Abstract

While previous research suggests that innovation capability can enhance sustainable operational performance in sustainable supply chain management practices, empirical insights into the mechanisms underlying this relationship remain limited. Drawing on dynamic capability theory, this study investigates how innovation capability influences sustainable operational performance within the context of Alternative Food Networks (AFNs). Utilizing matched survey data and objective performance metrics from 276 fruit and vegetable preserving and specialty food manufacturing firms in China, the study employed Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) with bootstrapping techniques to test the mediating roles of business platforms and community building. The findings reveal that novelty-centered innovation capability has a significant positive effect on sustainable operational performance, with business platforms serving as a partial mediator in this relationship. In contrast, value-centered community building neither directly influences sustainable operational performance nor mediates the effect of innovation capability. Furthermore, the mediating effect of business platforms is found to be stronger than that of community building. This research presents a novel empirical framework that distinguishes the operational effectiveness of digital platforms in social community building within AFNs, providing managers with a strategic roadmap for prioritizing innovation investments to achieve sustainability.

1. Introduction

The agri-food industry has increasingly prioritized a green transition, systemic sustainability, and the transformation of entrenched production and consumption models in response to escalating environmental, social, and governance pressures [1]. While these ambitions are widely acknowledged at the policy and industry levels, their practical realization has been most tangibly manifested in the emergence of Alternative Food Networks (AFNs). AFNs refer to a broad array of initiatives and networks that emphasize the production, distribution, and consumption of organic, locally produced food as a means of fostering more sustainable food systems [1,2]. AFNs have gained recognition as pivotal social and organizational innovations that challenge the dominant industrial food system [3]. Conventional agri-food supply chains are typically characterized by long and fragmented structures, spatial and relational disconnections between producers and consumers, and limited transparency, features that have been widely identified as key drivers of environmental degradation, social inequity, and consumer distrust [4]. In contrast, AFNs emphasize local embeddedness, shortened supply chains, ecological production practices, and relational governance, thereby offering a viable pathway toward more sustainable agri-food systems [5,6,7].

Within this transformation context, innovation capability has emerged as a critical organizational attribute enabling agri-food firms to reconfigure production, distribution, and consumption processes in pursuit of sustainability objectives. Prior research consistently identified innovation capability as a key strategic asset for recognizing new opportunities, enhancing competitiveness, and achieving superior performance in the agri-food sector [8,9]. Unlike traditional views that treat innovation as a purely technical activity, contemporary studies conceptualize innovation capability as a managerial and organizational function that can be strategically developed and deployed to simultaneously generate economic value and social benefits [9].

Empirical evidence further suggests that innovation capability yields disproportionately high performance returns in agri-food systems compared with other industries due to their exposure to environmental volatility, regulatory scrutiny, and shifting consumer preferences ([9]). Consequently, scholars have increasingly called for more granular examinations of the organizational and contextual determinants that shape firms’ innovation outcomes. For example, ref. [7] emphasized the importance of identifying firm-level drivers of innovativeness, while [10] empirically investigated the strategic factors that enable and sustain innovation capability in agri-food firms.

Despite these advances, three critical gaps remain unresolved, particularly within the context of AFNs. First, while AFNs have been extensively examined from sociological and institutional perspectives, existing studies predominantly rely on qualitative approaches that prioritize social values, ethical consumption, and community embeddedness [11]. As a result, there is limited empirical evidence quantifying how innovation capability translates into sustainable operational performance, especially in terms of operational efficiency, waste reduction, and asset utilization. The operational trade-offs faced by AFN firms, therefore, remain poorly understood.

Second, prior innovation studies in agri-food contexts rarely distinguish between heterogeneous transformation pathways through which innovation capability affects performance outcomes. Specifically, the existing literature has not systematically differentiated between digital transactional mechanisms, such as business platforms, and social–relational mechanisms, such as community building, as distinct indirect channels. This omission is particularly consequential for AFNs, where digitalization and social embeddedness coexist yet may exert fundamentally different effects on sustainability outcomes. As noted by [9], firm-level drivers and mechanisms of innovation remain insufficiently explored within specific operational and organizational contexts. Third, although innovation capability is increasingly theorized as a dynamic capability, empirical research has rarely tested this proposition within decentralized, sustainability-oriented supply chains such as AFNs [2]. Consequently, the micro-level mechanisms through which higher-order capabilities shape operational outcomes remain under-theorized and under-validated in AFN settings

Addressing these gaps is theoretically and practically significant. Drawing on dynamic capability theory, innovation capability can be understood as a higher-order capacity that enables firms to sense opportunities purposefully, seize strategic options, and reconfigure resources in response to environmental uncertainty [12,13]. A growing body of research conceptualizes innovation capability as a core dynamic capability precisely because of its role in facilitating continuous adaptation and transformation [9,13,14].

This theoretical lens is particularly salient for AFNs, which operate in complex environments shaped by ecological constraints, fragmented stakeholders, and evolving consumer expectations. Dynamic capability theory helps explain how AFNs cultivate resilience, strategic agility, and long-term competitiveness while addressing intertwined environmental and social imperatives [15,16,17,18]. However, without explicitly identifying the operational mechanisms through which innovation capability is enacted, the explanatory power of this theory remains incomplete.

Among the potential transformation pathways available to AFNs, business platforms and community building have been increasingly recognized as critical mechanisms [4,19]. Business platforms function as digital, market-oriented infrastructures that facilitate producer, consumer coordination through direct delivery, local pick-up, and data-enabled logistics [19]. In contrast, community building emphasizes social cohesion, shared values, trust, and collective identity among stakeholders [20,21]. In the absence of these mechanisms, AFNs risk declining consumer engagement, weakened value alignment, and eventual market marginalization [22]. However, their relative effectiveness in mediating innovation capability and performance relationships remains empirically unexplored.

China provides a particularly compelling empirical context for advancing this research agenda. Unlike Western AFNs [1], which are often characterized by small-scale localism, Chinese AFNs are increasingly embedded within large-scale digital ecosystems [11]. The national Rural Revitalization Strategy explicitly prioritizes the digitalization of agri-food supply chains to reduce post-harvest losses, enhance traceability, and increase rural incomes. As a result, Chinese agri-food firms are at the forefront of experimenting with hybrid AFN models that integrate innovation capability with digital platforms such as live-streaming commerce and platform-based logistics. This policy-driven, high-velocity environment offers a unique opportunity to examine how innovation capability operates under conditions of rapid institutional change, technological integration, and market expansion. It also allows for extending the AFN context beyond its predominantly Western empirical base, thereby enhancing its contextual robustness and external validity. In response to the identified gaps, this study addresses the following research questions:

RQ1: In the context of Alternative Food Networks within the agri-food industry, how does innovation capability influence sustainable operational performance?

RQ2: How do business platforms and community building mediate the relationship between innovation capability and sustainable operational performance in Alternative Food Networks?

This study offers four key contributions to the literature. First, it empirically links innovation capability to sustainable operational performance. It distinguishes the mediating roles of business platforms and community building in platform-based supply chain management perspectives, two transformation mechanisms particularly relevant to the agri-food context. Second, by situating the analysis within AFNs, the study extends the conceptual and empirical understanding of the value of innovation capability in decentralized and sustainability-driven supply chains. Third, by integrating dynamic capability theory, the study advances theoretical insights into how transformation mechanisms channel the effects of innovation capability toward performance outcomes. Specifically, the mediating role of business platforms and community building supports a core proposition of dynamic capability theory: that higher-order capabilities exert an influence on firm outcomes indirectly through shaping operational mechanisms. Fourth, applying the SCOR model offers a standardized, holistic, and process-oriented framework for measuring sustainable operational performance in Chinese alternative food networks by enabling end-to-end analysis, integrating diverse performance attributes (adaptable for sustainability), and facilitating continuous improvement through its hierarchical structure. These findings contribute to innovation capability research by offering a nuanced explanation of how innovation capability can more effectively drive sustainable operational performance.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides a comprehensive review of the relevant literature, develops the theoretical framework and research hypotheses. Section 3 describes the research design, data collection, and methodological approach. Section 4 reports the empirical results, including robustness checks, heterogeneity analysis, and mediating effects. The discussion in Section 5 concludes with key insights, managerial and theoretical implications, and directions for future research. Section 6 presents the conclusions.

2. Theoretical Background and Literature Review

2.1. Innovation Capability and Sustainable Operational Performance

Recent post-pandemic scholarship has reconceptualized AFNs from marginal, niche-based alternatives into digitally enabled and increasingly resilient supply chains [18,23]. This evolution reflects a broader structural shift in agri-food systems, wherein firms are required to continuously reconfigure resources, processes, and stakeholder relationships in order to reconcile economic viability with social and environmental objectives. Within this context, dynamic capabilities have become central to understanding how AFN firms adapt to institutional volatility, technological change, and shifting consumer expectations.

Innovation capability, widely recognized as a core dynamic capability, is commonly conceptualized as a multidimensional construct encompassing product, process, marketing, and organizational innovation [24]. The literature consistently identifies innovation capability as a critical determinant of organizational performance and a primary source of sustained competitive advantage [25]. Empirical studies further demonstrate that innovation capability captures a firm’s ability to generate, assimilate, and apply new knowledge, thereby enabling continuous renewal of offerings, entry into new markets, and improvements in production and managerial systems [26,27]. Such adaptive capacity is particularly salient in agri-food systems, where environmental uncertainty, regulatory pressures, and evolving sustainability expectations necessitate ongoing operational transformation.

In parallel, the concept of sustainable operational performance has gained prominence as an alternative to conventional performance metrics that prioritize short-term financial outcomes. Sustainable operational performance refers to the long-term viability of firms by integrating economic efficiency with environmental stewardship and social responsibility [28]. Although a growing body of empirical research has examined the relationship between innovation capability and operational performance, findings remain fragmented and context-dependent. For example, ref. [29] found that innovation capability directly improves product quality and operational performance while indirectly enhancing financial performance through operational efficiencies. Similarly, ref. [30] argued that strong innovation capability facilitates the alignment of profitability, environmental protection, and social value creation. However, ref. [31] highlighted the absence of a coherent explanation for sector-specific variations in how innovation capabilities are developed and managed. This limitation is especially pronounced in the agri-food sector, where the lack of an integrated research framework constrains the understanding of how internal innovation processes translate into sustainable operational outcomes [9].

Beyond mixed empirical findings, a more fundamental gap concerns the mechanisms through which innovation capability influences sustainable operational performance. While some studies suggest indirect effects, most notably through organizational learning as a mediating capability [32], systematic examinations of such pathways remain limited. Dynamic capability theory posits that higher-order capabilities do not affect firm performance directly; rather, they shape outcomes by orchestrating lower-order operational capabilities and strategic actions [13,33]. Ref. [13] further argues that the deliberate design and deployment of innovation capability enables firms to upgrade complementary functional capabilities, such as new product development and process optimization.

Despite these theoretical advances, empirical research has paid limited attention to how innovation capability is operationalized in decentralized, sustainability-driven supply chains such as AFNs. In particular, the roles of business platforms and community building as mediating mechanisms within platform-based supply chain management have been largely overlooked. This omission is consequential, as AFNs are characterized by decentralized governance structures, localized production systems, and strong social embeddedness, all of which fundamentally reshape how innovation is enacted and diffused. While calls have been made for greater empirical investigation into innovation processes in transitional and emerging economies [34], existing studies have yet to systematically examine how digital, transactional mechanisms and social, relational mechanisms transmit the effects of innovation capability to sustainable operational performance.

Addressing this gap, the present study advances the literature by empirically investigating business platforms and community building as distinct mediating pathways linking innovation capability to sustainable operational performance in AFNs. By doing so, it responds to calls for more context-sensitive and mechanism-based analyses of innovation capability, contributing to a deeper theoretical understanding of how dynamic capabilities are translated into sustainability-oriented operational outcomes.

2.2. Dynamic Capability Theory Perspective on Innovation Capability and Sustainable Operational Performance

A growing body of literature has affirmed the dynamic nature of innovation capability [35,36,37]. For example, ref. [37] offered a critical perspective by conceptualizing innovation capability as a core dynamic capability, one that enables firms to continuously transform knowledge and ideas into novel products, processes, and systems in response to emerging challenges and opportunities. This dynamic orientation positions innovation capability not merely as a static resource but as an adaptive mechanism that drives strategic renewal and operational resilience. In a similar vein, ref. [38] applied dynamic capability theory to examine how innovation capability enhances operational performance through the mediating role of supply chain integration. Collectively, these studies highlight the theoretical relevance of dynamic capability theory in explaining the evolving role of innovation capability in driving firm-level performance outcomes, thereby justifying its integration into the present research framework.

Extant research has demonstrated that dynamic capabilities contribute to firm performance both directly and indirectly. While some studies emphasize their direct influence on performance outcomes [39], others highlight their indirect role in shaping and guiding the development of operational capabilities, which in turn affect performance [40]. For example, ref. [41] found that dynamic capabilities act as enablers of operational capabilities, thereby facilitating improved organizational performance over time. Given their adaptive nature, dynamic capabilities are particularly valuable in environments characterized by rapid and unpredictable change. Consequently, an emerging stream of research has examined the contingent effects of environmental conditions on the efficacy of dynamic capabilities [42,43]. In this regard, ref. [44] suggested that the performance outcomes of dynamic capabilities are amplified under conditions of high environmental uncertainty, as such volatility creates new opportunities that dynamic firms are better positioned to exploit. These findings highlight the importance of contextualizing dynamic capability effects within varying environmental and market conditions.

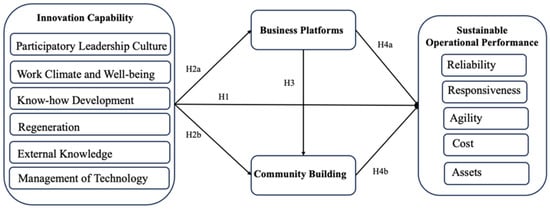

As discussed above, dynamic capability theory provides a robust theoretical foundation for examining the mechanisms through which innovation capability influences sustainable operational performance. Grounded in this perspective, the present study investigated the indirect roles of business platforms and community building in this relationship from platform-based supply chain management perspectives. It is argued that in the context of AFNs, sustainable operational performance among agri-food firms can be enhanced not only through the design of appropriate business models but also through the strategic alignment of innovation capability with specific transformation mechanisms, namely, business platforms and community-building initiatives. By facilitating resource reconfiguration, market responsiveness, and stakeholder engagement, these mechanisms serve as critical pathways through which innovation capabilities are translated into operational sustainability. Furthermore, this study is empirically situated within the context of AFN-participating agri-food firms operating in fruit and vegetable preserving and specialty food manufacturing companies in mainland China, providing context-specific insights into a rapidly evolving and strategically important market. The proposed research framework is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research model.

2.3. Innovation Capability, Business Platforms, Community Building, and Sustainable Operational Performance

Innovation capability is increasingly recognized as a form of dynamic capability that enables firms to adapt, transform, and respond to evolving market conditions [37]. According to dynamic capability theory, such higher-order capabilities do not directly drive performance outcomes, but rather exert influence by shaping and guiding the deployment of operational strategies and capabilities [12,40]. In rapidly changing environments, characterized by shifting customer demands and technological advancements, the ability to develop and adapt products has become a critical operational competence necessary for organizational survival and success [45]. Building on this perspective, ref. [41] highlights that the mechanisms in platform-based supply chain management, such as business platforms and community building, can be viewed as key operational capabilities that enable firms to deliver offerings efficiently and responsively to end-users. Without these mechanisms, firms may struggle to maintain customer engagement and risk losing market relevance or face business failure. Therefore, consistent with the tenets of dynamic capability theory, this study posits that innovation capability guides the development and effective use of business platforms and community-building strategies, which in turn serve as indirect mechanisms that enhance sustainable operational performance.

Innovation capability comprises multiple interrelated dimensions, including participatory leadership culture, work climate and employee well-being, know-how development, regeneration, external knowledge acquisition, and the management of technology [14], all of which are oriented toward creating and capturing value for stakeholders, particularly customers [13]. By enabling firms to bridge knowledge gaps between themselves and their customers, innovation capability plays a pivotal role in driving responsiveness and long-term value creation [46]. It is fundamentally concerned with the acquisition of new knowledge and its strategic conversion into products, services, and processes that meet evolving market needs [37]. Building on this rationale, this study contends that innovation capability serves as a foundational mechanism for achieving sustainable operational performance, particularly by enabling firms to align economic objectives with environmental and social considerations. Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1.

Innovation capability significantly affects sustainable operational performance.

2.3.1. Innovation Capability and Business Platforms and Community Building

Innovation serves as a fundamental mechanism through which organizations develop new products, processes, and systems in response to evolving market demands, technological advancements, and shifts in competitive dynamics [14]. It involves the generation, diffusion, and application of knowledge, culminating in novel or improved offerings and operational methods. Successful innovation can create distinctive capabilities and outcomes that are difficult for competitors to replicate, thus serving as a key source of competitive advantage [47,48]. Moreover, innovation is not limited by organizational scale; rather, it constitutes an ongoing process of organizational renewal aimed at performance optimization [48,49]. The ability to innovate is widely recognized as a critical success factor for long-term growth and profitability, particularly in volatile and competitive environments. Central to this ability is the development of a coherent innovation strategy supported by a shared vision and embedded in organizational routines [50]. Innovation capability, therefore, provides a theoretical lens to understand how firms institutionalize and operationalize innovation activities to capture, absorb, and transform new knowledge into value-generating practices.

This study argues that innovation capability enables the formation and effective use of business platforms and community-building mechanisms in platform-based supply chain management, which represent key strategic and operational responses in the context of AFNs. Business platforms refer to online for-profit web platforms working as marketplaces where consumers can order specific produce from regional companies and then get it delivered to their homes or a pick-up location [51]. Business platforms facilitate market access, supply chain coordination, and digital interaction, while community building strengthens trust, shared identity, and local embeddedness.

Furthermore, this study posits that business platforms may serve as a foundation for community building by fostering interaction, co-creation, and engagement among stakeholders. Community building refers to encouraging actors to form social connections, cohesion, and shared values based on a sense of shared identity [52]. Theoretically, digital platforms provide the virtual space and communication transparency necessary for social capital to form. By reducing information asymmetry, these platforms allow participants to verify shared values and engage in the frequent interactions required to build a collective identity [53]. Based on this reasoning, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2a.

Innovation capability significantly influences the development of business platforms.

H2b.

Innovation capability significantly affects community building.

H3.

Business platforms significantly influence community building.

2.3.2. Business Platforms, Community Building and Sustainable Operational Performance

Driven by the rapid advancement and widespread adoption of next-generation digital technologies, such as the Internet of Things, blockchain, artificial intelligence, and cloud computing, platform-based supply chain management has gained significant traction across industries. In particular, the integration of these technologies has enabled the emergence of more responsive, collaborative, and data-driven supply chain ecosystems. For example, refs. [54,55] emphasized that small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) must develop strategic innovation approaches to effectively navigate the challenges of balancing economic, social, and environmental objectives. Ref. [14] further argued that a well-defined innovation strategy, coupled with a shared vision, is essential for developing innovation capability, especially in platform-based supply chain contexts where agility and integration are critical.

Empirical evidence supports the positive performance implications of platform-based supply chain management. Prior studies have shown that such platforms enable firms to improve delivery reliability [56], manage product assortment under demand uncertainty [22], and enhance multi-channel retail strategies [57]. These mechanisms collectively strengthen firms’ competitive positioning, allowing them to maintain leadership in specific product segments [58,59]. Ref. [19] also highlighted the transformative impact of digital platforms on operational coordination and stakeholder engagement in agri-food systems. Theoretically, business platforms and community building represent two distinct mechanisms for value appropriation in AFNs. Business platforms function as digital infrastructures that reduce transaction costs and information asymmetry through standardized processes [53]. In contrast, community building is rooted in social relational capital, focusing on the cultivation of shared identity and normative commitment among stakeholders [4]. While platforms facilitate the breadth of market reach, community building enhances the depth of stakeholder engagement, suggesting that innovation capability may leverage these pathways differently to achieve sustainability. While community building is often viewed through a social lens, it provides critical operational advantages by fostering high-level trust and shared norms among AFN participants. By aligning consumer expectations with producer capabilities, community building minimizes demand volatility and reduces food waste, directly enhancing the resource efficiency and ‘lean’ objectives of sustainable operational performance [16].

Building on these insights, this study posits that both business platforms and community building contribute positively to sustainable operational performance. Moreover, as transformation mechanisms, they may also serve indirectly by channeling the influence of innovation capability into operational sustainability outcomes. Building on these insights, this study examines the direct influence of the two identified mechanisms on operational outcomes. Business platforms may provide the infrastructure for efficiency, and community building may provide the trust necessary for lean operations. Accordingly, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H4a.

Business platforms significantly influence sustainable operational performance.

H4b.

Community building significantly influences sustainable operational performance.

Building on Dynamic Capability Theory, this study posits that innovation capability does not act in isolation but requires specific seizing mechanisms to impact performance. The study distinguishes between the digital pathway (via business platforms) and the relational pathway (via community building). Furthermore, it explores the sequential link where platforms act as a foundation for the community. The following hypotheses are proposed:

H5a.

Business platforms significantly mediate the relationship between innovation capability and sustainable operational performance.

H5b.

Business platforms significantly mediate the relationship between innovation capability and community building.

Regarding the relational and sequential pathways, this study further proposes that social bonds and platform-driven interactions act as critical bridges for value realization:

H5c.

Community building significantly mediates the relationship between innovation capability and sustainable operational performance.

H5d.

Community building significantly mediates the relationship between business platforms and sustainable operational performance.

3. Method

3.1. Research Setting

Grounded in the extant literature, this study aimed to investigate whether innovation capability enhances sustainable operational performance in AFNs through the indirect roles of business platforms and community building, with empirical evidence drawn from mainland China. While prior studies have predominantly focused on how AFNs contribute to food safety and quality in China, often relying on qualitative methodologies [11], this study adopted a quantitative approach, offering a novel perspective by examining sustainable operational performance in the context of China’s agri-food sector. Specifically, the study focused on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) engaged in fruit and vegetable preserving and specialty food manufacturing within AFNs. In this study, innovation capability was specifically conceptualized as the firm’s ability to integrate new processing technologies and digital management tools to adapt to the rapid shifts in China’s platform-driven agri-food market.

In the context of China’s agri-food sector, business platforms are not monolithic; they manifest as three primary structures: (1) Transaction-centric platforms (e.g., Pinduoduo, JD.com), which provide the digital infrastructure for massive-scale market access; (2) Service-integrated platforms (e.g., Meituan) that coordinate last-mile logistics and cold-chain distribution; and (3) Community-supported digital interfaces (e.g., WeChat-based mini-programs, Douyin/TikTok) that facilitate direct producer-to-consumer interaction. These platforms are structured to reduce information asymmetry through real-time traceability and standardized rating systems. By utilizing these specific structures, Chinese agri-food SMEs can bypass traditional wholesale layers, directly converting innovation in product quality into operational efficiency.

This research context is both timely and strategically relevant. Firms operating in these segments play a pivotal role in reducing post-harvest losses by processing surplus produce, thereby enhancing resource efficiency during operations. Additionally, these companies respond to diverse consumer preferences, ranging from healthy convenience foods to regionally embedded traditional specialties, and contribute significantly to rural economic development by creating employment and increasing smallholder farmers’ incomes. By focusing on these enterprises, the study not only addresses a gap in the innovation-performance literature within AFNs but also provides policy-relevant insights for promoting sustainable and inclusive growth in China’s agri-food supply chains. Specifically, the selection of firms within the fruit and vegetable preserving and specialty food manufacturing subsectors is purposeful. These subsectors are particularly representative of the innovation-sustainability nexus in AFNs for three reasons. First, the high perishability of these products necessitates superior operational efficiency and rapid supply chain coordination to minimize post-harvest waste. Second, specialty food manufacturing is a value-added sector where innovation capability is a primary driver of competitive advantage and social value creation. Finally, these categories represent the most dynamic segments of China’s digital agri-food market, where business platforms and community-building efforts are most prevalent, providing a rich context for testing the proposed mediation mechanisms.

3.2. Sampling and Data Collection

Based on the defined research context, this study focused on fruit and vegetable preserving and specialty food manufacturing companies operating as SMEs in mainland China. Firm-level data were sourced from the Dun & Bradstreet (2024) database, which provides comprehensive insights into the operations and characteristics of companies across industries. From this database, 23,775 manufacturing SMEs were identified. A total of 1173 firms meeting the inclusion criteria were selected as the target sample for survey distribution.

Before full-scale data collection, a preliminary questionnaire was developed based on an extensive review of the relevant literature and subjected to a pre-test with one industry practitioner and three academic experts to ensure content validity and clarity. Feedback from the pre-test informed the final version of the instrument, which consisted of six key sections: (a) firm demographics, (b) innovation capability, (c) business platforms, (d) community building, (e) sustainable operational performance, and (f) respondent profile.

The finalized questionnaire was distributed to top-level executives, including those in R&D, operations, supply chain, and marketing, through both digital (via Wenjuanxing, a widely used online survey platform) and hard-copy formats. To ensure data integrity and prevent multiple responses from the same firm, unique invitations were sent to a single designated respondent per company. The unit of analysis was the firm, and respondents were required to meet three screening criteria to participate: (1) having direct responsibility for operations management, (2) possessing a minimum of three years of relevant work experience, and (3) confirmation that their firm actively participated in an AFN. These criteria were designed to ensure respondent expertise and the relevance of the data to the study’s objectives.

After excluding responses that failed to meet all three screening criteria, a total of 276 valid questionnaires were retained for analysis, resulting in a usable response rate of 23.53%. This response rate is consistent with previous studies employing web-based surveys targeting managerial respondents in organizational research [60,61]. As the data were collected via an online platform, the survey design required respondents to complete all items before submission. Consequently, there were no missing values in the final dataset. Descriptive statistics of the sample demographics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample demographic (N = 276).

3.3. Measurement of Variables

To ensure the validity of the study constructs, scale items were drawn from validated measures used in previous works and adapted to suit the research context (see Appendix A for all items and the literature on which each scale is based). All items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 3 = Moderate, 5 = Strongly Agree).

3.3.1. Innovation Capability

In this study, innovation capability was conceptualized through six distinct components. For a participatory leadership culture, measurement items were developed from [14,62]. The construct of work climate and well-being was measured using scales developed by [14,63]. Know-how development utilized items from [14,64]. The dimension of regeneration was operationalized using scales from [14,63]. For external knowledge acquisition, measurement items were developed from [14,63]. Finally, management of technology was measured using scales from [14,65]. Each scale comprised items (indicator loading see Appendix A).

3.3.2. Business Platforms

For the business platforms construct, measurement items were primarily adapted/adopted from established scales developed by [66,67,68]. Additionally, one item was self-developed based on insights obtained from preliminary interviews. The scale comprised items (indicator loading see Appendix A).

3.3.3. Community Building

For the community building construct, measurement items were adapted/adopted from validated scales developed by [69,70,71,72]. The scale comprised items (indicator loading, see Appendix A).

3.3.4. Sustainable Operational Performance

To evaluate sustainable operational performance, this study adopted metrics from the Supply Chain Operations Reference (SCOR) model, which provides a standardized framework for assessing five key performance attributes: reliability, agility, cost, asset management, and responsiveness. These metrics are instrumental in identifying operational bottlenecks, tracking performance over time, guiding improvement initiatives, and quantifying the efficiency and effectiveness of supply chain actions. Reliability was measured using items developed from [73,74,75]. Agility was assessed through items developed from [73,76]. Cost performance was measured using items developed from [73,77,78]. Asset management utilized measurement items developed from [73,79,80,81]. Responsiveness was evaluated using items developed from [73,82,83]. The measurement items (indicator loading) for each attribute are detailed in Appendix A. This study evaluated the outcomes of firms’ sustainable operational performance over the past three years, from the perspective of their innovation capability.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Reliability and Validity

To ensure the robustness of the construct measures, this study employed a comprehensive set of procedures to evaluate both reliability and validity within the measurement model. As a foundational step in structural equation modeling (SEM), the measurement model evaluation distinguishes between reflective and formative constructs, each requiring distinct analytical approaches due to their conceptual and statistical underpinnings.

For reflective measurement models, internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR). All Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from 0.814 to 0.982, and composite reliability values ranged from 0.877 to 0.985, both exceeding the accepted threshold of 0.70, indicating strong reliability [84]. Convergent validity was confirmed as all average variance extracted (AVE) scores surpassed the recommended cutoff of 0.50 (Table 2). Additionally, the Heterotrait–Monotrait ratio (HTMT) values were all below the conservative threshold of 0.90 (Table 3), further affirming discriminant validity ([85,86]).

Table 2.

Measurement model reliability and convergent validity.

Table 3.

Heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT).

For formative measurement models, indicator multicollinearity was evaluated using variance inflation factors (VIFs). Following established guidelines [87,88], all VIF values ranged from 1.380 to 4.684, well below the threshold of 5, indicating an absence of significant multicollinearity (Table 4). The significance and relevance of formative indicator weights were also assessed to ensure that each indicator contributed meaningfully to its respective construct.

Table 4.

Higher Order Construct Validity—Collinearity Statistics (VIF).

Overall, the measurement model demonstrated strong psychometric properties, providing a reliable and valid foundation for the subsequent structural model analysis. These results support the distinctiveness of the constructs and reinforce the integrity of the model in addressing the study’s research questions [85,89,90].

4.2. Common Method Bias Analysis

Given that the data were collected through self-reported questionnaires, several procedural and statistical remedies were employed to mitigate potential non-response bias and common method variance. First, to reduce ambiguity and improve content clarity, the questionnaire was pre-tested by 19 experts, and the measurement items were carefully refined based on their feedback. In addition, the design strategically separated the measurement of independent and dependent variables across different sections of the instrument, thereby reducing the likelihood of common method bias due to item proximity.

Second, respondent anonymity was strictly maintained by removing all identifiable information, thus minimizing social desirability bias and encouraging more honest responses. Third, to test for non-response bias, a t-test comparison between early and late respondents was conducted, following the approach of [91]. The analysis revealed no statistically significant differences between the two groups, suggesting that non-response bias was unlikely to affect the results.

Finally, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted to assess the extent of common method variance [92,93]. The results from an unrotated exploratory factor analysis indicated that no single factor accounted for the majority of the variance, confirming that common method bias was not a serious concern in this study.

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

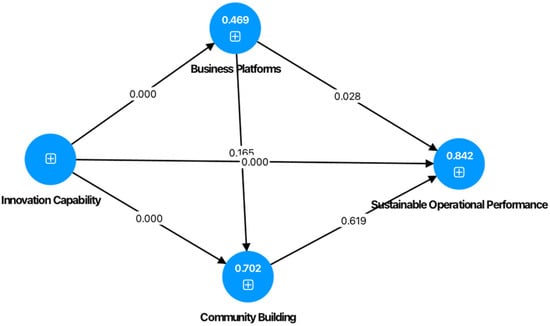

To assess the statistical significance of the hypothesized relationships, a bootstrapping procedure was conducted using SmartPLS version 4. This non-parametric resampling technique was performed with 5000 subsamples, applying a two-tailed significance test at the 5% level, as recommended by [92]. The bootstrapping approach allows for the estimation of standard errors and the generation of t-statistics without requiring assumptions about the underlying data distribution. Following the guidelines provided by [86], the critical t-values for a two-tailed test are 2.58 (p < 0.01), 1.96 (p < 0.05), and 1.645 (p < 0.10). Figure 2 illustrates the structural model results, including the path coefficients and their associated significance levels.

Figure 2.

Assessment of the structural model results. Note: p < 0.05, t-value > 1.96, All tests are two-tailed.

As presented in Table 5, the estimated path coefficients (β) ranged from −0.076 to 0.888. Coefficients closer to 1 indicate strong positive relationships, whereas values below zero reflect significant negative associations. Conversely, coefficients near zero typically suggest weak or negligible effects [86]. To assess the statistical significance of each hypothesized path, the conventional threshold was applied: a t-value greater than 1.96 and a p-value below 0.05 indicate statistical significance at the 5% level [94]. These results provide empirical support for the strength and direction of the proposed relationships within the structural model.

Table 5.

Path coefficients, T-statistics, and significance level (direct effects).

As shown in Table 5, the analysis of direct effects provides empirical support for several of the hypothesized relationships. H1 is supported: innovation capability demonstrated a significant positive direct effect on sustainable operational performance (β = 0.801, p < 0.05, t > 1.96). H2a (β = 0.685) and H2b (β = 0.888) are also supported, indicating that innovation capability positively and significantly influences both business platforms and community building (p < 0.05, t > 1.96 for both paths). To further address the path coefficient between innovation capability and community building being relatively high (β = 0.888, p < 0.001), the structural model was assessed for potential bias. The VIF value for the path from innovation capability to community building was 1.928, well below the threshold of 3.3, and HTMT values were all below 0.90. These results confirm that the constructs represent distinct theoretical dimensions and that multicollinearity does not bias the path estimates, despite their strong statistical correlation. However, H3 is not supported, as business platforms do not exert a statistically significant direct effect on community building. Furthermore, H4a is supported, with business platforms showing a significant positive direct effect on sustainable operational performance (β = 0.110, p < 0.05, t > 1.96). In contrast, H4b is not supported, as community building did not demonstrate a significant direct effect on sustainable operational performance. These findings highlight the pivotal role of innovation capability and business platforms in directly enhancing sustainable operational performance. Conversely, community building does not appear to play a direct role in influencing performance outcomes within the tested model. This suggests that in the high-velocity Chinese agri-food market, the transactional efficiency provided by digital platforms may outweigh the operational impact of social-relational bonds, or that the benefits of community building require a longer temporal horizon to manifest in objective performance metrics.

As shown in Table 6, the analysis of indirect effects provides partial support for the hypothesized mediation relationships. Specifically, H5a is supported: innovation capability exerted a significant positive indirect effect on sustainable operational performance through the mediation of business platforms (β = 0.075, p < 0.05, t > 1.96), indicating that business platforms play a substantive mediating role in this relationship. In contrast, H5b is not supported, as innovation capability did not have a statistically significant indirect effect on community building via business platforms. Similarly, H5c is not supported, as the indirect effect of innovation capability on sustainable operational performance through community building failed to reach statistical significance. Finally, H5d is also not supported, suggesting that business platforms did not significantly influence sustainable operational performance through the mediation of community building. A notable finding of this study is the non-significant impact of value-centered community building on sustainable operational performance (H4b) and its failure to mediate the innovation-performance link (H5c, H5d). This suggests a decoupling between social-relational efforts and technical operational metrics in the Chinese AFN context. Unlike Western AFNs, where community trust is a primary driver of success, Chinese agri-food firms appear to prioritize the transactional efficiency of digital platforms over social-relational capital to achieve sustainability. This may be due to the high-velocity nature of the Chinese market, where digital infrastructure provides immediate advantages in waste reduction and market access that social community building cannot yet match in scale or speed. In contrast, H5b is not supported, as innovation capability does not have a statistically significant indirect effect on community building via business platforms, suggesting that digital infrastructures in this context are currently optimized for market transactions rather than social network cultivation.

Table 6.

Indirect Effects (Mediation).

The predictive power of the structural model was evaluated using multiple criteria. In line with [95], the model’s explanatory strength was assessed through the coefficient of determination (R2), which reflects the proportion of variance explained in each endogenous construct. As reported in Table 7, all R2 values exceeded the threshold of 0.20, indicating an acceptable level of explanatory power [96]. To further assess the model’s predictive relevance, Stone–Geisser’s Q2 statistic was calculated using the blindfolding procedure. According to [96], Q2 values greater than zero demonstrate that the model possesses predictive relevance for a given construct. The results show that Q2 values for all three dependent variables were above zero, thereby confirming the model’s predictive validity (see Table 7).

Table 7.

Relevance of the predictive model.

5. Discussion

Although prior studies have emphasized the relevance of investigating the relationship between innovation capability and operational performance, empirical research exploring the underlying mediating mechanisms and contextual conditions remains limited. Drawing on dynamic capability theory, this study posits that innovation capability, as a higher-order dynamic capability, affects sustainable operational performance through its influence on business platforms and community building in platform-based supply chain management, conceptualized as operational-level capabilities and strategic mechanisms.

Based on a sample of fruit and vegetable preserving and specialty food manufacturing firms in mainland China, the empirical findings offer several important insights. First, innovation capability exerted both a significant direct effect on business platforms and sustainable operational performance and an indirect effect on performance via business platforms. However, innovation capability did not significantly influence sustainable operational performance indirectly through community building, although it did exert a significant direct effect on it.

Three unexpected yet theoretically meaningful findings emerged from the analysis. First, business platforms do not enhance community building; rather, they appear to negatively affect it. This finding, while counterintuitive, aligns with emerging critical perspectives [97] that suggest that phantomization driven by profit maximization, algorithmic standardization, and monopolistic control may erode the core social fabric of AFNs. The unexpected tension between business platforms and community building (H3) warrants a deeper theoretical reflection. The highly standardized and automated nature of digital business platforms in China’s context may prioritize transactional speed at the expense of relational depth. As platforms formalize interactions through algorithmic matching and standardized ratings, they may inadvertently reduce the organic social capital and informal reciprocity that are the hallmarks of traditional community building [7]. This suggests that for Chinese agri-food firms, digital infrastructure may act as a substitute for, rather than a complement to, communal social bonds in the short-term. Specifically, platforms may undermine trust, local diversity, and community autonomy by prioritizing transactional efficiency over relational cohesion and equitable value distribution between producers and consumers.

Second, community building does not significantly improve sustainable operational performance, nor does it mediate the effect of innovation capability on performance. A plausible explanation is that while community building strengthens relational ties and local trust, core tenets of AFNs, it often lacks the technical integration, professional expertise, and market-oriented structures needed to translate social capital into tangible operational gains [6]. This limitation hampers its ability to address complex supply chain challenges such as efficiency, scalability, and value-chain optimization, which are essential for achieving sustainable operational outcomes.

Third and most notably, business platforms demonstrate a stronger effect on sustainable operational performance than community building, which challenges initial expectations. This result suggests that platform-based supply chain management mechanisms, through centralized supply chain coordination, digital infrastructure (e.g., traceability systems, logistics optimization), and broader market access, are more effective at addressing key operational inefficiencies in fragmented AFNs [3]. These include reducing transaction costs, improving resource allocation, and expanding market reach, thereby delivering measurable performance benefits such as cost efficiency, reduced environmental footprint, and enhanced supply chain resilience. In contrast, the relational focus of community building, while socially valuable, lacks the scale and technical capacity to drive systematic operational improvement.

This study contributes to DCT by identifying the specific seizing and reconfiguring mechanisms through which innovation capability is transformed into sustainable value. Within the DCT framework, innovation capability acts as the sensing mechanism, allowing firms to identify ecological and market shifts [13]. However, the findings clarify that business platforms serve as the primary seizing mechanism, providing the digital configuration necessary to capture value from these innovations. By demonstrating that sustainability outcomes depend more on platform-based reconfiguration than on social-relational capital, this study extends DCT into the digital agri-food context, proposing that in high-velocity environments, digital agility may be a more critical dynamic capability for sustainability than social embeddedness.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This study generated four key theoretical implications that contribute to the literature on innovation capability, dynamic capability theory, and platform-based supply chain management in the agri-food sector. First, this study addresses a previously underexplored yet critical issue: the impact of innovation capability on sustainable operational performance. While the extant literature has predominantly emphasized the relationship between innovation capability and market or financial performance [98,99,100,101], fewer empirical efforts have investigated how innovation capability drives sustainability-related operational outcomes. This study advances the AFN literature by shifting the focus from the traditional relational paradigm toward a hybrid-digital perspective [102] While prior research has conceptualized AFNs primarily as spaces of social resistance and local embeddedness, the findings provide empirical evidence that in emerging economies like China, AFNs are evolving into digitally enabled resilient supply chains. By demonstrating the dominance of business platforms over community building in driving operational performance, this study challenges the romanticized view of AFNs as purely social constructs and highlights the necessity of digital infrastructure for their economic survival [18]. Despite being widely recognized as a cornerstone in technology and innovation management [103,104,105,106], the operational implications of innovation capability, particularly in sustainability contexts of AFNs, remain insufficiently understood. By empirically examining this relationship and elucidating the underlying mediating mechanisms through business platforms and community building, this study deepens the understanding of how innovation capability can enhance sustainable operational performance.

Second, this study contributes to the literature by contextualizing innovation capability within AFNs in the agri-food sector, specifically among fruit and vegetable preserving and specialty food manufacturing firms in mainland China. Prior research has primarily examined innovation capability in the context of e-business [107] and manufacturing firms [108,109]. This research offers a significant theoretical advancement by explicitly positioning the contrast between business platforms and community building as a strategic trade-off. This study introduces a nuanced understanding of how digital seizing mechanisms can potentially crowd out social reconfiguring mechanisms. This extends the current understanding of the phantomization of food systems by revealing that digital standardization, while accelerating operational sustainability and waste reduction, may inadvertently erode the organic social capital typically associated with AFNs. This efficiency-cohesion paradox provides a new theoretical lens for future researchers to examine the sustainability of AFNs in high-velocity digital environments. However, the agri-food sector, characterized by seasonality, perishability, and complex actor interdependencies, poses unique challenges and opportunities for innovation capability deployment. Furthermore, the rise of platform-based supply chain digitalization and networked coordination mechanisms underscores the increasing relevance of business platforms and community building in reconfiguring operational strategies. By focusing on this underrepresented context, the study responds to recent scholarly calls for more fine-grained investigations of innovation capability within agri-food systems and contributes to understanding its role in advancing rural revitalization, food system sustainability, and localized value creation.

Third, the study enriches dynamic capability theory by clarifying the role of business platforms as mediators in the innovation performance link. Specifically, the results support the proposition that innovation capability (a dynamic capability) affects sustainable operational performance through the development of business platforms (operational capabilities or strategic mechanisms). This aligns with the dynamic capability view that higher-order capabilities influence firm performance by shaping and guiding lower-order operational routines [12,40]. In contrast to prior studies that emphasize organizational learning as a mediator [14], this study empirically validated business platforms as a more direct and impactful mediating mechanism. Notably, the indirect path via business platforms is stronger than the corresponding path through community building. These findings advance the theoretical understanding of how innovation capability can translate into measurable sustainability outcomes, particularly in digitally enabled, platform-centric supply chains [110].

Fourth, this study introduces nuance into existing understandings of community building by revealing its unexpected role as a non-significant, and in some cases, detrimental, mediator in the innovation performance relationship. While prior research often regards community building as a facilitator of innovation performance [111], the findings of this study show that community building does not mediate the innovation–sustainable performance link and may even dilute the operational benefits of innovation capability. A potential interpretation is that while community building enhances social cohesion and shared identity within AFNs, it may lack the technological sophistication, managerial discipline, and scalability needed to deliver measurable operational gains. This finding supports the contextual sensitivity of dynamic capabilities [43], emphasizing that not all capabilities or strategies are universally effective across different environments. In doing so, this study advances theoretical discourse by demonstrating that the utility of innovation-related mechanisms such as community building is contingent on the broader supply chain structure, technological enablers, and performance objectives.

5.2. Managerial Implications

The findings offer actionable guidance for managers and strategic decision-makers in agri-food firms operating within AFNs. First, managers should prioritize investment in innovation capability as a strategic sensing tool to navigate environmental uncertainty. The results affirm that this capability provides the adaptive flexibility needed for long-term resilience. Specifically, for firms in fruit and vegetable preserving, this capability should be directed toward digitalizing the supply chain. By adopting business platforms that offer real-time data on shelf-life and logistics, managers can significantly enhance sustainable operational performance by reducing post-harvest losses.

Second, the study suggests a strategic shift in how managers view community engagement. Since community building showed a non-significant direct effect on performance, specialty food manufacturers should avoid over-investing in traditional offline social activities that do not scale. Instead, they should focus on digitizing the community by integrating social trust mechanisms, such as digital storytelling or provenance verification, directly into business platforms. This ensures that the trust built with consumers facilitates faster transactions and lower marketing costs, translating social capital into tangible operational gains.

Third, this study reveals that business platforms serve as the primary seizing mechanism through which innovation capability improves performance. Platforms facilitate centralized integration, digital traceability, and scalable market access. For example, Chinese agri-food producers leveraging digital platforms can directly connect with consumers and streamline logistics. Managers are thus encouraged to invest in platform capabilities that translate novel ideas into concrete operational improvements.

Finally, managers should adopt a cautious approach to phantomization. While platforms provide the necessary mechanism for growth, managers must ensure that the standardization required by these platforms does not crowd out the firm’s unique local identity. Rather than focusing on the macro-risks of platform monopolies, managers should address the practical risk of brand commoditization. Successful managers will be those who use platforms for operational scale while maintaining a distinct relational presence to prevent brand dilution in a crowded digital marketplace. In sum, innovation capability should be viewed as a strategic enabler of adaptive, platform-integrated, and socially informed supply chain performance.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Despite its contributions, this study is subject to several limitations that provide valuable avenues for future research. First, the empirical analysis was confined to fruit and vegetable preserving and specialty food manufacturing firms operating within AFNs in mainland China. While this focus allowed for contextual depth, it limits the generalizability of the findings across different institutional, economic, and regulatory environments. Future research should consider cross-country comparative studies or expand the scope to other agri-food subsectors to assess the robustness of the proposed framework across varied contexts and institutional settings.

Second, the study conceptualized innovation capability as a holistic construct, without disaggregating its six core subdimensions, namely, participatory leadership culture, work climate and well-being, know-how development, regeneration, external knowledge, and management of technology. This decision was made to preserve the synergistic nature through which these components interactively shape a firm’s innovation capacity. However, future studies may benefit from a disaggregated approach to investigate how specific combinations or complementarities (e.g., complementarity-centred vs. lock-in-centred innovation capabilities) differentially affect sustainable operational performance, particularly within platform-based supply chain environments. Such analysis could deepen the understanding of how firms can tailor innovation strategies to enhance intelligent decision-making, agility, resource orchestration, and risk management [112,113].

Third, sustainable operational performance in this study was evaluated using the Supply Chain Operations Reference (SCOR) model. While SCOR provides a widely accepted and structured framework across five performance dimensions: reliability, responsiveness, agility, cost, and asset management, it may underrepresent the intangible, relational, and socio-environmental factors, particularly salient in AFNs and smallholder-based supply systems. Moreover, data availability and granularity, especially among rural producers, present empirical challenges. Future research could extend or adapt the SCOR model by incorporating qualitative insights, integrating social sustainability metrics, and aligning evaluation tools with the specific policy context of rural revitalization initiatives in China. Longitudinal and comparative studies across diverse AFN types would also enhance the theoretical and practical understanding.

Finally, while this study focused on the mediating roles of business platforms and community building in platform-based supply chain management, it left other potential mediators and moderators unexplored. Future research could examine alternative organizational mechanisms (e.g., open innovation practices, collaborative governance models, cooperative-led initiatives, or digital innovation hubs) and boundary conditions (e.g., platform governance models, policy incentives, environmental dynamism) that may shape the relationship between innovation capability and sustainable performance outcomes. Such extensions would further enrich the explanatory power of the dynamic capability perspective in platform-based agri-food supply chain management.

6. Conclusions

This study investigated how innovation capability enhances sustainable operational performance in China’s emerging AFNs. By examining the mediating roles of business platforms and community building, the research clarifies the mechanisms that drive sustainability in high-velocity digital markets. The primary theoretical contribution lies in identifying the efficiency-cohesion paradox. While traditional AFN literature by the qualitative method emphasizes social capital as the primary driver of success, this study by the quantitative method demonstrates that in the context of China’s digital development, business platforms act as the dominant seizing mechanism for sustainability. This study advances Dynamic Capability Theory by showing that digital agility, the ability to reconfigure supply chains through platforms, is more impactful for operational performance than social embeddedness. This suggests a fundamental shift in AFN context, moving from a purely relational paradigm to a hybrid-digital model where transactional efficiency is the prerequisite for social survival.

For managers and policymakers, this study reveals that digital infrastructure is no longer optional for sustainable agri-food systems. Specifically, for firms in the fruit and vegetable and specialty food sectors, the results suggest that operational sustainability, e.g., saving cost and resource efficiency, is best achieved through business platform-based supply chain ecosystems rather than localized community efforts alone. Managers are encouraged to digitize their social trust, embedding their brand stories directly into platform interfaces to bridge the gap between relational values and transactional performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.W., X.Y. and S.Z.; Methodology, X.W., X.Y. and S.Z.; Software, X.W., X.Y. and S.Z.; Validation, X.W.; Formal analysis, X.W. and X.Y.; Investigation, X.W.; Resources, X.W.; Data curation, X.W. and X.Y.; Writing—original draft, X.W.; Writing—review & editing, S.Z. and A.R.; Visualization, X.W. and X.Y.; Supervision, S.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Universiti Malaya Research Ethics Committee (protocol code UM.TNC2/UMREC_3608 and date of approval 12 July 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Survey Items and Confirmatory Factor Analysis Results

| Constructs and Items | Standardized Loading | |

|---|---|---|

| Innovation Capability Participatory Leadership Culture | ||

| Items | My firm ________ | |

| PCL1 | does not allow subordinates to participate in the product development process. ® | 0.950 |

| PCL2 | adopts the employees’ opinions, which could help the organization shape the innovation direction. | 0.954 |

| PCL3 | trusts that the leadership style is not merely instructive but open to collaboration. | 0.947 |

| PCL4 | considers that the leader shows support for critical ideas that aim to reform the organization. | 0.939 |

| Work Climate and Well-being (WCW) | ||

| Items | My firm________ | |

| WCW1 | trusts that integrity in working is significant for the organization. | 0.826 |

| WCW2 | considers competency in working is critical for the organization. | 0.908 |

| WCW3 | accept as true that reliability in working is not important for the organization. ® | 0.905 |

| WCW4 | have faith in that loyalty with work is significant for the organization. | 0.886 |

| Know-how Development (KHD) | ||

| Items | My firm ____________ | |

| KHD1 | thinks that the organization provides training to improve employees’ skills to understand customer’s situations. | 0.96 |

| KHD2 | gives training to improve employees’ skills to understand the emergence of new technologies. | 0.921 |

| KHD3 | never provides supplementary training to maximize employee potential. ® | 0.915 |

| KHD4 | accept as true that the organization defines success in terms of having the most innovative products and services. | 0.955 |

| KHD5 | is not a very dynamic and enterprising place. ® | 0.959 |

| Regeneration (REG) | ||

| Items | My firm ____________ | |

| REG1 | regularly assesses the effectiveness of business initiatives. | 0.846 |

| REG2 | implements changes based on the prior evaluation. | 0.818 |

| REG3 | believes that the manager never treats mistakes as a learning opportunity for employees. ® | 0.824 |

| REG4 | perceives innovation as essential. | 0.836 |

| External Knowledge (EK) | ||

| Items | My firm ____________ | |

| EK1 | collaborates with external parties. | 0.785 |

| EK2 | maintains a bad relationship with a partner with other organizations. ® | 0.767 |

| EK3 | has a good relationship with customers. | 0.743 |

| EK4 | has a bad relationship with industrial associations. ® | 0.178 |

| EK5 | has a good relationship with competitors. | 0.872 |

| Management of Technology (MT) | ||

| Items | My firm ____________ | |

| MT1 | anticipates technological needs in the future based on the development of products and market trends. | 0.975 |

| MT2 | conducts an assessment of technological needs. | 0.948 |

| MT3 | cannot create items with unique characteristics. ® | 0.943 |

| MT4 | believes that the rate at which new products are developed is adequate and competitive. | 0.936 |

| MT5 | is slower in adopting the most recent technological advancements. ® | 0.952 |

| Business Platform (BP) | ||

| Items | My firm____________ | |

| BP1 | tries to provide an online transaction process that has been re-engineered to support order manage-ment. | 0.977 |

| BP2 | is an organization where marketing policies are not shared online with consumers to support pro-motion policy management. ® | 0.944 |

| BP3 | is an organization that can provide order catalogs, which are shared online with consumers to support pricing and product launches. | 0.960 |

| BP4 | is an organization whose production schedules are not shared online with consumers to support order fulfilment. ® | 0.952 |

| BP5 | provides various online communication services to support interaction with customers. | 0.948 |

| Community Building (CB) | ||

| Items | The community building in my company is attained when ___________ | |

| CB1 | some characteristics of our company’s brand come to consumers’ minds quickly. | 0.938 |

| CB2 | our consumers would not recommend the product or service to others. ® | 0.879 |

| CB3 | in comparison to alternative brands, our products have consistent quality. | 0.930 |

| CB4 | consumers spoke of our company much more frequently than any other manufacturing company in the food industry. | 0.936 |

| CB5 | consumers are proud to say to others that they are our company’s customers. | 0.963 |

| Sustainable Operational Performance Reliability (REL) | ||

| Items | My company’s operations reliability for __________ | |

| REL1 | order entry accuracy has increased. | 0.957 |

| REL2 | forecast accuracy (demand, order, sales) has increased | 0.902 |

| REL3 | stock accuracy never increased ® | 0.927 |

| REL4 | warehouse efficiency has increased | 0.950 |

| REL5 | delivery accuracy (location and quantity) never increased. ® | 0.954 |

| Agility (AGI) | ||

| Items | My company’s operations agility to ________________ | |

| AGI1 | adapt to the new order in case the order deviates from the forecast in parallel with the changing demand (order flexibility) has increased. | 0.883 |

| AGI2 | deliver such as diversification of transport modes (transport flexibility) never increased. ® | 0.846 |

| AGI3 | align information systems architectures and systems with the organization’s changing information needs while responding to changing customer demand (information system flexibility) has increased. | 0.864 |

| AGI4 | detect and predict market changes (market flexibility) has increased. | 0.873 |

| AGI5 | deliver products to customers on time and respond quickly to changes in delivery requirements were not achieved. ® | 0.907 |

| Cost (COS) | ||

| Items | My company’s operations costs for ________________ | |

| COS1 | storage costs have been reduced. | 0.822 |

| COS2 | transport costs have increased. ® | 0.806 |

| COS3 | cost of goods sold (COGS) never decreased. ® | 0.849 |

| COS4 | reverse logistics costs have decreased. | 0.756 |

| COS5 | intangible costs (quality costs, product adaptation, performance costs coordination costs, etc.) never decreased. ® | 0.797 |

| Assets (ASS) | ||

| Items | My company’s operations efficiency for ____________ | |

| ASS1 | return on working capital has increased. | 0.966 |

| ASS2 | the cash conversion cycle (CCC) has increased. ® | 0.938 |

| ASS3 | supply chain revenue has increased. | 0.949 |

| ASS4 | the rate of recycling or reuse of materials has increased. | 0.928 |

| ASS5 | waste never decreased in the supply chain network. ® | 0.939 |

| Responsiveness (RES) | ||

| Items | My company’s operations responsiveness for _______. | |

| RES1 | warehouse cycle times (average receiving, placing, picking, preparing, and delivering) have decreased. | 0.871 |

| RES2 | transportation cycle time never decreased. ® | 0.898 |

| RES3 | production cycle time has decreased. | 0.917 |

| RES4 | order fulfillment cycle time has decreased. | 0.894 |

| RES5 | supply cycle time never decreased. ® | 0.908 |

References

- Si, Z.; Schumilas, T.; Scott, S. Characterizing alternative food networks in China. Agric. Hum. Values 2015, 32, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwart, T.A.; Wertheim-Heck, S.C. Retailing local food through supermarkets: Cases from Belgium and the Netherlands. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 300, 126948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Si, Z.; Miao, Y.; Zhou, L. How does the concept of Guanxi-circle contribute to community building in alternative food networks? Six case studies from China. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoll, F.; Specht, K.; Siebert, R. Alternative= transformative? Investigating drivers of transformation in alternative food networks in Germany. Sociol. Rural. 2021, 61, 638–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkley, C. The small world of the alternative food network. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulick, R. More time in the kitchen, less time on the streets: The micropolitics of cultivating an ethic of care in alternative food networks. Local Environ. 2019, 24, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belda-Miquel, S. Expanding well-being by participating in grassroots innovations: Using the capability approach to explore the interest of alternative food networks for community social services. Br. J. Soc. Work. 2022, 52, 3618–3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capitanio, F.; Coppola, A.; Pascucci, S. Indications for drivers of innovation in the food sector. Br. Food J. 2009, 111, 820–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafetzopoulos, D.; Vouzas, F.; Skalkos, D. Developing and validating an innovation drivers’ measurement instrument in the agri-food sector. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 1199–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafetzopoulos, D.; Skalkos, D. An audit of innovation drivers: Some empirical findings in Greek agri-food firms. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2019, 22, 361–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, W.; Suhaiza, Z. Alternative food networks in supply Chains: A Biblio-metric analysis using RStudio and VOSViewer (1989–2024). Waste Manag. Bull. 2025, 3, 100215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Business models and dynamic capabilities. Long Range Plan. 2018, 51, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]