1. Introduction

Digital–intelligent transformation has become a key initiative for promoting the high-quality development of the manufacturing sector. In this process, digitalization serves as the foundation, while intelligent upgrading is the ultimate goal. Together, they advance the industry toward greater sophistication, intelligence, and sustainability. At the core of this transformation lies the innovative application of digital technologies, enabling the integration of next-generation information technologies with advanced manufacturing and enhancing intelligence in all aspects of enterprise operations, including design, production, management, and services.

In recent years, the Chinese government has issued a series of policies to accelerate digital–intelligent transformation in the manufacturing industry. In May 2015, the State Council released Made in China 2025, which, for the first time, proposed the strategic goals for upgrading China’s manufacturing sector; promoting digital transformation; and encouraging the deep integration of technologies such as the industrial internet, cloud computing, big data, and artificial intelligence with manufacturing. On 28 December 2021, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT), together with seven other ministries, jointly issued the 14th Five-Year Plan for the Development of Intelligent Manufacturing, which outlined the development goals, key tasks, and safeguards for intelligent manufacturing during the plan period.

Many Chinese firms have actively responded to national initiatives by implementing intelligent or digital transformation measures to improve production efficiency and product quality. For example, FAW Jiefang’s J7 Intelligent Factory, with an annual capacity of 50,000 heavy-duty trucks, can produce 1 truck every 270 s while reducing per-unit comprehensive costs by 28.3 percent and significantly increasing yield rates after transformation. Likewise, Yuhong Textile Co. introduced advanced equipment, such as roving, spinning, and winding systems, achieving full or partial automation of all processes and greatly reducing labor demand while improving product quality and economic performance.

Nonetheless, many enterprises still face considerable challenges in implementing digital–intelligent transformation, including long project cycles; bottlenecks in connecting upstream and downstream supply chains; and shortages in capital, technology, and guidance. Total factor productivity is a key indicator for measuring a firm’s overall production efficiency, and it directly reflects its comprehensive capabilities in resource allocation, technology application, and management optimization, thereby serving as a critical manifestation of production efficiency improvement. However, efficiency gains are not the only consequence of this transformation. As digital infrastructure matures and intelligent algorithms become widespread, firms acquire unprecedented governance capabilities for optimizing energy use, recycling resources, and controlling emissions, thereby opening new technological pathways toward sustainability objectives. Therefore, investigating whether and how digital–intelligent transformation enhances TFP is of paramount importance. It provides both theoretical and practical insights for enterprises seeking to optimize their production efficiency.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Digital–Intelligent Transformation Measures

Digital–intelligent transformation exerts multidimensional positive effects on enterprise development and socio-economic restructuring. Research shows that digitally intelligent enterprises demonstrate remarkable achievements in reducing production costs, enhancing product quality, and strengthening innovation capabilities [

1]. Through the synergistic interaction of digital–intelligent technologies, organizational structures, and environmental factors, such a transformation effectively promotes energy efficiency improvements and green emission optimization in energy-intensive enterprises [

2]. At the same time, digital–intelligent transformation has a positive impact on corporate performance, and this impact is moderated by process characteristics such as transformation speed, scope, and rhythm [

3].

At a more macro-level, urban digital–intelligent transformation can facilitate corporate green innovation through multiple pathways, such as advancing digital transformation, increasing firms’ R&D investment, and promoting information sharing [

4]. Key supporting factors, including innovation infrastructure, industrial environment, and data elements, can further enhance the capacity of the Yangtze River Delta’s manufacturing sector to supply core technologies within the framework of intelligent upgrading, digital transformation, and network interconnection. In addition, intelligent and digital transformation can promote domestic circulation, as well as the dual circulation between domestic and international markets, thereby reducing transaction costs [

5,

6].

From a research direction perspective, current work tends to treat intelligent transformation or digital transformation in a relatively single-focused manner. In terms of digital transformation, studies have mainly focused on the impact of corporate digitization on firm outcomes and the determinants of digital transformation. The degree of digital clustering is significantly positively related to corporate digital transformation, and corporate digital transformation exhibits urban peer effects [

7,

8]. Small-, medium-, and micro-sized enterprises initially experience negative effects from digitalization, but these adverse impacts gradually attenuate over time [

9]. Specifically, digital transformation yields positive impacts across multiple dimensions: it can significantly improve capital allocation efficiency, enhance ESG performance, and boost corporate performance [

10,

11,

12]. When procuring goods and services, small- and medium-sized enterprises that adopt digital technologies achieve significant benefits [

13]. In terms of intelligent transformation, studies have mainly focused on the effects of firm intelligent transformation on the firms themselves. Industrial intelligent transformation shows pronounced regional differences in the direct, indirect, and total employment effects across workers with different skill levels and genders [

14]. Industrial intelligent transformation also plays a positive role in promoting low-carbon economic development, enhancing total factor productivity in the economy, strengthening industrial competitiveness, and improve the long-run average profit [

15,

16,

17,

18]. Moreover, urban intelligent transformation tends to widen wage disparities between workers with different skill levels [

19].

2.2. Internal Incentives and External Pressures

Internal incentives and external pressures have been proven to be the core driving forces behind firms’ green behaviors, jointly promoting green innovation, carbon emission reduction, and improvements in sustainable development performance. External pressures are primarily driven by policy regulation. The Environmental Protection Tax encourages green innovation and carbon reduction by exerting regulatory pressure on firms; the Carbon Emissions Trading Scheme enhances motivation for green innovation through market-based mechanisms; and green fiscal policies improve innovation performance through both reverse driving effects and resource compensation effects [

20,

21,

22]. Moreover, within command-based policies, administrative penalties have a stronger incentive effect than environmental impact assessment approvals; among incentive-based policies, investments in pollution control exert a significant positive impact, while environmental taxes exhibit an “inverted U-shaped” effect. Additionally, market pressures and international regulations complement these mechanisms by imposing constraints through supply chain collaboration [

23].

Internal incentives depend on the synergy of resources, capabilities, and governance mechanisms. A firm’s resource base provides material support for green initiatives; green dynamic capabilities and internal environmental awareness facilitate the transformation of external pressures into tangible performance outcomes; and governance mechanisms such as executive compensation optimization and internal control improvements enhance the effectiveness of incentives—although total asset turnover shows an inhibitory effect [

24]. Existing research generally supports the “external guidance–internal transformation” logic, and the synergistic effects of internal and external factors exhibit heterogeneity across firms with different characteristics and industries. These findings provide micro-level references for policy formulation and corporate strategic optimization aimed at fostering sustainable and green development [

25].

Existing studies on firms’ digital and intelligent transformation have generated substantial theoretical and empirical insights, demonstrating its multidimensional impacts on innovation, energy efficiency, and employment structure, as well as underscoring the complementary roles of internal incentives and external pressures. Nevertheless, methodological and sampling limitations remain: most investigations rely on surveys or case studies with limited representativeness, and empirical evidence is scarce regarding the dynamic effects of digital–intelligent transformation, the pathways through which it operates, and the mediating role of firms’ factor utilization.

To address these gaps, this study makes four contributions: First, it constructs a digital–intelligent transformation index by applying text-mining techniques to firms’ micro-level public disclosures, thereby improving measurement objectivity and coverage. Second, it examines the dynamic effects of digital–intelligent transformation on the productivity of manufacturing firms, informing the sector’s progression toward higher-quality and more sustainable development. Third, it evaluates the facilitating effects of transformation measures from the dual perspectives of internal incentives and external pressures, uncovering heterogeneous interactive effects between governance mechanisms and policy environments. Fourth, it develops a technology factor utilization lexicon and conducts mediation analyses along two dimensions—firms’ use of data factors and use of technological factors—to promote the transformation of enterprise management from relying on implicit experience to scientific management driven by data and technology.

3. Research Hypotheses

Digital–intelligent transformation can fundamentally break traditional production bottlenecks and effectively enhance production efficiency through technological enablement, process optimization, and decision-making upgrading. In terms of technological enablement, the application of IoT, industrial sensors, and automation equipment allows for real-time data collection across the entire production process and replaces repetitive manual operations. This reduces human inspection errors and equipment failure rates while enhancing production speed and quality stability through standardized operations, thereby lowering rework costs caused by human error. In process optimization, digital platforms such as ERP and MES can integrate information across orders, procurement, production, and warehousing, eliminating information silos and data lags. Combined with big data analytics, these systems help identify redundant process nodes, improve workflow coordination and resource allocation efficiency, and shorten overall production cycles. In decision-making upgrading, digital–intelligent tools can mine historical production data and market demand trends to accurately predict order volumes and material consumption, providing data support for production planning. They also enable dynamic monitoring of production progress and resource utilization, facilitating timely adjustments that prevent equipment idleness and material waste, thus maximizing total factor productivity. Based on the above analysis, this study proposes the following:

H1. Digital–intelligent transformation improves firms’ total factor productivity.

Internal incentives and external pressures reinforce each other. External pressures stimulate the need for internal change, while the benefits achieved from successful internal transformation further strengthen firms’ motivation for continuous innovation. This positive feedback loop continually drives total factor productivity improvement. Internal incentives (such as employee compensation) and external pressures (such as media attention) both positively moderate the relationship between digital–intelligent transformation measures and TFP, with a synergistic effect. In other words, when employee compensation and media attention are higher, the impact of digital–intelligent transformation measures on total factor productivity becomes more significant.

From the perspective of motivation theory, based on Adams’ equity theory and Deci’s self-determination theory, employee compensation serves as a key internal incentive aligning employees’ knowledge input and labor returns in the digital–intelligent transformation process, satisfying their needs for autonomy, competence, and belonging. This enhances their enthusiasm, proficiency, and innovative engagement in using digital–intelligent tools, thereby strengthening the human capital foundation for transformation success.

From the institutional and resource dependence perspectives, high media attention functions as an external governance pressure. On the one hand, through legitimacy mechanisms, it compels firms to improve total factor productivity as a response to public scrutiny regarding operational efficiency and sustainability; on the other hand, through signaling effects, it helps attract the crucial resources needed for digital–intelligent transformation, such as technological partnerships and financial support. The synergy between internal and external factors forms a complementary “motivation–resource” loop: internal incentives solidify the human foundation for digital–intelligent adoption, while external attention expands resource channels and enhances oversight, jointly amplifying the productivity-driving value of intelligent and digital measures. Based on the above analysis, this study proposes the following:

H2. Internal incentives and external pressures both positively moderate the relationship between intelligent and digital measures and firms’ total factor productivity.

In the context of increasing production complexity in manufacturing, the marginal efficiency of traditional production factors such as labor and capital is gradually declining, making it difficult to sustain productivity growth. Data and technology have become new key production factors, breaking traditional efficiency constraints and reflecting enterprises’ actual capacity for digital-era resource allocation and utilization.

Data elements integrate information across the entire production process, including orders, equipment, and energy consumption, providing accurate input for production decisions. Technology elements serve as the crucial enabler that transforms data value into production efficiency and restructures production processes. Digital–intelligent measures enhance both: by collecting real-time data across production stages, they eliminate “data silos” and convert dispersed information resources into actionable factors for production optimization, improving data–element utilization. Simultaneously, by enhancing technological adaptability, they lower barriers to technology adoption and promote the deep integration of technology elements across the entire production chain—from basic tool usage to comprehensive process embedding.

Therefore, digital–intelligent measures in manufacturing enhance production efficiency by improving the utilization of both data and technology elements. Improved data–element utilization reduces resource misallocation, while enhanced technology–element utilization minimizes manual errors and process delays. Their synergistic effect directly optimizes production processes. Based on the above analysis, this study proposes the following:

H3. Digital–intelligent measures in manufacturing indirectly improve firms’ production efficiency by significantly enhancing the utilization of data and technology elements.

4. Description of the Models, Variables, and Data

4.1. Variable Selection

4.1.1. Measurement of Digital–Intelligent Transformation in Manufacturing

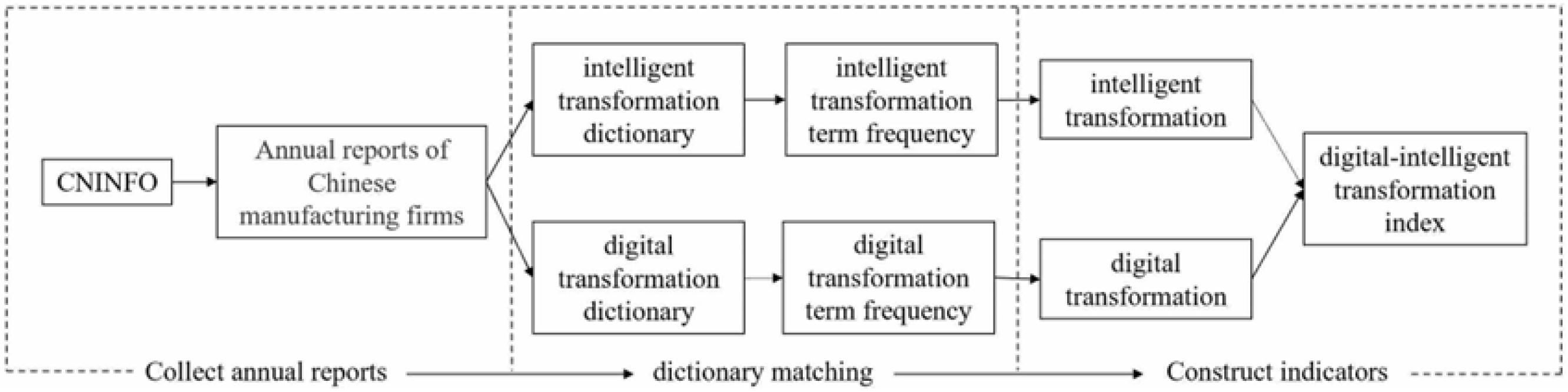

In constructing the digital–intelligent transformation index for the manufacturing sector, we follow the keyword dictionaries for digital–intelligent transformation identified in the existing literature. The degree of digital–intelligent transformation is measured by counting the frequency of keywords from the dictionaries disclosed in the annual reports of listed companies.

The intelligent transformation dictionary refers to the approach of Yao [

26], in which the frequencies of 73 artificial intelligence-related keywords are counted. The digital transformation dictionary follows the method of Wu [

27], in which the frequencies of 76 digitalization-related keywords are collected across five dimensions: artificial intelligence technology, big data technology, cloud computing technology, blockchain technology, and the application of digital technologies.

The construction process of the digital–intelligent transformation index is as follows: First, annual reports of Chinese manufacturing firms from 2001 to 2023 are retrieved from The Information Disclosure Website designated by the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CNINFO). After removing non-compliant and duplicate reports, the remaining reports are converted into text format. Second, the Python jieba -0.42.1 segmentation tool is used to tokenize the text, incorporating the pre-constructed digital–intelligent transformation dictionary, and keyword frequencies are counted. Finally, the keyword frequencies for digital–intelligent transformation are summed, one is added to each sum, and the natural logarithm is taken; the interaction term of the two logged values is used as the digital–intelligent transformation index (AIDX). The detailed procedure is illustrated in

Figure 1.

4.1.2. Measurement of Data–Element Utilization in Manufacturing

Following the method proposed by Dai [

28], this study establishes a data–element utilization dictionary based on relevant policy documents such as the 14th Five-Year Plan for the Development of the Digital Economy and the White Paper on Data Elements series of research reports. Using this dictionary, word frequency statistics are performed on the annual reports of manufacturing enterprises collected in an earlier stage to generate the frequencies of keywords related to data–element utilization. The frequencies of these keywords are then summed, incremented by one, and transformed using the natural logarithm. The resulting value is employed as the indicator of data–element utilization for manufacturing enterprises.

4.1.3. Measurement of Technology–Element Utilization in Manufacturing

Based on the policy documents, the 14th Five-Year Plan for the Development of Intelligent Manufacturing jointly issued by eight departments, including the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of China, and the New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan released by the State Council, this study manually screens and identifies keywords related to technology–element utilization. Following the research approach of Li, the Word2Vec technique and its Skip-gram model proposed by Mikolov are employed to train a model using words from corporate annual reports and patent texts as the training corpus [

29,

30]. Subsequently, for each seed word, the words with the highest cosine similarity are selected to identify the most semantically similar terms, and duplicate words are removed.

From this process, a technology–element utilization dictionary is constructed across four dimensions: foundational support technologies, artificial intelligence technologies, intelligent manufacturing and automation technologies, and intelligent interaction and virtual technologies. Based on the constructed dictionary (see

Table 1), word frequency statistics are then performed on the previously collected annual reports of manufacturing enterprises to generate the frequencies of technology–element utilization keywords. The frequencies of these keywords are summed, incremented by one, and log-transformed using the natural logarithm. The resulting value serves as the indicator of technology–element utilization for manufacturing enterprises.

4.1.4. Control Variables

Following Yao and Zhao [

26,

31], we include the following control variables:

Firm size (Size): Larger firms are more likely to enjoy economies of scale and richer resource allocation capabilities, which may affect productivity. Size is measured as the natural logarithm of the number of employees.

Liquidity ratio (Liquid): Reflecting short-term solvency and liquidity, the adequacy of cash and liquid assets influences the continuity and stability of daily operations and, thus, productivity. Liquid is measured as the ratio of current assets to total assets.

Return on assets (Roa): Measuring the firm’s ability to generate profit from its total assets, higher profitability is often associated with advantages in technological upgrading and management efficiency, which relate to productivity. Roa is measured as net profit divided by total assets.

Firm age (Age): Older firms may have accumulated richer production experience and managerial knowledge but may also exhibit organizational inertia; hence, age may have a mixed effect on productivity. Age is measured as the natural logarithm of (2024 minus the year of establishment + 1).

Ownership concentration (Share): Indicating the distribution of equity, ownership concentration affects corporate governance and decision-making efficiency, thereby influencing productivity. Share is measured as the aggregated shareholdings of the top five shareholders.

Asset ratio (Leverage): Reflecting capital structure, excessively high indebtedness may increase financial risk, while excessively low leverage may miss investment opportunities; both conditions can impact productivity. Leverage is measured as total liabilities divided by total assets.

Asset structure (Tang): Representing the proportion of tangible assets, as fixed assets and inventories constitute the material basis for production, their share affects production capacity and asset turnover. Tang is measured as (net fixed assets + net inventories) divided by total assets.

4.2. The Empirical Models

To examine the impact of digital–intelligent transformation on the total factor productivity (TFP) of manufacturing enterprises, we construct the following empirical model:

In Equation (1), TFPi,t denotes the total factor productivity of firm i in year t, which is calculated using the Olley–Pakes (OP) method; AIDXi,t represents the index of digital–intelligent transformation; i and t indicate the firm and year, respectively; εi,t is the random error term; and year, pro, and ind denote the year, province, and industry fixed effects, respectively.

Controls

i,t refers to the control variables. Following Yao and Zhao [

26,

31], this study includes the following control variables: firm size (Size), liquidity ratio (Liquid), return on assets (ROA), firm age (Age), ownership concentration (Share), asset ratio (Leverage), and asset structure (Tang). The descriptions of the variables are presented in

Table 2, and the descriptive statistics for each variable are provided in

Table 3.

4.3. Data Issues

This study takes A-share listed manufacturing firms in China as the research sample, focusing on the period from 2001 to 2023. Annual reports of manufacturing firms are obtained from the CNINFO. Firm-level basic information is collected from the MARC Database, while media coverage data are obtained from the Chinese Research Data Services Platform (CNRDS).

To ensure data quality, the sample is processed as follows:

(1) From all Chinese A-share listed firms on the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges, we select those classified under the manufacturing sector.

(2) Firms designated as *ST or ST in a given year are excluded.

(3) Observations with missing data are removed.

(4) To mitigate the influence of extreme values, all continuous variables are Winsorized at the 1 percent and 99 percent levels.

5. Empirical Results

5.1. Baseline Regression of the Productivity Effect of Digital–Intelligent Transformation in Manufacturing

The regression results are reported in

Table 4. Column (1) presents the model without the control variables, whereas Column (2) includes the control variables. The results indicate that the regression coefficient of the digital–intelligent transformation index for manufacturing firms is significantly positive at the 1 percent level, suggesting that digital–intelligent transformation initiatives can effectively enhance the total factor productivity of manufacturing enterprises.

Regarding the control variables, the coefficient of Liquid is significantly negative, indicating that the current ratio exerts an inhibitory effect on production efficiency. Specifically, a substantial increase in current liabilities may intensify firms’ short-term debt repayment pressure, thereby adversely affecting production efficiency. Similarly, the coefficient of Leverage is significantly negative, suggesting that higher leverage levels hinder improvements in production efficiency, while moderate debt control can enhance operational flexibility. The coefficient of Tang is also significantly negative; this may be attributed to an imbalance between fixed and current assets, which lowers capital utilization efficiency and consequently suppresses production efficiency.

Conversely, the regression coefficients of the other control variables are all significantly positive, indicating that firm size (Size), return on assets (ROA), firm age (Age), and ownership concentration (Share) positively influence production efficiency. Specifically, larger firms often enjoy advantages in resources and economies of scale; a higher ROA reflects better asset management efficiency; older firms typically have richer experience and more stable operational processes; and concentrated ownership facilitates improved decision-making efficiency, collectively promoting enhanced production efficiency.

5.2. Robustness Checks

5.2.1. Tests Using Alternative Firm Productivity Measures

Using the total factor productivity of firms estimated via the Levinsohn–Petrin method (TFP_LP) as the dependent variable, we conduct further robustness checks (see

Table 5). The results show that, regardless of whether the control variables are included, the coefficient of the AIDX indicator remains statistically significant. Moreover, the signs of the coefficients for both the explanatory and control variables in this regression are consistent with those in the model based on total factor productivity estimated via the Olley–Pakes (OP) method. This consistency confirms the robustness of the aforementioned results.

5.2.2. Difference-in-Differences (DID) Method

We employ the Difference-in-Differences (DID) method and the Propensity Score Matching Difference-in-Differences (PSM-DID) method to examine the impact of digital–intelligent transformation initiatives on the total factor productivity of manufacturing firms. Both the DID and PSM-DID approaches estimate the net policy effect by comparing changes in the treatment and control groups before and after policy implementation, thereby effectively controlling for time trends and other unobservable factors. The empirical model is specified as follows:

The variable definitions are consistent with those in the previous sections. Post and Treat are dummy variables. In May 2015, the State Council released Made in China 2025, which, for the first time, set forth the strategic objective of promoting digital–intelligent transformation and upgrading in China’s manufacturing sector. This policy substantially reduces the institutional barriers and costs associated with firms’ digital–intelligent transformation through channels such as policy guidance, financial and institutional support, demonstration promotion, and ecosystem construction, thereby accelerating the digital and intelligent transformation of manufacturing enterprises. Accordingly, we set the year 2016 as the policy implementation year. For samples after 2016, Post is set to 1; for those before 2016, Post is set to 0. The “Made in China 2025” document explicitly lists ten key sectors—such as new-generation information technologies, high-end CNC machine tools and robots, and aerospace equipment—as reform priorities. Accordingly, firms operating in these designated key industries are also coded as Treat = 1, with all other firms coded as Treat = 0. As shown in

Table 6, the coefficient on the Treat × Post interaction is significantly positive under both the DID and PSM-DID specifications, indicating that firms’ digital–intelligent transformation has a positive effect on production efficiency.

5.2.3. Instrumental Variable (IV) Approach

To mitigate potential endogeneity, this study adopts the instrumental variable (IV) approach, using the proportion of R&D personnel in manufacturing firms (RDPerson) as an instrument for digital–intelligent transformation. This choice is theoretically justified. First, R&D teams serve as the core in absorbing and reinventing digital technologies, and their size reflects the firm’s intensity of resource allocation toward technological upgrading, making it strongly correlated with digital–intelligent transformation. Second, R&D personnel influence total factor productivity (TFP) primarily through this transformation channel. By controlling for firm characteristics such as size, liquidity, and profitability, the instrument satisfies the exogeneity condition. The empirical results show that the Cragg–Donald F-statistics are greater than the Stock–Yogo 10% critical value, and the K–P LM statistic rejects the null hypothesis of under-identification at the 1% significance level, confirming the validity of the instrument.

Table 7 presents the two-stage least squares (2SLS) results. In the first stage, the coefficient on RDPerson is 0.0556 and statistically significant. In the second stage, the coefficient on the interaction term Instrumented_AIDX is 0.144 and statistically significant. The model results provide further evidence that digital–intelligent transformation in the manufacturing sector has a positive effect on firms’ total factor productivity.

5.2.4. Alternative Sample

As some firms had not implemented digital–intelligent transformation measures, we further conduct a robustness test by excluding such firms from the sample. Specifically, we drop manufacturing firms whose digital–intelligent transformation indicator equals zero and then re-estimate the regression model. As reported in

Table 8, the estimated coefficient of the explanatory variable AIDX remains positive and statistically significant. All control variables are also significant, and their signs are consistent with those in the baseline regression results, indicating the robustness of our findings.

5.2.5. Alternative Sample Period

As previously mentioned, the State Council issued Made in China 2025 in 2015. In light of this, we shorten the sample period to 2016–2023 and re-estimate the regression model. As reported in

Table 9, the coefficients of the core explanatory variables remain positive and statistically significant, indicating the robustness of our conclusions.

6. Dynamic Effects Analysis

Given that the impact of digital–intelligent transformation measures on the total factor productivity of manufacturing firms is typically subject to a certain degree of lag, we further re-estimate the model by introducing lags of the main explanatory variable AIDX from one to four periods. The results, reported in

Table 10, show that the coefficients of the explanatory variable are positive and statistically significant for lags of one to three periods, with the magnitude declining over time. This indicates that digital–intelligent transformation has a lagged effect on total factor productivity and that such an effect diminishes year by year. When the explanatory variable is lagged by four periods, the coefficient becomes statistically insignificant, suggesting that digital–intelligent transformation measures implemented four years earlier no longer exert an impact on total factor productivity. This may be due to two main reasons: First, the technological effects gradually attenuate over time; technology upgrades implemented four years earlier may no longer contribute to total factor productivity. Second, intensified market competition has prompted a large number of manufacturing firms to embark on transformation initiatives, thereby reducing the relative advantage gained from earlier technological upgrades and ultimately rendering the effect of digital–intelligent transformation on total factor productivity insignificant.

7. Facilitative Effect of Digital–Intelligent Transformation Measures

Internal incentives and external pressure may both influence how digital–intelligent transformation measures enhance total factor productivity. Internal incentives (Internal) are proxied by employee compensation payable; specifically, Internal is a dummy that equals 1 if the current year’s employee compensation payable exceeds the sample mean; otherwise, it equals 0. External pressure (External) is proxied by media exposure, measured as the sum of annual newspaper and online news coverage. The dummy External equals 1 if the company’s annual media coverage exceeds the sample mean; otherwise, it equals 0.

As shown in

Table 11, Column (1), the coefficient on the interaction term AIDX × Internal is significantly positive at the 5 percent level, indicating that higher internal incentives strengthen the positive effect of digital–intelligent transformation on firm total factor productivity. In Column (2), the coefficient on AIDX × External is significantly positive at the 1 percent level, suggesting that greater external pressure also amplifies this effect.

8. Mechanism Analysis

This study adopts a mediation model to empirically examine the mechanism by which digital–intelligent transformation (AIDX) affects firms’ total factor productivity (TFP) in manufacturing. The full mediation model is specified as follows:

Here INTER denotes the mediator variable, and all other variables are defined as above. In Equation (3), the coefficient on AIDX captures the total effect of digital–intelligent transformation in manufacturing on firms’ total factor productivity. In Equation (4), the coefficient on AIDX captures the effect of digital–intelligent transformation on the mediator. In Equation (5), the coefficients on AIDX and INTER represent the direct effects of digital–intelligent transformation and the mediator, respectively, on firms’ total factor productivity. The mediation mechanism is examined using a stepwise regression procedure.

8.1. Data–Element Utilization

Li found that the use of data elements not only lowers manufacturing firms’ costs of acquiring information on user preferences and market demand but also enables firms to analyze these data to forecast future market demand and promptly adjust and optimize sales strategies, thereby reducing sales costs [

32]. This study uses the data–element utilization indicator (Data) to examine its mediating role. As shown in

Table 12, the coefficients on AIDX and Data are both significantly positive, and both pass the Sobel and Goodman tests. The mediating effect accounts for 23.50 percent of the total effect, indicating a meaningful mediation. These results suggest that digital–intelligent transformation measures can enhance firms’ total factor productivity by altering the degree of data–element utilization.

8.2. Technological–Element Utilization

Technological elements are the core drivers of a firm’s digital–intelligent transformation. This study uses the technology–element utilization indicator (Technology) constructed in this work to examine the mediating role of technology–element utilization. The results, shown in

Table 13, indicate that both AIDX and Technology have positive and statistically significant coefficients; both Sobel and Goodman tests confirm the mediation effect. The mediating effect accounts for 13.13 percent of the total effect, suggesting a significant mediating role. These findings imply that digital–intelligent transformation measures can enhance enterprises’ total factor productivity by altering the utilization of technological inputs.

9. Discussion and Conclusions

This study takes Chinese manufacturing firms listed on the domestic stock market from 2001 to 2023 as a sample. By applying text-mining techniques to the annual reports of listed companies, we construct, at the micro-level, three indicators: a digital–intelligent transformation indicator, a data–element utilization indicator, and a technology–element utilization indicator. Through an empirical analysis, we obtain the following conclusions: First, based on a total factor productivity model for digital–intelligent transformation in manufacturing, we examine the impact of these measures on firms’ total factor productivity and find that digital–intelligent transformation measures significantly enhance the total factor productivity of firms, with a series of robustness checks confirming the result. Second, dynamic tests indicate that, after implementing digital–intelligent transformation measures, firms’ total factor productivity increases over the next three years. Third, concerning the promoting effects of digital–intelligent transformation, we analyze two dimensions—internal incentives and external pressures—and find that both promote the positive effect of digital–intelligent transformation measures on firms’ total factor productivity. Fourth, treating data–element utilization and technology–element utilization as the key determinants of firms’ input utilization, and based on this mechanism analysis, we conclude that digital–intelligent transformation measures can increase both data–element utilization and technology–element utilization, thereby further enhancing firms’ total factor productivity.

9.1. Contributions

Although existing studies on corporate digital–intelligent transformation have yielded substantial findings, certain methodological limitations remain. Most current research relies on questionnaire surveys or focuses on a limited number of representative firms, resulting in a restricted sample coverage and an inability to comprehensively reflect the overall situation of the target population. In particular, empirical studies focusing on the impact of digital–intelligent transformation measures on firms’ productivity in the manufacturing sector are still relatively scarce. The existing literature lacks systematic explorations of the dynamic effects, promotion mechanisms, and element utilization efficiency associated with the digital–intelligent transformation of manufacturing enterprises.

To address these research gaps, this study constructs a digital–intelligent production efficiency model and empirically examines the impact of digital–intelligent transformation on the total factor productivity (TFP) of Chinese manufacturing firms. Furthermore, it investigates in detail the mechanisms and promotional effects underlying this transformation process. The marginal contributions of this study are reflected in the following four aspects:

First, this study employs text-mining techniques to construct quantitative indicators of digital–intelligent transformation at the micro-level, thereby overcoming the limitations of conventional survey data. It systematically examines the influence of digital–intelligent transformation measures on enterprise production efficiency.

Second, it focuses on the dynamic effects of digital–intelligent transformation in manufacturing enterprises, investigating not only its short-term impact but also its sustained contribution to firms’ total factor productivity. This provides theoretical foundations and policy insights for achieving high-quality and sustainable development in the manufacturing sector.

Third, from the dual perspective of internal incentives and external pressures, this study explores the facilitating effects of digital–intelligent transformation measures. This perspective helps enterprises comprehensively identify the driving forces and coping strategies in the transformation process.

Fourth, by constructing a technology utilization dictionary, this study conducts mediation effect analyses based on the two dimensions of data utilization and technology utilization. It reveals their intermediary roles between digital–intelligent transformation and total factor productivity, promoting the evolution of enterprise management from a traditional “experience-driven” model toward a “data + technology” dual-engine, science-based decision-making paradigm.

9.2. Practical Contributions

The practical contributions of this study mainly lie in the provision of targeted managerial and policy guidance for manufacturing enterprises, offering an actionable framework for digital–intelligent transformation supported by empirical evidence.

First, this study provides efficiency-oriented empirical evidence for decision-making in digital–intelligent transformation. Against the background of manufacturing transformation and upgrading, although managers generally recognize the importance of digital–intelligent transformation, they often lack a clear understanding of its actual impact on efficiency enhancement. By constructing enterprise-level indicators of digital–intelligent transformation, the empirical results confirm that such a transformation significantly improves firms’ total factor productivity, and the conclusion remains robust after multiple validation tests. This finding offers managers a clear basis for value judgment, helping them avoid blind transformation characterized by “high investment but low effectiveness”, and it emphasizes the positioning of digital–intelligent transformation as a core path to improving production efficiency. Through intelligent upgrading and digital system integration, managers can effectively release the transformation dividends and maximize efficiency gains.

Second, this study offers long-term strategic guidance through dynamic analyses. The dynamic effect tests enrich the temporal dimension of transformation practice, showing that the positive effects of digital–intelligent transformation on total factor productivity can persist for up to three years after implementation. Accordingly, managers are encouraged to abandon short-term, utilitarian thinking and instead formulate medium- and long-term transformation strategies. They should establish dynamic evaluation mechanisms for transformation progress; regularly monitor technological adaptability, process integration, and efficiency conversion; and optimize transformation strategies in line with industrial technology evolution and corporate development stages to ensure the sustainable release of transformation effects.

Third, this study identifies the synergistic driving paths of internal and external coordination. The moderating effect results reveal how enterprises can optimize transformation drivers. Firms should simultaneously enhance internal incentives and leverage external forces. Specifically, firms should pay attention to the following: on the internal incentive side, they should establish a compensation system commensurate with the value of human capital, for example, by raising employee wages to strengthen staff initiative and commitment to the transformation; on the external pressure side, they should actively monitor public opinion and market evaluations, for instance, by tracking the volume of media coverage, promptly responding to external expectations, and enhancing corporate transparency and reputation. Together, these measures can more effectively promote digital–intelligent transformation and improve production efficiency.

Finally, this study reveals the core enabling mechanisms and policy implications. A mechanism analysis confirms that digital–intelligent transformation boosts production efficiency by enhancing the utilization of data and technology elements. This conclusion provides both managerial and policy insights. For managers, it identifies key transformation focuses—strengthening data governance capabilities (such as data analysis and data-driven decision-making) and technological R&D and application capabilities (such as adopting advanced technologies and intelligent equipment)—to establish a clear value transmission chain of “transformation–elements–efficiency.” For policymakers, the findings offer empirical support for further improving the construction of the data–element market and increasing policy support for technological innovation in manufacturing, thereby creating a favorable factor environment for enterprise digital–intelligent transformation and promoting efficiency improvement across the manufacturing sector.