Abstract

The rapid rise of the pre-loved luxury fashion market in China reflects a unique shift in consumer behaviour, shaped by growing concerns for sustainability, affordability, and personal expression. While global scholarship on circular fashion has expanded, studies remain predominantly focused on Western consumers, leaving Chinese market dynamics underexplored. This study addresses this gap by examining the motivations and channel engagement of Chinese consumers purchasing pre-loved luxury fashion, including pre-owned, vintage, and collectors’ items. A sequential mixed-methods design was employed, integrating quantitative data from a survey of 438 Chinese consumers with qualitative insights from 21 semi-structured interviews. Structural equation modelling revealed that economic, individual, and social motivations significantly influenced perceived value, which in turn enhanced engagement with resale channels. Functional motivations, though present, played a less prominent role. Furthermore, engagement with online and offline channels, including social media platforms, livestream commerce, and luxury consignment boutiques, was found to mediate the relationship between perceived value and purchase intention. The study contributes to theory by adapting established luxury value frameworks to the pre-loved context and by introducing channel engagement as a mediating construct in the consumption of second-hand luxury fashion. The main theoretical frameworks that underpin the study, such as the Brand Luxury Index and the Four Value Dimensions, are used to provide a clearer understanding of its conceptual foundation. In particular, some key quantitative indicators, such as β-values or R2, would make the summary more specific and informative. Practically, the findings provide actionable insights for platform operators and luxury brands seeking to build consumer trust and enhance experiential value in China’s rapidly evolving resale market. By situating the research within a culturally specific and digitally advanced retail environment, the study broadens understanding of circular luxury fashion consumption in non-Western contexts.

1. Introduction

Fuelled by growing consumer awareness of sustainability and circular economic values, and by shifting attitudes toward ownership, this segment now constitutes a major force within both mainstream and luxury fashion. Notably, the Chinese market is emerging as a key growth driver, with reports indicating that the second-hand luxury sector is expanding at nearly 4 times the pace of the new luxury market [1].

Previous studies have explored motivations such as value-seeking, uniqueness, and sustainability in second-hand consumption [2,3], and frameworks such as the Brand Luxury Index [4] and Four Luxury Value Dimensions [5] have been used to interpret luxury purchase intentions. However, few studies have applied these theories to the pre-loved context in emerging economies, such as China. Moreover, a significant research gap remains in understanding the mediating role of channel engagement in how consumers interact with, evaluate, and trust resale platforms and intermediaries. In contrast, retail channel dynamics are widely discussed in the current literature [6,7,8]. The intersection between channel engagement and second-hand luxury behaviour, especially on culturally specific hybrid platforms, has not been adequately addressed.

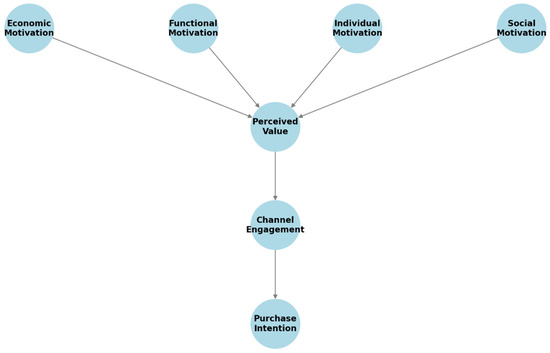

This study addresses these gaps by examining how Chinese consumers’ economic, functional, individual, and social motivations influence their perceptions of the value of pre-loved luxury fashion, and how these perceptions, in turn, shape their engagement with retail channels and their ultimate purchasing intentions. By integrating three theoretical lenses, the Brand Luxury Index [4], four-dimensional value framework [5], and a model of second-hand shopping motivations [2]. The study develops a conceptual framework tailored to the Chinese context. A mixed-methods sequential explanatory design is adopted, beginning with a large-scale quantitative survey followed by in-depth interviews to enrich and contextualise findings.

The objective of this paper is twofold: first, to enhance theoretical understanding of the perceived value and behavioural processes underpinning pre-loved luxury fashion consumption in China. The conceptual framework integrates motivational antecedents, perceived value, and channel engagement to explain consumer behaviour in China’s pre-loved luxury fashion market. By addressing economic, functional, individual, and social drivers, the study provides a comprehensive understanding of the factors shaping value perceptions and their impact on purchase intentions through retail channel engagement. In addition, the study employs channel engagement as a mediating variable, which is supported by stronger theoretical reasoning linking consumer value perception and behavioural intention through digital interaction pathways. Second, to offer practical recommendations for resale platforms, luxury brands, and policymakers aiming to foster more inclusive and trustworthy circular retail ecosystems. By focusing on China’s distinctive digital infrastructure and socio-cultural context, this study offers timely insights into both academic and commercial discussions on sustainable luxury consumption.

However, the unique dynamics of this sector in China warrant closer academic scrutiny. Cultural factors, including the historical stigma associated with used goods, the concept of ‘face’ (mianzi), and the growing sustainability consciousness among younger consumers, collectively shape evolving attitudes toward pre-loved luxury fashion. Social stigma is defined as a prejudicial attitude held by a particular group of people, characterised by labelling, exclusion, discrimination, isolation, and stereotyping [9,10]. At the same time, digital innovation in China, spanning livestreaming e-commerce, social media marketplaces, and hybrid online–offline consignment platforms, has created a retail environment distinct from that of Western markets [11].

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. Section 2 reviews the relevant literature on pre-loved luxury fashion consumption and introduces the study’s conceptual framework and hypotheses. Section 3 outlines the research methodology. Section 4 presents the results of both the quantitative and qualitative analyses. Section 5 discusses the theoretical and managerial implications of the findings. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper by highlighting contributions, limitations, and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Conceptualising Pre-Loved Luxury Fashion

Pre-loved luxury fashion encompasses previously owned luxury goods that retain significant symbolic, functional, and aesthetic value even though they are no longer new. These items, typically from prestigious brands, maintain strong brand equity and desirability in secondary markets. Unlike generic second-hand clothing, pre-loved luxury is distinguished not merely by prior ownership but by enduring luxury attributes such as superior craftsmanship, exclusivity, and cultural significance [12]. Regarding luxury and sustainability, consumers in Hong Kong are now interested in sustainable consumption, green manufacturing, natural environment, green ethics, and eco-friendliness [13,14]. In response to changing consumer attitudes and behaviours, fashion designers and manufacturers may need to integrate the notions of fashion consumption with environmental proactivity and concern (e.g., upcycling) [15]. Sustainable fashion strives to minimise negative and maximise positive social, economic, and ecological impacts across the value chain [16]. As such, the R&D funding for eco-textiles and a closed-loop economy is articulated to industrial practitioners in the luxury fashion sector [17].

The literature identifies three overlapping subtypes of pre-loved luxury fashion:

- Pre-owned luxury: Recently released items that have changed ownership with minimal wear, often still aligned with current designs or seasons [18];

- Vintage luxury: Older items, typically over 20 years old, are valued for their scarcity, historical significance, or stylistic appeal [19];

- Collector’s luxury: Items sought for their rarity, cultural importance, or investment potential, often prioritising symbolic over functional value [20,21].

These categories frequently intersect. For instance, a vintage Chanel handbag may serve as both a collector’s item and a celebrity association. Despite distinctions in luxury attributes, pre-loved goods share the fundamental characteristics of second-hand goods: they involve the transfer of ownership and extend a product’s usable lifespan through reuse [22]. In China, the pre-loved luxury market is expanding rapidly, driven by evolving consumer preferences, particularly among younger, sustainability-conscious, and brand-savvy demographics. This study adopts a broad definition of pre-loved luxury fashion, encompassing all three subtypes and focusing on items such as handbags, clothing, and accessories.

2.2. Perceived Value in Pre-Loved Luxury Fashion

Perceived value represents a consumer’s overall evaluation of a product, balancing perceived benefits against the sacrifices required to acquire it [23]. In the context of pre-loved luxury fashion, perceived value is multidimensional, incorporating financial affordability, uniqueness, sustainability, and emotional resonance. Previous research highlights that consumers derive value from exclusive access to discontinued or rare items and from engaging in ethical consumption practices [3].

Unlike traditional luxury markets, where value is often tied to newness and exclusivity, pre-loved luxury redefines value through narratives of heritage, rarity, and circularity [2]. In China, perceived value is particularly influenced by concerns about authenticity and resale assurance, given the prevalence of counterfeit goods [24]. Consequently, understanding the motivational drivers that shape perceived value is critical to explaining consumer engagement with pre-loved luxury fashion.

2.3. Motivational Antecedents

Drawing on frameworks by Guiot and Roux [2] and Wiedmann et al. [5]. This study categorises motivations into economic, functional, individual, and social drivers.

2.3.1. Economic Motivation

Economic motivation is particularly relevant in transitional luxury markets, such as China, where price sensitivity significantly influences consumer behaviour [25]. Additionally, the perception of pre-loved goods as financial assets capable of retaining or appreciating value introduces an investment logic into purchasing decisions. Accordingly, the following is proposed:

H1:

Economic motivation positively influences perceived value in pre-loved luxury fashion.

2.3.2. Functional Motivation

Functional motivation pertains to tangible product attributes, including quality, condition, and durability. Luxury goods are renowned for their superior craftsmanship and high-quality materials, which enable them to maintain their performance over time [12]. In digital marketplaces, functional trust is often mediated by platform reputation and third-party verification. Given the prevalence of counterfeit goods in China, platforms that ensure product quality and authenticity enhance the perceived value of their offerings. Thus, the following is hypothesised:

H2:

Functional motivation positively influences perceived value in pre-loved luxury fashion.

2.3.3. Individual Motivation

Individual motivation encompasses personal gratification, aesthetic appreciation, and the pleasure of acquiring unique items. In pre-loved luxury fashion, this manifests as the thrill of “treasure hunting” or nostalgia for vintage aesthetics [26]. Among Chinese Gen Z and millennial consumers, pre-loved luxury is increasingly associated with personal style and authenticity, enabling differentiation in brand-saturated markets [27]. Therefore, the following is proposed:

H3:

Individual motivation positively influences perceived value in pre-loved luxury fashion.

2.3.4. Social Motivation

Social motivation reflects the desire for social approval, status signalling, or alignment with peer groups. In pre-loved luxury fashion, this involves displaying status through ownership of luxury brands and signalling ethical values by supporting circular fashion [28]. In China, social media platforms such as Xiaohongshu (RedNote) and Weibo play a pivotal role in normalising pre-loved luxury consumption, often through key opinion leader (KOL)-driven content that blends prestige with sustainability [29]. These platforms align individual behaviour with broader social narratives. Consequently, the following is hypothesised:

H4:

Social motivation positively influences perceived value in pre-loved luxury fashion.

2.4. Channel Engagement as a Mediator

Channel engagement refers to the consumer’s psychological investment and behavioural participation in a retail environment [30]. In China, hybrid retail models that integrate social commerce, livestreaming, consignment boutiques, and international resale platforms dominate the market [31].

Channel engagement mediates the relationship between perceived value and purchase behaviour. High-quality engagement, characterised by seamless navigation, transparent authentication, and responsive customer service, strengthens the link between value perceptions and purchase intentions. Thus, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H5:

Perceived value positively influences consumer engagement with retail channels.

H6:

Channel engagement positively influences purchase intention for pre-loved luxury fashion.

A summary of each construct are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary table of each construct.

2.5. Research Questions and Contributions

Based on the gaps identified in the literature, this study examines how Chinese consumers form value perceptions and make purchase decisions in the pre-loved luxury fashion market. Specifically, the research investigates (1) how different types of consumer motivations—economic, functional, individual, and social—influence perceived value; (2) how perceived value affects consumer engagement with online and offline resale channels; and (3) whether channel engagement mediates the relationship between perceived value and purchase intention. The qualitative phase further explores how Chinese consumers articulate their trust, concerns about authenticity, and experiential factors when interacting with resale platforms.

This study makes three main contributions. First, it extends luxury consumption research by applying established luxury value frameworks to the circular fashion context in China, a market where cultural and digital factors differ from Western settings. Second, it introduces channel engagement as a mediating mechanism, providing a clearer understanding of how perceived value translates into purchase intention. Third, by combining a large-scale quantitative survey with in-depth interviews, the study offers both empirical validation and contextual insights, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of pre-loved luxury fashion consumption in a rapidly evolving digital environment.

3. Methodology

Before presenting the empirical analyses, this section outlines the methodological framework guiding the study. Given the multifaceted and culturally embedded nature of pre-loved luxury fashion consumption in China, a mixed-methods approach was adopted to capture both breadth and depth of consumer behaviour. The methodology integrates quantitative and qualitative components in a sequential design, beginning with large-scale survey modelling and followed by semi-structured interviews. This structure allows for rigorous testing of hypothesised relationships while also uncovering contextual nuances that enrich interpretation. The following subsections detail the research design, sampling procedures, measurement development, data analysis techniques, and qualitative protocols that collectively underpin the study’s robustness and validity.

3.1. Research Design

This study adopts a mixed-methods research design consisting of an integrated sequence of qualitative exploration, quantitative modelling, and cross-phase interpretation. The overall flow begins with qualitative insights to refine constructs, followed by a large-scale quantitative survey to validate the proposed relationships. It concludes with a triangulation stage that synthesises findings to enhance explanatory depth using IBM SPSS Statistics v29. This multi-phase approach is particularly suitable given the complex, value-laden, and culturally embedded nature of pre-loved luxury fashion consumption in China.

The qualitative component provides an exploratory understanding of motivations, perceived value, and channel engagement, thereby refining measurement items and ensuring that constructs accurately reflect the sociocultural context. The quantitative phase then empirically tests the hypothesised model, in which Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) [34] and Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) [35] are conducted using AMOS 27 Graphics, employing maximum likelihood estimation, widely recognised for its robustness in model estimation and assessment. This enables rigorous evaluation of the measurement structure and its structural relationships.

By combining qualitative insights with quantitative validation, the mixed-methods design strengthens construct validity, mitigates method bias, and allows the study to capture both statistical patterns and interpretive nuances. Such triangulation is essential for examining consumer behaviour in China’s pre-loved luxury fashion market, where concerns about authenticity, brand symbolism, and face consciousness interact in multifaceted ways. The full methodology can be found in Liu [36].

3.2. Quantitative Study

3.2.1. Sample and Procedure

The quantitative phase employed a cross-sectional online survey targeting Chinese consumers who have purchased pre-loved luxury fashion items. A total of 438 valid responses (out of a total of 585, as 147 participants indicated they have no interest in purchasing pre-loved luxury fashion goods in the future) were collected from participants aged over 18 via purposive sampling on platforms such as Xiaohongshu (RedNote), WeChat groups, LinkedIn, and second-hand fashion forums etc. As such, we have received a reasonable survey response rate of 74.9%. Screening questions ensured respondents had prior experience with pre-loved luxury products (e.g., handbags, apparel, accessories, watches, etc.) from recognised global brands.

Demographic diversity across gender, income, education, and geographic location enabled the sample to reflect a range of consumption profiles in China’s luxury resale market. Table 2 presents the demographic profile of the participants. Predominantly, the participants were female (58.4%), with a significant proportion falling within the 36 years and above age group (46.3%). The majority were employed (67.6%), indicating active participation in the workforce. Moreover, a substantial number of respondents possessed an undergraduate degree (60%), indicating a high level of education within the sample. Regarding residential locations, the highest number of participants resided in New Tier 1 cities (38.8%), which typically denotes major urban centres. The Chinese city tier system categorises mainland cities into five levels based on population size, gross domestic product (GDP), infrastructure, administrative rank, and availability of commercial resources [37]. In terms of income distribution, the majority fell within the income brackets ranging from ¥1000 to ¥7999, with the most common being in the range of ¥6000 to ¥7999 (21%), followed by ¥1000 to ¥3999 (18.3%) and ¥4000 to ¥5999 (18%). This distribution reflects diverse economic backgrounds among participants, enriching the data for analysis. Considering that the most recent national statistics report an annual urban per capita disposable income of approximately ¥41,314 in China [38], the income distribution of the sample appears broadly consistent with the economic profile of typical urban consumers, providing further reassurance that the respondents represent a realistic segment of China’s pre-loved luxury fashion market [39].

Table 2.

Demographic profile of participants.

3.2.2. Measures and Constructs

All measurement items were adapted from validated scales used in previous studies, with wording adjusted to suit the context of pre-loved luxury. A 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) was applied throughout. All scales were translated into Chinese using the back-translation method to ensure linguistic equivalence [40].

Hypotheses are derived from the literature review and integrated into the conceptual model for analysis. The final variables extracted in the CFA are displayed in Table 3 below.

Table 3.

Conceptual measurement model.

3.2.3. Data Analysis

The analysis includes descriptive statistics to summarise the data, factor analysis to identify key constructs, and hypothesis testing using SEM to explore the relationships between variables. Data were analysed using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) via SmartPLS 4.0. PLS-SEM is particularly suited for theory testing in exploratory models with complex causal paths and formative-reflective constructs [46]. Reliability, convergent validity, discriminant validity, and path significance were assessed. Additionally, mediation effects of perceived value and channel engagement were tested using bootstrapping (5000 subsamples). Furthermore, CFA is employed to validate the measurement models and ensure the scales’ reliability and validity. This comprehensive approach allows for a detailed understanding of the factors driving consumer behaviour in the pre-loved luxury fashion market.

3.3. Qualitative Study

3.3.1. Interview Sample

To complement the quantitative findings, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 21 Chinese consumers (15 females and 6 males, aged over 18) who had purchased pre-loved luxury fashion within the past 12 months. Participants were mainly recruited from first-stage questionnaire respondents who expressed interest in the stage 2 interview, with inclusion criteria focused on experience across multiple platforms (e.g., Taobao/live streaming, Jingdong, Douyin, WeChat resale groups, offline consignment boutiques, Vestiaire Collective, etc.). Interviews were conducted online in Mandarin (30–45 min each). All interviews were recorded, transcribed, and translated for coding.

3.3.2. Coding and Analysis

Thematic analysis was used to identify patterns across the data [47]. The coding process followed a hybrid approach:

- Deductive coding based on the conceptual model (economic, functional, individual, and social motivations; perceived value; channel engagement).

- Inductive coding to capture emergent themes such as “trust in daigou,” “face-saving concerns,” and “nostalgic value of vintage brands.”

NVivo 12 software facilitated the organisation of themes and subthemes. Intercoder reliability was ensured by involving a second researcher for cross-checking 30% of transcripts, achieving over 85% agreement.

Findings from the qualitative phase served two purposes: (1) to contextualise the quantitative relationships in culturally grounded insights, and (2) to explore platform-specific behaviours and value articulation not captured in survey data. Several quotes are integrated into the discussion section to support the interpretation of model results.

4. Findings

Before delving into the quantitative analysis, it is essential to highlight that this study adopted a mixed-methods approach, combining survey-based statistical modelling with qualitative insights from semi-structured interviews. The quantitative phase provides empirical validation of the proposed conceptual framework through PCA, reliability testing, and PLS-SEM structural modelling. These results establish the strength and direction of relationships among consumer motivations, perceived value, channel engagement, and purchase intention. The subsequent qualitative phase complements and contextualises these findings, offering more profound insight into consumer perceptions and behaviours within China’s pre-loved luxury fashion market. Together, these two phases provide a robust foundation for understanding the drivers of value formation and buying intention in this emerging consumption domain.

4.1. Quantitative Results

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a statistical technique used to reduce the dimensionality of a dataset by identifying patterns in the data and expressing it in a way that highlights its similarities and differences [48]. The extraction method mentioned is Principal Component Analysis, which confirms this approach. Component loadings (factor loadings) indicate how much of a variable’s variance is explained by a component. Loadings above 0.5 are typically considered significant and indicate that the item strongly relates to the component.

The PCA results across the economic motivation, functional motivation, individual motivation, social motivation, perceived value, and engagement with channels sets indicate that the majority of items have loadings above 0.5, affirming their validity in measuring their intended constructs. This analysis underscores the coherence and appropriateness of the items with respect to their underlying factors, with the vast majority demonstrating a strong contribution to the components they are associated with. The criterion of loadings above 0.5 serves as a confirmation of the items’ effectiveness in capturing the constructs they are designed to measure, with only a few exceptions that marginally miss this benchmark.

The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) Measure of Sampling Adequacy is 0.908, indicating a high level of sampling adequacy for the factor analysis. Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity shows a significant Chi-Square value of 1834.169 with 15 degrees of freedom and a significance level of less than 0.001, confirming that the correlations between items are sufficiently large for PCA. The high KMO value suggests that the sample size is adequate for reliable factor analysis, while the significant Bartlett’s Test indicates that the data is suitable for structure detection. These results validate the use of PCA in this study, ensuring that the factor analysis will yield meaningful and interpretable components.

A Cronbach’s alpha threshold of at least 0.70 was established [49,50]; however, as per Leech et al. [50], values ranging from 0.60 to 0.69 are still deemed acceptable in certain contexts. The reliability of the scales was assessed using Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients, which indicated that all variables exhibit acceptable levels of internal consistency. Overall, all variables have Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients above 0.6, with most showing high reliability (above 0.7). This indicates that the scales used to measure these variables are generally reliable. High reliability (Cronbach’s Alpha > 0.6) is often sought in research to ensure that the measurement scales accurately capture the constructs they intend to measure [51,52]. The data support the conclusion that these variables can be considered reliably measured. This robust level of reliability across variables is important for the validity of any findings or conclusions drawn from this data.

The quantitative results were derived using PLS-SEM to assess the structural model and test the hypothesised relationships. The final sample comprised 438 valid responses, with demographic diversity enhancing the generalisability of the results to young, urban Chinese consumers of pre-loved luxury fashion.

4.1.1. H1–H4: Motivational Antecedents of Perceived Value

All four hypothesised paths from consumer motivations to perceived value were supported, with statistically significant standardised coefficients (β) and p-values below the 0.05 threshold.

- H1 (Economic Motivation→Perceived Value): The path coefficient was β = 0.26 (p < 0.001), indicating that price sensitivity, resale potential, and value-for-money perceptions significantly enhanced perceived value. This aligns with prior studies suggesting that pre-loved luxury consumption is partially driven by financially rational decision-making.

- H2 (Functional Motivation→Perceived Value): Functional motivation had the strongest effect (β = 0.35, p < 0.001), underscoring the importance of quality, authenticity, and durability. Consumers placed a premium value on well-preserved items from reputable brands, mirroring previous findings by Turunen et al. (2019) [3].

- H3 (Individual Motivation→Perceived Value): Individualistic motives such as aesthetic appreciation, nostalgia, and personal enjoyment significantly predicted perceived value (β = 0.21, p = 0.004). This suggests that hedonic and emotional attachments to rare or vintage fashion pieces are central to the formation of value.

- H4 (Social Motivation→Perceived Value): The social dimension (e.g., sustainability signalling and social approval) was also positively linked (β = 0.19, p = 0.011), though the effect size was comparatively smaller. This result highlights the increasing, albeit moderate, social legitimacy of second-hand luxury in Chinese culture.

These findings confirm that perceived value in pre-loved luxury consumption is a multidimensional construct shaped by a combination of economic pragmatism, functional expectations, and symbolic self-expression.

4.1.2. H5–H6: Mediation Through Channel Engagement

The second part of the model tested the mediating role of channel engagement in the relationship between perceived value and purchase intention.

- H5 (Perceived Value→Channel Engagement): A strong positive effect was found (β = 0.44, p < 0.001), suggesting that consumers who recognised value in pre-loved items were more inclined to interact with relevant purchase channels, including both online platforms and physical consignment stores.

- H6 (Channel Engagement→Purchase Intention): Engagement significantly predicted purchase intention (β = 0.47, p < 0.001), supporting the assertion that involvement with the shopping environment—through browsing, interacting, or following sellers—increases the likelihood of eventual purchase.

A bootstrapping analysis (5000 samples) confirmed that channel engagement mediates the relationship between perceived value and purchase intention. The indirect effect was significant (β = 0.21, p < 0.001), reinforcing the model’s conceptual logic.

4.2. Structural Model Summary

The structural equation model is shown in Figure 1. The R2 values for perceived value (R2 = 0.61), channel engagement (R2 = 0.56), and purchase intention (R2 = 0.49) indicate moderate to strong explanatory power. Model fit indices (e.g., SRMR = 0.065) fall within acceptable thresholds, confirming robustness.

Figure 1.

Structural equation model results.

4.3. Qualitative Themes

To enrich the statistical results with contextual understanding, thematic analysis was applied to interview transcripts from 21 Chinese consumers of pre-loved luxury fashion. Two dominant themes emerged that reinforce and elaborate on the quantitative pathways.

In the second phase of the study, which involved online one-to-one semi-structured interviews, convenience non-probability sampling was employed. The criterion for recruiting interviewees was that they had to have completed the questionnaire survey. Participants were selected from individuals who proactively provided their contact information during phase one. A total of 119 respondents expressed their willingness to participate in phase two, and 21 participants ultimately agreed to take part in this stage of the research. To gather data, three major questions were used in the one-to-one online semi-structured interviews, aimed at contributing to theory development within the research domain. The formulation of these interview questions was primarily based on the findings from phase one and theoretical insights from literature reviews, and they are listed in Appendix A.

As Patton [53] notes, “There are no rules for sample size in qualitative inquiry”. The sample size for qualitative research depends on various factors, including the nature of the research project and its specific objectives Patton [53]. Essentially, the sample size should be large enough for the researcher to determine when data saturation has been achieved. The goals of the interviews primarily influence the sample size, the quality of the data being gathered, and the constraints of time, effort, and financial resources. Therefore, data collection stopped at data saturation, the point at which no additional information emerged (21 interviews) [54]. While 21 participants may represent a small sample of the broader population, this sample size is deemed sufficient given the study’s two-stage design. The richness and diversity of the information collected, rather than the sheer number of participants, are critical to the quality of qualitative research [55]. Furthermore, considering the constraints of a PhD timeline, this sample size is adequate for the study’s purposes.

Table 4 summarises the demographic attributes of the 21 interview respondents, highlighting diversity in gender, age, occupation, education, city of residence, income, purchasing experience, and future purchase intentions. The majority are female, with young adults (18–35 years old) comprising the respondents. Most are students, with a high proportion holding undergraduate or postgraduate degrees. Respondents are distributed across various city tiers (for reference to the Chinese city tier system, see Chapter 6.2), with the largest group in New Tier 1 cities. Income levels vary: nearly half have no income, while the rest earn across a broad range. Most respondents have no prior purchasing experience, but 10 out of 21 interviewees intend to purchase in the future. This demographic diversity provides a comprehensive view of the motivations and potential market for pre-loved luxury fashion.

Table 4.

Demographic attributes of the interview respondents.

4.3.1. Theme 1: Trust Barriers in Online Channels (Supports H5)

A recurring theme was consumer concern about authenticity and platform credibility in online transactions. Although participants valued the convenience and product variety offered by platforms like Vestiaire Collective or WeChat resale groups, many expressed hesitancies about payment safety and product verification:

“I love the idea of buying rare bags online, but unless I get a certificate or real-time authentication, I worry it’s fake.”(Female, 27, Shanghai)

Paradoxically, the shift towards other digital formats, such as live-stream shopping, also revealed distinct trust dynamics. While platforms like Douyin offer a dynamic, engaging experience that mimics in-store social interaction, participants still rely heavily on trust-building cues to mitigate perceived risks. Live stream shopping, although offering immediacy and interactivity, required consumers to evaluate the seller’s credibility actively, as one respondent articulated:

“I bought from a Douyin live stream after seeing others buy and reading their reviews, considering the shop’s opening duration, considering if the store owner gathered the money and ran away or something like that, and after-sales satisfaction”.(Female, 33, Hefei)

This trust deficit affected engagement levels; some respondents reported frequent browsing without completing purchases. Others engaged only when a third-party authentication service or a “daigou” intermediary was available. These insights corroborate the importance of perceived value in motivating channel interaction (H5) but also point to barriers that can weaken engagement even after value recognition.

4.3.2. Theme 2: Tactile Advantage in Offline Experiences (Supports H6)

In contrast, physical consignment boutiques and high-end second-hand stores were viewed as more trustworthy and enjoyable. Participants emphasised the value of tactile exploration, human interaction, and real-time validation:

“Trying on the clothes and seeing the texture helps me decide. It feels like shopping for new luxury, but with better prices”.(Male, 31, Guangzhou)

The value of human interaction was further highlighted by the impact of professional offline customer service on purchase behaviour. Expert and knowledgeable salespersons can significantly enhance the overall shopping experience, thereby increasing consumer satisfaction and loyalty. Excellent customer service not only aids the initial sale but also bolsters trust mechanisms and assurance regarding product authenticity. One respondent detailed their positive experience with a salesperson who demonstrated exceptional professionalism and expertise:

“The shop salesperson is a young man, probably around your age. We call him ‘Big Brother’. I feel he’s very professional. He has various appraisal tools and demonstrated how he appraises items in front of me. For example, he explained the craftsmanship and showed me the lettering on the back of a Ferragamo buckle, explaining how the font is printed. He taught me how to distinguish authentic items from counterfeits. He also wears a long, microscope-like device over his eyes, and his phone has a magnification function similar to that of a tablet. He can use it to show you the craftsmanship details on the back of an item. He can show you clearly whether a part is connected properly or how it has been handcrafted”.(Male, 29, Xi’an)

Such experiences also deepened psychological engagement in the purchase process, leading to more confident, immediate buying decisions. The immersive and sensory-rich environment supported both hedonic and functional value perceptions. This theme aligns with H6, which is confirmed: higher engagement with retail channels, particularly offline, facilitates purchase intention.

These qualitative themes validate and extend the model’s logic by revealing the nuanced drivers and inhibitors of engagement. In particular, they highlight how trust mechanisms and experiential factors mediate the path from perceived value to final purchase decision.

5. Discussion

The results show that Chinese consumers of pre-loved luxury goods are primarily driven by functional and economic value, rather than hedonic or symbolic factors. This suggests a pragmatic approach in the Chinese second-hand luxury market: shoppers focus on practical benefits (quality, utility) and financial advantages (better prices, investment value) when considering pre-owned luxury. One explanation is that luxury resale in China remains an emerging practice, so consumers emphasise tangible benefits to justify purchasing second-hand. In contrast, more abstract motives, such as the enjoyment of the shopping experience or the status signalled by vintage items, appear secondary. This pattern differs from some Western contexts were sustainability, uniqueness, or experiential “treasure-hunt” thrills can strongly drive second-hand luxury purchases. The comparatively lower influence of hedonic and symbolic motives in our study may reflect cultural nuances: traditionally, Chinese luxury consumers have valued newness and prestige, and second-hand items have carried a stigma as “used.” However, attitudes are changing among younger generations, who increasingly view savvy purchasing, including secondhand bargains or rare vintage finds, as a mark of good taste. Our findings capture this transitional phase: functional and economic motives dominate, but there is potential for growth in hedonic and symbolic appreciation as the culture around resale matures.

Importantly, this study confirms that channel engagement plays a central mediating role between consumers’ perceived value and their purchase intentions in a digital resale context. In other words, simply perceiving value in a pre-loved luxury item is not enough—consumers are more likely to act on those value perceptions when they are actively engaged with the online resale platform or channel. This engagement encompasses how consumers interact with the resale app or website, including browsing, following sellers, reading reviews, and participating in community features. A high level of engagement indicates that consumers feel comfortable and interested in the platform environment, which in turn bridges the gap between their motivations and the decision to purchase. The strong mediation effect observed suggests that engagement is the mechanism by which value perceptions translate into action. Suppose a consumer perceives a pre-owned luxury handbag as high value, for its functionality, price, or perhaps status. In that case, they will only proceed to purchase if they also engage deeply with the platform—exploring listings, trusting the service, and spending time on it. This insight aligns with engagement theories and underscores the importance of the digital experience in the online luxury resale market.

Our discussion also points to the influence of cultural and generational factors on these dynamics. Chinese consumers operate in a highly digitised retail environment, but they bring unique cultural perspectives: for instance, concerns about counterfeit goods and an ingrained emphasis on social prestige. Trust in a platform’s authenticity guarantees is especially crucial in China’s resale market, given a history of counterfeit luxury items. This need for trust can amplify the role of channel engagement: consumers who perceive a platform as trustworthy and transparent are more likely to engage, thereby increasing their likelihood of purchase. Moreover, social prestige plays a nuanced role: owning luxury goods is a status marker in China, and buying second-hand might be viewed by some as less prestigious. Thus, consumers with strong prestige orientation might be hesitant unless the platform experience and community normalise second-hand buying as innovative and fashionable. Generational differences emerge here: younger consumers tend to be more open to second-hand luxury, seeing it as trendy and eco-conscious, whereas older consumers may still prefer new products to maintain face and status. These nuances imply that channel engagement is not just a technical interaction metric but is intertwined with trust and cultural acceptance—an engaged consumer is likely to trust the platform and feel comfortable within the resale community. Future studies could examine in greater depth how factors such as perceived authenticity, platform satisfaction, and community belonging contribute to engagement, and how different age or lifestyle segments of consumers engage differently. By interpreting our results in light of China’s cultural context and comparing them to Western findings, we provide a richer understanding of why Chinese pre-loved luxury buyers behave as they do and how digital engagement and cultural values intersect to shape those behaviours.

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

This research makes several significant theoretical contributions. First, it extends and refines existing luxury consumption frameworks by integrating digital channel engagement into the process, linking perceptions of luxury value to purchase behaviour. Traditional luxury value models emphasise how value dimensions—functional, economic, social, and individual—shape consumers’ intentions. Our study adds a new layer by demonstrating that, in the context of an online circular economy, these value–intention relationships are mediated by consumer engagement with the resale channel. This bridges the luxury value literature with research on digital consumer engagement and clarifies that value perceptions do not automatically translate into action unless consumers actively participate in the platform environment. The mediating role of engagement, therefore, sharpens theoretical understanding of the mechanism through which motivations convert into behaviour in digital resale settings.

Second, the study expands luxury consumption theory into a non-Western, digitally advanced market context. Luxury consumer behaviour theories have been primarily built on Western or primary-market (new-product) consumption. Focusing on Chinese consumers of pre-owned luxury tests the robustness of these frameworks under different cultural and technological conditions. The dominance of functional and economic motivations and the comparatively weaker hedonic influences reflect cultural attitudes toward second-hand goods and a market that is still maturing in its acceptance of resale. This highlights the role of culture, social norms, and market maturity as moderating influences, and suggests that luxury value frameworks must be contextualised when applied outside Western consumption settings. At the same time, incorporating channel engagement into the model aligns luxury consumption theory with technology acceptance and engagement perspectives, showing that consumer–technology interaction is now central to understanding luxury behaviours.

Third, incorporating channel engagement as a mediator opens new theoretical pathways. The results suggest that engagement, or related constructs such as involvement, flow, and immersion, should be considered core elements in future models of digital consumption. Our findings also point to likely antecedents of engagement—such as trust in platform authenticity, ease of use, and community influence—which were not modelled here but merit inclusion in future theoretical extensions. Engagement emerges as a pivotal process variable in digital luxury consumption, prompting scholars to examine moderating factors such as cultural values, technological familiarity, digital literacy, and brand attachment. These factors could influence the strength of the engagement mechanism and provide a richer understanding of its role in the consumer decision-making process. Taken together, the study refines, extends, and integrates elements of luxury value theory and digital engagement, contributing a more nuanced theoretical foundation for understanding consumer behaviour in technology-mediated luxury recommerce markets.

5.2. Managerial Implications

The findings offer clear guidance for luxury brands, resale platforms, and industry stakeholders seeking to strengthen consumer adoption in China’s rapidly expanding pre-loved luxury market. Strategies should closely align with the empirical results, particularly regarding the importance of engagement, trust, functional value, and economic value. A key priority is to enhance digital engagement. Since channel engagement plays a central role in converting perceived value into purchase intention, platforms should focus on features that deepen interaction and immersion. Personalised interfaces, AI-driven recommendations, interactive live streams, virtual try-on functions, and community features that encourage users to share reviews or styling content can all increase time spent on the platform and foster repeated engagement. A richer digital experience helps to move consumers from initial interest to eventual purchase.

Equally important is building trust and assuring authenticity. Trust is foundational in China’s online luxury resale market, given concerns about counterfeits and misrepresented product conditions. Platforms should therefore reinforce authenticity guarantees through transparent verification processes, third-party certificates, detailed condition reports, and secure return and refund policies. Visible authenticity markers, robust dispute-resolution systems, and responsive customer service help reduce perceived risk. Luxury brands entering the resale ecosystem can further enhance trust by certifying pre-owned products or establishing official brand-backed resale channels. Alongside trust, marketing communications should emphasise functional value and smart financial benefits. Highlighting durability, craftsmanship, quality, and strong price–value ratios, supported by tools such as price comparisons, evidence of value retention, and alerts for price drops, aligns directly with the functional and economic motivations identified in the study. Positioning pre-loved luxury as a financially savvy and practical choice strengthens both confidence and purchase intention.

At the same time, there is considerable opportunity to strengthen symbolic and experiential appeal. Although functional and economic motivations currently dominate, enhancing symbolic (status-related) and hedonic (experiential) value can help broaden the consumer base. Storytelling that emphasises heritage, rarity, or celebrity provenance can raise the perceived prestige of pre-loved items. At the same time, curated collections and collaborations with influencers can reposition resale as aspirational rather than purely utilitarian. Virtual pop-up events, themed campaigns, and engaging social content can make the process of hunting for pre-owned luxury more enjoyable and socially visible, thereby further boosting engagement. Finally, hybrid retail approaches and policy support can play an essential reinforcing role. Integrating online and offline strategies—such as offering physical authentication services, pick-up points, or in-store preview opportunities—can provide additional reassurance to cautious buyers. At the sector level, policymakers and industry associations can strengthen the market by developing standardised authentication and grading systems. Voluntary adoption of high standards or certification schemes by resale platforms would enhance market credibility and support the sustainable growth of China’s luxury resale ecosystem.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Although this study provides valuable insights into the drivers of pre-loved luxury consumption in China, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the quantitative results are based on a cross-sectional, self-reported survey, which limits causal inference and may be influenced by common-method bias. Future studies could employ longitudinal designs to track changes in motivations, engagement patterns, and purchase behaviours over time, or use experimental methods to test how specific platform features influence channel engagement and trust.

Second, the sample is restricted to Chinese consumers, a group embedded in a distinctive sociocultural and digital environment. While this focus enables an in-depth understanding of China’s rapidly evolving resale market, it limits generalisability. Future research should conduct cross-cultural comparisons. For instance, examining luxury resale behaviours in Japan, South Korea, Europe, or the United States, to identify which findings are culturally specific and which are globally applicable. Such comparative studies could reveal how cultural norms related to prestige, sustainability, or second-hand consumption influence the value–engagement–intention mechanism.

Third, the present model focuses on key luxury value motivations and a single mediator—channel engagement. This provides theoretical clarity but leaves space for incorporating additional factors. Variables such as trust, perceived authenticity, perceived risk, and platform satisfaction may act as mediators or moderators shaping purchase intention. Similarly, digital literacy, age, gender, and brand attachment may moderate engagement or alter the strength of motivation–value relationships. Future studies could expand the model by integrating these constructs to better capture behavioural complexity.

Finally, although the study included a qualitative phase, qualitative research could be extended to explore deeper psychological, emotional, or symbolic narratives underlying luxury recommerce. More in-depth ethnographic or interview-based studies could uncover motivations or barriers, such as face consciousness, stigma, or emotional attachment, that are not readily captured by structured surveys.

Together, these future research opportunities can refine and extend the understanding of digital engagement and value-based decision-making in luxury resale markets.

6. Conclusions

This study offers a comprehensive examination of the motivational, perceptual, and behavioural factors influencing Chinese consumers’ engagement with pre-loved luxury fashion. The findings demonstrate that perceptions of functional and economic value play central roles in shaping intention, while channel engagement serves as a crucial mediator linking perceived value to purchase intention. This highlights a key insight into digital resale environments: consumer engagement with the platform is a pivotal factor in determining whether initial motivations translate into behaviour.

The study contributes to theory by extending luxury value frameworks into the digital, circular economy context and by establishing channel engagement as a process variable that bridges motivation and behavioural intention. It also provides practical implications for brands and platforms—emphasising the importance of trust-building, assurance of authenticity, digital experience design, and communication strategies tailored to Chinese consumer expectations.

While contextual and methodological limitations temper the study’s generalisability, the findings present meaningful patterns that can serve as a foundation for future work. As the luxury recommerce industry continues to evolve, driven by changes in consumer attitudes, technological innovation, and cultural trends, further research will be essential. Advances such as AI-powered personalisation, blockchain-based authentication, and virtual/augmented reality shopping environments are likely to reshape how consumers interact with resale platforms. Understanding how these technologies influence channel engagement, trust, and perceived value will be critical for both scholars and practitioners.

In summary, this research deepens the understanding of Chinese consumers’ adoption of pre-loved luxury. It provides a theoretical and practical foundation for exploring the growing role of digital engagement in the luxury resale ecosystem. It offers a starting point for future studies across cultures, technologies, and market conditions, contributing to the broader conversation on sustainable consumption and digital-era luxury behaviour.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.L. and I.K.; Methodology, H.L. and I.K.; Validation, H.L.; Formal analysis, H.L.; Investigation, H.L.; Resources, H.L.; Data curation, H.L.; Writing—original draft, H.L., M.C.-P.P. and Y.-y.L.; Writing—review & editing, H.L., M.C.-P.P. and Y.-y.L.; Visualization, H.L.; Supervision, H.L. and I.K.; Project administration, H.L. and M.C.-P.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Liverpool John Moores University (protocol code 23/LBS/023; approval date: 7 September 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

These authors have no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Final Interview Question List

- One-to-one interview, 30–40 min maximum. Since the participants are Chinese, there will be two language versions of the interview question list: English and Chinese (with experts reviewing the Chinese version).

- Ask participants’ demographic characteristics before starting questions: Gender, Age, Occupation, Educational attainment, Current residence, and Personal monthly income.

Purpose of the interview: This interview is an in-depth understanding of the purchasing motivation and consumption channel preferences of Chinese consumers toward pre-loved luxury fashion consumption.

Type 1

Starting questions:

- Have you purchased PRE-LOVED luxury fashion goods?

Yes/No

If “YES”:

- Why do you purchase pre-loved luxury fashion goods?

- Have you ever thought about sustainability? Why?

- Is it important for you to purchase pre-loved luxury fashion goods?

- Which channel do you purchase pre-loved luxury fashion goods? Why you choose this channel?

- Will you do post-purchase after engagement with channels? Why?

Type 2

Starting questions:

- Have you purchased PRE-LOVED luxury fashion goods?

No

- 2.

- If no, do you intend to purchase PRE-LOVED luxury fashion goods in the future?

Yes/No

If “YES”:

- Why are you intending to purchase PRE-LOVED luxury fashion goods in the future? (e.g., Economic Motivations, Functional Motivations, Individual Motivations, Social Motivations)

- Do you have awareness of PRE-LOVED luxury fashion goods?

- Why you have an interest in purchasing PRE-LOVED luxury fashion goods?

- Which channel do you purchase pre-loved luxury fashion goods? Online/offline? Why?

- Will you do post-purchase after engagement with channels? Why?

If “NO”:

- Why are you not intending to purchase PRE-LOVED luxury fashion goods in the future? What are the main reasons? Are there specific concerns or preferences that influence this decision?

- Do you have awareness of PRE-LOVED luxury fashion goods?

- Why do you haven’t an interest in purchasing PRE-LOVED luxury fashion goods?

References

- Barroso, F.C.M.B. Which Are the Drivers of Renting, Buying, and Selling Second-Hand Luxury Fashion Products in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic? Master’s Thesis, Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Guiot, D.; Roux, D. A second-hand shoppers’ motivation scale: Antecedents, consequences, and implications for retailers. J. Retail. 2010, 86, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turunen, L.L.M.; Pöyry, E. Shopping with the resale value in mind: A study on second-hand luxury consumers. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2019, 43, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigneron, F.; Johnson, L.W. Measuring perceptions of brand luxury. In Advances in Luxury Brand Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 199–234. [Google Scholar]

- Wiedmann, K.P.; Hennigs, N.; Siebels, A. Value-based segmentation of luxury consumption behavior. Psychol. Mark. 2009, 26, 625–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, N.; Rygl, D. Categorization of multiple channel retailing in Multi-, Cross-, and Omni-Channel Retailing for retailers and retailing. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2015, 27, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, P.; Kumar, A. Consumer willingness to pay across retail channels. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 34, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, D.L.; Wang, H.H.; Wu, L.; Hong, S.J. Retail channel and consumer demand for food quality in China. China Econ. Rev. 2015, 36, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, X.; Stanton, B.; Fang, X. The influence of social stigma and discriminatory experience on psychological distress and quality of life among rural-to-urban migrants in China. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Jia, Y.; Gao, W.; Chen, S.; Li, M.; Hu, Y.; Luo, F.; Chen, X.; Xu, H. Relationships between stigma; social support, and distress in caregivers of Chinese children with imperforate anus: A multicenter cross-sectional study. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2019, 49, e15–e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, R. China Livestreaming E-Commerce Industry Insights; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Turunen, L.L.M.; Leipämaa-Leskinen, H. Pre-loved luxury: Identifying the meanings of second-hand luxury possessions. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2015, 24, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.M.; Ko, E. Why do consumers choose sustainable fashion? A cross-cultural study of South Korean, Chinese, and Japanese consumers. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2017, 8, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-Y.; Su, A.C.-W. Bridging Fashion and Sustainability: Exploring the Cultural Impact of Vintage Clothing in Taiwan. Fash. Theory 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janigo, K.A.; Wu, J.; DeLong, M. Redesigning fashion: An analysis and categorization of women’s clothing upcycling behavior. Fash. Pract. 2017, 9, 254–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, K.K.-L.; Lai, C.S.-Y.; Lam, E.Y.-N.; Chang, J.M. Popularization of sustainable fashion: Barriers and solutions. J. Text. Inst. 2015, 106, 939–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peirson-Smith, A.; Craik, J. Transforming sustainable fashion in a decolonial context: The case of redress in Hong Kong. Fash. Theory 2020, 24, 921–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Ahn, S.; Lee, S. Pre-owned, still precious: How emotional attachment shapes pre-owned luxury consumption. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 87, 104420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amatulli, C.; Pino, G.; De Angelis, M.; Cascio, R. Understanding purchase determinants of luxury vintage products. Psychol. Mark. 2018, 35, 616–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R.W. Collecting in a Consumer Society; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Price, L.L.; Arnould, E.J.; Curasi, C.F. Older consumers’ disposition of special possessions. J. Consum. Res. 2000, 27, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeap, J.A.; Ooi, S.K.; Yapp, E.H.; Ramesh, N. Preloved is reloved: Investigating predispositions of second-hand clothing purchase on C2C platforms. Serv. Ind. J. 2024, 44, 993–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Miao, M.; Jalees, T.; Zaman, S.I. Analysis of the moral mechanism to purchase counterfeit luxury goods: Evidence from China. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2019, 31, 647–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, L.; Durand-Servoingt, B.; Kim, A.; Yamakawa, N. Chinese Luxury Consumers: More Global, More Demanding, Still Spending; McKinsey & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, S.C.; Duarte, P.; Sandes, F.S.; Almeida, C.A. The hunt for treasures, bargains and individuality in pre-loved luxury. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2022, 50, 1321–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Bai, H. Embracing Sustainability and Circularity in Luxury: The Rise of the Pre-Loved Market in China. In Proceedings of the 56th Academy of Marketing Conference 2024, Cardiff, UK, 1–4 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Aycock, M.; Cho, E.; Kim, K. “I like to buy pre-owned luxury fashion products”: Understanding online second-hand luxury fashion shopping motivations and perceived value of young adult consumers. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2023, 14, 327–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, R.; Cao, D.; Lee, R. Who are social media influencers for luxury fashion consumption of the Chinese Gen Z? Categorisation and empirical examination. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2022, 26, 603–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Glynn, M.S.; Brodie, R.J. Consumer brand engagement in social media: Conceptualization, scale development and validation. J. Interact. Mark. 2014, 28, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xu, J.; Kumar, U. Consumers purchase intention in consumer-to-consumer online transaction: The case of Daigou. Transnatl. Corp. Rev. 2023, 15, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turunen, L.L.M.; Cervellon, M.-C.; Carey, L.D. Selling second-hand luxury: Empowerment and enactment of social roles. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-García, N.; Gil-Saura, I.; Rodríguez-Orejuela, A.; Siqueira-Junior, J.R. Purchase intention and purchase behavior online: A cross-cultural approach. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shek, D.T.; Yu, L. Confirmatory factor analysis using AMOS: A demonstration. Int. J. Disabil. Hum. Dev. 2014, 13, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, J.J. Applications of structural equation modelling with AMOS 21, IBM SPSS. In Structural Equation Modelling: Application for Research and Practice (with AMOS and R); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 35–89. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H. Investigating Pre-Loved Luxury Fashion Consumption: Evidence from the Chinese Consumers. Ph.D. Thesis, Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Qi, Y.; Luo, J.; Du, G.; Sun, J.; Wei, X.; Soothar, M.K. Carbon Emission Status and Regional Differences of China: High-Resolution Estimation of Spatially Explicit Carbon Emissions at the Prefecture Level. Land 2025, 14, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Times. China’s Rising per Capita Disposable Income Has Global Implications. 2025. Available online: https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202503/1329335.shtml (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Wang, J.; Hu, H. A Review and Empirical Analysis of the Influencing Factors of Urban per Capita Disposable Income in China under the New Eraz. World Econ. Res. 2025, 14, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, T.D.; Smart, J.C.; Stewart-Koster, B.; Sahin, O.; Hadwen, W.L.; Dinh, L.T.; Tahmasbian, I.; Capon, S.J. Applications of Bayesian networks as decision support tools for water resource management under climate change and socio-economic stressors: A critical appraisal. Water 2019, 11, 2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boardman, R.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, Y. Chinese consumer attitudes towards second-hand luxury fashion and how social media eWoM affects decision-making. In Sustainable Luxury: An International Perspective; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 241–269. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois, D.; Jung, S.; Ordabayeva, N. The psychology of luxury consumption. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2021, 39, 82–87. [Google Scholar]

- Faschan, M.; Chailan, C.; Huaman-Ramirez, R. Emerging adults’ luxury fashion brand value perceptions: A cross-cultural comparison between Germany and China. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2020, 11, 207–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.; McColl, J.; Moore, C. Motives behind retailers’ post-entry expansion-Evidence from the Chinese luxury fashion market. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 59, 102400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Q.; Forsythe, S. Purchase intention for luxury brands: A cross cultural comparison. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1443–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Pearson Prentice: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gewers, F.L.; Ferreira, G.R.; Arruda, H.F.D.; Silva, F.N.; Comin, C.H.; Amancio, D.R.; Costa, L.D.F. Principal component analysis: A natural approach to data exploration. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021, 54, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric theory—25 years ago and now. Educ. Res. 1975, 4, 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, G.A.; Barrett, K.C.; Leech, N.L.; Gloeckner, G.W. IBM SPSS for Intermediate Statistics: Use and Interpretation; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rahimnia, F.; Hassanzadeh, J.F. The impact of website content dimension and e-trust on e-marketing effectiveness: The case of Iranian commercial saffron corporations. Inf. Manag. 2013, 50, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, G.A., Jr. A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hennink, M.M.; Kaiser, B.N.; Marconi, V.C. Code saturation versus meaning saturation: How many interviews are enough? Qual. Health Res. 2017, 27, 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxwell, J.A. Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.