Abstract

Riverbank erosion is a significant natural disaster that is prevalent in the deltaic regions in Bangladesh, resulting in loss of land, crops, and settlements. This research work is concentrated on the Satkhira Koyra area and is oriented towards a comparative assessment of the functionality of geo-bag and cement concrete (CC) blocks for erosion control purposes. The results showed that a geogrid could be used on the riverbank slope for more soil stability. The proposed approach is that the geogrid is used as a base layer for the slope. The sand-filled geo-bags are more cost-effective with this combination. Field monitoring and hydraulic model testing were used to identify their performance under natural flow conditions. Lined with geotextile fabric and filled with sand, the geo-bags were located in the most susceptible riverbank areas. The empirical results showed that the geo-bags provide the same levels of hydraulic resistance as those provided by CC blocks, but with substantial economic benefits and installation accomplished by local labor. When used in combination with a geogrid base layer, the geo-bag construction ensured excellent slope stability and allowed the establishment of natural vegetation, thus contributing to an environmentally friendly restoration. While CC blocks remain the optimal solution for high-value structures, the combined geogrid and geo-bag system offers a more flexible, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly alternative for stable erosion protection.

1. Introduction

Riverbank erosion may disorganize ecosystems, resulting in the resettlement of lowlands to the uplands due to rising floods. One of the greatest environmental problems, especially in Bangladesh, is the erosion of rivers, since the country is situated within a deltaic system of global significance. Geotextiles are widely used under seawalls, dikes, and riverbank protection structures as both a filter and separator in coastal defense works.

The consequence of riverbank erosion is the mass destruction of land, crops, and habitat and displacement. Riverbank erosion must receive integrated solutions such as riverbank protection, sustainable land-use planning, and community awareness interventions to limit the disastrous impacts of riverbank erosion and conserve the lives of millions of individuals [1]. The purpose of this paper is to conduct research into issues of the failure of embankments and erosion of riverbanks in Bangladesh by researching the problems associated with stability and geotechnical properties. Also, in addition to the construction of major infrastructure and buildings, other factors have led to the instability of the riverbanks in the region. Such factors include massive deforestation, alterations in land-use patterns, inconsistency in rainfall caused by climatic changes, and escalating extreme flooding in the region. This research is aimed at making the area more aware and gaining control over problems of erosion in the region. The most popular methods used for the management of rivers are channelization, trapping of sediment, and bank stabilization [2]. The literature available is very limited and thus hinders the development of comprehensive insights into the behavior of the geo-synthetically reinforced foundations [3].

The scope of this research is to understand the impact of the geogrid [4]. The cost of protecting the riverbank along the Jamuna River is astronomical [5]. The Bangladesh Water Development Board (BWDB) is working with limited resources in an attempt to stem the suffering of the people and keep national losses to a minimum. The progressive erosion of both natural and engineered slopes as a result of erosion processes has become a hindrance in the development of urban and rural infrastructure. Geotextiles and geogrids have been widely used in a variety of geotechnical applications, from pavement systems to foundation improvements, slope stabilization schemes, retaining structure designs, and a myriad of other infrastructure applications [6]. Failure to control erosion results in soil loss, thus reducing the bearing capacity of the soil foundations and at the same time increasing the likelihood of sediment [7,8,9]. Riverbank erosion, in academic terms, refers to the progressive loss of the land substratum on the banks of the fluvial space. The most important forces that cause this geomorphic process are the forces inherent to the hydrologic cycle [10]. When riverbank erosion commences in the monsoon season, the deployment of geo-bags in a segment of the Dharla river has proved to be both cost-efficient and expedient, surpassing the conventional approach of concrete benching [11]. The construction industry is experiencing a paradigm shift and increasing demand [12]. Geotextiles as protective membranes are very important for the protection of riverbanks against erosion caused by hydrodynamic current in aqueous systems. The present work was undertaken to develop geotextiles that combine synthetic and natural fibers, thus offering much better property performance [13,14,15]. In the event of setting the cover surface at a steep inclination, it is imperative to include a supplementary reinforcing geogrid, which is normally attached on top of the slope or on intermediary benches, to achieve the necessary factor of safety against sliding.

The combination of a geogrid layer between the granular fill and the soft soil is a proven method, one whose impact on shallow foundation performance and bearing capacity has been extensively researched. Therefore, the use of geogrids and geo-bags has been more effective in controlling riverbank erosion and soil stability [4,10].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

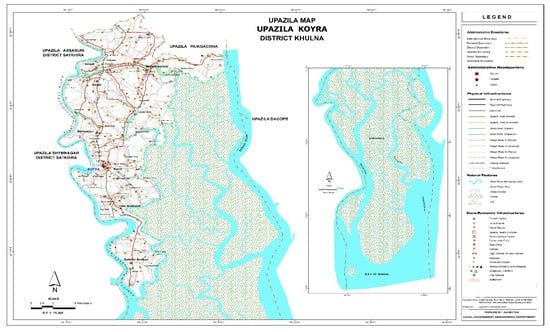

The Rai, Rupsha, and Bhairab Rivers all flow through Satkhira Koyra, a small area in the Khulna district. The Rai River is an important river system in the Satkhira Region. The chosen transect covers the 17.150 km to 18.050 km section along the bank that comes within the jurisdiction of the Bangladesh Water Development Board (BWDB) and, more precisely, the Satkhira Polder Division-2 board. Figure 1 shows the local government engineering department of Bangladesh, compiled from a GPS survey in 1999 and the LGED road database in 2021. The Satkhira Koyra region faces unique riverbank stability challenges. As one of the inland rivers with seasonal flash floods, the Rai river experiences strong tidal currents and storm surges from the Bay of Bengal. The riverbanks are composed of soft, weak alluvial soil, which is highly prone to failure under hydraulic loads. This specific combination of dynamic water forces and poor soil strength demands a flexible and adaptive erosion control system, which is the focus of this study on geogrid-reinforced geo-bags. Riverbank erosion, scouring, and instability of riverbank protection have been observed to be imminent, and this is mainly due to the strong tidal flows and frequent cyclonic disturbances. The gradual erosion of the leftover embankment is a menace to the existence of surrounding settlements, agricultural lands, and fisheries.

Figure 1.

Koyra Upazila (Source; LGED Base Map 1994–95 Landsat TM 1998).

2.2. Preparing Geo-Bags and CC Blocks

Geotextiles are a better option than other natural textiles in applications of erosion control and slope protection [16,17]. The filling geotextile bags (Western Superior Jute Industries Limited Company, Dhaka, Bangladesh)with sand for erosion control is shown in Figure 2. Empty geotextile bags with different sizes and capacities at the project site are made from standard geotextile fabric (97% polypropylene fabric with 3% additives, mass >= 400 gm/m2, unit weight: 855 kg/m3, EOS = 0.075 mm, test of service life according to ISO 13438:2018 [18]). The geo-bag inner height and diameter are 1075 mm × 850 mm. The geotextile thickness, fill volume, and weight are 3.0 mm, 0.1164 cm3, and 175 kg, respectively.

Figure 2.

Preparing sand-filled geo-bags for use in erosion control.

The work involves manufacturing and supplying CC blocks (S.S Engineering & Construction Company, Dhaka, Bangladesh) using a lean 1:2:4 mix of cement, specified sand, and stone chips to achieve a 28-day strength of 15 N/mm2. This includes all operations from material preparation and curing for 21 days to ancillary tasks such as shuttering and stacking, all as directed by the engineers. Figure 3 presents the assembly of concrete block revetments for bank stabilization.

Figure 3.

Preparing CC blocks for riverbank protection.

2.3. Dumping Range and Total Station

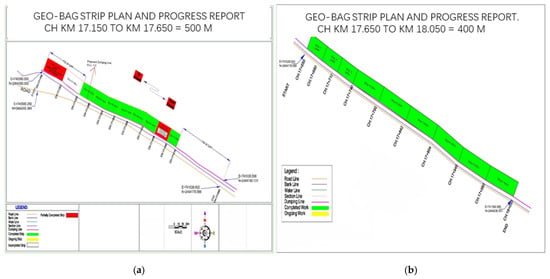

The construction of revetment requires huge funds, so the government of Bangladesh started their construction on an isolated basis, allocating funds on the basis of priority. The proposed dumping line reduces the level (RL −1.5) and the position 740,580.000 E, 2,464,393.000 N. The total geo-bag strip plan and progress change at Koyra Horipur in km is 17 + 150 to 18 + 50 = 900 m. Figure 4a is CH: 17.150 to 17.252 with a dumping length gap of 102 m, and Figure 4b is a completed work from CH: 17 + 650 to 18 + 050 with a dumping length of 400 m.

Figure 4.

Geo-bag strip plan and progress report (a,b).

Observations from working sites were examined to document the stage of the processing, preparation, transportation, placing, and dumping of geo-bags and concrete blocks used in bank protection works. The BWDB database was used to compare the cost of the two materials in terms of volume and surface area covered. Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 show the physical properties and cost comparisons of CC blocks and geo-bags, respectively.

Table 1.

Physical properties of CC blocks [16].

Table 2.

Preparing CC blocks—total cost [16]. Unit: BDT/kg.

Table 3.

Physical properties of geo-bags [16].

Table 4.

Total cost for geo-bags [16]. Unit: BDT/kg.

2.4. Geo-Bag and Cement Concrete Block Cost Comparison

The economic analysis of the CC blocks and the geo-bags showed a high difference in their cost-efficiency, which shows the importance of the selection of materials in the construction project. The physical characteristics and cost constituents of CC blocks and geo-bags, respectively, are based on standard data provided by the BWDB.

Geotextile bags and sand-filled mattresses are made from either woven, non-woven, or hybrid geotextile fabrics. The most commonly available type of geotextile bag is usually made of polyamide (Nylon), polyester (PET), or polypropylene (PP). Geo-bags showed significantly reduced overall prices ranging between BDT 238 and 393 per bag according to weight and volume. The manufacturing cost (BDT 173.9–279.1), filling cost (BDT 47–87), and dumping costs (BDT 17–27) are also much less compared to the conventional CC blocks and in this regard, the economic efficiency and operational convenience of geo-bag systems is highlighted.

Revetment for bank protection is built in order to minimize or stop the erosive processes on the bank line. It shields the riverbank from the large numbers of waves and currents, thus protecting the existing riverbank and embankment [5]. Similarly to the developments that have been seen in the setting out of guide bundles and upstream supporting works, developments have been taking place in the field of underwater protection. It is found that the unit cost of CC blocks grows proportionally to the block dimensions, which is due to an increase in the material consumption and handling weight. In particular, the production price of CC blocks in the range of (30 × 30 × 3 cm3) is between BDT 257.8 and BDT 1137.86, whereas the total price (average dumping included) in the range of (50 × 50 × 5 cm3) is between BDT 284 and BDT 1256 per cm3. Such high prices can be explained principally by the cement-intensive (1:3:6) concrete mix and time-consuming process of placement.

Geo-bags have a less dense structural composition; it gives them a sufficient coverage area of (1.2 × 0.95 m2) and a consistency in thickness of approximate 3 mm, which makes them an efficient solution to flexible slope protection.

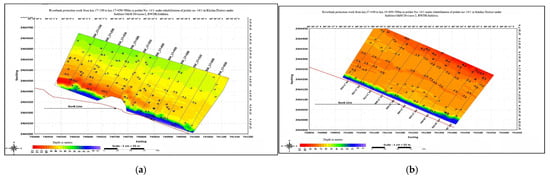

2.5. Two Different Contour Map Sections Showing Bank Protection

Figure 5 shows two different contour maps from sections of bank protection (17 + 150 to 17 + 650 km and 17 + 650 to 18 + 50 km) in Polder No.14/1, Satkhira District, Rai River. The hydrography is displayed as a color gradient: shallow water surfaces (0 m to −3 m; shown in blue-green) contrasting with deeper bedforms down to −13 m (shown in orange and red). The maps show steep bank line gradients with local depressions down −10 m to −11 m, thus identifying zones susceptible to toe scour and hydraulic instability.

Figure 5.

Riverbank protection works contour heat map. (a) 17 + 150 to 17 + 650 km; (b) 17 + 650 to 18 + 50 km.

The numerous contour lines on both bank sections highlight the occurrence of active erosional processes. Such bathymetric profiles are invaluable for defining the exact position of the geo-bags and CC blocks, allowing the dumping lines and revetments to be optimally aligned. Thus, the spatial and hydraulic information available from these maps enables the implementation of riverbank protection structures in eroding reaches of the Satkhira Koyra Rai river.

2.6. Bank Erosion Mechanisms and Material Suitability

The erosion of riverbanks results from hydraulic as well as geotechnical instabilities. Hydraulic instability manifests through toe scour and flood rise and drawdown. The combined weight of accumulated driftwood and plants, removal of riverside trees and grasses, the dislodging of soil by wave action, and scouring effect of swirling water within the river itself all contribute to the problem [19]. The riparian vegetation, along with the other meadows, has a number of important ecological functions. The rate of bank erosion in the antiquated floodplain is, on average, less than the rates observed in the more recent floodplain; the variation in these rates is high. In particular, along the old floodplain, between Paturia through Dhulsunra to Mawa, the erosion rates go from zero to twenty meters per annum based on the intensity of the main flow of the Padma exerting force upon the bank.

It serves as a multifunctional environmental buffer: filtering pollutants from runoff, dampening flood discharges, recharging groundwater, reducing soil erosion, stabilizing coastal ecosystems, and ultimately creating more favorable conditions for both livestock and human populations [20].

Figure 6 shows the riverbank before and after repair at the Satkhira Koyra Rai river. The pattern of the bearing capacity increment could be explained by the geogrid. The soil matrix is confined to a lateral direction and its load-bearing stratum is strengthened, which consequently gave it a higher resistance to shear deformation [15]. The following discussion on geogrid reinforcement, based on the literature [4,15,20], presents a proposed enhancement for future applications to further improve slope stability and system longevity. Depending on the nature of soil, non-woven and woven geotextiles are used to curb soil erosion. Woven geotextiles are also used in situations where the size of sediment particles would be relatively large because of their large pore size. On the other hand, much finer particles such as clay or silt are also used with woven geotextiles, especially where there is a water uplift [21]. The structure of the geotextile provides both high tensile strength and the ability to be easily installed and removed; both features provide significant benefits for construction and land reclamation projects [22].

Figure 6.

Slope profiles of pre- and post-construction.

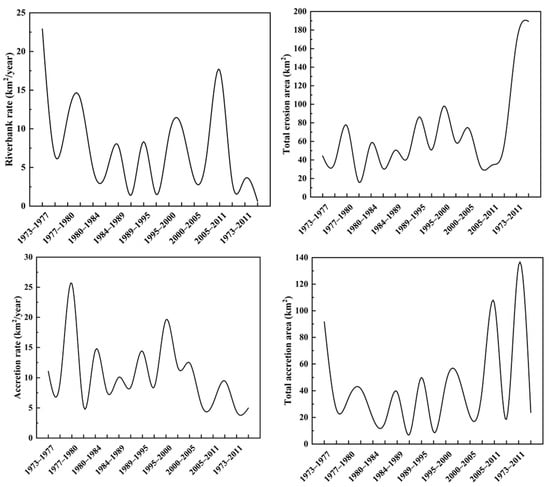

3. Erosion and Accretion of the Padma River (1973–2011)

Figure 7 shows the erosion and accretion area along the Padma River during 1973 to 2011. The most intensive erosion was recorded on the right bank in the period 1973–1977 and covered an area of about 22.91 km2.

Figure 7.

Erosion and accretion RB and LB graph by year [23].

The lowest amount of erosion occurred between 1977 and 1980, when about 3.6 km2 was lost. Accretion showed an inverse trend, reaching maximum values of 11.58 and 14.56 km2 in the 1977 to 1984 time period, respectively. These observations lead to the idea that rates of erosion were high during the initial years of observation and then subsided, before resuming in the 1980 to 1984 period.

Activity was observed between 1984 and 1989, where erosional and accretional areas were observed, with areas of 10.13 km2 and 10.91 km2, respectively. Losses were from 5.58 km2 to 17.62 km2, and accretion increased until a maximum of 22.86 km2 on the lower bank at the end of study (2005 to 2011). These analyses have shown that in winding stretches of the Dharla River, by keeping the depth of water at no more than 10 m, it is possible to protect channel banks at a low cost by using geo-bags, and land can be reclaimed cheaply [11].

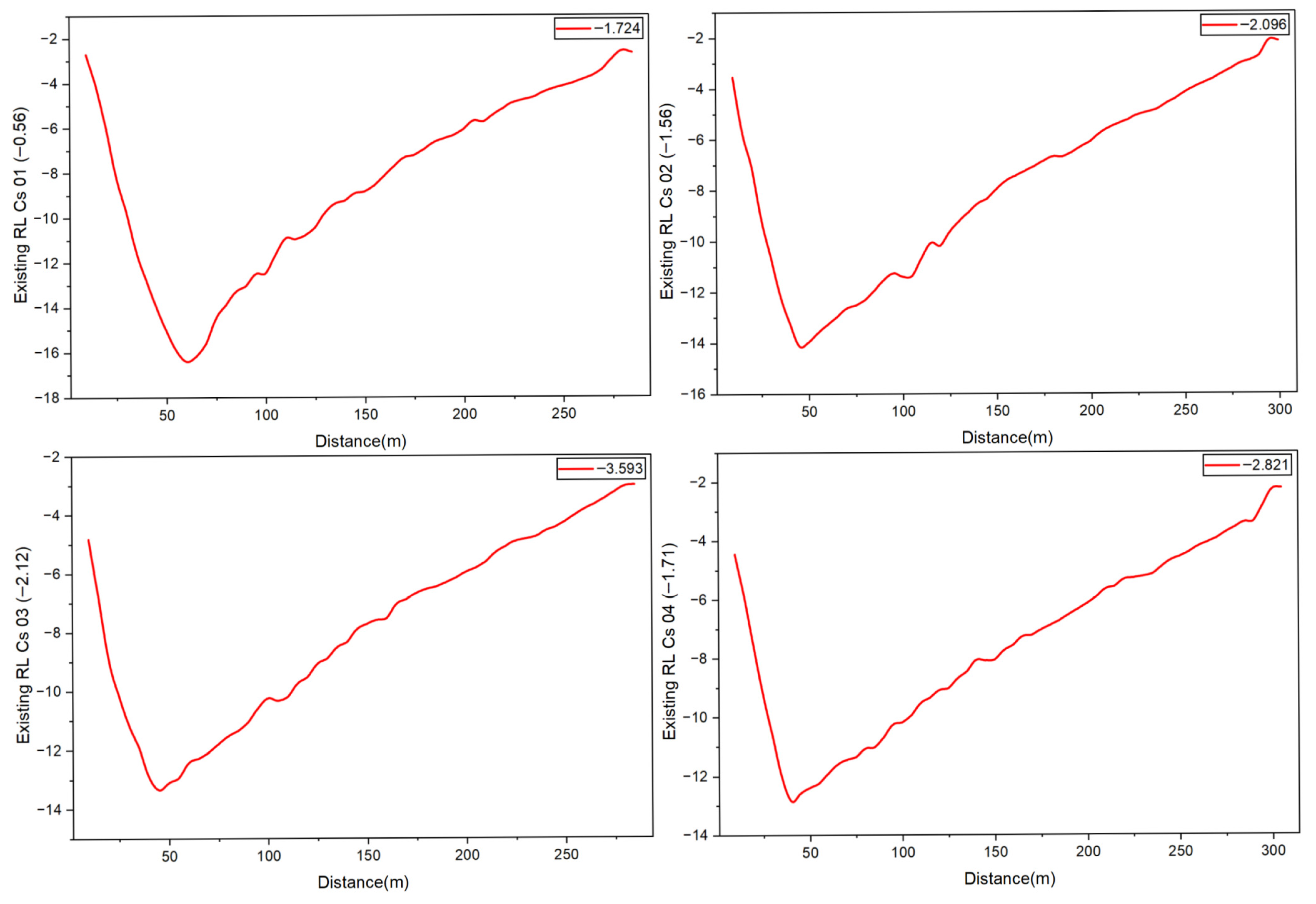

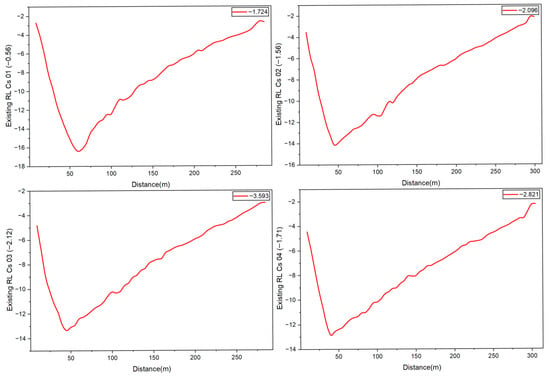

3.1. Analysis of the Reduced Water Level (RL)

Figure 8 shows four different cross-sectional existing reduced levels (CS 01–CS 04). The reduced level values represent the relative elevation reductions as compared to standard reference levels and thus represent the elevation of the bed with respect to the level of the water for each of the survey datasets. The cross-section data were collected to analyze the morphological and hydraulic characteristics of the Rai river in support of polder rehabilitation and riverbank design. These measurements provide essential information on bed-level conditions, sedimentation patterns, and erosion tendencies, which are critical for designing sustainable flood control and water management structures in coastal regions. The survey findings thus form an important baseline for assessing future river behavior and for guiding engineering interventions.

Figure 8.

Existing reduced water levels by distance.

3.2. General Morphology Water RL

General surveys are focused on water levels and bathymetry with data for flow and sediment discharge not collected systematically. Some of the manufactured structures have been regularly monitored (bathymetric surveys). River morphology comprises the variations in cross-section morphology of a river system, as well as in its flow direction and pattern caused by the processes of sediment deposition and transportation. These processes lead to the formation of different morphological stems, which are often connected with each other. The information on riverbank protection and river training works is adequate enough to give a good indication of scour depth and bed slopes, but not enough to develop systematic risk-based designs. Sometimes, the sections of structure underwater, which are a large part of it, have been investigated systematically using scuba diving and have led to significant understanding of the structure of certain projects. These four cross-sections have a pronounced V-shaped profile bed that is typical of scoured alluvial channels in high-flow regimes. The lowest recorded river levels, between about −13 m and −17 m, occur at the deepest point of the river channel. The cross-sectional widths range from 250 m to 300 m, suggesting a wide and hydraulically active main channel.

4. Design of Revetments with Geotextile Containment System

4.1. Hydraulic Conditions

An engineer needs information on the level of water, wave nature, approach direction, and current flows when designing revetments. The design water levels should consider tidal variations and storm surges and are known as the still water level (SWL). The SWL is the surface of water without the influence of waves. Two parameters are the significant wave height, which is the average height of the third-highest wave sand breaker parameter [24].

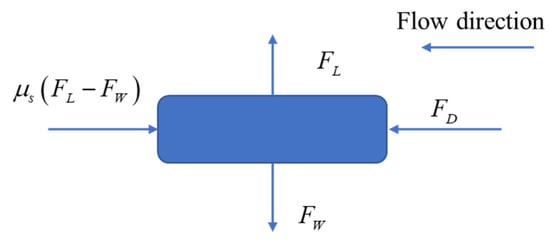

The water-flow loading equation is as follows:

FD = Drag force (N);

= Current velocity (m/s);

CD = Drag coefficient;

A = Projected area perpendicular to flow (m2);

= Water density (kg/m3).

One loading parameter will feature in the stability equations for flow and attack. The critical velocity is defined as the current velocity at which channel erosion or hydraulic instability initiates and is usually expressed as a depth-averaged velocity.

4.2. Physical Hydraulic Model Test

A hydraulic model prototype to model 1:20 testing in the NHC laboratory, Vancouver, Canada, was used to study the hydrodynamic performance of geo-bags. The listed bag loads are values of dry, sand-filled, scaled prototype loads, whereas the velocities are scale depth-averaged flow velocities.

The use of geo-bags strengthens the soil, resulting in strong foundation settling [25]:

- v = local vertically-averaged velocity;

- = safety factor, minimum recommended value for riprap design = 1.1;

- = 0.30 for angular rock and 0.36 for rounded;

- = coefficient for vertical velocity distribution, range of 1.0 to 1.28 for straight channels to abrupt bends;

- = coefficient for riprap layer thickness, 1.0 or less with increasing thickness;

- = side slope correction factor;

- = size of stone for which 30% by weight is finer;

- = depth of flow;

- = specific weight of water;

- = specific weight of stone.

The acceleration vector is the rate of change in velocity of the geo-bags’ center of mass:

In sliding failure mode, this is governed by Newton’s Second Law:

where

= net external force acting on the geo-bag;

= mass of the geo-bag.

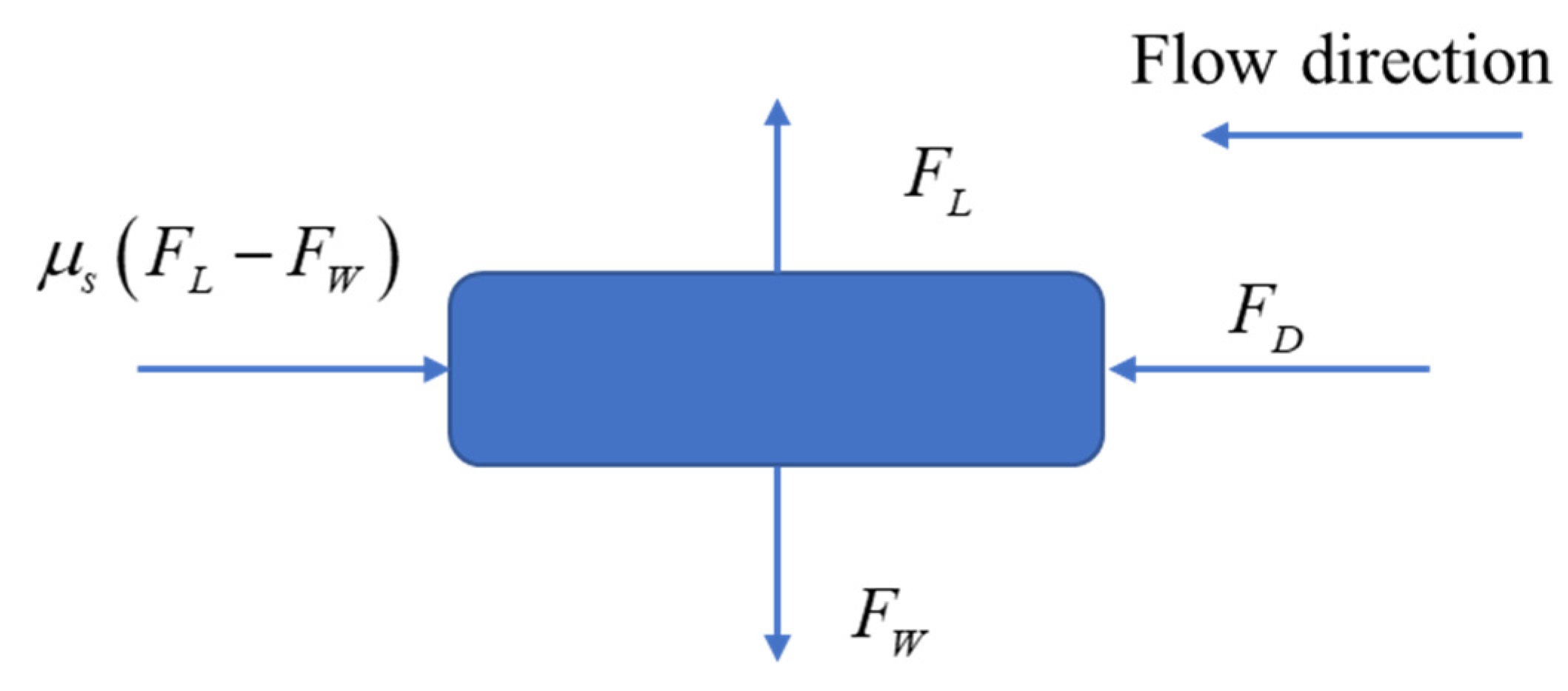

Hydrodynamic forces affect the bag, including drag, lift, and buoyancy, which is analyzed in the research field. The force affecting the submerged bag is shown in Figure 9. is the lift force, is the drag force, and is the weight of the bag. For analysis forces affecting the bag, there were two failure modes identified [25].

Figure 9.

Forces affecting geo-bag at the bottom of the channel.

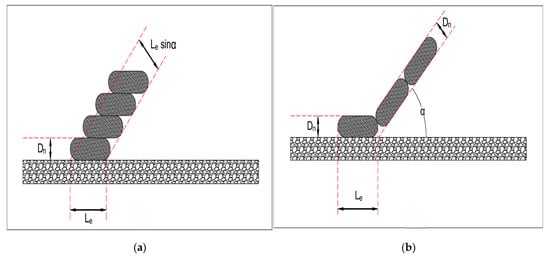

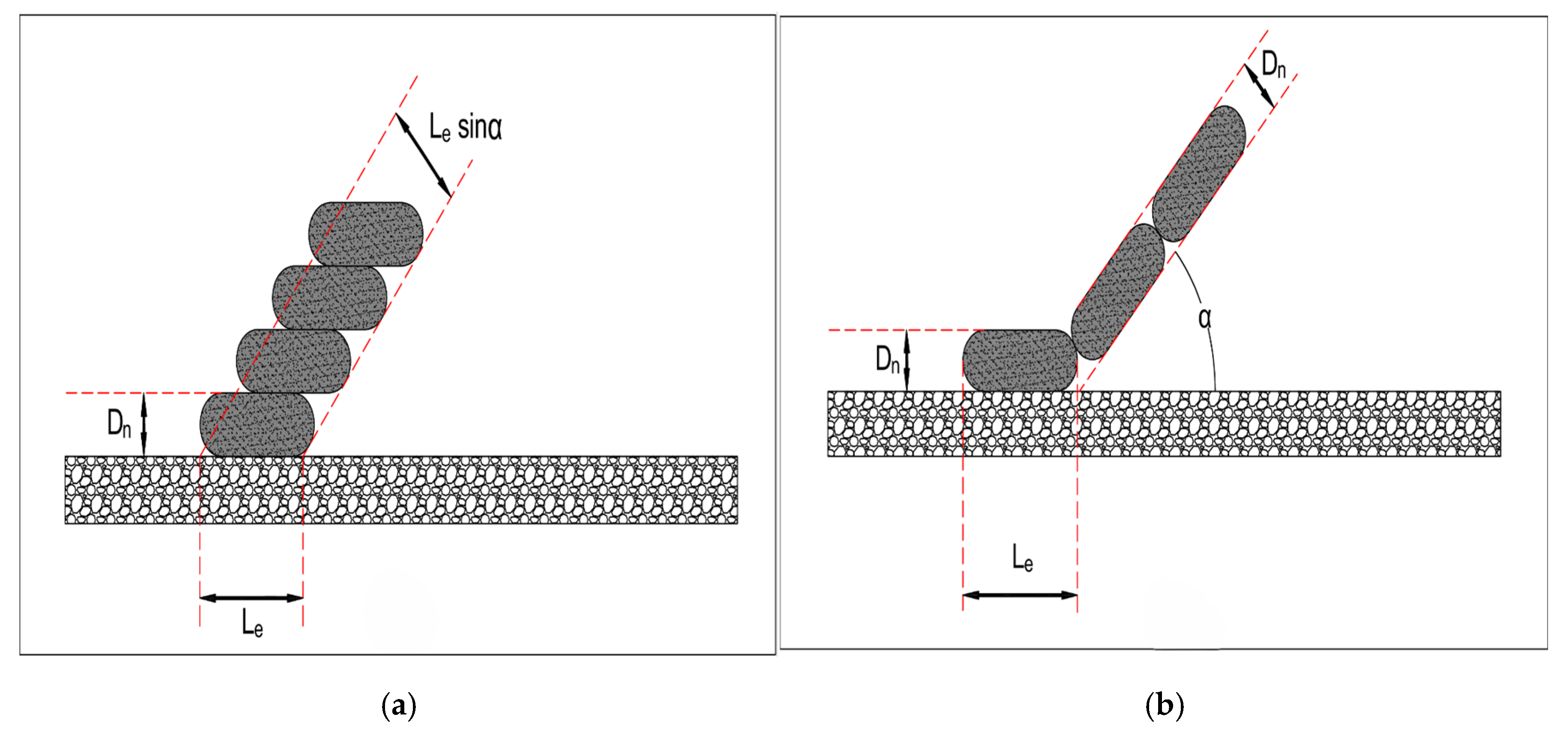

4.3. Geo-Bag Arrangement

The effective thickness of the geo-bag revetment De for placement method 1—wave loading—and placement method 2—under water revetments (see Figure 10a,b)—are given in Equations (8) and (9), respectively [10].

where

= nominal length of geo-bag unit [m];

= slope angle of revetment;

= nominal thickness of geo-bag unit [m].

Figure 10.

Geotextile bag arrangement (a) geometry 1; (b) geometry 2.

Figure 10.

Geotextile bag arrangement (a) geometry 1; (b) geometry 2.

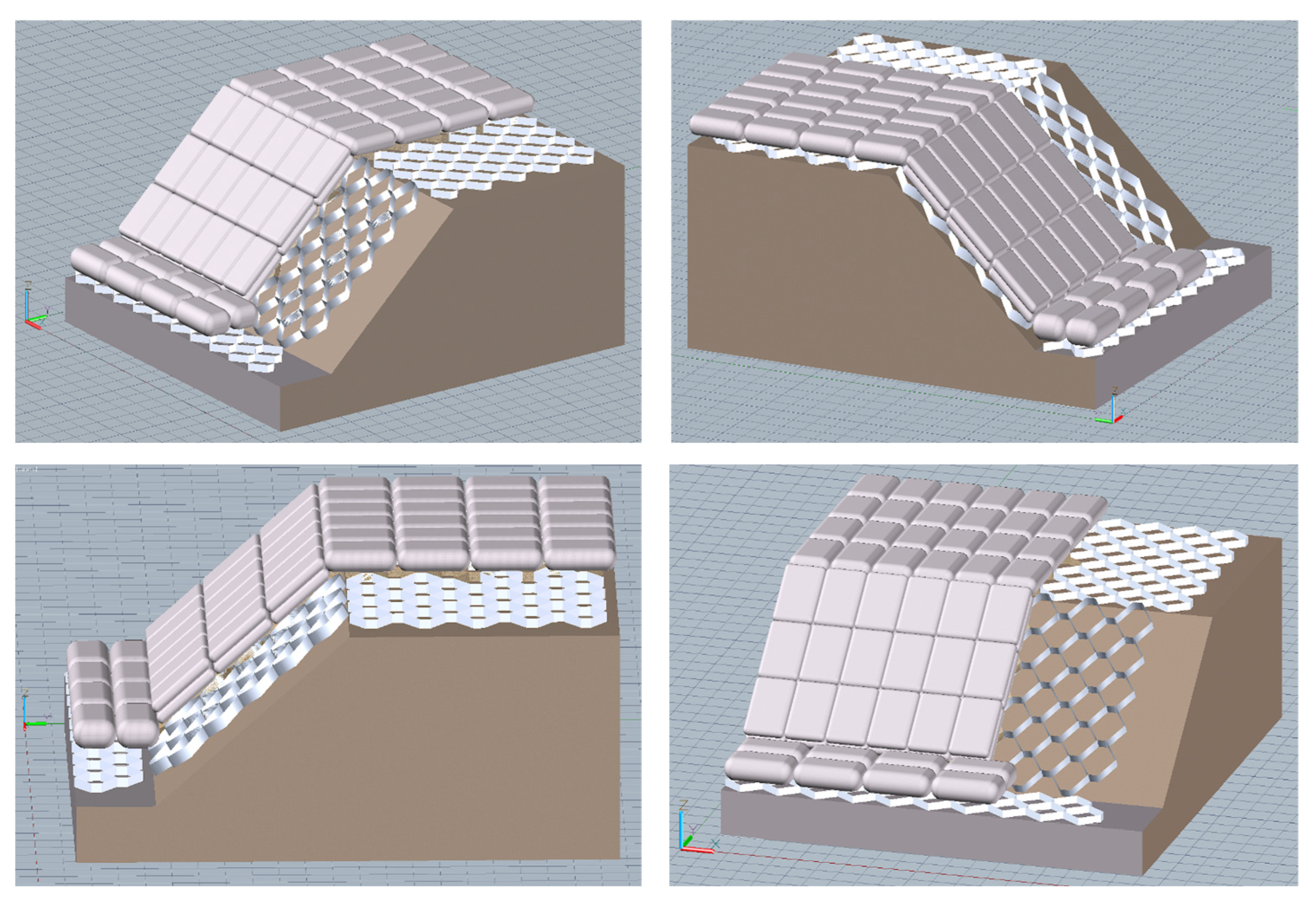

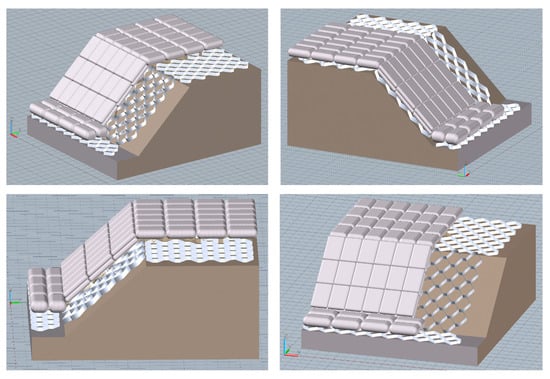

4.4. Geogrid Use as the Base Layer for Slope Protection

These inventions of methods that enable the creation of relatively rigid polymeric materials using tensile drawing have broadened the scope of geogrid usage. The deviations of the soil behavior under the soaked conditions improve with the increasing number of geogrid layers. Geogrids are used in the reinforcement and stabilization of embankments built on soft soils. By stabilizing and confining the subgrade, they reduce the lateral displacement and, on the other hand, increase the shear capacity and the load-carrying performance in areas of low soil. Geogrids are fully compatible with slopes in coastal areas, such as slopes under hydrodynamic loads, as may occur in the coastal environment. They can now be used to strengthen soils in the construction of retaining walls, stabilization of steep slopes and foundations of roadway base and structure back fills and foundations. Geogrid and geo-bags can provide a cost-effective and flexible solution for riverbank erosion control, as shown in Figure 11. For effective riverbank erosion, this solution is used as slope protection with a composite approach, which can be adopted by using geogrids as the base layer and sand-filled geo-bags as the surface protection. One of the developed methodologies that has been used in the ecological preservation of slopes is three-dimensional geogrid ecological slope protection.

Figure 11.

Effective use of geogrid and geo-bag for slope.

This technique is marked by a small economic footprint and a strong performance against erosive forces, e.g., wind, rain, and flood, thus helping to strengthen and stabilize vulnerable slopes. Therefore, this stabilizes the underlying bank material and provides a suitable foundation for the armor system. The filled geo-bags on the bank’s upper surface act as a flexible revetment resisting the hydrodynamic forces of flow. Since slope-protection structures play a vital role in engineering safety and environmental sustainability, they have been subjected to rigorous demand by recent research, with numerous innovative approaches being developed. A comparison of the cost-effectiveness between geogrids with geo-bags and CC blocks for riverbank erosion protection is presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Cost-effectiveness comparison of geogrid + geo-bag vs. CC block for riverbank erosion protection.

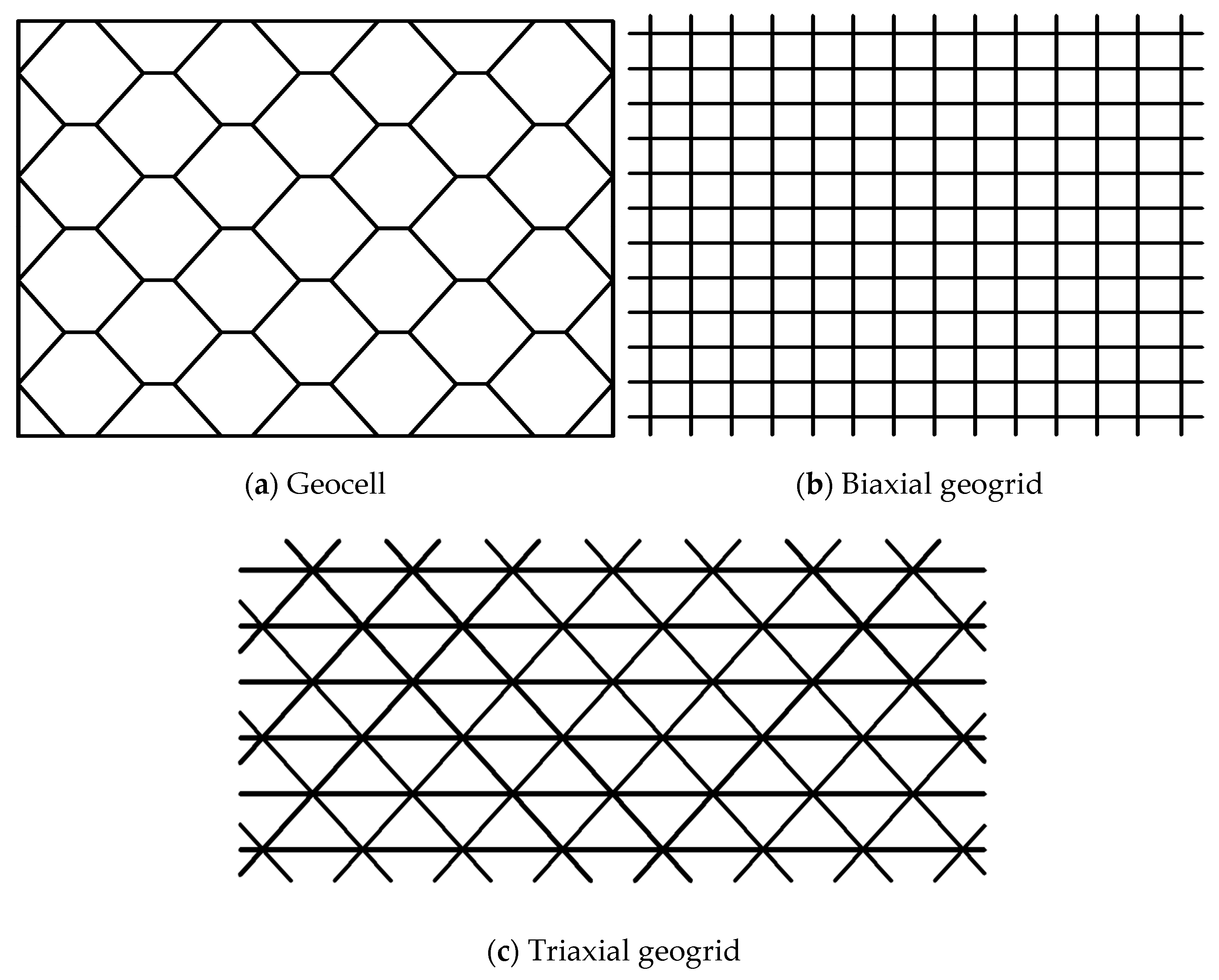

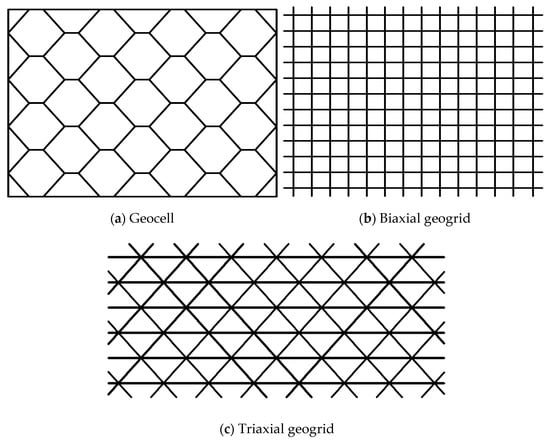

4.5. Typical Geosynthetic Products

A geogrid is a geosynthetic material that consists of contiguous parallel strands of tensile ribs. The effect of reinforcement stiffness, as studied by finite-element analyses, is presented [26]. Geogrids are used for reinforcing different types of soils under various conditions [27]. These ribs have apertures of adequate size to allow the infiltration of surrounding soil, aggregate, or other geotechnical constituents. Application of geogrid reinforcement in the soil matrix is a mature technology applied to increase shear resistance, increase stiffness, and reduce undesirable settlement in a variety of geotechnical applications, including shallow foundations, retaining walls, and earth slope stabilization projects [8]. A combination of geocell reinforcement with a vegetative canopy significantly reduces aeolian and pluvial sediment fluxes, shown in Figure 12, thus protecting the integrity of the subsoil and ensuring the stability of the slope despite the presence of extreme erosional conditions [7]. According to the outcome, the two triaxial geogrids were found to work a little better than two biaxial geogrids in minimizing permanent deformation of the pavement [28].

Figure 12.

Geometry of typical geosynthetics.

The positive findings regarding the triaxial geogrid from the above experiments may have been compromised, as the biaxial and triaxial geogrids were prepared using different polymer materials. Empirical studies have shown that vertical stress near the slope surface is always smaller than internal stress in the slope [29]. This carefully designed experimental setup was developed with the goal of reducing boundary artifacts and ensuring that compaction and loading were homogeneous, which is key to accurately observing pavement behavior. Geotextiles are a revolutionary, sustainable product that can be created using natural fibers as opposed to their synthetic analogs [21,30].

4.6. Geogrid Tensile Strain

The distribution of the tensile strain of a slope geogrid is larger for the external geogrids close to the slope surface compared to the middle and internal geogrids. The use of a biaxial geogrid layer as part of the soil barrier acts to reduce crack formation in the soil barrier despite differential settlement [4]. Since the measurement of the middle and internal geogrids is parallel to each other, their variation trend is similar, and the tensile strain of the middle geogrids is the highest. In contrast, the tensile strains of the outer and inner geogrids are close to, but lower than, those of the middle geogrids for most of the monitoring period. The variation in moisture content causes the reinforced expansive soil to expand or contract, which in turn causes tensile strain in the geogrids [31]. Several tests were conducted to study the influence of the number of geogrid layers on the footing slope behavior [32]. The geogrid-reinforced surficial soil is expected to undergo volumetric expansion with small horizontal earth pressures, while the soil located at the center of the reinforcement layer is less influenced by the moisture change and therefore less prone to the development of lateral strain [33].

5. Results and Discussion

Given the data from Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4, it can be clearly seen that geo-bags have a clear economic advantage over CC blocks with regard to the protection of riverbanks. The production and disposal costs of CC blocks vary between BDT 284 and 1256 per cm3 and are mainly affected by block sizes, whereas geo-bag prices are much lower and fall in the BDT 238–393 per cm3 range. These advantages, along with the inherently lower production and handling costs and the on-site filling and installation capability, make geo-bags a very attractive, scalable solution for large-scale protection systems. Therefore, the cost of geo-bags is seen to be a more sustainable option for emerging economies such as coastal Bangladesh. Data also verify that geo-bags which are properly filled and placed can resist hydraulic forces similar to those experienced by heavier rigid materials and at the same time maintain the configurational flexibility and the ability to dissipate energy during surge events.

Section 2.5 indicates that deep channel scours, with values between (−13 m and −17 m RL), indicate high-energy flow regimes in which toe protection becomes essential. The presence of V-shaped cross-sections relating to the steepness of the bed gradient is taken as an indicator of active erosion potential; therefore, installation of geo-bags and CC units within these critical zones has led to successful stabilization of the banks, especially along the Koyra Rai river reach (CH 17 + 150 to 18 + 50 km). A comparative study shows that geo-bag-based revetments are a technically feasible and economically beneficial method to control erosion of riverbanks in riverine zones of the Satkhira Koyra region. Their service life is relatively short, usually five to ten years, but this life can be extended with regular maintenance, as long as ecological balance is maintained. CC block systems remain the solution of choice for high-value infrastructure areas, while geo-bag protection systems are more suited to protecting long reaches of rural rivers, where flexibility and cost-effectiveness are of greater importance. These results indicate that a combination of geogrid base layer and geo-bag installations provides an optimal solution to improve the construction’s hydraulic stability while also promoting ecological sustainability and thus provides an effective long-term erosion control strategy. CC blocks prove to be not enough for emergency dumping purposes. These two types of materials, namely sand-filled geo-bags and cement concrete blocks, both function to protect the riverbank.

6. Conclusions

This study shows that the integrated use of geogrid and geo-bag systems presents a novel concept of riverbank slope stabilization that is cost-efficient and sustainable. By using a geogrid layer as a ground reinforcement base and using sand-filled geo-bags as the main revetment, the hydraulic and geotechnical stability of the riverbank protection is significantly increased. The geogrid system has been developed to disperse shear stresses and subsoil erosion, while the flexible envelope of the geo-bag is optimized to resist hydrodynamic forces like drag, lift, and wave impact to minimize toe scour and bank integrity even in high-energy flow. The service life of the geogrid and geo-bag assembly is relatively shorter than rigid cement–concrete structures; the flexibility, rapid installation, and small maintenance of the geogrid and geo-bag assembly make it an extremely suitable solution for rural and environmentally sensitive locations. Geogrid and geo-bag composites are an environmentally friendly, scalable slope protection and long-term riverbank erosion control method in a sedimentary environment like the coastal area of Bangladesh. Geogrids have great potential to be used as lower-cost alternatives in many engineering problems. In this study, recent developments in geosynthetic products were summarized with a logical emphasis on applications of geosynthetics in reinforced soil structures and in various environmental applications. The production technology of geosynthetic products allows incorporation of the latest advances in material science, which improve performance characteristics. Relative to specimens comprising unreinforced calcareous sand, the reinforced samples exhibit markedly greater strength, with increases reaching 100% in certain specimens subjected to low confining pressure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.H.S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.I.H. and A.S.; data curation, A.H.S.S.; writing—review and editing, P.N.; visualization, A.H.S.S.; supervision, P.N.; methodology, A.S.D. and A.H.S.S.; software, A.H.S.S. and M.I.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for publication was obtained from all identifiable human participants.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shahariar, S.; Sultana, N.; Zobeyer, H. Groynes in Riverbank Erosion Control: An Integrated Hydrodynamic and Morphodynamic Modelling for a Selected Reach of the Padma River. Environ. Earth Sci. 2025, 84, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahian, M.H.; Sara, S.; Turjo, M.; Rahman, M.A.; Mashuk, F. A Case Study of Rahmatkhali Riverbank Erosion: Comparison among Riparian Management, Coir Logs and Geo Bags. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Planning, Architecture and Civil Engineering, Rajshahi, Bangladesh, 12–14 October 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Venkateswarlu, H.; Ujjawal, K.N.; Hegde, A. Laboratory and Numerical Investigation of Machine Foundations Reinforced with Geogrids and Geocells. Geotext. Geomembr. 2018, 46, 882–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, S.; Viswanadham, B.V.S. Hydro-Mechanical Behavior of Geogrid Reinforced Soil Barriers of Landfill Cover Systems. Geotext. Geomembr. 2011, 29, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, M.H.; Akter, J.; Ruknul, M. River Bank Protection Measures in the Brahmaputra-Jamuna River: Bangladesh Experience. In Proceedings of the International Seminar on River, Society and Sustainable Development, Assam, India, 26–29 May 2011; Volume 121, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hakimelahi, N.; Bayat, M.; Ajalloeian, R.; Nadi, B. Effect of Woven Geotextile Reinforcement on Mechanical Behavior of Calcareous Sands. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18, e02014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanasisathit, N.; Chuenjaidee, S.; Voottipruex, P.; Jongpradist, P.; Kalayasri, P.; Jamsawang, P. Field Performance of Erosion Control on Lamtakong Dam Slopes Using Geocell and Ruzi Grass Cover: A Case Study. Geotext. Geomembr. 2025, 53, 1610–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erol, A.; Kaya, Z. Response of Isolated Footing on a Geogrid Reinforced Fill and Undisturbed Peat Subgrade Soil System. Geotext. Geomembr. 2025, 53, 1122–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortellazzo, G.; Russo, L.E.; Busana, S.; Carbone, L.; Favaretti, M.; Hangen, H. Field Trial of a Reinforced Landfill Cover System: Performance and Failure. Geotext. Geomembr. 2022, 50, 655–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.Y.; Yee, T.W. Green Revetment Solutions for Riverbank Erosion Protection. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Geosynthetics, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 16–21 September 2018; pp. 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Dip, M.; Uddin, J.; Hasan, M. Geo-Bags Effects on Meandering Section against Bank Erosion: A Case Study of Dharla River. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Civil Engineering for Sustainable Development, Khulna, Bangladesh, 10–12 February 2022; KUET: Khulna, Bangladesh, 2022. ICCESD-2022-01108-1. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, A.S.; Furtado, I.A.; Fonseca, T.M.; de Oliveira Inacio, V.H.M.; de Almeida, J.R.; de Paula Martins, C. Study of the Application of Geosynthetics in Geotechnical Works. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2025, 1536, 012038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, G.; Roy, A.N.; Sanyal, P.; Mitra, K.; Mishra, L.; Ghosh, S.K. Bioengineering of River Earth Embankment Using Natural Fibre-Based Composite-Structured Geotextiles. Geotext. Geomembr. 2019, 47, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, V.V.B.; Ishwarya, M.V.S.; Jayakrishnan, P.; Sathyan, D.; Muthukumar, S. Applications of Natural Geotextile in Geotechnical Engineering. Mater. Today Proc. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumi, S.; Unnikrishnan, N.; Mathew, L. Durability Studies of Surface-Modified Coir Geotextiles. Geotext. Geomembr. 2018, 46, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Hasan, M.Z. Performance Comparison between Geo-Bag and Cement Concrete Block in River Bank Protection Works. Int. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. Appl. Sci. 2016, 4, 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.S. Riverbank Erosion and Sustainable Protection Strategies. J. Eng. Sci. 2011, 2, 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 13438; Geosynthetics—Screening Test Method for Determining the Resistance to Oxidation. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Myagmar, K.; Darkhijav, B.; Renchin, T.; Chultem, D. Cost-Benefit Analysis for Riverbank Erosion Control Approaches in the Steppe Area. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 9251–9266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babagiray, G.; Akbas, S.O.; Anil, O. Full-Scale Field Impact Load Experiments on Buried Pipes in Geosynthetic-Reinforced Soils. Transp. Geotech. 2023, 38, 100927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Yin, Z.-Y. Bearing Capacity of Strip Footings in Unsaturated Soils Reinforced with Layered Geogrid Sheets Using Upper Bound Method. Geotext. Geomembr. 2025, 53, 405–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.D.V.; Holanda, F.S.R.; Pedrotti, A.; Lino, J.B.; dos Santos Fontes, C.; de Melo, J.C.R.; Marino, R.H.; Boge, G.M. Geogrid-Type Geotextile Made from Typha domingensis Fibers with High Tensile Strength for Erosion Control. Invent. Discl. 2024, 4, 100025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, M.A.H.; Islam, S.M.D.-U.; Azam, G. Exploring Impacts and Livelihood Vulnerability of Riverbank Erosion Hazard among Rural Households along the River Padma of Bangladesh. Environ. Syst. Res. 2017, 6, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, T.W. Geosynthetics for Erosion Control in Hydraulic Environment. In Proceedings of the 5th Asian Regional Conference on Geosynthetics, Bangkok, Thailand, 10–14 December 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hataf, N.; Sayadi, M. Experimental and Numerical Study on the Bearing Capacity of Soils Reinforced Using Geobags. J. Build. Eng. 2018, 15, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabani, S.; She, Y.; Lange, C.F. CFD Modeling of Movement of Geobag for Riverbank Erosion Control Structures. Int. J. Sediment Res. 2025, 40, 690–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetimoglu, T.; Wu, J.T.H.; Saglamer, A. Bearing Capacity of Rectangular Footings on Geogrid-Reinforced Sand. J. Geotech. Eng. 1994, 120, 2083–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, F.Y.; Wang, P.; Cai, Y.Q. Particle Size Effects on Coarse Soil-Geogrid Interface Response in Cyclic and Post-Cyclic Direct Shear Tests. Geotext. Geomembr. 2016, 44, 854–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X. An Assessment of the Geometry Effect of Geosynthetics for Base Course Reinforcements. Int. J. Transp. Sci. Technol. 2012, 1, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Du, C.; Jiang, X.; Yi, F.; Niu, B.; Jiang, J. Model Test Study on Electro-Osmotic Dry Tailings Dams of Conductive Grids. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 196, 106870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kommanamanchi, V.; Chennarapu, H.; Balunaini, U. Mechanistic Evaluation of Biaxial and Triaxial Geogrids and Geocells Reinforcing C&D Waste Aggregate Layers for Sustainable Flexible Pavements. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 497, 143867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.; Xie, Y.; Han, Z.; Zhang, H.; Bai, B.; Lan, S. Hydromechanical Behaviors of Geogrids-Reinforced Expansive Soil Slopes: Case Study and Numerical Simulation. Comput. Geotech. 2024, 174, 106626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamshahi, S.; Hataf, N. Bearing Capacity of Strip Footings on Sand Slopes Reinforced with Geogrid and Grid-Anchor. Geotext. Geomembr. 2009, 27, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.