Abstract

This study aimed to assess various social–ecological traps of hilsa shad (Tenualosa ilisha) fisheries and to investigate the factors that significantly impact livelihood adaptation strategies during the ban period, based on fieldwork in coastal fishing communities. To collect empirical data, a total of 247 in-depth interviews were conducted using a semi-structured questionnaire along with six focus group discussions, oral history, and ten key informant interviews in the Chattogram and Patuakhali districts of Bangladesh. A conceptual framework derived from a strategy for reducing poverty, known as the Sustainable Livelihood Approach (SLA), is applied to determine the livelihood outcomes of hilsa fishers. The results showed that low income (<5000 BDT/month), high interest in loans from dadondar (lender) (10–12%) and aratdar (lessor of the vessel) (5%), high harvesting costs, an increasing number of hilsa fishermen, and intergenerational traps (81.78%) are creating social–ecological traps (SETs) in the hilsa fishery. The significant factors affecting the choice of adaptation strategies include family members, training facilities, home ownership, and belonging to a formal society. Apart from fighting against some extreme climate events, negative feedback comes from the absence of cold storage facilities, illegal use of fishing nets, frequent ban seasons, ignorance of conservation laws, limited opportunities for alternative occupations, and poor supply of drinking water. Hilsa fishermen in these regions depended on aratdar and dadondar for their financial support, which resulted in lower prices than the prevailing market prices. To escape from the SETs, this study identifies potential alternatives, such as government–community finance schemes, the promotion of alternative livelihoods, opportunities for technical education of their children, improvement of the local framework, and strong cooperation between local stakeholders and management authorities that are necessary to maintain the sustainability of hilsa fisheries.

1. Introduction

The hilsa shad (Tenualosa ilisha) is the National Fish of Bangladesh and was announced as the Geographical Indication (GI) product of Bangladesh by the Department of Patents, Designs and Trademarks (DPDT) in 2017 [1]. The hilsa fishery is valued at USD 1.3 billion annually, which is more than 1% of Bangladesh’s overall GDP [2]. Bangladesh leads the world in hilsa fishing. The country caught 550,428 metric tons, making up about 86% of the total catch among the top hilsa-producing countries. Approximately 11.91% of the country’s total fish output and 56.81% of its overall marine catch are accounted for by it, making it an important contributor to food security, employment, and cultural heritage [1]. An annual hilsa output was roughly 215 thousand tons per year, but given recent yields and market sales were average around USD 12/kg, the real market price may be 10 times higher [3,4]. Moreover, Mohammed et al. (2016) [5] counted the fishery’s non-consumptive value, which was from USD 167.5 million to USD 355.7 million per year. Nearly 500,000 full-time fishermen depend significantly on the hilsa fishery, which is mostly an artisanal gillnet fishing for their livelihood [5]. They have a few other possibilities for obtaining a living. In addition, a large number of people work in ice factories, net manufacturing facilities, making boats, nets, ropes, floats, and baskets. Consequently, the broader hilsa sector is thought to employ about 10 million people [6]. Bangladesh used to have an abundance of hilsa, and Bengali culture regards the fish as having historical value. Population increase has been a major factor in the overfishing of coastal fisheries since the 1970s. The total annual hilsa catch started to drop quickly in the early 1980s, and by 2003, the yield was 0.136 million MT [1]. The yields of hilsa in inland waterways have gradually decreased as a result of over-exploitation and collection of juveniles and brood fish, locally referred to as “jatka” [7].

A number of problems, including overexploitation, poverty, and difficulty shifting to new livelihoods, threaten the long-term viability of hilsa fisheries [5]. Fishermen are considered the poorest of the poor, living hand to mouth, and are one of Bangladesh’s most vulnerable communities [8,9]. The annual per capita income of fishermen is BDT 2442, which is approximately 70% less than the per capita income of the country [10]. Hilsa fishermen have greater hardships than other fishermen because of seasonality, frequent natural calamities, and limitations in hilsa capture during the ban period. As a result, they cannot earn enough money to pay for their necessities [5,11]. The poverty cycle adds to the overexploitation of hilsa fisheries because fishermen frequently resort to harmful practices to maximize short-term gains to meet their basic needs. In recent years, the decrease in hilsa populations has been attributed to various factors, including technical advancements, increased fishing pressure, growing market demand, and inadequate regulatory measures.

The social–ecological trap in small-scale fishing describes how poverty and resource exploitation interact to create conditions that are not in line with popular normative concepts of development [12]. By viewing people as components of social and ecological systems, it highlights the relationships between individuals and the natural environment [13]. Many contexts, including small-scale fishers in eastern Africa [10] and Cameroon [14], and the lobster industry of the eastern United States and other locations [15], have demonstrated the effectiveness of the trap lens.

However, the social–ecological trap lens has not been applied to Bangladeshi fisheries, despite recent research proposing that social–ecological traps are common in small-scale fisheries in Africa, given shifting economic, social, political, and environmental conditions [10,14,16]. Numerous studies addressing the biological and economic aspects of hilsa fisheries have revealed a significant gap in the understanding of the complex interplay of social and ecological factors that trap hilsa fishers in cycles of poverty and resource depletion. This study aims to unveil these traps through a social–ecological lens, exploring how economic, social, and environmental dimensions intertwine to perpetuate vulnerability among hilsa fishing communities in Bangladesh. It would be helpful to discuss how fishermen’s experiences with poverty restrict their capacity to identify with or adapt to new or alternative ways of subsistence.

By adopting an integrated approach, this study seeks to provide a holistic understanding of the persistent challenges faced by hilsa fishers. It examines how socioeconomic constraints, such as limited access to education, indebtedness, and market inequities, intersect with ecological pressures, including declining fish stocks and habitat degradation. Through this lens, the study not only highlights the immediate issues but also delves into the underlying systemic factors that sustain these traps. Ultimately, this study contributes to the development of sustainable management strategies that address both social and ecological dimensions, and foster resilience and empowerment among hilsa fishing communities. This research attempts to provide answers to the following important concerns based on the identified issues faced by hilsa fishers:

- What social–ecological traps exist in hilsa fisheries?

- How do socio-ecological traps relate to the livelihood outcomes of hilsa fishermen?

- What elements affected livelihood adaptation strategies during the ban?

Theoretical Framework

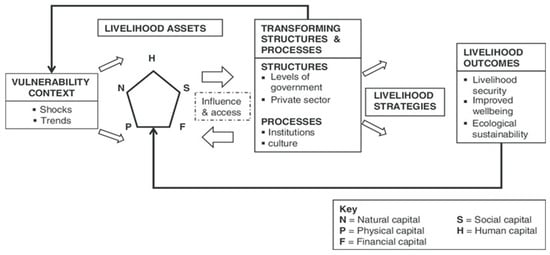

This study uses the Sustainable Livelihoods Approach (SLA), a people-focused framework commonly used to analyze and develop poverty-reduction and rural development efforts [17]. The SLA includes several connected parts that help explain the different and complex ways people and households make a living. These parts include the vulnerability context, which affects access to and use of livelihood assets such as social, natural, human, physical, and financial capital. It also considers the policies, institutions, and processes that influence how these assets are turned into livelihood strategies and outcomes [18,19] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The sustainable livelihood framework (Adapted from DFID, 1999) [18].

The SLA framework highlights key influences and feedback among these elements, illustrating how multiple factors interact to shape livelihood outcomes [18]. According to DFID (1999) [18], a livelihood is considered sustainable if it can cope with and recover from stresses and shocks, maintain or enhance its asset base and capabilities, and do so without undermining the natural resource base. Consequently, household well-being depends on the combined effects of skills, knowledge, assets, preferences, and access to resources [20].

Within the SLA framework, the vulnerability context—including shocks, long-term trends, and seasonal fluctuations—plays a critical role in shaping livelihood outcomes. These factors are typically beyond individual control and directly affect livelihood assets, particularly human and financial capital, thereby influencing the range of feasible livelihood strategies. While certain contextual changes, such as technological innovation, may benefit poor households, recurrent shocks and chronic vulnerabilities often constrain adaptive capacity and limit opportunities for livelihood diversification [18]. At the same time, institutions and policies significantly influence asset accumulation by generating new assets (e.g., technology), regulating access to existing assets (e.g., property rights), and shaping returns to livelihood strategies through governance, taxation, and market structures [18].

According to Allison and Ellis (2001), SLA helps to describe institutional and social effects and uncertainties [21]. Importantly, limited access to assets under conditions of persistence. When people have limited access to assets and face ongoing challenges, it can create negative cycles. These cycles can force people to rely too much on natural resources and harm their long-term well-being. According to Cinner (2011) and Laborde et al. (2016) [10,14], these patterns are called social–ecological traps (SETs), in which the links between social and ecological systems keep households stuck in difficult situations, such as poverty traps, that can last for generations. In these cases, low human capital, repeated shocks, and weak institutional support make it hard for families to build assets, which keeps the cycle of poverty going [18,22]. Its application to small-scale fisheries and their entanglement with social–ecological traps remains limited [21,23,24]. This study, therefore, employs the SLA framework to examine the social, natural, and economic sustainability of the hilsa fishery, while explicitly linking livelihood outcomes to feedback mechanisms that may entrench households in social–ecological traps.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Areas

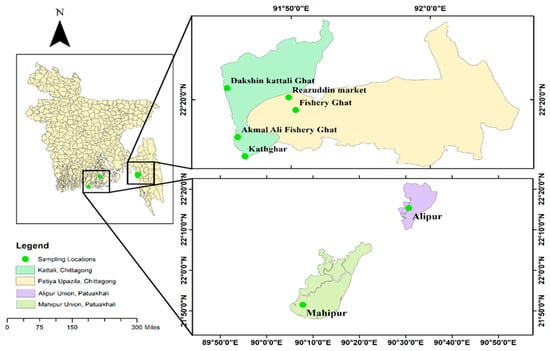

This study focused on two fishing communities, four fish landing centers (Fisheryghat, Dakkhin Kattolighat, Ali akmol ghat, Kathghor), and a local market (Riazuddin Market) in Chattogram districts and the Mohipur and Alipur unions of Patuakhali districts of Bangladesh (Figure 2). The majority of the community members in this region are directly or indirectly involved in hilsa fishing.

Figure 2.

Location of the study areas in the Chattogram and Patuakhali districts of Bangladesh (ArcGIS 10.8).

2.2. Methods

From October 2023 to March 2024, 247 hilsa fishermen, aratdars, paikers, retailers, and boat owners were chosen randomly from our study areas. The study adopted a mixed sampling approach, where respondents were initially identified through purposive sampling with the help of community leaders, followed by simple random sampling to select 247 hilsa fishers and related stakeholders. The mixed-method consisted of focus group talks (n = 6) with a checklist, key informant interviews (n = 10), individual interviews (N = 247), and oral history using semi-structured questionnaires (Table 1). Both primary and secondary data were used in this study. In accordance with the Sustainable Livelihood Approach (SLA), the questionnaire was divided into nine sections: human capital, physical capital, financial capital, natural capital, social capital, livelihood strategies, vulnerability context, transforming structures and processes, and livelihood outcomes. Community leaders who were currently involved in hilsa fishing, such as aratdar, the owner of a boat, identified the respondents. The respondents, both male and female, provided their opinions based on their previous and current hilsa fishing experiences. In addition to the collection of qualitative and quantitative data, cross-sectional analysis also facilitated the analysis of the relationships between different socioeconomic variables.

Table 1.

Data collection method with number of respondents.

The data from the questionnaire were entered into an Excel sheet in Microsoft for analysis. Additionally, IBM SPSS version 2022 was used to statistically analyze the collected data. The SPSS data sheet distinguished between nominal, ordinal, and scale data by stating the measurement scale for each variable. Tests for data homogeneity and normality were also looked at. In accordance with the goals of the study, projected tables and graphs were then developed. The SLA framework and the social–ecological traps framework served as the foundation for the preparation of the results section. A heuristic social–ecological trap in fisheries model developed by Cinner (2011) [10] that highlights the factors that affect social–ecological traps in fisheries. Additionally, the binomial logistic model was used for data analysis. It is an acceptable model, and the dependent variable is dummy (i.e., whether or not to employ coping or adaptation mechanisms to lessen the unfavorable circumstances during the banned period and variability; yes = 1, 0 = otherwise).

where is the odds (likelihoods) ratio, α is the intercept, β1, β2…βn are the coefficients to be estimated, and x1, x2…xn denote the set of explanatory variables related to socio-demographic, economic, and infrastructural factors hypothesized to influence the choice of coping and adaptation measures during the ban period and variability [25]. Henry Garret’s ranking technique was used to evaluate the constraints faced by the fishers. An in-depth interview schedule was also used to collect data on the reasons perceived by the fishers regarding the decline in the hilsa fishery. The orders of merit given by the respondents were converted into a rank by using the formula. Garrett’s ranking method was applied to determine the respondent’s most important influencing factor. According to this methodology, participants were asked to rank each element, and the results of that ranking were then translated into a score value using the formula below:

where Rij is the rank given for the ith variable by the jth respondent, and Nj is the number of variables ranked by jth respondent.

With the help of Garrett’s Ranking Table, the percent position estimated was converted into scores by referring to the table given by Garret and Woodworth (1969) [26]. The individual scores for each factor were then totaled, and the total value of the scores, as well as the mean values of the scores, were computed. According to Dhanavandan (2016) [27], the components with the greatest mean value were deemed to be the most significant.

3. Results

3.1. Livelihood Capitals

3.1.1. Human Capital

Hilsa fishers are knowledgeable and skillful in hilsa fishing because they have been engaged in hilsa fishing for a long time. Approximately 37.25% of fishers had been engaged in hilsa fishing for 31–40 years, followed by 29.96% for 20–30 years and 20.65% for more than 40 years (Table 2). A total of 42.51% of respondents said they had the opportunity to participate in hilsa fishing awareness-building training arranged by both the government and non-governmental organizations (GOs and NGOs). In addition to their household activities, women engage in a variety of different sources of income. A total of 64.37% of them worked on household activities, while the remaining employment included working in garments (18.22%), dry fish sorting (9.31%), and buffalo rearing (4.05%). Only a small percentage of women reared cows (1.21%), and some were shopkeepers (2.83%). Although they cannot always support their children, 49.80% of hilsa fishermen were attempting to encourage their children to attend school. Along with their parents, children engaged in day labor activities, including sorting (16.60%), net-making (10.12%), boat-making (6.07%), and fishing (17.41%). Approximately 75.71% of the participants agreed that they could arrange their three meals a day; however, in times of crisis, some individuals may have to settle for two meals (17.41%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of the human capital and assets of the studied hilsa fishers.

3.1.2. Physical Capital

Hilsa fishermen’s homes and living conditions were not good at all. They lived in small spaces with too many families. Only 11.34% of the respondents said they had house ownership, whereas the majority of fishermen (88.66%) lived in rented houses. In addition, 7.69% of fishermen had additional land (Table 3). A community’s housing conditions indicate its residents’ level of well-being or financial status. The materials used to build their homes differed depending on their financial situation and the community in which they lived. The findings showed that while a small percentage of respondents (2.43%) lived in houses made of bamboo with plastic sack roofs, walls, and earth floors, approximately 53.04% lived in homes with iron-sheet roofs, walls, and floors. The open areas in front of the houses were hard. A total of 85.02% of the respondents owned private latrines. Approximately 29.15% of families had installed solar systems, while 50.20% of hilsa fishing families had electricity facilities. About 58.30% of the respondents said that the transportation facilities were in good condition, while 22.67% said they were poor or extremely poor (19.03%). Supply water comprised the majority of the sources of drinking water (52.23%); other sources included tube wells (31.58%), pump water (10.53%), and filtered surface water (5.67%). The Upazilla Clinic, district hospitals, and local pharmacists were the known sources of treatment. In cases of severe illness, they received treatment from qualified doctors (1.62%); in other cases, they felt at ease with local pharmacy doctors (39.68%). Overall, 27.53% of patients received care from the Upazilla clinic, and 31.17% from the district hospital. Approximately 48.58% of people reported owning a boat that they used for hilsa fishing, which is approximately the same as the hire rate (51.42%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

The physical asset conditions in the study areas (n = 247).

3.1.3. Natural Capital

Season and tides have a major influence on hilsa availability. According to the responders, hilsa are primarily found in the rainy season (June, July, August, and September) and dull season (February, March, and April). A respondent said that, “Hilsa are mostly found in the rainy season and the salinity of the water is very low in this season. However, in the dry season, the salinity is very high, which creates obstacles in fishing as the mesh fills with salt. The hilsa of the rainy season is very tasty compared to the dry season because of low salinity.”

Most fishermen (65.89%) reported that they caught hilsa between 21 and 25 cm in size. Nearly 84% of the respondents said that the number of hilsa fishermen was rising, which was the primary cause of the declining hilsa stock. In total, 85.53% of the respondents agreed that there has been a relative decline in the availability of hilsa fish during the last 10 years. Additionally, they offer recommendations for improving sustainable management and hilsa abundance. The prohibition season had to be carefully adhered to, and the use of illegal fishing nets had to end. There is an inverse relationship between the number of hilsa fishermen and stocks. They also need to be controlled by limiting fishing access and establishing an appropriate licensing system. It is best not to catch the small hilsa (less than 14 cm). Furthermore, to preserve and restore this fishery, significant institutional and administrative support is required. A total of 52.28% of the respondents said that the primary threat to hilsa stock was the capture of undersized fish, followed by illegal fishing at 49%.

3.1.4. Social Capital

Several NGOs run their businesses and promote community welfare for very little profit. A few donor groups have attempted to improve the current situation of hilsa fishermen and other community members. Certain organizations carried out their operations with the community’s well-being in mind. A large number of fishermen (48.22%) were connected with non-governmental and social organizations, such as the Swapnil Bright Foundation. These organizations provided loans to hilsa fishermen, awareness-raising and training, sanitary latrines, clean drinking water, relief supplies during extreme weather events, primary education institutions, and household materials for house construction and repair.

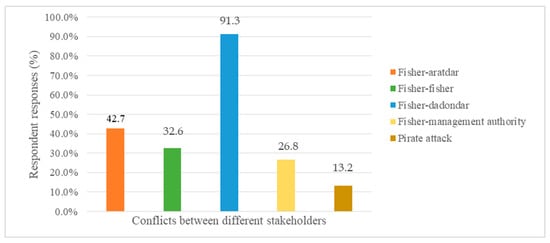

About 74.49% of respondents said they did not belong to a formal society. Most respondents thought that conflicts between and within the community were a common phenomenon. The primary and most frequent disagreements occurred because of resource use. Approximately 91.3% of conflicts between fishers and dadondar occurred due to failure to return money (Figure 3). Disputes between fishermen and aratdars (42.7%) also occurred because of the giving of percentages of the sale. Conflicts between fishermen occurred when one placed his nets or was caught in another’s common area (32.6%). Disagreements occurred between the fisher and the management authority (26.8%) whenever the field officer requested payment for the use of illegal fishing nets or for fishing during the banned period. Due to pirate attacks, conflicts between fishers and robberies (13.2%) also occurred (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Conflicts arise among the different stakeholders during resource utilization.

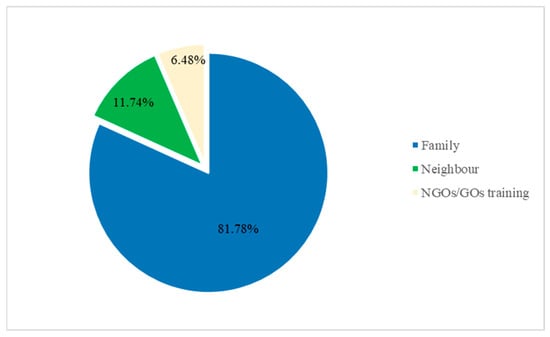

When asked why they were involved in hilsa fishing, many of them mentioned that their parents had done it and now they were. They were involved in fishing with their families and parents (81.78%), while others opined that they were introduced by their neighbors (11.74%). Some respondents engaged in NGO/GO training (6.48%) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Reasons for involvement in hilsa fishing of the respondents in the study areas.

3.1.5. Financial Capital

The team members of hilsa fishing were usually formed by 5–7 members for daily fishing and 15–21 members for 15-day trips. The fishers of Dakkhin kattoli, Ali akmol ghat, and Kathghor were mainly involved in daily fishing, but fishers in the fishery ghat, Alipur, and Mahipur Union were mainly involved in 15-day fishing trips. They were fishing 2–3 times per day. They started their journey during high tide and returned to the landing center at low tide. The respondents said that the total catch in a day had no definite volume; it mainly ranged from 1 to 1.5 mounds, but about 15–16 years ago, they found approximately 8–10 mounds. For 15-day trips, they said that their total catch was about 10–20 mounds, but about 20 years ago, it was about 70–80 mounds. The total income also varied according to the total catch per day.

They had some determining costs: hiring a boat cost about 18–20 thousand per month, but 48.58% respondents had their own boat; food cost about 4–5 thousand per day, depending on the number of team members; diesel cost was 3.5–20 thousand; and transportation costs varied. After fishing, they sold to aratdar (43.72%) and dadondar (19.43%) at relatively lower prices (Table 4). When they go fishing, they borrow money from aratdar (48.18%) and dadondar (17.81%) to cover trip costs and family needs, due to a lack of savings and a sufficient source of money. Hilsa fishers have no other way to sell their catch other than aratdar and dadondar. Both the river and road transport systems were used for transportation purposes. They typically used the riverway for hilsa collection and roads for other purposes. Most of the respondents (90.69%) reported that their income level had decreased over the past ten years (Table 4).

Table 4.

Financial assets of the respondents in the study areas.

Approximately 65.92% of those surveyed stated that the hilsa accounts for 50% of their overall income. Respondents who said “no,” meaning that hilsa fishing was not profitable at this time, but about 49.75% of respondents agreed that it was profitable. It was profitable in the past, but the number of hilsa fishermen has increased. They stated that undersized hilsa catches and the use of illegal fishing nets are further factors contributing to this reduction in profitability. They use alternative sources of income to support themselves, but this occasionally leads to unexpected outcomes. Relatively few respondents said that their primary job loss caused food insecurity at this time.

3.2. Vulnerability Context

Hilsa fishing is challenging, and fishermen struggle to make a living there. They fall into three primary categories of difficulty: seasonality, shocks, and trends (Table 5). Natural calamities occur year-round in the study areas, including cyclones, storm surges, and floods. Uncertainties around hilsa fishery availability, along with frequent ban periods, are appalling for income and livelihoods. Fisherfolk are acquainted with issues such as reduced income, food shortages, lack of health facilities, lack of pure drinking water, high interest in loans, and corruption among management authorities.

Table 5.

Vulnerability contexts faced by the hilsa fishers in the study areas.

3.3. Transforming Structures and Processes

Some components include policies, institutions, culture, and the job market, all of which play an important role in fishing and hilsa-fisher communities in this region (Table 6). Policies regarding fishing and hilsa fishers are formulated to improve livelihoods and maintain the sea ecosystem. New policies are formed to meet the situation demand. Some existing policies include a 65-day ban on all types of fishing in the Bay of Bengal, imposing a 22-day ban on hilsa fishing at the peak spawning period of hilsa, imposing a seven-month ban (November–May) on catching hilsa fry, and restricting the use of illegal fishing nets such as behundi jal, moshari jal, ber jal, current jal, chatjal, gara jal, and khuti jal to protect the ecosystem. These institutions included GOs, NGOs, and social community groups. GOs make necessary rules and regulations and enforce them at the root level. The government has taken different initiatives to increase and sustain hilsa production. The major activities were formulating and implementing the “Hilsa Fisheries Management Action Plan”, developing the livelihood of hilsa fishermen by giving VGF (Vulnerable Group Feeding) and AIG (Alternative Income Generating) (DoF, 2022) [1]. To increase public awareness regarding the conservation and protection of brood hilsa and jatka, DoF conducts different types of activities such as posters, leaflet distribution, decoration of fish markets, arat, fishery ghats with banners, festoons, and arranging awareness programs with fishermen and other stakeholders. The amount of VGF (rice) is 10–40 kg per family per month.

Table 6.

Components of transforming structures and processes with examples.

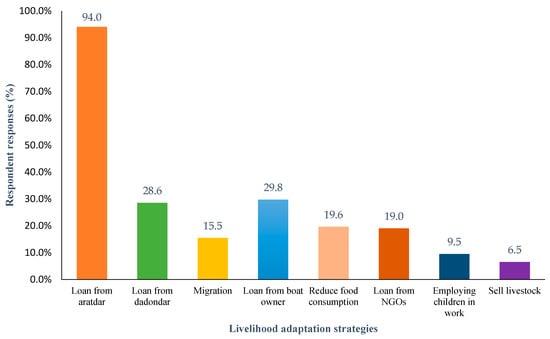

3.4. Livelihood Strategies

The people of coastal regions are fighters, as they always fight natural disasters and extreme climatic events. They accept that they have to survive extreme climate events, as they face such events every 2 to 3 years. Some adaptation strategies are also common in adapting to crisis situations. Loans from aratdar were the first adaptation strategy for them, as 94.0% of respondents agreed with that response (Figure 5). The second was money lending from boat owners (29.8%) to address their crisis conditions. As they had no earning option, the gateway from the crisis was to borrow money from the moneylender to buy family needs. Other moneylenders were dadondar (28.6%) and NGOs (19.0%). Different NGOs provide financial assistance to people in crisis conditions and recover the funds with interest. Hilsa fishers sometimes did not even imagine how NGOs were taking in huge sums of money back, capitalizing on their crisis. Other adaptation strategies included the employment of children at work (9.5%), migration towards cities (15.5%), and selling livestock (6.5%) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Percentage of respondents’ responses on livelihood adaptation strategies in times of crisis situations.

Factors Affecting Livelihood Adaptation in Ban Period

The final results of the Binary Logistic Regression Model’s estimated variables are presented in Table 7. Age, education, experience, family members, monthly income (BDT), training, having own boats, having house ownership, having additional land, and belonging to a formal family were independent variables. Livelihood adaptation strategies were the dependent variables. Age (<26), education (illiterate), experience (<20), family members (<5), monthly income (BDT) (<5000), training (No), having own boats (No), having house ownership (No), having additional land (No), and belonging to the formal family (No) were selected as reference categories. Some results were statistically significant (p < 0.01 and p < 0.05) (Table 7). The results showed that family members belonging to the 11–15 category were statistically significant (p < 0.05), and the probability of adaptation during the ban period in this category was 2.755 times greater than that in the reference category. There was a significant difference (p < 0.05) in the training variable, indicating that the probability of adapting to training was 2.894 times greater than the reference category (who did not undergo training). The probability of adapting to the ban period with house ownership was 4.870 times greater than that of those who did not. The probability of adapting to the crisis situation of the respondents who belonged to formal society was 0.271 times greater than that of those who did not (Table 7).

Table 7.

Factors affecting livelihood adaptation strategies during ban period: Estimation of Binary Logistic Regression Model.

3.5. Livelihood Outcomes

The overall livelihood status of the hilsa fishers was not satisfactory due to social and economic constraints, such as increasing fisher numbers, low income, lack of alternative income-generating activities, loan problems, piracy, price hikes, and conflicts with stakeholders for resources (Table 8). The key livelihood outcomes and their linkages to social-ecological traps, along with possible pathways to escape these traps, are summarized in Table 9.

Table 8.

The livelihood outcomes of hilsa fishers in the study areas.

Table 9.

The livelihood outcomes link to the social–ecological traps.

3.6. Falling into the Traps

3.6.1. Poverty

Poverty traps are circumstances in which poverty-stricken people are stuck in steady or rising levels of poverty because they are unable to mobilize the resources needed to escape shocks or long-term low-income conditions. Lack of access to credit and money can prevent poverty-stricken people from adopting higher-risk livelihood options, which can lead to higher earnings possibilities, and is often worsened by social exclusion. Because of this, those who are poor have to protect their limited assets, which forces them to select livelihood options with little potential for long-term gain. Due to declining hilsa stocks, fewer catches, and fewer chances for employment, their income dropped, trapping them in a cycle of poverty and forcing them to continue depending on unsustainable fishing methods to fulfill their short-term financial requirements. According to fishers from Ali Akmol Ghat, “The catch is lower and there are more hilsa fishermen in the area these days. To purchase boats and fishing equipment as well as to survive during the crisis, we also borrowed money from the dadondars. As a result, we have to sell the fish to neighborhood moneylenders, and they set the price. The true cost of fish was not revealed. Sometimes, there was so little hilsa that we did not even make back the money we spent on the entire fishing trip. Nothing changed in terms of the standard of living. We are constantly poor.”

3.6.2. Single Income Source

Even as hilsa numbers are declining, communities that primarily depend on the fishery risk are stuck in a cycle of dependence, making it difficult to switch to other sources of income. Many fishermen had nowhere else to look for money during the ban. As a result, they frequently use illegal fishing nets and ignore illegal fishing restrictions. Fishermen are limited to a single source of income due to the lack of diversification in these remote local economies, lack of other skills, and lack of start-up money for other types of operations. Increased support for alternative means of livelihood is necessary to improve the resilience of fishing communities. From Patuakhali, a female responder stated, “We are aware that hilsa population growth and abundance benefit from fishing prohibition times. Nevertheless, my husband was unable to go fishing and could not purchase food for the family during the fishing restriction period. This is a crucial moment for survival. We do not always receive rewards correctly. My husband engages in illegal fishing as a way out of this suffering”.

3.6.3. Dadon System

Dadondar is the term for an unwritten agreement between a moneylender and a fisherman wherein the lender demands that the fisherman sell the fish to him or that the moneylender receives a certain fee when the fish are sold to a third party. Because the majority of hilsa fishermen (87.85%) do not have savings, they rely heavily on dadondars (17.81%) (Table 4), which accounts for 5–10% of their sales commission. They become trapped in a debt cycle when they are unable to return to dadondar.

Hilsa fishermen described how they were perpetually trapped in a debt cycle in the district of Chattogram FGDs: “Our income from fishing is poor, and hilsa fishing is very capital-intensive. We do not have access to official credit markets such as banks (government and non-government); therefore, we borrow money from local individual money lenders (dadondars) to purchase fishing boats and other equipment, and to invest in fish harvesting. Since we do not own any land, banks do not lend money. Consequently, we continue to rely on unofficial credit systems such as the dadon system. Because we are unable to repay the loan in full, the dadon system keeps us in a debt cycle with the money lender”.

3.6.4. Inter-Generational Traps

Owing to their familial involvement, the majority of hilsa fishermen (81.78%) engaged in hilsa fishing (Figure 4). Reliance on traditional fishing methods that may no longer be sustainable in the face of changing environmental conditions is reinforced when traditional fishing families pass down fishing practices and cultural norms related to hilsa fishing from generation to generation.

3.6.5. Increased Fishers

Because there are too many fishermen competing for insufficient fish, this raises fishing pressure. To capture enough fish, even to cover their own subsistence requirements, fishermen resorted to illegal measures.

A 50-year-old fisherman provided more context in hilsa fishing, saying, “In my younger days, I hardly ever saw another fisherman within a kilometer of me on the water. Nets and other fishing gear are now arranged in close proximity to my fingers. As a result, fishing space is highly competitive, which may turn nasty”.

3.6.6. Frequent Ban Period

The desperation caused by frequent ban seasons has put immense pressure on hilsa stocks. This leads to starvation, and they are caught in a debt cycle. Furthermore, the lack of alternative sources of income and the persistence of extreme poverty continue to be major factors in non-compliance with the hilsa ban period. These were the primary excuses given by the majority of respondents to break fishing prohibitions. Fishermen are entitled to compensation for wages lost because of fishing limitations, but they are not granted any rights or opportunities to enhance their standard of living. For example, because they lack assets or property for security, they have limited access to formal credit. Their uncertain income makes it hard for them to repay their debt, even on microcredit. The fact that fishermen are still obligated to pay back interest on their debts during fishing restrictions is a significant flaw in the compensation plan that may force them to continue fishing. As fishing is the primary source of income for repaying loans, fishermen find it difficult to make weekly microcredit installment payments.

3.6.7. Reduced Hilsa Catch

The use of destructive fishing gear; large catches of hilsa; an increased number of fishers; climate change impact; illegal catching of juveniles; and broodstock, siltation, and illegal access are the main causes of hilsa reduction. It keeps fishermen stuck in a cycle of debt and poverty. Hilsa fishermen are susceptible to financial problems due to the seizure of the hilsa catch, monetary fines, and imprisonment. As one of the responders noted, “Hilsa has declined during the previous 10 years. I have been fishing for the past 40 years. I notice the contrasts between now and 20 years ago. After a few hours of fishing, the boat deck was filled with hilsa. Over a 15-days trip, 70–80 mounds were received. We rarely received 10–20 mounds. If we sell this fish to local markets, the dadondar will collect his interest in borrowed funds. We scarcely have any money left over to spend on our families and ourselves. We need to shift occupations because we are going through a difficult period”.

Seven reasons as perceived by the fishers were documented and ranked using Garrett’s Ranking Technique (Table 10) to identify the reasons behind the decline in the hilsa fishery in the Chattogram and Patuakhali districts of Bangladesh. According to fishers, the use of destructive fishing gear (mean score 65.64) was ranked first among the reasons behind the decline in hilsa fisheries. ‘Huge catch of hilsa’ (mean score 62.22) was ranked as the second reason for the decline in hilsa catch. ‘Increased fishers’ (mean score 56.85) was ranked third. ‘Climate change impact’ (4th rank) was also reported as one of the major reasons for the decline in the hilsa fishery by the fishers. The illegal catching of juveniles and broodstock was another reason behind the decline in the hilsa fishery, as perceived by the fishers. ‘Siltation’ was ranked 6th by the fishers, and finally ‘illegal access’ (mean score 29.35) of outsider fishers in the fishing areas were also responsible for reduced hilsa catch (Table 10).

Table 10.

Perception of the hilsa fishers regarding the causes of the hilsa fishery’s decline.

4. Discussion

4.1. Livelihood Capitals

People need a variety of assets to attain favorable livelihood outcomes [18]. Even those who are most impoverished have the resources or things that they rely on. In fact, they must employ various financial sources. Therefore, awareness of people’s existing assets and how they are used must be the foundation of any effort to make livelihoods more sustainable and secure. If this is not done, policies that weaken or destroy the foundation of people’s livelihoods or increase their vulnerability may be implemented [28].

Hilsa fishermen are socioeconomically backward because of their low literacy rates, inconsistent incomes, inadequate access to drinking water, poor catches, and lack of alternative sources of livelihood. Compared with the results of Sunny et al. (2019) [2], our results showed that 54.66% of respondents lacked literacy, but 49.80% of those surveyed stated that their children attend school rather than go fishing (Table 2), indicating that the region’s educational standing steadily improved. It was discovered that fishermen’s low socioeconomic status prevented them from having access to schooling, which was confirmed by Khan et al.’s (2018) findings [8]. Physical capital is a key tool for boosting the increase in family income, and the current state of affairs suggests that physical capital is not in excellent form [18]. Most fishermen (88.66%) lived in rented houses, according to house ownership (Table 3), which was also confirmed by Sunny et al. (2019) and Apine et al. (2019) [2,24]. The increase in hilsa fishers affects both the natural and human capital of hilsa fisheries. Due to increased fishing pressure and the use of illegal nets, the natural capital status is not in good shape.

One of the main causes of social–ecological traps is middlemen. It is interesting to note that intermediaries are seldom considered in fisheries governance [12]. Intermediaries, such as local traders or dadondars, have the greatest impact on financial capital. The main basis of the agreement between intermediaries and hilsa fishermen was credit support. This type of assistance bound small-scale fishermen to middlemen through patron-client relationships and constituted a labor-buying loan. Such agreements have a number of negative effects, such as a predetermined buyer and seller in marketplaces [29], loss of fisherfolk autonomy and independence [30], decreased pricing, and diminished bargaining power [31]. According to the survey, conflicts between fishermen and dadondars (91.3%) resulted from a failure to repay, while conflicts between fishermen and aratdars (42.7%) arose from sharing a percentage of the sales. Islam et al. (2017) state that conflicts between the fishing team and the mohajon (boat owner) occur when the latter believes there has been unfair profit sharing or wage payment because the former has connections to influential local political figures and tries to deny the hired fishermen’s supposed wages [32]. Fishermen compete aggressively over fishing areas, which frequently results in conflicts that cause property damage or even physical injury.

4.2. Vulnerability Context

The three main categories of vulnerability are shocks, trends, and seasonality [18]. These three groups included those who had experienced difficulties in the study area. The livelihood of fishermen is threatened externally by the climate, markets, or unexpected calamities [21]. Both external and internal factors are responsible for creating socio-ecological traps. According to Sunny et al. (2019), fishers of the Padma River face several issues arising from both human and natural causes [2]. The primary obstacles included natural disasters, declining fish harvests, prohibition times, the cost of dadons, rent money, inadequate market facilities, and theft of fishing gear, particularly nets and boats. Their livelihood is more vulnerable because of their reliance on a single profession (fishing). These results also agree with what I have discovered. According to Sunny et al. (2020), the primary threats reported by fishermen were ban periods, insufficient support during the ban period, increasing pressure from creditors, declining fish catches, weak value chains and poor market facilities, and loss of fishing gear, particularly nets and boats [33]. According to the results of this study, 73.22% of respondents said that low catch rates were caused by increasing fishing pressure, and around 69.64% of respondents claimed that frequent ban periods made their lives more vulnerable. Certain actors, such as intermediaries, are able to reap the majority of their advantages due to poor management and abuse of power, which significantly contributes to societal imbalance and the development of social–ecological traps.

4.3. Livelihood Strategies

The concept of livelihood strategies, according to Carloni and Crowley (2005), is “the range and combination of activities and choices that people make to achieve their life goals” [34]. When a household faces a crisis or an external shock, it uses a combination of coping strategies to maintain food security and a sustainable livelihood system [35]. After a natural disaster, there was less opportunity to make money, and shortages of food, clean water, and medical supplies were expected. Loans from aratdar (94.0%) were the first adaptation strategy in a crisis situation (Figure 5). They typically eat three meals a day, but in emergency situations, they may only eat two or even one. Hussain et al. (2022) stated that food shortages affected low-income fishing households throughout the prohibition period [36]. To cope with this, 50% of them took out loans from different sources, 20% reduced their meals or bought less expensive foods, 10% sold cultured fish, 10% repaired nets, 4% took dadon, 4% netted ponds for fish harvesting, just 1% were able to spend money from savings and one percent worked as day laborers in other people’s agricultural fields [37]. Diverse livelihoods are crucial for reducing poverty and advancing sustainable development [38]. However, the findings indicate that hilsa fishermen have limited options as alternative sources of income. According to DFID (1999) [18], there are several livelihood possibilities that might be made possible by accessible financial capital [18].

4.4. Transforming Structures and Processes

Policies, organizations, culture, and the job market all play a significant role in ensuring the sustainability of natural resources, such as hilsa fisheries. According to Coulthard et al. (2011), “ policy and management deliberations on how to respond to the global fisheries crisis in poorer developing countries are often discussed in terms of the technical challenges involved, but sidestep the broader moral challenge of how to govern fisheries for conservation without worsening the plight of the already vulnerable men, women, and children who depend on them” [39]. Institutional support can help maintain household livelihood adaptability [23].

According to this report, the unsustainable use of hilsa fisheries is mostly the result of an inadequate governance structure. We discovered that the implementation and enforcement of government regulations are often unclear and inappropriate. According to Mozumder et al. (2020), there is a substantial power imbalance in the current hilsa governance structure, with some stakeholders exerting greater influence than others, marginalizing fishermen, and promoting increased non-compliance with illegal fishing, which eventually hurts the hilsa fishery and its users [40]. According to the participants, the main causes of non-compliance with fishery regulations were poverty among fishermen, patron-client relationships with intermediaries, irregularities in the distribution of supplementary food, the availability of illegal and destructive fishing gear, the availability of irresponsible greed for larger catches among certain fishermen (which primarily affects broodstock), corruption within law enforcement agencies, and the exclusion of hilsa fishermen from decision-making. Weak institutions might encourage the adoption of environmentally harmful technologies and reduce the ecological resilience of the system [41].

4.5. Livelihood Outcomes

Livelihood outcomes are the result of livelihood strategies, such as increased income, improved food security, and reduced vulnerability [18]. Income sources are often the main focus of livelihood strategy analysis. One way to conceptualize sustainable livelihood outcomes is poverty. Fair access to resources is essential to eradicate poverty. Despite access to coastal resources, hilsa fishermen’s livelihood outcomes are poor, and the majority have not increased their income to the point where they believe their livelihoods are resilient to the context of their vulnerability. Most fishers explained that, due to several social and economic constraints, including the growing number of fishermen, poor income, lack of alternative sources of income, loan issues, piracy, price increases, and conflicts with stakeholders over resources, the overall livelihood position of hilsa fishermen was unsatisfactory. Most households surveyed confirmed that as a result of declining fisheries for hilsa, their income, food consumption, and basic facilities had decreased. As a result, their social and economic conditions remained unchanged, and a few became more impoverished. Livelihood outcomes have a significant influence on both creating and avoiding socio-ecological traps. However, these findings contradict those of Sarker et al. (2016) [42]. They discovered that 55% of fishermen had improved their socioeconomic status via hilsa fishing. Their homes, food, clothing, and children’s education were all superior. However, the position of 45% of the farmers has not yet improved. Halder et al. (2011) reported these results [43]. Food security, nutrition, health, income, education, housing amenities, the environment, safety, and other aspects are determinants of livelihood outcomes. The socioeconomic circumstances of fishermen in Ramgati Upazila were deemed unsatisfactory by Rana et al. (2018) [44]. Fishers are primarily seen to be poor and landless, and neglected by society; rich people, mahajans, and aratdars use them for their own selfish ends.

4.6. Social–Ecological Traps

The social–ecological traps found in the hilsa fishery are similar to those seen in small-scale African fisheries, as described by Cinner (2011) [10]. In both cases, fishers are often stuck in poverty due to low education, few alternative jobs, and heavy reliance on natural resources for their livelihoods. These factors limit their ability to adapt, creating a cycle in which worsening environmental conditions and ongoing social challenges feed into each other. Cinner (2011) [10] points out that these traps form when short-term solutions undermine long-term sustainability, a phenomenon also evident in the hilsa fishery.

One major similarity is the important role intermediaries play in shaping how fishers make a living. In African fisheries, intermediaries help fishers obtain credit, access markets, and secure fishing supplies, but this often creates dependency and limits their bargaining power and freedom [10]. The hilsa fishery faces a similar situation, in which intermediaries such as aratdars and moneylenders control financing and market access. Although these relationships can offer short-term security, they often trap fishers in debt, making it hard for them to try new jobs or use sustainable fishing methods. This dependence leads to poverty and intergenerational traps, as debt and limited education are passed down to the next generation.

Despite these similarities, there are important differences between African fisheries and the hilsa fishery in Bangladesh. One key difference is in how they are governed. Some African fisheries, as Cinner (2011) [10] notes, use local or community-based management. In contrast, the hilsa fishery is managed by several state agencies and policies, making the system more complex and fragmented. This often leads to poor coordination, weak enforcement, and little accountability.

According to Mozumder et al. (2020) [40], fisheries governance in Bangladesh is marked by overlapping responsibilities and fragmented sectors, which weaken management and make fishers more vulnerable. These problems make it harder for institutions to control intermediaries, enforce fishing bans, or provide fair access to compensation and support. As a result, fragmented governance makes social–ecological traps worse by limiting fishers’ chances to break free from dependency and adapt to changes.

In summary, this comparison shows that while issues such as poverty, reliance on intermediaries, and overuse of resources are common across fisheries, the exact causes and effects depend on local institutions, politics, and social conditions. Looking at the hilsa fishery in this wider context highlights the need for governance reforms and better coordination that fit the local situation to help break these ongoing social–ecological traps.

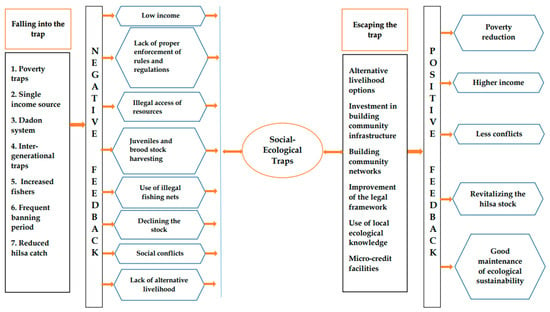

4.6.1. Falling into the Traps

Users of fishery resources frequently engage in unethical fishing activities; this is especially common when institutional and governance frameworks are inadequate [45]. The research regions revealed a lack of a strong institutional and governance framework to blame for driving the hilsa fishing community into social–ecological traps. Additionally, Acemoglu and Robinson (2008) contended that many institutions and organizations are crucial players in these situations [46]. The majority of hilsa fishermen are poor, and this is the main factor driving them to use illegal gear and maximize their catch output. They are susceptible to socio-ecological traps because of their harmful gear use, poor institutions, and poverty [10]. The majority of them were unaware of the effects of using resources in this way. For developing nations, knowing how poverty relates to biological and economic methods of fisheries management is crucial [39]. Social factors, including the usage of gear, absence or weakness of institutions, and poverty traps, as reviewed by Cinner (2011) [10], function as potent attractors for a social–ecological trap. Undesirable social motivations may strengthen as the flow of goods and services decreases. Under some circumstances, the resulting scarcity of resources can encourage more extensive resource exploitation, which might reduce the resources themselves and the ecological ability to sustain them, resulting in even more scarcity. This process is a social–ecological trap that “ratchets down” the fisheries and moves toward an alternative ecosystem configuration that may be challenging to escape because of the reinforcing nature of these feedbacks between the social and ecological domains. An exceedingly unfavorable yet highly robust social–ecological system might arise from these interactions between society and the environment.

Our findings support the notion that severe poverty and a dearth of alternatives to other sources of income continue to be important factors in non-compliance with the hilsa ban period. This is what the majority of respondents say motivates them to violate the fishing prohibitions. Fishermen are entitled to compensation for wages lost because of fishing limitations, but they are not granted any rights or opportunities to enhance their standard of living. For example, they have restricted access to conventional financing because they lack assets or property security. Even with microcredit, they struggle to pay off debt because of their irregular incomes [47]. The fact that fishermen are still obligated to pay back interest on their debts during fishing restrictions is a significant flaw in the compensation plan that may force them to continue fishing. Because fishing is the primary source of revenue for repaying loans, fishermen find it difficult to make weekly microcredit installment payments [4]. Our survey results showed that 44% of the respondents cited lowering the debt load as a primary justification for breaking fishing prohibitions.

4.6.2. Negative Feedback

These issues have a detrimental effect on coastal populations, such as hilsa fishermen, and are exacerbated by the incapacity of government structures and organizations to implement laws and regulations effectively. Although top-down management strategies have occasionally been observed in research locations, they are insufficient to address the shocks and trends that these areas are experiencing [21]. The use of illicit fishing nets, harvesting of hilsa that is too small, and unauthorized access for resource usage are among the illegal fishing activities that are made more common by institutional and governmental failures (Figure 6). The growing number of fishermen adds to the already complicated issues of low catch, low wages, disputes between many parties, and stock decline (Figure 6). Mozumder et al. (2019) [48] reported similar results. They discovered that poor hilsa fish catches are a result of a growing population because too many fishermen compete for a finite number of fish. Because of this, fishermen have resorted to illegal methods in an effort to catch enough fish to fulfill their own subsistence needs [4]. Conflicts between various stakeholders (competition for fishing spaces and inclusion in incentive programs) also had a detrimental effect on revenue.

Figure 6.

The social–ecological traps of the hilsa fishery in the Chattogram and Patuakhali districts of Bangladesh (Adapted from Cinner, 2011 [10]).

At the harvest level, improper policies pertaining to conservation, enforcement, social equality, and collective bargaining lead to a number of issues such as undersized hilsa harvesting, decreased revenue, disputes among fishermen, and diminishing stock. In these circumstances, middlemen profit from the current supply chain, which provides harvesters with financial assistance when they are in need. The social and ecological aspects of hilsa fisheries are, therefore, negatively impacted by these negative feedbacks, which lead to the formation of socio-ecological traps.

4.6.3. Escaping the Traps

This study analyzes the elements that prevent hilsa fisheries from falling into social–ecological traps, in addition to the numerous reasons that lead the fishery to fall into these traps. Adopting a multifaceted strategy or aspect can help recovery. Our research indicates that traps can be avoided by advancing property rights (a suggestion that Cinner (2011) also made) [10]. Some negative effects can be lessened by strengthening current organizations, such as providing fair credit assistance [49]. Various institutions continue to play a significant role in controlling access to resources [21]. Escaping poverty may be facilitated by strengthening the legal framework, creating community networks, providing alternative livelihood options, investing in the development of community infrastructure, utilizing local ecological knowledge, and setting up microcredit facilities (Figure 6). In addition, it is possible to reduce the use of illegal fishing nets, capture and purchase of undersized hilsa, inappropriate loans, and financial support. The participation of hilsa fishermen in decision-making is crucial because they possess the most information. Coulthard et al. (2011) suggest that policy creation may be made more effective by considering diverse perspectives, goals, and capabilities [39]. We argue that for policies to be successfully implemented, the governance structure must be founded on a better comprehension of the social context, ecological dynamics, institutional capability, and potential external threats. Jentoft and Chuenpagdee (2015) proposed that legislation should be introduced carefully, taking into account non-formal cultural organizations and recognizing the role of government initiatives [50].

4.6.4. Positive Feedback

The above-mentioned combined strategies will help increase the sustainability of hilsa fisheries. Although improving efficiency has been seen as a means of helping fishermen make more money, this strategy is becoming less and less effective in light of the evolving conditions in fisheries [21]. Regardless of fishing gear efficiency, fishermen will benefit from reduced poverty, more income, fewer conflicts, revitalized hilsa stock, and appropriate management of biological sustainability (Figure 6). Furthermore, alternative revenue sources can increase the likelihood of ensuring both economic gain and conservation, as stated by Mozumder et al. (2018) [51]. Diversification can reduce reliance on a particular species and encourage hilsa fishermen to obtain resources from other fisheries. By improving ecosystem health and easing the pressure on the hilsa stock, the system might avoid slipping into social–ecological traps. Cooperation among fishermen, the provision of emergency aid after calamities, microcredit, training, and resources for alternative income-generating ventures, according to Islam et al. (2017), would help reduce conflicts between various stakeholders [32].

5. Conclusions

The purpose of this study was to examine the social–ecological traps associated with Bangladesh’s hilsa fishery and to identify the factors that influence livelihood adaptation strategies throughout the ban period. The study found that social–ecological traps are produced when certain sustainability requirements are not met, mostly caused by poor governance, widespread poverty, the involvement of intermediaries, globalization, and overexploitation. As a result, negative feedback emerges, including ignorance of conservation laws, declining earnings, reduced stock, and increased social conflicts. This research also identifies ways to avoid falling into social–ecological traps. These methods include the implementation of fishing rules and regulations, offering equitable credit support, creating alternative sources of income, using environmentally friendly fishing gear, and minimizing the harvesting of undersized hilsa. Such actions may result in benefits for small-scale fishermen, including reduced poverty, higher incomes, fewer social conflicts, and the ecological sustainability of resources for future generations and long-term jobs. By recognizing and acting on these interconnected issues, Bangladesh can pave the way toward a more resilient hilsa fishery and a balanced relationship between human needs and ecological sustainability. The ban period had a potential impact on their livelihoods. There are a few alternative livelihood opportunities that trap them in debt cycles. They must take loans from dadondar, aratdar, and boat owners, who charge high interest rates, in order to adapt to their crisis situation. When they fail to repay the moneylender and are under heavy pressure from them, they even migrate to India. Several factors, such as training facilities and house ownership, belong to a formal society, and family members influence their adaptation strategies during the ban period. The study also provides recommendations to sustain the livelihood of hilsa fishing communities. Some important initiatives are to encourage fishers’ children in technical education rather than general education and inspire the fishers’ community to undertake proper family planning to reduce their family size. In addition, they should strengthen their housing and local infrastructure to cope with different natural disasters. The government and local authorities should arrange employment opportunities for fishers or provide training to improve their livelihoods during the off-season.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.; methodology, A.T. and M.S.; software, A.T. and K.A.; validation, M.M.S.; formal analysis, M.A., M.S. and K.A.; investigation, M.A. and K.A.; resources, M.M.S. and M.M.H.M.; data curation, A.T. and M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.; writing—review and editing, M.M.S.; visualization, M.M.S., M.M.H.M. and M.A.; supervision, M.S.; project administration, M.M.S.; funding acquisition, M.M.H.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funded by National Science and Technology Fellowship 2023-24, under the Ministry of Science and Technology of the Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh (Tracking number 1689688106).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by The Ethics Committee of Sylhet Agricultural University (protocol code ARP2025049, approval date 11 December 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The first author discloses the data used for the present study upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- DoF Yearbook of Fisheries Statistics of Bangladesh, 2021–2022; Fisheries Resources Survey System (FRSS), Department of Fisheries; Ministry of Fisheries and Livestock: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2022; Volume 39, 139p.

- Sunny, A.R.; Ahamed, G.S.; Mithun, M.H.; Islam, M.A.; Das, B.; Rahman, A.; Rahman, M.T.; Hasan, M.N.; Chowdhury, M.A. Livelihood status of the hilsa (Tenualosa ilisha) Fishers: The case of coastal fishing community of the Padma River, Bangladesh. J. Coast. Zone Manag. 2019, 22, 469. [Google Scholar]

- Mome, M.A.; Officer, E.; Bhaban, M.; Arnason, R. The Potential of the Artisanal Hilsa Fishery in Bangladesh: An Economically Efficient Fisheries Policy; Fisheries Training Programme Final Project Report; United Nations University: Reykjavik, Iceland, 2007; 57p. [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo, A.K.; Wahab, M.A.; Phillips, M.; Rahman, A.; Padiyar, A.; Puvanendran, V.; Bangera, R.; Belton, B.; De, D.K.; Meena, D.K.; et al. Breeding and culture status of Hilsa (Tenualosa ilisha, Ham. 1822) in South Asia: A review. Rev. Aquac. 2018, 10, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, E.Y.; Ali, L.; Ali, S.; Hussein, B.; Wahab, M.A.; Sage, N. Hilsa’s Non-Consumptive Value in Bangladesh: Estimating the Non-Consumptive Value of the Hilsa Fishery in Bangladesh Using the Contingent Valuation Method; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmud, Y. (Ed.) Hilsa Fisheries Reseach and Development in Bangladesh; Bangladesh Fisheries Reseach Institute: Mymensingh, Bangladesh, 2020.

- Amin, S.M.N.; Rahman, M.A.; Haldar, G.C.; Mazid, M.A.; Milton, D.A. Catch per unit effort, exploitation level and production of Hilsa shad in Bangladesh waters. Asian Fish. Sci. 2008, 21, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.; Islam, M.M.; Kundu, G.K.; Akter, M.S. Understanding the Livelihood Characteristics of the Migratory and Non-Migratory Fishers of the Padma River, Bangladesh. J. Sci. Res. 2018, 10, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunny, A.R.; Islam, M.M.; Nahiduzzaman, M.; Wahab, M.A. Coping with climate change impacts: The case of coastal fishing communities in upper Meghna hilsa sanctuary of Bangladesh. In Water Security in Asia: Opportunities and Challenges in the Context of Climate Change; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Cinner, J.E. Social-ecological traps in reef fisheries. Glob. Environ. Change 2011, 21, 835–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Mohammed, E.Y.; Ali, L. Economic incentives for sustainable hilsa fishing in Bangladesh: An analysis of the legal and institutional framework. Mar. Policy 2016, 68, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crona, B.; Nyström, M.; Folke, C.; Jiddawi, N. Middlemen, a critical social-ecological link in coastal communities of Kenya and Zanzibar. Mar. Policy 2010, 34, 761–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hänke, H.; Barkmann, J.; Coral, C.; Kaustky, E.E.; Marggraf, R. Social-ecological traps hinder rural development in southwestern Madagascar. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laborde, S.; Fernández, A.; Phang, S.C.; Hamilton, I.M.; Henry, N.; Jung, H.C.; Mahamat, A.; Ahmadou, M.; Labara, B.K.; Kari, S.; et al. Social-ecological feedbacks lead to unsustainable lock-in in an inland fishery. Glob. Environ. Change 2016, 41, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steneck, R.S.; Hughes, T.P.; Cinner, J.E.; Adger, W.N.; Arnold, S.N.; Berkes, F.; Boudreau, S.A.; Brown, K.; Folke, C.; Gunderson, L.; et al. Creation of a gilded trap by the high economic value of the Maine lobster fishery. Conserv. Biol. 2011, 25, 904–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyango, P.; Jentoft, S. Assessing poverty in small-scale fisheries in Lake Victoria, Tanzania. Fish Fish. 2010, 11, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrington, J.; Carney, D.; Ashley, C.; Turton, C. Sustainable livelihoods in practice: Early applications of concepts in rural areas. Environment, development & rural livelihoods. Nat. Resour. Perspect. 1999, 42, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- DFID UK. Sustainable Livelihoods Guidance Sheets; DFID: London, UK, 1999; Volume 445, p. 710.

- Scoones, I. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: A Framework for Analysis; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 1998; Volume 72, pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, F. Rural Livelihoods and Diversity in Developing Countries; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Allison, E.H.; Ellis, F. The livelihoods approach and management of small-scale fisheries. Mar. Policy 2001, 25, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankland, A. Analysing Policy for Sustainable Livelihoods; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Allison, E.H.; Horemans, B. Putting the principles of the Sustainable Livelihoods Approach into fisheries development policy and practice. Mar. Policy 2006, 30, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apine, E.; Turner, L.M.; Rodwell, L.D.; Bhatta, R. The application of the sustainable livelihood approach to small scale-fisheries: The case of mud crab Scylla serrata in South west India. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2019, 170, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmer, D.W., Jr.; Lemeshow, S.; Sturdivant, R.X. Applied Logistic Regression; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, H.E.; Woodworth, R.S. Statistics in psychology and education; Longmans, Green and Co.: London, UK, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Dhanavandan, S. Application of garret ranking technique: Practical approach. Int. J. Libr. Inf. Stud. 2016, 6, 135–140. [Google Scholar]

- Ashley, C.; Carney, D. Sustainable Livelihoods: Lessons from Early Experience; Department for International Development: London, UK, 1999; Volume 7, No. 1.

- O’Neill, E.D.; Crona, B. Assistance networks in seafood trade–a means to assess benefit distribution in small-scale fisheries. Mar. Policy 2017, 78, 196–205. [Google Scholar]

- Willmann, R.; Franz, N.; Fuentevilla, C.; McInerney, T.F.; Westlund, L. A human rights-based approach to securing small-scale fisheries: A quest for development as freedom. In the Small-Scale Fisheries Guidelines: Global Implementaion; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 15–34. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, J.G.; Villasante, S. Disentangling seafood value chains: Tourism and the local market driving small-scale fisheries. Mar. Policy 2016, 74, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Shamsuzzaman, M.M.; Sunny, A.R.; Islam, N. Understanding fishery conflicts in the hilsa sanctuaries of Bangladesh. In Inter-Sectoral Governance of Inland Fisheries; Song, A.M., Bower, S.D., Onyango, P., Cooke, S.J., Chuenpagdee, R., Eds.; TBTI Global Foundation: Bangkok, Thailand, 2017; pp. 18–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sunny, A.R.; Prodhan, S.H.; Ashrafuzzaman, M.; Sazzad, S.A.; Mithun, M.H.; Haider, K.N.; Alam, M.T. Understanding livelihood characteristics and vulnerabilities of small-scale fishers in coastal Bangladesh. Preprints 2020, 2020060303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart Carloni, A.; Crowley, E. Rapid Guide for Missions. In Analysing Local Institutions and Livelihoods; Institutions for Rural Development (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, S. Adaptable Livelihoods: Coping with Food Insecurity in the Malian Sahel; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, A.A.; Mahdi, G.M.A.; Azad, A.K.; Kabir, S.H.; Pramanik, M.M.H.; Ullah, M.R.; Hasan, M.M.; Ullah, M.A. Socioeconomic, livelihood and cultural profile of the Meghna River Hilsa Fishing Community in Chandpur, Bangladesh. Arch. Agric. Environ. Sci. 2022, 7, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruque, M.H.; Ahsan, D.A. Socio-economic status of the Hilsa (Tenualosa ilisha) fishermen of Padma River, Bangladesh. World Appl. Sci. J. 2014, 32, 857–864. [Google Scholar]

- WRI. World Resources 2008: Roots of Resilience—Growing the Wealth of the Poor; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Coulthard, S.; Johnson, D.; McGregor, J.A. Poverty, sustainability and human wellbeing: A social wellbeing approach to the global fisheries crisis. Glob. Environ. Change 2011, 21, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozumder, M. Socio-Ecological Resilience of a Small-Scale Hilsa Shad (Tenualosa ilisha) Fishery in the Gangetic River Systems of Bangladesh. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Helsink, Helsinki, Finland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, B.; Barrett, S.; Polasky, S.; Galaz, V.; Folke, C.; Engström, G.; Ackerman, F.; Arrow, K.; Carpenter, S.; Chopra, K.; et al. Looming global-scale failures and missing institutions. Science 2009, 325, 1345–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarker, M.J.; Uddin, A.M.M.B.; Patwary, S.A.; Tanmay, M.M.H.; Rahman, F.; Rahman, M. Livelihood status of hilsa (Tenualosa ilisha) fishermen of greater Noakhali regions of Bangladesh. Fish. Aquac. J. 2016, 7, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, P.; Ali, H.; Gupta, N.; Aziz, M.S.B.; Monir, M.S. Livelihood status of fresh fish, dry fish and vegetable retails at Rajoir Upazila of Madaripur district, Bangladesh. Bangladesh Res. Publ. J. 2011, 5, 262–270. [Google Scholar]

- Rana, M.E.U.; Salam, A.; Shahriar Nazrul, K.M.; Hasan, M. Hilsa fishers of Ramgati, Lakshmipur, Bangladesh: An overview of socio-economic and livelihood context. J. Aquat. Res. Dev. 2018, 9, 1000541. [Google Scholar]

- Agnew, D.J.; Pearce, J.; Pramod, G.; Peatman, T.; Watson, R.; Beddington, J.R.; Pitcher, T.J. Estimating the worldwide extent of illegal fishing. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e4570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acemoglu, D.; Robinson, J. The Role of Institutions in Growth and Development; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- Jentoft, S.; McCay, B.J.; Wilson, D.C. Social theory and fisheries co-management. Mar. Policy 1998, 22, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozumder, M.M.H.; Pyhälä, A.; Wahab, M.A.; Sarkki, S.; Schneider, P.; Islam, M.M. Understanding social-ecological challenges of a small-scale hilsa (Tenualosa ilisha) fishery in Bangladesh. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, S.; McNamara, N.; Acholo, M. Sustainable Livelihood Approach: A Critical Analysis of Theory and Practice; Geographical Paper No. 189; The University of Reading: Reading, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jentoft, S.; Chuenpagdee, R. Assessing governability of small-scale fisheries. In Interactive Governance for Small-Scale Fisheries: Global Reflections; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Mozumder, M.M.H.; Wahab, M.A.; Sarkki, S.; Schneider, P.; Islam, M.M. Enhancing social resilience of the coastal fishing communities: A case study of hilsa (Tenualosa ilisha H.) fishery in Bangladesh. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.