Abstract

As a pivotal instrument for fostering sustainable development and climate goals, low-carbon city pilot policies (LCCPs) motivate firms to increase environmental investments, thereby harmonizing economic growth with emission reduction. This study employs a difference-in-differences (DID) design to empirically investigate the effects and underlying mechanisms of LCCPs on firms’ environmental investment in China. The results demonstrate that LCCPs lead to a significant increase in corporate environmental investment of approximately 36.5% (with a core coefficient of 0.365, significant at the 1% level) when compared to non-pilot cities. This impact primarily occurs through five channels: technology transformation, environmental regulation compliance, financial support, talent attraction, and policy alignment. Heterogeneity tests further reveal that the effect is stronger for enterprises in the eastern and western regions, non-entrepreneurial boards and non-financial entities, larger firms, and those facing financing constraints and operating in low-industry competitive environments. This study offers evidence for the importance of LCCPs in driving corporate environmental investments, providing valuable policy implications for enhancing regulatory frameworks and fostering green innovation to support carbon neutrality and sustainable economic transitions.

1. Introduction

Since 2006, China has held the position of the world’s largest carbon emitter, facing significant pressure to decouple economic growth from carbon emissions amid rapid industrialization and urbanization [1]. To address this challenge, China has implemented LCCPs aimed at disassociating carbon emissions from economic. This strategy seeks to foster environmentally friendly practices and encourage green, low-carbon advancements in urban settings.

Against the backdrop of evolving global climate governance and China’s pursuit of its “dual carbon” strategy, the National Development and Reform Commission initiated low-carbon development programs. In 2010, 2012, and 2017, China incorporated 6 provinces and 81 cities into its low-carbon pilot initiative. The policy’s core objective is to establish a context-specific environmentally friendly urban development model via pilot demonstrations. Furthermore, it aims to offer a blueprint for the global transition to low-carbon cities. Research indicates that these pilots have significantly reduced urban PM2.5 and carbon intensity, while also fostering green urban development by stimulating digital economic growth [2,3,4]. Additionally, studies show that the low-carbon city pilot policy has promoted urban green innovation and reduced CO2 emissions from urban transportation [5,6]. Serving as a central policy instrument for China’s environmental transformation, the LCCPs have established a sustainable mechanism for the integrated advancement of the “economy-environment-society” triad. Further evidence indicates that the pilot policy for low-carbon cities has significantly promoted high-quality economic development and stable employment, and facilitated the optimization and upgrading of the industrial structure [7]. This framework provides tangible support for achieving the objectives of “carbon peak” and “carbon neutrality”, thereby facilitating sustainable development.

Within the framework of regional carbon neutrality goals, companies, being central figures in urban systems and significant contributors to carbon emissions, are essential for attaining sustainable results [8]. However, Chinese firms’ environmental investment choices exhibit distinct dual externalities [9]. On the one hand, investments in environmental governance generate positive social spillover effects, but the associated benefits often remain external to a firm’s financial accounting. This misalignment creates a fundamental tension between environmental goals and profit-maximizing strategies [10]. On the other hand, expenses linked to environmental adherence may displace resources earmarked for research and development, consequently jeopardizing the firm’s future competitiveness [11].

Given the challenges at hand, there is an immediate necessity to identify policy instruments that can effectively encourage corporate environmental investments. Low-carbon policies, which amalgamate institutional pressures with market-based incentives, show substantial potential in instigating change [12]. It is also noted that government attention can enhance the effect of low-carbon city pilot policies on promoting green total factor productivity, implying that the intensity of policy implementation significantly affects the policy outcomes [13]. Nevertheless, research on how LCCPs affect firms’ environmental investment remains underexplored. Therefore, this study considers the implementation of LCCPs as a quasi-natural experiment and applies a difference-in-differences (DID) design. Our findings reveal that LCCPs significantly raise environmental protection investments. Results show that LCCPs significantly raise environmental protection investments. This paper analyzes the mechanism behind this enhancement from both theoretical and empirical perspectives.

This paper’s marginal contribution lies in three main aspects. Firstly, by adopting a DID design, it connects macro-level policy with micro-level corporate behavior. This approach offers a fresh angle for examining environmental regulation and corporate decision-making processes. Secondly, in terms of theoretical advancement, this paper introduces a framework termed “policy-induced reallocation of resources and investment response”. This framework outlines a five-dimensional pathway for environmental protection investment in low-carbon cities, encompassing technological upgrades, regulatory influences, financial backing, talent attraction, and policy adjustments. The framework provides a theoretical foundation for understanding corporate responses to LCCPs’ incentives. Lastly, this study offers specific policy recommendations to enhance China’s low-carbon city initiatives. By pinpointing five key transmission channels—technological upgrades, regulatory influences, financial support, talent attraction, and policy pressures—it suggests the need for a coordinated approach utilizing various policy tools to boost corporate environmental investments. The results also reveal the significance of tailoring policy designs to specific regions and firms, particularly focusing on larger enterprises, non-financial sectors, and firms facing competitiveness or financing challenges. These tailored strategies are crucial for achieving dual carbon goals and fostering sustainable development.

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Literature Review

2.1.1. Impacts of LCCPs

The literature pertaining to this study primarily examines the impact of low-carbon city pilot programs on urban and enterprise levels. Urban-level studies focus on the effects of pilot city establishment on pollution control and carbon emission performance. Research indicates that LCCPs lead to an average 0.13% reduction in the carbon intensity of pilot cities. This reduction is primarily attributed to enhancements in urban environmental governance, industrial structure optimization, heightened urban innovation [2]. Furthermore, LCCPs have also been identified as effective instruments for fostering green economic expansion, catalyzing urban innovation, and enhancing environmental efficiency [14,15,16]. On the enterprise level, LCCPs serve as a fundamental driver of green technology innovation [17]. Moreover, LCCPs also correlate with improved ESG performance among firms in pilot zones [18], with a more substantial impact observed in sectors and areas with high carbon emission intensity. Additionally, scholars have observed that LCCPs can enhance levels of financialization and spur low-carbon innovation [19,20].

2.1.2. Drivers of Environmental Protection Investment

Another body of literature relevant to this study examines the determinants of firms’ investments in environmental protection, emphasizing how external and internal factors shape such investment decisions. The study of external driving factors primarily involves government, the public, and consumers. Scholars have proposed three hypotheses to interpret how environmental regulation shapes firms’ environmental investment behavior [21]. Political factors also significantly affect green investments through the establishment of facilities and enforcement of environmental protection regulations [22]. Apart from policy considerations, public awareness and consumer behavior are significant factors affecting corporate investments and environmental management [23,24]. On the other hand, the study of internal driving factors focuses on executive characteristics, financial performance, and enterprise innovation. Research indicates that CEO-chair duality may foster controlling shareholders’ opportunism, weakening corporate willingness to pursue environmental investments [24]. Regarding corporate finance, studies support a positive association between environmental expenditures and corporate financial performance [25]. Furthermore, enterprise innovation plays a crucial role in enhancing firms’ environmental investments [26].

The literature most relevant to this study pertains focus on how LCCPs influence corporate environmental consciousness. Firms are pivotal actors in emission reduction and carbon trading [27]. Political incentives can notably enhance corporate carbon reduction efforts by raising environmental regulation costs, thereby fostering environmental awareness among businesses [28]. The existing literature has laid a solid theoretical groundwork for this study by extensively exploring the outcomes of LCCPs and the determinants of environmental investments. However, few have examined how the development of such pilot cities shapes corporate environmental investments and the mechanisms responsible. This study empirically assesses LCCPs’ influence on corporate environmental investments and to elucidate the associated mechanisms. Additionally, this study aims to analyze the policy’s varying impacts. The results are anticipated to offer novel perspectives for maximizing policy benefits, advancing carbon peak, and achieving carbon neutrality.

2.2. Research Hypothesis

2.2.1. Technology Transformation Effect

LCCPs foster corporate environmental investment by establishing a favorable setting for technological progress. Specifically, they support the implementation of clean energy, carbon capture, and digital monitoring technologies by establishing collaborative R&D platforms and demonstration zones [29,30]. These initiatives help reduce the costs and uncertainties associated with adopting green technologies, particularly for companies with limited internal innovation capabilities. At the same time, Additionally, the incorporation of digital technologies within LCCPs, such as real-time energy and emission monitoring, enhances resource efficiency and identifies opportunities for energy conservation. This, in turn, encourages firms to invest in environmentally friendly upgrades [31,32]. Digital transformation can effectively enhance the level of green innovation [33], and the resultant technological knowledge sharing reduces barriers to entry for eco-innovation, expediting the spread and commercialization of sustainable practices across various industries [34]. Furthermore, LCCPs also incentivize enterprises to proactively regard environmental pressures as opportunities in their corporate strategies, expedite the adjustment of production methods and technological transformation, leverage digital technologies to provide solutions for carbon emission reduction, advance enterprise digitalization, and transform traditional business models. In this way, enterprises can not only achieve economic benefits but also create environmental value [35,36].

H1a:

LCCPs drive technological advancement, thereby incentivizing enterprises to increase their environmental investments.

2.2.2. Environmental Regulation Effect

LCCPs drive corporate environmental investment by enhancing regulatory enforcement and compliance obligations. Pilot cities often impose stricter emission standards, mandatory carbon disclosure, and carbon pricing mechanisms, increasing the costs of environmentally harmful practices [37]. These stringent requirements prompt companies to redirect resources towards pollution control and cleaner production to avoid penalties and ensure operational legitimacy. This transition is supported by a combination of incentives and penalties: failure to comply leads to fines and damage to reputation, while proactive adherence can improve brand reputation, market opportunities, and stakeholder relationships [11]. Additionally, LCCPs enhance regulatory transparency through digital monitoring systems, reducing information disparities and facilitating more robust enforcement [38]. More importantly, these policy measures send a consistent and clear regulatory signal to the market, helping to reduce enterprises’ uncertainty about future policy direction and enabling them to plan medium- to long-term green investments earlier and with greater stability. These institutional pressures push companies to internalize environmental impacts, incorporate sustainable practices, and pivot towards circular economy models and low-carbon strategies.

H1b:

LCCPs exert regulatory pressure on firms, prompting increased allocation of resources to environmental investments.

2.2.3. Financial Support Effect

LCCPs directly address corporate financing constraints for environmental investments by facilitating access to green capital. Pilot cities commonly introduce financial instruments like green bonds, carbon trading platforms, and subsidized loans to reduce capital costs for firms engaging in eco-friendly endeavors [39]. At the same time, the Low-Carbon City Pilot Policies (LCCPs) also help stimulate green credit, enable enterprises to establish an external pressure transmission mechanism, activate their internal governance capabilities, incentivize polluting enterprises to launch green investment projects [40], drive high-quality green economic transformation [41], promote the development of the real economy [42]. This impact is more pronounced for small and medium-sized enterprises, which often encounter credit constraints in traditional markets [43]. The mechanism operates through two main channels: firstly, specialized green finance platforms reduce barriers to entry for adopting clean technologies; secondly, the integration of ESG criteria into investment decisions encourages capital flow towards firms with superior environmental performance [44]. By enhancing investor confidence and mitigating capital market obstacles, LCCPs bolster the financial feasibility of sustainable initiatives in the long term, fostering a shift towards sustainability-focused corporate practices.

H1c:

LCCPs enhance access to green financing, thereby prompting firms to allocate more resources to environmental projects.

2.2.4. Talent Agglomeration Effect

LCCPs facilitate corporate environmental investment by improving access to high-quality green human capital. Pilot cities employ various talent attraction strategies, including preferential settlement policies, research funding, and collaborations between universities and industries, to attract professionals specializing in renewable energy, environmental engineering, and sustainability management [45]. This concentration of talent operates through two main mechanisms. Firstly, the arrival of skilled individuals allows companies to hire experts capable of developing and implementing advanced emission-reduction technologies, thus reducing the costs and complexities associated with green innovation [46]. Secondly, the establishment of industry clusters in these pilot cities promotes the exchange of knowledge and mutual learning among firms, expediting the spread of best practices in environmental management [47]. The resulting knowledge-intensive ecosystem enhances firms’ innovation capabilities and promotes the integration of sustainable practices into their operational strategies.

H1d:

LCCPs draw highly skilled professionals in sustainability fields, thereby improving firms’ ability to invest in environmental innovation.

2.2.5. Policy-Driven Effect

LCCPs create an institutional environment marked by heightened environmental expectations, which impose isomorphic pressures on firms to align with emerging low-carbon norms. Utilizing institutional theory, we argue that LCCPs generate two primary forms of pressure: coercive isomorphism stemming from regulatory mandates and monitoring, and normative isomorphism arising from intensified societal scrutiny and evolving stakeholder expectations [48,49]. This institutional transformation modifies the cost–benefit analysis regarding corporate environmental behavior. Firms located in pilot cities encounter escalating demands from regulators, consumers, and investors for concrete climate actions, thereby increasing the perceived legitimacy and compliance costs associated with inaction. To address these institutional risks and maintain sustained legitimacy, firms are compelled to allocate resources toward environmental investments. This response reflects not merely an abstract “strategic necessity” but rather a tangible behavioral adaptation aimed at ensuring operational continuity and social license within a redefined policy landscape.

H1e:

LCCPs amplify coercive and normative institutional pressures on firms, resulting in heightened environmental investment as a legitimizing response.

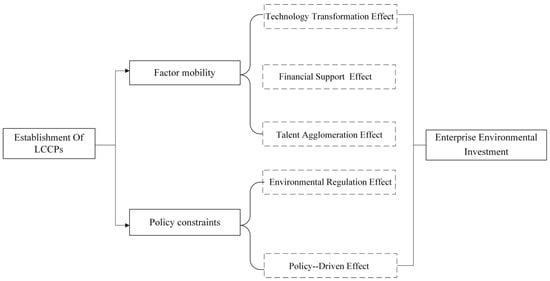

Based on the research hypotheses outlined above, we establish an empirical model, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Theoretical Mechanism. Note: Independently constructed by the authors based on the theoretical analysis in this study.

3. Model Setting and Data Processing

3.1. Empirical Model

Since 2010, China’s low-carbon city pilot initiative has been launched by the National Development and Reform Commission, which has meticulously chosen pilot cities in three phases following the official document “Notice on Carrying out Low-carbon Province and Low-carbon City Pilot Work” and subsequent policies. The selection process involved “local voluntary application, provincial recommendation, and national review and approval,” based on explicit official criteria. First, regional representativeness was prioritized, ensuring the inclusion of cities at various stages of development across the eastern, central, western, and northeastern regions to explore differentiated low-carbon pathways. Second, local readiness and implementation capacity were assessed, with preference given to cities that possessed a solid foundation in energy conservation and emissions reduction, as well as clear planning and potential for policy execution. Third, the potential for demonstration was emphasized, aiming to identify regions capable of developing replicable and scalable experiences in critical areas such as industrial transformation and energy structure adjustment. This non-random, criteria-based selection mechanism, implemented in multiple batches, results in systematic differences between pilot and non-pilot cities prior to policy implementation. Simultaneously, it establishes a multi-period, staggered quasi-natural experimental setting for research. To investigate the effects of these pilots on firms’ investments in environmental protection and the underlying mechanisms, this paper employs data from Chinese listed companies for the 2008–2023 period. Building upon previous research [14,50,51], this model is set as followed:

where and denote firm and year, respectively. denotes firm ’s environmental investment in year . is a dummy variable indicating the pilot of low-carbon cities. is a constant term. represents the impact of the establishment of LCCPs on firms’ environmental protection investment. denotes the control variables; and stand for urban fixed effects and time fixed effects, respectively; and is random disturbance term.

3.2. Variable Description

3.2.1. Explained Variable (EnvInvest)

This paper focuses on environmental protection investment as the dependent variable (denoted as variable ) in the model. For data selection, drawing on existing practices [15,52], projects associated with environmental protection are identified from the construction in progress and management expenses in the annual reports of listed companies to derive relevant environmental investment data. Specifically, the current amount of environmental protection-related items in the notes to the financial statements of annual reports of heavily polluting listed companies is treated as the incremental data for enterprises’ environmental protection investment. A set of 25 project keywords are considered within the construction in progress category. This paper argues that firms’ expenditure on environmental protection reflects their active participation in the environmental governance system and thus should be incorporated into their environmental protection investment.

3.2.2. Explanatory Variable (Treat)

Treatit is the policy dummy variable for the LCCPs, capturing the net policy effect in the DID model. Specifically, if the city where firm i is located implements this policy in year t, Treatit takes a value of 1 for that year and all subsequent years; otherwise, it remains at 0. In cases where a city has multiple policy implementation timelines, the earlier year is adopted for data recording.

3.2.3. Control Variables (X)

To isolate the effect of LCCPs from other confounding influences, a set of control variables is incorporated based on established literature [25,53,54,55] and data availability. These include total asset turnover rate, return on net assets, ownership type, CEO duality, the number of directors, number of employees, secondary agency costs, and the per capita fixed assets of firms.

- (1)

- Total Asset Turnover (ATO): Firms with higher asset turnover generally exhibit stronger operational efficiency, which may enable greater investment in environmentally sustainable practices. In this study, ATO is measured as the ratio of total revenue to total assets.

- (2)

- Return on Equity (ROE): Higher profitability may provide more resources for environmental initiatives. ROE is calculated as net income divided by shareholders’ equity.

- (3)

- Ownership type (SOE): Ownership type is typically represented as a dummy variable, where “1” indicates state ownership and “0” indicates private ownership. State-owned firms are often more closely aligned with governmental environmental policies and may bear greater environmental governance responsibilities. In contrast, non-state-owned firms are typically more influenced by market mechanisms and financial capacities, resulting in more economically motivated environmental investment decisions.

- (4)

- CEO duality (Dual): CEO duality is a binary variable indicating whether the same individual serves as both CEO and board chair (1) or not (0). A dual leadership structure may facilitate greater environmental investment by enabling more centralized and consistent decision-making support for long-term sustainability strategies, free from short-term market pressures.

- (5)

- Board size (Board): Board size is measured by the total number of directors. Larger boards may enhance environmental investment by bringing diverse expertise, including in sustainability, promoting more thorough deliberation and greater accountability in environmental decision-making.

- (6)

- Number of employees (Employ): The number of employees is measured as the total count of employees in the firm. It is positively correlated with corporate environmental investment, as larger workforces can strengthen sustainability culture, increase demand for green initiatives, and heighten regulatory and social pressure, driving greater environmental investment.

- (7)

- Secondary agency costs (AgC2): Secondary agency costs arise from conflicts between managers and external shareholders. These costs are often measured using the variance in executive compensation or other governance-related variables, such as the separation between ownership and control.

- (8)

- The per capita fixed assets of firms (Cap1): Fixed assets per employee is calculated by dividing the firm’s total fixed assets by the number of employees. Firms with higher fixed assets per employee are typically more capital-intensive and may have both greater capacity and stronger incentives to invest in environmental technologies, whether to comply with regulations or to improve operational efficiency.

3.3. Data Source

This study covers the low-carbon pilot provinces and cities announced in 2010, 2012, and 2017. The firm-level data are from annual reports of listed companies, the CSMAR and WIND databases, while city-level data are from the China Urban Statistical Yearbook. Data processing procedure included following steps: (1) removal of samples with abnormal data values; (2) exclusion of firms that were delisted during the sample period; and (3) elimination of enterprise-year observations with missing data on environmental protection investment. Finally, the balanced panel data of 1077 firms for 16 years is obtained, with a total of 13,853 pieces of sample data.

As Table 1 shows, the minimum and maximum values of environmental protection investment are 0 and 28.548, respectively, indicating substantial variation in environmental investment levels across firms. The mean value of the Treat is 0.369, suggesting that approximately 40% of the firms in the sample are located in low-carbon city pilot areas. Thus, the environmental investment of these firms may be influenced to some extent by the policy.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics.

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Baseline Regression Results

As reported in Table 2, the estimated coefficient for the core variable in column (1) is positive and statistically significant at the 1% level, with only city and time fixed effects controlled for. As control variables are added step by step, the coefficient of the core explanatory variable remains significantly positive. The full regression results including all control variables indicate that the coefficient for the low-carbon city pilot policy is 0.365 and statistically significant, suggesting that the establishment of low-carbon pilot cities increases firms’ environmental protection investment. In economic terms, compared with non-pilot cities, the implementation of the low-carbon city initiative leads to a 36.5% increase in firms’ environmental investment. On one hand, low-carbon pilot cities pay more attention to protecting green buildings and the ecological environment. This creates a more livable urban environment [56]. Such an environment helps attract more talent and businesses [17]. This optimizes the regional business environment and boosts agglomeration effects. In turn, local firms increase their environmental investment. On the other hand, these pilot cities develop carbon markets and green financial tools. These tools help turn environmental investments into measurable asset returns. They also strengthen firms’ competitive advantage through a green premium mechanism [39].

Table 2.

Benchmark Regression Results.

4.2. Robustness Test

4.2.1. Parallel Trend Test

The validity of the Difference-in-Differences (DID) estimator rests on the fundamental assumption of parallel trends, which requires that the treatment and control groups follow similar trends prior to the policy intervention. This study employs an event study approach [57] to test this assumption, specifically examining whether corporate environmental investment trends in pilot and non-pilot cities were statistically nonsignificant before the implementation of low-carbon city policies. Drawing on established literature, the following model is specified:

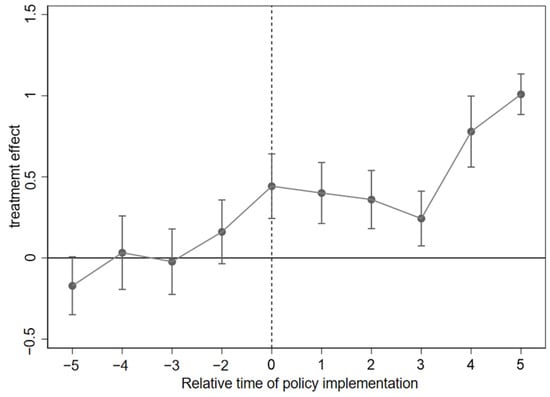

Among these, is a group of dummy variables that equal 1 if a city has adopted the low-carbon pilot policy in year t = k, and 0 otherwise. All other variables align with the definitions in Equation (1). Here, k denotes the number of years relative to the policy implementation. To avoid multicollinearity, the period immediately before the policy (k = −1) is omitted as the benchmark. Accordingly, k takes values from −5 to 5 (i.e., −5, −4, −3, …, 5). Furthermore, following [57], first compute the prior mean, and then take a de-mean approach to the regression coefficients and confidence intervals of all periods to deal with the existing prior trends as much as possible.

Figure 2 displays the parallel trends test results, where dots represent the estimated coefficients, and the short vertical lines indicate the 95% confidence intervals based on standard errors clustered at the city level. The coefficients for pre-treatment periods are statistically insignificant, confirming no significant difference in environmental protection investment between the treatment and control groups prior to the policy. However, the policy effect begins to emerge one year after implementation and remains statistically significant up to five years after the policy’s introduction, supporting the validity of the parallel trends assumption.

Figure 2.

Parallel Trend Assumption Test. Note: Visualized based on the estimation results of regression model (2).

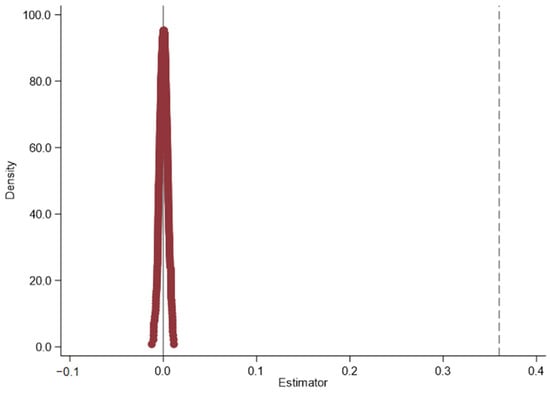

4.2.2. Placebo Test

While quasi-natural experiments have accounted for a range of urban characteristic variables, confounding effects from other policies or random factors may still distort post-policy trend analyses. To address potential biases stemming from such unobserved variables and enhance the robustness of the findings, an indirect placebo test is implemented. In particular, a simulated low-carbon city pilot policy is designed, with random assignments applied to 1077 firms across 500 iterations. Figure 3 plots the resulting distribution of estimated coefficients and their p-values. The results generated during random processing were mainly around zero, significantly different from the estimation coefficient of baseline regression. Most of the p-values exceed 0.1. In contrast, the actual policy estimate is 0.188, which is significantly different from the placebo test results. This suggests that other unobserved random factors and omitted variables are unlikely to have significantly affected firms’ environmental protection investment, thereby supporting the robustness of this conclusion.

Figure 3.

Placebo Test. Note: Independently constructed by the authors based on the research sample data.

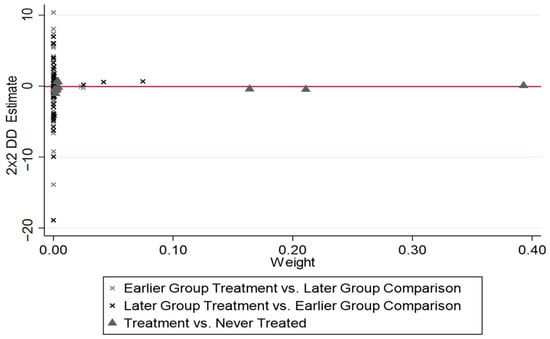

4.2.3. Bacon Decomposition

We use Bacon decomposition to check for possible biases in the difference-in-differences design. Table 3 and Figure 4 show the results. The weight proportion of the time-varying treatment group using the untreated group as the control is as high as 78.7%. In contrast, the weight of “newly treated individuals” using “already treated individuals” as the control is only 14.9%. These results mean there is no big bias in the two-way fixed effects estimates. This supports the robustness of our conclusion. This decomposition directly addresses the potential biases arising from treatment timing heterogeneity in staggered DID designs, including the issue of “forbidden comparisons” where earlier-treated pilot cities are used as controls for later-treated ones. In the context of the LCCPs, the relatively low weight (14.9%) assigned to this potentially problematic comparison category indicates that such comparisons do not dominate our overall treatment effect estimate. Furthermore, the specification of our baseline model, along with the phased implementation of the LCCPs, helps to limit the influence of these comparisons, thereby reinforcing the reliability of our primary DID estimates.

Table 3.

Bacon Result Of Decomposition.

Figure 4.

Bacon Result Of Decomposition. Note: Independently constructed by the authors based on the research sample data.

4.2.4. Winsorization

To mitigate potential bias from outliers in the baseline estimates, the dependent variable was winsorized at the 3% and 5% levels, respectively. The re-estimated results, reported in columns (1) and (2) of Table 4, continue to show a statistically significant positive effect of LCCPs, with the estimated effects corresponding to reductions in the tail areas of 35.8% and 32.2%, respectively, corroborating the robustness of previous conclusion.

Table 4.

Robustness Test.

4.2.5. Controlling for Crisis Effects

To mitigate potential confounding effects from major macroeconomic shocks, we excluded observations from the global financial crisis period (2008) and the COVID-19 pandemic year (2020). The results, presented in columns (3) and (4) of Table 4, remain consistent with our baseline result, with the estimated effects of excluding the epidemic year and the financial crisis year being 36.1% and 29.3%, respectively. This indicates that the core finding of a positive LCCP effect is robust to the exclusion of these major economic disruptions, thereby strengthening the credibility of our main conclusion.

4.2.6. Alleviate Endogenous Problems

To further address potential endogeneity concerns—particularly those related to reverse causality—we implement two additional robustness tests. First, to mitigate potential bias arising from anticipation effects or forward-looking behavior, we follow the instrumental variable approach proposed by [58], In the first stage, employing the one-period lead of the explained variable. The results are in column (6) of Table 4, continues to show a statistically significant positive coefficient for the LCCP variable, with a magnitude closely aligned with our baseline estimate. Specifically, the estimated effect based on the instrumented “variable interpreted in advance” is 32.7%. This suggests that the core finding is unlikely to be driven by reverse causality stemming from such anticipation.

Second, to further reduce the possibility that contemporaneous control variables might be jointly determined with the policy variable, we lag all control variables by one period, a common practice in related studies. As reported in column (7), the coefficient of interest remains positive and significant at the 1% level, and the corresponding effect size for the “Control variable lag” specification is 27.1%, further affirming that the estimated policy effect is robust to this alternative specification. The consistency of results across both approaches, which tackle different potential sources of endogeneity, substantially strengthens the causal interpretation of the positive impact of LCCPs.

4.2.7. PSM-DID Estimation

Considering the possible bias of sample selectivity, this paper employs PSM-DID method to alleviate this problem. Specifically, this paper performs 1:1 nearest-neighbor matching using control variables as covariates. As presented in column (5) of Table 4, the coefficient of the core variable remains positive and statistically significant, with an estimated effect size of 34.1% for the PSM-DID specification, confirming the robustness of this paper’s conclusion.

4.3. Mechanism Analysis

According to the preceding analysis, the model (3) is constructed to further test five potential mechanisms behind the policy’s effect on environmental investment. This model is shown in Formula (3).

4.3.1. Technology Transformation Effect

First, this paper checks if the LCCPs affect firms’ environmental protection investment through the technological transformation effect. We follow the method used in [29], using green invention patents to measure this effect. The results in column (1) of Table 5 prove something important. The coefficient of the core explanatory variable is significantly positive at the 1% level, corresponding to an effect size of 18.9% for the “Green invention patent” mechanism. This means the low-carbon pilot cities help firms do more green innovation. They speed up technological transformation. They also make firms’ environmental investment change from “passive compliance” to “active innovation.” In this way, firms spend more on environmental protection. This result supports Hypothesis 1a.

This significantly positive relationship suggests that the LCCP policy likely ignites firms’ innovation drive by setting clear low-carbon targets, providing demonstration scenarios for R&D, or creating market demand for green technologies. The combination of regulatory pressure and market opportunities incentivizes firms to shift environmental investment from mere end-of-pipe equipment procurement to more strategic innovative activities encompassing cleaner production processes and low-carbon product development. This transition towards “active innovation” implies that environmental investment is no longer solely a cost burden but can become a source of long-term competitive advantage.

4.3.2. Environmental Regulation Effect

Environmental regulation enforcement and market signal incentives are important mechanisms for promoting green investment. Following the practice of [59], this paper chooses the enterprise environmental protection information disclosure to measure. This proxy is employed mainly because it offers consistent and comparable data across different cities and over time. Furthermore, within the framework of the LCCPs, heightened disclosure of environmental information typically signals stronger regulatory pressure and greater public oversight. It thus acts as a tangible and standardized mechanism through which top-down regulatory stringency translates into firm-level behavioral responses. Column (2) of Table 5 reports a significantly positive coefficient for the core variable at the 5% level—indicating an effect size of 236.9% for the ‘Green information disclosure’ mechanism—suggesting that the LCCPs strengthen environmental regulation and thereby increases firms’ environmental protection investment, thus supporting Hypothesis 1b.

The significantly positive coefficient indicates that the LCCP policy likely enhances the transparency and accountability of corporate environmental behavior by strengthening monitoring, enforcement, and establishing unified information disclosure platforms. This increases the compliance risks and reputational costs for firms that neglect environmental investment. Concurrently, publicly disclosed environmental information serves as a basis for decision-making by investors, consumers, and supply chain partners, sending positive green signals to the market. This incentivizes firms to increase environmental investment to project a responsible image and gain market favor.

4.3.3. Financial Support Effect

Financing constraints are a major obstacle for many firms. The LCCPs can ease such constraints via policy backing, financial innovations, and market signals. Based on this, this paper selects enterprise financing constraints to measure by referring to relevant literature [60]. The policy context of LCCPs facilitates access to targeted green capital, primarily by driving green financial development and fostering green technological innovation. As evidenced in related research, this manifests in an increased prevalence of instruments such as green credit (e.g., subsidized loans for energy efficiency), growing availability of green bonds, and preferential financial support for innovation activities, which collectively improve firms’ financial capacity for environmental investment [61]. Column (3) of Table 5 displays a coefficient of 0.126, significant at the 1% level, indicating that the LCCPs alleviate financial limitations for environmentally active firms and spurs green investment, confirming Hypothesis 1c.

The significant coefficient of 0.083 reveals the role of LCCPs in facilitating green financing channels. The pilot policy may lower the financing costs and barriers for green projects by guiding local governments to establish green industry funds, encouraging financial institutions to develop green credit products, or incorporating environmental performance into corporate credit evaluation systems. This particularly assists firms with strong environmental intentions but limited liquidity. Moreover, being included in the pilot program itself may send a positive signal to financial markets regarding a firm’s future potential and compliance, attracting equity investment.

4.3.4. Talent Agglomeration Effect

High-skilled talent is essential for firm development. The enhanced urban living conditions and environmental quality under LCCPs help attract talent, resulting human capital accumulation may encourage greater entrepreneurial investment. Based on this, this paper chooses the high education staff, the technical staff proportion and the total number of staff to measure the talent concentration level. Column (4) of Table 5 presents that explanatory variable is significantly positive at the 1% level, with the corresponding human capital accumulation effects for “Highly educated staff,” “Technical staff,” and “Total number of staff” being 29.8%, 22.2%, and 20.9%, respectively, suggesting that the policy helps attract talent and provides human capital for firm development, thereby stimulating environmental investment. This confirms Hypothesis 1d.

The significantly positive result supports the “talent-driven green investment” pathway. The cleaner air, more livable environment, and stronger green city brand associated with LCCPs exert a powerful pull on highly educated and skilled labor, particularly younger talents who value quality of life and corporate ethos. This talent agglomeration not only directly supplies the knowledge and skills necessary for green technology R&D and managerial innovation but also pressures firms to invest in creating greener, healthier workplaces and fulfilling broader social responsibilities to attract and retain this workforce. This indicates that the positive human capital externality generated by low-carbon city construction ultimately feeds back into and strengthens the green development capabilities of micro-level firms.

4.3.5. Policy Downside Effect

Finally, this paper examines the LCCPs through the policy to influence the firms’ environmental investment mechanism. Drawing on [62], this paper selects firms’ carbon emissions for measurement. The rationale for using carbon emission reduction as a mediating variable is that it represents a direct and measurable outcome of initial policy-induced compliance and low-carbon innovation efforts. This achieved reduction, in turn, can act as a reinforcing mechanism: it signals regulatory compliance, enhances corporate environmental reputation, and may generate cost savings or new market opportunities, thereby justifying and incentivizing further rounds of environmental investment. In this way, emission reduction is conceptualized not merely as a final outcome, but as an intermediate channel that translates policy pressure into a sustained cycle of investment and greener operations. Column (5) of Table 5 shows a significantly positive coefficient—corresponding to an effect size of 15.8% for the “Carbon emissions” mechanism—suggesting that LCCPs effectively lower corporate carbon emissions, promote low-carbon innovation, and further enhance environmental investment of firms. This confirms Hypothesis 1e.

A logically consistent explanation is that the LCCPs impose clear emission reduction pressure on firms through mechanisms like carbon constraints, carbon markets, or efficiency standards. The process of reducing carbon emissions inherently often requires substantial concomitant environmental investment. Alternatively, cost savings from compliance or revenue from carbon trading can be reinvested into other environmental projects. Therefore, the positive coefficient likely reflects the causal chain: “policy pressure–emission reduction action–increased investment.” This demonstrates the direct transmission of the policy’s core objective to firms, creating a binding constraint that drives targeted investment aimed at decarbonization, embodying the policy’s direct effectiveness.

4.3.6. Comparative Analysis of Mechanisms

A comparative of the estimated coefficients in Table 5 offers preliminary insights into the relative strength of the five mechanisms. It is noteworthy that the coefficients for the core policy variable (Treat) in the regressions for the Environmental Regulation Effect (column 2: 2.369) and the Talent Agglomeration Effect (column 4, highly educated staff: 0.298) are among the largest in magnitude and are statistically significant at the 1% level. This suggests that, in terms of the measured response of their respective proxy variables, these two channels exhibit a particularly strong association with the LCCP policy intervention.

From a policy prioritization perspective under resource constraints, these results highlight two potent mechanisms. The strong link with environmental information disclosure indicates that the policy’s effectiveness is closely tied to strengthening regulatory transparency and public scrutiny, which creates potent compliance pressure and market signals for firms. Concurrently, the pronounced talent agglomeration effect underscores the policy’s role in attracting skilled human capital, which is a fundamental driver for long-term green innovation and operational capability.

Table 5.

Mechanism Test.

Table 5.

Mechanism Test.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green Invention Patent | Green Information Disclosure | Enterprise Financing Constraint | Highly Educated Staff | Technical Staff | Total Number | Carbon Emissions | |

| Treat | 0.189 *** | 2.369 ** | 0.126 *** | 0.298 *** | 0.222 *** | 0.209 *** | 0.158 *** |

| (4.996) | (2.413) | (12.098) | (10.937) | (7.995) | (8.686) | (8.674) | |

| ATO | 0.078 *** | −1.097 | −0.023 *** | 0.202 *** | 0.103 *** | 0.171 *** | 0.004 |

| (2.613) | (−1.055) | (−2.801) | (9.145) | (4.561) | (8.775) | (0.199) | |

| ROE | 0.000 | 1.490 | −0.008 *** | 0.256 *** | 0.237 *** | 0.185 *** | −0.202 *** |

| (0.043) | (1.331) | (−2.813) | (7.075) | (6.620) | (5.773) | (−4.886) | |

| SOE | 0.120 *** | 0.982 | −0.031 *** | 0.147 *** | 0.147 *** | 0.124 *** | 0.027 |

| (2.829) | (0.718) | (−2.593) | (5.735) | (5.670) | (5.536) | (1.449) | |

| Dual | 0.042 | 0.203 | −0.001 | 0.002 | 0.036 | −0.042 | 0.015 |

| (1.036) | (0.194) | (−0.111) | (0.061) | (1.112) | (−1.497) | (0.660) | |

| Board | 0.141 | 1.562 | −0.076 *** | 0.947 *** | 0.900 *** | 1.041 *** | −0.176 *** |

| (1.467) | (0.705) | (−3.072) | (16.439) | (15.122) | (20.458) | (−4.181) | |

| AgC2 | −0.806 *** | −24.196 *** | −0.629 *** | −1.247 *** | −1.652 *** | −1.547 *** | 0.883 *** |

| (−2.814) | (−3.426) | (−5.256) | (−3.632) | (−4.631) | (−5.104) | (3.153) | |

| Employ | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | −0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.000 * |

| (7.655) | (3.740) | (−12.753) | (47.197) | (39.531) | (51.438) | (1.776) | |

| Cap1 | 0.249 *** | 3.682 *** | 0.026 *** | −0.157 *** | −0.185 *** | −0.476 *** | 0.136 *** |

| (11.887) | (6.969) | (4.128) | (−12.289) | (−13.817) | (−42.505) | (14.134) | |

| Constant | −3.929 *** | −49.549 *** | 4.128 *** | 6.577 *** | 6.230 *** | 12.125 *** | −1.133 *** |

| (−9.165) | (−4.921) | (36.493) | (28.731) | (26.215) | (60.277) | (−6.573) | |

| Observations | 17,161 | 2901 | 17,156 | 10,400 | 9661 | 10,529 | 12,933 |

| R-squared | 0.356 | 0.373 | 0.384 | 0.354 | 0.363 | 0.482 | 0.037 |

| Firm fe | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Year fe | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

Note: * p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

4.4. Heterogeneity Test

4.4.1. Heterogeneity of Different Geographical Locations

Table 6 indicates that the policy’s positive impact on environmental investment is more evident among firms in the eastern and western regions. With the estimated effects for the West and East being 80.3% and 99.7%, respectively. A possible explanation is that the eastern region benefits from a more developed market environment, stronger technological absorptive capacity, and smoother policy transmission through market mechanisms. The western region, which relies more on a resource-based economy, experiences more direct policy effects through administrative measures. In contrast, the central region’s less pronounced effects may stem from its specific development stage: its green energy infrastructure is often less developed, limiting the immediate scope for firms to adopt low-carbon technologies; simultaneously, local authorities may face stronger pressure to maintain economic growth, which could lead to tempered enthusiasm or flexibility in policy enforcement, creating a “policy transmission buffer.”

Table 6.

Heterogeneity Test 1.

4.4.2. Heterogeneity of Different Stock Sectors

As shown in Table 7, the LCCPs’ effect on environmental protection investment in non-GEM and non-financial firms is better, with the estimated effects for non-GEM and non-financial industry firms being 23.6% and 23.5%, respectively. This may be because GEM firms tend to focus on core technology R&D, resulting in a lower priority placed on environmental protection investment and higher costs associated with green transformation compared to non-GEM firms. For firms belonging to the financial industry, sensitivity to policy uncertainty may lead to a conflict between the long-term benefits of low-carbon transformation and short-term profit objectives, thereby limiting the full realization of policy benefits.

Table 7.

Heterogeneity Test 2.

Furthermore, the non-significant effect for financial firms may also stem from a measurement issue: their “environmental investment” is likely qualitatively different, often taking the form of holdings in green financial products or allocations to sustainable assets, rather than direct investment in physical pollution abatement or energy-saving equipment. Our keyword-based measurement approach, which is more effective at capturing the latter type of investment in operational firms, may thus underrepresent the environmental engagement of financial institutions.

4.4.3. Heterogeneity of Firm Size

The response to LCCPs may vary with firm size. The sample is divided into large and small firms to examine this heterogeneity. Table 8 demonstrates that LCCPs have a stronger effect on stimulating green investment among larger firms, with an estimated effect of 38.4% for large scale firms, while with no significant impact observed for smaller ones. This pattern likely reflects larger firms’ superior resource base, technological capability, and market influence, which allow them to more effectively capitalize on policy incentives for low-carbon transition. The discrepancy likely reflects larger firms’ superior resource base, technological capability, and market influence, which allow them to more effectively capitalize on policy incentives for low-carbon transition. In contrast, small-scale firms often face challenges such as funding shortages and outdated technologies, which weaken the incentivizing effect of the policy. Furthermore, the macro-oriented and industry-level focus of LCCPs may result in policy tools and performance benchmarks that are less accessible or less directly relevant to SMEs, such as high entry thresholds for participation, a mismatch with available small-scale technologies, and insufficient information on tailored compliance pathways. Therefore, when promoting the LCCPs, policymakers are supposed to take into account the differences across firm sizes, especially to provide more policy support for small-scale firms, such as fund subsidies, tax incentives, green financing, etc., so as to improve their enthusiasm for environmental protection investment.

Table 8.

Heterogeneity Test 3.

4.4.4. Heterogeneity of Different Financing Constraints

Table 9 reveals that the policy promotes green investment more strongly among firms with lower financing constraints, with an estimated effect of 32.3% for the “Low Financing” subgroup, while with no significant effect observed for highly constrained firms. This may be because firms with lower financing constraints possess comparative advantages in accessing capital, allowing them to more readily adjust strategies and increase green environmental investment. Even with policy incentives and support, the lack of sufficient financial capacity may hinder their ability to expand environmental investment in the short term.

Table 9.

Heterogeneity Analysis 4.

4.4.5. Heterogeneity of Different Industry Competitive

This paper classifies firms into high- and low-competition groups to assess this heterogeneity. Results in Table 10 indicate that the environmental investment promotion effect of LCCPs for low-industry competitive firms is more significant, with an estimated effect of 43.9% for the “Low Industry Competition” subgroup, while that of high-industry competitive firms is not. This may be because firms in highly competitive industries face greater pressure to maintain short-term profitability, leading them to prioritize investments that improve production efficiency and reduce costs. Consequently, green investment is often perceived as an additional cost burden, thus diminishing the incentivizing effect of the policy. Furthermore, from a resource-based perspective, the positive effect observed in low-competition industries may also reflect the presence of greater organizational slack. Firms operating in less competitive environments are more likely to accumulate discretionary resources in terms of managerial attention, financial reserves, and technical capacity, which can be more readily reallocated to support environmental projects in response to policy incentives, thereby amplifying the policy’s effectiveness.

Table 10.

Heterogeneity Analysis 5.

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

5.1. Main Conclusions

The LCCPs serve as a critical instrument for advancing China’s transition to high-quality, sustainable development. It contributes substantially to reshaping urban energy systems and accelerating the expansion of green industries. This paper initially examines the mechanisms by which the policy affects corporate environmental investment. Secondly, using a difference-in-differences design with policy dummies and panel data from Chinese listed firms (2008–2023), this paper confirms that low-carbon city designation significantly raises firms’ environmental investment. Key results include: (1) The LCCPs elevate firms’ environmental investment by approximately 36.5% relative to non-pilot cities. This finding persists across multiple robustness checks such as parallel trend, placebo, and Bacon decomposition tests. (2) Mechanism tests identify five transmission channels: (a) facilitating technological upgrades to meet green standards (technological transformation effect), (b) strengthening environmental regulations that incentivize compliance-driven investment (environmental regulatory effect), (c) expanding access to green finance and subsidies (financial support effect), (d) attracting high-quality talent to support innovation and implementation (talent aggregation effect), and (e) generating policy pressure that encourages firms to adopt cleaner production practices (policy-induced pressure effect). (3) Heterogeneity analysis reveals significant variation in the impact of the LCCPs. Geographically, the policy demonstrates substantial positive effects in the eastern and western regions, with coefficients of 0.997 and 0.803, respectively, while its impact in the central region lacks statistical significance. Concerning firm type, the policy exerts a more pronounced influence on non-GEM listed firms and non-financial firms, with coefficients of 0.236 and 0.235, respectively, while GEM-listed firms and financial firms do not show any significant effects. In relation to firm size, large-scale enterprises respond positively and significantly, with a coefficient of 0.384, whereas small-scale firms exhibit no significant response. Regarding financing conditions, firms with low financing constraints experience a notable increase in environmental investment, as indicated by a coefficient of 0.323, while highly constrained firms do not show any significant change. Considering industry competition, the policy has a significant effect in low-competition sectors, with a coefficient of 0.439, but remains insignificant in highly competitive environments. These results collectively suggest that the effectiveness of the LCCPs is significantly influenced by regional characteristics, firm-specific attributes, and market structure.

5.2. Policy Implications and Recommendations

Based on the above conclusions, the following policy implications and concrete recommendations are proposed.

- (1)

- Deepen the development of LCCPs and enhance their demonstrative role

Functioning as a pivotal mechanism for high-quality sustainable development, the LCCPs have proven effective in advancing urban energy transitions and green sectors. Future efforts should prioritize its reinforcement with specific instruments. We recommend establishing dedicated R&D and demonstration projects in green technology and clean energy, supported by matching grants and commercialization bonuses. Successful practices from pilots should be systematized into replicable “policy toolkits” for nationwide dissemination. To accelerate innovation diffusion, public–private partnership (PPP) green technology incubators and regional green technology fairs should be promoted. The government should enhance support for low-carbon technology enterprises through intellectual property-backed financing and subsidies for technology transfer and scaling, ensuring green solutions are embedded across industrial chains.

- (2)

- Account for regional disparities and adopt tailored policy measures

Policy measures must be differentiated. Eastern regions, with their stronger economic and technological foundations, should be encouraged to act as pioneers in high-end innovation. Pragmatic steps include: leveraging and expanding existing national key laboratories and research centers in key cities to focus on green technology breakthroughs, and further increasing the R&D expense super-deduction ratio for certified green technology enterprises within the current tax incentive framework. For central and western regions, policy support should focus on addressing local constraints and leveraging comparative advantages. Recommendations include: optimizing the allocation of existing central fiscal transfer payments to prioritize green infrastructure projects, such as clean heating system retrofits and public transportation electrification; providing guided land-use planning and differentiated electricity pricing policies to lower the entry and operational costs for green industries; and actively exploring and piloting cross-regional ecological compensation mechanisms to foster synergistic development between regions.

- (3)

- Strengthen financial support and alleviate financing constraints

To effectively overcome financing barriers and catalyze green investment, policymakers should prioritize the design and implementation of a suite of targeted financial instruments aligned with China’s institutional context and stage of market development. A viable strategy entails refining and scaling existing policy mechanisms.

Specifically, the creation of dedicated green loan guarantee facilities under the national green development finance framework could offer interest subsidies and risk mitigation for low-carbon projects, thus reducing their cost of capital. Concurrently, monetary policy could be further harnessed by expanding and deepening the application of existing carbon reduction financing tools, thereby incentivizing financial institutions to increase concessional lending for green initiatives. Additionally, pilot programs for innovative finance products—such as sustainability-linked loans with pricing tied to verifiable carbon performance targets—should be promoted within designated green finance reform pilot zones. To underpin the efficacy of these instruments, it is crucial to progressively institutionalize mandatory and standardized environmental disclosure for key enterprises and to foster the regulated development of green asset securitization.

- (4)

- Promote green technology transformation and enhance talent cultivation

To foster the adoption of green technologies and build a robust talent base, a coordinated set of concrete policy instruments, aligned with China’s development context, is essential.

A practical step would be the establishment and regular updating of a “National Low-Carbon Technology Promotion Catalogue.” Firms that invest in or deploy technologies listed in this catalogue should be eligible for accelerated depreciation on relevant assets or targeted investment tax credits, directly lowering the cost of technological upgrading. Complementing this, a unified national green technology certification and labeling system should be implemented to provide clear market signals and guide enterprises in enhancing the environmental performance of their products and services. In parallel, addressing the human capital gap requires specific initiatives. This could include launching a dedicated green talent track within existing national high-level talent programs, offering relocation support, housing subsidies, and personal income tax benefits to attract top-tier experts and engineers in green innovation. Furthermore, deepening industry-education integration is key. The government can provide matching grants and tax incentives to encourage leading enterprises and vocational colleges to jointly establish training bases, co-develop curricula, and cultivate a pipeline of technicians and managers equipped with practical skills for the low-carbon transition.

- (5)

- Strengthen policy publicity and public participation to promote green transformation Awareness

To effectively enhance policy outreach and public participation in low-carbon transitions, concrete and participatory instruments should be adopted. It is recommended to integrate low-carbon literacy into national education frameworks and support practical initiatives such as “Low-Carbon Campus” and “Green Community” programs. At the municipal level, government-facilitated “carbon inclusive” digital platforms could be introduced to incentivize green behaviors—including low-carbon commuting and waste sorting—through redeemable points exchangeable for public transport discounts or utility bill reductions. Furthermore, institutionalized engagement mechanisms such as annual “Low-Carbon City Action Weeks” and corporate environmental open days should be established to foster sustained dialog among citizens, businesses, and local governments. These targeted measures can translate policy objectives into tangible public actions, thereby strengthening the social foundation for a sustainable transition.

- (6)

- Build a Targeted and Efficient Financial Support System for Low-Carbon Cities

To address the “insufficiently targeted design” and “limited accessibility” of financial mechanisms in low-carbon city pilots, a systematic policy framework is essential. The core is establishing a closed-loop system covering product innovation, implementation, foundational support, and risk management.

First, promote targeted financial innovations like “carbon reduction-linked loans” tied to corporate emission performance, and expand eligible collateral to include carbon emission rights and forestry carbon sinks. Diversifying financing channels through green and transition bonds is also crucial.

Second, optimize implementation by having local governments build dynamic “green low-carbon” and “transition project databases” to reduce information asymmetry. Regular government-bank-enterprise matchmaking and leveraging central bank policy tools can lower funding costs.

Third, establish a unified regional carbon accounting system and corporate “carbon accounts,” mandating environmental disclosure for key firms. Developing integrated digital platforms will enhance financing efficiency and transparency.

Finally, mitigate risks via green finance compensation funds and guarantees. Prudently explore carbon derivatives and regional carbon inclusion markets to improve liquidity and price discovery, fostering a sustainable finance-transition cycle.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations that also point to valuable avenues for future research. A primary limitation is that the findings are inherently specific to the institutional and economic context of China and its listed firms. Therefore, the direct generalizability of the results to other settings cannot be assumed. Future research should test and adapt these findings in other national contexts, particularly in transition economies that share comparable institutional trajectories or development challenges. On a related empirical note, the enterprise data used are limited to Chinese listed firms from 2008 to 2023. Broadening the data sources to include firms of various sizes, ownership types, and regions, both within and beyond China, would help validate the effects of LCCPs. Additionally, while this study examines the scale of corporate environmental investment, it does not evaluate the heterogeneity in investment quality or environmental outcome efficiency. Due to data constraints, our measure captures the monetary amount invested but cannot differentiate, for example, whether capital directed toward technological transformation yields greater environmental returns per unit than investment motivated primarily by regulatory compliance. Examining this distinction would require more granular, project-level data linking specific environmental outputs to their underlying investment drivers. Secondly, this study focuses on corporate environmental investment and has not fully explored potential green investment synergies across different industries. Future work could analyze inter-industry collaboration under such policies, examining whether they facilitate green technology sharing or joint environmental ventures. Finally, while heterogeneity analyses provide initial insights, a more dynamic model accounting for the interaction of financing conditions, market competition, and regional contexts during policy implementation would offer a fuller understanding of corporate decision-making.

Notwithstanding the context-specific nature of the empirical results, the analytical framework established in this study—evaluating policy impact through identified transmission channels and conditioning factors—provides broader theoretical and methodological insights. It offers a structured lens applicable to examining place-based environmental policies in other emerging economies. The fundamental mechanisms are rooted in established theories of firm behavior and exhibit considerable conceptual generalizability. However, the significance and relative strength of each channel are inevitably shaped by distinct institutional and economic structures. For instance, the effectiveness of regulatory and financial channels is contingent upon local governance capacity and market development, while the role of factors like talent and firm size may vary with labor mobility and industrial composition.

Consequently, while the methodology is widely applicable, it requires careful contextualization. Future comparative studies employing this framework could investigate how variations in institutional quality and market maturity—across both emerging and transition economies—shape these policy pathways. Such research would enhance a more nuanced, context-sensitive theory of environmental policy effectiveness for sustainable development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.S. and S.Z.; methodology, X.S.; software, Y.Z.; formal analysis, X.S. and Y.Z.; data curation, Y.W. and M.Q.; writing—original draft, X.S.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z., Z.D. and B.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Gansu Provincial Department of Science and Technology: 25JRZA093; Gansu Provincial Department of Science and Technology: 25JRZA184; Gansu Provincial Department of Education (University Teachers’ Innovation Fund Project): “Strategic Thoughts and Countermeasures for Building a Cultural Powerful Province in Gansu in the New Era” (2024A-077); Department of Education Shandong Province: tsqn202306167.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ritchie, H. Who Has Contributed Most to Global CO2 Emissions? Our World in Data: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, S.; Jin, G.; Tan, K.; Liu, X. Can low-carbon city construction reduce carbon intensity? Empirical evidence from low-carbon city pilot policy in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 332, 117363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Liang, F.; Li, C.; Xiong, W.; Chen, Y.; Xie, F. Does China’s low-carbon city pilot policy promote green development? Evidence from the digital industry. J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Lai, Z.; Liao, N. Evaluating the effect of low-carbon city pilot policy on urban PM2.5: Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 4725–4751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Huang, H.; Jiang, M. Low-carbon City Pilot and Urban Green Innovation: From the Perspective of Ecological Attention. Asian J. Econ. Bus. Account. 2025, 25, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Yuan, C.; Wang, H.; Mao, X.; Ma, N.; Zhao, J.; Guo, Y. Does Low-Carbon Pilot City Policy Reduce Transportation CO2 Emissions? Evidence from China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y. Implementation Effect, Long-Term Mechanisms, and Industrial Upgrading of the Low-Carbon City Pilot Policy: An Empirical Study Based on City-Level Panel Data from China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamingi, N.; Barbados, W.I. Enterprise and Sustainable Development: Role, Challenges and Opportunities. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 2, 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.T.; Chen, W.Y. Foreign direct investment, institutional development, and environmental externalities: Evidence from China. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 135, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, H.; Chen, X. Does environmental regulation promote corporate green investment? Evidence from China’s new environmental protection law. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 12589–12618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Linde, C.V.D. Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, A.Y. Challenges to the development of carbon markets in China. Clim. Policy 2016, 16, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y. Low-carbon city pilot policies, government attention, and green total factor productivity. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 77, 10704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Yi, J.; Dai, S.; Xiong, Y. Can low-carbon city construction facilitate green growth? Evidence from China’s pilot low-carbon city initiative. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 231, 1158–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.; Huang, Y.; Wu, S.; Hu, S. Does “low-carbon city” accelerate urban innovation? Evidence from China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 83, 103954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Xu, X. Can low-carbon city pilot policy improve urban energy-environmental efficiency? Evidence from China. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 2933–2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Song, Z.; Zhou, J.; Sun, H.; Liu, F. Low-carbon transition and green innovation: Evidence from pilot cities in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Li, Z.; Hu, C. Carbon reduction and corporate sustainability: Evidence from low-carbon city pilot policy. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lv, L. The effect of China’s low carbon city pilot policy on corporate financialization. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 54, 103787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G. Can the low-carbon city pilot policy promote firms’ low-carbon innovation: Evidence from China. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e277879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiter, A.M.; Parolini, A.; Winner, H. Environmental regulation and investment: Evidence from European industry data. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 759–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chițimiea, A.; Minciu, M.; Manta, A.; Ciocoiu, C.N.; Veith, C. The drivers of green investment: A bibliometric and systematic review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madero, V.; Morris, N. Public participation mechanisms and sustainable policy-making: A case study analysis of Mexico City’s Plan Verde. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2016, 59, 1728–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Wang, Z.; Lu, F. The influence of corporate governance and operating characteristics on corporate environmental investment: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabbir, M.S.; Wisdom, O. The relationship between corporate social responsibility, environmental investments and financial performance: Evidence from manufacturing companies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 39946–39957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Pan, C.; Xue, R.; Yang, X.-T.; Wang, C.; Ji, X.-Z.; Shan, Y.-L. Corporate innovation and environmental investment: The moderating role of institutional environment. Adv. Clim. Chang. Res. 2020, 11, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Yang, C.; Zhao, D.; Shao, Y. The Impact of Low-Carbon City Pilot Policy on Corporate Environmental Performance: Evidence from China. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2024, 2024, 7212914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Lai, X.; Tang, X.; Li, Y. Does environmental regulation affect corporate environmental awareness? A quasi-natural experiment based on low-carbon city pilot policy. Econ. Anal. Policy 2024, 84, 1164–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Z.; Shi, L.; Tan, J. The impact of low-carbon pilot city policy on corporate green technology innovation in a sustainable development context—Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Liu, T.; Qi, Y. Policy innovation in low carbon pilot cities: Lessons learned from China. Urban Clim. 2021, 39, 100936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Lin, Y.; Lv, N.; Zhang, W.; Sun, Y. Can government low-carbon regulation stimulate urban green innovation? Quasi-experimental evidence from China’s low-carbon city pilot policy. Appl. Econ. 2022, 54, 6559–6579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyanska, A.; Pazynich, Y.; Mykhailyshyn, K.; Babets, D.; Toś, P. Aspects of energy efficiency management for rational energy resource utilization. Rud.-Geološko-Naft. Zb. 2024, 39, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Shang, Y.; Liu, L. Green image, digital transformation, and corporate green innovation. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2025, 106, 104518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Akcigit, U.; Hanley, D.; Kerr, W. Transition to clean technology. J. Political Econ. 2016, 124, 52–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Jiang, F.; Yang, L. Does digital dividend matter in China’s green low-carbon development: Environmental impact assessment of the big data comprehensive pilot zones policy. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 101, 107143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, L.; An, H.; Peng, L.; Zhou, H.; Hu, F. Has China’s low-carbon strategy pushed forward the digital transformation of manufacturing enterprises? Evidence from the low-carbon city pilot policy. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 102, 107184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y. Impact of environmental regulation policy on environmental regulation level: A quasi-natural experiment based on carbon emission trading pilot. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 23602–23615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Lu, F.; Xu, J.; Chen, K.; Zhao, X. Effect of carbon information disclosure with consistent evaluation standards: An empirical study about carbon efficiency label in Huzhou China. Energy Policy 2023, 181, 113717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Hua, G.; Huo, B.; Randhawa, A.; Li, Z. Pilot policies for low-carbon cities in China: A study of the impact on green finance development and energy carbon efficiency. Clim. Policy 2025, 25, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Gao, W.; Lee, C.C. Does China’s green credit interest subsidies policy promote enterprises’ green technology innovation quality? Based on the perspective of financial and fiscal coordination. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 390, 126366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J. Greening through finance? Based on the dual perspective of external constraints and internal governance. China Econ. Rev. 2025, 91, 102414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Yuan, X. Does green credit promote real economic development? Dual empirical evidence of scale and efficiency. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0326961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Zeng, S.; Chen, H.; Shi, J.J. When does it pay to be good? A meta-analysis of the relationship between green innovation and financial performance. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2021, 70, 3260–3270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, M.; Geyer-Klingeberg, J.; Rathgeber, A.W. It is merely a matter of time: A meta-analysis of the causality between environmental performance and financial performance. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Toh, M.Y. Impact of innovative city pilot policy on industrial structure Upgrading in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]