A Qualitative Assessment of Metro Operators’ Internal Operations and Organisational Settings

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Investigated the organisational settings—an underexplored dimension of metro operators in existing research.

- Established a “Community of Practice” among an extensive range of metro operators to identify useful insights into metro systems’ internal operations and organisational settings.

- Created a three-dimension framework for analysing metro operators’ organisational structures and internal operational practices.

- Generated evidence and insight for metro operators and governing authorities in terms of the current status of good practices, areas of consensus, and future innovative strategies of metro operations, which collectively underscore the importance of adaptable strategies and cross-sector collaboration for advancing resilient, efficient, and secure metro systems.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Organisational Structures Within Metro Operators

2.2. Inter-Organisational Collaboration and Governance

2.3. Hybrid and Collaborative Governance

2.4. Governance of Railway Network

2.5. Future Metro Systems and Risk Governance

2.6. Comparative Framework of Organisational Models

2.7. Summary of Findings from the Literature

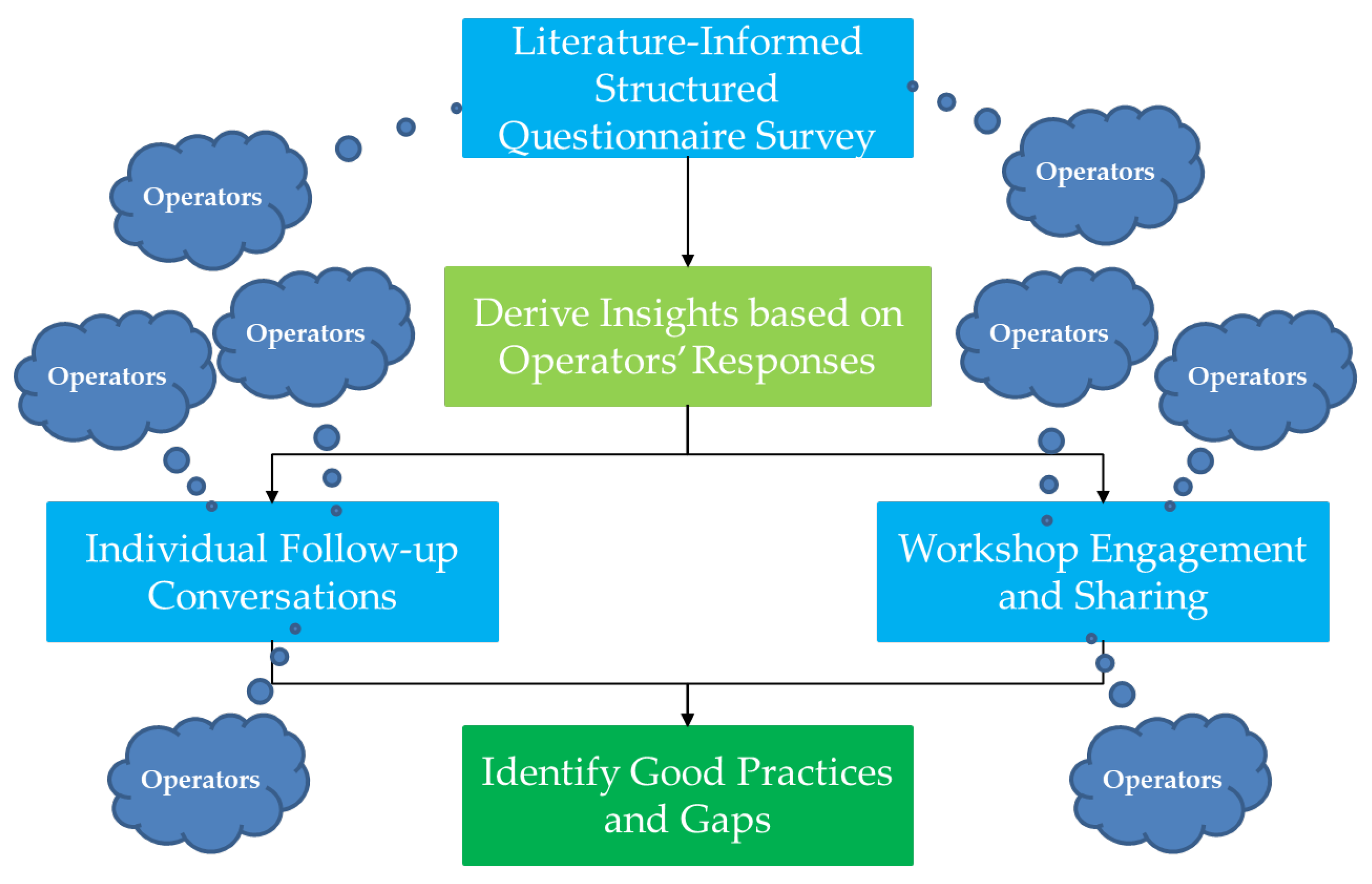

3. Method and Data

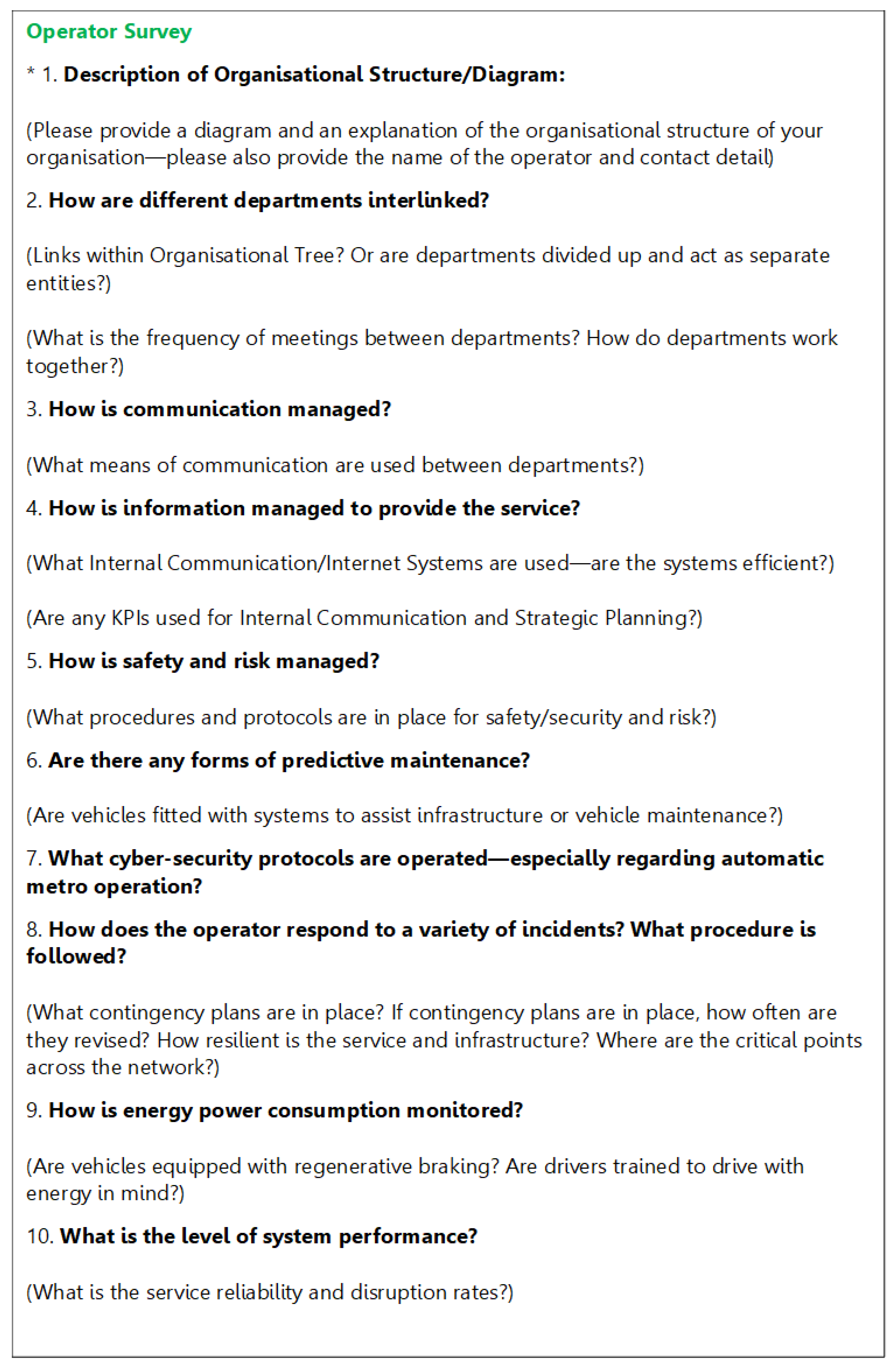

3.1. Questionnaire Survey Design

3.2. Workshop

- Q1: Does the network have any forms of predictive maintenance?

- Q2: How are energy consumption levels monitored on each line(s)?

- Q3: If metro lines are automated, what cyber-security measures are in place?

3.3. Data Analysis

- Static Dimension: The overall organisational and governance structure of the metro operators is analysed to understand which organisational models are adopted.

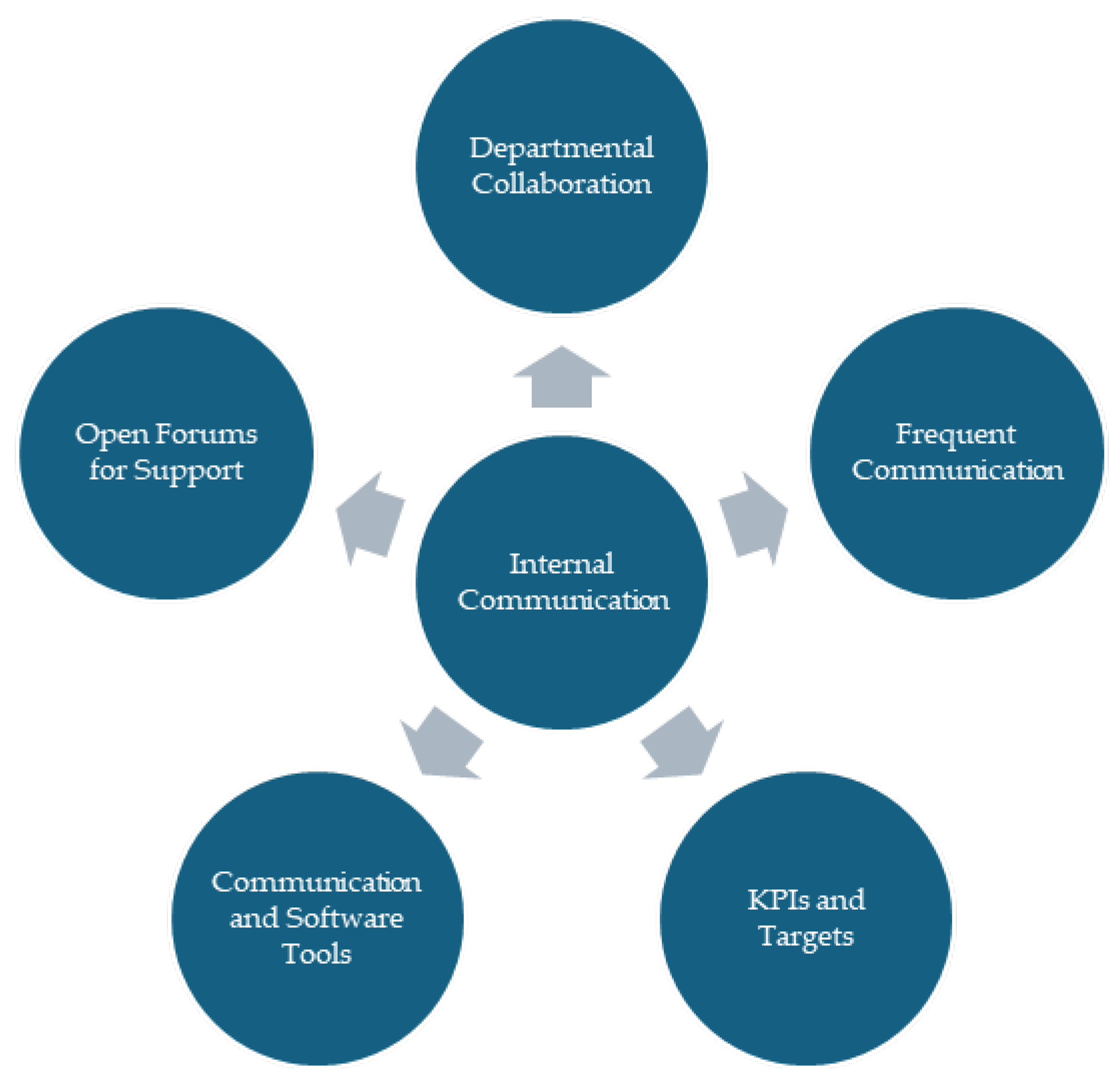

- Dynamic Interplays Dimension: The connections, means of communication, as well as information exchange and management between departments are analysed to explore how different departments collaborate to perform daily operations.

- Fundamental Operations Dimension: Practices related to some important daily metro operations are analysed and assessed to identify any good practices and potential gaps or areas of improvements.

4. Results and Findings

4.1. Static Dimension: Overall Organisational and Governance Structure

4.2. Dynamic Interplays Dimension

4.2.1. Departmental Collaboration

4.2.2. Communication Management

4.2.3. Information Management

4.3. Fundamental Operations Dimension

4.3.1. Safety and Risk Management

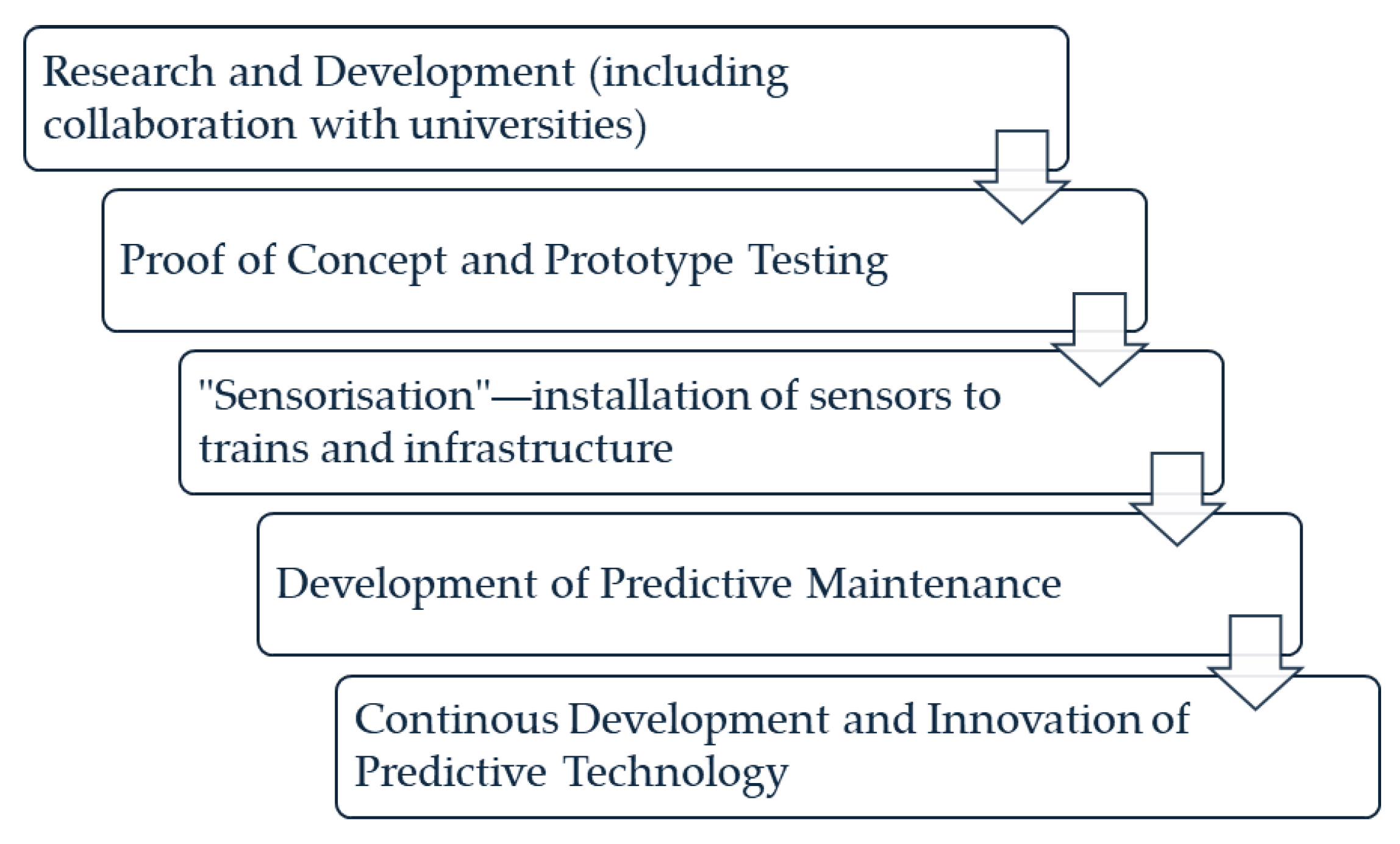

4.3.2. Predictive Maintenance

4.3.3. Cyber-Security

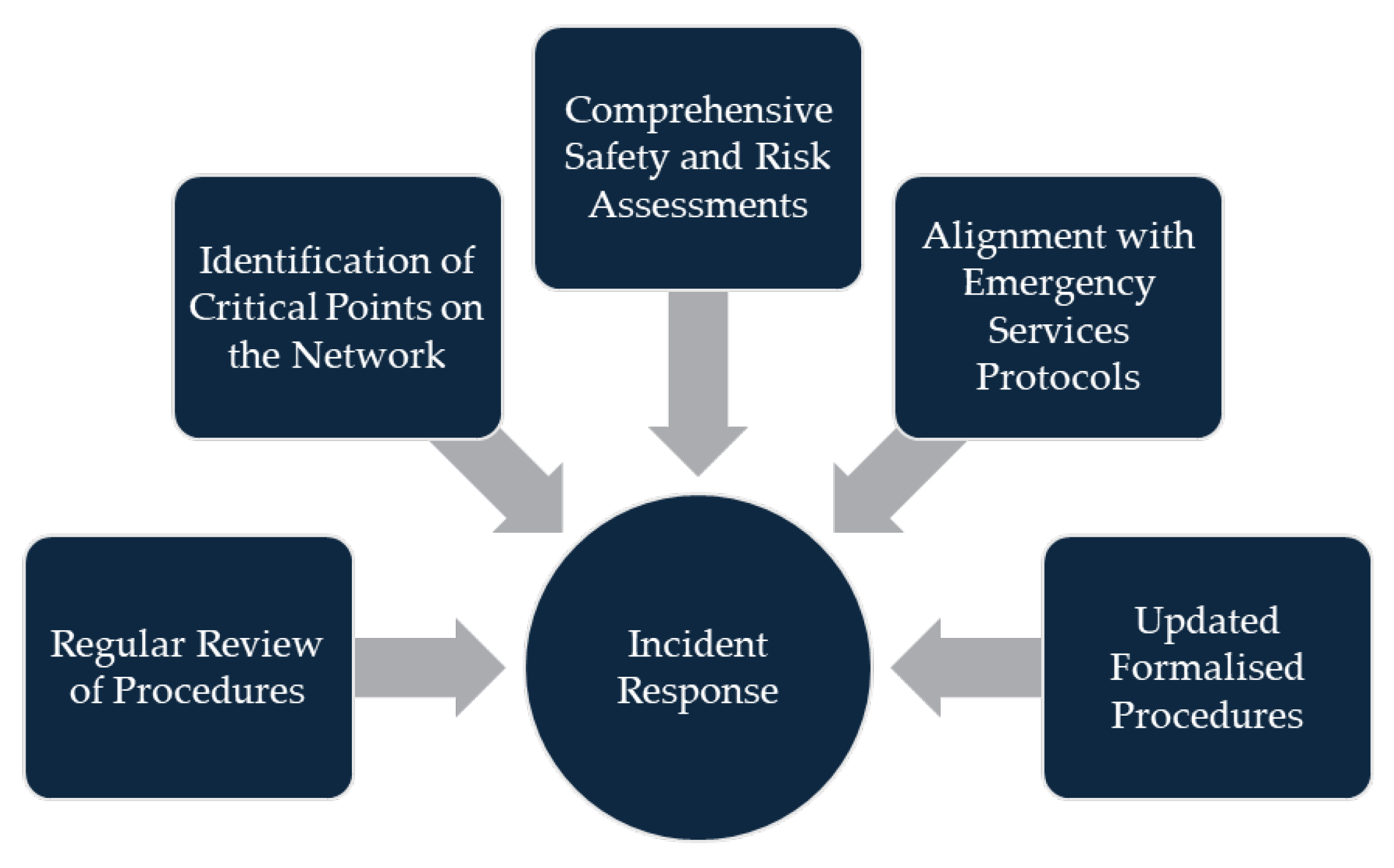

4.3.4. Incident Management

4.3.5. Energy Consumption

4.4. Performance

5. Discussions

6. Conclusions

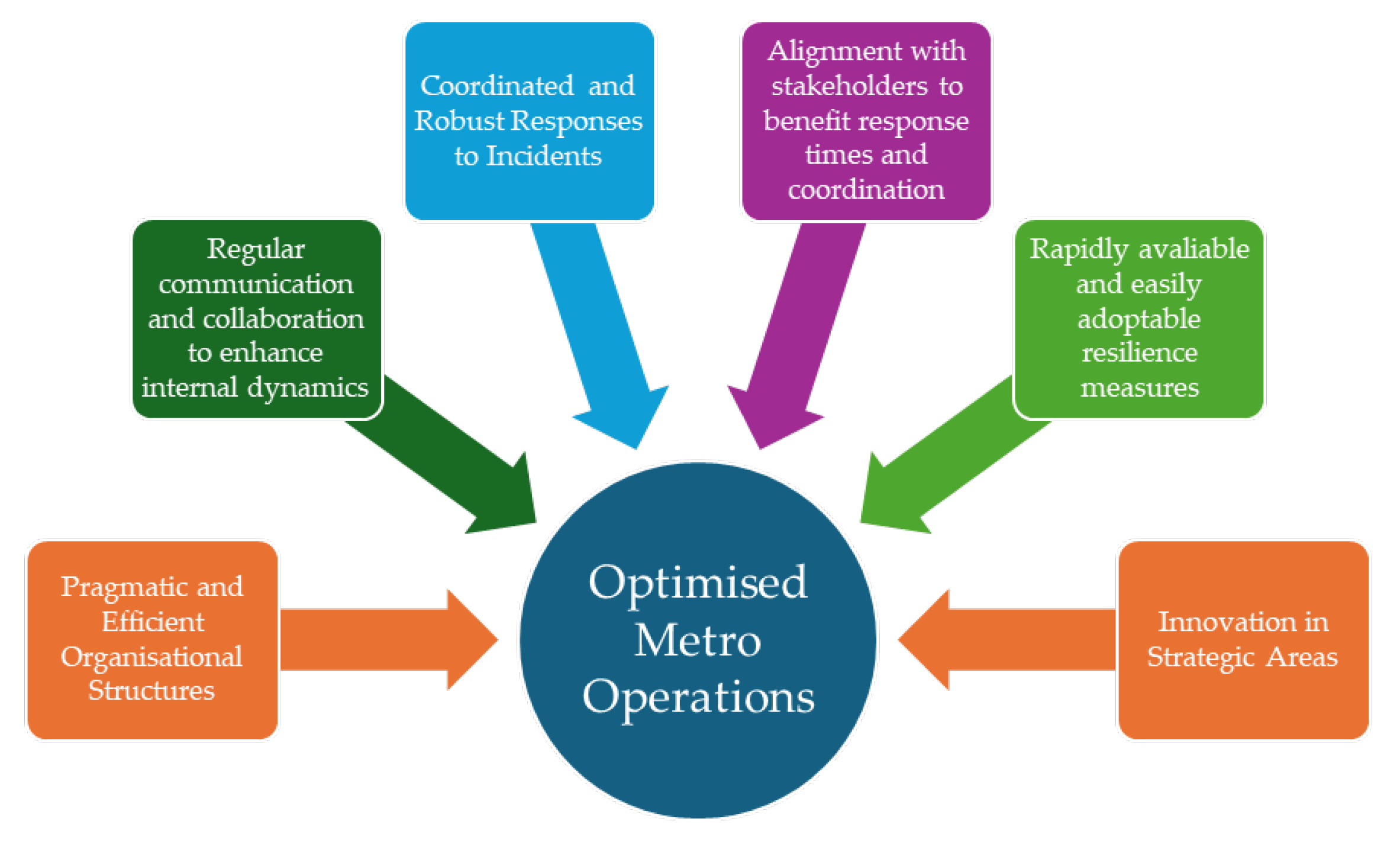

- From the static organisational perspective, operators typically adopt a hierarchical structure with defined departments. However, the general consensus is that there is no ideal organisational structure for operators to follow; instead, a pragmatic and hybrid model may provide the best balance between efficiency, adaptability, and creativity in contemporary metro systems by fusing decentralised or collaborative operational roles with central strategic oversight.

- As for dynamic interplays between departments, current practices revealed that the way and frequency of communications varied across different operators. The general consensus is that collaboration and flexibility are key for enhancing metro operation, engaging with various stakeholders, to supplement metro service delivery.

- Safety is undoubtedly a crucial aspect of metro operations; operators address potential hazards and emergency situations, mitigating and responding to incidents with robust procedures, highlighting the actions that operators can take to minimise risk. A key theme across various operators was the compliance with national and international regulations as a key feature of metro operator’s safety protocols.

- A recurring theme in the literature is the integration of stakeholders, which is illustrated as essential for strategic planning, crisis and emergency responses, and effective risk management.

- Predictive maintenance is an innovative strategy, with widely acknowledged benefits across metro operators, such as optimised maintenance schedules, cost savings, as well as reducing service disruption. However, cost, age of existing rolling stocks, as well as capacity and scalability of the existing data system have been identified as key implementation barriers.

- With technology advancing, cyber-security protocols must be comprehensive and regularly updated; therefore, close collaboration between the operator, rolling stock manufacturers, software manufacturers, and local government is crucial for protecting data.

- Consensus was reached between operators as metro networks are classified as critical infrastructure; therefore, they are required to adhere to national and international regulations regarding cyber-security.

- Regarding energy consumption, the grade of automation is a significant factor which influences energy consumption, and energy savings have been noted on automated lines.

7. Avenues for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Disclaimer

References

- Zhao, N.; Roberts, C.; Hillmansen, S.; Tian, Z.; Weston, P.; Chen, L. An integrated metro operation optimization to minimize energy consumption. Transp. Res. Part C 2017, 75, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.K. Strategic management of metro systems: Enhancing sustainability and urban mobility. IOSR J. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2024, 19, 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, H.; Wang, C.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S. Optimizing Energy Efficiency in Metro Systems Under Uncertainty Disturbances Using Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.13443v3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.C.; Xiao, X.M.; Wang, Y.H. Key factors identification for the energy efficiency of metro system based on DEMATEL-ISM. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Control, Electrical Engineering and Rail Transit; ICEERT 2022. Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2023; Volume 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, S.; Konings, R. The transition to zero-emission buses in public transport—The need for institutional innovation. Transp. Res. Part D 2018, 64, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparre, A.; Burlando, C.; Pavanini, T. The electrification of local public transport as a strategic wayfinding process: Policy implementation, path dependence, and organizational practices in Italy. Transp. Res. Part A 2025, 201, 104648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldbury, K.; Isaksson, K. Governance arrangements shaping driverless shuttles in public transport: The case of Barkarbystaden, Stockholm. Cities 2021, 113, 103146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, M. Organisational restructuring of Indian Railways. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2022, 10, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, E.; Sakai, H. Control and coordination in railway business: Implications for intermediate organisational forms between vertical separation and integration. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2022, 45, 100905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babalık-Sutcliffe, E. Urban rail operators in Turkey: Organisational reform in transit service provision and the impact on planning, operation and system performance. J. Transp. Geogr. 2016, 54, 464–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, W.; Zhang, H. Inter-organizational collaboration after institutional reform in China: A perspective based on the revision of the emergency plan. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 98, 104084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomo, A.; Iacono, M.P.; Mercurio, L.; Mangia, G.; Todisco, L. Regulation, governance and organisational issues in European Railway Regulation Authorities. J. Rail Transp. Plan. Manag. 2024, 29, 100428. [Google Scholar]

- Dementiev, A.; Alexandersson, G. Workshop 2A report: Public transport governance via contracting, collaboration, and hybrid organisational arrangements. Res. Transp. Econ. 2024, 103, 101394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, J. Transport institutions and organisations in the formulation of policies for Australian local area traffic management: A 50-year retrospective. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. (Engl. Ed.) 2023, 10, 866–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, H. China’s high-speed rail industrial organization structure reform under inter-modal competition. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2024, 54, 101114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Tang, T.; Ning, B. System dynamics approach for modelling the variation of organizational factors for risk control in automatic metro. Saf. Sci. 2017, 94, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doroshin, I.; Kazaryan, R. Organizational and technological solutions for managing the processes of building transport systems using economic and mathematical methods. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 63, 530–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschhorn, F.; Veeneman, W.; van de Velde, D. Organisation and performance of public transport: A systematic cross-case comparison of metropolitan areas in Europe, Australia, and Canada. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2019, 124, 419–432. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, K.; Pels, E.; Wu, J. Railway deregulation in the west and east: The impacts of organizational structure patterns on air-HSR competition. Transp. Res. Part B 2025, 200, 103304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeru, S. Organisational structures of urban public transport—A diagrammatic comparison of typology. J. East. Soc. Transp. Stud. 2011, 9, 126–141. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger-Trayner, E.; Wenger-Trayner, B. An Introduction to Communities of Practice: A Brief Overview of the Concept and Its Uses. 2015. Available online: https://www.wenger-trayner.com/introduction-to-communities-of-practice (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- ATM Group. Company Overview. 2023. Available online: https://atminternational.com/sites/default/files/2023-02/ATM_Company%20Overview_ENG_link.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Metro de Madrid (n.d.) Metro in Figures. Available online: https://www.metromadrid.es/en/who-we-are/metro-in-figures (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Metropolitan Sofia (n.d.) General Information. Available online: https://www.metropolitan.bg/en/index/general-information (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- MTR Corporation. Business Overview. 2024. Available online: https://www.mtr.com.hk/archive/corporate/en/publications/images/business_overview_e.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Münchner Verkehrsgesellschaft mbH (MVG). Mobility in Munich: Facts and Figures 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.mvg.de/dam/jcr:b6c038df-5953-4406-81ce-abadc420b133/MVG_Flyer_MVG_in_Zahlen_2024_EN_webansicht.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Tomov, S.; Dimitrova, E. Station Passenger Barrier Systems and Their Impact on Metro Transport Services. Eng. Proc. 2024, 70, 56. [Google Scholar]

- NEXUS: Next-Gen Technologies for Enhanced Metro Operations. 2025. Available online: https://nexus-heproject.eu/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

| Type of Structure: | Detail: |

|---|---|

| Multi-Layered/Hierarchical | The typical structure seen in transport operators, also known as a hierarchical structure. Many levels of management are between the top and bottom of the structure. Suggested as a necessary structure for transport expansion [7]. |

| Flat Structure | The organisation is split into a larger number of departments with respective managers at the head of each. Departments almost act as separate entities as they are separate from each other. Consequently, this compartmentalisation restricts collaboration and cooperation, reducing the organisation’s flexibility [8]. |

| Centralised | A centralised model is when decisions is made at an executive level exclusively; from a governance perspective, this can mean that an operator is owned and operated by the state. There are advantages and disadvantages of a centralised model, for example, rapid growth of infrastructure and network can be facilitated by a centralised organisation; however, this model has inefficiencies and fails to adapt to competition from other modes [15]. |

| De-Centralised | Alternatively, a de-centralised model, whereby decisions are made at various levels, can promote efficiency and a more market-driven approach, as governance may be private companies [18]. |

| Hybrid Models | By taking a pragmatic and flexible approach to an organisational structure, combining elements of various other organisational structures is needed. Hybrid models can enhance flexibility and collaboration within an organisation, therefore potentially producing the best outcomes in public transport governance [13]. |

| Operator | Geographical Location | Scale | Grades of Automation (GoA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MetroS—Metro Sofia (Bulgaria) | East Europe | 75 km/4 Lines | GoA1 and GoA3 |

| Metro de Madrid—Madrid (Spain) | Southwest Europe | 296.6 km/13 Lines | GoA2 |

| ATM—Metro Milan (Italy) | Southwest Europe | 111.8 km/5 Lines | GoA2 and GoA4 |

| MVG—Munich (Germany) | Central Europe | 95 km/8 Lines | GoA2 |

| SkyTrain—Vancouver (Canada) | North America | 79.6 km/3 Lines | GoA4 |

| MTR—Hong Kong (China) | East Asia | 245.3 km/11 Lines | GoA2 and GoA4 |

| Tokyo Metro—Tokyo (Japan) | East Asia | 195 km/9 Lines | GoA2 |

| TfL—London (UK) | Western Europe | 402 km/11 Lines | GoA1, GoA2, and GoA3 (DLR) |

| Keolis-MHI—Dubai (UAE) | Middle—East Asia | 89.6 km/2 Lines | GoA4 |

| Wiener Linien—Vienna (Austria) | Austria, East Europe | 83.9 km/5 Lines | GoA1, GoA2, and GoA4 (Future) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bannon, P.; Marinov, M.; Tong, H.Y. A Qualitative Assessment of Metro Operators’ Internal Operations and Organisational Settings. Sustainability 2026, 18, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010020

Bannon P, Marinov M, Tong HY. A Qualitative Assessment of Metro Operators’ Internal Operations and Organisational Settings. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010020

Chicago/Turabian StyleBannon, Patrick, Marin Marinov, and Hing Yan Tong. 2026. "A Qualitative Assessment of Metro Operators’ Internal Operations and Organisational Settings" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010020

APA StyleBannon, P., Marinov, M., & Tong, H. Y. (2026). A Qualitative Assessment of Metro Operators’ Internal Operations and Organisational Settings. Sustainability, 18(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010020