Abstract

The recent rise of trade protectionism has complicated the relationship between trade and innovation in some countries. This paper evaluates the impact of U.S. export control on the innovation performance of Chinese manufacturing listed firms. Based on firm-level invention patent data from 2015 to 2023, we find that firms subject to export control substantially expand their patent application activities. However, the quantitative expansion coincides with a deterioration in patent quality, as evidenced by the fast-track granted rate. Further analysis suggests that the divergence between firms’ internal innovation preferences, as reflected in management’s innovation awareness, knowledge width and technological trajectory, and their external R&D investment, underlies the innovation quantity–quality tension. Moreover, the decline in innovation quality is primarily concentrated in technological fields not favored by Chinese industrial policy and among state-owned enterprises, suggesting strategic balancing of innovation decisions in response to government intervention. This study provides further insights into the comprehensive impact of trade shock on innovation and contributes to the literature on the potential technological externalities of the U.S.–China trade conflict.

1. Introduction

The recent rise of protectionism has sparked debate over the relationship between trade and innovation in some countries, including China. With the ambitious industrial policies (i.e., “Strategic Emerging Industries 2015” and “Made in China 2025” (“Made in 2025” was initiated in 2015 by Chinese government with the objective of providing guidance and setting targets for industrial development from 2015 to 2025. This industrial policy is widely regarded as a trigger for the China–U.S. trade and technology disputes)) and rapid technological advancement, China have been regarded as a major competitive threat by the United States. And, the Trump and Biden administrations have imposed a series of sanctions on China, including export control. The direct economic effects of sanctions, including on exports, growth and welfare, and long-term sustainability of firms, have been systematically explored [1,2,3]. Against the backdrop of the U.S.–China trade conflict increasingly spreading into technology diffusion and innovation, how the innovation activities and performance of firms in China are affected remains insufficiently investigated.

This paper systematically evaluates whether U.S. export control prompts Chinese manufacturing firms to trade off innovation quantity against innovation quality, and through which organizational decisions and government mechanisms this occurs, addressing gaps in the literature.

The impact of trade friction on innovation is considered a complex, dynamic, and nonlinear process jointly shaped by firm characteristics, market types, and institutional environment [4,5,6]. However, the impact of export control on innovation performance remains uncertain.

On the one hand, technology blockade and disruption to international scientific networks directly sever cross-border knowledge flows and channels for collaborative R&D. As a result, firms are unlikely to identify technological substitutes or substantially enhance their independent innovation capabilities in the short term, which negatively affect both the performance quantity and quality [7,8,9]. On the other hand, trade friction may also enhance management’s perception of innovation opportunities, thereby prompting firms to engage in more proactive innovation activities to ensure survival or to adjust their innovation strategies in response to new market demands [4,10,11].

It is also noteworthy to consider the response of the Chinese government. Traditionally, the Chinese government has intervened in firm’s innovation activities through policy instruments such as subsidies to advance its industrial and innovation strategies and narrow the gap with technologically advanced countries [12,13]. Since the implementation of “Made in China 2025”, China has increasingly pursued technological self-reliance and breakthrough in frontier sectors. Firms subject to export control are highly likely to adjust their innovation directions and strategies in line with industrial or innovation policy guidance, which may lead to divergences in quantity and quality of innovation.

Existing studies provide conflicting evidence on whether trade friction suppresses or stimulates innovation [11,14]. Crucially, little is known about whether increases in innovation activity reflect substantive technological progress or strategic inflation of output, particularly outside high-tech industries. Therefore, we ask: has U.S export control, by restricting technology diffusion, hindered or stimulated Chinese firms’ innovation?

Considering the resilience effect of innovation activities on export control and the guidance of industrial policies, affected firms have strong incentives to increase their patenting activities. Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1.

Export control increases firms’ innovation quantity.

However, compared with innovation quantity, innovation quality plays a more critical role for promoting technological sustainability, enhancing supply-chain resilience, and safeguarding technological sovereignty. High-quality innovation is typically characterized by strong originality, high technological complexity and barriers, and low substitutability. It promotes productivity improvements and industrial upgrading, thereby establishing a sustainable path of technological accumulation. While quantity-driven innovation activities can expand the scale of innovative output in the short term, they do little to enhance an economy’s adaptive capacity or resilience in the face of external shock. Furthermore, allocating scarce R&D resources to low-return and low-quality innovation endeavors may displace strategic innovations that depend on prolonged, intensive research efforts.

Crucially, overlooking innovation quality may exacerbate technological dependency and the misallocation of R&D resources over the long term. Insufficient high-quality innovation may compel firms and countries to rely continuously on external technologies, thereby weakening technological sovereignty and heightening vulnerabilities to geopolitical and supply-chain shock. Accordingly, innovation quality not only affects firm performance and sustainable development but also directly determines whether a country’s innovation system can achieve long-term sustainability, maintain structural resilience, and safeguard technological sovereignty.

Export control severely restricts firms’ ability to access external technologies through supply chains or international technology diffusion networks. It takes time to identify technological substitutes and enhance indigenous innovation capabilities. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2.

Export control decreases firms’ short-term innovation quality.

This paper collects invention patent data for listed manufacturing enterprises in China from 2015 to 2023 from the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) and the China Open Platform databases (CNOPENDATA). By cross-referencing the BIS Entity List with the “TIANYANCHA” equity database, we could identify affected listed Chinese firms as the treatment group. To mitigate potential time- and firm-level confounding effects, we employed a multi-period difference-in-difference model to identify the causal impact.

Our findings indicate that Chinese firms subject to U.S. export control experienced a significant increase in patent applications. However, this growth in quantity was not accompanied by a corresponding improvement in innovation quality, and patent quality in fact declined.

We further address four alternative explanations for the simultaneous surge in patent filings and decline in innovation quality: R&D investment and employees, management’s innovation awareness, knowledge width, and technological trajectory. The mechanism analysis shows that export control reduces management’s innovation awareness and induces firms to reallocate innovation resources and adjust their knowledge search strategies. Although increasing R&D investment can generate more patent applications, export control restricts firms’ access to foreign advanced knowledge and technological components. As a result, affected firms narrow their knowledge width and shift their technological trajectories to exploratory technologies, which ultimately leads to a short-term decline in patent quality.

In addition, taking into account government intervention and guidance in China, we further explore the heterogeneous effects of industrial policy and ownership structure. Our results indicate that, although firms exposed to export control increased patenting activity in both policy-supported and other technological fields, declines in innovation quality were primarily observed in areas not favored by government policy. Moreover, the reduction in innovation quality was mainly concentrated in state-owned enterprises, despite comparable growth in patent quantity.

Our paper makes several contributions to the literature. First, it enriches discussion on the relationship between trade shock (or liberalization) and innovation. Our empirical findings complement and corroborate the conclusions of [11] from a more granular firm-level perspective regarding the complex effects of U.S. export control on innovation in China’s high-tech industries. Specifically, we show that the phenomenon of rising innovation quantity but declining innovation quality is not confined to high-tech sectors or basic research domains. Rather, this dual effect also emerges in the patenting activities of traditional manufacturing firms and other technological fields, indicating that the exogenous shock of export control generates systematic impacts across a much broader range of industries. In addition, we further investigate the pathways and mechanisms through which export control affect firms’ innovation—an aspect not examined in prior studies.

Our findings also enrich the literature on the complex and nonlinear relationship between trade shock and innovation. Existing studies show that the impact of trade shock on firms’ innovation outcomes is far from uniform and is jointly shaped by firm characteristics, market conditions, and institutional environments [14,15,16]. Our evidence further substantiates and extends this view. The observed divergence between patent quantity and patent quality under export control reflects the inherently complex nature of firms’ innovation decisions.

Also, our study further extends core literature on the U.S.–China trade conflict. Amid heightened trade policy uncertainty, tariff escalations not only curtailed firms’ exports but also exerted significant adverse effects on their operating performance and innovation capacity [2,14,17,18]. Unlike tariff shocks, the impacts of export control are more complex—particularly in generating positive incentives for innovation quantity. This difference may stem from the distinct policy objectives of export control versus tariff shock, as well as the varying degrees of industrial policy support in China.

Lastly, this paper is related to research on the surge of patenting activity and R&D policies in China [18,19,20]. Although national industrial or innovation policies, along with local subsidy programs, are generally regarded as effective in stimulating patent applications [21], recent studies suggest that such subsidies may guide firms to prioritize incremental innovation over radical innovation [19]. We further examine the heterogeneity in patent performance depending on whether the patents are supported by industrial policies. Notably, although the increase in patent quantity is widespread, the decline in quality is concentrated in technologies which are not supported by government industrial policies and among state-owned enterprises, which appears to reflect the influence of government policy guidance.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Trade Liberalization (Or Shocks) and Innovation

Schumpeter innovation theory holds that firm’s innovation relies not only on technological breakthroughs but also on market conditions [22,23]. And, trade liberalization (or shock) has been demonstrated to significantly influence firms’ innovation activities [24]. Early studies have typically emphasized the scale and market effects of trade, suggesting that firm’s innovation responses to trade shock may exhibit an inverted U-shaped pattern [16]. Moderate external competition is able to incentivize firms to improve technological efficiency and accelerate new product development in order to expand market share and profit margins [25]. However, heightened trade policy uncertainty (TPU) from sever trade shock has been widely shown to change the investment environment and market expectations of a firm, ultimately negatively affecting their innovation capabilities and performance [14]. Moreover, trade is widely recognized as a key channel for knowledge spillover and technology diffusion [26]. By importing intermediate goods and technologies from foreign markets, firms are able to enhance their technological capabilities [24]. Particularly, some informal institutions stemming from trade amplify the positive innovation externalities of trade liberalization. For example, trade liberalization frequently coincides with the cross-border mobility of high-skilled labor. These migrants transmit substantial “brain gains” to their home countries via ethnic networks and international technology diffusion channels, thus promoting global knowledge dissemination [27,28].

Notably, recent studies emphasize that the impacts of trade on a firm’s innovation are not limited within market size or competitive effects but rather constitute a complex, dynamic, and nonlinear process shaped by firm’s characteristics, market types, and institutional environments [4,5,6].

Sudden trade barriers and supply chain disruptions directly unsettle a firm’s routines, defined as their long-established behavioral patterns and operational processes. Firms may be compelled to seek new suppliers and production sites, adjust production processes, or even withdraw from existing markets [4,29,30]. Moreover, an increase in TPU directly raises firm’s financing costs and operational risk and reduces total factor productivity (TFP) at same time [31]. For breakthrough or high-quality innovations that demand sustained and costly investments, firms often cut back on long-term, high-risk projects to navigate these challenges, ultimately leading to a decline in overall innovative patent activities [31,32,33,34]. Furthermore, technology blockades and the decoupling of scientific collaborations arising from trade barriers disrupt cross-border knowledge flows and collaborative R&D channels [8,35]. These disruptions severely impede the critical “knowledge-design interaction” loop and negatively affect the quantity and quality of innovation [5,7,8,9].

Crucially, when traditional markets shrink due to trade protectionism, the feedback signals that firms receive from the market undergo drastic changes, which would alter management’s awareness of external innovation risks and further prompt them to reallocate resources and adjust knowledge search strategies [36]. Under a high TPU, management tends to shorten their innovation horizons or awareness, prioritize defensive or incremental projects, such as securing alternative suppliers or enhancing process robustness, and reduce engagement in open external collaborations [37]. Nonetheless, evidence suggests that trade shock is able to heighten management’s awareness of innovation opportunities [10]. This often prompts firms to pursue more aggressive innovation strategies to sustain their competitive position or to adjust their innovation efforts in response to emerging market demands [4,11]. For instance, among firms affected by the U.S.–China trade war, those with high R&D intensity experienced relatively smaller declines in market value and TFP [38]. This indicates that R&D investment provides firms with some resilience and strategic flexibilities against trade shocks. Despite facing unfavorable shocks, firms with a solid innovation foundation or R&D investment are more likely to maintain or increase their innovation efforts to achieve higher patent quantity and quality [39]. Moreover, market-leading firms are motivated to leverage trade-induced competitive pressure to intensify R&D efforts and secure higher innovation returns [16].

It is clear and easy to observe and discuss firms’ innovation decisions and performance induced by changes in trade environments through multiple mechanisms, such as TPU, management’s innovation awareness, and knowledge search. But, trade control is not merely a source of technological shock. In the context of the U.S.–China trade war, it also serves as a strategic instrument of state-level balancing, and overlooking the role of governments may result in partial or biased conclusions [15,40,41].

2.2. U.S.–China Trade Conflict and Innovation

Over the past two decades, benefiting from trade liberalization and technology integration with advanced economies, particularly the United States, China has accelerated its innovation efforts and sought to position itself at the global technological frontier [35]. By 2011, China had surpassed the United States to become the world’s leading country in terms of patent applications [42]. Innovation policy and industry policy have been widely shown to exert significant influence on firms’ innovation performance, including both the quantity and quality of patents, as well as their strategic orientation [13,43,44]. In particular, local governments’ patent subsidy programs directly support firms’ patenting activities. While such programs have been shown to generate clear positive effects on both patent quantity and quality in the short term, long-term evidence indicates that although these programs can only sustainably increase patent applications [45]. And, reduction in subsidy funding has led to a proliferation of low-value and low-originality patents [12].

Although this subsidy program has been phased out for various reasons, it is important to recognize that industrial policy remains a critical instrument through which the government formulates innovation catch-up strategies and shapes firms’ technological trajectories [44,46,47]. With its ambitious industrial policies (i.e., “Strategic Emerging Industries 2015” and “Made in China 2025”) and rapid technological advancement, China has been regarded as a major competitive threat by the United States since 2018. Consequently, both the Trump and Biden administrations have implemented a series of economic sanctions against China, centered on tariff barriers and stringent control over critical technologies and cross-border talent mobility [48,49]. As the tariff war constitutes the core of the trade conflict between China and the U.S., recent studies have extensively and systematically documented the adverse externalities of tariff barriers on exports, economic growth and welfare, and firms’ innovation performance [1,2,3,11].

It is noteworthy that recent attention has focused on U.S. export control. By placing firms and individuals at critical nodes on the Entity List and restricting the cross-border flow of key technologies, equipment, and knowledge, export control functionally resembles traditional economic sanctions and coercive diplomacy. It serves both as a tool of economic statecraft to pursue strategic objectives at the state level [15,41] and as a weaponized interdependence that can amplify coercive effects by exploiting asymmetries within global networks [50,51]. Accordingly, it would underestimate institutional-strategic character and systematic impact on technological capabilities if treating export control merely as a “technological shock”. Recent evidence indicates that Chinese firms listed on the Entity List generally face constrained R&D investment, disrupted external collaborations, and narrowed scope of knowledge searches, resulting in significant short-term impacts on both the quantity and quality of innovation performance [19,52]. However, ref. [11] provides evidence that in high-tech industries and basic science sectors, export control generates a complex divergence, characterized by a decline in innovation quality alongside an increase in innovation quantity, while the mechanisms underlying this phenomenon remain unclear.

The main contribution of this study lies in directly examining the actual impact of US export control measures on firms’ innovation performance from both the quality and quantity perspectives. At the same time, it seeks to explain this complex phenomenon at the firm level by drawing on theoretical frameworks such as organizational innovation, evolutionary economics, and the Resource-Based View (RBV), thereby addressing gaps in the existing literature. Moreover, the analytical framework briefly considers the guidance and interventions provided by government industrial and R&D policies.

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Sample Selection and Data Source

We select China’s A-share listed firms in the manufacturing industry from 2015 to 2023 as our research sample to explore the impact of U.S. export control on corporate innovation performance (Since nearly all Chinese listed firms included in the BIS Entity List operate within the manufacturing sector, we restrict our analytical sample to manufacturing companies. And, the classification of a firm’s industry is based on the criteria of the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC)). After excluding ST and PT firms, the final sample consisted of 2891 listed firms, yielding a total of 19,040 firm–year observations.

Export control data are sourced from the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) Entity List (2018–2023), and we manually identified the Chinese firms with their first designation date on the list. Accounting for the internal equity structure, we systematically evaluated whether Chinese firms presented on the BIS list, including their subsidiaries and holding companies, were also list on the Chinese A-share market to establish a rigorous and comprehensive treatment group (For example, the Aviation Industry Corporation of China, Ltd. (AVIC)—added to the BIS Entity List in December 2020—operates as a non-publicly listed parent company but directly oversees 14 A-share listed subsidiaries/holding companies (e.g., stock codes: 000026, 000050, 002013). Consistent with our treatment group definition, these affiliated listed entities are treated as subject to BIS list sanctions).

It is worth noting that firms on the BIS Entity List may inherently possess strategic significance or advanced technological capabilities, which may result in selection bias. To mitigate this bias, we incorporate firm fixed effects to try to control firm-level characteristics, including long-standing technological capabilities, strategic importance, and inherent industry status firstly. And, we further implement a dynamic effects (event-study) model to examine pre-treatment trends, assessing whether these firms exhibited systematically different innovation performance prior to being listed on the BIS List. However, these approaches cannot fully eliminate all forms of selection bias, particularly those arising from unobservable shock.

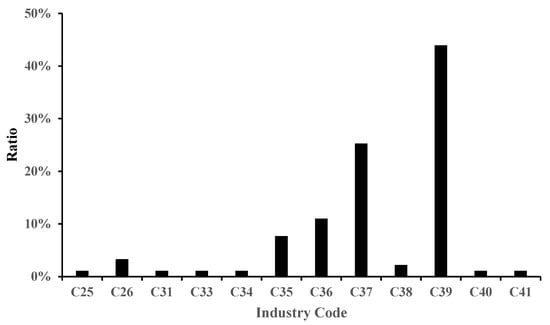

We compiled the industry and size distribution information of firms in the treatment group. As shown in Figure 1, it is evident that firms subject to export control are primarily concentrated in the computer and communication electronics manufacturing (C39), transportation equipment manufacturing (C37, including railway, shipbuilding, and aerospace manufacturing), automobile manufacturing (C36), and specialized equipment manufacturing sectors (C25).

Figure 1.

Industry distribution of treated group.

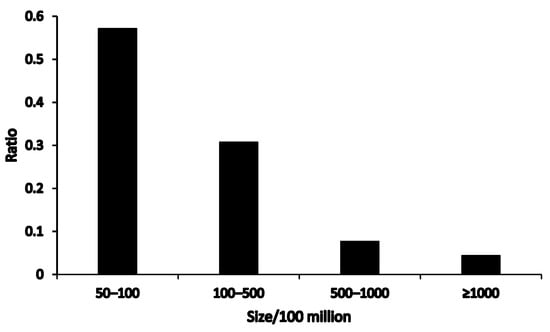

As shown in Figure 2, the assets of firms affected by export control are mainly concentrated below 500 million.

Figure 2.

Size distribution of treated group.

Invention patent data are sourced from the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) and the Chinese Open Data Platform (CnOpenData). For each patent, we could obtain comprehensive details including the application number, application date, grant date, and applicant information. Given that CNIPA imposes a confidentiality period of up to 18 months on newly filed invention patent applications, we collected the patent data as of 30 June 2025. This timing ensures the complete and uninterrupted inclusion of all patent applications during 2015–2023, preserving data integrity for the full analytical period.

Financial data for listed firms were obtained from the China Stock Market & Accounting Research Database (CSMAR) and their corresponding annual reports.

3.2. Model Design

To examine the causal effect of U.S. export control on the innovation performance of Chinese listed firms, we employ a multi-period difference-in-differences (DiD) framework with two-way fixed effects (TWFE). The baseline regression model is specified as:

where captures firm-level innovation performance for listed company in year , operationalized through two key metrics: the annual number of invention patent applications (Application Counts) and the proportion of these inventions granted within the 18-month confidentiality period (Fast-track Granted Ratio). is a dummy variable equal to 1 if company is presented on the BIS List in year , and 0 otherwise. represents a set of control variables which may affect a firm’s innovation performance. In addition, we include a year fixed effect and firm fixed effect to account for unobserved heterogeneity across time and firms. denotes the residual term.

3.3. Variables and Measures

3.3.1. Dependent Variable

The annual number of invention patent applications (Application Counts) is adopted as a quantitative indicator to measure firm innovation performance firstly. In China, patents can be categorized into three types: invention, utility model, and design. Compared with the latter two types, invention patents undergo a more rigorous examination process and entail higher costs (including application and maintenance fees), thus providing clearer property rights, greater innovativeness, and a longer protection period.

However, by providing subsidies or guiding R&D strategies, government industrial and innovation policies significantly influence firms’ patent application activities [53]. As a result, firms pursue patent applications not only to secure technological rights but also to obtain subsidies or strengthen ties with authorities. Merely relying on invention patent application counts to assess innovation performance has been demonstrated to tolerate “inflation bubble” risk, whereby the submission of numerous low-quality patents diminishes overall innovation quality [11].

Hence, to capture the multifaceted nature of innovation performance, it is significant to introduce a quality indicator. Although the number of patent citations reflects the value and impact of patents and is extensively adopted, it often suffers from truncation bias [28,54,55]. Since citations have been accumulated once a patent has been disclosed, a stable citation count often requires considerable time to emerge [56]. To address this issue, studies typically implement truncation adjustments based on historical citation distributions or introduce technology and year fixed effects [57]. However, the former approach often overlooks pronounced heterogeneity in citation patterns across both cross-sectional and temporal dimensions, while the latter may absorb any meaningful variation in innovation across sectors [58]. Ref. [59] conducted a further assessment of these two approaches based on an extended NBER patent database. The results indicate that existing adjustment methods do not work well, and analyses based on citation information with truncation bias may undermine the robustness of some earlier research conclusions. Considering the specific timing of export control and the temporal coverage of the patent dataset in this study (2018–2023), relying on citation data as an indicator of patent quality may also undermine the robustness of the main findings.

To more comprehensively assess innovation performance, the probability of a patent being granted within the statutory 18-month confidentiality period (Fast-track Granted Ratio) is adopted as an early proxy for quality to evaluate firms’ capability to rapidly obtain technological rights. This indictor takes advantages of the particular features of China’s patent review system:

- (1)

- Confidentiality and disclosure process. Upon submission, an invention patent undergoes a statutory confidentiality period of up to 18 months, during which the application is not publicly accessible or usable. Applicants may request early disclosure; otherwise, the patent is automatically disclosed at the end of the period.

- (2)

- Substantive examination process. Once a substantive review is requested by applicants, CNIPA assesses the novelty, inventiveness, and utility of the application. Review typically involves multiple rounds of negotiation and communication with the applicants.

- (3)

- Accelerated review process. The Chinese government has implemented a fast-track examination process for high-quality patents and patents in core industries since 2017. Patent examination offices are required to complete the review of these patents within 6–12 months. Firms can choose whether to apply for the fast-track examination on a voluntary basis.

These suggest that when firms file patent applications to secure exclusive technological rights rather than to obtain subsides or policy incentives, they would tend to request substantive examination as early as possible and apply for the accelerated review track. Obtaining patent authorization before the statutory 18-months disclosure can reduce the risk of imitation by competitors and minimize potential technological disputes. In addition, patents granted during the maximum confidentiality period typically experience fewer administrative review cycles and are likely to possess greater quality. In contrast, patents filed primarily to obtain subsidies or other policy incentives often face longer examination periods and may be withdrawn or rejected.

Notably, while the fast-track granted ratio is designed with consideration of the reforms in China’s national patent system and firms’ incentives and motivations for innovation, it does not exclusively capture technological value or the quality of innovation. In practice, fast-track grants are also influenced by administrative prioritization, especially given that China’s patent examination resources are frequently directed toward strategic emerging industries and critical core technological fields. Simultaneously, strategic adjustments of firms may also influence their willingness to obtain a fast-track patent. For instance, they may do so to gain market advantages, enhance the value of their patent portfolios, or respond to national industrial policies. Therefore, the fast-track granted ratio reflects not only the interplay between institutional design and innovation incentives but also incorporates the combined effects of policy bias and firms’ strategic behavior. And, we interpret it as a short-term and unidimensional indicator of patent quality.

3.3.2. Key Independent Variable

The key independent variable in this study is Export Control, which indicates whether a listed firm is subject to the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) Entity List. As the most commonly employed regulatory instrument to date, the BIS list covers a wide range of entities, including firms, research institutions, governmental bodies, NGOs, and individuals. We collected Chinese manufacturing listed firms included in the BIS List between 2018 and 2023. We include three categories of firms in the treatment group:

- (1)

- regulated listed firms

- (2)

- listed subsidiaries of these regulated firms

- (3)

- listed holding companies of these regulated firms

The remaining manufacturing listed firms constitute the control group.

3.3.3. Mechanism Variable

We use patent application counts per one million RMB of R&D expenditure (R&D Efficiency) and the share of R&D personnel in total employment (R&D Person) as mechanism variables to explain the change in innovation performance from the perspective of supply.

The Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) was originally used to measure industry concentration. And, ref. [60] first applied it to measure a patent’s originality or generality, and further extended its use to measure knowledge breadth and width, typically calculated as or directly as HHI based on technological classification information. It has since been widely adopted in subsequent studies [61,62,63]. Specifically, when a firm’s patent portfolio is confined to a single technological field, the HHI reaches 1, reflecting an extremely high level of knowledge breadth. Conversely, a lower HHI reflects greater dispersion of patents across technological categories, corresponding to higher knowledge width.

Following [63], we construct the knowledge width based on subclass International Patent Classification (IPC) information, calculated using the following formula:

denotes the number of patent applications by firm in year under main group and is the total number of patent applications by firm in year under all main groups. A greater value of implies more diverse technologies and potentially higher innovation quality of the firm.

The Attention-Based View (ABV) conceptualizes organization as an attention-allocation system. In the context of policy shock, technological constraint, and market uncertainty, the allocation of managements’ attention would significantly influence organizational strategies and behavior [64]. Therefore, inclusion on the BIS Entity List may redirect the top management team’s allocation, thereby affecting innovation choices and organizational responses. Following [65], managerial innovation awareness is measured as the share of innovation-related terms in the MD&A sections of annual reports. To minimize potential data noise, MD&A texts were preprocessed following standard text-cleaning procedures, such as tokenization and stop-word removal, and the selection of innovation-related terms was based on [65].

Definitions and measurement of variables are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definitions of the variables.

3.3.4. Control Variable

Based on established empirical practice, we control for firm size (Size), financial leverage (Lev), cash flow ratio (Cashflow), return on total assets (Roa), number of employees (Employee), duality of CEO and board chair (Dual), ownership concentration (HHI_10), listing age (Listage), firm age (Firmage), current assets ratio (Cr), and net profit growth rate (ProfitGrowth) to account for firm characteristics and governance structures that may independently influence innovation outcomes.

Table 2 reports the descriptive statistics of the main variables. It can be observed that the variables exhibit considerable variation, and all values fall within reasonable ranges.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of variables.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Baseline Regressions

4.1.1. Baseline Regression Results

Table 3 presents the regression results examining the impact of U.S. export control on firm innovation performance. Columns (1) and (2) show that firms listed on the BIS Entity List substantially increase their invention patent application counts. In the full specification with control (Column 2), the coefficient of 0.2466 implies these firms increase their application counts by approximately 28%, statistically significant at the 1% level.

Table 3.

The effect of export control on corporate innovation performance.

However, the results for innovation quality, measured by the fast-track granted ratio in Columns (3) and (4), reveal a significantly negative effect. The estimated coefficients and indicate a reduction of around 3.63–3.87% in the likelihood that patent applications receive accelerated examination, suggesting a deterioration in patent quality or priority.

4.1.2. Economic and Strategic Significance

Export control leads Chinese firms to increase patent applications by approximately 28%, while short-term quality indicators decline by about 3–4%. Given that the average fast-track granted rate across all firms is around 9%, a reduction of 3–4% constitutes a nontrivial change but a noticeable deterioration in short-term innovation quality. This complex pattern may stem from firms’ efforts to balance geopolitical pressure with short-term innovation strategies. Notably, even under these circumstances, this decline may not be interpreted as a systematic deterioration in innovation quality. And, the fundamental decline in technological capabilities requires longer-term observation.

In summary, these findings reveal a clear divergence between innovation quantity and quality: export control pressures induce firms to file more patent applications, but the overall grant priority or technological quality declines. This phenomenon may support a pattern whereby, under heightened external constraints, firms tend to pivot toward quantity-driven rather than quality-drive innovation strategies.

4.2. Robustness Checks

4.2.1. Pre-Trend Test

A crucial prerequisite for the difference-in-difference (DiD) model is parallel trends assumption. To verify this assumption and capture dynamic effects, we adopt an event-study model, taking the year prior to a firm’s first inclusion on the BIS Entity List as the baseline period and incorporating interactions between time dummies and treatment indicator. By tracking the time-varying coefficients of interaction terms, we capture the dynamic impact of export control on Chinese firms’ innovation performance. The specific model is presented as the following formula:

The event-study specification retains the core settings of the baseline model while introducing a set of year-relative time dummies to capture dynamic treatment effects. Here, k indexes the temporal distance (in years) from the firm-specific treatment event; that is, the year when firm i was first added to the BIS Entity List. The dummy variable takes the value of 1 if observation t corresponds to year k before or after the firm’s initial BIS listing (e.g., k = 0 represents the event year itself, k = −1 denotes one year prior to listing, k = 1 indicates one year post-listing, and so on), and 0 otherwise. By interacting these relative-time dummies with the treatment status (implicitly captured through firm-level exposure to the BIS list), the model traces how the innovation outcomes of treated firms evolve in the years surrounding the treatment event while providing an intuitive test of the parallel trend assumptions.

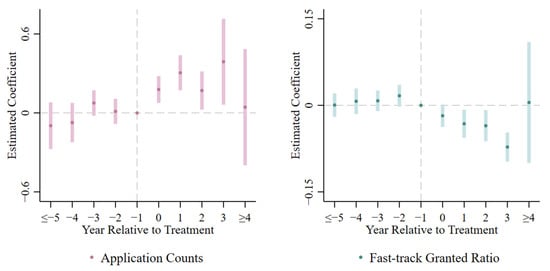

The estimation results of pre-trend test are shown in Figure 3 (In Figure 3, the coefficients represent the estimates of in Formula (3)), with the upper and lower bars representing the 95% confidence interval. Prior to the imposition of export control, the estimated coefficients of the key explanatory variables are not statistically significant and close to 0, indicating no significant differences in innovation quantity and quality between the treatment and control groups, confirming the validity of the parallel trend assumption.

Figure 3.

Pre-trend test results.

Moreover, as shown in the left panel, the interaction terms are significantly positive from the event year through the following three years when patent Application Counts are the dependent variable, indicating that export control boosts innovation quantity. Conversely, as shown in the right panel, when Fast-track Granted Ratio is the dependent variable, the interaction terms are significantly negative following the imposition of export control, suggesting a persistent reduction in innovation quality over the subsequent three years.

4.2.2. Placebo Test

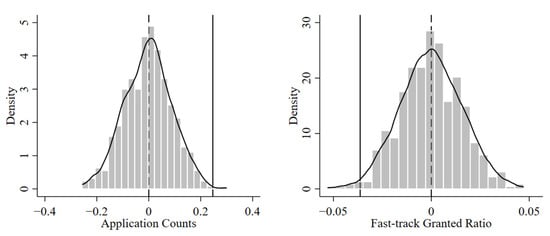

Although the baseline models control various firm characteristics beyond export control, the unobserved firm–year factor may still affect the estimate results. Therefore, we assign randomly treated firms and treatment times at the same time to conduct placebo tests. For each simulation, we randomly select a group of firms equal in size to the actual treatment group to serve as a placebo treatment group and randomly assign treatment timing. We subsequently estimate the placebo treatment effects using the baseline model, record the resulting coefficients, and generate a distribution of placebo effects based on 500 simulations.

The results are shown in Figure 4, with the horizontal axis presenting estimated coefficients of key explanatory variables and the vertical axis presenting kernel density. After 500 random simulation regressions, the distribution of key explanatory variable coefficients approximates a normal distribution centered at 0 and clearly distinct from the estimates obtained in the baseline regressions, indicating that the estimates in the baseline model are unlikely to be driven by unobserved firm–year level factors.

Figure 4.

Placebo test results.

4.2.3. Heterogeneous Treatment Test

Since treatment effects may be heterogeneous across both group and year dimensions, even under the parallel trends, estimates of the treatment effects may still be biased. To address potential heterogeneous treatment effects and examine the robustness of our baseline regression results, we have employed two complementary estimators: (1) Goodman–Bacon decomposition [66]; (2) Sun and Abraham estimation [67].

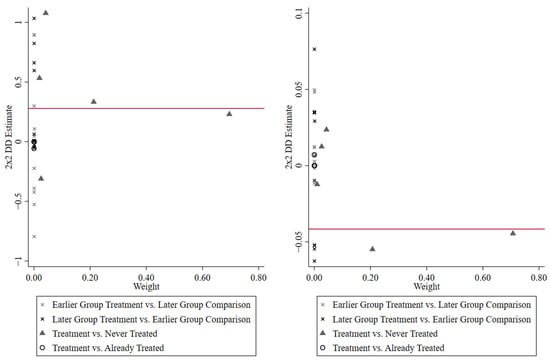

The estimation results of the Goodman–Bacon decomposition are presented in Figure 5 and Table 4. According to the decomposition, in the baseline regression with Application Counts as the dependent variable, the “Later Treatment vs. Early Control” component yields an estimated effect of 0.149, with a weight of only 0.2%. Similarly, in the baseline regression with Fast-track Granted Ratio as the dependent variable, the “Later Treatment vs. Early Control” component produces an estimated effect of −0.002, also with a weight of only 0.2%. These results indicate that the baseline regression estimates are robust.

Figure 5.

Goodman-Bacon decomposition test results.

Table 4.

Robustness check: Goodman-Bacon decomposition test.

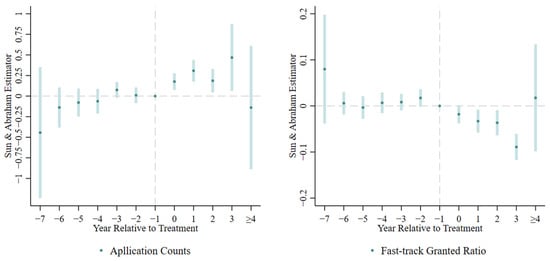

The estimation results of the Sun and Abraham estimation are presented in Figure 6 and Table 5. The results indicate that the dynamic effects remain consistent with the pre-treatment trends after mitigating heterogeneity of treatment effects.

Figure 6.

Dynamic effects: Sun and Abraham estimation.

Table 5.

Robustness check: Sun and Abraham estimation.

Moreover, the coefficients of the main explanatory variables remain stable and statistically significant at the 10% and 5% levels. These results indicate that the baseline regression estimates are robust.

4.2.4. Restricting Sample

Since President Joe Biden took office in 2021, the U.S. has introduced a series of adjustments to its trade and technology policies toward China [68]. Meanwhile, the Chinese government initiated a new Five-Year Plan, which redirected industrial policy towards green, low-carbon development and digital economic transformation. These factors may interfere with our core findings. To address this concern, we restrict the empirical sample by excluding observations after 2021.

As shown in Table 6, after considering the impact of the instability of Chinese industrial policies and the volatility of the U.S. political environment, export control still significantly prompts related firms to increase their patent application counts by approximately 24.02% while reducing the fast-track granted ratio by roughly 2.63%. The main findings of baseline remain robust.

Table 6.

Robustness check: restricting sample.

4.2.5. Using Balanced Panel

Firm entry and exit during the sample period may generate an unbalanced panel, which may induce endogeneity issues arising from missing observations and potentially compromise the validity and robustness of regression estimates. Therefore, firms lacking incomplete time series are removed to construct a balanced panel.

As shown in Table 7, after considering the potential endogeneity issue arising from the unbalanced panel, export control still significantly prompts related firms to increase their patent application counts by approximately 24.45% while reducing the fast-track granted ratio by roughly 3.74%. The main findings of the baseline remain robust.

Table 7.

Robustness check: using balanced panel.

4.2.6. Replacing Key Variables

Considering the potential bias arising from nonlinear relationships between the dependent variable and covariates [69,70], taking the logarithm of count variables (such as patent counts) after adding one may lead to biased estimates or even incorrect sign of the coefficient. Therefore, we replace Application Counts with its original value (without logarithmic transformation) and conduct OLS and Poisson regressions.

As shown in Columns (1) and (2) of Table 8, export control significantly promotes related firms to increase their invention patent application by an average of 131.2565 or approximately 40.16%. These suggests estimating the model using the logarithm of application counts plus one as the dependent variable within an OLS framework does not produce biased estimates or incorrect coefficient signs. The results demonstrate the robustness of the main conclusions of innovation quantity.

Table 8.

Robustness check: replacing key variables.

Moreover, we the adopt cumulative granted rate and the number of granted patents as alternative measures to mitigate potential intertemporal effects arising from the distribution of patent grant dates. The result in Column (3) shows that export control significantly reduces the cumulative granted ratio by approximately 8.04%, even slightly larger than the decline in the fast-track granted ratio. This suggests the adverse impact of export control on innovation quality may gradually intensify over time. The result in Column (4) shows that export control leads to a significant reduction in the probability of obtaining patent rights of about 17.96%. That suggests a potential quality deterioration. In summary, the main findings of the baseline remain robust.

4.2.7. Mitigating Anticipation or Selection Effect

While the multi-period DID model differentiates the timing of firms’ inclusion in the BIS List, it fails to capture risk anticipation and spillover effects across comparable firms.

Even if some firms have not yet been formally included on the BIS list, they may still be unable to access advanced intermediate technologies or products from the U.S. in practice. For instance, between 2018 and 2020, a large number of Chinese defense-related firms were successively added to the BIS list. However, export restrictions on military-related products or technologies were already fully implemented in 2018, implying that these firms may have been affected by export control in advance. Accordingly, we initially assign 2018, the onset year of the U.S.–China trade conflict, as the effective treatment year for all firms in the treatment group.

As shown in Columns (1) and (2) of Table 9, after resetting the treatment year, export control still leads to an approximate 21.82% increase in patent applications by the affected firms while simultaneously reducing the fast-track grant rate by 1.39%. These results indicate that the main findings of the baseline remain robust.

Table 9.

Robustness check: anticipation or selection effect.

Moreover, standard DID models may treat units which are about to be treated or already affected by anticipation effects as part of the control group, thereby overlooking potential anticipation or selection effects. Following [71], we implement a staggered DID estimation on the baseline regression model.

As shown in Columns (3) and (4) of Table 9, after constructing a cleaner control group, export control still leads to an approximate 28.33% increase in patent applications by the affected firms while simultaneously reducing the fast-track grant rate by 2.73%. These results indicate that the main findings of the baseline remain robust.

4.2.8. Mitigating Selection Bias

Considering that export control may generate simultaneous shock at the industry level, firms within the same industry may simultaneously experience technology restrictions and supply contractions. For instance, the U.S. has implemented broad export restrictions targeting high-end computing chips and lithography equipment within China’s semiconductor sector. In addition, firms in technology-intensive industries may have exhibited accelerated innovation trends even before being assigned to the treatment group. Although firm-level fixed effects and pre-treatment trend tests have been incorporated, to further mitigate potential common shock and heterogeneous trend at the industry level across different years, we additionally include industry-by-year fixed effects in the baseline.

As shown in Columns (1) and (2) of Table 10, after including industry-by-year fixed effects to mitigate selection bias, export control still leads relevant firms to increase patent applications by 31.69% while simultaneously reducing the fast-track granted ratio by approximately 2.78%. These results indicate that the main findings of the baseline remain robust.

Table 10.

Robustness check: adding industry × year fixed effect.

4.3. Mechanism Analysis

The surge in patent filings accompanied by a decline in quality suggests the presence of multiple underlying mechanisms.

As a dynamic evolutionary process, the development of a firm’s innovation capability and performance are typically influenced by its external environment, internal capabilities, and historical trajectory [4]. R&D investment has been shown to serve as a significant mechanism for coping with external environmental pressure [38]. When traditional markets shrink as a result of trade protectionism, the feedback signals that firms receive from the market undergo profound disruption, which may compel them to undertake more aggressive innovation activities or shift their innovation trajectory in order to sustain their survival [4,10]. High R&D investment enables firms to integrate existing technological resources and internal management capabilities more effectively. This enhances resilience and potential growth in patent activities and technological accumulation, offsetting the adverse effects of trade conflict [38]. In addition, some firms treat R&D investment as a defensive or adaptive strategy to buffer policy shocks and achieve post-shock leading market position and superior performance [72,73].

Therefore, we comprehensively capture the role of R&D investment from both capital and labor aspects as mediators to explore potential mechanisms. R&D Efficiency is measured by invention patent application counts pre one million yuan of R&D investment, and R&D Person is the proportion of R&D staff in total employees. The results in Columns (1) and (2) of Table 11 show that export control significantly enhances R&D Efficiency and R&D Person. This suggests that, although export control increases the uncertainty of R&D activities and limits firms’ effective use of global innovation resources, it encourages firms to intensify innovation efforts and file more invention patents. These efforts help offset efficiency losses caused by limited absorption of external technologies and hindered commercialization of innovation outcomes, which result from constraints in international technology networks [74].

Table 11.

Mediating effect: R&D investment perspective.

Although R&D investment is able to partially account for the positive effect of export control on innovation performance, it seems insufficient to explain the observed decline in the fast-track granted ratio. According to the Resource-Based View (RBV), the innovation capability and performance of a firm not only depend on R&D situations but also on technological knowledge and its management view [75]. As a constraint arising from changes in the external institutional environment, export control may prompt firms to adjust their strategies and behavior to maintain legitimacy and enhance social recognition, including the management and utilization of technological knowledge.

Specifically, we measure Management’s Innovation Awareness based on the ratio of innovation-related terms in a board report to assess the effect of export control on firms’ innovation strategy preferences [76]. The results in Column (1) of Table 12 indicate that firms exposed to export control exhibit lower Management’s Innovation Awareness. However, this conclusion appears to be at odds with the observed increase in external R&D investment, suggesting that more complex mechanisms may be involved.

Table 12.

Mediating effect: knowledge management perspective and knowledge width.

Accordingly, we incorporate changes in technological knowledge and shifts in technological trajectories as additional mechanisms to enrich our analysis. Prior studies have extensively documented that export control can directly disrupt supply chains and international knowledge diffusion channels, thereby constraining firms’ ability to obtain technological substitutes and enhance autonomous R&D capabilities in the short term [77,78,79]. We primarily interpret the impact of export control on firms’ innovation direction through two channels: ① knowledge width; ② shift in technological trajectories.

High-quality or radical innovation typically involves a broader search that extends beyond a firm’s existing knowledge base [63]. That suggests broader knowledge width is associated with higher innovation quality or greater fast-track granted ratio. The results in Column (2) of Table 10 show that export control significantly narrow firms’ knowledge width, leading them to explore within a smaller set of technological domains, which are often associated with a slowdown in technological expansion and a decline in innovation quality [63].

Moreover, we conceptualize technological trajectory shift as firms’ trade-off between exploratory and exploitative technologies. Specifically, we classify patents in IPC fields that a firm had already entered within the five years prior to export control as exploratory technologies. And, patents in IPC fields newly entered after export control are defined as exploitative technologies.

The analysis results in Table 13 show the positive effects of export control on innovation quantity and the negative effects on innovation quality arising in both exploratory and exploitative technologies. However, relative to exploitative technologies, firms affected by export control file disproportionately more patents in exploratory domains, and these patents exhibit a lower fast-track granted ratio. This suggests that although firms subject to export control attempt to file more patents in exploratory technological domains, their limited knowledge stock and lack of prior experience in these areas ultimately result in lower patent quality [80,81].

Table 13.

Mediating effect: technological trajectory shift.

Overall, the trade protectionist signals and heightened trade policy uncertainty (TPU) generated by export control have weaken management’s innovation awareness and prompted them to reallocate innovation resources and adjusted knowledge-search strategies. In response, firms tend to raise their R&D intensity to enhance organizational flexibility and buffering capacity, thereby maintaining their competitive position in the short run. This contributes to an overall increase in the patent application counts. However, they are unable to quickly obtain technological substitutes or enhance their internal innovation capabilities in response to supply-chain disruptions and the breakdown of international knowledge-diffusion networks due to export control. As a result, although these firms narrow their technological exploration domains and file relatively more patents in exploratory technologies, the quality of these patents declines markedly, ultimately leading to a short-term deterioration in overall patent quality.

4.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

In the previous section, we found that export control simultaneously increases firms’ R&D investment while reducing managerial innovation awareness and knowledge width. This phenomenon may reflect firms’ strategic deviations arising from pursuing government industrial or innovation policies that are not fully aligned with their existing technological domains. Especially in China, industrial policies often serve as a compass for firms’ technological innovation. When formulating R&D investments, selecting technological trajectories, and making innovation strategies, firms typically consider the guidance provided by industrial policies to mitigate R&D risks, enhance resource allocation efficiency, and seize potential opportunities arising from policy support [13].

Therefore, we further explore the heterogeneous effects of industrial policy and firm ownership type.

4.4.1. Technology Heterogeneity Under Industrial Policy Guidance

Given that the 14th Five-Year plan emphasizes industrial policies focused on the digital economy transformation in China, we identify patents related to digital economy manufacturing within patent portfolios of listed firms based on the “Reference Table of Digital Economy Core Industries and International Patent Classifications (2023)” issued by the CNIPA (The relevant document can be accessed at: https://www.cnipa.gov.cn/art/2023/3/24/art_88_183113.html, accessed on 30 June 2025). By distinguishing between digital economy manufacturing patents and non-digital economy manufacturing patents, we explore how changes in industrial policy moderate firms’ innovation performance under export control.

As shown in Table 14, although firms exposed to export control exhibit more active patenting in both government-supported and other technological fields, the decline in innovation quality is concentrated in areas not favored by government policy. This further suggests that the complex effects of export control on innovation performance may stem from the orientation of government industrial and innovation policies. Although the guidance of industry policy has been shown to be effective, it does not alleviate the decline in innovation quality among firms affected by export control. Industry policy that overemphasizes specific technological fields and quantity of innovation may induce firms to venture into areas beyond their existing expertise and decrease innovation quality. This may further limit the effectiveness of such policy in enhancing firms’ sustainable innovation capabilities.

Table 14.

Heterogeneous effects of industrial policy.

4.4.2. Ownership Type

Compared with private enterprises, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) typically place greater emphasis on achieving government political objectives, including industrial and innovation policies, rather than profit maximization in China. Since their goals are often set by officials, managements in SOEs have limited power to adjust corporate innovation strategies and are thus less able to leverage policy flexibility to achieve productive objectives. Consequently, export control may have heterogeneous effects on the innovation performance of SOEs and private enterprises. Therefore, we further explore whether the impact of export control on firms’ innovation performance is moderated by the ownership type.

The regression results reported in Table 15 show that, for both SOEs and private enterprises, designation on the Entity List significantly increases invention patent application counts. However, export control reduces the fast-track grant ratio only for SOEs, with no significant effect on private enterprises. This finding indicates that, under external regulatory pressure, state-owned enterprises—due to their obligation to fulfill political objectives—are subject to greater institutional constraints on innovation strategies, which limits the generation of rapid innovation outcomes. In contrast, private firms enjoy greater strategic flexibility and are able to comparatively maintain innovation efficiency.

Table 15.

Heterogeneous effects of ownership type.

5. Conclusions and Discussion

Drawing on U.S. BIS Entity List data and invention patent information of Chinese listed manufacturing firms, this paper systematically explores the impacts of U.S. export control on firms’ innovation performance. The results indicate that while export control substantially stimulate patent application counts, the surge in quantity does not correspond to enhancement in their actual technological capabilities, indicating a short-term decline in innovation quality.

The mechanism analysis indicates that export control prompts these firms to reallocate innovation resources and adjust their knowledge-search strategies. Although increasing R&D investment is shown to increase patent application counts, export control hinders firms’ access to advanced foreign knowledge and technological components as readily as before. Consequently, these firms choose to narrow their knowledge width and redirect their technological trajectories, ultimately leading to a short-term decline in patent quality.

It is worth noting that this complex phenomenon may also stem from adjustments in firms’ long-term innovation strategies and the influence by political factors. Specifically, Chinese firms may leverage patent activities to signal their innovative efforts to regulators or policymakers, thereby gaining strategic advantages in the policy. Even in the absence of actual improvements in technological capabilities, firms may gain greater innovation externality by increasing strategic patent filings. In addition, the surge in patenting activity may also stem from defensive innovation strategies. Firms may file patents rapidly even when the relevant technologies are not fully developed in order to avoid litigation and mitigate potential competitive threats.

The empirical findings of this study enrich and corroborate [11] by providing more micro-level evidence of the complex impacts of U.S. export control on Chinese firms’ innovation. Specifically, we observe that the “increase in innovation quantity accompanied by a decline in quality” is not confined to high-tech sectors or basic research areas. It also occurs in traditional manufacturing firms and other technological fields. This indicates that the exogenous shock of export control exerts systematic effects across a wider range of industries.

In addition, the findings of this study also contribute to the literature on the complex and non-linear relationship between trade shock and innovation performance or capability [4,5,6]. Previous studies have shown that the impact of trade shock on firm innovation is unstable and contingent upon a combination of firm characteristics, market types, and institutional environments [37,82,83]. Our evidence further validates and extends this view. The divergence in patent quantity and quality induced by export control arises from firms’ complex innovation decisions. Although high R&D investment provides substantial flexibility and buffering capacity, enabling firms to maintain technological market leadership and quickly recover from export control shock to achieve higher innovation output, our evidence indicates that external institutional pressure compels firms to balance the exploration of new knowledge with the exploitation of existing knowledge [84]. It is almost impossible to find equal technological substitutes and enhance autonomous R&D capabilities in the short term due to the abrupt disruption of supply chains and international knowledge acquisition channels [77,78,85]. This leads to a contraction of firms’ knowledge width and a shift in their technological trajectories, ultimately resulting in the decline in short-term innovation quality.

Furthermore, our findings contribute to the literature on the U.S.–China trade dispute. Prior studies have primarily focused on the negative effects of the import tariff war on firms’ innovation performance [11,86]. Our study indicates that export control would increase firms’ patent output. This effect may reflect differences in the underlying targets of export control versus import tariff shock, as well as variations in the support provided by China’s industrial policies. Tariff shock predominantly imposes substantial output losses and reductions in TFP on labor-intensive, capital-intensive, and resource-intensive firms, leading them to curtail high-risk R&D investment and patenting activities [14]. Given the geopolitical objectives and the substantive nature of technological sanctions inherent in U.S. export control, the affected firms are primarily concentrated in technology-intensive sectors [10,87], which generally possess stronger innovation capabilities and higher innovation demands. And, the role of the Chinese government cannot be overlooked. Chinese industrial policies are strategically directed toward technology sectors and technological domains aimed at catching up with and surpassing the U.S. [88,89].

This study provides important implications for firms facing trade and technological restrictions. It is significant to balance both quantity and quality objectives when making innovation decisions. An excessive focus on quantity may undermine innovation quality and offer limited contribution to sustainable technological capabilities. Even if heightened geopolitical tensions prompt the government to prioritize innovation quantity over quality in its incentive policies, management should carefully consider investment timing and strategic allocation when redirecting innovation efforts or pursuing breakthroughs, rather than focusing solely on quantitative targets. Firms should avoid excessively filing exploratory patents without sufficient absorptive capacity and should balance short-term signaling with long-term knowledge accumulation.

Moreover, the findings offer valuable insights for developing countries confronted with trade and technological competition. For instance, in China, previous patent subsidy policies often incentivized firms to prioritize innovation quantity to secure additional support. In an international environment characterized by technological catch-up and heightened geopolitical tensions, policymakers should pay adequate attention to overemphasis on the quantity of innovation and the sustainability of innovation quality. Even under external pressure such as export control, China and other regions should align innovation and industrial policies and incentive mechanisms with national development goals and local conditions. In fact, excessive innovation quantity at the expense of quality could threaten technological sustainability, and overly narrow knowledge search may increase systemic fragility in decoupled environments. Especially in the context of ongoing U.S.–China technological decoupling, focusing on quantity over quality is unlikely to support China’s technology catch-up goals or the sustainable development of firm-level technological capabilities. Ultimately, building a robust and sustainable innovation ecosystem is critical.

This study also has several limitations. First, due to data constraints, we were unable to accurately capture the true perceptions or decisions of firm managements regarding export control. Future research could address this by employing questionnaire survey or texted-based analysis to obtain comprehensive indicators of management innovation decisions, thereby better explaining the complex effects of export control on innovation. Second, the measurement of innovation quality is not fully comprehensive. Due to the limited observation window, we only used patent fast-track granted rate as a short-term indicator of innovation quality. Future studies could incorporate stabilized citation data and patent rights information to provide a more complete assessment of innovation quality. Third, this study considered only a single industrial policy as the analytical basis. Subsequent studies could examine multiple relevant industrial policies to achieve a broader understanding of government intervention.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by S.Z. and M.T. The first draft of the manuscript was written by S.Z. and F.C., and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 72403098), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (No. 2023A1515110384), and the Foundation of Chongqing Engineering Research Center for Intelligent Applications of Financial Big Data (No. 2025KFKT-005).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available from the https://data.csmar.com (CSMAR database, accessed on 30 June 2025), https://www.cnopendata.com (CNOPENDATA database, accessed on 30 June 2025) and http://epub.cnipa.gov.cn/ (CNIPA database, accessed on 30 June 2025), which are accessible to registered users.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jiangtao (Allen) Qiu and Yun Xu for their invaluable guidance and comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Fajgelbaum, P.D.; Goldberg, P.K.; Kennedy, P.J.; Khandelwal, A.K. The return to protectionism. Q. J. Econ. 2020, 135, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorbecke, W.; Chen, C.; Salike, N. China’s exports in a protectionist world. J. Asian Econ. 2021, 77, 101404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benguria, F.; Choi, J.; Swenson, D.L.; Xu, M.J. Anxiety or pain? The impact of tariffs and uncertainty on Chinese firms in the trade war. J. Int. Econ. 2022, 137, 103608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R.R.; Winter, S.G. An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, S.J.; Rosenberg, N. An overview of innovation. In The Positive Sum Strategy: Harnessing Technology for Economic Growth; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1986; Volume 14. [Google Scholar]

- Melitz, M.J.; Redding, S.J. Trade and Innovation; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cerdeiro, D.A.; Komaromi, A. Trade and income in the long run: Are there really gains, and are they widely shared? Rev. Int. Econ. 2021, 29, 703–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Jiang, W.; Mei, D. Mapping Us-China technology decoupling: Policies, innovation, and firm performance. Manag. Sci. 2024, 70, 8386–8413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Gao, Y.; Cheng, X.; Wang, Q. The impact of the US export controls on Chinese firms’ innovation: Evidence from Chinese high-tech firms. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 95, 103510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Hou, F. Trade policy uncertainty and corporate innovation evidence from Chinese listed firms in new energy vehicle industry. Energy Econ. 2021, 97, 105217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Ma, X.; Xie, M.; Zhong, N. Innovation’s false spring: US export controls and Chinese patent quality. J. Int. Money Financ. 2025, 150, 103229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, J.; Motohashi, K. Patent statistics: A good indicator for innovation in China? Patent subsidy program impacts on patent quality. China Econ. Rev. 2015, 35, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Meng, Q.; Sun, Y.; Wan, Q. How does industrial policy experimentation influence innovation performance? A case of Made in China 2025. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Liu, C.; Narayan, P.K.; Sharma, S.S. The US–China trade war and corporate innovation: Evidence from China. Financ. Manag. 2024, 53, 501–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drezner, D.W. The Sanctions Paradox: Economic Statecraft and International Relations; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Aghion, P.; Bloom, N.; Blundell, R.; Griffith, R.; Howitt, P. Competition and innovation: An inverted-U relationship. Q. J. Econ. 2005, 120, 701–728. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Tian, Z.; Wang, X. The impacts of the US trade war on Chinese exporters. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2024, 106, 1576–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, A.G.; Jefferson, G.H. A great wall of patents: What is behind China’s recent patent explosion? J. Dev. Econ. 2009, 90, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; de Nicola, F.; Mattoo, A.; Timmis, J. Technological Decoupling? The Impact on Innovation of US Restrictions on Chinese Firms; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, L.H.; Lerner, J.; Wu, C. Intellectual property rights protection, ownership, and innovation: Evidence from China. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2017, 30, 2446–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Behind the recent surge of Chinese patenting: An institutional view. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J.A. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy; Harper & Brothers Press: New York, NY, USA, 1942. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, P.; Steinwender, C. The impact of trade liberalization on firm productivity and innovation. Innov. Policy Econ. 2019, 19, 39–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelli, F.; Moxnes, A.; Ulltveit-Moe, K.H. Better, faster, stronger: Global innovation and trade liberalization. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2022, 104, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, N.; Draca, M.; Van Reenen, J. Trade induced technical change? The impact of Chinese imports on innovation, IT and productivity. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2016, 83, 87–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, G.M.; Helpman, E. Trade, knowledge spillovers, and growth. Eur. Econ. Rev. 1991, 35, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, W. International technology diffusion. J. Econ. Lit. 2004, 42, 752–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxenian, A.L. The New Argonauts: Regional Advantage in a Global Economy; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, H. Propagation of international supply-chain disruptions between firms in a country. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Ji, Y. Trade policy uncertainty, innovation and total factor productivity. Sustainability 2021, 14, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Shen, H.; Tang, X.; Wu, Z.; Ma, S. Trade policy uncertainty and firm risk taking. Econ. Anal. Policy 2021, 70, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.T.; Jung, S.M. Overcoming Financial Constraints on Firm Innovation: The Role of R&D Human Capital. Int. J. Financ. Stud. 2024, 12, 109. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, W.; Yang, J.; Xiao, Y. Trade policy uncertainty and corporate innovation—Evidence from the US-China trade war. Pac. Basin Financ. J. 2025, 89, 102590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Freeman, R.B. Bigger than you thought: China’s contribution to scientific publications and its impact on the global economy. China World Econ. 2019, 27, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drechsler, W.; Natter, M. Understanding a firm’s openness decisions in innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghion, P.; Bergeaud, A.; Lequien, M.; Melitz, M.J. The Impact of Exports on Innovation: Theory and Evidence; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.A.; Xie, H.; Zheng, X. Are R&D-intensive firms more resilient to trade shocks? Evidence from the US–China trade war. J. Int. Money Financ. 2024, 149, 103208. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, C.; Liu, M. Protect or compete? Evidence of firms’ innovation from import penetration. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2023, 16, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drezner, D.W. Bargaining, enforcement, and multilateral sanctions: When is cooperation counterproductive? Int. Organ. 2000, 54, 73–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner-Burton, E.M. Trading human rights: How preferential trade agreements influence government repression. Int. Organ. 2005, 59, 593–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, A.G.Z.; Zhang, P.; Zhao, L. China as number one? Evidence from China’s most recent patenting surge. J. Dev. Econ. 2017, 124, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Lin, J.; Wu, H.M. Investigating the real effect of China’s patent surge: New evidence from firm-level patent quality data. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2022, 204, 422–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Branstetter, L.G. Does “Made in China 2025” work for China? Evidence from Chinese listed firms. Res. Policy 2024, 53, 105009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Wu, H.M.; Wu, H. Could government lead the way? Evaluation of China’s patent subsidy policy on patent quality. China Econ. Rev. 2021, 69, 101663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Yin, J.; Huang, X. Effect of the Strategic Emerging Industry Support Program on Corporate Innovation among Listed Companies in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wang, X.; Zhou, D. Research on the impact of industrial policy on the innovation behavior of strategic emerging industries. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Freeman, R.B. Creating and Connecting US and China Science: Chinese Diaspora and Returnee Researchers; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]