Abstract

National urban wetland parks serve as key platforms for ecological conservation and recreation, yet the synergistic mechanisms between plant color dynamics and public aesthetic perception remain underexplored. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for evidence-based, climate-resilient landscape design. This study quantifies statistical associations between seasonal color and aesthetic patterns in two national wetland parks (South Dian Lake and Laoyu Lake, Kunming) using Hue–Saturation–Brightness (HSB) color metrics and Scenic Beauty Estimation (SBE) based on year-round monitoring at 24 sample sites. Regression analysis revealed that overall SBE values ranged from −1.027 to 0.756, indicating medium aesthetic quality, with South Dian Lake outperforming Laoyu Lake, particularly in aquatic plant communities. Seasonal trends showed the highest aesthetic preference in winter (orange–yellow dominant, 0.110) and the lowest in early spring (−0.167, yellow dominant), followed by relatively stable values from late spring to mid-autumn (0.007–0.020) and a secondary peak in late autumn (0.029). Higher SBE scores were associated with a dominant hue ratio of 70–75%, balancing color unity and diversity. We identify an operational plant color configuration—70–75% dominant hue, 20% evergreen foliage and 5–7 color types—that corresponds to higher SBE scores. By translating aesthetic responses into quantitative color targets, this study provides guidance for climate-adaptive planting design and seasonal management in subtropical wetland landscapes under global warming.

1. Introduction

Wetlands, often referred to as “the kidneys of the Earth,” play a critical role in maintaining ecological balance, protecting biodiversity and supporting the sustainable development of human societies. They provide habitats for wildlife and deliver essential ecological services, such as flood control, water purification and carbon storage. National urban wetland parks serve as key platforms for protecting and sustainably utilizing wetland resources. They are responsible for ecological conservation while providing public spaces for recreation, scientific education and aesthetic experiences. Plant communities, as core elements of urban wetland parks, exhibit diverse color characteristics shaped by the unique ecological environment of wetlands and vary seasonally, directly influencing the public’s visual experience and aesthetic perception [1]. However, most existing research has primarily focused on the ecological attributes and functional restoration of wetland plants. Systematic investigations of the aesthetic value of wetlands, particularly how plant color shapes public preferences, remain limited. This results in a limited empirical foundation for balancing ecological conservation with visitor preferences and experiences in national wetland parks. Therefore, conducting quantitative research on the color characteristics of wetland plant landscapes is essential for understanding public aesthetic preferences, improving landscape quality and informing park management and design.

Current research on plant coloration primarily focuses on urban environments, such as urban parks [2,3,4,5], university green spaces and forest parks [6,7], whereas studies on plant coloration in wetland parks remain relatively scarce. Internationally, European wetland landscapes have achieved notable progress in color-related monitoring, particularly in the Danube Delta in Romania and Vilmose Fen in Denmark [8,9], where hyperspectral imaging is used to quantify seasonal chlorophyll and carotenoid dynamics for biodiversity and habitat assessment. However, these studies emphasize ecological functions and vegetation health, rather than directly linking plant color patterns to human aesthetic perception. In addition, most existing studies concentrate on seasonal color landscapes in temperate urban green spaces [10,11], with limited attention to the year-round dynamic coloration of subtropical wetlands.

Methodologically, plant coloration research can be broadly divided into color quantification and landscape evaluation approaches. Color quantification methods include color chart sampling, instrumental measurements and software-assisted image analysis [12,13]. The first two approaches are typically suitable for measuring the color of a limited number of plants [14], while software-assisted quantification is more appropriate for large-scale, complex plant communities, enabling efficient processing of extensive plant color data and thus garnering widespread favor among researchers. However, research on color quantification techniques remains in its early stages and a comprehensive, systematic theoretical framework to guide practical applications has yet to be established [15,16]. Landscape aesthetic evaluation methods primarily encompass the Semantic Differential (SD) method, the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) method and the Scenic Beauty Estimation (SBE) method, among others. The SD method is highly subjective and lacks a clear process, while the AHP can be cumbersome in practice. In contrast, the SBE approach is simple, intuitive and effective in capturing public aesthetic perception and has been widely applied in landscape evaluation [17,18,19]. Recent advancements integrate color psychology into these methods, revealing that warm hues (e.g., orange–yellow) evoke positive emotions and higher aesthetic satisfaction in wetland contexts [20,21], while cool tones (e.g., blue–green) enhance perceived tranquility. Eye-tracking studies further demonstrate that color contrast influences visual attention and restoration outcomes in European restored wetlands. Overall, research on plant color in landscape architecture is gradually shifting from purely qualitative descriptions to integrated quantitative/qualitative approaches. Nevertheless, there is still a lack of empirical studies that use quantitative color metrics to identify variances in aesthetic satisfaction and to derive explicit, operational color design targets, particularly in wetland parks.

Against this backdrop, an important research gap emerges in subtropical ‘summerless’ zones regions where mild seasonal temperatures narrow conventional seasonal color transitions, but the visual implications of such muted seasonality remain poorly quantified. Existing studies rarely address how the composition of dominant hue, evergreen foliage, warm–cool balance and color diversity jointly shape scenic beauty under these conditions. Moreover, few works compare wetland parks that share similar macro-climatic conditions but differ in spatial configuration and plant community composition, which is critical for deriving design guidelines rather than site-specific descriptions. There is also a shortage of studies that translate public preference responses into concrete quantitative thresholds for plant color composition that can be directly applied in climate-adaptive wetland design.

To address these gaps, this study selects South Dian Lake National Wetland Park and Laoyu Lake National Wetland Park in Kunming, Southwest China, as case study sites. Both parks are located on the shores of Dian Lake in a subtropical plateau monsoon climate, share similar macro-climatic and hydrological conditions, and are designated national wetland parks with high wetland coverage. At the same time, they differ in spatial layout, restoration stage, and plant community structure, representing two similar but contrasting models of large-scale wetland restoration around Dian Lake. These characteristics make them suitable for examining how plant color composition and seasonal dynamics are associated with public perception under comparable climatic conditions but distinct landscape configurations.

This research represents the first systematic attempt to reveal how color stability, diversity and contrast interact to shape public aesthetic responses under particular climatic conditions. By integrating software-based HSB color quantification with the Scenic Beauty Estimation (SBE) method, the study conducted year-round monitoring in two national wetland parks across 24 representative sites. This combined objective/subjective approach enables precise identification of key color indicators influencing aesthetic evaluation and clarifies the intrinsic relationship between ecological color characteristics and human perception. The core innovation lies in establishing a “color–aesthetics coupling mechanism” specific to subtropical wetland ecosystems, demonstrating that aesthetic preference in these regions is sustained through a dynamic balance of dominant hue ratio, color diversity and seasonal contrast. This framework not only advances the theoretical understanding of aesthetic mechanisms in environments that lack strong seasonal contrast but also provides quantitative design principles for color configuration and adaptive management in subtropical wetland landscapes. Practically, the findings offer a scientific basis for optimizing seasonal color composition to enhance visual appeal and ecological function while reinforcing public engagement and conservation awareness in wetland parks.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Sample Plot Selection

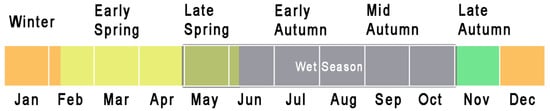

Kunming City is located in the central part of Yunnan Province in Southwest China, within the Dian Lake Basin on the central Yunnan Plateau (24°23′–26°33′ N, 102°10′–103°40′ E). According to the Köppen–Geiger climate classification, Kunming exhibits a Cwa climate type (temperate with dry winters and hot summers), characterized by subtropical plateau features. The climate is mild year-round, with an average annual temperature of 15.9 °C and annual precipitation of 991 mm, featuring distinct dry and wet seasons. Seasons are delineated using the ‘sliding 5-day average temperature method’ based on the ‘Climatic Season Division’ standard [22]. Summer begins on the first day when the average temperature reaches or exceeds 22 °C; winter starts on the first day when it drops to ≤10 °C; and spring or autumn encompasses periods with temperatures between 10 °C and 22 °C. Kunming lacks a period with a 5-day sliding average temperature ≥22 °C, classifying it as part of the “no-summer zone” on the Yunnan–Guizhou Plateau. Consequently, the year comprises only spring, autumn and winter [22] (Figure 1). Furthermore, the wet season extends from May to October, with peak rainfall in July (accounting for approximately 85% of the annual total) and predominantly cloudy weather. In contrast, the dry season is characterized by clear weather.

Figure 1.

Seasonal division map of Kunming.

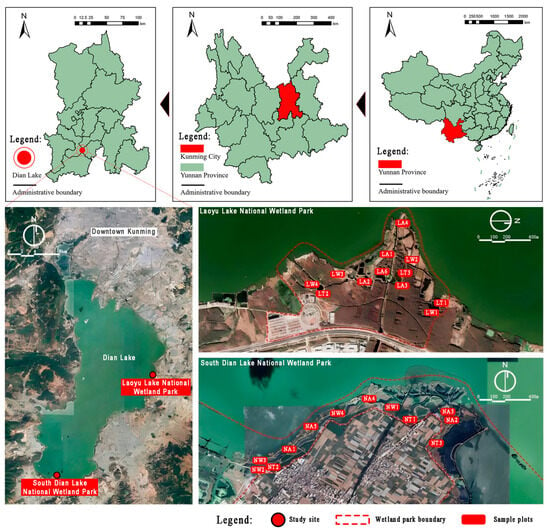

Dian Lake is situated in the southwestern part of Kunming, surrounded by two national wetland parks. South Dian Lake National Wetland Park (hereafter, South Dian Lake) is located on the southern shore of Dian Lake in Jinning District, covering 1220.00 ha with a wetland coverage rate of 91.43%. It was officially designated as Kunming’s first national wetland park in 2019. Laoyu Lake National Wetland Park (hereafter, Laoyu Lake) is positioned on the eastern shore of Dian Lake in Chenggong District, covering a total area of 734.3 ha and a wetland ratio of 72.74%. It was approved as a pilot national wetland park in 2017 and later designated as a national 3A-level tourist attraction. Based on field surveys and plant growth characteristics, typical plant communities exhibiting significant seasonal changes, rich color layers and high ornamental value were selected for study. Each park contributed 24 representative plant communities as study sites. To ensure methodological rigor and reproducibility, algorithm-driven color quantification analysis was implemented in place of manual operations, thereby mitigating reproducibility limitations (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Locations of national wetland parks and sample plots in Kunming. (Sites in South Dian Lake are marked with ‘N’ and those in Laoyu Lake with ‘L’; terrestrial plants with ‘T,’ wetland plants with ‘W,’ and aquatic plants with ‘A’; followed by sequential numbering (1, 2, 3…)).

2.2. Photography

This study spanned the entire year of 2024, with 12 photographic surveys conducted monthly at each of the two parks. Surveys occurred on clear, sunny days with good visibility, from 10:00 to 16:00 [23]. All photographs were taken by the same trained operator using a Canon EOS 5D Mark IV DSLR camera (This equipment is manufactured by Canon Inc., located in Tokyo, Japan) in RAW format, with automatic focus, an aperture of f/11, a fixed white balance of 5500 K and otherwise constant exposure settings across all campaigns. The camera was held at a height of 1.5 m with a horizontal field of view to approximate visitor eye level and to keep the composition comparable among months and plots [15]. Flash was not used, and backlit scenes or frames with obvious blur, strong glare or unstable lighting were avoided. Across the 12 surveys, 836 photographs were obtained. We then applied a two-step screening procedure: first removing technically defective images, and then discarding frames in which the target plant community was heavily occluded or inconsistently framed. The remaining 144 photographs (24 photographs each season), which best represented the seasonal appearance of the plant communities under comparable conditions, were retained for subsequent HSB-based color analysis.

2.3. Scenic Beauty Estimation Method

The SBE method, proposed by Daniel and Boster, is an established approach for objectively measuring landscape aesthetic values through standardized processing of public scoring data [24,25]. This study adhered to SBE standard procedures [26,27,28]. Questionnaires began with five preliminary scoring questions, followed by a random image display, with ≥5 s for viewing and scoring on a 7-point scale (−3 to 3). A total of 600 questionnaires were administered in five batches via the Wenjuanxing 1.2.0.1 online platform: on-site park visitors accessed the survey by scanning a QR code, while additional participants were recruited through shared links. All respondents completed the same online questionnaire using the same image set and instructions, so that the survey mode was consistent across groups. After excluding those with identical scores or excessively short response times, 500 questionnaires were considered as valid (83.3% effective rate)—a sample size deemed sufficient for SBE studies and consistent with similar wetland aesthetic research (n = 300–600) [10,26,29]. Respondents were mainly from Yunnan Province, with a balanced gender ratio (42.1% male, 57.9% female) and broad age coverage: younger than 25 (37.0%), 26–45 (43.3%) and 46 and above (19.7%). Most held college-level or higher education qualifications (83.3%) and 44.6% had landscape-related backgrounds. This demographic structure aimed to achieve representativeness and reliability of aesthetic evaluation results. Reliability was assessed using SPSS 27.0, with Cronbach’s α values exceeding 0.9, to confirm high reliability and internal consistency. To minimize individual differences, scores were standardized using traditional methods [30], with the average standardized beauty score serving as the final result. To reduce individual scoring differences, the study used traditional standardization methods to calculate questionnaire data, as shown in the following formulae:

In the formulae, Zij is the standardized scenic beauty value of the jth evaluator for the ith photo; Rij is the score given by the jth evaluator for the ith photo; is the average score given by the jth evaluator for all photos; Sij is the standard deviation of the scores given by the jth evaluator for all photos. The final result was obtained by averaging the standardized scenic beauty values of all evaluators. Because this procedure yielded relative rather than absolute preference values, the subsequent I–V classes were interpreted as relative aesthetic levels within the evaluated image set, not as universal thresholds of “good” or “bad” landscapes.

2.4. Color Quantization Based on the HSB Model

The HSB color model was selected for this study as it closely aligns with human intuitive perception—hue (H), saturation (S) and brightness (B) directly correspond to non-expert viewers’ color descriptions—making it particularly suitable for landscape aesthetic evaluation [31,32]. In this study, HSB is therefore used as a perceptual, scene-based method of color composition rather than as a high-precision colorimetric space. To mitigate its sensitivity to exposure and illumination, all photographs were taken with fixed camera settings and analyzed in terms of relative pixel proportions in each color class, so that the focus was on seasonal shifts in color structure rather than on absolute color values. Although CIELAB offers superior color gamut accuracy in color science, previous landscape studies have shown that HSB’s intuitive dimensions can better capture public aesthetic responses in complex natural scenes [33]. To control non-plant visual interference, photographs were pre-processed: the sky was uniformly set to white, and non-vegetation elements such as buildings or strong reflections were masked, ensuring that scoring focused on plant community color and structure. Following the quantification method proposed by Yumin Tian [34], a non-uniform color quantification division was adopted, with hue (H) divided into 16 levels, saturation (S) into 4 levels and brightness (B) into 4 levels, thereby dividing the HSB color model into an interval range of H:S:B = 16:4:4. Hue was divided into 16 levels to comprehensively cover major natural color tones, while saturation and brightness were each divided into 4 levels to balance discriminability and computational efficiency. Considering that colors occupying a very small pixel proportion are difficult for the human eye to perceive at the scene scale, this study only retained color classes whose pixel proportion in a given image exceeded 1% and ignored residual colors below this threshold. This procedure avoided over-weighting visually negligible colors and helped maintain consistency in the color metrics. Under these settings, a total of 144 effective color classes occurred in the dataset and were used for subsequent analysis [10,35].

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Quantitative Characteristics of Plant Colors

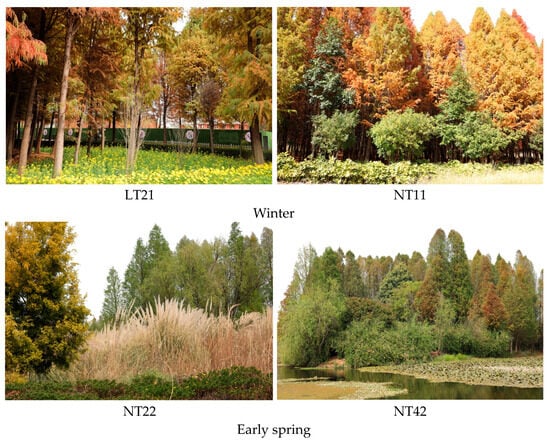

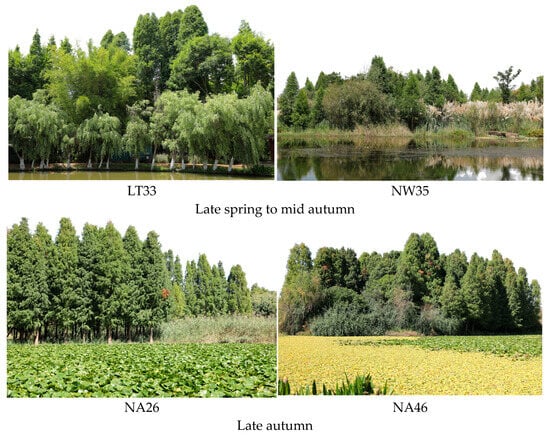

To visually complement the quantitative color analysis, representative photographs of plant combinations with high SBE values for each season are shown to illustrate the corresponding seasonal color patterns (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Plant color combinations with high SBE values for six seasons—winter, early spring, late spring, early autumn, mid autumn and late autumn with LT = Laoyu Lake terrestrial plants, NT = South Dian Lake terrestrial plants, NW = South Dian Lake wetland plants and NA = South Dian Lake aquatic plants. The first digit represents the plot number: terrestrial plant communities are 1, 2, 3; wetland plant communities are 1, 2, 3, 4; and aquatic plant communities are 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. The second digit indicates the survey sequence and season: 1 denotes winter, 2 denotes early spring, 3 denotes late spring, 4 denotes early autumn, 5 denotes mid-autumn and 6 denotes late autumn. Other codes follow the same principle.

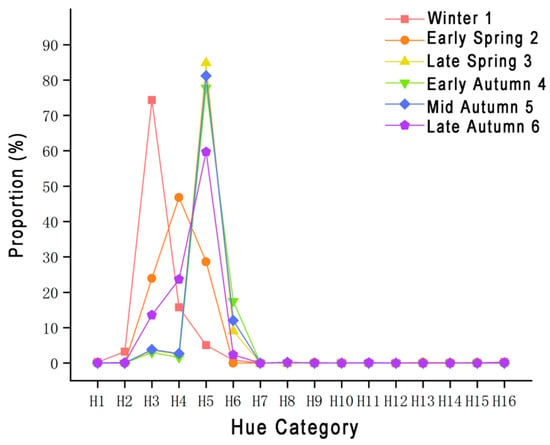

3.1.1. Hue

Kunming National Wetland Park exhibits a diverse array of plant colors year-round, comprising 14 hues on the color wheel (Figure 4). Warm tones predominate in winter, with orange–yellow hues (H3) accounting for 59.91% of photographs, challenging the view of winter as monochromatic. This arises from extensive planting of Taxodium ‘Zhongshanshan’, which displays vibrant foliage in the mild winter. In early spring, yellows (H4) and yellow–green (H5) proportions rise markedly, while orange–yellow hues (H3) decline. Other hues, such as blue–green (H8) and red–purple (H15), remain minimal. In spring, dominant species like T. ‘Zhongshanshan’ and Salix babylonica sprout new leaves, yielding an overall color scheme dominated by bright yellows and yellow–greens. However, balanced proportions lack a dominant color, reducing contrast and layering, thus rendering the landscape visually subdued and underrepresenting spring’s vibrancy. Color distribution remains consistent in late spring to mid-autumn, with yellow–green (H5) dominating (accounting for almost 80% of photographs), followed by green (H6) (accounting for almost 10%), and others minimal. During this period, vigorous growth yields intense yet monotonous colors, lacking dynamic appeal. This pattern is consistent with the relatively stable plant phenology under Kunming’s mild climate and small temperature fluctuations, which may weaken the visual distinctiveness of individual seasons. In late autumn, yellow–green (H5) decreases while yellow (H4) and orange–yellow (H3) increase, shifting colors from cool to warm tones and evoking a rich autumn ambiance.

Figure 4.

Proportion of hue categories in photographs (n = 144, 24 photographs each season).

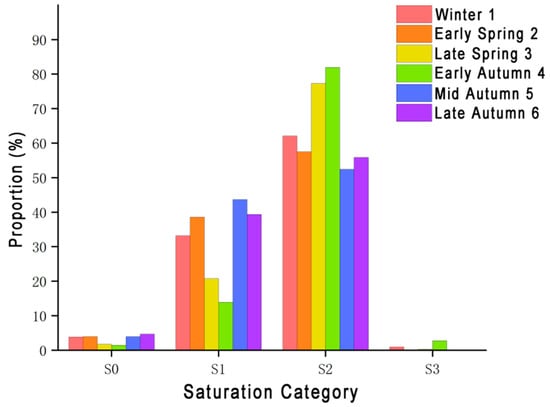

3.1.2. Saturation and Brightness

Regarding color saturation (Figure 5), medium saturation (S2) predominates year-round, generally exceeding 50% of photographs, peaking at around 80% in late spring and early autumn. In these periods, vigorous growth produces vibrant, rich colors. Low saturation (S1) is higher in winter, early spring, late spring and early autumn, when vegetation is emerging or withering, yielding softer colors. Extremely low saturation (S0) remains below 5% all year round. High saturation (S3) is rare, occurring sporadically in winter and early autumn, indicating dominant warm tones but scarce vibrancy. Extremely saturated colors are uncommon in wetland landscapes, where medium-to-low saturation prevails. Within this dataset, overall saturation level ranges from highest to lowest in the following sequence: early autumn > late spring > winter > early spring > mid-autumn > late autumn.

Figure 5.

Proportion of saturation categories in photographs (n = 144, 24 photographs each season).

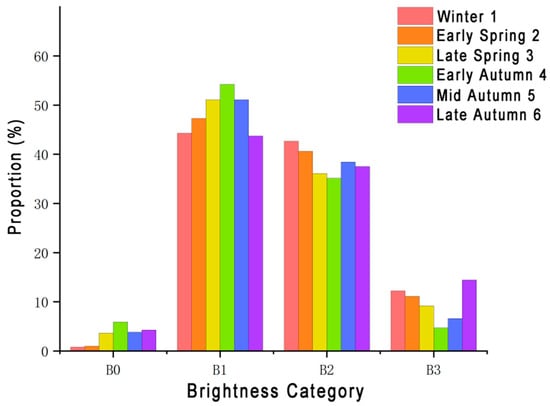

For color brightness (Figure 6), low brightness (B1) predominates throughout the year, generally exceeding 50% of photographs, particularly from late spring to mid-autumn, indicating consistency throughout the growth stages of the dominant plant species. Medium brightness (B2) ranges between 30 and 40%, peaking in winter and early spring. This occurs as primary hues H3 (orange–yellow) and H4 (yellow) exceed H5 (yellow–green) in brightness, adding to winter vibrancy. Extremely low brightness (B0) stays below 10%, peaking in early autumn, likely due to Kunming’s rainy season and dim light. High brightness (B3) is higher (around 15%) in late autumn and winter, attributable to Taxodium ‘Zhongshanshan’ leaf changes and sunnier weather conditions. The seasonal sequence of brightness is late autumn > winter > early spring > late spring > mid-autumn > early autumn.

Figure 6.

Proportion of brightness categories in photographs (n = 144, 24 photographs each season).

3.2. Scenic Beauty Estimation Results

3.2.1. Analysis of Questionnaire Results

Numerous studies indicate that different groups exhibit substantial similarities in landscape aesthetic preferences [36,37,38,39]. However, some studies have pointed out that individual subjective differences, such as professional background, education level and others, may influence judgment results to varying degrees [40,41]. In this survey, proportions of landscape professionals and non-professionals were relatively balanced, with similar standardized scenic beauty values. Professionals showed more pronounced preferences, likely due to expertise in plant arrangement and color layering (Table 1). Overall, these results suggest broad agreement on the relative ranking of scenic quality between the two groups, while not excluding the existence of individual-level preference differences.

Table 1.

Comparative of scenic beauty preferences among different groups.

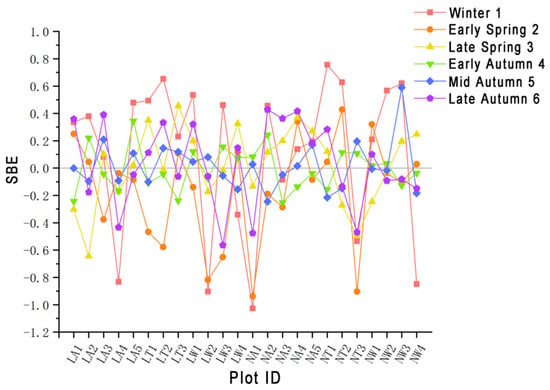

3.2.2. Analysis of SBE

This study employed traditional standardization to compute SBE values for 24 sample plots in Kunming National Wetland Park across six surveys (Figure 7). Results showed SBE values ranging from −1.027 to 0.756 (average: 0.000), indicating average plant landscape aesthetic quality. Winter SBE values fluctuated markedly, with substantial high–low differences, indicating that most plant landscapes in the park were favored by the public. This may stem from the strong visual impact of colored-leaf plants. However, several plots scored extremely low, indicating poor quality. In early spring, SBE values largely turned negative, with few plots positive. Plant dormancy resulted in low-saturation gray-brown dominance, while lacking hue contrast and delayed phenology suppressed expressiveness. SBE values stabilized during late spring, early autumn and mid-autumn, with minimal seasonal fluctuations. Kunming’s mild climate maintained stable yellow–green colors in wetland plants from May to September, resulting in consistent phenology. Aesthetic appeal then depended more on structural layering than hue variation. However, yellow–green uniformity reduced diversity and contrast, diminishing public preferences. In late autumn, SBE values rebounded with noticeable fluctuations, driven by autumn-colored plants expanding warm tones. Hue shifts enhanced layering and alleviated prior monotony.

Figure 7.

Seasonal SBE values for 24 sample plots in six surveys in Kunming National Wetland Park.

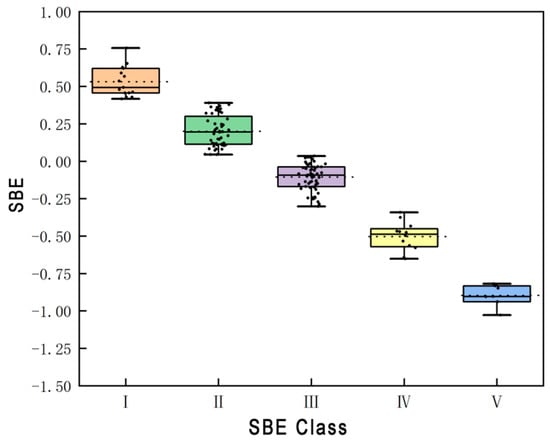

To explore seasonal plant color and scenic beauty relationships, arithmetic methods (Chen, X.Y. 2024) divided 144 photos into five categories: excellent (I), good (II), average (III), poor (IV), very poor (V) [42]. The corresponding SBE value ranges were (0.399, 0.756), (0.042, 0.399), (−0.314, 0.042), (−0.670, −0.314) and (−1.027, −0.670), respectively. Values were distributed uniformly across grades, without outliers (Figure 8). The specific distribution was as follows: 15 excellent (I), 52 good (II), 58 average (III), 12 poor (IV), 7 very poor (V). Most landscapes fell into II and III (good to average), suggesting solid overall scenic value in Kunming Wetland Park, and substantial aesthetic quality. However, some were in IV or V, suggesting that these landscapes might require some enhancement.

Figure 8.

Box plots of SBE values for five categories of scenes in 144 photographs—(I) excellent, (II) good, (III) average, (IV) poor and (V) very poor.

3.3. Correlation Analysis Between Color Factor and Scenic Beauty Estimation

To examine the relationship between plant color characteristics and Scenic Beauty Estimation, this study analyzed 19 color indicators. Color quantity, hue quantity, hue index, saturation index, brightness index, hue ratio, saturation ratio and brightness ratio characterized basic color features. Hue contrast, saturation contrast and brightness contrast expressed visual impact. Dominant hue ratio, green ratio and background ratio depicted color patch characteristics. Cool–warm color ratio, similar color ratio and adjacent color ratio represented color combination characteristics. The color diversity index quantified richness and the color uniformity index assessed uniformity [43,44,45,46]. Standardized SBE values from 24 plots in each season served as the dependent variable, with the color indicators as independent variables. Multiple linear regression analysis was performed using SPSS 27.0 via the backward method to construct regression models for each season.

All models were statistically significant, with adjusted R2 values of 0.468 (winter), 0.323 (early spring), 0.308 (late spring to mid-autumn) and 0.412 (late autumn). Variance inflation factors (VIFs) for all models were below 10, confirming no multicollinearity among indicators. All included factors had p-values < 0.05, denoting significant correlations with SBE values. The maximum standardized residuals were below 3, with no outliers, affirming model robustness.

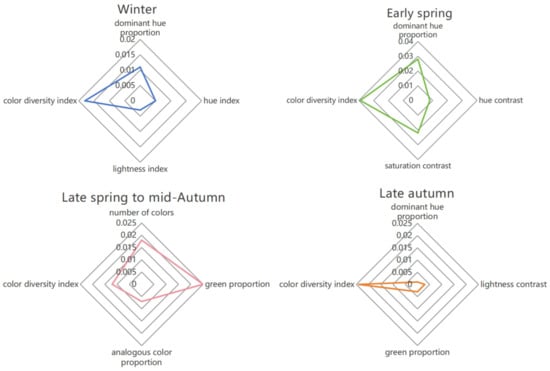

Through multiple regression analysis, four key color factors per season were identified by eliminating variables with low contributions to SBE values. The influence of these factors exhibited significant seasonal variations. In winter, the brightness index exerted the greatest influence, followed by hue index, dominant hue ratio and color diversity index. In early spring, hue contrast predominated, followed by saturation contrast, dominant hue ratio and color diversity index. From late spring to mid-autumn, similar color proportion had the greatest influence, followed by color diversity index, color quantity and green proportion. In late autumn, primary hue proportion showed the strongest influence, followed by green proportion, brightness contrast and color diversity index. A radar chart integrated significance values of key factors for visual comparison (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Seasonal dynamics radar chart of plant landscape color factors.

Kunming’s winter climate (in January) is warm and dry with clear skies. The primary plant species, Taxodium. ‘Zhongshanshan’ exhibits predominantly orange–yellow foliage, contrasting sharply with the monotonous gray-brown landscapes in regions with distinct seasons and highlighting Kunming’s unique scenic beauty. The regression analysis indicates that the brightness index was negatively correlated with SBE scores, implying that higher brightness reduces aesthetic appeal. This may result from intense winter sunlight making high-brightness orange–yellow leaves appear glaring, thus reducing visual comfort. The hue index was also negatively correlated with SBE scores, as higher values (leaning toward green) seemed to diminish the warm atmosphere preferred by the public for orange–yellow tones. The dominant hue ratio showed a significant negative correlation with SBE scores. In Kunming Wetland Park’s winter landscapes, orange–yellow plants dominated, yielding a high dominant hue ratio. Reducing the dominant hue ratio and introducing accent colors could improve public perceptions. The color diversity index was positively correlated with SBE scores, as winter landscape vibrancy relies on species diversity. Increasing plant species diversity in the park could enhance color diversity and public aesthetic experience. Optimization strategies recommend reducing the orange–yellow hue ratio to 70% in winter, increasing evergreen plants to 20% and boosting species richness to enhance ecological visual resilience.

In early spring (in March), temperatures rise and wetland plants enter phenological regrowth, though with low canopy closure, yielding low-saturation, homogeneous color palettes. Findings from this study indicate that, in early spring, leaves have not fully unfurled, with the dominant color (tender yellow leaves) in a small proportion of scenes, with minimal differentiation from other plant colors. Increasing the dominant yellow color proportion could enhance color layering and emphasize the vibrancy of spring. Color contrast rises with plant regrowth, strengthening layers, visual impact and appeal. Saturation contrast was negatively correlated with SBE values. With early spring’s soft tones, excessive saturation disrupts harmony and visual comfort. Thus, low-saturation schemes are recommended. Color diversity increases with regrowth, enriching dynamic changes and experiences to evoke a strong sense of spring vibrancy.

From late spring to mid-autumn (May to September), wetland plant landscapes are dominated by monotonous, stable yellow–green hues. This study indicates that increasing color variety enhances visual diversity and appeal, improving SBE scores. Under H5 (yellow–green) dominance, moderately introducing similar colors H4 (yellow) and H6 (green) can improve harmony. However, excessive colors or green proportions may negatively correlate with SBE scores, causing clutter or monotony, respectively.

In late autumn (in November), cooling temperatures bring out autumn leaf colors. Analysis indicates that increasing the dominant color proportion of yellow–green enhances thematic coherence and orderliness, optimizing aesthetic experiences. Moderately increasing the green proportion adds vibrancy at this time of year, but excess may lead to monotony. Enhancing brightness contrast strengthens layering and visual impact, improving SBE scores. Conversely, excessive color varieties can cause clutter and should be restricted.

4. Discussion

4.1. Landscape Specificity in Climate Blunt Zones

This study examines the unique characteristics of wetland landscapes in subtropical “summerless zones,” highlighting the features observed in Kunming due to its climatic conditions. Kunming experiences an annual temperature difference of approximately 12.1 °C. This narrow climatic gradient causes plants to slowly produce seasonal color changes, leading to a long period of color uniformity of up to five months—a rare phenomenon in subtropical regions. Comparable patterns are also observed in other low-seasonality climates such as the Mediterranean Basin, the Chilean Central Valley and the South African Highveld, where narrow temperature oscillations and high winter sun exposure result in prolonged evergreen or semi-evergreen periods. These parallels are mentioned as qualitative examples; a full bioclimatic comparison is beyond the scope of this study. However, unlike Mediterranean environments dominated by xerophytic shrublands, Kunming’s wetlands retain hydrophilic vegetation with high color saturation during the mild winters [47]. We therefore tentatively describe this as a “humid-type climate-blunt wetland” condition, in which ample moisture allows pigments to remain active despite a reduced phenological amplitude. This is intended as a heuristic ecological–aesthetic category rather than as a formal bioclimatic unit. In contrast, temperate wetlands with distinct seasons, such as Xixi Lake National Wetland Park in Hangzhou, display greater seasonal variation [48,49,50], suggesting that stronger climatic seasonality tends to enhance the visual differentiation of plant landscapes over the year.

Notably, Kunming’s winter wetland landscape presents an “aesthetic paradox,” challenging traditional expectations. In many temperate wetland ecosystems, winter is typically viewed as a “dormant period”, characterized by bare branches, fallen leaves and muted tones. However, Kunming’s mild winter climate offers favorable growth conditions for evergreen species, enabling their orange–yellow hues to retain vibrant visual impact in winter and creating specimens as distinctive focal points. When compared to the evergreen winter patterns of similar Cwa–Cwb climate zones, such as Mexico City or Nairobi, Kunming exhibits higher color diversity but lower seasonal contrast, supporting the assertion that a subdued climate promotes year-round aesthetic continuity while reducing inter-seasonal differentiation. This finding provides empirical grounding for defining “climate subduedness” as a bioclimatic parameter influencing aesthetic dynamics [51,52]. This phenomenon not only challenges the notion that winter landscapes must be bleak but also redefines “seasonal equity” in landscape design. Traditional designs often allocate resources primarily to spring and autumn landscapes, whereas research shows that winter landscapes can also embody key regional characteristics. This paradigm offers essential theoretical support for optimizing subtropical winter landscapes amid climate warming, by harnessing native plants’ climatic adaptability to create a year-round balanced aesthetic plant palette.

However, the same prolonged color-stability period reveals a disadvantage of Kunming’s wetland plant communities, notably in color diversity and layering. Five months of color homogeneity hinder seasonal differentiation, reducing visual distinctiveness and potential visitor experience, ultimately pointing to a potentially more monotonous experience and diminished aesthetic pleasure. The tree layer lacks diversity and depth, while shrubs and groundcovers suffer from a scarcity of vivid species, blurring the ecological connections across the “tree-shrub-herb-aquatic” color interface. The absence of warm-cool color contrasts further limits visual impact, exacerbating monotony.

Based on the analysis of seasonal color optimization strategies for Kunming’s wetland parks, a set of year-round design principles are proposed. The proportion of dominant hues should be maintained at approximately 70–75%, with evergreen species accounting for around 20% and the total number of discernible colors controlled within 5–7. While ensuring distinctive seasonal characteristics, emphasis should be placed on enhancing plant diversity and chromatic layering. The coordinated use of analogous and complementary color schemes is recommended to achieve visual harmony and depth in layering. By combining a rich palette of native trees, shrubs and aquatic plants, the design should highlight hue and brightness contrasts, thereby enhancing spatial hierarchy and visual impact. This ensures that wetland plant colors remain visually attractive while expressing seasonal variation and retaining the natural wildness and local identity of Kunming’s wetlands.

The basic premise of the wetland design guidelines lies in balancing color richness and harmony. During winter, reducing the proportion of orange–yellow tones while integrating evergreen species can enhance the warm-winter atmosphere. In early spring, yellow should dominate, complemented by blue–purple tones to strengthen warm–cool contrast. From late spring to mid-autumn, yellow–green hues should prevail, with darker and lighter greens and flowering plants introduced to alleviate monotony. In late autumn, bright colored leaf species can be used to reinforce the autumnal experience. Through scientifically structured plant community compositions following these seasonal guidelines, Kunming’s wetland parks can achieve landscapes that are chromatically rich, hierarchically layered and regionally distinctive, providing the public with aesthetic and restorative nature-based experiences.

In summary, the proposed color configuration guidelines embody climate-adaptive logic based on maintaining continuity through dominant hue ratios (70–75%), sustaining ecological balance with an approximately 20% evergreen background and introducing controlled seasonal diversity to balance visual dynamism and harmony. This approach not only aims to strengthen aesthetic appeal but also enhances the ecological resilience and identity of subtropical wetland parks within ‘summerless’ regions.

4.2. Synergy Mechanisms Between Ecology and Aesthetics

This study suggests an interesting synergy between ecology and aesthetics in subtropical urban wetlands, highlighting a unique logic in ‘summerless’ climate zones that contrasts with global climatic studies and contributes to theoretical and practical novelty. In Kunming’s wetlands, ecological diversity and aesthetic appeal are closely related. The narrow climatic gradient creates a long period of color consistency, reflecting a synchronized balance between ecological processes and visual experience. Compared to tropical wetlands such as Singapore’s mangroves, which rely on species richness for a “color patchwork” effect [53,54], Kunming achieves visual continuity through subtle changes in the phenological stages of development of dominant species, exemplifying a synergy between ecology and aesthetics in ‘summerless’ climatic zones.

In temperate regions, this synergy often follows a “pulsed” pattern. Research in selected urban wetlands across the United States demonstrates that phenological peaks in growth and development, such as spring budding and autumn leaf coloration, tend to coincide with aesthetic interest, reflecting a concentration of visual and ecological change within short periods. Conversely, Kunming’s relatively “flat” seasonal pattern of change, characterized by low seasonal variation, maintains more constant ecological and aesthetic relationships. Preference data confirm high aesthetic scores even during perceived periods of subdued ecological change, affirming the resilience of this synergy under milder climatic conditions.

This research does not aim to separate climate and vegetation composition as independent drivers of visitor preferences. Rather, climate is regarded as a background constraint that shapes the range of possible phenological and color dynamics, while vegetation composition and design choices provide the proximate levers through which ecological and visual goals are jointly achieved. In contrast to European temperate wetlands that often prioritize biodiversity restoration and some Southeast Asian tropical wetlands that focus on recreational enhancement [55,56,57,58], the Kunming urban wetlands illustrates that ecological adaptation can drive aesthetic innovation in ‘summerless’ climatic zones. These subtropical wetlands provide an intermediate model where controlled color diversity substitutes for a singular focus on biological diversity in maintaining both ecological resilience and aesthetic appeal.

5. Conclusions

This study combines HSB-based color metrics with Scenic Beauty Evaluation (SBE) to investigate the relationship between seasonal plant coloration and public preferences in designed urban wetland parks of subtropical countries under “summerless” climatic conditions. The findings reveal that this region exhibits a prolonged period of yellow–green hues with low seasonal color contrast, yet winter landscapes receive high visitor preference scores, early spring scores are low, and other seasons fall within the middle range. Regression analysis indicates that a few color metrics—dominant hue proportion, color diversity and hue/luminance contrast—are key indicators statistically associated with seasonal variations in visitor preference scores.

Based on these findings, a set of climate-adaptive color configuration guidelines for wetland plant composition are proposed. These include the following: (1) maintain a dominant hue proportion of approximately 70–75%; (2) complement with about 20% evergreen background; (3) keep the number of distinguishable colors within a limited range (approximately 5–7 types); and (4) adjust color diversity and contrast for each season. Seasonally, this implies that in early spring, contrast can be enhanced by increasing the proportion of yellow tones and pairing them with restrained blue–purple accents; from late spring to mid-autumn, visual monotony can be alleviated by introducing selected green shades and flowering plants while maintaining overall unity and coherence; and in late autumn, moderately increasing the dominant warm hue and green proportion, together with some brightly colored leaf species, can reinforce the perception of layered autumnal scenery. These guidelines provide practical recommendations for urban wetland park planners and managers in climatic zones with less pronounced seasonal variation. It is suggested that color strategies require seasonal adjustments while establishing a consistent year-round approach that aligns with climatic characteristics, works with locally adaptable plant communities and resonates with visitors’ preferences.

Several limitations were related to this study. Static 2D photographic evaluations may oversimplify nonlinear color perception and emotional responses. Weather and lighting are highly variable over time and affect visual assessment of a scene. The dynamic experience of scale and distance are lost in static 2D photographs compared to on-site experience. Photographs clearly do not capture the multisensory aesthetic experience of a real-world place that influences visitor judgements.

Future research should be conducted in the field to better integrate perception, emotion and cognition to refine this work. Specifically, combining the Semantic Differential (SD) method with the Pleasure–Arousal–Dominance (PAD) model could better quantify subtle emotional responses to color variation, linking objective color indicators with subjective aesthetic preference. Immersive VR experiments and EEG or eye-tracking techniques could further capture dynamic and physiological responses to color stimuli, while machine learning can model nonlinear relationships between color structure and scenic beauty. These approaches will support the development of a “Color–Emotion–Preference” model, providing a potential theoretical basis for predicting public aesthetic responses under varying ecological and climatic conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.J. and D.C.; methodology, L.J. and D.C.; validation, L.J.; formal analysis, L.J.; data curation, D.C.; writing—original draft preparation, L.J.; writing—review and editing, L.J., W.W., G.L. and D.C.; visualization, L.J. and D.C.; project administration, W.W.; funding acquisition, W.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Project: Research on the Landscape Evolution of Riparian Zones in the Dianchi Basin and Its Impact on Ecological Security (Grant No. 51868028).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study according to Legal Regulations https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2023-02/28/content_5743658.htm (accessed on 25 December 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study were obtained through the authors’ questionnaire surveys and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. This includes raw color quantification datasets, SBE questionnaire responses and regression model files. Data sharing is subject to ethical requirements, such as ensuring participant anonymity in aesthetic surveys.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Luo, Y.; He, J.; Long, Y.; Xu, L.; Zhang, L.; Tang, Z.; Li, C.; Xiong, X. The relationship between the color landscape characteristics of autumn plant communities and public aesthetics in urban parks in Changsha, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Hauer, R.J.; Xu, C. Effects of design proportion and distribution of color in urban and suburban green space planning to visual aesthetics quality. Forests 2020, 11, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahnema, S.; Sedaghathoor, S.; Allahyari, M.S.; Damalas, C.A.; El Bilali, H. Preferences and emotion perceptions of ornamental plant species for green space designing among urban park users in Iran. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 39, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y. Leaf color attributes of urban colored-leaf plants. Open Geosci. 2022, 14, 1591–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Mao, M.; Li, C.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, W.; Sui, X.; Li, J.; Ma, J.; Li, Y. Evergreen or seasonal? Quantitative research on the color of urban scenic forests based on stress—Attention. Front. For. Glob. Change 2024, 7, 1495806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.Y.; Zhao, H.Y.; Xia, T.; Hong, L. Survey of Plant Landscapes on College Campuses in Cold Regions and Quantitative Analysis of Color. Mod. Hortic. 2023, 46, 22–25. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Gao, Y.; Ren, Q.; Ge, S.; Wang, B.; Du, C.; Liu, Y.; Kong, D. Evaluation of urban green space plant landscape quality in Zhengzhou city using the AHP-SBE method. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0329119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioana-Toroimac, G.; Zaharia, L.; Moroșanu, G.-A.; Grecu, F.; Hachemi, K. Assessment of restoration effects in Riparian wetlands using satellite imagery. Case study on the lower Danube River. Wetlands 2022, 42, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miettinen, I.; Zhang, C.; Alonso, L.; Fernández-Marín, B.; García-Plazaola, J.I.; Grebe, S.; Porcar-Castell, A.; Atherton, J. Hyperspectral Imaging Reveals Differential Carotenoid and Chlorophyll Temporal Dynamics and Spatial Patterns in Scots Pine Under Water Stress. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 1535–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; Lin, W.; Diao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Lu, Z.; Guo, W.; Wang, Y.; Hu, C.; Zhao, C. Implementation of the visual aesthetic quality of slope forest autumn color change into the configuration of tree species. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.J.; Chen, J.; Li, Q.Y.; Liu, J.C.; Tao, J.P. Color quantification and evaluation of landscape aesthetic quality for autumn landscape forest based on visual characteristics in subalpine region of western Sichuan, China. J. Appl. Ecol. 2020, 31, 45–54. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Grose, M.J. Green leaf colours in a suburban Australian hotspot: Colour differences exist between exotic trees from far afield compared with local species. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 146, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Yao, Y.; Li, C. Quantitative study on landscape colors of plant communities in urban parks based on natural color system and M-S theory in Nanjing, China. Color Res. Appl. 2022, 47, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, W.J.; Huang, D.; Ma, X.L.; Zhang, Q.Z.; Guan, H.Y. Impact of Urban Waterfront Colorscape on Public Mental Health: A Case Study of the Dasha River Eco-Corridor in Shenzhen. J. Chin. Urban For. 2023, 21, 65–73+113. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Cai, J.G. Research Progress in Quantification of Plant Landscape Color. J. Chin. Urban For. 2022, 20, 134–139. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ye, S.Q.; Zhang, L.; Song, Y.H. Progress in Quantitative Research on Landscape Color. Mod. Hortic. 2024, 47, 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, M.M.; Lang, P.J. Measuring emotion: The self-assessment manikin and the semantic differential. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 1994, 25, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Mei, L.; Meng, Y.; Gao, W. Revealing the Relationship Between Urban Park Landscape Features and Visual Aesthetics by Deep Learning-Driven and Spatial Analysis. Buildings 2025, 15, 2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, G.; Lu, Y. Evaluation of urban wetland landscapes based on a comprehensive model—A comparative study of three urban wetlands in Hangzhou, China. Environ. Res. Commun. 2023, 5, 035004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, Y. The influence of visual and auditory environments in parks on visitors’ landscape preference, emotional state, and perceived restorativeness. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neale, C.; Griffiths, A.; Pui, L.; Mendu, S.; Boukhechba, M.; Roe, J. Color aesthetics: A transatlantic comparison of psychological and physiological impacts of warm and cool colors in garden landscapes. Wellbeing Space Soc. 2021, 2, 100038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.E.; Yao, Y.; Peng, Q.Y. Study on the Seasonal Variations of the Climate in Low-Latitude Plateaus: A Case Study of Kunming and Dali in Yunnan Province. J. Trop. Meteorol. 2023, 39, 171–182. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.; Tan, M. The quantitative research of landscape color: A study of Ming Dynasty City Wall in Nanjing. Color Res. Appl. 2018, 43, 436–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, T.C. Measuring Landscape Esthetics: The Scenic Beauty Estimation Method; Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 1976; Volume 167, pp. 1–66. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, T.C. Whither scenic beauty? Visual landscape quality assessment in the 21st century. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2001, 54, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, B.; Gong, L.; Xu, C. Evaluating the scenic beauty of individual trees: A case study using a nonlinear model for a Pinus tabulaeformis scenic forest in Beijing, China. Forests 2015, 6, 1933–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.H.; Gu, X.; Chen, K.; Dong, F.L.; Zhang, L.G.; Jia, X. The status quo and trend of applying SBE in landscape evaluation. J. West China For. Sci. 2019, 48, 148–156. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Qie, G.; Wang, C.; Jiang, S.; Li, X.; Li, M. Relationship between forest color characteristics and scenic beauty: Case study analyzing pictures of mountainous forests at sloped positions in Jiuzhai Valley, China. Forests 2017, 8, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qian, J.; Cao, J.; Fan, R.; Han, X. Quantitative analysis and evaluation of winter and summer landscape colors in the Yangzhou ancient Canal utilizing deep learning. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.W.; Cai, J.G.; Shu, M.Y. A quantitative study on plant color in the autumn plant community of west lake, Hangzhou. J. Anhui Agric. Univ. 2022, 49, 56–61. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild, M.D. Color Appearance Models; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Z.; Fuzong, L.; Bo, Z. A CBIR method based on color-spatial feature. In Proceedings of the IEEE Region 10 Conference, TENCON 99, ‘Multimedia Technology for Asia-Pacific Information Infrastructure’ (Cat. No.99CH37030), Cheju Island, Republic of Korea, 15–17 September 1999; pp. 166–169. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Huang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Fu, W.; Yao, X.; Huang, J.; Lan, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Dong, J. How vegetation colorization design affects urban Forest aesthetic preference and visual attention: An eye-tracking study. Forests 2023, 14, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Lin, G. Retrieval technique of color image based on color features. J. XiDian Univ. 2002, 29, 43–46. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ma, B.; Xu, C.; Cui, Y. Effects of color composition in badaling forests on autumn landscape quality. J. Northwest For. Univ. 2018, 33, 258–264. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Xu, B.; Devereux, B. Assessing public aesthetic preferences towards some urban landscape patterns: The case study of two different geographic groups. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2016, 188, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasser, E.; Lavdas, A.A.; Schirpke, U. Assessing landscape aesthetic values: Do clouds in photographs influence people’s preferences? PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0288424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zanten, B.T.; Zasada, I.; Koetse, M.J.; Ungaro, F.; Häfner, K.; Verburg, P.H. A comparative approach to assess the contribution of landscape features to aesthetic and recreational values in agricultural landscapes. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 17, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Z. Consensus in visual preferences: The effects of aesthetic quality and landscape types. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 20, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirpke, U.; Mölk, F.; Feilhauer, E.; Tappeiner, U.; Tappeiner, G. How suitable are discrete choice experiments based on landscape indicators for estimating landscape preferences? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 237, 104813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tieskens, K.F.; Van Zanten, B.T.; Schulp, C.J.; Verburg, P.H. Aesthetic appreciation of the cultural landscape through social media: An analysis of revealed preference in the Dutch river landscape. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 177, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.Y. Study on the Landscape Evaluation and Optimization of Urban Mountain Park: A Case Study in Fuzhou Jinjishan Park. Master’s Thesis, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, Fuzhou, China, 2020. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Han, W.; Zhang, C.; Wang, C.; Yin, L. Constructing a forest color palette and the effects of the color patch index on human eye recognition accuracy. Forests 2023, 14, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Luo, P.; Yang, H.; Luo, C.; Li, H.; Wu, S.; Cheng, Y.; Huang, Y.; Xie, W. Exploring the relationship between forest scenic beauty with color index and ecological integrity: Case study of Jiuzhaigou and Giant Panda National Park in Sichuan, China. Forests 2022, 13, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Mu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Diao, X.; Lu, Z.; Guo, W.; Wang, Y.; Xu, B. Research on cognitive evaluation of forest color based on visual behavior experiments and landscape preference. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spellerberg, I.F.; Fedor, P.J. A tribute to Claude Shannon (1916–2001) and a plea for more rigorous use of species richness, species diversity and the ‘Shannon–Wiener’Index. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2003, 12, 177–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puglielli, G. Beyond the concept of winter-summer leaves of mediterranean seasonal dimorphic species. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.D.; Li, H.M.; Jin, Y.L.; Shi, Y.; Bao, Z.Y. Study on the diversity and community composition of spontaneous vegetation in herb layer in Hangzhou Xixi National Wetland Park. Zhejiang For. Sci. Technol. 2021, 41, 24–31. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, J. Effect of the urbanization of wetlands on microclimate: A case study of Xixi Wetland, Hangzhou, China. Sustainability 2016, 8, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Dong, J.; He, Q.; Ye, B. The temporal variation of the microclimate and human thermal comfort in urban wetland parks: A case study of Xixi National Wetland Park, China. Forests 2021, 12, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussotti, F.; Pollastrini, M. Opportunities and threats of Mediterranean evergreen sclerophyllous woody species subjected to extreme drought events. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhu, L.; Xu, Q.; Lundgren, M.R.; Yang, K.; Zhao, P.; Ye, Q. Ecophysiological responses of two closely related Magnoliaceae genera to seasonal changes in subtropical China. J. Plant Ecol. 2018, 11, 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemu, J.B.; Richards, D.R.; Gaw, L.Y.-F.; Masoudi, M.; Nathan, Y.; Friess, D.A. Identifying spatial patterns and interactions among multiple ecosystem services in an urban mangrove landscape. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 121, 107042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friess, D.A.; Richards, D.R.; Phang, V.X. Mangrove forests store high densities of carbon across the tropical urban landscape of Singapore. Urban Ecosyst. 2016, 19, 795–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dronova, I.; Taddeo, S.; Harris, K. Plant diversity reduces satellite-observed phenological variability in wetlands at a national scale. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabl8214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, T.; Goldstein, J. Amphibious Land Repair: Restoration, Infrastructure and Accumulation in Southeast Asia’s Wetlands. Environ. Soc. 2024, 15, 110–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Mateos, D.; Power, M.E.; Comín, F.A.; Yockteng, R. Structural and functional loss in restored wetland ecosystems. PLoS Biol. 2012, 10, e1001247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoeven, J.T. Wetlands in Europe: Perspectives for restoration of a lost paradise. Ecol. Eng. 2014, 66, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.