Abstract

Fiscal capacity is a core dimension of state capacity. Effective oversight of public expenditure is therefore essential for fiscal sustainability, a foundational element of sustainable development. As local government debt has steadily increased in China, participatory budgeting has emerged as an innovative mechanism for citizens to exercise such oversight and influence fiscal decisions. Our paper examines the effect of participatory budgeting on local government debt in China. Using a panel dataset covering 242 Chinese cities from 2013 to 2022, we examine the effect of participatory budgeting adoption on the scale of explicit government debt. Our results show that adopting participatory budgeting moderately reduces local government debt levels. Further mechanism analysis indicates that participatory budgeting operates through two channels. First, by enhancing budgetary transparency, it strengthens public scrutiny, which in turn disciplines government borrowing. Second, it redirects public spending toward welfare sectors like education and health, thereby crowding out large, debt-financed investment projects. Our findings contribute to the literature on participatory budgeting, fiscal democracy, and bottom-up accountability in public finance. The results suggest that participatory budgeting can be an effective policy tool for improving fiscal discipline and curbing government debt risks, ultimately fostering more sustainable and equitable local governance.

1. Introduction

The rapid expansion of local government debt has posed a significant challenge to China’s fiscal stability and sustainable development. Between 2017 and the end of 2024, the outstanding balance of local government debt in China surged at an average annual rate of 16.35%, reaching a staggering 47.54 trillion RMB (6.69 trillion USD)—equivalent to approximately 35.24% of the nation’s GDP. This rapid debt accumulation creates serious financial risks for local governments. It also challenges the very foundation of fiscal sustainability, a core concern for effective governance and policymaking worldwide.

A substantial body of literature has explored the causes of this rapid debt expansion. One dominant strand of research points to a set of interconnected political and institutional incentives, including the pressures of fiscal decentralization, promotion-seeking local officials who borrow for growth [1], and the issue of soft budget constraints [2,3]. Other scholars have highlighted economic and policy-driven factors, such as the structural consequences of the 1994 tax-sharing system reform [4] and the substantial capital demand for infrastructure-led development [5].

While established explanations remain important, their predominantly top-down perspective tends to overlook a fiscal governance element that has gained global traction: direct citizen engagement. In response to mounting global crises of debt and legitimacy, bottom-up mechanisms aimed at strengthening accountability and improving public service delivery have attracted significant scholarly and practical attention [6,7,8,9,10]. Among these, participatory budgeting is a prominent example, particularly as illustrated by China’s ongoing experiments with citizen engagement in fiscal governance. As a democratic process, it empowers ordinary citizens to deliberate on and directly influence the allocation of public resources.

Theoretically, participatory budgeting can enhance fiscal discipline through two primary channels. First, participatory budgeting introduces bottom-up oversight. When citizens become active participants in the budget process, they serve as watchdogs, increasing budget transparency and holding officials accountable for their fiscal decisions [10,11,12]. This public scrutiny can constrain the ability of local officials to accumulate debt irresponsibly. Second, it aligns public spending with citizen priorities [13,14,15,16]. This may shift budgets away from debt-fueled, low-value projects and toward essential public services.

As Frederickson argues, traditional administration has overemphasized “efficiency” and “economy,” often neglecting “social equity” as a core value [17]. Within this framework, participatory budgeting is not only a transparency tool but a distributive instrument that could reshape the logic of budget allocation [18]. By giving citizens both a voice and a vote, participatory budgeting puts social justice into practice. It helps correct the unequal distribution often found in traditional growth models, ensuring that public resources effectively reach disadvantaged groups [18,19].

Given these mechanisms, we hypothesize that the adoption and implementation of participatory budgeting can be an effective tool for strengthening fiscal discipline, thereby reducing local government debt.

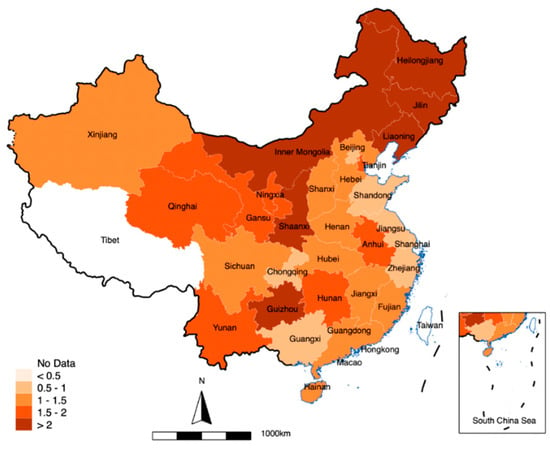

Despite this theoretical promise, empirical evidence on the relationship between participatory budgeting and fiscal outcomes in the Chinese context remains scarce. This study aims to fill this gap. We make two primary contributions. First, unlike prior work that has focused on single-city case studies [20,21,22,23,24], our study provides a large-scale empirical test of whether participatory budgeting adoption reduces local government debt in China. To do so, we use a panel dataset of Chinese prefecture-level cities from 2013 to 2022, a period marked by the rapid accumulation of local government debt (as illustrated in Figure 1). Second, we go beyond asking if participatory budgeting works and explore how it works by testing the causal mechanisms of fiscal transparency and expenditure reallocation. Our analysis takes advantage of the significant variation in both debt levels and participatory budgeting adoption across Chinese cities during this period, which offers a unique opportunity to systematically evaluate its impact.

Figure 1.

Map of Government Debt Distribution in 2022.

2. Theory and Hypothesis

This study incorporates participatory budgeting (PB), an institutional mechanism for public participation, into the analysis of local government debt management. From the perspectives of budgetary democracy and fiscal supervision, we examine its impact on the scale of local government debt and the underlying causal mechanisms. This approach aligns with established theories suggesting that external oversight institutions, such as people’s congresses and the public, can enhance debt management performance and improve the overall stability of the fiscal system [25].

In theory, moderate government debt serves as an essential counter-cyclical tool and a conventional fiscal instrument consistent with the principle of intergenerational equity [25,26]. However, within China’s unique “pressure-based” governance system, local officials face intense performance evaluations heavily weighted toward tangible economic growth [27,28]. This incentive structure encourages extensive borrowing for development, making a “debt-driven” growth model a rational choice for local officials’ career advancement. This process often leads to excessive borrowing and a weakening of fiscal discipline, resulting in the accumulation of significant debt risks. Over-leveraging not only constrains future fiscal and monetary policy space but also amplifies potential risks due to the inefficient allocation of capital. Consequently, if economic growth slows, repayment pressures could trigger a fiscal or financial crisis, undermining long-term sustainable development. Strengthening the scrutiny and supervision of government debt has therefore become a critical challenge for national governance [29].

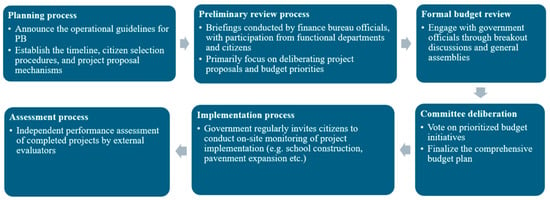

Under the current system, China’s local government debt oversight relies primarily on internal control mechanisms, such as state audits and inspections [25,30]. While these top-down measures provide a degree of vertical constraint, they function as a form of “self-supervision,” which is prone to conflicts of interest and institutional inertia. Participatory budgeting, as a major institutional innovation, offers an alternative solution. By directly involving citizens in the formulation, execution, and oversight of public budgets, it opens an external channel for scrutinizing debt issuance and monitoring the use of borrowed funds (as illustrated in Figure 2) [10,31,32]. This approach represents a shift from conventional debt management to an inclusive and collaborative governance framework and contributes to mitigating local debt risks and fostering sustainable development [33,34].

Figure 2.

The process of Participatory Budgeting in China.

2.1. The Effect of Participatory Budgeting on Local Government Debt

Participatory budgeting originated in the late 1980s in Porto Alegre, Brazil, and has since been widely recognized for its effectiveness in enhancing transparency, improving public services, and deepening grassroots democracy [35,36,37]. In the 21st century, it was introduced to China as a governance reform, with programs launched in cities across Zhejiang, Guangdong, and Shanghai [38,39,40]. While definitions of participatory budgeting vary, they converge on the principle of citizen empowerment. UN-Habitat, for instance, offers a broad definition that includes any process where citizens can influence at least part of a government’s budget, such as through public lobbying, resident hearings, or project-specific referendums [41]. More specifically, Wampler (2012) argues that participatory budgeting’s core function is to integrate citizens into the decision-making process, empowering them to set social policy priorities, allocate public resources, and monitor expenditures [18].

The core of participatory budgeting is to shift away from the traditionally closed, top-down model of budget formulation dominated by government agencies. Through institutionalized arrangements such as budget hearings, resident councils, and project-level voting, participatory budgeting provides ordinary citizens the rights to information, participation, expression, and oversight concerning the allocation and use of public budgets [31,42]. In essence, participatory budgeting is a practical application of the concept of budgetary democracy, designed to enhance the public nature of fiscal expenditures and the accountability of government actions [13,43]. However, scholars also caution against the limitations of its implementation. Wampler (2012) and Hong (2015) warns of “pseudo-PB,” where participation remains symbolic to promote legitimacy without essential power transfer, while other studies note that broad inclusiveness can sometimes compromise decision-making efficiency or lack the necessary technical expertise [18,44].

To understand how participatory budgeting affects local government debt, it is necessary to examine the institutional context driving fiscal expansion. Existing literature identifies the causes of debt in the specific political and fiscal incentives facing local officials. Under China’s system of “promotion tournaments,” officials compete for promotion through economic growth [1,27,28]. This competition creates a tendency for local officials toward capital-intensive infrastructure projects that are often financed through debt [5,45]. This behavior is also exacerbated by soft budget constraints [2,3]. As Ong (2012) and Rodden (2002) argue, when central governments cannot credibly commit to withholding bailouts, local governments anticipate a safety net that encourages fiscal indiscipline and over-borrowing [46,47]. This structural pressure incentivizes officials to prioritize visible short-term achievements over long-term fiscal sustainability [48,49].

The introduction of participatory budgeting addresses this issue. First, participatory budgeting mitigates information asymmetry surrounding public finance. It requires the government to disclose key information, such as budget drafts, project plans, and funding sources (including debt financing plans), in an accessible and understandable format, while providing platforms for public inquiry and deliberation [50,51,52]. In this process, the scale, rationale, cost, and repayment schedule of local government borrowing are placed under public scrutiny. This approach raises the political costs and operational difficulties of engaging in excessive or hidden borrowing.

Second, participatory budgeting builds a “bottom-up” accountability mechanism that counters the growth-oriented incentives of the cadre evaluation system. As Mo and Zhang (2023) and Ma and Hou (2009) suggest, establishing accountability in non-electoral regimes is possible through procedural reforms that impose checks on administrative power [53,54]. By allowing citizens to directly influence the allocation of fiscal resources, PB introduces a form of societal accountability. Studies show that ordinary citizens tend to be more fiscally cautious than officials, favoring lower government borrowing [55]. Other research finds that, unlike government officials who often prefer large-scale infrastructure projects, the public prioritizes services that directly affect their daily lives, such as education, healthcare, and community facilities [42,43,56]. These projects usually involve smaller investments and rely less on debt. As more budget decisions shift from officials to citizens, spending is likely to shift toward social welfare, reducing dependence on debt-driven growth.

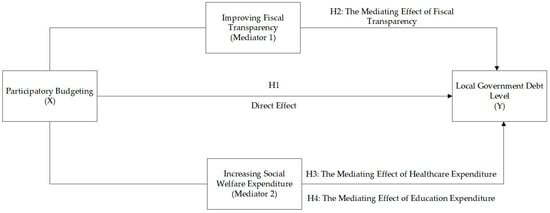

In summary, participatory budgeting constrains the borrowing behavior of local governments through the dual channels of information and power. It alters the unilateral decision-making pattern of traditional governance, placing debt under public oversight and constraining the tendency toward excessive borrowing at its source. Based on this analysis, we present our theoretical framework in Figure 3 and propose:

Figure 3.

Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses.

H1:

The implementation of participatory budgeting helps to reduce local government debt ratios.

2.2. Improving Fiscal Transparency as a Mediating Mechanism

The concept of fiscal transparency emerged from governance reforms in the late 20th century and has been refined through practice across numerous countries. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) defines fiscal transparency as the “comprehensiveness, clarity, reliability, timeliness, and relevance of public reporting on the past, present, and future state of public finances [57].” As a budgetary practice, participatory budgeting is built upon the active engagement of citizens in decisions that influence resource allocation. Local governments are compelled to translate complex budgetary documents into accessible materials. This process reduces information asymmetry by transforming internal, expert knowledge into a public good. Supporting this view, scholars have found that the implementation of participatory budgeting has a positive effect on fiscal transparency, accountability, and trust in government. Drawing on interview data from New York, Swaner (2017) finds that participatory budgeting enhances residents’ understanding of complex public finances and strengthens the legitimacy of local government [58]. A World Bank report suggests that increased budget disclosure and participation are consistently associated with improvements in budget quality and governance performance [59]. Experiences in several European countries also confirm a positive impact on fiscal transparency, government accountability, and trust among citizens [60,61,62,63].

A key question is how fiscal transparency, once improved, promotes fiscal discipline. The primary channel is political accountability. Greater transparency allows public opinion to more effectively monitor the actions of local officials. It increases the visibility of borrowing decisions, making fiscal irresponsibility easier to detect and penalize, whether through public pressure or by superior authority [10]. Our argument is consistent with the literature on direct democracy, which demonstrates that empowering citizens with direct control over fiscal matters, such as through referendums, leads to greater fiscal discipline [64]. Participatory budgeting, while a ‘softer’ form of intervention, operates on a similar principle of citizen oversight.

Milesi-Ferretti (2004) [65] considers a political system with fiscal rules where transparency is increased to meet international treaty obligations. They argue that greater transparency raises the probability of detecting fiscal manipulation, which in turn helps to limit government debt within reasonable limits. Analyzing 19 OECD countries, Alt and Lassen (2006) provide empirical evidence that higher fiscal transparency is associated with lower government debt [66]. Similarly, using a budget management index for 46 African countries, Gollwitzer (2011) finds a strong correlation between high fiscal transparency and low government debt [67].

However, we recognize that the bottom-up oversight does not operate in a vacuum. As Ma and Hou (2009) [54] argue, effective financial accountability requires both administrative and legislative controls. They posit that external oversight can only function effectively if the government establishes internal controls and binding budgetary rules.

Under the Chinese context, Xiao et al. (2015) examine the link between transparency and debt through both theoretical and empirical lenses [68]. They argue that under China’s “promotion tournament” incentive structure, the absence of fiscal transparency incentivizes local officials to over-invest using debt. Their empirical results confirm a significant negative relationship, suggesting that enhancing transparency may constrain the borrowing behavior of local governments and mitigate fiscal risks. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

H2:

Participatory budgeting reduces local government debt level by improving fiscal transparency.

2.3. Increasing Social Welfare Expenditure as a Mediating Mechanism

Participatory budgeting promotes fiscal transparency and reallocates spending at the same time. Therefore, participatory budgeting may also constrain local government debt by reshaping fiscal priorities. This mechanism works because government officials and the public often have different spending preferences. In China’s governance system, local officials are under pressure to achieve economic growth, as their careers often depend on it [27,28]. The pursuit of efficiency drives them to invest in large-scale, capital-intensive infrastructure projects that yield immediate and visible results. As Frederickson argues, focusing solely on efficiency often comes at the expense of social equity, skewing resources toward projects that offer immediate gains rather than long-term public benefit [19].

Citizens, however, tend to prioritize services that directly improve their quality of life, such as education, healthcare, and social security [69]. Participatory budgeting helps correct this misalignment. It shifts some decision-making power from officials to the public, ensuring budget allocations better reflect citizen priorities. Empirical evidence from around the world supports this view. For example, studies in Brazil show that participatory budgeting directs more funds to health and sanitation, which are high priorities for the public [43]. Research from other Brazilian municipalities confirms that governments with participatory budgeting programs spend a higher proportion of their budgets on health and education [42]. Similarly, analysis of Lisbon’s Participatory Budget reveals that citizen-driven resource allocation can redirect public investment toward sustainability and quality-of-life improvements, challenging the conventional emphasis on large-scale infrastructure [70]. This pattern holds in other countries as well. In South Korea, participatory budgeting led to more funding for crime-monitoring cameras in low-income areas [71], while a study in New York City found that participatory budgeting adoption districts spent more on schools and public housing [31].

We argue that this shift toward social welfare spending reduces debt not by generating new revenue, but by altering the financing structure of public expenditure through a “crowding-out” effect. The reason is that social welfare and infrastructure projects are financed differently. Social welfare spending on items like salaries and subsidies is recurrent and typically funded from the general budget, not from borrowing. In contrast, large-scale infrastructure projects are capital-intensive and serve as the primary drivers of local debt expansion [72,73].

Since government budgets are finite, the prioritization of social equity “crowds out” the fiscal space available for debt-driven expansion. When participatory budgeting enables citizens to redirect resources toward immediate welfare needs, it constrains the discretionary funds available for officials to launch new, capital-intensive infrastructure projects [74,75]. By reallocating funds from “high-leverage” investment sectors to “low-leverage” public service sectors, participatory budgeting effectively lowers the demand for new borrowing. This logic leads to our next hypotheses, which identify social welfare spending as a key mediator. We use education and healthcare expenditures to proxy citizen preferences:

H3:

Participatory budgeting reduces local government debt by increasing the share of public expenditure allocated to healthcare.

H4:

Participatory budgeting reduces local government debt by increasing the share of public expenditure allocated to education.

3. Research Design

Our empirical analysis focuses on prefecture-level cities in China. This administrative level is not only central to government performance evaluation but also represents a critical arena where the implementation and impact of participatory budgeting (PB) can be observed. Our primary objective is to examine the causal effect of participatory budgeting on local government debt. To do so, we construct a panel dataset covering 242 Chinese cities from 2013 to 2022 and employ a two-way fixed effects model as our core analytical framework.

This approach allows us to test our main hypothesis (H1) that PB reduces local government debt. Furthermore, it enables us to explore the mediating roles of fiscal transparency (H2) and shifts in public service expenditure (H3 & H4), providing a comprehensive analysis of the channels through which participatory budgeting operates.

To estimate the direct impact of participatory budgeting on local government debt, we employ a two-way fixed effects model. This approach effectively controls for any unobserved, time-invariant city characteristics (e.g., political culture, geography) and nationwide secular trends or shocks that could confound our results. A Hausman test confirmed the suitability of the fixed effects model over a random effects specification (p < 0.05).

Our baseline model is specified as follows:

where Debtit is the debt ratio for city i in year t. PBit is a dummy variable equal to 1 if city i has implemented participatory budgeting in year t, and 0 otherwise. ControlVarit is a vector of time-varying control variables as detailed in 3.4. μi represents city-fixed effects, and λt represents year-fixed effects. εit is the idiosyncratic error term.

Our primary interest is in the coefficient β1. A statistically significant and negative β1 would support H1, indicating that the adoption of PB is associated with a reduction in local government debt levels.

To test the mechanisms through which participatory budgeting influences debt (H2–H4), we follow the causal steps approach. This involves estimating two additional models. First, we examine whether PB has a significant effect on our proposed mediators, namely fiscal transparency and social welfare expenditures.

Second, we include both PB and the mediator in the original model to assess whether the mediator explains part of PB’s effect on debt.

A mediation effect is confirmed if: (1) α1 in Equation (2) is statistically significant; and (2) δ2 in Equation (3) is significant, while the coefficient of PB, δ1, decreases in magnitude compared to β1 in Equation (1). This would indicate that the mediator (e.g., fiscal transparency) is a pathway through which PB affects government debt.

To address potential endogeneity concerns and ensure the robustness of our baseline results, we conduct a series of robustness checks. First, we replace the dependent variable with the debt-to-GDP ratio to mitigate potential measurement bias. Second, acknowledging that the effects of participatory budgeting may not be immediate, we substitute the core independent variable with its one-year lag (L.pb). Third, to account for the influence of outliers, we winsorize all continuous variables at the 1% and 99% levels. Finally, to ensure our results are not driven by a specific group of economically or administratively unique municipalities, we re-estimate the model after excluding all provincial capitals and centrally administered municipalities. Consistent findings across these different specifications would strengthen the validity of our conclusions. The variable definitions and measurements are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Variable Definitions and Measurement.

3.1. Dependent Variable

Our primary dependent variable is the local government debt ratio. We define this as the stock of outstanding government debt divided by comprehensive fiscal capacity. This measurement choice is based on the institutional context of China. The 2015 revision of the Budget Law introduced a formal “self-issuance and self-repayment” framework for local government bonds [76,77]. This reform initiated a transition from implicit debt financing toward explicit and standardized instruments [77].

The numerator of our ratio is the total stock of outstanding debt. It comprises both general bonds, issued for public welfare projects, and special-purpose bonds, allocated for projects with revenue-generating potential [78]. We collect these data from the official disclosures of municipal finance departments.

We exclude implicit government debt, particularly that from local government financing vehicles (LGFVs), for two reasons. First, reliable and comprehensive data on implicit debt are not available at the prefectural city level. Second, following the 2015 reform, standardized bonds became the dominant financing channel, diminishing the relative importance of LGFVs [77].

For the denominator, we follow Diao (2017) and measure comprehensive fiscal capacity as the sum of general public budget revenue and government fund budget revenue [79]. This ratio thus captures the burden of debt stock relative to a locality’s repayment capacity.

3.2. Independent Variable

Our key independent variable is the implementation of Participatory Budgeting (PB). We measure this using a binary indicator based on a dataset from the Center for Public Performance Evaluation at South China University of Technology. This dataset tracks the adoption of participatory budgeting initiatives across Chinese prefecture-level cities over many years. It provides rich, project-level information. These details include the initial year of PB adoption, project titles, funding allocations, and specific locations within a city. A city is defined as having implemented participatory budgeting if it convened a formal “public budget deliberation meeting” in a given year. These meetings represent a primary institutional form of PB in our study’s context.

For our city-year panel analysis, a city is coded as having implemented participatory budgeting (assigned a value of 1) if it has an active program in a given year. Cities without such a program are assigned a value of 0. This variable construction forms the basis of our empirical strategy, which aims to identify the relationship between PB adoption and local government debt.

3.3. Mediating Variables

Our first mediating variable is fiscal transparency, which proxies the oversight mechanism. We measure this using the China Local Government Fiscal Transparency Index. This index is compiled annually by Tsinghua University, and our data span the years 2013 to 2022. This index evaluates municipalities on several key dimensions of fiscal openness. These include the disclosure of budget documents, the comprehensiveness of fiscal information, the accessibility of data, and the timeliness of reporting [80]. The index is a widely used and objective benchmark for fiscal openness in China.

Our second and third mediating variables test the preference alignment channel, through which participatory budgeting may redirect public funds toward services highly valued by citizens. Education and healthcare are fundamental components of local public service delivery and consistently rank among the highest priorities for residents. They thus serve as critical indicators of a government’s responsiveness to public demand.

Accordingly, we construct two variables to capture these shifts in budgetary priorities. The first, Education Expenditure Share, is defined as the ratio of local government spending on education to its total general public budget expenditure. The second, Healthcare Expenditure Share, represents the ratio of local government spending on healthcare to the same total expenditure base. The data for these expenditure categories are drawn from the annual fiscal reports disclosed by each municipal finance department.

3.4. Control Variables

To isolate the effect of PB on local government debt, our model includes a set of time-varying control variables that account for city-specific characteristics that may confound the relationship. We group these into three categories.

First, to control for economic development and structural factors, we include GDP per capita and the Urbanization Rate. GDP per capita captures the overall economic output and wealth of a city, which directly influences its fiscal capacity and creditworthiness. The Urbanization Rate, measured as the proportion of the urban population to the total population, accounts for differences in economic structure and public service demands between urban and rural areas.

Second, we incorporate key fiscal indicators. Tax Revenue per capita reflects the government’s ability to generate its own revenue. We also include the Fiscal Self-Sufficiency Rate, defined as the ratio of a city’s general public budget revenue to its expenditure. This variable is a key indicator of fiscal health and a city’s reliance on transfer payments or debt financing.

Third, we control for demographic scale and specific expenditure pressures. We use the natural logarithm of the total population to account for city size. Furthermore, to proxy for demand-side pressures on the budget in two major public service sectors, we include the number of doctors and the number of students in primary and secondary schools.

All control variable data are collected from the China City Statistical Yearbook and the statistical yearbooks published by individual prefecture-level cities.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Descriptive Results

Table 2 provides descriptive statistics for the local government debt ratio, PB, mediation variables and various control variables. The average debt ratio of 89.23 suggests that, on average, local governments have a debt that is about 89.23% of their comprehensive fiscal capacity. The standard deviation (SD) of 95.92 shows significant variation in the debt levels across different cities in China.

Table 2.

Summary Statistics.

4.2. Regression Analysis

Table 3 presents the baseline regression results for the effect of participatory budgeting on local government debt. Our analysis proceeds by sequentially including fixed effects and control variables to assess the stability of the coefficient. Our preferred specification is reported in Column (4), which includes the full set of economic and fiscal controls, as well as both city and year fixed effects.

Table 3.

Basic Regression Results.

The central finding of this paper is evident in this specification. The coefficient of our variable of interest, Participatory Budgeting (PB), is −0.089 and is statistically significant at the 1% level. This result is consistent with our primary hypothesis (H1) and suggests a mild, negative association between the adoption of participatory budgeting and the scale of local government debt. The inclusion of city fixed effects controls for any time-invariant local characteristics, such as geographical location or local political culture. Similarly, the inclusion of time fixed effects absorbs the influence of common macroeconomic shocks or nationwide policy changes that affect all municipalities.

The magnitude of the coefficient is not only statistically significant but also economically meaningful. The estimate of −0.089 implies that, holding all other factors constant, municipalities that adopt participatory budgeting, on average, exhibit a local government debt ratio that is 9 percentage points lower than those that do not.

The control variables included in the model generally exhibit the expected signs. For instance, higher GDP per capita and greater fiscal self-sufficiency are associated with lower debt ratios, consistent with the notion that stronger economic and fiscal fundamentals reduce the need for excessive borrowing. The coefficients for other demographic and public service variables, such as Population, Urbanization rate, and Healthcare level, are not statistically significant in our model. This is plausible, as their effects may be absorbed by the more direct fiscal and economic indicators, as well as the city-fixed effects.

4.3. Robustness Check

To ensure the robustness of our baseline findings, we conduct a series of tests, with the results presented in Table 4. These tests examine whether our findings depend on specific variable measurements, sample selections, or the influence of outliers.

Table 4.

Robustness Check.

First, we employ alternative measures for our key variables. In our baseline model, the dependent variable is defined as the ratio of outstanding debt to the comprehensive fiscal capacity of the local government. In Column (2) of Table 4, we replace this with a more conventional measure: the ratio of outstanding debt to local GDP. The coefficient of Participatory Budgeting (PB) is −0.035 and remains statistically significant at the 1% level. This indicates that the implementation of participatory budgeting is associated with a lower level of government debt, regardless of whether debt burden is scaled by fiscal capacity or economic output. In Column (3), we substitute the PB variable with its one-year lag (L.PB). This specification not only accounts for potential time lags in policy effectiveness but also helps mitigate concerns about contemporaneous reverse causality. The coefficient of the lagged PB is −0.078, significant at the 1% level. The slightly smaller magnitude of the coefficient is consistent with the expectation that the fiscal impact of PB may diminish over time.

Second, we examine the sensitivity of our results to outliers and specific subsamples. In Column (4), we address the potential influence of extreme values by winsorizing the dependent variable and all major continuous control variables at the 1st and 99th percentiles. The coefficient of PB is −0.091, which is very close to our baseline estimate of −0.089 and remains significant. Furthermore, sub-provincial cities and municipalities directly under the central government may exhibit different fiscal behaviors due to their distinct administrative status, economic scale, and potential for special treatment from the central government. We therefore exclude these cities from the sample in Column (4). The result shows that the coefficient of PB remains −0.081 and is significant at the 5% level.

The results across all these alternative specifications in Table 4 consistently show a significant and negative relationship between participatory budgeting and local government debt, supporting our hypothesis (H1) that PB adoption is associated with lower government debt level.

Finally, we address potential concerns regarding endogeneity, specifically whether fiscally healthy cities are simply more likely to adopt participatory budgeting. Evidence from our fieldwork and the existing literature suggests that adoption is frequently driven by political agency rather than fiscal conditions. Research by He (2019) and Zhao (2020) highlights the role of “policy entrepreneurs”, often officials within local People’s Congresses, who initiate reforms to enhance governance legitimacy [23,39]. This political motivation suggests that the adoption of participatory budgeting is an exogenous shock driven by leadership innovation, mitigating concerns that our results are solely driven by reverse causality.

4.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

While our main model controls for city-level characteristics through fixed effects, the impact of PB may vary depending on the broader regional political and economic context in which cities are situated. Different regions in China are at vastly different stages of economic development and possess distinct institutional environments, which could moderate the effectiveness of governance innovations like PB. We divide our dataset based on the State Council’s official four-part classification (Eastern, Central, Western, and Northeastern China) and estimate our primary model for each subsample.

The results presented in Table 5 reveal notable regional heterogeneity. The effect of participatory budgeting on debt level is statistically significant and economically substantial in the Eastern (−0.121), Western (−0.091), and Central (−0.087) regions. In contrast, the coefficient for the Northeastern region, while negative, is not statistically significant.

Table 5.

Heterogeneous Effects of PB on Local Government Debt by Region.

This pattern can be interpreted through the lens of regional variations in civil society development and economic structure. In the economically advanced Eastern region, a more active civil society and higher public demand for government accountability may enhance the transparency-enhancing effects of participatory budgeting, making it a useful tool for fiscal discipline. In the developing Central and Western regions, which face significant pressure for public investment, participatory budgeting’s role in shifting expenditures toward welfare and away from potentially inefficient, debt-fueled infrastructure projects is particularly salient. The insignificant effect in the Northeast may reflect the region’s distinct political economy, characterized by the dominance of state-owned enterprises and different governance traditions, which may limit the effectiveness of bottom-up accountability mechanisms.

4.5. Mediation Analysis Result

To test the mechanisms through which participatory budgeting (PB) influences local government debt, we conduct a formal mediation analysis. We examine three hypothesized pathways first outlined in our theory section: fiscal transparency (the oversight channel, H2), education expenditure share (a preference alignment channel, H3), and healthcare expenditure share (a second preference alignment channel, H4). Our approach follows the causal steps framework, which estimates the indirect effect of PB on debt that operates through each of these mediators [81,82]. The detailed results of this analysis are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Mechanism analysis result.

First, we examine the role of fiscal transparency. Column (1) shows that participatory budgeting has a significant positive effect on our fiscal transparency index (β = 1.01, p < 0.01). Column (2) then includes both participatory budgeting and fiscal transparency in the regression for local government debt. The coefficient for fiscal transparency is significantly negative (β = −0.11, p < 0.01), while the coefficient for participatory budgeting remains negative but statistically insignificant (β = −0.07, p > 0.10). This pattern indicates that fiscal transparency functions as a full mediator. In other words, participatory budgeting reduces government debt directly by enhancing fiscal transparency.

Next, we investigate the role of expenditure structure, focusing on education. Column (3) shows that participatory budgeting increases the share of government expenditure allocated to education (β = 0.06, p < 0.01). In Column (4), the education expenditure share is itself negatively associated with debt (β = −0.39, p < 0.05). The coefficient for participatory budgeting remains significant at the 5% level. This suggests that the education expenditure share acts as a partial mediator. Participatory budgeting appears to lower debt by shifting public funds toward human capital investment.

Finally, we test the channel of healthcare expenditure share. Unexpectedly, in Column (5), we find that the effect of participatory budgeting on healthcare expenditure is not statistically significant. Column (6) further shows that the healthcare expenditure share does not have a significant relationship with government debt. Therefore, we find no evidence to support healthcare expenditure as a mediating pathway.

A plausible explanation for this is the distinct nature of healthcare governance and budgeting. First, we contend that healthcare budgeting is a highly technical process, guided by medical professionals and technocrats rather than direct public deliberation. Decisions about resource allocation require specialized knowledge, such as choices about investments in medical technology or funding for specific programs. Consequently, fiscal authorities may be more inclined to heed the requests of health departments. They are likely more cautious about incorporating public opinion that lacks the necessary technical context.

Second, healthcare budgets may exhibit greater rigidity compared to other public services. A substantial portion of spending is often non-discretionary because it is allocated to fixed costs. These costs include long-term service contracts and the maintenance of existing hospital infrastructure, etc. This situation may leave limited fiscal space for the kind of reallocation that participatory budgeting can influence.

Therefore, it is plausible that participatory budgeting is effective in areas where public preferences can directly inform policy, for example, by enhancing transparency and prioritizing education. Its influence, however, appears limited in the more specialized and rigid domain of healthcare.

Adopting the method of Krull and MacKinnon (2001), we decompose the overall impact of participatory budgeting on local government debt into its direct and indirect pathways [83]. The magnitude of the indirect effect is quantified by multiplying two specific path coefficients: (a) the influence of participatory budgeting on the mediator, and (b) the subsequent influence of the mediator on local government debt. The proportion of the total effect attributable to each channel is then calculated. Table 7 summarizes these findings.

Table 7.

Mediation Analysis Results.

The analysis reveals that the fiscal transparency channel accounts for a meaningful portion of the total effect. The indirect effect operating through transparency is −0.107, explaining approximately 60.1% of the debt reduction. This underscores the important role of bottom-up scrutiny in fostering fiscal discipline. The expenditure-shifting mechanism, specifically through education, shows it has an indirect effect of −0.024 and explains a substantial 23.8% of the total effect. Our analysis demonstrates that PB reduces the local government debt level through the dual pathways of heightened scrutiny and preference alignment.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study examines the effect of participatory budgeting on the rapid accumulation of local government debt in China, a critical challenge to the nation’s long-term fiscal sustainability. Using a panel dataset of 242 Chinese cities from 2013 to 2022, we find that the adoption of PB is associated with a statistically significant reduction in local government debt ratios. The estimated coefficient implies a reduction of approximately 9%, an effect we interpret as economically meaningful but moderate. We further find that this effect operates through two primary channels. First, participatory budgeting enhances fiscal transparency, thereby strengthening public scrutiny over borrowing. Second, it redirects public expenditure toward social welfare sectors like education. This reallocation reduces debt not by generating new revenue but by altering the financing structure of local expenditure. By prioritizing social welfare services that are paid for by regular government income, participatory budgeting crowds out the fiscal space for capital-intensive and debt-driven infrastructure projects.

We acknowledge that the direct fiscal share of participatory budgeting projects is often small relative to the total local budget. However, we argue that participatory budgeting generates a significant “spillover effect” on the broader fiscal behavior of local governments. As noted by Shybalkina and Bifulco (2019), the impact of participatory budgeting extends beyond specific project allocations to influence officials’ decisions on non-PB discretionary funds [14]. This “signaling effect” may constrain the impulse for borrowing across the entire budget, not just within the participatory budgeting allocation. Furthermore, Wampler (2012) suggests that participatory budgeting creates “waves of influence,” where participants carry their oversight skills and demands for accountability into other policy arenas [18].

Our findings offer several contributions to the existing literature. First, we extend the research on participatory budgeting by providing evidence of its impact on a macro-fiscal outcome. While much of the participatory budgeting literature focuses on micro-level impacts like service delivery or citizen satisfaction [31,43], our study shows that its effects scale up to influence municipal fiscal health. Second, our study contributes to the understanding of bottom-up accountability in public finance, particularly within the context of China’s local government debt. The extensive literature on the determinants of local debt has overwhelmingly focused on top-down factors, such as career incentives for officials and intergovernmental fiscal arrangements [1,2,3,5]. Ma and Hou (2009) argue that while challenging, “accountability without election” is feasible in non-electoral contexts through procedural reforms [54]. Our findings support this view, suggesting that participatory budgeting functions as a form of “societal accountability” that compensates for the lack of electoral mechanisms. By institutionalizing public participation, participatory budgeting enhances transparency and introduces necessary social equity values, which help moderate administrative discretion and encourage more prudent use of fiscal resources.

The results carry important policy implications. For local governments in China seeking to mitigate fiscal risks, our study suggests that expanding and institutionalizing participatory budgeting can be a possible option. Governments should institutionalize participatory processes through fiscal legislation and digital transparency tools that mandate public disclosure and feedback loops. Participatory budgeting is most effective when embedded within a system that enforces hard budget constraints and ensures two-way transparency between central and local actors. Without these structural conditions, participatory forums risk becoming symbolic exercises that legitimize opaque or politically motivated fiscal practices. Therefore, to make a meaningful contribution to fiscal sustainability, reforms must also strengthen independent auditing mechanisms and invest in capacity building for both citizens and civil servants. This ensures that deliberation is informed rather than merely performative. Ultimately, by linking fiscal discipline with social equity, participatory budgeting promotes a more sustainable governance model that balances immediate financial health with long-term economic and social well-being.

This study is not without limitations, which provide useful avenues for future research. First, we measure participatory budgeting with a binary indicator of adoption. Future work could use more granular data, such as the budget size under deliberation or the degree of citizen authority, to identify which specific design features most effectively constrain debt. To complement this, micro-level qualitative studies using case studies and interviews are essential for understanding how stakeholders’ daily enactment of participatory budgeting generates both intended and unintended outcomes. Second, data constraints limit our analysis to explicit government debt. It would be interesting to investigate whether PB affects implicit debt accumulated through Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs). This would answer the question of whether the reform merely shifts borrowing from transparent to opaque channels. Third, despite the qualitative evidence regarding policy entrepreneurs, as with any observational study using a non-experimental design, we cannot fully rule out the possibility of endogeneity, where cities with better pre-existing fiscal discipline might be more inclined to adopt participatory budgeting.

Finally, future research could explore whether the spending shifts induced by participatory budgeting also generate positive environmental benefits, such as increased investment in public green spaces, pollution control, or sustainable transportation, thereby examining participatory budgeting’s contribution across different pillars of sustainability. Beyond these methodological constraints, we may also consider alternative explanations for the observed relationship between participatory budgeting and debt reduction. The adoption of participatory budgeting does not always signify a substantive transfer of power. As Wampler (2012) [18] warns, governments may adopt participatory budgeting as a “pseudo-PB” to enhance their “good government” credentials without delegating actual authority or altering the status quo. In cases where local governments lack fiscal independence or technical capacity, the transparency generated by participatory budgeting may remain procedural rather than substantive. Nevertheless, despite these caveats, our study provides robust evidence that giving citizens a voice in the budgeting process is a promising pathway toward more accountable and fiscally sustainable local governance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.Z. and H.L.; methodology, H.L.; software, H.L.; validation, B.L. and R.F.; formal analysis, H.L. and B.L.; data curation, H.L. and R.F.; writing—original draft preparation, H.L. and R.F.; writing—review and editing, H.L. and B.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Fund of China [grant number 24BGL227], the Guangdong Philosophy and Social Science Foundation [grant number GD25YGG17], and the Guangzhou Philosophy and Social Science Foundation [grant number 2025GZGJ113].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support this manuscript are available from Rui Fei upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all the funding agencies, the editors, and the anonymous referees for valuable comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ang, A.; Bai, J.; Zhou, H. The Great Wall of Debt: Real Estate, Political Risk, and Chinese Local Government Financing Cost. J. Financ. Data Sci. 2023, 9, 100098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Du, J. Soft Budget Constraints and the Default Risk of Local Government Debt in China: Evidence from Financial Markets. Econ. Res. J. 2016, 51, 96–109. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, J.; Hao, X. Logic and Path: Reflection and Regulation on the Issue of Local Government Debt in China. Financ. Econ. Sci. 2020, 53, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, K.; Liu, W. Thirty Years of the Tax-Sharing Reform: Review and Prospect. Subnatl. Fisc. Res. 2024, 32, 4–25. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, N.; Zeng, Y.; Liu, J. The Growth of Local Government Debt: Effects and Transmission. Financ. Econ. Sci. 2022, 123–137. [Google Scholar]

- Fung, A.; Wright, E.O. Deepening Democracy: Innovations in Empowered Participatory Governance. Politics Soc. 2001, 29, 5–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabatchi, T.; Amsler, L.B. Direct Public Engagement in Local Government. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2014, 44, 63S–88S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabatchi, T. Deliberative Civic Engagement in Public Administration and Policy. J. Delib. Democr. 2014, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.K. Public Values and Public Participation: A Case of Collaborative Governance of a Planning Process. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2021, 51, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Butler, J.S.; Petrovsky, N. Understanding Public Participation as a Mechanism Affecting Government Fiscal Outcomes: Theory and Evidence from Participatory Budgeting. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2023, 33, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.H.; Busse, S. Participatory Budgeting in Germany—A Review of Empirical Findings. Int. J. Public Adm. 2019, 42, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touchton, M.; Wampler, B. Improving Social Well-Being Through New Democratic Institutions. Comp. Political Stud. 2013, 47, 1442–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Min, S. Participatory Budgeting and the Pattern of Local Government Spending: Evidence from South Korea. Eur. J. Polit. Econ. 2023, 76, 102235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shybalkina, I.; Bifulco, R. Does Participatory Budgeting Change the Share of Public Funding to Low Income Neighborhoods? Public Budg. Financ. 2019, 39, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Brazil—Toward a More Inclusive and Effective Participatory Budget in Porto Alegre; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, S.-M.; Kim, B.H. Is Participatory Budgeting a Driving Force behind Excessive Social Welfare Spending? Public Manag. Rev. 2024, 27, 2882–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini, F. Toward a New Public Administration: The Minnowbrook Perspective; Chandler: Scranton, PA, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Wampler, B. Participatory Budgeting: Core Principles and Key Impacts. J. Delib. Democr. 2012, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederickson, H.G. Public Administration and Social Equity. Public Adm. Rev. 1990, 50, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, W. The Rationalization of Public Budgeting in China: A Reflection on Participatory Budgeting in Wuxi. Public Financ. Manag. 2011, 11, 262–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, Y. Participatory Budgeting in Local Governance: A Case Study of the Xinhe Town Reform in Wenling, Zhejiang. J. Public Adm. 2007, 76, 125–126. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, G. Improving Participatory Budgeting from the Perspective of the Rule of Law: A Case Study of Participatory Budgeting in Xinhe Town. Econ. Law Rev. 2015, 15, 268–278. [Google Scholar]

- He, B. Deliberative Participatory Budgeting: A Case Study of Zeguo Town in China. Public Adm. Dev. 2019, 39, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X. The Models of Participatory Budgeting: The Case of Yanjin, Yunnan. Public Adm. Rev. 2014, 7, 47–65, 190. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, F.; Liang, W. Review and Supervision of Government Debt: Centering on the Role of the People’s Congress. Study Forum 2025, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Liang, W. Performance Governance of Government Debt: Concepts, Motivations, and Practical Exploration. Theor. Inq. 2025, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhou, L.-A. Political Turnover and Economic Performance: The Incentive Role of Personnel Control in China. J. Public Econ. 2005, 89, 1743–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhou, L.-A.; Zhu, G. Strategic Interaction in Political Competition: Evidence from Spatial Effects across Chinese Cities. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2016, 57, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhart, C.M.; Rogoff, K.S. Growth in a Time of Debt. Am. Econ. Rev. 2010, 100, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Lu, Y. A Study on the Current Situation, Causes, and Prevention Strategies of Local Government Debt Risk. Fisc. Res. 2013, 58–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sihotang, A.D. Does Participatory Budgeting Improve Public Service Performance? Evidence from New York City. Public Manag. Rev. 2024, 26, 3176–3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buele, I.; Vidueira, P.; Luis Yague, J.; Cuesta, F. The Participatory Budgeting and Its Contribution to Local Management and Governance: Review of Experience of Rural Communities from the Ecuadorian Amazon Rainforest. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.; Jeong, S.; Shin, H. A Strategy for a Sustainable Local Government: Are Participatory Governments More Efficient, Effective, and Equitable in the Budget Process? Sustainability 2019, 11, 5312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebdon, C. Beyond the Public Hearing: Citizen Participation in the Local Government Budget Process. J. Public Budg. Account. Financ. Manag. 2002, 14, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sintomer, Y.; Herzberg, C.; Röcke, A. Participatory Budgeting in Europe: Potentials and Challenges. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2008, 32, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabannes, Y. Participatory Budgeting: A Significant Contribution to Participatory Democracy. Environ. Urban. 2004, 16, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartocci, L.; Grossi, G.; Mauro, S.G.; Ebdon, C. The Journey of Participatory Budgeting: A Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Directions. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2023, 89, 757–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Lin, H. How to Conduct Participatory Budget Oversight: The Practice and Exploration of the People’s Congress in Tianhe District, Guangzhou. People’s Congr. Stud. 2021, 41–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q. How Do Grassroots Policy Entrepreneurs Achieve Policy Innovation and Institutionalization? An Analysis of the Reform Practice of Participatory Budgeting in Wenling. Public Adm. Rev. 2020, 13, 152–171+199. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- He, J. Development of Democratic Tools and Enhancement of Governance Capacity: A New Perspective on Wenling’s “Democratic Consultation Meetings”. J. Public Manag. 2007, 4, 179–180. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat. The State of the World’s Cities 2004/2005—Globalization and Urban Culture; UN-Habitat: Sterling, VA, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-7-112-17306-8. [Google Scholar]

- Boulding, C.; Wampler, B. Voice, Votes, and Resources: Evaluating the Effect of Participatory Democracy on Well-Being. World Dev. 2010, 38, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, S. The Effects of Participatory Budgeting on Municipal Expenditures and Infant Mortality in Brazil. World Dev. 2014, 53, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S. Citizen Participation in Budgeting: A Trade-Off between Knowledge and Inclusiveness? Public Adm. Rev. 2015, 75, 572–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W. The Behavioral Logic of Implicit Local Government Debt Expansion in China: Path Transformation and Policy Recommendations for Regulating Local Government Borrowing. Fisc. Res. 2019, 60–71+128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, L.H. Fiscal Federalism and Soft Budget Constraints: The Case of China. Int. Political Sci. Rev. 2012, 33, 455–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodden, J. The Dilemma of Fiscal Federalism: Grants and Fiscal Performance around the World. Am. J. Political Sci. 2002, 46, 670–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.; Xu, Z.; Yu, J.; Zhu, J. Understanding Local Government Debt in China: A Regional Competition Perspective. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2023, 98, 103859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Tian, Y.; Lei, A.; Boadu, F.; Ren, Z. The Effect of Local Government Debt on Regional Economic Growth in China: A Nonlinear Relationship Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebdon, C.; Aimee, L. Franklin Citizen Participation in Budgeting Theory. Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 66, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shangguan, J. Participatory Budgeting as a Practical Form of Whole-Process People’s Democracy. J. Explor. Free. Views 2020, 27–29. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. The Theory and Practice of Participatory Budgeting. Comp. Econ. Soc. Syst. 2007, 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, L.; Zhang, X. Legalization of Government Budget, Fiscal Transparency, and Local Fiscal Efficiency: Evidences Based on the Implementation of the New Budget Law. Contemp. Financ. Econ. 2023, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Hou, Y. Budgeting for Accountability: A Comparative Study of Budget Reforms in the United States during the Progressive Era and in Contemporary China. Public Adm. Rev. 2009, 69, S53–S59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltzman, S. Voters as Fiscal Conservatives. Q. J. Econ. 1992, 107, 327–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, T.; Williams, D.; Gupta, A. Does Participatory Budgeting Alter Public Spending? Evidence From New York City. Adm. Soc. 2020, 52, 1382–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Fiscal Transparency Code. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/fiscal-policies/fiscal-transparency (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Swaner, R. Trust Matters: Enhancing Government Legitimacy through Participatory Budgeting. New Political Sci. 2017, 39, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Renzio, P.; Wehner, J. The Impacts of Fiscal Openness. World Bank Res. Obs. 2017, 32, 185–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volodin, D. Deliberative Democracy and Trust in Political Institutions at the Local Level: Evidence from Participatory Budgeting Experiment in Ukraine. Contemp. Politics 2019, 25, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrov, E.; Bourmistrov, A.; Grossi, G. Participatory Budgeting as a Form of Dialogic Accounting in Russia: Actors’ Institutional Work and Reflexivity Trap. Account. Audit. Account. 2018, 31, 1098–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manes-Rossi, F.; Brusca, I.; Orelli, R.L.; Lorson, P.C.; Haustein, E. Features and Drivers of Citizen Participation: Insights from Participatory Budgeting in Three European Cities. Public Manag. Rev. 2023, 25, 201–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassoli, M. Participatory Budgeting in Italy: An Analysis of (Almost Democratic) Participatory Governance Arrangements. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2012, 36, 1183–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feld, L.P.; Kirchgässner, G. The Political Economy of Direct Legislation: Direct Democracy and Local Decision-Making. Econ. Policy 2001, 16, 329–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milesi-Ferretti, G.M. Good, bad or ugly? On the effects of fiscal rules with creative accounting. J. Public Econo. 2004, 88, 377–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, J.E.; Lassen, D.D. Transparency, Political Polarization, and Political Budget Cycles in OECD Countries. Am. J. Political Sci. 2006, 50, 530–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollwitzer, S. Budget Institutions and Fiscal Performance in Africa. J. Afr. Econ. 2011, 20, 111–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, P.; Liu, B.; Wang, G. Has the Improvement of Fiscal Transparency Reduced the Scale of Government Debt? Evidence from 29 Provinces in China. J. Cent. Univ. Financ. Econ. 2015, 18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hagelskamp, C.; Silliman, R.; Godfrey, E.B.; Schleifer, D. Shifting Priorities: Participatory Budgeting in New York City Is Associated with Increased Investments in Schools, Street and Traffic Improvements, and Public Housing. New Political Sci. 2020, 42, 171–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falanga, R.; Verheij, J.; Bina, O. Green(Er) Cities and Their Citizens: Insights from the Participatory Budget of Lisbon. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Cho, B.S. Citizen Participation and the Redistribution of Public Goods. Public Adm. 2018, 96, 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shobande, O.A.; Ogbeifun, L. Debt by Rules: Recrafting Impact of Infrastructure Investments and Business Cycles on Debt Sustainability. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2025, 73, 282–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Zhao, J.Z. The Rise of Public-Private Partnerships in China: An Effective Financing Approach for Infrastructure Investment? Public Adm. Rev. 2019, 79, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Chen, Y.; Li, R. Welfare Rigidity, the Composition of Public Expenditure and the Welfare Trap. Soc. Sci. China 2019, 40, 110–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarska-Olejniczak, D.; Olejniczak, J.; Svobodova, L. How a Participatory Budget Can Support Sustainable Rural Development-Lessons from Poland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Local debt expansion and corporate tax avoidance: An empirical study based on the prefecture-level. Res. Financ. Econ. Issues 2021, 92–100. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, S.; Wang, X. Soft budget constraints on local government debt under the new Budget Law: Calculation based on the transaction data of “self-insurance and self-repayment” debt. J. Econ. Rev. 2021, 136–151. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Pan, Y. Can the issuance of local government bonds promote the high-quality development of real enterprises?—An empirical study based on the data of China’s A-share and NEEQ manufacturing listed companies. J. Tech. Econ. 2023, 42, 70–81. [Google Scholar]

- Diao, W. Assessment of China’s Local Government Debt Transparency: 2014-2015. J. Shanghai Univ. Financ. Econ. 2017, 19, 80–90. [Google Scholar]

- Tsinghua University Chinese Municipal Government Fiscal Transparency Research Report (2013–2022); Tsinghua University: Beijing, China. Available online: https://www.sppm.tsinghua.edu.cn/xycbw/yjbg.htm (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Wen, Z.; Ye, B. Analyses of Mediating Effects: The Development of Methods and Models. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 22, 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krull, J.L.; MacKinnon, D.P. Multilevel Modeling of Individual and Group Level Mediated Effects. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2001, 36, 249–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.