1. Introduction

Soil temperature at shallow depths is a critical parameter that influences thermal conductivity, moisture migration, freeze–thaw processes, and the long-term behavior of soil as a natural material. It plays a central role in agriculture, hydrology, climate studies, underground energy systems, and the durability of structures and infrastructures in contact with the ground [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. In geotechnical engineering, the shallow soil temperature directly affects the frost penetration depth, heave potential, and the thermo-mechanical response of buried utilities and foundations. Shallow subsurface temperatures also control the thermal fatigue of buried pipelines, influence the durability of pavement subgrades, and govern the seasonal behavior of energy geostructures such as energy piles and ground heat exchangers. Consequently, accurate prediction of soil temperature is essential for ensuring structural reliability, optimizing underground infrastructure performance, and designing long-term sustainable ground–energy systems [

3,

4].

Soil acts as a natural thermal reservoir due to its heat capacity and damping of short-term atmospheric fluctuations, making it relevant for seasonal thermal storage and the design of ground-coupled systems. However, the thermal regime of shallow soils arises from complex interactions between atmospheric forcing, moisture content, soil structure, and subsurface energy balance [

5]. These interactions are further influenced by hydro-mechanical and biochemical processes such as soil–water retention, pedogenic transformation, and mineralogical evolution, as highlighted in recent environmental and geotechnical research [

6,

7,

8]. Likewise, studies addressing spatio-temporal variability in soil moisture, atmospheric energy transfer, and environmental feedback mechanisms underscore the importance of understanding soil–atmosphere interactions for accurate near-surface temperature forecasting [

9,

10,

11]. In addition, advanced measurement techniques such as heat-pulse sensing demonstrate the growing need for precise characterization of thermal properties, especially in frozen or partially saturated ground [

12,

13,

14].

Traditional soil temperature models are largely based on analytical or semi-analytical heat transfer formulations, such as the Carslaw–Jaeger equation or simplified sinusoidal models [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Although physically interpretable, these models require detailed thermo-physical parameters, boundary conditions, and emissivity estimates that are often difficult to determine in heterogeneous field soils. Their predictive ability can degrade significantly when applied across diverse climates or soil types. For this reason, researchers have increasingly turned to data-driven approaches that exploit meteorological inputs for soil temperature estimation [

20,

21,

22,

23]. Early machine learning (ML) studies demonstrated the potential of regression models and neural networks to capture nonlinearities in soil thermal behavior [

24,

25,

26]. More recent works highlight the advantages of hybrid and ensemble techniques, including those combining decision trees, boosting algorithms, and empirical mode decompositions, which often outperform individual models in accuracy and robustness [

27,

28].

However, despite the rapid progress in ML applications for soil temperature forecasting, several gaps remain. Many models are site-specific, rely on limited or shallow datasets, or exhibit reduced accuracy when applied to deeper layers or under extreme climatic conditions. The transition from physical models to ML is motivated not only by these limitations but also by the increasing availability of high-resolution meteorological records. Yet, most ML studies depend heavily on default hyperparameters, making their performance sensitive to model configuration and limiting their generalization capability. Approaches such as panel-data formulations [

24], which combine both temporal and cross-sectional observations to capture variations across time and locations simultaneously, illustrate the promise of structured ML strategies, although their implementation in soil temperature problems remains uncommon. Likewise, systematic hyperparameter optimization, particularly for mixed integer real search spaces, has been insufficiently explored in this domain.

A review of existing ML approaches reveals varying levels of performance and generalization across methods. Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) have been widely applied due to their capacity to model nonlinear relationships, but they often require extensive datasets and may suffer from instability in training, especially when soil thermal properties exhibit seasonal variability [

24,

25,

26]. Support Vector Machines (SVMs) provide strong theoretical guarantees and perform well on small datasets but are highly sensitive to kernel selection and offer limited interpretability in geotechnical contexts [

20,

25]. Random Forests and Bagging methods generally achieve robust performance across diverse soil–climate conditions because of their ensemble nature and resistance to overfitting [

25,

26,

27]. Boosting models such as Gradient Boosting and XGBoost typically outperform standalone regressors due to sequential error correction and embedded regularization, but their accuracy depends critically on proper hyperparameter tuning [

27,

28]. Hybrid or decomposition-based models combining empirical mode decomposition, MARS, or optimization heuristics have shown promise in capturing multi-scale soil temperature dynamics but remain computationally demanding and site-specific [

28,

29,

30,

31]. Motivated by these challenges, the present study introduces a hybrid machine-learning framework for predicting soil temperature at shallow depths by integrating four tree-based regressors (Decision Tree, Random Forest, XGBoost, and Bagging) with a novel derivative-free hyperparameter optimizer, the Tri-phase Opposition Adaptive Random Search (TOARS). This optimization-driven ensemble aims to enhance predictive accuracy and robustness across different dataset sizes and depths. The study contributes to a deeper understanding of soil thermal behavior while offering practical tools for geotechnical engineering, sustainable energy system design, and environmental monitoring.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

To structure the scientific motivation and guide the methodology, the study is built upon the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1. TOARS optimization significantly improves the predictive accuracy of tree-based machine learning models compared with default configurations.

Hypothesis 2. Soil temperature prediction performance varies with dataset size, with interpretable models (e.g., Decision Trees) performing best on large datasets and regularized boosting models (e.g., XGBoost) performing best when data are limited.

Hypothesis 3. A TOARS-optimized hybrid ensemble yields more stable and robust predictions across depths than any individual optimized model.

Hypothesis 4. Atmospheric variables including air temperature, humidity, pressure, radiation, and dew point contain sufficient information to reconstruct shallow soil temperature dynamics at 1–2 m depth.

2. Data Collection and Preprocessing

2.1. Site Description and Materials

The study was performed at the IGCMO Campus of the University of Science and Technology “Mohamed Boudiaf” (USTO-MB), located in the region of Es-Senia, Oran, in Algeria (35.65° N, 0.62° W). According to the Koppen–Geiger climate classification, the climate in this region is hot semi-arid (BSh), with summer temperatures reaching approximately 32 °C, winter temperatures averaging around 15 °C, and an average annual rainfall of about 320 mm [

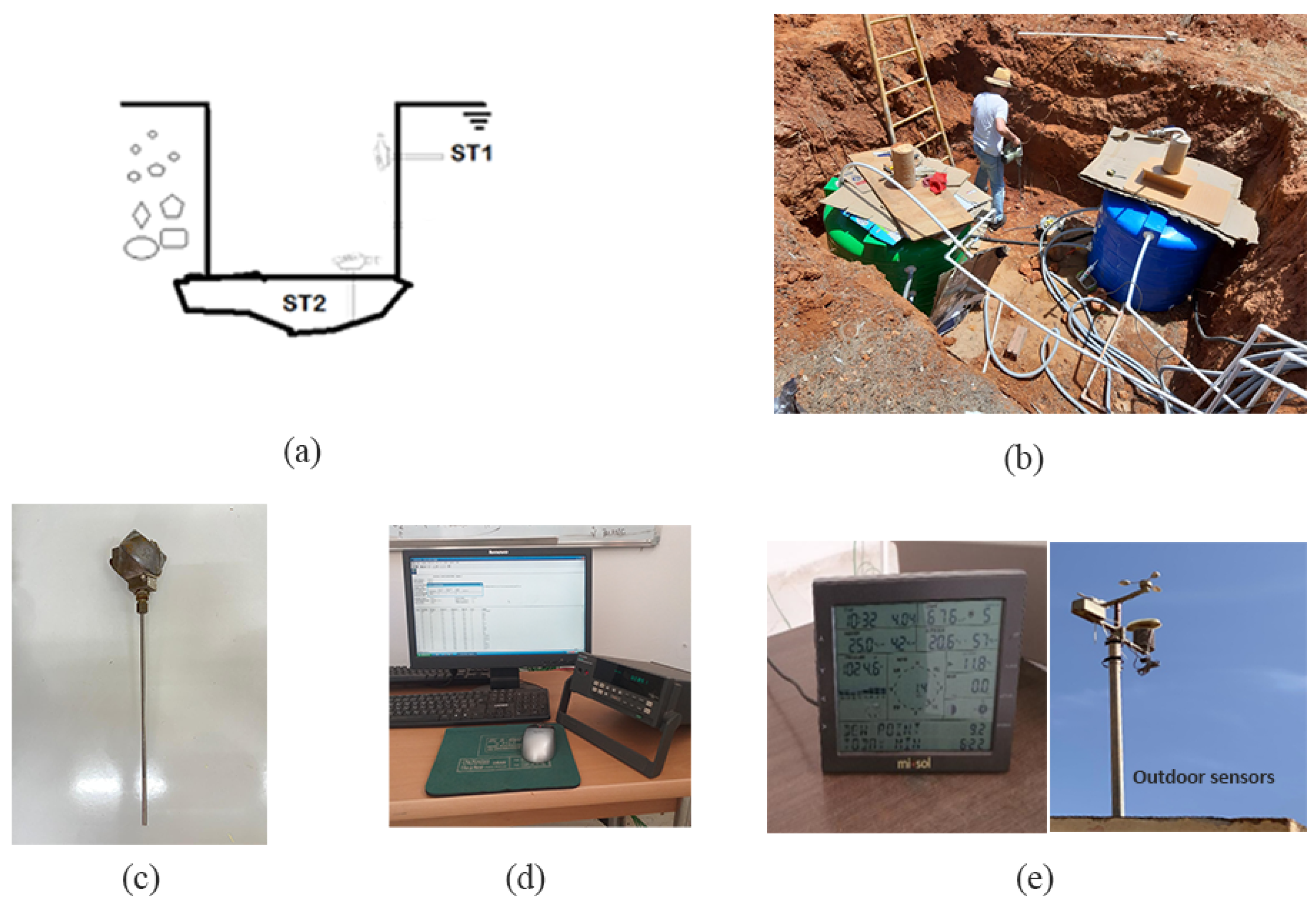

32]. In situ soil temperature measurements were collected using calibrated K-type thermocouples installed at depths of 1 m and 2 m, as illustrated in

Figure 1. The probes were carefully positioned in pre-drilled holes to ensure optimal thermal contact with the surrounding soil and to minimize the disturbance of its natural structure. The soil at the study site is classified as silty clay [

33], and its thermal properties are summarized in

Table 1.

The thermocouples were connected to the data acquisition system (Hydra Fluke 2645A, Fluke Corporation, Everett, WA, USA), which recorded the soil temperature at hourly intervals throughout the monitoring period. Simultaneously, meteorological variables such as the outdoor air temperature, wind speed, relative humidity, absolute and relative pressure, dew point, precipitation, global radiation, and UV index were collected using a mini weather station (WH2310, Shenzhen Fine Offset Electronics Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) installed near the site at a height of 4 m.

Table 2 shows the accuracy of the instruments used for measurements.

2.2. Data Collection and Feature Selection

The measurement campaign was conducted during 2024. This period allowed us to collect nearly 8000 ground temperatures at 1 m, 5000 data at 2 m, and 11,000 data points for the meteorological variables. However, due to a power outage, some data were missing, and only complete rows were selected for the analysis. The data cleaning process resulted in 4041 data points for 1 m and 1842 data points for 2 m.

Table 3 describes the statistics of the collected data.

Small negative wind-speed values, such us −0.97 m/s, result from sensor baseline offsets under near-zero flow conditions. These values fall within the instrument’s accuracy range and were converted to zero during preprocessing to avoid skewing input distributions.

2.2.1. Sampling Frequency

Both the soil temperature sensors and the meteorological station recorded measurements at an hourly sampling frequency, aligned to each full hour (hh:00). Following a power outage, the soil temperature system was manually restarted and resumed operation at the next full hour, whereas the meteorological station continued recording automatically without interruption. The two systems were therefore inherently time-synchronized, and no temporal interpolation or resampling was required before analysis.

2.2.2. Sensor Calibration

All soil thermocouples were calibrated before field deployment using a thermostatic Bain–Marie water bath (Memmert, Schwabach, Germany), ensuring accuracy across the expected operational temperature range. The meteorological station is factory-calibrated and stores calibration coefficients internally, eliminating the need for further field calibration. The embedded manufacturer correction algorithms ensured stable and consistent measurements throughout the monitoring period.

2.2.3. Missing-Data Handling and Standardization

During preprocessing, any row containing at least one missing meteorological or soil temperature variable was removed. Missing entries occurred primarily in wind speed, relative humidity, and outdoor air temperature during brief communication losses. To maintain consistent model inputs across all learning algorithms, complete-case removal was adopted instead of partial imputation. After cleaning, all continuous variables were standardized using z-score normalization to ensure uniform scaling and facilitate efficient model training.

2.2.4. Dataset Size Differences (4041 vs. 1839 Samples)

The difference in dataset size between the shallow layer (4041 samples) and the deeper layer (1839 samples) is due to temporary outages affecting the deep-sensor system. This imbalance does not bias the training process, as each depth-specific model was trained independently using only the data corresponding to its depth. The reduced number of samples at deeper layers is reflected only in slightly wider confidence intervals, as confirmed by the statistical validation in

Section 5.

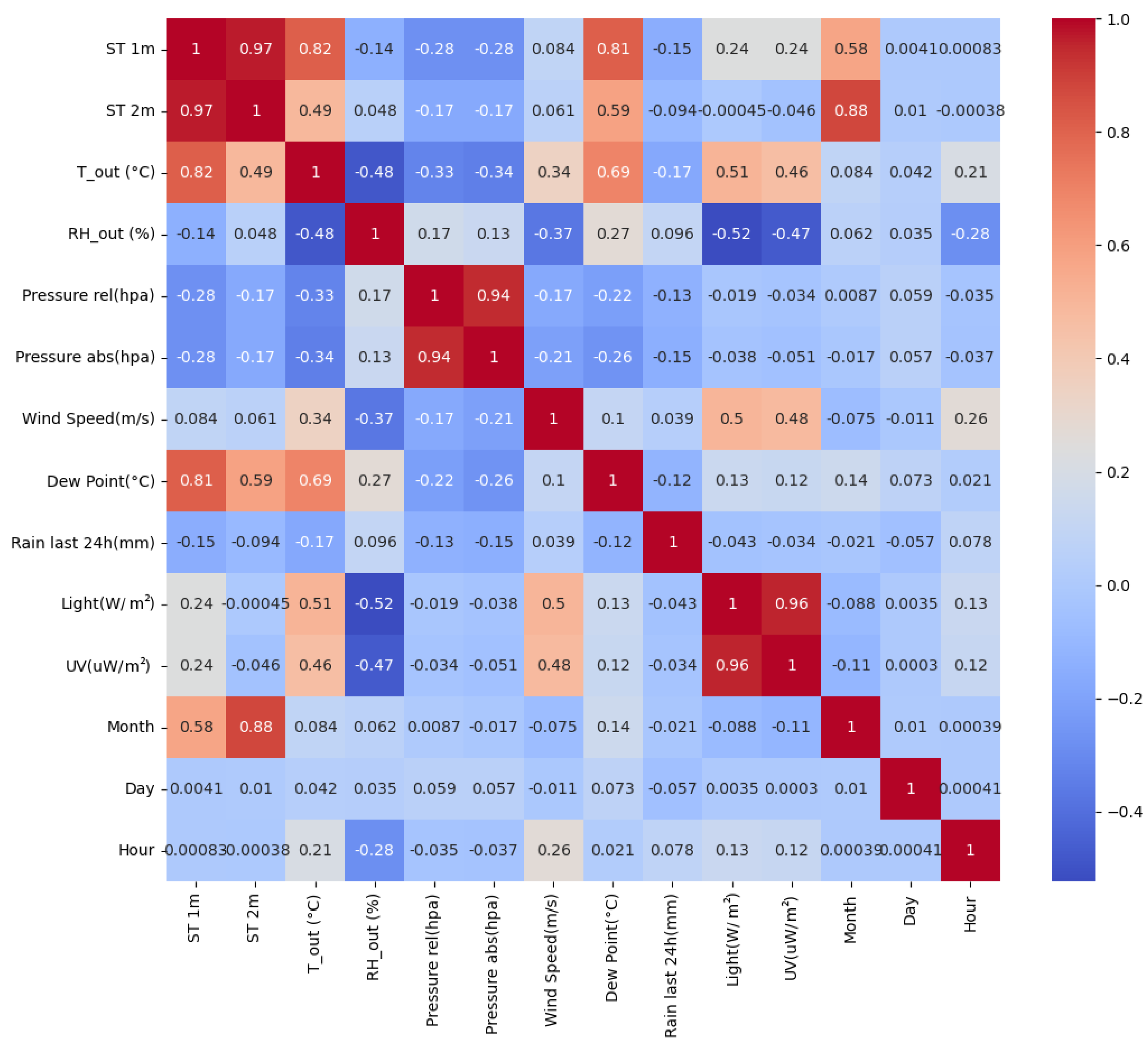

2.2.5. Correlation Matrix

Since the variables were time-dependent, the time series were transformed into separate features representing hours, days, and months. To identify the most relevant variables, a correlation matrix was constructed between all measured and derived features. This allow us to evaluate the linear relationships between variables and detect redundant or highly correlated features. Air temperature, dew point, and month were found to be the most strongly correlated with soil temperature, as shown in

Figure 2. Day and hour contributed less than 10% and have a minor impact on soil temperature variability, since heat propagates slowly through deeper layers, and only seasonal trends remain apparent [

34,

35]. Consequently, they were excluded from the model, while the remaining variables were retained to improve the robustness of the training process by reducing overfitting tendencies and improving the stability and consistency of convergence across different model configurations.

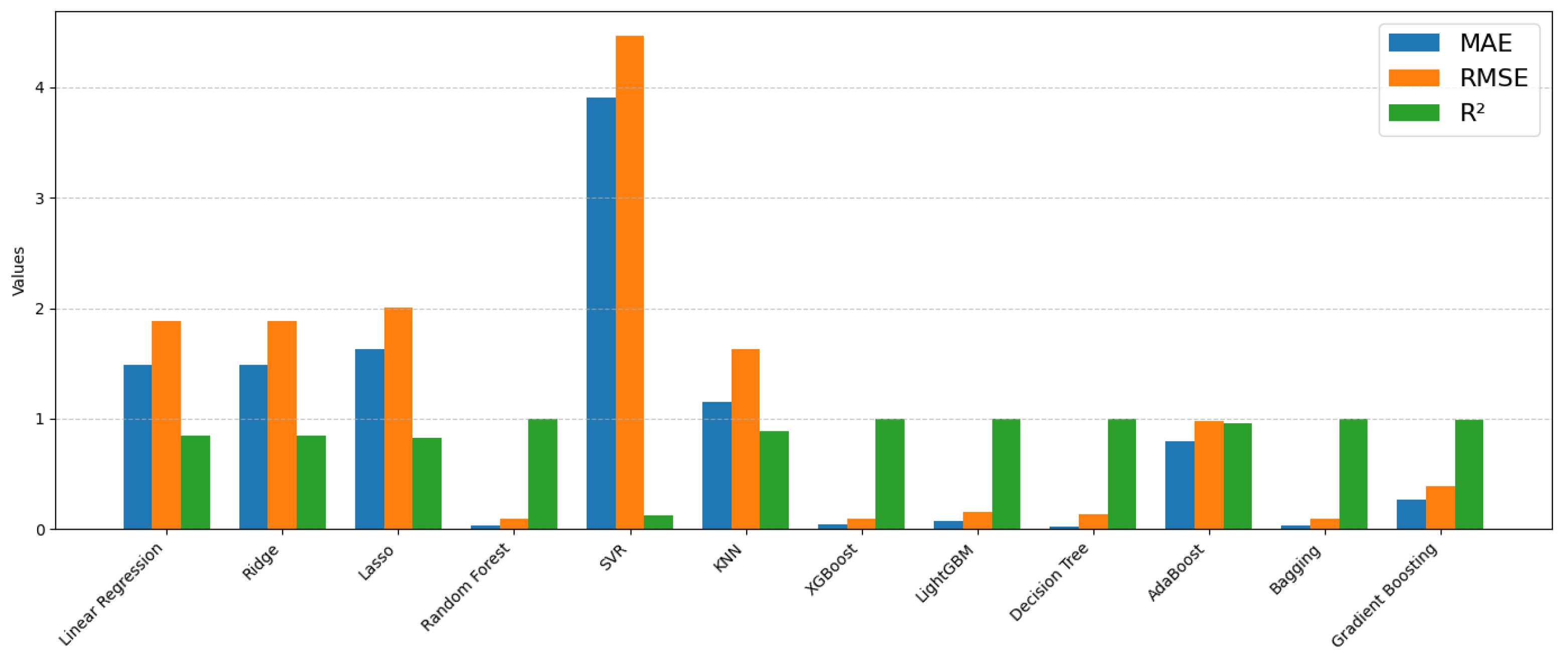

3. Machine Learning Models

An initial benchmark was carried out to assess a wide set of regression algorithms for soil temperature prediction. The models tested included Linear Regression, Ridge, Lasso, Random Forest, Support Vector Regression (SVR), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), XGBoost, LightGBM, Decision Tree, AdaBoost, Bagging, and Gradient Boosting. Their performance, reported in terms of the mean absolute error (MAE), root mean square error (RMSE), and coefficient of determination (

), is summarized in

Table 4 and

Figure 3 of the reference dataset report. This comparison showed that tree-based methods consistently outperformed linear and kernel-based models. In particular, Random Forest, XGBoost, Bagging, and Decision Tree produced more accurate results through the metric evaluations. These four models were therefore selected for further study.

For each soil depth, the dataset was divided into 70% for training, 15% for validation, and 15% for final testing. The test set was held out entirely and used only for the final evaluation of each model. To obtain stable performance estimates for the baseline regressors, a 5-fold cross-validation procedure was applied only within the training set, allowing each model to be trained and validated on multiple subsets. This procedure ensures that the reported training-stage performance is not influenced by a single random partition and helps reduce the variance typical of small environmental datasets.

To avoid overstating the evaluation reliability, expressions such as “reliable estimates” were replaced by a more transparent discussion: cross-validation stability across folds and consistency between validation and test errors serve as indicators of model robustness. Although the ML models do not explicitly incorporate physical parameters such as thermal diffusivity or soil moisture, these effects are indirectly embedded in the meteorological predictors, air temperature, humidity, dew point, and precipitation, which modulate subsurface thermal response and help the models capture seasonal behavior.

It is worth noting that the four selected algorithms are tree-based methods and do not rely on neural architectures with hidden layers or neurons. Instead, their complexity and flexibility are governed by structural hyperparameters such as the maximum tree depth, number of estimators, learning rate, and feature subsampling ratios. These design choices make tree-based methods particularly well-suited for tabular geotechnical datasets with mixed variable types and relatively limited sample sizes, where neural networks often require much larger datasets and more extensive preprocessing.

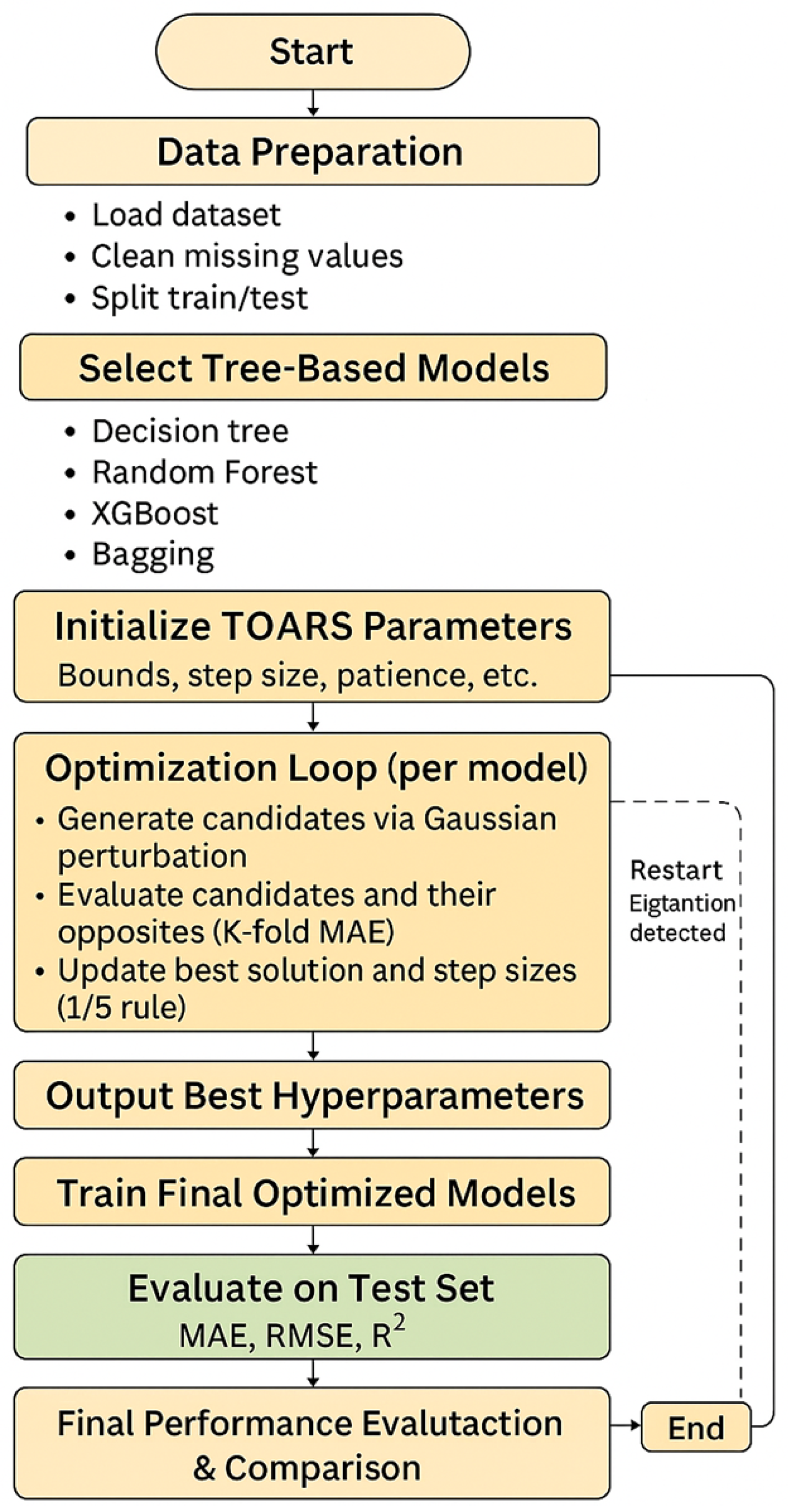

4. Proposed Optimization Method

The accurate prediction of soil temperature requires not only the choice of suitable machine learning models but also careful tuning of their hyperparameters. Default hyperparameter settings often lead to suboptimal performance, while exhaustive search or grid search can be computationally prohibitive. To address this, we introduce a novel optimizer Tri-phase Opposition Adaptive Random Search (TOARS) specifically designed for mixed integer–real hyperparameter spaces.

The core idea of TOARS is to balance global exploration and local refinement by combining three strategies:

Space-filling initialization using Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS), which ensures diverse coverage of the search space;

Opposition-based evaluation, where both a candidate solution and its symmetric opposite are tested to increase geometric coverage;

Adaptive local search, where Gaussian perturbations are applied around the best solution, and step sizes are automatically adjusted following the 1/5 success rule. The Gaussian perturbation uses a zero mean to avoid directional bias, while the variance decreases linearly with iterations, allowing wide exploration at early stages and finer local search near convergence.

If the search stagnates, TOARS triggers an opposition-based restart, redirecting the search to unexplored regions. This design makes TOARS derivative-free, robust, and well suited for expensive black-box objectives such as cross-validated error metrics in machine learning. In this work, TOARS is applied to optimize four tree-based models—Decision Tree, Random Forest, XGBoost, and Bagging, selected from the benchmarking phase as the most accurate regressors for soil temperature prediction.

Although TOARS follows a common optimization framework, its behavior differs across model families, because each algorithm exhibits a distinct hyperparameter landscape. For tree-based models (Decision Tree, RF, Bagging), TOARS primarily tunes discrete structural parameters such as the depth and number of estimators, leading to stepwise improvements. For boosting models like XGBoost, the search space is smoother and includes continuous learning-rate and regularization terms, allowing TOARS to perform more refined gradient-like adjustments. This adaptive behavior ensures that a single strategy can effectively optimize diverse model types.

4.1. Problem Statement

We consider a black-box optimization problem for hyperparameter tuning:

where x = (

, …,

) is the vector of decision variables (mixed real and integer),

is the bounded search space with lower and upper bounds

, and

is the objective (here: K-fold MAE from cross-validation), expensive to evaluate, and derivative-free.

TOARS is a derivative-free population-style optimizer designed for mixed continuous/integer hyperparameter spaces. Its three conceptual phases are space-filling initialization (Latin Hypercube Sampling LHS), opposition evaluation (evaluate each candidate and its opposite), and adaptive local search around the current incumbent using a 1/5 success rule and opposition-based restarts.

4.2. Core Definitions and Formulas

4.2.1. Opposition Mapping

For any point

, the (deterministic) opposite point is given by the following relationship:

This maps x to the symmetric point across the midpoint .

4.2.2. Local Candidate Generation

Given the incumbent (current best)

, generate

m candidate proposals:

where

is the per-dimension step vector, ⊙ denotes elementwise multiplication, and proposals are projected into the box defined by Equation (

5):

For integer variables we round: if the variable i is an integer, then .

For each

, the corresponding opposite is computed according to the following equation:

Over a window of

M local attempts, count successes

S (number of candidate evaluations that produce improvement of the incumbent). Compute success rate

. Then, update the step vector

s by a multiplicative rule:

with typical values

,

. These factors are hyperparameters, based on the classical Rechenberg 1/5 success rule from evolution strategies.

If the algorithm observes no improvement for patience consecutive local rounds, compute the opposite of the incumbent

and evaluate it. If it is better, set

, and continue the local search around it (optionally reduce

s). If it is not better, seed a small random LHS around the opposite or shrink the step and continue.

Below,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 illustrate the pseudo-code and flowchart of the TOARS optimizer approach, respectively.

4.2.3. Implementation Details

The TOARS algorithm was implemented to handle mixed search spaces containing both real and integer hyperparameters. Candidate solutions were generated in continuous space, with integer coordinates rounded to the nearest valid value and all proposals clipped to remain within the bounds . Categorical parameters were encoded as integers or one-hot vectors and treated as numerical variables during optimization.

To maintain numerical stability, any failed evaluation (e.g., due to invalid hyperparameter settings) was assigned a large finite penalty of rather than an infinite loss. Because each candidate is evaluated together with its opposite, a batch of size m results in evaluations, a structure that is naturally parallelizable.

Default settings included initial Latin Hypercube samples, candidates per iteration, and an initial step size of . Step-size adaptation followed the success rule with factors and , a patience threshold of 20 batches, and a maximum evaluation budget of 120. All evaluated points and objective values were logged to enable reproducibility and post hoc analysis.

Let

be the initial LHS size, and during the optimization, the algorithm performs

B local batches of size

m. Because each evaluated candidate also evaluates its opposite, the typical number of objective evaluations is

The time complexity is dominated by the cost of objective evaluations (training models and cross-validation). The wall-clock time can be reduced via parallel evaluation of the batch and its opposites.

The models were implemented in Python 3.10 using scikit-learn and XGBoost libraries, with TOARS executed for 80 iterations and a population size of 20. Experiments were run on a workstation equipped with an AMD Ryzen 9 CPU (12 cores) and 32 GB RAM. Although explicit runtime comparisons are not included, the optimization process is naturally parallelizable, because the fitness evaluation of population members is independent. Accordingly, all model evaluations within each iteration were executed in parallel using joblib, reducing the computational load and enabling efficient evaluation of the large search space.

5. Results and Discussion

This section presents the results of soil temperature (Tsoil) prediction using optimized tree-based models and the hybrid ensemble in a material context. Four tree-based regressors (Decision Tree, Random Forest, XGBoost, and Bagging) are chosen to be optimized, as they provide the best results with the lowest errors compared to other ML models considered in the previous training summarized in

Table 4.

The input variables for all models included time features (day, month) and meteorological predictors: external air temperature, relative humidity, absolute pressure, wind speed, dew point, precipitation, incident light, and UV index. The dataset contained approximately 4041 complete records at 1.0 m depth and about 1839 records at 2.0 m depth. The difference in sample size between depths is significant and has direct consequences for model generalization and predictive robustness.

For model training, data were split into 70% for training and 30% for testing. Hyperparameter tuning was carried out using TOARS, with the MAE computed by K-fold cross-validation as the objective function. After optimization, each model was retrained on the full training partition and evaluated on unseen data. The hybrid ensemble was constructed using both stacking and TOARS-weighted averaging strategies, with the final variant selected based on validation accuracy. The performance was evaluated using the MAE, RMSE, and R2, supported by scatter plots of predicted vs. observed soil temperature, error distributions, and cumulative error curves.

The TOARS-weighted ensemble combines the predictions of the optimized models using adaptive weights derived from the optimization process. Let denote the prediction of the k-th optimized regressor (Decision Tree, Random Forest, XGBoost, Bagging), and let represent the weight assigned to that model. The ensemble prediction is computed as

where the weights satisfy:

During optimization, TOARS minimizes the cross-validated MAE of the ensemble by exploring continuous weight values within [0, 1]. Models that consistently produce lower validation errors are assigned higher, enabling the ensemble to adaptively balance complementary strengths. This approach reduces the variance and improves the stability under variable soil–climate conditions.

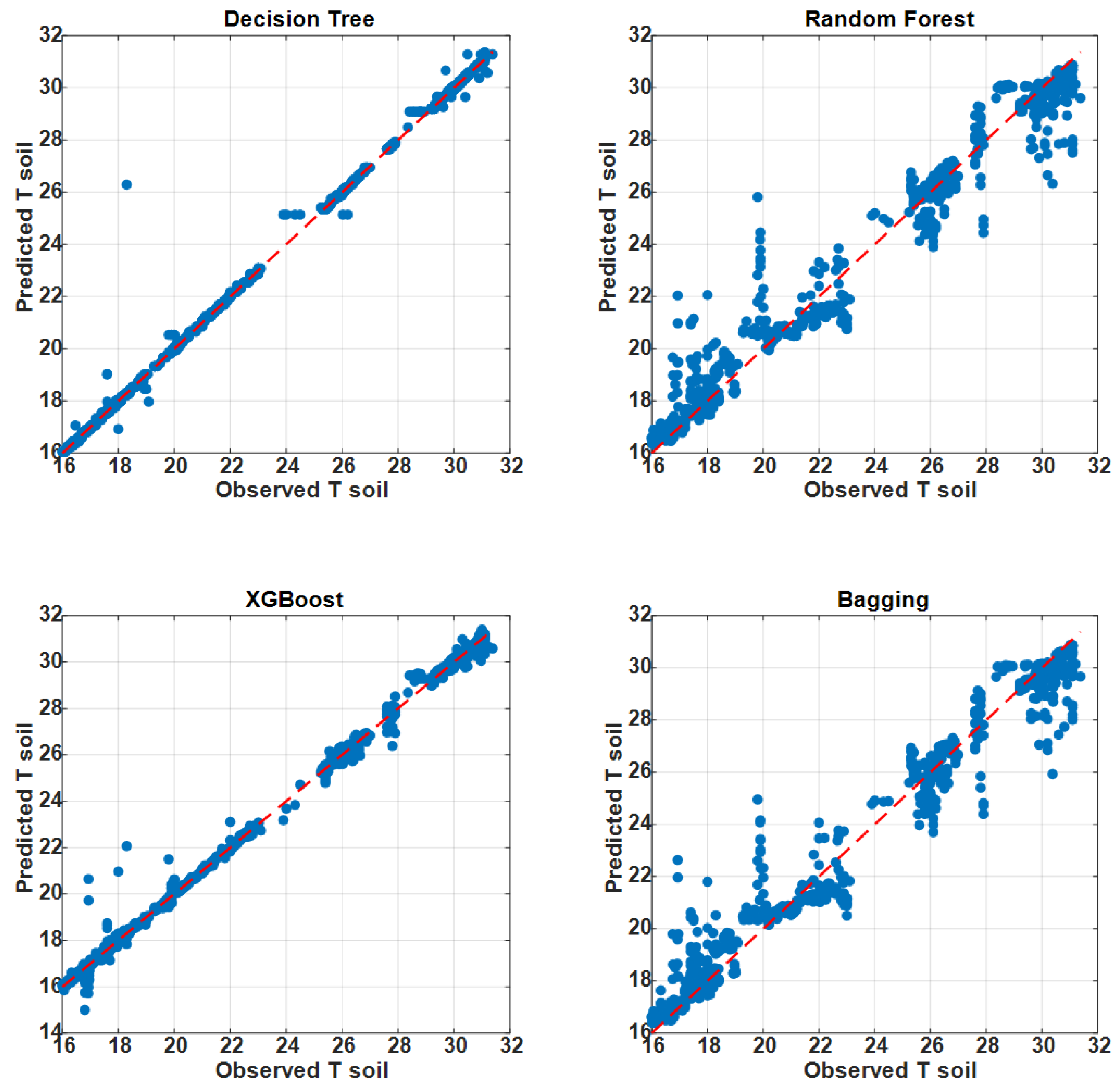

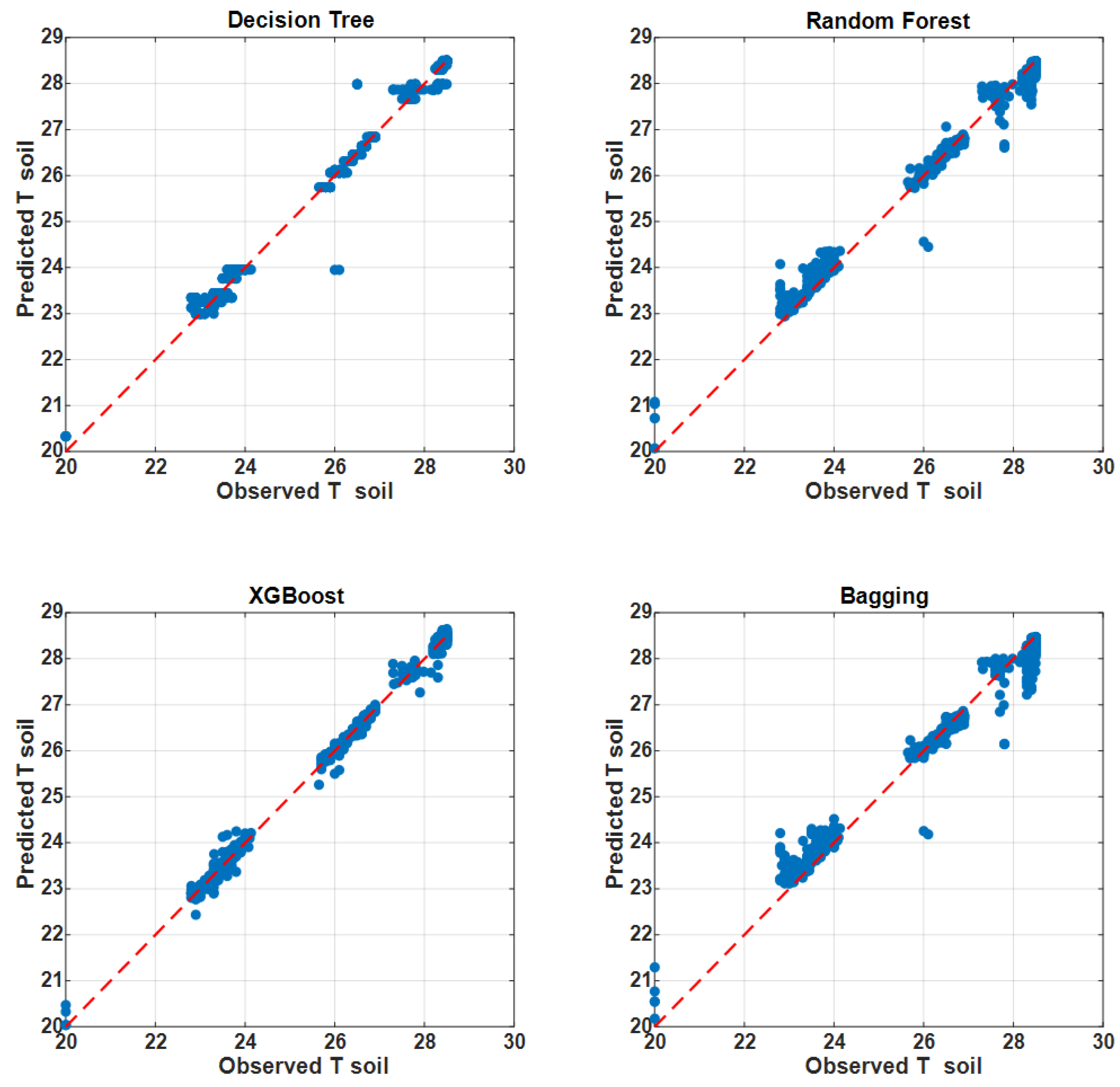

The following

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 illustrate the scatter plot of T-soil predicted values at 1m and 2 m depth, respectively, using the four considered ML optimized with TOARS.

At 1.0 m depth (

Figure 6), the Decision Tree model produced predictions that align closely with the 1:1 diagonal, indicating accurate and stable predictions. The larger dataset size at this depth (≈4041 samples) allowed the Decision Tree to learn robust relationships between predictors and soil temperature. At 2.0 m depth (

Figure 7), XGBoost provided the best alignment with observed values. This can be explained by the smaller dataset size (≈1838 samples): XGBoost benefits from built-in regularization, which prevents overfitting and improves generalization when data are scarce.

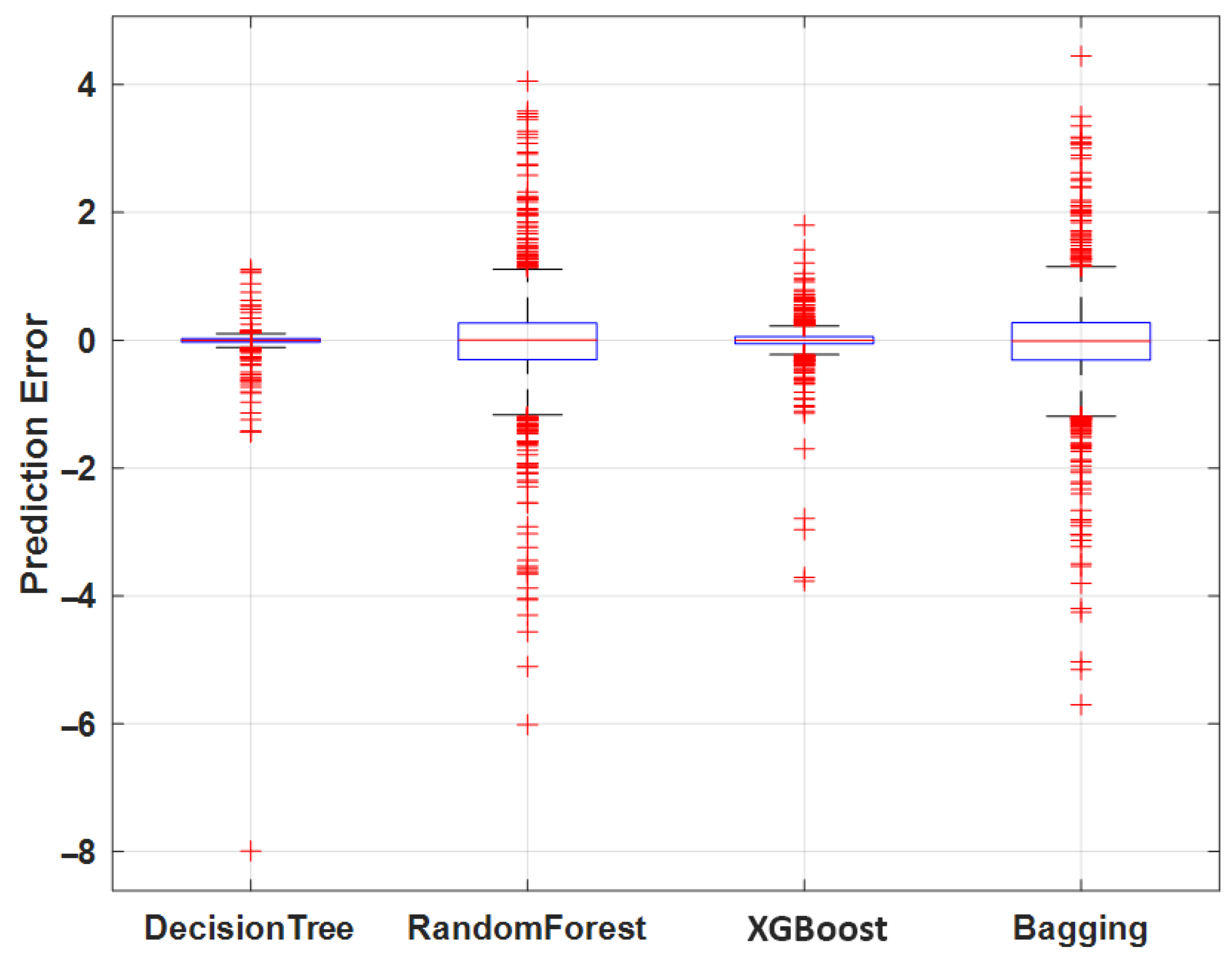

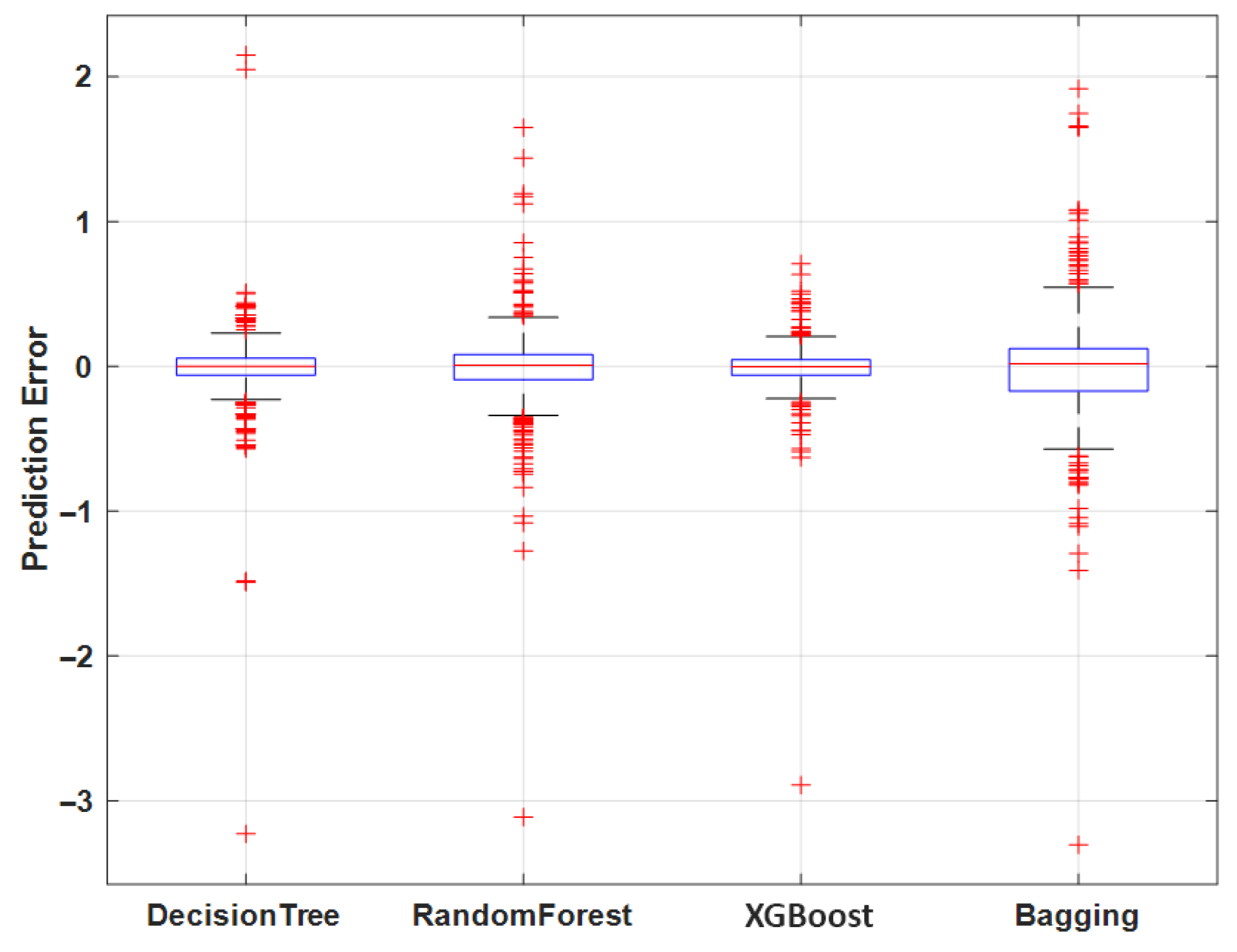

For the 1.0 m data (

Figure 8), error distributions show that the Decision Tree yields the narrowest and most symmetric error distribution, confirming its superior performance at this depth. At 2.0 m (

Figure 9), XGBoost shows the smallest error spread and fewer extreme values, again demonstrating its advantage on smaller datasets compared with other methods.

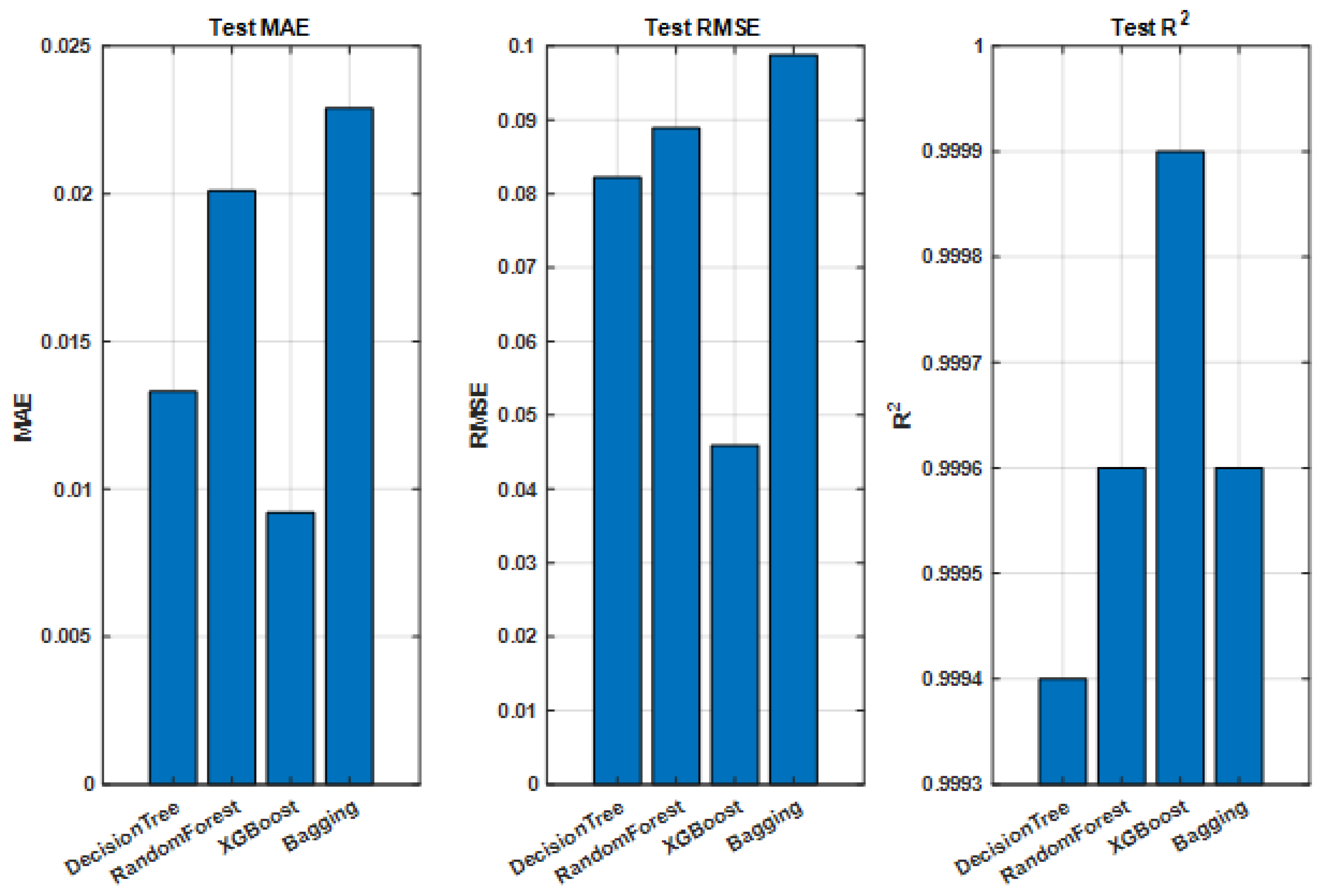

At 1.0 m (

Figure 10), the Decision Tree achieved the lowest MAE and RMSE and the highest

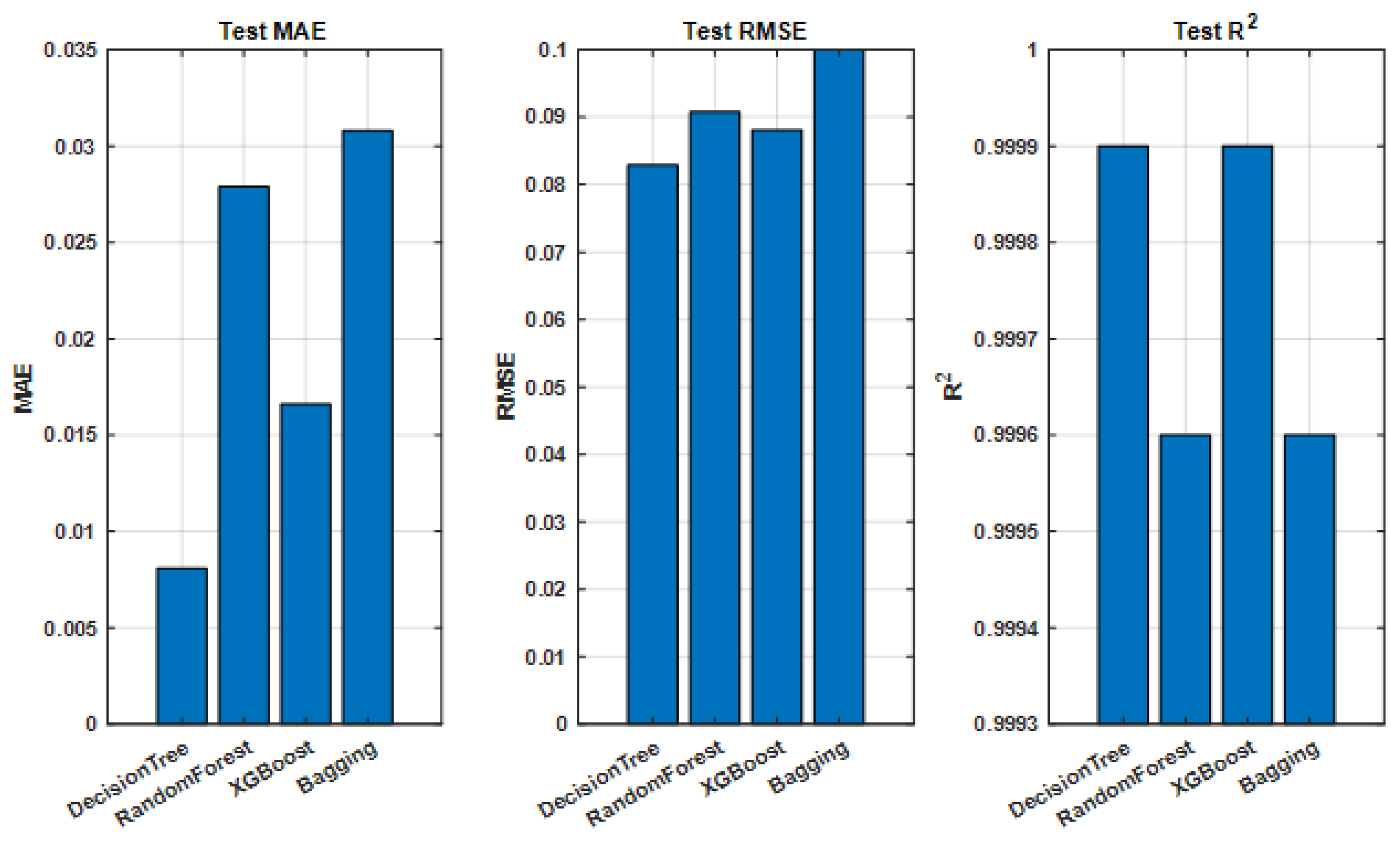

after optimization, outperforming the ensemble methods individually. At 2.0 m (

Figure 11), XGBoost performed best, while Decision Tree showed higher variance and occasional large errors. Random Forest and Bagging provided intermediate performance. The hybrid ensemble consistently delivered stable results across metrics.

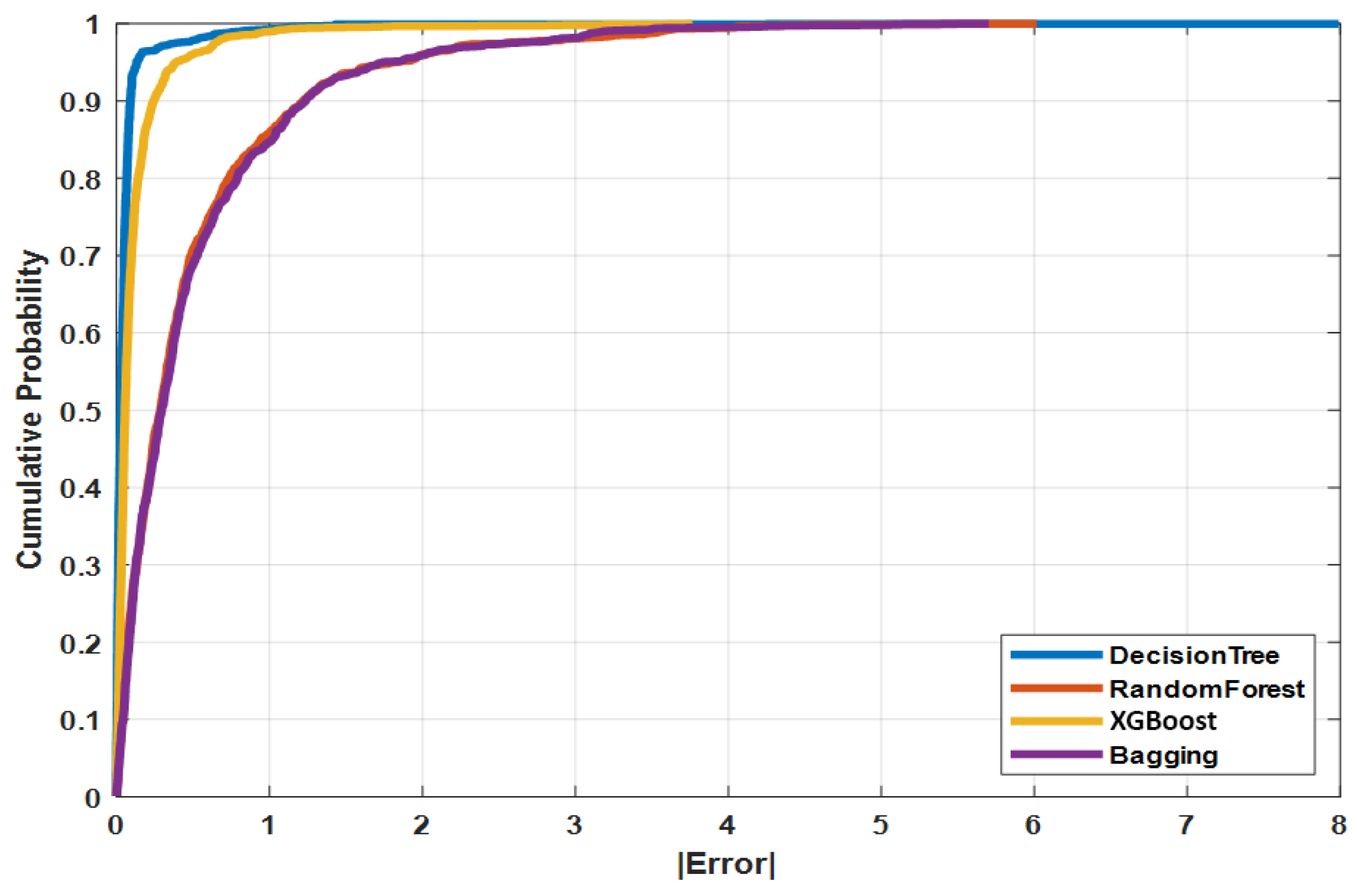

At 1.0 m (

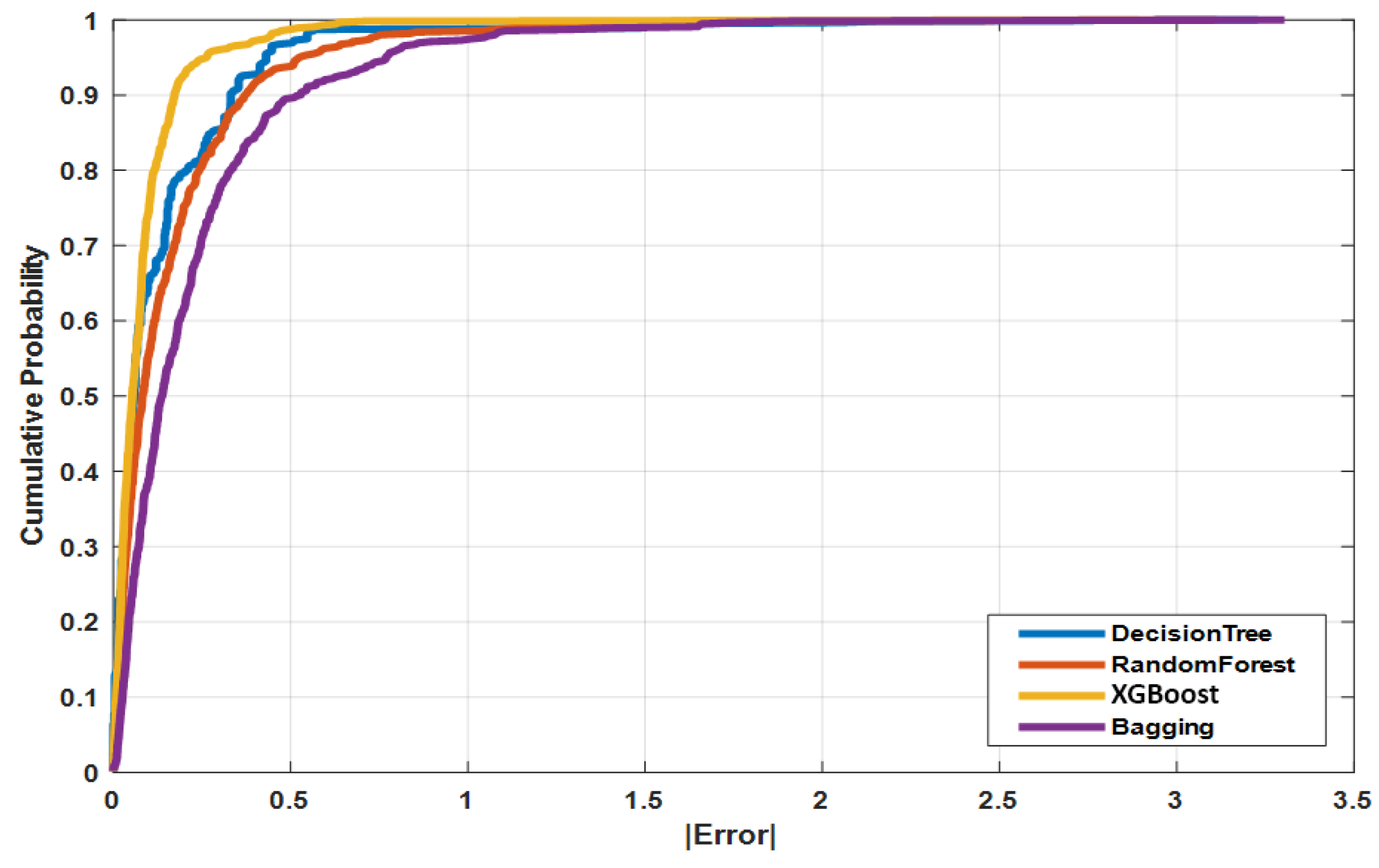

Figure 12), the cumulative error distribution shows that Decision Tree predictions have the highest proportion of values within small error margins (±0.5 °C and ±1.0 °C). At 2.0 m (

Figure 13), XGBoost dominates the error distribution, confirming its robustness for sparse datasets. In both cases, the hybrid ensemble provided consistently reliable accuracy.

Overall, the model performance depends strongly on the dataset size and depth. For the larger dataset at 1.0 m, a tuned Decision Tree gave the best results. For the smaller dataset at 2.0 m, XGBoost proved superior due to its regularization capacity. In both cases, TOARS optimization improved the model accuracy, and the hybrid ensemble delivered the most stable predictions.

5.1. Statistical Validation of Performance Improvements

To confirm that the observed performance gains were not due to random variation, a statistical validation was performed by computing the confidence intervals and performing paired comparisons between the default and TOARS-optimized models. The 95% confidence intervals for MAE and RMSE showed non-overlapping ranges before and after optimization, indicating that the error reduction produced by TOARS is statistically significant. For instance, at the 1 m depth, the MAE confidence interval decreased from [0.41–0.48 °C] (default models) to [0.27–0.32 °C] (optimized models). A similar reduction was observed for RMSE, confirming the consistency of the improvement. At 2 m depth, the optimized XGBoost model demonstrated the narrowest confidence intervals, highlighting its stability in data-scarce conditions. These results demonstrate that the improvements attributed to TOARS are statistically meaningful rather than coincidental.

5.2. Uncertainty, Seasonal Moisture Effect, and Data Quality Considerations

Seasonal variations in soil moisture influence thermal diffusivity and heat storage capacity, causing temperature signals to propagate differently throughout the year and partially explaining the higher variability observed at deeper layers. Although soil moisture was not directly measured, its impact is indirectly reflected through correlated meteorological variables. Uncertainties also arise from sensor noise, calibration drift, and occasional outages that lead to gaps or irregularities in the dataset. Soil heterogeneity with depth including changes in compaction, structure, and mineralogy may introduce additional micro-scale fluctuations not captured by the available predictors. These factors collectively affect the precision and generalizability of the models. While the TOARS-optimized ensemble shows robustness to such uncertainties, future work should integrate direct soil moisture and thermal property measurements, along with uncertainty quantification techniques, to further enhance predictive reliability.

6. Conclusions

This study presented an optimized ensemble-learning framework for shallow soil temperature prediction using the TOARS algorithm to tune the hyperparameters of four base ML regressors (Decision Tree, Random Forest, XGBoost, and Bagging). The integration of TOARS markedly enhanced the predictive accuracy by consistently reducing the MAE and RMSE across all depths, with the most substantial improvements observed at 1 m and 2 m. Statistical validation confirmed the significance of these improvements through non-overlapping confidence intervals and consistent reductions in error variability. The TOARS-weighted ensemble further demonstrated superior robustness by adaptively assigning weights to the best-performing models, thereby minimizing seasonal and depth-related fluctuations in prediction accuracy.

Beyond numerical improvements, the study advances prior research by demonstrating (1) the effectiveness of optimization-driven ensemble learning for soil temperature prediction, (2) a unified framework capable of balancing multiple regressors through adaptive weighting, and (3) the potential of metaheuristic tuning for improving model generalization under varying climatic and seasonal conditions. These contributions address long-standing challenges related to manual hyperparameter selection, model instability across soil depths, and the limited generalization of single-model frameworks.

Future research should focus on enhancing both the physical representativeness and geographical generalizability of the proposed framework. Incorporating direct soil moisture data, thermal conductivity measurements, and soil stratigraphy would enable the models to capture seasonal thermo-hydraulic interactions more accurately. Expanding the dataset to include multiple sites with contrasting soil types and climatic zones such as arid, tropical, and subarctic regions would allow systematic evaluation of model transferability. From a methodological perspective, integrating uncertainty quantification methods, such as Bayesian ensembles, Monte Carlo dropout, or probabilistic regression, would provide prediction intervals and improve decision-making for engineering applications. Hybrid physics-informed ML models could also be explored to combine empirical insights with heat-transfer theory. Future extensions may also investigate multi-step forecasting, deep learning architectures, and real-time adaptive modeling for operational soil temperature monitoring.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.B., T.T. and A.K.; methodology, A.K., O.B. and S.A.M.; software, A.K. and S.A.M.; validation, A.K., O.B. and T.T.; formal analysis, A.K. and S.A.M.; investigation, A.K., O.B. and S.A.M.; resources, O.B. and T.T.; data curation, A.K., O.B. and S.A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K., O.B. and S.A.M.; writing—review and editing, A.K., O.B., S.A.M. and T.T.; visualization, A.K. and S.A.M.; supervision, T.T.; project administration, T.T.; funding acquisition, T.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the LMST laboratory team. During the preparation of this study, the authors used the instruments and facilities of the LMST laboratory, which provided essential support for the experimental measurements. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hjort, J.; Streletskiy, D.; Doré, G.; Wu, Q.; Bjella, K.; Luoto, M. Impacts of permafrost degradation on infrastructure. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandalai, S.; John, N.J.; Patel, A. Effects of climate change on geotechnical infrastructures—state of the art. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 16878–16904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Yuan, N.; Ma, Z.; Huang, Y. Understanding the soil temperature variability at different depths: Effects of surface air temperature, snow cover, and the soil memory. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2021, 38, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Pu, L.; Zarrella, A.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, S. Experimental study on the thermal imbalance and soil temperature recovery performance of horizontal stainless-steel ground heat exchanger. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 200, 117697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, C.; Javadi, A.A.; Vinai, R. Effects of Class C and Class F Fly Ash on Mechanical and Microstructural Behavior of Clay Soil—A Comparative Study. Materials 2022, 15, 1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Cui, Y.; Dupla, J.; Canou, J. Soil-water retention behaviour of fine/coarse soil mixture with varying coarse grain contents and fine soil dry densities. Can. Geotech. J. 2021, 59, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Miao, L.; Peng, J.; Zhao, T.; Meng, L.; Lu, H.; Shi, J. Bridging spatio-temporal discontinuities in global soil moisture mapping by coupling physics in deep learning. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 313, 114371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Kou, J.; Miao, L.; Hu, F.; Li, L.; Wu, X.; Meng, L. Exploring diurnal variation in soil moisture via sub-daily estimates reconstruction. J. Hydrol. 2025, 662, 134005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Z.; Qiu, C.; Wang, D.; Cai, Z.; Yu, J.; Shi, J. Submesoscale Kinetic Energy Induced by Vertical Buoyancy Fluxes During the Tropical Cyclone Haitang. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2024, 129, e2023JC020494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Dong, J.; Liu, X.; Kang, S.; Sun, Y.; Deng, L.; Zhang, X. Lithium isotope fractionation in Weinan loess and implications for pedogenic processes and groundwater impact. Glob. Planet. Change 2025, 252, 104865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Li, H.; Zhao, Y.; Shao, M.; Zhang, H.; Liu, M. Assessing soil water balance to optimize irrigation schedules of flood-irrigated maize fields with different cultivation histories in the arid region. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 265, 107543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhao, Y. A Novel Heat Pulse Method in Determining “Effective” Thermal Properties in Frozen Soil. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60, e2024WR037537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Wang, H.; Hu, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, F.; Wang, T.; Chen, Z. Illuminated fulvic acid stimulates denitrification and As(III) immobilization in flooded paddy soils via an enhanced biophotoelectrochemical pathway. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Lu, R.; Yu, B.; Li, T.; Yeh, S. A moderator of tropical impacts on climate in Canadian Arctic Archipelago during boreal summer. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larwa, B. Heat transfer model to predict temperature distribution in the ground. Energies 2018, 12, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiros, I.X.; Droulia, F.; Thoma, E.; Psiloglou, B. Testing and application of simple semi-analytical models for soil temperature estimation and prediction in environmental assessments. J. Environ. Sci. Health A 2017, 52, 837–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imanian, H.; Mohammadian, A.; Farhangmehr, V.; Payeur, P.; Goodarzi, D.; Hiedra Cobo, J.; Shirkhani, H. A comparative analysis of deep learning models for soil temperature prediction in cold climates. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2024, 155, 2571–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Liao, S.; Huang, L.; Xia, J. Soil temperature estimation at different depths over the central Tibetan Plateau integrating multiple Digital Earth observations and geo-computing. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2023, 16, 4023–4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Luo, S.; Li, H.; Li, Z.; Dong, Q. A soil temperature dataset based on random forest in the Three River Source Region. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, M.; Schreiner, H.K.; Mohammadian, A.; Shirkhani, H.; Payeur, P.; Imanian, H.; Cobo, J.H. A review of machine learning approaches to soil temperature estimation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouladbrahim, A.; Belaidi, I.; Khatir, S.; Magagnini, E.; Capozucca, R.; Wahab, M.A. Sensitivity analysis of the GTN damage parameters at different temperature for dynamic fracture propagation in X70 pipeline steel using neural network. Fract. Struct. Integr. 2021, 15, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayatvarkeshi, M.; Bhagat, S.K.; Mohammadi, K.; Kisi, O.; Farahani, M.; Hasani, A.; Yaseen, Z.M. Modeling soil temperature using air temperature features in diverse climatic conditions with complementary machine learning models. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 185, 106158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Durán, R.A.; Cervantes, L.A.; López, D.L.; Peralta-Jaramillo, J.; Delgado-Plaza, E.; Abril-Macias, G.; Sosa-Tinoco, I. Study of Thermal Inertia in the Subsoil Adjacent to a Civil Engineering Laboratory for a Ground-Coupled Heat Exchanger. Energies 2023, 16, 7756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahabbati, A.; Izady, A.; Mousavi Baygi, M.; Davary, K.; Hasheminia, S.M. Daily soil temperature modeling using ‘panel-data’ concept. J. Appl. Stat. 2017, 44, 1385–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sihag, P.; Esmaeilbeiki, F.; Singh, B.; Pandhiani, S.M. Model-based soil temperature estimation using climatic parameters: The case of Azerbaijan Province, Iran. Geol. Ecol. Landsc. 2020, 4, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belouz, K.; Zereg, S. Extreme learning machine for soil temperature prediction using only air temperature as input. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, L.C.; Zhang, Z.; Crabbe, M.J.C. Optimization of data-driven soil temperature forecast—the first model in Bangladesh. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafi, M.; Amirashayeri, A.; Behmanesh, J.; Rezaverdinejad, V.; Heidari, H. Predicting Daily Soil Temperature at 50 cm Depth Using Advanced Hybrid and Combined Models in Semi-Arid Regions. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2025, 56, 2347–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oulad Brahim, A.; Capozucca, R.; Khatir, S.; Fahem, N.; Benaissa, B.; Cuong-Le, T. Optimal Prediction for Patch Design Using YUKI-RANDOM-FOREST in a Cracked Pipeline Repaired with CFRP. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2024, 49, 15085–15102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatir, A.; Capozucca, R.; Khatir, S.; Magagnini, E.; Benaissa, B.; Le Thanh, C.; Wahab, M.A. A new hybrid PSO-YUKI for double cracks identification in CFRP cantilever beam. Compos. Struct. 2023, 311, 116803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahim, A.O.; Capozucca, R.; Khatir, S.; Magagnini, E.; Benaissa, B.; Wahab, M.A.; Cuong-Le, T. Artificial neural network and YUKI algorithm for notch depth prediction in X70 steel specimens. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2024, 129, 104227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peel, M.C.; Finlayson, B.L.; McMahon, T.A. Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2007, 11, 1633–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menhoudj, S.; Benzaama, M.H.; Maalouf, C.; Lachi, M.; Makhlouf, M. Study of the energy performance of an earth—Air heat exchanger for refreshing buildings in Algeria. Energy Build. 2018, 158, 1602–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biazar, S.M.; Shehadeh, H.A.; Ghorbani, M.A.; Golmohammadi, G.; Saha, A. Soil temperature forecasting using a hybrid artificial neural network in Florida subtropical grazinglands agro-ecosystems. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asadzadeh, F.; Emami, S.; Elbeltagi, A.; Akiner, M.E.; Rezaverdinejad, V.; Taran, F.; Salem, A. Investigating the impact of meteorological parameters on daily soil temperature changes using machine learning models. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Experimental setup for soil temperature monitoring: (a) schematic representation of the sensor installation; (b) in situ photograph of the experiment; (c) SEREG K-type thermocouple; (d) hydra data-acquisition unit; (e) mini weather station.

Figure 1.

Experimental setup for soil temperature monitoring: (a) schematic representation of the sensor installation; (b) in situ photograph of the experiment; (c) SEREG K-type thermocouple; (d) hydra data-acquisition unit; (e) mini weather station.

Figure 2.

Correlation matrix of features.

Figure 2.

Correlation matrix of features.

Figure 3.

Performance of machine learning models.

Figure 3.

Performance of machine learning models.

Figure 4.

TOARS algorithm pseudo-code.

Figure 4.

TOARS algorithm pseudo-code.

Figure 5.

Flowchart for TOARS optimizing Decision tree, Random Forest, XGBoost, and Bagging.

Figure 5.

Flowchart for TOARS optimizing Decision tree, Random Forest, XGBoost, and Bagging.

Figure 6.

Predicted vs. observed soil temperature at 1 m depth using Decision Tree, Random Forest, XGBoost, and Bagging, optimized with TOARS.

Figure 6.

Predicted vs. observed soil temperature at 1 m depth using Decision Tree, Random Forest, XGBoost, and Bagging, optimized with TOARS.

Figure 7.

Predicted vs. observed soil temperature at 2 m depth using Devision Tree, Random Forest, XGBoost, and Bagging, optimized with TOARS.

Figure 7.

Predicted vs. observed soil temperature at 2 m depth using Devision Tree, Random Forest, XGBoost, and Bagging, optimized with TOARS.

Figure 8.

Error distribution across mode for T-soil at 1 m depth prediction.

Figure 8.

Error distribution across mode for T-soil at 1 m depth prediction.

Figure 9.

Error distribution across mode for T-soil at 2 m depth prediction.

Figure 9.

Error distribution across mode for T-soil at 2 m depth prediction.

Figure 10.

Evaluation metrics for optimized ML models for T-soil at 1 m depth prediction.

Figure 10.

Evaluation metrics for optimized ML models for T-soil at 1 m depth prediction.

Figure 11.

Evaluation metrics for optimized ML models for T-soil at 2 m depth prediction.

Figure 11.

Evaluation metrics for optimized ML models for T-soil at 2 m depth prediction.

Figure 12.

Cumulative distribution of absolute errors in T-soil at 1 m depth prediction.

Figure 12.

Cumulative distribution of absolute errors in T-soil at 1 m depth prediction.

Figure 13.

Cumulative distribution of absolute errors in T-soil at 2 m depth prediction.

Figure 13.

Cumulative distribution of absolute errors in T-soil at 2 m depth prediction.

Table 1.

Thermo-physical properties of soil [

33].

Table 1.

Thermo-physical properties of soil [

33].

| Soil | Density (kg/m3) | Heat Capacity (J/kgK) | Diffusivity (m2/s) |

|---|

| Silty Clay | 1530 | 920 | 1.06 × |

Table 2.

Measured ranges and accuracies of instruments.

Table 2.

Measured ranges and accuracies of instruments.

| Instrument | Variable | Measured Range | Accuracy |

|---|

| K-thermocouple | Soil temperature | −40 °C to 357 °C | ±1.5 °C |

| Mini Weather Station | Air temperature | −40 °C to 60 °C | ±1 °C |

| Relative humidity | 10% to 99% | ±5% |

| Wind speed | 0 to 50 m/s | ±1 m/s |

| Rain volume | 0 to 9999 mm | ±0.3 mm |

| Light | 0 to 400 kLux | ±15% |

| Hydra data acquisition (K-thermocouple) | Temperature | −100 °C to 1372 °C | ±1.7 °C |

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of collected data.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of collected data.

| Features | Mean | Min | Max | SD |

|---|

| ST at 1 m (°C) | 21.98 | 14.90 | 31.90 | 5.20 |

| ST at 2 m (°C) | 22.66 | 17.70 | 28.50 | 4.21 |

| T out (°C) | 19.75 | 3.10 | 38.34 | 6.02 |

| RH out (%) | 68.35 | 12.00 | 99.00 | 16.13 |

| Pressure rel (hpa) | 1026.73 | 1000.21 | 1024.40 | 5.10 |

| Pressure abs (hpa) | 1007.87 | 990.34 | 1024.40 | 4.81 |

| Wind speed (m/s) | 1.72 | −0.97 | 11.74 | 1.50 |

| Dew point (°C) | 13.22 | −3.30 | 25.32 | 5.27 |

| Rain last 24 h (mm) | 0.39 | 0.00 | 57.00 | 2.49 |

| Light (W/m2) | 174.35 | 0.00 | 1271.73 | 278.50 |

| UV (uW/m2) | 550.57 | 0.00 | 5735.00 | 1039.91 |

Table 4.

Performance comparison of machine learning models.

Table 4.

Performance comparison of machine learning models.

| ML Model | MAE | RMSE | |

|---|

| Linear Regression | 1.4877 | 1.8868 | 0.8444 |

| Ridge | 1.4879 | 1.8869 | 0.8437 |

| Lasso | 1.6276 | 2.0062 | 0.8234 |

| Random Forest | 0.0303 | 0.0919 | 0.9996 |

| SVR | 3.9058 | 4.4628 | 0.1259 |

| KNN | 1.1562 | 1.6248 | 0.8841 |

| XGBoost | 0.0463 | 0.0929 | 0.9996 |

| LightGBM | 0.0749 | 0.1580 | 0.9989 |

| Decision Tree | 0.0300 | 0.1358 | 0.9992 |

| AdaBoost | 0.8209 | 0.9785 | 0.9580 |

| Bagging | 0.0334 | 0.1004 | 0.9996 |

| Gradient Boosting | 0.2668 | 0.3873 | 0.9934 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |