Automated Assessment of Construction Workers’ Accident Risk During Walks for Safety Planning Based on Empirical Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Breakdown Structure of Construction Accident Databases

2.2. Safety Risk Assessment in Construction

3. Indices of Construction Workers’ Accident Risk During Walks

3.1. Definition of Hierarchical ADW Risk Indices

3.2. Incorporating Worker Allocation into the ADW Risk Indices

4. Assessment of ADW Risk Based on Empirical Data

4.1. Automated ADW Risk Assessment Process

- ▪

- HL database construction: the first stage involves reshaping the reference accident case database to construct a new database that contains lift value in a hierarchical branching-tree structure (hereafter referred to as Hierarchical Lift, HL). At this stage, the safety manager must prepare a database with a structure similar to that shown in Figure 1, which will serve as a reference for assessing ADW risk in the project. The database is reduced to retain only the attributes that the safety manager intends to consider. In this hierarchical arrangement, ECs are positioned at higher levels, while SCs are positioned at lower levels. This ensures that the computation of precedes that of . During the reshaping process, the items of each attribute are reorganized into a branching tree structure, and the frequency of occurrence is recorded at each branch. These reshaped frequency data are subsequently used to compute HL. Figure 3 presents the conceptual schema of the database after reshaping and HL computation are complete. The HL database is represented as a branching tree composed of items from each attribute. Subtotals under given conditions are first calculated, after which the ARM metrics of item pairs between antecedent and consequent attributes are computed. The lift values of each branch become the primary targets for querying in subsequent steps; however, other ARM metrics, as shown in Figure 3, are also computed as prerequisite data. For example, when calculating the lift of branch ‘Item A’, the data within scope (i) are used, whereas for branch ‘Item a’, the relevant data are drawn from scope (ii).

- ▪

- Risk-condition querying: the second stage involves feeding weather forecast data into the system and querying the conditions that align with the project schedule. In this step, the safety manager defines the time window for risk analysis and inputs the corresponding work schedule into the system. Based on the provided schedule and the retrieved environmental data, the system queries the HL database to extract the HL values that match the specified conditions. Once the project work schedule is established, the project manager formulates a worker allocation plan for each scheduled task, which will serve as the basis for index computation in the subsequent stage.

- ▪

- Risk index computation: the third stage focuses on calculating the ADW risk indices for the planned work activities within the defined analysis time window. For this computation, the safety manager must provide the system with information on worker allocation for each WBS element of the work schedule. Using the risk-condition pairs obtained in the previous step together with the worker allocation data, the indices defined in Equations (4)–(7) are computed for each time unit (e.g., day, week). In parallel, this stage concurrently identifies the list of ADW-inducing objects.During the preparation of the reference database, specific attributes, such as accident-inducing objects, may contain a large number of items. If such attributes are positioned at intermediate levels of the branching tree, they can generate an excessive number of branches, many of which have no associated accident cases. This leads to undesirable fragmentation of the tree structure. To mitigate this issue, these attributes are positioned at the lowest level of the branching tree and excluded from the risk index computation. Instead, a list is generated for items with an accident frequency of at least one, ensuring that they are still captured for interpretive purposes without compromising the efficiency of index calculation. Further details of this stage can be more clearly understood through the example system interface, which will be presented later.

- ▪

- Risk reporting & visualization: the final stage involves aggregating the computation results of the ADW risk indices and delivering them to the safety manager in a comprehensible form. Since the third step computes the indices repeatedly for each time unit, this stage aggregates the outputs across iterations and organizes them into an integrated report. Time series visualizations are particularly compelling for conveying these results, as they allow managers to observe changes in risk levels over the project timeline. Examples of such visual outputs will be presented in the subsequent case studies.

4.2. Example Interface of the ADW Risk Assessment System

5. Case Studies

5.1. Description of the Applied Database and Case Projects

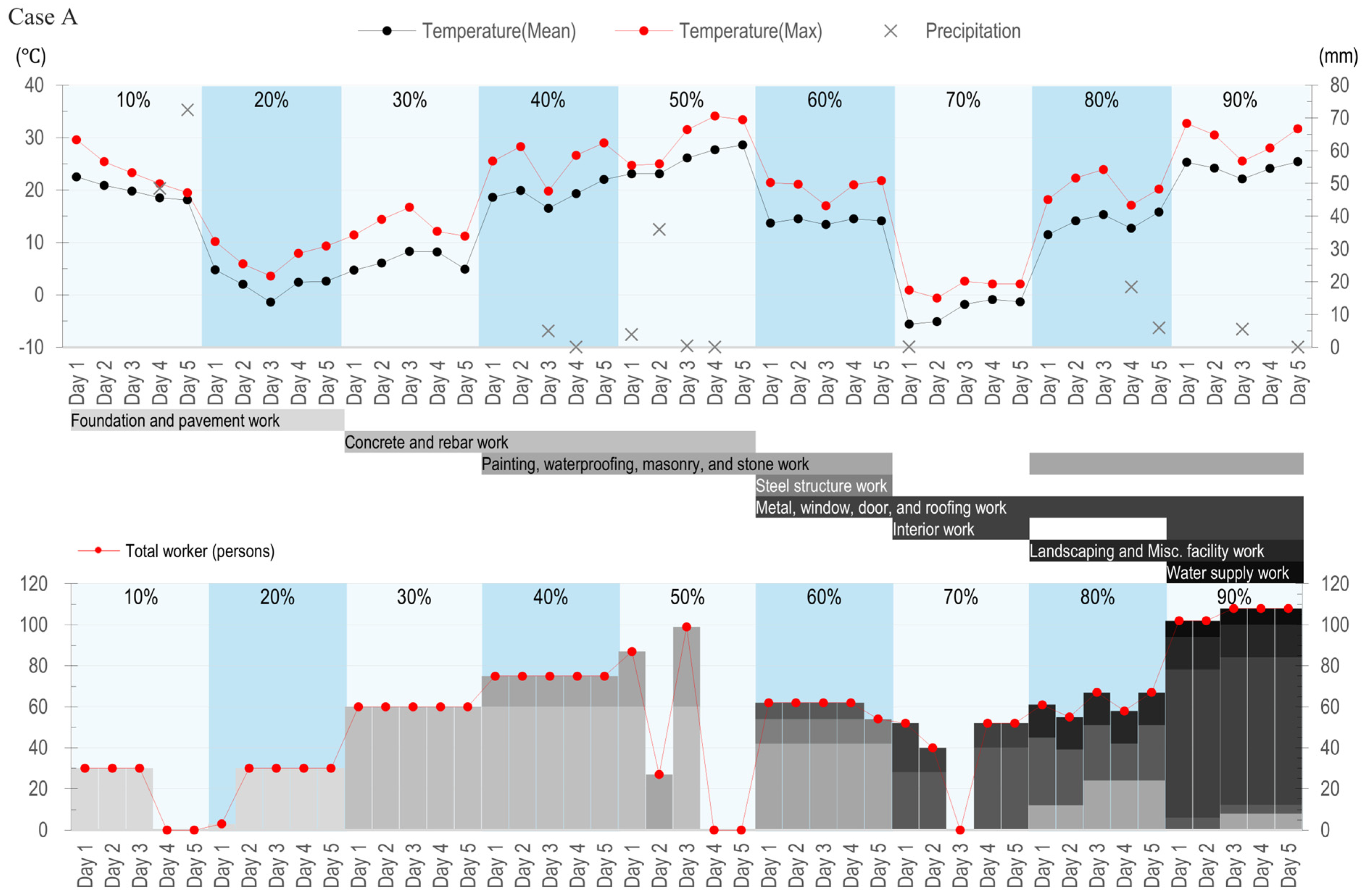

5.2. Results of ADW Risk Indices Calculation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADW | Accident During Walks |

| RIDDOR | Reporting of Injuries, Diseases, and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations |

| OIICS | Occupational Injury and Illness Classification System |

| JHA | Job Hazard Analysis |

| WBS | Work Breakdown Structure |

| STFs | Slips, Trips, and Falls |

| ADT | Accident During Tasks |

| ARM | Association Rule Mining |

| LCCA | Latent Class Clustering Analysis |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Networks |

| CFOI | Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries |

| QRAM | Qualitative Occupational Risk Assessment Model |

| CHASTE | Construction Hazard Assessment with Spatial and Temporal Exposure |

| BIM | Building Information Model |

| BN | Bayesian Networks |

| SC | Scheduling-related Conditions |

| EC | Environmental Conditions |

| ECR | Environmental Condition Risk |

| SCR | Scheduling-related Condition Risk |

| HL | Hierarchical Lift |

| CSI | Construction Safety Information System |

| BERT | Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers |

References

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Table 2. Fatal Occupational Injuries by Industry Sectors and Selected Events or Exposures(1), 2023–2023 A01 Results. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/cfoi.t02.htm (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Hale, A.; Walker, D.; Walters, N.; Bolt, H. Developing the Understanding of Underlying Causes of Construction Fatal Accidents. Saf. Sci. 2012, 50, 2020–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hide, S.; Atkinson, S.; Pavitt, T.C.; Haslam, R.; Gibb, A.; Gyi, D. Causal Factors in Construction Accidents; Online resource; Loughborough University: Loughborough, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-0-7176-2749-3. [Google Scholar]

- Hinze, J.; Russell, D.B. Analysis of Fatalities Recorded by OSHA. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 1995, 121, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozenfeld, O.; Sacks, R.; Rosenfeld, Y.; Baum, H. Construction Job Safety Analysis. Saf. Sci. 2010, 48, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayhan, B.U.; Tokdemir, O.B. Accident Analysis for Construction Safety Using Latent Class Clustering and Artificial Neural Networks. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04019114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, K.-J. Construction Workers’ Occupational Risk of On-Site Travelling Activities. Korean J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2005, 6, 120–127. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, W.-R.; Leclercq, S.; Lockhart, T.E.; Haslam, R. State of Science: Occupational Slips, Trips and Falls on the Same Level*. Ergonomics 2016, 59, 861–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socias-Morales, C.; Konda, S.; Bell, J.L.; Wurzelbacher, S.J.; Naber, S.J.; Scott Earnest, G.; Garza, E.P.; Meyers, A.R.; Scharf, T. Construction Industry Workers’ Compensation Injury Claims Due to Slips, Trips, and Falls—Ohio, 2010–2017. J. Saf. Res. 2023, 86, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, A. QRAM a Qualitative Occupational Safety Risk Assessment Model for the Construction Industry That Incorporate Uncertainties by the Use of Fuzzy Sets. Saf. Sci. 2014, 63, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Imieliński, T.; Swami, A. Mining Association Rules between Sets of Items in Large Databases. In Proceedings of the 1993 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, Washington, DC, USA, 25–28 May 1993; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 207–216. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, C.-W.; Lin, C.-C.; Leu, S.-S. Use of Association Rules to Explore Cause–Effect Relationships in Occupational Accidents in the Taiwan Construction Industry. Saf. Sci. 2010, 48, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, X.; Du, S.; Jiao, L. Critical Causal Path Analysis of Subway Construction Safety Accidents Based on Text Mining. ASCE-ASME J. Risk Uncertain. Eng. Syst. Part A Civ. Eng. 2025, 11, 04024075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; She, J.; Zhou, Y. Risk Assessment of Construction Safety Accidents Based on Association Rule Mining and Bayesian Network. J. Intell. Constr. 2024, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, R.A.; Hide, S.A.; Gibb, A.G.F.; Gyi, D.E.; Pavitt, T.; Atkinson, S.; Duff, A.R. Contributing Factors in Construction Accidents. Appl. Ergon. 2005, 36, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyi, D.E.; Gibb, A.G.F.; Haslam, R.A. The Quality of Accident and Health Data in the Construction Industry: Interviews with Senior Managers. Constr. Manag. Econ. 1999, 17, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northwood, J.; Sygnatur, E.; Windau, J. Updated BLS Occupational Injury and Illness Classification System. Mon. Labor Rev./U.S. Dep. Labor Bur. Labor Stat. 2012, 135, 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Occupational Injury and Illness Classification (OIICS) Manual. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/iif/definitions/occupational-injuries-and-illnesses-classification-manual.htm (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) TABLE A-1. Fatal Occupational Injuries by Industry and Event or Exposure, All United States, 2022. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/iif/fatal-injuries-tables/fatal-occupational-injuries-table-a-1-2022.htm (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Jannadi, O.A.; Almishari, S. Risk Assessment in Construction. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2003, 129, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, R.; Rozenfeld, O.; Rosenfeld, Y. Spatial and Temporal Exposure to Safety Hazards in Construction. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2009, 135, 726–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, H.; Hyun, J.; Lee, J.; Ahn, J. Development of A Quantitative Risk Assessment Model by BIM-based Risk Factor Extraction—Focusing on Falling Accidents. Korean J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2022, 23, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lim, H.-C. A Study on the Importance and the Necessity of Simplification of Construction Safety Manager’s Work. Korean J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2021, 22, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Lee, C.; Koo, C.; Kim, T.W. Identification of Combinatorial Factors Affecting Fatal Accidents in Small Construction Sites: Association Rule Analysis. Korean J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 21, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Han, S.; Kang, Y.; Kang, S. Affinity Analysis Between Factors of Fatal Occupational Accidents in Construction Using Data Mining Techniques. Korean J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2021, 22, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Srikant, R. Fast Algorithms for Mining Association Rules. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Very Large Data Bases, Santiago, Chile, 12–15 September 1994; Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 487–499. [Google Scholar]

- Brin, S.; Motwani, R.; Silverstein, C. Beyond Market Baskets: Generalizing Association Rules to Correlations. In Proceedings of the 1997 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, Tucson, Arizona, 13–15 May 1997; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 265–276. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Fu, Y. Mining Multiple-Level Association Rules in Large Databases. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 1999, 11, 798–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, P.-N.; Kumar, V.; Srivastava, J. Selecting the Right Objective Measure for Association Analysis. Inf. Syst. 2004, 29, 293–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport of Korea (MOLIT) Construction Safety Management Integrated Information. Available online: https://www.csi.go.kr/ (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Lee, H.-Y.; Cho, J.; Kim, T.W. Automated Classification of Construction Workers’ Walking-Related Accidents in Accident Case Database. In Proceedings of the 14th Creative Construction Conference, Zadar, Croatia, 14–17 June 2025; The International Association for Automation and Robotics in Construction, 2025; pp. 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, C. Deep Learning and Text Mining: Classifying and Extracting Key Information from Construction Accident Narratives. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamshiri, A.; Ryu, K.R.; Park, J.Y. Text Mining and Natural Language Processing in Construction. Autom. Constr. 2024, 158, 105200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Land; Infrastructure and Transport of Korea (MOLIT). Notification No. 2024-1021 Standards for Determining Construction Periods of Public Construction Projects. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/admRulSc.do?menuId=5&subMenuId=41&tabMenuId=183&query=%EA%B3%B5%EA%B3%B5%20%EA%B1%B4%EC%84%A4%EA%B3%B5%EC%82%AC%EC%9D%98%20%EA%B3%B5%EC%82%AC%EA%B8%B0%EA%B0%84%20%EC%82%B0%EC%A0%95%EA%B8%B0%EC%A4%80#liBgcolor0 (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- US Department of Commerce; National Weather Service. Wind Chill/Heat Index. Available online: https://www.weather.gov/ctp/ChillHeat (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Presidential Decree No. 33664 Enforcement Decree of the Framework Act on the Construction Industry. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/LSW/eng/engLsSc.do?menuId=2§ion=lawNm&query=ENFORCEMENT+DECREE+OF+THE+FRAMEWORK+ACT+ON+THE+CONSTRUCTION+INDUSTRY&x=24&y=23#liBgcolor0 (accessed on 8 May 2025).

| Category | Specific Methods | Key Characteristics | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative risk assessment | JHA [5], QRAM [10] |

|

|

| Quantitative risk assessment | Data-driven risk matrix [20] |

|

|

| Spatial-Temporal Analysis | CHASTE [21] |

|

|

| BIM-based risk analysis [22] |

|

| |

| Hybrid machine learning | LCCA and ANN [6] |

| (ANN)

|

| ARM-based BNs [14] |

| (Bayesian networks)

| |

| Rule-based pattern mining | ARM [12,24,25] |

|

|

| ARM-based critical path analysis [13] |

|

|

| HL Database Attribute | Case Study Application | |

|---|---|---|

| Attribute | Item | |

| EC #1 | Weather condition | Clear; Rainy; Snowy; Foggy; Windy |

| EC #2 | Temperature level | Extreme cold (below 0 °C); Cold (0–10 °C); Mild (10–26 °C); Heat (26–33 °C); Extreme heat (above 33 °C) |

| SC #1 | Work type | Foundation and pavement work; Interior work; Metal, window, door, and roofing work; Painting, waterproofing, masonry and stone work; Landscaping and miscellaneous facility work; Concrete and rebar work; Demolition and scaffolding work; Water supply work; Railway work; Steel structure work; Dredging work; Mechanical work; Piping and gas supply work; Electrical work; Incidental work |

| SC #2 | Activity type | Traveling; Excavation and piling; Equipment handling; Tamping and grading; Painting and plastering; Plumbing and wiring; Cladding and laying; Assembling and installing; Welding; Transporting and lifting; Preparation and inspection; Cleaning and tidying; Pouring and curing; Demolishing; Miscellaneous |

| Project Details | Case A | Case B |

|---|---|---|

| Project type | Educational facility | Office building |

| Construction period | 26 months | 29.8 months |

| Floor configuration | B1–6F | B4–15F |

| Site area (m2) | 19,866 | 5713 |

| Building area (m2) | 4173 | 3340 |

| Gross floor area (m2) | 19,723 | 43,410 |

| Building coverage ratio | 0.21 | 0.58 |

| Floor area ratio | 0.80 | 4.61 |

| Findings | Supporting Evidence | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Description | Project | Time Unit | Index | |||

| Capability to assess ADW risk through work schedule integration | Increased values at lower levels of the ARW indices | Case A | 40% | Day 3 | 1.55 1.77 4.46 | |

| Decreased values at lower levels of the ARW indices | Case A | 90% | Day 1 | 1.00 0.90 0.97 | ||

| Elevated ADW risk associated with trade overlap | Sharp increase in resulting from finishing-work overlap | Case A | 30% | Days 1 to 5 | 1.54 (average) | |

| Case A | 40% | Days 1 to 5 | 2.52 (average) | |||

| Identification of activities with higher ADW risk under clear and mild conditions | Higher on ‘Clear’ and ‘Mild’ days during foundation work | Case A | 10% | Day 2 | 0.99 5.72 | |

| Lower on ‘Clear’ and ‘Heat’ days during foundation work | Case A | 10% | Day 1 | 1.00 2.95 | ||

| Lower and for interior works under ‘Rainy’ and ‘Cold’ conditions | Case A | 70% | Day 1 | 0.43 0.43 | ||

| Extreme ADW risk in foundation works under harsh conditions | Higher of foundation works on ‘Snowy’ and ‘Extremely cold’ days | Case B | 10% | Day 3 | 15.04 27.34 | |

| Lower of concrete works on ‘Snowy’ and ‘Extremely cold’ days | Case B | 50% | Day 5 | 15.04 14.62 | ||

| Capability to detect high-risk activities within trade overlaps | Changes due to the combination of rainfall with structural and interior works | Case B | 60% | Day 2 | 1.00 1.68 | |

| Case B | 60% | Day 3 | 1.55 4.15 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cho, J.; Lee, H.-Y.; Kim, J.; Jang, J.; Kim, T.W. Automated Assessment of Construction Workers’ Accident Risk During Walks for Safety Planning Based on Empirical Data. Sustainability 2026, 18, 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010265

Cho J, Lee H-Y, Kim J, Jang J, Kim TW. Automated Assessment of Construction Workers’ Accident Risk During Walks for Safety Planning Based on Empirical Data. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):265. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010265

Chicago/Turabian StyleCho, Jongwoo, Ho-Young Lee, Junyoung Kim, Junyoung Jang, and Tae Wan Kim. 2026. "Automated Assessment of Construction Workers’ Accident Risk During Walks for Safety Planning Based on Empirical Data" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010265

APA StyleCho, J., Lee, H.-Y., Kim, J., Jang, J., & Kim, T. W. (2026). Automated Assessment of Construction Workers’ Accident Risk During Walks for Safety Planning Based on Empirical Data. Sustainability, 18(1), 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010265