Abstract

Assembly lines are critical to modern manufacturing, facilitating efficient and consistent large-scale production. Nonetheless, traditional assembly lines struggle with challenges such as downtime, operational inefficiencies, and quality control. Integrating artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) offers transformative solutions to these longstanding issues, enhancing not only productivity and quality but also sustainability across various sectors. This study provides a comprehensive review of recent advancements in the application of AI and ML to assembly line operations. It categorizes the existing literature and analyzes the various models and algorithms used to optimize operational efficiency. This review makes a distinctive contribution by integrating AI/ML applications with manufacturing principles driven by sustainability. It introduces longitudinal analysis concerning algorithmic evolution from 2015 to 2025 and provides a novel approaches–challenges matrix that maps real industrial problems to specific AI/ML techniques. The review further links available datasets to their corresponding industrial sectors, allowing researchers to choose the contextually appropriate data source for optimizing assembly lines. By offering both a theoretical foundation and practical insights, this study aims to support researchers and contribute to the broader adoption and continued development of ML technologies in smart assembly line environments.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the rise of smart factories driven by the adoption of advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence, big data analytics, and Internet of Things (IoT) has sparked a transformative phase for assembly lines [1]. Manual assembly lines, where human workers carry out sequential tasks at different stations, have long been a cornerstone of mass production. Despite advances in automation, many industries continue to rely on these systems for their flexibility and cost-effectiveness. However, their overall efficiency is often limited by bottlenecks, typically caused by the slowest-performing stations. Lately, AI and ML have emerged as powerful tools to address these limitations to enhance performance and streamline operations. These technologies are transforming traditional assembly lines into intelligent, adaptive systems by analyzing production data, predicting bottlenecks, optimizing task allocation, and enabling real-time decision-making. This paper presents a comprehensive review of how these technologies are being applied to enhance the performance, reliability, and adaptability of assembly lines in a smart manufacturing environment. These technological advancements have played a crucial role in streamlining production line processes, improving efficiency, and increasing productivity [2].

Assembly lines are structured production systems where workers collaborate to manufacture a single product or a limited set of similar products [3]. These systems are commonly associated with mass-produced goods such as automobiles, home appliances, and other high-demand consumer products. It involves workers completing tasks at the station along a conveyor-driven flow. Although these systems aim to meet the high demand for consumer products by breaking down assembly into manageable tasks, traditional production methods still face numerous challenges, including downtime, inefficiencies, and quality control issues that can significantly affect productivity and profitability [4]. With the advent of Industry 4.0, integrating AI and ML technologies into assembly line operations has emerged as a transformative approach to address these challenges [5]. AI and ML technologies offer data-driven solutions, enabling enhanced decision-making, predictive maintenance, real-time monitoring, and adaptive optimization, thereby revolutionizing traditional manufacturing practices [6]. Sustainable intelligent manufacturing refers to the use of AI and machine learning to improve production performance while simultaneously reducing environmental impact. It combines intelligent decision-making, such as energy-aware scheduling, predictive maintenance that minimizes waste, and optimized material flows, with long-term sustainability goals. In essence, it promotes assembly systems that are not only efficient and adaptive but also resource-conscious and environmentally responsible [7]. Given the growing interest in leveraging AI and ML to improve assembly lines, a wealth of research has been conducted to explore their diverse applications [8]. The rapid development of algorithms and technologies has led to significant advancements in real-time data analysis and modeling integration within manufacturing systems [9]. However, despite this effort, there remains a lack of a comprehensive synthesis of the existing research landscape to consolidate key findings, identify trends, and outline prospects.

The complexity of assembly lines highlights where AI and ML can make an important change. Figure 1 shows the manufacturing sub-processes requiring assembly lines that can benefit from AI and ML applications. Assembly lines are complex, tightly coupled systems spanning design, machining, quality assurance, maintenance, inventory, and logistics, each offering distinct opportunities for AI to add value. In machining, deep learning models accurately predict tool wear from multi-sensor signals, thereby ensuring quality and minimizing unexpected downtime [10]. In assembly operations, AI-informed optimization enhances line balancing and model sequencing even under stochastic throughput, thereby reducing cycle time and work-in-process [11,12]. For quality control, computer vision with deep learning enables robust visual anomaly and surface-defect detection at scale [13]. At the system level, machine learning-based predictive maintenance is now a mature research area that increases uptime and reliability, with recent surveys detailing effective deep architectures and deployment considerations in industrial settings [14]. Upstream planning also benefits from machine learning methods to improve demand forecasting accuracy, helping set inventory levels and smooth production [15]. Downstream, reinforcement learning approaches are advancing fleet-routing and other logistics decisions in dynamic environments [16]. Collectively, these advances briefly show how AI is transforming assembly lines into adaptive, data-driven systems that raise efficiency, reduce errors, and enhance overall resilience.

Figure 1.

Manufacturing sub-processes with assembly lines for AI and ML applications.

Figure 2 shows some of the common challenges faced in traditional assembly lines. Artificial intelligence and machine learning techniques offer powerful solutions to several critical challenges in assembly line operations. For instance, neural networks adeptly navigate high-dimensional modeling tasks, enabling the estimation of assembly sequences and configuration optimization across hundreds of interconnected parameters [17]. To maintain adaptability in dynamic environments, online learning algorithms continually incorporate new data, allowing models to evolve with shifting production conditions [18,19]. Concurrently, ML-based pipelines unify diverse data inputs ranging from sensor feeds to spreadsheets by cleansing, harmonizing, and transforming them into a unified analytic framework [20]. Furthermore, by encapsulating institutional expertise into data-driven models, these systems democratize the availability of insights, enabling advanced decision-making beyond expert intuition [21]. Finally, explainable AI and behavioral modeling techniques increase transparency and trust by unveiling the internal mechanics of black box systems, facilitating a deeper understanding of equipment and process behavior [22].

Figure 2.

Common challenges in assembly line operations.

To address the growing interest in intelligent manufacturing, this paper presents a structured review of AI and ML applications in assembly line systems. It synthesizes current research, outlining key methodologies, implementation strategies, and areas of success. Beyond summarizing existing approaches, the review draws attention to underexplored areas and emerging opportunities for innovation. Ultimately, the aim is to equip both researchers and practitioners with a clearer understanding of how intelligent technologies can be harnessed to enhance flexibility, efficiency, and sustainability in modern assembly processes. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 outlines the scope of the study and the literature search methodology. Section 3 presents a comprehensive review of trends in AI/ML applications within assembly lines. Section 4 discusses the key challenges addressed by AI/ML in this context. Section 5 provides an overview of the AI/ML algorithms and models employed in assembly line research. Section 6 examines the evaluation metrics commonly used to optimize these algorithms. Section 7 reviews the datasets available for research in this domain. Section 8 summarizes the current challenges and outlines future directions for AI/ML applications in assembly lines. Finally, Section 9 concludes the paper.

2. Review Scope

This paper explores the application of AI and ML in workplace environments, with a focus on optimizing assembly line operations. Reviewing and categorizing the published research highlights the key models and algorithms used to improve efficiency and addresses how these approaches are represented in the literature. The focus is on understanding the strategies and model-driven methods while leaving out studies that do not directly contribute to these aspects of operational improvements. The research employed a systematic and interdisciplinary approach, using the search condition (assembly line AND optimization AND (AI OR ML)) AND (Assembly line AND artificial intelligence AND machine learning) in article titles and abstracts. The search was conducted across reputable scientific databases such as Scopus, Web of Science, IEEE Xplore, and Google Scholar. The search was focused on peer-reviewed articles published over the past ten years. The inclusion criteria for selecting studies were as follows: papers that explicitly discussed the use of AI or ML in optimizing assembly line operations, were published in English, and appeared in open access, peer-reviewed journals. Exclusion criteria included studies that were not in English, were pre-proofs, were duplicates, were irrelevant to the topic and data sought, or were not open access. The documents underwent a preliminary screening based on their titles and abstracts to filter out irrelevant studies. A subsequent comprehensive screening of full-text articles resulted in a final selection of studies directly relevant to the application of AI and ML in optimizing assembly line operations. The resulting findings provide insights into the state of the art, research gaps, and prospects.

3. Trends in AI and ML Applications in Assembly Lines

This section focuses exclusively on emerging AI and ML applications within assembly lines, highlighting how these technologies are currently being deployed across industrial settings. In the era of Industry 4.0, the convergence of big data, artificial intelligence, machine learning, and industrial automation is fundamentally reshaping the architecture and operation of assembly lines. These intelligent technologies are driving new levels of efficiency, adaptability, and responsiveness, replacing static systems with dynamic, data-driven infrastructures. One of the most pervasive trends is the shift toward data-centric manufacturing environments. The proliferation of sensor technologies and the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) has enabled continuous data collection from every segment of the production line. This influx of real-time data allows ML algorithms to detect patterns and predict outcomes, leading to enhanced process control and predictive maintenance. Holzinger et al. highlight how ML has evolved as a strategic tool for monitoring production line quality, identifying risks, and optimizing operational parameters across multiple industries [23]. Another key trend is the reconfiguration of assembly lines using AI-driven simulations and optimization models. Traditional heuristic-based design approaches are proving inadequate for handling the increasing complexity and customization demands in modern manufacturing. In response, AI is being used to simulate and evaluate multiple configurations under diverse production scenarios. Elyasi et al. introduce the concept of an “AI Matchmaker”, an intelligent tool that recommends equipment and layout designs by matching production needs with available resources, including second-hand machinery, thus improving cost efficiency and sustainability [1]. AI is also playing a growing role in workforce optimization, where effective coordination between automated systems and human workers is essential, especially in hybrid or collaborative assembly line environments. AI systems are being developed to match the skills of workers with real-time production demands while also considering ergonomic and organizational factors. These systems not only enhance task allocation but also address workforce adaptability, which is critical in the context of AI–human collaboration as promoted under Industry 5.0 principles [1,24].

The incorporation of predictive maintenance and intelligent condition monitoring is another defining trend. ML models analyze signals from motors, sensors, and control systems to predict equipment failures before they occur. Kudelina et al. review several ML-based diagnostic methods that monitor electromagnetic fields, vibrations, and current signatures, enabling early detection of faults in electrical machines used in assembly systems [25]. This transition from reactive to predictive maintenance significantly improves uptime and reduces operational costs. Further developments in computer vision and deep learning have revolutionized quality inspection. Instead of relying on manual or rule-based systems, AI can now detect anomalies, verify assembly stages, and monitor product integrity in real time. These techniques are being used to enhance in-line inspection systems, reducing human error and ensuring product quality consistency, as described in Wuest et al.’s review of smart manufacturing practices [26]. Additionally, collaborative robotics and human–robot interaction (HRI) have become essential components of modern assembly lines. Fathi et al. observe a growing research focus on optimizing task allocation in mixed human–robot assembly lines. Their analysis reveals that minimizing cycle time and maximizing resource utilization through AI-based planning algorithms has become a dominant objective in recent years [27]. Human–robot collaborative setups not only increase flexibility but also enable safer and more efficient work environments, particularly when guided by AI planners. From a system’s perspective, the integration of AI with Cyber–Physical Systems (CPSs) and digital twins is enabling real-time synchronization between the physical shopfloor and virtual models. According to Rai et al., this synchronization enables rapid reconfiguration, real-time decision-making, and enhanced visibility across supply chains and production stages [28]. AI thus forms the core engine of these smart manufacturing ecosystems.

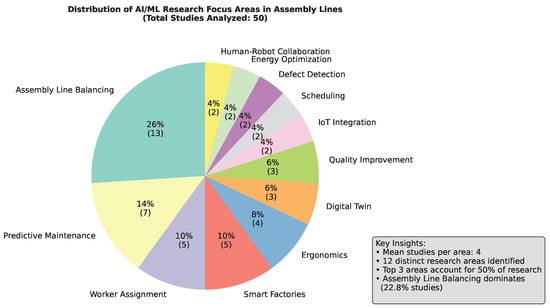

Sustainability is also emerging as a major driver of AI adoption in assembly lines. AI algorithms are being deployed to optimize energy consumption, reduce material waste, and enable circular manufacturing through the reuse of components and predictive life cycle analysis. Elyasi et al. highlight how AI can recommend re-purposing of aging equipment rather than outright replacement, aligning with environmentally conscious manufacturing goals [1]. Figure 3 presents a pie chart illustrating the proportional allocation of research efforts across twelve distinct application domains. Percentages and absolute frequencies (in parentheses) are displayed for each segment, revealing concentration in optimization-focused applications and emerging diversification into specialized domains including digital twins, IoT integration, and human–robot collaboration. Assembly line balancing emerges as the predominant research area, accounting for 26% of all studies (n = 13), representing more than one-quarter of the analyzed corpus and indicating sustained scholarly interest in the optimization of workstation task allocation and load distribution. Predictive maintenance constitutes the second-largest category at 14% (n = 7), reflecting the field’s emphasis on proactive equipment failure prevention and downtime reduction through prognostic analytics. Worker assignment and smart factories each represent 10% of the research landscape (n = 5 each), demonstrating equivalent attention to human resource optimization and integrated cyber–physical manufacturing systems. Ergonomics accounts for 8% (n = 4), suggesting growing recognition of human factors and occupational health considerations in automated environments. Digital twin technology and quality improvement initiatives each make up 6% of studies (n = 3 each), indicating emerging but still developing research streams in virtual modeling and defect reduction methodologies. The remaining research areas—IoT integration, scheduling, defect detection, energy optimization, and human–robot collaboration—each represent 4% of the corpus (n = 2 each), collectively accounting for 20% of all studies and highlighting diversification into specialized application domains. The distribution reveals a concentration pattern where the top three research areas (assembly line balancing, predictive maintenance, and worker assignment) collectively account for 50% of all research output, while the remaining nine areas exhibit more fragmented attention, with a mean of four studies per area across all domains, suggesting both established research priorities and emerging opportunities for investigation in underexplored areas. Assembly line balancing appears as the most dominant research topic because it has a direct and immediate effect on overall production efficiency. Even small improvements in balancing can significantly reduce cycle time and bottlenecks, making it a high-impact area for both practitioners and researchers. The increasing shift toward mixed-model and high-variety production has further amplified the importance of dynamic balancing strategies, which explains why this topic consistently attracts more attention than emerging areas such as IoT-driven assembly or digital twin systems. These application trends demonstrate how AI and ML are reshaping modern assembly systems. The following section builds on this by examining the industrial challenges that motivate the adoption of these technologies.

Figure 3.

Distribution of research focus areas in AI/ML applications in assembly line research.

4. Assembly Line Challenges Addressed by AI and ML

Assembly lines, being the backbone of industrial manufacturing, face increasing pressures from mass customization, market variability, and complex production demands. Despite these advancements, there are challenges, most notably around data integration, model scalability, and human–AI alignment. As Holzinger et al. pointed out, the effectiveness of AI in complex manufacturing scenarios depends on explainability, transparency, and human-centered design. These elements are critical not just for operational safety but for maintaining worker trust and regulatory compliance [23,24]. Overall, the trends in AI and ML applications within assembly lines reflect a decisive move toward intelligent, adaptive, and sustainable manufacturing. By blending real-time analytics, predictive modeling, and intelligent automation, AI is not only transforming operational performance but also redefining strategic decision-making in production environments [29,30]. In many factories, the practical deployment of AI and ML tools is held back by basic data-related limitations. Sensor readings are often inconsistently calibrated, labels may be missing, and data collection routines remain fragmented or manual. In addition, many facilities are still not IIoT-ready, which results in noisy, low-frequency, or incomplete datasets that cannot support reliable model performance. These issues create a noticeable gap between advanced AI technologies and the actual capabilities of the shopfloor, leading to unnecessary system complexity and limited impact. Bridging this industrial reality gap is essential for achieving meaningful and scalable AI adoption in an assembly environment. As industries transition into smart industries and beyond, AI and ML have emerged as transformative tools to address longstanding and emergent challenges across various dimensions, including but not limited to physical, operational, and human-centered aspects. One of the fundamental problems in assembly line management is sequencing mixed-model products to balance worker loads and minimize bottlenecks. Traditionally addressed through heuristics or rule-based methods, modern approaches leverage AI to explore broader solution spaces. Louis et al. compared mixed-model sequencing (MMS) and car sequencing (CS), finding that MMS offers more feasible configurations and better handles overload minimization, especially under increasing demand variability [31]. As product diversity expands, fixed production lines struggle to adapt. To tackle this, researchers have developed AI-supported models for the Reconfigurable Assembly Line Reconfiguring Problem (RALRP). Zhu et al. introduced a novel mixed-integer programming approach supported by an improved Variable Neighborhood Search (VNS) algorithm to dynamically adjust resources and task assignments based on production demand shifts [32].

A key challenge in assembly lines is efficiently balancing tasks across workstations, especially with robotic integration. Alakoc and Mhalla addressed this by proposing a heuristic algorithm for Robotic Assembly Line Balancing Problems (RALBPs), optimizing robot assignments and minimizing system costs. Their approach proved scalable and effective across large problem sets [33]. Feeding the right parts to the right place at the right time is a significant logistical challenge in modern assembly lines. Yu Lei et al. provided a comprehensive classification of tactical feeding strategies (e.g., kitting, batching, and sequencing), illustrating the need for AI-driven decision support to handle real-time variability and delivery optimization [34]. High-mix, low-volume environments require constant re-skilling of operators. Traditional training is time-intensive and error-prone. Gavish et al. demonstrated that Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) significantly enhance industrial training, reducing human error and shortening learning curves for complex assembly and maintenance tasks [35]. With the integration of sensors and IoT, modern factories generate enormous data volumes. However, converting raw data into actionable decisions remains a challenge. Wuest et al. emphasized how ML enables real-time quality monitoring, predictive maintenance, and production forecasting, though success requires overcoming issues related to data heterogeneity, labeling, and integration [26].

Modern AI systems are increasingly used to enhance human–robot collaboration by assigning tasks based on ergonomic data and individual capabilities, promoting safer and more adaptive work environments. Trstenjak et al. underscore the role of AI in supporting human-centered design, optimizing workplace conditions, and enhancing overall worker well-being [36]. Their literature review highlights AI’s potential to address ergonomic challenges in line with Industry 5.0 standards, which emphasize sustainable, resilient, and human-centric manufacturing systems [36]. The complexity of modern smart factories involves seamlessly linked cyber and physical systems. Chen et al. identified the need for AI-enhanced frameworks capable of supporting fast reconfiguration, communication between heterogeneous devices, and high-speed data processing across layers, from sensors to cloud analytics [37]. In addition, digital twins (DTs) have emerged as critical tools in managing variability and complexity in production systems. By creating real-time virtual representations of physical assets, DTs allow for dynamic monitoring, simulation, and optimization of assembly operations. A recent review of DT-driven smart manufacturing highlights how DTs can align with cyber–physical systems, big data, and industrial communication standards to enhance system responsiveness and adaptability in Industry 4.0 environments [38].

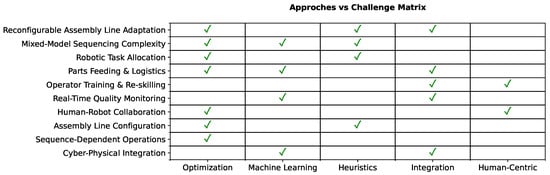

Figure 4 presents a summary matrix linking the major solution approaches with the corresponding industrial challenges in the context of advanced manufacturing and smart industries. The matrix highlights the extent to which various approaches address specific operational challenges. Analysis of the literature shows that optimization techniques are the most versatile, contributing to a wide range of challenges such as reconfigurable assembly line adaptation, mixed-model sequencing complexity, robotic task allocation, parts feeding and logistics, sequence-dependent operations, and human–robot collaboration. Machine learning is prominently applied to mixed-model sequencing complexity, real-time quality monitoring, and cyber–physical integration, indicating its strength in data-driven prediction and control. Heuristic methods are primarily used for mixed-model sequencing and assembly line configuration, reflecting their applicability in solving combinatorial and scheduling problems. The integration approach supports reconfigurable assembly line adaptation, operator training and re-skilling, and cyber–physical integration, underlining the importance of interconnected systems and interoperability. Meanwhile, human-centric approaches mainly address operator training and re-skilling and human–robot collaboration, emphasizing the role of human factors in enhancing flexibility and safety in intelligent manufacturing environments.

Figure 4.

Summary of various solution approaches vs. challenges matrix.

Beyond visual classification, the matrix in Figure 4 provides decision-oriented guidance for industrial deployment. For example, industries operating in high-variety or frequently changing environments, such as electronics manufacturing, benefit most from heuristic and optimization-based approaches, which provide flexible and fast solutions for sequencing and balancing problems under uncertainty. In contrast, data-intensive environments such as automotive manufacturing emphasize machine learning approaches due to the availability of large volumes of sensor data supporting predictive maintenance, quality inspection, and cyber–physical integration. Furthermore, human-centric approaches appear predominantly in training and collaboration challenges, reflecting the increasing importance of workforce integration and ergonomic optimization in Industry 5.0 environments. Integration-oriented approaches dominate challenges related to reconfigurability and CPS, indicating that technical interoperability and system architecture maturity remain fundamental enablers for AI deployment.

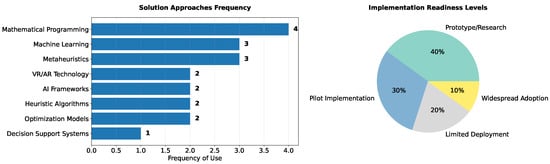

Figure 5 illustrates the frequency of various approaches and the corresponding implementation readiness levels within smart industries. The bar chart on the left presents the frequency of use of different approaches. Mathematical programming emerges as the most frequently employed technique (n = 4), followed by machine learning and metaheuristics (each with n = 3). Approaches such as VR/AR technology, AI frameworks, heuristic algorithms, and optimization models exhibit moderate use (n = 2), whereas decision support systems show comparatively limited application (n = 1). These results indicate a predominant reliance on analytical and data-driven optimization methods in the assembly lines. The pie chart on the right summarizes the readiness levels for Industry 4.0 technologies. The largest proportion (40%) corresponds to the Prototype/Research stage, indicating that many solutions remain under development. Pilot Implementation accounts for 30%, showing growing experimentation and limited field testing. Limited Deployment represents 20%, while only 10% of initiatives have achieved Widespread Adoption. This distribution suggests that despite significant research activity, full-scale industrial integration of various solution approaches remains at an early stage of maturity. The higher reliance on mathematical programming is largely due to its long history in deterministic planning problems, where constraints are well defined and datasets are relatively small. These methods remain attractive because they provide transparent and often optimal solutions. However, the readiness level distribution reveals that many AI and ML solutions are still in early prototype phases. This gap reflects practical challenges such as inconsistent shopfloor data, integration difficulties with legacy systems, and the need for rigorous real-time validation before full industrial deployment.

Figure 5.

Frequency and readiness level of solution approaches.

Despite the rise of digital twins and simulations, there are gaps between virtual optimization and real-world implementation. Lei et al. highlighted how ML-integrated simulations using FlexSim and IoT can improve schedule efficiency in multi-variety, small-batch assembly, but require robust calibration and real-time validation mechanisms [34]. AI and ML tools are also addressing ergonomic and human workload challenges. Workers face cognitive and physical strain due to increased variability in assembly tasks. Research shows that balancing task assignments via ML can help reduce fatigue and error rates by dynamically adjusting workloads based on real-time feedback and task complexity. In addressing balancing challenges, Zhang proposed an improved Immune Algorithm for SALBP-1, incorporating advanced techniques like immune adjustment and vaccine-based optimization. This approach improves search efficiency and avoids population degradation, resulting in effective task-to-station assignments that minimize workstation count and maintain task precedence [39]. For the automotive sector, battery assembly presents unique challenges due to safety, precision, and thermal considerations. Kwade et al. outlined how AI and ML help manage material properties, electrode coating parameters, and multi-step production flows to maintain quality while scaling up cost-efficiently [40]. In addition to ergonomic design and AI-driven workload management, effective adaptation to smart industry requires continuous workforce development. Erol et al. highlight that the abstract and complex nature of smart manufacturing technologies can hinder implementation. They propose a scenario-based learning framework to support hands-on, competence-driven training, ensuring that human workers can meaningfully engage with AI systems and digital tools [41]. Finally, tactical decisions such as storage layout, routing, and feeding strategies significantly influence upstream and downstream efficiency [41].

AI is also being used to dynamically generate and test tactical layout configurations, helping achieve balanced throughput while maintaining operator accessibility and meeting material constraints. Cameron explores the paradox of algorithmic management in the gig economy, coining the term “good bad job” to describe roles where algorithmic systems foster perceived autonomy through constant but narrow choices. Although situated in the ride-hailing sector, the findings are transferable to AI-managed industrial environments, where workers interact with algorithms that segment tasks, issue nudges, and monitor performance. This study underscores how algorithmic systems can elicit both compliance and engagement, which is highly relevant for understanding human acceptance of AI systems in smart factories and robotic assembly lines [42]. Table 1 presents the key challenges in modern assembly line optimization alongside the proposed AI/ML-based solutions and supporting studies. These challenges range from reconfigurable assembly line adaptation, mixed-model sequencing complexity, and robotic task allocation to operator training, workforce competency gaps, and human–robot collaboration.

Table 1.

Key assembly line challenges, AI/ML solutions, and supporting references.

5. AI and ML Algorithms and Models Employed in Assembly Lines

Optimizing assembly lines in the context of smart industries involves the deployment of advanced algorithms capable of addressing diverse challenges such as workforce variability, balancing complexity, and dynamic reconfiguration. This section reviews studies presenting a distinct computational model or algorithmic framework used to enhance assembly line efficiency [60]. Liu et al. developed a two-stage stochastic programming model for the Assembly Line Worker Assignment and Balancing Problem (ALWABP), incorporating a Genetic Algorithm (GA) enhanced with K-means clustering and Variable Neighborhood Search (VNS) [61]. This approach addresses uncertainties related to worker flexibility and availability, particularly in systems using temporary or disabled workers [61]. Janardhanan et al. applied a Migrating Birds Optimization (MBO) algorithm to solve the Two-Sided ALWABP (TALWABP) [48]. Their approach, which mimics natural V-formation flight behavior, shows superior convergence and solution quality compared to ant colony and simulated annealing methods [48]. Khalili et al. introduce a queuing theory-based approach to assembly line balancing, enhanced with fuzzy prioritization techniques [62]. Their method models multiple operator-machine assignment scenarios and evaluates them under uncertainty using fuzzy logic. Key parameters such as arrival and service rates are treated as fuzzy numbers, and fuzzy ranking methods are applied to identify the most profitable configuration. This approach effectively incorporates real-world ambiguity in operator efficiency and system load, offering a decision support tool that balances cost and throughput under uncertainty [62].

Zheng et al. tackled the Multi-Objective Two-Sided Assembly Line Balancing Problem (MOATALBP) using a Harmony Search Algorithm based on Pareto Entropy (PE-MHS) [49]. The model accounts for real-world constraints such as zoning and synchronizing, achieving well-distributed Pareto-optimal solutions [49]. Zhang proposed an improved Immune Algorithm to solve the Simple Assembly Line Balancing Problem of Type 1 (SALBP-1). Enhancements such as vaccine extraction and immune selection were introduced to prevent population degradation and ensure solution diversity [39]. Li et al. propose a Multi-Objective Programming Model for balancing Mixed-Model Two-Sided Assembly Lines (MM-TALs) with numerous constraints, including precedence, zoning, synchronous, and positional rules [50]. Their solution approach is a Multi-Objective Hybrid Imperialist Competitive Algorithm (MOHICA), enhanced with the Sigma method, novel merging logic, and Late Acceptance Hill-Climbing (LAHC) for local search refinement. Experimental results across benchmark datasets demonstrate MOHICA’s superiority over NSGA-II, NSGA-III, and other metaheuristics in both balance quality and computational efficiency [50]. Pérez-Wheelock et al. introduced a multi-period, demand-driven re-balancing model (DDALRP) for assembly lines, focused on continuously adapting to dynamic production demands [63]. The model uses a nonlinear, multi-objective combinatorial optimization approach and incorporates worker learning and forgetting (L&F) curves. Solved using a GA, the study evaluated 162 scenarios, providing valuable insights into how worker skill dynamics impact reallocation strategies across demand shifts [63].

Kim et al. developed a model to balance mixed-model assembly lines while incorporating unskilled temporary workers [64]. They formulated three optimization models including Integer Linear Programming (ILP), Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP), and a hybrid Genetic Algorithm. The developed GA included special operators to maintain feasibility and was found superior in computational performance. The study reveals a trade-off between labor cost and workstation efficiency, highlighting the operational value of incorporating low-cost, unskilled labor under structured algorithmic management [64]. Li et al. address the Robotic Two-Sided Assembly Line Balancing Problem (RTALBP) with sequence-dependent setup times and robot setup variability—a rarely tackled issue in the current literature [65]. They propose a Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) model aimed at minimizing cycle time. Given the NP-hard nature of the problem, the authors test 13 metaheuristic algorithms, among which Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) and Migrating Birds Optimization (MBO) deliver optimal or near-optimal solutions. Their findings show that prior mathematical models may produce infeasible results under realistic setup constraints, making their metaheuristic suite a robust solution for both small and large instance scales [65]. Nie et al. addressed the Mixed-Model Assembly Line Level Scheduling Problem (MMALSP) in JIT production settings, proposing a multi-objective optimization model that minimizes part consumption variance, inventory cost, and transport load [66]. The model is solved using a GA enhanced with a Delivery Scheduling Algorithm (DSA) and a dimensionless fitness function for objective aggregation. Their results show improved JIT performance and operational balance across varying part delivery conditions [66].

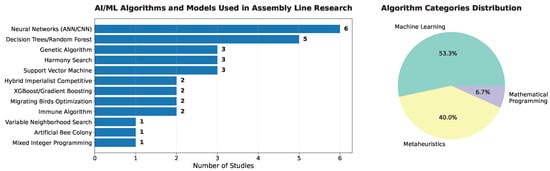

Figure 6 illustrates the distribution of AI and ML algorithms applied in assembly line research, highlighting both the specific algorithmic approaches (left) and their broader categorical distribution (right). The bar chart indicates that neural networks (ANN/CNN) are the most frequently utilized algorithms, appearing in six studies. This demonstrates a strong research focus on deep learning methods for pattern recognition, predictive modeling, and adaptive decision-making in assembly systems. Decision Trees and Random Forests follow with five studies, reflecting their effectiveness in classification, fault detection, and decision support applications. Genetic Algorithms, Harmony Search, and Support Vector Machines each appear in three studies, suggesting their continued relevance for optimization and predictive control tasks. Several other algorithms, such as Hybrid Imperialist Competitive, XGBoost/Gradient Boosting, Migrating Birds Optimization, and Immune Algorithm, have moderate representation (two studies each), indicating ongoing exploration of hybrid and nature-inspired methods. Less frequently applied algorithms include Variable Neighborhood Search, Artificial Bee Colony, and Mixed-Integer Programming, each cited in one study. The pie chart on the right categorizes these algorithms into three main groups: machine learning, metaheuristics, and mathematical programming. The largest share corresponds to machine learning methods (53.3%), underscoring the dominant trend toward data-driven and learning-based approaches in assembly line optimization. Metaheuristics account for 40% of the studies, highlighting their continued importance in solving complex, nonlinear optimization problems. Mathematical programming represents a smaller proportion (6.7%), reflecting its more limited use in dynamic and data-intensive contexts.

Figure 6.

AI and ML algorithms and model used in assembly line research and their distribution.

As shown in Table 2, choosing the right algorithm depends strongly on the structure of the assembly line, the type and amount of available data, and the specific requirements of the industry. Machine learning methods tend to perform best in data-rich environments, such as automotive and electronics manufacturing, where continuous sensor streams support accurate predictive maintenance, defect detection, and modeling of human–machine interactions. Metaheuristic algorithms, on the other hand, are more effective in complex, high-variety, and reconfigurable assembly settings, which are common in electronics and appliance production. These environments involve challenging line balancing and scheduling problems that are highly nonlinear and combinatorial in nature. Mathematical optimization remains well-suited to more deterministic and medium-scale assembly systems, such as automotive chassis or white-goods manufacturing, where constraints are clearly defined, and system variability is limited.

Table 2.

Comparison of algorithmic approaches in assembly applications.

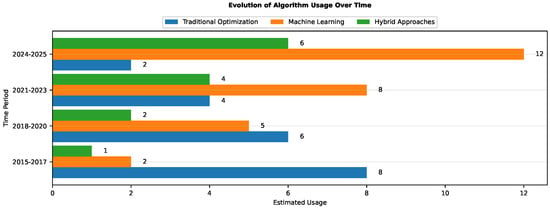

Figure 7 presents the temporal evolution of algorithmic methodologies employed in assembly line research spanning from 2015 to 2025, revealing significant shifts in methodological preferences within the field. The data is organized into four discrete time periods and categorize approaches into three distinct classes: traditional optimization, machine learning, and hybrid approaches. During the earliest period (2015–2017), traditional optimization methods clearly dominated the research landscape with an estimated usage in eight studies, while machine learning approaches were used in only two studies, and hybrid methodologies were barely present with mention in only one study. This distribution reflects the field’s initial reliance on established mathematical optimization techniques. The subsequent period (2018–2020) marked the beginning of a transitional phase, where the use of traditional optimization can be observed in only six studies, machine learning use expanded to five studies, and hybrid approaches remained relatively modest with a mention in only two studies, suggesting gradual acceptance of data-driven methodologies. By 2021–2023, a clear inflection point emerged, the use of traditional optimization further decreased to four studies, the use of machine learning surged to eight studies, and the use of hybrid approaches doubled (four studies), indicating that machine learning had begun to surpass conventional methods. The most recent period (2024–2025) demonstrates a decisive paradigm shift, with machine learning reaching twelve studies, representing the highest usage across all categories and time periods, while the use of traditional optimization is at its lowest (two studies), and the use of hybrid approaches increased (six studies). This progression illustrates not only the declining prominence of classical optimization techniques but also the increasing trend in recognizing that hybrid methodologies combining traditional domain knowledge with machine learning capabilities may offer enhanced performance for complex assembly line optimization problems. The sharp rise in machine learning adoption after 2020 is closely tied to broader technological developments—such as advances in GPU/TPU computing, cheaper data storage, and the rapid expansion of IIoT infrastructure. These developments enabled manufacturers to collect richer datasets and train more complex models. The growing interest in hybrid methods also reflects a practical realization: combining mathematical optimization with data-driven ML techniques often delivers better performance in complex and variable assembly environments than relying on either approach alone.

Figure 7.

Temporal distribution of algorithmic methodologies in assembly line research (2015–2025).

6. Evaluation Metrics Used in Assembly Line Research

Incorporating machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) into assembly lines has transformed how performance is monitored and optimized. Traditional metrics like cycle time and output quality now coexist with advanced indicators measuring adaptability, sustainability, digital integration, and human–machine synergy. This section provides a comprehensive review of the evaluation metrics used across various studies applying ML and AI in industrial assembly lines. Cycle time, throughput, and idle time reduction remain primary indicators of operational success in AI-augmented assembly systems. In the context of real-time performance management, Schneider Electric implemented a digital transformation strategy using real-time dashboards to monitor efficiency. Their approach featured metrics such as Overall Equipment Effectiveness (OEE), First Pass Yield (FPY), and unit production per shift to evaluate system responsiveness and productivity [67].

Moreover, error detection and predictive maintenance are evaluated using machine learning classification accuracy, precision, and recall. These indicators are applied in anomaly detection systems that preempt machine failures and reduce unplanned downtime, key for maintaining consistent assembly throughput [6]. Human–machine collaboration necessitates metrics that account for worker safety, comfort, and adaptability. Evaluation frameworks now integrate ergonomic risk scores, derived from sensor-based motion analysis; task completion time variability; and cognitive load indices, which assess the complexity of interactions with robotic interfaces. These metrics are pivotal in ensuring that AI systems complement human capabilities without imposing undue strain. Studies emphasize adaptive training systems and collaborative robot feedback loops to monitor and enhance worker experience [68]. For instance, one study used real-time Heart Rate Variability (HRV) and stress prediction accuracy to evaluate worker stress in smart factories [69]. Several studies focus on sustainable manufacturing performance by utilizing composite indices that track energy consumption per unit output, waste generation rates, and carbon emission intensity. For example, a study on Indian manufacturing firms introduced a Sustainability Performance Framework that encompasses environmental, economic, and operational metrics to assess AI-enabled lean practices [70]. Another paper emphasized AI’s role in supporting green manufacturing by evaluating energy efficiency and waste reduction in real-time assembly operations [71].

As digital twins and real-time data analytics gain traction, new system-wide metrics have emerged, including Digital Twin Accuracy (the difference between predicted and actual outcomes), Real-Time Data Integration Rate, and Sensor Latency and Update Frequency. A digital twin study on glass production utilized these metrics to evaluate the simulation fidelity and responsiveness of predictive AI models in dynamic production environments [53]. Similar studies measured synchronization delays and cyber–physical system alignment to ensure seamless digital integration [72]. Integrated evaluation frameworks, such as the Sustainable Organizational Performance Index (SOP) and the Lean Compliance Index, combine multiple performance dimensions into a unified score. These are particularly relevant for long-term planning and strategic alignment of AI investments with organizational goals. Studies also use Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) techniques like AHP and TOPSIS to weigh and synthesize diverse metrics [73,74]. One study also proposed composite digital readiness and automation indices to assess implementation maturity in Industry 4.0 assembly lines [75].

Recent studies consistently demonstrate that Overall Equipment Effectiveness (OEE) has evolved from a static monitoring metric into a machine learning-enabled performance indicator for predictive decision-making. Dobra and Josvai show that supervised learning enables reliable short- and long-term OEE forecasting, significantly outperforming traditional estimation approaches [76,77]. Similarly, Hassani et al. validate the effectiveness of ensemble and deep learning models for predicting OEE under real industrial conditions [78]. From a maintenance perspective, Mohan et al. integrate OEE with MTBF and MTTR within a data-driven Total Productive Maintenance (TPM) framework to reduce downtime and enhance equipment availability [79]. Quality integration is further illustrated by Silva et al., who employ OEE alongside First Pass Yield (FPY) and defect rates to support zero-defect manufacturing strategies [80].

FPY has emerged as a key quality-oriented indicator for assessing real shopfloor performance, reflecting both process stability and manufacturing discipline. Riccio et al. integrate FPY with MTBF and MTTR within predictive maintenance frameworks [81], while Martinek et al. and Adipraja et al. demonstrate the effectiveness of machine learning in predicting yield performance at both process and batch levels [82,83]. Hybrid optimization techniques in quality engineering are further illustrated by Wang et al., while Silva et al. reinforce how FPY complements OEE in achieving zero-defect manufacturing objectives [80,84]. Collectively, these findings validate FPY as a core quality KPI for AI-enabled assembly systems. MTBF and MTTR remain essential reliability indicators for assessing operational stability and maintenance effectiveness. Recent studies confirm their integration within AI-driven predictive maintenance frameworks across diverse sectors, including heavy industry and mining [85] and renewable energy systems [86]. In manufacturing environments, Mohan et al. and Riccio et al. embed MTBF and MTTR within intelligent TPM strategies [79,81], supported by empirical evidence from real industrial case studies [87,88,89], which consistently demonstrate their impact on improving availability and reducing downtime. These findings establish MTBF and MTTR as industry-validated metrics for evaluating maintenance maturity and system reliability.

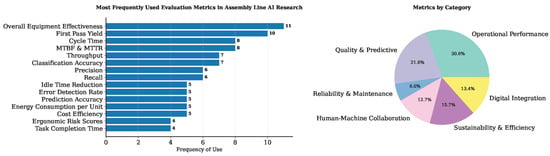

In Figure 8, the bar chart on the left presents a frequency distribution of AI and ML evaluation metrics employed in assembly line research, revealing cycle time and throughput as the predominant performance indicators, with a mention in eight and seven occurrences, respectively. Classification accuracy and Overall Equipment Effectiveness (OEE) demonstrate moderate utilization (six studies each), while precision and recall metrics each appear in six studies, indicating substantial emphasis on predictive model validation. Mid-frequency metrics include idle time reduction, error detection rate, and production rate (six studies each), alongside energy consumption per unit and cost efficiency (five studies each). Lower-frequency metrics comprise First Pass Yield, ergonomic risk scores, task completion time, and waste generation rate, each mentioned in four studies. The right pie chart categorizes these metrics into six distinct domains, with operational performance constituting the largest proportion at 26.1%, followed closely by quality and predictive metrics at 25.2%. Sustainability and efficiency metrics account for 18.3%, digital integration for 15.7%, and human–machine collaboration for 14.8%, suggesting a relatively balanced but operationally focused evaluation framework across contemporary assembly line research.

Figure 8.

Evaluation metrics in assembly line research and their categorical distribution.

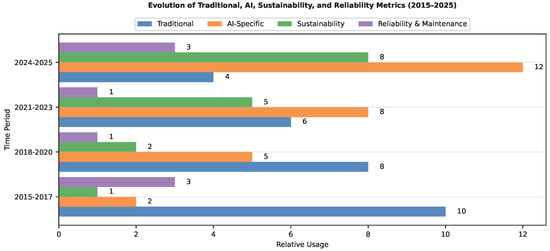

Figure 9 demonstrates the temporal evolution of metric categories across four time periods (2015–2017, 2018–2020, 2021–2023, and 2024–2025), categorized into traditional, AI-specific, and sustainability metrics. The 2015–2017 period exhibits clear dominance of traditional metrics with a relative usage in ten studies, while AI-specific metrics are mentioned in only two studies and sustainability metrics remain minimal with a mention in only one study, reflecting the field’s initial focus on conventional performance measures. During 2018–2020, traditional metrics declined substantially with a mention in eight studies, concurrent with expansion of AI-specific metrics (five studies) and marginal growth in sustainability metrics (two studies). The 2021–2023 period demonstrates continued decrease in the use of traditional metrics (six studies), while AI-specific metrics grew (eight studies) and the use of sustainability metrics also increased (five studies) units, marking a pivotal transition toward data-driven and environmentally conscious evaluation frameworks. The most recent period (2024–2025) reveals a dramatic paradigm shift where the use of traditional metrics can only be seen in four studies, AI-specific metrics surged to twelve studies representing peak utilization, and the used sustainability metrics can be observed in eight studies. This progression indicates not only the displacement of conventional metrics by AI-centric performance indicators but also the field’s increasing integration of environmental and resource efficiency considerations into evaluative frameworks.

Figure 9.

Temporal distribution of evaluation metrics in assembly line research (2015–2025).

7. Available AI and ML Datasets for Assembly Line Research

Most AI and ML approaches are data-driven, and advancing the usage of the approaches in assembly line research highly depends on the availability of the right data. These data serve as the backbone for developing and testing models, whether the focus is on monitoring human activity, improving robotic assembly, predicting equipment failures, or enhancing product quality. What makes this field unique is the variety of data sources available. Some datasets capture detailed human movements or robotic demonstrations, while others record streams of sensor data from smart factories, quality control metrics from automotive production, or even communication signals within industrial environments. There are also broader statistical and economic datasets that give context to manufacturing performance at a larger scale. This section presents the most widely used datasets grouped according to their application area. Together, they highlight the diversity of the available resources for researchers, while also pointing to areas where data remains limited and further development is needed.

7.1. Assembly Process and Human Activity Datasets

- HA4M Dataset—Multimodal Monitoring of an Assembly Task: A comprehensive multimodal dataset containing 217 videos of 12 assembly actions performed by 41 subjects building an Epicyclic Gear Train. It includes synchronized RGB frames, depth maps, IR frames, point clouds, and skeleton data for human action recognition and motion analysis in manufacturing contexts [90].

- –

- Industrial Applications: Operator behavior analysis, ergonomic risk evaluation, and human action recognition.

- REASSEMBLE—Multimodal Dataset for Contact-rich Robotic Assembly: A dataset containing 4551 demonstrations (4035 successful) of robotic assembly and disassembly tasks based on the NIST Assembly Task Board 1 benchmark. It features multimodal sensor data including event cameras, force–torque sensors, microphones, and multi-view RGB cameras across 781 min of operation [91].

- –

- Industrial Applications: Robotic precision assembly, peg-in-hole tasks, force- controlled assembly, and training robotic manipulation models.

- Future Factories Platform Manufacturing Dataset V2: Industry-grade datasets captured during an 8-h continuous manufacturing assembly line operation. It includes both analog time-series data and multimodal synchronized system data with images, covering communication protocols, actuators, sensors, and cameras adhering to industry standards [92].

- –

- Industrial Applications: Smart factory monitoring, digital twin synchronization, and equipment coordination in multi-stage assembly lines.

- ProMQA-Assembly—Multimodal Procedural QA Dataset: A dataset containing 391 question–answer pairs requiring multimodal understanding of human activity recordings and instruction manuals for assembly tasks. It focuses on toy vehicle assembly with instruction task graphs and a semi-automated QA annotation approach using LLMs [93].

- –

- Industrial Applications: Operator assistance, assembly instruction verification, and human–machine collaborative training systems.

- Event-based Dataset of Assembly Tasks (EDAT24): A dataset featuring manufacturing primitive tasks (idle, pick, place, screw) captured using a DAVIS240C event camera. It contains 100 recorded samples per task type, totaling 400 samples of basic assembly actions performed by human operators [94].

- Industrial Applications: High-speed assembly detection, real-time activity monitoring, and lightweight AI for embedded manufacturing devices.

7.2. Smart Manufacturing and IoT Datasets

- Smart Manufacturing IoT–Cloud Monitoring Dataset: Real-time sensor data for predictive maintenance and anomaly detection containing 10,000 time-stamped observations at one-minute intervals. It includes temperature, machine speed, production quality score, vibration level, energy consumption, and optimal conditions binary flags [95].

- –

- Industrial Applications: Predictive maintenance, energy optimization, fault detection, and real-time line balancing.

- Industrial IoT Fault Detection Dataset: Sensor data focusing on vibration, temperature, and pressure measurements with corresponding fault labels for industrial fault detection applications in manufacturing environments [96].

- –

- Industrial Applications: Motor bearing diagnosis, pump and compressor fault detection, and vibration-based predictive maintenance.

- Real-Time IoT-Driven Production System Dataset: Comprehensive sensor data for digital twin machine learning optimization containing 15,000+ observations with 10+ features collected at 30 s intervals for production efficiency analysis [97].

- –

- Industrial Applications: Digital twin calibration, model-based scheduling, and throughput optimization.

- Multi-stage Continuous-Flow Manufacturing Process Dataset: Real process data from Detroit-area production line featuring high-speed continuous manufacturing with parallel and series stages. It contains time-stamped observations with temperature, speed, quality scores, vibration, and energy consumption metrics [97].

- –

- Industrial Applications: Continuous-process optimization, energy modeling, and bottleneck analysis in high-speed lines.

7.3. Quality Control and Computer Vision Datasets

- Excavators Computer Vision Dataset (Roboflow Universe): Computer vision dataset for construction equipment detection containing 2000+ annotated images with YOLO-format annotations for object detection and recognition applications in industrial environments [98].

- –

- Industrial Applications: Industrial object detection, workplace safety detection, and equipment tracking.

- Bosch Production Line Performance Dataset: Industrial dataset with 1183 samples and 968 features designed for predicting parts quality control in automotive manufacturing. It features a binary classification target for production line performance assessment [99].

- –

- Industrial Applications: Part defect prediction, quality control in automotive electronics, and anomaly detection.

- Mercedes-Benz Greener Manufacturing Dataset: Anonymized dataset with 4209 samples and 378 features aimed at reducing time cars spend on test benches. It focuses on optimizing manufacturing processes and implementing sustainable production practices [100].

- Industrial Applications: Sustainable automotive testing, reducing cycle time, and optimizing inspection workflows.

7.4. Communication and RF Datasets

- Radio Frequency Measurements for Manufacturing Environments: NIST dataset containing RF measurements at 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz in industrial environments using PN code sounding methodology. It includes complex impulse responses and spectrum analysis traces validated through ray tracing for wireless system design in manufacturing [101].

- –

- Industrial Applications: Wireless reliability studies, smart factory communication, and IIoT network design.

- Wireless Systems for Industrial Environments Dataset: Comprehensive RF propagation measurements covering factory communication systems, network performance analysis, and industrial IoT connectivity assessment in real manufacturing facilities [102].

- Industrial Applications: Factory-wide IoT connectivity modeling and industrial robot communication reliability.

7.5. Statistical and Economic Datasets

- Eurostat Industrial Production Statistics (TEIIS090): European statistical database containing monthly and annual industrial production indices covering 27 EU countries. It includes manufacturing statistics, production volumes, value-added metrics, and sectoral breakdowns for economic analysis [103].

- –

- Industrial Applications: Macro-level manufacturing forecasting, sustainability benchmarking, and sector productivity analysis.

- US Manufacturing Efficiency and Consumption Dataset: Government dataset providing consumption efficiency statistics, energy utilization metrics, and manufacturing performance indicators across various industrial sectors in the United States [104].

- –

- Industrial Applications: Energy benchmarking, equipment efficiency comparison, and sustainability KPI reporting.

7.6. Specialized Manufacturing Datasets

- Fraunhofer Production ML Datasets Collection: Curated collection including bearing failure experiments, milling machine operations, CFRP composite testing, mechanical analysis for fault diagnosis, and cylinder printing process data for various manufacturing applications [105].

- –

- Industrial Applications: Milling optimization, composite defect detection, and mechanical system prognostics.

- Smart Manufacturing Temperature Regulation Dataset: Dataset on fuzzy PID control applications in industrial temperature regulation systems, containing control parameters, temperature profiles, and system response data for process control optimization. Reference: [106].

- –

- Industrial Applications: Process control optimization, smart thermal regulation, and adaptive PID design in manufacturing.

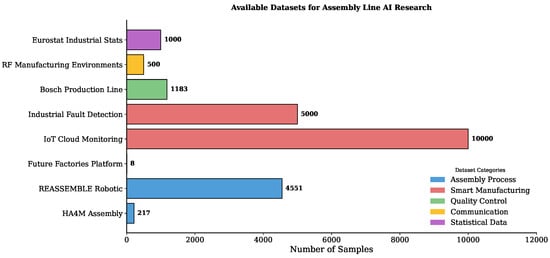

Figure 10 presents some datasets from the list above categorized by application domain and quantified by sample size, revealing substantial heterogeneity in data availability across different manufacturing contexts. The presented datasets span five distinct categories: assembly process, smart manufacturing, quality control, communication, and statistical data. The IoT cloud monitoring dataset demonstrates the largest scale with 10,000 samples, positioning it as the most extensive resource for smart manufacturing applications. Industrial fault detection, also within the smart manufacturing category, provides 5000 samples, representing the second-largest dataset and emphasizing the research community’s focus on anomaly detection and predictive maintenance. The REASSEMBLE Robotic dataset contains 4551 samples dedicated to assembly process optimization, indicating substantial efforts in robotics and automation research. Medium-scale datasets include the Bosch production line (1183 samples) for quality control applications and Eurostat industrial stats (1000 samples) providing statistical manufacturing data, both offering sufficient sample sizes for traditional machine learning applications but potentially limiting for deep learning architectures. Smaller-scale resources comprise RF manufacturing environments with 500 samples addressing communication and connectivity challenges in industrial settings, HA4M assembly with 217 samples for assembly process research, and future factories platform with merely 8 samples, which likely serves as a demonstrative or pilot dataset rather than a comprehensive training resource. The distribution reveals a critical imbalance: smart manufacturing datasets collectively provide 15,000 samples (71% of total), while assembly process, quality control, communication, and statistical categories remain comparatively data-scarce, potentially constraining research progress in these domains and highlighting the need for expanded data collection efforts in underrepresented application areas to enable robust AI model development across the full spectrum of assembly line optimization challenges.

Figure 10.

Some assembly line research datasets for AI and ML characterized by sample size and application domain.

To give companies clearer methodological guidance, the reviewed datasets can be grouped into four industrial decision-oriented clusters. First, assembly process and human activity datasets (e.g., HA4M, EDAT24, ProMQA-Assembly) are primarily suitable for ergonomics analysis, operator training, and human–machine interaction studies. Second, smart manufacturing and IoT datasets (e.g., Smart Manufacturing IoT–Cloud Monitoring and Industrial IoT Fault Detection) support predictive maintenance, condition monitoring, and performance analytics in IIoT-enabled factories. Third, quality inspection and computer vision datasets (e.g., Bosch Production Line and Mercedes-Benz Greener Manufacturing) directly serve automotive and electronics quality assurance and defect prediction tasks. Finally, statistical and macro-level datasets (e.g., Eurostat and U.S. manufacturing databases) are better suited for benchmarking, policy analysis, and long-term performance evaluation rather than real-time control or optimization. This structured view enables both researchers and practitioners to select datasets that align with their sector, decision level, and data readiness.

8. Challenges and Prospects

Despite significant advancements in integrating AI and ML into assembly line operations, several challenges and limitations persist. Firstly, data integration remains a critical hurdle. Manufacturing environments often generate heterogeneous data from diverse sensors and systems, posing difficulties in standardizing, integrating, and analyzing data in real time effectively, as highlighted by [26]. This heterogeneity complicates the development of robust predictive models and real-time decision-making tools. Secondly, scalability and computational complexity present substantial challenges. Many advanced ML and AI algorithms, while effective in controlled or smaller-scale environments, struggle to scale efficiently to real-world, large-scale assembly lines due to computational demands [32,38]. High computational costs can restrict real-time responsiveness, which is essential for dynamic and adaptive assembly line operations. Human–AI alignment and workforce acceptance constitute another critical limitation. AI systems must not only be effective but also comprehensible and trustworthy to human workers. Guo and Sikora et al. emphasize challenges around explainability, transparency, and ergonomics [10,11]. These can negatively affect worker acceptance, potentially reducing overall system effectiveness and productivity. Furthermore, ethical considerations, privacy concerns, and compliance with regulatory frameworks add complexity to deploying these intelligent systems. Moreover, the gap between virtual simulations and physical implementations can limit the practical effectiveness of digital twin technology [34]. Notably, discrepancies between simulated and real-world outcomes due to calibration issues or insufficient model validation can hinder accurate decision-making and predictive reliability. Lastly, cybersecurity poses significant risks as the interconnected nature of smart manufacturing increases vulnerability to cyber attacks, potentially disrupting production, compromising safety, and incurring substantial economic losses.

Looking ahead, numerous research opportunities exist to overcome current limitations and further advance AI and ML integration within assembly lines. One promising direction is the development of advanced data integration frameworks capable of effectively managing and standardizing heterogeneous data sources. Future research could focus on innovative data fusion methodologies, real-time data processing, and the enhancement of interoperability standards, facilitating seamless integration of AI systems into production environments [25]. Improving scalability and computational efficiency represents another vital research area. Leveraging advanced computing paradigms, such as edge computing, federated learning, and cloud-based infrastructures, can significantly enhance computational efficiency, enabling sophisticated AI models to operate effectively at scale and in real time [9,38]. The human-centric design of AI and ML systems offers substantial potential for future research. Developing explainable AI (XAI) methodologies and transparent algorithms that clearly communicate decision-making processes to workers could foster greater trust, acceptance, and cooperation between humans and machines. Investigating AI-driven ergonomic optimization and personalized adaptive interfaces can further enhance workforce integration and productivity, as discussed by [36].

Additionally, refining digital twin technologies through enhanced real-time validation and calibration mechanisms could bridge the gap between virtual simulations and physical realities. Research focused on improving the accuracy of digital twin predictions and exploring hybrid digital–physical validation techniques would enhance their practical utility and reliability [10,53]. Further, exploring sustainable manufacturing solutions powered by AI and ML presents significant research opportunities. Developing AI-driven strategies that optimize energy consumption, reduce waste, and promote circular manufacturing models aligns with global sustainability goals, offering both economic and environmental benefits, as shown by [1]. Lastly, addressing cybersecurity threats by designing robust, secure-by-design AI systems is essential for the safe adoption of smart manufacturing technologies. Research into advanced cybersecurity frameworks, intrusion detection systems, and resilient network architectures will be crucial in ensuring the secure and uninterrupted operation of future intelligent assembly lines.

Moving forward, advancing intelligent assembly systems will depend on more robust and interoperable data integration frameworks capable of harmonizing heterogeneous sensor streams and enabling fast, reliable decision-making on the shopfloor. To support the scalable deployment of AI, manufacturers will increasingly require edge-based computing, federated learning strategies that protect data privacy, and lightweight machine learning models optimized for real-time use in distributed assembly environments. Equally important is the development of human-centered AI approaches that combine explainability, ergonomic insights, and adaptive operator interfaces to build trust and improve day-to-day usability. As assembly lines become more interconnected, stronger cybersecurity practices, such as intrusion detection systems and secure-by-design digital architectures, will be essential to protect both physical and digital assets. Additionally, hybrid digital–physical calibration techniques will play a crucial role in narrowing the persistent gap between digital twin simulations and the complex realities of shopfloor operations, ensuring that virtual models better reflect actual manufacturing behavior.

In practice, the adoption of advanced AI technologies such as edge computing and federated learning remains constrained by several industrial realities. Many manufacturers lack unified data architectures, stable sensor infrastructure, and the standardized data governance models required to support decentralized intelligence. Edge deployment further demands reliable networking, hardware redundancy, and on-site system integration capabilities that are not yet mature in many factories. Federated learning introduces additional challenges related to model synchronization, communication overhead, and system interoperability across production sites. Moreover, workforce readiness represents a non-technical barrier, as successful deployment requires skilled personnel capable of managing AI systems, validating model behavior, and interpreting outputs for operational decisions. Without corresponding investments in training, cyber-infrastructure, and organizational alignment, these technologies risk remaining at the pilot stage rather than achieving a scalable industrial impact.

9. Conclusions

This review has consolidated the key developments demonstrating how artificial intelligence and machine learning are reshaping assembly line operations across a wide range of manufacturing environments. By examining algorithmic progress, emerging application areas, dataset availability, and sustainability-oriented practices, the review highlights how AI-driven methods are enhancing efficiency, reliability, flexibility, and environmental performance in smart factory ecosystems. In addition, the mapping between widely used datasets and the industrial sectors they most closely support provides researchers with a practical reference for selecting data suitable for tasks such as assembly optimization, human–machine collaboration, predictive maintenance, quality assurance, and real-time monitoring. This structured perspective helps clarify the landscape of available data sources and makes it easier for future studies to align the choice of datasets with the specific needs of different manufacturing challenges.

Although significant progress has been made, several obstacles continue to limit widespread industrial adoption. These challenges include fragmented and inconsistent data collection practices, the computational burden associated with scaling sophisticated AI models, and persistent discrepancies between digital twin simulations and real shopfloor behavior. Human–AI alignment remains another important concern, as operators must understand and trust AI recommendations for these systems to be used effectively. Moreover, the expanding connectivity of smart manufacturing increases exposure to cybersecurity risks, which can affect production continuity, safety, and data integrity. Collectively, these limitations highlight the broader industrial reality gap, the disconnect between what is technically possible and what is feasible within actual manufacturing environments.

Looking ahead, many promising opportunities can help narrow this gap and accelerate the evolution of AI-enabled assembly systems. A key priority is the development of interoperable data integration frameworks capable of harmonizing diverse sensor streams and enabling timely, accurate decision-making. Equally essential is improving scalability through edge computing, federated learning, and lightweight models designed to operate efficiently in distributed and resource-constrained environments. Future advancements will also depend on more human-centered AI designs that incorporate explainability, ergonomic insights, adaptive interfaces, and user-friendly interaction models to strengthen operator trust and overall system usability. Improving digital twin accuracy through enhanced calibration methods, incorporating sustainability-aware AI strategies to reduce energy use and waste, and deploying secure-by-design architectures will further contribute to building resilient, efficient, and future-ready manufacturing systems. Taken together, these research directions can accelerate the transition toward intelligent, adaptive, and sustainable assembly line operations that reflect the full potential of modern AI and ML technologies.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Elyasi, M.; Thevenin, S.; Cerqueus, A. Use of AI in assembly line design and worker and equipment management: Review and future directions: M. Elyasi et al. Flex. Serv. Manuf. J. 2025, 37, 367–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fordal, J.M.; Schjølberg, P.Ø.; Helgetun, H.; Skjermo, T.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C. Application of sensor data based predictive maintenance and artificial neural networks to enable Industry 4.0. Adv. Manuf. 2023, 11, 248–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotskov, Y.N. Assembly and production line designing, balancing and scheduling with inaccurate data: A survey and perspectives. Algorithms 2023, 16, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakholia, R.; Suárez-Cetrulo, A.L.; Singh, M.; Carbajo, R.S. Advancing Manufacturing Through Artificial Intelligence: Current Landscape, Perspectives, Best Practices, Challenges and Future Direction. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 131621–131637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.D.; Kabir, G.; Mirmohammadsadeghi, S. A digital twin framework development for apparel manufacturing industry. Decis. Anal. J. 2023, 7, 100252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijry, H.; Naqvi, S.M.R.; Javed, K.; Albalawi, O.H.; Olawoyin, R.; Varnier, C.; Zerhouni, N. Real time worker stress prediction in a smart factory assembly line. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 116238–116249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Gao, D.; Tan, L. Smarter and Greener: How Does Intelligent Manufacturing Empower Enterprise’s Green Innovation? Sustainability 2025, 17, 7230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtaza, A.A.; Saher, A.; Zafar, M.H.; Moosavi, S.K.R.; Aftab, M.F.; Sanfilippo, F. Paradigm shift for predictive maintenance and condition monitoring from Industry 4.0 to Industry 5.0: A systematic review, challenges and case study. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 102935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Zhai, X.; Wang, K.; Zhang, K.; Wu, D.; Nazir, A.; Jiang, J.; Liao, W.H. Big data, machine learning, and digital twin assisted additive manufacturing: A review. Mater. Des. 2024, 244, 113086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, K. Interpretable deep learning approach for tool wear monitoring in high-speed milling. Comput. Ind. 2022, 138, 103638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikora, C.G.S. Balancing mixed-model assembly lines for random sequences. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2024, 314, 597–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, T.C.; Sikora, C.G.S.; Michels, A.S.; Magatão, L. An iterative decomposition for asynchronous mixed-model assembly lines: Combining balancing, sequencing, and buffer allocation. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 615–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameri, R.; Hsu, C.C.; Band, S.S. A systematic review of deep learning approaches for surface defect detection in industrial applications. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 130, 107717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, T.P.; Soares, F.A.; Vita, R.; Francisco, R.d.P.; Basto, J.P.; Alcalá, S.G. A systematic literature review of machine learning methods applied to predictive maintenance. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 137, 106024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]