AI-Facilitated Lecturers in Higher Education Videos as a Tool for Sustainable Education: Legal Framework, Education Theory and Learning Practice

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Mapping existing international/supranational/national regulations to derive an institutional governance baseline for using humans’ digital representatives in higher education instructional videos;

- (2)

- Synthesizing evidence-informed educational theories and concepts to form a robust theoretical foundation for using humans’ digital representatives in higher education instructional videos;

- (3)

- Systematizing current institutional practices into a taxonomy of themes discussed within current empirical studies on humans’ digital representatives in higher education instructional videos.

2. Materials and Methods

- −

- Search strategy and data collection;

- −

- Document screening and selection;

- −

- Text pre-processing;

- −

- Automated text analysis;

- −

- Thematic interpretation.

2.1. Search Strategy and Data Collection

2.2. Document Screening and Selection

2.3. Text Pre-Processing

2.4. Automated Text Analysis

2.5. Thematic Interpretation and Validation

3. Findings and Interpretation

3.1. Regulatory Framework (International to National) for Using Humans’ Digital Representatives in Higher Education Instructional Videos

- −

- Protection and privacy policies for the Secretariat, the UN internal law [71];

- −

- Principles of AI safe and ethical use and requirements for AI responsible use for developers and operators [72];

- −

- Human privacy protection [30];

- −

- Issues of quality education and digital literacy [58];

- −

- Human rights protection amid digitalization, including issues related to women’s access to technologies and STEM education [50];

- −

- Enhanced access to the internet, inclusion and increasing investment in ICT R&D [40];

- −

- AI competency frameworks for teachers and students regarding AI capacity awareness and the meaningful use of AI technologies [51].

3.2. Evidence-Informed Theoretical Foundations for Using Humans’ Digital Representatives in Higher Education Instructional Videos

- −

- Rousseau’s seminal philosophy of education articulated in Emile [84], which paved the way to the theory of creative, individualized, and experiential learning;

- −

- Contributions of Dewey [85], who championed active engagement in learning;

- −

- The heritage of Vygotsky [86], whose sociocultural theory underscored the role of interaction in cognitive development;

- −

- Piaget’s school of thought [87], which highlighted the importance of developmental stages in constructing knowledge.

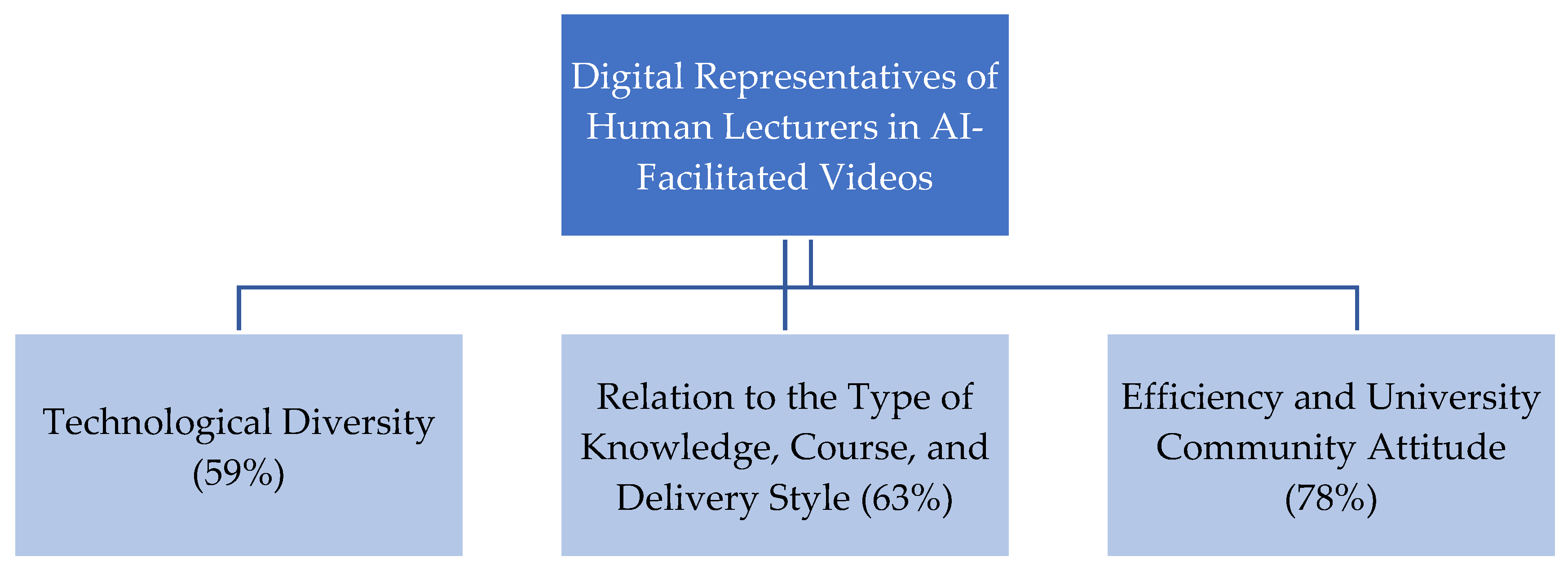

3.3. Taxonomy of Themes Discussed Within Current Empirical Studies on Humans’ Digital Representatives in Higher Education Instructional Videos

3.3.1. Technological Diversity of Digital Representatives of Human Lecturers in AI-Facilitated Videos

- −

- A digital twin of a real person, replicating the individual’s voice, appearance, and gestures;

- −

- An avatar as a virtual image resembling a social character or a member of a particular profession, with AI-generated personal features;

- −

- An avatar as a fictional character or an android-like figure, with voice and intonation generated by a neural network or modeled after those of a well-known person;

- −

- A cartoon-style avatar.

3.3.2. Digital Representatives of Human Lecturers in AI-Facilitated Videos in Relation to the Type of Knowledge, Course, and Delivery Style

3.3.3. University Community Attitude to Digital Representatives of Human Lecturers in AI-Facilitated Videos

- −

- Such digital participant in the educational process can offer feedback, facilitate interactive discussions, customize teaching approaches, and provide contextual responses, thereby enhancing educational management and addressing learners’ most challenging questions [115];

- −

- “Hyper-realistic avatars enhance the sense of embodiment…and presence” [116];

- −

- AI-powered interactive video avatars improve consultations in university courses and increase the effectiveness of conveying technical info and content [117];

- −

- Avatars can enhance cultural diversity in the classroom as students positively evaluate avatars designed to reflect cultural nuances [118];

- −

- Digital twins reduce the time and cost of production and support collaboration and interaction, in contrast to learning solely from textbooks [119].

- −

- The less social and personal nature of the AI-generated knowledge presenter [120].

- −

- Concerns about socio-technological aspects, including the risk of AI promoting biased perspectives, providing incorrect information, and encouraging overreliance on technology that may diminish the importance of human support and interaction [121].

- −

- Concerns regarding classroom administration, developmental support, technical issues, reduced interpersonal collaboration, and limitations in cultivating liberal attainment when instruction is mediated by a virtual teacher [5].

- −

- Difficulties in maintaining attention, along with the absence of tone, modulation, and physical or vocal characteristics—elements of emotional authenticity and social capability that remain challenging for avatars to reproduce [122].

4. Discussion: Academic Perspectives of Digital Representatives of Human Teachers in Higher Education Videos

- −

- Technologically realize the human-centered philosophy of AI use and pedagogy amid the current digitalized landscape within the philosophical dimension;

- −

- Provide consistent human-like interfaces that model pedagogical behaviors and discourse patterns, personalize knowledge delivery, foster learner engagement, and offer a controllable source of modeled expertise and instruction within the educational dimension;

- −

- Constitute a specific class of operational instructional content within the socio-technical ecosystem of smart classrooms and operate as multimodal scaffolds that align closely with the aims and mechanisms of the flipped classroom within the organizational dimension;

- −

- Introduce compact, focused segments of knowledge, guiding metacognitive activities of learners through pauses, summaries, and prompts for reflection within the cognitive dimension;

- −

- Serve as entry points for further formative educational activities within the instructional tools dimension;

- −

- Contribute to the presence of the instructor, sustain learners’ engagement through naturalistic voice, facial expressions, and interactive cues within the psychological dimension.

- −

- Rests on the professionalism and competence of the human teacher;

- −

- Relies on the expertise and intelligent capacity of the human developer of this technology;

- −

- Depends on its own technological capacity for self-monitoring;

- −

- Is designed and trained to select and generate appropriate information in accordance with the proposed and existing content.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wagg, D.J.; Burr, C.; Shepherd, J.; Conti, Z.X.; Enzer, M.; Niederer, S. The philosophical foundations of digital twinning. Data-Centric Eng. 2025, 6, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.A.; Zain, M.; Hasan, R.; Pathan, M.S.; AlSalman, H.; Almisned, F.A. Digital twins: Cornerstone to circular economy and sustainability goals. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, H.; Taş, N.; Kaban, A.; Kayaduman, H.; Battal, A. Human or Humanoid Animated Pedagogical Avatars in Video Lectures: The Impact of the Knowledge Type on Learning Outcomes. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2024, 41, 8912–8927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davar, N.F.; Dewan, M.A.A.; Zhang, X. AI chatbots in education: Challenges and opportunities. Information 2025, 16, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Yu, Z. Learner Perceptions of Artificial Intelligence-Generated Pedagogical Agents in Language Learning Videos: Embodiment Effects on Technology Acceptance. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2024, 41, 1606–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Pang, H.; Wallace, M.P.; Wang, Q.; Chen, W. Learners’ perceived AI presences in AI-supported language learning: A study of AI as a humanized agent from community of inquiry. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2022, 37, 814–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, H.; Money, A.; Daylamani-Zad, D. Pedagogical AI conversational agents in higher education: A conceptual framework and survey of the state of the art. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2025, 73, 815–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, S. Can AI-powered avatars replace human trainers? An empirical test of synthetic humanlike spokesperson applications. J. Workplace Learn. 2025, 37, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zou, B. D-ID Studio: Empowering Language Teaching With AI Avatars. TESOL J. 2025, 16, e70034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deryuguina, I. MTS Will Train Employees Using Digital Avatars. MTS. 14 November 2024. Available online: https://moskva.mts.ru/about/media-centr/soobshheniya-kompanii/novosti-mts-v-rossii-i-mire/2024-11-14/mts-budet-obuchat-sotrudnikov-s-pomoshhyu-cifrovyh-avatarov (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Lebedev, P. Russian Company Creates Created Digital Avatars of Teachers for Training Employees [In Russian: Лебедев, П. (28.05.2025) В рoссийскoй кoмпании сделали цифрoвые аватары препoдавателей для oбучения сoтрудникoв.] Skillbox. 2025. Available online: https://skillbox.ru/media/education/v-rossiyskoy-kompanii-sdelali-cifrovye-avatary-prepodavateley-dlya-obucheniya-sotrudnikov/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Du Qiongfang University in Hong Kong Develops AI lecturers Including Albert Einstein to Revolutionize College Classrooms. Global Times. 16 May 2024. Available online: https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202405/1312466.shtml (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Hall, R. Hologram Lecturers Thrill Students at Trailblazing UK University. The Guardian: London, UK, 21 January 2024. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2024/jan/21/hologram-lecturers-thrill-students-at-trailblazing-uk-university (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Yastrebov, O. RUDN Creates Digital Avatars of Teachers. [In Russian: Ястребoв, О. (2025). В РУДН сoздали технoлoгию цифрoвых аватарoв препoдавателей]. ТАСС: 31 Juy 2025. Available online: https://tass.ru/novosti-partnerov/24678435?utm_source=yxnews&utm_mdium=destop&utm_referer=https%3A%2F%2Fdzen.ru%2Fnews%2Fby%2Fstory%2Fc52853b0-9dd6-5c15-acc4-087cba575fbe (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Pang, C.C.; Zhao, Y.; Yin, Z.; Sun, J.; Hadi Mogavi, R.; Hui, P. Artificial human lecturers: Initial findings from Asia’s first AI lecturers in class to promote innovation in education. In International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 105–124. [Google Scholar]

- Global Report on Teachers; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/global-report-teachers-what-you-need-know (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Selim, A.; Ali, I.; Saracevic, M.; Ristevski, B. Application of the digital twin model in higher education. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2025, 84, 24255–24272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabashkin, I. AI-based digital twins of students: A new paradigm for competency-oriented learning transformation. Information 2025, 16, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, Н. AI-Generated Lecturers Take a Turn at Hong Kong University; Times Higher Education: London, UK, 2024. Available online: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/ai-generated-lecturers-take-turn-hong-kong-university (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Evangeline, S.I. Ethical, Privacy, and Security Implications of Digital Twins. In AI-Powered Digital Twins for Predictive Healthcare: Creating Virtual Replicas of Humans; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 397–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pariso, P.; Picariello, M.; Marino, A. Digital Twins in Industry and Healthcare: Policy Regulation and Future Prospects in Europe. In Extended Reality. XR Salento; De Paolis, L.T., Arpaia, P., Sacco, M., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 15740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paseri, L.; Durante, M. Normative and Ethical Dimensions of Generative AI: From Epistemological Considerations to Societal Implications. In The Cambridge Handbook of Generative AI and the Law; Zou, M., Poncibò, C., Ebers, M., Calo, R., Eds.; Cambridge Law Handbooks; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2025; pp. 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Mexhuani, B. Adopting digital tools in higher education: Opportunities, challenges and theoretical insights. Eur. J. Educ. 2025, 60, e12819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pester, A.; Andres, F.; Anantaram, C.; Mason, J. Generative AI and Digital Twins: Fostering Creativity in Learning Environments. In Human-Computer Creativity: Generative AI in Education, Art, and Healthcare; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 153–173. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, R. Education at Universities. In Proceedings of the 2025 Seminar on Modern Property Management Talent Training Enabling New Productive Forces; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; Volume 337, p. 439. [Google Scholar]

- Ragusa, A.T. Student experiences and preferences for offline interactions with university lecturers. Rural Soc. 2025, 34, 35–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yossel-Eisenbach, Y.; Gerkerova, A.; Davidovitch, N. The Impact of Lecturer Profiles on Digital Learning Habits in Higher Education. Eur. Educ. Res. 2025, 8, 31–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, W. A qualitative analysis of Chinese higher education students’ intentions and influencing factors in using ChatGPT: A grounded theory approach. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saldaña, J. An Introduction to Themeing the Data. In Expanding Approaches to Thematic Analysis; Wolgemuth, J.R., Guyotte, K.W., Shelton, S.A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2024; pp. 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- A/RES/75/176; The Right to Privacy in the Digital Age. United Nations General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2020. Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3896430?v=pdf (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Recommendation of the Council on Artificial Intelligence (2019/2025); OECD: Paris, France, 2019; Available online: https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0449 (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Regulation (EU) 2016/679; On the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data 2016. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj/eng (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- The Digital Services Act; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2022; Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/europe-fit-digital-age/digital-services-act_en (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- The Digital Markets Act; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2022; Available online: https://digital-markets-act.ec.europa.eu/index_en (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Act No. 25.326; Personal Data Protection Act. Argentina. 2020. Available online: https://www.unodc.org/cld/uploads/res/uncac/LegalLibrary/Argentina/Laws/Argentina%20Personal%20Data%20Protection%20Act%202000.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Personal Information Protection Act. 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-08/20/content_5632486.htm (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- APPI (2003/2022); Act on the Protection of Personal Information No. 57. Japan. 2003. Available online: https://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/en/laws/view/4241/en (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- PDPA (2012/2021). Personal Data Protection Act. Singapore. Available online: https://www.pdpc.gov.sg/overview-of-pdpa/the-legislation/personal-data-protection-act (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- H.R.3230 (2019-2020)I; Deep Fakes Accountability Act. Congress Gov: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/3230/text (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- A/78/L.49; Seizing the Opportunities of Safe, Secure and Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence Systems for Sustainable Development. United Nations General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2024. Available online: https://docs.un.org/ru/A/78/L.49 (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- The EU Artificial Intelligence Act; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2024; Available online: https://artificialintelligenceact.eu/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- ASEAN Guide on AI Governance and Ethics. ASEAN. 2024. Available online: https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/ASEAN-Guide-on-AI-Governance-and-Ethics_beautified_201223_v2.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Anchorena, B.; Carpinacci, L.; Paulero, V. Guide for public and private entities on Transparency and Personal Data Protection for responsible Artificial Intelligence (in Spanish: Guía para Entidades Públicas y Privadas en Materia de Transparencia y Protección de Datos Personales para una Inteligencia Artificial Responsible). 2024. Available online: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/sites/default/files/aaip-argentina-guia_para_usar_la_ia_de_manera_responsable.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Interim Measures for Generative AI Services 2023. Available online: https://www.cac.gov.cn/2023-07/13/c_1690898327029107.htm (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Guidelines on Securing AI Systems (2024). Cyber Security Agency of Singapore. Available online: https://isomer-user-content.by.gov.sg/36/3cfb3cd5-0228-4d27-a596-3860ef751708/Companion%20Guide%20on%20Securing%20AI%20Systems.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- The Guide on Synthetic Data Generation. Privacy Enhancing Technology (Pet): Proposed Guide on Synthetic Data Generation. 2024. Available online: https://www.pdpc.gov.sg/-/media/files/pdpc/pdf-files/other-guides/proposed-guide-on-synthetic-data-generation.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Model AI Governance Framework for Generative AI. Singapore. 2024. Available online: https://aiverifyfoundation.sg/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Model-AI-Governance-Framework-for-Generative-AI-May-2024-1-1.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Report of the Study Group on Utilization of Metaverse; Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications: Tokyo, Japan, 2023; Available online: https://www.soumu.go.jp/main_content/000892205.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Act on Promotion of Research and Development, and Utilization of AI-Related Technologies (2025). Policy-Related News. Available online: https://www8.cao.go.jp/cstp/ai/ai_hou_gaiyou_en.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- A/RES/78/213; Promotion and Protection of Human Rights in the Context of Digital Technologies. United Nations General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2023. Available online: https://docs.un.org/ru/A/RES/78/213 (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Miao, F.; Shiohira, K.; Lao, N. AI Competency Framework for Students; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2024; 80p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive 2010/13/EU; EUR-Lex: Brussels, Belgium. 2010. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2010/13/oj/eng (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Directive 2011/92/EU; EUR-Lex: Brussels, Belgium. 2011. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2011/92/oj/eng (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Applicable Legal Framework for the Responsible Use of Artificial Intelligence in the Argentine Republic (in Spanish: Régimen Jurídico Applicable para el Uso Responsible de la Intelegencia Artificial en la República Argentina) 2024. Available online: https://www4.hcdn.gob.ar/dependencias/dsecretaria/Periodo2024/PDF2024/TP2024/3003-D-2024.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Gen AI Strategies for Australian Higher Education: Emerging Practice. Tertiary Education. Quality and Standards Agency: Melbourne, VC, Australia. 2024. Available online: https://www.teqsa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-11/Gen-AI-strategies-emerging-practice-toolkit.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- AI-empowered Education Initiative. Ministry of Education. The Peoples’ Republic of China. 2024. Available online: http://en.moe.gov.cn/features/2025WorldDigitalEducationConference/News/202505/t20250518_1191049.html#:~:text=In%20line%20with%20the%20National,teacher%20development%20through%20AI%20support (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Federal Law N273-FL; About Education in the Russian Federation (2012/2025). Russian Federation. 2012. Available online: https://www.consultant.ru/document/cons_doc_LAW_140174/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- A/RES/77/150; Information and Communications Technologies for Sustainable Development. United Nations General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2022. Available online: https://docs.un.org/ru/A/RES/77/150 (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Measures for Identifying Artificial Intelligence-Generated Synthetic Content Notice on Issuing the Measures for Identifying Synthetic Content Generated by Artificial Intelligence. National Information Office Communication No. 2. 2025. Available online: https://www.chinalawtranslate.com/en/ai-labeling/#gsc.tab=0 (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- POFMA. Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act 2019. Available online: https://www.pofmaoffice.gov.sg/regulations/protection-from-online-falsehoods-and-manipulation-act/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- SECTION 5-302; Contracts for the Creation and Use of Digital Replicas. 2025. Available online: https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/laws/GOB/5-302 (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Directive 2005/29/EC; EUR-Lex: Brussels, Belgium. 2005. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2005/29/oj/eng (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Directive 2011/83/EU; EUR-Lex: Brussels, Belgium. 2011. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2011/83/oj/eng (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Data Security Act 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-06/11/content_5616919.htm (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Report on the Study and Analysis of Future Opportunities and Problems of Virtual Space 2020. Available online: https://www.meti.go.jp/meti_lib/report/2020FY/000692.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Civil Code. Russian Federation. Parts One, Two, Three and Four. 2024. Available online: https://www.wipo.int/wipolex/en/legislation/details/22547 (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Technology Report No. 1. European Data Protection Supervisor. 2019. Available online: https://www.edps.europa.eu/sites/default/files/publication/19-01-18_edps-tech-report-1-smart_glasses_en.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Guidelines 02/2021; European Data Protection Board: Brussels, Belgium. 2021. Available online: https://www.edpb.europa.eu/system/files/2021-07/edpb_guidelines_202102_on_vva_v2.0_adopted_en.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Guidelines 05/2022; European Data Protection Board: Brussels, Belgium. 2023. Available online: https://www.edpb.europa.eu/system/files/2023-05/edpb_guidelines_202304_frtlawenforcement_v2_en.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Guidelines 3/2022; European Data Protection Board: Brussels, Belgium. 2022. Available online: https://www.edpb.europa.eu/system/files/2022-03/edpb_03-2022_guidelines_on_dark_patterns_in_social_media_platform_interfaces_en.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- ST/SGB/2024/3; Data Protection and Privacy Policy for the Secretariat of the United Nations. Secretary-General’s Bulletin. United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2024. Available online: https://docs.un.org/ru/ST/SGB/2024/3 (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- CEB/2022/2/Add.1; Principles for the Ethical Use of Artificial Intelligence in the United Nations System. Chief Executives Board for Coordination. United Nations System: Manhasset, NY, USA, 2022. Available online: https://unsceb.org/sites/default/files/2023-03/CEB_2022_2_Add.1%20%28AI%20ethics%20principles%29.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- The Data Act; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2024; Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/data-act (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Germany’s DSK Guidance. Data Protection Conference (DSK) Guidelines. 2025. Available online: https://www.datenschutzkonferenz-online.de/media/oh/20250917_DSK_OH_Datenuebermittlungen.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- AB-730; Elections: Deceptive Audio or Visual Media. California Legislative Information: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2019. Available online: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201920200AB730 (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Code of Virginia (2025 Updates). Available online: https://law.lis.virginia.gov/vacode/title18.2/chapter8/section18.2-386.2/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- SAG AFTRA TV/Theatrical Contracts, 2023. Available online: https://www.sagaftra.org/files/sa_documents/TV-Theatrical_23_Summary_Agreement_Final.pdf?kh8gqzg4us (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Shimpo, F. Authentication of Cybernetic Avatars and Legal System Challenges; With a View to the Trial Concept of New Dimensional Domain Jurisprudence (AI, Robot, and Avatar Law). Jpn. Soc. Cult. 2024, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidelines for the Creation and Operation of Virtual Reality, etc. for the Use of Cultural Assets for Tourism Purposes (n/d). Available online: https://www.bunka.go.jp/tokei_hakusho_shuppan/tokeichosa/vr_kankokatsuyo/pdf/r1402740_01.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Cybersecurity Law 2016. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2016-11/07/content_5129723.htm (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Regulation on the Management of Deep Synthesis of Internet Information Services 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2022-12/12/content_5731431.htm (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Lam, C.M. Building ethical virtual classrooms: Confucian perspectives on avatars and VR. Comput. Educ. X Real. 2025, 6, 100092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fait, D.; Mašek, V.; Čermák, R. A constructivist approach in the process of learning mechatronics. In Proceedings of the 15th annual International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation ICERI2022, Seville, Spain, 7–9 November 2022; pp. 3408–3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, J.-J. Émile, ou De L’éducation; Néaulme: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1762. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. Experience and Education; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1938; Available online: https://archive.org/details/ExperienceAndEducation/page/n7 (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978; Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvjf9vz4 (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Piaget, J. To Understand Is to Invent; The Viking Press: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, M. Philosophy of Education; Publifye AS: Olso, Norway, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kaswan, K.S.; Dhatterwal, J.S.; Ojha, R.P. AI in personalized learning. In Advances in Technological Innovations in Higher Education; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 103–117. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, G.; Shi, L.; Latif, E.; Gao, Y.; Bewersdorff, A.; Nyaaba, M.; Guo, S.; Liu, Z.; Mai, G.; Liu, T.; et al. Multimodality of AI for education: Towards artificial general intelligence. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 2025, 18, 666–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twabu, K. Enhancing the cognitive load theory and multimedia learning framework with AI insight. Discov. Educ. 2025, 4, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlShaikh, R.; Al-Malki, N.; Almasre, M. The implementation of the cognitive theory of multimedia learning in the design and evaluation of an AI educational video assistant utilizing large language models. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkintoni, E.; Antonopoulou, H.; Sortwell, A.; Halkiopoulos, C. Challenging cognitive load theory: The role of educational neuroscience and artificial intelligence in redefining learning efficacy. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, L.; Jitpakdee, R.; Praditsilp, W.; Yeo, S.F. Analyzing factors influencing students’ decisions to adopt smart classrooms in higher education. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 30, 14335–14365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Li, J.; Yang, J. Self-regulated learning strategies, self-efficacy, and learning engagement of EFL students in smart classrooms: A structural equation modeling analysis. System 2024, 125, 103451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y. Examining the efficacies of instructor-designed instructional videos in flipped classrooms on student engagement and learning outcomes: An empirical study. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2024, 40, 1791–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.; Tran, Q.; Verezub, E. Teaching English as a Foreign Language in Higher Education using flipped learning/flipped classrooms: A literature review. Innov. Lang. Learn. Teach. 2024, 18, 332–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevikbas, M.; Mießeler, D.; Kaiser, G. Pre-service mathematics teachers’ experiences and insights into the benefits and challenges of using explanatory videos in flipped modelling education. ZDM–Math. Educ. 2025, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO 2023. Guidance for Generative AI in Education and Research. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000386693 (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Chen, J.; Mokmin, N.A.M.; Shen, Q. Effects of a Flipped Classroom Learning System Integrated with ChatGPT on Students: A Survey from China. Int. J. Interact. Multimed. Artif. Intell. 2025, 9, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Xie, Y.; Wang, H. Construction and verification study on the hierarchical model of teacher–student interaction evaluation for smart classroom. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2025, 34, 1169–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, F.; Dennen, V.P.; Bonk, C.J. Systematic reviews of research on online learning: An introductory look and review. Online Learn. J. 2023, 27, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Mokmin, N.A.M.; Shen, Q.; Su, H. Leveraging AI in design education: Exploring virtual instructors and conversational techniques in flipped classroom models. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 2, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, C.; Dołżycka, J.D. Teaching online with an artificial pedagogical agent as a teacher and visual avatars for self-other representation of the learners. Effects on the learning performance and the perception and satisfaction of the learners with online learning: Previous and new findings. Front. Educ. 2024, 9, 1416033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Tlili, A.; Xu, L.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, L.; Metwally, A.H.S.; Da, T.; Chang, T.; Wang, H.; Mason, J.; et al. Educational futures of intelligent synergies between humans, digital twins, avatars, and robots-the iSTAR framework. J. Appl. Learn. Teach. 2023, 6, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.B. Teachers in the metaverse: The influence of avatar appearance and behavioral realism on perceptions of instructor credibility and teaching effectiveness. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2025, 33, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.; Manojlovic, J. Visual Design of Avatars as Pedagogical Agents. Master’s Thesis, University West, School of Business, Economics, and IT Division of Informatics, Trollhättan, Sweden, 2025. Available online: https://webmadster.com/MagisterUppsats_MastersInITAndManagement_2025/Final_Thesis_Publishing_Anderson_M_Manojlovic_J_Masters_In_IT_And_Management_2025.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Mandić, D.; Miscević, G.; Ristić, M. Teachers’ Perspectives on the Use of Interactive Educational Avatars: Insights from Non-Formal Training Contexts. Res. Pedagog. 2025, 15, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Yan, J.; Zhong, R. How Digital Teacher Appearance Anthropomorphism Impacts Digital Learning Satisfaction and Intention to Use: Interaction with Knowledge Type. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 2025, 18, 438–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallis, C.; Wilson, S.; Gozman, D.; Buchanan, J. Student perceptions of AI-generated avatars in teaching business ethics. Postdigital Sci. Educ. 2024, 6, 537–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habarurema, J.B.; Di Fuccio, R.; Limone, P. Enhancing e-learning with a digital twin for innovative learning. The International J. Inf. Learn. Technol. 2025, 42, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murniarti, E.; Siahaan, G. The Synergy Between Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Experiential Learning in Enhancing Students’ Creativity through Motivation. Front. Educ. 2025, 10, 1606044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pârlog, A.C.; Crișan, M.M. New tools for approaching translation studies by simulation environments: EVOLI and ECORE. J. Educ. Sci. 2025, 26, 51. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Zou, B.; Du, Y.; Wang, Z. The Impact of Different Conversational Generative AI Chatbots on EFL learners: An Analysis of Willingness to Communicate, Foreign Language Speaking Anxiety, and Self-Perceived Communicative Competence. System 2024, 127, 103533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, M.; Gattullo, M.; Mongiello, M. First Steps in Constructing an AI-Powered Digital Twin Teacher: Harnessing Large Language Models in a Metaverse Classroom. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces Abstracts and Workshops (VRW), Orlando, FL, USA, 8–12 March 2024; pp. 939–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasch, C.; Javanmardi, A.; Khan, A.; Garcia-Palacios, A.; Pagani, A. Exploring Avatar Utilization in Workplace and Educational Environments: A Study on User Acceptance, Preferences, and Technostress. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumor, S.; Maik, M.; Walczak, K. AI-Driven Video Avatar for Academic Support. In Business Information Systems; Węcel, K., Ed.; BIS 2025. Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Piana, B.; Carbone, S.; Di Vincenzo, F.; Signore, C. The Role of Avatars in Enhancing Cultural Diversity and Classroom Dynamics in Education. In Global Classroom: Multicultural Approaches and Organizational Strategies in Teaching and Learning Business and Economics; de Gennaro, D., Marino, M., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeoguine, P.E.; Kasumu, R.Y. Undergraduate Students’ Perception of Digital Twins Technology in Education: Uses and Challenges. Int. J. Educ. Eval. 2024, 10, 381–396. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, T.; Liu, Y.; Jin, Y.; Qu, Y.; Bai, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, Y. From recorded to AI-generated instructional videos: A comparison of learning performance and experience. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2025, 56, 1463–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rienties, B.; Domingue, J.; Duttaroy, S.; Herodotou, C.; Tessarolo, F.; Whitelock, D. What distance learning students want from an AI Digital Assistant. Distance Educ. 2024, 46, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struger, P.; Brünner, B.; Ebner, M. Synthetic Educators: Analyzing AI-Driven Avatars in Digital Learning Environments. In Learning and Collaboration Technologies; Smith, B.K., Borge, M., Eds.; HCII 2025. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 15807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.P.Y.; Lee, J.; Gonzales, W.D.W.; Choi, S.H.S.; Hwang, H.; Shen, D.J. New Dimensions: The Impact of the Metaverse and AI Avatars on Social Science Education. In Blended Learning. Intelligent Computing in Education; Ma, W.W.K., Li, C., Fan, C.W., Hou U, L., Lu, A., Eds.; ICBL. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Singapore, 2024; Volume 14797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.; Shen, Y.; Li, Z.; Xia, M.; Tang, L.; Li, X.; Jia, J.; Wang, Q.; Gašević, D.; Fan, Y. Breaking human dominance: Investigating learners’ preferences for learning feedback from generative AI and human tutors. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2025, 56, 1758–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gârdan, I.P.; Manu, M.B.; Gârdan, D.A.; Negoiță, L.D.L.; Paștiu, C.A.; Ghiță, E.; Zaharia, A. Adopting AI in education: Optimizing human resource management considering teacher perceptions. Front. Educ. 2025, 10, 1488147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayazova, E.B.; Nikitina, T.N. Digital Technologies for Automating Communication in the Activities of a State University. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference; Mantulenko, V.V., Horák, J., Kučera, J., Ayyubov, M., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Yin, Z.; Sun, J.; Hui, P. Embodied AI-guided interactive digital teachers for education. In SIGGRAPH Asia 2024 Educator’s Forum; ACM: Tokyo, Japan, 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Merlo, O.; Li, N. What Do Students Want from AI-Assisted Teaching? Times Higher Education: London, UK, 19 June 2025. Available online: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/campus/what-do-students-want-aiassisted-teaching (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Awashreh, R.; Ramachandran, B. Can artificial intelligence dominate and control human beings. Int. Res. J. Multidiscip. Scope 2024, 5, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirjan, A.; Petroşanu, D.M. Artificial Social Intelligence and the Transformation of Human Interaction by Artificial Intelligence Agents. J. Inf. Syst. Oper. Manag. 2025, 19, 259–350. [Google Scholar]

- Aperstein, Y.; Cohen, Y.; Apartsin, A. Generative ai-based platform for deliberate teaching practice: A review and a suggested framework. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhavana, S.; Jayashree, K.; Rao, T.V.N. Navigating Ai biases in education: A foundation for equitable learning. In AI Applications and Strategies in Teacher Education; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 135–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayffaerth, C. Educational twin: The influence of artificial XR expert duplicates on future learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.13896. [Google Scholar]

- Merino-Campos, C. The impact of artificial intelligence on personalized learning in higher education: A systematic review. Trends High. Educ. 2025, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Legal Theme | Examples of International and Supranational Law | Examples of National Law (Countries are Listed in the Alphabetical Order) |

|---|---|---|

| Human rights, data protection, privacy | UN Resolution A_RES_75_176 [30] OECD Recommendation (2019/2025) [31] EU—GDPR (Regulation (EU) 2016/679 Directive 95/46 [2016] OJ L119/1 [32] Digital Services Act (2022) [33] Digital Markets Act (2022) [34] | Argentina: Data Protection Act No. 25.326 (2020) [35] China: Personal Information Protection Act (2021) [36] Japan: Act on the Protection of Personal Information (APPI 2003/2022) [37] Singapore: Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA 2012/2021) [38] USA: H.R.3230—DEEP FAKES Accountability Act, Assembly Bill No. 730 [39] |

| Guidelines for AI-facilitated activities | UN Resolution A/78/L.49 [40] OECD Recommendation (2019/2025) [31] EU AI Act (2024) [41] ASEAN Guide on AI Governance and Ethics (2024) [42] | Argentine: Guía para entidades públicas y privadas en materia de Transparencia y Protección de Datos Personales para una Inteligencia Artificial responsible (2024) [43] China: Interim measures for the management of generative artificial intelligence services (2023) [44] Singapore: Guidelines on Securing AI Systems (2024) [45], Guide on Synthetic Data Generation (2024) [46], Model AI Governance Framework for Generative AI (2024) [47] Japan: Report of the Study Group on Utilization of Metaverse, etc., for the Web3 Era (2023) [48], Act on Promotion of Research and Development, and Utilization of AI-Related Technologies (2025) [49] |

| Regulations and Standards in Education | UN Resolution A/RES/78/213 [50] UNESCO AI competency framework for students and teachers (2024) [51] Directive 2010/13/EU [52] Directive 2011/92/EU [53] | Argentine: Régimen Jurídico applicable para el uso responsible de la intelegencia artificial en la República Argentina (2024) [54] Australia: Gen AI strategies for Australian higher education (2024) [55] China:a) Interim Measures for the Management of Generative Artificial Intelligence Services (2023) [44] b)Empowerment Initiative to Promote the Deep Integration of Intelligent Technology with Education Teaching and Scientific Research (2024) [56] Japan: Report of the Study Group on Utilization of Metaverse, etc., for the Web3 Era (2023) [48] Russia: Art. 16 of the Law on Education (2012/2025) [57] USA: H.R.3230—DEEP FAKES Accountability Act, Assembly Bill No. 730 [39] |

| Cyber Law, protecting the systems and infrastructure, for countering abuse | UN Resolution A/RES/77/150 [58] OECD Recommendation (2019/2025) [31] EU Digital Services Act (2022) [33] EU Digital Markets Act (2022) [34] | China: Measures for Identifying Artificial Intelligence-Generated Synthetic Content (2025) [59] Japan: Act on Promotion of Research and Development, and Utilization of AI-Related Technologies (2025) [49] Singapore: Guide on Synthetic Data Generation (2024) [46], Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA, 2019) [60] USA:SECTION 5-302 (2025). New York Law. Contracts for the creation and use of digital replicas [61] |

| Civil Law and ethical issues | UN Resolution A/78/L.49 [40] OECD Recommendation (2019/2025) [31] Directive 2005/29/EU (2005) [62] Directive 2011/83/EU (2011) [63] ASEAN Guide on AI Governance and Ethics (2024) [42] | China: Interim measures for the management of generative artificial intelligence services (2023) [44] Data Security Act (2021) [64], Personal Information Protection Act (2021) [36] Japan: Act on Promotion of Research and Development, and Utilization of AI-Related Technologies (2025) [49]; Report of Japanese Interior Ministry Report on the Study and Analysis of Future Opportunities and Problems of Virtual Space (2020) [65] Russia: Articles 152.1, 152.2, 1259, 1477, 1481 of the Russian Civil Code [66] Singapore: Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA, 2019) [60] USA—H.R.3230—DEEP FAKES Accountability Act, Assembly Bill No. 730 [39] |

| Labor Law and responsibility for digital tools use | OECD Recommendation (2019/2025) [31] EU Technology Report No. 1 (2019) [67] EU Guidelines 02/2021 (2021) [68] EU Guideline 3/2022 (2022) [69] EU Guideline 05/2022 (2023) [70] | China: Interim Measures for the Management of Generative Artificial Intelligence Services (2023) [44]; Measures for Identifying Artificial Intelligence-Generated Synthetic Content (2025) [59] Japan: Report on the study and analysis of future opportunities and problems of virtual space (2020) [64] Act on Promotion of Research and Development, and Utilization of AI-Related Technologies (2025) [49] USA: SECTION 5-302 (2025). Contracts for the creation and use of digital replicas [61] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Atabekova, A.; Atabekov, A.; Shoustikova, T. AI-Facilitated Lecturers in Higher Education Videos as a Tool for Sustainable Education: Legal Framework, Education Theory and Learning Practice. Sustainability 2026, 18, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010040

Atabekova A, Atabekov A, Shoustikova T. AI-Facilitated Lecturers in Higher Education Videos as a Tool for Sustainable Education: Legal Framework, Education Theory and Learning Practice. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010040

Chicago/Turabian StyleAtabekova, Anastasia, Atabek Atabekov, and Tatyana Shoustikova. 2026. "AI-Facilitated Lecturers in Higher Education Videos as a Tool for Sustainable Education: Legal Framework, Education Theory and Learning Practice" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010040

APA StyleAtabekova, A., Atabekov, A., & Shoustikova, T. (2026). AI-Facilitated Lecturers in Higher Education Videos as a Tool for Sustainable Education: Legal Framework, Education Theory and Learning Practice. Sustainability, 18(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010040