Abstract

This study addresses the lack of transparent methods for calculating the energy requirements of pulsed electric field (PEF) pretreatments in biogas research. Two detailed approaches are proposed and evaluated to quantify the energy consumed during the pretreatment of lignocellulosic harvest residues (corn, soybean, and sunflower) using a low-frequency electric field. The first approach is based on previously measured capacitor parameters, including resistance (Rs, Rp), inductance (Ls), capacitance (Cp), and loss factor (D), which were interpolated to 50 Hz from measurements performed over the frequency range of 100 Hz to 10 kHz. The second approach relies on direct measurements of the effective voltage and current waveforms across the capacitor, followed by calculation of the power factor (cos φ). Both methods enable reliable estimation of energy consumption and differ primarily in the type of input data required: Method 1 is based on capacitor characteristics determined before and after pretreatment, while Method 2 uses real-time treatment data. Despite these differences, the two approaches yielded highly consistent results, confirming their robustness and applicability. The calculated energy values were subsequently incorporated into a net energy balance by comparing the energy consumed during pretreatment with the methane energy output from anaerobic digestion. For all three investigated lignocellulosic substrates, PEF pretreatment resulted in a positive energy balance under the applied process conditions.

1. Introduction

Increasing demands for smarter, more sustainable energy production across all sectors of modern society are driving the development and utilization of more powerful and energy-efficient technologies for converting biomass into energy [1]. Over the past two decades, scientists worldwide have been developing various renewable energy technologies. One such technology is anaerobic digestion, in which bacteria break down organic compounds in an oxygen-free environment to produce biogas, a gaseous mixture mainly composed of methane. Compared to other biofuels, biogas production is highly flexible with respect to substrates, provided that they are degradable. A wide range of biomass feedstocks, particularly wastes and residues from agriculture, forestry, municipalities, and industry, can be converted into biogas through anaerobic digestion [2,3]. Lignocellulose biomass holds great potential for bioenergy production and is abundantly available. However, due to its complex chemical structure, it cannot be easily converted into biogas. Therefore, a pretreatment step is essential for efficient utilization in anaerobic digestion [4]. The pulsed electric field (PEF), also referred to as electroporation or electropermeabilization, is a promising physical method first described by [5]. It is based on the transient increase in biomembrane permeability when short electric impulses are applied. PEF is typically used to facilitate the transport of various molecules across cell membranes [6,7,8]. More recently, it has been tested and successfully applied in clinical trials for gene transfer, gene therapy, and oncology treatments [9,10,11]. Furthermore, PEF technology is a commercially established tool in the food industry, where it reduces solvent usage, heating steps, and extraction time, while providing high efficiency and better product quality due to its low-temperature applications [12]. Large-scale PEF pretreatment devices consist of one or several pulse generators electrically connected to an electrode system that continuously treats a material flow for a short duration [13,14].

Among many emerging technologies in the renewable energy sector, PEF has shown significant potential. It can be applied to both liquid and solid materials, but to date, studies on liquids have been much more extensive. However, it has not yet been widely adopted in commercial applications. The first studies investigating PEF applications in biogas production appeared in the early 21st century. These studies focused on the release of dissolved organic carbon, chemical oxygen demand (COD) uptake, and the conversion of solids from biological sludges, such as wastewater and manure, into more bioavailable forms [1,15,16,17,18,19,20,21].

Besides liquids, solid sources such as lignocellulosic biomass from agriculture, the wood industry, municipalities, households, and other sectors can be pretreated with PEF. Lignocellulosic biomass has a high potential for biogas production and can be a promising alternative to fossil fuels. Unlike liquids, lignocellulosic biomass is difficult to degrade due to its complex, recalcitrant structure, and therefore, pretreatment is necessary before anaerobic digestion [4]. PEF treatment has been linked to a reduction in the lignin content of lignocellulosic biomass, which enhances the bioavailability of energy-rich structural components, such as cellulose and hemicellulose [13,22]. Several laboratory-scale studies have demonstrated promising results in reducing the rigidity of lignocellulosic biomass, thereby leading to higher biogas yields. Plume and Dubrovskis [23] applied a low-voltage electric field (0.49 V and 0.75 V) to wheat straw and subsequently co-digested it anaerobically with cow manure. The results indicated a 17% increase in methane production in bioreactors with wheat straw pretreated with PEF at 0.75 V compared to bioreactors with untreated wheat straw. The average methane yield from wheat straw during post-fermentation was 17% higher in bioreactors equipped with electrodes operating at a DC voltage of 0.75 V than in bioreactors without electrodes. Additionally, the overall energy balance of the process was positive, since the surplus methane energy generated during anaerobic fermentation was approximately five times greater than the electrical energy used for pretreatment. Lindmark et al. [24] pretreated ley-crop silage with PEF (48 and 96 kV cm−1) under different settings. The results showed that biogas yield increased by up to 16% when the substrate is pretreated at a field strength of 96 kV cm−1 with 65 pulses. No treatment effects were observed at a field strength of 48 kV cm−1 with 100 pulses. The energy balance indicated that methane production could be approximately double the electrical energy input of the process. El Achkar et al. [25] pretreated grape pomace with PEF of 3.6 kV cm−1, varying the pulse frequency and duration, and then measured the biochemical methane potential of the pretreated substrate, which showed a 4% increase in cumulative methane yield compared to the untreated substrate. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that PEF pretreatment offers clear sustainability benefits, as it enables process intensification while potentially reducing thermal energy demand and chemical inputs, and enhances substrate biodegradability and bioavailability for subsequent biological conversion.

In addition to these studies, several authors have considered the specific energy input and net energy balance of PEF pretreatments and subsequent anaerobic digestion. Szwarc et al. [26] compared PEF and ultrasonication as pretreatments for chicken manure with a high straw proportion. Both methods enhanced biogas and methane yields, but their energy balance calculations revealed that only one PEF treatment series achieved a net positive balance, while all other series were energetically unfavorable. No detailed calculation procedure was provided. The energy assessment was limited to two simplified equations: one estimating the additional methane energy output associated with an increase in Biochemical Methane Potential (BMP), and another expressing the net energy balance as the difference between energy output and input. However, energy analysis was not the primary focus of their study. Raso et al. [27] published recommendations for reporting key information in PEF studies, emphasizing the importance of standardized reporting of pretreatment parameters to improve comparability among studies. Their guidelines also included basic formulas for calculating the specific energy input, which serve as a reference framework for subsequent research.

Optimization of PEF pretreatment primarily focuses on cost-effectiveness, which can be achieved by increasing biogas or methane yields relative to the energy input, reducing hydraulic retention time, and improving the characteristics of the final biosolids after digestion. Usually, the results of PEF pretreatment show a nonlinear relationship between the pretreatment parameters and the increase in biogas yield. Therefore, optimization is particularly challenging, as multiple variables interact and often lead to highly variable outcomes. Pretreatment protocols, therefore, need to be carefully tailored to both the substrate and the digester configuration.

However, many studies still fail to report the complete set of PEF pretreatment parameters or to provide a clear description of the applied protocol. This lack of standardized reporting hinders reproducibility and makes cross-study comparisons difficult. To ensure continuous progress, detailed and consistent reporting of all pretreatment parameters is required [13,27]. To address this gap, the present study introduces a transparent and detailed methodology for calculating the specific energy input of PEF pretreatment applied to lignocellulosic substrates. The contribution of this work is twofold: first, it provides a reproducible framework for quantifying the energy requirements of PEF; and second, it applies this framework to evaluate the effects of PEF pretreatment on biogas and methane yields through anaerobic digestion experiments. By enabling a transparent and accurate assessment of energy demand, the proposed methodology supports energy-efficient optimization of PEF pretreatment and contributes to the development and more sustainable design and evaluation of biogas production systems.

2. Materials and Methods

Pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass with an electric field is performed by placing the biomass between two copper (Cu) plates of a capacitor and applying a voltage to the plates, thereby generating an electric field in the region occupied by the biomass. Consequently, the analysis and calculation of energy consumption can be reduced to determining the energy dissipated in the capacitor, depending on the type of excitation and the capacitor parameters. To this end, different equivalent capacitor models can be applied, with a simplified equivalent model being the most commonly used. It should be emphasized that the model can be adapted for different frequency ranges (DC and AC) to accurately reflect the behavior of the real capacitor in terms of power dissipation. In this paper, the model is adapted for two basic operating modes—DC excitation (direct voltage applied at the capacitor terminals) and AC excitation (alternating voltage at 50 Hz), since both types of voltage may occur at the capacitor terminals and thus influence the resulting electric field.

2.1. Equivalent Simplified Capacitor Model

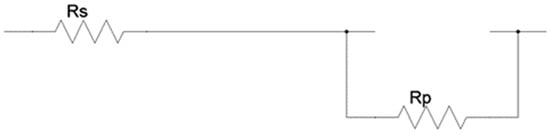

A detailed procedure for determining the energy consumed during PEF pretreatment of the lignocellulosic substrate, using the measured parameters of the parallel-plate capacitor (Figure 1), is presented below.

Figure 1.

Plate capacitor used for the PEF pretreatment.

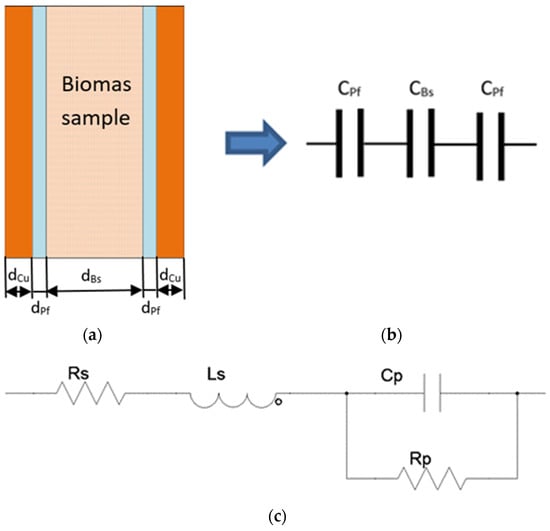

The substrate (dBs) is placed between the Cu plates (dCu) during pretreatment, while being galvanically isolated from the plates. A plastic foil (dpf) acts as an insulator (Figure 2a). The equivalent capacitor circuits used for pretreatment are shown in Figure 2b,c.

Figure 2.

(a) Plate capacitor of the system used for PEF pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass; (b) equivalent circuit of series-connected capacitors; (c) equivalent circuit (model) of the total capacitor CT (Ls—equivalent series inductance of the capacitor; Cp—equivalent parallel capacitance).

The real capacitor element C is represented by the most appropriate equivalent circuit. In such modeling, discrete components (R, L, and C) are introduced to account for the resistances, inductances, and capacitances present in a real capacitor. The focus of this paper is on determining the energy consumed during the operation of such a capacitor under PEF conditions, which corresponds to the active power. To this end, a simplified equivalent capacitor model is applied, containing the elements Rs and Rp, where active power losses (dissipated power) occur.

The simplified capacitor model, which generally incorporates distributed parameters, can be applied to both low- and high-frequency analyses. Losses in the dielectric (dielectric absorption) are represented by the resistor Rp, while losses in the conductive part of the capacitor are represented by the resistor Rs. The dielectric consists of the lignocellulosic biomass sample and the plastic insulation in which the biomass is embedded. The series inductance Ls represents the inductive component, which largely depends on the capacitor construction.

The measurement range for all model parameters (Rs, Ls, Cp, and Rp) was 100 Hz to 10 kHz. The values at the operating frequency of 50 Hz were obtained by fitting a smooth curve to the measured data and interpolating at 50 Hz. This base frequency (50 Hz) was applied for both treatments. The measured parameter values were then used to determine the electrical energy consumed during PEF pretreatment.

Finally, the measured values beyond the treatment frequency considered in this study (above 50 Hz) can be used to estimate energy consumption during lignocellulosic substrate pretreatment with higher frequency electric fields (100 Hz to 100 kHz), which will be addressed in future research.

2.2. Electric Field Pretreatment

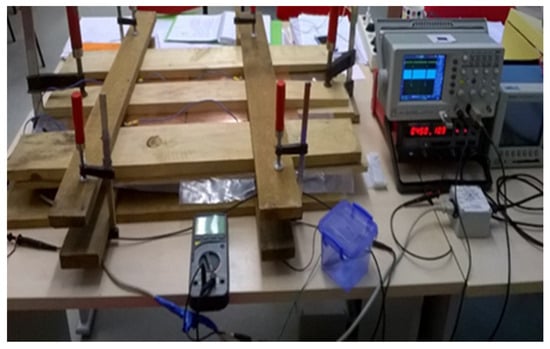

Pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass using PEF to enhance biogas production was carried out using two different approaches. Details of the substrate preparation (drying and comminution), pretreatment procedures, corresponding experimental schemes, and the outcomes of the subsequent anaerobic co-digestion of pretreated substrates with manure have been described in detail in a previously published paper [28]. The experimental setup, including the capacitor, diode–switch drive system, and measurement instruments, is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Capacitor with a diode–switch drive system and measurement setup (oscilloscope and multimeters) used for PEF pretreatment of lignocellulosic substrates.

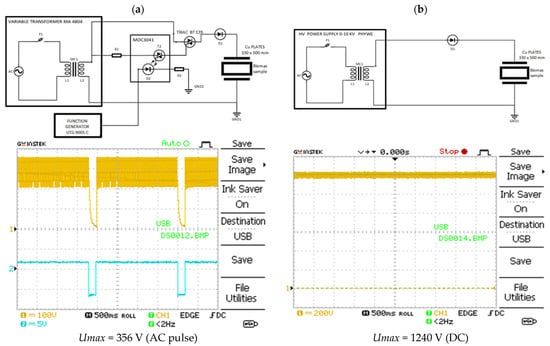

The voltages were applied to two parallel Cu plates used for electric field pretreatment. The pretreatment duration for lignocellulosic samples ranged from 10 to 30 min in Method 1 and from 3 to 30 s in Method 2. In both methods, the treatment duration, peak excitation voltage, and interruption frequency are key parameters for process optimization and will be investigated in future research. The first pretreatment model (Figure 4a) used a homogeneous DC electric field generated by rectified AC voltage (50 Hz), periodically interrupted by an electronic switch at 452 mHz. In this way, a PEF was generated, consisting of DC pulses with a 50 Hz ripple (AC component). The peak voltage reached 356 V (yellow waveform 1). The blue waveform (2) represents the function generator signal controlling the electronic switch. The second pretreatment model (Figure 4b) applied a 1.2 kV DC voltage with a 40 V ripple (50 Hz), resulting in a peak voltage of 1.24 kV at the plate capacitor. The yellow waveform was generated using a high-voltage power supply (0–10 kV, PHYWE) and a high-voltage diode (D1). The ripple represents the 50 Hz AC component supplied by the generator alongside the DC output.

Figure 4.

(a) Electrical schematic of the PEF (DC + AC) pretreatment system [28]; (b) Electrical schematic of the high-voltage DC electric field system.

The block diagram of the PEF pretreatment system is shown in Figure 4. The AC voltage source is a variable transformer MA 4804 (Metrel, Horjul, Slovenia), whose output is supplied to an optoelectronic switch based on the MOC 3041 optocoupler (ON Semiconductor, Phoenix, AZ, USA) and the BT 139 triac (NXP Semiconductors, Eindhoven, Netherlands). In series with the output to the treatment plates is a diode D1 (PD 332), which provides a DC signal to the plates. The optocoupler is controlled using a UTG 9005C function generator (UNI-T, Shenzhen, China), which delivers a digital signal at a frequency of 452 mHz with voltage levels of 0 and 10 V, thereby interrupting the voltage supply to the treatment plates. The block diagram of the DC electric field pretreatment system is shown in Figure 4. The field source is a high-voltage power supply (0–10 kV, PHYWE, Göttingen, Germany), whose output is connected to a PN diode (D1) that serves as a rectifier. In series with the diode are two Cu plates, between which the substrate is placed for pretreatment.

2.3. Electric Field Energy Calculations

2.3.1. Equivalent Schemes for Different Operating Regimes

The equivalent capacitor circuit for substrate pretreatment is applied based on the frequency range of capacitor excitation, as shown in Figure 2c. The capacitor used for pretreating lignocellulosic substrates is excited by an electric field generated by two voltage waveforms, each containing both AC and DC components.

- (I)

- AC mode

The equivalent circuit in this operating regime is identical to the basic capacitor circuit shown in Figure 2c. Both equivalent resistances, Rs and Rp, are crucial for determining the active power dissipation and are not neglected in this mode.

In the AC operating mode, it is necessary to compare the absolute values of the component impedances at the operating frequency (50 Hz). The impedance of the series inductance is given by Equation (1). If some impedances have negligible values, they may be omitted from the circuit. The relevant impedances in this scheme are:

The series inductance impedance:

where Ls is the series inductance; ZLs is the impedance of the series inductance Ls, and is the circular frequency.

The parallel capacitance impedance is given by Equation (2):

where Cp is the parallel capacitance; ZCp is the impedance of the parallel capacitance Cp, and is the circular frequency.

Since both impedances are significant in this analysis [29], they are not neglected, and the equivalent replacement circuit of the capacitor remains unchanged. Energy dissipation, corresponding to the active power consumption, occurs in the Rs and Rp resistances.

- (II)

- DC mode

In this operating mode, since the signal frequency is zero, all capacitors act as open circuits (ZCp → ∞), while all inductances behave as short circuits (ZLs = 0). The effective resistances remain in the equivalent circuit and are crucial for determining power dissipation. The equivalent circuit corresponding to this mode is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Equivalent scheme of the capacitor under DC operating conditions.

2.3.2. Energy Calculation Methods

To determine the energy consumed during the pretreatment of lignocellulosic substrates with an electric field, two sets of data were used, forming the basis for two calculation methods. The two methods differ primarily in the type of input data and the underlying calculation philosophy, while both quantify the same physical quantity, namely the active electrical energy dissipated in the treatment capacitor. Method 1 is a parameter-based, model-driven approach, in which the consumed energy is determined using an equivalent capacitor model based on previously measured electrical parameters. In contrast, Method 2 is a measurement-based approach, relying on directly measured effective voltage and current during pretreatment, combined with an experimentally determined power factor. Although conceptually different, both methods yielded closely matching results, confirming their consistency and robustness.

In Method 1, the energy calculation is based on the measured electrical parameters of the unloaded capacitor used for pretreatment (RS, LS, Cp, and RP), as well as the recorded voltage waveforms across the capacitor. In Method 2, the calculation is based on the measured effective voltage at the capacitor terminals and the effective current passing through the capacitor. In this approach, the calculation of power (and consequently energy) requires the power factor. This factor was determined in two ways: (a) from the measured current and voltage waveforms across the capacitor (with the current derived from the voltage drop across a 1 Ω resistor connected in series with the capacitor), resulting in values ranging from 0.309 to 0.333; and (b) from the measured capacitor loss factor D, yielding a value of 0.318. As can be observed, these two approaches produce very similar power factor values. A detailed calculation was performed for the pretreatment of finely milled corn substrate at maximum voltages of 356 V and 1240 V. The 356 V waveform was periodically interrupted (modulated), resulting in a pretreatment duration of 2 s with interruption intervals of 0.2 s, whereas the 1240 V waveform was applied continuously without interruptions (Figure 4). Both excitation waveforms contained AC and DC components.

Calculation Method 1

The total electrical energy required for lignocellulosic substrate pretreatment is calculated as the sum of the energy contributions from the alternating and direct components of the PEF. Because energy is defined as power integrated over the pretreatment duration, both alternating and direct power components must be determined first.

- Calculation of alternating power (energy) using an equivalent circuit for AC operation (Figure 2c)

Measurements were performed using an LCR meter, type (UT612, UNI-Trend Technology, Dongguan, China). The measured and interpolated values of the capacitor parameters for fine corn substrate pretreatment are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Measured and interpolated capacitor parameters for fine corn substrate pretreatment.

The parameter values at 50 Hz were obtained by fitting a smooth curve to the measured data and interpolating at 50 Hz, and the interpolated results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Interpolated capacitor parameters at 50 Hz for fine corn substrate pretreatment.

Active power at alternating voltage on the Cu plates of a plate capacitor with losses is consumed in two places: in capacitor Cp (dielectric losses, equivalent resistance Rp) and in the series resistance Rs. According to [29], the dielectric losses of the capacitor can be calculated using Equation (3):

where Uef is the effective value of the alternating voltage on the capacitor (V), ω is the circular frequency, Cp is the equivalent parallel capacity (F), and D is the dielectric loss factor of the capacitor.

Alternatively, the dielectric losses can be calculated using Equation (4):

where Uef is the effective value of the alternating voltage on the capacitor (V), Rp is the equivalent parallel resistor (Ω).

If the power dissipated in the parallel resistance for the waveform voltage (Uef = 55.15 V) shown in Figure 4 is calculated, the following values are obtained: PAC1 = 0.000200304 W and PAC2 = 0.000234268 W, which are very similar.

The AC power dissipated in the series resistance Rs was calculated using Equation (5):

where Iac is the effective value of the alternating current flowing through the series resistance Rs (V), and Rs is the equivalent series resistance (Ω).

The effective current is obtained from the absolute value of the total impedance of the network shown in Figure 2 (Equation (6)):

The total impedance of the network is given by Equation (7):

The absolute value of the total impedance was calculated according to Equation (8):

Since all the values required for the calculation are known, the results are: Iac = 16.84 mA and PAC3 = 0.00035 W.

- B.

- Calculation of DC active power (energy) using an equivalent circuit for DC operation (Figure 5)

The mean value, i.e., the direct current (DC) power, in the equivalent substitute scheme from Figure 5 was calculated using Equation (9):

where UDC is the DC voltage on the capacitor (V), Rp is the equivalent parallel resistance (Ω), and Rs is the equivalent series resistance (Ω).

Since the share of power dissipated in the series resistance represents only 3.7% of the total DC power, it was neglected in further calculations. Accordingly, the DC power was approximated as given by Equation (10):

- (A)

- Calculation of the total dissipated power in the plate capacitor

The total power was determined using two alternative calculation approaches:

(C1) Using the powers PAC1, PAC3, and PDC, the total power was calculated according to Equation (11):

(C2) Alternatively, using the powers PAC2, PAC3, and PDC, the total power was calculated according to Equation (12):

Since the applied voltage is switched off for 10% of the cycle time (0.2 s) and applied for 90% of the time (2 s), the total energy consumption was calculated using Equations (13), which corresponds to an energy value of ≡98.0 Wh t−1, and (14), which corresponds to an energy value of ≡97.5 Wh t−1:

(both expressed as Wh t−1 of substrate mass).

Both procedures give very similar values for the energy required to pretreat the fine corn substrate with a modulated homogeneous AC/DC electric field (Figure 4) at a maximum voltage of 356 V.

For excitation with a peak voltage of 1240 V, the total energy was calculated without applying a multiplication factor of 0.9, because this voltage was applied over the entire treatment duration (Figure 4). During this treatment (peak voltage of 1240 V), the following energy values were obtained: Wtot1 = 1982.2 Wh t−1 and Wtot2 = 1978.5 Wh t−1.

Calculation Method 2

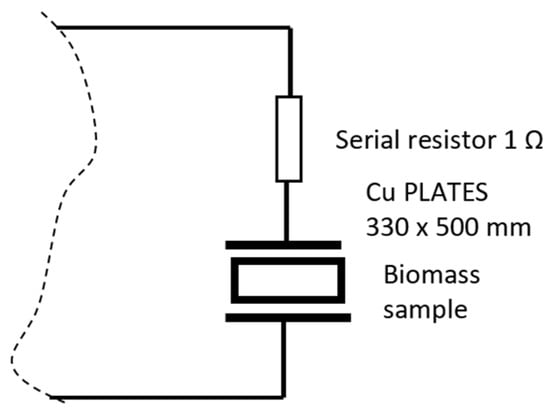

The calculation of the energy consumed during the treatment of the lignocellulosic substrate with an electric field using this method is based on the measurements of the effective voltage and current, as well as the dielectric loss factor of the treatment capacitor. Measurements were performed using the following instruments: an LCR meter (UT612, UNI-T) and a universal measuring device (UT39A, UNI-Trend Technology, Dongguan, China). The power factor cos(φ) can be determined by measuring the voltage waveform across the treatment capacitor and the voltage across a 1 Ω auxiliary series resistor (Figure 6 and Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Segment of the electrical schematic with a 1 Ω auxiliary series resistor.

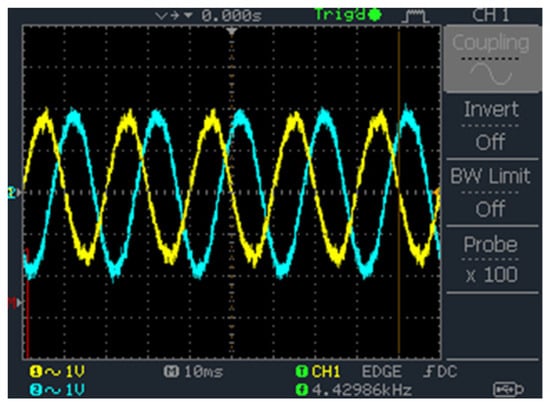

Figure 7.

Voltage waveforms measured at the capacitor (blue) and at the 1 Ω auxiliary series resistor (yellow) at 50 Hz during fine corn substrate pretreatment.

The power factor depends on the phase shift between the voltage and current at the capacitor. To determine this phase shift, the recorded waveforms of the voltage across the series resistor (which represents the current through the capacitor) must be analyzed. However, this requires precise measurements, which depend on the resolution of the recorded signals and accurate signal triggering. The measured current and voltage values obtained at 50 Hz during fine corn substrate pretreatment are summarized in Table 3. This is demonstrated in the following example.

Table 3.

Measured current and voltage values at 50 Hz during fine corn substrate pretreatment (see Figure 7).

By reading the time displacement between the voltage waveforms measured on the capacitor and on the 1 Ω auxiliary series resistor (which is in phase with the current), the power factor at 50 Hz during pretreatment of the fine corn substrate was determined using the following relation (Equation (15)):

where Δt is the time shift between voltage and current waveforms, and T is the signal period (5 ms at 50 Hz).

When determining the power factor, it is crucial to read the phase shift between the capacitor voltage and current (via the series resistor) as accurately as possible. Since the recorded voltage traces are relatively thick and the time-axis resolution is limited, three independent readings (estimates) were performed, yielding three different power factor values. According to the dielectric loss factor (D), a value of 3.18 is obtained. The differences between these values arise from measurement uncertainty, the precision of diagram interpretation, and the effective electrical behavior of the treatment capacitor, which depends on substrate thickness, the degree of filling of the lignocellulosic substrate between the plates, the packing density (how densely the substrate is distributed between the plates), field fringing effects, etc.

- (B)

- Calculation of alternating active power (energy) using the equivalent circuit for AC operation (Figure 2)

The alternating power dissipated during the pretreatment was calculated using the standard relation for alternating power (Equation (16)):

where Uacef is the effective value of the AC voltage on the capacitor (V), Iacef is the effective value of the AC through the capacitor (A), and D is the dielectric loss factor. Substituting the measured values into Equation (16) (with the power factor approximated by the dielectric loss factor, D = 3.18), the following value was obtained:

- (C)

- Calculation of DC power (energy) using measured current and voltage values (Table 2).

The average DC power was calculated from the measured voltage and current values listed in Table 2 using Equation (17):

where Udc is the effective DC voltage on the capacitor (V), and Idc is the effective DC through the capacitor (A).

- (D)

- Calculation of the total active power dissipated in the plate capacitor during lignocellulosic substrate pretreatment

The total active power dissipated in the capacitor was calculated as the sum of the AC and DC power components (Equation (18)):

Since the applied voltage is switched off for 10% of the cycle time (0.2 s) and applied for 90% of the time (2 s), the total energy consumption was calculated using Equation (19):

Expressed per tonne of substrate, the energy consumption obtained using Method 2 was 105.58 Wh t−1, whereas Method 1 yielded a value of 98.0 Wh t−1.

The difference between the two values (8.06%, relative to the lower reference value) is not significant and arises from several factors: (i) interpolation of the dielectric loss factor D at 50 Hz in Method 1; (ii) simplifications of the equivalent capacitor model and omission of certain parameters in Method 1; (iii) the approximate value of the dielectric loss factor D used in Method 2; (iv) measurement uncertainties; (v) variations in electrode spacing due to differences in substrate density; and (vi) inaccuracies in reading waveform data. From the perspective of good engineering practice, the higher energy value obtained using Method 2 was adopted, following the principle of worst-case analysis. The overall precision of the calculated power and energy values is limited by the accuracy of the measuring instruments, the graphical determination of the phase shift between voltage and current, and the simplifications inherent in the equivalent capacitor model. Numerical values are reported as direct outputs of the deterministic calculation procedure to ensure transparency and reproducibility. Extended decimal representations, therefore, reflect computational resolution rather than experimental measurement accuracy. The same procedure was applied to the second waveform (Udc = 1240 V). The final energy consumption values for all lignocellulosic substrates are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Total energy values for lignocellulosic substrate pretreatment using a homogeneous electric field (Method 2, 1 h duration).

3. Results and Discussion

Calculations were carried out for all pretreated substrates (corn, soybean, and sunflower harvest residues) using two types of fields: a DC + AC modulated field with a peak plate voltage of 356 V, and a DC + AC field with a peak plate voltage of 1240 V. Unlike most previous studies, where the energy input of PEF pretreatment is estimated using simplified expressions or reported only as a net energy balance, the present study provides a transparent and physically grounded calculation of electrical power dissipation based on both an equivalent capacitor model and direct voltage–current measurements. The total energy consumed during pretreatment with a homogeneous electric field was determined using Method 2. Table 4 presents the total energy values for all substrates relevant to this study. The overall energy balance of the process (lignocellulosic pretreatment and anaerobic co-digestion of pretreated substrates with manure) was reported in a previously published paper by [28].

The fine fraction includes substrate particles smaller than 1 mm, while the coarse fraction includes particles between 1 and 2 mm in size. Particles larger than 2 mm belong to the largest fraction. If the voltage at the capacitor terminals is divided by the plate spacing, the electric field strength for the voltage ranges (minimum and maximum values of 200–356 V and 1.16–1.24 kV) was determined and is listed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Measured capacitor plate spacing and electric field strength between the plates [30].

If the total energy required for substrate pretreatment over a duration of 1 h is known, the energy consumption for other treatment durations can be calculated using Equation (20):

where k = 3600 for durations expressed in seconds and k = 60 for durations expressed in minutes.

Here, Wtot(s/min) is the total energy required for substrate treatment for the specified duration, Wtot1h is the total energy required for 1 h of treatment, and ts/min is the treatment duration expressed in seconds or minutes.

The net energy balance of the electric field pretreatment was calculated as the difference between the biogas energy output and the electrical energy consumed during pretreatment (Equation (21)):

Wnet = Wbge − Wtot

The primary purpose of determining the total energy consumed in the treatment capacitor is to establish the energy balance (net energy) of the electric field pretreatment as part of the overall biogas production process based on harvest residues and manure. Using the data calculated in this study (Table 5) together with data reported in the literature [30], the energy balance can be determined for different pretreatment scenarios. The following examples illustrate this approach:

- (a)

- Fine fraction of sunflower stalks, treated with an electric field strength of E = 0.90–1.6 kV cm−1, at a voltage of U = 200–356 V and a treatment duration of t = 30 min: Wbge = +15.30 kWh t−1, Wtot = 0.05445 kWh t−1, and Wnet = 15.25 kWh t−1.

- (b)

- Coarse fraction of corn, treated with an electric field strength of E = 0.67–1.19 kV cm−1, at a voltage of U = 200–356 V and a treatment duration of t = 10 min: Wbge = +10.50 kWh t−1, Wtot = 0.00176 kWh t−1, and Wnet = 10.50 kWh t−1.

- (c)

- Fine fraction of soybean straw, treated with an electric field strength of E = 5.71–6.11 kV cm−1, at a voltage of U = 1.16–1.24 kV and a treatment duration of t = 20 s: Wbge = +14.97 kWh t−1, Wtot = 0.01334 kWh t−1, and Wnet = 14.95 kWh t−1.

where Wnet is the net energy obtained from electric field pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass, Wbge is the biogas energy generated from the co-digestion of manure and pretreated lignocellulosic substrate, and Wtot is the total energy consumed during electric field pretreatment.

These examples demonstrate that relatively high net energy values (Wnet) can be achieved either by applying low electric field strengths (0.90–1.60 kV cm−1) with longer pretreatment durations (30 min), or by using high electric field strengths (5.71–6.11 kV cm−1) combined with very short treatment durations (20 s). This suggests that adjusting the electric field strength and exposure time appropriately can yield comparable energy outcomes. This finding highlights the potential for pretreating lignocellulosic substrates using very short pretreatment times at high electric field strengths, which is particularly relevant given that processing time is a key operational parameter in biogas production systems. In practice, such pretreatment could be implemented through an automated process in which the substrate is conveyed through a chamber exposed to a controlled electric field, after which the conventional stages of biogas production proceed.

4. Conclusions

The aim of this study was to establish a transparent and physically grounded procedure for calculating the energy consumption of electric field pretreatment of lignocellulosic harvest residues within the biogas production process. Two independent calculation approaches were developed and evaluated: one based on the equivalent capacitor circuit and the other based on direct measurements of effective voltage, current, and power factor. Both methods proved suitable for estimating pretreatment energy demand and yielded comparable results.

Electric field pretreatment was investigated for corn, sunflower, and soybean residues under two excitation regimes, representing low-field, short-duration treatments. Energy consumption depended strongly on treatment duration, electric field strength, and substrate characteristics, and the results were therefore normalized to a pretreatment duration of 1 h to enable comparison across treatments.

The net energy analysis demonstrated that positive energy balances can be achieved either by applying low electric field strengths over longer pretreatment times or by using high electric field strengths combined with very short exposure times. In both cases, the energy consumed during pretreatment was small compared to the additional biogas energy generated during anaerobic co-digestion, confirming the energetic feasibility of electric field pretreatment under appropriately selected conditions.

In the absence of established and widely accepted protocols for calculating energy consumption in electric field pretreatment processes, this study provides a structured and transparent methodological approach that can serve as a reference framework for future studies in this field. By enabling consistent and comparable assessment of energy demand and net energy balance across different substrates, pretreatment conditions, and experimental setups, the proposed methodology addresses a current methodological gap. As such, it supports improved reproducibility, facilitates comparison among studies, and provides a practical basis for the integration of energy demand calculations into broader techno-economic and sustainability evaluations of biogas production systems. As such, it supports energy-efficient optimization of electric field pretreatment and provides a robust basis for the development, evaluation, and integration of more sustainable and energy-efficient biogas production systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.R., V.M. and Đ.K.; methodology, S.R. and V.M.; software, S.R.; validation, S.R. and V.M.; formal analysis, S.R.; investigation, S.R. and Đ.K.; resources, S.R. and D.K.; data curation, S.R.; writing—original draft preparation, S.R. and V.M.; writing—review and editing, Đ.K.; visualization, S.R.; supervision, S.R.; funding acquisition, D.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Faculty of Electrical Engineering, Computer Science and Information Technology Osijek, project: “Threat Detection System for Wireless Network Environments (SOS-BMO)”. This research was funded by the European Union—Next Generation EU. However, the views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Commission. Neither the European Union nor the European Commission can be held responsible for them.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Capodaglio, A.G. Pulse Electric Field Technology for Wastewater and Biomass Residues’ Improved Valorization. Processes 2021, 9, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunatsa, T.; Xia, X. A Review on Anaerobic Digestion with Focus on the Role of Biomass Co-Digestion, Modelling and Optimisation on Biogas Production and Enhancement. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 344, 126311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alengebawy, A.; Ran, Y.; Osman, A.I.; Jin, K.; Samer, M.; Ai, P. Anaerobic Digestion of Agricultural Waste for Biogas Production and Sustainable Bioenergy Recovery: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2024, 22, 2641–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govarthanan, M.; Manikandan, S.; Subbaiya, R.; Krishnan, R.Y.; Srinivasan, S.; Karmegam, N.; Kim, W. Emerging Trends and Nanotechnology Advances for Sustainable Biogas Production from Lignocellulosic Waste Biomass: A Critical Review. Fuel 2022, 312, 122928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, E.; Schaefer-Ridder, M.; Wang, Y.; Hofschneider, P.H. Gene Transfer into Mouse Lyoma Cells by Electroporation in High Electric Fields. EMBO J. 1982, 1, 841–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toepfl, S.; Heinz, V.; Knorr, D. High Intensity Pulsed Electric Fields Applied for Food Preservation. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2007, 46, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchmann, L.; Mathys, A. Perspective on Pulsed Electric Field Treatment in the Bio-Based Industry. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demir, E.; Tappi, S.; Dymek, K.; Rocculi, P.; Gómez Galindo, F. Reversible Electroporation Caused by Pulsed Electric Field—Opportunities and Challenges for the Food Sector. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 139, 104120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirley, S.A.; Heller, R.; Heller, L.C. Chapter 7—Electroporation Gene Therapy. In Gene Therapy of Cancer, 3rd ed.; Lattime, E.C., Gerson, S.L., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2014; pp. 93–106. ISBN 978-0-12-394295-1. [Google Scholar]

- Spugnini, E.P.; Condello, M.; Crispi, S.; Baldi, A. Electroporation in Translational Medicine: From Veterinary Experience to Human Oncology. Cancers 2024, 16, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casciati, A.; Tanori, M.; Gianlorenzi, I.; Rampazzo, E.; Persano, L.; Viola, G.; Cani, A.; Bresolin, S.; Marino, C.; Mancuso, M.; et al. Effects of Ultra-Short Pulsed Electric Field Exposure on Glioblastoma Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, N.; Abdul-Malek, Z.; Roobab, U.; Qureshi, M.I.; Khan, N.; Ahmad, M.H.; Liu, Z.-W.; Aadil, R.M. Effective Valorization of Food Wastes and By-products through Pulsed Electric Field: A Systematic Review—Arshad—2021—Journal of Food Process Engineering—Wiley Online Library. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jfpe.13629 (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Golberg, A.; Sack, M.; Teissie, J.; Pataro, G.; Pliquett, U.; Saulis, G.; Stefan, T.; Miklavcic, D.; Vorobiev, E.; Frey, W. Energy-Efficient Biomass Processing with Pulsed Electric Fields for Bioeconomy and Sustainable Development. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2016, 9, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redondo, D.; Venturini, M.E.; Luengo, E.; Raso, J.; Arias, E. Pulsed Electric Fields as a Green Technology for the Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Thinned Peach By-Products. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2018, 45, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Jeong, S.-W.; Chung, Y. Enhanced Anaerobic Gas Production of Waste Activated Sludge Pretreated by Pulse Power Technique. Bioresour. Technol. 2006, 97, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittmann, B.E.; Lee, H.; Zhang, H.; Alder, J.; Banaszak, J.E.; Lopez, R. Full-Scale Application of Focused-Pulsed Pre-Treatment for Improving Biosolids Digestion and Conversion to Methane. Water Sci. Technol. J. Int. Assoc. Water Pollut. Res. 2008, 58, 1895–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, M.B.; Lee, H.-S.; Parameswaran, P.; Rittmann, B.E. Using a Pulsed Electric Field as a Pretreatment for Improved Biosolids Digestion and Methanogenesis. Water Environ. Res. 2009, 81, 831–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Deng, Y.D.; Zhang, J.; Liu, F.J.; Men, Y.K.; Wang, Z.; Du, B.X. Effect of Pulsed Electric Field on Pretreatment Efficiency in Anaerobic Digestion of Excess Sludge. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 11th International Conference on the Properties and Applications of Dielectric Materials (ICPADM), Sydney, Australia, 19–22 July 2015; pp. 840–843. [Google Scholar]

- Ki, D.; Parameswaran, P.; Rittmann, B.E.; Torres, C.I. Effect of Pulsed Electric Field Pretreatment on Primary Sludge for Enhanced Bioavailability and Energy Capture. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2015, 32, 831–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safavi, S.M.; Unnthorsson, R. Methane Yield Enhancement via Electroporation of Organic Waste. Waste Manag. 2017, 66, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuşçu, Ö.S.; Selçuk, Ç.; Çört, N. Disintegration of Sewage Sludge Using Pulsed Electrical Field Technique: PEF Optimization, Simulation, and Anaerobic Digestion. Environ. Technol. 2022, 43, 2809–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocker, R.; Silva, E.K. Pulsed Electric Field Technology as a Promising Pre-Treatment for Enhancing Orange Agro-Industrial Waste Biorefinery. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 2116–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plume, I.; Dubrovskis, V. Engineering for Rural Development 2021—Proceedings. Available online: https://www.iitf.lbtu.lv/conference/proceedings2021/ (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Lindmark, J. Developing the Anaerobic Digestion Process through Technology Integration. Ph.D. Thesis, Mälardalen University, Västerås, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- El Achkar, J.H.; Lendormi, T.; Salameh, D.; Louka, N.; Maroun, R.G.; Lanoisellé, J.-L.; Hobaika, Z. Influence of Pretreatment Conditions on Lignocellulosic Fractions and Methane Production from Grape Pomace. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 247, 881–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szwarc, D.; Nowicka, A.; Zieliński, M. Comparison of the Effects of Pulsed Electric Field Disintegration and Ultrasound Treatment on the Efficiency of Biogas Production from Chicken Manure. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raso, J.; Frey, W.; Ferrari, G.; Pataro, G.; Knorr, D.; Teissie, J.; Miklavčič, D. Recommendations Guidelines on the Key Information to Be Reported in Studies of Application of PEF Technology in Food and Biotechnological Processes. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 37, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačić, Đ.; Kralik, D.; Rupčić, S.; Jovičić, D.; Spajić, R.; Tišma, M. Electroporation of Harvest Residues for Enhanced Biogas Production in Anaerobic Co-Digestion with Dairy Cow Manure. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 274, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, G. Solid State Tesla Coil; Kansas State University: Manhattan, KS, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kovačić, Đ. Razvoj Procesa Predobrade Lignoceluloznih Materijala Toplinom i Električnim Poljem u Svrhu Primjene u Proizvodnji Bioplina Anaerobnom Kodigestijom s Goveđom Gnojovkom. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329358411_Razvoj_procesa_predobrade_lignoceluloznih_materijala_toplinom_i_elektricnim_poljem_u_svrhu_primjene_u_proizvodnji_bioplina_anaerobnom_kodigestijom_s_govedom_gnojovkom (accessed on 31 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.