Abstract

Construction logistics is central to optimising site operations and delivery processes, yet the need to meet dynamic site requirements while minimising transport movements presents a persistent challenge. Transport efficiency can be improved through both strategic and operational interventions at the business-unit level. This study examines transport-related distribution practices within the plasterboard supply chain in Auckland, New Zealand, and evaluates opportunities to enhance efficiency using established performance metrics. By integrating supply chain management and circular economy principles through spatial analysis and supply chain modelling, the research demonstrates the potential to achieve up to a three-fold improvement in vehicle capacity utilisation. The operational analysis—focused on general-purpose (non-specialist) transport—is grounded in real-world transport data that extends beyond conventional trip-centricity to capture a broader supply chain perspective. This approach addresses a key methodological gap by empirically validating analytical models in a specific operational context. In addition to quantifying efficiency gains, the study identifies context-specific inefficiencies that constrain construction transport performance and proposes sustainable solutions that extend beyond technological fixes. These include strategic organisational measures for improving fleet management, transport contracting and pricing, collaborative planning across supply chain actors, waste management practices, and collaborative logistics through integrated warehousing. By linking technical analysis with business-oriented insights, the research provides proof-of-concept for practical, scalable strategies for improved construction logistics and wider freight transport efficiency grounded in empirical evidence.

1. Introduction

The construction industry, contributing circa 13% of global Gross Domestic Product, drives employment, infrastructure development, and business growth. The industry consumes nearly 36% of global energy and emits approximately 39% of carbon emissions [1,2]. Construction projects, which bring together diverse resources into complex artifacts [3,4,5], rely heavily on logistics to manage resource flows. Effective logistics is vital for construction supply chains (CSCs), involving multiple disciplines with significant cost and management impacts [6]. Supply chain (SC) fragmentation, however, creates inefficiencies across processes, systems, and organisations, increasing overheads and raising sustainability concerns [7,8].

Construction logistics involves on-site activities and resource flow management to and from the site [9]. Its complexity arises from up to 90% of on-site work being procurement related [10,11], alongside fragmented SCs and bespoke procurement models [5]. Logistics encompasses warehousing and transportation as the ‘physical processes’, while the others are non-physical ‘business processes,’ with transport being the dominant component [12,13].

Construction materials may be classified using the ABC and XYZ methods. These are complementary inventory management tools that classify items by value and demand variability. ABC analysis categorises items based on annual investment: A-items represent about 20% of goods but 80% of total capital, requiring the most attention; B-items represent around 30% of goods, consuming 15% of capital; and C-items comprise roughly 50% of goods but only 5% of capital. This classification is visualised with a Pareto diagram using annual usage and unit price. XYZ analysis classifies items by demand variability: X-items have stable, predictable demand and allow accurate forecasting; Y-items show moderate fluctuations with medium forecast accuracy; and Z-items have highly irregular demand, making predictions difficult. Combined, ABC–XYZ classification guides inventory policy by dividing items into two groups: Group I—AX, AY, AZ, BZ, and CZ items, which are high-value or variable-demand and should be purchased based on stock data, and Group II—BX, BY, CX, and CY items, which are lower-value or more stable, require regular monitoring [14,15,16].

Most construction materials fall within Group II, typically low-value/high-volume, generating significant transport requirement even for small projects [17,18], contributing to noise, pollution, congestion, and broader environmental and health impacts [19,20]. SC inefficiencies, poor coordination, and inadequate on-site logistics lead to resource waste and increased inputs to sustain performance. A lack of integrated SC–site management further exacerbates these issues [21].

With transport emissions projected to increase by nearly 60% by 2050 [22,23], optimisation for improving construction workflow reliability suggests significant sustainability benefits [5]. Transport is essential to all businesses, with asset ownership and management usually externalised [24]. Strategic and operational measures serve as effective optimisation tools [25]. However, a general dearth of operational data limits evidence-based decision-making. Available data is typically trip-focussed rather than providing an SC perspective [26]. In New Zealand (NZ), almost 93% of freight moves by road, with over 30% construction-related [27]. Despite an average NZ truck capacity of about 22.5 tonnes, payloads average only about 9.64 tonnes [28,29], underscoring the need for optimisation to enhance efficiency and, therefore, construction transport sustainability.

The research problem investigates the role of logistics planning in optimising transport at the operational level. It aims to generate evidence-based insights that inform long-term business strategies to enhance the sustainability of the construction value chain through more efficient transport operations. The study addresses a critical gap by examining how transport efficiency shapes business model design to support sustainable practices across the value chain for manufactured construction products. Key focus areas include the vertical integration of distribution with manufacturing, coordinated planning, and the incorporation of integrated reverse logistics. Strengthening the value chain requires embedding these elements into long-term strategies that directly address managerial challenges associated with distribution and transport, ensuring operational efficiency contributes to overall sustainability objectives. The study examines the impacts of shifting from intermediary-based distribution to direct manufacturer-to-site delivery of construction products typically supplied through intermediaries or retailers. The analysis assesses how this shift influences transport performance and provides the basis for inferring and adopting long-term sustainable strategies. Specifically, the following research questions are investigated:

- How does a change in the adopted distribution strategy impact the efficiency of transport?

- How can distribution transport be further optimised?

- To what extent can the imbalanced transport equilibrium be mitigated and how will it impact transport efficiency?

- What sustainable business strategies may be inferred from the analyses?

Methodologically, the study adopts a case-based research design to examine how a shift in distribution strategy for a manufactured construction product can optimise construction-related freight logistics. SC analytics are used to streamline workflows, eliminate redundancies, and support data-informed decision-making aimed at improving delivery performance and sectoral decarbonisation [30]. The approach integrates spatial analysis with transport modelling to formulate a robust analytical framework to derive actionable insights for enhancing SC sustainability. Using real-world operational transport data, the study identifies evidence-based strategies for improving fleet management, collaborative planning, service procurement, waste management, and warehousing to address critical operational challenges.

This study contributes to CSC and logistics management knowledge by demonstrating that optimisation techniques commonly applied in manufacturing and freight can be effectively transferred to fragmented and temporary CSCs operating under uncertainty. It develops a transport-driven integrated model that links distribution, transportation, and warehousing, while providing empirical evidence of efficiency gains in the distribution of a manufactured construction product. The findings offer clear indicators for long-term strategic decision-making to improve operational sustainability across firms and the wider construction value chain.

2. Theoretical Background and Literature Review

The operational focus of CSCs emerges from the sector’s complex, project-based structure, which underpins systemic inefficiencies and externalities [31,32]. Logistics functions as a core element of production planning and project execution, influencing costs, schedules, and delivery performance [31,33]. Complexity arises from temporal, spatial, and organisational fragmentation, differentiating construction from other commonly known urban SCs [34] (excluding specialist SCs such as cold chains, etc.). The need for time-critical resource deliveries on fixed yet temporary urban construction sites creates inherent logistical dependencies [35,36]. Construction logistics operates at two levels: on-site activities and external resource flows [37]. The fragmented SC and bespoke procurement necessitate integrated on- and off-site management with clearly defined responsibilities [21,38]. Planning plays a central role in operational alignment by extending coordination and decision-making beyond the focal organisation [39,40,41].

Despite its centrality, logistics planning remains underdeveloped in construction [42], especially in the context of materials delivery and transport management [32,43]. The recent growth of interest in construction logistics—distinct from freight logistics—stems from its wider scope, complex stakeholder network, managerial challenges, and sustainability implications [10,44,45,46,47,48,49,50]. This literature review establishes the relationship between construction logistics, delivery of manufactured construction products to site, and transport performance metrics to contextualise construction as a logistics function in the construction sector. In scope are materials/products typically supplied through Builders’ Merchants (BMs), leaving out prefabricated and off-site construction elements.

2.1. Construction Logistics

The construction industry is highly complex, as project delivery involves multiple phases, specialised services, and multiple stakeholders and actors [51]. This complexity is compounded by the traditionally fragmented organisation of construction demand and supply systems, which leads to disjointed production processes [52]. The CSC therefore evolves continuously with shifting stakeholders and actors, processes, and resource requirements across the project lifecycle [53].

Logistics, in the context of the construction phase of a project, involves the coordinated movement of materials from suppliers to construction sites and the management of waste removal [6,54]. Suppliers may be manufacturers of specific products, importers, or intermediaries/retailers, depending upon the scale and context of the project [55]. Forward logistics manages resource flows from suppliers to project application, while reverse logistics focuses on site waste removal and disposal [6]. Alignment of multiple stakeholders across planning, transportation, and on-site operations is essential [56,57,58].

Warehousing and transport are the core elements of construction logistics, with transport being the dominant component, as most other logistics activities involve business processes rather than physical ones [50,59]. Manufacturer warehousing addresses temporal, spatial, quantitative, and qualitative mismatches between material supply and demand across production, sales, and consumption [60]. Intermediate, retailer-operated warehouses buffer economic and logistical variations [61,62].

Transport, on the other hand, links multiple actors and channels within the logistics system [56,58,63,64], ensuring timely and diverse flows of materials and services to and from sites [35,65]. It is the most resource-intensive and critical element of construction logistics [13,66]. Unlike conventional freight systems, construction transport is shaped by fragmented and evolving SCs [5,67], project-centric delivery needs [10,34,68], and the industry’s responsibility for its own logistics, in contrast to urban logistics managed by city authorities [4,8,49,69]. It is also influenced by the high-volume, and relatively low-value, characteristic of materials that creates substantial transport requirements even for relatively small construction projects [18,70]. The related vehicle movements add to the existing traffic flows in urban areas, disrupting production–delivery synchronisation from externalities like congestion [35,65]. Poorly timed deliveries further exacerbate risks due to on-site spatial constraints [4], while loading/unloading delays disrupt both on- and off-site productivity [71,72].

Traditionally, logistics in construction has been approached as an operational function from the contractor’s perspective in research and practice [73,74]. Effective implementation hinges on the optimisation of loading zones, storage allocation, material handling, and transport scheduling to minimise delays and disruptions. The forward and reverse logistics streams operate as separate but interrelated business functions [63], with supplier–transporter interactions being site- and delivery-specific [57,58]. The focus on supplier coordination and just-in-time deliveries compensates for limited on-site storage [56]. While this addresses both trade-specific and phase-specific fragmentation, it overlooks inefficiencies that occur across multiple projects [75]. Combined with externalised ownership and management of transport assets [13,24,76], the contractor-centricity of construction logistics restricts flow of information and coordination, reducing delivery efficiency [44,77].

2.2. Manufactured Construction Products Distribution

The distribution chain for manufactured construction products operates as a three-echelon network of bulk suppliers, intermediaries (e.g., BMs and retailers), and construction sites. These tiers are linked by external transport providers [62,78,79], creating a loosely coupled system organised around individual deliveries [80]. Within this framework, three main distribution methods are employed. Firstly, Direct-to-Site (DTS), where bulk consignments such as steel framing are delivered directly to sites, bypassing intermediaries. Secondly, Freight-into-Store (FIS), the dominant method, in which bulk suppliers route products through intermediaries to compensate for limited retail distribution capacity. Finally supply via specialist stockists, where manufacturers distribute products through their own subsidiaries [55,62,79].

Vertical integration refers to the degree of control an organisation exercises over the production of its inputs and the distribution of its outputs. While various definitions exist, it is consistently understood as the internalisation of activities otherwise undertaken by external actors to reduce transaction costs and strengthen market power [81,82]. Integration can take place upstream with suppliers or downstream within distribution networks for both materials and services [83]. In construction distribution, DTS delivery and supply via specialist stockists illustrate downstream vertical integration, as manufacturers assume greater control over distribution functions [84,85].

FIS distribution is structured around three nodes: the manufacturer’s storage, the intermediary’s warehouse, and the construction site. Material and information flows are managed through two key links, manufacturer–intermediary and intermediary–construction site. The intermediary plays a central role by receiving bulk inflows from the manufacturer and managing both bulk and retail outflows to end users [55]. This configuration reflects the ‘distributor storage with carrier delivery’ logistics model [86]. Uncertainty aggregation at the intermediary increases SC inventory levels compared to manufacturer-level aggregation, which pools uncertainty across all retailers, resulting in lower SC inventories. Beyond this, intermediaries fulfil critical economic and logistical functions by extending credit to contractors and developers and maintaining safety stocks to absorb market fluctuations [54,62,79,87,88]. The warehousing function is distributed across all echelons: bulk suppliers hold bulk inventories, intermediaries retain buffer stocks for retail distribution, and construction sites store materials for immediate use [89].

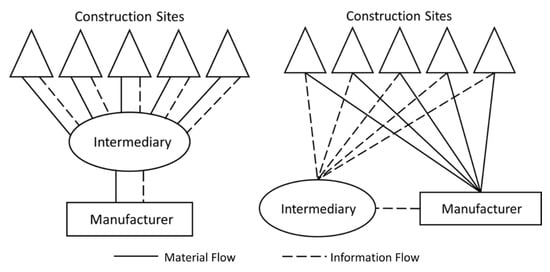

The DTS model, on the other hand, vertically integrates manufacturing and distribution while outsourcing transportation to a Second Party Logistics (2PL) provider [90,91]. Compared to the FIS model, it introduces an additional link: two links function as information channels between the construction site, intermediary, and manufacturer for aggregating site requirements and invoicing, while material flows directly from the manufacturer to the construction site through a third direct link between the manufacturer and the construction site(s). This configuration reflects the ‘manufacturer storage with direct shipping’ strategy, which centralises inventory at the manufacturer, thereby lowering overall SC inventory levels compared to the FIS model, while sustaining high product availability [86]. Figure 1 illustrates the two distribution models.

Figure 1.

Supply networks for FIS (left) and DTS (right) distribution.

Suppliers operate at national, regional, and local levels, with local depots/warehouses serving as customer-facing entities for specific areas. The transport function of these local depots is derived from the need for delivery to customers and employs a small fleet of vehicles. While national and regional distribution employs transport professionals, local depots prioritise customer service over transport efficiency, with non-specialist depot managers controlling transport. Orders typically follow a 24 h cycle for next-day delivery [55]. Distribution relies on local area knowledge rather than transport competencies [90,92]. Transport inefficiencies are hidden within material costs, masked by straightforward ‘as-delivered’ pricing [6,18,93].

2.3. Transport Efficiency and Performance

Operational efficiency of a process is evaluated through two core metrics: utilisation and productivity. Utilisation is the ratio of actual to maximum potential output for a given capital stock [94], indicating how effectively resources such as equipment, vehicles, or labour are employed. High utilisation signals efficient use, while low utilisation reflects idle or underused capacity [95]. Productivity, on the other hand, measures the output generated per unit of input—labour, energy, equipment, or similar resources [96]—and represents the ‘transformational efficiency’ of converting inputs into activities. Although distinct, the two metrics are closely linked, and their joint application in strategic and operational planning is vital for performance optimisation [95,96,97]. Despite sectoral nuances, both converge on maximising output from available inputs [98].

At the operational level, goods handling efficiency is fundamentally determined by vehicle utilisation, specifically through the concept of ‘filling rate’—the ratio between actual cargo weight and maximum payload capacity. This metric depends on whether vehicles reach volumetric limits (cubing out) or weight restrictions (weighing out) first during loading [99,100,101]. Two key elements underpin this definition: spatial attributes of truck movement (such as route distance and origin-destination pairs) and physical attributes of a shipment (such as weight and volume) [102]. From this framework, five principal utilisation measures are derived: Weight-based loading, Volumetric loading, Tonne-km (tkm) loading, Deck-area coverage, and Level of empty running [99,101] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Metrics of truck capacity utilisation [99,101].

Vehicle efficiency is assessed over the entire round trip rather than solely the outbound journey. In construction, securing backhauls for return trips is a persistent challenge [103]. Hence, construction transport invariably operates in an imbalanced equilibrium, with different quantities moving in each direction [104]. This is exacerbated by the delineation of material supply and waste removal businesses [105]. Recognising empty running as a sustainability issue rather than just a resource waste has redirected both policy and business metrics toward minimising it, positioning backhaul optimisation as a central strategy for improving distribution sustainability [90,106].

Transport efficiency can be improved through strategic and operational tools [25]. However, evidence-based decision-making is constrained by the lack of comprehensive operational data [107]. Commonly available data is trip-centric rather than SC focussed [26,108]. The literature also points to a general lack of research pertaining to adapting logistics/transportation models for transforming the overall value chain [109]. In the background, reduction of externalities continues to be a constant effort in the shift towards improved sustainability [110].

3. Materials and Methods

This Section outlines the methodology for data acquisition, validation, analysis, and optimisation used to ensure the robustness and reliability of the study. Transport logs were selected as the primary data source because they provide continuous, detailed, and operationally grounded information on vehicle movements, load characteristics, and delivery patterns, thereby enhancing representativeness and reducing bias associated with aggregated or self-reported data. The dataset underwent a two-stage validation process: using Quantile-Quantile (Q-Q) plots to confirm no undue influence by any variables that impact transportation and using Cronbach’s Alpha to validate the consistency of dispatch planning.

Given the size of the dataset and the need to populate missing efficiency-related variables, random sampling was adopted to maintain representativeness while ensuring computational feasibility. Transport efficiency metrics aligned with the characteristics of plasterboard delivery were then selected from established standards and applied to the sample. Finally, optimisation methods appropriate to the dataset, and the nature of the transport task were used to optimise the existing transport solution. Each methodological step was evaluated in terms of its effect on transport efficiency, enabling a systematic assessment of how data refinement, metric selection, and optimisation contributed to improved operational performance.

3.1. Data Acquisition and Validation

The analysis is based on three months of transport data pertaining to DTS plasterboard distribution in Auckland, capturing approximately 55 days of operations. The dataset included truck details (IDs, model, payload, Gross Vehicle Mass—GVM) and consignment information (quantities, loads, invoicing). It consisted of the details of approximately 2300 trips, each with multiple drops. The distances between various destinations and the sequence of servicing drops, essential for analysing transport efficiency were not available and needed to be obtained and inserted into the dataset. However, undertaking the exercise for 2300 trips was considered time consuming and tardy, with a high possibility of transcription errors, since the dataset consisted of nearly 80,000 datapoints considering the variety of plasterboard sheets being delivered.

Hence, simple random sampling—giving each population member an equal probability of selection—was used to obtain a small, representative subset of the dataset, enabling reliable population-level conclusions while saving time, reducing resource use, and minimising the possibility of errors. Truck trips were sorted in increasing order of their despatch date/time stamp and provided the serial number as the trip identifier. A total of 370 true random numbers were then generated using an online random number generator (https://www.random.org/). Truck trips with identifiers corresponding to these random numbers were selected as the sample, providing a true representation of the population of 2300 trips [111]. This data sample was then populated with information related to distances obtained from Google Maps version 11, and the sequence of drop servicing obtained from the ‘Eroad’ (2022) database (an IT based GPS services provider in NZ).

Prior to sampling, the normality of transport operations was validated, considering underlying variables such as delivery day and time, quantity, service area, and truck availability, capacity, and allocation [100,112]. Although these variables are influenced by both causal relationships and intentional planning, they are treated as random in the analysis to capture the variability and uncertainty inherent in real-world operations [113]. Normally distributed loading efficiencies were taken as an indicator of the despatch planning process being free from significant variance [114] due to the excessive influence of one or more underlying variables. This subsumes individual variances into the overall despatch planning process, which now represents the construct of interest for analysis. Loading efficiencies were determined using consignment weight and truck payload capacity from the complete dataset and these were then compared to a normal curve using SPSS version 29.

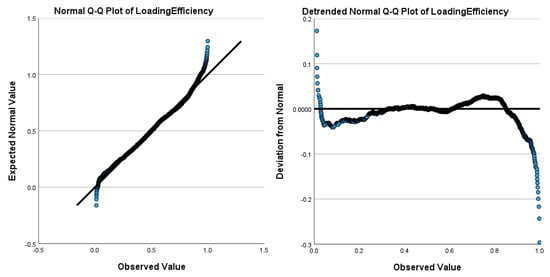

Q-Q plots are a powerful non-parametric technique to assess the goodness of fit of any dataset to a standard dataset representing a given statistical distribution. The co-efficient of determination (R2) is an indicator of how closely the given dataset replicates the selected distribution [115]. R2 is considered a more powerful error detection index compared to typically used statistical quantities like SMAPE, MAPE, MAE, MSE, and RMSE [116]. In the instant case, Q-Q plots were used as a tool for assessing the goodness of fit of the loading efficiency dataset with a normally distributed dataset. Figure 2 presents the Q-Q plots of truck loading efficiencies from the complete dataset using SPSS. R2 was found to be 0.9882, indicating good fit, implying that the loading and transportation processes were free from unduly excessive influence of any underlying variable.

Figure 2.

Normal Q–Q plots for truck loading efficiency. (The blue circles are individual plot of points by SPSS, when they come closer, they form a continuous thick line).

Despatch planning emerged as the sole independent variable (subsuming all others) affecting transport operations. However, measuring the consistency of the dataset was considered necessary as an ‘acceptance’ test before presenting it to an optimisation algorithm, as consistency of inputs is essential to ensure that optimised outputs reflect systematic operational patterns rather than random variation. Cronbach’s Alpha (with values ranging from 0 to 1) [117] is a statistic that provides a measure of whether multiple discrete or continuous observations [118,119] reliably capture a single underlying construct [117,120]. In this study, it was applied to assess the internal consistency of despatch planning, identified as the construct of interest. The complete dataset was organised as a matrix of daily allocation patterns, with columns representing days and rows representing individual truck loads. A tiered framework for interpreting Alpha values is well established, with ≥0.9 indicating excellent reliability and ≤0.5 considered unacceptable [117,121]. Cronbach’s Alpha value of 0.51230 obtained using MS Excel is positioned at the lower bound of acceptability, reflecting the operationally-driven stochasticity in truck allocation—driven by differences in vehicle capacities, route demands, and the non-Likert nature of loading efficiency data [120,122]—differentiating it from random noise [123,124,125].

3.2. Analysis

The analysis compared business-as-usual (BAU) and re-engineered plasterboard distribution strategies by assessing transport efficiency using key performance metrics. Operations Research and circular-economy principles further identified systemic improvements, followed by stakeholder collaboration, and integrated reverse logistics as enablers of enhanced operational sustainability through transport optimisation.

3.2.1. Transport Efficiency Metrics

Plasterboard is a cost-effective, durable interior material valued for fire resistance, soundproofing, and ease of transport, commonly used in residential and commercial construction. Its customisable properties meet varied structural and acoustic needs [126]. In NZ, plasterboard supply is highly concentrated, with one supplier holding almost 95% market share. Most sales take place via intermediaries [55]. In FIS distribution, material flows replicate intermediaries’ invoicing patterns in terms of the actors through whom they are routed, and the (geographical) areas where the intermediary operates. DTS distribution, however, delinks the invoicing pattern from the SC echelons handling inventories, at the same time dissociating delivery areas from intermediaries’ physical location.

This study selected weight-based metrics for analysing transport performance due to the characteristics of plasterboard (density—700–900 kg/m3) [127] and its transportation using flat-bed trucks that typically weigh out before cubing out. The two performance indicators examined were: (i) weight-based loading, which calculates static efficiency by comparing actual load to maximum payload capacity at trip commencement (‘loading efficiency’); and (ii) tkm based loading, which assesses dynamic capacity utilisation by multiplying segment-specific loads by their respective distances and comparing this to the theoretical maximum on a round-trip basis (‘capacity utilisation’).

3.2.2. Comparison of FIS and DTS Distribution

Quantifying distribution/SC design-based transport efficiency is a data-driven exercise [128]. A disaggregation of the complete dataset (DTS distribution) revealed important distribution parameters: An average of 42 daily trips by 26 flat-bed trucks with varying payload capacities; approximately 330 tonnes of plasterboard distributed daily; nearly 75% trips had a single drop; trips involving more than three drops were found to be statistically insignificant, hence ignored in the analysis; The transport function was outsourced to a transport contractor on a 2PL basis; and a ‘per-tonne’ pricing model regardless of distance adopted for transport procurement [90].

In DTS distribution, the three nodes (Manufacturer–Intermediary–Site) form a triangular structure. Direct delivery is usually shorter than routing through intermediaries, except in the rare case where the nodes are collinear, which is uncommon in urban contexts. Using the data sample for comparing FIS and DTS distribution revealed approximately 30% reduction in travel distance, with average trip lengths of approximately 38 km for FIS and about 27 km for DTS. As nearly 75% of trips involved a single drop, Intermediary–Construction Site and Intermediary–Manufacturer distances served as reliable indicators.

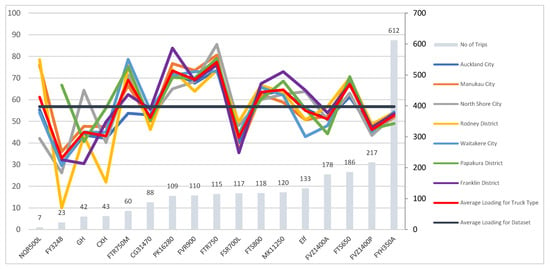

Figure 3 presents the loading efficiencies observed in DTS distribution during the data acquisition period. The plot is disaggregated by truck model and distribution zone and aggregated as an average of the individual trip loading efficiencies of specific models from the complete dataset. It highlights that efficiencies cluster consistently according to vehicle type across all delivery locations. Trucks with lower payloads, limited trip frequencies, and smaller fleet representation exhibit markedly poor loading performance. In addition, HIAB (crane-equipped) trucks, quite unexpectedly, demonstrate low loading efficiency, despite their high payload capacity.

Figure 3.

Truck trips and loading efficiencies achieved. (Note: X-axis—Truck models; Y-axis (left)—Loading efficiency (%); Y-axis (right)—Number of trips.).

In comparison, the shift from FIS to DTS distribution improved the capacity utilisation from approximately 19.33–27.61%. Despite this improvement, DTS achieved only 56.36% loading efficiency (tonnes), leaving about 252 tonnes of available truck payload capacity underutilised daily. These findings highlight the scope for reducing truck trips while maintaining delivery volumes, i.e., optimising the transportation function.

3.2.3. Potential for Further Enhancement of DTS Transport Efficiency

Logistics, as a multidisciplinary field, draws on strategies and methods from a wide range of domains [129]. The challenge of optimising transport while maintaining delivery outputs aligns with broader allocation problems. Accordingly, Operations Research was examined for suitable optimisation tools, with the Linear Programming (LP)-based Transportation Model identified as a potential solution through literature review [130,131,132,133].

The transportation model is used to determine the most efficient way to move goods from multiple supply points to multiple demand points. The problem matrix is formulated with each of the sources forming the rows and each destination forming a column. Objective coefficients specify the cost, time, or environmental impact associated with transporting one unit on each route. Decision variables represent the quantity shipped along each origin–destination route. Constraints ensure that shipments from each supply point do not exceed available supply and that total deliveries to each demand point meet required demand, maintaining feasibility across all routes. Other constraints such as delivery time windows, multi-drop trips, and route-specificity can also be applied [134]. These combine in the objective function, which typically seeks to minimise total transport cost while satisfying supply and demand constraints. The model provides an optimal allocation of flows that meets all requirements at the lowest possible system-wide cost [131,134,135].

The Transportation Model is a well-established optimisation tool in manufacturing and transport logistics [136]. In construction, however, its application is predominantly limited to generic CSC analyses and, within product distribution, to off-site construction [137]. The problem considered in this paper further departs from the classical formulation, since the manufacturer’s warehouse serves as the sole supply node, and the value proposition of cost minimisation [131] is rendered irrelevant by the decoupling of transport costs and distance through a ‘per-tonne’ transport pricing model [90].

The problem was reformulated around one day’s operations at a time by designating each truck departing from the manufacturer’s warehouse as an independent supply node. Truck payload capacity was modelled as a ‘less than or equal to’ LP constraint, representing the maximum weight of plasterboard a vehicle could transport per trip, forming the rows of the problem matrix. Consignment loads were treated as ‘equal to’ LP constraints, representing fixed demand at each destination node, comprising the columns of the problem matrix. Each cell of this matrix was then populated with per-tonne transportation costs. Given the uniformity of channel (arc) costs, the reformulation shifted the objective from cost minimisation to transport minimisation.

The problem was solved using the MS Excel Solver add-in. It provides an accessible and reliable platform for solving Transportation Problems. Using the Simplex LP algorithm, it efficiently minimises transportation costs under supply (truck capacity) and demand (site requirement) constraints. Excel’s transparency supports easy validation and adjustment of model parameters, making it well-suited to applied logistics and operational research [138]. Solver was used for ‘proof-of-concept’ solutions, with data truncated to fit its 200-cell limit while preserving trip integrity. The solution matrix allocated a single truck’s capacity to service multiple consumption points based on the defined constraints.

The solution provided by Solver reduced truck trips from 42 to 26, with a corresponding increase in loading efficiency from ~56.36% to ~92.89% and capacity utilisation from ~27.61% to ~49.38%.

The application of LP for transport optimisation underscores the importance of coordinated planning between the plasterboard manufacturer and the transport supplier. Under the BAU scenario, transport operations were executed according to the manufacturer’s requirements; however, the prevailing ‘per-tonne’ pricing model discouraged systematic evaluation of resources such as truck numbers, delivery drops, and travel distances. As a result, both parties pursued their own objectives independently—the manufacturer ensuring delivery of required plasterboard volumes and the transporter focusing on profitability—while resource planning was relegated to the daily operations planner.

3.2.4. Integrating Reverse Logistics of Waste Removal with Material Delivery

A truck with a single drop can achieve at most 50% capacity utilisation if fully loaded at the start. This tends to decrease with multiple drops [139]. Deliveries along the route reduce loads, creating capacity for backloads. This offers an opportunity to integrate plasterboard waste backhaul with material delivery, using the same trucks for both functions. Collecting waste on return trips can increase loading efficiency at interim drop points, improving truck capacity utilisation along the next trip segment by gainfully using tkm otherwise going waste. The high variability of truck loading, trip lengths, drop points, loading efficiency, and capacity utilisation achieved in DTS distribution (Table 2) necessitated the development of a generalised trip model within which the average backhaul figures could then be incorporated for estimating improved capacity utilisation.

Table 2.

Variability in transport efficiency related parameters.

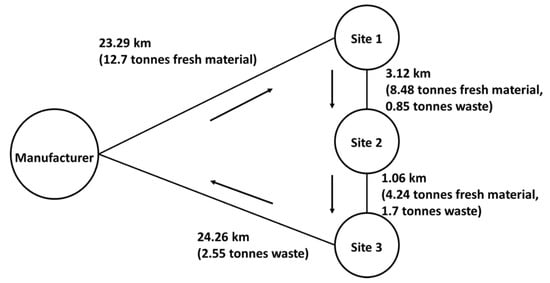

The amount of plasterboard waste available for backhaul is a function of on-site waste generation. Based on NZ-centric studies by Jaques (1999) [140], Nelson et al. (2022) [141], and McMeel et al. (2024) [142], approximately 20% of on-site plasterboard waste generation is considered a reasonable estimate for local conditions. The complete dataset revealed that each construction site requires an average of about 12.7 tonnes of plasterboard, delivered over three trips (nearly 4.24 tonnes per trip). With 20% waste generation, each site tends to produce about 850 kg of waste per delivery trip.

The generalised trip model was developed by averaging loads, drop points, and distances from the complete dataset, as well as the data sample, further superimposed with average on-site waste generation figures. Figure 4 illustrates the generalised trip model representing an elemental distribution task, scalable for specific operational durations, such as 26 trips for daily operations. This enables analysis of how incorporating waste backhauls into delivery operations affects truck capacity utilisation.

Figure 4.

Generalised trip model for DTS distribution and waste removal.

From the generalised trip model, integration of reverse logistics (waste plasterboard backhaul) with the LP-enhanced DTS model improves truck capacity utilisation from 49.38% to 58.79%.

4. Inferences and Sustainable Business Strategies

4.1. Fleet Management

Loading efficiency of trucks is found to be bunched by truck model rather than the distribution area or location (Figure 3). Trucks with lower payloads, limited trip frequencies, and smaller fleet representation consistently demonstrate poor loading efficiency. This outcome is largely attributed to routing practices that prioritise short, fragmented deliveries over consolidated loads. The resulting increase in partial loading of trucks undermines overall efficiency. Such practices are common in the construction sector, where just-in-time deliveries are often prioritised to match site progress but inadvertently create inefficiencies in fleet operations [143]. Similarly, HIAB (crane-equipped) trucks, despite their higher load capacity, exhibit low loading efficiency. This is due to their dual function as delivery vehicles and on-site material handling equipment. The majority of their operational time is spent unloading and positioning plasterboard, since all trucks in the fleet are not crane-equipped [90]. These findings suggest that vehicle type, rather than geography or delivery location, is the principal determinant of loading efficiency in CSCs.

The preceding inferences have significant implications for fleet management. Fleet standardisation needs to prioritise truck models that consistently demonstrate high loading efficiencies, aligning GVM with a generalised payload of approximately 12.7 tonnes. Standardisation is expected to improve planning consistency and reduce inefficiencies associated with under- or over-capacity vehicles [143]. A strategically planned fleet rejuvenation is also warranted, beginning with the phased removal of smaller trucks with low payload capacities, followed by vehicles exhibiting irregular loading patterns or those representing only a minor proportion of the fleet. This approach enhances load consolidation and operational consistency, mitigating inefficiencies inherent in fragmented delivery networks [144].

Equipping all vehicles with crane systems would further increase operational flexibility, enabling trucks to perform both transport and on-site material handling (including loading bags of plasterboard waste, as discussed in Section 4.5), thereby removing bottlenecks associated with specialised HIAB vehicles [145]. Finally, transitioning to cleaner vehicle technologies should constitute a core component of long-term fleet strategy. Incorporating low- or zero-emission trucks not only supports regulatory compliance and environmental objectives but also ensures resilience against evolving market demands [146].

4.2. Non-Price Attributes in Tendering and Contracting

In the BAU scenario, truck loading efficiency is approximately 56%, which results in overall capacity utilisation of about 28%. Under the prevailing ‘per-tonne’ pricing model, both the plasterboard manufacturer and the transport contractor achieve their immediate objectives: the manufacturer achieves deliveries of requisite plasterboard tonnages corresponding to demand, and the transport contractor earns expected financial returns. While this alignment of short-term goals ensures operational continuity, it reduces the incentive to optimise transport efficiency or consider broader sustainability objectives. Even in contexts where transportation is vertically integrated with manufacturing (as in the instant case), practices such as load consolidation, minimisation of empty trips, and efficient routing are rarely prioritised, limiting potential environmental and operational benefits.

To promote more sustainable outcomes, transport procurers can integrate Non-price Attributes (NPAs) [147,148,149] into tendering and contract evaluation. NPAs may require bidders to demonstrate strategies that improve truck capacity utilisation, implement low-emission or hybrid vehicles, or adopt digital fleet management technologies to optimise route planning and scheduling. Tender evaluation frameworks need to carefully balance sustainability metrics with financial factors, ensuring that neither aspect dominates decision-making [150]. Additionally, transport operations need to be continuously monitored against Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) established at contract award, such as average truck payload, trip efficiency, fuel consumption per tonne-kilometre, or percentage of fully loaded trips.

Benchmarking performance against KPIs enables the identification of inefficiencies and supports iterative improvements over time. By embedding such monitoring and incentivisation mechanisms, SC stakeholders can cultivate a culture of continuous performance enhancement, leading to measurable gains in operational efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and environmental sustainability. Incorporating NPAs and KPI-driven monitoring provides a structured pathway for aligning commercial objectives with broader sustainability goals.

4.3. Transport Pricing

The analysis presented is based on the ‘per-tonne’ transport pricing model adopted in the SC being examined. While the distance-based ‘per-km’ model remains the conventional approach in the freight sector, other pricing models, such as ‘per-truck’, are also widely used [151]. From a sustainability perspective, the per-tonne model primarily focuses on quantities delivered, largely disregarding the distances travelled and the associated vehicle utilisation. In contrast, the per-km model inherently incorporates operational efficiency alongside delivery performance [152], providing a more holistic and environmentally conscious measure of transport sustainability. Selecting the most appropriate pricing model is, therefore, essential for contract award and performance monitoring, as it directly influences incentives for efficient resource utilisation.

Transport utilisation, in this context, is analysed using two key parameters: daily average vehicle-km, and aggregated tonnages delivered. The generalised trip model indicates that over 26 trips of approximately 52 km each: 1352 vehicle-km and 330 tonnes of plasterboard are delivered. To reconcile per-km and per-tonne costs, the value of one parameter can be fixed, and the corresponding value of the other parameter can be calculated. E.g., an arbitrary cost of NZ$1/km corresponds to NZ$4.09 (NZ$1 × 1352/330) per-tonne. A transport pricing solution can be derived by plotting the ratio of these parameters on a simple graph. Values below the fixed intercepts on both the axes indicate improvement in operational efficiency.

Updating the slope of the plot using periodic data on vehicle-km and tonnage facilitates continuous improvement during the contract period, such as targeting a 5% reduction in vehicle-km for the same delivery tonnages or a 5% increase in tonnages delivered without additional vehicle-km. By integrating these metrics, transport operators and procurers can quantify efficiency gains, optimise fleet performance, and systematically enhance sustainability outcomes [153].

4.4. Integrated Planning

An effective business plan includes business design, process management, accountability, and performance monitoring through data analytics, technology, and role specialisation as its key elements [154]. These elements need to drive performance in plasterboard distribution. The current fragmented planning process, where the transport procurer remains excluded from the distribution planning despite being a key stakeholder, leads to inefficiencies.

To address this gap, integrated transport planning needs to be embedded within the manufacturer’s broader sustainability strategy so that the design of distribution operations is aligned with long-term sustainability goals. A sustainability statement, in this context, could include measures for operational planning, technology adoption, and accountability mechanisms that ensure continuous improvement. E.g., the use of computer-based tools for truck loading and routing can enhance scheduling accuracy and resource utilisation. Similarly, the integration of sustainable transport technology within fleet management practices—such as phasing out poorly performing vehicles and inducting low-emission alternatives—forms an important step in reducing the environmental footprint of distribution operations [155,156].

Performance measurement through KPIs such as capacity utilisation and fuel efficiency can further enable effective monitoring of transport operations while linking efficiency improvements to broader sustainability goals. E.g., tracking backloading and waste accumulation at the manufacturer’s facility can improve raw material circularity, while reduction in embodied resources (e.g., carbon) support measurable sustainability outcomes [155]. Accountability mechanisms require logistics managers and service providers to achieve pre-defined benchmarks, supported by data acquisition systems such as IoT monitoring of truck movements, real-time fuel efficiency recording, and systematic waste data collection [157]. In addition, collaborative initiatives with customers—such as improved packaging, pre-cut plasterboard sheets to reduce on-site waste, and off-cut collection systems—further align manufacturing and distribution efficiency with Circular Economy objectives [158] by encouraging recycling/reuse.

4.5. Management of Waste

Plasterboard is typically delivered on flat-bed trucks with pallets securely strapped, whereas waste plasterboard, due to its irregular shape and lack of defined structure [159], requires customised loading solutions to avoid interfering with fresh material. A pragmatic approach involves bagging the waste and craning these bags onto or between the fresh plasterboard. Recycled plasterboard waste can be incorporated into new production at rates of up to 10%, depending on material quality and the load-bearing properties of the finished product, a finding supported by Erbs et al. (2021) [160] and McMeel et al. (2024) [142]. This option underscores the need for trucks to be equipped with cranes (Section 4.1), thereby influencing fleet composition and capital investment decisions. Economically, reduced truck capacity and reduced fleet size (as a result of reduced trips) can offset the investment required for equipping trucks with cranes.

Auckland, which accounts for 40–45% of NZ’s national sales, presents a strategic opportunity for plasterboard recycling, given its large market scale and logistical concentration. By contrast, backloading operations in other regions such as Hamilton, Wellington, and Christchurch have not yet achieved economic viability [90]. This regional disparity highlights the importance of targeted strategies for resource recovery where economies of scale exist. Addressing these challenges requires the development of innovative operational and business models that engage a wide range of stakeholders, including manufacturers, developers, contractors, and waste managers. Reconfiguring reverse logistics chains and improving waste collection and transport efficiency are central to this effort, alongside the optimisation of disposal and recycling sites. Emerging strategies may include the introduction of financial incentives for contractors to provide clean and uncontaminated waste streams, supported by digital tools such as mobile applications for requisitioning transport and coordinating collections. Feeding plasterboard waste back into the manufacturing process rather than sending it to landfill or diverting it into secondary SCs (such as gypsum required for fertilisers) and eliminating additional transport for its return are also likely to provide economic impetus for fleet investment decisions.

Technologies like RFID-based contractor identification can further streamline waste tracking, while establishing consolidation points through process re-engineering can improve efficiency and cost-effectiveness in waste handling. Such measures align with broader Circular Economy principles, which emphasise waste minimisation and material recovery as pathways to sustainability in construction [161]. Moreover, research suggests that integrating digitalisation and stakeholder collaboration into reverse logistics models significantly enhances recycling outcomes and system resilience [162,163]. Together, these approaches can transform plasterboard distribution and waste management into a more resource-efficient and sustainable process.

4.6. Integrated Warehousing

Urban sprawl disrupts construction logistics by decentralising construction activity and extending transport distances, undermining the efficiency of hub-and-spoke models [164]. Since the mid-1800s, Auckland has developed as a polycentric city-region with linear growth along transport corridors and coastlines [165,166]. Continued outward expansion disperses development from the urban core [165,167], intensifying freight movements between established freight-generating areas and emerging freight-attracting zones. This increases trip frequency, fragments deliveries, lowers load factors, and ultimately increases per-unit emissions [107,108,168].

These dynamics reduce truck capacity utilisation (tkm), particularly as longer round trips exacerbate inefficiencies. A hybrid distribution model offers a potential solution by dividing deliveries into two stages: bulk transport to intermediary facilities at near-full truck capacity, followed by local DTS distribution. This approach shifts a larger share of the journey onto high-efficiency bulk transport, limiting the relatively less efficient DTS segment to the final leg [169], thereby reducing the carbon footprint. A graphical representation of the ‘integrated warehousing’ model is in Figure 5. The effectiveness of this model, however, depends on optimally locating intermediary or ‘forward’ warehouses to balance accessibility with efficiency. An implementation of the ‘pooled warehouse’ concept within collaborative logistics, this is an emerging area of research. Limited implementation has shown reduced costs and improved transport efficiencies [170,171].

Figure 5.

Impact of zonal warehouses under ‘integrated warehousing’ on transport efficiency.

In Auckland, the shift of nearly 75% of plasterboard deliveries from FIS to DTS [90] has reduced inventory at intermediary facilities, leaving them underutilised. This presents an opportunity to re-purpose freed-up space for holding forward stock on a shared-capacity basis between manufacturers and intermediaries. Such an arrangement introduces ‘floating stock’ into the SC, reducing storage costs and lead times while maintaining service levels [172]. Positioning inventory strategically requires selecting centroidal intermediary warehouses within consumption zones, based on material demand and site proximity [173]. This aligns with the ‘centre of gravity’ (CG) approach [128], which seeks to minimise overall transport activity [174]. In addition to a reduced carbon footprint, the inventory carrying costs [59] of the manufacturer are also likely to reduce along with the real estate requirements for storage.

This will potentially impact material costs, though marginally. However, given that the study pertains to approximately 95% of plasterboard production in NZ, the overall impact is likely to be substantial. Intermediary establishments and zonal warehouses can also effectively provide storage and consolidation facilities for waste plasterboard in the reverse logistics chain [175].

5. Managerial Insights

Based on the analysis, several key insights emerge for SC managers in NZ, particularly in the construction sector, where logistics play a decisive role in sustainability outcomes. NZ presents long travel distances for freight transport, of which construction transport is an integral part, owing to its linear geographical configuration [166]. This increases the cost of commodities transported, especially that of construction materials/products, which are high-volume/low-value in nature [18]. ‘As-delivered’ costs, however, do not disaggregate transportation costs from material costs [176], making transportation cost a ‘hidden’ component [6,177]. There is, therefore, a need to revise standard tendering practice in construction to include ‘factory gate pricing’ [178]. Historically, building contractors have never considered the need to develop logistics competencies to reduce both logistics costs and carbon emissions [68]. Employing a logistics coordinator—on a single or across multiple sites—can improve transport efficiency by providing the capability to ‘receive’ supplier planned consignments (as in this study) to support site logistics management through ‘on-site coordinated’ and ‘coordinated site and supply network’ configurations, as suggested in the literature [179].

Increasing pressure from governmental and progressive clients to deliver a more sustainable construction process [180] has the potential to substantially impact construction costs since transportation costs anywhere from 1020% of construction costs [181], and 410% of a building’s selling price [177].

The inclusion of NPAs in the selection of winning tenders is central in concept to the development of high-performance production processes [148]. Considering the example of tendering for transportation procurement, price-based selection requires minimal thought and evaluation. In contrast, more sustainable behaviours can be delivered by evaluating demonstrated performance in different metrics such as reducing transport emissions, minimising travel distances, maximising transport efficiency, and employing clean technology [147]. These evaluation metrics can improve environmental sustainability through the direct spin-off of reducing carbon embodiment [77]. The challenge lies in initially developing NPAs, then collaborating with the transport supplier to gradually enhance operational efficiency to align with these NPAs, and finally their translation into tendering criteria [90].

Employing ‘zonal’ warehousing as a strategy for undertaking bulk/retail deliveries from these locations instead of the manufacturer’s warehouse can cut down delivery times and transportation costs [169]. NZ’s elongated configuration and long distances between population centres imply that the logistics environment operates more like servicing an archipelago of island populations than a contiguous landmass [166,182]. The selection of centrally located warehouses can be optimised based on material uptake within the zone [90,108], utilising the closest existing facility [183] for consolidating ‘forward deployed’ material stocks [169]. As material uptake patterns, particularly for residential construction, keep changing, driven by urban development, subsequent analyses can shift these warehouses for optimal delivery efficiency.

Establishing a ‘Freight Uber’ concept [184] to provide ‘ridesharing’ for material delivery based on higher visibility of delivery operations [185] can enhance the efficiency and sustainability of construction logistics. This could be further extended to waste removal from construction sites [31,186], using the same transport that delivers fresh material, effectively integrating forward and reverse logistics—two functions traditionally managed separately [31,105,186]. A simple mobile application to indicate availability and readiness of plasterboard waste pick up, with visibility across the complete fleet, can effectively divert the nearest delivery truck to pick it up as a backhaul. Within this framework, zonal warehouses can provide consolidation facilities for both, fresh material in the forward distribution chain, as well as waste in the reverse logistics chain [187].

6. Discussion

The empirical findings of this study underscore the critical role of transport optimisation in enhancing sustainability within the construction sector, with broader implications for supply chain management and freight transport. By examining plasterboard distribution in Auckland, NZ, this research quantifies inefficiencies inherent in traditional FIS logistics models and demonstrates the tangible benefits of transitioning to a vertically integrated DTS approach. These results align with broader discourse on sustainable logistics, which emphasises the need for systemic interventions for enhancing operational sustainability [25,101,147].

A major contribution of this study lies in a real-world application of Operations Research methodologies to address operational inefficiencies. Widely used in manufacturing and freight logistics contexts [136], application of the Transportation Model in construction remains limited to generic SC analyses and off-site production contexts [137]. Its application in the context of manufactured construction product distribution is, therefore, novel. The LP model reduces daily truck trips substantially, nearly doubling loading efficiency and capacity utilisation. This aligns with the literature, advocating algorithmic solutions for logistics problem solving [131,132]. The study also reveals structural barriers from misalignment of sustainability objectives and the ‘per-tonne’ transport pricing. A transition to ‘per-km’ pricing coupled with contractual KPIs for continuous performance monitoring and improvement, have the potential to stimulate a more sustainable operational equilibrium [151,152].

The integration of reverse logistics of plasterboard waste backhauling further enhances capacity utilisation to 58.79%, which is nearly three times that of the capacity utilisation of FIS model (19.33%). This is a step change in operational sustainability, which resonates with Circular Economy principles, which advocate for closed-loop systems to minimise resource waste [31], in this case, transportation waste. Operationalising this model, however, necessitates addressing logistical constraints like fleet standardisation and waste handling protocols. The ‘Freight Uber’ concept—leveraging digital platforms for real-time load matching—offers an innovative solution to enhance visibility and coordination [184,185]. The research also highlights the imperative of embedding NPAs in procurement frameworks to incentivise sustainability, through recalibration of tender evaluation beyond cost-centric paradigms [188,189]. Concurrently, ‘zonal warehousing’ emerges as a viable mechanism to localise inefficiencies and reduce truck movements, reinforcing the ‘floating stock’ paradigm observed in agile SCs [169,172] and implementing the emerging ‘pooled warehouse’ concept from collaborative logistics [170,171].

The study bridges theory and application, demonstrating how interdisciplinary approaches—spanning Operations Research, Supply Chain Analytics, and Circular Economy principles—can enhance sustainability of construction logistics through transport efficiency improvement. The insights provide a robust foundation for policymakers and industry leaders seeking to align logistical efficiency with improved sustainability outcomes in the construction value chain.

7. Conclusions

This study highlights the intersection between operational efficiency and sustainability in contemporary CSCs. It demonstrates how data-driven optimisation can transform logistics models by integrating analytical methodologies with business models/strategies to achieve tangible resource utilisation improvements, and therefore, enhanced operational sustainability. The research underscores aligning economic incentives with sustainability goals through innovative pricing models, performance metrics, and collaborative planning. It also demonstrates the potential of Circular Economy principles in creating closed-loop systems for minimising waste. These findings highlight the strategic opportunity presented by sustainable logistics for improved competitiveness and resilience. Advancements in digital technologies and policy frameworks can accelerate this transition by offering new pathways for balancing productivity with sustainability centred outcomes.

While addressing a major process efficiency issue pertaining to CSCs, this study has certain limitations. Its focus on manufactured construction products restricts generalisability to bulk material SCs. The findings, derived from Auckland’s ‘elongated sprawl’ in the NZ market, are likely to be different in other settings in terms of regions, products, and market fragmentation. As a retrospective analysis, the optimisation exercise develops an initial human-derived feasible solution, which, while reducing computational complexity compared to classical vehicle routing problems, may constrain potential efficiency gains. Additionally, the reverse logistics framework does not consider the temporal mismatch between material delivery and waste generation, potentially overestimating efficiency gains.

Future research can focus on certain key areas: (1) examining the scalability of findings across diverse geographies; (2) examining similar range of outcomes pertaining to different manufactured construction products; (3) empirical quantification of sustainability outcomes (reduction of emissions, congestion, noise, fossil fuel consumption, etc.); (4) monetisation of direct and indirect impacts of improved operational sustainability; and (5) decarbonisation of construction materials and the wider built environment. These can inform policy decisions and operational strategies for improved sustainability outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.T.; methodology, J.T. and K.D.; software, K.D.; validation, J.T. and K.D.; formal analysis, K.D.; investigation, J.T. and K.D.; resources, J.T.; data curation, K.D.; writing—original draft preparation, K.D.; writing—review and editing, J.T.; and supervision, J.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Auckland University of Technology Ethics Committee, New Zealand (Approval letter No. 20/272 dated 10 March 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data pertaining to this research cannot be made available due to ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used ChatGPT version 4.0 for paraphrasing and improving readability of the text. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this paper:

| 2PL | Second Party Logistics |

| BAU | Business as Usual |

| BM | Builders’ Merchant |

| CG | Centre of Gravity |

| CSC | Construction Supply Chain |

| DTS | Direct-to-Site |

| FIS | Freight-into-Store |

| GVM | Gross Vehicle Mass |

| HIAB | Hydrauliska Industri AB (colloquially used for referring to a truck mounted crane) |

| ID | Identifier |

| KPI | Key Performance Indicator |

| LP | Linear Programming |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MAPE | Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| NPA | Non-price Attribute |

| NZ | New Zealand |

| NZ$ | New Zealand Dollar (currency) |

| Q-Q | Quantile-Quantile |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination |

| RFID | Radio Frequency Identifier |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

| SC | Supply Chain |

| SMAPE | Symmetric Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for Social Sciences (software) |

| tkm | Tonne-km |

References

- Global ABC. Global status report for buildings and construction. Glob. Alliance Build. Constr. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Santamouris, M.; Vasilakopoulou, K. Present and future energy consumption of buildings: Challenges and opportunities towards decarbonisation. e-Prime-Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 2021, 1, 100002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, D.; Nemani, V.K.; Pokharel, S.; Al Sayed, A.Y. Impact of competitive conditions on supplier evaluation: A construction supply chain case study. Prod. Plan. Control. 2018, 29, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetik, M.; Peltokorpi, A.; Seppänen, O.; Leväniemi, M.; Holmström, J. Kitting logistics solution for improving on-site work performance in construction projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2021, 147, 05020020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerlain, C.; Renault, S.; Ferrero, F. Understanding construction logistics in urban areas and lowering its environmental impact: A focus on construction consolidation centres. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, F.; Tookey, J. Managing logistics cost–A missing piece in Total Cost Management. In Proceedings of the International Cost Engineering Council IX World Congress, Milano, Italy, 20–22 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Alashwal, A.M.; Fong, P.S.-W. Empirical study to determine fragmentation of construction projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2015, 141, 04015016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulford, R.; Standing, C. Construction industry productivity and the potential for collaborative practice. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2014, 32, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanem, M.; Hamzeh, F.; Seppänen, O.; Zankoul, E. A new perspective of construction logistics and production control: An exploratory study. In Proceedings of the 26th Annual Conference of the International Group for Lean Construction (IGLC), Chennai, India, 16–22 July 2018; pp. 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sezer, A.A.; Fredriksson, A. Paving the path towards efficient construction logistics by revealing the current practice and issues. Logistics 2021, 5, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Graaf, R.; Pater, R.; Voordijk, H. Level of sub-contracting design responsibilities in design and construct civil engineering bridge projects. Front. Eng. Built Environ. 2023, 3, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piecyk, M.; Allen, J.; Woodburn, A. Construction Logistics Briefing Report; Technical Report CUED/C-SRF/TR15; Centre for Sustainable Road Freight (CSRF): Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bowersox, D.J.; Closs, D.J.; Cooper, M.B.; Bowersox, J.C. Supply Chain Logistics Management; Mcgraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bulinski, J.; Waszkiewicz, C.; Buraczewski, P. Utilization of ABC/XYZ analysis in stock planning in the enterprise. In Annals of Warsaw University of Life Sciences—SGGW (Agriculture and Forest Engineering); Warsaw University of Life Sciences Press: Warsaw, Poland, 2013; pp. 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Stević, Ž.; Merima, B. ABC/XYZ inventory management model in a construction material warehouse. Alphanumer. J. 2021, 9, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryaputri, Z.; Gabriel, D.S.; Nurcahyo, R. Integration of ABC-XYZ analysis in inventory management optimization: A case study in the health industry. In Proceedings of the 3rd African International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Nsukka, Nigeria, 5–7 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lovell, A.; Saw, R.; Stimson, J. Product value-density: Managing diversity through supply chain segmentation. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2005, 16, 142–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balm, S.; Ploos van Amstel, W. Exploring criteria for tendering for sustainable urban construction logistics. In City Logistics 1: New Opportunities and Challenges; Wiley-ISTE: London, UK, 2018; pp. 251–263. [Google Scholar]

- Chatziioannou, I.; Alvarez-Icaza, L.; Bakogiannis, E.; Kyriakidis, C.; Chias-Becerril, L. A structural analysis for the categorization of the negative externalities of transport and the hierarchical organization of sustainable mobility’s strategies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.; Kersey, J.; Griffiths, P.J. The Construction Industry Mass Balance: Resource use, wastes and emissions. In Viridis Report VR4; VIRIDIS: Berkshire, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Vrijhoef, R.; Koskela, L. The four roles of supply chain management in construction. Eur. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2000, 6, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edenhofer, O. Climate change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- International Transport Forum. Decarbonising Transport: An Initiative to Help Decision Makers Establish Pathways to Carbon-neutral Mobility. Available online: https://www.itf-oecd.org/sites/default/files/decarbonising-transport-brochure.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Blancas, L.C.; Briceno-Garmendia, C. Trucking: A Performance Assessment Framework for Policymakers; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dhawan, K.; Tookey, J.E.; GhaffarianHoseini, A.; GhaffarianHoseini, A. Greening construction transport as a sustainability enabler for New Zealand: A research framework. Front. Built Environ. 2022, 8, 871958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinnon, A. Performance Measurement in Freight Transport: Its Contribution to the Design, Implementation and Monitoring of Public Policy; OECD: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Transport New Zealand Government. 2020 Green Freight Strategic Working Paper; Ministry of Transport New Zealand Government: Wellington, New Zealand, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; McGlinchy, I.; Samuelson, R. Real-World Fuel Economy of Heavy Trucks. In Proceedings of the Transport Knowledge Conference, Wellington, New Zealand, 5 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ernst & Young. The Value of Rail in New Zealand; Ministry of Transport: Wellington, New Zealand, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pundir, S.; Garg, H.; Singh, D.; Rana, P.S. A Systematic Review of Supply Chain Analytics for Targeted Ads in E-Commerce. Supply Chain. Anal. 2024, 8, 100085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Wang, T.; Chan, P.W. Forward and reverse logistics for circular economy in construction: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 388, 135981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijewickrama, M.; Chileshe, N.; Rameezdeen, R.; Ochoa, J.J. Quality assurance in reverse logistics supply chain of demolition waste: A systematic literature review. Waste Manag. Res. 2021, 39, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tischer, A.; Besiou, M.; Graubner, C.-A. Efficient waste management in construction logistics: A refurbishment case study. Logist. Res. 2013, 6, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerlain, C.; Renault, S.; Ferrero, F. Urban Freight: What about construction logistics? In Proceedings of the 7th Transport Research Arena TRA, Vienna, Austria, 16–19 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tetik, M.; Brusselaers, N.; Fredriksson, A. Conceptual model for aligning construction logistics capacity through simulation. Autom. Constr. 2025, 175, 106190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, M.K.; Venkatraj, V.; Pariafsai, F.; Bullen, J. Site logistics factors impacting resource use on construction sites: A Delphi study. Front. Built Environ. 2022, 8, 858135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzieh, A.S.; Awwad, B.S.; Razia, B.S. Review of Logistics Challenges within the Construction Industry. EuroMid J. Bus. Tech-Innov. 2025, 4, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cigolini, R.; Gosling, J.; Iyer, A.; Senicheva, O. Supply chain management in construction and engineer-to-order industries. Prod. Plan. Control. 2022, 33, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, P.E.; Irani, Z.; Edwards, D.J. A seamless supply chain management model for construction. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2004, 9, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavo, K.; Rasmus, R. The role of planning in management: Strategies to achieve organizational success. Sharia Oikonomia Law J. 2024, 2, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, P.; Holmström, J. Future of supply chain planning: Closing the gaps between practice and promise. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2016, 46, 62–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäckstrand, J.; Fredriksson, A. The role of supplier information availability for construction supply chain performance. Prod. Plan. Control. 2022, 33, 863–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besselink, B.; Turri, V.; Van De Hoef, S.H.; Liang, K.-Y.; Alam, A.; Mårtensson, J.; Johansson, K.H. Cyber–physical control of road freight transport. Proc. IEEE 2016, 104, 1128–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredriksson, A.; Flyen, C.; Fufa, S.; Venås, C.; Hulthén, K.; Brusselaers, N.; Mommens, K.; Macharis, C. Construction Logistics Scenarios and Stakeholder Involvement: Scenarios of Construction Logistics. Sweden: Minimizing Impact of Construction Material Flows in Cities: Innovative Co-creation (MiMiC); SINTEF: Trondheim, Norway, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksson, A.; Huge-Brodin, M. Green construction logistics–a multi-actor challenge. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2022, 45, 100830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredriksson, A.; Janné, M.; Peltokorpi, A. Making logistics a central core in complex construction projects: A power-dependency analysis. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2024, 42, 963–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredriksson, A.; Kjellsdotter Ivert, L.; Naz, F. Creating logistics service value in construction–a quest of coordinating modules in a loosely coupled system. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2025, 43, 428–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haag, P.; Jünger, H.C. Turning a spotlight on construction logistics for a sustainable urban environment—A review of current policy concepts and literature. Front. Built Environ. 2023, 9, 1202091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janné, M.; Fredriksson, A. Construction logistics in urban development projects–learning from, or repeating, past mistakes of city logistics? Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2022, 33, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawan, K.; Tookey, J.; GhaffarianHoseini, A.; Poshdar, M. Integrated planning as a ‘smart′ solution for improved sustainability of construction logistics: A transport perspective. In Proceedings of the Sustainability and Health: The nexus of carbon-neutral architecture and well-being: 56th International Conference of the Architectural Science Association, Launceston, Australia, 29 November–2 December 2023; pp. 406–420. [Google Scholar]

- Tserng, H.P.; Dzeng, R.J.; Lin, Y.C.; Lin, S.T. Mobile construction supply chain management using PDA and bar codes. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2005, 20, 242–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrijhoef, R.; de Ridder, H. Supply chain integration for achieving best value for construction clients: Client-driven versus supplierdriven integration. In Proceedings of the QUT Research Week, Brisbane, Australia, 4–8 July 2005; pp. 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, A.; Ireland, P. Managing construction supply chains: The common sense approach. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2002, 9, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agapiou, A.; Flanagan, R.; Norman, G.; Notman, D. The changing role of builders merchants in the construction supply chain. Constr. Manag. Econ. 1998, 16, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]