Abstract

Teaching the host country’s language is not only a form of linguistic education but also a means of integrating foreign citizens into society, thereby promoting sustainable cultural change and social inclusion. This article, based on an ecolinguistic approach combined with Gardner’s motivation theory, examines the opportunities for social inclusion of international students at VILNIUS TECH (Vilnius Gediminas Technical University, Lithuania) through learning Lithuanian as the host country’s language. From the ecolinguistic perspective—which highlights the interconnections between language, identity, and the learning environment, and which shapes sustainable human relationships and social behavior—the study analyses the instrumental and integrative motivation of international students learning Lithuanian. A quantitative survey of 212 bachelor-level students was conducted, and responses were analyzed using descriptive statistics and motivational categories. The findings reveal that integrative motivation (cultural interest, respect for the host country, and desire for belonging) is significantly stronger than instrumental motivation (career and pragmatic value). However, despite strong positive attitudes toward the language, students experience limited social inclusion and few opportunities to use Lithuanian outside the classroom. The interplay between motivation types and environmental conditions shows how language learning contributes to social inclusion, the preservation of the host country’s linguistic prestige, and broader cultural sustainability.

1. Introduction

In a politically and economically complex reality marked by constant migration processes and increasing division of people into certain groups, the ideas of global sustainability become especially important. On the one hand, this migration enables people to seek a better life, avoid war, and escape poverty; on the other hand, it creates numerous challenges for host countries. In recent years, study-related migration in Europe has intensified significantly.

Migration compels us to view the world as a system of interconnected and interwoven structures that transcend national borders—a whole in which humans depend on their environment, and the environment, in turn, depends on humans. Therefore, for every country, the acceptance of immigrants is important in terms of meeting their needs in terms of safeguarding national systems that shape a country’s identity. When discussing sustainability, attention should be drawn to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, one of which is “to reduce inequality within and among countries” [1]. In the context of sustainable development goals and migration, it is worth noting that this inequality relates not only to the (in)equality between immigrants and the host community but also to the relationship between English as a prestigious language and the host country’s language (in this case, Lithuanian). The use of English in migration-related processes—studies, work, administrative procedures, and everyday situations in a foreign country—strengthens the dominance of English and reduces the prestige of the host country’s language, weakening its position in public life.

Thus, a major challenge arises of how to welcome immigrants without harming the host country or its language. As noted by Bradley and co-authors (2017) [2], migrants face additional challenges when moving to countries whose language is not widely used beyond national borders. This encourages an examination of whether individuals are willing to learn the host country’s language when it is a small language (in this article, the term “small language” refers to a language with a small number of users—speakers—and limited geographical distribution) and is perceived as having limited global utility.

However, learning the host country’s language is important and not only for maintaining the status of the language itself. In the context of global migration, proficiency in the host country’s language is increasingly recognized as a key factor in integration. This idea is also reinforced in documents issued by EU (European Union) institutions (the Council of Europe and the European Commission): “Basic knowledge of the host society’s language, history and institutions is indispensable to integration; enabling immigrants to acquire this basic knowledge is essential to successful integration.” [3]. Knowing the language, along with becoming familiar with the host country’s culture and history, is vital for preventing the segregation or social exclusion of migrants.

However, the implementation of integration policies is not without risks. Some researchers argue that promoting the learning of the national language for integration purposes may serve a political agenda aimed at reinforcing “national identity” and the “dogma of homogeneity” [4,5]. In such cases, immigration policy instruments—such as language requirements—may become mechanisms of political control or ideological resistance to the perceived erosion of national sovereignty in an increasingly international and cosmopolitan world [6].

From what has been discussed, the reality surrounding migration processes is complex and contradictory, requiring comprehensive, multi-faceted research that cannot fit within the scope of a single article. This publication focuses on the issue of social inclusion through language among international students who come to Lithuania to study for four years—a matter closely linked to their motivation to learn the host country’s language. On the other hand, when examining these questions, the attitudes of immigrants toward the Lithuanian language inevitably emerge—as mentioned, environmental systems are interconnected and influence one another. Therefore, the study should also reveal the situation of the Lithuanian language within the broader context of migration.

The aim of this article is to examine the social integration of international students studying at VILNIUS TECH through the learning of Lithuanian as the host country’s language.

The following research questions were raised:

- To review the ecolinguistic approach to language learning and its connections with sustainable education and social inclusion.

- To discuss the features of Gardner’s integrative and instrumental motivation.

- Using a questionnaire based on ecolinguistic ideas and Gardner’s motivation theory, to reveal the attitudes of VILNIUS TECH international students toward the Lithuanian language by assessing the significance of their motives (reasons) for learning it.

- To assess the impact of the practical applicability of the Lithuanian language on students’ motivation and social inclusion, and to figure out how students’ self-evaluated social integration into Lithuanian society correlates with their attitudes toward the social environment.

Since, as mentioned, immigrants’ linguistic behavior affects the host country’s language, and attitudes toward social inclusion are linked to attitudes toward the host country’s language and the motivation to learn it, this article employs the ecolinguistic approach and Gardner’s motivation theory as suitable frameworks for the issues under examination. These theories will be discussed in the following section of the article, “Theoretical Background.”

Based on the questionnaire survey, the study examines how international students’ instrumental and integrative motivation align when learning a language that is small and not widely used globally, and how proficiency in the host country’s language contributes to social inclusion. From this perspective, language learning is understood as part of global sustainability—ensuring meaningful dialogue between newcomers and locals, fostering the genuine inclusion of international students in Lithuanian society, and contributing to the preservation of the prestige of the Lithuanian language and the maintenance of its proper position in public life.

This study is closely aligned with several United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). First, it contributes to SDG 4 (Quality Education) by examining how access to host-country language learning supports inclusive and equitable higher education for international students. Second, by analyzing the linguistic and social barriers faced by newcomers, the study addresses SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities), especially the goal of reducing social, cultural, and linguistic disparities between migrants and host communities. Finally, because language ability is essential for participation in civic, social, and institutional life, the research speaks directly to SDG 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions), highlighting how effective language policies and inclusive educational environments can strengthen social cohesion and contribute to sustainable, resilient societies.

The article is structured as follows: Section 2 presents a review of the problem field, while Section 3 provides an overview of the relevant literature. Section 4 outlines the methodology employed. Section 5 presents the results together with their interpretation. Section 6 discusses the findings. Finally, Section 7 concludes the article and offers practical recommendations based on the results.

2. Problem Statement

Although knowledge of the host country’s language is crucial for integration, the motivation to learn it often encounters significant obstacles. In academic literature, language learning motivation is described as a combination of three elements: the desire to learn, the effort invested (motivation intensity), and the learner’s attitude toward the language [6,7]. Nevertheless, studies—for example, Dörnyei (2005) [8]—show that the global dominance of English as the “default foreign language” reduces motivation to learn less widely used languages.

Therefore, languages such as Lithuanian—spoken by a relatively small number of people and limited in geographical reach—may be perceived as offering limited utility. This is particularly relevant for migrants, including international students, who may believe that the language provides little practical benefit.

Lithuania is a relatively small European country. As of 1 January 2025, it had a population of 2.89 million permanent residents [9]. An important issue examined in this study is the limited “popularity” of the Lithuanian language—a factor determined by the small number of its speakers and its restricted geographical use.

A particularly important factor for the situation of the Lithuanian language is that immigration to Lithuania has increased significantly in recent years, while the number of ethnic Lithuanians has decreased. Between 2012 and 2022, the population of Lithuania fell from 3.0 million to 2.8 million. However, this trend reversed in 2022 due to a rise in positive net migration. In 2023, the population increased by 46.5 thousand, in 2024 by another 29 thousand, and in 2025 by an additional 4.3 thousand. This change is largely linked to the influx of war refugees from Ukraine, followed by arrivals of immigrants from Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and other countries.

Some of these immigrants choose to study at Lithuanian universities. However, the country’s universities attract not only political migrants—there are also many students in Lithuania from India, Nigeria, Israel, Turkey, as well as from various European countries.

In a statement released on 4 September 2025, the Lithuanian Migration Department noted that studies in Lithuania are increasingly being used merely to obtain a temporary residence permit and enter the Schengen area. The Migration Department reported that at the beginning of September 2025, there were 9009 foreign nationals registered in Lithuania who held a temporary residence permit based on studies. The number of students from some countries has grown particularly rapidly: from India—from 568 (in 2023) to 1539 (in 2025); from Pakistan—from 100 to 1039; and from Bangladesh—from 32 to 557 [10].

The Lithuanian Government aims to ensure that incoming students do not view Lithuania only as a temporary stopover but rather remain in the country after completing their studies and try their luck in the local labor market. Therefore, learning the Lithuanian language is also a political tool—one that supports integration into the labor market.

Given recent demographic changes and the broader geopolitical context, Lithuania has intensified its efforts to integrate immigrants, placing particular emphasis on the acquisition of language skills. One of the main measures introduced is the Language Requirement (LR). Starting from 1 January 2026, individuals working directly with customers in the goods and services sectors will be required to prove their proficiency in Lithuanian at a level determined by the Government.

A proposed amendment to the Law on the State Language obliges service providers and salespersons to ensure communication in Lithuanian, with certain exceptions outlined in the Law on Science and Studies. The law also stipulates that information about products and their labelling must be provided in Lithuanian.

In turn, weak motivation to learn the language of a small country reduces immigrants’ opportunities to integrate into society. A lack of language skills is one of the main factors that complicates communication with migrants [11]. Language is a key instrument of communication and not knowing it can create serious obstacles for migrants and their families when integrating into a new society. Proficiency in the language, along with knowledge of the host country’s culture, history, living conditions, and laws, helps migrants adapt more effectively to their new environment.

Not knowing the language can lead to feelings of helplessness and insecurity and negatively affect interactions with residents. A lack of language skills may cause considerable stress and misunderstandings not only for migrants themselves but also for the professionals who work with them. It can also hinder the ability both to provide and to receive appropriate and qualified support.

Hypothesis: The limited practical use of the Lithuanian language compared to English reduces learners’ instrumental motivation, hindering the development of a balanced motivational profile that is essential for successful language learning outcomes and social inclusion, and it may contribute to ecolinguistic sustainability.

3. Theoretical Background

As noted above, this article combines the ecolinguistic approach with Gardner’s motivation theory to achieve its aim—the questionnaire was designed based on this theoretical foundation. The ecolinguistic perspective allows the problem under examination to be evaluated holistically, while Gardner’s motivation theory helps to understand international students’ opportunities for inclusion, as well as the need for and duration of their engagement. The ordering of questions was based not on a formal typology of instrumental categories but on the internal logic of content and evaluation. This structure was chosen deliberately to minimize priming effects and reduce the likelihood that question order would influence respondents’ answers, thereby improving data quality and response reliability. Within this framework, linguistic ecosystems are understood as a prerequisite for sustainable integration: when language environments support access, participation, and continuity, integration outcomes become more resilient and equitable. The theoretical background is discussed in greater detail below.

3.1. Ecolinguistic Approach

Ecolinguistic Approach. Ecolinguistics, an interdisciplinary field that emerged from E. Haugen’s [12] concept of the ecology of language, provides a valuable conceptual framework for examining the interrelationships between language, society, and the environment [13,14]. The notion of ecological theory in linguistics was applied more than 50 years ago [15]. The creator of the term, the Norwegian linguist Einar Haugen [12], defined the ecology of language “as the study of interactions between any given language and its environment.” Haugen proposed a fundamental definition of language ecology as the interaction between a language and its environment. He argued that language is shaped by the society that uses it.

Today, ecolinguistics views language as part of a living system—interconnected with cultural, institutional, and social ecosystems. It examines how linguistic practices contribute to sustainability by shaping values, identities, and relationships between people and their environments. In language education, this approach helps to understand how linguistic practices can either support or hinder social inclusion and intercultural communication.

The ecolinguistic perspective on language phenomena is inseparable from holism. The holistic approach in ecolinguistics means that language is not studied in isolation or as a closed system, but rather with full consideration of its environment—that is, the personal, contextual, cultural, and social factors surrounding it. In the study presented in this article, particular attention is given precisely to these factors.

Ecolinguists describe a linguistic phenomenon not only as tightly interconnected internally, but also as, in its own way, independent and interactive with other elements of the system. Interconnectedness means that every part of the whole is linked to the others and, collectively, to the whole system. A linguistic phenomenon is unique in that it changes when other linguistic phenomena change or disappear. This demonstrates their interaction—each part, when changing, affects the others; there is no one-way influence. The interaction is not necessarily symmetrical, as one influence may dominate [16].

From this perspective, we can see how the dominance of English and its reinforcement in migration processes can become highly significant for the situation of the Lithuanian language. Foreigners’ motivation to learn the host country’s language—and through it integrate into society—is essential for maintaining the status of the host country’s language.

3.2. Gardner’s Motivation Theory

R. Gardner [17] described motivation as a complex construct that is very difficult to define; he emphasized that motivation is the result of interaction with the culture of the second language and with the target language itself. According to Gardner’s theory, the social environment and attitudes toward the second language and its communities form the foundation for understanding learners’ language motivation [18]. M. Guerrero [18], citing Dörnyei and Ushioda [6], states that there are three distinct periods in the history of foreign language teaching and learning motivation:

- the social psychological period,

- the cognitive-situated period, and

- the process-oriented period.

According to the author, the first period—the social psychological period (1959–1990)—is associated with R. Gardner’s work in the bilingual context of Canada.

Gardner, together with Lambert [19], introduced the concepts of integrative orientation, associated with a learner’s positive attitude toward learning the language and its culture, and instrumental orientation, associated with practical motives for learning the language. According to Gardner [20], foreign language learning is a socio-psychological phenomenon; therefore, studying motivation to learn another language requires considering the learner’s social context and their attitudes toward the language being learned.

R. Gardner proposed the foundations of instrumental and integrative motivation based on social education theory, where instrumental motivation serves as a means for language learners to achieve their goals and success, while integrative motivation reflects the learner’s interest in the language and its culture, the desire to communicate, and emotional identification with another cultural group [17]. Csizér and Dörnyei [21] argued that integrative motivation is the primary form of motivation in second language learning. However, some researchers have claimed that among learners of English, instrumental motivation constitutes the dominant form, driven mostly by pragmatic aims such as achieving exam success [22]. Gardner and MacIntyre [23] believed that both integrative and instrumental motivation can coexist [24].

Instrumental motivation indicates that the learner studies the language because it is useful—for example, to obtain a higher salary in the future or a better job. This is instrumental motivation expressed as a practical need to learn a foreign language, whereas integrative motivation reflects a person’s internal desire to learn a foreign language [6,20].

Instrumental motivation reflects external needs. A student may discontinue language studies as soon as the practical goal is achieved, which means that many elements of the language may never be acquired. Instrumental motivation tends to dominate in situations where, for example, the learner aims to pass an exam, and once the exam is passed, the student stops learning the language [20].

Regarding integrative motivation, it reflects internal needs and is based on a positive attitude toward the language and culture of the country, as well as a desire to communicate with native speakers. The motives behind integrative motivation include interest, curiosity, and enjoyment. Gardner and Lambert [19] argue that individuals with stronger integrative motivation will make greater efforts and achieve better results. According to Dörnyei and Ushioda, only a combination of these two types of motivation makes it possible to achieve good results [6].

Thus, these aspects were central when preparing the questions for the respondents. The importance of the theoretical framework for the study is summarized schematically (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Theoretical basis for planning the empirical study.

Thus, the analysis of the scientific literature revealed that motivation is a decisive factor in the processes of teaching, learning, and language acquisition. R. Gardner notes that a motivated person wants to learn a foreign language and tries to internalize it. Moreover, a motivated student is satisfied with their work when their motivation is closely linked to their individual needs [17]. This motivation—beyond personal goals—is shaped by the social context as well as by the status of the language itself. By knowing the host country’s language, a foreigner can avoid segregation and engage in the life of the country, thereby contributing to the preservation of the prestige of the host country’s language.

This perspective also highlights that linguistic ecosystems function similarly to ecological systems: when a small language becomes marginalized, social inclusion and long-term community sustainability are weakened. Therefore, understanding students’ linguistic choices becomes essential for assessing sustainable integration outcomes.

4. Materials and Methods

The methods used in the study were as follows: a questionnaire survey, statistical data analysis, and the analytical descriptive method.

For the empirical research, a quantitative research method was chosen—a questionnaire survey of VILNIUS TECH international students. The quantitative approach makes it possible to draw conclusions about a larger population (all international students at the university) based on data collected from a sample (a relatively small population). A questionnaire was designed for this purpose. As mentioned earlier, the questionnaire is based on Gardner’s motivation theory, which views language learning as a social and psychological experience. Gardner’s distinction between integrative and instrumental motivation guided the formulation of the survey questions.

In preparing the questions, the approach was followed in that understanding motivation requires examining both the respondents’ social environment and their attitudes toward the target language. The final questions on social integration aim not only to assess how respondents themselves evaluate their social involvement in Lithuanian society but also to examine how this self-assessment correlates with responses to earlier questions concerning their attitudes toward Lithuanian, as well as the social, cultural, and political environment.

The questionnaire consists of 22 closed-ended questions. The ordering of the questions was based not on a formal assignment to instrumental categories but on the logic of content and evaluation. This decision was made deliberately to minimize the influence of question order on respondents’ answers, thereby ensuring data quality, respondent engagement, and the reliability of responses.

A five-point response scale is provided for each question, which helps respondents select answers more easily, reduces the time required to complete the questionnaire, and simplifies data processing, comparison, and evaluation. The information was collected using standard procedures: each selected respondent answered the same questions in the same manner. The aim of the survey was not to determine everyone’s opinion but to form a general description of the segment of the population under study. In the presentation of the empirical research, the data are shown after eliminating the portion of responses marked as neutral. Neutral responses were excluded because they did not reflect a clear evaluative direction and, therefore, did not contribute meaningful information to the research aim. In addition, only a very small proportion of respondents selected the neutral option, making this category statistically negligible and unlikely to influence the general trends.

The prepared questionnaire was uploaded to the website www.apklausa.lt. A request to complete the questionnaire was sent by email to all international bachelor’s students at VILNIUS TECH.

Participants and Data Collection

In the 2024–2025 academic year, 1444 degree-seeking foreign students and 565 exchange students studied at VILNIUS TECH. Since the research focuses on social inclusion, it was important to survey international students who were studying in Lithuania for four years and possibly longer (i.e., those who may continue into master’s studies).

According to the 2025 VILNIUS TECH admission results, of the 2805 newly admitted students, 23.2% came from foreign countries, and currently a total of 23.6% of all university students are foreigners from 81 countries. Among them, the largest groups of students came from India, Ukraine, Azerbaijan, Türkiye, and Morocco. The five most popular first-cycle study programs attracting the highest number of applicants were the following: Artificial Intelligence Systems, Computer Engineering, Business Management, Information Technologies, and Creative Industries. At the second-cycle level, the programs that attracted the most applicants were as follows: Entrepreneurial Leadership, Information and Information Technology Security, International Business, Information Systems Engineering, and Industrial Engineering and Innovation Management [25]. It is important to note that according to the data of the Migration Department, some international students have changed their field of study. As a result, their studies will be extended beyond the usual duration [10].

A total of 212 VILNIUS TECH undergraduate international students participated in the survey. Given a population of 1444 students and a 95% confidence level, the maximum sampling error was calculated at approximately 6.25%, accounting for the finite population correction. The results are therefore representative of VILNIUS TECH international students, but generalization beyond this institutional context is not possible.

The respondents’ ages ranged from 17 to 25 years. They represented Ukraine, India, Belarus, Turkey, Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, and Germany. It is important to stress that analyses across demographic or cultural subgroups were not planned in the study design. Given the aim and scope of this research, the study is not comparative; therefore, subgroup segmentation would not align with the research objectives. Students from the following faculties participated in the survey: the Faculty of Architecture, the Faculty of Fundamental Sciences, the Faculty of Creative Industries, the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, and the Faculty of Transport Engineering. It is important to note that Lithuanian is not a compulsory study subject for international students—they may study it either through Lithuanian language courses offered by VILNIUS TECH or as an elective subject.

5. Results

Since motivation is essential in any learning process, and it is primarily determined by each learner’s personal motives and pragmatic goals—which shape the learner’s relationship with the object of learning (in this study, the subject of Lithuanian as a foreign language)—the initial aim of the empirical survey questions presented to the respondents (international students at VILNIUS TECH) was to reveal their relationship with the Lithuanian language by assessing the importance of the motives (reasons) that encourage them to learn it. In formulating the questions, the following groups of motives were identified:

- Motives related to instrumental motivation, where Lithuanian is learned in order to acquire knowledge that helps improve qualifications, pursue a career, and obtain similar goals (Questions 4, 6, 10, 15);

- Motives related to integrative motivation, where Lithuanian is learned to integrate into a foreign—i.e., the host country’s—culture, to adopt its social heritage, and so forth (Questions 1, 3, 11, 13, 16).

On the other hand, since foreign language learning is a socio-psychological phenomenon, the study also sought to reveal the respondents’ attitudes toward the Lithuanian language (Questions 17–20).

The analysis of the research results revealed that some of the most important motives encouraging respondents to learn Lithuanian are related to integrative motivation. The overwhelming majority of respondents agree that “knowledge of Lithuanian helps me feel better in Lithuania” (only 3.8% disagree or partly disagree). Most respondents (90.9%—of whom 64.6% agree and 26.3% partly agree) state that “through the Lithuanian language, I want to get to know the people and culture of Lithuania,” or that they learn Lithuanian “out of respect for the country” (87.8—70.6% agree and 17.2% partly agree). In addition, respondents feel that “knowledge of Lithuanian helps me understand Lithuanians better” (87.1—61.7% agree and 25.4% partly agree).

Importantly, external, pragmatic motivation—for example, participating in political or public life—is less important to the respondents. Nearly one-third of respondents disagreed (28.3—7.1% disagreed and 21.2% partly disagreed) with the statement: “Knowing Lithuanian is important for me in order to participate in the country’s democratic processes and public life.” This may reflect both the respondents’ age group (17–20 years) and the mobility associated with globalization. Today’s youth tend to be more mobile, frequently relocating for studies or work.

On the other hand, this also supports the claim discussed in the problem section—raised by the Lithuanian Migration Department—that for international students, Lithuania may serve only as a temporary stopover.

Thus, the analysis of the statistical indicators of motives related to integrative motivation shows that respondents possess strong internal motivation to develop an emotional and cultural connection with the host country (Lithuania) and its people—i.e., to seek a sense of national identity within the host society. However, external pragmatic motivation, aimed at social integration into the host country’s political and public processes, is less important to them.

The analysis of the empirical research results shows that motives associated with instrumental motivation are less important to respondents than those related to integrative motivation. Theoretically, motivation is strengthened when learners see opportunities to obtain well-paid jobs or build successful careers—situations in which language is viewed as a tool or instrument. Although most VILNIUS TECH international students agree (88.2—54.7% agree and 33.5% partly agree) that “Lithuanian will help me integrate into the Lithuanian job market/find a job,” nearly one-third of respondents do not believe that successful Lithuanian language learning will ensure success “when looking for a job in Lithuania” (10.3% disagree and 15.1% partly disagree). They also lack motivation “to understand Lithuanian scientific articles and other academic/professional literature” (15.8% disagree and 18.2% partly disagree).

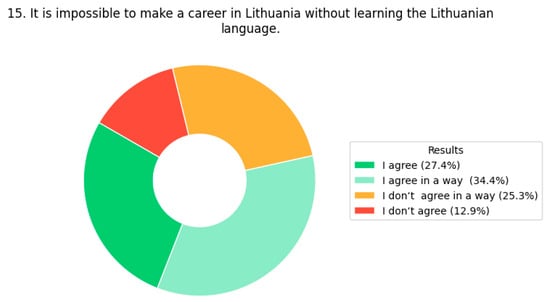

It should also be noted that respondents’ views diverge even more sharply regarding the statement “It is impossible to build a career in Lithuania without learning Lithuanian”: only 27.4% agree, 34.4% partly agree, and more than one-third disagree (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Distribution of respondents’ opinions regarding the statement “It is impossible to build a career in Lithuania without learning Lithuanian”.

A five-point response scale was used. Neutral answers were removed (3 of 212). The majority of respondents agree that learning Lithuanian is important for career opportunities in Lithuania. The responses reflect the current labour market situation in Lithuania’s major cities—especially Vilnius, where many international or foreign-capital companies operate and conduct their activities in English. Considering these answers, and recognising that motivation is a constantly changing psychophysiological phenomenon, it may be inferred that respondents’ Lithuanian language learning will not be long-term, in-depth, or continuous. In this case, the strength of instrumental motivation—visible in the responses related to job searching and of establishing oneself in the labour market—could be interpreted as temporary.

If Lithuanian is not necessary for building a career, the question arises whether a foreigner studying in Lithuania—who already speaks English well—needs to know Lithuanian at all. As mentioned earlier, the dominance of English and its reinforcement in migration processes can have a significant impact on the survival of Lithuanian as a small language. Foreigners’ motivation to learn the host country’s language—and through it engage with society—is essential for preserving the status of the host country’s language.

For these reasons, during the VILNIUS TECH international student survey, an effort was made to assess this target group’s attitudes toward the language requirements for foreigners established and implemented as part of the host country’s integration policy. The study also aimed to reveal how respondents evaluate statements related to the limited global reach of the Lithuanian language.

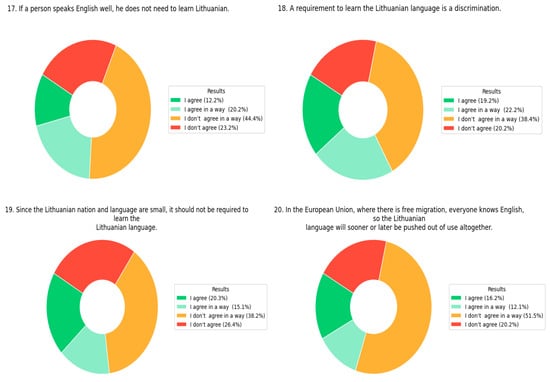

VILNIUS TECH international students were asked to evaluate several rather provocative statements, such as the following:

“If a person speaks English well, they do not need to learn Lithuanian.”

“The requirement to learn Lithuanian is discrimination.”

“Since the Lithuanian nation and language are small, learning Lithuanian should not be mandatory.”

“In the EU, where there is free movement and everyone speaks English, Lithuanian will sooner or later be completely pushed out of active use.”

The respondents’ opinions varied considerably when answering these statements (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Distribution of respondents’ opinions when evaluating statements about their attitudes toward the Lithuanian language.

A five-point response scale was used. Neutral answers were removed (Q17: 2; Q18: 3; Q19: 0; Q20: 5). Most respondents disagree with statements suggesting that small languages are unnecessary or endangered solely due to English dominance.

The Impact of the Practical Applicability of the Lithuanian Language on Students’ Motivation and Social Inclusion

Based on the ecolinguistic perspective—which holds that language, identity, and the learning environment are interconnected, and that language shapes sustainable interpersonal relationships and social behaviour—the empirical study analysed how the interaction of instrumental and integrative motivation among VILNIUS TECH international students learning Lithuanian encourages social inclusion, helps preserve the prestige of the host country’s language, and thus contributes to global sustainability.

In assessing respondents’ opportunities for inclusion and the surrounding environmental conditions, one component examined was the relationship between VILNIUS TECH international students and Lithuanians (the country’s autochthonous population, e.g., other VILNIUS TECH students, the wider society) (Questions 12 and 14). The study also aimed to evaluate the learning environment and conditions (Questions 2, 5, 7–9).

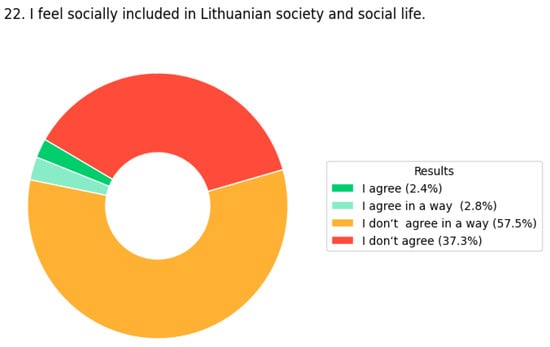

A paradoxical situation was identified: despite the very strong indicators related to respondents’ positive attitudes toward the Lithuanian language and their motivation to learn it, the environmental conditions for integration and social inclusion turn out to be extremely weak. Only 5.2% (2.4% agree, 2.8% partly agree) of the surveyed VILNIUS TECH international students agree with the statement “I feel socially included in Lithuanian society” (see Figure 4). Conversely, as many as 92.9% (81.8% agree and 11.1% partly agree) state that “Even while learning Lithuanian, I mostly communicate with international students.”

Figure 4.

Distribution of respondents’ opinions regarding the statement “I feel socially included in Lithuanian society and social life”.

A five-point response scale was used. Neutral answers were removed (0 of 212). Respondents do not feel socially included in Lithuanian society or social life. A percentage of 66.7% of respondents agree (30.3% agree and 36.4% partly agree) with the statement “Lithuanian students are friendly and help me learn the Lithuanian language,” while one-third do not agree (12.1% disagree and 21.2% partly disagree) with this statement. The lack of social inclusion is perhaps most clearly illustrated by the relatively small proportion of respondents who intend to stay in Lithuania permanently or for a longer period—only 8.5% agree, and an additional 5.7% partly agree (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Distribution of respondents’ opinions regarding the statement “I plan to stay in Lithuania permanently or for a longer period”.

A five-point response scale was used. Neutral answers were removed (3 of 212). Most respondents do not plan to stay in Lithuania long term. On the other hand, VILNIUS TECH international students evaluate the Lithuanian language learning environment at the university—both didactically and emotionally—very positively. That is, the majority agree with statements such as: “learning Lithuanian is fun” (84.9%, of whom 44.3% agree and 40.6% partly agree); “I succeed when learning from interesting textbooks” (86.8%, of whom 61.8% agree and 25% partly agree); “I enjoy learning because the teacher uses interesting teaching methods” (81.6%, of whom 63.7% agree and 17.9% partly agree). They feel good in Lithuanian language classes when “they easily remember language points” (91%, of whom 67.9% agree and 23.1% partly agree), and when “they manage to complete tasks successfully” (86%, of whom 75.9% agree and 14.1% partly agree).

Thus, most respondents (international students at VILNIUS TECH) have developed a positive attitude toward the process of learning Lithuanian and the conditions provided by the university. They view learning Lithuanian as a meaningful activity and are successfully engaged in the process.

From an ecolinguistic perspective, the results suggest that a positive micro-environment (in the classroom) could serve as an additional factor in strengthening students’ integrative motivation, even if the broader social environment outside the university does not adequately support such conditions.

In summarizing the results of the empirical study, it can be stated that the hypothesis was only partially confirmed: the limited practicality of the Lithuanian language (in other words, its low popularity due to the small number of speakers and its restricted geographical use), combined with the dominance of English, reduces instrumental motivation, prevents the achievement of a balanced motivational profile, and decreases social inclusion.

6. Discussion

The paradox revealed in the study—high integrative motivation alongside low levels of social inclusion—requires broader explanation and further research. One possible explanation is that the students who participated in the survey, as discussed in Section 5, had voluntarily chosen to study the Lithuanian language course. Therefore, it can be assumed that their desire to integrate through language is stronger than that of international students who did not select this elective. As a result, the high integrative motivation observed in the findings may be partially influenced by self-selection bias, which—together with the narrow scope of the sample (students from a single university)—limits the generalizability of the results. The findings cannot be generalized to a wider population, also because inferential statistical analysis was not applied. Consequently, the results cannot be extended to broader audiences or used for more robust predictions. Future research examining social inclusion through the learning of a globally less widespread language should therefore include students who did not voluntarily choose to study Lithuanian.

A second paradox concerns the linguistic environment itself. Although students express positive attitudes toward Lithuanian, they report managing academic and professional life in Lithuania almost entirely through English. According to research data, English is required not only in internationally operating companies but also in those operating on a national scale. M. Kiškytė writes: “In the Baltic region, English is the most demanded foreign language skill: it is mentioned in 98% of vacancies” [26]. This study confirms the competition between Lithuanian and English in the labour market. This indicates a structural dynamic in which institutional reliance on English reduces daily contact with Lithuanian speakers, creating a form of linguistic segregation. Thus, while students’ attitudes toward Lithuanian are favorable, broader studies are needed to assess the long-term sustainability of Lithuanian in an increasingly English-dominant academic and professional ecosystem.

In international study programs and in internationally oriented companies where foreign students are employed, English dominates, reducing the practical need for Lithuanian and indirectly weakening the motivation to learn it. While this practice certainly facilitates integration into English-speaking communities, it simultaneously reinforces linguistic separation and hinders integration into Lithuanian-speaking society—thus becoming a factor of social segregation.

Therefore, although respondents express positive attitudes toward the Lithuanian language, a broader study would be necessary to make predictions regarding the long-term sustainability of Lithuanian.

Due to the small sample size, it was not meaningful to link motivation to learn the host country’s language with the cultural characteristics of international students. Other studies show that motivation also depends on the country of origin of the immigrant. For example, research conducted by Baohua Yu and Kevin Downing shows that “the non-Asian (Western) group, consisting of Americans, French, and Germans, can afford integrative motivation. They are learning Chinese for their interest in Chinese culture and not necessarily for specific instrumental reasons” [27]. Thus, the political and economic situation of a student’s home country, as well as cultural factors, may also influence motivation to learn the Lithuanian language.

Research results align with broader national-level discussions in Lithuania concerning the integration of international students and immigrants. The low intention to remain in Lithuania after graduation—expressed by only a small minority of respondents—raises concerns regarding talent retention and the effectiveness of integration policies. While the state plans to introduce the 2026 Language Requirement (LR) to increase Lithuanian language use in the labor market, the study suggests that externally imposed requirements may strengthen instrumental motivation only temporarily and may be insufficient without corresponding improvements in social inclusion and authentic opportunities for real-world language use.

These findings underscore the need for universities and policymakers to develop targeted strategies that expand opportunities for intercultural interaction, such as language tandems, mentorship programs, volunteer activities, and structured cooperation between Lithuanian and international students. Without such interventions, the linguistic ecosystem risks remaining fragmented, with positive classroom experiences failing to translate into broader societal integration.

Future research should include comparative studies, mixed-method designs, and deeper analysis of cultural and sociopolitical factors influencing students’ willingness to integrate into Lithuanian society. But it is important to continue the survey in the future because by strengthening the link between language learning and participation in society, Lithuania can enhance the long-term integration potential of migrants and support sustainable development goals at national and international levels.

7. Conclusions

The analysis of the results revealed that VILNIUS TECH international students exhibit both instrumental and integrative motivation; however, integrative motivation is dominant. Students associate learning Lithuanian primarily with the desire to better understand residents, become part of the community, and explore the culture. What motivates them most to learn Lithuanian as a foreign language is a positive emotional connection to Lithuania—its people, language, and culture—rather than pragmatic or career-oriented goals.

Instrumental motivation is significantly weaker: the practical value of the language for professional careers is viewed ambiguously, and for some students English appears sufficient for practical purposes. Motives related to instrumental motivation (e.g., career, academic purposes, participation in public life) are weaker than integrative motives.

The analysis revealed that the “smallness” of the Lithuanian language does not diminish international students’ motivation to learn it. Through language learning, they express respect for the language, acknowledge the importance of preserving it, and believe that learning Lithuanian would have a positive impact on their lives in Lithuania. They also agree that knowledge of Lithuanian contributes to social inclusion by helping form a strong emotional and cultural connection with the host country and its people, making the language part of their identity and personal fulfilment. Thus, students’ relationship with the Lithuanian language is positive, though oriented more toward cultural rather than pragmatic motives.

However, responses to other questions related to the Lithuanian language also reveal the complexity of the language’s situation: international students’ belief that Lithuanian is not necessary for building a career reflects the strong position of English in Lithuania’s public sphere.

According to the study data, the social inclusion of international VILNIUS TECH students is low, confirmed both by their direct responses to the question about social inclusion and by their answers to indirect questions. Their plans to leave Lithuania after completing their studies and their reluctance to participate in Lithuania’s political life indicate that they do not truly feel part of society. Limited contact with Lithuanians further reduces opportunities to use the Lithuanian language. All of this points to problems of sustainability within the environment: weak social cohesion and social and cultural barriers between Lithuanians and international students.

Overall, the study proves that language learning is a critical part of sustainable integration. These findings underscore the need for policies that recognize the sustainability value of host-country languages, especially in small-language contexts, and highlight the role of universities in advancing global sustainable development.

Recommendations based on the survey are the following:

- Strengthen contact with Lithuanians. Since most international students interact primarily with other international students, it is essential to create mixed projects, mentorship programs, and joint cultural or volunteering activities with Lithuanian students.

- Make the Lithuanian language practically useful. Create short internships or placements that require communication in Lithuanian, organize job fairs, and integrate language-related tasks into study courses.

- Encourage language use outside the classroom. Introduce city-based tasks—interviews, orientation games, and “language missions.”

- Language policy should rely on incentives rather than coercion. Most students support the language requirement, therefore positive measures should be emphasized: scholarships, internships, and priority opportunities for students who have learned the language.

- Create conditions that support entry into the labor market so that international students do not plan to leave Lithuania after completing their studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.Ž. and L.R.; methodology, A.Ž. and L.R.; statistics, V.B.; validation, V.B., A.Ž., and L.R.; formal analysis, A.Ž. and L.R.; survey analysis, V.B.; resources, V.B.; data curation, V.B.; writing—original draft preparation, V.B.; writing—review and editing, A.Ž. and L.R.; visualization, V.B.; supervision, L.R.; project administration, A.Ž. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

In accordance with Regulation (EU) 2016/679 (General Data Protection Regulation, GDPR, Recital 26) (accessed on 11 November 2025) and the Law of the Republic of Lithuania on Legal Protection of Personal Data (accessed on 11 November 2025), the processing of anonymized data does not fall within the scope of personal data regulation. Therefore, approval by an Ethics Committee was not required for this study under national legislation and institutional requirements. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to participation.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Participation was voluntary, anonymous, and respondents were informed about the purpose of the research and their right to withdraw at any time.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Due to privacy and ethical considerations, the dataset is not publicly accessible.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank the international students of VILNIUS TECH for their participation in the study and the university administration for help in distributing the survey. The authors also acknowledge the support of colleagues who provided valuable feedback during the preparation of the manuscript. The authors acknowledge the use of ChatGPT (OpenAI) (Mar 14 version) [Large language model] as a language-editing and proofreading tool to improve clarity, grammar, and academic wording in the English text. All conceptual, methodological, analytical, and interpretative decisions were made exclusively by the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EU | European Union |

| LR | Language Requirement |

| VILNIUS TECH | Vilnius Gediminas Technical University |

References

- Environmental Protection Institute. United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://aai.lt/jungtiniu-tautu-darnaus-vystymosi-tikslai/ (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Bradley, L.; Lindström, N.B.; Hashemi, S.S. Integration and Language Learning of Newly Arrived Migrants Using Mobile Technology. J. Interact. Media Educ. 2017, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission (EC). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament. The Council. The European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. European Agenda for the Integration of Third-Country Nationals 2011. Available online: http://eurlex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:52011DC0455:EN:NOT (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Blommaert, J.; Verschueren, J. Debating Diversity. Analysing the Discourse of Tolerance; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan-Brun, G.; Mar-Molinero, C.; Stevenson, P. Testing regimes: Introducing cross-national perspectives on language, migration and citizenship. In Discourses on Language and Integration 2009; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam, Netherlands; Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2009; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörnyei, Z.; Ushioda, E. Teaching and Researching: Motivation, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, R.C.; Lalonde, R.N.; Moorcroft, R. The role of attitudes and motivation in second language learning: Correlational and experimental considerations. Lang. Learn. 1985, 35, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörnyei, Z. The Psychology of the Language Learner: Individual Differences in Second Language Acquisition; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA; London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Center of Registers. Available online: https://www.registrucentras.lt/atviri-duomenys-ir-statistika/gyventoju-skaicius-pagal-apskritis (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Teisės Garantas. Available online: https://tga.lt/lt/stiprinama-lietuvoje-studijuojanciu-uzsienieciu-studentu-kontrole/ (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Choi, T. The impact of the “Teaching English through English” policy on teachers and teaching in South Korea. Curr. Issues Lang. Plan. 2014, 16, 201–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, E. The Ecology of Language; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Steffensen, S.; Fill, A. Ecolinguistics: The state of the art and future horizons. Lang. Sci. 2014, 41, 6–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fill, A.F.; Penz, H. The Routledge Handbook of Ecolinguistics; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Penz, H.; Fill, A. Ecolinguistics: History, today, and tomorrow. J. World Lang. 2022, 8, 232–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffensen, S.V.; Kramsch, C. The Ecology of Second Language Acquisition and Socialization. In Language Socialization, 3rd ed.; Duff, P.A., May, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R. Motivation and Second Language Acquisition: The Socio-Educational Model; Peter Lang Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero, M. Motivation in Second Language Learning: A Historical Overview and Its Relevance in a Public High School in Pasto, Colombia. HOW 2015, 22, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R.; Lambert, W.E. Attitudes and Motivation in Second-Language Learning; Newbury House Publishers Rowley: Mass, UK, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, R.C. Social Psychology and Second Language Learning: The Role of Attitudes and Motivation; Edward Arnold: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csizér, K.; Dörnyei, Z. The internal structure of language learning motivation and its relationship with language choice and learning effort. Mod. Lang. J. 2005, 89, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, C.; Ming, Z.; Chen, L. The study of student motivation on English learning in Junior middle school.—A case study of No.5 middle school in Gejiu. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2013, 6, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R.C.; MacIntyre, P.D. An instrumental motivation in language study: Who says it isn’t effective? Stud. Second. Lang. Acquis. 1991, 13, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, S.; Jin, H.; You, Z.; Wang, J. Motivation and Its Effect on Language Achievement: Sustainable Development of Chinese Middle School Students’ Second Language Learning. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilnius Tech. Available online: https://vilniustech.lt/vilnius-tech-naujienu-portalas/naujausios/naujausios/vilnius-tech-tarptautiskiausias-universitetas-lietuvoje/246872?nid=373468 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Kiškytė, M. Demands of the Employers for Foreign Language Skills in Job Advertisements in Three Baltic Countries. Soc. Tyrim. 2023, 46, 24–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Downing, K. Determinants of international students’ adaptation: Examining effects of integrative motivation, instrumental motivation and second language proficiency. Educ. Stud. 2011, 38, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.