Evaluation of the Effect of Pesticide Packaging Waste Recycling: From Economic and Ecological Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

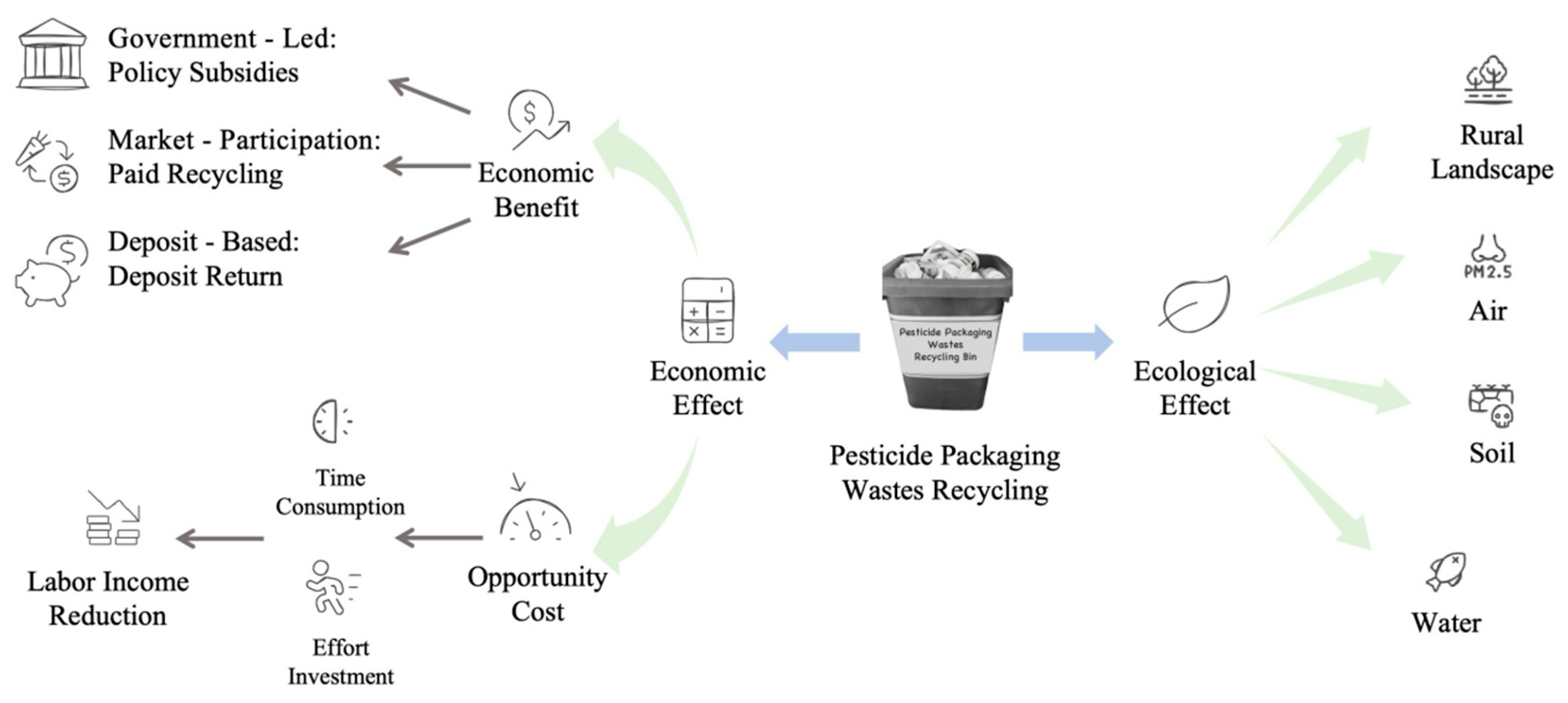

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Data

3.2. Variable Selection and Descriptive Statistics

3.2.1. Dependent Variables

- (1)

- Economic effect: Drawing upon existing research [46], this study measures the economic effect using “annual total household income” (unit: 10,000 CN¥).

- (2)

- Ecological effect: This study constructs an indicator system for the ecological effect based on farmers’ evaluations of the village’s ecological environmental quality, which is measured from three specific aspects. These aspects correspond to the following questions: “How would you rate the quality of the water environment in your village?”, “How would you rate the quality of the soil environment in your village?”, and “How would you rate the quality of the ecological landscape in your village?”. All three items are measured using a five-point Likert scale, where 1 = “Very poor”, 2 = “Relatively poor”, 3 = “Average”, 4 = “Relatively good”, and 5 = “Very good”. A higher score indicates a more positive evaluation of the respective ecological element and better subjective ecological perception. To enhance the scientific validity and objectivity of the indicator weighting, and to avoid index measurement inaccuracies caused by subjective weighting [47], a composite value of the ecological effect is calculated by the Entropy Weight Method (EWM) (Appendix A.1), which is an objective weighting technique.

3.2.2. Explanatory Variables

3.2.3. Covariates

3.3. Model Construction

4. Empirical Results

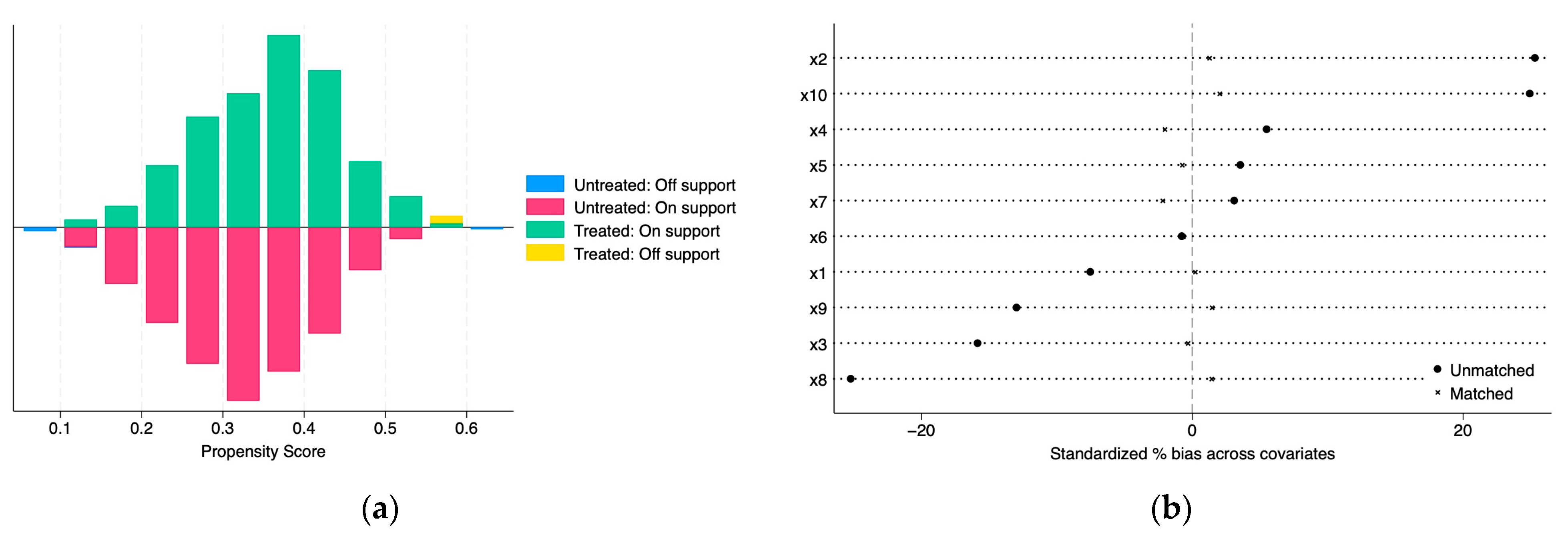

4.1. Common Support Test and PSM Results Analysis

4.2. Balance Test

4.3. The Treatment Effect of PPW Recycling Behavior

4.4. Robustness Test

4.4.1. Sample Selection Bias Test

4.4.2. Instrumental Variable Approach

4.5. Heterogeneity Analysis

- (1)

- Land fragmentation.

- (2)

- Pesticide expenditure.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Entropy Weight Method (EWM)

- (1)

- For the j-th indicator, the relative proportion of the i-th evaluation object is calculated as:

- (2)

- Calculate the entropy value of the j-th indicator:

- (3)

- Calculate the coefficient of information entropy difference for the j-th indicator:

- (4)

- Calculate indicator weights:

- (5)

- Calculate the comprehensive evaluation value:

Appendix A.2. Kernel Matching

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. FAOSTAT Database. 2023. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/RP (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Liu, J.Y.; Chi, S.Y.; Zhao, M.J. The subsidy policies for pesticide packaging waste recycling: Farmers’ preferences and social welfare analysis. J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 3, 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, J.; Xiong, J.; Hong, Y.; Hu, R. Pesticide overuse in apple production and its socioeconomic determinants: Evidence from Shaanxi and Shandong provinces. China J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 315, 128179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, E.; Zhang, H.; Lirong, X.; Khalid, Z.; Xu, H. Understanding cognitive and socio-psychological factors determining farmers’ intentions to use improved grassland: Implications of land use policy for sustainable pasture production. Land Use Policy 2021, 102, 105250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, Y.; Arshad, M.; Mahmood, N.; Kächele, H.; Kong, R. Occupational hazards, health costs, and pesticide handling practices among vegetable growers in Pakistan. Environ. Res. 2021, 200, 111340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbounis, G.; Komilis, D. A modeling methodology to predict the generation of wasted plastic pesticide containers: An application to Greece. Waste Manag. 2021, 131, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Shukla, A.; Attri, K.; Kumar, M.; Kumar, P.; Suttee, A.; Singh, G.; Barnwal, R.P.; Singla, N. Global trends in pesticides: A looming threat and viable alternatives. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 201, 110812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Yang, N.; Li, Y.; Ren, B.; Ding, X.; Bian, H.; Yao, X. Total concentrations and sources of heavy metal pollution in global river and lake water bodies from 1972 to 2017. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 22, e00925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Gao, J.; Wang, H. Research on the recycling and disposal of Chinese pesticide packaging waste based on evolutionary game theory. J. Environ. Sci. Health B 2023, 58, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Kuang, Y.; Li, C.; Sun, M.; Zhang, L.; Chang, D. Waste pesticide bottles disposal in rural China: Policy constraints and smallholder farmers’ behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 316, 128385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.Y.; Ni, Q.; Yao, L.Y.; Lu, W.N.; Zhao, M.J. Calculation of differentiated compensation standards for pesticide packaging waste recycling: An analysis based on 1060 fruit and vegetable growers in Shaanxi Province. China Rural. Econ. 2021, 94–110. [Google Scholar]

- Picuno, C.; Alassali, A.; Sundermann, M.; Godosi, Z.; Picuno, P.; Kuchta, K. Decontamination and recycling of agrochemical plastic packaging waste. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 381, 120965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, N.; Zhang, Q.; Li, C.; Sun, H. Policy Intervention Effect Research on Pesticide Packaging Waste Recycling: Evidence from Jiangsu, China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 922711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.Y. Pesticide Packaging Waste Recycling: Farmers’ Participation and Compensation Design. Ph.D. Thesis, Northwest A&F University, Xianyang, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z.P. Implementing the “Management Measures for the Recycling and Treatment of Pesticide Packaging Waste” to effectively ensure rural ecological security and agricultural production safety. Hubei Plant Prot. 2022, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Abadi, B. Impact of attitudes, factual and causal feedback on farmers’ behavioral intention to manage and recycle agricultural plastic waste and debris. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 424, 138773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondori, A.; Bagheri, A.; Allahyari, M.S.; Damalas, C.A. Pesticide waste disposal among farmers of Moghan region of Iran: Current trends and determinants of behavior. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2019, 191, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Cui, H.; Zong, Y.; Yin, S. Effect of ecoliteracy on farmers’ participation in pesticide packaging waste governance behavior in rural North China. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, J.; Chen, K.; Wu, L. Willingness and behaviors of farmers’ green disposal of pesticide packaging waste in Henan, China: A perceived value formation mechanism perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasha, A.M.; Dominique, A.M.; Sage, W.M.; Shadya, S.M.; Mugisho, J.Z. Pesticide choice and use patterns among vegetable farmers on Idjwi Island, Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. SAGE Open 2023, 13, 21582440231218099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Song, K.; Zhang, K.; Deng, X. Impact of farm size on farmers’ recycling of pesticide packaging waste: Evidence from rural China. Land 2025, 14, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xing, L.; Li, B.; Zhang, Y. Substitution or complementary effects: The impact of neighborhood effects and policy interventions on farmers’ pesticide packaging waste recycling behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 482, 144198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Weng, Z.; Gao, X.; Liao, W. The influence of social norms and environmental regulations on rural households’ pesticide packaging waste disposal behavior. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Xu, C.; Zhu, Z.; Kong, F. How to encourage farmers to recycle pesticide packaging wastes: Subsidies VS social norms. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 367, 133016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damalas, C.A.; Koutroubas, S.D. Farmers’ Training on Pesticide Use Is Associated with Elevated Safety Behavior. Toxics 2017, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truelove, H.B.; Yeung, K.L.; Carrico, A.R.; Gillis, A.J.; Raimi, K.T. From plastic bottle recycling to policy support: An experimental test of pro-environmental spillover. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 46, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moazzem, S.; Wang, L.; Daver, F.; Crossin, E. Environmental impact of discarded apparel landfilling and recycling. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 166, 105338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.H.; Zhou, J.; Ren, M.H. Income effect of green production factor input behavior of agricultural producers. J. Northwest AF Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 24, 110–123. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.M.; Qin, W.J. The Double-Edged Sword Effect of Green Consumption Behavior on Prosocial Behavior: Based on the Mediating Mechanism of Moral Self-Identity and Psychological Provilege. Rev. Econ. Manag. 2024, 40, 112–122. [Google Scholar]

- She, S.X.; Li, S.C.; Chen, J.; Sheng, G.H. Spillover Effect of Digital Green Behavior: Mediation of Identity and Moderation of Psychological Ownership. Psychol. Sci. 2023, 46, 1180–1187. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, X.K.; Liu, T.J.; Huang, T.; Yuan, X.P. Adoption Behavior and Income Effects of Green Agricultural Technology for Farmers. J. Northwest AF Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 19, 121–131. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Park, S.; Yi, H.; Feiock, R. Evaluating the employment impact of recycling performance in Florida. Waste Manag. 2020, 101, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henn, L.; Otto, S.; Kaiser, F.G. Positive spillover: The result of attitude change. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 69, 101429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.Y.; Wang, Q. Effects of interactions of green economic development and government environmental protection behavior. Resour. Sci. 2020, 42, 776–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yan, Q.Y.; Fang, J.P. Effects of residues in four pesticide packaging bags on soil urease activity. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2012, 40, 15256–15258. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H.A. Rational choice and the structure of the environment. Psychol. Rev. 1956, 63, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, J. Pesticide packaging waste recycling: Supportive attitudes and model choices. J. Econ. Manag. 2013, 12, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Picuno, C.; Gerassimidou, S.; You, W.; Martin, O.; Iacovidou, E. The potential of Deposit Refund Systems in closing the plastic beverage bottle loop: A review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 212, 107962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.H. Practical exploration and implications of the “digital + deposit” recycling model for pesticide packaging waste. China Plant Prot. 2023, 43, 108–111. [Google Scholar]

- Gai, H.; Yan, T.W.; Zhang, J.B. Perceived value, government regulation, and farmers’ sustained mechanized straw return behavior: An empirical analysis based on survey data from 1288 households in Hebei, Anhui, and Hubei provinces. China Rural. Econ. 2020, 106–123. [Google Scholar]

- Ansari, I.; El-Kady, M.M.; El Din Mahmoud, A.; Arora, C.; Verma, A.; Rajarathinam, R.; Singh, P.; Verma, D.K.; Mittal, J. Persistent pesticides: Accumulation, health risk assessment, management and remediation: An overview. Desalination Water Treat. 2024, 317, 100274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Choudhary, D.; Bali, S.; Bandral, S.S.; Singh, V.; Ahmad, A.; Rani, N.; Singh, T.G.; Chandrasekaran, B. Pesticides: An alarming detrimental to health and environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 915, 170113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damalas, C.A.; Telidis, G.K.; Thanos, S.D. Assessing farmers’ practices on disposal of pesticide waste after use. Sci. Total Environ. 2008, 390, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohafrash, S.M.; Mossa, A.T.H. Disposal of expired empty containers and waste from pesticides. Egypt. J. Chem. 2024, 67, 65–85. [Google Scholar]

- Mello, M.F.; Scapini, R. Reverse logistics of agrochemical pesticide packaging and the impacts to the environment. Braz. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2016, 13, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.H.; Cai, Y.Y.; Zhu, L.L. Analysis of influencing factors and economic effects of farmers’ participation in farmland transfer. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 2016, 25, 387–394. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, S.; He, M.; Zhang, T.; Huo, Y.; Fan, D. Credibility measurement as a tool for conserving nature: Chinese herders’ livelihood capitals and payment for grassland ecosystem services. Land Use Policy 2022, 115, 106032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.H.; Zhou, H. Can social trust and policy of rewards and punishments promote framer’s participation in recycling of pesticide packaging waste? J. Arid. Land Resour. Environ. 2021, 35, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Huo, X. Estimating the effects of joining cooperatives on farmers’ recycling behaviors of pesticide packaging waste: Insights from apple farmers of China. Cienc. Rural. 2023, 53, e20220229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Rao, F. Sowing the seeds of sustainability: A deep dive into farmers’ recycling practices of pesticide packaging waste in China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1453656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Mi, X. The Influence and Mechanism of Property Right Stability on Agricultural Machinery Service Outsourcing. J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2020, 63–71+171–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Zhai, P.; Zhu, L.; Li, K. Economic Incentives, Reputation Incentives, and Rural Residents’ Participation in Household Waste Classification: Evidence from Jiangsu, China. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Description | Mean | S.D. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | |||||

| Economic effect | Annual total household income (unit: 10,000 CN¥). | 8.47 | 6.96 | 0.1 | 66 |

| Ecological effect | Composite value for village-level water environment, soil environment, and ecological landscape calculated by EWM | 0.79 | 0.20 | 0 | 1 |

| Explanatory variable | |||||

| PPW recycling behavior | Whether recycle PPW (0 = No; 1 = Yes) | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0 | 1 |

| Respondent age | Respondent age (year) | 49.83 | 10.66 | 22 | 76 |

| Gender | Respondent gender (0 = female; 1 = male) | 0.64 | 0.48 | 0 | 1 |

| Education | Education level of respondent (year) | 7.73 | 3.59 | 0 | 16 |

| Health status | Respondent health status (1 = Poor; 2 = Fair; 3 = Good) | 2.78 | 0.49 | 1 | 3 |

| Total household members | Total household members | 4.32 | 1.46 | 1 | 8 |

| Labor force proportion | Labor force members/Total household members | 0.83 | 0.19 | 0.2 | 1 |

| Poverty status | whether the household has been lifted out of poverty (0 = No; 1 = Yes) | 0.25 | 0.43 | 0 | 1 |

| Distance from home to the Village Committee | Distance from home to the Village Committee (Km) | 3.71 | 5.36 | 0.01 | 30 |

| Distance from home to the logistics point | Distance from home to the logistics point (Km) | 5.38 | 7.34 | 0.01 | 40 |

| Province | Hainan Province = 1; Yunnan Province = 0 | 0.48 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| Unmatched Sample | Matched Sample | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control group | 7 | 807 | 814 |

| Treatment group | 4 | 405 | 409 |

| Total | 11 | 1212 | 1223 |

| Matching Method | Pseudo R2 | LRchi2 | Mean Bias (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before matching | 0.031 | 47.62 | 42.3 |

| Radius matching | 0.001 | 0.57 | 5.3 |

| Kernel matching | 0.000 | 0.50 | 4.9 |

| K-nearest neighbor matching within caliper (k = 4, caliper = 0.01) | 0.002 | 2.10 | 10 |

| Economic Effect | Ecological Effect | |

|---|---|---|

| Radius matching | 1.167 ** (0.495) | 0.038 *** (0.113) |

| Kernel matching | 1.226 ** (0.492) | 0.040 *** (0.111) |

| K-nearest neighbor matching within caliper (k = 4, caliper = 0.01) | 1.170 ** (0.516) | 0.044 *** (0.126) |

| Average | 1.188 | 0.040 |

| Sample Type | PSM | OLS | Selection Bias | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic effect | Full sample | 1.167 ** (0.495) | 1.251 *** (0.418) | 0.074 |

| Ecological effect | 0.038 *** (0.113) | 0.043 *** (0.012) | 0.006 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-Stage | Second-Stage | First-Stage | Second-Stage | |

| Recycling Behavior | Economic Effect | Recycling Behavior | Economic Effect | |

| Whether the village has conducted publicity activities on PPW recycling | 0.189 *** (0.034) | 0.189 *** (0.034) | ||

| Recycling behavior | 0.650 *** (0.243) | 0.143 *** (0.071) | ||

| Constant | 0.190 | 0.668 ** | 0.190 | 0.652 *** |

| Control variable | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| Kleibergen-Paap rk LM | 29.765 *** | 29.765 *** | ||

| Cragg-Donald Wald F | 34.625 *** | 34.625 *** | ||

| Sample size | 1223 | 1223 | ||

| R2/Pseudo R2 | 0.064 | 0.084 | 0.064 | 0.038 |

| Variables | Economic Effect | Ecological Effect | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| PPW recycling behavior | 1.774 *** (0.466) | 0.845 * (0.453) | 0.029 ** (0.013) | 0.029 ** (0.013) |

| PPW recycling behavior × Land fragmentation | −1.937 ** (0.766) | 0.050 ** (0.022) | ||

| PPW recycling behavior × Pesticide expenditure | 1.881 ** (0.814) | 0.063 *** (0.023) | ||

| Control variable | Controlled | |||

| Sample size | 1223 | |||

| R2 | 0.068 | 0.067 | 0.042 | 0.044 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Han, X.; Wang, J. Evaluation of the Effect of Pesticide Packaging Waste Recycling: From Economic and Ecological Perspectives. Sustainability 2026, 18, 390. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010390

Liu J, Wu Y, Li X, Han X, Wang J. Evaluation of the Effect of Pesticide Packaging Waste Recycling: From Economic and Ecological Perspectives. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):390. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010390

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Jiyao, Yanglin Wu, Xiangjun Li, Xiangzhu Han, and Jialin Wang. 2026. "Evaluation of the Effect of Pesticide Packaging Waste Recycling: From Economic and Ecological Perspectives" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 390. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010390

APA StyleLiu, J., Wu, Y., Li, X., Han, X., & Wang, J. (2026). Evaluation of the Effect of Pesticide Packaging Waste Recycling: From Economic and Ecological Perspectives. Sustainability, 18(1), 390. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010390