Abstract

With the rapid development of the digital economy, digital technologies have become a key driver of rural revitalization. To systematically analyze the enabling mechanisms of digital technology for rural revitalization, this study utilizes panel data from 30 Chinese provinces spanning 2014–2023. It measures digital technology levels through the number of digital economy-related invention patents granted annually, constructs a comprehensive evaluation index system for rural revitalization, and employs fixed-effects models, mediation models, and spatial Durbin models to explore the direct impact, indirect effects, and spatial effects of digital technology on rural revitalization. The findings reveal that the following: (1) Digital technology significantly empowers the rural revitalization strategy, effectively promoting the comprehensive and sustainable development of the economic, social, and cultural sectors in rural areas. (2) Digital technology exerts partial mediating effects through cultural industry development and higher education advancement, thereby indirectly supporting sustainable rural revitalization. (3) At the spatial level, digital technology exhibits a significant positive spatial spillover effect on rural revitalization overall. Further regional analysis reveals positive spatial spillover effects in the eastern and central regions, whereas the western and northeastern areas exhibit negative spatial spillover. The study concludes that optimizing the spatial layout and promoting coordinated development of digital technologies across areas should be tailored to local conditions. Strengthening cultural industries and educational systems is essential to fully harness the enabling potential of digital technologies for rural revitalization and to construct a rural revitalization path characterized by regional coordination and multidimensional sustainability across the economy, society, and environment.

1. Introduction

The “Rural Comprehensive Revitalization Plan (2024–2027)” issued in January 2025 explicitly lists “digital rural construction” as a key measure to advance the rural revitalization strategy, underscoring the critical role of digital technology in modernizing agriculture and rural areas. However, the “digital divide” between urban and rural areas in China remains significant. Rural regions remain relatively underdeveloped in terms of digital infrastructure development, the popularization of digital skills, and the cultivation of digital industries, thereby limiting the potential of digital technology to drive rural revitalization. Existing studies largely remain at the level of theoretical discussion and lack systematic empirical analyses based on large samples and cross-regional data, which limits policymakers’ scientific understanding of the mechanisms by which digital technology promotes rural revitalization. For instance, Zeng and Hu [1] systematically explored key issues and development pathways for digital technology-enabled rural revitalization from the perspective of Chinese modernization. They based their analysis on field research in rural areas. Zhou and Zhang [2] revealed the impact of digital village construction on rural revitalization and its underlying mechanisms through econometric analysis. Zhong and Liu [3] developed an explanatory framework for how digital technology drives comprehensive rural revitalization, based on actor-network theory. However, these studies predominantly focus on either digital technology or rural revitalization as single dimensions. They often lack systematic empirical validation of their interactive relationship and operational mechanisms. In addition, existing empirical research usually suffers from a limited sample scope and a single spatial scale. For instance, Yang and Yan [4] analyzed how digital technology empowers rural revitalization through case studies of national demonstration counties. Yet, they failed to examine their relationship from a national perspective. Wu [5] employed multi-level governance theory to identify pathways for achieving digital governance levels across 58 counties in Anhui Province.

Furthermore, international literature indicates that, as a crucial driver of global development, digital technology, with its application experiences across different countries and fields, holds significant value as a reference for exploring pathways to rural revitalization in China. Skare and Soriano [6] found, from a global perspective, that the dual influences of technological diffusion and institutional differences shape the adoption of digital technology. Lai et al. [7] found that enterprises’ digital technology innovation significantly enhances their international diversification strategies by optimizing resource allocation. Shang et al. [8] pointed out that the adoption of digital agricultural technologies is highly dependent on the coordination between system support and policy environment. These international studies show that the enabling effect of digital technology depends not only on the macro-environment and policy support but also on system coordination and ecosystem construction, which provides valuable insights for China to explore the mechanisms of action of digital technology in the context of rural revitalization. However, their analysis remained confined to the county level and could not fully reveal the complex interplay between digital technology and rural revitalization at larger spatial scales.

To address the aforementioned research gaps, this paper’s marginal contribution is primarily reflected in the following three aspects:

(1) Research Innovation: Drawing on panel data from 30 Chinese provinces spanning 2014–2023, this study systematically examines the impact of digital technologies on the sustainable development of rural revitalization at the provincial level. It enriches the theoretical framework for digital technology-enabled rural revitalization while empirically revealing its practical mechanisms.

(2) Methodological Innovation: Considering the spatial autocorrelation characteristics between digital technology and rural revitalization, this study employs the Spatial Durbin Model (SDM) to empirically test the impact effects of digital technology on rural revitalization in both local and neighboring regions, revealing regional differences from a spatial spillover perspective.

(3) Mechanism Innovation: This study introduces two mediating variables—cultural industries and higher education—to explore the indirect role of digital technology in rural revitalization through cultural industry development and educational advancement. It further clarifies the transmission mechanisms and underlying logic between these variables, thereby providing scientific evidence and policy references for advancing digital rural sustainable development within the context of China’s modernization.

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

Given the characteristics of digital technology and its significant strategic importance in national documents (see the deployment on accelerating digital rural development in the Comprehensive Rural Revitalization Plan (2024–2027)), this paper systematically demonstrates the direct and indirect driving effects of digital technology on rural revitalization and its spatial spillover effects within a theoretical and empirical framework. Based on this analysis, research hypotheses are proposed. The specific analysis is as follows.

2.1. The Direct Impact of Digital Technology on Rural Revitalization

Digital technologies provide endogenous momentum for comprehensive rural revitalization by transforming information flow, resource allocation, and production organization. They help narrow the urban–rural gap and drive the realization of the “Five Revitalizations” objectives [9]. Digital technology transforms data into a core production factor, driving the in-depth integration of digital industrialization and industrial digitalization, reshaping the rural industrial structure, injecting sustained innovative vitality and economic momentum into traditional agriculture and rural industries, and laying a solid foundation for the endogenous and sustainable growth of the rural economy [10]. Meanwhile, by reducing transaction costs and improving organizational efficiency, it optimizes the rural economy’s operating mode and enhances the resilience and sustainability of industrial development [11]. In the context of ecological sustainability, digital technologies enable real-time monitoring and early warning in rural environments through IoT and remote sensing, providing essential technical support for sustainable governance and the development of green, low-carbon, and livable villages [12]. Regarding rural cultural vitality, digital technology can be applied to the preservation of intangible cultural heritage, the dissemination of rural culture, and innovation in cultural consumption scenarios. Through digital terminals and new media platforms, it facilitates the reverse flow of cultural resources and the bidirectional circulation of urban–rural cultural elements, thereby stimulating new momentum in rural cultural industries [13,14]. Regarding governance effectiveness, digital governance tools have restructured rural governance pathways, enhancing coordination and administrative efficiency, thereby serving as an essential carrier for building a harmonious, stable, and efficient rural social governance system and safeguarding the sustainable development of society. Finally, with respect to prosperity, digital technology enhances public service delivery and market access, thereby promoting employment, entrepreneurship, and income growth among rural residents, advancing continuous improvements in living standards and the universal enhancement of social well-being [15]. Based on this logical chain, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1.

Digital technology exerts a significant positive influence on rural revitalization.

2.2. Indirect Impacts of Digital Technology on Rural Revitalization

The pervasiveness and diffusivity of digital technology yield a pronounced multiplier effect [16], facilitating the formation of multidimensional pathways for advancement mediated by cultural industries and higher education, thereby propelling the high-quality development of rural revitalization.

The flourishing of cultural industries serves as a vital pathway for promoting rural revitalization. On the one hand, developing cultural industries can directly drive rural economic growth by creating cultural tourism brands, developing cultural and creative products, and fostering the homestay economy. These initiatives generate employment opportunities, increase farmers’ incomes, and achieve “cultural prosperity for the people.” On the other hand, it enhances the soft power of rural social development. By revitalizing cultural heritage, reshaping villages’ cultural ecosystems, and strengthening villagers’ cultural confidence, it injects sustained endogenous momentum into rural revitalization.

Digital technology provides critical support for revitalizing the cultural industry in three key areas: Firstly, it strengthens the industrial foundation by enabling the digital preservation and recreation of rural cultural heritage through digital archives and VR exhibitions [17]. By expanding its reach via internet platforms, it activates existing rural cultural resources, laying a solid groundwork for industrial development. Secondly, it drives industrial innovation: Digital platforms, such as live-streaming e-commerce and social marketing, expand marketing channels for rural cultural tourism and creative products, enabling targeted traffic acquisition and brand building. Simultaneously, big data analytics provides precise insights into consumer demand, fostering new customized and experiential cultural formats [18]. Finally, optimizing industrial services: Digital tools, such as innovative tourism platforms and online booking systems, comprehensively enhance visitor experiences before, during, and after trips, thereby improving service efficiency and satisfaction and boosting the attractiveness and competitiveness of rural cultural industries. Based on this, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2.

Digital technology can empower rural revitalization by promoting the sustainable development of the cultural industry.

The development of higher education provides indispensable intellectual and talent support for rural revitalization, with its promotional role manifested in two primary aspects. On the one hand, it supplies talent and scholarly resources for rural revitalization. Higher education institutions directly channel construction capabilities into rural areas by cultivating versatile professionals who possess technical expertise, business acumen, and familiarity with rural contexts [19]. Simultaneously, the transformation and application of university research outcomes—such as green agricultural technologies and ecological planning schemes—in rural practices have provided theoretical support and technical pathways for rural sustainable development.

Second, higher education enhances the human capital and innovation capacity required for rural revitalization. Through vocational training and continuing education, it effectively improves the overall quality and digital skills of the rural workforce, narrowing the “digital divide” [20]. Furthermore, the innovative and critical thinking fostered by higher education stimulates endogenous innovation in rural areas, driving self-renewal and upgrading of industrial models, governance approaches, and other domains [21].

Digital technology has become a key enabler of the development of higher education and of enhancing its service to rural areas through two primary avenues: on the one hand, it broadens the reach of educational resources. Leveraging online education platforms, digital courses, and virtual simulation experiments, digital technology breaks down geographical and temporal barriers. This enables the cost-effective and efficient dissemination of high-quality higher-education resources to rural regions, significantly expanding opportunities for rural students and residents to access high-quality education on sustainable development. On the other hand, it deepens educational reform and teaching: digital technology drives innovation in “smart education” models. Through personalized learning path recommendations, big data-driven learning analytics, and interactive teaching scenarios, it enhances teaching effectiveness and the precision of talent cultivation. Thus, providing rural areas with modern talent proficient in digital technologies and equipped with the concept of sustainable development. Based on this, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3.

Digital technology can empower rural revitalization by advancing higher education.

2.3. Spatial Spillover Effects of Digital Technology on Rural Revitalization

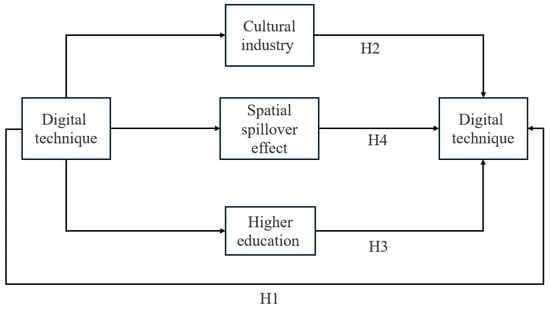

Figure 1 illustrates the theoretical analysis framework of this paper. Economic and technological activities exhibit geographical diffusion, and digital technologies are no exception. According to the classical definition of spillover effects, development activities in one region can influence neighboring areas and trigger chain reactions [22,23]. The high permeability and replicability of digital technologies enable regions with advanced levels of digitalization to build technical expertise first. This expertise then spreads to surrounding areas through talent mobility, technological collaboration, and industrial gradient transfer, thereby enhancing the latter’s capabilities in agricultural digitalization, industrial upgrading, and even environmental sustainability [24,25]. Simultaneously, digital ecosystems anchored by internet platforms break geographical barriers, deepening interregional exchange and collaboration. As information transmission costs decrease and factor mobility accelerates, interregional cooperation can leverage complementary advantages and drive broader synergistic rural revitalization. This leads to the following hypothesis:

Figure 1.

Theoretical mechanism diagram.

Hypothesis 4.

Digital technology has a significant positive spatial spillover effect on rural revitalization.

3. Variable and Model

3.1. Variable Declaration

3.1.1. Explained Variable

This study uses the level of rural revitalization development as the explanatory variable, denoted Rural. Drawing upon relevant research [26,27,28,29,30], a comprehensive evaluation system for rural revitalization is constructed across five dimensions: thriving industries, ecological livability, civilized rural culture, effective governance, and prosperous livelihoods. Entropy values are employed for numerical quantification. The specific indicator system is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Rural Revitalization Index Measurement System.

This study, in accordance with the general requirements of the “Five Revitalizations” in the “Rural Revitalization Strategy Plan (2018–2022)”, has constructed a comprehensive evaluation system covering five dimensions: thriving industries, livable ecology, civilized rural customs, effective governance, and affluent life, ensuring consistency with national strategic goals.

- Prosperous industries: Referring to the construction ideas of Yan and Wu [26] and Jia et al. [27], indicators such as agricultural labor productivity and per capita grain output are selected to reflect agricultural production efficiency and basic guarantee capabilities.

- Eco-friendly and livable: The selection of indicators draws on Li et al.’s [14] research on rural living environments, using forest coverage rate, harmless treatment rate of domestic waste, etc., to measure the ecological environment and sanitation conditions.

- Civilized rural customs: Based on Zhou and Jia’s [18] measurement of rural cultural development, indicators such as per capita consumption expenditure on cultural and recreational activities and radio and television coverage rate are selected to reflect cultural investment and the accessibility of public services.

- Effective governance: Referring to Zhu and Liang’s [19] rural governance evaluation framework, indicators such as the urban–rural income ratio and effective irrigation area are introduced to evaluate the effectiveness of governance in promoting fairness and providing public goods.

- Affluent life: The indicator design integrates Xu et al. [29] and the National Bureau of Statistics’ people’s livelihood development monitoring system, covering dimensions such as per capita electricity consumption, medical accessibility, safe drinking water, and social security.

The entropy method is used to measure and evaluate rural revitalization, as it is simple and practical, easy to operate, and yields reasonable and objective results. Following [31], the entropy method is used for comprehensive evaluation; the steps are as follows.

Standardization of indicators: Considering that the dimensions and orders of magnitude of each indicator are different, first, Stata software is used to standardize the data. The specific indicator standardization formula is as follows:

The standardization calculation formula for positive indicators is:

The standardization calculation formula for negative indicators is:

and , respectively, represent the indicator values of the j-th indicator in the i-th year before and after standardization processing; and , respectively, represent the maximum and minimum values of the capital X with subscripts i and j.

The entropy method determines the weights of indicators:

First, calculate the information entropy of each indicator based on the standardized indicator value, which is denoted as uppercase .

where n is the number of evaluation years.

Secondly, the weight of each indicator is calculated based on the information entropy , among them, m represents the number of indicators.

Based on the index values after standardized processing and Indicator weight . Calculate the rural revitalization index for each year using the linear weighting method.

Using standardized indicator values and weights, the linear weighting method is applied to calculate the rural revitalization index for each year. The rural revitalization index ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating greater rural revitalization.

3.1.2. Explanatory Variable

Digital Technology (DIG) measures digital innovation levels using the number of digital economy-related patents granted in a given year, following the research approach outlined in [32,33,34]. Specifically, digital economy patent data were obtained from the China Research Data Service Platform, yielding city-year-dimensioned data. City-level data were aggregated to provincial-level data, then increased by one and log-transformed to measure digital innovation levels.

3.1.3. Mediating Variables

Cultural Industry (CI): Drawing on the research findings of Zhou [17], the level of cultural industry development across 30 provinces from 2014 to 2023 was measured using the entropy method.

Higher Education (HE): Following relevant studies [35], the proportion of the population enrolled in higher education was adopted as the metric for assessing higher education attainment.

The construction of the cultural industry index follows the three-dimensional logic of “foundation-development-service”: (1) For the industrial foundation, quantitative indicators such as museums and mass cultural institutions are selected, as they directly reflect the stock of regional public cultural facilities and the input of official cultural resources; (2) Industrial development covers per capita cultural consumption, transportation accessibility, etc., aiming to capture the vitality of cultural consumption and the supporting conditions for the development of the cultural and tourism industry; (3) Industrial services include indicators such as travel agencies and star-rated hotels to measure the market-oriented supply capacity of cultural tourism services. This system avoids relying solely on the cultural industry’s added value and instead comprehensively evaluates the cultural industry ecosystem from both the supply and demand sides, aligning more closely with the actual characteristics of the integration of rural culture and tourism (Table 2).

Table 2.

Cultural and Tourism Industrialization Index Measurement System.

3.1.4. Control Variables

To mitigate the influence of other factors on rural revitalization, this study adopts the following control variables based on prior research [36,37,38,39]: Firstly, tax burden (TAX), measured as the ratio of tax revenue to total economic output. Secondly, the industrialization level (IND) is represented by the proportion of industrial value-added in GDP. Thirdly, openness to the outside world (OPEN), assessed by the ratio of each province’s total import and export trade to GDP. Opening up facilitates the flow of capital, technology, and other factors, thereby influencing regional economies. Fourthly, investment in science and education (TEC) is measured as the proportion of provincial fiscal expenditures on science and education relative to local general budget expenditures. Fifthly, government intervention (GI), measured as the proportion of local general budget expenditures relative to GDP. Stronger fiscal capacity increases the likelihood of policy support for digital technologies to advance rural revitalization.

In terms of the tax burden, a higher macroeconomic tax burden may inhibit economic vitality and corporate investment in innovation [36], thereby affecting capital accumulation in digital technology, as measured by the share of tax revenue in GDP. At the level of industrialization, it may have synergistic or competitive relationships with the development of the digital economy [8] and directly affect the transfer of rural labor, as measured by the share of industrial added value in GDP. The degree of openness to the outside world affects regional digital technology acquisition and rural characteristic industries by promoting the international flow of technology, capital, and knowledge, as measured by the share of total imports and exports in GDP. The level of investment in science and education, as a direct policy tool to drive local innovation and human capital development [38], is measured by the proportion of local fiscal expenditure on science and education in the general budget. In terms of the degree of government intervention, greater capacity for intervention may affect the diffusion of digital technology and the efficiency of resource allocation through channels such as industrial policies and infrastructure [37], as measured by the proportion of local government general budget expenditure to GDP. Data for all control variables are obtained from the China Statistical Yearbook and various provincial statistical yearbooks. By controlling the variables listed above, this study aims to isolate the causal effect of digital technology on rural revitalization, independent of these necessary socioeconomic conditions.

3.2. Data Sources and Descriptive Statistics

This study employs panel data from 30 provinces in China (excluding Tibet, Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan) for the period 2014–2023. The data are primarily sourced from: macroeconomic, social development, and partial rural revitalization indicators are derived from the China Statistical Yearbook compiled by the National Bureau of Statistics and the respective provincial (regional and municipal) statistical yearbooks; data on science and education investment and related fiscal information are referenced from the China Education Expenditure Statistical Yearbook; and the number of digital economy-related invention patents granted is obtained from the patent database of the China Research Data Service Platform (CNRDS).

For missing data in specific provinces or years, linear interpolation was applied to complete the dataset. Additionally, to mitigate the effects of heteroscedasticity and individual outliers and to enhance model fit, all variables were standardized. Finally, all empirical tests in this study were conducted using Stata 16.0, and the descriptive statistics for the variables are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Variable Explanations and Descriptive Statistics.

3.3. Measurement Model Specification

3.3.1. Symbol Conventions

To maintain the consistency and readability of symbols throughout the text, this section first provides a unified explanation of the symbols that will be used in the subsequent models (Table 4).

Table 4.

Symbol Conventions and Contents.

3.3.2. Baseline Regression Model

Based on the preceding theoretical analysis, this paper establishes the following baseline regression model to examine the direct impact of digital technologies on rural revitalization development.

Here, i denotes province, t denotes year, j is the index for control variables to distinguish different control variables, is the explained variable, i.e., the level of rural revitalization development; is the core explanatory variable, representing digital technology; denotes the control variables; , represent the individual and time fixed effects, respectively; is the disturbance term.

3.3.3. Mediation Effect Testing Model

To examine the role of the mediating variable in the relationship between digital technology and rural revitalization, drawing on relevant research [40], the following model is designed:

Mod denotes the mediating variable, representing cultural industries and higher education, respectively.

3.3.4. Spatial Econometric Model

To examine the spatial spillover effects of digital technologies on rural revitalization, this paper constructs a spatial econometric model based on Equation (1):

In Equation (8), W denotes the spatial weight matrix. This paper employs an inverse square distance matrix. indicates the spatial autocorrelation coefficient of the variable. , represents the spillover effect coefficient of the explanatory variable DIG, indicates the spillover effect of the control variable , signifies the individual effect within region i, represents the time effect, and denotes the spatial correlation coefficient of the random error term. The spatial econometric model will be selected later in this paper through correlation tests.

4. Empirical Analysis and Discussion

4.1. Analysis of Benchmark Regression Results

To address heteroscedasticity, to more closely approximate a normal distribution, and to facilitate the interpretation of elastic relationships between variables, this study applies a natural logarithmic transformation to all continuous variables. After the logarithmic transformation, the economic implications of the model coefficients become percentage-change relationships. This treatment enhances the model’s economic interpretability and makes variables with different dimensions comparable. Before benchmark regression, the panel data underwent VIF testing. The VIF results indicate that the variance inflation factors for both core explanatory variables and control variables remain below 10, suggesting no severe multicollinearity issues among the variables. The multicollinearity test results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Collinearity Test.

Additionally, before conducting the benchmark regression, this study enhanced the robustness of the regression results by selecting an appropriate regression model through testing. Based on the Hausman test results, the chi-squared value (6 degrees of freedom) was 101.76 with a p-value of 0.000. This indicates that the null hypothesis of the random effects model was rejected. Therefore, a two-way fixed-effects regression model was chosen as the benchmark.

Table 6 presents the benchmark regression results based on Model (1). Column (1) employs ordinary least squares regression, Column (2) incorporates provincial fixed effects, Column (3) includes provincial fixed effects and time fixed effects, Column (4) adds control variables with provincial fixed effects, and Column (5) further incorporates additional control variables with both time and provincial fixed effects.

Table 6.

Benchmark Regression Results.

The regression results indicate that all digital technology variables are positive and are statistically significant at the 1% level. Subsequently, to mitigate endogeneity arising from omitted variables associated with key explanatory variables, additional control variables were included in the regression. After confirming no multicollinearity among explanatory variables via VIF testing, Column (5) data shows that the regression coefficient for digital technology is 0.166, significant at the 1% level. This indicates that a 1% increase in digital technology is associated with a 0.166 percentage-point increase in rural revitalization. Additionally, the R2 value increased from 0.867 to 0.877, indicating greater model explanatory power. This demonstrates a significant positive correlation between digital technology and rural revitalization, thereby confirming Hypothesis 1.

Based on regression results for other control variables, the tax burden negatively affects rural revitalization. This stems from the high proportion of indirect taxes in China’s total tax revenue [41], coupled with the relatively low overall income levels of rural residents. Their higher Engel’s coefficient indicates a larger share of basic living expenses in consumption expenditures, resulting in a relatively heavier indirect tax burden for rural residents. This exacerbates income inequality between urban and rural residents across income levels, hinders integrated urban–rural development, and, consequently, impedes the implementation of the rural revitalization strategy. The level of industrialization, the degree of openness to the outside world, investment in science and education, and the intensity of government intervention positively affect rural revitalization. The industrialization level shows a significant positive effect at the 5% level, indicating that increased industrialization contributes to rural revitalization. This primarily stems from industrial development extending industrial chains—such as agricultural processing and rural specialty manufacturing—transforming rural resources into commercial value (e.g., grain processing, specialty handicraft production). Simultaneously, it creates non-agricultural employment opportunities for rural labor, boosting farmers’ incomes and narrowing the urban–rural income gap. The test of the level of openness to the outside world exceeded the 5% significance level, indicating that openness enables specialty rural agricultural products—such as organic fruits and Chinese medicinal herbs—to enter international markets, thereby enhancing added value through exports. Simultaneously, it facilitates the adoption of advanced foreign cultivation and breeding techniques, thereby improving agricultural product quality and competitiveness and promoting rural revitalization. Although not statistically significant, the positive coefficient on investment in science and education suggests that it may drive agricultural technological innovation through research funding, thereby reducing production costs and improving yields and quality. Educational investments, such as rural vocational education and skills training, can also enhance farmers’ cultural literacy and professional skills, making them better suited for modern agriculture. This facilitates a shift from physical labor to skilled work, reducing reliance on manual labor. Government intervention exhibits a statistically significant positive coefficient at the 10% level. This indicates that the government can act as the market’s invisible hand. For rural public services such as education, healthcare, and elderly care—which possess strong public welfare characteristics and are difficult for market mechanisms to supply fully—the government can ensure their accessibility through fiscal investment and policy support. Consolidate the social foundation for rural revitalization and enhance the sustainability and inclusiveness of rural development.

To assess the actual magnitude of the impact of digital technology on rural revitalization, we further calculated the standardized coefficients (Beta coefficients) and average marginal effects. The results in column (5) of Table 6 show that the unstandardized coefficient of digital technology (lnDIG) is 0.166. After standardization, its Beta coefficient is 0.182 (p < 0.01), indicating that for each one-standard-deviation increase in digital technology, rural revitalization increases by approximately 0.182 standard deviations. For comparison, the Beta coefficient for the industrialization level (lnIND) is 0.156, and that for opening up (lnOPEN) is 0.142. This indicates that, after controlling for other factors, digital technology is the most critical explanatory variable for rural revitalization, and its standardized effect size exceeds those of traditional economic drivers.

From the perspective of economic resilience, for every 1% increase in the level of digital technology, the development level of rural revitalization increases by approximately 0.166%. Based on the 2023 sample mean of the rural revitalization level (0.235), a 10% increase in digital technology is expected to raise the rural revitalization index by approximately 0.039 points. Using the rural revitalization index range (0.117–0.437) as a reference, the impact scale accounts for approximately 1.2% of the total range. This indicates that although digital technology is not the sole driving force, its marginal contribution is substantial, both statistically and economically.

4.2. Analysis of Spatial Measurement Results

4.2.1. Spatial Correlation Test

To verify the spatial spillover effects of synergistic digital technologies and rural revitalization, this study conducted spatial correlation tests for both digital technology and rural revitalization development levels. The global Moran’s I index was calculated using the following formula:

In Equation (9), , where I denotes Moran’s I index, n represents China’s 30 provinces, is the spatial weight matrix, signifies regional digital technology (or rural revitalization development level), and denotes the regional mean of digital technology (rural revitalization development level). Moran’s I index ranges from −1 to 1. A positive I (>0) indicates positive correlation among regions, a negative I (<0) indicates negative correlation, and an I close to 0 suggests no correlation. Specific results are shown in Table 6.

As shown in Table 7, under the inverse distance squared adjacency matrix, the global Moran’s I indices for rural revitalization are all positive and exceed the 5% significance level. This indicates that rural revitalization development across provinces is not random but is influenced by neighboring regions, with a positive correlation. Simultaneously, digital technology (DIG) also passes the 1% significance level test across all provinces. The results of the global spatial autocorrelation test reveal that rural revitalization development and digital technology exhibit significant spatial dependence overall. Therefore, conducting spatial measurement analysis is necessary.

Table 7.

Calculation of Global Moran’s I Index from 2014 to 2023.

4.2.2. Model Specification Testing

Before conducting spatial econometrics, selecting an appropriate model is crucial to ensure robust results. As discussed earlier, spatial correlation among digital technologies necessitates including a spatial weight matrix in the model. Subsequently, the empirical section requires selecting a spatial econometric model for estimation. To enhance the accuracy of the estimation results, this study conducted LM, Hausman, likelihood ratio (LR), and Wald tests, with the results presented in Table 8. Table 8 indicates that in the LM test results, the p-values for the spatial error model are all below 0.01, suggesting a robust spatial error model can be selected. Similarly, the p-values for the spatial lag model are all below 0.01, indicating that a robust spatial lag model can be used for regression. The LR test results indicate that, in the comparison between the spatial Durbin model and the spatial error model, the model rejects the spatial error model. Similarly, in the comparison between the spatial Durbin model and the spatial lag model, the regression-to-the-mean test rejects the spatial lag model.

Table 8.

Results of Model Specification Tests.

Therefore, this paper selects the spatial Durbin model for empirical testing. Concurrently, the Wald test yielded a p-value of 0.000, indicating rejection of the null hypothesis. To determine whether fixed or random effects should be adopted, the Hausman test was further conducted. Both p-values were less than 0.01, indicating that the fixed effects model should be selected for empirical research. After a comprehensive review of all test results, the dual fixed-effects spatial Durbin model (fixed for time and individual) was selected for empirical analysis. The empirical regression results are shown in Table 9.

Table 9.

Regression Results and Effect Decomposition of the Spatial Durbin Model.

4.2.3. Spatial Durbin Model Regression Analysis

To test Hypothesis 4, we performed model regression using Stata 16 software based on the spatial Durbin model established earlier (Model (8)). The results are presented in Table 9.

From the regression results of the spatial Durbin model in Table 8, with the inverse-distance-squared adjacency matrix (ω1), the coefficients on the impact of digital technology on rural revitalization are all positive. This indicates that digital technology significantly enhances rural revitalization, thereby supporting Hypothesis 4. Regarding spatial autocorrelation, the spatial autocorrelation coefficients for rural revitalization development levels are all substantially positive and exceed the 1% significance level. This indicates a positive spatial correlation in the rural revitalization processes of neighboring regions. Furthermore, the spatial lag coefficient for digital technology is significantly positive, demonstrating that the impact of digital technology on rural revitalization exhibits spatial linkage effects. Digital technology can overcome spatial constraints to generate significant positive spatial spillover effects in neighboring regions.

The decomposition of spatial effects (Table 9) shows that the total elasticity of digital technology is 0.569, with a direct effect of 0.227 and an indirect (spillover) effect of 0.342. This means that if the level of digital technology in a province increases by 10%, not only will the level of rural revitalization in that province directly increase by approximately 2.27%, but it will also drive an overall increase of approximately 3.42% in surrounding provinces through spatial spillover, ultimately achieving a comprehensive increase of approximately 5.69%. It is worth noting that the spillover effect (0.342) exceeds the direct effect (0.227), highlighting the substantial potential of promoting digital rural construction within a regional collaboration framework and that the progress of digital technology can produce a regional linkage effect of “increasing returns”.

From a direct perspective, the application of local digital technologies is a key driver of revitalizing rural areas. It directly drives the upgrading of local rural industries, enhances farmers’ skills, and optimizes public services by promoting intelligent agricultural production, activating digital rural cultural tourism, and improving the precision of governance services. Indirectly, digital technologies possess cross-regional spillover effects. When an area develops mature application systems—such as innovative agriculture platforms, rural digital cultural tourism platforms, or grassroots digital governance tools—its accumulated experience, technology, and resources create a “radiation effect.” This helps surrounding regions reduce digital transformation costs and improve application efficiency, thereby achieving coordinated rural revitalization across areas. In terms of overall impact, each unit increase in the level of digital technology application boosts rural revitalization by 0.569. Collectively, digital technologies possess cross-regional radiating and driving capabilities. Through technology spillover, experience sharing, and the coordination and integration of resources, they not only enhance local rural revitalization but also drive the common development of surrounding areas, thereby forming a sustainable pattern of coordinated regional revitalization. Hypothesis 4 is validated.

According to the “Statistical Communiqué of the People’s Republic of China on the 2020 National Economic and Social Development,” the full sample is grouped into four categories: the Eastern Region, the Central Region, the Western Region, and the Northeast Region (Table 10).

Table 10.

The regression results and effect decomposition of the grouped spatial Durbin model.

In addition, following the regional classification in the Statistical Communiqué of the People’s Republic of China on the 2020 National Economic and Social Development, the full sample is divided into four groups: the Eastern, Central, Western, and Northeastern regions. Empirical findings indicate that, overall, digital technology exerts positive spatial spillover effects on rural revitalization; however, it demonstrates negative impacts in the Western and Northeastern regions. This paradoxical outcome may be attributed to the interplay of several complex mechanisms: First, the factor siphon effect—during the early stages of digital economic development, critical resources such as talent and capital tend to migrate from digitally underdeveloped rural areas to regional core cities, thereby intensifying internal disparities. Second, the digital divide lock-in effect—constrained by inadequate infrastructure, limited technical skills, and industrial structural weaknesses, less developed regions face challenges in assimilating technological spillovers from more advanced areas, resulting in the persistence or even exacerbation of regional gaps. Third, the homogeneous competition effect—in regions with similar industrial profiles, early adopters leveraging digital technologies to secure market advantages may displace comparable industries in follower regions. Fourth, the uneven policy effect—asymmetrical allocation of resources within regions may restrict the diffusion of digital benefits, creating a dichotomy between “policy-advantaged” and “policy-disadvantaged” areas. Future research could employ case comparisons or more granular data to identify which mechanisms dominate in specific regional contexts, thereby informing targeted policy interventions designed to prevent and mitigate adverse spillover effects.

4.3. Endogeneity and Robustness Tests

4.3.1. Endogeneity Test

This paper examines the impact of digital technology on rural revitalization. Theoretical analysis suggests empirical research may encounter two endogenous issues. Firstly, bidirectional causality: while digital technology development promotes rural revitalization, the latter may also influence the former. Secondly, omitted variables: the impact of digital technology on rural revitalization may be affected by unobservable factors, such as government policies impacting digital technology, potentially leading to biased regression coefficients. Therefore, to enhance the rigor of the benchmark regression results, this study employs instrumental variable (IV) analysis for endogeneity testing. Firstly, drawing on the research of Xu and Tao [42] and considering the potential lag in digital technology adoption, the lagged digital technology variable (IV1) is selected as the instrument. (IV1). The two-stage least squares (2SLS) method is employed for testing. The regression results are shown in column (1) of Table 11. The regression indicates that the regression coefficient for digital technology is 0.211, significant at the 1% level. Based on the theoretical analysis above, this suggests that after accounting for endogeneity issues, the development of digital technology fundamentally supports the theme that it promotes rural revitalization.

Table 11.

Results of Endogeneity and Robustness Tests.

4.3.2. Robustness Test

Firstly, considering that China explicitly proposed the “Digital China” initiative in 2015, which may introduce policy support bias, we excluded 2015 from the regression analysis [43]. The results are shown in column (2) of Table 11, where the enabling effect reaches 0.161 at the 1% significance level, demonstrating strong robustness. This indicates that digital technologies can sustainably empower rural revitalization development. Secondly, the four municipalities (Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, and Chongqing) possess unique economic strength and administrative status among China’s provinces. Excluding them from the sample and conducting a benchmark regression to verify the robustness of the conclusions yielded the results shown in Column (3) of Table 11. The coefficient direction and significance levels align with those in the benchmark regression results of Table 11, confirming the robustness of the preceding conclusions. To address potential endogeneity concerns and further validate the robustness of our core findings, we employed an instrumental variable approach. Specifically, we utilized the product of the number of post and telecommunications facilities per million people in 1984 and the national information technology service revenue as an instrumental variable. The results shown in Column (4) of Table 11 confirm that the coefficient for digital technology remains statistically significant and positive, and the model passes the standard weak instrument test. This provides additional evidence that the enabling effect of digital technology on rural revitalization is robust even after accounting for potential endogeneity. Additionally, this study applied tail trimming at the 1% and 99% percentiles to all variables in the benchmark regression, replacing values exceeding the highest percentile or falling below the lowest percentile. The results of the robustness test are shown in column (5) of Table 12, showing findings largely consistent with previous tests, further confirming the robustness of the conclusions. Finally, we replaced the core explanatory variable with two representative alternative indicators—the length of long-distance optical cable lines and the penetration rate of internet broadband access subscribers—and re-ran the regression. The results show in columns (6) and (7) of Table 12 that, even after substituting the variables, the impact of digital technology on rural revitalization remains statistically significant, and the direction of the effect aligns with the baseline conclusions. This indicates that the findings of this study are not dependent on any specific measurement approach, further attesting to the robustness of the conclusions. In summary, through a series of tests—including excluding policy-sensitive years, removing special administrative samples, winsorizing extreme values, and substituting core variables—the study’s conclusions have been consistently validated, demonstrating that the research findings on digital technology empowering rural revitalization exhibit strong robustness and reliability.

Table 12.

Results of Endogeneity and Robustness Tests.

In addition to the robustness test method described above, this paper re-estimates the spatial econometric model by replacing the spatial weights matrix with the inverse-distance first-power matrix and the adjacency matrix. If the estimation results are consistent with those in Table 9, it indicates that the robustness test is passed (Table 13).

Table 13.

Results of robustness tests after replacing the weight matrix.

Columns (1) and (2) of Table 14 present the estimation results of the inverse distance first-power matrix and the adjacency matrix, respectively. The results of the robustness test indicate that advances in digital technology can significantly accelerate rural revitalization in the local area and have a positive spatial spillover effect on neighboring areas. This is consistent with the test results reported above, indicating that the paper’s conclusions are robust.

Table 14.

Regression Analysis of the Five Dimensions.

To investigate the differential impact of digital technology on various aspects of rural revitalization, this study synthesizes the subdivided indicators of the five dimensions—“prosperous industries,” “ecological livability,” “civilized rural culture,” “effective governance,” and “affluent life”—into five sub-indices using the entropy method. Each sub-index is then used as the dependent variable in separate regression analyses. The results indicate that digital technology exerts a statistically significant positive effect on all five aforementioned dimensions.

4.4. Mechanism Verification

4.4.1. Digital Technology, Cultural Industries, and Rural Revitalization

To test Hypothesis 2—whether the cultural industry mediates the relationship between digital technology and rural revitalization—this study employs stepwise regression to examine the mediating effect empirically. Firstly, Model (2) analyzes the impact of digital technology on the cultural industry, with results presented in Column (1) of Table 15. Findings indicate that the regression coefficient for digital technology on the cultural sector is 0.121 and statistically significant, demonstrating a strong positive correlation between the two variables.

Table 15.

Results of Mediating Effect Test.

From a systemic perspective, this catalytic effect manifests primarily in two dimensions: innovation on the supply side and expansion of dissemination channels. On the one hand, the application of emerging digital technologies, such as virtual reality (VR), blockchain, and 5G networks, enables the digital presentation and dissemination of rural cultural resources, infusing new vitality into traditional rural cultural tourism industries. For instance, VR technology can create virtual tourism scenarios, delivering immersive experiences that allow visitors to preview rural landscapes and folk cultures within digital environments. On the other hand, the rise in live-streaming platforms has overcome geographical constraints, enabling the real-time broadcasting of rural attractions, intangible cultural heritage skills, and folk activities to broader audiences. This significantly enhances the market visibility and commercial value of rural cultural products, thereby laying a solid foundation for the sustainable development of the cultural industry.

Secondly, model (3) is used to examine the impact of the cultural industry on rural revitalization, with results shown in column (2) of Table 15. The results indicate that the regression coefficient for the cultural industry’s effect on rural revitalization is 0.373, which is significantly positive. This confirms that the cultural sector significantly promotes rural revitalization, establishing the mediating effect. Further analysis reveals that the prosperity of the cultural industries can promote rural revitalization through multiple pathways: Firstly, the economic path—the development of the cultural and tourism industry drives the creation of diverse job opportunities such as tour guiding, homestay management, and cultural and creative product development, effectively absorbing surplus rural labor and increasing farmers’ income; Secondly, the infrastructure pathway: cultural industry development accelerates upgrades in rural supporting facilities like transportation, lodging, and catering, improving rural living environments and conditions. Thirdly, the cultural heritage pathway: digital technology provides new carriers and opportunities for the protection, living inheritance, and innovative development of rural intangible cultural heritage, activates the endogenous vitality of rural culture, and lays a solid foundation for building a resilient rural cultural ecosystem with local characteristics and realizing the social sustainability of rural culture.

In summary, digital technology not only directly advances rural revitalization but also serves as a crucial intermediary mechanism linking the two by fostering the development of cultural industries. Cultural industries serve as a “bridge” and “link” between digital technology and rural revitalization, acting as a vital intermediary link in enabling digital technology to empower comprehensive rural revitalization. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 is validated.

4.4.2. Digital Technology, Higher Education, and Rural Revitalization

To test Hypothesis 3—whether higher education mediates the relationship between digital technology and rural revitalization—this study also employs stepwise regression to verify it empirically. Based on the estimation results of Models (2) and (3), as shown in columns (3) and (4) of Table 15, the regression coefficient of digital technology on higher education is significantly positive, and the regression coefficient of higher education on rural revitalization is also considerably positive. This indicates that higher education plays a significant mediating role in the process by which digital technology influences rural revitalization. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 is supported.

This result indicates that digital technology not only directly promotes rural revitalization but also creates an essential indirect pathway by advancing higher-education development. Specifically, on the one hand, the proliferation of digital technology has profoundly transformed teaching models, educational resource allocation, and talent cultivation methods in higher education. Digital education platforms, exemplified by “smart education,” “cloud classrooms,” and “virtual laboratories,” enable the sharing of high-quality educational resources between urban and rural areas, thereby narrowing educational development gaps and creating new opportunities to cultivate high-caliber talent in rural regions. On the other hand, higher education provides sustained endogenous momentum for rural revitalization through mechanisms such as talent development, technological innovation, and knowledge spillover. It constructs a sustainable development system featuring a virtuous cycle of “talent-technology-industry”. Universities not only provide intellectual support for agricultural and rural modernization through theoretical research and technological innovation but also introduce advanced technologies and management concepts to rural areas via industry-academia-research collaborations and university-local partnerships, thereby enhancing the innovation capacity and development level of rural industries.

Since China’s higher education entered the popularization stage, the state has consistently promoted educational assistance policies, such as the “Sunshine Project.” Leveraging university resources, it has launched nationwide multi-tiered training programs for new-type professional farmers, leaders of new agricultural business entities, and rural industry pioneers. These initiatives have expanded the functional boundaries of higher education’s service to rural areas, serving as a crucial pathway for higher education to “reach down” to rural communities and advance the construction of lifelong education systems. Through this process, higher education has not only elevated the knowledge and skill levels of the rural workforce but also strengthened the innovation capacity and developmental resilience of rural communities.

In summary, higher education has played a pivotal intermediary role in the process by which digital technology empowers rural revitalization. By driving the digital transformation of education and promoting the equitable distribution of educational resources, digital technology has indirectly advanced talent cultivation and innovation capacity in rural areas. This has formed a transmission chain linking “digital technology—higher education—rural revitalization,” providing crucial support for achieving sustainable rural revitalization. Therefore, Hypothesis H3 is validated.

To quantify the relative importance of the two mediating paths, we also calculated the proportion of the mediating effect to the total effect. Based on the coefficients in Table 15, the mediating effect of the cultural industry path is 0.045, accounting for approximately 27.1% of the total effect (0.166). The mediating effect of the higher education path is 0.009, accounting for about 5.4% of the total effect. This indicates that, in the process of digital technology empowering rural revitalization, more than a quarter of the impact is achieved through promoting the cultural industry. In contrast, the higher education path, although significant, makes a relatively minor contribution. This suggests that policies should pay special attention to the integration of digital technology and rural cultural resources to unleash greater empowering potential.

Theoretically, the penetration and application of digital technology represent a relatively antecedent process, and its subsequent effects—activating cultural industries, extending the reach of higher education resources, and ultimately contributing to rural revitalization—should involve a reasonable time lag. Accordingly, in our mediation effect test model, we lagged the core explanatory variable, digital technology (DIG), by one period. That is, we used the level of digital technology in period t−1 to explain the mediating variables and the level of rural revitalization in period t. This specification better aligns with the logical chain of “technology leads → mediation transmits → outcomes emerge.” The results, as shown in Table 16, indicate that compared with the benchmark model, the relative magnitudes of the direct and indirect effects have changed slightly. Nevertheless, the core mechanism by which digital technology facilitates rural revitalization through cultural and educational channels remains intact.

Table 16.

Results of the Mediation Effect Test Using Lagged Digital Technology.

4.5. Heterogeneity Analysis

Given China’s vast territory and significant regional disparities, distinct differences exist across regions in economic foundations, levels of digitalization, and resource endowments. To conduct a more in-depth analysis of the regional effects and variations in digital technologies in promoting rural revitalization, this paper adopts the heterogeneity analysis method proposed by Tang and Ma [31], dividing the 30 provinces into eastern, western, southern, and northern regions. Additionally, considering that major grain-producing regions possess stronger agricultural resource endowments and more comprehensive agricultural production systems compared to non-major grain-producing areas [44], and given that the development of digital infrastructure in major grain-producing areas and major grain-consuming regions may occur at different stages and levels, their enabling effects on high-quality rural agricultural development may also vary. Therefore, this study further divides China’s 30 provinces into major grain-producing and major grain-consuming regions to conduct regional heterogeneity tests.

4.5.1. Regional Heterogeneity

China exhibits significant variations in population density. Drawing on the methodology of Jiang and He [45], this study employs the “Hu Huanyong Line” as a demarcation criterion to divide China’s 30 provinces into eastern and western regions for heterogeneity analysis. The results are presented in Column (1) and Column (2) of Table 17. The empirical results indicate that digital technologies exert a significant positive effect on rural revitalization in the eastern region (coefficient: 0.225), whereas this impact is insignificant in the western region. This disparity primarily stems from differing developmental foundations across regions. As a leading region in China’s reform and opening-up, the eastern region possesses distinct locational advantages and well-developed digital infrastructure. Its higher level of digital technology adoption effectively drives industrial upgrading and resource integration, thereby significantly advancing rural revitalization. In contrast, the western region faces constraints from geographical conditions, weak infrastructure, and insufficient technological application capabilities, resulting in higher digital transformation costs and an underutilized enabling effect of digital technologies. Consequently, opening up plays a more prominent role in promoting rural revitalization in the western region. Overall, the promotional impact of digital technologies on rural revitalization exhibits significant heterogeneity between China’s eastern and western regions, with pronounced enabling effects in the east and untapped potential in the west. Therefore, differentiated development strategies should be implemented based on regional characteristics: Eastern regions should continue to deepen the application of digital technologies and strengthen innovation-driven development; Western regions should prioritize improving digital infrastructure, enhancing digital skills, and leveraging open economies to achieve coordinated development.

Table 17.

Results of Heterogeneity Test.

As shown in Column (3) and Column (4) of Table 17. Further examining regional disparities from a north–south perspective reveals that digital technologies exert a significantly positive impact on rural revitalization in southern regions. In contrast, no such effect is evident in northern areas. Southern regions possess a more developed digital industrial system and a vibrant digital economic ecosystem, enabling the integration of digital technologies into rural production, governance, and cultural development more efficiently. This fosters a pattern of deep convergence between digital and rural elements, thereby injecting robust momentum into rural revitalization. In contrast, northern regions exhibit insufficient penetration and depth of digital technology, with relatively lagging digital industry development. Rural progress there relies more heavily on traditional factors, such as tax policies, industrial-structure optimization, and government intervention. Overall, the role of digital technology in rural revitalization shows pronounced regional disparities between the north and the south. Southern regions should continue to deepen the integration of digital technologies across agriculture, governance, and culture. Northern areas, meanwhile, need to focus on enhancing digital infrastructure and technological application capabilities while leveraging the stabilizing support of traditional economic factors to achieve synergy between digitalization and traditional development drivers.

4.5.2. Major Grain-Producing Regions

Agriculture serves as the core foundation for rural revitalization and the “ballast stone” of national food security. This study categorizes the sample into major grain-producing regions and non-major grain-producing regions based on the delineation of grain production functional zones, as shown in Column (5) and Column (6) of Table 17. Empirical results show that digital technologies significantly promote rural revitalization in both regions, though with differing intensities: the coefficient for digital technologies in the grain-producing areas is 0.0673 (p < 0.01), while in the non-producing areas it is 0.201 (p < 0.01). This divergence stems from distinct regional functions: grain-producing areas prioritize food security, with relatively homogeneous industrial structures, in which digital technologies are concentrated on agricultural production while non-agricultural penetration remains limited. Conversely, non-grain-producing areas feature more diversified industrial structures, enabling digital technologies to drive broader integration of secondary and tertiary industries alongside multifunctional agricultural development. This fosters rural economic restructuring and cultivates new business models. Overall, digital technologies promote rural revitalization nationwide, yet their mechanisms of impact vary in structure. To safeguard national food security and sustainable agricultural production, we should strengthen digital transformation and the application of technology in agriculture to ensure the long-term stability and sustainable development of the grain industry.

Non-grain-producing regions should accelerate the deep integration of digital industries into rural economies to enhance economic diversification and sustainable development.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Digital technology, as an important engine driving the rural revitalization strategy, is of far-reaching significance for realizing Chinese-style modernization. This paper takes 30 provinces (excluding Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan, and Tibet) from 2014 to 2023 as research samples, constructs a comprehensive evaluation index system for rural revitalization from a provincial perspective covering five dimensions, “prosperous industries, livable ecology, civilized rural customs, effective governance, and affluent life”, and uses the entropy method for quantitative measurement. On this basis, the fixed effect model, mediating effect model, and spatial Durbin model are comprehensively used for empirical testing, and the following main conclusions and innovative findings are obtained:

1. Significant direct driving effect: Digital technology has a significant direct promoting effect on rural revitalization. After controlling for a series of economic and social factors, as well as provincial and year fixed effects, this conclusion remains robust at the 1% significance level, confirming that digital technology is the primary driver of comprehensive rural revitalization. 2. Obvious spatial spillover effect: The impact of digital technology on rural revitalization has a significant positive spatial spillover effect. It can not only improve rural revitalization in the region but also have a positive, radiating, and driving effect on neighboring regions, providing a new path for promoting overall revitalization through regional coordination. 3. Key mediating transmission mechanism: Cultural industries and higher education play a key mediating role in the process of digital technology empowering rural revitalization. Digital technology indirectly promotes the sustainable development of the rural economy, society, and culture by fostering the prosperity of cultural industries and the expansion of higher education, thereby revealing the indirect pathway of “technology–culture/education–rural development”. 4. Regional heterogeneity in empowerment effect: There are significant regional differences in the empowerment effect of digital technology, which is more prominent in the eastern region of the Hu Huanyong Line, the southern region, and non-major grain-producing areas. This finding emphasizes that the differences in regional endowments and development stages must be fully considered in policy formulation.

Based on the above research findings, this paper proposes the following policy recommendations: First, efforts should be made to promote the regional co-construction, sharing, and coordinated development of digital infrastructure. Given the significant positive spatial spillover effects of digital technology, it is necessary to overcome administrative divisional constraints and establish a cross-regional mechanism to coordinate the investment and operation of digital infrastructure. Investment priorities should be clearly defined, adhering to the principle of “infrastructure first, tailored to needs.” In less-developed regions, priority should be given to investing in low-cost, high-coverage digital infrastructure (such as 4G/5G and public Wi-Fi). In contrast, in the developed areas, upgrades to smart agriculture and digital governance systems can be pursued. Technologically advanced areas should be encouraged to drive the development of surrounding underdeveloped regions through platform openness, data sharing, and talent exchange. Particular emphasis should be placed on bridging the digital access and application gaps in central, western, and northeastern regions, transforming technological externalities into tangible benefits for regional coordinated development. Second, implement a dual-track empowerment strategy of “culture-led, education-supported.” Policies should prioritize the digital activation and industrial development of rural cultural resources, vigorously supporting new formats such as digital cultural and creative industries and smart cultural tourism. At the same time, targeted efforts should be made to deepen the integration of higher education and digital technology. Through online education, skills training, and talent return policies, a continuous supply of compound talents with both digital literacy and local sentiment should be provided to rural areas, establishing a sustainable transmission mechanism of “technology—culture/education—development.” To reduce regional inequalities in digital development, it is recommended that a “Digital Revitalization Regional Equity Fund” be established to provide targeted support for digital skills training and localized digital application development in lagging regions through transfer payment mechanisms, thereby mitigating the potential exacerbation of regional disparities caused by uneven technological spillovers. Third, formulate differentiated and precise regional empowerment plans. The “one-size-fits-all” approach should be abandoned, and accurate interventions should be implemented based on regional functional positioning. In eastern and southern regions, the deep integration of digital technology with rural characteristic industries should be promoted. In western and northeastern regions and major grain-producing areas, priority should be given to the popularization of digital infrastructure, with a focus on the application of digital technologies in core areas such as agricultural production, food security, and ecological protection. Complementary policies to prevent the outflow of factors should be implemented to achieve coordinated development and overall advancement of rural revitalization nationwide.

Author Contributions

Y.Z.: Software, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—original draft. W.X.: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing—review and editing. B.D.: Formal analysis, Data curation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Nos. 72201134], Research Institute for Risk Governance and Emergency Decision-Making, School of Management Science and Engineering, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, Nanjing 210044, China. And Collaborative Innovation Center on Forecast and Evaluation of Meteorological Disasters (CIC-FEMD), Nanjing University of Information Science & Technology, Nanjing, China.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.

References

- Zeng, X.M.; Hu, Y. Key issues and development progression of digital technology enabling rural revitalization from the perspective of Chinese path to modernization. J. Guizhou Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2024, 1, 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, B.; Li, Y.; Zhang, G. The impact mechanism and spatial effect of digital rural construction on rural revitalization. China Bus. Mark. 2023, 37, 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, X.P.; Liu, J.J. Promoting comprehensive rural revitalization through the integrated application of digital technologies: A “value chain-interest chain implementation pathway” analytical framework. World Agric. 2025, 7, 56–68. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.Y.; Yan, X.Y. Practical inspection and reflection on digital technology empowering rural revitalization: A case study based on typical examples from national rural revitalization demonstration counties. J. Agro-For. Econ. Manag. 2025, 24, 880–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. The enabling role of digital technology for rural revitalization. Int. J. Glob. Econ. Manag. 2024, 3, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skare, M.; Riberio Soriano, D. How globalization is changing digital technology adoption: An international perspective. J. Innov. Knowl. 2021, 6, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Yue, S.; Guo, C.; Gao, P. Unleashing global potential: The impact of digital technology innovation on corporate international diversification. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 208, 123727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, L.; Heckelei, T.; Gerullis, M.K.; Börner, J.; Rasch, S. Adoption and diffusion of digital farming technologies–integrating farm-level evidence and system interaction. Agric. Syst. 2021, 190, 103074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. Research on the application of agricultural informatization construction under the background of new media. Rural Econ. 2019, 9, 110–115. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, W.; Xu, L.Y. On new quality productivity: Connotative characteristics and important focus. Reform 2023, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.M.; Jiang, L. Digital economy, spatial effects and total factor productivity. Stat. Res. 2021, 38, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.C. The internal logic, practical dilemma and breakthrough path of digital technology empowering rural revitalization. Reform 2024, 7, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. Internal mechanism and policy innovation of digital technology enabling rural revitalization. Reform Econ. Syst. 2022, 3, 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.M.; Zhou, C. Analysis on the construction of an efficient rural logistics system under the background of comprehensively promoting rural revitalization. Theor. Investig. 2021, 3, 139–144. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.G.; Wu, H.Q. How to promote common prosperity in digital rural construction: The analysis framework based on “empowerment-adaptation”. Chin. Public Adm. 2024, 40, 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.C.; Yuan, T.T.; Li, X.S.; Wang, J.Q. Digital technology use and rural household income increase: Mechanism analysis and effect identification—Empirical analysis based on multitemporal asymptotic DID model. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J. How can the digitalization of cultural industry empower rural revitalization? Mod. Econ. Res. 2024, 2, 119–132. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.X.; Jia, Q.H. Value interpretation, operation logic, and development direction of rural public cultural space under the national cultural digitalization strategy. Res. Libr. Sci. 2025, 8, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.W.; Liang, H.F. The inner logic, realistic challenges and practical paths of digital technology empowering modernization of rural governance. Rural Econ. 2024, 7, 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.S.; Wang, J. How to dissolve the inherent tension in the construction of digital villages: An analytical framework for “agriculture, rural areas and farmers”. J. Tianjin Univ. Commer. 2024, 44, 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.B.; Guo, F.; Xiong, Y.J.; Lü, B. The enabling role of rural e-commerce in rural revitalization: The digital divide within rural areas. Econ. Sci. 2025, 5, 185–205. [Google Scholar]

- Kubo, Y. Scale economies, regional externalities, and the possibility of uneven regional development. J. Reg. Sci. 1995, 35, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, R.E., Jr. On the mechanics of economic development. J. Monet. Econ. 1988, 22, 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.H.; Feng, L.; Ding, S.J.; Tan, C. The impact mechanism and spatial spillover effects of agricultural digitalization on rural industrial revitalization. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Bai, X.G.; Zhao, M.; Liu, T.J. Impact of digital village construction on common prosperity: An empirical test based on the data from counties. Stat. Decis. 2025, 41, 65–70. [Google Scholar]