Abstract

Land degradation in drylands increasingly threatens infrastructure and the performance of renewable energy (RE) systems through coupled hydro-chemo-mechanical changes in soil fabric, density, matric suction, and pore–water chemistry. A key gap is the limited integration of unsaturated soil mechanics with practical indicator sets used in engineering screening and operations. This narrative review synthesizes evidence from targeted searches of Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. Searches are complemented by key organizational reports and standards, as well as citation tracking. Priority is given to sources that report mechanisms linked to measurable indicators, thresholds, tests, or models relevant to dryland infrastructure. The synthesis uses the soil-water characteristic curve (SWCC) and hydraulic conductivity k(θ) to connect hydraulic state to strength and deformation and couples these with chemical indices, including electrical conductivity (EC), exchangeable sodium percentage (ESP), and sodium adsorption ratio (SAR). Practical diagnostics include the dynamic cone penetrometer (DCP) and California Bearing Ratio (CBR) tests, infiltration and crust-strength tests, monitoring with unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), geophysics, and in situ moisture and suction sensing. The contribution is an indicator-driven, practice-oriented framework linking mechanisms, monitoring, and mitigation for photovoltaic (PV), concentrating solar power (CSP), wind, transmission, and well-pad corridors. This framework is implemented by consistently linking unsaturated soil state (SWCC, k(θ), and matric suction) to degradation processes, measurable indicator/test sets, and trigger-based interventions across the review.

1. Introduction

Land degradation, the gradual decline of a soil’s physical, chemical, and biological quality, threatens infrastructure performance, renewable energy (RE) deployment, public health, and water resources [1,2,3]. Desertification affects a significant fraction of Earth’s land surface, and drylands are particularly sensitive to climate forcing and land disturbance because near-surface soil structure can change rapidly [4].

Drylands (hyper-arid, arid, semi-arid, and dry sub-humid regions) cover a large share of the global land area and support about 3 billion people, with projections indicating continued population growth in these environments [5,6]. Land degradation is widespread and accelerating. Global assessments report that up to 40% of land is degraded, with impacts on billions of people and significant economic losses [2]. Within drylands, observed desertification has occurred over recent decades, and climate change is expected to amplify drought and heat extremes while aridity zones expand [5,6]. These combined trends increase risks of erosion, dust emission, salinization, and ground instability, and they place expanding infrastructure and RE developments in drylands under growing operational and reliability pressures [6,7].

Recent studies show that dryland degradation is strongly governed by unsaturated-soil behavior and measurable indicators. The soil-water characteristic curve (SWCC) and matric suction control suction-dependent strength and hydraulic conductivity k(θ). Wetting and warming reduce suction and can lower near-surface stability [8,9,10]. Surface sealing and physical crusting reduce infiltration and increase runoff. At the same time, wind erosion depends on the threshold friction velocity (ut), which rises with moisture and roughness but decreases as surfaces dry and vegetation declines, thereby increasing dust emission [11,12]. Chemical indicators, including electrical conductivity (EC), exchangeable sodium percentage (ESP), and sodium adsorption ratio (SAR), are widely used to diagnose dispersion risk. High sodium promotes clay dispersion, reduced permeability, and crusting, whereas salinity tends to maintain flocculation [13]. These mechanisms translate directly to infrastructure and RE performance, including photovoltaic (PV) soiling losses in dusty arid regions and stability/corrosion issues in saline sabkha soils [14]. International assessments (IPCC/IPBES) establish global-scale trends and urgency, but the mechanistic linkage to indicator-based engineering decisions remains fragmented [2].

Although land degradation is often described at the landscape scale, many of its engineering-relevant symptoms originate from changes in near-surface soil-state variables, including fabric, cementation, density, suction, and pore–water chemistry, which control detachment, strength loss, and deformation. Thus, a geotechnical perspective is crucial because many symptoms of dryland degradation, such as dust emission, rutting, crust failure, and settlement, are influenced by the near-surface soil’s fabric, density, suction, and cementation. Particle-size distribution and Atterberg limits offer quick screening tools for erodibility, dispersivity, and shrink–swell or collapse susceptibility. This review, therefore, considers land degradation as a coupled hydrological, chemical, and mechanical problem, in which observable impacts can be linked to measurable soil properties. Similar hydro-chemo-mechanical degradation pathways also occur in disturbed mining landscapes and corridors, where altered hydrologic regimes, salinity-driven weakening, and settlement can affect ground performance [15,16].

The rapid expansion of RE infrastructure underscores the urgency of managing dryland degradation. Utility-scale PV and CSP installations are sensitive to dust emissions and soiling, which can cause substantial energy losses in arid settings. Site disturbance (grading, traffic, and maintenance) can break crusts and mobilize fines, increasing dust supply and maintenance demand. Similar degradation mechanisms affect wind farms, transmission corridors, and well pads through rutting of access roads, erosion around foundations, settlement on collapsible soils, and corrosion risks in saline terrains. A geotechnical screening approach using indicators such as CBR/DCP, crust strength, and EC/ESP/SAR helps identify susceptibility and prioritize controls.

Despite extensive research on desertification, dryland management, and unsaturated soil behavior, current reviews usually address degradation processes, indicators, and infrastructure impacts separately. A significant gap thus remains in developing a unified, indicator-based framework that translates hydro-chemo-mechanical mechanisms into practical tools for screening, monitoring, and decision-making for dryland infrastructure and RE assets. This review focuses on three questions: (i) which soil-state variables (fabric, suction, density, pore–water chemistry) influence key dryland degradation mechanisms; (ii) which measurable indicators and thresholds most effectively identify susceptibility and support monitoring; and (iii) how these indicators can be connected to practical interventions and operation and maintenance (O&M) triggers. The emphasis is on diagnostic tests and monitoring variables that can support risk-based planning and operations for infrastructure and RE assets.

This review is structured to move from mechanisms to practice. Section 2 defines the scope and introduces a conceptual pathway that connects key drivers to soil state, degradation processes, indicators, and ultimately interventions. Following this, Section 3 outlines the key coupled processes involving hydrology, chemistry, and mechanics in drylands and highlights practical geotechnical indicators and thresholds, while Section 4 explores monitoring and modelling tools (field/lab tests, geophysics, remote sensing, and risk methods) that translate mechanisms into decision variables. Section 5 maps these mechanisms to RE and corridor assets (PV/CSP, wind, transmission, sabkha, and well pads). Section 6 summarizes mitigation options and the soil conditions under which they are most effective. Section 7 compiles indicator ranges and standards to support screening and trigger-based O&M, followed by concise conclusions in Section 8.

2. Scope, Conceptual Framework, and Sustainability Context

2.1. Review Scope and Methodology

This review focuses on land degradation in drylands and in infrastructure corridors, including roads, RE facilities, transmission lines, substations, and well pads. The emphasis is on near-surface processes that control subgrade performance, dust emission, erosion, settlement, and corrosion risks under arid and semi-arid conditions.

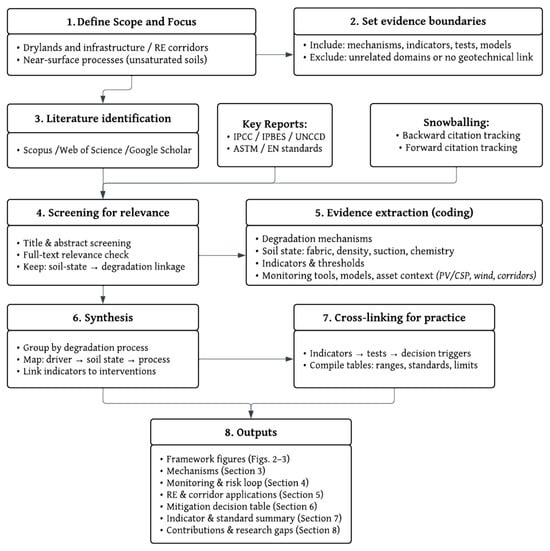

The literature was identified through targeted searches of major academic databases (e.g., Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar) and key organizational reports. Search strings combined terms for (i) drylands and degradation (e.g., dryland, desertification, wind erosion, crusting, salinization), (ii) unsaturated soil mechanics (SWCC, matric suction, hydraulic conductivity function, van Genuchten), (iii) geochemical indicators (EC, ESP, SAR, sabkha), and (iv) infrastructure and RE assets (PV soiling, CSP, wind farm, access roads, transmission corridor). Studies were screened for relevance to geotechnical mechanisms, measurable indicators, and applicability to dryland infrastructure. The selected literature was then synthesized by grouping evidence by degradation process and mapping each process to indicators, thresholds, monitoring tools, and mitigation options. Priority was given to studies that reported measurable thresholds, test methods, or constitutive relations linking soil state to degradation outcomes, particularly in arid or semi-arid settings. Figure 1 summarizes the narrative review workflow and synthesis pathway.

Figure 1.

Narrative review workflow from evidence identification and screening to coding and synthesis of mechanisms, indicators, and practice-oriented outputs.

Targeted, theme-based searches were conducted in Scopus, Web of Science Core Collection, and Google Scholar (screening approximately the first 300 results per query), supplemented by key organizational reports/standards and backward/forward citation tracking. Searches yielded approximately 5280 records. Deduplication reduced this to 1250 unique items. Title/abstract screening retained approximately 625 records, and full-text screening retained roughly 344 sources with usable mechanistic content (mechanism–indicator/threshold/test/model linkage). Snowballing added 15 additional sources. In total, around 180 sources (≈155 journal articles and ≈25 reports/standards) were prioritized for synthesis. As this is a narrative review with iterative searching, these counts are approximate because search queries overlapped, and deduplication was applied across databases.

Included sources were coded by (i) degradation type (e.g., water erosion/crusting, wind erosion/dust emission, salinity–sodicity, collapse/shrink–swell, internal erosion, subsidence), (ii) controlling soil-state variables (fabric, density, SWCC, suction, k(θ), and pore–water chemistry), and (iii) the reported indicators/tests/models and their threshold ranges. Evidence from the studies was compared within each degradation type to identify consistent indicator ranges, dominant controls, and areas of disagreement. These coded results were then mapped to relevant asset contexts (PV/CSP, wind, corridors, and sabkha/well pads) and to corresponding mitigation options, informing the summary tables and the trigger-style framework presented in Section 3, Section 4, Section 5, Section 6 and Section 7.

Key Unsaturated-Soil Relationships

This narrative review does not introduce new constitutive formulations; however, it frequently refers to standard unsaturated-soil relationships to define indicators and interpret mechanisms. Matric suction is defined as , where and are pore–air and pore–water pressures [17]. The SWCC is commonly represented using the van Genuchten form [18],

where is volumetric water content, and are saturated and residual water contents, and are fitting parameters [18]. Unsaturated hydraulic conductivity is often estimated using the Mualem–van Genuchten approach [18,19], with

where is saturated conductivity, is effective saturation, and is a pore–connectivity parameter [18,19]. A common shear-strength form for unsaturated soils is [20]

highlighting suction-dependent strength through [20]. References to hydro-mechanical models (e.g., BBM) in this review are intended to indicate established coupling frameworks rather than to present complete constitutive derivations.

2.2. Nexus and Conceptual Framework

Land degradation in drylands is closely tied to climate resilience and the land, water, and energy nexus. International assessments (e.g., IPBES, IPCC, UNCCD) highlight rising exposure to drought, vegetation loss, dust storms, and desertification under climate variability and land disturbance [21]. As soils degrade, water storage typically declines and runoff increases, intensifying erosion in disturbed corridors and affecting infrastructure and RE performance through higher dust emissions (PV/CSP losses and air-quality/visibility impacts) and greater risks of rutting and subsidence [14].

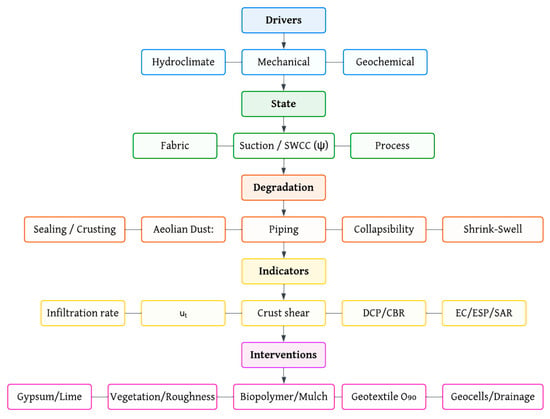

A geotechnical perspective is essential because most corridor soils are unsaturated, and moisture and suction changes control seepage, strength, stiffness, and volume change. Figure 2 summarizes the pathway from drivers (climate, land use, traffic, drainage, and water management) to soil state (SWCC, k(θ), matric suction, and salinity/sodicity), and then to degradation processes and indicator-based triggers. Quantitatively, the framework interprets degradation as the exceedance of a threshold. Runoff and rilling are likely when rainfall intensity exceeds the measured infiltration capacity, and rutting susceptibility increases when moisture-driven weakening results in low CBR or high DCP penetration indices. Dispersion and crusting risk increase with elevated SAR and ESP (interpreted alongside EC), while aeolian instability is expected when wind forcing exceeds uₜ.

Figure 2.

Geotechnical pathway illustrating how environmental and mechanical drivers influence soil state, trigger degradation, and guide diagnostic indicators and interventions.

3. Geotechnical Controls on Land Degradation in Drylands

3.1. Soil Fabric and Basic Index Properties

Particle size distribution (PSD) and grading significantly influence the hydraulic conductivity and erodibility of soils. Well-graded mixtures generally exhibit better resistance to detachment than poorly graded sands or silts [22]. Finer textures have higher specific surface areas and stronger interparticle forces; however, the overall response is heavily affected by fabric and bonding [23]. Carbonate or gypsum cementation can glue loose particles into fragile aggregates that disintegrate when wet or desalinated. Soluble salts or evaporite crystals may give the appearance of cohesion, masking their low inherent strength [24,25]. Index parameters such as void ratio (e), degree of saturation (S), liquid limit (LL), plastic limit (PL), and plasticity index (PI) serve as practical indicators. They help screen for shrink–swell potential, collapsibility, and dispersivity [23]. Laboratory studies indicate that Atterberg limits depend on clay mineralogy and microstructure. Clays high in montmorillonite have higher liquid and plastic limits and are more likely to undergo volume change [23,24]. Although these indices are useful screening tools, the microstructure size and arrangement of aggregates, double layers, and cementation bonds often determine susceptibility to erosion and deformation, highlighting the importance of interpreting simple thresholds within a fabric-based context.

3.2. Hydroclimate, Soil Water Retention, and Hydraulic Conductivity

Beyond fabric and index properties, hydroclimatic forcing influences water infiltration, suction, and hydraulic gradients, which drive detachment, transport, and volume change [26]. The permeability of unsaturated soils is highly nonlinear with respect to volumetric water content. Unsaturated hydraulic conductivity k(θ) can vary by 3 to 5 orders of magnitude as the soil wets or dries [27,28]. This sensitivity means that infiltration capacity, and thus the division between infiltration and runoff, is controlled by antecedent moisture, rainfall intensity, and soil structure [29]. In cohesive soils, infiltration is most efficient when rainfall intensity remains below the soil’s infiltration capacity. Intense storms that exceed this capacity generate surface runoff and increase shear stress. SWCCs describe the relationship between matric suction and water content, typically exhibiting hysteresis between drying and wetting paths. They are commonly represented using parametric models such as the van Genuchten or Brooks & Corey models [30]. During extended dry periods, suction and apparent cohesion rise, making aggregates resistant to detachment. Subsequent heavy rainfall can rapidly reduce suction, leading to slaking, dispersion, and micro-piping [31]. Repeated drying-wetting cycles not only alter suction but also cause hysteretic changes in strength and stiffness [32], which are critical when assessing thresholds for collapse, erosion, and dust emission.

3.3. Mechanical Loading, Traffic, and Rutting

In addition to hydroclimatic forcing, mechanical loading associated with land use interacts with hydrological states. Traffic on unsaturated subgrades induces stress paths that traverse both wet and dry regimes, and the resulting stiffness (often measured by the resilient modulus, Mr) depends on suction and saturation levels [31]. Field and laboratory studies indicate that severe pavement damage, including rutting and cracking, is caused by seasonal fluctuations in subgrade modulus resulting from changes in moisture and suction [33]. In compacted subgrade soils, the resilient modulus increases as saturation decreases to approximately 75%, and matric suction rises to around 800 kPa [34]. However, further drying reduces stiffness [34]. Small increases in matric suction can significantly improve bearing capacity and reduce settlement [35]. At the same time, wetting cycles after dry compaction can cause volume changes and shear deformation, leading to rutting under traffic [36]. Seasonal moisture cycles in fine-grained soils lower the resilient modulus, especially during initial wetting and freeze–thaw periods [32]. These findings support a mechanistic design that accounts for suction and moisture history rather than relying solely on unsoaked CBR values.

3.4. Salinity, Sodicity, and Salt Weathering

Geochemical processes further influence soil behavior by changing interparticle forces and cementation. EC, ESP, and SAR are measures of salinity and sodicity. In sodic soils, hydration of Na+ ions separates clay sheets; when repulsive forces surpass attractive forces, the clay structure disperses, causing particles to detach and collapse. Sodium-induced swelling reduces pore size and saturated hydraulic conductivity while increasing Atterberg limits and reducing trafficability [37]. Conversely, high salinity encourages clay particle flocculation by compressing the diffuse double layer. Elevated electrolyte levels improve aggregate stability and oppose dispersion [38]. Therefore, salinity and sodicity can have opposing effects on soil fabric, permeability, and erodibility, making it essential to consider EC and SAR together in management [38]. Salt weathering is another degradation process: soluble sulfates and chlorides crystallize within pores, exerting expansive pressure that breaks down soil or rock [39]. These processes are not limited to coastal areas. In arid sabkha environments, high ionic strength and evaporites impart apparent cohesion. However, wetting dissolves these salt bonds, leading to rapid settlement and loss of strength [24,25].

3.5. Surface Water Erosion, Sealing, and Crusting

Water erosion typically progresses through a sequence of linked processes. It begins with raindrop impact (splash), which detaches particles and breaks weak aggregates [40]. Detachment is amplified when wetting causes slaking and dispersion, generating fine particles that can migrate into surface pores. This produces surface sealing, in which a thin, low-permeability layer forms, sharply reducing infiltration [41].

As sealing intensifies, rainfall more readily exceeds infiltration capacity, increasing overland flow and promoting sheet and rill erosion. When flow concentrates, shear stresses can exceed the soil’s critical shear strength, driving rill incision and, with continued concentration, gully development [40,42]. The thresholds controlling this escalation depend on soil state. Detachment is favored when soils are moist, dispersive, or low in cohesion, while positive suction and aggregate stability increase resistance to erosion [42,43,44].

3.6. Wind Erosion and Dust Emission

3.6.1. Threshold Friction Velocity and Controls

Building on the hydro-chemo-mechanical processes described in Section 3.1, Section 3.2, Section 3.3, Section 3.4 and Section 3.5, this subsection focuses on aeolian transport and dust emission, as they directly control air quality and soiling at RE sites. Wind erosion is an inherently geotechnical phenomenon governed by the interplay among soil state, surface condition, hydrologic history, and atmospheric forcing. Initiation of particle motion occurs when the aerodynamic shear stress on the surface exceeds the resisting forces arising from gravity, interparticle bonding, and capillary suction. The corresponding ut (shear velocity at which erosion begins) serves as a convenient descriptor of soil stability [45]. Particles larger than 0.84 mm are non-erodible because gravitational forces exceed aerodynamic drag [46].

In contrast, very fine particles (<0.025 mm) and coarse sands (>1.0 mm) are resistant due to cohesive and gravitational forces, respectively. However, wind-tunnel studies indicate that the minimum ut occurs for particles around 60–120 µm (reported literature range; see [47,48]). Because most soils contain particles in this range, variations in are primarily controlled by surface roughness rather than grain size [45]. Aerodynamic roughness height is the central control on u₍t₎ in loose or disturbed soils, with gravelly surfaces exceeding 1 m/s and smooth soils showing much lower thresholds [47]. Field and wind-tunnel studies show that wind erosion is favored when the soil is loose, dry, and finely divided. It is also promoted when the surface is smooth and bare and when the field is broad and unsheltered [49]. Moisture exerts a dual control. Small amounts of water increase cohesion through capillary and van der Waals forces, raising , whereas extended dry periods reduce suction, weaken crusts, and make fine particles available for entrainment. Threshold friction velocities increase by roughly 20–220% (reported range across studies/conditions; see [50]) when the gravimetric water content rises from 1.2% to 16.4% compared with oven-dry soils [50]. Cyanobacterial and lichen crusts bind particles with extracellular polymers, forming cohesive mats [50]. These mats can raise severalfold from about 0.3 to 0.7–0.8 m/s for thin crusts and up to an order of magnitude for thick ones [50]. Field data show ≈ 2.1 m/s on intact or chemically killed crusts but only ~0.9 m/s after mechanical removal, confirming their strong stabilizing role [51]. Wind-tunnel measurements also show that as the fetch (distance over which wind acts) increases, sediment flux and shear stress evolve. After about 2 m of fetch, sediment flux tends to stabilize while shear stress drops to roughly 78% of the entrainment threshold [52]. Beyond ~4–5 m, the saltation frequency decreases, indicating fully developed transport [52]. This “fetch effect” reflects aerodynamic feedback and progressive crust or aggregate breakdown along the surface, which lowers resistance and enhances sediment mobility [52]. Threshold friction velocities in sandy desert soils lacking microphytic crusts can be as low as 0.2–0.6 m/s [51], whereas rain crusts on sandy loam reach around 2.9 m/s [51]. Microphytic crusts bind soil particles into coherent mats and maintain ut even after biological death. Mechanical removal of the crust reduces ut and triggers erosion at significantly lower wind speeds. Thus, the strength of biological and physical crusts, grain size and aggregation, surface roughness elements (rocks, clods, crop residues), and fetch length collectively determine ut and, therefore, the onset of aeolian transport.

3.6.2. Roughness, Vegetation, and Drag Partitioning

Surface roughness and vegetation influence aeolian transport through drag partitioning and sheltering effects [53]. Non-erodible elements such as clods, rocks, and standing crop residues absorb part of the wind shear, reducing the stress on erodible particles [54]. Wind-tunnel experiments with arrays of cylinders and spheres show that the critical friction velocity ratio (total friction velocity divided by the ut of erodible particles) increases with the ratio and the silhouette area fraction of roughness elements [55]. As erosion removes loose soil, the surface becomes progressively armored by coarse fragments and non-erodible residues, which further raise the barrier until the intervening shear drops below the threshold and transport stops [55]. Vegetation acts similarly: plant stems and litter reduce wind energy, create turbulent wakes, and trap saltating grains, shifting erosion from transport-limited to supply-limited regimes [53]. The protective effectiveness depends on the density, spacing, and height of the roughness elements, as well as the size and cohesiveness of soil aggregates [55].

3.6.3. Air Quality, Visibility, and Renewable Energy Impacts

Dust emissions affect air quality and visibility because fine particles, particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter <10 μm (PM10) and <2.5 μm (PM2.5), are readily transported and inhaled. In actively eroding fields, the mass median diameter of suspension-borne particles is approximately 50 µm [56]. However, fragmentation of saltating and creep-sized aggregates produces additional fines. Clay soils often form sand-sized aggregates (parna) that release respirable dust when abraded. Health and visibility concerns are therefore tied to particle-size distribution, aggregation state, and the intensity of saltation impacts. These metrics guide land managers in prioritizing crust protection, vegetation maintenance, and roughness enhancement.

The aeolian environment directly impacts RE infrastructure. Dust entrainment and deposition on PV panels and CSP mirrors decrease optical efficiency. Long-term monitoring in arid regions reports average daily PV power losses of approximately 4.4% in Malaga, Spain, with losses exceeding 20% during extended dry periods [57]. Monthly power losses of 6.9% were observed on sandy soils in southern Italy compared to 1.1% on compact soils [14]. Wind-blown sand can wear down turbine blades, track systems, and heliostat gearboxes, while access roads and maintenance areas become local sources of dust when disturbed. Therefore, RE developers need to consider soil texture, crust stability, vegetation cover, and road design when locating and operating facilities in windy, dry environments.

3.7. Subsurface Instabilities

Internal erosion occurs when soil particles are displaced due to seepage flow [58]. Mechanisms include the suffusion of fines through a coarser matrix, contact erosion at interfaces, and backward erosion piping [59]. Piping occurs when focused leak erosion forms a continuous tunnel between the upstream and downstream sides of an embankment, eventually leading to a breach [59]. Internal erosion typically occurs through stages of initiation, continuation, progression, and failure, each influenced by hydraulic gradients, stress redistribution, and fabric. Dispersive clays with high SAR are particularly susceptible to piping because colloidal particles can easily detach and migrate [59].

Collapsible soils pose an additional hidden risk. These soils, often young alluvial, aeolian, or loessial deposits found in arid areas, have low dry density and open, metastable structures held together by clay, carbonate, or salt bonds. When they become wet, these bonding agents weaken, causing the structure to collapse and leading to rapid settlement and damage to foundations, pavements, and utilities [60]. The potential for collapse increases with higher dry density, the natural water content compared to the liquid limit, and the applied load [61]. Quick assessments can be made using screening ratios such as w/LL or by comparing dry density to maximum density [61]. Proper site investigation, moisture control, and ground improvement are crucial in mitigating this risk. Shrink–swell behavior results from certain clay minerals, especially smectite, absorbing water into their interlayer spaces, which causes volume expansion when wet and contraction when dry. These soils are typical and can cause significant damage. Swell pressures can reach several hundred kilopascals, and swelling strains may exceed 10% [62]. Shrinkage creates deep cracks that increase permeability, providing pathways for fluid flow, and, once dried, produces loose dust that the wind can blow away. The extent of shrink–swell behavior depends on mineralogy, exchangeable cations, and stress levels. Sodium-rich clays tend to swell more and disperse more easily. Importantly, shrink–swell cycles interact with mechanical loads, causing heave and settlement that can impact pavements, pipelines, and RE pad structures.

Dispersive soils, characterized by high sodium levels in pore water, undergo deflocculation when exposed to low-salt water and are easily eroded by runoff. These clays typically fall into low- to medium-plasticity classes (CL, ML) and have a high potential for swell–shrink [63]. Sodium ions increase the repulsive forces between clay particles, causing them to disperse and migrate through seepage paths [64]. Exchangeable calcium and magnesium, on the other hand, promote flocculation and reduce dispersion [65]. Dispersive soils are susceptible to both surface and internal erosion, making accurate identification crucial for effective hazard management [64].

Subsidence completes the range of geotechnical degradation processes. Dewatering of compressible layers, dissolution of soluble minerals, and karstic collapse can cause significant, often sudden, settlements [66]. In sabkha environments, the dissolution of evaporite cement destroys the soil structure, leading to ground collapse [66]. Similarly, pumping groundwater from peat or clay deposits causes consolidation and surface subsidence. These processes are linked to the geochemical mechanisms discussed earlier because dissolution and leaching alter the fabric, weaken the material, and increase compressibility. The mechanistic pathways outlined above underscore the importance of integrating material properties with hydroclimatic, mechanical, and geochemical forces to predict and mitigate land degradation [66]. Table 1 summarizes each degradation process, its key geotechnical indicators, and the screening thresholds used in practice.

Table 1.

Geotechnical Degradation Processes and Their Key Indicators.

4. Monitoring and Modelling for Degradation and Risk

Field observations of uₜ, surface roughness, crust strength, and aggregate stability complement wind-tunnel measurements of soil flux and other erosion metrics. Emerging tools include unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) photogrammetry for quantifying microtopography, portable dust samplers, and networked particulate matter sensors. Models range from empirical formulations that relate soil loss to erodibility, roughness, climate, and fetch to physics-based representations of saltation, suspension, and runoff-driven erosion. The following subsections develop these monitoring and modelling approaches in more detail and explain how geotechnical indicators and process thresholds inform risk assessment and adaptive management.

4.1. Field and Laboratory Indicators of Degradation

The mechanistic picture developed in Section 2 and Section 3 becomes operational only when it is linked to measurements and models. This section, therefore, outlines monitoring tools and modelling approaches for quantifying degradation and risk. Field and laboratory tests are fundamental to operational geotechnical monitoring. DCP and CBR measurements are commonly used to evaluate subgrade rutting vulnerability because penetration resistance and bearing capacity are strongly influenced by moisture content [67]. Small increases in matric suction can significantly stiffen the near-surface and increase the modulus [68]. Cone penetration test (CPT) and standard penetration test (SPT) profiles offer higher-resolution stratigraphic information. They can identify loose, collapsible horizons or silty interlayers that are prone to piping and suffusion. Infiltration capacity and sealing susceptibility are assessed using single-ring or mini-disk infiltrometers. These tests measure the water entry rate under specific head conditions, directly translating into infiltration capacity used in runoff models [69]. Simple crust hand-shear tests, crumb/aggregate stability tests, and pinhole tests help differentiate between physical crusts, dispersive sodic crusts, and intact biological crusts. Oedometer tests along wetting paths quantify the potential for collapse and the swell pressure. Collapsible soils have meta-structures and can suddenly settle when wetting weakens interparticle bonds, whereas expansive clays exhibit heave and crack networks as suction decreases [70]. Laboratory index tests remain essential. Atterberg limits (liquid limit LL, plastic limit PL, and plasticity index PI) relate to shrink–swell potential, collapsibility, and dispersivity. Grain-size distribution and grading shape indicate associated risks of suffusion, erodibility, and wind-driven dust. Quick EC, ESP, and SAR tests reveal sodicity and salinity levels, which drive clay dispersion and salt weathering. Field programs should account for spatial variability and temporal changes. Conducting replicates across microtopographic positions, controlling moisture during sampling, and calibrating equipment help prevent misleading results and ensure accurate trend analysis. Table 2 links commonly used field/lab tests to the specific degradation risks they quantify at RE sites.

Table 2.

Linking Field Tests to Degradation Assessment for RE Sites.

4.2. Geophysical and Remote Sensing Tools

Geophysical and remote sensing methods extend these point measurements across landscapes. Electrical resistivity tomography (ERT) captures spatiotemporal variations in subsurface resistivity, which can be related to volumetric water content and the depth of wetting fronts through petrophysical relationships. Time-lapse ERT has been widely applied to map infiltration patterns, preferential flow, and shrink–swell cycles over scales of tens of meters [71]. Multichannel analysis of surface waves (MASW) and spectral analysis of surface waves (SASW) infer shear wave velocity profiles from seismic dispersion curves and are sensitive to stiffness contrasts associated with density, suction, and degree of saturation [72]. Ground-penetrating radar (GPR) exploits the dielectric contrast between wet and dry zones to delineate shallow utilities, cavities, and preferential flow paths. UAV photogrammetry and structure-from-motion (SfM) techniques produce centimeter-resolution digital elevation models that capture rill-gully networks, rut depths, and surface roughness. High-frequency repeat surveys enable volumetric change analysis, which is essential for erosion monitoring [73]. Normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) and surface albedo derived from multispectral imagery indicate vegetation cover and soil moisture status. Simultaneously, synthetic aperture radar coherence detects surface disturbance, roughness, and moisture changes [74]. Spatial resolution, penetration depth, and revisit frequency differ across these methods, and their uncertainties propagate into subsequent modeling. For this reason, ground control points, co-located moisture or suction sensors, and independent calibration are essential for reliable interpretation of remotely sensed data.

4.3. Monitoring Network Design and Telemetry

Effective monitoring design combines instrument selection with hydroclimatic forcing and land use. Because extremes of drying and wetting drive many degradation processes, monitoring frequency should increase during pre- and post-storm periods and after maintenance activities. Low-power dust sensors and miniature meteorological stations collocated with soil suction and moisture probes quantify wind erosion thresholds and dust emission windows [68], enabling correlation of dust episodes with soil moisture and crust strength. Modern deployments often employ wireless telemetry and solar power. These systems require attention to data latency, memory overflow, and environmental durability. Data management plans should define file formats, metadata, calibration checks, and procedures for replication to ensure long-term monitoring programs generate reproducible, comparable datasets.

4.4. Modelling Approaches for Degradation Processes

Modeling approaches range from simple screening indices to detailed physics-based simulations. Table 3 summarizes the main model families referred to in this review, highlighting their key parameters, strengths, limitations, and typical applications in RE and dryland contexts. RUSLE (Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation) and MMMF (Modified Morgan-Morgan-Finney) represent empirical and process-based models for water erosion, respectively. At the same time, WEPP (Water Erosion Prediction Project) is a physically based model for hillslopes and channels. VGM denotes the van Genuchten–Mualem formulation, in which α and n are curve-shape parameters, θₛ and θᵣ are the saturated and residual volumetric water contents, Ks is the saturated hydraulic conductivity, and l is a pore–connectivity factor. The “Richards + EBBM” entry refers to simulations that couple Richards’ equation for unsaturated flow with elasto-plastic bounding models for unsaturated soils (e.g., the Barcelona Basic Model, BBM) to capture wetting-induced collapse and rutting. The dust-emission row represents physically based schemes that resolve ut, surface roughness, vegetation cover, and moisture controls to assess soiling, visibility, and health impacts.

Table 3.

Key modelling approaches for dryland degradation.

Unsaturated seepage and heat transfer models rely on constitutive relations for the SWCC and hydraulic conductivity. Parametric models, such as the van Genuchten–Mualem model, describe how suction and conductivity vary with volumetric water content and can incorporate hysteresis via scanning curves [83]. Finite-element models of stress and deformation simulate rutting and bearing degradation under traffic loads by coupling suction-dependent shear strength with resilient modulus relationships. Internal erosion and suffusion risks are assessed through gradation and hydraulic gradient analysis. Seepage forces exceeding particle interlock resistance can lead to backward erosion or piping [84]. On larger scales, models for surface crusting and sealing consider raindrop impact energy, clay dispersion, and cyclic shrink–swell processes. Integrating hydraulic, mechanical, and chemical interactions is crucial because salinity and sodicity influence soil fabric and permeability, which in turn affect hydrologic response and stability.

4.5. Risk and Reliability-Based Assessment

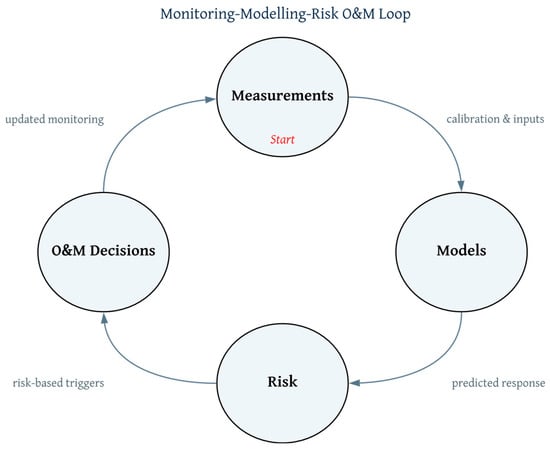

Risk and reliability analyses convert model outputs and monitoring data into engineering decisions. The probability of failure and the reliability index provide quantitative measures of the likelihood that degradation exceeds design limits [85]. For instance, rut depth distributions from repeated UAV surveys can be compared with allowable tolerances to calculate exceedance probabilities, while volumetric erosion estimates inform the risk of gully volume. Reliability methods account for variability in soil properties, hydrologic forcing, and model parameters, updating initial distributions as monitoring data are gathered. Trade-offs among risk reduction, carbon footprint, water use, and operation and maintenance (O&M) costs are examined by linking reliability results with economic and environmental metrics. Together, these steps form a monitoring–modelling–risk operations and maintenance (O&M) loop for degradation management, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Monitoring, modeling, and risk operations and maintenance (O&M) loop linking measurements, model calibration, and risk-based decision triggers for land degradation management.

Figure 3 illustrates this monitoring, modeling, and risk management loop for operations and maintenance (O&M). Field and laboratory measurements, remote sensing data, and geophysical surveys supply calibrated inputs to the hydro-chemo-mechanical and dust-emission models described in Section 4.1, Section 4.2, Section 4.3 and Section 4.4. Model outputs, such as predicted rut-depth distributions, collapse settlements, dust fluxes, and reliability indices, are then used to establish risk-based thresholds for inspection, cleaning, or reinforcement. Implementing these O&M actions generates new data that feeds back into the monitoring system, gradually decreasing uncertainty and sharpening site-specific thresholds for land degradation management.

5. Implications for Renewable Energy and Infrastructure Corridors

5.1. Overview of Renewable Energy and Linear Infrastructure Settings

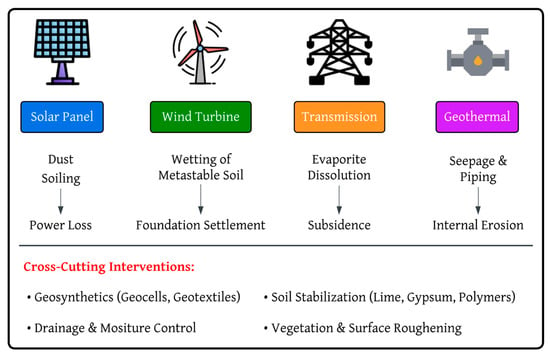

Having outlined how degradation processes operate and how they can be monitored and modelled, the next step is to examine how they manifest at specific RE projects. Rapid growth in RE infrastructure has introduced utility-scale solar PV and CSP arrays, onshore wind farms, transmission lines, substations, and geothermal well pads into landscapes where geotechnical degradation is already underway. These projects cover large areas in arid and semi-arid regions with soils that have low organic matter, weak structure, and high vulnerability to erosion and salinization. Unlike buildings that concentrate loads in small areas, RE projects spread loads across access roads, array pads, and linear trenches, subjecting them to hydro-chemo-mechanical forces over decades. Understanding how soil fabric, suction, SWCC, and state variables such as degree of saturation and void ratio, along with geochemistry (ESP, SAR), influence permeability, strength, and collapse is crucial for managing asset performance. The value of geotechnical insights lies in predicting where dust emission, rutting, piping, heaving, or settlement might reduce power output, increase maintenance costs, or threaten structural stability. Figure 4 maps these degradation pathways onto PV/CSP arrays, wind farms, transmission corridors, and geothermal pads, linking site conditions to expected failure modes and controls.

Figure 4.

Degradation Pathways for RE Infrastructure.

5.2. Solar PV and CSP Facilities

For solar PV and CSP facilities, dust emission and soiling losses are key performance factors. Dust supply depends on ut, which increases with moisture, crust strength, and roughness but decreases when biological or physical crusts are disturbed. Arrays influence local wind patterns and fetch lengths. Panel rows act as roughness elements that divide shear stress, but interrow areas can become supply-limited if crusts form. Conversely, maintenance traffic can break crusts and expose fines. Surface sealing and crusting, caused by raindrop impacts and clay dispersion, decrease infiltration and increase runoff. The impervious panels concentrate rainfall at row edges, promoting rill and gully formation and aggregate detachment when the shear stress exceeds the cohesive strength. Cable trenches backed with loose material may collapse when wetting weakens bonds or when compressive loads surpass compaction efforts. Collapsible soils in arid basins can settle substantially upon wetting [70]. Panel tilt and row spacing influence shading and exposure. Steeper tilts cast shadows that help retain moisture and strengthen crust, while dense spacing may trap saltating grains and promote dust redeposition. Routine O&M traffic compacts surfaces, decreasing macroporosity and infiltration, and can create ruts when soils are moist.

5.3. Onshore Wind Farms

Onshore wind farms show similar but mechanically different degradation paths. Turbine pads and access roads are built on silty or loessic slopes that are highly erodible when unprotected. Traffic compression reduces macropore networks, lowering infiltration and increasing runoff and erosion. Ruts form when vehicle loads are applied at intermediate water contents, where particle friction is reduced, and pores are not fully saturated. Rut depths of 50–100 mm or more can obstruct road access and increase blade delivery, and O&M costs [86]. Repeated wetting-drying cycles modify matric suction and disrupt the soil’s hydro-mechanical equilibrium. As suction decreases, shear strength and resilient modulus decline, leaving subgrades more susceptible to plastic deformation under cyclic loads [87]. Turbine pads become vulnerable to internal erosion and piping when drainage pathways concentrate seepage. When seepage forces exceed interparticle resistance, suffusion and contact erosion can occur, potentially leading to sinkholes or localized scour around foundations. Cable routes often cross expansive clay, where seasonal changes in suction cause heave and shrinkage. Swelling pressures can reach several hundred kilopascals, causing undulations along buried cables [88].

5.4. Transmission Corridors, Substations, and Geothermal Pads

Transmission corridors and substations, especially those crossing sabkha flats and coastal margins, face unique geochemical challenges. Sabkha soils are saline flats composed of loosely cemented sands, silts, and clays interbedded with evaporite minerals. They exhibit very low strength, low bearing capacity, and high compressibility. Chemical tests reveal high salt concentrations, creating a corrosive environment that dissolves the cement [89]. Evaporite dissolution from rainfall or groundwater flow weakens cementation, leading to settlement and uneven heaving. High ESP and SAR cause clay particle dispersion. The resulting swelling and dispersion lower hydraulic conductivity and raise the Atterberg limits, thereby decreasing rut resistance and complicating maintenance. In sabkha environments, capillary rise transports saline water toward the surface, where evaporative processes deposit salts and form a brittle crust. When this crust becomes wet, the salts dissolve, leading to collapse and fines pumping.

Geothermal well pads involve additional hydro-chemo-mechanical interactions. During drilling and production, well pads experience repeated wetting and drying from wellbore discharges and precipitation. These cycles modify matric suction and progressively weaken the soil structure. Traffic-induced compaction decreases infiltration and increases runoff; repeated loads on moist soils form ruts and smear surfaces, creating tillage pans that block drainage. Fines can migrate under seepage gradients, clogging pores and lowering permeability, while removing fines from base layers promotes settlement. Internal erosion or piping may happen if seepage paths develop beneath well pads. In cold climates, freeze–thaw cycles exacerbate these processes, whereas in arid areas, thermal contraction and salt crystallization cycles are more prevalent.

5.5. Performance, Economics, and Life-Cycle Sustainability

Degradation directly impacts the performance and economics of RE. PV soiling losses of a few percent can result in tens of thousands of dollars in annual energy shortfalls, while cleaning schedules depend on dust buildup and rain frequency [14,57]. Rutting beyond maintenance thresholds increases truck rolling resistance, fuel use, and component replacements. Settlements of pads and foundations can misalign arrays or turbines, raising mechanical stress and causing outages. On sabkha soils, differential settlement may exceed centimeters per year, requiring costly underpinning or reconstruction [90].

6. Sustainable Mitigation Strategies and Low-Carbon Design Options

Building on the use cases in Section 5, this section translates geotechnical descriptors and degradation pathways into practical design and operational interventions. Mitigation and design strategies for land degradation rely on translating geotechnical descriptors into interventions that change material states and boundary conditions. In arid and semi-arid environments, low water availability and high evapotranspiration increase suction fluctuations. Soil fabric, degree of saturation, density, and the chemistry of pore water determine how interventions should be adapted. Sustained unsaturated conditions promote aggregation and high shear strength, but once suction drops, these metastable structures can collapse or disperse [91]. Therefore, interventions must stabilize fabric, control suction through surface treatments or drainage, and modify mechanical loading. The objective is to keep soils within safe zones on the soil-water characteristic curve. To translate these mechanisms into practice, Table 4 summarizes common degradation problems, matched intervention options, and their governing mechanisms, facilitating quick selection and scoping.

Table 4.

Summary of Interventions for Common Degradation Issues (effectiveness is soil- and site-dependent; verification required).

6.1. Chemical and Organic Amendments

Source control measures begin with chemical and organic amendments that modify interparticle forces and pore–water chemistry. Lime treatment has long been used in road construction and embankment repair to reduce swelling and increase strength. The addition of 3–9% lime by weight decreases the plasticity index, linear shrinkage, and liquid limit of expansive clays, while increasing permeability and shear strength [92]. Field experience on interstate highways showed that lime reduced expansion from 41% to as low as 3.6% [93]. In sodic soils, gypsum provides a soluble calcium source that replaces sodium on the exchange complex, promoting flocculation [94]. Guidelines from Ohio State University note that gypsum amendments prevent dispersion and surface crusting, promote aggregate formation, and enhance water infiltration and percolation [94]. Such amendments also reduce erosion losses and mitigate subsoil acidity [94]. In coastal sabkha environments where high sulfate and chloride contents degrade bearing capacity, cement or lime alone may be inadequate, and sulfate-resisting cements, pozzolans, and corrosion inhibitors are recommended to protect concrete and reinforcement. Organic additions such as biochar or straw mulches increase surface roughness, enhance moisture retention, and improve aggregate stability [95]. Bio-based polymers and alginate products can form resilient crusts that resist raindrop impact yet rehydrate after rain [96], preserving infiltration capacity. The selection among these materials depends on the soil’s plasticity index, ESP, and the required treatment lifespan. Sandy loams often benefit from polymer binders, whereas dispersive clays typically respond more effectively to gypsum and moderate lime applications.

6.2. Vegetation, Surface Roughness, and Nature-Based Solutions

Vegetation establishment and surface roughening are complementary measures that harness biological processes to stabilize soils and reduce aeolian and water erosion. Standing vegetation and roughness elements serve as non-erodible obstacles that divide shear stress, raising the ut required for wind entrainment and decreasing saltation flux [97]. Seeding perennial grasses or shrubs can thus provide long-term dust control by forming a protective canopy and encouraging root reinforcement. Short-term covers, such as straw mulch or gravel, can also reduce raindrop impact and prevent sealing. However, they must be carefully selected to avoid excessive runoff or weed invasion. In RE facilities, vegetated strips between PV arrays and along access roads help reduce dust and intercept runoff. Windbreaks should be spaced based on their height, as adequate protection typically extends up to 10 times the height of the windbreak [97].

6.3. Geosynthetics, Geocells, and Structural Measures

Structural measures target concentrated flows, trafficking, and settlement by using engineered layers and drainage components. Nonwoven geotextiles serve as filters and separators between native soils and imported aggregates. The Fibertex technical guide highlights that an effective geotextile should have an opening size small enough to retain larger soil particles while still allowing finer, unstable particles to pass through, thereby allowing a natural granular filter to develop [98]. The characteristic opening size (O90) is matched to the grain size distribution, with typical geotextile openings ranging from 63 to 100 µm, accommodating most static and dynamic hydraulic conditions [98]. When soils are silty and a natural filter cannot form, adding a thin layer of sand between the soil and geotextile can boost permeability [98]. Geocells offer three-dimensional confinement of granular bases and are especially useful for access roads over weak subgrades [99]. A review of geocell-stabilized unpaved roads shows that geocells prevent slip surfaces, increase bearing capacity and modulus, improve stress distribution, and reduce permanent deformation under cyclic loads [99]. The same study notes that geocell-stabilized bases enhance apparent cohesion and lateral confinement, acting as a stiffened slab. For RE sites, Geocells manufactured from recycled tires provide durable confinement, reduce deformation of unpaved platforms, and contribute to sustainability by reusing difficult-to-manage waste materials [100]. Geotextile bags or gabions can function as check dams and slope stabilizers, while geogrids or geotextiles beneath PV pads help mitigate differential settlement. Compatibility of filters and hydraulic capacity should be validated using retention and permeability criteria, and the interface shear strength must be adequate for expected traffic loads.

6.4. Water and Salt Management

Water and salt management are essential for controlling collapsibility, dispersion, and erosion. Drainage systems must balance improving infiltration with the risk of piping or saturation. On high-salinity sabkha soils, the low bearing capacity and high compressibility require elevated pads, capillary breaks, and protected foundations. Drainage blankets under PV pads and wind turbine foundations should include free-draining sands with geotextile filters designed to prevent migration of fine particles. However, leaching must be carefully managed to avoid rapid dissolution of evaporites and subsequent subsidence. In sabkha or coastal areas, controlling the groundwater table and sealing the surface may be necessary to limit the capillary rise in saline water.

6.5. Design Ranges, Verification, and Low-Carbon Materials

Design ranges and verification reflect the variability of soils and the interaction between hydro-mechanical and chemical processes. For access roads, crowns or cambers of 2–4% promote drainage without causing lateral erosion; geocell layer depths typically range from 150 to 250 mm, but these values should be calibrated using plate load tests or DCP/CBR correlations [101]. Mulch should be applied at a thickness of 2–5 cm to provide groundcover and protect exposed soil surfaces [102]. Under filtration conditions, the geotextile’s hydraulic conductivity or permittivity should be at least an order of magnitude greater than that of the adjacent soil to avoid hydraulic impedance at the interface [103].

Low-carbon and resource-conscious choices aim to minimize life-cycle impacts while maintaining performance. Recycled aggregates from concrete or asphalt reduce the need for virgin materials and perform effectively when confined within geocells, provided their gradation complies with filter rules [104]. Waste-tire geocells and bio-based polymers offer alternatives to petroleum-based geosynthetics [100]. However, their durability under ultraviolet exposure and wet-dry cycling conditions should be further confirmed. Vegetation strips and mulches, although often overlooked in utility-scale solar and wind sites, provide ecosystem benefits such as dust suppression and carbon sequestration [54]. Decisions should consider factors such as carbon footprint, water usage for establishment and maintenance, and resilience to extreme events.

7. Indicators, Standards, and Policy-Relevant Metrics

7.1. Practical Indicators and Thresholds for Sustainable Land Management

The preceding sections have treated mechanisms, monitoring, applications, and interventions in turn. This section synthesizes these strands into a set of indicators, standards, and strategic priorities for practice. Practical experience and the cases discussed highlight the importance of consistent indicators and standards in linking geotechnical insights to land degradation assessment and asset management. Agencies and RE developers can formalize a set of reporting elements. Examples include crust shear strength classes (derived from simple hand shear tests), double-ring infiltrometer rates (ASTM D3385 [105]), DCP penetration indices linked to CBR, and UAV-derived measurements of rut and gully volume. Maps of EC, ESP, and SAR help identify priority treatment areas. Standardized test methods, such as ASTM D6951 [106] for the DCP, ASTM D1883 [107] for the CBR, ASTM D3385 [105] for infiltration, and EN ISO 12956 [108] for geotextile opening size, ensure consistency in procurement specifications and acceptance criteria. For example, infiltration rates below a set threshold can trigger scarification and amendments. DCP indices exceeding rutting limits prompt base reinforcement, and high EC readings at substations trigger gypsum application and drainage adjustments. Aligning data collection with recognized standards ensures comparable results across projects, supporting regulatory reporting and environmental compliance. Table 5 provides quick-look screening ranges and notes that support specification checks and trigger-based O&M decisions.

Table 5.

Quick Look Thresholds and Useful Ranges (for screening and acceptance).

7.2. Strategic Outlook, Policy Implications, and Research Gaps

A geotechnical perspective in design and land degradation management provides a pathway to building defensible, resilient infrastructure against climatic extremes and expanding RE development. By basing interventions on material descriptors, hydro-chemo-mechanical forcings, and process thresholds, practitioners can trace observable symptoms back to their causes and choose treatments with clear reasoning. Monitoring tools, ranging from handheld penetrometers to UAVs and automated dust sensors, provide data to models that span from simple empirical indices to physics-based analyses. These models can then be integrated with reliability frameworks to express the probability of failure and the reliability index. This integration enables decision-makers to convert measurements into risk-based inspection intervals and maintenance strategies. As RE infrastructure expands into sensitive landscapes, adopting geotechnical indicators and standards will be crucial for anticipating and mitigating degradation, ensuring that energy generation, infrastructure durability, and environmental protection remain aligned.

Reported mechanisms and threshold values are not entirely consistent across the literature. Collapsible loess, for example, exhibits a wide range of collapse strains depending on cementation, density, stress level, and wetting path, and the influence of salinity on hydraulic conductivity varies. High electrolyte concentrations may promote flocculation, while sodicity-driven dispersion reduces permeability. Accordingly, the screening ranges summarized in this review should be interpreted as conditional values and refined through site-specific testing and monitoring.

8. Conclusions

A key insight from this review is that diverse dryland degradation modes can be interpreted through a shared set of unsaturated soil state variables and indicator-based thresholds, rather than treated as isolated phenomena. By explicitly linking mechanisms to indicator/test sets and trigger-style interventions, the review converts dispersed evidence into a decision-oriented framework for screening, monitoring design, and risk-based O&M for infrastructure and RE assets. This review has shown that land degradation in drylands is a geotechnical challenge influenced by soil fabric, suction, density, and their hydro-chemo-mechanical interactions. Using the SWCC to connect water content, suction, hydraulic conductivity, and strength provides a unified approach. It helps in understanding erosion, sealing and crusting, internal erosion and piping, collapsibility, shrink–swell behavior, salt weathering, and subsidence through specific process thresholds.

A monitoring-led operations and maintenance loop is essential. Basic field and laboratory tests (e.g., DCP/CBR, infiltration, crust strength, EC/ESP/SAR, Atterberg limits, collapse and swell tests) should be combined with UAV photogrammetry and in situ moisture and suction sensing, then analyzed with reliability methods to enable timely maintenance.

RE examples illustrate how this framework connects mechanisms to performance. They encompass protection of the crust and runoff management for PV and CSP installations, as well as moisture-resistant bases and improved drainage for wind farms. In sabkha corridors and substations, capillary breaks and sodicity control are essential, while geothermal pads require measures to limit fines migration. Low-carbon solutions, such as recycled aggregates, biochar, and mulches, along with bio-based polymers, can be effective when chosen based on these geotechnical indicators.

Future work should focus on in situ SWCC hysteresis, calibrated collapse and dispersion thresholds, microcrust mechanics and dust supply, and the durability of low-carbon stabilizers. These advances would further strengthen risk-based land degradation management.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the Deanship of Scientific Research at Shaqra University for supporting this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR). United Nations LDC Portal. Available online: https://www.un.org/ldcportal/content/united-nations-office-disaster-risk-reduction-undrr (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Montanarella, L.; Scholes, R.; Brainich, A. The Assessment Report on Land Degradation and Restoration; Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES): Bonn, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yamanoshita, M. IPCC Special Report on Climate Change and Land; JSTOR: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Diallo, I.D.; Tilioua, A.; Darraz, C.; Alali, A.; Sidibe, D. Study and Evaluation of the Effects of Vegetation Cover Destruction on Soil Degradation in Middle Guinea through the Application of Remote Sensing and and Geotechnics. Heliyon 2024, 10, e23556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzabaev, A.; Stringer, L.C.; Benjaminsen, T.A.; Gonzalez, P.; Harris, R.; Jafari, M.; Stevens, N.; Tirado, C.M.; Zakieldeen, S. Cross-Chapter Paper 3: Deserts, Semiarid Areas and Desertification. In Climate Change 2022—Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023; pp. 2195–2231. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Land: An IPCC Special Report on Climate Change. Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems; IPCC: Rome, Italy, 2019; p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Quality Infrastructure for Renewables Facing Extreme Weather; IRENA: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Molod, M.; Faris, M.K.; Aldaood, A. Unsaturated Soil Behavior: Soil Water Characteristic Curve (SWCC) Review Study. Anbar J. Eng. Sci. 2025, 16, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Guo, L.; Miao, J.; Qu, X.; Xiao, S. Approaches for Estimating the Unsaturated Hydraulic Conductivity of Compacted Quartz Sand via Particle Packing Theory. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhu, X.; Mi, M. Progress and Prospects of Research on Physical Soil Crust. Soil Syst. 2025, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, W.; Alnuaim, A. Effect of Geopolymer Treatment on the Ultimate Bearing Capacity of Sabkha Soil under Axial Loading. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 20846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, H. Soil Moisture Effects on Sand Saltation and Dust Emission Observed over the Horqin Sandy Land Area in China. J. Meteorol. Res. 2014, 28, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daba, A.W.; Qureshi, A.S. Review of Soil Salinity and Sodicity Challenges to Crop Production in the Lowland Irrigated Areas of Ethiopia and Its Management Strategies. Land 2021, 10, 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schill, C.; Anderson, A.; Baldus-Jeursen, C.; Burnham, L.; Micheli, L.; Parlevliet, D.; Pilat, E.; Stridh, B.; Urrejola, E.; Cattaneo, G. Soiling Losses—Impact on the Performance of Photovoltaic Power Plants; IAE: Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Petlovanyi, M.; Sai, K. Research into Cemented Paste Backfill Properties and Options for Its Application: Case Study from a Kryvyi Rih Iron-Ore Basin, Ukraine. Miner. Depos. 2024, 18, 162–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovych, V.; Skrobala, V.; Tyndyk, O.; Kaspruk, O. Hydro-Ecological Monitoring of Heavy Metal Pollution of Water Bodies in the Western Bug River Basin within the Mining-Industrial Region. Min. Miner. Depos. 2024, 18, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredlund, D.G.; Rahardjo, H. Soil Mechanics for Unsaturated Soils; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Van Genuchten, M.T. A Closed-form Equation for Predicting the Hydraulic Conductivity of Unsaturated Soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1980, 44, 892–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mualem, Y. A New Model for Predicting the Hydraulic Conductivity of Unsaturated Porous Media. Water Resour. Res. 1976, 12, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredlund, D.G.; Morgenstern, N.R.; Widger, R.A. The Shear Strength of Unsaturated Soils. Can. Geotech. J. 1978, 15, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Special Report on Renewable Energy Sources and Climate Change Mitigation; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011; Volume 20. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, D.; Qi, Y.; Wang, S. Experimental Study on Scour Resistance Performance Enhancement of Chongqing Red Clay. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhavya, K.; Nagaraj, H.B. Influence of Soil Structure and Clay Mineralogy on Atterberg Limits. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Otaibi, F.; Aldaihani, H.M. Influence of Bitumen Addition on Sabkha Soil Shear Strength Characteristics Under Dry and Soaked Conditions. Am. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2018, 11, 1199–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abduljauwad, S.N.; Al-Amoudi, O.S.B. Geotechnical Behaviour of Saline Sabkha Soils. Geotechnique 1995, 45, 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H. Rainfall Infiltration Process of a Rock Slope with Considering the Heterogeneity of Saturated Hydraulic Conductivity. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 9, 804005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, K.S. Measurement and Modeling of Unsaturated Hydraulic Conductivity. In Hydraulic Conductivity–Issues, Determination and Applications; Intech: Xiamen, China, 2011; pp. 419–434. [Google Scholar]

- McCartney, J.S.; Villar, L.; Zornberg, J.G. Estimation of the Hydraulic Conductivity Function of Unsaturated Clays Using an Infiltration Column Test. In Proceedings of the 6th Brazilian Conference on Unsaturated Soils (NSAT), Salvador, Brazil, 1–3 November 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bowyer-Bower, T.A.S. Effects of Rainfall Intensity and Antecedent Moisture on the Steady-state Infiltration Rate in a Semi-arid Region. Soil Use Manag. 1993, 9, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Tian, Y.; Gui, R.; Liu, Y. Experimental Study on the Effect of Key Factors on the Soil–Water Characteristic Curves of Fine-Grained Tailings. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 710986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, Y.; Lu, W.; Fu, K. Research on Resilient Modulus Prediction Model and Equivalence Analysis for Polymer Reinforced Subgrade Soil under Dry–Wet Cycle. Polymers 2023, 15, 4187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Huang, C. Stiffness Degradation of Expansive Soil Stabilized with Construction and Demolition Waste Under Wetting–Drying Cycles. Coatings 2025, 15, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edil, T.B.; Motan, S.E. Soil-Water Potential and Resilient Behavior of Subgrade Soils. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Transportation Reasearch Board, Washington, DC, USA, 15–19 January 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Ranaivoson, A.; Edil, T.; Benson, C.; Sawangsuriya, A. Pavement Design Using Unsaturated Soil Technology; Minnesota Department of Transportation: Saint Paul, MN, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.; Senetakis, K. Bearing Capacity Equations for Shallow Foundations on Unsaturated Soils with Uniform and Linearly Varied Suction Profiles. In Proceedings of the UNSAT 2018: The 7th International Conference on Unsaturated Soils, Clear Water Bay, Hong Kong, China, 3–5 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, C.; Feng, H.; Wang, C.; Zhang, N.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Li, S.; Jiang, H.; Li, Y. A Numerical Simulation of Moisture Reduction in Fine Soil Subgrade with Wicking Geotextiles. Materials 2024, 17, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavi, I.; Thevs, N.; Priori, S. Soil Salinity and Sodicity in Drylands: A Review of Causes, Effects, Monitoring, and Restoration Measures. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 712831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zuo, Y.; Wang, T.; Han, Q. Salinity Effects on Soil Structure and Hydraulic Properties: Implications for Pedotransfer Functions in Coastal Areas. Land 2024, 13, 2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, Z.; Guo, H.; Zhao, J.; Luo, H.; Huang, X. A Perspective View of Salt Crystallization from Solution in Porous Media: Morphology, Mechanism, and Salt Efflorescence. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Zhou, J.L.; Cai, Q.; Liu, S.; Xiao, J. Comparing Surface Erosion Processes in Four Soils from the Loess Plateau under Extreme Rainfall Events. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2021, 9, 520–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Qi, X.; Ma, C.; Wang, Z.; Li, H. Response of Sheet Erosion to the Characteristics of Physical Soil Crusts for Loessial Soils. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 905045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Fan, H.; Xie, F.; Lei, B.; Ren, G. The Role of Soil Dispersivity and Initial Moisture Content in Splash Erosion: Findings from Consecutive Single-Drop Splash Tests. Biosyst. Eng. 2024, 243, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, T.A.; Ali, F.H.; Hashim, S.; Huat, B.B.K. Relationship Between Shear Strength and Soil Water Characteristic Curve of an Unsaturated Granitic Residual Soil; Universiti Putra Malaysia Press: Serdang, Malaysia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Carey, W.P. Physical Basis and Potential Estimation Techniques for Soil Erosion Parameters in the Precipitation-Runoff Modeling System (PRMS); US Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 1984; Volume 84. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.; Lee, J.; Lee, K.; Jo, H.; Choi, W.; Cho, J.; Chung, D. Assessment of Wind-Related Parameters and Erodibility Potential Under Winter Wheat Canopy in Reclaimed Tidal Flat Land. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbrust, D.V. Effects of Surface Roughness on Erosion of Soil by Wind. Master’s Thesis, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Marticorena, B.; Bergametti, G.; Gillette, D.; Belnap, J. Factors Controlling Threshold Friction Velocity in Semiarid and Arid Areas of the United States. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1997, 102, 23277–23287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astitha, M.; Lelieveld, J.; Abdel Kader, M.; Pozzer, A.; de Meij, A. New Parameterization of Dust Emissions in the Global Atmospheric Chemistry-Climate Model EMAC. Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss 2012, 12, 13237–13298. [Google Scholar]

- Lyles, L. Wind Erosion: Processes and Effect on Soil Productivity. Trans. ASAE 1977, 20, 880–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Újvári, G.; Kok, J.F.; Varga, G.; Kovács, J. The Physics of Wind-Blown Loess: Implications for Grain Size Proxy Interpretations in Quaternary Paleoclimate Studies. Earth Sci. Rev. 2016, 154, 247–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.D.; Dobrowolski, J.P.; West, N.E.; Gillette, D.A. Microphytic Crust Influence on Wind Erosion. Trans. ASAE 1995, 38, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Zhang, J.; Xu, X. Estimation of Aerodynamic Entrainment in Developing Wind-Blown Sand Flow. Sci. Prog. 2024, 107, 00368504241290970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayaud, J.R.; Webb, N.P. Vegetation in Drylands: Effects on Wind Flow and Aeolian Sediment Transport. Land 2017, 6, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presley, D.; Tatarko, J. Principles of Wind Erosion and Its Control; Agricultural Experiment Station and Cooperative. Kansas State University Agricultural Experiment Station and Cooperative: Manhattan, KS, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lyles, L.; Schrandt, R.L.; Schmeidler, N.F. How Aerodynamic Roughness Elements Control Sand Movement. Trans. ASAE 1974, 17, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyles, L. 4. Basic Wind Erosion Processes. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 1988, 22, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Batra, A.; Pachauri, R. An Experimental Study on Effect of Dust on Power Loss in Solar Photovoltaic Module. Renewables 2017, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, B.A.; Griffiths, D. V Internal Erosion of Embankments: A Review and Appraisal. In Proceedings of the Rocky Mountain Geo-Conference 2018, Golden, CO, USA, 2 November 2018; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2018; pp. 61–75. [Google Scholar]

- Vakili, A.H.; Selamat, M.R.b.; Mohajeri, P.; Moayedi, H. A Critical Review on Filter Design Criteria for Dispersive Base Soils. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2018, 36, 1933–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.L.; Greenman, C. Collapsible Soils in Colorado; Colorado Geological Survey: Golden, CO, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Rawas, A.A. State-of-the-Art-Review of Collapsible Soils. Sultan Qaboos Univ. J. Sci. 2000, 5, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, S.; Chowdhury, R.H. Swell–Shrink–Consolidation Behavior of Compacted Expansive Clays. Int. J. Geotech. Eng. 2013, 7, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Gahlot, P.K.; Purohit, D.G.M. Dispersive Soils-Characterization, Problems and Remedies. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 5, 2478–2484. [Google Scholar]

- Alabdullah, S.F.I.; Hassab, Y.; Teama, Z.; Aldahwi, S. Soil Retention Tests for Determining Dispersion of Clayey Soils. GEOMATE J. 2022, 22, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichi, A.M.; Abdulazeez, M.M. Rate of Decomposition and Nutrient Release from the Foliages of Acacia nilotica (L) in Three Alfisols. Sahel J. Life Sci. FUDMA 2024, 2, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzampoglou, P.; Ilia, I.; Karalis, K.; Tsangaratos, P.; Zhao, X.; Chen, W. Selected Worldwide Cases of Land Subsidence Due to Groundwater Withdrawal. Water 2023, 15, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffat, R.; Faundez, F.; Villalobos, F.A. Experimental Investigation and Analysis of the Influence of Depth and Moisture Content on the Relationship Between Subgrade California Bearing Ratio Tests and Cone Penetration Tests for Pavement Design. Buildings 2025, 15, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erazo, J.; Solórzano-Blacio, C.; Realpe, G.; Albuja-Sánchez, J. Effect of Matric Suction on Shear Strength and Elastic Modulus of Unsaturated Soil in Reconstituted and Undisturbed Samples. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington State Department of Transportation. Appendix B: Infiltration Estimation Method Selection and Interpretation Guide. In Hydraulics Manual M 23-03; Washington State Department of Transportation: Olympia, WA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Saab, A.L.; Rodrigues, A.L.d.C.; Rocha, B.P.; Rodrigues, R.A.; Giacheti, H.L. Suction Influence on Load–Settlement Curves Predicted by DMT in a Collapsible Sandy Soil. Sensors 2023, 23, 1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huayllazo, Y.; Infa, R.; Soto, J.; Lazarte, K.; Huanca, J.; Alvarez, Y.; Teixidó, T. Using Electrical Resistivity Tomography Method to Determine the Inner 3D Geometry and the Main Runoff Directions of the Large Active Landslide of Pie de Cuesta in the Vítor Valley (Peru). Geosciences 2023, 13, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, A.; Lapenna, V.; Piscitelli, S. Electrical Resistivity Tomography Technique for Landslide Investigation: A Review. Earth Sci. Rev. 2014, 135, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, B.M.; Cândido, B.; Jimenez, P.A.J.; Avanzi, J.C.; Silva, M.L.N. UAV-Based Soil Water Erosion Monitoring: Current Status and Trends. Drones 2025, 9, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.; Chappuies, J.; Sloan, G.; Rouland, G.; Rai, A.; Dong, Y. A Global Perspective on Electrical Resistivity Tomography, Electromagnetic and Ground Penetration Radar Methods for Estimating Groundwater Recharge Zones. Front. Water 2025, 7, 1636613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]