Abstract

The digital economy, driven by data-enabled innovation, has become a critical engine for advancing agricultural modernization and promoting inclusive and sustainable rural revitalization in China. This study conceptualizes the rural revitalization system as an integrated system comprising five interconnected subsystems. A global parallel Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) model with shared inputs is developed to evaluate the total system and subsystem efficiencies of rural revitalization. In addition, quantification of the digital economy’s development level is achieved through the joint application of the entropy weight method and TOPSIS. Finally, based on a 2013–2022 panel of 31 provincial-level units in China, this paper identifies the impact and underlying mechanisms of the digital economy on the total system and subsystem efficiencies of rural revitalization. The findings reveal that (i) the digital economy significantly enhances rural revitalization efficiency, and this conclusion remains robust after addressing endogeneity and conducting multiple robustness tests. (ii) Heterogeneity analyses indicate that the digital economy contributes more in regions with lower rural revitalization efficiency, medium economic development, larger labor forces, or lower levels of Internet development. Furthermore, although digital economy does not have a significant impact on the subsystem efficiency of social etiquette and civility, its impacts on the remaining subsystem efficiencies are all significant. (iii) The impact of the digital economy on improving rural revitalization efficiency is mediated by technological innovation, and the expansion of the scale of non-agricultural employment enhances the promoting effect of the digital economy on rural revitalization efficiency.

1. Introduction

The 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China formally introduced the Rural Revitalization Strategy as a major national initiative designed to promote coordinated rural and urban development. Its core objectives include expediting the modernization of agriculture, narrowing the urban-rural disparity, and fortifying the institutional mechanisms that underpin sustainable development. Subsequent national directives, including the Opinions on Key Tasks for Advancing Rural Revitalization and the No. 1 Central Document, have consistently reaffirmed rural revitalization as the central task in agricultural and rural affairs in the new era. As a result, advancing rural revitalization has become an essential pathway toward achieving Chinese-style modernization. Within this strategic landscape, priority is given to integrating digital technologies, which are seen as indispensable for optimizing rural development capacity, broadening the reach of digital resources, and supporting a sustainable shift in agriculture.

Amidst China’s current push to accelerate the expansion of its digital sector, recent data reveals that the total volume of the country’s digital economy climbed to RMB 53.9 trillion in 2023, marking a year-on-year growth of RMB 3.7 trillion [1]. Moreover, digital economy growth contributed 66.45% to national GDP growth, highlighting its role as a core engine driving economic and social development. The digital economy facilitates the emergence of an ecosystem distinguished by economies of scale and scope, alongside long-tail effects [2]. By reshaping production factor allocation and lowering costs in agricultural production, circulation, and related sectors, it has become an important force in enhancing rural revitalization efficiency.

While the digital economy holds immense strategic value, its assimilation into rural revitalization is still in its infancy, and the specific pathways driving efficiency gains lack clarity. In contrast to the swift digital transformation observed in the secondary and tertiary sectors, the agricultural sector lags significantly. Data from 2023 reveals that the digital economy’s contribution to agricultural value-added is modest, amounting to less than 25% of the service sector’s level and under 45% of the industrial sector’s [3]. This indicates that digital application scenarios in agriculture are still limited, and the overall quality and depth of rural digitalization remain underdeveloped.

Against this backdrop, it is imperative to investigate how the digital economy enhances rural revitalization efficiency and to identify pathways for fostering sustainable rural transformation. Accordingly, this study quantifies the levels of rural revitalization efficiency and digital economy development, empirically examining their nexus and underlying mechanisms. Ultimately, the findings provide empirical evidence and policy implications for leveraging digital transformation to drive agricultural modernization and sustainable rural development in China.

Scholarly attention has increasingly centered on methodologies for assessing rural revitalization. Regarding the formulation of assessment frameworks, researchers predominantly anchor their indicators in the directives set forth by the State Council’s ‘Rural Revitalization Strategic Plan (2018–2022).’ This document underscores the five core pillars of ‘thriving businesses, pleasant living environment, social etiquette and civility, effective governance, and prosperity’ [4,5,6]. The measurement methods for assessing the overall development level of rural revitalization are based on the entropy weight method [6,7], principal component analysis [8], hierarchical analysis [9], and other index methods. However, the aforementioned index methods do not take into account the inputs of rural revitalization, which may give rise to an often overlooked yet significant issue—some regions with a high level of rural revitalization development may suffer from inefficiency due to excessive inputs, whereas regions with lower development levels might exhibit higher efficiency due to relatively low investments. Given the multi-input and multi-output characteristics of the rural revitalization system, it is challenging to derive a specific production function for decision-making units (DMUs). Since Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) does not require the estimation of production functions, it is commonly employed in measuring the production efficiency to effectively avoid model specification errors [10,11]. Existing research on efficiency in the rural context predominantly employs DEA and mainly falls into three streams, including studies on agricultural production efficiency [12,13], agroecological efficiency [14,15,16], agricultural funding support efficiency [17,18], and poverty-governance efficiency [19,20]. However, traditional parallel DEA models [21,22] fail to accurately capture the shared parallel production structure of the rural revitalization input-output system. This evaluation hurdle is addressed by parallel DEA models designed to handle shared input-output dependencies [23,24,25,26,27]. Nevertheless, there remains a lack of consensus on the measurement of rural revitalization efficiency in both academic and practical fields. This is mainly due to the fact that China’s rural revitalization program is designed as an integrated modernization program for agricultural and rural areas, executed through five interconnected aspects that progress in tandem [28]. These dimensions are defined by significant input sharing rather than completely distinct resource bundles since policy instruments and important inputs frequently serve many dimensions concurrently. Therefore, we use a shared-input parallel DEA framework to estimate the efficiency of rural revitalization and describe it as an overall system with five parallel subsystems. However, most existing shared-input DEA applications rely on contemporaneous frontiers, meaning that efficiency scores for different years are benchmarked against year-specific technologies. This feature weakens intertemporal comparability and makes it difficult to trace the dynamic evolution of rural revitalization efficiency over time.

Extensive scholarly attention has been dedicated to elucidating the semantics of the digital economy and gauging its maturity. From a generalized perspective rooted in digital technology, the digital economy is conceptualized as: “A spectrum of economic activities wherein digital information serves as the core production element, modern networks act as the pivotal carrier, and the efficient deployment of ICTs functions as the key engine for structural optimization and efficiency gains” [29]. Conversely, taking a more restricted scope, the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) originally categorized the sector into three distinct clusters of goods and services: infrastructure enabled by digital tech, electronic commerce, and digital media [30]. Contemporary quantification frameworks for the digital economy principally encompass national economic accounting systems, value-added estimation protocols, satellite account compilation, and the formulation of composite indices [31,32]. Notably, Bridgman et al. [33] expanded the BEA’s taxonomy by integrating digital services derived from high-tech consumer durables. In the context of Vietnam, Duc et al. [34] gauged the economic contribution of both conventional and digitalized sectors by deploying panel models grounded in digital spillover theory. Focusing on China, Xu et al. [35] utilized the entropy weight technique to assess the maturity of the urban digital economy. Similarly, in a provincial-level study (30 provinces), Li et al. [36] constructed an evaluation system predicated on a tripartite architecture.

With the digital economy becoming increasingly embedded in China’s broader economic system, a growing stream of research has examined its implications for rural development. Existing studies generally suggest that digitalization can support rural revitalization through multiple channels, spanning industrial upgrading, ecological improvement, cultural development, governance modernization, and livelihood enhancement [37], and that it has become a key lever for advancing rural development outcomes [4,35,38]. To illustrate, Tian et al. [39] elucidate that the digital economy acts as a catalyst for rural industrial resurgence by optimizing the efficacy of resource configuration, fortifying urban-rural market linkages, and expediting industrial coalescence. Expanding on this trajectory, Yan and Cao [40] postulate that the nexus between digital economic systems and rural industrial integration manifests potential non-linearities. In a parallel vein, Wang et al. [41] scrutinize the ramifications of the digital economy on the rejuvenation of rural industries. Notwithstanding these insights, extant scholarship has predominantly gravitated towards developmental magnitude or output performance, leaving a paucity of empirical inquiry regarding rural revitalization efficiency as a discrete evaluative criterion.

Adhering to the proposed analytical framework, this paper quantifies the level of digital economy development and rural revitalization efficiency to investigate their interrelationship and underlying mechanisms. First, regarding variable measurement, this study deconstructs the complex system structure of rural revitalization to measure its total and subsystem efficiencies via a shared parallel production process perspective, while simultaneously constructing a composite index for the digital economy using the entropy weight method combined with TOPSIS. Second, at the inter-provincial level, the study examines the spatial distribution characteristics of these two dimensions. In the final stage, the paper rigorously tests the impact of digitalization on revitalization efficiency, explicitly clarifying the transmission mechanisms served by technological innovation and non-agricultural labor engagement.

Relative to prior studies, this paper makes three main contributions: (a) This paper considers the rural revitalization system as consisting of five subsystems with shared inputs, and constructs a global DEA model with shared inputs to measure the efficiency of the total system and subsystem of rural revitalization, which has not been considered in previous studies in the literature [18]. (b) While most research has examined how the digital economy relates to the development level or performance outcomes of rural revitalization [42], we shift the focus to rural revitalization efficiency. (c) We investigate the mechanisms through which the digital economy affects efficiency, with particular attention to technological innovation and non-agricultural employment, thereby extending the analytical framework linking the digital economy to rural revitalization.

2. Theoretical Mechanisms and Research Hypotheses

This section primarily discusses the literature and formulates hypotheses in three key areas, including (1) the impact of the digital economy on rural revitalization efficiency; (2) studies considering the mediating effect of technological innovation; and (3) research on the moderating effect of non-agricultural employment.

2.1. Digital Economy and Efficiency of Rural Revitalization

While progress in China’s rural revitalization has been notable, formidable obstacles persist, particularly worsening income inequality [43]. The digital economy, aided by the internet’s extensive penetration, effectively overcomes the “last-mile” constraints hindering rural development, acting as a vital force for sustainable revitalization [44]. Furthermore, it aligns with the holistic framework of rural revitalization by improving the performance of the five subsystems: thriving businesses, pleasant living environment, social etiquette and civility, effective governance, and shared prosperity.

First, by fostering the evolution of rural industries, the digital economy contributes to improving the efficiency of thriving businesses. Grounded in factor allocation theory, digital technologies mitigate mismatches in capital, labor, and information, thereby optimizing the allocation of financial resources, facilitating labor mobility, and refining the deployment of production technologies.

Regarding financial inputs, the advancement of digital technology bolsters allocation efficiency and risk management capabilities. These improvements help transcend the physical and informational boundaries inherent in traditional finance and rectify the misallocation of credit resources [45]. In particular, the augmented transparency and fluidity of information, enabled by digitalization, empowers financial institutions to more accurately assess the dynamics of agricultural markets and the specific needs of farmers, effectively addressing the persistent challenges of financing for agricultural enterprises and individual farmers. In terms of production and R&D, the digital economy facilitates the efficient acquisition and processing of data across the entire agricultural value chain. This enhanced data accessibility heightens the precision and pertinence of agricultural R&D, thereby improving the operational efficiency and adaptability of agricultural machinery [46]. Furthermore, the digital economy enables the implementation of precise and intelligent management practices in agricultural production. By leveraging digital monitoring technologies to oversee the entire value chain of agricultural products, from cultivation to transportation and sales, agricultural production efficiency and resource utilization rates are effectively elevated, while simultaneously reducing production and transportation costs [47]. Leveraging rural e-commerce platforms enhances market efficiency, transcends geographical limitations and broadens sales channels for rural producers [48]. Additionally, the growth of the rural digital economy improves the standard of agricultural socialized services. This shift reduces farmers’ dependence on traditional experience for key inputs like fertilizers and pesticides, thereby curbing overuse and resulting in a significant decrease in agricultural carbon emissions [49].

Second, the digital economy holds the potential to enhance rural residential environments and improve the efficiency of pleasant living environment. From a capital investment perspective, big data analytics and cloud computing empower governmental bodies and financial institutions to monitor fiscal appropriations and credit flows in real-time. This capability facilitates the timely identification and mitigation of potential risks, ensuring that funds are precisely channeled toward rural environmental governance. On the output side, the integration of the digital economy with conventional rural sectors is conducive to mitigating pollution discharge and enabling the circular utilization of residential waste, thereby contributing to the improvement of rural living environments. Furthermore, the digital economy narrows the urban-rural disparity in access to resources and information, facilitating enhancements in rural infrastructure and living standards, thus elevating overall residential amenity [50].

Third, the digital economy possesses the capacity to fortify the construction of spiritual civilization and augment the efficiency of social etiquette and civility. Regarding factor inputs, the growth of digital media and streaming services is attributed to the advancement of digital infrastructure in rural areas. Capitalizing on low marginal costs and high-efficiency dissemination, these platforms not only enrich the spiritual lives of rural residents but also play a normative role in cultivating constructive values and behavioral norms. Furthermore, the urban-rural educational disparity is effectively reduced as online education streamlines the flow of premium educational resources across different regions [51]. On the output side, the digital economy revolutionizes rural cultural consumption. Digital technologies transcend geographical and transportation barriers, extending the reach of cultural products to remote areas. This accessibility significantly lowers the transaction costs of cultural consumption and expands consumption opportunities, thereby contributing to the accumulation of human capital and the elevation of cultural literacy among rural residents [52].

Fourth, the digital economy has the potential to drive the digital transformation of rural governance, thereby enhancing its efficiency. Drawing on institutional theory, digital governance and data-driven supervisory mechanisms bolster rule enforcement, improve transparency, and optimize service accessibility in rural areas. Specifically, the deployment of e-government platforms facilitates information disclosure and procedural transparency, laying a robust foundation for the modernization of rural governance capabilities. Furthermore, the application of digital technologies augments administrative oversight and regulatory capacity, leading to heightened efficiency in resource allocation, policy implementation, and risk assessment [53]. Moreover, the digital economy fosters the digital transformation of public services, not only improving their accessibility and convenience but also providing new tools and methods for poverty alleviation. Through big data analytics, governments can more accurately identify impoverished populations and formulate targeted poverty alleviation measures, ultimately assisting more rural residents in escaping poverty. Regarding the outcomes, the synergy between the digital economy and rural governance is demonstrated by the effective narrowing of the income gap between urban and rural areas [54]. It is noted that the financial earnings of rural residents are elevated, while social equity and stability are simultaneously reinforced. Consequently, the overall efficiency of rural governance is optimized through this mechanism.

Finally, the digital economy can effectively enhance income levels and improve the efficiency of prosperity. The digital economy, through platforms such as online platforms and inclusive finance initiatives, facilitates more rapid and efficient access to capital for rural residents engaging in entrepreneurial activities and other ventures, thereby contributing to the improvement of their living standards [42]. Furthermore, the widespread adoption and application of digital technologies reduce the cost of information acquisition, enabling rural residents to access market information more promptly and make more informed economic decisions. More importantly, digital platforms support remote work arrangements, mitigating traditional geographical limitations on economic opportunities and allowing rural residents to participate in broader market networks. This not only increases their employment opportunities but also enhances their earning potential. Concurrently, the digital economy itself is emerging as a significant avenue for proactive and flexible employment, providing diverse job opportunities for specific segments of society [55]. Therefore, the digital economy serves as a catalyst for both increased income and improved economic well-being in rural areas.

- H1.

- The digital economy drives the improvement of rural revitalization efficiency.

2.2. Digital Economy, Technology Innovation and Rural Revitalization Efficiency

The digital economy fosters technological innovation through multiple mechanisms, including enhanced resource allocation efficiency, broadened financing channels, and improved efficiency in translating research findings into practical applications. Digital technologies streamline the configuration of production inputs and maximize resource efficiency, thereby cutting production costs. Consequently, this financial relief spurs firms to increase their investment in technological innovation [56]. Moreover, accessibility to capital is broadened through the convergence of the digital economy and financial mechanisms. Consequently, substantial financial backing is afforded to initiatives focused on technological innovation [57]. Within the realm of agriculture, the pronounced information gap between borrowers (farmers and enterprises) and credit providers habitually results in significant financing hurdles. Specifically speaking, digital finance can mitigate information asymmetry and moral hazard [58], allowing financial institutions to more accurately assess the financial service needs of rural populations and enhance the efficiency of capital utilization. Wang and Wei [59] demonstrated that the digital economy increases patent application volume among China’s manufacturing enterprises, effectively improving their probability of obtaining patent grants.

Technological innovation, in turn, plays a crucial role in enhancing the efficiency of rural revitalization efforts. First, technological innovation contributes to improvements in the efficiency of thriving businesses and prosperity. It fosters industrial development and increases income levels to enhance agricultural production efficiency, promote value chain upgrading, and optimize resource allocation [42]. Second, technological innovation contributes to creating an ecologically livable environment in rural areas, among which green technology innovations can reduce pollution emissions and energy consumption, promote the green transformation of agricultural production and improve the rural ecological environment [60]. Third, technological innovation facilitates the digital transformation of rural governance, enhances its efficiency and transparency, and improves farmer participation and satisfaction. Concurrently, technology enriches the lifestyles of rural residents and fosters the modernization of traditional perspectives. The expansion of rural industries subsequently generates demand for improved governance and a richer cultural environment, establishing a positive feedback loop that comprehensively propels rural revitalization.

- H2.

- The digital economy influences the efficiency of rural revitalization through technological innovation.

2.3. Digital Economy, Non-Farm Employment and the Efficiency of Rural Revitalization

The level of non-agricultural employment influences the efficiency of rural revitalization driven by the digital economy through three key mechanisms: factor mobility, human capital accumulation, and income effects. First, the expansion of non-agricultural employment accelerates the bidirectional flow of labor, capital, and information between urban and rural areas, thereby creating the foundational conditions for optimizing factor allocation and embedding the digital economy into rural industrial systems. Second, regarding human capital accumulation, the cognitive upgrading associated with non-agricultural employment lowers the barriers to digital technology adoption. Through a “learning by doing” process, migrant workers acquire digital skills; upon returning to their hometowns for entrepreneurship or part-time employment, they generate significant technological spillover effects. These spillovers reduce the initial learning costs for other residents, fostering a conducive environment for digital applications. Specifically, returnees equipped with digital literacy can more effectively leverage e-commerce platforms to broaden sales channels and utilize big data analytics to optimize agricultural production processes. Third, higher non-agricultural income earned through labor migration leads to a reallocation of labor time and income [61]. The income effect of non-agricultural employment significantly enhances rural residents’ purchasing power and consumption preferences, stimulating demand for digital products and services. In turn, this increased demand further drives digital innovation and diffusion in rural areas.

- H3.

- The positive impact of the digital economy on rural revitalization efficiency can be strengthened as the level of non-agricultural employment increases.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Methodology for Measuring the Efficiency of Rural Revitalization

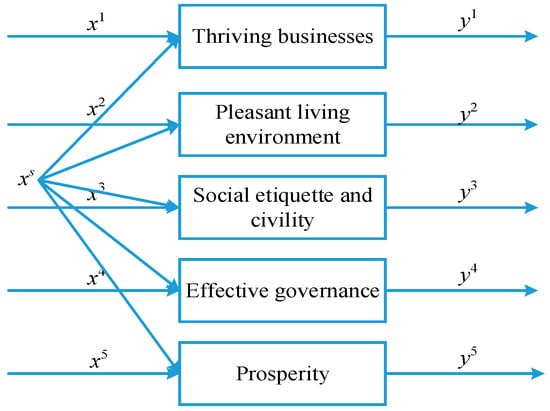

Recognizing that rural revitalization comprises multiple parallel subsystems drawing on a common pool of inputs, we measure efficiency using a shared-input global parallel DEA framework. This specification enables an explicit treatment of how shared inputs are distributed across parallel subsystems, which is not fully captured by conventional approaches such as network DEA or two-stage DEA [18]. In addition, the model constructs a single global production frontier using observations from all years, thereby reducing bias arising from interannual frontier shifts and enhancing the comparability of efficiency estimates across periods [20]. Related parallel DEA models have been extensively used to evaluate efficiency and productivity in sectors such as agriculture, transportation, and education [26,27,62,63,64]. In this study, rural revitalization inputs are organized into five categories, namely capital, labor, agricultural resources, education, and governance. Given the shared-input structure across subsystems, the corresponding input–output relationships are specified as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Rural revitalization in a parallel shared input-output process.

Figure 1 demonstrates that some inputs, including labor and capital, can be simultaneously utilized by several subsystems. Leveraging this input-output framework, this study aims to construct a parallel DEA model with shared inputs. However, the existing DEA models addressing shared inputs rely on period-specific (or local) production technologies to assess the efficiency of each DMU in various periods. A key limitation is that the efficiencies estimated using such localized production frontiers may not be directly comparable across different periods, thus hindering their applicability for evaluating the dynamic evolution of DMU’s efficiency [20]. To address the limitations of existing approaches, this paper aims to develop a global DEA model incorporating shared inputs, which also utilizes a unified benchmark for DMUs across different periods, thereby enabling the evaluation of performance in the rural revitalization system and its subsystems.

3.1.1. Global Parallel DEA Model with Shared Inputs

Suppose that there are DMUs to be evaluated and denote the -th Rural Revitalization System (RRS), . It is observed from Figure 1 that is decomposed into five sub-DMUs, written as , corresponding the five subsystems of the -th RRS. For each subsystem, the specific inputs, shared inputs, and outputs at period are, respectively, denoted as , , and , where . In addition, the shared-input allocation weights are subject to the following constraints: . Based on the input-output structure in Figure 1 and the notation above, we formulate the global shared-input parallel DEA model to evaluate the efficiency of the overall RRS as follows.

While Model (1) is originally specified as a linear fractional program, it can be converted into an equivalent linear program via the Charnes-Cooper transformation [65]. The corresponding linear model is shown below.

As shown models (1) and (2), refers to the DMU under assessment is global efficient at period , while the DMU with is considered be inefficiency.

3.1.2. Efficiency Decomposition

Below is a lower-overlap rewrite that preserves meaning and notation while improving academic tone and reducing long contiguous matches: Because Models (1) and (2) focus on the overall (system-level) efficiency of rural revitalization, they do not directly reveal how the subsystem efficiencies aggregate to the total-system performance. To make this connection explicit, we introduce an additive decomposition of the total efficiency, which allows us to examine the contribution of each subsystem to overall performance. For notational convenience, let the optimal solution to Model (1) be . Using these optimal weights, the efficiency of each parallel subsystem is defined as follows.

Building on the definitions of overall and subsystem efficiencies, we express the decomposition of total rural revitalization efficiency into subsystem components as follows.

It means that the total-system efficiency equals a convex-weighted sum of the efficiencies of the five subsystems.

3.2. Methodology for Measuring the Level of Development of the Digital Economy

An entropy-weighted TOPSIS method is adopted to construct the digital economy development index, following the steps outlined next.

3.2.1. Entropy-Weighted Method

The standardization methods for the positive and negative indicators are illustrated in Maps (5) and (6).

where () represents the value of the j-th dimension for the i-th sample. For convenience, the normalized data is uniformly denoted as .

The entropy value and coefficient of variation is calculated as follows.

where .

Let ; the following weight is calculated based on the coefficient of variation.

For the above weight and standardized variable, the score is calculated as follows:

3.2.2. TOPSIS Method

Based on the above scores, the maximum and minimum values can be, respectively, regarded as the positive and negative ideals.

Then, the Euclidean distance is computed as follows:

and

Finally, the final score is denoted as

3.3. Panel Regression Models

To evaluate the digital economy’s direct effect on rural revitalization efficiency, we specify the following baseline regression model:

As shown in model (15), represents the rural revitalization efficiency of i-th region at period t; captures the digital economy development level of the i-th region at period t; denotes the set of other control variables affecting the explanatory variables; and are region fixed effects and time fixed effects, respectively, and denotes the random disturbance term.

Additionally, the three-stage methodology proposed by Wen and Ye [66] is adopted in this section to investigate the underlying mechanisms.

In models (16) and (17), as a mediating variable, the presence of a mediation effect is determined by testing the significance of the regression coefficients ().

Ultimately, the model presented below is employed to investigate the moderating role of specific variables on the association between the digital economy and rural revitalization efficiency.

In this model, represents the moderating variable, and denotes the interaction term between the digital economy and the moderating variable.

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Variable Selection and Data Sources

4.1.1. Variable Selection

(1) Dependent Variable (Efficiency of Rural Revitalization). The specific input-output indicators are detailed in Table 1. Based on data availability and the functional logic of the Rural Revitalization Strategy, the indicator system aligns input resources with output welfare outcomes to ensure a rigorous and theoretically consistent assessment of rural revitalization efficiency.

Table 1.

Evaluation indicators for rural revitalization efficiency.

To rigorously evaluate rural revitalization efficiency, the construction of the indicator system is grounded in production theory and the functional logic of the Rural Revitalization Strategy. On the input side, the fundamental resources required for rural development are grouped into four dimensions: agricultural resources, fund, education and governance. Collectively, these dimensions capture the broad spectrum of resource conditions that shape rural revitalization, including production inputs, financial support, educational capacity and governance capability. Agricultural resources represent the material foundation of rural production and are measured using effective irrigation area and total agricultural power, which indicate land productivity potential and mechanization levels. Fund inputs reflect fiscal and credit support and are captured through expenditure on agriculture, forestry and water resources and agriculture-related loans. Education inputs indicate the availability of instructional and cultural service resources in rural areas and are measured through the number of full-time teachers in rural compulsory education and the number of rural cultural stations. Governance inputs capture institutional and administrative capacity and are represented by the coverage rate of village committees, which reflects organizational capability for policy implementation and resource coordination.

On the output side, the indicator system evaluates the holistic realization of rural revitalization goals. According to the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Promoting Rural Revitalization and existing literature [18,42,67,68], rural revitalization is structured around five key domains: thriving businesses, pleasant living environment, social etiquette and civility, effective governance and prosperity. These domains form the official policy architecture for rural revitalization and represent the full spectrum of economic, ecological, cultural, institutional and social outcomes that the strategy seeks to enhance. Together, they constitute an integrated and coherent system of revitalization goals, ensuring consistency with national policy and enabling a comprehensive assessment of revitalization performance. Thriving businesses reflects the vitality and competitiveness of rural industries as well as their capacity for sustainable growth. It is assessed using agricultural carbon emissions and the output value of agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry and fishery, which together indicate both environmental cost and industrial performance. Pleasant living environment reflects ecological governance and rural living conditions and is measured through sewage treatment capacity, the harmless disposal rate of household garbage and forest coverage, which together indicate ecological quality and environmental management. Social etiquette and civility reflects cultural development and human capital accumulation. It is captured through rural expenditure on education, culture and entertainment, average years of schooling in rural areas and the coverage of rural television programs. Effective governance reflects the capacity of rural governance systems to promote social equity and coordinated development and is measured through the consumption expenditure ratio and the income level ratio of urban and rural residents. Prosperity represents the overall improvement in rural living standards and the strength of social security, and is assessed using Engel’s coefficient, rural disposable income and the proportion of rural residents receiving minimum living guarantee.

To eliminate the impact of dimensional discrepancies between the data of different indicators on the evaluation results, this study standardizes the desirable (positive) and undesirable (negative) indicators by using Maps (5) and (6), respectively.

(2) Core Explanatory Variable (Level of Digital Economy Development). Drawing upon established indicator selection protocols [2,69,70], an evaluation index system for the digital economy is formulated, comprising three primary dimensions The detailed indicators are displayed in Table 2. This classification framework is consistent with mainstream measurement approaches in the digital economy literature and aligns with the availability and continuity of provincial-level data, thereby ensuring comparability across regions and years [71,72,73]. Specifically, the foundational prerequisites for digital advancement are reflected by the digital infrastructure dimension, while the growth status of digital industries is captured by digital industrialization. Furthermore, the depth of technology integration across other sectors is denoted by industrial digitalization. Collectively, a holistic and theoretically robust depiction of the digital economy’s development level is provided by this tripartite framework.

Table 2.

Digital economy level evaluation indicator system.

(3) Other variables

Based on the existing literature [74,75,76,77,78,79,80], the present study identifies and employs the following control, mediating, and moderating variables. These variables are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Other variables in the regression models.

4.1.2. Data Sources and Descriptive Statistical Analysis

This study analyzes relevant data from 31 provinces in China for the period 2012–2022 (excluding the Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan regions due to data availability). The data sources include the China Statistical Yearbook, China Population & Employment Statistical Yearbook, China Rural Statistical Yearbook, China Statistical Yearbook for Regional Economic, Qiyan China Big Data Platform for Social-Science (CBDPS), and the statistical yearbooks of individual provinces (regions, municipalities), among others. Missing and extreme data for certain regions and years are addressed using interpolation methods. Table 4 presents the descriptive statistics for the variables.

Table 4.

Results of descriptive statistics for main variables.

The empirical data reveals that rural revitalization efficiency (Rural) possesses an average of 0.781, alongside a maximum of 1, a minimum of 0.316, and a standard deviation of 0.195. This statistical profile signifies marked regional variations in economic development quality. Furthermore, the Digital Economy Development Index (Dige) manifests a trend typified as having a ‘low mean and high standard error.’ In terms of control variables, significant differences are evident across the various dimensions assessed.

4.2. Efficiency of Rural Revitalization and Level of Digital Economy Development

4.2.1. Efficiency of Rural Revitalization

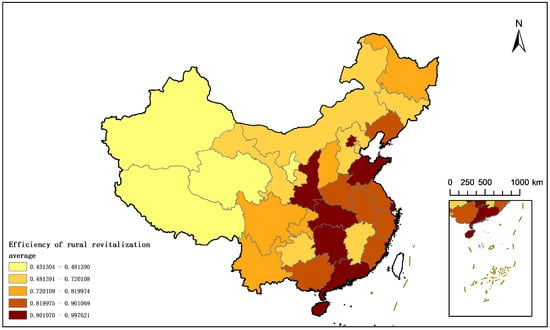

For a given RRS, the spatial distribution characteristics of rural revitalization efficiency are analyzed using ArcGIS 10.8 software based on the arithmetic mean of the total system efficiencies from 2013 to 2022. The results are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Efficiency (10–year average).

As illustrated in Figure 2, the spatial distribution of rural revitalization efficiency exhibits a distinct pattern characterized by a significant “East-High and West-Low” and “Multi-Polar Clustering”. Specifically, a pronounced east–west disparity is evident, with the eastern provinces demonstrating considerably higher rural revitalization efficiency compared to their western counterparts. This disparity may be attributed to the presence of more developed market systems and higher levels of marketization in the eastern regions, which facilitates more efficient resource allocation and consequently yields a higher input-output ratio in rural revitalization initiatives. Furthermore, the eastern regions possess a comparative advantage in capital deepening and technological innovation, which significantly enhances rural revitalization efficiency through multiple channels, including increased production efficiency, reduced unit costs, enhanced product added value, optimized management practices, and broadened market access. The spatial distribution of rural revitalization efficiency also demonstrates a clear tendency towards concentration, with clusters represented by the Central China Economic Zone and the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area emerging as core areas for enhancing rural revitalization efficiency, thus exhibiting the characteristic of “Multi-Polar Clustering”. The former is traditionally a major grain-producing region characterized by favorable soil conditions and convenient transportation, which supports agricultural development and enables economies of scale. The latter, by contrast, benefits from a higher level of economic development and access to a broader market.

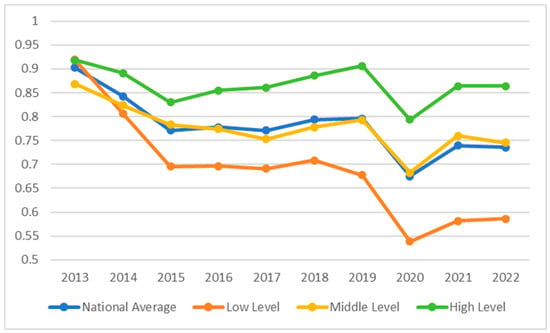

We further classify the 31 provinces into three economic-development groups (low, medium, and high) using ten-year GDP per capita as the criterion, and assess whether rural revitalization efficiency differs across these groups. Figure 3 summarizes the grouping scheme.

Figure 3.

Efficiency of rural revitalization with different economic development levels.

As reported in Figure 3, rural revitalization efficiency varies markedly with the level of economic development, with high-development regions consistently outperforming the medium- and low-development groups. This may be attributed to the more optimized resource allocation in these areas, which includes dimensions such as fiscal investment, infrastructure improvement, and human capital accumulation. Between 2013 and 2015, there is little change in rural revitalization efficiency, with a general trend of slow decline. From 2015 to 2019, a notable upward trend in rural revitalization efficiency is observed, largely due to the continuous improvement of the policy system, increased fiscal investment, accelerated infrastructure development, and enhanced human capital accumulation. In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic causes a relatively sharp decline in efficiency values, but in the subsequent years, they gradually return to normal levels. In contrast to the steadily increasing rural revitalization development level [35], it is evident that the changes in rural revitalization efficiency do not exhibit a consistent upward trajectory. In regions with lower levels of economic development, the overall downward trend in efficiency persists. This trend indicates a potential gap between “quantitative growth” and “qualitative improvement” in the execution of the rural revitalization strategy. In other words, while increasing output has been prioritized, policymakers may have devoted insufficient attention to improving efficiency, optimizing structural arrangements and strengthening long-term sustainability.

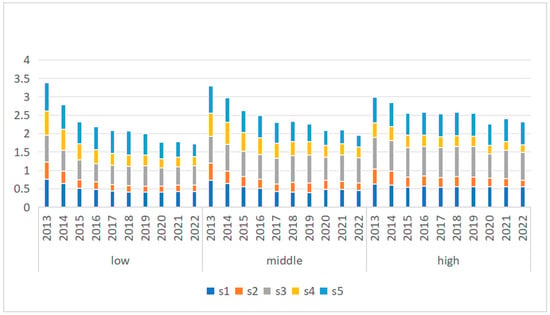

To clarify cross-subsystem differences, this study calculates the efficiency of each rural revitalization subsystem drawing on the results in Figure 3. The full set of subsystem estimates is displayed in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Efficiency of rural revitalization subsystems.

As illustrated in Figure 4, marked heterogeneity characterizes the evolution of rural revitalization subsystems across regions of varying economic stature. Specifically, the efficiency of thriving businesses (s1) demonstrates the most robust performance, maintaining elevated levels regardless of location. This implies that spatial divergences in agricultural and rural industrial progression are minimal. Conversely, the efficiency of the pleasant living environment (s2) is generally low nationwide, though economically developed regions achieve comparatively higher levels, likely due to more comprehensive policy frameworks and more effective administrative management that support better resource allocation and ecological improvement. The efficiency of social etiquette and civility (s3) is significantly lower in economically underdeveloped regions, reflecting how lagging economic conditions restrict improvements in cultural literacy and reduce residents’ participation in building rural spiritual civilization. Regions with medium levels of economic development exhibit relatively strong effective governance efficiency (s4), benefiting from sound policy implementation and well-established governance structures. Finally, prosperity efficiency (s5) is highest and most stable in economically developed regions, which can be attributed to their favorable business environments and broader employment opportunities.

4.2.2. Level of Digital Economy Development

Similarly, based on the arithmetic mean of the digital economy development level from 2013 to 2022, the spatial distribution characteristics are discussed by using ArcGIS 10.8 software. The specific results are presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Distribution of the level of development of the digital economy (10–year average).

A pronounced stratified spatial configuration regarding China’s digital economy is delineated in Figure 5. Crucially, the role of principal engines is assumed by the eastern coastal zones. These areas benefit from concentrated innovation infrastructure and robust ecosystems of flagship firms, resulting in the formation of comprehensive digital industry agglomerations. The central region, while possessing a large population base, experiences a relative deficiency in per capita digital resource endowment. This structural paradox underscores a developmental asymmetry in the central digital economy, characterized by asynchronous “scale expansion” and “quality enhancement”. Development in the western region is heterogeneous, with certain provinces capitalizing on energy resources or niche industries to engage in the digital transformation. Nevertheless, the western region generally encounters persistent issues of infrastructural limitations and regional disparities.

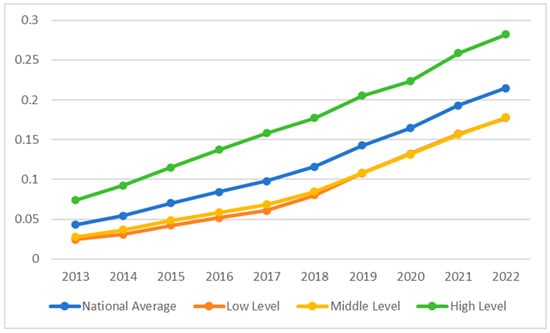

Additionally, Figure 6 delineates the evolutionary trajectory of the digital economy spanning 31 Chinese provinces throughout the decade of 2013–2022. It simultaneously maps performance across regions stratified into low, medium, and high tiers, anchored in per capita GDP. The intent of this analysis is to scrutinize the dynamics of digital economic maturity within territories possessing divergent economic foundations.

Figure 6.

Development level of digital economy with different economic development levels.

Figure 6 shows a sustained upward trend in China’s digital economy over the past decade. At the same time, development remains uneven across regions, and the observed “digital divide” is consistent with disparities in infrastructure provision and access to information. Economically developed regions exhibit the highest levels of digital economic development, while the disparity in digital economy levels among other regions is relatively small. This is primarily due to the advanced infrastructure, abundant high-quality talent resources, and the more favorable policies and technological advantages available in the economically developed regions. In contrast, other regions continue to fall behind in infrastructure development and talent allocation. In addition, deficiencies in local laws, regulatory frameworks and innovation incentive policies restrict the inflow and scaling of digital capital, thereby dampening the growth momentum of the digital economy in these areas.

4.3. Regression Analysis

4.3.1. Baseline Regression

Section 4.2.1 and Section 4.2.2 indicate that while rural revitalization efficiency exhibited stability with a marginal rise (2013–2022), the digital economy demonstrated sustained growth. To scrutinize the nexus between these dynamics, Table 5 summarizes the estimation results derived from a two-way fixed-effects specification.

Table 5.

Baseline regression results.

As detailed in Table 5, the coefficient associated with Dige is positive and significant, providing robust support for H1. This confirms that the digital economy plays a constructive part in augmenting rural revitalization efficiency.

4.3.2. Endogeneity Test

Potential endogeneity concerns are addressed by applying both the instrumental variables (IV) method and dynamic panel analysis.

(1) Instrumental variables method

Adopting the instrumental variable (IV) construction methodology outlined by Huang et al. [81], the penetration rate of fixed-line telephony across provinces during 1984 is selected as the instrumental variable. This choice is justified on two grounds: first, historical communication infrastructure exhibits a strong correlation with contemporary digital economy development, thereby meeting the validity requirement regarding IV relevance; second, as a historical lag, it does not directly affect current rural outcomes. In light of the cross-sectional nature of the historical postal and telecommunications data, we further apply the approach of Nunn and Qian [82], constructing the instrumental variable as the interaction term between the 1984 fixed-line telephone penetration rate and the national information technology service revenue of the preceding year for regression analysis. Finally, the 2SLS results are presented. The estimates in columns (7) and (8) of Table 6 are consistent with the baseline regression.

Table 6.

Endogeneity test results.

(2) Dynamic Panel Analysis

Rural revitalization efficiency may exhibit lag effects, whereby improvements in previous periods also influence current performance. To address this dynamic relationship, we introduce a one-period lag of rural revitalization efficiency, thereby forming a dynamic panel data structure. Subsequently, to verify the results, we employ the system Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) technique to analyze the correlation between these two variables. Column (9) reports these findings.

4.3.3. Robustness Analyses

To further validate the reliability of the findings, three robustness checks are conducted: (1) lagging the core explanatory variable; (2) adjusting the sampling timeframe to 2013–2019 to exclude the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic; (3) two-sided trimming test (two-sided winsorization at the 1% and 99% levels was performed on the data). The results reported in Table 7 align with the baseline regression findings.

Table 7.

Robustness test results.

4.3.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

(1) Quantile regression

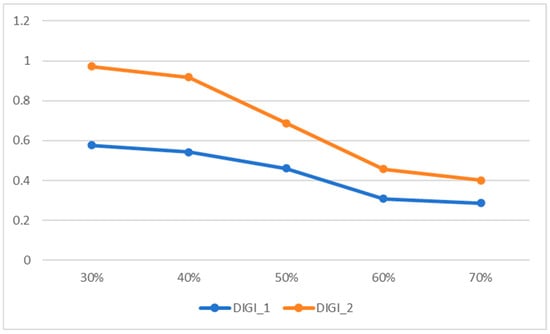

Extending the preceding analysis, a panel quantile regression framework [83] is utilized to probe whether the impact of digital economic advancement on rural revitalization efficiency exhibits heterogeneity across diverse segments of the efficiency distribution. Figure 7 shows that for rural revitalization efficiency levels within the 30th to 70th percentile range, the coefficients of both DIGI_1 and DIGI_2 (DIGI_1 without control variables and DIGI_2 with control variables) display a declining trend. The digital economy exerts a stronger promoting effect in regions with lower levels of rural revitalization efficiency, largely because these areas face more pronounced deficiencies in infrastructure, information accessibility and governance capacity. Digital technologies can directly alleviate these structural bottlenecks, yielding greater marginal benefits. This pattern is consistent with the law of diminishing marginal returns and the “latecomer advantage”, whereby regions starting from a lower baseline experience more substantial gains from digitalization. By contrast, regions with higher rural revitalization efficiency already benefit from more advanced infrastructure and more mature governance and industrial systems. Consequently, the marginal utility derived from additional digital inputs diminishes, thereby attenuating the stimulatory impact of the digital economy in regions characterized by high efficiency.

Figure 7.

Digital economy quantile regression coefficients.

(2) Different level of economic development

This study categorizes the samples into three groups-low (Column 14), medium (Column 15), and high (Column 16)-based on their mean per capita GDP over the period 2013–2022. The corresponding results are reported in Table 8.

Table 8.

Heterogeneity results under different economic development levels.

Columns (14)–(16) show that the effect is statistically significant in the high- and medium-development groups (with coefficients of 0.469 and 1.254, respectively) and is strongest in the medium-development group, whereas it is not significant in the low-development group. A reasonable explanation lies in their unique position within the development spectrum. On the one hand, medium-level regions generally possess a relatively sound market environment, adequate industrial foundations, and increasingly improved digital infrastructures, enabling the digital economy to be effectively integrated into agricultural production, rural governance, and public service delivery. On the other hand, unlike highly developed regions where further digital investment may face diminishing marginal returns, medium-level regions retain substantial room for productivity improvement, structural upgrading and efficiency gains. As a result, digital development generates larger marginal benefits in these areas. By contrast, in low economic development regions, weak infrastructure, limited human capital and constraints on technology diffusion reduce the ability to convert digital inputs into tangible rural revitalization outcomes. In highly developed regions, although the digital economy sustains a constructive influence, the incremental benefits tend to be smaller due to saturation effects and already optimized resource allocation.

(3) Different size of the labor force

In this study, labor force size is represented by the 10-year average population density across provinces (averaged over 2013–2022). Based on this measure, the sample is categorized into three groups: low-density (Columns 17), medium-density (Columns 18), and high-density (Columns 19).

The estimates reported in Table 9 indicate that the effect of the digital economy on rural revitalization efficiency differs across labor-force-size subgroups. Notably, in regions with a substantial labor pool, a significant positive effect is observed at the 5% significance level. A reasonable explanation is that abundant labor resources strengthen the complementary relationship between digital technology and human capital. Regions with larger labor pools tend to have greater potential for human capital accumulation, higher labor mobility, and more diversified skill structures, which together enhance the absorption, utilization, and diffusion of digital technologies. In such contexts, digital platforms, smart agriculture technologies, and information-based governance tools can be more effectively deployed, thereby generating stronger marginal gains in rural revitalization efficiency. In regions with a medium labor force size, the effect is positive but not statistically significant, suggesting that these areas remain in a transitional stage where labor resources and digital capabilities are improving but have not yet reached the threshold necessary to generate substantial efficiency gains. By contrast, regions with a small labor force show a non-significant negative effect, possibly reflecting constraints in digital literacy, infrastructure and human capital that limit the effective utilization of digital technologies.

Table 9.

Heterogeneity results under different labor force sizes.

(4) Different levels of internet development

We employ the number of Internet users as an indicator of internet development, thereby reflecting regional disparities in digital infrastructure and penetration. Based on the average user count across the study period, provinces are classified into a low-development cohort (Column 20) and a high-development cohort (Column 21).

Table 10 demonstrates that the digital economy significantly fosters rural revitalization efficiency specifically in regions with lower internet development, as opposed to those with higher development where the impact is negligible. This finding suggests that the digital economy has greater potential to generate efficiency gains in areas where internet development is still at a relatively low stage, as these regions retain substantial room for improvement in information access, market connectivity, and governance capacity. By contrast, in regions with more mature Internet infrastructure and higher penetration, the marginal efficiency gains brought by further digital development are comparatively limited, which may lead to an insignificant coefficient.

Table 10.

Heterogeneity results under different levels of internet development.

(5) Subsystem efficiency of the rural revitalization

The assessment framework for rural revitalization efficiency consists of five subsystems: thriving businesses (s1), pleasant living environment (s2), social etiquette and civility (s3), effective governance (s4), prosperity (s5). The regression results are presented in Table 11.

Table 11.

Heterogeneity results for different subsystems of rural revitalization.

The efficiency of s1, s2, s4, and s5 is found to be significantly improved by the digital economy. However, the digital economy shows no significant impact on the “social etiquette and civility(s3) “subsystem. This finding is largely attributable to the intrinsic characteristics of the subsystem’s output indicators. The outcomes associated with social etiquette and civility represent slow-moving social and cultural transformations that rely on long-term behavioral accumulation, sustained investment in education and cultural services, and the gradual internalization of social norms. These outcomes typically evolve over extended time horizons and do not respond immediately to short-term fluctuations in external inputs. Although digital technologies can enhance information access and diversify cultural exposure in the short run, such improvements do not directly or rapidly translate into measurable cultural advancement. This misalignment between the temporal dynamics of inputs and outputs creates a structural lag, thereby weakening the immediate observable effect of the digital economy on this subsystem. Moreover, social etiquette and civility often depend on deeper institutional, familial, and community-level interactions, which cannot be substantially altered by digital interventions alone, further explaining the lack of short-term statistical significance.

4.3.5. Path Analysis

(1) Impact mechanism test of technology innovation

As shown in Columns (27)–(29) of Table 12, technology innovation plays a fully mediating role in the impact of the digital economy on rural revitalization efficiency, and this mediating effect is further confirmed by the Sobel test, which demonstrates H2. Improvements in rural revitalization efficiency are achieved by the digital economy through the stimulation of technological advancements. This is achieved as digitalization facilitates superior acquisition of information, capital, and collaborative networks, thereby dismantling barriers to innovation and fostering the genesis and propagation of novel technologies. Driven by this mechanism, rural sectors transition towards optimized production modalities, refine the configuration of resources, and fortify governance capabilities, ultimately culminating in heightened revitalization efficiency.

Table 12.

Path analysis regression results.

(2) Moderating effect

The interaction term combining the digital economy and non-agricultural employment yields a statistically significant positive coefficient of 0.148 (at the 1% level), thereby validating H3. This finding implies that non-agricultural employment acts as a catalyst, intensifying the nexus between digital economic progress and rural revitalization efficiency. A probable mechanism is that robust non-agricultural employment facilitates labor mobility, skills enhancement, and income diversification, which empowers rural residents to harness digital technologies effectively.

Using threshold regression as a robustness check (Table 12, Column 31), the digital economy’s coefficient registers a jump from 0.676 (sub-threshold) to 1.803 (supra-threshold). This attests that the propulsive impact of the digital economy on rural revitalization is amplified in contexts of high non-agricultural employment, verifying the postulated moderating channel.

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendation

5.1. Conclusions

Utilizing panel data spanning 31 provincial-level regions in China from 2013 to 2022, this research examines how the digital economy influences rural revitalization efficiency and identifies the mechanisms driving this process. To quantify both rural revitalization efficiency and digital economy development, we integrated a global parallel DEA model (featuring shared inputs) with the entropy weight-TOPSIS method. Subsequent empirical testing was conducted using two-way fixed effects, along with mediation and moderation models. The analysis yields three primary conclusions: First, the digital economy significantly drives improvements in rural revitalization efficiency, a finding validated through extensive endogeneity and robustness checks. Second, heterogeneity analysis demonstrates that the efficacy of the digital economy varies contingent upon regional disparities in rural revitalization stages, economic development, labor force scale, and internet infrastructure. At the subsystem level, while significant positive impacts are observed in thriving businesses, pleasant living environments, effective governance, and prosperity, the effect on social etiquette and civility is not statistically significant. Third, technological innovation serves as an important mediating variable and represents a key pathway through which the digital economy enhances rural revitalization efficiency, underscoring the importance of innovation in enabling digital empowerment of rural revitalization. Moreover, it is observed that non-agricultural employment significantly bolsters the efficacy of the digital economy in driving rural revitalization.

5.2. Policy Recommendation

Drawing upon the empirical conclusions, this study puts forward the following policy implications.

First, strategic priority should be assigned to the consolidation of digital infrastructure and the extensive application of the digital economy in rural zones. In view of the digital economy’s substantial constructive influence on revitalization efficiency, authorities at all tiers should channel greater fiscal resources towards rural digital hardware, encompassing broadband connectivity, digitized service hubs, and smart agrarian platforms. Building on this prerequisite, efforts should pivot towards the infusion of digital solutions into agricultural operations, rural cultural evolution, and grassroots administration. Such initiatives will propel the ‘digital village’ agenda, optimize governance mechanisms, and lay a robust foundation for sustainable revitalization.

Second, fostering the coupling of technological breakthroughs and the digital economy is necessary to cultivate fresh momentum. Empirical evidence suggests that technological innovation is an important mechanism through which the digital economy enhances rural revitalization efficiency. Therefore, by capitalizing on digital infrastructure to facilitate the seamless flow of innovation resources, regions can significantly drive the modernization and efficiency upgrading of their agricultural value chains. In parallel, It is imperative to establish sound incentive mechanisms, such as innovation subsidies, talent policies, and intellectual property protections, to encourage active participation of enterprises and research institutions in innovation activities aligned with rural revitalization needs. This approach will help foster innovation vitality and continuously enhance rural revitalization outcomes.

Thirdly, the implementation of multifaceted employment strategies is essential to capitalize on the moderating capacity of non-agricultural employment. Analysis confirms that non-farm work amplifies the digital economy’s constructive influence on revitalization efficiency. Therefore, the government should adopt measures to broaden non-agricultural employment channels. On one hand, substantial support must be directed toward platform-driven sectors, particularly rural e-commerce and creative cultural tourism. Such measures are vital for expanding the range of job options available to rural dwellers and streamlining the workforce’s transition into the digital economy. On the other hand, targeted vocational training and career development programs should be developed to enhance rural workers’ competitiveness in digital industries. Simultaneously, refining the social welfare system is key to upholding the rights of non-agricultural laborers and promoting stable labor market evolution.

Finally, policy measures must be tailored to address the heterogeneities revealed in the analysis. Regions with medium levels of economic development should prioritize strengthening digital infrastructure and platform accessibility, as they have the highest marginal gains from digital adoption. Areas with larger rural labor forces should promote digital skills training, agricultural e-commerce participation, and labor-oriented digital public services to fully leverage scale and diffusion effects. Regions with lower levels of Internet development should further expand connectivity and digital access, as they gain the most from improvements in digital infrastructure. These tailored policy pathways can better accommodate regional differences and ensure that the digital economy contributes effectively to all dimensions of rural revitalization.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Z.X. and H.X.; Writing—original draft, Z.X. and H.X.; Writing—review & editing, Z.X. and H.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- China Academy of Information and Communications Technology. Research Report on the Development of China’s Digital Economy (2024); China Academy of Information and Communications Technology: Beijing, China, 2024; Available online: https://www.caict.ac.cn/kxyj/qwfb/bps/202408/P020240830315324580655.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Zhao, T.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, S. Digital economy, entrepreneurship, and high-quality economic development: Empirical evidence from urban China. J. Manag. World 2020, 36, 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- China Academy of Information and Communications Technology. White Paper on China’s Digital Rural Development Practices (2024) (No. 202402); China Academy of Information and Communications Technology: Beijing, China, 2024; Available online: https://www.caict.ac.cn/english/research/whitepapers/202411/P020241129593420524416.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Wang, J. Digital inclusive finance and rural revitalization. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 57, 104157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Huang, Y.; Yang, L. Rural revitalization in China: Measurement indicators, regional differences and dynamic evolution. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, Y.; Liu, L.; Chen, L. Rural revitalization of China: A new framework, measurement and forecast. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2023, 89, 101696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Jiang, M.; Sun, D.; Zhang, S. Does financial development matter the accomplishment of rural revitalization? Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2023, 88, 620–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Q.; Yao, W. Digital governance and its benchmarking college talent training under the rural revitalization in China-A case study of Yixian County (China). Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 984427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Wang, H.; Yang, J.; Feng, Y. Reconstructing village spatial layout to achieve rural revitalization: A case from a typical township in China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1168222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W.; Rhodes, E. Measuring the efficiency of decision making units. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1978, 2, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banker, R.D.; Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W. Some models for estimating technical and scale inefficiencies in data envelopment analysis. Manag. Sci. 1984, 30, 1078–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Jiang, Y.; Mu, H.; Yu, Z. Efficiency evaluation and improvement potential for the Chinese agricultural sector at the provincial level based on data envelopment analysis (DEA). Energy 2018, 164, 1145–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manogna, R.; Mishra, A.K. Agricultural production efficiency of Indian states: Evidence from data envelopment analysis. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2022, 27, 4244–4255. [Google Scholar]

- Bonfiglio, A.; Arzeni, A.; Bodini, A. Assessing eco-efficiency of arable farms in rural areas. Agric. Syst. 2017, 151, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Ding, T.; Nie, L.; Hao, Z. Agricultural eco-efficiency loss under technology heterogeneity given regional differences in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 250, 119511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zou, L.; Wang, Y. Spatial-temporal characteristics and influencing factors of agricultural eco-efficiency in China in recent 40 years. Land Use Policy 2020, 97, 104794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Na, S.; Guo, L.; Chen, J.; Ruan, Z. External financing efficiency of rural revitalization listed companies in China—Based on two-stage DEA and grey relational analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, T.; Wang, N.; Xiao, H.; Zhou, Z. Efficiency of funding to rural revitalization and regional heterogeneity of technologies in China: Dynamic network nonconvex metafrontiers. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2024, 92, 101825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Wang, Y.; Chang, H.; Chen, Q. Evaluating anti-poverty policy efficiencies in China: Meta-frontier analysis using the two-stage data envelopment analysis model. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2022, 14, 416–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Wang, N.; Wang, S. Dynamic sustainability assessment of poverty alleviation in China: Evidence from both novel non-convex global two-stage DEA and Malmquist productivity index. Oper. Res. 2023, 23, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, C. Efficiency measurement for parallel production systems. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2009, 196, 1107–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuyama, H.; Weber, W.L. A slacks-based inefficiency measure for a two-stage system with bad outputs. Omega 2010, 38, 398–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, W.D.; Hababou, M. Sales performance measurement in bank branches. Omega 2001, 29, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, P.F.; Molinero, C.M. A variable returns to scale data envelopment analysis model for the joint determination of efficiencies with an example of the UK health service. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2002, 141, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Du, J.; Sherman, H.D.; Zhu, J. DEA model with shared resources and efficiency decomposition. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2010, 207, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Y.; Hu, M.; Xu, H. Measuring efficiencies of parallel systems with shared inputs/outputs using data envelopment analysis. Kybernetes 2015, 44, 336–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Li, F. Performance evaluation of Chinese research universities: A parallel interactive network DEA approach with shared and fixed sum inputs. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2023, 87, 101582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Wang, Q.; Ren, T.; Zhou, Z. Efficiency analysis of funding resources for rural revitalization in China based on the concept of sustainable development: Evidence from parallel DEA with shared inputs/outputs and Tobit models. Oper. Res. 2025, 25, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyberspace Administration of China. G20 Digital Economy Development and Cooperation Initiative; Cyberspace Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2016. Available online: https://www.cac.gov.cn/2016-09/29/c_1119648520.htm (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Barefoot, K.; Curtis, D.; Jolliff, W.; Nicholson, J.R.; Omohundro, R. Defining and Measuring the Digital Economy; US Department of Commerce Bureau of Economic Analysis: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Volume 15, p. 210.

- Xu, X. Changes in the Core Indicators of China’s National Economic Accounting: From MPS National Income to SNA Gross Domestic Product. Soc. Sci. China 2020, 10, 48–70. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q. Does the digital economy promote the consumption structure upgrading of urban residents? Evidence from Chinese cities. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2024, 69, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgman, B.; Highfill, T.; Samuels, J. Introducing consumer durable digital services into the BEA digital economy satellite account. Telecommun. Policy 2024, 48, 102618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duc, D.T.; Dat, T.T.; Linh, D.H.; Phong, B.X. Measuring the digital economy in Vietnam. Telecommun. Policy 2023, 48, 102683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhong, M.; Dong, Y. Digital economy and risk response: How the digital economy affects urban resilience. Cities 2024, 155, 105397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Chen, H.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, T.; Wang, L. Digital economy, financing constraints, and corporate innovation. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2023, 80, 102081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Huang, M.; Peng, R. The impact of digital economy on rural revitalization: Evidence from Guangdong, China. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.; Wang, Y.; Yao, S. Impact of agricultural science and technology innovation resources allocation on rural revitalization. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1396129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Liu, Q.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Khanal, R. How the Rural Digital Economy Drives Rural Industrial Revitalization—Case Study of China’s 30 Provinces. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Cao, X. Digital Economy Development, Rural Land Certification, and Rural Industrial Integration. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Peng, T.; Du, A.M.; Lin, X. The Impact of the Digital Economy on Rural Industrial Revitalization. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2025, 76, 102878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhong, M.; Dong, Y. Digital finance and rural revitalization: Empirical test and mechanism discussion. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 201, 123248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y. Public service equalization, digital financial inclusion and the rural revitalization: Evidence from Chinese 283 prefecture-level cities. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 96, 103648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Huang, Y.; Dong, H.; Zhou, X.; Wang, Y. The measurement, sources of variation, and factors influencing the coupled and coordinated development of rural revitalization and digital economy in China. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0277910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhong, M.; Cao, M. Does digital investment affect carbon efficiency? Spatial effect and mechanism discussion. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 827, 154321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, R.; Ren, S. The Impact of Rural Digitalization on Agricultural Green Total Factor Productivity. Reform 2022, 12, 102–118. [Google Scholar]

- Hrustek, L. Sustainability driven by agriculture through digital transformation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, P.K.; Singh, R.; Gehlot, A.; Akram, S.V.; Das, P.K. Village 4.0: Digitalization of village with smart internet of things technologies. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 165, 107938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Feng, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, N.; Cao, F. Can the development of the rural digital economy reduce agricultural carbon emissions? A spatiotemporal empirical study based on China’s provinces. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 939, 173437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.; Xiao, Y.; Hu, B. Digital financial inclusion, industrial structure and urban–Rural income disparity: Evidence from Zhejiang Province, China. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, Q. Meritocracy, Suzhi Education and the Use of Live-Streaming Technology in Rural Schools in Western China. China Q. 2023, 259, 645–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Liu, Z.; Huang, R. A Study on the Influence of Digital Economy on the Cultural Consumption Gap between Urban and Rural Areas from the Perspective of Spatial Effect. Econ. Probl. 2023, 5, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Shi, J.; Bai, J. Evaluating the synergistic effects of digital economy and government governance on urban low-carbon transition. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 105, 105337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hainan, L.; Feng, F.; Wu, X. Digital economy, education, human capital and urban–rural income disparity. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 71, 106464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Lyu, K. The impact of digital economy on emerging employment trends: Insights from the China Family Panel Survey (CFPS). Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 64, 105418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Li, Y.; Niu, X.; Liu, M. The impact of digital economy on regional technological innovation capability: An analysis based on China’s provincial panel data. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0288065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]