Abstract

Pragmatic sustainability emphasizes that policies must adapt to the reality of multi-level governance to balance targets and feasibility. To explore how this concept is embodied in China’s carbon peaking policies, this study adopted natural language processing (NLP) and machine learning methods to conduct a systematic quantitative analysis of 316 carbon peaking policy documents spanning from the national to county levels in China. The findings reveal that the policy system presented a distinct logic of pragmatic coordination. The application of legal instruments decreased with descending administrative levels, whereas that of supervision instruments showed the opposite trend; central-level targets were more flexible, while local governments demonstrated higher policy intensity in specific targets and livelihood-related sectors. The regional differences in policy intensity were closely associated with local economic development and energy structure, indicating that future policy optimization should more thoroughly implement the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities in target decomposition and dynamic adjustment. This study not only provides a novel quantitative perspective for investigating pragmatic sustainability in carbon peaking policy texts but also offers critical empirical evidence for synergistically advancing SDG 13 (climate action) with other SDGs.

1. Introduction

Climate change stands as one of the most formidable challenges to global sustainable development. In response, the international community established the long-term goal through the Paris Agreement to limit the global average temperature increase to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels and pursue efforts to limit it to 1.5 °C [1]. It also closely linked climate action (SDG13) with other Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), such as affordable and clean energy (SDG7), sustainable cities and communities (SDG11), and responsible consumption and production (SDG12) [2]. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change further emphasized that achieving net-zero emissions by mid-century is essential to avoid catastrophic climate impacts [3]. Consequently, an increasing number of countries have enacted policies [4], adopting measures from political [5], technological [6], and market-based [7] perspectives to address climate change. As the world’s largest carbon emitter, China’s emission reduction pathway plays a pivotal role in global climate governance and synergistic achievement of the SDGs [8].

In 2020, China pledged to strive for carbon peaking by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060 [9], signifying the full integration of climate change response into the national sustainable development strategy [10]. Subsequently, China has gradually established a “1 + N” policy framework for carbon peaking and carbon neutrality. Here, “1” refers to the overarching central-level documents, namely the “Opinions on Fully, Accurately, and Comprehensively Implementing the New Development Philosophy to Achieve Carbon Peaking and Carbon Neutrality” and the “Action Plan for Carbon Peaking Before 2030” (Plan), while “N” denotes the implementation plans for key sectors and industries [11]. This framework not only covers critical areas such as energy, industry, transportation, and construction but also, through refinement and implementation by local governments at various levels, forms a four-tier (national, provincial, municipal, and county) interconnected policy network [12]. As a crucial step for China to balance development with emission reduction and synergistically advance climate action alongside socioeconomic sustainability [13], the formulation and implementation of carbon peaking policies are directly linked to the progress of achieving the SDGs [14].

Climate policy texts serve as vital sources for understanding government governance intentions and the logic of sustainable transitions [15]. Traditional policy research methods, such as qualitative analysis [16] and case studies [17], often rely on researchers’ academic expertise and value positions, leading to results with strong subjective biases. Moreover, interpretive policy text analysis, while suitable for case studies, struggles with handling large-scale policy corpora. Additionally, models such as difference-in-differences (DID) [18], regression discontinuity design (RDD) [19], computable general equilibrium models [20], and fixed effects models [21] primarily focus on policy effects, with limited exploration of policy text content itself [22]. Recent studies have also begun to focus on local practices. For instance, the STIRPAT model was applied to reveal the heterogeneous impact of intensive urban land use on carbon emissions across Chinese cities, offering a new perspective for understanding local carbon source structures and differentiated policy needs [23].

In recent years, natural language processing (NLP) and machine learning technologies have provided new pathways for the quantitative analysis of policy texts. For example, a dataset on China’s environmental policy intensity was developed by combining manual annotation with machine learning [24]. Similarly, a global dataset on climate change mitigation policies was constructed by classifying information such as policy targets, instruments, and covered areas from policy texts using NLP methods [25]. In another study, a low-carbon policy intensity indicator was established based on the policy level, targets, and instruments through NLP algorithms and text-based rapid learning [26]. Furthermore, the evolution of China’s climate change policy stringency from 1954 to 2022 was investigated by integrating manual annotation with machine learning [27].

However, existing NLP-based policy studies still exhibit notable limitations. First, most research focuses on global, national, or provincial levels or on single policy dimensions, with insufficient coverage of municipal and county policies. This makes it difficult to present a complete picture of policies within China’s four-tier (national-provincial-municipal-county) governance system. Furthermore, there is inadequate attention paid to the autonomy and innovation of local governments in policy formulation and implementation, hindering the revelation of adaptive adjustments and localization characteristics during policy implementation at the local level, key factors influencing whether policies can genuinely drive local SDG achievement. Third, there is scarce NLP research specifically on carbon peaking policies, and the synergistic mechanisms between carbon peaking policies and SDGs remain underexplored.

Therefore, building upon existing NLP methods, this study focuses on China’s carbon peaking policy system, conducting systematic quantification, comparative analysis, and correlation analysis on carbon peaking implementation plans publicly released by governments at the national, provincial, municipal, and county levels. This research aims to explicitly address the following three questions. (1) What differences exist in instrument diversity, target precision, and policy intensity across China’s carbon peaking policies? (2) What do these differences reveal about the Chinese government’s action pathways, functional division of labor, and impact mechanisms in the sustainable transition? (3) What specific empirical evidence and policy insights can these findings provide for optimizing a multi-level, differentiated climate governance policy system to achieve the SDGs?

The contributions of this study are as follows. First, theoretically, it constructs a multi-level policy analysis framework integrating policy targets, instruments, and intensity, combining sustainable development theory with policy measurement research and thereby deepening the understanding of policy transmission and local innovation within multi-level governance systems. Second, methodologically, it overcomes the limitations of traditional policy analysis, which relies on proxy variables by integrating natural language processing with machine learning to systematically quantify carbon peaking implementation plans, thus transcending the constraints of traditional qualitative policy research. Third, practically, the findings can enhance the relevance and effectiveness of China’s climate policies, provide empirical evidence for achieving SDG13, and assist China in synergistically advancing the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development while pursuing its “dual carbon” goals.

The remaining sections of this paper are structured as follows. Section 2 introduces the data sources and policy quantification methodology for carbon peaking policy texts. Section 3 presents the quantitative results for policy keywords, instruments, and targets, laying the groundwork for discussing the core issue of policy intensity. Section 4 provides a discussion. Section 5 summarizes the key findings and policy implications and outlines the limitations and directions for future research.

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Data Source

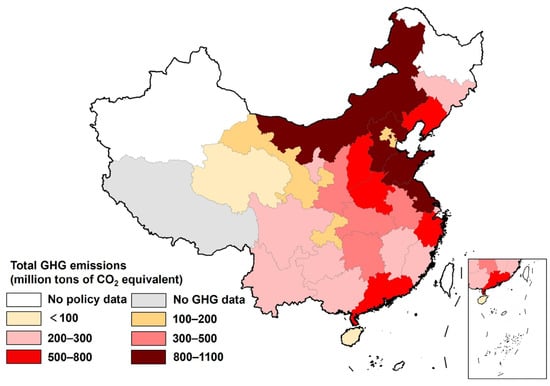

Carbon peaking implementation plans are issued by people’s governments at various levels. Due to the characteristics of China’s administrative system, data transparency across government levels is limited [28]. To comprehensively collect publicly available policy texts, this study employed an exhaustive approach, systematically retrieving and gathering documents through multiple public channels [29], including official government websites, the China Carbon Neutrality Network (https://www.ccn.ac.cn/), and the PKULAW database (https://www.pkulaw.com/). As of 30 October 2025, a total of 316 publicly released policy texts were collected, comprising 1 national-level document (Plan), 24 provincial-level documents, 149 municipal-level documents, and 142 county-level documents. Figure 1 shows the total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions of the provincial-level administrative regions that have released documents. It should be noted that the data only include policies that are publicly accessible. The absence of retrieved documents for certain regions does not necessarily indicate the absence of such plans; it may be the result of unpublished information or restricted access channels. Therefore, this study has objective limitations in coverage, such as potential geographical representation bias and policy completeness bias, which may affect judgments about the completeness of the national policy layout and the analysis of the entire policy evolution process. Although the existing database cannot encompass all policies from all provinces, cities, and counties, it is sufficient for conducting relevant analyses.

Figure 1.

The total GHG emissions of each provincial administrative region.

2.2. Methodology

2.2.1. Natural Language Processing

Unlike structured data such as numbers and symbols, policy texts cannot be represented by numbers or a uniform structure and are typically unstructured data. The inherent complexity of this type of data makes it difficult for computers to understand the information it contains [30]. Therefore, processing unstructured data like policy texts often requires more time and effort. Natural language processing can extract and mine valuable information from policy texts [31], thereby generating specific data that can be used for analysis [32]. The specific steps are as follows:

- (1)

- Data cleaning [33]: Remove the guiding ideology, departments responsible for division of labor, etc. from the text and standardize the text format.

- (2)

- Use Jieba for word segmentation and extract the key words and their weights in each policy text. Jieba is a Python-based (Python 3.11.7) Chinese natural language processing toolkit widely used for Chinese text segmentation, keyword extraction, and weight calculation.

- (3)

- Policy classification: Extract policy instruments from the text based on key words and uniformly define the remaining policy content as policy objectives.

- (4)

- Policy instrument scoring: Existing studies primarily classify policy instruments into 3–4 categories, such as command-and-control, market-based incentives, public participation, and composite types [26,34,35]. Examples include taxes [27], subsidies [36], tradable permits [37], economic support, technological innovation, and management improvements [38]. The choice of policy instruments by governments is influenced by multiple factors [17], and different instruments have varying effects on policy implementation outcomes [39,40]. A preliminary analysis of carbon peaking implementation plans reveals that their policy instruments are highly concentrated in three dimensions: regulation establishment, market regulation, and execution supervision. This specificity leads to significant differences in the type composition, mechanism of action, and implementation pathways; command-and-control instruments lean toward legislation, while public participation instruments lean toward public oversight. Therefore, drawing on Liao (2018) [34], this paper classifies policy instruments into legal (rigid constraints through laws, standards, approvals, etc.), market (guidance through economic means like pricing, fiscal, taxation, and finance), and supervision (ensuring execution through mechanisms like assessment, evaluation, rewards, and penalties). The keywords and scores for each instrument type are 3, 2, and 1, respectively (Table 1). It is noteworthy that a single policy sentence may contain multiple instrument keywords. However, following the uniqueness principle, each sentence was assigned to only one instrument category, with prioritization in the order of legal > market > supervision.

Table 1. Keywords, examples, and scores for policy instrument and policy target.

Table 1. Keywords, examples, and scores for policy instrument and policy target. - (5)

- Manual marking of policy targets: One third of the policy target documents are randomly selected for manual annotation. Most existing studies’ scores are based on the precision of textual descriptions. For instance, A 4-level scoring system (3, 2.25, 1.5, 0.75) for energy-saving targets was established based on the clarity of expression [26]. Building on this, this paper categorizes policy targets into three types based on whether the text contains precise numerical values and key elements. Sentences with specific quantified values were classified as the precise type and scored as 3; texts that did not contain key elements such as a time and place or were expressed ambiguously were classified as the vague type and received a score of 1. Texts that fell between the two were uniformly set as the general type and received a score of 2 (Table 1).

- (6)

- Calculation of policy intensity: At present, there is no unified standard for the definition of and calculation method for policy intensity in various studies. In existing research, policy intensity has been conceptualized primarily through two distinct approaches. One approach defines policy intensity as the product of the policy instrument intensity and policy target intensity, emphasizing that these two components together constitute the complete dimension of policy intervention [24]. Another approach expands this model by incorporating the factor of the policy level, defining policy intensity as the product of the policy instrument intensity, policy target intensity, and policy level intensity, thereby offering a more comprehensive characterization of a policy’s overall impact [26]. Since this study investigates hierarchical differences, it refers to the method of Zhang et al. (2022) [24], defining policy intensity as the product of the policy target intensity and policy instrument intensity:

Pi is the policy intensity of a policy text, and Ii and Ti are the sum of policy instrument intensity and the sum of policy target intensity of the same policy text, respectively.

2.2.2. Machine Learning

As a core branch of artificial intelligence, the core idea of machine learning is to learn patterns from data and use these patterns to make predictions or decisions about new data [41]. This paper recognizes and classifies text based on natural language processing and combined with machine learning models. First, TF-IDF [42], BOW [43], and N-gram [44] were selected to vectorize the manually annotated policy texts. Then, MNB [45], SVM [46], and RF [47] were selected for text classification. The three text vectorization models and three classifiers were combined, and 75% of the labeled dataset was used for training, with the remaining 25% used for validation. The performance of the nine model combinations was evaluated using four metrics: accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score. The results indicated that model combinations involving SVM outperformed those with MNB and RF. Subsequently, a grid search was conducted for parameter optimization to select the best model combination, and 5-fold cross-validation was used to evaluate its performance. The results showed that the TF-IDF+SVM combination performed best, with all four metrics reaching 0.87, as shown in Table 2 below. Therefore, this paper adopted the TF-IDF+SVM combination for text classification.

Table 2.

Model optimization performance.

3. Results

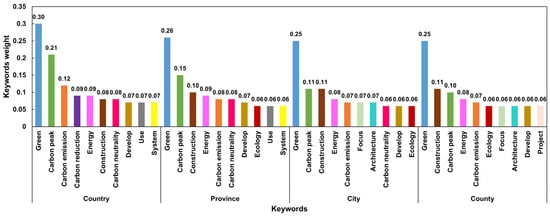

3.1. Policy Keywords

Keywords from carbon peaking policies at the national, provincial, municipal, and county levels were extracted using Jieba segmentation to analyze the policy focus and orientation (Figure 2). Firstly, “green”, “carbon peak”, “energy”, and “construction” are core keywords, indicating that promoting carbon reduction through green transition and energy transformation has been deeply integrated into the national governance system [48]. Furthermore, national and provincial levels focus on coordinating resources through a planning “system”, while municipal and county levels emphasize grassroots construction terms such as “architecture”, “ecology”, and “project”, e.g., through solar power generation projects and ecological restoration projects. This reflects the action pathways of local governments in achieving the SDGs based on local conditions.

Figure 2.

Keyword comparison across different government levels.

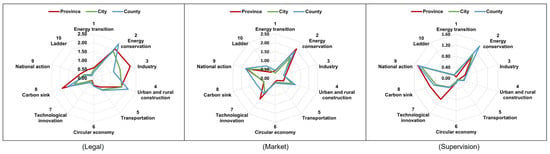

3.2. Hierarchical Differences in Policy Instruments

Systematic differences exist in the use of policy instruments across different government levels [49] (Table 3). The use of legal instruments decreases with lower administrative levels, aligning with China’s top-down power structure [50]. Market instruments are most prominent at the provincial level, reflecting that provincial governments, as regional coordinators, rely more on economic measures to balance emission reduction and growth, such as government procurement [51] and green finance [52]. Supervision instruments increase progressively down the hierarchy, indicating that grassroots governments focus more on policy implementation and outcome assurance.

Table 3.

The average proportions of policy instruments.

Among the carbon peaking implementation plans issued by various governments, the Ten Major Actions for carbon peaking are regarded as key tasks and are consistently integrated throughout the entire process and all aspects of economic and social development. Specifically, they are integrated as follows: (1) green and low-carbon transformation of energy (energy transition), (2) energy conservation, carbon reduction, and efficiency improvement (energy conservation), (3) carbon peaking in the industrial sector (industry), (4) carbon peaking in urban and rural construction (urban and rural construction), (5) green and low-carbon transportation (transportation), (6) a circular economy to support carbon reduction (circular economy), (7) green and low-carbon technological innovation (technological innovation), (8) consolidation and enhancement of carbon sink capacity (carbon sink), (9) green and low-carbon actions for all (national action), and (10) orderly carbon peaking actions in various regions in a phased manner (ladder). When analyzing the characteristics of the 10 major actions, we strictly followed the name definitions in the “plan”. Some regional policies have different expressions of and definitions for each action, and they were not included in this analysis.

Among the Ten Major Actions, the distribution of policy instruments showed distinct sectoral characteristics (Figure 3). Legal instruments were concentrated in areas with clear technical standards or strong ecological imperatives (e.g., energy conservation, industry, and carbon sink), highlighting the foundational role of regulatory measures. Market instruments were used more in areas with obvious incentive orientation (e.g., technological innovation and national action), indicating policies’ attempts to guide behavioral changes through economic leverage. Notably, the circular economy had the fewest policy instruments, which echoes Yang et al.’s (2024) finding in environmental policy research that “the use of economic instruments is relatively limited” [53], reflecting insufficient policy support for resource recycling.

Figure 3.

The distribution of three policy instruments among the Ten Major Actions.

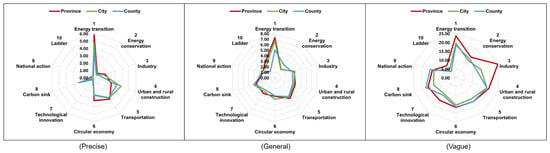

3.3. Hierarchical Differences in Policy Targets

Policy target setting showed significant hierarchical differentiation (Table 4), which is essentially an inevitable outcome of the layered operation of China’s governance system [54]. Provincial and municipal policy targets exhibited the highest precision, undertaking the crucial function of translating national strategies into executable and assessable specific indicators. National-level targets maintained greater ambiguity, leaving necessary space for differentiated local implementation, reflecting the application of the “common but differentiated responsibilities” principle in multi-level governance [55]. County-level target precision was relatively limited, reflecting the practical constraints in data foundations and governance capacity at the grassroots level [56].

Table 4.

The average proportions of the policy targets.

Among the Ten Major Actions (Figure 4), the energy transition had the most specific and numerous targets, indicating clear technological pathways and strong consensus for transition in this field. The ladder had the fewest and most vaguely expressed targets, reflecting the complexity of coordinating regional disparities. This difference suggests that in emission reduction areas with mature technologies, policies tend to set quantitative targets, whereas in areas involving regional equity and development rights, policies maintain the necessary flexibility to balance diverse demands.

Figure 4.

The distribution of policy targets among the Ten Major Actions.

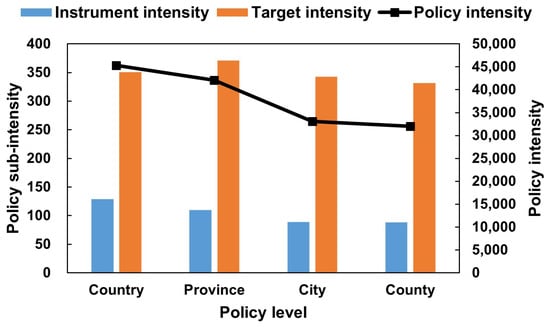

3.4. Hierarchical Differences in Policy Intensity

Policy intensity showed a sequentially decreasing trend (Figure 5), which aligns with the top-down transmission characteristic of carbon peaking policies, reflects the transmission loss between central and local policies, and reveals the phenomenon of “hierarchical decay” in policy diffusion [57]. However, provincial levels surpassed the central level in terms of policy target intensity, indicating that provincial governments play a key transformative role in the target specification process.

Figure 5.

Average policy intensity under different administrative levels.

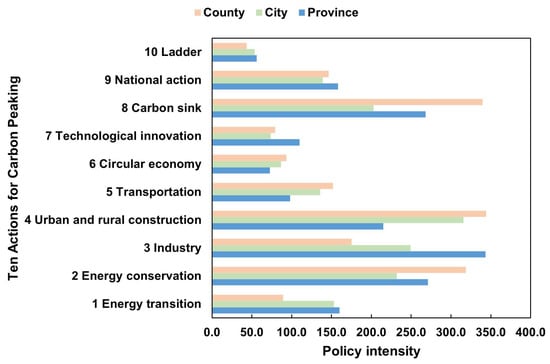

Among the Ten Major Actions (Figure 6), in key emission sectors such as energy and industry, the intensity decreased with lower administrative levels, reflecting strong central dominance. In contrast, in implementation-oriented sectors such as urban-rural construction, transportation, and a circular economy, the policy intensity at the grassroots level was higher, indicating that these sectors rely more on local innovation and localized execution. This precise division of labor and differentiated implementation mechanisms provides institutional space for advancing the SDGs (especially SDGs 7, 9, 11, and 13) across multiple levels.

Figure 6.

Policy intensity in the Ten Major Actions.

4. Discussion

Using the Pearson correlation coefficient method, and referring to the classification indicators of China’s National Data Center, this analysis explores the influencing factors of policy target sub-intensity, policy instrument sub-intensity, and policy intensity differences based on 33 specific indicators under four dimensions (economic level [58], population size [59], environment and ecology [60], and energy consumption and production [61]) and nine sub-dimensions (e.g., regional GDP, industrial structure [62], and GHG emissions). The average policy intensity within 23 provinces that had three or more policy texts was used.

In Pearson correlation analysis, the correlation coefficient is a statistic measuring the strength and direction of a linear relationship between two continuous variables. Its value ranges from −1 to 1. A value close to 1 indicates a strong positive correlation, one close to −1 indicates a strong negative correlation, and one close to 0 indicates little to no linear relationship. The p value is the result of a statistical significance test associated with the correlation coefficient. When the p value is less than the significance level (set at 0.05 in this paper), the correlation coefficient is generally considered statistically significant. When the p value is greater than or equal to the significance level, the correlation coefficient is considered statistically insignificant. Relevant data were sourced from China’s National Data Center, the Institute of Public & Environmental Affairs (IPE), and the China Energy Statistical Yearbook. Pearson correlation analysis results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

The correlation analysis of policy intensities.

The correlation analysis results show that five indicators under the economic level dimension exhibited negative correlations with policy intensity, which aligns with existing international research. Studies on European countries indicate that an increase in the Environmental Policy Stringency (EPS) index leads to a decline in overall economic growth and exerts a significant negative impact on the industrial sector [63]. This negative correlation also reflects the stage characteristics of the environmental Kuznets curve [64]. During the high-quality economic development stage, the industrial structure shifts toward services and technology-intensive sectors, energy efficiency improves, endogenous motivation for carbon reduction strengthens, and reliance on high-intensity policies decreases. When economic development surpasses a certain threshold, market mechanisms and technological innovation become the main drivers of emission reduction, and legal instruments gradually give way to market-based instruments. Existing research has pointed out structural imbalances in China’s ESG policy instruments [65], whereas this study indicates that the dynamic optimization mechanism of carbon peak policy instruments is key to achieving the SDGs and is highly consistent with the core pathways advocated by SDG 9 and SDG 12, which promote green growth through technological innovation and market signals.

Kerosene, as a core component of aviation fuel, reflects the level of regional economic participation in globalization. The negative correlation with kerosene consumption suggests that regions with high kerosene consumption shares may already have a cleaner energy system foundation, shifting their policy focus toward technological upgrading rather than intensity control. One of the core directions of such upgrading lies precisely in the development of sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), which can directly replace traditional aviation kerosene [66]. The feedstocks, production technologies, and policy frameworks for SAF have become focal points in current global research on aviation decarbonization [67]. This policy pathway, centered on clean energy technology innovation and substitution, directly serves the objectives of SDG 7: providing viable alternatives to fossil fuels while ensuring global connectivity and achieving deep emission reductions [68].

The uniform negative correlations observed among the policy instrument intensity, policy target intensity, and policy intensity across relevant indicators reveal a structurally coupled relationship among “instrument-target-intensity” within the carbon peak policy system. This structure is not static but characterized by profound internal interactions. As recent studies caution, neglecting the synergistic and trade-off effects between policies will significantly undermine or even delay the achievement of carbon neutrality goals [69]. Therefore, this uniform negative correlation does not simply indicate a decline in intensity but is more likely a reflection of adaptive structural adjustments within the policy system, embodying the pursuit of pragmatic sustainability and policy portfolio efficiency.

Moreover, in multi-level climate governance, economically developed regions tend to employ market-based instruments to guide low-carbon transition. The logic of such differentiated policy implementation essentially aligns policy interventions with local capacities, resource endowments, and developmental stages, thereby synergistically advancing carbon peaking and sustainable development at the national level with the lowest socioeconomic cost. This precisely embodies the core of pragmatic sustainability in policy implementation, and this finding is inherently consistent with international research conclusions on the heterogeneity of SDG synergistic contributions [70]. Differentiated policy implementation effectively coordinates multiple goals in practice, including SDG7, SDG9, and SDG12, while also providing a policy pathway for implementing SDG13 that balances equity and feasibility. This resonates with a recent national-level empirical study, which confirmed the heterogeneity in SDG priorities across Chinese provinces and emphasized that targeted local policies are crucial for achieving coordinated progress at the national level [71]. These findings not only resonate with the IPCC’s principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities” but also offer empirical evidence from China’s policy practice for developing countries to formulate nationally determined contributions (NDCs) suited to their own development realities [72].

5. Conclusions

5.1. Key Findings

By integrating natural language processing with machine learning, this study systematically quantified the intensity of carbon peaking policies from the two dimensions of policy targets and instruments. The main findings are as follows. (1) National and provincial policies focus on system building, while municipal and county policies concentrate on implementation areas such as the architecture, ecology, and project. (2) The number of legal instruments decreased with lower administrative levels, while supervision instruments increased, reflecting the strengthening of grassroots oversight and social participation mechanisms and supporting adaptive governance for SDG 13. (3) Policy target analysis (TF-IDF+SVM, accuracy rate of 87%) showed that central targets are more flexible, while local targets are more specific, demonstrating a localized response to the SDGs. (4) Policy intensity exhibited a top-down decreasing trend, but the municipal and county levels showed enhanced intensities in livelihood-related areas, reflecting innovation and initiative in local implementation. (5) Among the Ten Major Actions, the targets for energy transformation were the most explicit ones (SDG 7), while those for staggered peaking were the most ambiguous ones, forming a climate governance system characterized by focused priorities and flexible coordination.

5.2. Policy Implications

This study deepens the understanding of China’s multi-level climate governance system and provides important insights for further optimizing policy design to promote achievement of the SDGs.

Firstly, the high consistency of core keywords across policy levels may, to some extent, constrain the capacity for differentiated local responses to the SDGs. In particular, the ladder exhibited the weakest policy intensity, which contrasts with the “common but differentiated responsibilities” principle this action should embody [55]. This echoes the finding by Song et al. (2025) that localization of the SDGs at China’s provincial level exhibits regional development disparities [73]. This suggests that in the next Five-Year Plan, a more flexible target decomposition mechanism needs to be established, allowing local governments to formulate differentiated peaking pathways that better align with local sustainable development needs based on their own development stages, resource endowments, and emission profiles.

Secondly, the gradual attenuation of legal policy instruments with lower administrative levels resonates with the findings of Xiao et al. (2021) [74]. It is recommended to strengthen grassroots law enforcement capacity building to ensure the effective implementation of legal instruments at all levels. Among the Ten Major Actions, the circular economy had the fewest policy instruments. This aligns with the research of Ma et al. (2022), indicating that economic policy instruments persist over time but no longer dominate [75]. It is recommended to enhance the supply of policy instruments for the circular economy and dynamically adjust its instrument structure. Meanwhile, apart from energy transition, the precision of policy targets for most actions is relatively limited. While this preserves space for local innovation, it may also affect the evaluability and implementation effectiveness of policies. We suggest drawing on international experience; in areas with clear technological pathways and well-established data foundations (e.g., renewable energy development and building energy efficiency), more precise quantitative targets should be promoted, and in areas involving multi-stakeholder coordination which are still underexplored (e.g., green consumption and ecological carbon sinks), appropriate flexibility can be maintained by using target ranges or dynamic adjustment mechanisms to balance policy certainty and social acceptability.

Furthermore, the policy intensity exhibited a top-down decreasing trend, which aligns with the “hierarchical decay” phenomenon in policy diffusion theory [57]. However, from the perspective of pragmatic sustainability, this trend precisely reflects the dynamic adjustment logic within the multi-level governance system; the stronger policy target intensity at the provincial level compared with the central level demonstrates the proactive transformative capacity of local governments in implementing sustainable development goals. The enhanced policy intensity at the municipal and county levels in areas such as urban-rural construction and transportation reveals localized innovation by grassroots governments. The innovative practices of local governments may not be fully reflected in the “intensity” metrics derived from policy texts but rather demonstrate strengths in areas such as implementation flexibility and pilot projects. These aspects, which the textual dataset of this study has not fully captured, constitute concrete manifestations of the adaptive governance space advocated by pragmatic sustainability. Therefore, the central-local relationship is not a simple “strong versus weak” dichotomy but rather a governance structure characterized by differentiated complementarity and dynamic synergy in the pragmatic advancement of sustainable development.

Finally, this study found that regional heterogeneity was most pronounced for county-level policies, with their policy intensity distribution range far exceeding those of the provincial and municipal levels. This indicates that grassroots governments are not merely passive responders in policy execution but demonstrate significant adaptability and innovation potential within limited spaces. This finding provides an important supplementary basis for the current carbon peaking pilot layout, which mainly focuses on prefecture-level cities. We recommend that future pilot works place greater emphasis on the participation of county-level units, as they better reflect the diversity of China’s regional development and are closer to the realities of people’s livelihoods and industries. By empowering county-level governments to explore differentiated low-carbon transition pathways, not only can local samples of policy innovation be enriched, but this can also help promote the synergistic implementation of goals such as SDG 11, SDG 12, and SDG 13 in grassroots practice, thereby forming practical experience in sustainable governance at a broader level.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study systematically analyzed the quantitative results of carbon peaking implementation plans, but it still has certain limitations. First, the research was based on publicly available carbon peaking policies, and the obtainable data were limited. Second, the text classification methods used in this paper are relatively simple; future work could introduce more advanced models like GPT and BERT for policy content classification. Finally, policy quantification is only the starting point of policy research; this paper did not conduct an in-depth exploration of policy implementation.

On 24 September 2025, China announced its 2035 Nationally Determined Contribution targets, including net greenhouse gas emissions, at the United Nations Climate Change Summit. In October 2025, China released the proposals for its 15th Five-Year Plan, providing further guidance on carbon peaking. This indicates that in the next five years, China’s carbon peaking policies will further diffuse and innovate, demonstrating China’s firm commitment to promoting sustainable development (especially SDG 12 and SDG 13) through carbon peaking actions. Future research could employ more advanced models to explore carbon peaking policies for key sectors and industries within China’s “1 + N” policy framework, enriching the practical forms of deep integration between carbon peaking and sustainable development. Furthermore, with the increase in low-carbon and carbon peaking pilots, future studies could summarize the innovation and diffusion logic of carbon peaking policies from multiple perspectives, such as administrative pressure transmission, economic gradient drivers, and local governance capacity fit, investigate policy implementation processes, help identify synergies between carbon peaking and the SDGs (e.g., SDG 7 or SDG 9), and promote comprehensive green transformation of economic and social development. Finally, future research could expand the temporal span and geographical scope of policy texts, combine them with the diverse indicator systems of the SDGs, and construct a more comprehensive climate policy evaluation model to provide richer policy insights for the global sustainable transition.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su18010296/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Z. and H.L.; methodology, H.L.; software, M.Z.; validation, M.Z., H.L., and Y.W.; formal analysis, M.Z.; investigation, H.L.; resources, M.Z.; data curation, H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Z.; writing—review and editing, Y.W.; visualization, Y.W.; supervision, M.Z.; project administration, H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The relevant code data used for calculation and analysis in this paper can be obtained from the Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Yufei Wang was employed by the Department for Consulting and Research, Management World Journal. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Michaelowa, A.; Shishlov, I.; Brescia, D. Evolution of International Carbon Markets: Lessons for the Paris Agreement. WIREs Clim. Change 2019, 10, e613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plataniotis, A. Transforming Our World: Interdisciplinary Insights on the Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://egd-report-2023.unsdsn.org/ (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- He, W.; Yang, Y.; Gu, W. A Comparative Analysis of China’s Provincial Carbon Emission Allowances Allocation Schemes by 2030: A Resource Misallocation Perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 361, 132192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, E.; Fraussen, B.; Braun, C. Lead, Link, or Leverage? An Integrative Framework to Assess Different Government Roles in Collaborative Governance Processes across Political Systems. Policy Stud. J. 2025, 53, 971–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunea, A.; Nørbech, I. Does Public Participation Foster Stakeholder Support for Policy Proposals? Evidence from the European Union. Policy Stud. J. 2025, psj.70027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colantone, I.; Di Lonardo, L.; Margalit, Y.; Percoco, M. The Political Consequences of Green Policies: Evidence from Italy. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 2024, 118, 108–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anfinson, K. Capture or Empowerment: Governing Citizens and the Environment in the European Renewable Energy Transition. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 2023, 117, 927–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Ma, X.; Cui, Q.; Liu, J. Does the Low Carbon Transition Impact Urban Resilience? Evidence from China’s Pilot Cities for Carbon Emissions Trading. Res. Sq. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Full Text: Working Guidance for Carbon Dioxide Peaking and Carbon Neutrality in Full and Faithful Implementation of the New Development Philosophy. Available online: https://english.www.gov.cn/policies/latestreleases/202110/25/content_WS61760047c6d0df57f98e3c21.html (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- China Maps Path to Carbon Peak, Neutrality Under New Development Philosophy. Available online: https://english.www.gov.cn/policies/latestreleases/202110/24/content_WS61755fe9c6d0df57f98e3bed.html (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Jiang, X.; Xie, F. Decomposition Analysis of Carbon Emission Drivers and Peaking Pathways for Key Sectors under China’s Dual Carbon Goals: A Case Study of Jiangxi Province, China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.-M.; Chen, K.; Kang, J.-N.; Chen, W.; Wang, X.-Y.; Zhang, X. Policy and Management of Carbon Peaking and Carbon Neutrality: A Literature Review. Engineering 2022, 14, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, R.R.; Li, Z.; Wang, S.; Wang, F.; Fang, K. Multi-Objective Energy Planning for China’s Dual Carbon Goals. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 34, 552–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Full Text: Carbon Peaking and Carbon Neutrality China’s Plans and Solutions. Available online: https://english.www.gov.cn/archive/whitepaper/202511/08/content_WS690ee812c6d00ca5f9a076cd.html (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Fu, C.; Liao, L.; Mo, T.; Chen, X. How China’s Great Bay Area Policies Affect the National Identity of Hong Kong Youth—A Study of a Quasi-Natural Experiment Based on the Difference-in-Differences Model. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantarelli, P.; Belle, N.; Hall, J.L. Information Use in Public Administration and Policy Decision-making: A Research Synthesis. Public Adm. Rev. 2023, 83, 1667–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, R.M.; Hawkins, C.V.; Park, A.Y.S.; Feiock, R.C. Drivers of Policy Instrument Selection for Environmental Management by Local Governments. Public Adm. Rev. 2019, 79, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M. The Impacts of Carbon Trading Policy on China’s Low-Carbon Economy Based on County-Level Perspectives. Energy Policy 2023, 175, 113494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Song, S.; Yang, Y. Driving Restrictions, Traffic Speeds and Carbon Emissions: Evidence from High-Frequency Data. China Econ. Rev. 2022, 74, 101811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabernegg, S.; Bednar-Friedl, B.; Muñoz, P.; Titz, M.; Vogel, J. National Policies for Global Emission Reductions: Effectiveness of Carbon Emission Reductions in International Supply Chains. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 158, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Chen, Y. Impacts of Policies on Innovation in Wind Power Technologies in China. Appl. Energy 2019, 247, 682–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Nie, X.; Wang, H. Are Policy Mixes in Energy Regulation Effective in Curbing Carbon Emissions? Insights from China’s Energy Regulation Policies. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 2024, 43, 1152–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Wang, Q.-C.; Shen, G.Q. The Carbon Emission Implications of Intensive Urban Land Use in Emerging Regions: Insights from Chinese Cities. Urban. Sci. 2024, 8, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Gao, Y.; Li, J.; Su, B.; Chen, Z.; Lin, W. China’s Environmental Policy Intensity for 1978–2019. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y. Harmonizing Existing Climate Change Mitigation Policy Datasets with a Hybrid Machine Learning Approach. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, X.; Wang, C.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, H.; Xia, C. China’s Low-Carbon Policy Intensity Dataset from National- to Prefecture-Level over 2007–2022. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Fu, E.; Yang, S.; Lin, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, J.; Lu, Y.; Wang, J.; Jiang, H. Measuring China’s Policy Stringency on Climate Change for 1954–2022. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaolong, T.; Christensen, T. Leading Groups: Public Sector Reform with Chinese Characteristics in a Post-NPM Era. Int. Public Manag. J. 2023, 26, 66–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, C.; Ji, R.; Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, R.; Wu, M.; Chen, J.; Yang, J. Metricizing Policy Texts: Comprehensive Dataset on China’s Agri-Policy Intensity Spanning 1982–2023. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, S.H.; Augustin, C.; Bethel, A.; Gill, D.; Anzaroot, S.; Brun, J.; DeWilde, B.; Minnich, R.C.; Garside, R.; Masuda, Y.J.; et al. Using Machine Learning to Advance Synthesis and Use of Conservation and Environmental Evidence. Conserv. Biol. 2018, 32, 762–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, J.K.; Sethuraman, S.C.; Cruz, M.V.; Namburu, A.; P., M.; R., N.K.; S, S.I.; Vijayakumar, V. Comprehensive Analysis of Embeddings and Pre-Training in NLP. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2021, 42, 100433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Tang, X.; Yuan, T. Fine-Tuning BERT for Multi-Label Sentiment Analysis in Unbalanced Code-Switching Text. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 193248–193256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, S.A.; Lazaro, L.L.B.; Young, A.F.; Coelho, R.R.A.; Ortega, F.J.M.; Hecksher, C.B.M.C.; Cardoso, J.R.; Ferreira, J.S.W.; Jacobi, P.R.; Junior, A.P.; et al. Assessing the Alignment of Brazilian Local Government Plans with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z. Content Analysis of China’s Environmental Policy Instruments on Promoting Firms’ Environmental Innovation. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 88, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, M.; Fang, X.; Wen, L.; Guang, F.; Zhang, Y. The Heterogeneous Effects of Different Environmental Policy Instruments on Green Technology Innovation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Mishra, A.K.; Ni, M. Effects of Agricultural Subsidy Policy Adjustment on Carbon Emissions: A Quasi-Natural Experiment in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 487, 144603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xue, L.; Zhou, Y. How Do Low-Carbon Policies Promote Green Diffusion among Alliance-Based Firms in China? An Evolutionary-Game Model of Complex Networks. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 210, 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Qin, Q.; Wei, Y.-M. China’s Distributed Energy Policies: Evolution, Instruments and Recommendation. Energy Policy 2019, 125, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager, N.W.; Newig, J.; Challies, E.; Kochskämper, E. Pathways to Implementation: Evidence on How Participation in Environmental Governance Impacts on Environmental Outcomes. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2020, 30, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhu, X.; Chen, J.; Jiang, F. Environmental Regulations, Environmental Governance Efficiency and the Green Transformation of China’s Iron and Steel Enterprises. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 165, 106397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firebanks-Quevedo, D.; Planas, J.; Buckingham, K.; Taylor, C.; Silva, D.; Naydenova, G.; Zamora-Cristales, R. Using machine learning to identify incentives in forestry policy: Towards a new paradigm in policy analysis. For. Policy Econ. 2022, 134, 102624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbah, T.; Selamat, A.; Selamat, M.H.; Al-Anzi, F.S.; Viedma, E.H.; Krejcar, O.; Fujita, H. Modified Frequency-Based Term Weighting Schemes for Text Classification. Appl. Soft Comput. 2017, 58, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passalis, N. Learning Bag-of-Embedded-Words Representations for Textual Information Retrieval. Pattern Recognit. 2018, 81, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, A.; Jenamani, M.; Thakkar, J.J. Senti-N-Gram: An n -Gram Lexicon for Sentiment Analysis. Expert. Syst. Appl. 2018, 103, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiri Harzevili, N.; Alizadeh, S.H. Mixture of Latent Multinomial Naive Bayes Classifier. Appl. Soft Comput. 2018, 69, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wankhade, M.; Rao, A.C.S.; Kulkarni, C. A Survey on Sentiment Analysis Methods, Applications, and Challenges. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2022, 55, 5731–5780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saura, J.R.; Palacios-Marqués, D.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D. Exploring the Boundaries of Open Innovation: Evidence from Social Media Mining. Technovation 2023, 119, 102447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, F.; Li, R.; Sun, J. Does Artificial Intelligence Promote Energy Transition and Curb Carbon Emissions? The Role of Trade Openness. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 447, 141298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holladay, J.S.; Mohsin, M.; Pradhan, S. Environmental Policy Instrument Choice and International Trade. Environ. Resource Econ. 2019, 74, 1585–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhu, Y. Can China’s Energy Policies Achieve the “Dual Carbon” Goal? A Multi-Dimensional Analysis Based on Policy Text Tools. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casady, C.B.; Petersen, O.H.; Brogaard, L. Public Procurement Failure: The Role of Transaction Costs and Government Capacity in Procurement Cancellations. Public Manag. Rev. 2023, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.; Broughton, K.; Broadhurst, K.; Ferreira, J. Collaborative Innovation in a Local Authority – ‘Local Economic Development-by-Project’? Public Manag. Rev. 2024, 26, 1405–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Ding, X. Textual Analysis of China’s Environmental Policies from the Perspective of Policy Instruments. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, R.; Cui, T. Facilitating Inter-Municipal Collaboration through Mandated Collaborative Platform: Evidence from Regional Environmental Protection in China. Public Manag. Rev. 2024, 26, 1684–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. In Proceedings of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3–14 June 1992; Available online: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/united-nations-framework-convention-on-climate-change (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Cinar, E.; Simms, C.; Trott, P.; Demircioglu, M.A. Public Sector Innovation in Context: A Comparative Study of Innovation Types. Public Manag. Rev. 2024, 26, 265–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Q.; Wen, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Fan, B. Leveraging Social Media for New Energy Vehicle Policy Diffusion in China: A Central-Local Government Interaction Analysis. Transp. Res. Part. A Policy Pract. 2025, 195, 104459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magazzino, C.; Mele, M.; Schneider, N. A Machine Learning Approach on the Relationship among Solar and Wind Energy Production, Coal Consumption, GDP, and CO2 Emissions. Renew. Energy 2021, 167, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Ma, T. Assessing Spatiotemporal Characteristics and Driving Factors of Urban Public Buildings Carbon Emissions in China: An Approach Based on LMDI Analysis. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Yu, J. Determinants and Their Spatial Heterogeneity of Carbon Emissions in Resource-Based Cities, China. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wang, H. Do Provincial Energy Policies and Energy Intensity Targets Help Reduce CO2 Emissions? Evidence from China. Energy 2022, 245, 123275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, T.; Cao, R.; Xia, N.; Hu, X.; Cai, W.; Liu, B. Spatial Correlation Network Structure of China’s Building Carbon Emissions and Its Driving Factors: A Social Network Analysis Method. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 320, 115808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorus, M.S. Do Tight Environmental Regulations Cause Economic Contraction? Panel Evidence from the European Countries. Nat. Resour. Forum 2024, 48, 663–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, X. Renewable Energy, Carbon Emission and Economic Growth: A Revised Environmental Kuznets Curve Perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 1338–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, H. Evaluation of China’s ESG Policy Texts Based on the “Instrument-Theme-Subject” Framework. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wandelt, S.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, X. Sustainable Aviation Fuels: A Meta-Review of Surveys and Key Challenges. J. Air Transp. Res. Soc. 2025, 4, 100056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, M.J.; Machado, P.G.; Da Silva, A.V.; Saltar, Y.; Ribeiro, C.O.; Nascimento, C.A.O.; Dowling, A.W. Sustainable Aviation Fuel Technologies, Costs, Emissions, Policies, and Markets: A Critical Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 449, 141472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahabuddin, M.; Alam, M.T.; Krishna, B.B.; Bhaskar, T.; Perkins, G. A Review on the Production of Renewable Aviation Fuels from the Gasification of Biomass and Residual Wastes. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 312, 123596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Du, M.; Yang, L.; Cui, Q.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Zhu, N.; Li, Y.; Jiang, C.; Zhou, P.; et al. Mitigation Policies Interactions Delay the Achievement of Carbon Neutrality in China. Nat. Clim. Change 2025, 15, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Zhang, Y. Quantifying Global Cooperation in the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Q.; Wu, C.; Chen, F.; Liu, J.; Pradhan, P.; Bryan, B.A.; Schaubroeck, T.; Carrasco, L.R.; Gonsamo, A.; Li, Y.; et al. Intranational Synergies and Trade-Offs Reveal Common and Differentiated Priorities of Sustainable Development Goals in China. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills-Novoa, M.; Liverman, D.M. Nationally Determined Contributions: Material Climate Commitments and Discursive Positioning in the NDCs. WIREs Clim. Change 2019, 10, e589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Cao, S.; Du, M.; Lu, L.; Guo, H.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, X. Provincial Localization Framework for SDGs in China: Enhancing Support for Sustainable Governance. Appl. Geogr. 2025, 175, 103505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Zhu, X. Bureaucratic Control and Strategic Compliance: How Do Subnational Governments Implement Central Guidelines in China? J. Public. Adm. Res. Theory 2022, 32, 342–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Hoppe, T.; De Jong, M. Policy Accumulation in China: A Longitudinal Analysis of Circular Economy Initiatives. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 34, 490–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.