics, this study applies the VIKOR method to analyze the overall performance of the two empirical shaded social spaces: the Pioneer community in Panyu, Guangzhou, and the Yuehan community in Macau, and further identifies the gaps and improvement items. Based on the degree of deviation from the ideal solution for each criterion, the VIKOR model displays the structural gaps and optimization directions to develop age-friendly spaces in various communities.

The gap value represents the gap between the actual performance of a criterion and its expected level, and the total gap value represents the sum of the gap values of all criteria, which can be obtained by multiplying the local weight of each criterion by the gap value. Judging from the total gap value, the Youhan community (0.3851) performs better than the Xianfeng community (0.6405), but based on the expected level (0), both have not reached the ideal state, and there are still significant problems. Several improvements are needed to achieve the optimization goal of the shaded social space. At the dimensional level, the gap value in dimension B (facilities and spatial conditions) of the Xianfeng community is the largest (0.4654), while the gap value in dimension C (environmental comfort and safety) of the Youhan community is relatively prominent (0.6091), indicating that both places have weak links in functional configuration and environmental perception.

In order to formulate strategies to remedy these aspects, an in-depth discussion of the impact relationships between indicators is needed. In the Xianfeng community, the main indicators with significant disparities were A4 (accessibility, 1.0000), B1 (number and comfort of seats, 0.8934), and C2 (thermal comfort, 0.8250). In the Youhan community, the main indicators with significant disparities were B1 (number and comfort of seats, 1.0000), B2 (public service facilities, 0.7587), and C3 (night-time lighting safety, 0.6254). These results indicate that elderly residents are most sensitive to rest comfort, basic services, and night-time lighting, and these shortcomings directly affect their willingness to socialize and their sense of psychological safety.

In traditional improvement strategies, two communities prioritize improvements based on the metric with the largest gap. However, this model prioritizes key criteria with higher weight and influence. Therefore, combining a comprehensive analysis of weights and gaps, this study prioritizes improvements in high-weighted and high-gap indicators such as B1, B2, C3, and C2. Based on this, improvement strategies and phased optimization plans were developed for both communities.

4.1. Pioneer Community, Panyu, Guangzhou

For the Pioneer community, based on the performance evaluation results and combined with the Fuzzy-BWM weight analysis, its gap value in the facilities and spatial conditions (B) dimension is the highest (gap ratio: 0.4654). In addition, the Pioneer community also showed obvious deficiencies in environmental comfort and safety (C) (gap ratio: 0.2575) and physical accessibility (A) (gap ratio: 0.2771). The results show that the community as a whole has shortcomings in terms of spatial functions and environmental experience, and overall improvement is needed through cross-dimensional collaborative improvement. Performance evaluation results show that the indicator with the largest gap is B1 (number and comfort of seats, 0.8934), followed by C2 (thermal comfort, 0.8250) and A4 (accessibility, 1.0000). This indicates that the Pioneer community is clearly deficient in providing basic recreational facilities and a climate-adaptable environment, while issues with entrance organization and connectivity further weaken spatial accessibility and continuity.

From the perspective of the facility, although the Pioneer community offers some spaces for rest and recreation, the number of seats is very small, the distribution is unreasonable, and the design of these seats does not consider the ergonomics of older adults. Meanwhile, field survey results also show that many benches are exposed to the sunlight for a long time and lack shading, resulting in very little usage in the hottest months. Therefore, communities should conduct routine inspections and maintenance of shaded seating and popularize natural and artificial shading structures to ensure thermal comfort, such as tree canopies, pergolas, and awnings. In addition, the spatial layout should develop more small resting nodes along pedestrian paths to link the whole chain of social spaces. As for environmental comfort and safety, the Pioneer community has low levels of thermal comfort and night-time illumination. Many tree-lined spaces lack lighting, resulting in glare, uneven brightness, and light decay, which impair residents’ sense of safety and reduce evening social activities. Therefore, upgrading the lighting system and combining it with road and landscape design can create a visually comfortable and safe night-time environment. In addition, improving the continuity of greenery and developing ventilation corridors can improve the regulation of microclimate and enhance comfort. Furthermore, accessibility is also a big problem. The entrance–exit convenience gap ratio was 1.00000, which exposed the confusion of circulation and poor legibility of the entrance. In some areas, there were steep steps and a lack of barrier-free links, which were inconvenient for residents without much mobility. Therefore, improvements should focus on making a clear and continuous barrier-free guidance to link up the entrances and exits, as well as the main pedestrian paths.

In summary, the evaluation result shows that the Pioneer community has obvious defects in facility quality and environmental comfort. When re-ranked from the “impact-first” perspective, the indicators B1, A4, and C2 should be prioritized in the improvement strategy, and it is recommended that the communities develop a coordinated strategy combining the improvement of facilities with the development of environmental safety to create a tree-shaded spatial system for older adults through both functional usability and a stronger sense of safety. Through such integrated development, the system can gradually narrow the gap between the current state and the optimal state.

4.2. Macau Youhan Community

Based on the Performance Center’s evaluation of the Youhan community, the comprehensive performance of the community was better than that of the Pioneer community. However, the largest gap appeared in the dimension of facilities and spatial conditions (B, gap ratio: 0.6091), followed by environmental comfort and safety (C, 0.2460) and physical accessibility (A, 0.1449). Specifically, the largest gaps were in B1 (number and comfort of seats, 1.0000), B2 (public service facilities, 0.7587), and C3 (night-time lighting safety, 0.6254). In other words, although the tree-shaded system of Youhan is relatively mature and public space is dense, the old facilities and insufficient night-time lighting restrict seniors from staying outdoors for longer and make them less willing to communicate.

Examining facilities in more detail, most public facilities in older residential buildings were created several decades ago. They now provide too few seats, are dispersed across the space, and use worn materials that undermine spatial coherence. Seating needs to be renewed and linked coherently—high-backed shaded benches need to be added along major green corridors and social plazas, and connected to smaller shared spaces to create a step-by-step linked network of resting places that enhance accessibility and interaction among older residents. Environmental comfort and safety can also be undermined by blind spots and increased risk of falls created by uneven night lighting and overly dense shading. The addition of smart lighting with low-light zoning and energy-efficient sensor lamps would enhance brightness balance. Further improvements could be achieved with clearer safety and directional signage at entrance and intersection points. Overall, accessibility to facilities across the site is fairly equitable, although a few peripheral areas still contain elevation changes, steps, and narrow walkways. The addition of continuous ramps, non-slip surfaces, and shaded pedestrian routes would enhance safety and accessibility for the elderly by making the environment more inclusive. In summary, the Youhan community should focus on facility renewal in conjunction with enhancing night-time safety. Ranked by their impact, calling for a phased pathway of facility maintenance, safety enhancement, and spatial integration in response to indicators B1, B2, and C3 would create an integrated intervention that would simultaneously enhance functional performance and psychological comfort and strengthen the social vitality of this age-friendly shaded environment.

By comparing the similarities and differences in community improvement strategies across the two case studies, it can be concluded that even the Pioneer community in Panyu, Guangzhou, and the Yuehan community in Macau are both high-density aging communities with similar core problems of social stayability in tree-lined spaces. The Xianfeng community lacks in B1, C2, and A4, while the Youhan community lacks in B1, B2, and C3. This suggests that the former urgently needs to improve its spatial carrying capacity by improving node facilities and pedestrian systems, while the latter should improve environmental safety and psychological comfort through facility upgrades and lighting optimization. However, from an impact perspective, the improvement paths for both communities are essentially the same: both should focus on high-weighted dimensions, prioritize narrowing performance gaps in high-gap indicators, and achieve systematic improvements within limited resources. In other words, coordinated improvements in functional improvement, environmental safety, and equitable accessibility are the keys to building age-friendly shaded spaces (see Table 4).

Table 4.

The performance evaluation of the case study using VIKOR.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

This study uses community tree-lined spaces as an analytical entry point to systematically examine how the built environment shapes older adults’ emotional experiences and depression-related psychological processes through everyday use contexts. Rather than conceptualizing environmental elements as isolated stimuli, this study argues that the psychological significance of tree-lined spaces is not determined by any single physical attribute. Instead, it emerges through an integrated environmental mechanism—stayability—which structurally links spatial conditions, opportunities for social interaction, and subjective perception, thereby influencing older adults’ staying behavior and emotional restoration.

Building on this perspective, this study introduces tree-lined social stayability as a mediating concept for understanding the psychological effects of community spaces and elucidates its internal structure from a multi-attribute decision-making perspective. The findings indicate that environmental attributes do not exert uniform effects; rather, their influence on older adults’ emotional experience depends on their relative weights and synergistic relationships. Notably, facilities and spatial conditions consistently emerge as critical deficiencies across different communities, suggesting that functional support and spatial organization are not secondary contributors to emotional restoration, but constitute the structural foundation shaping older adults’ everyday willingness to stay and their sense of psychological security. By foregrounding this mechanism, this study extends existing research that has predominantly focused on green space quantity or aesthetic qualities, offering a more hierarchical and process-oriented theoretical framework for explaining how community environments affect older adults’ psychological experiences.

At the methodological level, this study does not simply employ Fuzzy-BWM and VIKOR as tools for indicator ranking. Instead, it adopts them as complementary analytical strategies for addressing the inherent complexity of environment–psychology relationships. Fuzzy-BWM accommodates the ambiguity and inconsistency inherent in expert cognition, reducing reliance on singular subjective assumptions during weight elicitation. VIKOR, through the introduction of gap and compromise solutions, transforms environmental assessment from static comparison into a structural diagnostic process oriented toward intervention prioritization. Their integration enables the identification of environmental attributes with the greatest structural influence on emotional restoration under conditions of limited sample size and complex variable interdependence, thereby overcoming the limited explanatory depth and weak decision orientation of conventional correlation-based or single-indicator approaches.

From a practical standpoint, the findings further demonstrate that the influence of community environments on older adults’ emotional experiences does not arise from any single “better” spatial feature. Rather, it depends on whether multiple environmental elements collectively generate a perceptible, engaging, and socially supportive experience in daily use. Accordingly, the optimization of age-friendly communities should move beyond isolated facility provision or landscape enhancement and instead adopt an integrated approach centered on stayability, coordinating spatial functionality, environmental comfort, and social support conditions. From this perspective, this study provides an interpretable, comparable, and decision-oriented analytical pathway for understanding and intervening in depression-related psychological risks among older adults at the community scale.

5.2. Limitations

Despite constructing a systematic evaluation and improvement framework based on Fuzzy-BWM and VIKOR, this study is subject to several limitations that warrant clarification. First, the expert judgment process primarily involved scholars from urban planning, architecture, and psychology. While this composition ensured a degree of interdisciplinary balance, it did not fully incorporate perspectives from applied fields such as medicine or social work. As a result, the weighting outcomes may have limited explanatory depth with respect to mental health-related interpretations.

Second, the VIKOR analysis was based on only two community cases—the Xianfeng community in Panyu District, Guangzhou, and the Youhan community in Macau—resulting in a constrained empirical scope. Although both communities are representative of high-density aging contexts, their environmental characteristics, social configurations, and institutional settings remain context-specific. Accordingly, the findings should be interpreted with caution and should not be directly generalized to broader urban scales or to the normative concept of “inclusive cities.”

In addition, regional differences in cultural background, social interaction patterns, and climatic conditions may substantially influence how older adults engage with tree-lined spaces and how they prioritize environmental attributes. For instance, the relative importance of shade, ventilation, or thermal comfort may vary across climatic zones, while culturally embedded norms of neighborhood interaction and public space use may shape the mechanisms through which shaded environments support social staying. Future research would benefit from comparative studies across communities situated in diverse cultural and climatic contexts to further assess the robustness and transferability of the proposed framework.

Moreover, this study relies on cross-sectional data, capturing older adults’ emotional experiences and spatial use at specific points in time. Such an approach limits the ability to examine the dynamic interactions between environmental interventions and psychological responses over longer periods. Longitudinal designs incorporating behavioral observation would allow for a more nuanced understanding of the temporal effects of shaded space interventions.

Finally, although the proposed model integrates multi-attribute decision-making and fuzzy inference techniques, discussions of mental health and mood-related outcomes are derived from inferential analyses of environmental and social perception variables rather than from direct psychological or clinical measurements. Future studies could incorporate validated psychological scales, physiological indicators, or wearable sensing technologies, combined with environmental sensor data, to develop a more comprehensive and dynamically responsive evaluation framework. Overall, while this study provides a quantifiable analytical framework and decision-support reference for optimizing age-friendly tree-lined spaces, further expansion in sample coverage, contextual diversity, and temporal validation is necessary to strengthen the robustness and policy relevance of its conclusions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M. and J.Z.; methodology, S.M. and K.L.; software, S.M.; investigation, S.M. and J.Z.; data curation, S.M. and J.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M. and J.Z.; writing—review and editing, S.M. and G.-H.T.; supervision, K.L. and G.-H.T.; project administration, K.L. and G.-H.T.; validation, G.-H.T.; funding acquisition, K.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Guangdong Provincial Education Science Planning Program (Higher Education Special Project), grant number 2025GXJK0420. The APC was funded by the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee of the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts (protocol code 2025GXJK0420, 7 November 2025; approval as part of the research project “Innovative Research on ‘Spatial Intelligence’ Teaching in Environmental Design under the Empowerment of AIGC,” a Higher Education Special Project under the 2025 Guangdong Provincial Education Science Planning Program).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset is available upon request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the experts who participated in interviews and surveys during this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- WHO. Ageing and Health. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Su, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xuan, Y. Linking neighborhood green spaces to loneliness among elderly residents—A path analysis of social capital. Cities 2024, 149, 104952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Li, J.; Cao, L.; Wu, Y.; Zheng, J. The association between different social network types with successful aging among community-dwelling older adults: A chain mediation model. Geriatr. Nurs. 2025, 64, 103383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, D.; Wu, S.; Xiang, L.; Zhang, N. Association of residential environment with depression and anxiety symptoms among older adults in China: A cross-sectional population-based study. Build. Environ. 2024, 257, 111535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Zhao, X.; Wu, M.; Li, Z.; Luo, L.; Yang, C.; Yang, F. Prevalence of depression in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2022, 311, 114511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhi, G.S.; Mann, J.J. Depression. Lancet 2018, 392, 2299–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepers, W.; Gryp, D.; Häussermann, F.; Heylen, L.; Van Regenmortel, T.; De Witte, J. The relation between physical and social neighbourhood characteristics and loneliness. A systematic review. Health Place 2025, 94, 103491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zhang, T.; Liu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Song, Y. How Does Urban Green Space Impact Residents’ Mental Health: A Literature Review of Mediators. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, T. Deciphering the Link Between Mental Health and Green Space in Shenzhen, China: The Mediating Impact of Residents’ Satisfaction. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 561809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampio, T.; Maununaho, K.; Lukka, J.; Tiainen, K.; Jolanki, O. “Nature in the neighborhood”: The importance of greenspaces near older people’s homes. Wellbeing Space Soc. 2025, 9, 100277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyshol, H.; Johansen, R. The association of access to green space with low mental distress and general health in older adults: A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitch, J.; Ball, K.; Rivera, E.; Loh, V.; Deforche, B.; Best, K.; Timperio, A. What entices older adults to parks? Identification of park features that encourage park visitation, physical activity, and social interaction. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 217, 104254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, R.; Wang, Y. Study on thermal comfort of elderly in community parks: An exploration from the perspectives of different activities and ages. Build. Environ. 2023, 246, 111001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Wu, S.; Chen, J.; Pan, C. Predicting geriatric environmental safety perception assessment using LightGBM and SHAP framework. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeroja, P.; Foliente, G.; McCrea, R.; Badland, H.; Pettit, C. The Role of Neighbourhood Social and Built Environments—Including Third Places—In Older Adults’ Social Interactions. Urban Policy Res. 2024, 42, 184–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, J.; van Dillen, S.M.E.; Verheij, R.A.; Groenewegen, P.P. Social contacts as a possible mechanism behind the relation between green space and health. Health Place 2009, 15, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arakawa Martins, B.; Taylor, D.; Barrie, H.; Lange, J.; Sok Fun Kho, K.; Visvanathan, R. Objective and subjective measures of the neighbourhood environment: Associations with frailty levels. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2021, 92, 104257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo, M.; Eloy, S.; Marques, S.; Dias, L. Older people perceptions on the built environment: A scoping review. Appl. Ergon. 2023, 108, 103951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, K.K.-L.; Yung, C.C.-Y.; Tan, Z. Usage and perception of urban green space of older adults in the high-density city of Hong Kong. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 64, 127251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Kwan, M.-P.; Yang, Z.; Kan, Z. Comparing subjective and objective greenspace accessibility: Implications for real greenspace usage among adults. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 96, 128335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tan, P.Y. Associations between Urban Green Spaces and Health are Dependent on the Analytical Scale and How Urban Green Spaces are Measured. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, W.W.Y.; Loo, B.P.Y.; Mahendran, R. Neighbourhood environment and depressive symptoms among the elderly in Hong Kong and Singapore. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2020, 19, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Wu, F.; Shi, Y.; Guo, Y.; Xu, J.; Liang, S.; Huang, Z.; He, G.; Hu, J.; Zhu, Q.; et al. Association of Residential Greenness Exposure with Depression Incidence in Adults 50 Years of Age and Older: Findings from the Cohort Study on Global AGEing and Adult Health (SAGE) in China. Environ. Health Perspect. 2024, 132, 67004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.-Q.; Zhu, B.-W.; Wang, K.; Li, X.-Y.; Xiong, L. Links between cue combinations of physical environments and consumer satisfaction in themed restaurants from a systematic approach–avoidance perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2025, 126, 104055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Yang, D.; Owen, N.; Van Dyck, D. The built environment and mental health among older adults in Dalian: The mediating role of perceived environmental attributes. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 311, 115333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishigaki, M.; Hanazato, M.; Koga, C.; Kondo, K. What Types of Greenspaces Are Associated with Depression in Urban and Rural Older Adults? A Multilevel Cross-Sectional Study from JAGES. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoletto, A.; Toselli, S.; Zijlema, W.; Marquez, S.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Gidlow, C.; Grazuleviciene, R.; Van de Berg, M.; Kruize, H.; Maas, J.; et al. Restoration in mental health after visiting urban green spaces, who is most affected? Comparison between good/poor mental health in four European cities. Environ. Res. 2023, 223, 115397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buffel, T.; Phillipson, C.; Scharf, T. Ageing in urban environments: Developing ‘age-friendly’ cities. Crit. Soc. Policy 2012, 32, 597–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-R.; Hanazato, M.; Koga, C.; Ide, K.; Kondo, K. The association between street connectivity and depression among older Japanese adults: The JAGES longitudinal study. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, G.; Cao, M.; De Vos, J. Exploring walking behaviour and perceived walkability of older adults in London. J. Transp. Health 2024, 37, 101832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luiu, C.; Tight, M. Travel difficulties and barriers during later life: Evidence from the National Travel Survey in England. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021, 91, 102973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, R.; Hunter, R.F.; Cleland, C.; Ferguson, S.; Schipperijn, J.; Peng, Q.; Ellis, G. Built environment influences on park visits for older adults: Insights from a machine learning approach. Cities 2025, 165, 106143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, C.; Timperio, A.; Salmon, J.; Loh, V.; Deforche, B.; Veitch, J. Something for the young and old: A natural experiment to evaluate the impact of park improvements. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 100, 128486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iamtrakul, P.; Chayphong, S.; Gao, W. Assessing spatial disparities and urban facility accessibility in promoting health and well-being. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2024, 25, 101126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.-Y.; Lin, T.-P. Decision tree analysis of thermal comfort in the courtyard of a senior residence in hot and humid climate. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 101, 105165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.E.; Rahman, M.A.; Handley, J.F.; Ennos, A.R. Modelling water stress to urban amenity grass in Manchester UK under climate change and its potential impacts in reducing urban cooling. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xiang, X. Examine the associations between perceived neighborhood conditions, physical activity, and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Place 2021, 67, 102505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehle, U.; Baquero Larriva, M.T.; BaghaiePoor, M.; Büttner, B. How does pedestrian accessibility vary for different people? Development of a Perceived user-specific Accessibility measure for Walking (PAW). Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2024, 189, 104203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, D.M.; Matsunaka, R.; Oba, T. Comparing accessibility and connectivity metrics derived from dedicated pedestrian networks and street networks in the context of Asian cities. Asian Transp. Stud. 2021, 7, 100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravensbergen, L.; Van Liefferinge, M.; Isabella, J.; Merrina, Z.; El-Geneidy, A. Accessibility by public transport for older adults: A systematic review. J. Transp. Geogr. 2022, 103, 103408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nykiforuk, C.I.J.; Glenn, N.M.; Hosler, I.; Craig, H.; Reynard, D.; Molner, B.; Candlish, J.; Lowe, S. Understanding urban accessibility: A community-engaged pilot study of entrance features. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 273, 113775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oram, T.; Baguley, A.J.; Swain, J. Effects of outdoor seating spaces on sociability in public retail environments. J. Public Space 2018, 3, 75–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukmirovic, M.; Gavrilovic, S.; Stojanovic, D. The Improvement of the Comfort of Public Spaces as a Local Initiative in Coping with Climate Change. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, L.; Langemeyer, J.; Cole, H.V.S.; Baró, F. Nature-based climate shelters? Exploring urban green spaces as cooling solutions for older adults in a warming city. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 98, 128408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Feng, T.; Timmermans, H. A path analysis of outdoor comfort in urban public spaces. Build. Environ. 2019, 148, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Arndt, S.; Bravo, F.; Cheung, P.K.; van Doorn, N.; Franceschi, E.; del Río, M.; Livesley, S.J.; Moser-Reischl, A.; Pattnaik, N.; et al. More than a canopy cover metric: Influence of canopy quality, water-use strategies and site climate on urban forest cooling potential. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 248, 105089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataee, S.; Lopes, M.; Relvas, H. Environmental comfort in urban spaces: A systematic literature review and a system dynamics analysis. Urban Clim. 2025, 60, 102340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis, A.; Zienowicz, M.; Kukowska, D.; Zalewska, K.; Iwankowski, P.; Shestak, V. How to light up the night? The impact of city park lighting on visitors’ sense of safety and preferences. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 89, 128124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Song, C.; Pei, T.; Liu, Y.; Ma, T.; Du, Y.; Chen, J.; Fan, Z.; Tang, X.; Peng, Y.; et al. Accessibility to urban parks for elderly residents: Perspectives from mobile phone data. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 191, 103642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, X.; White, M. A study on street walkability for older adults with different mobility abilities combining street view image recognition and deep learning—The case of Chengxianjie Community in Nanjing (China). Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2024, 112, 102151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinger, P.; Mcconaghy, R.; Dreher, B.; James, L.; Fearn, M.; McKenna, T.; Hallissey, M.; Hill, K.D. Recreational Spaces: How Best to Design and Cater for Older People’s Safe Engagement in Physical Activity. J. Popul. Ageing 2025, 18, 525–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, R.; Hunter, R.F.; Cleland, C.; Ellis, G. Physical environmental factors influencing older adults’ park use: A qualitative study. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 65, 127353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottoni, C.A.; Sims-Gould, J.; Winters, M.; Heijnen, M.; McKay, H.A. “Benches become like porches”: Built and social environment influences on older adults’ experiences of mobility and well-being. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 169, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanpanahi, M.; Woolrych, R. Neighborhood Environment, Healthy Aging, and Social Participation Among Ethnic Minority Adults over 50: The Case of the Turkish-Speaking Community in London. Housing and Society. 2023. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/08882746.2022.2060010 (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Sang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Qin, X.; Yan, H.; Wu, R.; Qian, F.; Nan, X.; Shao, F.; Bao, Z. Impacts of street tree canopy coverage on pedestrians’ dynamic thermal perception and walking willingness. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 121, 106196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Feng, X.; Zhao, H.; Xu, X. Study on the elderly’s perception of microclimate and activity time in residential communities. Build. Environ. 2024, 266, 112125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Huang, G.; Hu, B. Exploring the impact of lighting sources on walking behavior in obstructed walkways among older adults. Exp. Gerontol. 2024, 196, 112580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottoni, C.A.; Sims-Gould, J.; Winters, M. Safety perceptions of older adults on an urban greenway: Interplay of the social and built environment. Health Place 2021, 70, 102605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhan, M.; Li, F.; Browning, M.H.; Dong, J.; Zhang, K.; Yuan, S.; İnan, H.E.; McAnirlin, O.; Dagan, D.T.; Maynard, A.; et al. From space to street: A systematic review of the associations between visible greenery and bluespace in street view imagery and mental health. Environ. Res. 2024, 263, 120213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wang, M.; Shan, J.; Liu, X.; Jing, Y.; Zhu, H.; Zheng, G.; Peng, W.; Wang, Y. Association between residential greenness and depression symptoms in Chinese community-dwelling older adults. Environ. Res. 2024, 243, 117869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, S.; Lu, N.; Xiao, C. Perceived neighborhood environment and depressive symptoms among older adults living in Urban China: The mediator role of social capital. Health Soc. Care Community 2021, 30, E1977–E1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Yao, Y. Exploring the Pathways Linking Visual Green Space to Depression in Older Adults in Shanghai, China: Using Street View Data. Aging & Mental Health. 2025. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13607863.2024.2363370 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Tzeng, G.-H.; Shen, K.-Y. New Concepts and Trends of Hybrid Multiple Criteria Decision Making; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, X.-Y.; Zhu, B.-W.; Xiong, L.; Tzeng, G.-H. A data mining approach to explore the causal rules between environmental conditions of neighborhood parks and seniors’ satisfaction. Cities 2025, 162, 105897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslem, S. A novel parsimonious spherical fuzzy analytic hierarchy process for sustainable urban transport solutions. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 128, 107447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.-P.; Dong, J.-Y.; Chen, S.-M. A novel intuitionistic fuzzy best-worst method for group decision making with intuitionistic fuzzy preference relations. Inf. Sci. 2024, 666, 120404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, J. Best-worst multi-criteria decision-making method. Omega 2015, 53, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavana, M.; Mina, H.; Santos-Arteaga, F.J. A general Best-Worst method considering interdependency with application to innovation and technology assessment at NASA. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 154, 113272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KhanMohammadi, E.; Talaie, H.; Azizi, M. A healthcare service quality assessment model using a fuzzy best–worst method with application to hospitals with in-patient services. Healthc. Anal. 2023, 4, 100241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Wan, S.; Chen, S.-M. Fuzzy best-worst method based on triangular fuzzy numbers for multi-criteria decision-making. Inf. Sci. 2021, 547, 1080–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Mi, X.; Yu, Q.; Luo, L. Hospital performance evaluation by a hesitant fuzzy linguistic best worst method with inconsistency repairing. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 657–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, M.; Hashemi-Tabatabaei, M.; Ghahremanloo, M.; Keshavarz-Ghorabaee, M.; Zavadskas, E.K.; Antucheviciene, J. A new fuzzy approach based on BWM and fuzzy preference programming for hospital performance evaluation: A case study. Appl. Soft Comput. 2020, 92, 106279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giachetti, R.E.; Young, R.E. A parametric representation of fuzzy numbers and their arithmetic operators. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1997, 91, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Zhao, H. Fuzzy best-worst multi-criteria decision-making method and its applications. Knowl. Based Syst. 2017, 121, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opricovic, S.; Tzeng, G.-H. Compromise solution by MCDM methods: A comparative analysis of VIKOR and TOPSIS. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2004, 156, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.-I.; Chen, C.-C.; Wang, C.-H. Optimization of multi-response processes using the VIKOR method. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2007, 31, 1049–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.